Abstract

Over-constraint issues frequently arise in complex models with multiple constraints, such as those used in multibody systems and contact analyses. When over-constraints exist, commonly used constraint-handling methods, such as the transformation method, the Lagrange multiplier method, and the penalty method, can produce small or zero pivot values in the system matrix. This may result in non-convergence, slow convergence, or incorrect solutions. Furthermore, in the transformation method, in which the slave degrees of freedom (DOFs) corresponding to each constraint equation are eliminated, most finite element software restricts the reuse of slave DOFs that have already been referenced in other constraint equations. This makes an already complex modeling process even more challenging. This paper first summarizes a systematic algorithm proposed by Cho for detecting and resolving over-constraints in linear constraint equations, highlighting its efficiency in less complex scenarios but also its limitations for large-scale models due to excessive computation time. To address these limitations, this paper introduces a new algorithm that leverages the sparsity of the constraint matrix and applies sparse QR factorization without generating a dense Q matrix. The effectiveness of this approach in handling complex, large-scale finite element (FE) models is demonstrated, confirming its applicability to complex engineering problems.

1. Introduction

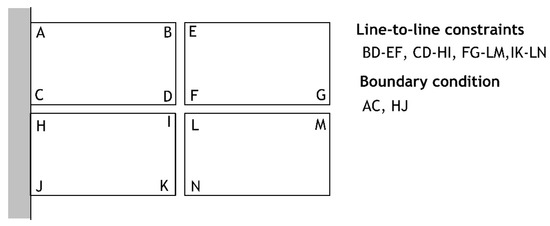

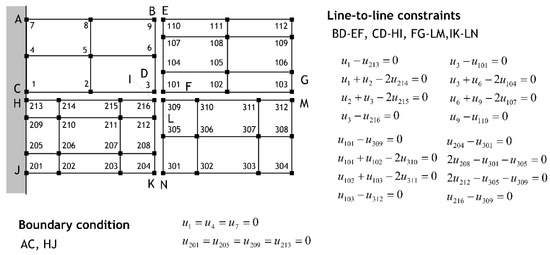

Over-constraint problems frequently occur in complex finite element (FE) models that use numerous constraints, contact analyses, and multibody systems subjected to constraints. The presence of over-constraints can cause difficulties in obtaining a stable solution, as solvers may encounter small or zero pivots regardless of the constraint-handling method—transformation method, Lagrange multiplier method, or penalty method. A typical over-constraint problem is illustrated in Figure 1. Three constraint equations are required at nodes D, F, I, and L for them to move together, but four constraints are generated owing to the superposition of four line-to-line constraints. Hence, one redundant over-constraint must be removed. In addition, the constraint between nodes C and H created by the line-to-line condition conflicts with the specified boundary condition at those nodes. To resolve this issue, constraints should not be imposed as line-to-line relationships; instead, each degree of freedom (DOF) should be constrained individually to prevent over-constraints [1,2,3,4]. This process is tedious and prone to error.

Figure 1.

Typical over-constraint problem.

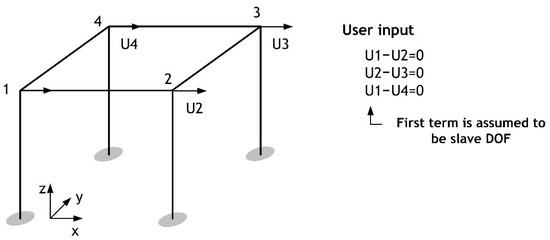

Particular attention should be given to handling constraints using the transformation method when addressing over-constraint problems. Figure 2 depicts a simple three-dimensional frame structure in which the DOFs on the first floor are constrained in the X-direction. Most FE software restricts the reuse of slave DOFs that have already been assigned in another constraint equation. Consequently, in programs that automatically assign the first DOF appearing in each constraint equation as the slave DOF, the user input shown in Figure 2 results in an error. In such cases, the constraints that can be processed by the program are , , and . Care must be taken when selecting slave DOFs while imposing constraints [1,2,3,4].

Figure 2.

Input-inducing errors in the transformation method.

Cho [5] proposed a systematic algorithm in his Ph.D. dissertation for detecting and resolving over-constraints that frequently occur in FE models with linear constraint equations. The algorithm is based on Gaussian elimination with column pivoting and can automatically select slave DOFs in the transformation method and reconstruct appropriate constraint equations. This algorithm performs well when the constraints are not overly complex. However, in large-scale models with highly coupled or complex constraints, it requires excessive computation time, making it necessary to consider the sparsity of the constraint matrix. ANSYS introduced the capability to automatically compute slave DOFs and detect over-constrained DOFs through the OVCHECK command, beginning with version 18.2 [6]. This command provides two options for detecting over-constraints: a default topological approach and an algebraic approach. The topological approach is faster but less robust, whereas the algebraic approach is more accurate but computationally demanding. Slave DOFs are determined using factorization with full pivoting applied to the constraint matrix. If a pivot is too small, the corresponding constraint equation is regarded as redundant and removed from the set of equations to be satisfied. When redundant constraints are detected, the program outputs information about their removal. This procedure is similar to that proposed by Cho [5].

This paper first reviews the systematic algorithm proposed in [5] and then presents a new algorithm that accounts for the sparsity of the constraint matrix in large-scale FE models with complex constraints. The proposed method employs sparse QR factorization without generating a dense Q matrix and has proven effective for complex, large-scale problems. A key contribution of this study is that the proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization is formulated specifically for an under-determined constraint system, where explicitly forming the orthogonal matrix Q would destroy sparsity and render large-scale analysis impractical; the Q-less formulation therefore provides a necessary and scalable mechanism for stable rank detection and redundancy elimination.

2. Systematic Approach for Detecting and Resolving Over-Constraints

This section summarizes the algorithm proposed by Cho [5] for detecting and resolving over-constraints in linear static systems subjected to linear constraint conditions. The fundamental equations are expressed as

with

where K is an stiffness matrix, u is an vector of DOFs, and f is the corresponding force vector. C is an matrix of coefficients, and b is an vector of constants. denotes the number of DOFs, and is the number of constraint equations. Generally, the constraint equation can be formulated as a vector function . However, the constraints commonly encountered in finite element modeling are typically expressed as linear relationships among the DOFs. The algorithm proposed in [5] is therefore limited to linear constraint conditions of the form (2). For nonlinear or dynamic systems, since solving the problem involves equations in the form of (1), the algorithm presented in this section can still be applied, provided that the constraint conditions remain linear.

2.1. Solution Methods for Systems of Equations with Constraints

Representative methods for handling constraints include the transformation method, the Lagrange multiplier method, and the penalty method. These methods are briefly reviewed below. The transformation method classifies the degrees of freedom (DOFs) into slave DOFs corresponding to each constraint equation and master DOFs for the remaining variables.

This method handles the constraints by eliminating the slave DOFs through the transformation of the entire system of equations. Equations (1) and (2) can be rewritten as follows by distinguishing the slave–master DOFs:

subject to

In Equation (3), the dimensions of the submatrices , , , are, respectively, , , , and . The vectors , , , and have dimensions , , , and , respectively. In Equation (4), the dimensions of and are and . Here, denotes the number of slave DOFs (or the number of constraints), and is the number of master DOFs; thus, the total number of DOFs is given by . If the inverse matrix of exists, Equation (4) can be arranged as follows:

where with dimension , and with dimension In order to implement transformation, the whole DOFs u should be expressed as follows in terms of the master DOFs:

Using the transformation in Equation (6), a condensed system in which the slave DOFs have been removed from the whole system of equations can be constituted. Applying the transformation of Equation (6) in Equation (3), the following condensed system can be obtained [7]:

where

Even though the transformation method reduces the dimension of the system matrix, it requires explicit partitioning of slave and master DOFs and involves complex implementation in program coding [1,2]. Because of this partitioning issue, most programs adopt user input in the form of Equation (5) and prohibit the reuse of already assigned slave DOFs in other constraint equations [1,2]. To simplify implementation, a homogeneous linear constraint (Q = 0) is often assumed. In this case, the last two terms on the right-hand side of Equation (9) vanish, and condensation of the force vector can be performed more easily. When nonhomogeneous constraints exist, dummy DOFs are introduced to handle them [1,2].

The Lagrange multiplier and penalty methods offer simpler implementation than the transformation method and are also capable of handling nonlinear constraints. For a linear static problem, the governing equations of these two methods can be formulated as follows [7]:

where in Equation (10) is the Lagrange multiplier vector of dimension of , in Equation (11) is a diagonal matrix of penalty parameters of dimension . In the Lagrange multiplier method, additional variables (Lagrange multipliers) are introduced, which increase the size of the system matrix and may compromise positive definiteness. Nevertheless, this method is straightforward to implement and provides exact enforcement of the constraints. Conversely, the penalty method preserves the original matrix size and is easy to implement, but it yields an approximate solution depending on the magnitude of the penalty parameters.

Although classical techniques such as the transformation method, the Lagrange multiplier method, and the penalty method are well established, their limitations become more pronounced in large-scale sparse finite element models. The transformation method can introduce substantial fill-in, destroying matrix sparsity; the Lagrange multiplier method produces an indefinite saddle-point system whose conditioning deteriorates with an increasing number of constraints; and penalty methods become sensitive to the choice of penalty parameters in high-dimensional settings.

A few studies have examined redundant constraints in more specialized areas. For example, redundant or rank-deficient constraint matrices have been analyzed in multibody system dynamics [8,9]. However, these works are problem-specific and do not provide general numerical algorithms for automatically detecting and eliminating redundant constraints in large, sparse finite element systems. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, systematic methods that resolve over-constraints through sparsity-preserving factorizations such as Q-less sparse QR have not been reported, underscoring the need for the present study.

2.2. Gauss Elimination-Based Algorithm

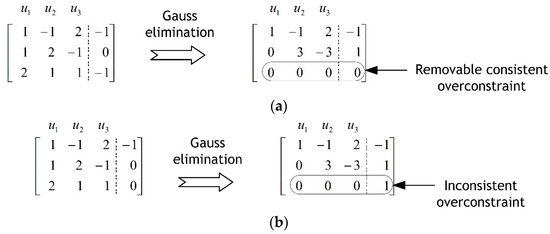

From a mathematical point of view, over-constraints frequently encountered when handling constraint equations indicate that the matrix C in Equation (2) is rank-deficient. In other words, the given constraints are not linearly independent. Over-constraints can be classified as either consistent or inconsistent. Consistent over-constraints can be eliminated from the constraint equations, whereas inconsistent over-constraints represent errors in the constraint formulation [1,2]. For example, assume the following constraint equations:

In the constraint Equations (12)–(14), the rank of the coefficient matrix C is 2, indicating that the matrix is rank-deficient. Equation (14) can be expressed as a linear combination of Equations (12) and (13); thus, it represents a consistent over-constraint that can be eliminated. However, if the right-hand side of Equation (14) is changed to zero, the constraint becomes an inconsistent over-constraint, since no values of , , and can simultaneously satisfy all three equations.

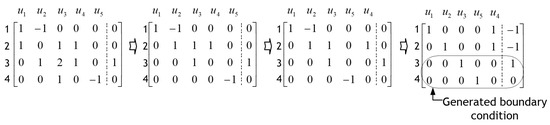

Figure 3a shows the results obtained after applying Gaussian elimination to the augmented matrix , constructed from Equations (12)–(14). Since all the terms in the last row are zero, this row represents a consistent over-constraint that can be removed. Consequently, the constraints given in Equations (12)–(14) can be reduced to the following two independent constraint equations:

Figure 3.

Gauss elimination of constraint equations: (a) consistent over-constraint; (b) inconsistent over-constraint.

Figure 3b shows the same procedure applied to the case where the right-hand side of Equation (14) is zero. In this case, the constraint equations produce an inconsistent over-constraint, since no values of , , and satisfy the last row .

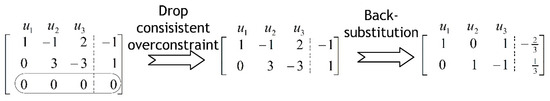

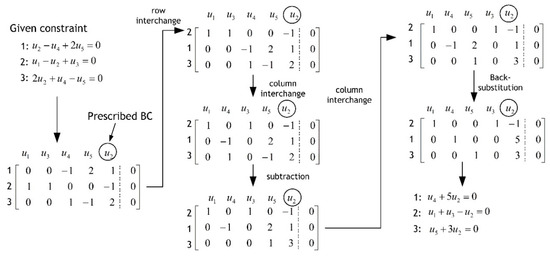

If the constraints in Equations (12)–(14) are handled using the transformation method, a slave–master DOF relationship of the form of Equation (4) can be derived by performing back substitution on the upper-triangular matrix obtained after eliminating the over-constraint. Figure 4 illustrates this procedure. The constraints of Equations (12)–(14) in the final matrix form are transformed into the following equations, for which the transformation method can be easily applied.

Figure 4.

Back substitution of constraint equations.

For the general application, both row and column pivoting should be performed simultaneously, since a row pivot may become zero during Gaussian elimination. Moreover, because the constraint matrix C consists only of the DOFs involved in the constraint equations, rather than the entire set of DOFs, the computational efficiency is significantly improved. The approach described above enables the over-constraint problem and the selection of slave DOFs in the transformation method to be handled efficiently. However, a slight modification of the algorithm is required when boundary conditions—also referred to as single-point constraints—are considered.

The first issue arises when a boundary condition explicitly involves a prescribed DOF in the constraint equation. In general, nonzero boundary conditions appear during nonlinear analyses performed using displacement-control or arc-length methods [10,11,12]. Since the prescribed value of the corresponding DOF varies at each increment, such a boundary condition is regarded as a load condition rather than a single-point constraint. This issue is resolved by placing the DOF with the prescribed boundary condition in a subordinate column when constructing the augmented matrix , and by omitting column pivoting for that DOF. Figure 5 illustrates the application of the proposed algorithm for the case where a prescribed boundary condition is imposed on . It can be seen that is placed in a subordinate column before the algorithm is executed.

Figure 5.

Constraint related to DOF imposed with the boundary condition.

The second issue related to boundary conditions occurs when the constraints are imposed solely on DOFs that are already subjected to boundary conditions. In this case, the situation can be recognized as an over-constraint problem. Constraint equations exhibiting such conditions can be handled during the over-constraint detection stage, prior to Gaussian elimination, by placing the corresponding DOFs in subordinate columns when constructing the matrix A.

The third issue concerning boundary conditions arises from the fact that new boundary conditions can be generated during the execution of the algorithm. In this paper, such boundary conditions are referred to as “generated boundary conditions,” to distinguish them from prescribed ones. For example, consider a DOF that is subjected to a boundary condition. If a constraint equation is imposed, DOF implicitly becomes subjected to the boundary condition. If an external load is explicitly applied to , this constitutes a modeling error; otherwise, it simply represents a normal constraint in which the reaction load corresponding to the support at is computed. Figure 6 illustrates a more complex case in which the generated boundary conditions are handled. As shown, boundary conditions are generated for and , meaning that the values of these DOFs are implicitly determined to satisfy the given constraints. Because loads cannot be applied to DOFs that are subjected to boundary conditions, such cases result in inconsistent boundary conditions when external loads are present at these DOFs.

Figure 6.

Generated boundary condition.

Since generated boundary conditions may exist, their presence should be checked until the back-substitution stage, even when applying the Lagrange multiplier or penalty method.

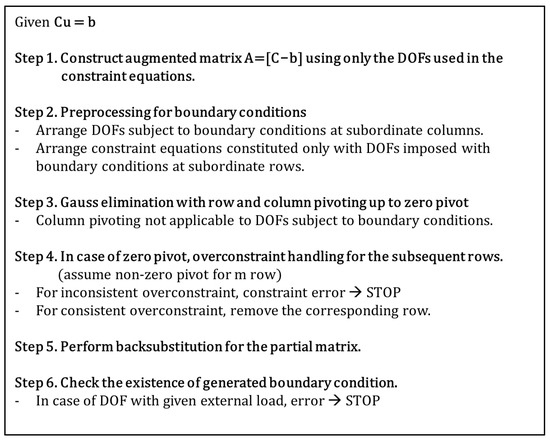

Figure 7 summarizes the algorithm proposed in this study. Step 1 constructs the augmented matrix , where only the DOFs involved in the constraint equations are included. Step 2 corresponds to the preprocessing of prescribed boundary conditions. Step 3 performs triangularization using Gaussian elimination. Step 4 identifies over-constraints in the rows that appear after the zero-pivot row detected in Step 3. Step 5 performs back substitution. Step 6 checks for generated boundary conditions. If a combination of the transformation, Lagrange multiplier, and penalty methods is adopted, row indices can be assigned to selectively apply each method to the matrix obtained at the final stage.

Figure 7.

Gauss elimination-based algorithm for automatic detection and resolution of over-constraints and automatic selection of slave DOFs.

The algorithm presented in Figure 7 should be implemented during the modeling preprocessing stage, prior to the analysis. In cases where constraints are introduced during the analysis, such as in contact problems, the algorithm should be executed before the assembly and solution of the system matrix. Because the size of the constraint matrix C in the algorithm is much smaller than that of the global system matrix, the additional computational cost introduced by the algorithm is negligible.

2.3. Illustrative Example

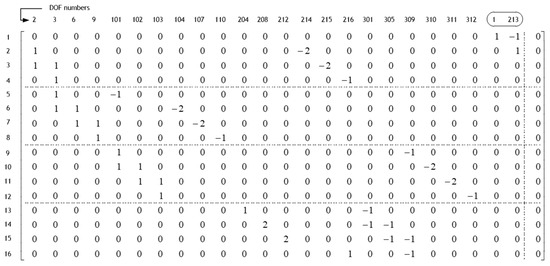

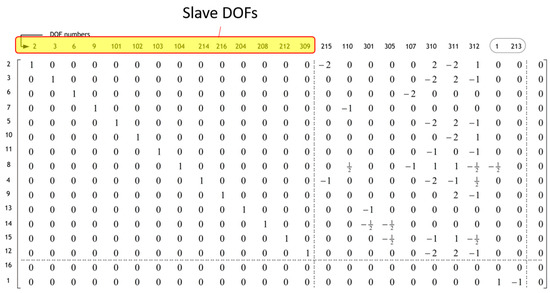

The proposed algorithm is applied to a typical over-constraint problem illustrated in Figure 8. The problem involves 16 constraint equations arising from four line-to-line constraints. Among the DOFs included in these constraint equations, and are subjected to zero boundary conditions. Figure 9 shows the augmented matrix after Step 2 of the proposed algorithm. The results obtained by implementing the algorithm are summarized in Figure 10. Over-constraints are observed in rows 15 and 16, corresponding to the 16th and first constraint equations, respectively, and these are consistent over-constraints.

Figure 8.

Illustrative example: Gauss elimination-based algorithm.

Figure 9.

Augmented matrix after Step 2: Gauss elimination-based algorithm.

Figure 10.

Augmented matrix after completion: Gauss elimination-based algorithm.

3. Algorithm for Large-Scale Models with Complex Constraints

The Gaussian elimination-based algorithm presented in Section 2 can be effectively applied when the constraints are not overly complex. However, in large-scale models with numerous and intricate constraint conditions, the computational cost becomes significant, requiring consideration of the sparsity of the constraint matrix. To address this issue, two enhanced approaches are proposed. First, an improved method that applies the Gaussian elimination-based algorithm to the constraint matrix divided into independent block units is introduced. Second, a new algorithm employing sparse QR factorization is proposed.

3.1. Block-Wise Gauss Elimination-Based Algorithm

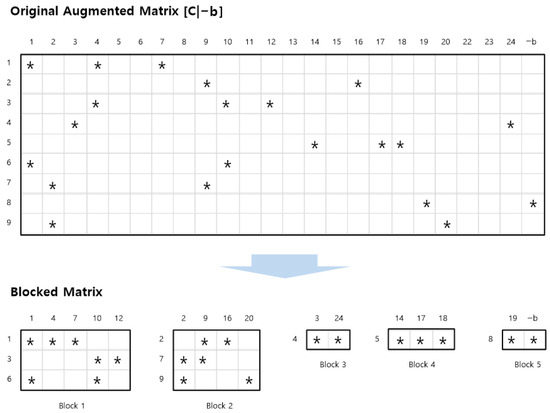

A simple enhancement of the Gaussian elimination-based algorithm for large-scale problems can be achieved by partitioning the constraint matrix into independent block units. As shown in Figure 11, the original constraint equation (i.e., the augmented matrix) can be divided into smaller matrix blocks based on connectivity. In this example, there are 24 degrees of freedom and nine constraints, which are divided into five independent blocks.

Figure 11.

Independent matrix block for block-wise Gauss elimination-based algorithm. Asterisks (*) indicate nonzero entries in the augmented matrix.

This approach allows the Gaussian elimination-based algorithm to be applied to each block separately. Each submatrix block is treated as a dense matrix, enabling efficient computation even when the overall constraint matrix is large, provided that the constraint relationships within each block are not excessively complex. However, determining an efficient method for partitioning the matrix into sub-blocks remains a challenge, and if the size of a single sub-block becomes too large, computational efficiency is significantly reduced.

3.2. Q-Less Sparse QR Factorization Algorithm

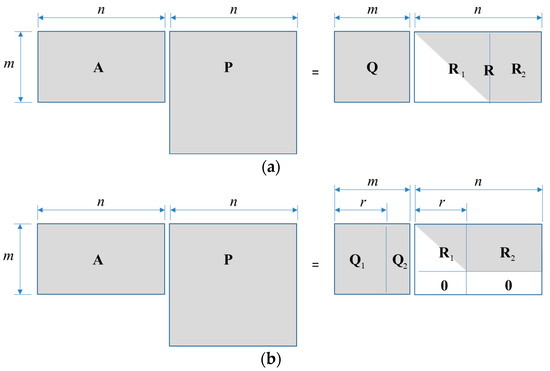

Instead of using the Gaussian elimination method, a sparse QR factorization approach is proposed. QR factorization is an essential matrix decomposition technique in linear algebra, widely used in solving linear systems, least-squares problems, and singular value decomposition (SVD) [13]. For a matrix A, the column-pivoted QR factorization is written as

where P is a permutation matrix, Q is an orthogonal matrix, and R is an upper triangular matrix. QR factorization can be applied to non-square matrices, including the determined constraint matrices that arise in FE constraint elimination. Figure 12 illustrates the conceptual forms of QR factorization for full-rank and rank-deficient under-determined systems.

Figure 12.

Schematic drawing of QR factorization for an under-determined system: (a) full-rank matrix; (b) rank-deficient matrix. Matrix blocks A, P, Q, Q1, Q2, R1, and R2 correspond to those defined in the text; shading is used only for visual grouping.

Although the proposed approach does not follow the Q-less QR factorization technique used for overdetermined systems, the need to avoid explicitly forming the Q matrix is conceptually related to the motivation discussed in [14]. Accordingly, the constraint Equation (3) can be rewritten as follows:

Here, the subscript f denotes free (or forced) DOFs, and p represents prescribed DOFs. The vector can be partitioned into slave DOFs and non-slave free DOFs . Applying QR factorization to ,

Using the orthogonality of , the transformed constraint equation becomes

If is full rank (i.e., no over-constraints exist), R is partitioned as , and the constraint equation reduces to

This has the same form as Equation (4), meaning no redundant constraints exist. If is rank-deficient (i.e., there exist over-constraints), the QR factorization becomes

and the rows corresponding to the zero block identify redundant or inconsistent constraints. For consistent redundancy, the transformed terms involving and vanish, leading to

The quantities

are obtained directly through the QR solver’s “solve” operation, without explicitly forming Q. The detection of inconsistent constraints is performed by checking whether the rows in

vanish after rank reduction.

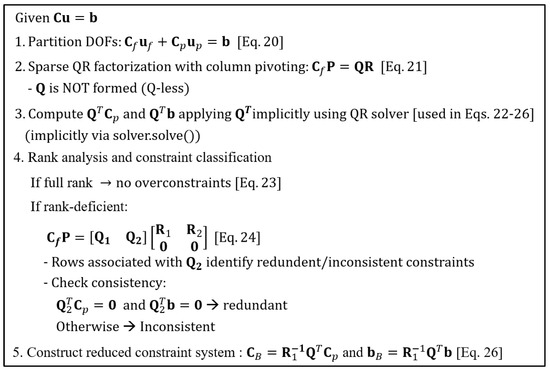

For the QR factorization of dense matrices, solvers provided by LAPACK can be employed [15]. In contrast, developing efficient QR factorization solvers for sparse matrices remains a challenging problem in computational linear algebra and computer science. Publicly available sparse QR solvers include those implemented in Intel oneAPI MKL [16], SuiteSparseQR [17], and Eigen’s SparseQR [18]. Among these, the sparse QR solver in Intel oneAPI MKL is limited to overdetermined systems, making it unsuitable for the present study. In this study, Eigen3’s SparseQR solver was adopted. It employs the same algorithm as the multi-threaded, parallel SuiteSparseQR solver but is easier to use, albeit without parallel-processing support. For these reasons, Eigen’s SparseQR solver was selected. Figure 13 presents a step-by-step summary of the proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm. To improve readability and emphasize practical applicability, the detailed algebraic derivation has been condensed accordingly.

Figure 13.

Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm.

The novelty of the proposed approach is that it applies a Q-less sparse QR factorization to an under-determined constraint system. Conventional sparse QR methods are developed for over-determined least-squares problems, where the orthogonal matrix Q is omitted primarily to reduce memory usage. In contrast, the present constraint-elimination problem is inherently under-determined, and forming Q would immediately result in a dense matrix, eliminating sparsity and greatly increasing computational cost. Therefore, the Q-less formulation is not only an efficiency consideration but a necessity for preserving sparsity while enabling stable rank detection and the identification of redundant constraints.

Both the block-wise Gauss elimination-based algorithm and the Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm require a pivot tolerance to determine numerical rank deficiency, but their sensitivity to small pivots differs substantially. In the block-wise Gauss elimination-based algorithm, the largest entry in each row is selected as the pivot, and rows with |pivot| ≤ 10−5 are treated as numerically dependent and moved to the bottom of the block. However, small but nonzero pivots directly affect the elimination process because the multipliers A(i,k)/A(k,k) grow large when A(k,k) is close to zero. This may amplify roundoff errors, increase fill-in, or even lead to numerical breakdown.

In contrast, the Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm is based on orthogonal transformations whose numerical stability is independent of pivot scaling. The pivot threshold affects only the rank-decision logic. Eigen’s default threshold can fall below 10−10 for matrices of size 104–105, which is insufficient to detect near-dependent rows. For this reason, we adopt τ = 10−5, which provides a practical compromise between accurate rank detection and numerical stability for the constraint matrices used in this study.

3.3. Comparison of Algorithms in Large-Scale Analysis Models

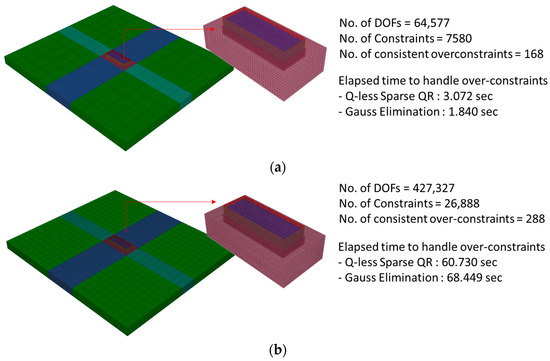

This section compares the performance of the block-wise Gauss elimination-based algorithm and the Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm using a large-scale fluid–structure–soil interaction (FSSI) system. The computational model consists of near-field and far-field soil regions represented by solid elements, a storage tank represented by shell elements, and an internal fluid domain formulated using acoustic elements. Constraint equations arise at several coupling interfaces, including those between the near-field and far-field regions, between the tank wall and the near-field soil, and between the tank wall and the fluid domain. At the fluid–structure interface, although the fluid domain is described in terms of pressure degrees of freedom, an equivalent normal displacement degree of freedom is introduced on the fluid side to ensure kinematic compatibility with the structural wall. These multiple coupling interfaces generate a large number of interdependent constraint equations, resulting in a highly complex constraint system. Additional details of the FSSI formulation, including both conformal and non-conformal coupling schemes, are provided in Appendix A, and the present analysis adopts the non-conformal approach.

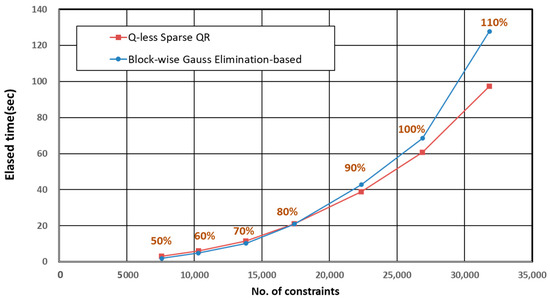

To systematically evaluate the scalability and efficiency of the proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization method, a mesh-refinement study was conducted using the FSSI model. The geometric configuration of the near-field, far-field, tank, and fluid domains was kept constant, while the mesh refinement level was scaled from 50% to 110%. Here, 100% corresponds to the reference mesh used in the original FSSI analysis, whereas 50–90% represent coarser discretizations and 110% denotes an additional finer mesh used only for performance assessment. As the mesh is refined, the number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) and constraint equations increases substantially, leading to a progressively larger and more redundant constraint matrix. Figure 14a,b illustrate the two representative mesh densities—50% (coarse) and 100% (reference fine mesh)—highlighting how mesh refinement affects the size of the coupled system. For each mesh configuration, both the block-wise Gauss elimination method and the Q-less sparse QR factorization method were executed three times, and the average computation times are summarized in Table 1. All computations were performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-14900K CPU @ 3.20 GHz and 128 GB RAM.

Figure 14.

FSSI analysis model used in the mesh-refinement study: (a) 50% mesh (coarse) and (b) 100% mesh (fine).

Table 1.

Summary of DOFs, numbers of constraints, consistent over-constraints, and elapsed computation times for the block-wise Gauss elimination and Q-less sparse QR methods, evaluated at mesh densities ranging from 50% (coarse) to 110% (fine).

Across the different mesh densities, the relative performance of the two algorithms varies systematically. For coarse meshes (50–60%), the block-wise Gauss elimination method is faster because the constraint matrix is smaller and fill-in remains limited. As the mesh becomes moderately refined (70–80%), the performance gap between the two methods narrows, and the computation times become comparable. For fine meshes (90–110%), however, the Q-less sparse QR factorization exhibits a clear advantage. As both the matrix size and the number of redundant constraints grow, SparseQR achieves significantly shorter computation times, particularly at the 100% and 110% mesh refinement levels. These trends are visualized in Figure 15, which plots the elapsed computation time against the number of constraints for each mesh level. The block-wise Gauss elimination method shows near-linear scaling in the coarse-mesh regime but deteriorates rapidly once the constraint matrix becomes larger and more redundant. In contrast, the Q-less sparse QR factorization maintains favorable scaling behavior throughout the refinement range, demonstrating markedly better performance for large systems. These results indicate that while Gauss elimination may be efficient for small or moderately sized constraint matrices, the Q-less sparse QR algorithm provides superior scalability and numerical robustness for the large, highly redundant constraint systems encountered in realistic FSSI problems.

Figure 15.

Computation time versus number of constraints for the block-wise Gauss elimination and Q-less sparse QR algorithms under mesh refinement (50–110%).

Parallel processing was not employed in this study, as no Gauss elimination solver for non-square matrices currently supports parallel computation. However, since SuiteSparseQR [17] provides a parallel implementation of sparse QR factorization, applying it to the proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm is expected to yield further improvements in computational efficiency.

It should be emphasized that this remark is intended only as a potential direction for future enhancement. Parallel Gauss elimination for non-square constraint matrices is not available, and incorporating the parallel version of SuiteSparseQR into the present solver framework would require substantial restructuring and recomputation of the entire FSSI example. Therefore, no parallel-performance test is included in this study, and the discussion of parallelization is presented as a possible extension rather than an experimentally validated result.

It is worth noting that commercial finite element solvers such as Abaqus and ANSYS do not provide an explicit numerical algorithm for resolving redundant or inconsistent constraint equations. These solvers typically issue warning messages when an over-constraint is detected and expect users to modify the model manually. Therefore, a direct algorithmic comparison with commercial codes is not feasible, because no reference numerical solution is available for such systems.

It should be noted that an inconsistent constraint system does not possess a solution, and therefore, the role of the proposed method in such cases is limited to detecting inconsistency rather than producing a reduced, solvable constraint set. Because physically meaningful engineering models such as the FSSI system necessarily employ compatible coupling conditions, inconsistent constraint configurations do not arise in practice. For this reason, the demonstration of inconsistent cases is restricted to theoretical examples, whereas the FSSI example illustrates the behavior of the algorithm under large-scale but consistent over-constraints.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we addressed the challenge of over-constraints in finite element models with complex constraint relationships by proposing a Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm. Traditional methods—such as the transformation method, Lagrange multiplier method, and penalty method—often suffer from small or zero pivot values, which can lead to non-convergence or slow convergence of solutions. Furthermore, the reuse of slave DOFs across multiple constraint equations complicates the modeling process.

The algorithm previously proposed by Cho [5] was reviewed, highlighting its effectiveness for relatively simple systems but also its computational limitations when applied to large-scale models.

To overcome these limitations, we developed a new algorithm that exploits the sparsity of the constraint matrix and performs sparse QR factorization without explicitly forming the dense Q matrix. This approach significantly enhances computational efficiency and reduces memory usage.

The proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm reformulates the constraint equation to separate forced and prescribed DOFs. By applying QR factorization to the constraint matrix and leveraging the orthogonality property of Q, the algorithm effectively resolves over-constraint conditions without generating Q explicitly. It also distinguishes between consistent and inconsistent over-constraints, thereby ensuring accurate and stable solutions.

Comparative analyses between the block-wise Gauss elimination-based and Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithms demonstrated that the latter performs more efficiently in large-scale problems involving numerous and complex constraint relationships. When the number of constraints and over-constraint conditions increases, the proposed algorithm outperforms the block-wise Gauss elimination-based approach in both computation time and overall efficiency. Although parallel processing was not employed in this study, integrating a parallel implementation such as SuiteSparseQR [15] is expected to further accelerate computation and enhance scalability.

In conclusion, the proposed Q-less sparse QR factorization algorithm provides a robust and efficient framework for handling over-constraints in finite element models, particularly for large-scale and highly constrained systems. Future research will focus on incorporating parallel computing capabilities and extending the algorithm to multiphysics and nonlinear analysis domains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-R.C. and J.H.L.; methodology, J.-R.C. and K.C.; software, J.-R.C.; validation, J.-R.C., K.C., and H.Y.; formal analysis, J.-R.C.; investigation, J.-R.C. and H.Y.; resources, J.-R.C. and D.S.R.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-R.C.; writing—review and editing, D.S.R. and J.H.L.; visualization, J.-R.C.; supervision, J.H.L.; project administration, D.S.R.; funding acquisition, D.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Korea Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (MCEE) as “Technology development project to optimize planning, operation, and maintenance of urban flood control facilities” (RS-2024-00397821).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology (KICT) for providing computational resources and technical support. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI, model release November 2025) to improve the language and readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOF | Degree of Freedom |

| FE | Finite Element |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FSSI | Fluid–Structure–Soil Interaction |

| FSI | Fluid–Structure Interaction |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| MKL | Math Kernel Library |

| QR | Orthogonal–Triangular (QR) Factorization |

| LU | Lower–Upper (LU) Factorization |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| CSR | Compressed Sparse Row |

| KICT | Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology |

| MOE | Ministry of Environment (Republic of Korea) |

Appendix A. Formulation of the FSSI Problem

The formulation of the fluid–structure–soil interaction (FSSI) problem can be categorized into two coupling schemes: conformal and non-conformal. Section A.1 describes the conformal coupling formulation, where nodal compatibility is directly enforced at the interface, while Section A.2 presents the non-conformal coupling formulation, which introduces constraint equations to ensure displacement and traction continuity between non-matching meshes.

Appendix A.1. Conformal Coupling Formulation

The soil–structure interaction (SSI) analysis is formulated by applying the domain reduction method (DRM) proposed by [19] as follows:

Here, M, C, and K denote the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively; is the external load vector; and is the effective load induced by ground motion. The subscripts i, b, and e refer to the interior of the near-field, the boundary, and the interior of the far-field, respectively. The superscripts and represent the near-field and far-field domains. and denote the absolute displacements in the near-field, while we represents the relative motion with respect to the free-field displacement in the far-field.

The governing equations of the fluid–structure interaction (FSI) system are expressed as follows when the fluid domain exists inside the near-field, and no external forces act within the fluid domain as expressed in [7]:

where is the pressure degree of freedom.

By applying the interface equilibrium condition , which ensures that the interaction forces at the coupling boundary are equal and opposite, the governing equation for the coupled FSSI system can be expressed as follows:

Appendix A.2. Non-Conformal Coupling Formulation

In practical applications, modeling a complex FSSI system using a conformal mesh is often difficult. In such cases, a nonconformal mesh can be used. The FSSI system corresponding to Equation (A1) can be expressed for an unaligned mesh as follows, subject to the constraint condition defined in Equation (A5):

where the compatibility between the near-field and far-field domains is enforced by the following constraint equation:

Here, represents the constraint matrix that enforces compatibility between the near-field and far-field domains, which are modeled independently.

In the FSI system, the same concept can be applied as shown in [20] as follows:

Here, denotes the normal displacement of the structure defined at the fluid–structure interface, which satisfies the following constraint condition.

Here, represents the constraint matrix that enforces compatibility between the structural displacement and the equivalent normal displacement defined on the fluid side at the fluid–structure interface. This constraint, in conjunction with S, ensures consistent coupling between the solid and fluid domains by linking the structure’s boundary motion to the corresponding normal motion of the acoustic fluid field.

By applying the condition , the governing equation for the coupled FSSI system can be derived accordingly.

References

- Abaqus, Inc. Abaqus Analysis User’s Manual; Version 6.7; Abaqus, Inc.: Providence, RI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boulbes, R.J. Troubleshooting Finite-Element Modeling with Abaqus; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS, Inc. Release 11.0 Documentation for ANSYS—Multibody Analysis Guide; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ADINA R&D, Inc. Theory and Modeling Guide, ADINA System 8.3; ADINA R&D, Inc.: Watertown, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.-R. Object-Oriented Finite Element Framework Using Hybrid Programming. Ph.D. Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS, Inc. ANSYS Release 18.2. Available online: https://www.ansys.com (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- Cook, R.D.; Malkus, D.S.; Plesha, M.E.; Witt, R.J. Concepts and Applications of Finite Element Analysis, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pękal, M.; Frączek, J. Comparison of selected formulations for multibody system dynamics with redundant constraints. Arch. Mech. Eng. 2016, 63, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pękal, M.; Wojtyra, M. Constraint-matrix-based method for reaction and driving forces uniqueness analysis in overconstrained or overactuated multibody systems. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 188, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belytschko, T.; Liu, W.K.; Moran, B. Nonlinear Finite Elements for Continua and Structures; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crisfield, M.A. Non-Linear Finite Element Analysis of Solids and Structures; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Riks, E. An incremental approach to the solution of snapping and buckling problems. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1979, 15, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A. Direct Methods for Sparse Linear Systems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Computer Science. Sparse Least Squares and Q-Less QR. Available online: https://www.cs.cornell.edu/~bindel/class/cs4220-s16/lec/2016-02-29-notes.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Anderson, E.; Bai, Z.; Bischof, C.; Blackford, L.S.; Demmel, J.; Dongarra, J.; Croz, J.D.; Greenbaum, A.; Hammarling, S.; McKenney, A.; et al. LAPACK Users’ Guide, 3rd ed.; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Intel Corporation. Intel Math Kernel Library. Available online: https://software.intel.com/content/www/us/en/develop/tools/oneapi/components/onemkl.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Davis, T.A. SuiteSparseQR: Multifunctional multithreaded rank-revealing sparse QR factorization. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2011, 38, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guennebaud, G.; Jacob, B.; Jolivet, R.; Falcou, J.; Gosmann, J.; Keck, M.; Iglberger, K.; Fistinig, M.; Thom, A.; Lelarge, M.; et al. Eigen v3. Available online: http://eigen.tuxfamily.org (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bielak, J.; Loukakis, K.; Hisada, Y.; Yoshimura, C. Domain reduction method for three-dimensional earthquake modeling in localized regions, Part I: Theory. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2003, 93, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-R.; Lee, J.-H.; Cho, K.; Yoon, H. Acoustic interface element on nonconformal finite element mesh for fluid–structure interaction problem. EESK J. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 27, 163–170. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).