Estimation of the Shear Stress (WSS) at the Wall of Tracheal Bifurcation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

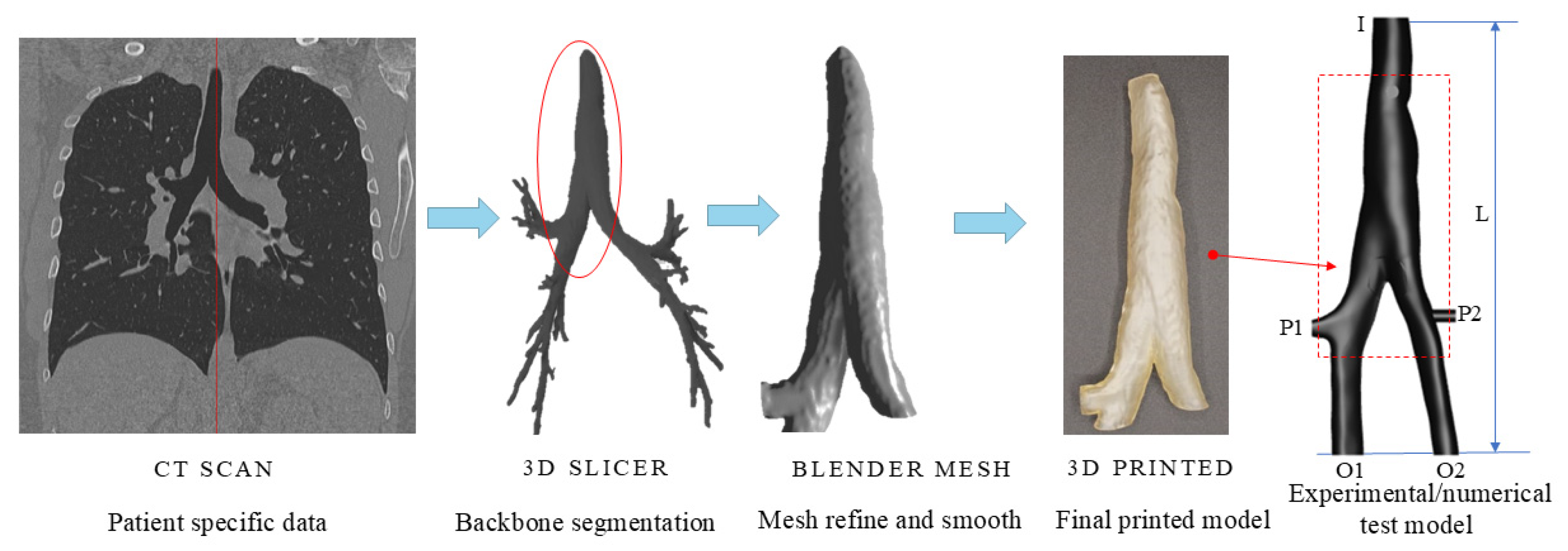

2.1. Construction of the Tracheal Model

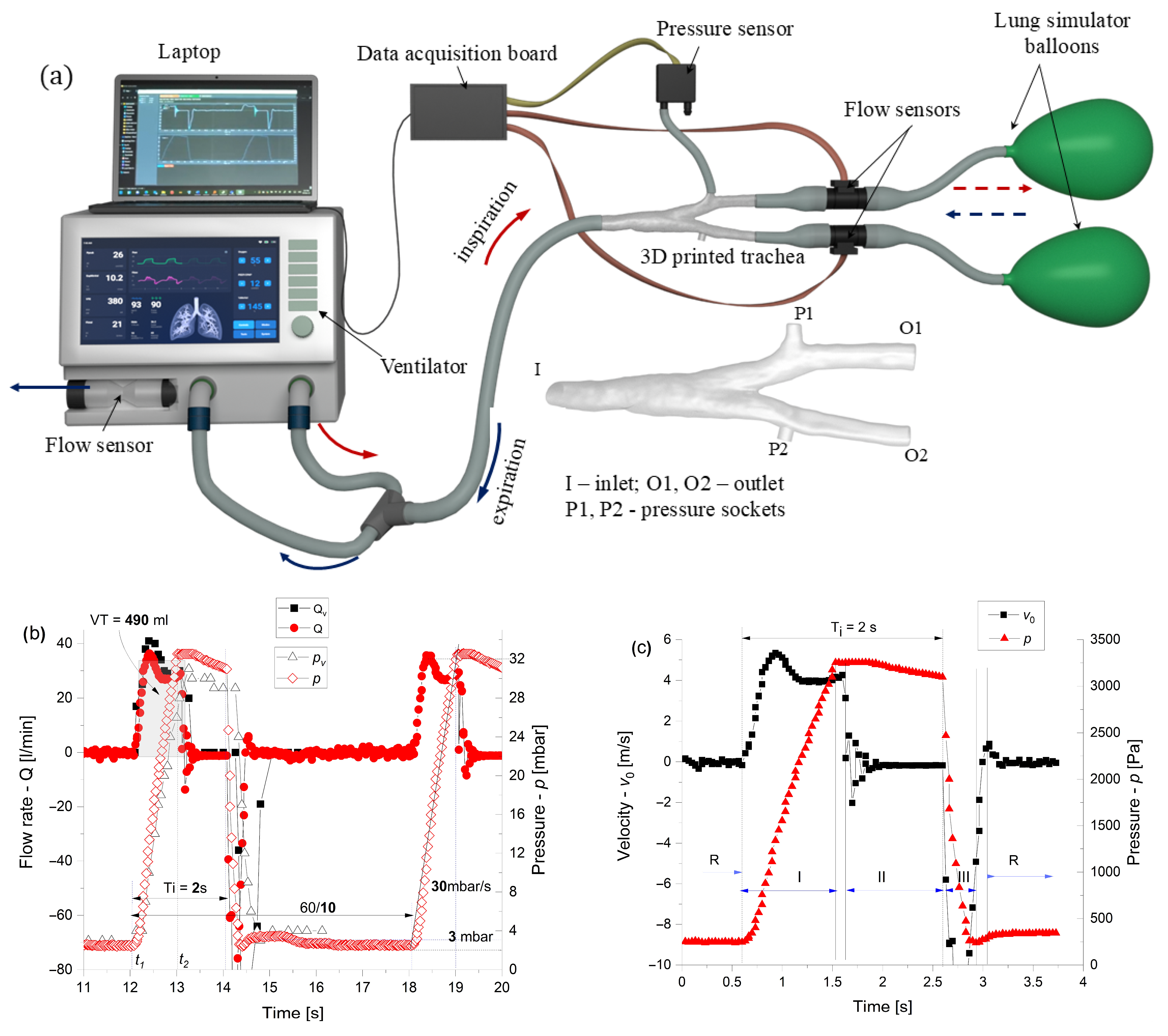

2.2. Experimental

2.2.1. Spirometer

2.2.2. Ventilator

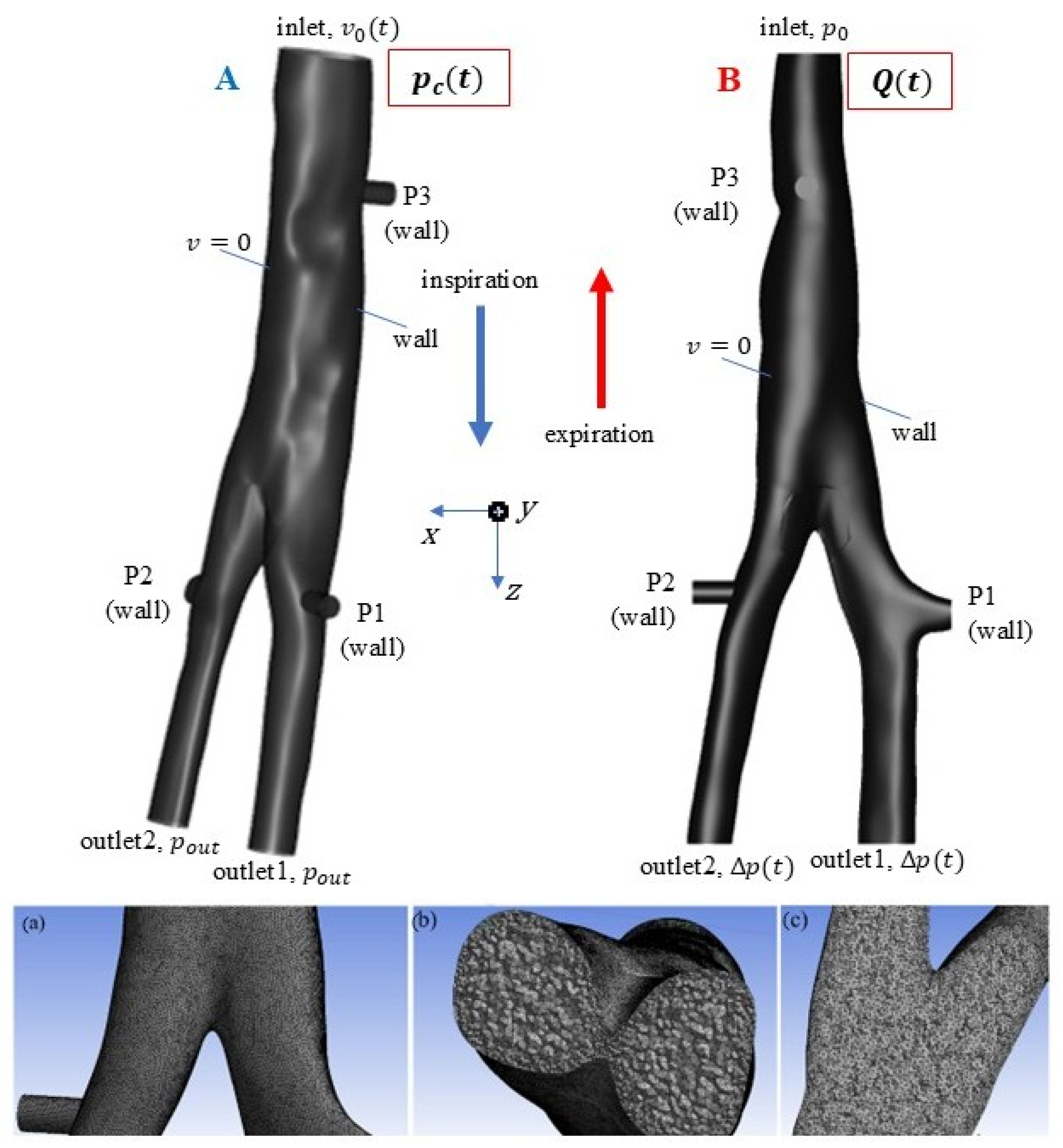

2.3. Numerical

- Since the flow rate is measured, case A is first simulated, and the pressure difference, ∆p(t) = pc(t) − pout, is obtained for the given geometry and boundary conditions: v0(t) at the inlet and pout at the outlet.

- The pressure difference from case A is used as input for case B: ∆p(t) at the outlet and p0 at the inlet. The calculated variation in flow rate in time is compared with the measured one, the result being validated qualitatively and quantitatively (within an admissible error range).

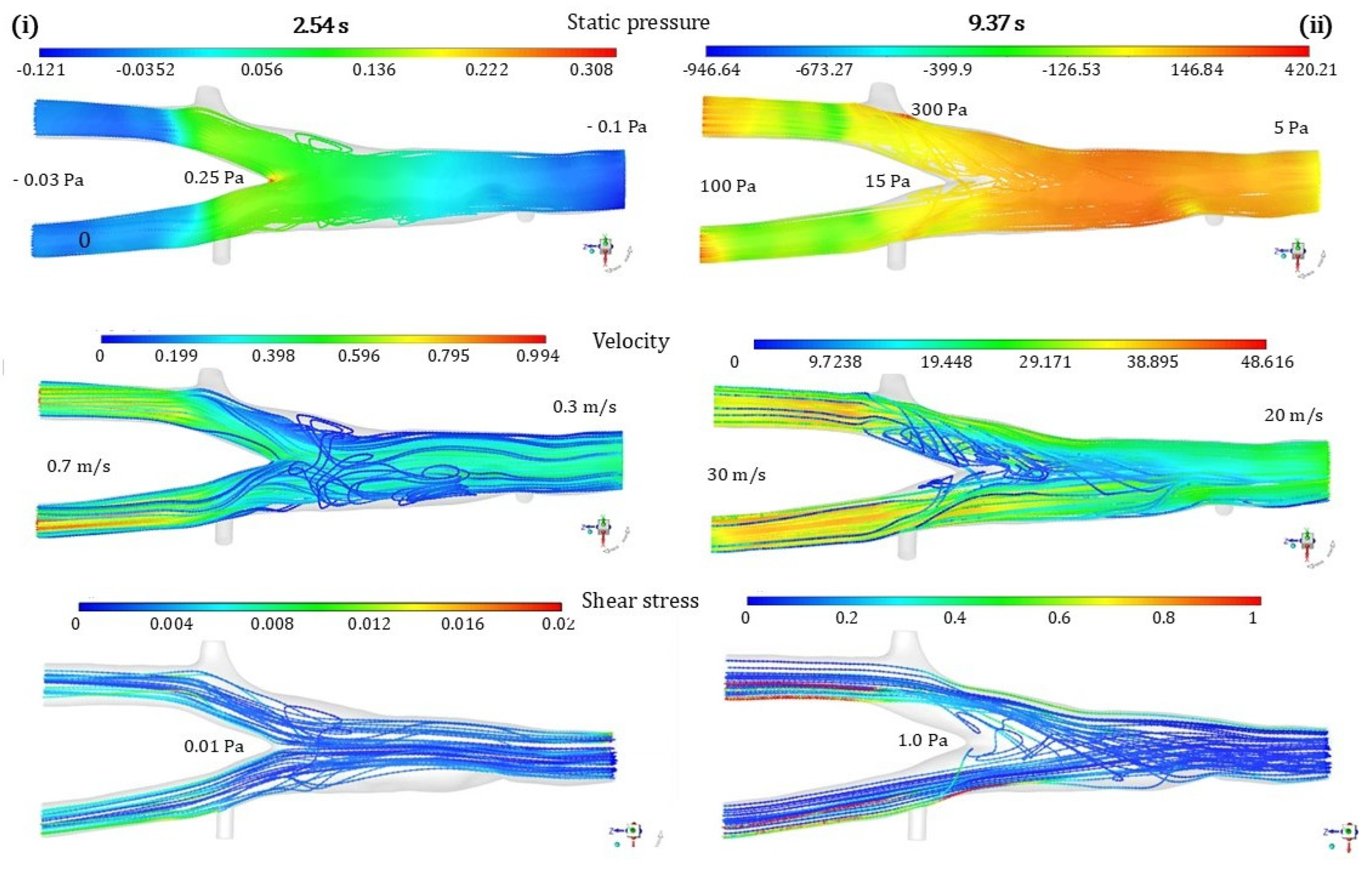

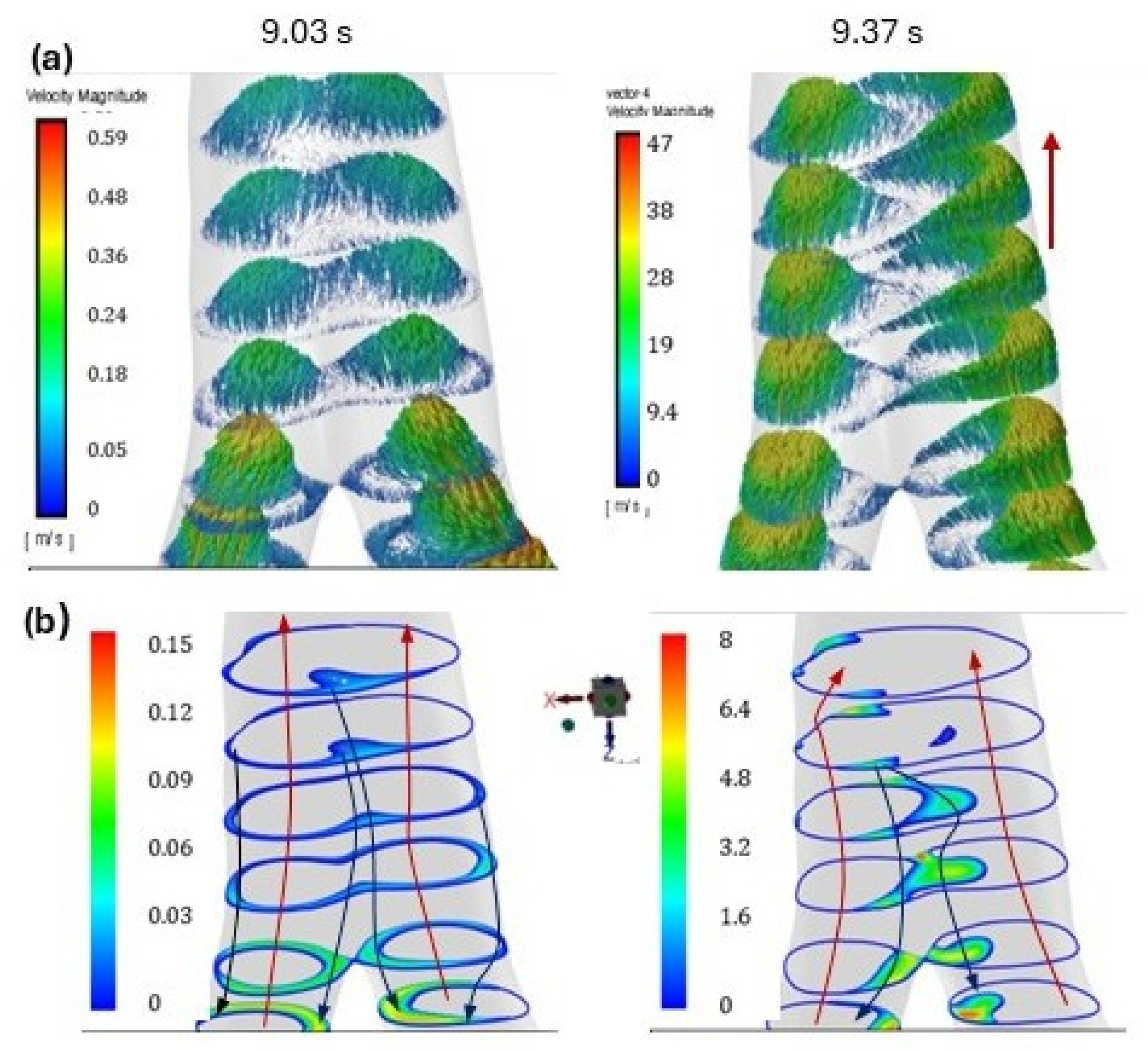

- After validation of case B, the flow spectrum, velocity, and stress distributions in the tracheal bifurcation are represented, and the results are analyzed.

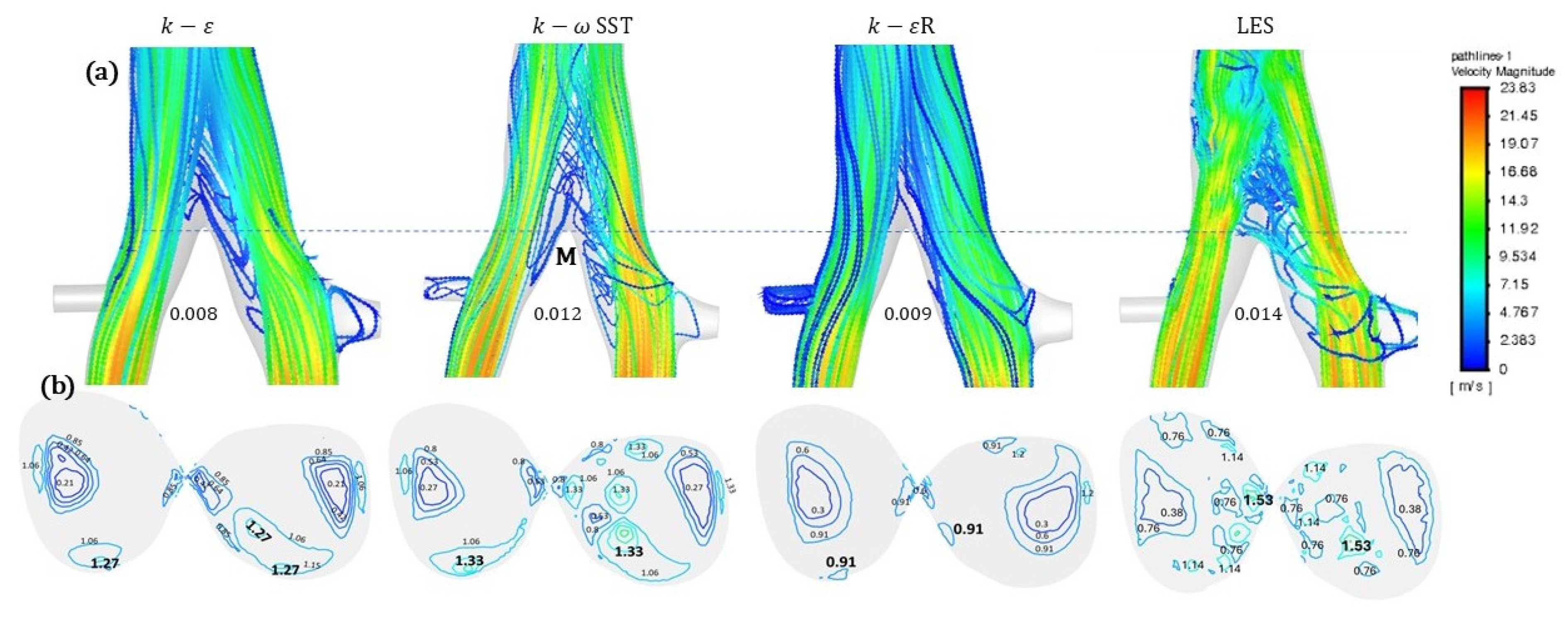

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, H.Y.; Liu, Y. Modeling the bifurcating flow in a CT-scanned human lung airway. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2681–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstreuer, C.; Zhang, Z. Airflow and particle transport in the human respiratory system. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2009, 42, 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yen, H.H.; Li, Y. Deposition of bronchiole-originated droplets in the lower airways during exhalation. J. Aerosol Sci. 2020, 142, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynot, W.J.; Gonthier, K.A.; Dunham, M.E.; Crosby, T.W. Classification of tracheal stenosis in children based on computational aerodynamics. J. Biomech. 2020, 104, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, Z.B.; Chen, X.L.; Yang, R.Y.; Yu, A.B. Numerical investigation of deposition mechanism in three mouth–throat models. Powder Technol. 2021, 378, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Trabelsi, O.; Ochoa, I.; He, J.; Gillard, J.H.; Doblare, M. Anisotropic material behaviours of soft tissues in human trachea: An experimental study. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemci, T.; Ponyavin, V.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Collins, R. Computational model of airflow in upper 17 generations of human respiratory tract. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2047–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.K.; Schröder, W. Numerical investigation of the three-dimensional flow in a human lung model. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2446–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.S.; Wüst, W.; Brand, M.; Stahl, C.; Allmendinger, T.; Schmidt, B.; Uder, M.; Lell, M.M. Dose Reduction in Abdominal Computed Tomography, Intraindividual Comparison of Image Quality of Full-Dose Standard and Half-Dose Iterative Reconstructions with Dual-Source Computed Tomography. Investig. Radiol. 2011, 46, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Leng, S.; McCollough, C.H. Dual-energy CT-based monochromatic imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 199, S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.J. Computational methods for electron tomography. Micron 2012, 43, 1010–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, D.C.; Benetos, G.; Rampidis, G.; von Felten, E.; Bakula, A.; Sustar, A.; Kudura, K.; Messerli, M.; Fuchs, T.A.; Gebhard, C.; et al. Validation of deep-learning image reconstruction for coronary computed tomography angiography: Impact on noise, image quality and diagnostic accuracy. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2020, 14, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrany, M.; Banerjee, A. A biomechanical model of pendelluft induced lung injury. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmark, E.; Anand, V.; Wheeler, A.; Zahn, A.; Cavari, Y.; Eluk, T.; Hay, M.; Katoshevski, C.; Gutmark-Little, I. Demonstration of mucus simulant clearance in a Bench-Model using acoustic Field-Integrated Intrapulmonary Percussive ventilation. J. Biomech. 2022, 144, 111305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla, F.J.; Morán, I.; Roche-Campo, F.; Mancebo, J. Ventilatory strategies in obstructive lung disease. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 35, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, V.K.; Kumar, B.; Jain, A.; Paul, A.R. A Computational Study on Airflow in Human Respiratory Tract at Normal and Heavy Breathing Conditions. In Proceedings of the 6th International and 43rd National Conference on Fluid Mechanics and Fluid Power, Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India, 15–17 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, R.; Kaczka, D.W. Impact of ventilation frequency and parenchymal stiffness on flow and pressure distribution in a canine lung model. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 41, 2699–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, K.; Brücker, C. The influence of airway tree geometry and ventilation frequency on airflow distribution. J. Biomech. Eng. 2015, 137, 081001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, J.J.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Gattinoni, L. Static and dynamic contributors to ventilator-induced lung injury in clinical practice pressure, energy, and power. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenga, R.L.; Longest, P.W.; Sundaresan, G. Creation of an in vitro biomechanical model of the trachea using rapid prototyping. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerekes, A.; Nagy, A.; Veres, M.; Rigó, I.; Farkas, A.; Czitrovszky, A. In vitro and in silico (IVIS) flow characterization in an idealized human airway geometry using laser Doppler anemometry and computational fluid dynamics techniques. Measurement 2016, 90, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Huang, S.W.; Chen, L.H.; Qi, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Li, S.T. Airflow behavior changes in upper airway caused by different head and neck positions: Comparison by computational fluid dynamics. J. Biomech. 2017, 52, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, T.; Adkins, L.; McWhorter, A.; Kunduk, M.; Dunham, M. Computational Fluid Dynamics Model of Laryngotracheal Stenosis and Correlation to Pulmonary Function Measures. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2023, 312, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorbahrami, K.; Oakes, J.M. Regional flow and deposition variability in adult female lungs: A numerical simulation pilot study. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 66, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliboni, L.; Tullio, M.; Pennati, F.; Lomauro, A.; Carrinola, R.; Carrafiello, G.; Nosotti, M.; Palleschi, A.; Aliverti, A. Functional analysis of the airways after pulmonary lobectomy through computational fluid Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Cai, M.; Hao, L.; Luo, Z.; Niu, J.; Xu, W.; Luo, Z. Numerical Analysis of Airway Mucus Clearance Effectiveness Using Assisted Coughing Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Gunatilaka, C.; McConnell, K.; Bates, A. The effect of including dynamic imaging derived airway wall motion in CFD simulations of respiratory airflow in patients with OSA. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarabia-Vallejos, M.A.; Zuñiga, M.; Hurtado, D.E. The role of three-dimensionality and alveolar pressure in the distribution and amplification of alveolar stresses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Tawhai, M.H.; Hoffman, E.A.; Lin, C.L. Airway Wall Stiffening Increases Peak Wall Shear Stress: A fluid-structure interaction study in rigid and compliant airways. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 1836–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéphano, J.; Mauroy, B. Wall shear stress distribution in a compliant airway tree. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 031907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska-Krawczyka, M.; Krenkea, R.; Grabczaka, E.M.; Light, R.W. Pleural manometry–historical background, rationale for use and methods of measurement. Respir. Med. 2018, 136, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondergaard, S.; Karason, S.; Hanson, A.; Nilsson, K.; Hojer, S.; Lundin, S.; Stenqvist, O. Direct measurement of intratracheal pressure in pediatric respiratory monitoring. Pediatr. Res. 2002, 51, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, A.; Yoshida, T.; Yamanaka, H.; Fujino, Y. Estimation of tracheal pressure and imposed expiratory work of breathing by the endotracheal tube, heat and moisture exchanger, and ventilator during mechanical ventilation. Respir. Care 2013, 58, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higeno, R.; Uchiyama, A.; Enokidani, Y.; Fujino, Y. Advanced cuff pressure control ventilation (ACPCV); a bench study of a new concept of mechanical ventilation. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2021, 45, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Brault, C.; Rodrigues, A.; Ko, M.; Vieira, F.; Phoophiboon, V.; Slama, M.; Chen, L.; Brochard, L. Distribution of airway pressure opening in the lungs measured with electrical impedance tomography (POET): A prospective physiological study. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yartsev, A. The Expiratory and Inspiratory Process, in Deranged Physiology—A Free Online Resource for Intensive Care Medicine. 2015. Available online: https://derangedphysiology.com/main/home (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Sul, B. Dynamics of the tracheal airway and its influences on respiratory airflows: An exemplar study. J. Biomech. Eng. 2019, 141, 111009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerling, J.; Vahaji, S.; Morton, D.A.V.; Fletcher, D.F.; Inthavong, K. Scale resolving simulations of the effect of glottis motion and the laryngeal jet on flow dynamics during respiration. Comp. Meth. Programs Biomed. 2024, 247, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, B.; Boucher, R.C. Role of Mechanical Stress in Regulating Airway Surface Hydration and Mucus Clearance Rates. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2008, 163, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.B.; Button, B.; Rubinstein, M.; Boucher, R.C. Physiology and pathophysiology of human airway mucus. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1757–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erken, O.; Fazla, B.; Muradoglu, M. Effects of elastoviscoplastic properties of mucus on airway closure in healthy and pathological conditions. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2023, 8, 053102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, A.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, X. A review on the mucus dynamics in the human respiratory airway. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2025, 24, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhaye, V.K.; Schweitzer, K.S.; Caterina, M.J.; Shimoda, L.; King, L.S. Shear stress regulates aquaporin-5 and airway epithelial barrier function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 3345–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Nieman, G.F.; Christie, J.D.; Fisher, A.B. Shear stress-related mechanosignaling with lung ischemia: Lessons from basic research can inform lung transplantation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L668–L680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahakis, N.E.; Hubmayr, R.D. Cellular Stress Failure in Ventilator-injured Lungs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 1328–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, A.; Guignabert, C.; Barberà, J.A.; Bärtsch, P.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Dewachter, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Dorfmüller, P.; et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelium: The orchestra conductor in respiratory diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1700745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, S. Endothelial shear stress enhancements: A potential solution for critically ill Covid-19 patients. Bio. Med. Eng. Online 2020, 19, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaati, H.; Monjezi, M. Airflow-related shear stress: The main cause of VILI or not? Tanaffos 2024, 23, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.J.; Green, A.S.; Thomas, N.K. Wall shear stress distributions in a model of normal and constricted small airways. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 2014, 228, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.S. Modelling of peak-flow wall shear stress in major airways of the lung. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livanos, A.; Bouchoris, K.; Aslani, K.E.; Gourgoulianis, K.; Bontozoglou, V. Prediction of shear stress imposed on alveolar epithelium of healthy and diseased lungs. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2024, 23, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, G.; Suki, B.; Lutchen, K. Modeling air flow-related shear stress during heterogeneous constriction and mechanical ventilation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sul, B.; Wallqvist, A.; Morris, M.J.; Reifman, J.; Rakesh, A. Computational study of the respiratory air flow characteristics in normal and obstructed human airways. Comp. Biol. Med. 2014, 52, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheriana, S.; Rahaia, H.; Taheriana, B.G.S.; Rahaia, H.; Gomeza, B.; Waddingtonb, T.; Mazdisnian, F. Computational fluid dynamics evaluation of excessive dynamic airway collapse. Clin. Biomech. 2017, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Heise, R.L.; Reynolds, A.M.; Pidaparti, R.M. Quantification of Age-Related Lung Tissue Mechanics under Mechanical Ventilation. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Meng, J.; Ma, C.; Wa, H.; Chen, Y.; Luo, F. Numerical simulation of voluntary respiration in a model of the whole human lower airway. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2025, 24, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.K.; Burgreen, G.W.; Lavallee, D.M.; Thompson, D.S.; Hester, R.L. Efficient, physiologically realistic lung airflow simulations. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 3016–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Yang, X.; Zhou, C.; Ling, T.; Hu, B.; Song, Y.; Liu, L. Computed tomography-based bronchial tree three-dimensional reconstruction and airway resistance evaluation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2020, 29, 1981–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Su, W.C.; Chen, Y.; Shang, Y.; Dong, J.; Tu, J.; Tian, L. A combined computational and experimental study on nanoparticle transport and partitioning in the human trachea and upper bronchial airways. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2404–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, N.H.; Osman, K.; Helmi, N.H.N.; Abdul Kadir, M.A.R. Comparative analysis of realistic CT-scan and simplified human airway models in airflow simulation. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 18, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalas, A.; Nousias, S.; Kikidis, D.; Lalos, A.; Arvanitis, G.; Sougles, C.; Moustakas, K.; Votis, K.; Verbanck, D.; Usmani, O.; et al. Substance deposition assessment in obstructed pulmonary system through numerical characterization of airflow and inhaled particles attributes. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, C.; Hang, J.; Deng, Q. Particle deposition in human lung airways: Effects of airflow, particle size, and mechanisms. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2846–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, S.M. COVID19-CT-Dataset: An Open-Access Chest CT Image Repository of 1000+ Patients with Confirmed COVID-19 Diagnosis. Harvard Dataverse. 2021. Available online: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/6ACUZJ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Menter, F.; Sechner, R. Best Practice: RANS Turbulence Modeling in Ansys CFD, Course, 2021. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/637262645/Best-Practice-Rans-turbulence-modeling-in-Ansys-CFD (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Lancmanová, A.; Bodnár, T. Numerical simulations of human respiratory flows: A review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheed, R.; Mohammadian, A.; Gildeh, H.K. A comparison of standard k-ε and realizable k-ε turbulence models in curved and confluent channels. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2019, 19, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Hussain, F. On the identification of a vortex. J. Fluid Mech. 1995, 285, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, C.; Broboana, D.; Kadar, R.; Giurgea, C.; Rafiroiu, D.; Bernad, S. Biomedical vortex flows. In Vortex Dominated Flows; Susan-Resiga, R., Bernad, S., Muntean, S., Eds.; Eurostampa: Timisoara, Romania, 2007; pp. 429–492. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddam, M.G.; Santhanakrishnan, A. Effects of varying inhalation duration and respiratory rate on human airway flow. Fluids 2021, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.B.; Park, J.; Jang, J.; Cho, Y.; Park, D.S.; Kim, C.; Bae, G.N.; Jang, A. Study on the initial velocity distribution of exhaled air from coughing and speaking. Chemosphere 2012, 87, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschumperlin, D.J.; Drazen, J.M. Mechanical stimuli to airway remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, S90–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zheng, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y. Mechanotransduction regulates the interplays between alveolar epithelial and vascular endothelial cells in lung. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 818394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; De, A. Dynamics of oscillatory fluid flow inside an elastic human airway. In Numerical Fluid Dynamics. Forum for Interdisciplinary Mathematics; Zeidan, D., Merker, J., Da Silva, E.G., Zhang, L.T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaci, A.V.I.; Totorean, A.F.; Bedreag, O.H.; Papurica, M. Numerical analysis of airflow in a patient-specific 3D recon-structed trachea and bronchi model. In Acoustics and Vibration of Mechanical Structures—AVMS-2025; Herisanu, N., Marinca, V., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Physics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, S.; Nemes, A.; Van de Moortele, T.; Schmitter, S.; Coletti, F. Three-dimensional inspiratory flow in a double bifurcation airway model. Exp. Fluids 2016, 57, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, T.; Katrin Bauer, K. Development of a 3D-PTV algorithm for the investigation of characteristic flow structures in the upper human bronchial tree. In Proceedings of the 18th International Symposium on the Application of Laser and Imaging Techniques to Fluid Mechanics, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–7 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, K.; Chaves, H.; Brücker, C. Visualizing flow partitioning in a model of the upper human lung airways available to purchase. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010, 132, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizal, F.; Jedelsky, J.; Morgan, K.; Bauer, K.; Llop, J.; Cossio, U.; Kassinos, S.; Verbanck, S.; Ruiz-Cabello, J.; Santos, A.; et al. Experimental methods for flow and aerosol measurements in human airways and their replicas. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 113, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagemann, E.; Roeb, J.; Brunton, S.L.; Lagemann, C. A deep learning approach to wall-shear stress quantification: From numerical training to zero-shot experimental application. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1014, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Ghim, M.; Mohamied, Y.; Sherwin, S.J.; Weinberg, P.D. Endothelial cells do not align with the mean wall shear stress vector. J. R. Soc. Interface 2021, 18, 20200772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankyu Lee, H.; Marin-Araujo, A.E.; Aoki, F.G.; Haykal, S.; Waddell, T.K.; Cristina, H.; Amon, C.H.; Romero, D.A.; Karoubi, G. Computational fluid dynamics for enhanced tracheal bioreactor design and long-segment graft recellularization. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Even-Tzur, N.; Kloog, Y.; Wolf, M.; Elad, D. Mucus secretion and cytoskeletal modifications in cultured nasal epithelial cells exposed to wall shear stresses. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 2998–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time | 0.74 | 2.71 | 4.14 | 9.03 | 9.37 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | ||||||

| 0.310 | 0.0087 | 4.5 × 10−5 | 0.0013 | 0.57 | ||

| 0.283 | 0.012 | 0.0211 | 0.00197 | 1.1 | ||

| 0.286 | 0.0096 | 0.0197 | 0.0014 | 0.72 | ||

| LES | 0.278 | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.0017 | 2.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanase, N.-O.; Mateescu, C.-S.; Cristea, D.-D.; Balan, C. Estimation of the Shear Stress (WSS) at the Wall of Tracheal Bifurcation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13055. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413055

Tanase N-O, Mateescu C-S, Cristea D-D, Balan C. Estimation of the Shear Stress (WSS) at the Wall of Tracheal Bifurcation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13055. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413055

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanase, Nicoleta-Octavia, Ciprian-Stefan Mateescu, Doru-Daniel Cristea, and Corneliu Balan. 2025. "Estimation of the Shear Stress (WSS) at the Wall of Tracheal Bifurcation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13055. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413055

APA StyleTanase, N.-O., Mateescu, C.-S., Cristea, D.-D., & Balan, C. (2025). Estimation of the Shear Stress (WSS) at the Wall of Tracheal Bifurcation. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13055. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413055