Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Composition, Health-Promoting Properties, and Technological Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ecophysiological Characterization of Castanea sativa

2.1. Morphological and Anatomical Features

2.2. Ecophysiological Adaptation

2.3. Physiological Indicators

3. Nutrient and Chemical Profile of Chestnut Fruits

3.1. Main Nutrient Compounds

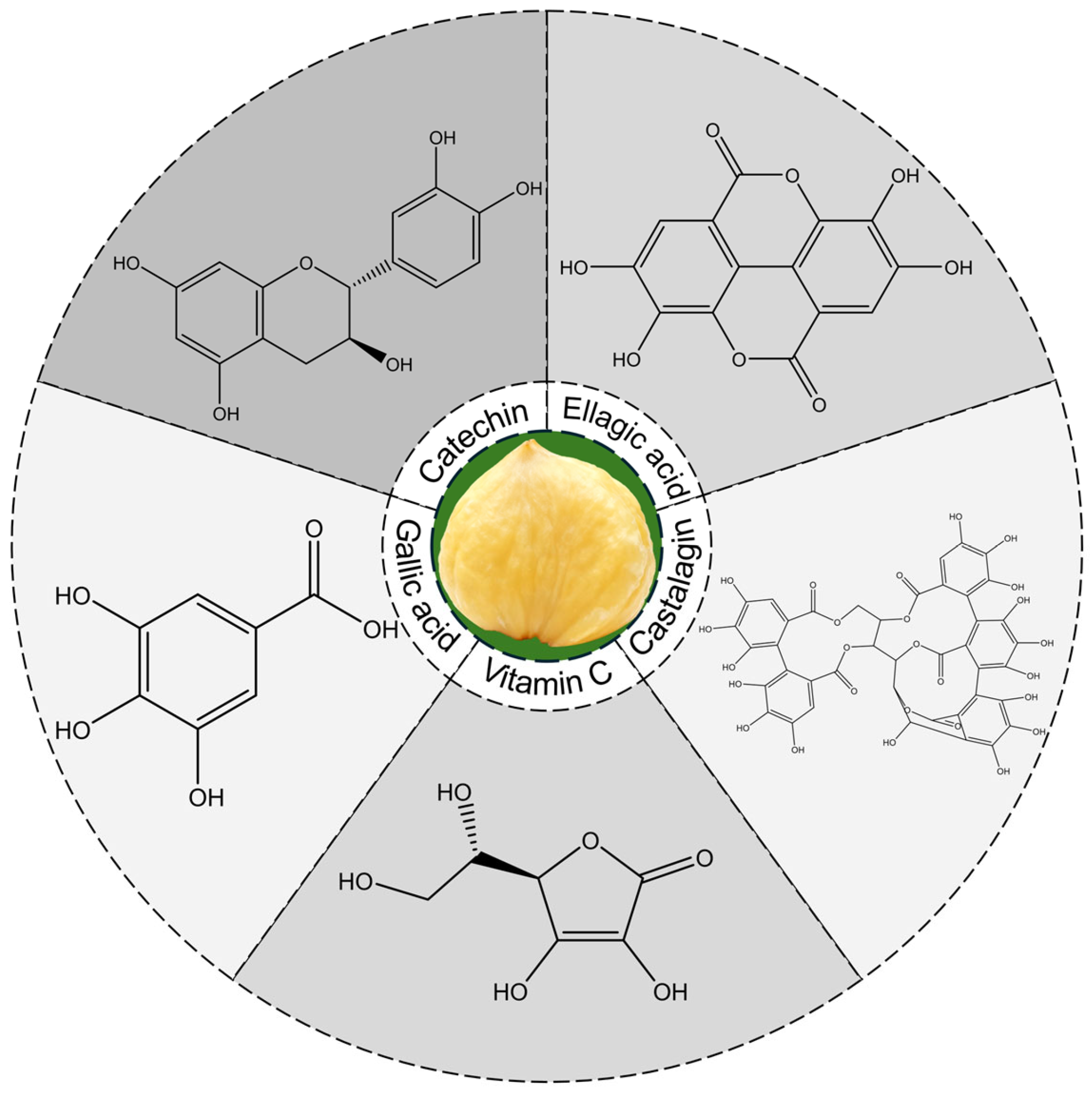

3.2. Main Phytochemicals

4. Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut By-Products

5. Extraction and Processing Techniques

6. In Vitro Assessment of Radical Scavenging Activity

Antioxidant Activity: In Vitro Radical Scavenging, Cellular Antioxidant Activity, and In Vivo Studies

| Sample | Extract Type | Radical Scavenging Assay | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burs | MeOH | DPPH: EC50 = 4.21 µg/mL; TEAC: 3.03 mg/mL; FRAP: 2.96 mmol ferric sulphate/g | [10] |

| Leaves | MeOH | DPPH: EC50 = 3.06 µg/mL; TEAC: 3.01 mg/mL; FRAP: 1.48 mmol ferric sulphate/g | |

| Fruit | MeOH | DPPH: EC50 = 34.64 µg/mL; TEAC: 0.57 mg/mL; FRAP: 0.18 mmol ferric sulphate/g | |

| Fruit pellicle | H2O | O2•− scavenging: ~40% inhibition at 172 µg/mL DPPH: ~50% inhibition at 172 µg/mL | [45] |

| EtOH | O2•− scavenging: ~40% inhibition at 172 µg/mL DPPH: ~50% inhibition at 172 µg/mL | ||

| Shells | Subcritical water extraction | HOCl: IC50 = 0.79 µg/mL; O2•−: IC50 = 12.92 µg/mL; ROO•: 0.32 µmol TE/mg DW; DPPH: 815.66 mg trolox eq./g DW; ABTS: 901.16 mg ascorbic acid eq./g DW; FRAP: 7994.26 mg ferrous sulphate eq./g DW | [46] |

| Shells | Ultrasound-Assisted (Water) Extraction | DPPH: IC50 = 44.10 µg/mL; ABTS: IC50 = 65.40 µg/mL; FRAP: IC50 = 32.00 µg/mL; HOCl: IC50 = 0.70 µg/mL; O2•−: IC50 = 14.10 µg/mL; ROO•: 0.30 µmol TE/mg DW; •NO: IC50 = 0.10 µg/mL | [50] |

| Shells | EtOH: Water (70:30; v/v) | FRAP: between 4.56 and 7.04 mmol ascorbic acid eq./mg extract | [49] |

| Fruit peels | Subcritical water extraction | DPPH: 5.43 mmol trolox eq./g extract; Cu2+ chelating activity: 85.07 mmol EDTA eq./g extract | [47] |

7. Assessment of Chestnut Fruit By-Products as Waste Bioactivities Using Cell-Based Assays and In Vivo Studies

7.1. Antioxidant Activity

| Sample | Extract Type | Experimental Model | Concentration | Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burs | MeOH | THP-1-XBlue-MD2-CD14 cells | 5 µg/mL | Reduced pyocyanin-induced ROS | [10] |

| Leaves | MeOH | ||||

| Fruit | MeOH | ||||

| Burs | EtOH: Water (50:50; v/v) | Wistar rats (Streptozotocin-induced diabetes) | 60 mg/kg | Reduced ROS and lipid peroxidation Increased MnSOD and CuZnSOD activity Increased GSH/GSSG ratio | [53] |

| Bark | Not specified | TK6 cells | 12 µg/mL | Reduced H2O2-induced ROS; Reduced mitomycin C-induced ROS | [52] |

| Peels | Subcritical water extraction | 3T3-L1 cells | 75 µg/mL | Reduced ROS levels | [47] |

| Shells | Subcritical water extraction | Wistar rats | 100 mg/kg | Increased SOD and GSH-Px activity in the liver, kidney, and serum | [54] |

| Wood distillate | Commercial extract; Pyrolysis | HaCaT cells | 0.07% (v/v) | Reduced H2O2-induced ROS | [55] |

| A431 cells | |||||

| NHDF cells | |||||

| HUVEC cells | |||||

| Burs | Aqueous | RAW 264.7 cells | 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL | Reduced LPS-induced ROS | [56] |

7.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

| Sample | Extract Type | Experimental Model | Concentration | Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burs | MeOH | THP-1-XBlue-MD2-CD14 cells | 5 µg/mL | Reduced LPS-induced NF-kB activation | [10] |

| Leaves | |||||

| Fruit | |||||

| Burs | MeOH | J774.A1 cells | 5 µg/mL | Reduced LPS-induced NO production | [10] |

| Leaves | |||||

| Fruit | |||||

| Burs | MeOH-d4/H2O-d2 (50:50; v/v) | BV-2 cells | 0.5 mg/mL | Reduced LPS-induced inflammation Decreased IL-1β and TNF-α expression Decreased NF-kB protein levels | [57] |

| Leaves | |||||

| Wood distillate | Commercial extract; Pyrolysis | HUVEC cells | 0.07% (v/v) | Reduced IL-1β/TNF-α-induced inflammation Reduced COX-2, mPGES-1, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 levels | [55] |

| Buds | EtOH: Water (50:50; v/v) | Caco-2 cells | 50 µg/mL | Reduced IL-1β/IFN-γ-induced inflammation Reduced CXCL-10, IL-8, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 levels Reduced NF-kB-driven transcription | [11] |

| Wood | |||||

| Pericarp | |||||

| Episperm | |||||

| Burs | Aqueous | RAW 264.7 cells | 100 µg/mL | Reduced LPS-induced nitric oxide production Reduced NF-kB activation Reduced iNOS protein level | [56] |

7.3. Anti-Tumoral Activity

7.4. Cardioprotective Activity and Effect on Metabolic Indicators

8. Technological and Industrial Applications of Chestnut Fruits, By-Products, and Waste Products

8.1. Chestnuts in Food Products and Functional Foods

8.2. Cosmetic and Pharmaceuticals, Key Bioactive Compounds and Mechanisms

8.3. Active Packaging and Biopolymers

8.4. Sustainable Extraction, Innovation, and Technology Transfer

9. Future Perspectives and Challenges

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| •NO | Nitric oxide radical |

| AGE | Advanced glycation end-product |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| Car | Carotenoids |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

| Chla | Chlorophyll A |

| Chlb | Chlorophyll B |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CuZnSOD | Copper–zinc superoxide dismutase |

| CXCL-10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| EIT | European Institute of Innovation and Technology |

| Eq. | Equivalents |

| EtOH | Ethanol |

| FRAP | Ferric-reducing antioxidant power |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HOCl | Hypochlorous acid |

| IBMX | 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAC-EtOH | Maceration with ethanol |

| MAE-EtOH | Microwave-assisted extraction with EtOH |

| MAE-w | Microwave-assisted extraction with water |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| MnSOD | Manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase |

| mPGES-1 | Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| O2•− | Superoxide radical |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| PPFD | Photosynthetic photon flux density |

| PUAE | Pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RAGE | Receptor for advanced glycation end-products |

| ROO• | Peroxyl radical |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SEAP | Secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase |

| TEAC | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UAE-EtOH | Ultrasound-assisted extraction with ethanol |

| UAE-MeOH | Ultrasound-assisted extraction with methanol |

| UV | Ultraviolet radiation |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

References

- Squillaci, G.; Apone, F.; Sena, L.M.; Carola, A.; Tito, A.; Bimonte, M.; Lucia, A.D.; Colucci, G.; Cara, F.L.; Morana, A. Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) industrial wastes as a valued bioresource for the production of active ingredients. Process Biochem. 2018, 64, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglietti, C.; Cappelli, A.; Andreani, A. From Chestnut Tree (Castanea sativa) to Flour and Foods: A Systematic Review of the Main Criticalities and Control Strategies towards the Relaunch of Chestnut Production Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.; Pinto, T.; Mota, J.; Correia, E.; Vilela, A. Influence of the cooking system, chemical composition, and α-amylase activity on the sensory profile of chestnut cultivars-longal and judia-and their consequence on consumer’s acceptability. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăghici, L.-R.; Hădărugă, D.I.; Bădoiu, B.; Mitroi, C.; David, I.; Riviş, A.; Petrea, C.E.; Hădărugă, N.G. Nutritional values of edible chestnuts (Castanea species)—A short comparative review. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2021, 27, 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- De Vasconcelos, M.C.B.M.; Bennett, R.N.; Rosa, E.A.S.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V. Composition of European chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) and association with health effects: Fresh and processed products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A. Mediterranean diet as intangible heritage of humanity: 10 years on. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Fuentes, C.; Carballo, J. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic Content and Total Flavonoid Content in Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Cultivars Grown in Northwest Spain under Different Environmental Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musilová, J.; Fedorková, S.; Podhorecká, K.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Mesárošová, A.; Vollmannová, A.; Lidiková, J.; Čeryová, N.; Ňorbová, M.; Orsák, M. Carbohydrates and mineral substances in sweet chestnuts (Castanea sativa Mill.) from important growing areas in Slovakia. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, T.; Pereira, J.A.; Casal, S.; Ramalhosa, E. Bioactive compounds of chestnuts as health promoters. In Natural Bioactive Compounds from Fruits and Vegetables as Health Promoters: Part II; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, Saudi Arabia, 2016; pp. 132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli, A.; Napolitano, A.; Hošek, J.; Masullo, M.; Pizza, C.; Piacente, S. Antioxidant and In Vitro Preliminary Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Castanea sativa (Italian Cultivar “Marrone di Roccadaspide” PGI) Burs, Leaves, and Chestnuts Extracts and Their Metabolite Profiles by LC-ESI/LTQOrbitrap/MS/MS. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzoli, C.; Martinelli, G.; Fumagalli, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Maranta, N.; Colombo, L.; Piazza, S.; Dell’Agli, M.; Sangiovanni, E. Castanea sativa Mill. By-Products: Investigation of Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Ferreira, T.; Nascimento-Gonçalves, E.; Seixas, F.; Gil da Costa, R.M.; Martins, T.; Neuparth, M.J.; Pires, M.J.; Lanzarin, G.; Félix, L.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with Chestnut (Castanea sativa) Reduces Abdominal Adiposity in FVB/n Mice: A Preliminary Study. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleti, Ε.; Kossyva, V.; Maisoglou, I.; Vrontaki, M.; Manouras, V.; Tzereme, A.; Alexandraki, M.; Koureas, M.; Malissiova, E.; Manouras, A. The Nutritional Benefits and Sustainable By-Product Utilization of Chestnuts: A Comprehensive Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, S.I.; Taha, M.M.E.; Aljahdali, I.; Oraibi, B.; Alzahrani, A.; Farasani, A.; Alfaifi, H.; Babiker, Y. Exploring the potential of chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): A comprehensive review and conceptual mapping. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M.J.; Bunce, R.G.H.; Jongman, R.H.G.; Mücher, C.A.; Watkins, J.W. A climatic stratification of the environment of Europe. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2005, 14, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Dane, F.; Kubisiak, T.L.; Huang, H.W. Molecular evidence for an Asian origin and a unique westward migration of species in the genus Castanea via Europe to North America. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 43, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staton, M.; Addo-Quaye, C.; Cannon, N.; Yu, J.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Huff, M.; Islam-Faridi, N.; Fan, S.; Georgi, L.L.; Nelson, C.D. A reference genome assembly and adaptive trait analysis of Castanea mollissima ‘Vanuxem,’ a source of resistance to chestnut blight in restoration breeding. Tree Genet. Genomes 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Cherubini, M.; Micheli, E.; Villani, F.; Bucci, G. Role of domestication in shaping Castanea sativa genetic variation in Europe. Tree Genet. Genomes 2008, 4, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Costa, R.M.L.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Ribeiro, C.A.M.; da Silva, M.F.S.; Manzano, G.; Barreneche, T. Variation in grafted European chestnut and hybrids by microsatellites reveals two main origins in the Iberian Peninsula. Tree Genet. Genomes 2010, 6, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioni, C.; Martin, M.A.; Chiocchini, F.; Cherubini, M.; Gaudet, M.; Pollegioni, P.; Velichkov, I.; Jarman, R.; Chambers, F.M.; Paule, L.; et al. Landscape genetics structure of European sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill): Indications for conservation priorities. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauteri, M.; Pliura, A.; Monteverdi, M.C.; Brugnoli, E.; Villani, F.; Eriksson, G. Genetic variation in carbon isotope discrimination in six European populations of Castanea sativa Mill. originating from contrasting localities. J. Evol. Biol 2004, 17, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzonev, R.; Hinkov, G.; Karakiev, T. Ecological Characteristics of the Floristic Complex of the Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Forests in Belasitsa Mountain. Silva Balcanica 2011, 12, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Pinto, T.; Anjos, R.; Crespi, A.; Peixoto, F.; Pimentel-Pereira, M.; Coutinho, J.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Gomes-da-Costa, L.; Araújo-Alves, J. O castanheiro do ponto de vista botânico e ecofisiologico. In Castanheiros; Gomes-Laranjo, J., Ferreira-Cardoso, J., Portela, E., Abreu, C.G., Eds.; Edições UTAD: Vila Real, Portugal, 2007; pp. 43–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Kang, H.; Hui, N.; Yin, S.; Chen, Z.; Du, B.; Liu, C. Spatial variations in leaf trichomes and their coordination with stomata in Quercus variabilis across Eastern Asia. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Coutinho, J.P.; Galhano, V.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V. Differences in photosynthetic apparatus of leaves from different sides of the chestnut canopy. Photosynthetica 2008, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Dinis, L.; Coutinho, J.; Pinto, T.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Pimentel-Pereira, M.; Peixoto, F.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Effect of temperature and radiation on photosynthesis productivity in chestnut populations (Castanea sativa Mill. cv. Judia). Acta Agron. Hung. 2007, 55, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.; Ferreira-Pinto, A.; Pinto, T.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Predicting the behavior of chestnut cultivars grafted on ColUTAD under different edaphoclimatic conditions. In Proceedings of the VII International Chestnut Symposium, Lugo, Spain, 26–29 June 2023; Volume 1400, pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zoratti, L.; Karppinen, K.; Escobar, A.L.; Häggman, H.; Jaakola, L. Light-controlled flavonoid biosynthesis in fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljak, I.; Vahčić, N.; Liber, Z.; Šatović, Z.; Idžojtić, M. Morphological and chemical variation of wild sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) populations. Forests 2022, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezzi, E.; Donno, D.; Mellano, M.G.; Beccaro, G.L.; Gamba, G. Castanea spp. Nut Traceability: A Multivariate Strategy Based on Phytochemical Data. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.; Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Morais, M.C.; Bacelar, E.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. Composition of Nuts and Their Potential Health Benefits—An Overview. Foods 2023, 12, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucure, C.T.; Geana, E.-I.; Sandru, C.; Tita, O.; Botu, M. Phytochemical and Nutritional Profile Composition in Fruits of Different Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Cultivars Grown in Romania. Separations 2022, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecka, M.; Staňková, B.; Kutová, S.; Tomášová, P.; Tvrzická, E.; Žák, A. Comprehensive sterol and fatty acid analysis in nineteen nuts, seeds, and kernel. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.J.; Pinto, T.; Vilela, A. Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Nutritional and Phenolic Composition Interactions with Chestnut Flavor Physiology. Foods 2022, 11, 4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathopoulou, M.G.; Kanoni, S.; Papanikolaou, G.; Antonopoulou, S.; Nomikos, T.; Dedoussis, G. Mineral intake. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2012, 108, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto, E.B.; Sampaio, A.C.; Campos, J.R.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Aires, A.; Silva, A.M. Chapter 2-Polyphenols for skin cancer: Chemical properties, structure-related mechanisms of action and new delivery systems. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 63, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, T.E.; Souto, E.B.; Silva, A.M. Selected Flavonoids to Target Melanoma: A Perspective in Nanoengineering Delivery Systems. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Abouelenein, D.; Acquaticci, L.; Alessandroni, L.; Abd-Allah, R.H.; Borsetta, G.; Sagratini, G.; Maggi, F.; Vittori, S.; Caprioli, G. Effect of Roasting, Boiling, and Frying Processing on 29 Polyphenolics and Antioxidant Activity in Seeds and Shells of Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). Plants 2021, 10, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, A.; Kunc, P.; Zamljen, T.; Hudina, M.; Veberic, R.; Solar, A. Identification and Quantification of the Major Phenolic Constituents in Castanea sativa and Commercial Interspecific Hybrids (C. sativa x C. crenata) Chestnuts Using HPLC–MS/MS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Silva, A.M.; Freitas, V.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Microwave-Assisted Extraction as a Green Technology Approach to Recover Polyphenols from Castanea sativa Shells. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vasconcelos, M.d.C.B.M.; Bennett, R.N.; Quideau, S.; Jacquet, R.; Rosa, E.A.S.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.V. Evaluating the potential of chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) fruit pericarp and integument as a source of tocopherols, pigments and polyphenols. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Moreira, M.M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Insights into the digestion of chestnut (Castanea sativa) shells bioactive extracts—Ultrasound vs. microwave-assisted extraction. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5128–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurek, N.; Pawłowska, A.M.; Pycia, K.; Potocki, L.; Kapusta, I.T. Quantitative and Qualitative Determination of Polyphenolic Compounds in Castanea sativa Leaves and Evaluation of Their Biological Activities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Veríssimo, L.; Finimundy, T.; Rodrigues, J.; Oliveira, I.; Gonçalves, J.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.C. Chemical and Bioactive Screening of Green Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Chestnut By-Products: An Approach to Guide the Sustainable Production of High-Added Value Ingredients. Foods 2023, 12, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.; Addamo, A.; Malfa, G.A.; Acquaviva, R.; Di Giacomo, C.; Tomasello, B.; La Mantia, A.; Ragusa, M.; Toscano, M.A.; Lupo, G.; et al. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer activities of Castanea sativa (Fagaceae) extract: New therapeutic perspectives. Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2021, 155, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Vieira, E.F.; Peixoto, A.F.; Freire, C.; Freitas, V.; Costa, P.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Optimizing the extraction of phenolic antioxidants from chestnut shells by subcritical water extraction using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C.; Grillo, G.; Binello, A.; Gallina, L.; Olivares-Vicente, M.; Herranz-López, M.; Micol, V.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Cravotto, G. Bioactive Antioxidant Compounds from Chestnut Peels through Semi-Industrial Subcritical Water Extraction. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Souto, E.B.; Schäfer, J.; Santos, J.A.; Bunzel, M.; Nunes, F.M. Thymus zygis subsp. zygis an Endemic Portuguese Plant: Phytochemical Profiling, Antioxidant, Anti-Proliferative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, R.; Trezza, A.; Bernini, A.; Millucci, L.; Geminiani, M.; Santucci, A. Antioxidant Bio-Compounds from Chestnut Waste: A Value-Adding and Food Sustainability Strategy. Foods 2025, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lameirão, F.; Pinto, D.; Vieira, E.F.; Peixoto, A.F.; Freire, C.; Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Costa, P.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Green-Sustainable Recovery of Phenolic and Antioxidant Compounds from Industrial Chestnut Shells Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction: Optimization and Evaluation of Biological Activities In Vitro. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Lagos, L.; Luu, T.V.; De Haan, B.; Faas, M.; De Vos, P. TLR2 and TLR4 activity in monocytes and macrophages after exposure to amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline and erythromycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 2972–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, S.; Greco, G.; Angelini, S.; Hrelia, P.; Fimognari, C.; Lenzi, M. Antimutagenicity and Antioxidant Activity of Castanea sativa Mill. Bark Extract. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, J.A.; Mihailović, M.; Uskoković, A.S.; Grdović, N.; Dinić, S.; Poznanović, G.; Mujić, I.; Vidaković, M. Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antiglycation Effects of Lactarius deterrimus and Castanea sativa Extracts on Hepatorenal Injury in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Almeida, A.; López-Yerena, A.; Pinto, S.; Sarmento, B.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Appraisal of a new potential antioxidants-rich nutraceutical ingredient from chestnut shells through in-vivo assays—A targeted metabolomic approach in phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, A.; Ciccone, V.; Loppi, S.; Morbidelli, L. Promising Support Coming from Nature: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Castanea sativa Wood Distillate on Skin Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 9386–9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frusciante, L.; Geminiani, M.; Olmastroni, T.; Mastroeni, P.; Trezza, A.; Salvini, L.; Lamponi, S.; Spiga, O.; Santucci, A. Repurposing Castanea sativa Spiny Burr By-Products Extract as a Potentially Effective Anti-Inflammatory Agent for Novel Future Biotechnological Applications. Life 2024, 14, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiocchio, I.; Prata, C.; Mandrone, M.; Ricciardiello, F.; Marrazzo, P.; Tomasi, P.; Angeloni, C.; Fiorentini, D.; Malaguti, M.; Poli, F.; et al. Leaves and Spiny Burs of Castanea sativa from an Experimental Chestnut Grove: Metabolomic Analysis and Anti-Neuroinflammatory Activity. Metabolites 2020, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciola, N.A.; Squillaci, G.; D’Apolito, M.; Petillo, O.; Veraldi, F.; La Cara, F.; Peluso, G.; Margarucci, S.; Morana, A. Castanea sativa Mill. Shells Aqueous Extract Exhibits Anticancer Properties Inducing Cytotoxic and Pro-Apoptotic Effects. Molecules 2019, 24, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Silva, A.M.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Sut, S.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion of Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) Shell Extract Prepared by Subcritical Water Extraction: Bioaccessibility, Bioactivity, and Intestinal Permeability by In Vitro Assays. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taketo, M.; Schroeder, A.C.; Mobraaten, L.E.; Gunning, K.B.; Hanten, G.; Fox, R.R.; Roderick, T.H.; Stewart, C.L.; Lilly, F.; Hansen, C.T.; et al. FVB/N: An inbred mouse strain preferable for transgenic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 2065–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.T.; Fu, Y.J.; Jiang, J.C. Bioactive constituents, nutritional benefits and woody food applications of Castanea mollissima: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Moreira, M.M.; Vieira, E.F.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Brezo-Borjan, T.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Development and Characterization of Functional Cookies Enriched with Chestnut Shells Extract as Source of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds. Foods 2023, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, A.; Widelska, G.; Wójtowicz, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Dib, A.; Matwijczuk, A. Content of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of New Gluten-Free Pasta with the Addition of Chestnut Flour. Molecules 2019, 24, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.X.; Wang, M.H.; Chen, L.; Zheng, B. Impact of using whole chestnut flour as a substitute for cake flour on digestion, functional and storage properties of chiffon cake: A potential application study. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, F.; Ochmian, I.; Sobolewska, M. Quality and technological properties of flour with the addition of Aesculus hippocastanum and Castanea sativa. Acta Univ. Cinbinesis Ser. E Food Technol. 2022, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, A.; Russo, D.; Cervini, M.; Magni, C.; Giuberti, G.; Marti, A. Starch and Protein Characteristics of Chestnut Flours and Their Applications in Gluten-Free Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25298–25305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascone, G.; Oliviero, M.; Sorrentino, L.; Crescente, G.; Boscaino, F.; Sorrentino, A.; Volpe, M.G.; Moccia, S. Mild Approach for the Formulation of Chestnut Flour-Enriched Snacks: Influence of Processing Parameters on the Preservation of Bioactive Compounds of Raw Materials. Foods 2024, 13, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littardi, P.; Paciulli, M.; Carini, E.; Rinaldi, M.; Rodolfi, M.; Chiavaro, E. Quality evaluation of chestnut flour addition on fresh pasta. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 126, 109303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, G.; Pinnavaia, G.G.; Guidolin, E.; Dalla Rosa, M. Effects of extrusion temperature and feed composition on the functional, physical and sensory properties of chestnut and rice flour-based snack-like products. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Pan, X.; Chang, X. Chestnuts in fermented rice beverages increase metabolite diversity and antioxidant activity while reducing cellular oxidative damage. Foods 2022, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Solà, J.; Almeida, D.; López-Mas, L.; Kallas, Z.; Abadias, M.; Barros, L.; Martín-Gómez, H.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Sensory optimization of gluten-free hazelnut omelette and sugar-modified chestnut pudding: A free choice profiling approach for enhanced traditional recipe formulations. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 5302–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.Q.; Wang, B.; Cheng, Y.T.; Lv, W.Q.; Zeng, S.Y.; Xiao, H.W. Printing characteristics and microwave infrared-induced 4D printing of chestnut powder composite paste. J. Food Eng. 2024, 382, 112197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.Z.; An, J.Y.; Wang, L.T.; Fan, X.H.; Lv, M.J.; Zhu, Y.W.; Chang, Y.H.; Meng, D.; Yang, Q.; Fu, Y.J. Development of fermented chestnut with Bacillus natto: Functional and sensory properties. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; López-Yerena, A.; Almeida, A.; Sarmento, B.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Metabolomic insights into phenolics-rich chestnut shells extract as a nutraceutical ingredient—A comprehensive evaluation of its impacts on oxidative stress biomarkers by an in-vivo study. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.; Alves Heleno, S.; Magalhaes Pinto Paiva, F.; Bento, A.A. Process for the Production of Wine Using Flowers of Castanea sativa Mill as Natural Preservatives in Alternative to the Addition of Sulphites. U.S. Patent US20180127693, 2 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, D.; Lameirao, F.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F.; Costa, P. Characterization and Stability of a Formulation Containing Antioxidants-Enriched Castanea sativa Shells Extract. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.S.; Luo, S.H.; Zhou, S.; Fan, H.Y.; Lv, C.M. Preparation of nano-selenium from chestnut polysaccharide and characterization of its antioxidant activity. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1054601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajic, M.; Oberlintner, A.; Korge, K.; Likozar, B.; Novak, U. Formulation of active food packaging by design: Linking composition of the film-forming solution to properties of the chitosan-based film by response surface methodology (RSM) modelling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, T.; Silva, N.H.C.S.; Almeida, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Piccinelli, A.; Aquino, R.P.; Sansone, F.; Mencherini, T.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R. Valorisation of chestnut spiny burs and roasted hazelnut skins extracts as bioactive additives for packaging films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 151, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, W.; Kluska, D.; Staniek, N.; Grzybek, P.; Shakibania, S.; Guzdek, B.; Golombek, K.; Matus, K.; Shyntum, D.Y.; Krukiewicz, K.; et al. Advantageous effect of calcium carbonate and chestnut extract on the performance of chitosan-based food packaging materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, W.; Nowotarski, M.; Ledniowska, K.; Shyntum, D.Y.; Krukiewicz, K.; Turczyn, R.; Sabura, E.; Furgol, S.; Kudla, S.; Dudek, G. Modulation of physicochemical properties and antimicrobial activity of sodium alginate films through the use of chestnut extract and plasticizers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korge, K.; Bajic, M.; Likozar, B.; Novak, U. Active chitosan-chestnut extract films used for packaging and storage of fresh pasta. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3043–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Peng, F.; Niu, K.; Hou, W.L.; Du, B.; Yang, Y.D. Development of Chitosan-Based Films Incorporated with Chestnut Flower Essential Oil That Possess Good Anti-Ultraviolet Radiation and Antibacterial Effects for Banana Storage. Coatings 2024, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardejn, S.; Waclawek, S.; Dudek, G. Improving Antimicrobial Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films in Food Packaging: Key Factors and Their Impact. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takma, D.K.; Bozkurt, S.; Koc, M.; Korel, F.; Nadeem, H.Ş. Optimizing a bionanocomposite film for active food packaging with pectin, gelatin, and chestnut shell extract-loaded zein nanoparticles. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 42, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korge, K.; Seme, H.; Bajic, M.; Likozar, B.; Novak, U. Reduction in Spoilage Microbiota and Cyclopiazonic Acid Mycotoxin with Chestnut Extract Enriched Chitosan Packaging: Stability of Inoculated Gouda Cheese. Foods 2020, 9, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Falco, V.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; Silva, A.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Amaral, J.S.; Igrejas, G.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; et al. Evaluation of the Phenolic Profile of Castanea sativa Mill. By-Products and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity against Multiresistant Bacteria. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donno, D.; Beccaro, G.L.; Mellano, M.G.; Bonvegna, L.; Bounous, G. Castanea spp. buds as a phytochemical source for herbal preparations: Botanical fingerprint for nutraceutical identification and functional food standardisation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2863–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donno, D.; Turrini, F.; Boggia, R.; Guido, M.; Gamba, G.; Mellano, M.G.; Riondato, I.; Beccaro, G.L. Sustainable Extraction and Use of Natural Bioactive Compounds from the Waste Management Process of Castanea spp. Bud-Derivatives: The FINNOVER Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, S.X.; Peng, H.X.; Li, H.L.; Zhang, M.J.; Ning, L.; Wang, S.; et al. Comprehensive curation and validation of genomic datasets for chestnut. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vielba, J.M.; Vidal, N.; San José, M.C.; Rico, S.; Sánchez, C. Recent Advances in Adventitious Root Formation in Chestnut. Plants 2020, 9, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M.; Manetti, M.C.; Giudici, F.; Amorini, E. Distribution and economic potential of the Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Europe. Ecol. Mediterr. 2004, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.; Marques, T.; Pinto, T.; Raimundo, F.; Borges, A.; Caço, J.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Relating plant and soil water content to encourage smart watering in chestnut trees. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Almeida, P.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Peixoto, F. Ecophysiological characterization of C. sativa trees growing under different altitudes. In Proceedings of the IV International Chestnut Symposium, Beijing, China, 25 September 2008; Volume 844, pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dinis, L.; Peixoto, F.; Pinto, T.; Costa, R.; Bennett, R.; Gomes-Laranjo, J. Study of morphological and phenological diversity in chestnut trees (‘Judia’ variety) as a function of temperature sum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 70, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigling, D.; Prospero, S. Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight: Invasion history, population biology and disease control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellana, S.; Martin, M.Á.; Solla, A.; Alcaide, F.; Villani, F.; Cherubini, M.; Neale, D.; Mattioni, C. Signatures of local adaptation to climate in natural populations of sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) from southern Europe. Ann. For. Sci. 2021, 78, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klincewicz, K.; Zatorska, M.; Wielicka-Regulska, A. The role of higher education in creating socially responsible innovations: A case study of the EIT food RIS consumer engagement labs project. Soc. Innov. High. Educ. 2022, 1, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, M.; Gartzlaff, M. Responsible research and innovation: Hopes and fears in the scientific community in Europe. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, N.; Rodrigues, F.; PP Oliveira, M.B. Castanea sativa by-products: A review on added value and sustainable application. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions-The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. Evolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: Concepts, analysis and interventions. In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Chlorophyll (μg/cm2) | Carotenoids (μg/cm2) | Total (μg/cm2) | Chla/Chlb | Chl/Car |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judia | 113.3 | 29.3 | 142.6 | 3.60 | 3.87 |

| Longal | 103.0 | 26.3 | 129.3 | 4.01 | 3.92 |

| Martaínha | 85.7 | 19.5 | 105.2 | 4.35 | 4.39 |

| Compound Class | Compound Subclass | Compound | Concentration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | ~50% FW | [8] | ||

| Protein | 2–7% FW | [32] | ||

| Lipids | Total Fat | 1.4–3.0 g/100 g FW | [13] | |

| Fatty acids (per 100 g FW) | Monounsaturated (total) | 0.78 g | [31,34] | |

| Oleic acid (C18:1 n-9) | 0.749 g | [31] | ||

| Palmitoleic acid (16:1 n-7) | 0.021 g | |||

| Polyunsaturated (total) | 0.894 g | [31,34] | ||

| Linoleic acid (18:2 n-6) | 0.798 g | [31] | ||

| α-Linolenic acid (18:3 n-3) | 0.095 g | |||

| Carbohydrates | Total carbohydrates (DW) | 70–80 g/100 g DW | [8] | |

| Fiber | 4–10% FW | [8,32] | ||

| Individual soluble sugars (per 100 g DW) | Total soluble sugars | 51–57 g | [30] | |

| Glucose | 0.18–3.15 g | [8,32] | ||

| Fructose | 0.27–3.17 g | |||

| Maltose | 0.17–1.58 g | |||

| Sucrose | 9.36–29.89 g | |||

| Vitamins | Vitamin C | 0–6.87 mg/100 g, DW | [30] | |

| 40.2 mg/100 g FW | [13,34] | |||

| Folates | 58 µg/100 g FW | |||

| Niacin | 1.1 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Pantothenic acid | 0.48 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Riboflavin | 0.02 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Thiamin | 0.14 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Vitamin A | 26 IU/100 g FW | |||

| Minerals | Macrominerals | Potassium | 484 mg/100 g FW | [32] |

| 377–789 mg/100 g DW | [8] | |||

| Phosphorus | 38 mg/100 g FW | [34] | ||

| 96.5 to 179 mg/100 g DW | [8] | |||

| Magnesium | 30 mg/100 g FW | [34] | ||

| 58.7 to 101 mg/100 g DW | [8] | |||

| Calcium | 19 mg/100 g FW | [34] | ||

| 26.9–103 mg/100 g DW | [8] | |||

| Trace minerals | Cooper | 0.418 mg/100 g FW | [34] | |

| Iron | 0.94 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Manganese | 0.336 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Zinc | 0.49 mg/100 g FW | |||

| Sodium | 2 mg/100 g FW | |||

| 0.65 to 6.90 mg/100 g DW | [8] |

| Compound Subclass | Compound | Concentration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxycinnamic acids (caffeic, coumaric, ferulic, and chlorogenic) | 4.06 ± 0.03 to 62.89 ± 0.22 mg/100 g, DW | [30] | |

| 0.91 ± 0.15 to 4.44 ± 0.21 mg/kg FW | [39] | ||

| Hydroxybenzoic acids (gallic acid and derivatives) | 86.44 ± 13.01 to 185.54 ± 11.40 mg/kg FW | ||

| Gallic acid | 23.30 ± 0.07 mg/kg DW | [38] | |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 0.15 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.94 ± 0.07 mg/kg DW | ||

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 1.43 ± 0.10 mg/kg DW | ||

| Caffeic acid | 3.15 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Vanillic acid | 9.35 ± 0.04 mg/kg DW | ||

| Syringic acid | 0.26 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| p-Coumaric acid | 6.73 ± 0.03 mg/kg DW | ||

| Ferulic acid | 3.37 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Flavonoids | Flavonols (hyperoside, isoquercitrin, quercetin, quercitrin, and rutin) | 0 to 8.62 ± 0.03 (mg/100 g, DW) | [30] |

| 9.64 ± 1.37 to 78.97 ± 2.03 mg/kg FW | [39] | ||

| Catechins (catechin and epicatechin) | 5.71 ± 0.90 to 39.40 ± 0.34(mg/100 g, DW) | [30] | |

| 4.56 ± 0.01 to 74.17 ± 0.13 mg/kg DW | [38] | ||

| Procyanidin A2 | 0.42 ± 0.02 mg/kg DW | ||

| Procyanidin B2 | 8.67 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Rutin | 1.59 ± 0.03 mg/kg DW | ||

| Isoquercitrin | 2.17 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Hyperoside | 2.91 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Quercitrin | 0.08 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Myricetin | 0.60 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Kaempferol-3-glucoside | 0.12 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Quercetin | 0.22 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Isorhamnetin | 0.07 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Kaempferol | 0.98 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Phloridzin | 6.82 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | ||

| Phloretin | 2.09 ± 0.03 mg/kg DW | ||

| Tannins | Castalagin and vescalagin | 5.44 ± 0.09 to 24.79 ± 0.43 mg/100 g, DW | [30] |

| Ellagic acid | - | [10] | |

| 26.73 ± 0.02 mg 100/g DW | [30] | ||

| 11.11 ± 0.01 mg/kg DW | [38] |

| Compound Subclass | Compound | Concentration | By-Product | Extraction Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | Crenatin | 0.90 ± 0.09 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] |

| 15.77 ± 1.17 mg/100 g | Leaves | ||||

| Gallic acid | 81.52 ± 0.99 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| 7.24 ± 0.17 to 10.86 ± 0.092 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| 3.78 ± 0.056 to 14.84 ± 0.02 mg/g | Shells | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| 3.14 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | ||

| 257.56 ± 12.88 to 263.22 ± 13.16 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | ||

| 4.28 ± 0.03 to 17.55 ± 0.067 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Protocatechuic acid | 38.20 ± 1.91 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Vanillic acid | 0.55 ± 0.03 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Syringic acid | 0.02 ± 0.00 to 0.16 ± 0.01 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Methyl-gallate | 19.07 ± 0.17 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 2.29 ± 0.11 to 9.71 ± 0.49 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Caftaric acid | 1.52 ± 0.08 to 8.13 ± 0.41 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | 1.01 ± 0.05 to 1.73 ± 0.09 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| 4-O-caffeyolquinic acid | 0.76 ± 0.04 to 6.14 ± 0.31 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Caffeic acid | 0.63 ± 0.03 to 0.66 ± 0.03 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| p-Coumaric acid | 0.32 ± 0.02 to 0.46 ± 0.02 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Ferulic acid | 0.15 ± 0.01 to 0.22 ± 0.01 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | |

| Flavonoids | Quercetin-3-O-β-D- -glucopyranoside | 0.04 ± 0.002 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] |

| 3.37 ± 0.12 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | |||

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 10.61 ± 0.29 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] | |

| 50.33 ± 1.87 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | |||

| Quercetin-3-O-α-L- -rhamnopyranoside | 3.06 ± 0.24 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | [10] | |

| Quercetin-3-O- -glucuronide | 137.73 ± 4.19 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| 1.12 ± 0.05 to 4.23 ± 0.32 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| 0.36 ± 0.004 to 1.66 ± 0.15 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Quercetin-3-O- -rutinoside | 0.33 ± 0.01 to 1.54 ± 0.07 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | |

| 0.18 ± 0.004 to 2.67 ± 0.12 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Quercetin-3-O- -glucoside | 184.30 ± 4.02 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| Quercetin-O- -hexoside | 0.25 ± 0.04 to 3.03 ± 0.12 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | |

| 0.063 ± 0.001 to 1.18 ± 0.05 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Kaempferol-3-O- -glucoside | 61.60 ± 1.39 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| 0.39 ± 0.04 to 6.98 ± 0.1 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| 0.1 ± 0.002 to 0.41 ± 0.01 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Isorhamnetin-3-O- -glucoside | 22.33 ± 0.64 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O- -rutinoside | 0.93 ± 0.05 to 3.08 ± 0.2 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | |

| 0.10 ± 0.005 to 0.83 ± 0.07 mg/g | Burs | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Myricetin-3- -glucoside | 0.07 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | |

| Gallocatechin | 0.76 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | |

| Catechin | 0.15 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | |

| 8.14 ± 0.41 to 10.35 ± 0.52 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE; MAE | |||

| Epicatechin | 0.03 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | |

| 0.53 ± 0.03 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | |||

| Tannins | Chestanin | 3.23 ± 0.06 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] |

| 85.84 ± 2.18 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | |||

| Cretanin | 16.75 ± 2.24 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] | |

| 0.186 ± 0.002 to 3.66 ± 0.17 mg/g | Burs | MeOH | |||

| 95.2 ± 7.21 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | |||

| 1.01 ± 0.05 to 1.87 ± 0.13 mg/g | Leaves | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| Ellagitannis | 436.93 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| Gallotannins | 13.51 ± 0.19 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] | |

| Ellagic acid | 3.09 ± 0.25 mg/100 g | Burs | MeOH | [10] | |

| 0.9 mg/g DW | Shells | MAE-EtOH | [40] | ||

| 0.33 ± 0.003 to 1.81 ± 0.04 mg/g | Shells | MAC-EtOH, UAE-EtOH, MAE-w | [44] | ||

| 7.97 ± 0.59 mg/100 g | Leaves | MeOH | [10] | ||

| 3.94 ± 0.20 to 4.04 ± 0.20 mg/g DW | Shells | UAE-EtOH; MAE-w | [42] | ||

| Ellagic acid pentoside | 15.59 ± 2.49 mg/100 g DW | Leaves | UAE-MeOH | [43] |

| Application Area | Chestnut Component Used | Key Active Substances | Main Benefits | Example Product/Use | Commercial Example | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional bakery goods | Chestnut flour; chestnut shell extract | Polyphenols, flavonoids, fiber | Antioxidant enhancement, improved sensory profile, gluten-free | Cookies and pancakes | Cookies and crispbread with chestnut flour (e.g., Amisa®) | [13,62] |

| Nutraceuticals | Shell/bur extracts; leaf extracts | Polyphenols, tannins, tocopherols | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, oxidative stress reduction | Supplements, capsules, extracts, concentrated powders | Light Sweet Chestnut de Esencias Triunidad® | [49,74] |

| Food preservation | Shell/wood extracts; polysaccharides | Tannins, phenolics | Natural antioxidant and antimicrobial protection | Meat, bakery, dairy | Chestnut flowers as a substitute for SO2 in wines (patented [75]). | [13,49,76] |

| Dietary fiber source | Chestnut flour; shell fiber | Insoluble and soluble fiber, resistant starch | Gut health, metabolic regulation | Fiber-enriched foods | - | [13,61,76] |

| Bread, cakes, pasta | Chestnut flour (for recipe substitution) | Fiber, minerals, natural sugars | Higher dietary fiber, antioxidant potential, and improved flavor | Chestnut flour (10–50% substitution) | Organic Chestnut Tagliatelle (Pasta D’Alba®) | [63,64,65,66,68] |

| Snacks, extrudates | Chestnut flour blends | Polyphenols, fiber, carbohydrates | Improved texture, flavor, and nutritional quality | Extruded snacks, bars | - | [67,69] |

| Fermented beverages | Chestnut flour | Sugars, phenolics | Enhanced antioxidant capacity, flavor diversification, and fermentation substrate | Fermented beverages | Artisanal Judia beer and gin (JUDIA®) | [70] |

| 3D/4D printed foods | Chestnut–alginate composite | Fiber, polysaccharides | Novel textures, personalized nutrition | 4D-printed food matrices | - | [72] |

| Film Matrix | Sample | Key Benefits | Food Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pullulan | Spiny burs | Antioxidant, antibacterial, UV barrier | General packaging | [79] |

| Chitosan | Shell, wood, extract | Antimicrobial, improved barrier | Cheese, pasta | [80,82,86] |

| Alginate | Extract | Enhanced mechanical/antimicrobial | General packaging | [81,84] |

| Pectin/gelatin/zein | Shell extract | Antioxidant, low permeability | Oil, general food | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Silva, A.M.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Marques, T.; Coutinho, T.E.; Teixeira, A.L.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, C. Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Composition, Health-Promoting Properties, and Technological Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413069

Gomes-Laranjo J, Silva AM, Martins-Gomes C, Marques T, Coutinho TE, Teixeira AL, Vilela A, Gonçalves C. Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Composition, Health-Promoting Properties, and Technological Applications. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413069

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes-Laranjo, José, Amélia M. Silva, Carlos Martins-Gomes, Tiago Marques, Tiago E. Coutinho, Ana Luísa Teixeira, Alice Vilela, and Carla Gonçalves. 2025. "Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Composition, Health-Promoting Properties, and Technological Applications" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413069

APA StyleGomes-Laranjo, J., Silva, A. M., Martins-Gomes, C., Marques, T., Coutinho, T. E., Teixeira, A. L., Vilela, A., & Gonçalves, C. (2025). Bioactive Compounds in Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.): Composition, Health-Promoting Properties, and Technological Applications. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413069