1. Introduction

The application of low-altitude drone photography in urban inspection, security patrol and emergency search and rescue is increasing, but the task of tracking weak targets still has major challenges to be solved: on the one hand, due to scale changes and motion jitter caused by aerial angle and imaging height, the target appearance and background interference frequently alternate, and the occlusion and illumination changes in complex environment lead to short-term prediction instability (as shown in

Figure 1, low-altitude drone overhead shot of a moving pedestrian on the ground and

Figure 2, drone long-distance imaging) [

1]. On the other hand, there are often significant cross-domain differences between the source domain and the target domain, and directly transferring the model to a completely new target domain will lead to a significant performance drop [

2].

Since this paper adopts the unified COCO data format, and the COCO format clearly indicates that the size of a small target is 32 × 32 pixels, this paper uses this as the size judgment boundary for small targets. The most important issue in the problem of the ability to discriminate small targets is the ability to represent small targets. However, the existing methods have not achieved good results in addressing the limitation of effective pixels for small targets, and therefore cannot have good robust performance in the task of tracking small targets in complex and variable scenarios [

4]. Moreover, the current methods have not solved the problem of model generalization ability in the task of tracking small targets. If the same target is tracked for a long time and multiple different background data are involved, the model will have difficulty achieving good performance in all data without manual annotation [

5].

Some scholars have designed multi-scale feature extraction and combined it with a pyramid structure to enhance the representation ability of small targets in order to deal with the small size of the target [

6]. However, these methods not only failed to solve the problem but also increased the computational cost. At the same time, some scholars have tried to introduce cross-modal fusion in order to highlight the information of the target in the context of background interference [

7]. Besides, such methods require accurate label information and cannot cope with the scenario without human annotation. At the same time, although Transformer-based tracking frameworks (such as SwinTrack) have achieved good results in labeled domain conditions in recent years, there is still a lack of methods that can enable the model to have good generalization ability when facing different scenarios and data without human annotation, when facing small targets and cross-domain settings [

8].

This paper proposes a novel annotation and training architecture. Its core idea is to improve the detection and tracking capabilities of weak targets in target tracking tasks by using pseudo-labels and background enhancement annotations for cross-domain training, forming a closed-loop training process [

9]. In the initial data processing stage, this paper proposes a background enhancement annotation (BEA) method. This method does not change the backbone network and decoder structure, but only enhances the annotation information in the classification branch. By expanding the shared pseudo-label bounding box and setting positive sample regions, background noise is suppressed, and the discriminability between the target and the background is improved. Regarding the training framework, this paper first uses two initial models trained independently in the source domain to predict the same frame in the target domain. Based on this, a joint gating mechanism is introduced, which only retains the frame for further training when the predictions of both models reach specific thresholds in terms of geometric position and confidence. This effectively suppresses the negative transfer effect caused by noisy supervision, thereby improving training stability. After consistency screening, the method employs a mutually optimized strategy, obtaining shared pseudo-labels through confidence-weighted soft fusion and uniqueness operations [

10]. These pseudo-labels are learned symmetrically between the two models, allowing the models to gradually adapt to the feature distribution of the target domain, thereby continuously improving the model’s generalization ability.

3. Method

3.1. Overall Methodology Overview

This section will elaborate on the overall network architecture process. All networks use SwinTrack as the baseline tracker, denoted as network F(⋅). The differences between the models are only reflected in the parameters, denoted as and , respectively. and are obtained from two different common source domains, Domain and Domain , respectively, learning two significantly different feature distributions. is used for label-driven teacher learning on the self-made target domain, Target Domain , and is also the convergence center of the entire iterative training. Structurally, the three networks are all composed of a template and a search dual-branch architecture, SwinTransformer, a quality-aware classification head, and a boundary regression head. The functional division of each role is completed through iterative parameter updates.

Figure 4 shows a schematic diagram of the overall network architecture. The middle part of the figure shows two student models,

and

, independently performing forward inference on

in round t, generating two sets of candidate pseudo-labels:

and

, where

and

represent the predicted bounding box and

and

represent the corresponding quality score. Then, the two pseudo-labels undergo consistency screening under a unified coordinate system, retaining only those that meet the consistency screening threshold and the geometric consistency threshold as refined pseudo-labels. These pseudo-labels are then uniquely merged to obtain

. In the classification response map, this is represented by a unique positive sample grid centered at

, with the quality score at

, and the rest as background grids, thus constructing a clear and robust supervision signal. Furthermore, the orange arrows indicate the parameter updates for both the teacher and student models. The teacher model

uses the unique shared pseudo-label

as a supervision signal in

to update the teacher model’s parameters, obtaining

. Subsequently, the student model’s parameters are updated using the exponential moving average (EMA) method:

Then, the process moves to the next round, where and again generate the next round of pseudo-label candidate boxes and in , thus forming the entire closed-loop operation. Throughout the process, while maintaining the SwinTrack structure, the model’s adaptability is gradually transferred from the source domain to the target domain through iterative training, thereby improving the robustness and cross-domain capability of tracking single weak targets.

3.2. Background Enhancement Annotation

This section introduces a proposed annotation strategy for enhancing backgrounds to alleviate the limited information content of small targets. In the original coordinate system, the dimensions of the target bounding box are enlarged proportionally based on its center to serve as the template bounding box. A supervised construction strategy is employed: classification focuses on the enhanced bounding box while regression points to the original bounding box. This involves quality-aware and supervised classification operations on the positive samples corresponding to the enhanced bounding boxes, while regression uses the original bounding box as the target, ensuring consistency in evaluation criteria and predicted geometry.

In implementation, the template and search bounding boxes are cropped at the center with the same magnification factor and resampled to a fixed size. If any bounding errors occur, edge padding is applied. The entire computation and memory overhead is equivalent to the baseline. Specifically, during training, the source domain bounding boxes and generated target domain pseudo-labels are magnified at the same ratio to ensure consistent cross-domain supervised training. During inference, the uniformly magnified enhanced bounding boxes are only used for cropping and feature extraction, and the final prediction result is written back to the original bounding box in the original coordinate system. The above strategy explicitly encodes the prior of the effective reference of the steady-state background in adjacent frames: it not only increases the proportion of effective tokens for weak targets in the entire input, but also provides a more robust geometric contrast in the case of occlusion or slight deformation; thus, on the baseline, it obtains effective gains for weak target tasks under a consistent decision index system, which facilitates subsequent ablation and comparison experiments.

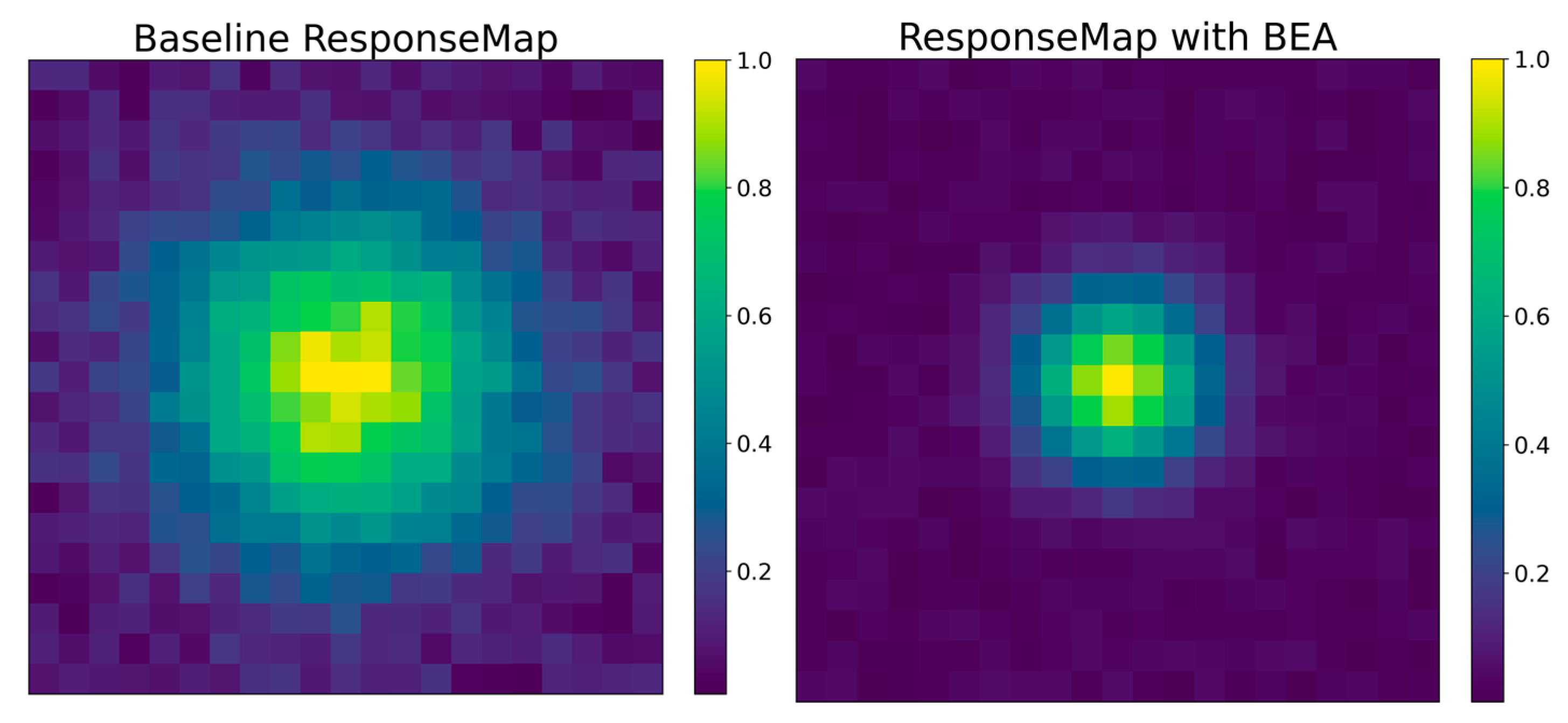

As shown in

Figure 5, the left side shows the default annotation, where the bounding box only indicates the target size, resulting in limited effective target information within the ROI. The right side shows the uniformly enlarged augmented bounding box, where the center remains unchanged while the bounding box is proportionally enlarged according to global parameters, thus including more background information within the ROI. During the training phase, the classification branch generates positive samples and quality supervision within the augmented bounding box shown on the right, thereby improving attention concentration and cross-domain robustness. The regression branch continues to use the original bounding box on the left to backpropagate, maintaining consistency in the output geometric parameters and evaluation criteria.

To verify the effectiveness of this method, this paper compares the response plot with the baseline and obtains the comparative data, which is intuitively displayed in the following comparison plot.

As shown in

Figure 6 above, the response comparison diagram shows the baseline model on the left and the model with background enhancement on the right. It can be clearly seen that the response values in the baseline model’s response map are relatively scattered, with higher response values in the background region, resulting in low distinction between the target and the background. In contrast, the response map with background enhancement on the right shows an increase in response values around the target, exhibiting clearer response peaks, while the response values in the background region are significantly lower than the baseline. This demonstrates that the background enhancement annotation method improves model learning and thus enhances the model’s performance in tracking small targets by incorporating information from the target’s near-field background.

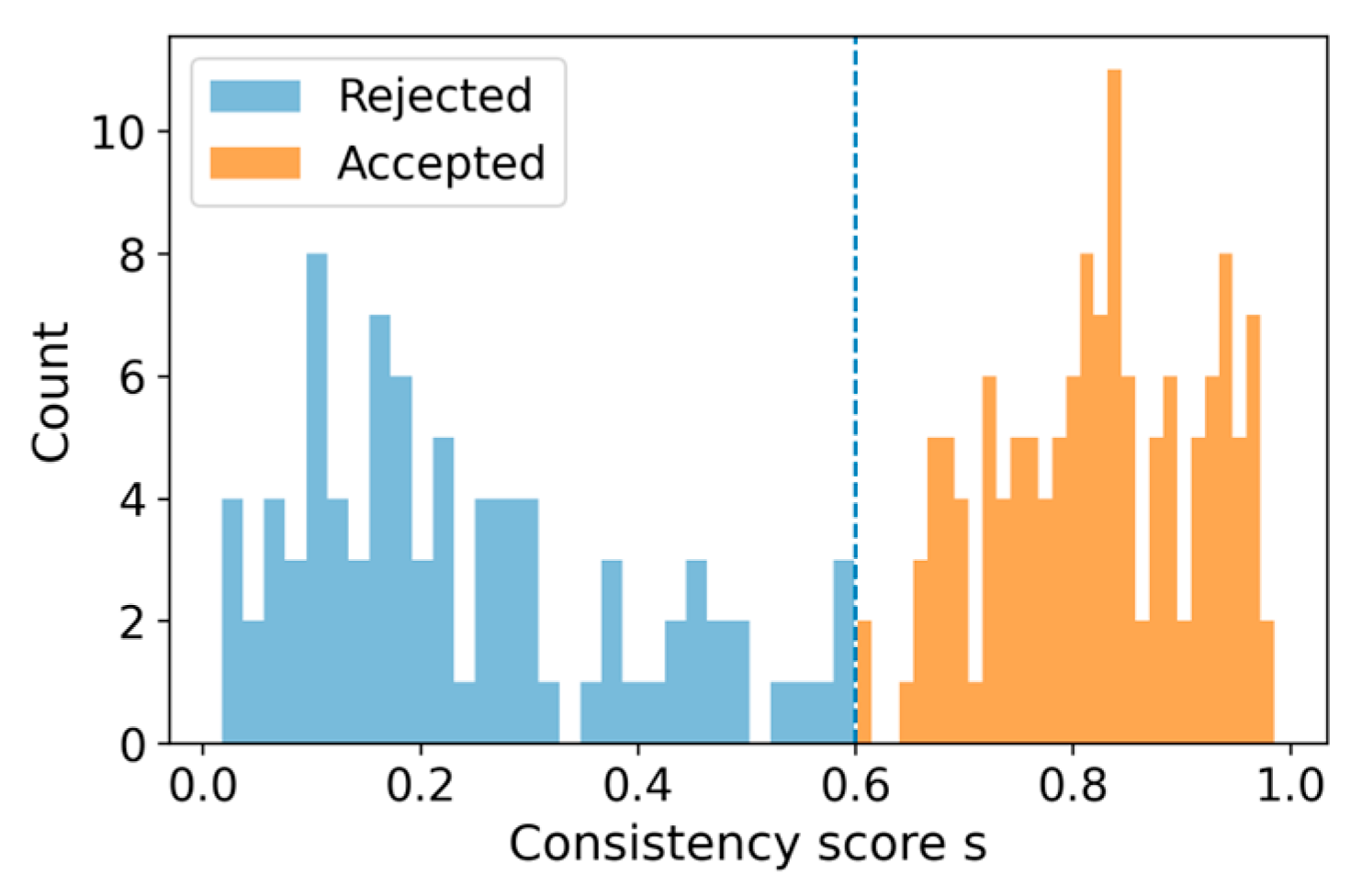

As shown in

Figure 7 above, the score distribution is as follows: the left side represents the baseline score, and the right side represents the score distribution after introducing the background enhancement strategy. The results show that the baseline model’s score distribution has a large overlap between the target and background scores, indicating a weak distinction between them. In contrast, the right side, after introducing background enhancement, shows that the target area scores significantly more than the background, thus better distinguishing the target from the background. This demonstrates that the model with background enhancement strengthens the distinction between the template and the background, providing a clearer criterion for subsequent pseudo-label selection and model iteration.

3.3. Consistency Screening Gate

To address the issue of reliable monitoring signals for unlabeled target domains, this section proposes a consistency screening gating mechanism combined with uniqueness for pseudo-label refinement. The pseudo-label consistency screening process is described below:

Suppose that in the t-th iteration, the source domain models

and

are used to perform inference in the target domain

, resulting in two initial pseudo-labels

and

:

Then, the two initial pseudo-labels are screened using consistency gating:

The screened pseudo-labels are retained and merged to make them unique:

where

is the number of pseudo-labels retained after consistency screening. Then, a teacher model is trained under the supervision of these pseudo-labels.

As shown in

Figure 8, the horizontal axis represents the consistency score, and the vertical axis represents the sample count. Color coding indicates that blue areas represent rejected samples, and orange areas represent accepted samples. The dashed line in the figure represents the threshold, which is approximately 0.6. Observing the distribution plot, a clear bimodal structure can be observed, indicating that there are two significant concentrated areas in the consistency score. Therefore, setting a threshold can effectively remove low-quality mislabeled data, thus providing cleaner and more reliable input data for subsequent data fusion.

As shown in

Figure 9, the left figure illustrates the prediction results of two initial models for the same target frame. It can be seen that both models have low confidence levels and low geometric overlap, resulting in a multi-peaked response distribution and a shift in the target center. These factors lead to poor frame quality, therefore this frame was not included in the supervision process and no fused bounding box was generated. The right figure shows the filtered pseudo-label, whose performance is significantly better than the initial model prediction results in the left figure. Specifically, the prediction results of the two models highly overlap, have high confidence levels, and exhibit a single-peaked response, indicating good target alignment. Since the prediction results meet the fusion criteria, the pseudo-labels are merged into a single label and used as the supervision signal for subsequent training. The quality of the pseudo-label directly affects its effectiveness as a supervision signal. When the pseudo-label quality is low, it will have a significant negative impact on cross-domain training; therefore, quality filtering of the pseudo-labels is crucial to ensuring the stability and efficiency of the training process.

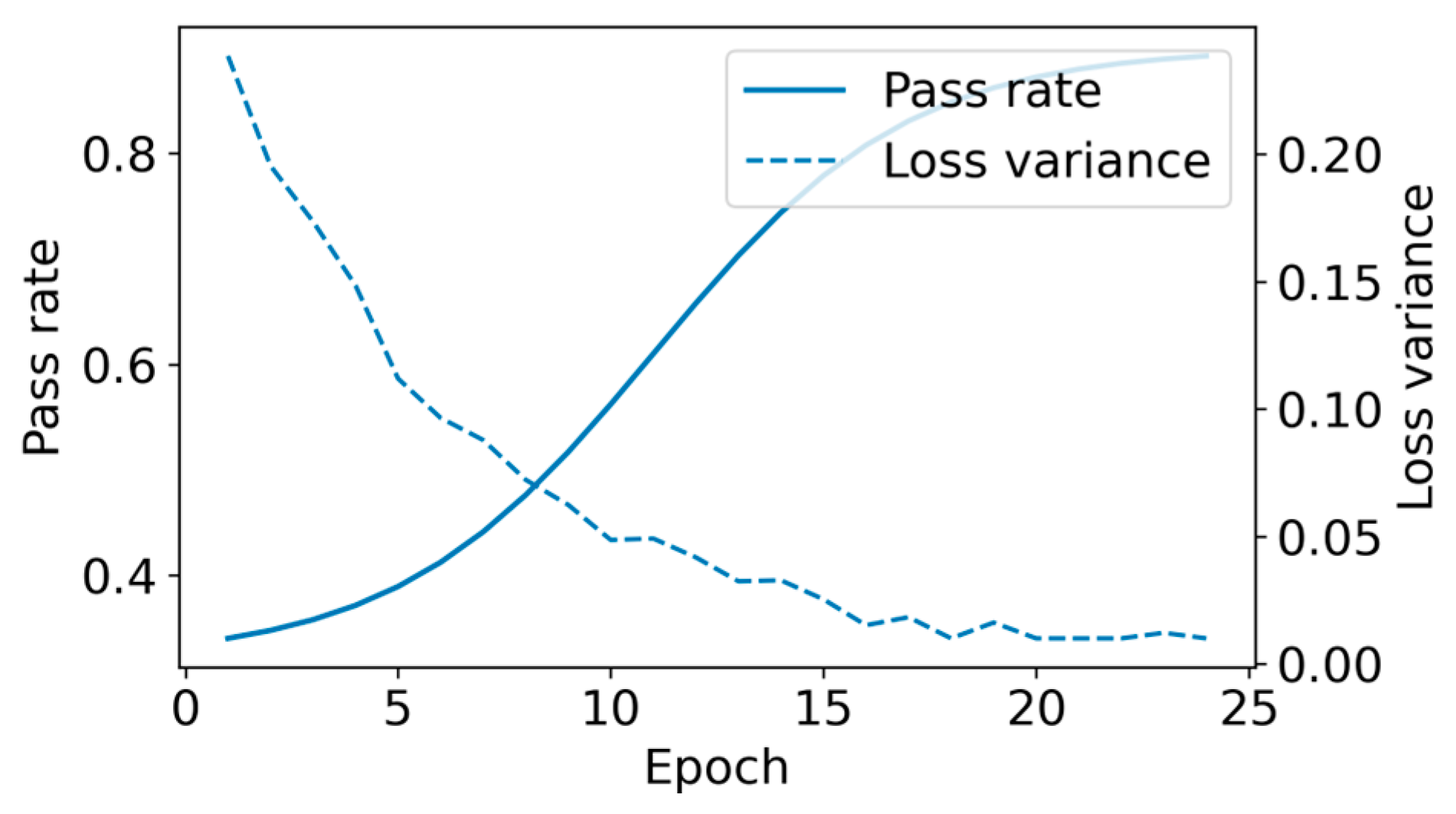

As shown in

Figure 10 above, the pass rate and loss variance statistics are as follows: the left axis and solid line represent the pass rate, while the right axis and dashed line represent the training loss variance of the teacher model. As the epochs are iterated, the pass rate gradually increases, indicating that the quality of the pseudo-labels is also improving. At the same time, the loss variance shows a rapid decrease and gradually tends to stabilize, which represents the gradual improvement of the stability of

and is also evidence of the model’s convergence.

3.4. Overall Algorithm Design

This section focuses on the algorithm flow of SwinMR as a whole. The two student models in the algorithm flow box in the table below were trained under supervised training using the source domains and for the first time, and subsequently updated by the teacher EMA to ensure stability during the iteration process (Algorithm 1). Unlabeled data in the target domain is generated independently by the two students, while retaining their classification confidence and regression quality indices. Predictions with large biases are then eliminated through consistency constraints of IoU and response scores, preventing erroneous pseudo-labels from being introduced into the training loop. Among the selected candidate pseudo-labels, the system introduces a weighted soft fusion mechanism to integrate the predictions of the two students according to their stability and confidence, thereby obtaining higher-quality pseudo-labels in terms of geometric location and response accuracy.

| Algorithm 1. SwinMR-Mutual Refinement Self-Training Framework |

Input:

, : labeled source-domain datasets

: unlabeled target-domain dataset

: SwinTrack-based tracking model

, : student model parameters are obtained only initially from training on .

, : updated by the teacher model EMA

Hyper-parameters: , , ,

Output:

Adapted model parameters , and fused teacher

/* when t = 0, supervised pretraining on source domains */

1 ← train_supervised()

2 ← train_supervised()

/* Iterative mutual-refinement loop */

For t = 1 to do

/* Stage1: teacher inference on target domain */

← infer(, )/boxes , scores /

← infer(, )/boxes , scores /

/* Stage2: consistency filtering of predictions */

for each frame f in :

for each prediction pair(, ):

c ← consistency_score(, )

if then

Add (, ) to

/* Stage3: unique fusion and ResponseMap construction */

←

for each frame f:

← fuse_unique()

Add to

/*Stage4:train teacher using fused pseudo-labels */

← train_supervised(, )

/* Stage5:EMA undate of teachers form */

←

←

|

/* optional fine-tuning students on pseudo-labels */

← train_supervised()

← train_supervised()

end for |

The final pseudo-labels adopt a ResponseMap structure compatible with SwinTrack, expressing the target location through a unique positive sample grid and CXCYWH normalization, allowing the teacher model to directly connect to existing tracking heads for training. During fixed-round training, the teacher model relies entirely on pseudo-labels for self-supervised learning. The classification branch uses Varifocal loss to enhance sensitivity to low-response regions of small targets, while the regression branch uses GIoU loss to ensure geometric accuracy in range prediction. After each training round, the teacher model’s weight updates are synchronized to both students via EMA, forming a stable closed-loop mutual teaching mechanism that jointly drives the continuous evolution of both teacher and students.

This multi-model collaborative mutual teaching design effectively avoids the uncontrollable accumulation of pseudo-label noise in single-teacher self-training, ensuring that pseudo-label quality is consistently improved in a controlled manner during iterations. The stability of the teacher model is also strengthened, allowing the student model to gradually learn more robust tracking capabilities across different scenarios. In experiments with real low-altitude overhead videos, this framework demonstrates significant advantages under challenging conditions such as extremely small scales, complex background interference, and target blur, with stable overall performance improvements, fully demonstrating its effectiveness and application value in cross-domain tracking tasks for small targets.

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

In the initial model training in the source domain, the model used two manually labeled public datasets, uav123 and VisDrone2019-SOT. The cropping sizes of the input template and the search region were fixed at 128 × 128 and 256 × 256, respectively. The patch size was 4, the window was divided into 7 × 7, and the backbone network used SwinTransformerV2Block. Each batch contained 32 pairs of samples. The optimizer used was AdamW, and the initial learning rate and weight decay were set to 1 × 10−4. In addition, the value β was set to (0.9, 0.999). The learning rate was gradually reduced every 40 epochs, i.e., a cosine annealing strategy was adopted. To prevent overfitting of the model, data augmentation operations such as random flipping and color perturbation were added during training. Target domain 1 consists of pedestrian sequences captured by drones over the campus, used for pseudo-label iterative training to drive the model’s generalization to the target domain. Target domain 2 also consists of pedestrian sequences captured by drones over the campus, but its overall feature distribution differs significantly from target domain 1, demonstrating the model’s generalization ability between two domains with large feature distributions. Of the two target domains, one participates in iterative optimization, while the other serves as the data for the comparative experiment, testing all models.

In the target domain mutual teaching phase, two initial models infer predicted bounding boxes. These boxes are then filtered for consistency based on geometric distribution and confidence threshold. Qualified frames and pseudo-labels proceed to the next round of iterative training. The filtered pseudo-label predictions, after unique fusion, serve as supervisory signals for further training of both models. Frames that fail the fusion are skipped by default. The training process in this phase is consistent with the source domain, but the learning rate is further reduced to 5 × 10−5, and the batch size is adjusted to 16 to prevent gradient oscillations that could lead to convergence instability. Furthermore, gradient clipping is enabled in each iteration, with the clip norm set to 0.5, accompanied by momentum smoothing to suppress the negative transfer effect of low-quality pseudo-label noise on the model. For loss, the classification branch uses a weighted combination of QFL and GIoU from the regression branch. The quality objective of the classification branch is the calibration score after unique fusion of pseudo-labels, while the regression branch regresses the unique positive sample grid to the geometric parameters of the pseudo-bounding boxes.

During cross-domain training, the model parameters in each round are updated with the refined results of the pseudo-labels from the previous round, forming an iterative generalization process in which the model gradually adapts to the target domain. During training, the backbone weights of several earlier layers are frozen, and a multi-stage warm-up strategy is used to mitigate training instability caused by the distribution differences between the source and target domains. The experiment was conducted on a 2080Ti × 4 platform, taking a total of 36 h. The experiment verifies that this configuration, while ensuring convergence speed is not affected, reduces the impact of pseudo-label noise, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability in the weak target tracking task.

4.2. Loss Function

Let the positive sample grid of frame t be

, the supervision box be

, and the quality score target be

(where the source domain is set to 1.0 and the target domain is the uniquely fused score). Furthermore, let the prediction of the classification branch be

, and the geometric prediction of the regression branch be

. Then, the QFL loss of the classification branch can be expressed as:

where r is the consistent modulation factor in the baseline, and

is the background weight: to better utilize the background enhancement effect, the ordinary background is set to 1, while the suppression near the enhancement box boundary is

, and the strong negative samples at a distance are set to

; the quality target

is only taken at the unique positive sample grid.

The GIoU used for the regression loss can be expressed as:

The supervision loss is computed only at the unique positive sample grid

, and the source domain is aligned with the original ground truth box while the target domain uses a shared pseudo-label box. Therefore, the supervision loss for each frame can be expressed as:

Since

and

are consistent with the baseline, the total loss can be expressed as:

where

and

represent the sample sets of the source domain and the target domain, respectively, and

represents the target domain weight that increases with r.

4.3. Evaluation Indicators

In terms of evaluation metrics, this paper adopts the OPE (One-Pass Evaluation) protocol: is defined as a given time-ordered set of consecutive frames, and is the ground truth bounding box in the first frame. The tracker is initialized using , and the predicted bounding boxes in subsequent frames are . If a target is missing in a frame or fails to produce a valid output, is considered 0. To avoid threshold drift caused by preprocessing scaling, all evaluation values are performed at the original image resolution. Results are given for all frames and for the effective subset of weak targets, achieving comparison in both overall performance and weak target performance.

The success rate curve and the area under the curve (AUC) are used as evaluation metrics for localization stability.

Define

the Intersection over Union (IoU) ratio for each frame,

as the success rate, and set by a threshold u ∈ [0, 1], while

The overall stability of the method is evaluated comprehensively from the perspectives of scale estimation and position alignment, set as the overall metric and independent of the threshold.

Based on pixel center error,

The point value P@20 at τ = 20 pixels is used as the reporting accuracy curve to characterize the intuitive pixel-level center alignment capability and thus define the center accuracy. To address the issue of intuitive comparability across sequences in scenes with weak targets and mixed resolutions, this paper requires scale-normalized center error: setting the diagonal length of the ground truth bounding box to.

Calculate the area under the curve with normalized precision in the range τ ∈ [0, 0.5].

Finally, AUC, P@20, and NP-AUC are complemented in three aspects: IoU stability, pixel-scale intuitive accuracy, and cross-scale comparability, while remaining independent of network structure and training strategy to facilitate experimental reproducibility.

Ultimately, the success rate curves (AUC), central accuracy (P@20), and normalized accuracy (NP-AUC) described above are used to evaluate the overall method across all test frames. A threshold < 1024 is used to explain the data composition and annotation caliber. Ablation experiments and comparative experiments are conducted to quantify the overall performance of this method in terms of weak target feature representation and tracking. The small-scale caliber defined by the area threshold designed above is naturally compatible with the COCO annotation format of consecutive frame datasets and has a greater advantage for slender targets. It also retains the statistical rules of the evaluation itself and is independent of the resolution and window scheduling during training and inference stages, thus quantifying the improvement of this method’s ability to preserve weak target features.

4.4. Ablation Studies

This section uses SwinTrack as a baseline to conduct ablation experiments on the pseudo-label consistency mutual refinement method (hereinafter referred to as SSL) and background enhancement annotation (hereinafter referred to as BEA). Except for whether SSL or BEA is used, all other experimental configurations are strictly consistent: the supervised training phase of the source domain uses UAV123 and VisDrone2019-SOT weak target union and is uniformly converted to COCO format; the self-training method of pseudo-label mutual refinement is only performed on the unlabeled target domain T1; and the final test results are all completed on the same unlabeled test target domain T2.

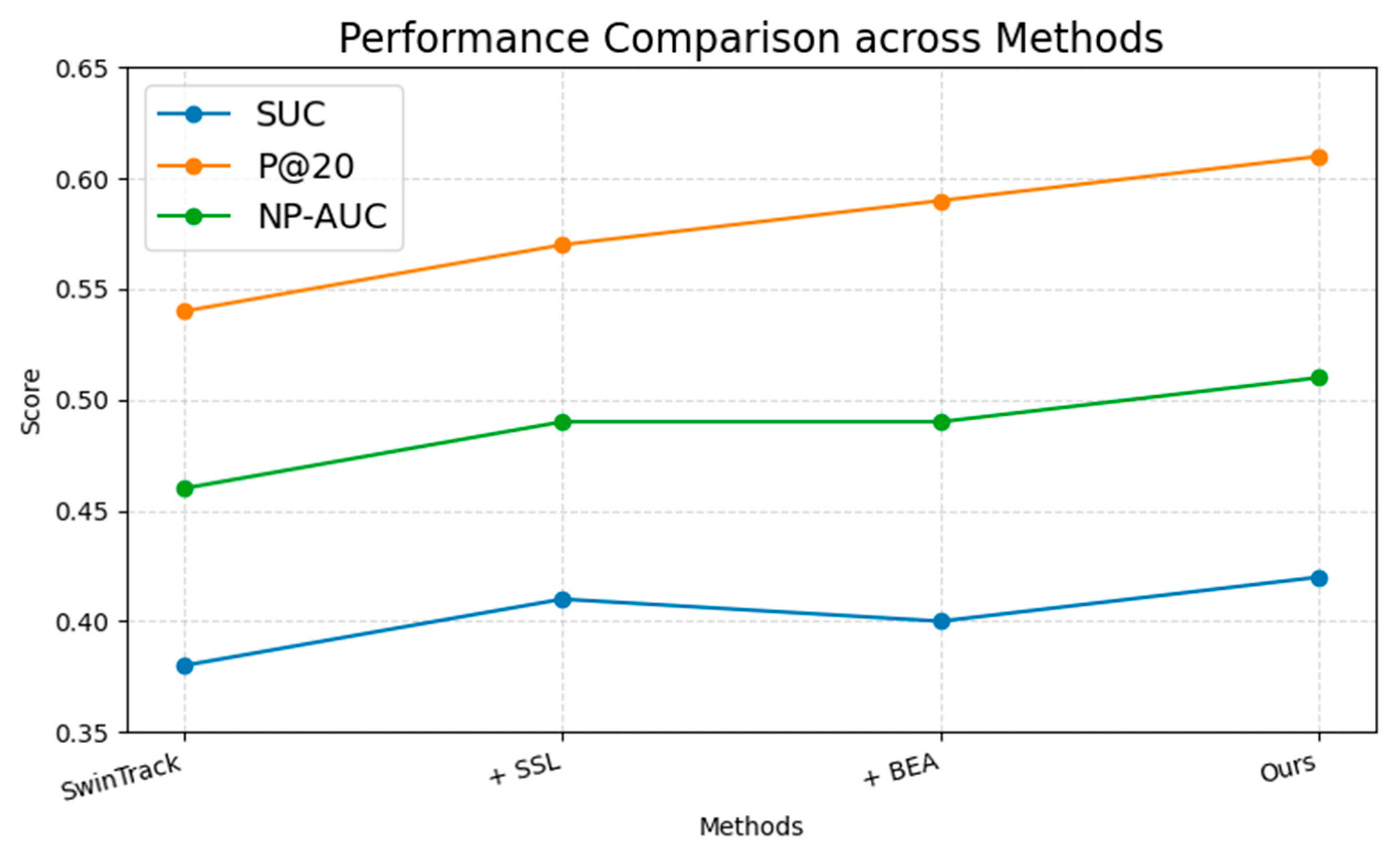

The overall results are shown in

Figure 11 and

Table 1. Compared to the baseline SwinTrack, using SSL alone provides a stable improvement in all three metrics. These gains further demonstrate that in cross-domain weak target tracking tasks, the consistent pseudo-label selection strategy combined with mutually refined iterative training can suppress the impact of early noise on pseudo-label quality, thus making the cross-domain capability more robust. Meanwhile, when using BEA alone, the improvements in P@20 and NP-AUC are more significant than the slight improvement in SUC: due to the strategy of regressing to the original box based on the classification reference augmentation box, the classification heatmap is more likely to form repeatable and sharp peaks in a more relevant and stable context, thereby improving normalization accuracy while reducing center point quantization error. Since the geometric caliber of the regression strategy remains unchanged, the overall IoU area, i.e., SUC, shows a moderate upward trend.

When the aforementioned SSL and BEA work together on the baseline (i.e., Ours), the three metrics are further improved: SSL provides high-quality pseudo-label signals for cross-domain mutual refinement training, thereby reducing the drift phenomenon caused by occlusion or shape deformation, while BEA provides more robust background information for each match as local upper and lower anchor points, thereby alleviating the limitation of effective information of weak targets themselves.

4.5. Comparison with Other Methods

This section presents comparative experiments on the proposed method’s ability to generalize to weak targets and across domains. The target test domain is uniformly set to the self-made dataset T2. The target domain used for generating pseudo-labels in the initial model inference for mutual supervision is set to the self-made dataset T1. Representative strong baselines from the same period are selected as comparison objects. Without additional post-processing at the inference end, both the proposed method and the baseline are tested on T2, and the following comparative experimental results are obtained.

As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 12, the morphological characteristics of the three curves demonstrate that the proposed method significantly improves tracking performance in scenes with small targets. Specifically, the pseudo-label refining method effectively suppresses pseudo-label noise during training and utilizes relatively high-quality pseudo-labels for mutual supervision, thereby enhancing the overall generalization ability of the model. Furthermore, the background enhancement box method reduces pixel-level center error, thus improving P@20. When the background textures of the source and target domains differ significantly, SSL ensures a stable improvement in the model’s generalization ability through improved pseudo-label quality. BEA, by providing stable background information, reduces model drift even in the event of slight occlusion or morphological deformation, thus ensuring overall performance improvement.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the limitations of effective information from small targets and the generalization ability of models in the field of small target tracking. Focusing on the research topic of small target tracking technology for low-altitude UAVs, it proposes a cross-domain self-training architecture for small target tracking, based on the SwinTrack as the baseline backbone network, which enhances the model’s generalization ability through mutual refinement. A complete technical system is comprehensively constructed, from theoretical framework modeling, algorithm design, experimental verification, to final engineering deployment. The baseline comparison video is publicly available at the following URL:

https://github.com/yangchuanyuan/SwinMR (accessed on 3 November 2025). Specifically, it can be summarized as follows:

1. This paper first clarifies the problems of limited effective information and weak model generalization ability caused by the size of small targets. To address these problems, it first establishes the powerful feature extraction and self-attention mechanism of the Swin Transformer as the backbone network baseline architecture, laying the foundation for subsequent improvements.

2. To address the problem that each training set requires manual annotation to obtain satisfactory results due to the weak model generalization ability, this paper designs a mutual refinement iterative training mode based on the SwinTrack as the baseline architecture, inspired by MMT. This architecture introduces a dual-branch network into the field of small target tracking. Through mutual learning using pseudo-labels generated by the teacher model and filtered for consistency and then fused with unique identifiers, the model gradually adapts to the distribution of the target domain during continuous iteration, thereby improving its generalization ability.

3. To address the limitation of effective information caused by the scale of small targets, this paper proposes a Background Enhancement (BEA) strategy. This strategy utilizes the high background repetition rate between neighboring frames to expand the target bounding box by a uniform ratio, thus using the neighborhood background as effective information to improve the localization accuracy and tracking performance of small targets. The advantages of the BEA strategy and its robustness in feature discrimination are demonstrated in feature response visualization.

Although the proposed small target tracking framework has achieved good performance and is feasible for engineering deployment, several problems still need to be solved, and further research is needed to find solutions. Future work should focus on further improving model lightweighting, generalization ability, adaptability, and system synergy to promote the comprehensive development of the field of small target tracking.

While the model’s structural optimization and lightweighting have been successfully ported to airborne computers, the required computing power is still insufficient for performing flight processing tasks in the air and requires further optimization. Future research could combine strategies such as dynamic pruning, knowledge distillation, or hybrid precision quantization to improve this problem. At the same time, it is also possible to consider combining edge computing or heterogeneous acceleration with a multi-level distributed inference architecture, that is, dividing the task level to the sensing layer, thereby improving the overall energy efficiency of the UAV architecture.