Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the effect of hydrothermal treatment (different steaming process) conditions, specifically temperature, pressure, and steaming time on selected physical properties of beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.), such as moisture content, density, colour, and longitudinal contraction. The research was conducted using two steaming modes: pressure steaming process (108 °C, 181 kPa, 7 h) and atmospheric steaming process (80 °C, 101 kPa, 15 h). The results showed that pressure steaming caused a more significant decrease in moisture content (by 16.9%) compared to atmospheric steaming (by 8.0%) and a smaller variation in values, which is favourable for subsequent drying. The differences in density after steaming were not statistically significant. On the contrary, longitudinal shortening was significantly greater with pressure steaming, which may indicate the release of tension reaction wood. The colour change was similar in both modes; lightness (L*) decreased and the wood acquired a redder hue without a significant effect of steaming conditions on the overall colour differentiation (ΔE). The results confirm that steaming temperature and pressure have a significant effect on the moisture change and longitudinal contraction of beech wood, while density and colour change remain relatively stable. The length of the steaming process has a major effect on the colour change of the wood.

1. Introduction

Hydrothermal treatment of wood is the combined action of heat and steam on wood, which can cause changes in its physical, mechanical, and chemical properties. Depending on the technology that follows this process, these changes can be used [1,2]. Changes in wood properties can be reversible or irreversible. The character of reversible changes means that a physical process must be involved, because any change in the main components of the lignin–saccharide matrix of wood is always irreversible [1,2]. Permanent irreversible changes in wood properties are characterized by the fact that after hydrothermal treatment and cooling, the wood exhibits altered chemical, physical, and mechanical properties. Numerically, irreversible changes are expressed as the difference between the properties of wood before and after hydrothermal treatment. Irreversible changes are used in further processing, such as permanent change in wood color, detection and elimination of internal stresses in wood, and so forth [1,2]. Also, another study says that hydrothermal treatment significantly improves the dimensional stability of beech wood under optimal conditions and reduces its susceptibility to swelling and water absorption [2]. Although hydrothermal treatment of wood by steaming process has been used for decades, the effects of the basic treatment conditions on the physical, mechanical, and chemical properties of wood have not been sufficiently explained. The actual mechanism of these changes as a result of hydrothermal action has been little studied [1].

European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) often develops tension wood as part of its natural adaptive response to mechanical stresses such as stem inclination, asymmetric crown formation, or other growth irregularities. This physiological mechanism enables beech trees to maintain or regain vertical stability by generating internal stresses on the upper sides of leaning stems and branches [3,4]. In beech, the presence of tension wood is relatively common, typically occurring in 14% to more than 20% of the wood volume, and represents a characteristic feature that strongly influences its technological properties and processing behaviour [5,6]. Studies have shown that beech wood containing tension wood exhibits markedly higher longitudinal contraction after high-temperature drying (up to 100 °C), particularly when subjected to contact drying under pressure [2]. These findings suggest that the distinctive anatomical and chemical structure of beech tension wood plays a crucial role in its dimensional stability, regardless of growth ring orientation. Consequently, processing challenges such as twist, bow, or cup observed in kiln-dried beech lumber are often attributed to the heterogeneous distribution of this reaction tissue within the wood. Based on the cited work [6,7], hydrothermal modification of European beech significantly affects its thermal and structural characteristics. Treatment at 180 °C caused an increase in thermal conductivity in the tangential and especially the longitudinal directions, while the radial direction decreased, which is related to changes in the cellulose ultrastructure and degradation of parenchyma cells. At the higher temperature of 220 °C, more pronounced decomposition of the wood structure occurs, leading to a decrease in density and thermal properties. The results indicate that accurate knowledge of the thermal properties of hydrothermally modified wood is essential for reliable modelling of heat transfer in construction applications.

According to these studies [8,9] on densified wood, they found that although density and mechanical properties improve, dimensional stability remains a challenge when a high proportion of tension wood is present. To address the detection of wood in an industrial context, publication [10] developed a practical chemical reagent that visibly differentiates tension wood from normal wood. This method allows for rapid identification before or during processing and can be used as a preventive measure to mitigate production losses caused by warping and deformation. The action of water and heat during the steaming process called hydrothermal treatment of wood causes a loss of mass in beech wood. This is due to the hydrolysis of hemicelluloses, the extraction of low-molecular-weight fragments of lignin, and, to a lesser extent, the degradation of the amorphous portion of cellulose. Chemical analyses of the condensate produced during the steaming of beech wood indicate a high content of acetic acid and, in smaller amounts, formic, vanillic, syringic, and propionic acids. Among the monomeric sugars present in the condensate are D-mannose, D-glucose, L-arabinose, and L-rhamnose, while compounds derived from the benzoid portion of the wood mainly include those containing the fundamental structural components of lignin-guaiacyl and syringyl structural units. In condensates formed during pressure steaming of beech wood at temperatures above 120 °C, D-xylose and 2-furaldehyde are also found [11].

The decrease in mass and change in density of steamed beech wood depend on the conditions and duration of steaming process as well. During atmospheric steaming at temperatures up to 100 °C, a lower mass loss is achieved. For beech wood, this loss can reach 5–7%, and a 14% weight reduction was reported after steaming at 160 °C for two hours [12]. Research [13], for example, reported a density reduction of up to 2% for beech (Fagus orientalis L.) after steaming at 80 °C for 100 h. A greater loss of mass, accompanied by more significant chemical changes, occurs during pressure steaming at temperatures above 120 °C. During the steaming process, both the moisture content of the wood and its distribution across the cross-section change. This moisture level depends on the wood’s initial moisture content before the steaming process as well as on the steaming conditions. Wet beech lumber with an initial moisture content above 60% shows, after 72 h of steaming, an average decrease in moisture content of about 8–12% [12,13].

The reduction in moisture during steaming is also related to external conditions such as the degree of steam saturation, duration, and temperature of steaming. Conversely, when over-dried wood is steamed, it swells and its moisture content increases [12]. This reduction in moisture content results from drying processes that occur in wood even in a saturated atmosphere when it is exposed to atmospheric steaming temperatures [14]. According to research [15], the reduction in moisture content in wood occurs in three stages: (1) when the temperature rises during the heating phase, (2) when the wood reaches the boiling point of water due to the expansion of air bubbles, and (3) during the cooling phase at atmospheric temperature. Based on the cited work, [16] reported that, when Eucalyptus dunnii wood was steamed before drying (t = 100 °C, φ = 100%, τ = 3 h), the initial moisture content of the steamed lumber decreased by 9.2% compared with that of unsteamed lumber. These findings are consistent with those of [17], who concluded that pre-steaming eucalyptus wood before drying caused a reduction in its initial moisture content by 5–20%, depending on the wood species [13]. Research [11] also reported that, during pressure steaming at 135 °C, the moisture content of lumber decreases by 15–20%.

To some extent, the observed changes in ultrastructure and anisotropy can be compared to the properties of reaction wood, where natural adaptation of the cells alters the orientation of cellulose and the physical properties of wood. In this way, hydrothermal modification can be regarded as a controlled method of influencing wood properties, similar to the mechanical adaptation in reaction wood, providing valuable insights for optimizing materials in construction and engineering [6]. Given these findings, it is evident that the presence of tension wood in beech substantially increases the complexity of drying, steaming, and subsequent mechanical processing. The distinctive anatomical structure, hygroscopic behaviour, and anisotropic shrinkage of tension wood necessitate careful consideration in both scientific investigation and industrial application in order to ensure dimensional stability, optimize processing parameters, and maintain consistent quality of beech wood products [17]. This study investigates the effects of temperature, pressure, and duration of hydrothermal treatment (steaming) on the moisture content, density, colour, and longitudinal contraction of beech wood. Two common steaming methods, pressure and atmospheric, were compared, highlighting their differing conditions. The results provide a detailed analysis of how individual steaming parameters influence the physical properties of beech wood, with implications for achieving desired colour changes.

2. Materials and Methods

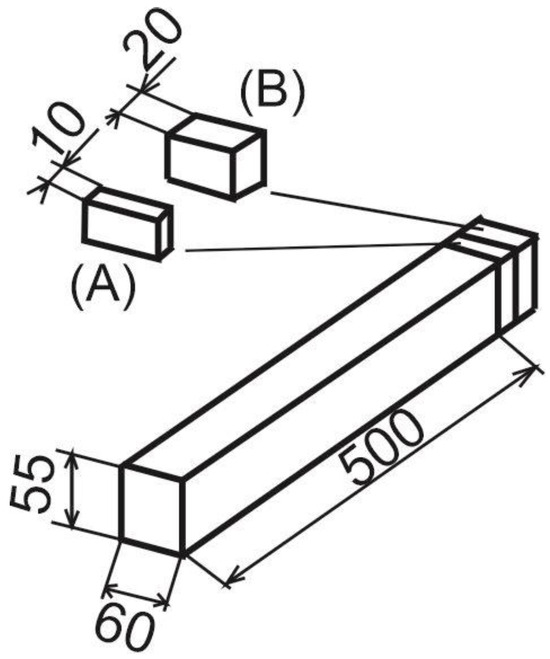

The material selected for research was European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). This is the most common tree species in Slovak forests and is used for the production of solid glued boards. The material for the investigation was obtained from the Forests of the Slovak Republic area (Poľana, Považie, Tribeč). The samples were 55 mm thick, 60 mm wide, and 500 mm long. The dimensions correspond to the most commonly used dimensions of planks for the production of glued boards. The samples were produced from beech raw wood of quality class III.B (according to STN 48 00 56). The sawmill logs were sawn using a vertical bandsaw-type EWD 1800 with a milling head EWD PF 19 (Esterer WD GmbH, Altötting, Germany) to produce 60 mm thick boards. These were then sawn into long blanks 2000 mm) with a thickness of 55 mm, with a total quantity of 26 pieces. Samples 500 mm long were taken from the long pieces so that they did not contain any visible defects such as cracks, red false heartwood, rot, or knots. Samples were taken from each sample to also determine the absolute moisture content and density of the wood (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Samples for determining (A) moisture content and (B) wood density in an absolute-dry state.

The samples were steamed in industrial steaming equipment at selected companies in Slovakia. Two steaming techniques were used: pressure steaming and atmospheric steaming. Pressure steaming took place in an autoclave Ø 2.3 × 28 m (VYVOS company Ltd., Uherský Brod, Czech Republic) at a pressure of p = 181 kPa. The total steaming time was 7 h and the maximum temperature was 108 °C. The steaming mode is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Process conditions and parameters for pressure and atmospheric steaming of wood.

Atmospheric steaming was performed in a steaming chamber (Suzar company Ltd., Považany, Slovakia) with indirect steaming (steam was produced in the steaming device). The pressure in the steaming chamber was p 131.32 kPa (atmospheric), the total steaming time was 15 h, and the maximum temperature was 80 °C (Table 1).

2.1. Moisture Content and Density of Wood

Before and after the steaming process, the absolute moisture content of each sample was measured using a gravimetric method in accordance with STN 49 0103 [18]. The moisture content of the wood was calculated using the following Equation (1):

where mw is the weight of the moisture sample (g) and m0 is the weight of the oven-dry sample (g).

The density and absolute-dry state (ρ0) densities were determined (STN EN 49 0108) [19] for every sample. The measurement was performed under laboratory conditions. The density and absolute-dry state were calculated using Equation (2).

where m0 is the weight of the oven-dried moisture samples (kg) and V0 is the volume of the oven-dried moisture samples (m−3).

2.2. Longitudinal Contraction

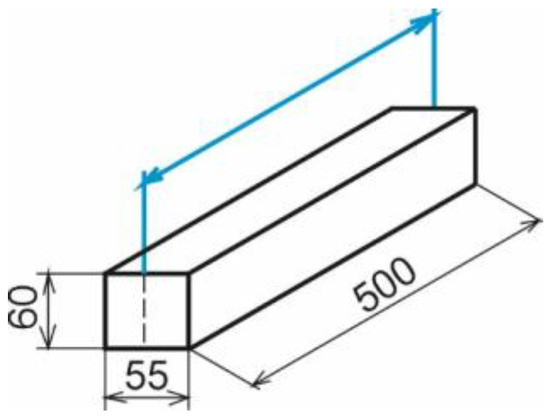

The effect of the steaming method on the size of longitudinal contraction is an interesting indicator, as it is possible to predict the subsequent longitudinal shrinkage of the samples during drying. To calculate longitudinal contraction, it is necessary to measure the length of the samples before and after the steaming process [20]. The measurement was performed with a sliding calliper, always at the same place on the cross-section of the samples (Figure 2). An INSIZE sliding calliper was used for measurement, which allows measuring lengths in the range of 0–500 mm with an accuracy of ± 0.05 mm. Measurements were taken on 30 samples for each steaming method compared. On each sample, the measurement was taken three times in a row at the same location and the arithmetic mean was calculated. This value was used as the measured dimension for the given sample.

Figure 2.

Measurement of longitudinal contraction (blue line) of samples.

The value of longitudinal shortening (contraction) was calculated according to Equation 3 based on the quoted work [20].

where lbefore: length of sample before drying process, lafter: length of sample after different lengths of steaming process.

2.3. Colour Changes of Wood

The colorimetric parameters were measured on the surface of the samples before and after the steaming process using the CIE Lab system.

The coordinates L* (lightness or black–white ratio), a* (red–green coordinate), and b* (yellow–blue coordinate) were used to determine the overall colour change.

The colour space coordinates were measured using a CR-10 Color Reader colorimeter (Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Sakura, Japan). The colour was measured at one point on each sample, always at the same position marked on the sample. The colour difference was calculated from the measured data before and after steaming according to the following Equation (4):

where L1, a1, b1 are the values of the coordinates of the colour space of the wood before the drying process and L2, a2, b2 are the values of the coordinates of the colour space after the drying process.

The parameters L*, a*, and b* are coordinates of the colorimetric space [21]. The colour change criteria are defined below:

∆E < 0.2 Invisible colour change

2 > ∆E > 0.2 Slight change of colour

3 > ∆E > 2 Colour change visible in high filter

6 > ∆E > 3 Colour change visible with the average quality of the filter

12 > ∆E > 6 High colour change

∆E > 12 Different colour

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wood Moisture

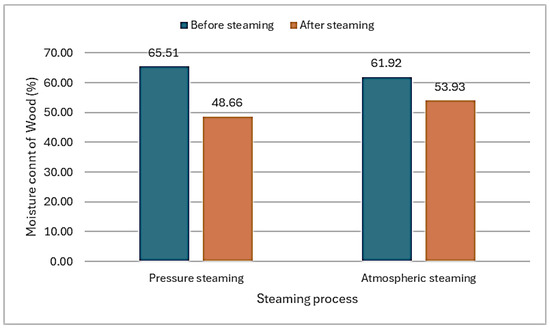

Moisture measurements of samples before and after the steaming processes were performed on 26 samples using the gravimetric method. The basic statistical characteristics of the change in moisture content of the samples during pressure and atmospheric steaming of beech wood are shown in Table 2 and a graphical representation of the average moisture content is shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Basic statistical characteristics of the initial and final moisture content of samples before and after pressure and atmospheric steaming.

Figure 3.

Average moisture values of samples before and after steaming processes.

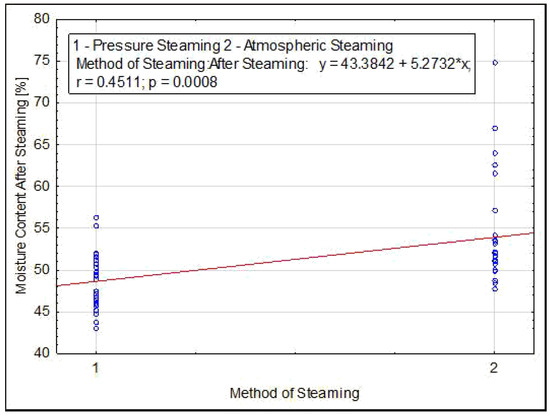

Due to the effects of pressure steaming, the decrease in moisture content of the samples was greater than the decrease after atmospheric steaming. The average decrease in moisture content was 16.86% for pressure steaming and 7.99% for atmospheric steaming. This indicates that the effect of temperature during steaming has a greater impact on the decrease in moisture content than the steaming time. In pressure steaming, the steaming temperature is higher than 100 °C (on average 108 °C), which, in combination with higher pressure, causes faster and more intense penetration of steam into the wood cells than in atmospheric steaming. Due to the higher steaming temperature, the water in the wood is transformed into steam more quickly and its transport in the wood structure from the centre to the evaporation zone is faster than at a lower temperature (atmospheric steaming). At a steaming temperature of 80 °C (atmospheric steaming), heat transfer from the surface to the centre of the samples is slower, and the change of state of the water in the wood from solid to gas is also slower. This causes a smaller measured decrease in the average moisture content of the samples after steaming at a lower temperature. After pressure steaming, the variance of the measured moisture values of the samples was smaller than in atmospheric steaming (Figure 4). A smaller variance in moisture is positive for the subsequent drying process. Statistical evaluation of the final moisture content during pressure and atmospheric steaming revealed a statistically significant difference between these two steaming methods (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the final moisture content of beech samples after steaming for pressure (1) and atmospheric steaming (2).

Similar results are reported in the work of [17,22], who report a 22% decrease in moisture content when pressure steaming beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.). Our observations are consistent with the authors [15] which reported that, when Eucalyptus dunia wood was steamed before drying (t = 100 °C, φ = 100%, τ = 3 h), the initial moisture content of the steamed lumber decreased by 9.2% compared with that of unsteamed timbers.

This reduction in moisture content results from drying processes that occur in wood even in a saturated atmosphere when it is exposed to atmospheric steaming temperatures [17].

3.2. Wood Density

The density of wood affects its basic properties (strength, modulus of elasticity, specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, etc.) and some properties determining the mechanism of internal water movement, such as the coefficient of moisture conductivity. Changing the density will change the dimensions and distribution of the spaces filled with water. It is important to identify the influence of steaming parameters on the change in density and thus the possible change in other wood properties [12,23].

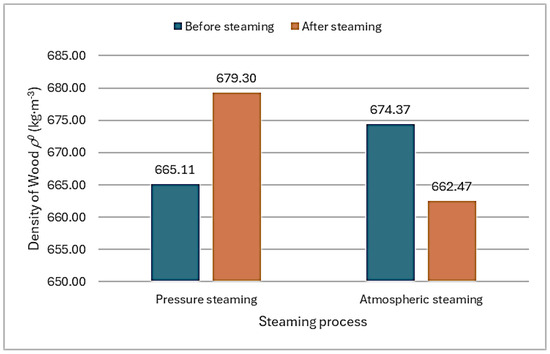

The basic statistical characteristics of the density of samples in an absolute-dry state during pressure and atmospheric steaming of beech wood are shown in Table 3, and a graphical representation of average moisture content is shown in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Basic statistical characteristics of density in an absolutely dry state before and after pressure and atmospheric steaming.

Figure 5.

Average values of wood density in an absolute-dry state before and after steaming processes.

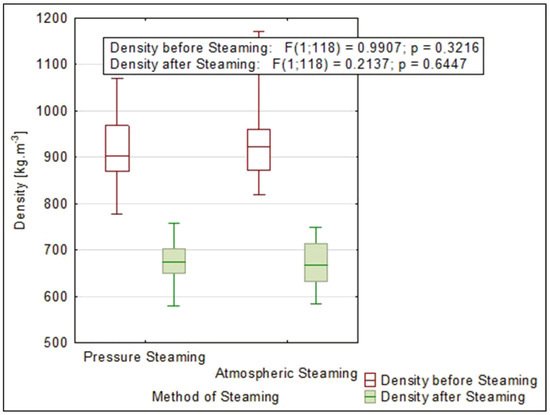

As also shown by [7], the decrease in mass and change in density of steamed beech wood also depend on the conditions and duration of steaming process. During atmospheric steaming at temperatures up to 100 °C, a lower mass loss is achieved. As also shown in research [12], for example, a density reduction of up to 2% for Fagus orientalis L. was reported after steaming at 80 °C for 100 h. A greater loss of mass, accompanied by more significant chemical changes, occurs during pressure steaming at temperatures above 120 °C. For beech wood, this loss can reach 5–7% [11]. After pressure steaming, the average increase in sample density was 14.19 kg·m−3. After atmospheric steaming, the density of the samples decreased by 11.9 kg·m−3. In a statistical comparison of the significance of the differences in mean values between the steaming methods, statistically insignificant differences were measured between the change in density before and after steaming (Figure 6). The method and conditions of steaming thus had no effect on the change in density of the samples.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of beech sample density before and after steaming for pressure and atmospheric steaming.

When beech wood is steamed above 100 °C, the steamed wood shows a significant decrease in weight [22]. This is caused not only by the high temperature itself, but also by the plasticization material, which acquires an acidic character, increasing its degradative character. The weight loss increases with increasing temperature and time [23]. At higher temperatures and pressure steaming, there should be a greater decrease in density, which is caused by greater chemical changes in the lignin–saccharide matrix. This was not confirmed in our measurements. The effect of steaming temperature on the density change in the samples was less significant than the steaming time. In atmospheric steaming, the steaming time was more than 100% longer than in pressure steaming [24].

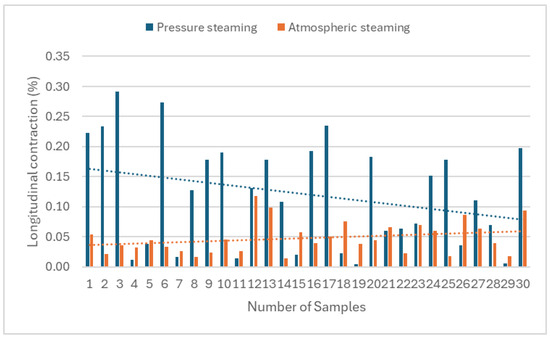

3.3. Longitudinal Contraction

The longitudinal contraction values of the samples were calculated according to Equation 3, with the length of the samples after steaming being measured 24 h after removal from the steaming device. Measurements were taken on 30 samples for each steaming method (Figure 7). The basic statistical characteristics for the individual steaming methods are shown in Table 4, and a graphical representation of the unmeasured sample values and trend lines is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Values of longitudinal contraction of beech samples during pressure and atmospheric steaming.

Table 4.

Basic statistical characteristics of longitudinal contraction for steaming methods.

From the calculated values, it can be concluded that higher steaming temperatures and increased pressure (pressure steaming) cause greater longitudinal contraction of beech samples than atmospheric steaming. When steaming at a maximum temperature of 80 °C and atmospheric pressure, the longitudinal contraction is nearly half as large.

Higher values of longitudinal contraction during pressure steaming can have a positive effect on the release or detection of tension reaction wood. This growth defect occurs frequently in beech wood. Statistical analysis confirmed a significant difference between the compared steaming methods in terms of the amount of longitudinal contraction. Our results are consistent with authors [24,25], who report that at temperatures above 100 °C, significant plasticization of the lignin–saccharide matrix occurs. This subsequently weakens the bonds between S2 and the G layer, which in turn leads to the release of growth stresses.

Based on the cited work [26,27], mechanical loading has an effect on the deformation of spruce lumber during industrial kiln drying. The experiments were conducted on lumber from Picea abies and Picea sitchensis with log diameters of 150–170 mm, where a high proportion of juvenile wood increased susceptibility to deformations, particularly twisting and longitudinal warping. The results showed that applying mechanical loading to the lumber stacks significantly reduced the extent of deformation. For sections measuring 50 × 100 mm, an applied load of approximately 600 kg/m2 was found to be optimal, keeping the lumber straight throughout the drying process. Higher loads did not yield further improvement. These findings clearly demonstrate that mechanical loading can be an effective tool for minimizing warping, while also highlighting the importance of controlling both the type and magnitude of the applied load during lumber processing. Atmospheric steaming at a maximum temperature of 80 °C resulted in only a limited release of growth stresses and thus less contraction. These authors report the amount of contraction after two hours of steaming to be in the range of 0.2% at a temperature of 80 °C and 0.6% at a temperature of 100 °C. The cited work [23] measured a maximum contraction of 0.3% for chestnut reaction wood at a temperature of 80 °C and one hour of hydrothermal treatment (steaming process). In our measurements, contraction due to pressure steaming was measured to be more than 1% in some cases when the blank was shortened by 5.1 mm from the original length of 503.09 mm to 497.49 mm. The maximum measured value for atmospheric steaming was 0.46%.

These findings suggest that longitudinal deformations can be partially reduced not only by steaming, but also by applying appropriately selected mechanical loads. Furthermore, the type of steaming used has a significant impact on the results, as different steaming methods can affect the degree of deformation reduction achieved.

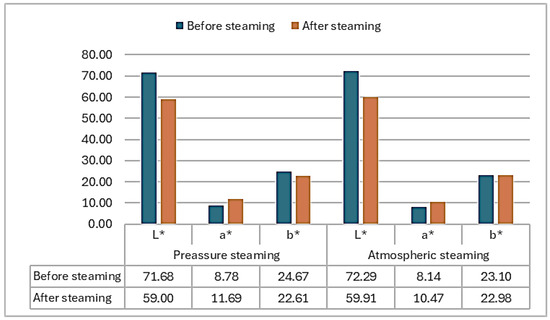

3.4. Colour Changes

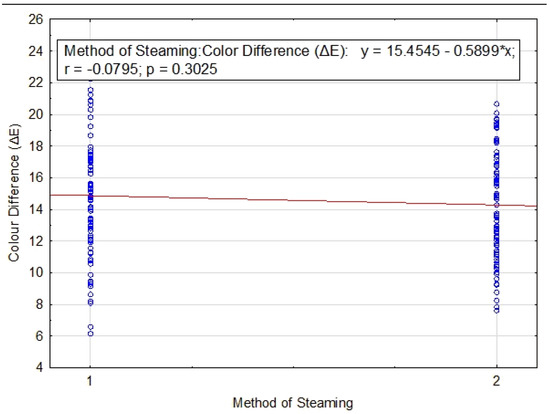

The average values of coordinates L*, a*, and b* before and after pressure and atmospheric steaming are shown in Figure 8. A statistical comparison of the calculated values of colour differences ΔE after the compared steaming methods is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Average values of coordinates L*, a*, and b* before and after pressure and atmospheric steaming.

The steaming process reduced the lightness value (L*), increased the a* coordinate value, and left the b* coordinate value almost unchanged compared to the original value before steaming. In terms of changes in individual colour coordinates, it was observed that the average value of the L* coordinate decreased to approximately the same extent in both pressure and atmospheric steaming. The a* coordinate behaved similarly, with its value increasing in both cases. The only significant difference was observed in the b* coordinate, which decreased more in pressure-steamed cuts. The changes in the individual colour coordinates are in agreement with [17]. We can conclude that steaming reduced the lightness and gave the beech wood a redder shade and, on the contrary, made it less yellow. No statistically significant influence of steaming conditions (temperature, time, and pressure) on the change in colour space coordinates or on the size of the colour difference ΔE was confirmed (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of ΔE for the compared steaming methods (1) Pressure steaming, (2) Atmospheric steaming for beech wood samples. The red line shows that there is no meaningful relationship between the steaming method and the color difference ΔE.

Achieving a consistent colour tone across the entire cross-section of the samples is one of the aims of the steaming process. The intensity of colour difference is affected by three factors: moisture, temperature, and time. Greater colour changes are achieved with higher initial wood moisture content. References [24,25] state that the moisture content required for an intense and consistent colour change is 50–60%. In our case, the moisture content of the incoming planks were always higher than 50%. According to the results reported in study [28] pressure steaming at temperatures of 110–115 °C resulted in an increase in the L* coordinate by approximately 3%, a pronounced rise in the a* value by 41%, and a slight increase in the b* parameter. Consequently, the surface of the steamed wood exhibited a more pronounced pinkish hue. The overall color difference ΔE was classified as “a color change perceptible through a medium-quality filter.” These findings are consistent with the understanding that steam-induced chemical transformations intensify with increasing temperature and elevated steam pressure.

Approximately the same colour of samples was achieved by both pressure and atmospheric steaming. In pressure steaming, this was achieved by a combination of increased temperature (108 °C) for 7 h, and in atmospheric steaming, at a temperature of 80 °C for 15 h. The average colour difference value was 14.86 for pressure steaming and 14.28 for atmospheric steaming. According to the evaluation criteria for colour difference ΔE changes listed in the Material and Methods chapter, this change is categorized as the highest degree of “different colours.”

4. Conclusions

This article compares two methods of hydrothermal treatment of beech wood, pressure and atmospheric steaming, which are different in terms of conditions and also steaming time. Based on the measured and calculated data, the following conclusions can be made:

- The steaming temperature has a significant effect on the decrease in wood moisture content and on the moisture content variation in the samples.

- The effect of steaming conditions and method on the change in sample density was not statistically significant.

- The steaming temperature has a significant effect on longitudinal contraction. Higher values of longitudinal contraction during pressure steaming may have a positive effect on the release or detection of tension reaction wood.

- There were no statistically significant effects of steaming conditions (temperature, time, and pressure) on the change in colour space coordinates or on the size of the colour difference ΔE. Approximately the same colour change was achieved with both steaming methods.

Pressure steaming is a more technically and technologically difficult method, but the identified and statistically confirmed changes in selected physical properties of beech wood are positive for its further processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and P.V.; methodology, T.V., M.U. and I.K.; software, P.V. and I.K.; validation, P.V. and I.K.; formal analysis, P.V.; investigation, M.U. and P.V.; resources, T.V.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K. and P.V.; writing—review and editing, T.V.; visualization, T.V.; supervision, I.K.; project administration, P.V. and T.V.; funding acquisition, P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. APVV-21-0049. This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences project VEGA no. 1/0063/22.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. APVV-21-0049. This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences—project VEGA no. 1/0063/22.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Trebula, P.; Klement, I. Sušenie a Hydrotermická Úprava Dreva (Drying and Hydrothermal Treatment of Wood); Technical University in Zvolen: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2002; pp. 152–449. ISBN 80228142. [Google Scholar]

- Rezayati, C.P.; Mohammadi, R.J.; Mohebi, B.; Ramezani, O. Influence of Hydrothermal Treatment on the Dimensional Stability of Beech Wood. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. (CJES) 2007, 5, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kúdela, J.; Čunderlík, I. Bukové Drevo—Štruktúra, Vlastnosti, Použitie (Beech Wood—Structure, Properties, and Applications), 1st ed.; Technical University in Zvolen: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2012; p. 152. ISBN 978-80-228-2318-0. [Google Scholar]

- Majka, J.; Sydor, M.; Prentki, J.; Zborowska, M. Initial Desorption of Reaction Beech Wood. Drv. Ind. 2022, 73, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, S.; Toratti, T.; Kanerva, P. Modelling longitudinal elastic an shrinkage properties of wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 1989, 23, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, Ł.; Olek, W.; Weres, J. Effects of heat treatment on thermal properties of European beech wood. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelle, J.; Yoshida, M.; Clair, B.; Thibaut, B. Peculiar tension wood structure in Laetia procera (Poepp.) Eichl. (Flacourtiaceae). Trees 2007, 21, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thybring, E.E.; Kymäläinen, M.; Rautkari, L. Moisture in modified wood and its relevance for fungal decay. Forest 2018, 11, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kúdela, J.; Rešetka, M. Influence of pressing parameters on dimensional stability and selected properties of beech wood II. Density profile and hardness. Acta Fac. Xylologiae 2013, 55, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Vilkovská, T.; Klement, I.; Vilkovský, P.; Čunderlík, I.; Geffert, A. Chemical reagent for detecting tension wood in selected tree species. BioResources 2024, 19, 4335–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, B.; Barnett, J.; Saranpää, P.; Gril, J. The Biology of Reaction Wood, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; p. 274. ISBN 978-3-642-10813-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Gezer, E.D.; Dizman, E.; Temiz, A. The effects of Heat Treatment on Anatomical changes of beech wood; IRG/WP02- 40223. In Proceedings of the IRG Annual Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 6–10 June, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Severo, E.T.D.; Tomaselli, I.; Calonego, F.W.; Ferreira, A.L.; Mendes, L.M. Effect of steam thermal treatment on the drying process of Eucalyptus dunnii variables. Cerne 2013, 19, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.T. Effect of presteaming on moisture gradient of Northern Red Oak during drying. Wood Sci. 1976, 8, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Jourez, B.; Riboux, A.; Leclercq, A. Anatomical Characteristics of Tension Wood and Opposite Wood in Young Inclined Stems of Poplar (Populus Euramericana Cv ‘Ghoy’). IAWA J. 2001, 22, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, H. A review of Eucalyptus wood collapse and its control during drying. BioResources 2018, 13, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deventer, H.C.; Heijmans, R.M.H. Drying with superheated steam. Dry. Technol. 2001, 19, 2033–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovak Standards STN 49 0103; Moisture Detection in Physical and Mechanical Tests/Zisťovanie Vlhkosti pri Fyzikálnych a Mechanických Skúškach. Slovak Institute of Technical Standardization: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1979.

- Slovak StandardsSTN 49 0108; Density Detection/in Slovak: Zisťovanie Hustoty. Slovak Institute of Technical Standardization: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1993.

- Čunderlík, I. The influence of reaction wood on the utilization of beech raw material. In Proceedings of the Current Status and Latest Trends in Biomass Utilization; Zvolen, Slovakia, 1992; pp. 76–83. Available online: https://www.library.sk/arl-sldk/sk/detail-sldk_un_epca-e000630-Vplyv-reakcneho-dreva-na-vyuzitie-bukovej-suroviny/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cividini, R.; Travan, L.; Allegretti, O. White beech: A tricky problem in the drying process. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Hardwood Processing, Québec City, QC, Canada, 24–26 September 2007; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, K.Y. A comparative study of the structure and chemical composition of tension wood and normal wood in beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.). For. Int. J. For. Res. 1947, 20, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Marques, A.V.; Domingos, I.; Pereira, H. Influence of steam heating on the properties of pine (Pinus pinaster) and eucalypt (Eucalyptus globulus) wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, B. Evidence that release of internal stress contributes to drying strains of wood. Holzforschung 2012, 66, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Varga, D.; Van der Zee, M.E. Influence of steaming on selected wood properties of four hardwood species. Holz Roh Werkst. 2008, 66, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvaj, L.; Papp, G.; Varga, D.; Lang, E. Effect of steaming on the colour change of softwoods. BioResources 2012, 7, 2799–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffert, A.; Výbohová, E.; Geffertová, J. Characterization of the changes of colour and some wood components on the surface of steamed beech wood. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2017, 59, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tronstad, S. (Ed.) Effect of Top Loading on the Deformation of Sawn Timber During Kiln Drying (EU Project STRAIGHT); Report 59; Norsk Treteknisk Institutt: Oslo, Norway, 2005; Available online: https://www.treteknisk.no/resources/6.-publikasjoner/3.-rapporter/Rapport-59.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).