Abstract

The global elderly population continues to increase, and the demand for leisure programs that support active aging is growing. In particular, group-based outdoor activities for seniors are often conducted in large public areas such as parks, ecological gardens, and cultural sites. As many of these spaces are now being integrated into smart city infrastructures equipped with IoT-based sensing and location-aware services, opportunities for data-driven safety support are expanding. However, in these wide and crowded environments, a small number of social workers are responsible for supervising many elderly participants, which creates monitoring blind spots. In addition, age-related cognitive and physical decline increases the risk of wandering and sudden health deterioration, making timely detection and response difficult. To address this problem, we propose a safety monitoring system for seniors. The system is based on a cloud platform that collects location data from GPS modules and motion information from embedded sensors on mobile devices. It provides real-time tracking of each participant and periodically evaluates their safety state. When abnormal conditions are detected, alerts are delivered to both social workers and the corresponding senior. A prototype implementation, consisting of a cloud server and mobile applications for social workers and elderly users, has been developed. The system is evaluated through a field test conducted on a university campus.

Keywords:

social welfare; safety; monitoring; health; location-based system; mobile device; large-scale area; smart city 1. Introduction

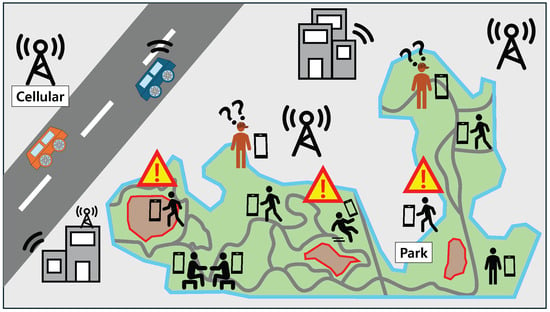

Currently, the proportion of the elderly population and average life expectancy are continuously increasing worldwide [1,2]. Accordingly, interest in the leisure life and leisure activities of the elderly is also increasing [3]. In response to these concerns, leisure welfare facilities and programs for seniors are expanding in many parts of the world, and leisure programs, including outdoor activities, travel, and tourism, are becoming more active [4]. Furthermore, many outdoor public areas used for such programs are now being integrated into smart city infrastructures equipped with the IoT (Internet of Things) connectivity and location-based systems [5]. These smart environments provide opportunities for data-driven safety support but also introduce challenges in ensuring continuous monitoring across large-scale outdoor areas, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Safe outdoor activity in a large-scale smart city environment.

In such outdoor environments, a small number of social workers as managers are often responsible for supervising a relatively large group of elderly individuals. During activities, older adults may move in small subgroups or become separated, leading to numerous blind spots in which they are no longer within a social worker’s direct line of sight. If an elderly individual wanders outside the designated area or experiences a sudden health-related incident, prompt intervention is required. However, the social workers frequently face challenges in detecting these situations in real time and responding quickly.

In addition, cognitive and physical decline that comes with age increases vulnerability to risks such as disorientation and acute health problems [6]. For example, older adults with mild dementia may unconsciously stray or become lost while moving, believing things are normal, often without even realizing they are lost. Unlike a child traveling alone, this characteristic makes it difficult for bystanders or caregivers to immediately recognize the need for assistance, potentially delaying response in the event of a dangerous situation.

To address these issues, various methods have been studied for years to determine whether older people are leaving the community and their health state [7,8,9,10]. These studies mainly employ GPS-based location data, wireless communication technologies such as Bluetooth and LoRa (Long Range), and AI (Artificial Intelligence)-based analysis. The Bluetooth-based approach periodically exchanges GPS data between two devices via Bluetooth communication, allowing their locations to be identified without the need for a server [7]. However, since Bluetooth is a short-range communication technology, the deviation-detection range is dependent on its communication distance. In contrast, the LoRa-based approach supports long-range communication, which alleviates the distance limitations of Bluetooth-based methods [8]. However, this approach requires a dedicated terminal device and the deployment of LoRa network infrastructure, resulting in construction and operational costs. Meanwhile, the AI-based approach can accurately assess movement patterns and health state using long-term individual mobility data collected within a specific area [9]. However, because the data must be recollected when the activity area changes, this approach is unsuitable for situations where the activity area varies, such as outdoor programs at social-welfare facilities. Additionally, a sensor-based approach has been proposed to detect abnormal health conditions, such as falls, using a custom-built wearable device [10]. Although this method may be effective for monitoring an individual’s physical state, it is not enough to support location-based event detection. As a result, spatial risks such as boundary deviation or unintended entry into restricted areas cannot be identified. In summary, such approaches depend on constrained communication ranges, dedicated network infrastructures, region-specific learning models, or device-centric sensing capabilities, which limits their practicality in large-scale outdoor activity programs with frequently changing activity areas. These limitations make existing schemes is not suitable for scenarios where monitoring should be performed immediately, without installing additional hardware, configuring custom networks, or enforcing device usage by seniors.

To address these issues and effectively monitor the safety of the elderly in large-scale outdoor environments, this paper proposes a senior safety monitoring system (SrSMS). This system utilizes mobile devices such as smartphones, which are commonly used by older adults, eliminating the need for additional equipment. The smart mobile device can continuously collect location and health information from the elderly through built-in sensors such as GPS, accelerometer, gyroscope, etc. Furthermore, the mobile device can access the Internet anytime and anywhere via its cellular communication module and allows real-time transmission of collected data to the cloud. The collected GPS data is used to determine whether someone is deviating from the activity area, while the accelerometer and gyroscope sensor data are used to detect health abnormalities. To achieve this, this study designs and implements a deviation detection algorithm and a health detection algorithm. Moreover, a prototype is developed based on an off-the-shelf mobile device, and a testbed is built. And then the performance of the proposed system is evaluated through a field test.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 investigates research works related to supporting safe outdoor activities. Section 3 describes the system model, system architecture, and key algorithms of the proposed scheme. Section 4 analyzes the experiments and results to evaluate the performance of the proposed scheme. Finally, Section 5 concludes with conclusions and future research on the proposed scheme.

2. Related Work

In this section, we explore studies related to the detection of deviation and health conditions for safe outdoor activity [7,8,9,10].

First, LTS (Location Tracking System) proposes a system that traces user location based on Bluetooth [7]. To support deviation detection, this LTS system employs a dedicated portable device using an Arduino Uno equipped with GPS and Bluetooth modules. The manager and senior collect GPS data from their mobile device. Then, they exchange their own GPS data with each other via Bluetooth communication. The manager configures the range of deviation detection in the mobile application. Then, in the application of the manager, the distance between the senior and itself is calculated with the GPS data periodically disseminated from the senior’s device. With this, if the senior deviates from the detection range set by the manager, a deviation alert is transmitted to the manager via Bluetooth communication. Accordingly, the LTS system can effectively detect deviation as long as the manager and the senior keep within the Bluetooth communication range. However, the LTS system has to needs an extra device for the deviation detection of elderly persons, but also the practical detection range may be limited to approximately 10 m due to the nature of Bluetooth communication [11,12]. Therefore, although the LTS system enables short-range deviation detection, its dependence on an additional device and the short communication range of Bluetooth significantly limit its applicability in large-scale outdoor environments.

Second, the smart shoe system tracks the location of the elderly using a dedicated device with a Cortex-M3-based embedded board, GPS, an accelerometer, and a LoRa module [8]. The device mounted on smart shoes, designed to detect the elderly’s movement, periodically senses the wearer’s GPS location and then transmits the current location to a server via a LoRa network, which supports long-distance communication. And then the collected location information is relayed to the manager. Meanwhile, LoRa, one of the low-power wide area network (LPWAN) technologies, supports low-energy and long-distance communication [13]. It offers a communication range of several kilometers, which can overcome the coverage limitations of short-range wireless devices [14]. However, unlike cellular networks, LoRa does not rely on a ubiquitously deployed communication infrastructure. Thus, it has to require dedicated equipment, such as LoRa gateways and terminal devices [15]. In other words, the communication with LoRa necessitates the construction of a separate network infrastructure. Consequently, the communication range available to users can vary significantly depending on LoRa gateway deployment. In regions where gateways are sparse or absent, the terminal device may be unable to transmit data reliably. This results in a fundamental limitation in which the smart-shoe system cannot operate properly without the presence of a LoRa network infrastructure.

Third, Wishing-No-Missing (WnM) proposes an AI-based system using a mobile device for the prevention and detection of missing elderly [9]. This WnM system aims to prevent missing persons by analyzing the movement paths of elderly persons and detecting abnormalities from their usual movement patterns. For this, GPS data, location data, is periodically delivered to a server via the mobile device and then stored in a database. Then, it learns the movement patterns of the elderly person for a certain period based on a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based deep learning scheme. Based on learned movement patterns, the WnM system determines that if the elderly person’s movement deviates from the usual route by a certain distance, it is considered a deviation. Furthermore, if no movement is detected for a certain period of time, it sends an alert to the manager, considering the possibility of a health problem or emergency. This system works only with a mobile device and does not require any additional equipment or devices. In addition, through AI-based learning, it determines deviations more precisely by analyzing the elderly person’s habitual movement patterns. However, this scheme has a limitation in that it has to collect the new movement data again for a long time when the activity area changes, since it requires learning long-term movement data for the interest area. So while the WnM system could be effective within our everyday lives, it makes it difficult to apply to situations where visits to social welfare facilities, such as outdoor programs, can be variable.

Fourth, HVSMS (Human Vital Signs Monitoring System) proposes a sensor-based system using a wearable device developed to detect abnormal health conditions [10]. The system measures acceleration through a bio-sensor and processes the data using a microcontroller based on the ATmega328P. When a fall occurs, an alert message is transmitted to a medical center via a GSM module, enabling timely response for emergency situations. In this approach, the accelerometer continuously measures body motion and detects abrupt changes that indicate a fall event. When the microcontroller determines that abnormal movement has occurred, it obtains the user’s location by the GPS module, and then it transmits an alert message to medical personnel via the GSM module. This allows the system to deliver real-time fall detection without requiring server-based processing. However, since the system is designed exclusively for abnormal motion detection, it does not provide additional capabilities such as location-based event detection.

Consequently, while existing studies have proposed various approaches, they are limited in real-time monitoring of the health state of the elderly or deviation detection. Moreover, technical constraints exist, such as limited communication distance, high deployment costs, and dependence on additional equipment. These limitations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of related work.

3. Senior Safety Monitoring System

This section describes the senior safety monitoring system (called SrSMS), which uses GPS data and various sensors embedded on mobile device to monitor the deviation and health state of elderly individuals. The SrSMS consists of the SrSMS cloud, the SrSMS manager device, and the SrSMS senior device.

For safe outdoor activity in a smart city, the SrSMS senior device collects its GPS data and embedded sensory data, and then such data is delivered to the SrSMS cloud. In the SrSMS cloud, with the collected data, the safety of each senior is monitored. If an abnormal state for a senior is detected, the SrSMS cloud alerts the SrSMS manager device with the information. In addition, to detect the safety of each senior, we propose two algorithms for deviation detection and health detection.

This section is organized as follows: Section 3.1 describes the overall SrSMS system model. In Section 3.2, the SrSMS cloud architecture is presented, which is designed to monitor elderly deviation and health conditions. Section 3.3 and Section 3.4 introduce the SrSMS manager and the SrSMS senior device, respectively, both of which exchange data with the SrSMS cloud. Finally, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6 explain the deviation detection algorithm and the health monitoring algorithm used to assess the elderly’s safety during outdoor activity.

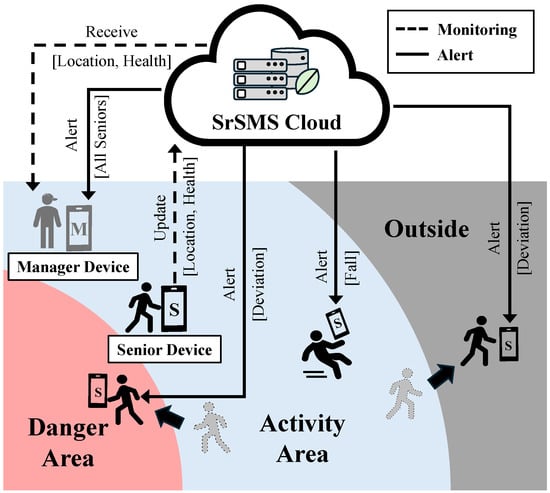

3.1. SrSMS System Model

As shown in Figure 2, the SrSMS system model consists of three components. First, the SrSMS Cloud detects abnormal behavior, such as deviation from safe activity areas, and abnormal health conditions, such as falling, while the elderly individual is active outdoors, and sends alert notifications when necessary. Second, the SrSMS manager device exchanges data in real-time with the SrSMS Cloud and monitors the elderly people. Third, the SrSMS device for the elderly collects location and health data and transmits it to the SrSMS Cloud.

Figure 2.

SrSMS system model.

In the above system, the deviation and health state are detected through the following process. First, to detect the deviation from the activity area, the social worker, as manager, preliminarily divides the elderly person’s active radius into an activity area, a danger area (where entry is restricted due to risk factors), and an outside area. If the elderly person is within the activity area, they are considered to be performing normal activity. If they are within the danger area or outside, the information is immediately transmitted to the SrSMS manager device. Furthermore, if the elderly person is deemed likely to move into the danger area or outside, the GPS data reporting period is shortened to enable SrSMS to make a more rapid assessment.

Next, the abnormal state of health is detected using sensors embedded in the SrSMS senior device. The device periodically measures and saves data, and the collected data is transmitted to the SrSMS cloud. Because it is difficult to determine health abnormalities based on a single measurement, health changes are identified by analyzing data accumulated over a period of time.

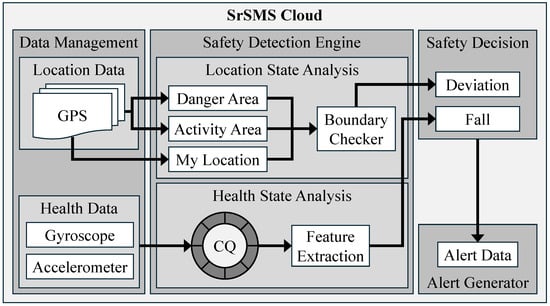

3.2. SrSMS Cloud

Figure 3 describes the system architecture for SrSMS cloud. SrSMS cloud figures out the safety state of seniors based on data from the SrSMS manager device and the SrSMS senior device. It then sends warnings to managers and seniors if abnormal states are detected. This SrSMS cloud is composed of four components: data management, safety detection engine, safety decision, and alert generator.

Figure 3.

Architecture for SrSMS Cloud.

The data management part consists of location data and health data. All data is collected as raw data from the GPS and sensor modules embedded in the manager and senior devices. In the location data element, GPS data is used to represent the senior’s current location and distinguish between two types of areas, an activity area and danger areas, defined by the manager. In the health data element, there are two types of sensory data: gyroscope and accelerometer. The X-, Y-, and Z-axis values of each sensor are collected from the SrSMS senior device. To detect falls, which is one of the health states, this system utilizes a gyroscope and accelerometer as the health data.

The safety detection engine part performs location state analysis and health state analysis based on two types of data delivered from the data management part. At first, the location state analysis element analyzes GPS data from the data management part to detect deviation. The GPS data contains three types of location information: the senior’s current location, and both the activity area and the danger area pre-determined by the manager. Next, the boundary checker element determines whether the senior is within the safe activity area based on a bunch of location information. With this, it can confirm whether the senior has left the activity area or entered a danger area. In other words, the safety state is determined by whether the senior deviates from the activity area. Accordingly, we design a deviation detection algorithm, and this algorithm is described in Section 3.5.

In addition to the location state analysis element, the health state analysis element analyzes the sensory data from the gyroscope and accelerometer to detect a health condition. Gyroscope and accelerometer sensors produce continuous streams of data at very short intervals, and the measured values fluctuate substantially depending on the user’s movements. Therefore, it is difficult to accurately interpret a user’s actual movement based solely on sensor values at a single point in time. In particular, a fall is a complex event that involves a series of rapid changes in motion over a short period of time, from milliseconds to seconds, and includes various stages such as slipping, changes in body tilt, rotation, and impact. Thus, a single value measured from a sensor is insufficient to capture such continuous variations, which significantly makes it difficult to accurately decide a health state. Accordingly, considering such a feature, we organize continuous time series sensor data into certain time windows, manage them using a circular queue (CQ), and employ a method of extracting change-based features from each window. The health detection algorithm developed for this purpose is described in detail in Section 3.6.

The safety decision part comprehensively assesses the safety states of the elderly by using deviation and fall information analyzed in the safety detection engine part. If a deviation or fall is detected, the corresponding information is delivered to the alert generator part.

Finally, the alert generator part delivers appropriate alert data to the manager and the elderly based on the results of the safety decision part. It provides the manager with information on the elderly’s safety condition and alerts the elderly to the occurrence of a dangerous situation.

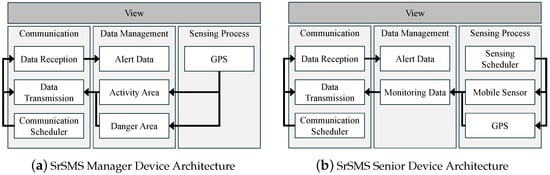

3.3. SrSMS Manager Device

Figure 4a presents the system architecture of SrSMS manager device. The SrSMS manager device delivers the GPS data collected from itself to SrSMS cloud, and then it receives the result determined by SrSMS cloud.

Figure 4.

System Architectures of the SrSMS Manager Device and the SrSMS Senior Device.

For this, the architecture for the SrSMS manager device consists of three components: Sensing Process, Data Management, and Communication. First, the communication part performs communication for data exchange between the SrSMS manager device and the SrSMS cloud. The communication scheduler element is enable to support stable data transmission and reception with the SrSMS cloud. The data transmission element transmits data on GPS-based activity and danger areas, pre-defined by the manager, to the SrSMS cloud. The data reception element receives alert data from the SrSMS cloud and forwards it to the data management element.

Second, the data management part manages data to be transmitted or received from the SrSMS device to the SrSMS cloud. The elements for both an activity area and danger areas are delivered to the SrSMS cloud. These area elements are made of GPS data by the manager. And the alert data element is received from the SrSMS cloud via the data reception element of the communication part. If the alert data is activated, the information would include abnormal states for every senior. That is, it means some seniors are exposed to risk, such as falling, deviating from the activity area, or entering a predefined danger area. Finally, as a result of monitoring, the alert data is displayed on a screen via the view element in the SrSMS manager device.

Third, the sensing process part provides the GPS data, which is the raw data required for processing into data to be transmitted to the SrSMS cloud, to the data management part. The GPS data is generated by the GPS module on a smartphone, as the SrSMS manager device, and then it is used to create the activity area and the danger area.

3.4. SrSMS Senior Device

Figure 4b presents the SrSMS senior device. The SrSMS senior device combines the monitoring data collected by its GPS and own mobile sensors, such as accelerometer, and gyroscope sensor, and then transmits it to the SrSMS cloud. After that, the SrSMS senior device receives the determined result from the SrSMS cloud.

For this, the architecture for the SrSMS senior device consists of three components: Sensing Process, Data Management, and Communication. First, the Communication part exchanges data between the SrSMS cloud and the SrSMS senior device. The Communication Scheduler element creates a data transmission and reception cycle with the SrSMS cloud to support smooth transmission and reception. The Data Transmission element transmits monitoring data collected by the mobile sensor itself to the SrSMS cloud. The Data Reception element receives alert data from the SrSMS cloud and transmits it to the data management part.

Second, the Data Management part manages data transmitted or received from the SrSMS cloud to the SrSMS senior device. The Monitoring Data element is collected by the GPS and mobile sensors and transmitted to the SrSMS cloud by the Data Transmission element of the Communication part. The Alert Data element is transmitted to the SrSMS senior device by the Data Reception element of the Communication part as a result determined in the SrSMS cloud. And the transmitted Alert Data element is displayed in the view on the SrSMS senior device.

Third, the Sensing Process part collects data from GPS and mobile sensors used in the SrSMS senior device and transmits it to the Data Management part as data to be transmitted to the SrSMS cloud. The Sensing Scheduler element creates GPS and mobile sensor collection cycles to support smooth data management of the Data Management part. The mobile sensor element is used to analyze the health state of the senior using data generated by their own accelerometer and gyroscope. And the collected mobile sensors are transmitted to the Data Management part. The GPS element is used to analyze the location status of the senior using data generated by the GPS module. And the collected GPS is transmitted to the Data Management part.

3.5. Deviation Detection Algorithm

This subsection describes the Deviation Detection Algorithm designed to analyze the location state of the senior used in the Location State Analysis of the Safety Detection Engine. Algorithm 1 runs whenever location data is received from the SrSMS device. It uses the location of the senior, the activity area, and danger areas to determine the deviation state. If the location of the senior is outside the activity area or inside the danger area, the device determines that they are in the deviation state.

The SrSMS system is designed to allow multiple danger areas inside a single activity area. This is because if the senior is outside the activity area, it should be determined as a deviation state regardless of the danger area. And, it is considered that there may be multiple danger factors inside the activity area. Therefore, in the algorithm, each activity area and danger area are stored as a one-dimensional array of vertex coordinates, and each danger area is then stored as a two-dimensional array of danger areas. The vertex coordinates are stored in clockwise order, and the end of the array is always the coordinates of the first stored vertex.

In this environment, the Counter-Clockwise (CCW) algorithm is used to determine whether the location of the senior is outside each area [16]. The CCW algorithm determines the orientation of three points by evaluating whether the third point lies to the left, to the right, or on the line formed by connecting the first two points. First, Algorithm 1 connects the two endpoints of the edges that compose each area in a certain direction. Then, it determines on which side of this directed edge the senior’s current position is located. This evaluation is performed for all boundary edges while maintaining the same directional order. If the orientations of all three-point evaluations are consistent, the senior is considered to be inside the area. If at least one orientation differs, the senior is determined to be outside the area. In this way, the deviation state of the senior is determined by the coordinates of the vertices of each area. However, if you calculate the vertex coordinates of all areas, the amount of calculation may increase. Thus, to minimize data operations, the algorithm first determines whether the location of the senior is inside the activity area. And if so, Algorithm 1 checks whether the location of the senior is inside the danger area. Accordingly, if the senior is outside the activity area, there is no need for additional computation. It helps to reduce computational cost.

For this, Algorithm 1 is divided into two steps: an initialization step and a decision step. First, in lines 1 to 12, the initialization step is performed. In line 1, is initialized with ACCURACY_THRESHOLD, which denotes the threshold for GPS positional accuracy (error radius) used for handling unreliable data. ACCURACY_THRESHOLD is determined based on the allowable radius within which the senior’s location can be considered valid for deviation detection. In line 2, , which is information about the SrSMS senior device connected to the server, is retrieved. In line 3, is initialized with the location data of . In line 4, is initialized to the GPS coordinates of , which is the location of the SrSMS senior device. Lines 5 to 10 perform a denoising step to ensure the reliability of the measured GPS data based on its accuracy value. Line 5 retrieves the accuracy (error radius) of the raw GPS data using . If this accuracy value is lower than , the position error is large and the data is considered unreliable. In this case, the algorithm returns an ERROR status and discards the corresponding GPS data. Otherwise, the GPS data is considered valid data. Then, the current position is set to the . In lines 11 to 12, and , which the activity area and danger areas, are retrieved.

| Algorithm 1 Deviation Detection Algorithm |

|

After then, in lines 13 to 33, the decision step is performed. In lines 13 to 20, it figures out whether is inside the . This process starts at index 0, where the coordinates of the first vertex in the are stored, and repeats the following process sequentially until the index just before the last index in the . In line 14, , which is the deviation state, is initialized to false. In lines 15 to 16, the coordinates stored at the -th index of and the next index are stored as and . In lines 17 to 19, it determines whether the three points , , and are connected in a counterclockwise direction when connected in order. If the connection is counterclockwise, it means that the senior is outside the activity area, thus set to true. In lines 21 to 32, if is false, figure out whether is outside . In line 22, is initialized to true. In lines 23 to 31, the following process is repeated sequentially from the first area of to the last area, and from the first vertex of each area to the vertex before the last. In lines 25 to 26, the coordinates stored at the -th vertex and the next vertex in the -th area of are stored as and . In lines 27 to 29, it determines whether the three points , , and are connected in a counterclockwise direction when connected in order. If the connection is counterclockwise, it means that the senior is outside the danger area, thus set to false. In line 33, the deviation is returned and transmitted to the Safety Decision of the Safety Detection Engine.

3.6. Health Detection Algorithm

This section describes an Senior Health Detection Algorithm designed to analyze the health state of the senior, which is used in the Health State Analysis of the Safety Detection Engine.

Algorithm 2 determines the health state of the senior by using the maximum change in the values of the accelerometer and gyroscope sensors. In the case of a fall, the decision is made based on a large gap between values in the data stream continuously collected from the sensors. Accordingly, if the maximum change in the values from the sensors exceeds the threshold, which is enough to aware an impact, the event is first deemed as a fall. After that, if the maximum change is dropped below the threshold, which is sufficient to perceive that there is a tiny movement, such an event is finally decided as a fall. In this way, to decide the maximum change, it demands values measured at consecutive points in time. In other words, if it uses only a value measured at a single point in time, it is difficult to figure out the maximum change. Therefore, in Algorithm 2, the health state is detected using a window-based capturing scheme to utilize a sufficient amount of data acquired from the accelerometer and gyroscope sensors.

| Algorithm 2 Health Detection Algorithm |

|

For this, Algorithm 2 is divided into two steps: an initialization step and a decision step. First, in lines 1 to 7, the initialization step is performed. In lines 1 to 3, initialize the values set in SrSMS. In line 1, is initialized to WINDOW_SIZE, which represents the number of data needed to figure out the maximum change. WINDOW_SIZE is set to the value divided the monitoring cycle by the sensing period. In line 2, is initialized to IMPACT_THRESHOLD, as the threshold to detect an impact. IMPACT_THRESHOLD sets the accelerometer and gyroscope sensor values to appropriate values to represent the impact when an impact is applied to the mobile device. In line 3, is initialized to NO_SIGN_THRESHOLD, which is the threshold to detect a fall. NO_SIGN_THRESHOLD sets the accelerometer and gyroscope sensor values to appropriate values to represent the stationary when the mobile device is stationary. In line 4, is retrieved, which is the information of the SrSMS senior device connected to the server. In line 5, is initialized with the accelerometer and gyroscope sensor values of . In line 6, is initialized with the stream data of . In line 7, the indicating the state of the senior is initialized to SAFE, which means normal state.

After then, in lines 8 to 24, the decision step is performed. In lines 8 to 10, is enqueued into , a circular queue that analyzes health state as much as . The extracts state-specific features based on predefined threshold values through the extractFeature() function. The extractFeature() function sequentially scans the time-ordered entries in and compares them with the corresponding thresholds to identify the features associated with each state. In lines 11 to 15, if is SAFE, figure out the impact. In lines 12 to 14, the maximum change in is calculated, and if the value is greater than , it is determined the impact and the is changed to IMPACT. In lines 16 to 20, if is IMPACT, figure out the fall. In lines 17 to 19, the maximum change in is calculated, and if the value is less than , it is determined the fall and is changed to FALL. In lines 21 to 23 return true if is FALL, otherwise they return false.

4. Empirical Experiment and Performance Evaluation

This section presents the results of empirical experiments conducted to verify the effectiveness of the proposed senior safety monitoring system (called SrSMS). The experiments, conducted under conditions simulating real-world usage, focus on two core functions: deviation detection and health abnormality detection.

Section 4.1 describes the experimental environment for performance evaluation. Section 4.2 describes the experimental scenarios used to conduct the experiments. Section 4.3 describes a preliminary experiment to examine the measurements from the accelerometer and gyroscope sensor inside a mobile device under various conditions. Finally, Section 4.4 describes the experimental results based on the experimental scenario, using actual screens.

4.1. Experimental Environment

To evaluate the performance of proposed system, we conducted the experiment in a large, crowded outdoor space within a university campus. We assume a situation where one manager and two seniors participate outdoor activity program at a university campus. In addition, as a prerequisite, both seniors are located in the manager’s blind spot. In other words, this means that the manager cannot directly check the safety of the two elderly people with the manager’s own eyes.

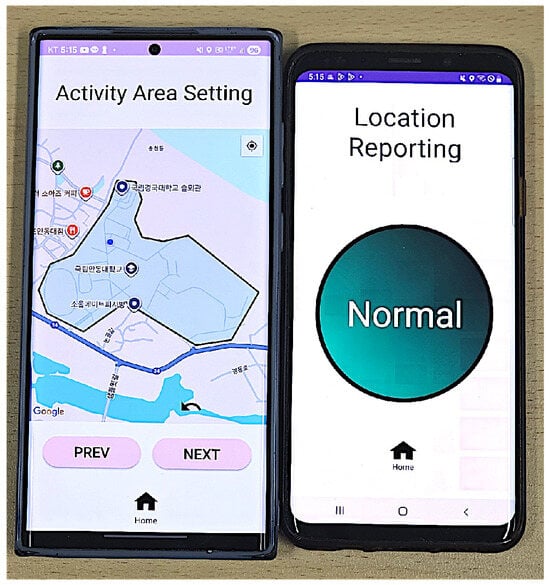

As shown in Figure 5, the SrSMS devices used in this experiment are three different mobile devices based on the Android OS. The SrSMS cloud is implemented using Java Spring Boot, and its sensors include GPS data collected at 1000 ms intervals and accelerometer and gyroscope sensors collected at 100 ms intervals. Details on the experimental environment are presented in Table 2.

Figure 5.

SrSMS Device Used in the Experiments. Note: The map contains Korean place names, which are displayed automatically by the map provider’s regional language setting. These labels indicate actual geographic locations around the experimental site and do not affect the interpretation of the figure.

Table 2.

Experimental environments.

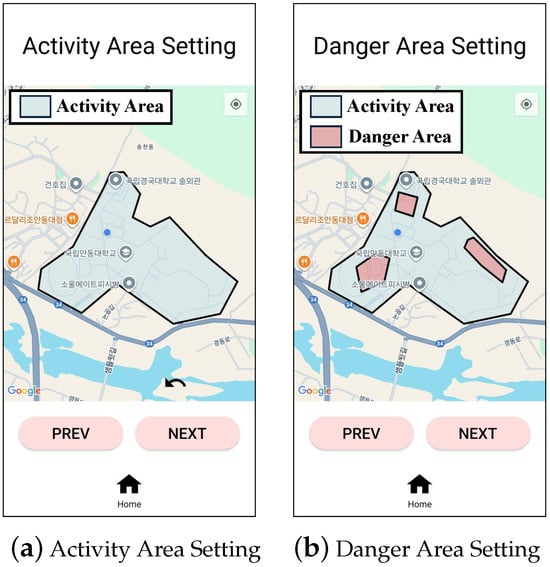

Figure 6 shows that the manager sets one activity area and three danger areas. After that, the experiment focuses on normal activity, location-related, and health-related events. For a location-related event, the experiment is divided into two scenarios: the senior leaving the activity area and entering the danger area. For health-related events, the experiment is divided into two scenarios: a fall is detected, and the senior remains motionless.

Figure 6.

SrSMS Device Screen for Configuring Activity and Danger Area. Note: The map contains Korean place names, which are displayed automatically by the map provider’s regional language setting. These labels indicate actual geographic locations around the experimental site and do not affect the interpretation of the figure.

4.2. Deviation Detection Experiment

4.2.1. Scenario for Deviation Detection

This experiment evaluates the performance of the proposed SrSMS system to detect location-related abnormal states, including leaving the activity area and entering predefined danger areas. A manager defines one activity area and three danger areas in one’s own application. The two seniors then move freely within the campus under the assumption that the manager cannot directly observe them. The experiments are conducted across an outdoor university campus environment with a total area of approximately 791,292 m2, providing a sufficiently large and realistic spatial scope for validating deviation behaviors that may occur during seniors’ outdoor activities.

During the experiments, the GPS module of the SrSMS senior device provides an average positioning accuracy within 5 m, which aligns with the commonly reported outdoor GPS accuracy of cellphones operating under open-sky conditions. The trials are performed on clear days without precipitation, preventing weather-induced degradation of GPS reception and ensuring that environmental factors do not interfere with the deviation detection process. In our system, the deviation detection threshold is empirically set to 20 m. This value is derived from preliminary field tests, where smaller thresholds cause spurious deviations due to inherent GPS coordinate fluctuations, while larger thresholds reduce detection sensitivity. The 20 m configuration provides the most reliable balance between stability and responsiveness under real outdoor conditions. These controlled conditions allow each scenario to reflect realistic outdoor mobility while maintaining consistent measurement reliability across the evaluations.

Three types of deviation scenarios are organized as follows:

- Staying Near Boundary

- The senior stays near the boundary of the activity area without crossing it.

- The system must remain stable, avoiding false deviation alerts despite GPS noise.

- Leaving Activity Area

- A senior gradually walks outside the predefined activity boundary.

- The system must detect boundary crossing based on the GPS trajectory.

- Entering Danger Area

- A senior intentionally approaches and enters one of the danger areas.

- The system must immediately raise a warning once the location intersects the danger area polygon.

4.2.2. Results for Deviation Detection

This subsection presents the results of an experiment conducted to verify the deviation detection functionality of the proposed SrSMS system. This experiment focuses on location-based abnormalities that can occur during outdoor activities in the real world, with two elderly individuals moving out of the manager’s sight. Three deviation detection scenarios are organized. The first is in case of staying near the boundary, where the elderly individual moves or remains near the boundary of the activity area, but does not actually leave the area. This scenario is included to verify that false alerts are not generated due to GPS errors. The second is in case of leaving the activity area, where the elderly individual slowly crosses the activity area boundary and moves outside. This scenario is intended to verify that the SrSMS system accurately detects a deviation and issues alerts at the appropriate time. The third is in case of entering a danger area, where the elderly individual approaches a designated danger area and actually enters the polygon, which is presented as a danger area. In such a case, the proposed system should generate an alert upon entry, without false positives or delays.

In each scenario, the SrSMS senior device is carried along the designated movement route. Once the location data transmitted from the SrSMS senior device is received, the SrSMS cloud determines whether the position remains inside the activity area, crosses the boundary, or enters a danger area. In this experiment, performance is evaluated by checking whether deviation detection succeeds in each scenario, measuring the average latency difference between the actual event and the alert issued by the SrSMS system, and confirming whether any false alerts occur in the near boundary.

It is important to note that the number of repetitions for each scenario is 30. During preliminary test runs, the detection ratio and alert latency values show negligible variation after approximately 25 repetitions, indicating that additional executions do not produce meaningful changes in the performance metrics. Accordingly, 30 repetitions are adopted as the point at which further trials no longer influence the deviation detection performance, while preventing unnecessary experimental burden.

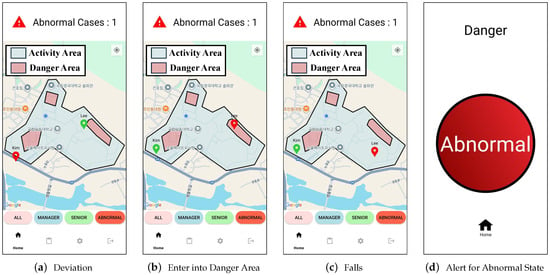

As shown in Table 3, experimental results show that no alerts are generated and no false positives are confirmed in the Staying Near Boundary scenario. This is consistent with the execution screen, where no alert is displayed during boundary-proximity movement (see Figure 7a). In the Leaving Activity Area scenario, all deviations are accurately detected, and the average of alert latency is also low. Thus, all trials are successfully detected with a 100% detection ratio, and the average alert latency remains low at 19.45 ms. The corresponding application screen shows that an alert is issued immediately at the moment the senior crosses the activity boundary (see Figure 8a). Furthermore, in the Entering Danger Area scenario, the SrSMS system confirms location-based deviation detection reliably when an alert is issued as soon as the elderly person crosses into the designated danger area. As a result, it also achieves a 100% detection ratio, and the average latency of issue alerts is 22.39 ms. This behavior is also verified in the execution screen, where an alert appears instantly upon entering the danger area (see Figure 8b).

Table 3.

Experimental results of deviation detection by scenarios.

Figure 7.

Monitoring Screen in Normal State. Note: The map contains Korean place names, which are displayed automatically by the map provider’s regional language setting. These labels indicate actual geographic locations around the experimental site and do not affect the interpretation of the figure.

Figure 8.

Monitoring Screen in Abnormal State. Note: The map contains Korean place names, which are displayed automatically by the map provider’s regional language setting. These labels indicate actual geographic locations around the experimental site and do not affect the interpretation of the figure.

In summary, these results demonstrate that the SrSMS system enables immediate detection and alert upon entering a danger area with no false alerts, where it can effectively distinguish between boundary proximity and actual deviation situations.

4.3. Health Detection Experiment

4.3.1. Scenario for Health Detection

This experiment simulates various scenarios to determine whether accelerometer and gyroscope sensors can detect health abnormalities, and examines how the accelerometer and gyroscope sensors inside mobile devices measure these scenarios. The experiment utilizes 16,200 sensor values collected for preliminary experiments.

In order to reflect realistic fall situations that occur in daily life, the scenarios include multiple fall types rather than a single, uniform pattern. Specifically, falls are induced during walking, sudden collapses occur from a standing posture, falls are triggered while seated, and loss of balance is simulated during posture transitions. These scenarios are selected to ensure that the evaluation covers diverse and practically observable fall conditions rather than an artificial or limited test environment.

With this, a total of 50 fall scenarios are repeated, and it measures detection accuracy and average detection time. The accuracy is calculated as the number of successful detections out of 50 attempts. The average detection time is calculated as the average of the time difference between the moment a person begins to fall and the moment the system detects the fall.

4.3.2. Results for Health Detection

Table 4 presents the results of the fall-detection experiment. A total of 50 fall attempts are performed, and the SrSMS system successfully detects 45 of them, resulting in an accuracy of 90.0%. The detection time is also measured for each trial. The average detection time is 3.6 s, with a minimum of 2.5 s and a maximum of 4.8 s. These results indicate that the SrSMS system identifies fall events with high reliability and detects them within a consistent and practical time range. In addition, we further evaluated the proposed system using core performance metrics commonly applied in classification tasks. The fall detection achieves a precision of 100.0%, a recall of 90.0%, an F1-score of 94.7%, and a false positive rate (FPR) of 0.0%. These additional metrics confirm that the SrSMS system not only detects fall events reliably but also minimizes false alarms while maintaining balanced and robust classification performance.

Table 4.

Experimental results of health detection by scenario.

The number of trials is determined based on empirical observations. During repeated measurements, the detection time and detection accuracy vary in the early stages but begin to stabilize after approximately 45 attempts. Additional trials beyond this point do not produce noticeable differences in either detection time distribution or detection accuracy. Therefore, 50 repetitions are adopted as a saturation point sufficient to confirm stable system behavior and to account for rare detection failures that may occur. This outcome is also reflected in the application screen, where the fall is indicated (see Figure 8c).

Meanwhile, the reason that the detection accuracy of falls does not reach 100% may be because of the structural nature of the Algorithm 2. The health detection algorithm performs that it analyzes a health state using fixed-length time-series windows based on the sensory data, which is collected during a certain period of time. Although such an approach can reliably detect falls based on change patterns within the window, it excludes the short period of time immediately after analysis is completed and before the next window is filled. That is, if a fall occurs during this period, the health event may be included only partially, or not at all. Consequently, the detection failures are attributed to the inherent time break in the window-based processing scheme, rather than to limitations in the algorithm’s decision-making process. In case fall detection is missed, it is necessary to separately check whether the user shows no movement for a certain period of time. Adding a rule that interprets sustained inactivity as an abnormal event could help partially compensate for this limitation.

4.4. Application Execution Screens

The mobile application prototyped for this experiment is based on the Android operating system. It detect deviation state and health state in real time using the embedded sensors and GPS module of the mobile device. And if the location or health state of the senior is abnormal, it notifies the manager of which senior has become abnormal state and where. And it also notifies the senior that they are in an abnormal state.

4.4.1. Activity Area and Danger Area Setting Screen

As shown in Figure 6, the manager must set the activity area and danger areas on the screen where the manager can set the activity area and danger areas. However, regardless of the danger areas, if there is a senior outside the activity area, it has to determine the abnormal state. Thus, it makes no sense to set a danger area outside the activity area. SrSMS is designed to set up danger areas within its activity area to prevent such meaningless area settings. Therefore, the manager first sets the activity area before setting the danger areas. Once the activity area is set, the manager designates the danger area inside the activity area.

Figure 6a shows the activity area setting screen. The Activity Area Setting screen consists of a map centered on the location of the manager, an undo button to undo any mistakes, and two buttons to move between screens. As shown in Figure 6a, only one activity area can be created in the Activity Area Setting screen. When the manager sets an activity area, click on the desired area on the map to set the activity area. When manager click on the desired area will create a vertex. And the vertices are connected by lines in the order they were created to set the area. When the manager sets an activity area, the manager can view the activity area created so far. If the manager accidentally presses a vertex, the manager can press the undo button at the bottom right of the map to go back to before the manager pressed the vertex. When manager press the button will close the application. After the manager sets the activity area and presses the button, the screen will move to the Danger Area Setting screen. If you do not set an activity area, the button will display an error message.

Figure 6b shows the danger area setting screen. The Danger Area Setting screen is similar to the Activity Area Setting screen, but has an additional Confirm button that allows you to confirm a danger area. As shown in Figure 6b, in the case of the Danger Area Setting screen, multiple danger areas can be created inside the activity area. danger areas setting is largely similar activity area setting. However, the danger area must be set inside the activity area. If the manager tries to create a vertex outside the active area, it will not be created and an error message will be displayed. And since multiple danger areas can be set, the manager must confirm the danger area by clicking the confirm button at the bottom right of the map. Once confirmed, the confirmed danger area can no longer be set. After the danger area is confirmed, the manager can click on the map to create a new danger area. When the manager presses the button will return to the Activity Area Settings screen. And all activity area and danger areas set will be deleted. After the manager confirms all danger areas, click the button to move to the Monitoring screen. If no danger areas have been set or there are danger areas that have not been confirmed, the button will display an error message.

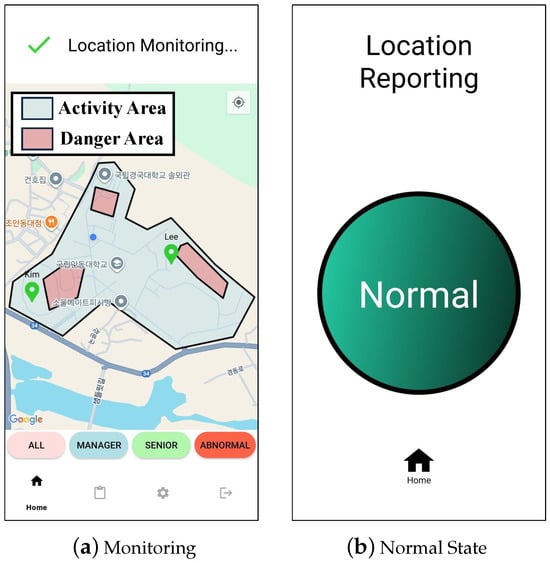

4.4.2. Monitoring Screen in Normal State

Figure 7 shows the monitoring screen in normal state. The Monitoring screen displays different screens depending on the role. The Monitoring screen allows manager to check whether the application is operating and the location and state of the senior, and the senior can check whether the application is operating and their own state. Figure 7a is a monitoring screen in the manager device. The Monitoring screen in the manager application consists of a top text view that shows the monitoring operation state, a map centered on your location, four filtering buttons for quick navigation. Figure 7b is the monitoring screen in the senior application. The Monitoring screen in the senior application consists of a top text view that shows the monitoring operation state and a central circular image that shows senior state. The reason the Monitoring screens for manager and the senior are different is because, unlike manager, the senior may have difficulty operating the device. Therefore, the Monitoring screen for the senior only shows information necessary for the safety of senior, such as location state, health state, and whether the app is working.

As shown in Figure 7a, in the normal state of the senior application, a green check mark and text that show that monitoring is in progress are displayed in the upper text view. And on the map on the Monitoring screen, the name and location of the senior are displayed with a green marker. The information is periodically updated by receiving the location of the senior and state from the SrSMS cloud. When the manager clicks the bottom filtering button, only markers for all, manager, senior, and senior in abnormal state will be displayed on the map.

Figure 7b shows that the device is operating normally and reports periodically the current location of the senior to the SrSMS cloud, indicating that the senior is safe in the activity area.

4.4.3. Monitoring Screen in Abnormal State

Figure 8 shows the monitoring screens in the manager and senior devices, respectively, when a abnormal state is detected. When a abnormal state is detected in the SrSMS cloud, the results are transmitted to the manager and the senior. And the results are displayed in each device.

Figure 8a is a monitoring screen that appears in the manager app when a senior leaves the activity area and deviates. The top of the monitoring screen displays the number of seniors who have left the current activity area, along with a red warning icon. The map also displays the location of the currently senior in a dangerous state with a red marker. This is monitored through periodic location updates, and the normal state is displayed when the senior re-enters the activity area.

Figure 8b shows the monitoring screen when the senior enters the danger area. In this case, the marker will be displayed in red, and the normal state is displayed when the senior leaves the danger area.

Figure 8c shows the monitoring screen when the senior does not move for a certain period of time or a fall is detected. Similarly, the marker for the senior is displayed in red and the normal state is displayed when movement of the senior is detected.

Figure 8d is a monitoring screen when an abnormal state is detected in the senior app. An abnormal state is displayed in the upper center of the screen, and the abnormality is displayed in large letters with a red background so that the senior can recognize the danger at a glance. The normal state is displayed when senior is out of abnormal state. In addition to visual guidance, it also uses the vibration and sound of the smartphone to help the senior quickly recognize their own abnormal state, and to notify the manager and other ordinary people around them who can help.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposes a Senior Safety Monitoring System (SrSMS) to effectively support the safe activities of seniors in large-scale outdoor smart city environments. The proposed system consists of a mobile application for social welfare (or managers) and elderly people (or seniors), running on commonly used mobile devices, and a cloud-based server. The mobile application periodically transmits data from the built-in GPS and various embedded sensors to the SrSMS cloud, which analyzes abnormal states, such as deviation from the activity area and health problems, in real time based on the collected data. When an abnormal state is detected, the system immediately sends warnings to social workers and senior citizens, enabling a rapid response. To effectively assess abnormal states, SrSMS cloud employs deviation detection and health detection algorithms. Furthermore, it provides a senior-friendly user interface to enhance usability and ensure more reliable safety services. To prove the concept of the system, a prototype is implemented and experiments are conducted in an actual university campus environment. The experimental results demonstrate significant performance improvements in terms of practicality and applicability.

In particular, the proposed SrSMS provides several technological advantages over existing GPS-based or mobile sensing systems. First, it integrates real-time deviation detection and on-site health anomaly detection within one framework, enabling simultaneous monitoring of location safety and potential risks. Second, it processes sensor data in the cloud without region-specific learning or additional infrastructure, allowing reliable operation in changing outdoor environments. Finally, it separates ordinary movement changes from dangerous actions, reducing false alerts often seen in existing GPS-based systems. Through these features, SrSMS moves beyond simple location tracking and functions as a scalable safety monitoring platform for seniors.

Future work extends the SrSMS system in three directions. First, it broadens the scope of health-related anomaly detection by addressing various conditions that elderly users may experience outdoors and by developing algorithms to identify them more accurately. Second, it expands the participant group to validate the system under a wider range of outdoor environments and to reduce the influence of random behavioral variations. Third, it conducts comparative evaluations across different geographical scales to examine how the size of the operating area affects GPS stability and deviation detection accuracy. This analysis verifies the scalability of the SrSMS system and determines whether performance differs between small and large operational environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Y.; methodology, T.Y.; software, S.H.; validation, T.Y. and S.H.; formal analysis, T.Y. and S.H.; investigation, T.Y., S.H. and S.P.; resources, T.Y. and S.H.; data curation, T.Y. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Y. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, T.Y., S.H. and S.P.; visualization, T.Y., S.H. and S.P.; supervision, T.Y. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Research Grant of Gyeongkuk National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restrictions imposed by the testbed environment and institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Shen, S.; Zhao, X. Relationship between participation in leisure activities and the maintenance of successful aging in older Chinese adults: A 4-year longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, M.-G.; Choi, C. Perspective on Leisure Sports Participation Among Older Adults in a Super-Aging Society: Focusing on Health Concern, Athletic Passion, Leisure Satisfaction, and Intent to Continue Participating in Leisure Sports. Healthcare 2024, 41, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Shin, W. Impact of Outdoor Recreation on Quality of Life in Older Adults: Focusing on Cheongju City. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2024, 24, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, J.; Liu, N. Relationship between specific leisure activities and successful aging among older adults. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2022, 21, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Location-aware smart health monitoring system for elderly safety in smart city environments. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 45123–45135. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.; Kim, H. Effects of Depression on Cognitive Function in the Elderly and Moderating Effects of Socioeconomic Status. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 13, 2735–2750. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Jeong, I.; Yun, D.; Sin, J. Location Tracking System using GPS Information. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Computer Information Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 17–19 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Seo, C.; Park, B.; Choi, B. Implementation of Smart Shoes for Dementia Patients using Embedded Board and Low Power Wide Area Technology. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Commun. Eng. 2020, 24, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.; Ok, S.; Park, M. Development of an AI-Based App for Preventing Missing Children and Elderly Using Location Information. J. Korean Soc. Ind. Converg. 2024, 27, 1713–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel Gharghan, S.; Saad Fakhrulddin, S.; Al-Naji, A.; Chahl, J. Energy-Efficient Elderly Fall Detection System Based on Power Reduction and Wireless Power Transfer. Sensors 2019, 19, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.; Kim, G.; Na, Y.; Kim, J.; Yoon, Y.; Ahn, H. Study on Development for Smart Door Lock and App. using Arduino and Infrared Sensor. J. Korea Inst. Electron. Commun. Sci. 2022, 17, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, C.Y.T.; Wong, M.S.; Griffiths, S.; Wong, F.Y.Y.; Kam, R.; Chin, D.C.W.; Xiong, G.; Mok, E. Performance Evaluation of iBeacon Deployment for Location-Based Services in Physical Learning Spaces. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, B.; Khriji, S.; Chéour, R.; Lahoud, C.; Moessner, K.; Kanoun, O. Improving the Reliability of Long-Range Communication against Interference for Non-Line-of-Sight Conditions in Industrial Internet of Things Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Huh, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.; Kim, J. Design and Implementation of Ultra-Long-Range LoRa Communication Module. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Commun. Eng. 2022, 26, 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. Design and implementation of blockchain-based anti-theft protocol in Lora environment. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2022, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.; Yeom, S.; Kang, J.; Choi, B.; Lee, M. CCW Algorithm-Based Honeybee Counting System and Honeybee Classification System. In Proceedings of the Korean Institute of Information Technology Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 2–4 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).