Abstract

In this study, a battery case was developed using a 3D (three dimensional)-printed composite of hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) and polylactic acid (PLA) to enhance the thermal performance of lithium-ion battery (LiB) modules. A 10 wt.% amount of hBN was incorporated into the PLA matrix to improve the composite’s thermal conductivity while maintaining electrical insulation. A 3S2P (3 series and 2 parallel) battery configuration was initially evaluated based on the results of a baseline study for comparison and subsequently subjected to a newly developed test procedure to assess the thermal behavior of the designed case under identical environmental conditions. Initially, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses were utilized for material characterization, and their results verified the successful integration of hBN by confirming its presence in the hBN-PLA composite. In thermal tests, experimental results revealed that the fabricated hBN-PLA composite battery case significantly enhanced heat conduction and reduced surface temperature gradients compared to the previous baseline study with no case. Specifically, the maximum cell temperature (Tmax) decreased from 48.54 °C to 45.84 °C, and the temperature difference (ΔT) between the hottest and coldest cells was reduced from 4.65 °C to 3.75 °C, corresponding to an improvement of approximately 20%. A 3S2P LiB module was also tested under identical environmental conditions using a multi-cycle charge–discharge procedure designed to replicate real electric vehicle (EV) operation. Each cycle consisted of sequential low and high discharge zones with gradually increased current values from 2 A to 14 A followed by controlled charging and rest intervals. During the experimental procedure, the average ΔT between the cells was recorded as 2.38 °C, with a maximum value of 3.50 °C. These results collectively demonstrate that the 3D-printed hBN-PLA composite provides an effective and lightweight passive cooling solution for improving the thermal stability and safety of LiB modules in EV applications.

1. Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) have become one of the key components of sustainable transportation due to their potential to reduce environmental impacts and improve energy efficiency. In addition, they provide several practical advantages, including lower operating costs, reduced noise emissions, and the opportunity for integration with renewable energy systems. The battery is the core component of EVs, acting as the main energy storage system that determines performance, driving range, charging time, and overall cost. Among the various battery technologies, lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) have become the dominant choice due to their high energy density, long cycle life, relatively low self-discharge rate, and favorable balance between cost and performance [1,2,3]. However, LiBs still face significant challenges. These include thermal management problems, safety risks related to overheating and thermal runaway, high production costs, and limited recyclability [4,5,6]. Such issues highlight the obvious need for further research and development efforts. Among all of these, excessive heat generation and the resulting thermal management problems are particularly critical. Elevated temperatures can negatively affect battery performance and life, while also posing serious safety risks such as overheating and thermal runaway [7]. Thermal runaway is one of the most severe consequences of uncontrolled heat accumulation and it represents a chain reaction that endangers safety and can ultimately result in fire or explosion [8]. To address these challenges, researchers have focused on developing battery thermal management systems (BTMSs) that keep cell temperatures within a safe and efficient range while simultaneously improving performance and safety.

BTMSs are typically classified as active or passive systems. Active systems require an external energy source and typically employ devices such as fans for air cooling or pumps for liquid cooling. Passive systems do not need additional energy input and instead rely on materials or design solutions such as phase change materials (PCMs) or heat sinks to manage heat [9].

The battery case is important not only for mechanical protection but also for thermal regulation and overall performance. In passive cooling, the case material and design may directly affect heat dissipation. A case material with higher thermal conductivity helps dissipate heat more evenly while reducing temperature rise and improving safety. Polylactic acid (PLA) has attracted attention as a potential battery case material due to its biodegradability, low cost, ease of processing, light weight, and electrical insulation properties [10,11]. However, PLA has relatively low thermal conductivity compared to metals but still higher than air (~0.13 W/mK) [12]. This property makes it more effective than air cooling, yet it is still insufficient for demanding LiB applications that require enhanced heat dissipation. To overcome this drawback, hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) can be incorporated into the PLA matrix. hBN offers high thermal conductivity while maintaining electrical insulation, which makes it suitable for enhancing heat dissipation and safety in battery applications [13]. hBN was selected as a functional additive because of its unique combination of high thermal conductivity (300–2000 W/m·K), excellent electrical insulation (~1016–1018 Ω·cm), and chemical stability. Unlike metallic fillers, hBN does not compromise the dielectric strength of the composite or introduce electrical hazards. In addition, its two-dimensional layered crystal structure facilitates anisotropic heat conduction when dispersed within the polymer matrix, improving the directional heat transfer capability of the printed structure. These characteristics make hBN an ideal candidate for enhancing both the safety and thermal performance of LiB casings.

The development of thermally conductive polymer composites for additive manufacturing has undergone a significant transformation over the last two decades, evolving from fundamental filament fabrication to highly integrated, multifunctional systems. Early research by Masood and Song [14] introduced one of the first metal–polymer composite filaments for fused deposition modeling (FDM), composed of iron particles dispersed within a polyamide matrix. Their study not only demonstrated the feasibility of directly producing tooling inserts for injection molding but also validated theoretical thermal conductivity models such as Nielsen and Cheng–Vochen, which accurately predicted the heat transfer behavior of metal-filled polymers. Building upon this groundwork, Hwang et al. [15] developed acrylonitrile/butadiene/styrene (ABS) composites containing copper and iron powders to investigate their thermo-mechanical performance under various FDM printing conditions. Their results revealed a trade-off between mechanical and thermal properties: tensile strength decreased with higher metal loading due to void formation and weaker interlayer adhesion, while thermal conductivity increased by 41% at 50 wt.% copper addition. The transition from metallic to ceramic fillers marked a new phase in additive manufacturing for thermal management applications. Quill et al. [16] examined boron nitride (BN)-reinforced ABS composites produced by both injection molding and 3D printing. Although injection-molded test specimens achieved superior thermal conductivity (1.45 W/mK) and mechanical strength, the 3D-printed parts still exhibited a fivefold enhancement in heat conduction relative to neat ABS. The study also revealed anisotropic heat transfer behavior arising from the layer-by-layer deposition mechanism intrinsic to FDM. The anisotropic heat conduction mechanism was further refined by Liu et al. [17], who fabricated thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) composites containing aligned hBN flakes. Utilizing the shear forces inherent in FDM, in their research, Liu et al. achieved directional alignment of the fillers, yielding a thermal conductivity of 2.56 W/mK along the printing direction-approximately ten times that of pure TPU. Beyond conventional polymers, Guiney et al. [18] introduced a 3D-printable nanocomposite ink comprising poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and up to 60 vol% hBN, capable of room-temperature extrusion. The printed structures exhibited a thermal conductivity of 2.1 W/mK at 40 vol% hBN while retaining flexibility and cytocompatibility. More recently, An et al. [19] proposed a hybrid BTMS that combines PCM with 3D-printed metal scaffolds and internal liquid-cooling channels. Through simulation and experimental validation, they achieved a 60% mass reduction compared to conventional aluminum heat sinks while maintaining cell temperatures below 48.1 °C and a gradient under 2.6 °C during high-speed cycling.

Although previous studies have examined 3D-printed composites for electronic cooling, there is still limited research exploring their use as battery casing materials for passive BTMS applications. So, this study introduces a novel and cost-effective 3D printing approach for fabricating hBN reinforced PLA composites as battery case materials with the aim of improving passive thermal management and enhancing the safety of the LiB module. PLA is biodegradable and highly compatible with additive manufacturing, but it suffers from low thermal conductivity, which limits its effectiveness in heat management. However, this study uniquely integrates 10 wt.% hBN into PLA via FDM to create a lightweight, thermally conductive, and electrically insulated structure that is experimentally validated through thermal performance testing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Battery Thermal Test Rig

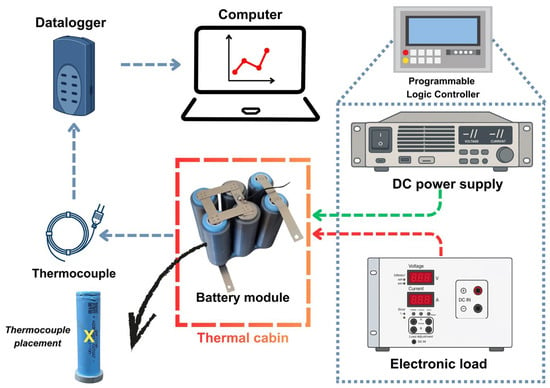

The LiB used in the experiments was an Aspilsan INR18650A28 cell (Aspilsan, Kayseri, Türkiye) featuring a nominal voltage of 3.65 V and a capacity of 2800 mAh for producing 3S2P battery module. The cell offers a gravimetric energy density of 230 Wh/kg and a volumetric energy density of 605 Wh/L. For load testing, a Heliocentris EL 1500 programmable electronic load (Heliocentris, Berlin, Germany) was employed, it is capable of handling up to 1500 W with a voltage range of 1–75 V and current up to 100 A. Power supply for charging experiments was provided by a GW Instek PSU 100-15 programmable DC source (Good Will Instrument Co., Ltd., New Taipei, Taiwan), rated at 100 V/15 A and 1500 W output power. The unit offers a fast-transient response (~1 ms), ensuring accurate control of current and voltage during charging cycles. Temperature measurements were collected using a Pico TC-08 data logger (Pico Technology Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK), which supports eight thermocouple channels with a temperature accuracy of ±0.5 °C and a sampling rate up to 10 readings s−1. Type-T thermocouples (Pico Technology Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK), providing an operating range of −75 °C and 260 °C, were mounted directly on the center of each cell’s outer surface using high-conductivity thermal adhesive to ensure intimate contact and accurate surface temperature detection. A schematic representation of the complete test rig is shown in Figure 1, illustrating the electronic load, data acquisition unit, thermocouple placement, and electrical connections. All measurements were performed in a controlled laboratory environment with minimal air flow to eliminate external convection effects.

Figure 1.

The schematic of the test rig.

This configuration allowed continuous and synchronized recording of temperature and current data throughout charge–discharge cycles, enabling precise comparison between baseline and composite case conditions.

2.2. Production Process of hBN Reinforced PLA Filament and 3D Printing

The composite filament was manufactured through a two-step extrusion process. First, PLA (Luminy, TotalEnergies Corbion, Rayong, Thailand) with a density of 1.24 g/cm3 and a melt flow index (MFI) of 8 g/10 min (measured at 210 °C and 2.16 kg load) and hBN powders (Nanografi, Ankara, Türkiye; purity ≥ 99%; particle size 30–40 µm) were premixed and processed using a co-rotating twin-screw extruder (GM Twin 16/48, Gülnar Makine, Kayseri, Türkiye) operating at 100 rpm. The temperature profile across the three mixing zones was set to 175–190–205 °C, ensuring efficient melting, dispersion, and homogenization of hBN within the PLA matrix.

The extrudate was cooled in a water bath, pelletized, and subsequently dried in a hot-air oven at 50 °C for 6 h to eliminate residual moisture. The dried pellets were then processed in a single-screw extruder (GM Single 30/24, Gülnar Makine, Kayseri, Türkiye) operating at 20 rpm, using the same temperature profile of 175–190–205 °C. This extrusion line was equipped with a feedback-controlled diameter monitoring system, allowing the production of filaments with a dimensional tolerance of ±0.03 mm. The resulting filaments exhibited consistent geometry and uniform dispersion of hBN throughout the PLA matrix, making them suitable for FDM applications.

As shown in previous studies [20,21], 10 wt.% hBN addition into PLA was selected due to the optimal ratio to obtain improved thermal conductivity and better printability. On the other hand, at loadings below 5 wt.% insufficient percolation of BN platelets occurs and there was a deterioration in thermal conductivity. In contrast, higher contents above 15 wt.% lead to nozzle clogging, reduced filament extrusion stability, and worsening of layer adhesion in FDM printing.

Although direct measurements of density, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity were not performed in the present study, the thermophysical behavior of hBN/PLA composites at similar doping is well documented in the literature. For 5–15 wt.% hBN, the composite density typically increases only slightly from 1.24 g/cm3 to approximately 1.27–1.30 g/cm3, while the specific heat capacity remains in the range of 1700–1900 J/kg·K, close to that of pure PLA [21]. In contrast, thermal conductivity shows a more substantial improvement, rising from ~0.13 W/m·K (pure PLA) to 0.25–0.35 W/m·K at 10 wt.% hBN. These literature-reported values are consistent with the experimental temperature trends observed here, particularly the pronounced reduction in temperature difference (ΔT), which is indicative of improved lateral heat spreading.

The hBN/PLA filaments were employed in an Ender-3 S1 3D printer (Creality, Shenzhen, China) to fabricate a customized cylindrical holder designed for a 3S2P INR18650A28 LiB configuration. The detailed 3D-printing parameters used for fabricating the hBN-PLA case are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

3D printing parameters used for fabrication of hBN/PLA battery case.

The 3D model was designed in a computer-aided design (CAD) environment. The case geometry was optimized to maintain uniform wall thickness around each cell cavity and to allow adequate air circulation between cells. A grid infill pattern with 70% density was chosen to provide mechanical rigidity. Dimensional uniformity of the printed hBN-PLA case was verified through both visual inspection and basic dimensional measurements. In addition to confirming the absence of warping, delamination, or surface defects, key geometric features such as cell cavity diameters and wall thicknesses were measured using digital calipers, showing deviations within ±0.2 mm of the CAD model. Furthermore, the filament extrusion system employed for composite fabrication incorporates a real-time diameter control unit with a tolerance of ±0.03 mm, ensuring consistent filament geometry prior to printing. The small circular indentations visible on the surface are not printing artifacts but purposely drilled micro-holes used for thermocouple placement during thermal measurements (Figure 2). A tight fit was designed between the cylindrical cells and the printed hBN-PLA case channels, and no thermally conductive adhesive was applied; thus, thermal contact occurred only through direct contact between the battery case and cell surfaces.

Figure 2.

Printed hBN/PLA battery case.

2.3. Characterizations of hBN-PLA

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Carl Zeiss, Gemini SEM 500-71-08, Oberkochen, Germany) were used to observe the morphology of hBN-PLA and 3D printed samples. The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) results were obtained on a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5405 Å). To show the influence of hBN distribution on XRD patterns, the sample was tested under the conditions of scanning angle between 10° and 80° with a dimension of 10 × 10 × 2 mm3.

2.4. Test Procedure

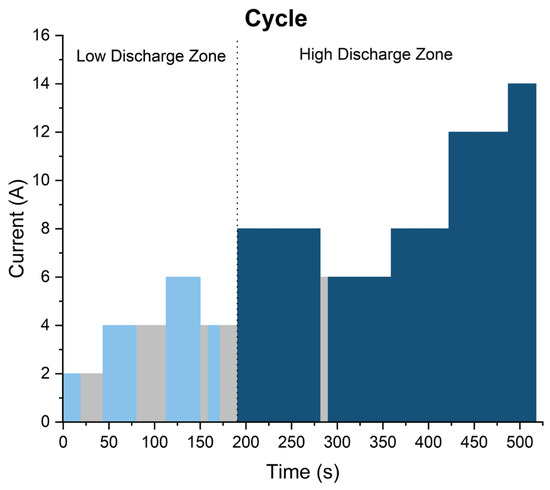

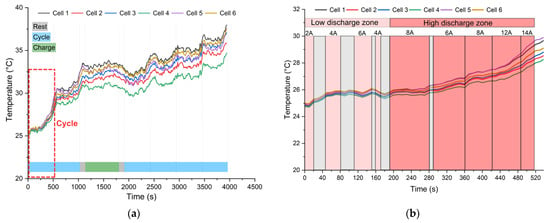

Prior to initiating the test, the hBN-PLA battery case was evaluated using a 3S2P battery configuration, similar to that used in the previous study [22]. All multi-cycle charge–discharge experiments were conducted inside a Proportional Integral Derivative (PID)-controlled isolated thermal cabin maintained at 25 ± 0.5 °C to ensure stable and homogeneous ambient conditions throughout the tests. The cabin actively regulated the environmental temperature, enabling a reliable comparison of thermal responses between the baseline and hBN-PLA battery case configurations. Each cycle in the test procedure consisted of two stages: a low discharge zone and a high discharge zone. In the low discharge zone, the cell was discharged sequentially at 2 A, 4 A, and 6 A with intermediate rest periods. In the high discharge zone, discharge currents of 6 A, 8 A, 12 A, and 14 A were applied following short rest intervals. The total duration of a single cycle was approximately 517 s. In the test procedure, two consecutive cycles were performed, followed by a 120 s rest, a 6 A charging period for 600 s, and another 120 s rest before continuing with four subsequent cycles. All temperature data were continuously recorded using the PicoLog version 6.2.13. software interface. All thermocouples were mounted at the center of the outer cylindrical surface of each cell to ensure identical measurement locations. Additionally, a schematic illustration in Figure 1 visually presents the thermocouple positions. Besides that, the experimental setup, thermocouple placement, and all testing conditions were kept strictly identical to those reported in [22], thereby ensuring direct comparability between the baseline and composite case configurations. Each measurement point represents the average of three consecutive readings to minimize random noise. The uncertainty of temperature measurement was estimated at ±0.5 °C. The cycle details are illustrated in Figure 3. Within each cycle, the columns representing the low discharge zone are shown in light blue, the columns corresponding to the high discharge zone are shown in dark blue, and the columns indicating the rest intervals between successive current steps are shown in gray.

Figure 3.

Test procedure details.

This comprehensive test protocol was specifically designed to simulate real-world operating conditions of EV battery modules, capturing both mild and severe thermal loading scenarios. By maintaining consistent ambient conditions and repeating identical discharge cycles, the influence of the hBN-PLA battery case on thermal performance could be quantitatively evaluated with high reliability.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of hBN-PLA Composites

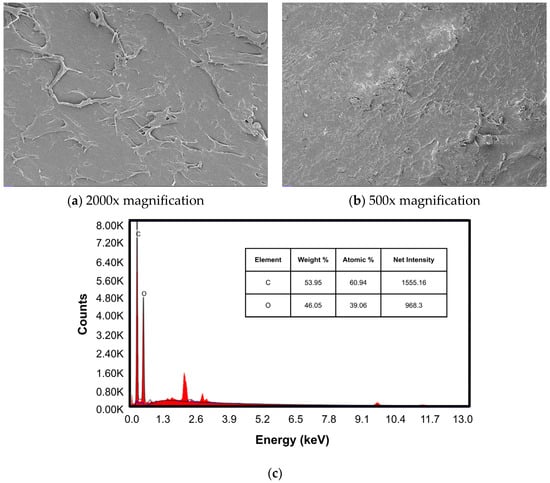

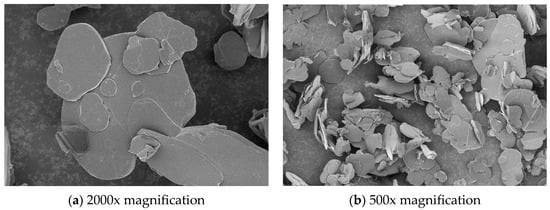

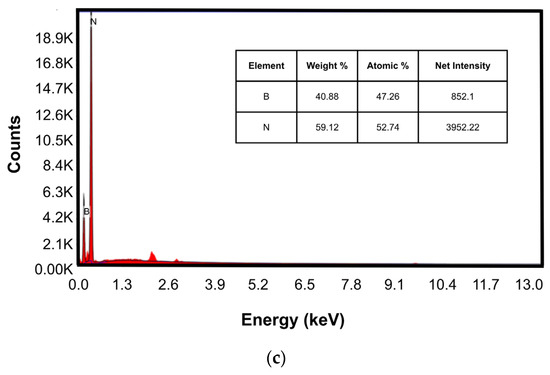

The raw materials were characterized prior to filament production. SEM images of PLA granules (Figure 4a,b) revealed relatively smooth polymeric surfaces with fibrillar microstructures, while Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed that PLA consists primarily of carbon (53.95 wt.%) and oxygen (46.05 wt.%) (Figure 4c). In contrast, hBN particles (Figure 5a,b) exhibited a typical lamellar, plate-like morphology, consistent with their hexagonal crystalline nature. The elemental composition of hBN was further validated by EDS (Figure 5c), which showed boron (~40.88 wt.%) and nitrogen (~59.12 wt.%) contents in near-stoichiometric proportions.

Figure 4.

(a,b) SEM images of PLA granules at different magnifications; (c) EDS spectrum of PLA.

Figure 5.

(a,b) SEM images of hBN particles at different magnifications; (c) EDS spectrum of hBN.

The combination of these analyses confirms the purity and suitability of both raw materials for composite fabrication. The distinct surface topographies of hBN and PLA also indicate potential for strong interfacial interaction, as the layered morphology of hBN can promote effective thermal pathways when well-dispersed in the PLA matrix [23]. Such morphological compatibility is crucial for achieving homogeneous filler distribution during extrusion and minimizing interfacial thermal resistance [24].

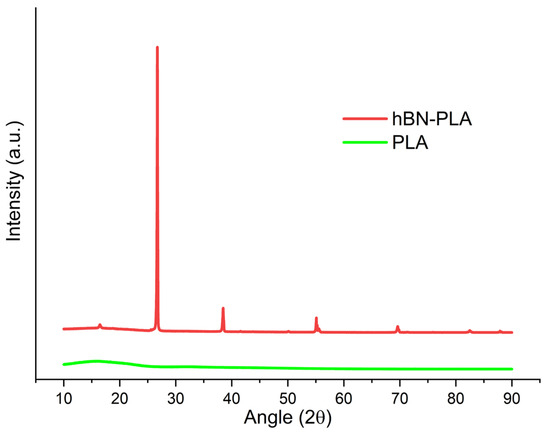

The XRD pattern of the hBN-PLA sample (Figure 6) exhibits sharp and well-defined diffraction peaks characteristic of crystalline hBN. The highly intense reflection at approximately 2θ~26.7° corresponds to the (002) plane of hBN, indicating a pronounced layered structure. Additional weaker reflections observed at higher diffraction angles confirm the presence of hBN within the PLA matrix (ref. code 98-002-0946). No additional diffraction peaks associated with PLA degradation or phase transformation were observed, suggesting that the polymer’s original semi-crystalline structure remained intact after hBN incorporation and FDM processing. This indicates good chemical compatibility and thermal stability between hBN and PLA during extrusion and printing. Moreover, the persistence of the (002) peak implies that the basal planes of hBN remained largely intact, allowing them to serve as continuous thermally conductive channels within the polymer matrix. Such preserved crystal integrity plays a crucial role in enhancing anisotropic heat conduction through the printed structure. These findings align with previous studies in which the retention of hBN crystallinity after melting processing was correlated with improved thermal performance in composite systems [25,26].

Figure 6.

XRD pattern of the PLA and hBN-PLA samples.

3.2. Thermal Performance Analysis

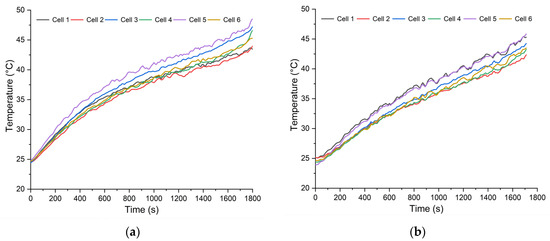

The temperature evolution of individual cells over time under identical discharge conditions is presented in Figure 7. Figure 7a shows the data from a previous study, where the cells were discharged at a 2C rate in an environmental temperature maintained at 25 °C. According to the graph, the maximum cell temperature (Tmax) was recorded in Cell 5, reaching 48.54 °C, while Cell 1 exhibited the lowest temperature, at 43.42 °C. Figure 7b shows the results obtained using the hBN-PLA battery case developed in the current study, tested under the same environmental conditions and discharge rate. In this case, Cell 5 again reached the highest temperature of 45.84 °C, while Cell 2 recorded the lowest temperature at 42.34 °C. Specifically, compared to the previous setup, Tmax is reduced by 2.7 °C.

Figure 7.

(a) Previous study [22], (b) hBN-PLA experiment results.

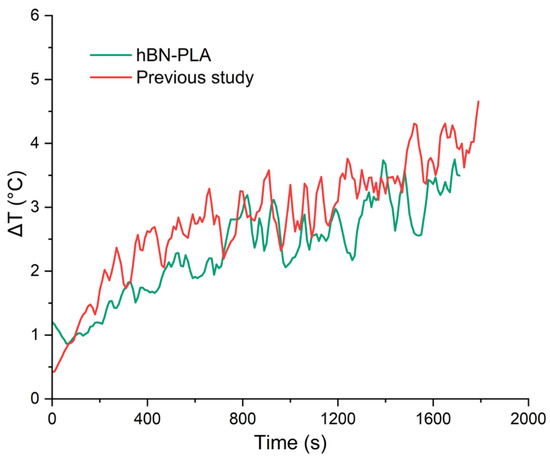

ΔT variations in the hBN-PLA battery case and the previous study as a function of time are given in Figure 8. As seen, ΔT increases with time for both tests; however, the rate and magnitude of increase differ noticeably. The hBN-PLA battery case exhibits a more stable and moderate temperature rise throughout the test, maintaining a maximum ΔT of 3.75 °C. In contrast, the previous study shows a higher and more fluctuating temperature response, reaching ΔT values of 4.65 °C. A lower ΔT value implies a more homogeneous temperature field among the six cells, reducing the risk of local thermal hotspots and subsequent degradation of individual cells. The improvement of approximately 20% in ΔT demonstrates the capability of the hBN-PLA battery case to equalize thermal gradients across the pack. This is particularly important since uneven temperature distribution accelerates aging in LiB cells and can cause unbalanced charging behaviors.

Figure 8.

ΔT variations over time.

The comparatively modest reduction in Tmax (5.5%), accompanied by a more pronounced improvement in ΔT (~20%) suggests that the hBN-PLA case primarily enhances lateral heat spreading between cells rather than merely increasing the overall thermal mass of the module. Since all tests were performed under identical ambient conditions with minimized air flow, the external convective heat transfer area and coefficient can be considered approximately constant. Therefore, the dominant mechanism behind the improved temperature uniformity is the additional conductive pathway provided by the hBN-PLA structure, which redistributes internally generated heat more evenly across the pack.

Figure 9 presents the temperature evolution of six cells of a 3S2P battery module during the rest, cycling, and charging phases. At the beginning of the test, all cells show nearly identical temperatures around 25 °C, confirming uniform initial conditions. As cycling progresses, the temperature gradually increases, with a more pronounced rise observed during the high discharge zone, where current intensity reaches 14 A. Among the cells, slight temperature variations are observed, with Cell 1 and Cell 6 exhibiting higher values than the others. During the test procedure, the average ΔT between the cells was recorded as 2.38 °C, with a maximum value of 3.50 °C observed at approximately 3500 s. At the end of the test, the battery module reached a Tmax of 37.96 °C and a minimum cell temperature (Tmin) of 34.70 °C, resulting in an overall ΔT of 3.26 °C. These results show that the hBN-PLA battery case helped keep the temperature distribution uniform during the test procedure.

Figure 9.

(a) Temperature variation during test procedure, (b) enlarged first cycle temperature variation.

Throughout multiple charge–discharge cycles, the hBN-PLA battery case exhibited consistent thermal performance without any signs of structural deformation or loss of integrity. The material’s dimensional stability during the test procedure confirms its suitability for real-world applications in EVs. Additionally, the absence of delamination or interfacial gaps indicates excellent adhesion between the composite case and the cylindrical cell surfaces, ensuring reliable long-term thermal contact.

4. Discussions

The experimental results illustrate that the hBN-PLA composite material can effectively reduce local thermal gradients and lower the overall temperature rise in LiB modules, thereby contributing to safer and more stable operation. The results also validate the potential of additive manufacturing as a practical and flexible approach to produce customized, thermally conductive polymer components for battery systems.

Compared with traditional metal-based or active cooling solutions, the proposed design provides a lightweight, energy-efficient, and cost-effective passive cooling alternative. Furthermore, the 3D-printable nature of the composite allows geometry optimization for various battery configurations, offering scalability for EV applications.

Despite the clear importance of comparative evaluation in battery thermal management research, establishing fully identical experimental conditions across independent studies remains inherently challenging due to unavoidable variations in cell type, material composition, discharge protocols, thermal boundary conditions, and sensor positioning. These parameters are commonly tailored to the specific objectives, material systems, and laboratory infrastructures of each investigation, rendering standardized one-to-one replication impractical. Owing to these methodological differences, direct quantitative comparison with the present experimental setup is not appropriate. Therefore, a qualitative evaluation approach is adopted. In one study, graphene-filled TPU composites produced by additive manufacturing achieved through-plane thermal conductivities of up to 12 W/mK through vertically aligned microstructures [27]. In a different approach, nanoparticle-enhanced PCM systems combined with active cooling reported Tmax reductions of up to 26.98% by optimizing PCM thickness and filler content [28]. In another investigation, purely passive PCM-based cooling demonstrated approximately 3.5 °C lower ΔT compared to no-cooling conditions at the pack level [9]. More recently, jute fiber-reinforced PCM systems further reduced Tmax from 47.27 °C to 36.29 °C under aggressive discharge operation [29]. Within this framework, the present results demonstrate that the 3D-printed hBN-PLA battery case provides consistent temperature suppression and improved thermal uniformity under various test conditions. Moreover, this performance is achieved without relying on latent heat storage or active cooling mechanisms, showing that it can serve as a practical and scalable fully passive cooling solution for EV battery applications.

For the 3S2P module examined, the six INR18650A28 cells have a total mass of approximately 267 g, whereas the 3D-printed hBN-PLA battery case weighs 56.51 g, corresponding to a ~21% increase in module mass and a reduction in cell base gravimetric energy density from ~230 Wh/kg to ~190 Wh/kg. This comparison, however, is made against an idealized configuration without any busbars, mechanical housing, or thermal management components, all of which are inherently present in real EV battery modules. In practice, the hBN-PLA structure can be designed to replace a portion of this existing hardware rather than being added redundantly.

Scaling the same architecture to approximately 60 kWh battery pack for commercial EV requires nearly 1000 such sub-modules, corresponding to a cumulative hBN-PLA mass of roughly 56 kg. For a typical EV with a total vehicle mass of 1900–2100 kg, this represents an increase in only about 2.8% at the vehicle level. In contrast, the ~20% improvement in temperature uniformity demonstrated in this study provides meaningful benefits in terms of thermal stability, safety, and cycle life. Therefore, the trade-off between a marginal increase in structural mass and a substantial enhancement in passive thermal management is considered acceptable for practical EV applications, indicating that the additional mass introduced by the composite structure remains reasonable with respect to overall system performance.

5. Conclusions

A 3D-printed hBN-PLA battery case was successfully developed to improve the passive thermal management of LiBs. The main findings are summarized as follows:

XRD analysis of the hBN-PLA composite revealed sharp and well-defined diffraction peaks, particularly at 2θ~26.7°, corresponding to the (002) plane of hBN, confirming the crystalline structure and successful dispersion of hBN within the polymer matrix.

While the baseline configuration reached a Tmax of approximately 48.54 °C, the hBN-PLA battery case remained at a lower temperature level of 45.84 °C, corresponding to a 5.5% reduction in Tmax.

Moreover, the ΔT decreased from 4.65 °C to 3.75 °C, representing approximately 20% improvement in temperature uniformity. Incorporation of 10 wt.% hBN into the PLA matrix significantly improves the thermal management capability.

Future work will focus on (i) experimentally determining the effective thermal conductivity of the composite structure, (ii) investigating filler alignment and interfacial thermal resistance through microstructural analysis, and (iii) integrating numerical thermal simulations to further optimize geometry and material composition. These efforts aim to establish a comprehensive design framework for polymer-based passive thermal management systems in high-power battery modules.

While the addition of hBN as a filler effectively enhances the thermal conductivity of PLA, it may also increase the brittleness of the structure, which can potentially affect the mechanical durability. Possible mitigation strategies of this disadvantage include the use of interfacial modifiers or toughening agents to improve interfacial bonding for the development of hybrid composite systems combining hBN. In this context, future work directions have also been updated to include comprehensive mechanical testing (tensile, flexural, impact, and fatigue assessments) to quantify durability limits and optimization for balanced thermo-mechanical performance.

Future studies will also include long-term thermal aging tests, cyclic thermal–mechanical loading, and evaluation of hBN dispersion stability under prolonged exposure to real EV operating conditions in order to validate the long-term mechanical integrity and thermal functionality of the composite casing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.Y., A.P., M.İ. and M.Ö.; methodology, E.T., S.K. and M.İ.; software, M.I.B.; validation, A.C.Y. and M.I.B.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, E.T., S.K. and A.C.Y.; data curation, S.K. and A.C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.Y., A.P., M.I.B. and M.İ.; writing—review and editing, E.T., S.K., A.P. and M.Ö.; visualization, A.C.Y. and M.I.B.; supervision, A.P. and M.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| BTMS | Battery thermal management system |

| LiB | Lithium-ion battery |

| PCM | Phase change material |

| FDM | Fused deposition modeling |

| hBN | Hexagonal boron nitride |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| Tmax | Maximum temperature |

| ΔT | Temperature difference |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| PID | Proportional integral derivative |

References

- Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; Dai, Z.; Wen, Y.; Jiang, L. Cycle Life Studies of Lithium-Ion Power Batteries for Electric Vehicles: A Review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 93, 112231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kassar, R.; Al Takash, A.; Faraj, J.; Hammoud, M.; Khaled, M.; Ramadan, H.S. Recent Advances in Lithium-Ion Battery Integration with Thermal Management Systems for Electric Vehicles: A Summary Review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 91, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placke, T.; Kloepsch, R.; Dühnen, S.; Winter, M. Lithium Ion, Lithium Metal, and Alternative Rechargeable Battery Technologies: The Odyssey for High Energy Density. J. Solid. State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 1939–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C. Thermal Runaway Caused Fire and Explosion of Lithium Ion Battery. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubi, G.; Dufo-López, R.; Carvalho, M.; Pasaoglu, G. The Lithium-Ion Battery: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibin, C.; Vijayaram, M.; Suriya, V.; Sai Ganesh, R.; Soundarraj, S. A Review on Thermal Issues in Li-Ion Battery and Recent Advancements in Battery Thermal Management System. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shang, C.; Li, H.; Ma, L.; Fu, M. Study on the Effects of High/Low-Temperature upon the Thermal Runaway Behaviors and Characteristics of Lithium-Ion Batteries Used in Portable Power Banks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 128084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhauer, T.M.; Garimella, S.; Fuller, T.F. A Critical Review of Thermal Issues in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, M.W.; Iqbal, N.; Ali, M.; Nazir, H.; Amjad, M.Z. Bin Thermal Management of Li-Ion Battery by Using Active and Passive Cooling Method. J. Energy Storage 2023, 61, 106800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Zinjarde, S.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Polylactic Acid: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homavand, A.; Cree, D.E.; Wilson, L.D. Polylactic Acid Composites Reinforced with Eggshell/CaCO3 Filler Particles: A Review. Waste 2024, 2, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamirad, G.; Montazeri, A.; Rajabpour, A. Enhanced Interfacial Thermal Conductance in Functionalized Boron Nitride/Polylactic Acid Nanocomposites: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 186, 108037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorur, M.C.; Doganay, D.; Durukan, M.B.; Cicek, M.O.; Kalay, Y.E.; Kincal, C.; Solak, N.; Unalan, H.E. 3D Printing of Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets/Polylactic Acid Nanocomposites for Thermal Management of Electronic Devices. Compos. B Eng. 2023, 265, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, S.H.; Song, W.Q. Thermal Characteristics of a New Metal/Polymer Material for FDM Rapid Prototyping Process. Assem. Autom. 2005, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Reyes, E.I.; Moon, K.; Rumpf, R.C.; Kim, N.S. Thermo-Mechanical Characterization of Metal/Polymer Composite Filaments and Printing Parameter Study for Fused Deposition Modeling in the 3D Printing Process. J. Electron. Mater. 2015, 44, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quill, T.J.; Smith, M.K.; Zhou, T.; Baioumy, M.G.S.; Berenguer, J.P.; Cola, B.A.; Kalaitzidou, K.; Bougher, T.L. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Boron Nitride—ABS Composites. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2018, 25, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. Improved Thermal Conductivity of Thermoplastic Polyurethane via Aligned Boron Nitride Platelets Assisted by 3D Printing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 120, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiney, L.M.; Mansukhani, N.D.; Jakus, A.E.; Wallace, S.G.; Shah, R.N.; Hersam, M.C. Three-Dimensional Printing of Cytocompatible, Thermally Conductive Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanocomposites. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 3488–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gao, W.; Liu, H.; Gao, Z. Lightweight Hybrid Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Management System Based on 3D-Printed Scaffold. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 110141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavamurthy, R.; Tambrallimath, V.; Patil, S.; Rajhi, A.; Duhduh, A.; Khan, T. Mechanical and Wear Studies of Boron Nitride-Reinforced Polymer Composites Developed via 3D Printing Technology. Polymers 2023, 15, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovskiy, S.D.; Krotenko, I.A.; Stepashkin, A.A.; Zadorozhnyy, M.Y.; Kiselev, D.A.; Ilina, T.S.; Kolesnikov, E.A.; Senatov, F.S. Shape Memory Effect and Thermal Conductivity of PLA/h-BN Composites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 7170–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, E.; Keyinci, S.; Yakaryılmaz, A.C.; Özcanlı, M.; Yıldızhan, Ş.; Yüksek, H. Effects of Fan Placements on Thermal Characteristics of an Air-Cooled Lithium-Ion Battery Module. Sci. Iran 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Cai, C.; Guo, J.; Qian, Z.; Zhao, N.; Xu, J. Fabrication of Oriented HBN Scaffolds for Thermal Interface Materials. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 16489–16494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; An, L.; Yu, L.; Pan, Y.; Fan, H.; Qin, L. Strategies for Optimizing Interfacial Thermal Resistance of Thermally Conductive Hexagonal Boron Nitride/Polymer Composites: A Review. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 10587–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Song, W.; Ning, G.; Sun, X.; Sun, Z.; Xu, G.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Tao, S. 3D–Printing of Materials with Anisotropic Heat Distribution Using Conductive Polylactic Acid Composites. Mater. Des. 2017, 126, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, H.; Liyun, W.; Wang, N.; Xu, T.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, H.; He, Q.; Zhang, K.; et al. Fabrication of Thermally Conductive Polymer Composites Based on Hexagonal Boron Nitride: Recent Progresses and Prospects. Nano Express 2021, 2, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, H.; Niu, H.; Ren, Y.; Fang, H.; Fang, X.; Lv, R.; Maqbool, M.; Bai, S. Highly Thermally Conductive 3D Printed Graphene Filled Polymer Composites for Scalable Thermal Management Applications. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6917–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.A.; Verma, S.; Bhattacharyya, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Nanoparticle Assisted PCM-Based Battery Thermal Management System. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 11223–11237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, R.; Hosen, M.S.; He, J.; AL-Saadi, M.; Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, M. Novel Design Optimization for Passive Cooling PCM Assisted Battery Thermal Management System in Electric Vehicles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 32, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).