Abstract

A plane strain analytical model was developed for the interaction between inclined multilayered rock strata and concrete tunnel lining in deep buried tunnels, with both structures treated as homogeneous isotropic elastic bodies and two contact modes, no-slip and full-slip, considered. A non-iterative complex variable function method was employed, by which analytical challenges in multiply connected domains were overcome and explicit stress and displacement solutions were obtained. Validation was performed through boundary-condition checks and comparative numerical simulations. The results show that under different tangential contact modes, layer inclinations, and lateral pressure coefficients, the stress error on the inner surface of the lining remains in the order of 10−2 Pa. The stress and displacement components on both sides of each interface satisfy the associated continuity conditions with excellent agreement. The proposed analytical method nearly perfectly satisfies all boundary and continuity conditions. Under non-hydrostatic loading conditions, the numerical and analytical results for different tangential contact modes also show excellent agreement. The von Mises stress errors are generally controlled within 0.03 MPa, and the maximum relative error—located near the inner surface of the lining—remains below 4%, while displacement errors stay below 0.2 mm. Interface stress jumps are accurately captured and oscillations in zones with high stiffness contrast are effectively avoided. The method is presented as a fast and reliable analytical tool for tunnel design under complex multilayered rock conditions.

1. Introduction

With the continuous development of tunnel engineering, the geological conditions encountered during tunnel excavation have become increasingly complex and severe [1,2,3]. Among these, parallel inclined multilayered rock formations generated by tectonic movements are a common geological feature in deeply buried tunnel projects [4,5]. Compared with homogeneous surrounding rock, inclined multilayered rock exhibits an “interlayer mismatch” effect due to differences in mechanical properties between layers [6,7,8]. This composite mechanical behavior generates additional stress concentrations and strain incompatibilities at the interfaces. It also leads to more complex and asymmetric stress and displacement fields. Pan et al. [9], Wang et al. [10], Assefa et al. [11], and others have shown that the inclination of rock layers significantly affects the stress distribution, deformation characteristics, and stability of tunnel surrounding rock. In inclined multilayered rock, excavation and lining installation together increase the complexity of the stress and displacement fields. As a result, accurately predicting these asymmetric responses becomes critical for tunnel safety. For a long time, numerical simulations and theoretical analytical methods have been key approaches for analyzing the mechanical responses of tunnel surrounding rock and concrete lining structures [12,13,14]. Compared with numerical simulations, analytical methods avoid extensive and complex numerical modeling [15,16,17]. They provide higher computational efficiency and faster solution speed. They also reveal the intrinsic relationships between key parameters and mechanical responses more transparently [18,19,20].

The complex variable function theory developed by Muskhelishvili [21] provides a well-established analytical framework for studying tunnel–rock interaction. It employs conformal mapping and power-series techniques to obtain closed-form solutions for arbitrary tunnel shapes and complex boundary conditions. Owing to these capabilities, the method has received wide attention from researchers [22]. Early studies applied complex variable function theory to derive solutions for single circular tunnels in homogeneous isotropic elastic media [23,24]. Later, by introducing conformal mapping functions, researchers have extended the method to unsupported non-circular tunnels. Analytical solutions are obtained for elliptical [25], horseshoe-shaped [26], and other complex cross-sections, and some studies further incorporated transversely isotropic rock properties [23]. As the demand for multi-tunnel analysis increased, iterative computations based on the Schwarz alternating method allow the complex variable function theory to be applied to doubly or multiply connected domains [27,28]. Using this theoretical foundation, Jia et al. [29] developed analytical models for hydraulic-mechanical coupling of double circular tunnels in saturated strata. Zeng et al. [30] proposed a generalized time-dependent analytical model for efficiently predicting the sequential excavation response of shallow multi-tunnel circular tunnels. They [31] also presented high-precision analytical solutions for shallow non-circular double tunnels. However, these studies typically ignored tunnel concrete lining structures, instead applying convergence displacement or virtual concrete lining forces at the tunnel boundaries.

To better align analytical theory with practical engineering, scholars have progressively incorporated tunnel concrete lining and its interaction with surrounding rock into analytical frameworks. Wang et al. [32] considered no-slip contact effects between rock and concrete lining to develop an analytical method for the seepage and mechanical response of non-circular deeply buried supported tunnels in saturated strata. Gao et al. [33] proposed an analytical method for elastic stress and displacement in shallow supported tunnels, considering both no-slip and full-slip interactions at the rock–concrete lining interface. Yu and Chen [34] developed simplified analytical solutions for seismic responses of arbitrarily shaped deeply buried supported tunnels, systematically assessing the effects of cross-section shape, relative stiffness, and contact conditions. Chen et al. [35] developed unified analytical solutions for deeply buried tunnels with arbitrary cross-sections in saturated orthotropic rock under seismic loading. The model considers both no-slip and full-slip rock–lining interface conditions, as well as drained and undrained cases. These studies, while incorporating rock–concrete lining interactions, treated the surrounding rock as homogeneous and did not account for the composite layered mechanical characteristics.

When traditional complex variable function theory is applied to multiply connected domains with multiple boundaries, the Schwarz alternating method is typically required. This method relies on iterative computations, and its accuracy and efficiency are strongly affected by the number of iterations. To address this, Fang et al. [36,37] developed a non-iterative extended complex variable function method, treating different cavities as independent and using separate conformal mappings and complex potentials to solve each cavity’s mechanical contribution. This approach expresses the mechanical response of multiply connected, multi-boundary problems as the superposition of individual contributions, providing a new non-iterative analytical strategy for accurate solutions. Subsequently, Zhang et al. [28] used this method to precisely analyze mechanical responses of deep tunnels with dense contact, local non-contact, and loose contact at the rock–concrete lining interface. However, these studies modeled the surrounding rock as a single homogeneous medium and did not consider multilayered stratification. Fang et al. [38,39] successfully applied the non-iterative complex variable function theory to arbitrary-shaped supported multi-tunnel systems, achieving excellent predictive results. Liu et al. [40] established analytical models for multiple tunnels intersecting existing tunnels, systematically analyzing the mechanical influence on existing tunnels. Additionally, Hong et al. [41] and Sun et al. [42] extended the method to shallow tunnels in complex strata, considering horizontal layering but not the presence of concrete lining structures or arbitrary inclination. These studies primarily focused on urban shallow-buried settings and did not consider arbitrary inclinations of stratigraphic interfaces, which distinguishes them from the deeply buried conditions examined in this work. Consequently, no specific studies have addressed the analytical prediction of mechanical responses for deeply buried supported tunnels in inclined multilayered rock.

To address the challenge of predicting complex mechanical responses of deeply buried supported tunnels in inclined multilayered rock, this study constructs a plane strain analytical model for multilayered rock–concrete lining interaction. A fully bonded relationship is assumed between layers to represent the composite mechanical properties of the rock. Based on this model, no-slip and full-slip extreme contact conditions at the rock–concrete lining interface are considered, and a non-iterative complex variable function method is introduced to propose an analytical solution for stresses and displacements in deeply buried supported tunnels within parallel inclined layers. The model is verified through boundary condition checks and comparisons with numerical simulations. This research aims to provide new theoretical and technical concrete lining for rapid prediction and engineering design of supported tunnels under complex multilayered rock conditions.

2. The Establishment of the Mechanical Model

Before establishing the model, the following three basic assumptions are made.

- (1)

- The deeply buried composite surrounding rock is composed of several inclined strata interlayered with each other. The interfaces between the strata are parallel and non-intersecting. Each stratum is regarded as a homogeneous, isotropic, linear elastic body, which enables explicit analytical derivations while still reflecting the key interlayer stiffness mismatch that governs stress redistribution. The strata are assumed to remain perfectly bonded, without sliding or separation. This assumption is appropriate for deeply buried rock masses where strong interlayer confinement prevents noticeable slip or separation. In geological settings with weakly bonded or soft interlayers (e.g., weak fault zones), interlayer slip may occur and more realistic interaction models would be required. In this study, the analysis focuses on conditions where the interlayers are strongly constrained and can be reasonably treated as perfectly bonded.

- (2)

- Owing to the large burial depth of the tunnel, the effect of gravity is neglected, as the far-field in situ stresses significantly exceed the self-weight component.

- (3)

- The tunnel is sufficiently long in the longitudinal direction, so the problem is treated as a plane strain condition, a standard assumption for deep and long tunnels with negligible end effects.

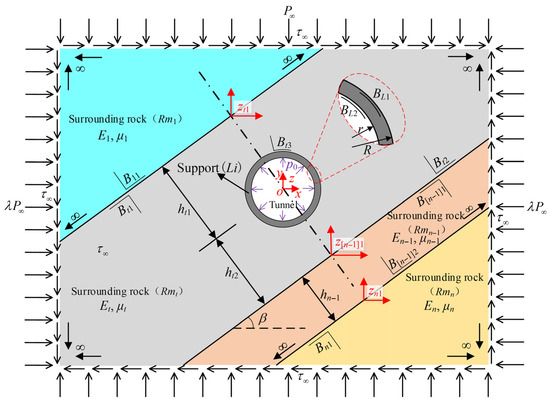

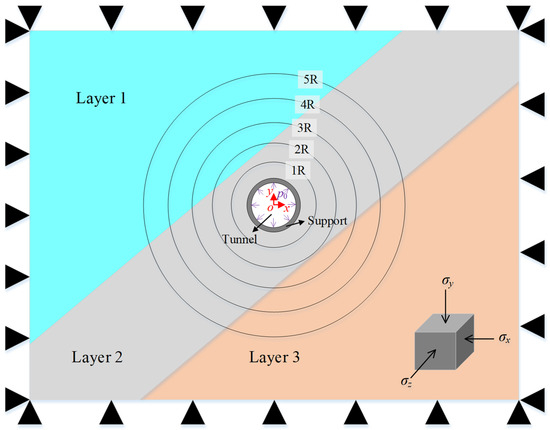

Establish the plane strain mechanical model shown in Figure 1. The composite surrounding rock extends to infinity outward. In the initial state any point within the surrounding rock is subjected to a vertical normal stress P∞, a shear stress τ∞, and a lateral pressure coefficient λ. The inclined interbedded strata are numbered from top to bottom as Rm1~Rmn. The elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the i stratum are Ei and μi, respectively. The circular annular tunnel concrete lining Li is entirely embedded in stratum Rmt. The outer and inner radii of the concrete lining are R and r. The concrete lining has elastic modulus El and μl. A uniformly distributed normal inward pressure p0 acts on the inner boundary of the concrete lining. The vertical distance from the tunnel cross-section center to the upper boundary of Rmt is ht1 and to the lower boundary is ht2. The vertical distance between the upper and lower boundaries of any other inclined stratum Rmi (i ≠ t) is hi. Taking the tunnel cross-section center as the origin, define a global physical coordinate system XOY. Any point in the complex plane has the global physical coordinate z = x + iy. The inclination angle of the strata measured from the positive X axis is β.

Figure 1.

Mechanical model of a deeply buried composite surrounding rock containing a supported tunnel.

3. Solution for Stresses and Displacements

For clarity, the core analytical steps adopted in this study are summarized below.

To begin with, a plane strain mechanical model is established for a deeply buried tunnel embedded in parallel inclined multilayered rock strata. Subsequently, all independent boundaries are numbered, and the global and local coordinate systems are defined. For each boundary, an appropriate conformal mapping function is determined so that the original geometry can be transformed into the corresponding unit circle domain.

Next, based on the non-iterative extended complex variable function theory, the stress and displacement solutions for both the surrounding rock and the lining are derived in terms of the local mapping coordinates. Following this, calculation points are selected on each boundary according to a predefined point-selection scheme. Using the complex potential solutions, the mechanical responses at arbitrary points in the rock and lining are then expressed in terms of the unknown complex coefficients, with full derivations provided in the Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C.

After obtaining these expressions, linear constraint equations are formulated at all calculation points by enforcing the boundary conditions and interlayer continuity conditions. These equations are subsequently assembled into a complete linear system, which is solved to determine the unknown complex coefficients. Finally, by substituting these coefficients back into the analytical expressions, the full stress and displacement fields of the system are obtained.

This conceptual overview outlines the essential logic of the analytical formulation, while the detailed mathematical developments are presented in the subsequent sections and the Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C.

3.1. Complex Functions and Conformal Mapping

Based on the non-iterative complex function analytical theory for multi-boundary problems, a multi-boundary problem can be decomposed into several independent single-boundary problems for analysis. Each independent boundary generates a distinct response contribution in its associated calculation domain, and the overall mechanical response of the domain is obtained by the linear superposition of all individual boundary contributions. In this study, an analytical theory is developed for the mechanical response of a deeply buried supported tunnel based on the non-iterative complex function analytical framework. The tunnel is assumed to fully penetrate a composite multilayered surrounding rock mass.

For the convenience of theoretical derivation, the independent boundaries are first assigned numerical labels. Let the independent boundary Bij represent the j-th independent boundary of the i-th inclined stratum Rmi. if i = l, it denotes the concrete lining region. In general, for the first and n-th strata, j = 1. For strata that do not contain the tunnel or concrete lining, j = 2, and for strata traversed by the tunnel, j = 3. Taking the fully penetrated inclined stratum Rmt as an example, its inclined upper boundary, inclined lower boundary, and the boundary separating it from the concrete lining are numbered sequentially as Bt1, Bt2 and Bt3. In addition, interfaces between strata are assigned different labels within their respective strata. For instance, the boundaries B[n−1]2 and Bn1 correspond to the interfaces of the n − 1 and n strata, respectively.

Next, establish a local physical coordinate system (XOY)ij for each independent boundary Bij. The origin and axes of each local coordinate system are defined as follows: for coincident boundaries, the local coordinate systems are identical; for inclined stratum interfaces, the origin Oij of the local system is located at the foot of the perpendicular drawn from the tunnel center to the interface, and the Xij and Yij axes are oriented the same as the global coordinate system. The local physical coordinate systems for the rock–concrete lining interface and the inner and outer boundaries of the concrete lining coincide with the global coordinate system. By unifying the orientation of all local coordinate axes, the mechanical response vectors of the independent boundaries can be linearly superposed in a simplified manner. The relationship between the global physical coordinate z and the local physical coordinate zij is expressed as follows.

where vij denotes the global physical coordinate of the origin Oij, which depends on the vertical distance hi and the inclination angle β. When β ∈ [0, π/2], corresponds to the boundary above the tunnel center, and corresponds to the boundary below the tunnel center. When β ∈ (π/2, π), corresponds to the boundary above the tunnel center, and corresponds to the boundary below the tunnel center, respectively.

In the local physical coordinate system (XOY)ij, a conformal mapping ωij is used to transform the independent boundary and the designated region into a unit circle and its interior or exterior. A fractional linear mapping is employed to map the upper (or lower) boundary of an independent stratum and the surrounding rock above (or below) it onto the unit circle and its interior.

where λij is the mapping scaling factor, which is generally taken as the concrete lining outer radius R. ζij denotes the coordinate of zij in the local mapped plane. The term eiβ represents a rotation of the coordinate system by an angle β clockwise about the origin Oij, used to align the local physical coordinate orientation with that of the global coordinate system.

A scaling mapping is used to perform a conformal transformation of the circular boundary.

where ρ denotes the radius of the circular boundary to be mapped.

3.2. Solution of Stress and Displacement Components

According to the theory of complex functions, a set of analytic complex potential functions Φij(zij) and Ψij(zij) is introduced for each independent boundary Bij. The stress components contributed by the independent boundary can then be expressed as follows.

The displacement components are given by the following equation.

where Gi is the shear modulus of the i-th stratum, κi is the material parameter of the i-th stratum, under plane strain conditions, and Aij is a complex constant representing rigid-body translation and rotation.

According to the non-iterative complex function analytical theory, the mechanical response is obtained as the vector sum of the response contributions from all independent boundaries. Since the local physical coordinate systems have been unified, a direct linear superposition can be applied. The Cartesian stress components of each stratum in the composite surrounding rock are thus expressed as following.

The Cartesian displacement components of the surrounding rock are given by the Equation (7).

The Cartesian stress components of the concrete lining structure are given by the Equation (8).

The Cartesian displacement components of the concrete lining structure are expressed in the Equation (9).

By applying the conformal mapping function, the mechanical response contributions of the independent boundaries are expressed uniformly in their corresponding local mapped planes. For the upper and lower boundaries of the strata, as well as the outer boundary of the concrete lining, these are collectively treated as the outer boundaries in the study. For these boundaries, the analytic complex potential functions Φij(zij) and Ψij(zij) admit Laurent series expansions within the mapped unit circle and its interior.

For the rock–concrete lining interface and the inner boundary of the concrete lining, these are collectively referred to as the inner boundaries. For these boundaries, the analytic complex potential functions Φij(zij) and Ψij(zij) admit Laurent series expansions outside the mapped unit circle in the local plane.

where s denotes the highest (or lowest) power of ζij in the series expansion. For convenience in analysis, the value of s is taken to be the same for all sets of analytic complex potential functions in this study.

According to the chain rule for composite functions, the derivatives of Φij(zij) and Ψij(zij) appearing in the stress and displacement expressions are given by Equation (12).

By using Equation (12) to express the mechanical responses in the local mapped plane, the Cartesian stress components of the surrounding rock can be rewritten as follows.

The Cartesian displacement components of the surrounding rock can be expressed as Equation (14).

The Cartesian stress components of the concrete lining structure can be expressed as Equation (15).

The Cartesian displacement components of the concrete lining structure can be expressed as Equation (16).

The explicit expressions of the functions in Equations (13)–(16) are as follows.

Considering that the stress and displacement conditions are usually defined along the tangential and normal directions of a boundary, expressing them in terms of orthogonal curvilinear components greatly facilitates the formulation of boundary condition equations. To this end, it is necessary to transform the Cartesian components of the mechanical response along a specified path into orthogonal curvilinear components relative to that path. The orientation of the orthogonal curvilinear coordinates is defined as follows: if the same mapping function is used for the path on both sides, the orientations of the curvilinear components are identical; if different mapping functions are used-typically at the interface between two computational domains-both sides are conformally mapped to the unit circle, and the orientations of the orthogonal curvilinear components on opposite sides of the interface are opposite.

Along a specified path, the relationship between the Cartesian stress components and the orthogonal curvilinear stress components is expressed as Equation (18).

Similarly, the displacement components satisfy the following transformation relationship.

where the angle α is defined as the angle between the outward normal of the boundary in the physical plane and the positive X axis. According to the theory of conformal mapping and orthogonal curvilinear coordinates, when a path is arbitrarily specified as B, the value of the function and along the path can be calculated by the following Equation.

where the path B is an arbitrarily specified curve that includes all boundaries Bij, and ω is the conformal mapping function from path B to the unit circle.

Using Equations (18)–(20), the stress in the surrounding rock along the specified boundary B can be rewritten in terms of the orthogonal curvilinear components along path B (hereafter referred to as the orthogonal curvilinear components).

where the orthogonal curvilinear stress components at a point z on path B under far-field conditions are obtained from the stress components P∞, λP∞, and τ∞ through the following transformation.

The orthogonal curvilinear displacement components of the surrounding rock are given by Equation (23).

Similarly, the orthogonal curvilinear stress components of the concrete lining along a specified boundary Bkl are given by Equation (24).

The orthogonal curvilinear displacement components of the concrete lining are given by Equation (25).

At this stage, the Cartesian and polar (orthogonal curvilinear) components of stress and displacement for the composite surrounding rock and the concrete lining have been fully formulated. It should be noted that while the forms of all response solutions are determined, they still contain unknown complex coefficients within the analytic complex potential functions. These coefficients must be further solved by applying the constraint equations imposed at the inner and outer boundaries.

3.3. Solution of Undetermined Complex Coefficients

In this study, the undetermined complex coefficients are solved using the point-matching method. This approach selects a finite number of calculation points along all boundaries and determines the unknown coefficients by enforcing the corresponding boundary condition constraints at each selected point. By replacing the enforcement of boundary conditions along the entire boundary with a finite set of points, the method provides a weak-form solution of the mechanical response. With a reasonable distribution and enough calculation points, the point-matching method can yield highly accurate analytical solutions.

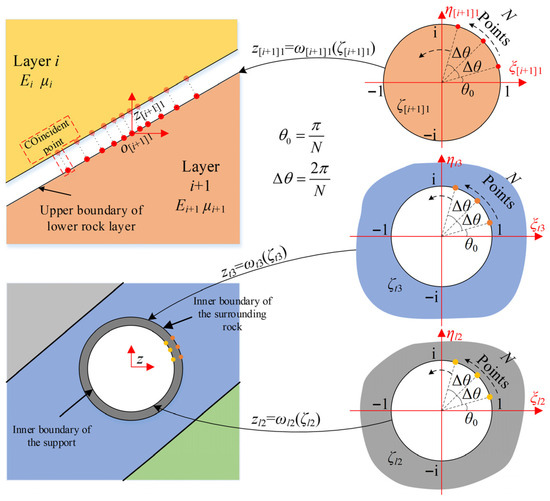

The point-matching method establishes the constraint equations for the unknown complex coefficients at the calculation boundary points. First, a set of calculation points satisfying the requirements must be selected on the specified boundary. The method of selecting calculation points differs for different types of independent boundaries, but generally follows the three-step procedure: “select the reference boundary → conformally map the reference boundary to the unit circle → select calculation points on the mapped unit circle.”

First, regarding the selection of the reference boundary Bkl. For an inclined stratum interface, the upper boundary of the underlying stratum is selected as the reference boundary of the interface. For example, for the interface between the i-th and (i + 1)-th strata, the boundary B[i+1]1 is selected as the reference boundary; for the interface between the composite surrounding rock and the concrete lining, the inner boundary of the surrounding rock Bt3 is selected as the reference boundary; for the inner boundary of the concrete lining Bl2, it is chosen as its own reference boundary.

Next, as shown in Figure 2, the reference boundary is mapped to the unit circle in the local mapped plane using the conformal mapping functions shown in Equations (2) and (3). On the unit circle, N calculation points are selected equally spaced in the counterclockwise direction, starting from the initial angle θ0 = π/N with angular interval Δθ = 2π/N, forming the set of calculation points (ζkl|ζkl = exp(i[θ0 + (k − 1)Δθ]), k = 1, 2, …, N). The number of points N is defined as a positive power of 2, and N ≥ 2s + 1. Two independent boundaries of an interface share the same set of calculation points.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the selection of calculation points on each independent boundary.

3.4. Boundary Condition Constraint Equations

The boundary condition constraint equations for the undetermined complex coefficients must be established at the calculation points based on the stress or displacement boundary conditions. The specific forms of the constraint equations for different types of boundaries are as follows.

- (1)

- Continuity conditions at stratum interfaces

Since the stratum interfaces remain perfectly bonded, the radial normal stress σρ and the shear stress τρθ on the interface satisfy continuity conditions, namely, σρ is equal on both sides of the interface and τρθ is also equal on both sides. Taking the interface between the i-th and (i + 1)-th strata as an example (1 ≤ i ≤ n − 1), the reference boundary is B[i+1]1, and the reference local mapping coordinates of the set of calculation boundary points are ζ[i+1]1. By applying Equations (A5) and (A15), the stresses at any calculation boundary point satisfy the following continuity conditions.

where the reference mapping coordinate |ζ[i+1]1| = 1 indicates that the calculation point lies on boundary B[i+1]1. The symbol ζij (with i possibly equal to i + 1) denotes the local mapping coordinate of the calculation point in the local mapped plane of the associated boundary Bij. All such points correspond to the same point in the global physical coordinate system, converted using the relation ω[i+1]1(ζ[i+1]1) + v[i+1]1 = ωij(ζij) + vij. It should be noted that if the associated boundary Bij in Equation (26) is the inner boundary of the surrounding rock, then an additional term must be included on the left-hand side of the first equation. Similarly, an additional term must also be included on the left-hand side of the second equation in Equation (26), where t is the index of the stratum containing the tunnel and ϑ is the index of the stratum in the computational domain, which may take the value i or i + 1.

By assembling Equation (26) at all calculation points on the reference boundary B[i+1]1, and combining with Equations (A7), (A8) and (A17), the matrix form of the resulting system of equations is obtained.

The radial displacement uρ and circumferential displacement uθ on the interface also satisfy continuity conditions. However, because the orthogonal curvilinear coordinates have opposite orientations on the two sides of the stratum interface, uρ on one side is the negative of that on the other side, and the same applies to uθ. Using Equations (A10) and (A19), the displacement continuity equations at any calculation point on the interface are given by Equation (28).

where the boundary Bi* denotes the other independent boundary that coincides with the reference boundary Bkl. When the associated boundary Bij is the inner boundary of the surrounding rock, an additional term must be added to the left-hand side of both the first and second equations.

By assembling Equation (28) at all calculation boundary points and combining with Equations (A12), (A13) and (A21), the matrix form of the resulting system of equations can be expressed as follows.

Equations (27) and (29) can be further combined and simplified into the following form.

- (2)

- Stress conditions on the inner boundary of the concrete lining

A uniform internal pressure p0 acts along the inward normal on the inner boundary of the concrete lining, with no tangential load. Taking the inner boundary of the concrete lining Bl2 as the reference boundary, the reference local mapping coordinates ζl2 of the calculation points are determined according to the calculation point selection scheme. Using Equation (A23), the stress boundary condition equation at any calculation point can be established as follows.

By assembling Equation (31) at all calculation boundary points and combining with Equation (A24), the system of equations can be transformed into the following matrix form.

- (3)

- Interaction equations between the concrete lining and the surrounding rock

The interaction between the concrete lining and the surrounding rock is primarily considered in terms of the mechanical behavior along the normal and tangential directions of the contact surface. As shown in Table 1, this study only considers tightly bonded contact between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining in the normal direction, meaning that no initial gaps, local loose contacts, or separation due to tension exist between them. In the tangential direction, two typical mechanical behaviors are considered: smooth tangential contact, and fully bonded tangential contact. A summary of the simplified boundary condition equations corresponding to possible states of the concrete lining–rock interaction is provided in the table below. In this study, two typical extreme contact modes are considered, which provide a theoretical bounding envelope from which the plausible range of actual rock–lining interaction can be inferred. The no-slip mode is defined as being tightly bonded in the normal direction and fully bonded in the tangential direction, while the full-slip mode is characterized by tight bonding in the normal direction and smoothness in the tangential direction.

Table 1.

Boundary condition equations for possible states of concrete lining–surrounding rock interaction.

If the interaction between the concrete lining and the surrounding rock is considered as full-slip mode, taking the inner boundary of the surrounding rock as the reference boundary, the calculation points are selected and the reference local mapping coordinates are determined. Using the mechanical response formulas for strata containing tunnels and the concrete lining given in Appendix B and Appendix C, Equations (33)–(35) can be rewritten as the following boundary condition constraint equations.

By assembling the equations at all calculation boundary points and using the relevant formulas in Appendix B and Appendix C, Equations (38)–(40) can each be converted into matrix form, yielding the final system.

If the interaction between the concrete lining and the surrounding rock is considered as no-slip mode, the displacements and stresses satisfy continuity conditions. Taking the inner boundary of the surrounding rock as the reference boundary and using the mechanical response formulas for strata containing tunnels and the concrete lining from Appendix B and Appendix C, the remaining Equations (36) and (37) can be rewritten as the following constraint equations.

Using the matrix-form expressions of stress and displacement from Appendices B and C, Equations (38), (39), (42) and (43) can be converted into matrix form, yielding the following organized system.

The overall linear system varies slightly depending on the contact behavior between the composite surrounding rock and the concrete lining. The following assembles the complete linear system according to two different contact behavior modes between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining. First, for the full-slip contact mode, Equations (30), (32) and (41) are assembled to obtain the overall linear system of the vector under this contact mode as follows.

Similarly, for the no-slip contact mode, Equations (30), (32) and (44) are assembled to obtain the overall linear system as follows.

By examining the overall linear systems for the two contact modes between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining, it is evident that both have the same number of linear equations, namely 2(2n + 1)N. The number of unknowns, corresponding to the real and imaginary parts of the undetermined complex coefficients, is . Generally, the number of independent boundaries for the first and n-th strata is 1, while the t-th stratum has 3 independent boundaries. Therefore, the number of unknowns further reduces to 4s(2n + 1) + 2n + 6. According to the calculation point selection scheme, the number of calculation points N on each reference boundary satisfies N ≥ 2s + 1, so the total number of linear equations is no less than 4s(2n + 1) + 4n + 2. For a composite surrounding rock system (n ≥ 2), the total number of linear equations is thus greater than or equal to the number of unknowns. Solving Equations (45) or (46) yields all the undetermined complex coefficients for the two contact modes. Substituting these results into Equations (13) and (14) provides the Cartesian components of stress and displacement for the composite surrounding rock. Substituting into Equations (15) and (16) fully determines the Cartesian stress and displacement components of the concrete lining. This analytical procedure is implemented in a self-developed MATLAB R2022b program, enabling automatic computation from input parameters to mechanical response results.

4. Verification of the Solution Method

This section validates the proposed analytical method by means of boundary-condition checks and comparisons with numerical simulation. The verification uses a standard model with the following key parameters: the surrounding rock consists of three inclined strata, with a circular supported tunnel located entirely within the middle stratum. The concrete lining outer radius R and inner radius r are 4.0 m and 3.8 m, respectively. The vertical distance from the tunnel center to the upper stratum interface is 5 m, and to the lower stratum interface is 8 m. The stratum interface inclination angle β is 45°. From top to bottom the strata have Young’s moduli of 400 MPa, 300 MPa and 600 MPa, and Poisson’s ratios of 0.30, 0.35 and 0.30, respectively. The concrete lining has Young’s modulus 30 GPa and Poisson’s ratio 0.2. The far-field vertical normal stress is 10 MPa, the lateral pressure coefficient λ (in plane) is 1.0, and there is no far-field shear stress. The internal pressure on the concrete lining is p0 = −500 kPa (uniform inward). Two typical contact modes between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining are considered: fully-slip and no-slip.

4.1. Verification of Boundary Conditions

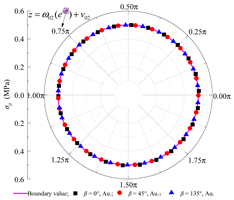

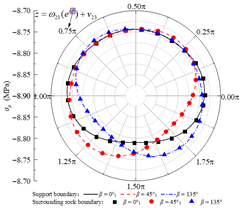

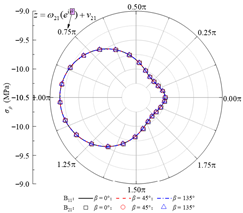

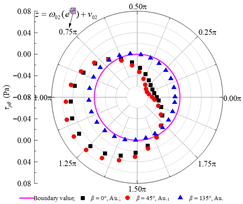

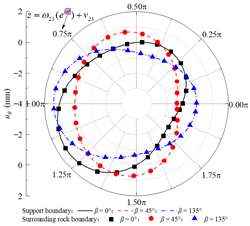

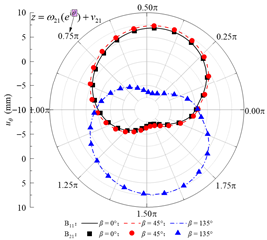

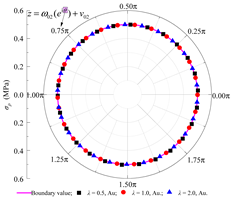

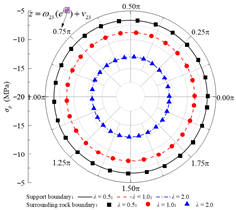

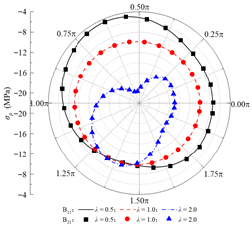

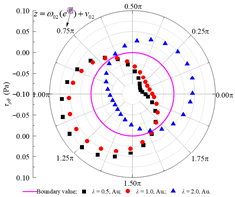

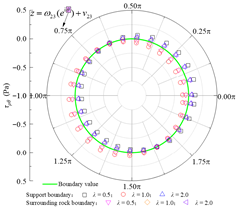

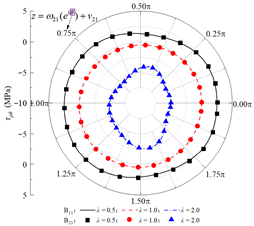

Based on the standard model, a set of models for boundary condition verification is constructed as follows: when the rock–concrete lining interface is taken as the no-slip mode, the inclination angle of the rock layers is varied; when the rock–concrete lining interface is taken as the fully-slip mode, the lateral pressure coefficient is varied. Using the analytical method proposed in this study, the orthogonal curve components of displacement and stress are calculated at the concrete lining inner boundary B02, the rock–concrete lining interface B23-B01, and the layer interfaces B21-B11. These results are used to examine whether the boundary and continuity conditions at the specified boundaries are satisfied.

Table 2 presents the calculated orthogonal curve components of stress and displacement at different boundaries under the no-slip contact mode, with rock layer inclinations of 0°, 45°, and 135°. In Table 2, θ denotes the angular coordinate of a boundary point in the corresponding reference local mapping coordinate system. It can be observed that, for all three inclination angles, the analytical solution of the normal stress σρ at the lining inner boundary nearly equals the concrete lining internal pressure P0, while the maximum absolute error of the shear stress τρθ does not exceed 0.06 Pa. This indicates that the boundary conditions are well satisfied. At the rock–concrete lining interface and the rock layer interface, the distributions of the orthogonal curve components of stress and displacement (except for circumferential normal stress) exhibit complex variations, yet the curves on both sides show high consistency, demonstrating that the analytical solution effectively satisfies the continuity conditions.

Table 2.

Verification of boundary conditions under different rock layer inclinations (no-slip contact).

In the fully-slip contact mode, the distributions of stress and displacement orthogonal curve components at different boundaries for lateral pressure coefficients of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 are shown in Table 3. It can be observed that the radial normal stress σρ at the inner boundary of the lining is essentially consistent with the internal concrete lining pressure P0, while the maximum absolute value of shear stress τρθ does not exceed 0.08 Pa, satisfying the zero-shear stress condition on the inner surface of the lining. On the rock–concrete lining interface, the maximum absolute error of shear stress on both sides does not exceed 0.25 Pa, which is negligible compared to the stress level of 107 Pa for the normal stress at the same location, fulfilling the theoretical requirement of zero shear stress at the interface. In addition, at the rock–concrete lining interface and the rock layer interfaces, the analytical results of radial displacement, circumferential displacement, radial normal stress, and shear stress remain consistent, indicating that the continuity conditions of stress and displacement are satisfied.

Table 3.

Verification of boundary conditions under different lateral pressure coefficients (fully-slip contact).

In summary, under different rock–concrete lining contact modes, rock layer inclinations, and lateral pressure coefficients, the verification results show that the boundary and continuity conditions are well satisfied, confirming the correctness and applicability of the analytical method presented in this study.

4.2. Numerical Validation

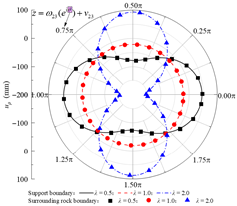

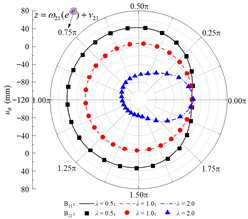

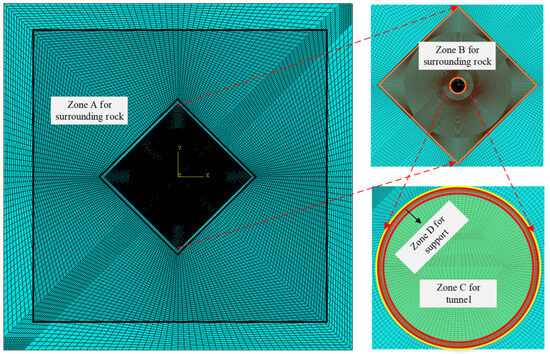

This section presents a comparative analysis between analytical and numerical solutions to further verify the correctness of the proposed analytical method. Figure 3 shows the geometric model after tunnel excavation. The main parameters of the model remain consistent with those of the standard model, except that the lateral pressure coefficient in and out of the plane is set to 1.5 to establish a deeply buried non-hydrostatic stress field for evaluating the performance of the analytical method. The rock–concrete lining interface is considered under both no-slip and fully-slip contact modes.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the geometric model for excavation of a deeply buried supported tunnel.

Based on the geometric model shown in Figure 3, a numerical simulation model was constructed in ABAQUS/CAE 2020 as shown in Figure 4. The overall model size is 200 m by 200 m, with the tunnel center as the model center. The model comprises three stratified layers, the tunnel excavation region, and the concrete lining structure. The outer region of the layered strata was meshed with 12,333 CPE4 elements, the refined region with 410,348 CPE4 elements, the tunnel excavation region with 5946 CPE4 elements, and the concrete lining structure with 3720 CPE4 elements. The entire model contains 432,347 CPE4 plane strain elements and 435,656 nodes. To ensure computational accuracy while controlling mesh size, the numerical model was partitioned by mesh density into rock zone A enclosed by black lines, rock zone B enclosed by orange lines, tunnel zone C enclosed by yellow lines, and concrete lining zone D enclosed by red lines. The approximate element sizes in these regions are 1.00, 0.10, 0.10, and 0.04 m respectively. The built-in TIE command was used to tie the layered strata and the interfaces between regions with different mesh densities, enabling analysis of the nonconforming mesh model.

Figure 4.

Plane strain numerical model.

The simulation process is divided into three analysis steps, Initial, Balance, and Excavation. The main procedure is as follows.

In the Initial step, a prestress field is applied with σx = −1.5 × 107 Pa, σy = −1.0 × 107 Pa, and σz = −1.5 × 107 Pa, with all shear stress components set to zero.

In the Balance step, the built-in “Model Change” command is used to deactivate the concrete lining elements. Boundary conditions constrain the vertical and horizontal displacements on the top, bottom, left, and right boundaries, with the built-in Geostatic analysis procedure employed to equilibrate the initial stress field and reset the displacements.

In the Excavation step, the “Model Change” command is used to deactivate the tunnel excavation elements and reactivate the concrete lining elements. A normal inward pressure P0 is applied on the inner boundary of the concrete lining. The contact between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining is defined as follows. For no-slip contact, the built-in “TIE” command is used to establish the interface. For fully-slip contact, a surface-to-surface contact command is employed. The model is then solved to obtain the final numerical results.

To prevent rigid body rotation of the concrete lining under smooth contact conditions, a reference point is defined at the tunnel center. The built-in “Coupling” command is used to constrain the reference point with the inner and outer boundaries of the concrete lining, while restricting its rotational degrees of freedom in the plane.

In the Excavation analysis step, the simulation values of Mises stress, horizontal displacement, and vertical displacement are extracted along measurement paths including circular paths around the surrounding rock at 1~5 times the tunnel diameter, as well as along the outer surface, central plane, and inner surface of the concrete lining. The corresponding stress and displacement analytical solutions are then calculated at the same locations, providing a basis for comparative analysis between the numerical simulation results and the analytical solutions.

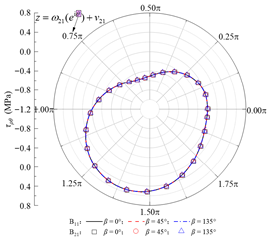

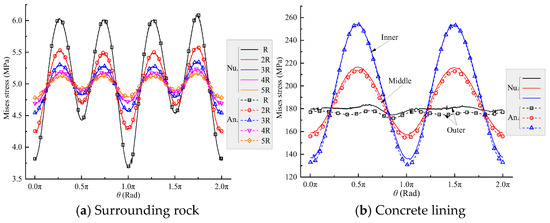

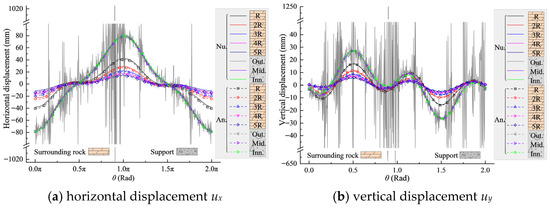

Figure 5 presents the comparison between numerical and analytical results of Mises stress in the surrounding rock and concrete lining along different measurement lines under no-slip contact at the rock-concrete lining interface. As the von Mises stress incorporates the combined effect of all stress components at a point, it provides a concise and efficient indicator for assessing the overall accuracy of the proposed analytical method across multiple comparison paths. Figure 5a shows that both methods exhibit periodic fluctuations of Mises stress with respect to the angular position θ, and the stress magnitudes and variation patterns are highly consistent. Notably, when the measurement line crosses the interlayer interface, both numerical and analytical solutions display step changes in Mise’s stress, with the most pronounced step observed near θ = 1.0π along the 1D-diameter path. This comparison indicates that the analytical method accurately captures the stress distribution characteristics of stratified surrounding rock under fully bonded contact conditions and aligns well with the numerical simulation results. Figure 5b shows that along the concrete lining inner surface, outer surface, and mid-surface, the distribution patterns of Mises stress from both methods are highly consistent, with stress peak and valley positions and relative magnitudes essentially identical, demonstrating that the analytical method effectively reflects the main stress features in the concrete lining. It should be noted that slight differences exist on the concrete lining outer surface and mid-surface, but the overall relative error is small, with a maximum not exceeding 3%, likely due to insufficient discretization near the interface caused by a large stiffness contrast between the rock and concrete lining.

Figure 5.

Comparison of numerical and analytical results of Mises stress along measurement lines under no-slip contact mode.

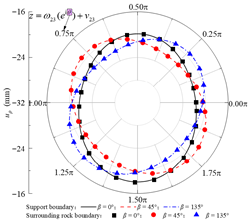

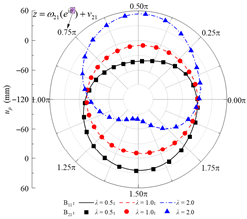

Figure 6 presents the comparison between numerical and analytical results of displacement components along different measurement lines under no-slip contact at the rock-concrete lining interface. Figure 6a shows that the numerical simulation yields horizontal displacement distributions along all measurement lines with a pattern of two valleys at the sides and a single peak in the middle with respect to the angular position θ. The analytical solution closely matches the numerical results in terms of overall distribution, variation trend, and the positions and magnitudes of extreme values. It should be noted that the numerical results for horizontal displacement on the concrete lining outer surface exhibit large oscillations around the correct values, with maximum amplitudes on the order of 1 m. This is likely due to the large stiffness contrast between the surrounding rock and the concrete lining and insufficient mesh refinement on either side of the interface. Further mesh refinement might reduce or eliminate these oscillations, but at the cost of significantly increased computational scale. In contrast, the analytical solution provides continuous and stable results, demonstrating the method’s accuracy and stability even in regions with drastic stiffness changes. Figure 6b shows that the vertical displacement distributions along all eight measurement lines from both numerical and analytical solutions almost perfectly overlap, with consistent patterns and displacement errors within 0.2 mm. The numerical vertical displacement on the concrete lining outer surface also exhibits abnormal oscillations, with a maximum of 1250 mm, whereas the analytical solution shows no such oscillations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of displacement along different measurement lines under no-slip contact mode.

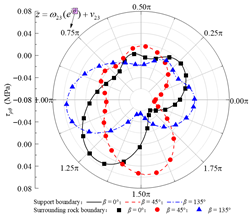

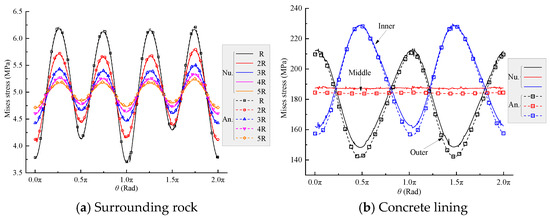

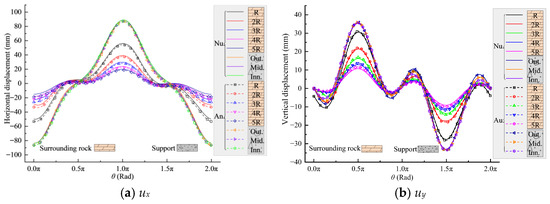

After adjusting the contact condition at the rock-concrete lining interface to fully-slip contact, the comparison of Mises stress along each measurement line is shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a shows that the Mises stress along the rock measurement lines varies with the polar angle θ in a stable periodic manner and gradually decreases with increasing radius. The analytical and numerical results agree well in terms of peak and valley positions and magnitudes, with only minor differences near extreme values, and the overall stress error remains within 0.03 MPa. Additionally, if the measurement line crosses a layer interface, local stress jumps related to material parameter differences are still observable, which are accurately captured by the analytical solution. Figure 7b shows that the numerical results indicate that the Mises stress on the concrete lining inner and outer surfaces exhibits nearly opposite-phase distribution, while the fluctuation amplitude at the mid-surface is significantly reduced, consistent with the mechanical feature of tangential stress release under smooth contact. The analytical solution predicts the Mises stress distribution along the three measurement lines on the concrete lining in complete agreement with the numerical simulation, with overall stress magnitudes closely matching, and only minor differences at extreme stresses and at the mid-surface, with a maximum relative error of no more than 4%.

Figure 7.

Comparison of numerical and analytical Mises stress along various measurement lines under fully-slip contact conditions.

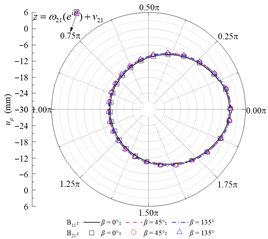

Figure 8 shows the comparison between numerical and analytical displacement results along various measurement lines under fully-slip contact conditions. The numerical and analytical results for both horizontal and vertical displacements are completely consistent in terms of curve distribution and variation trends, with the curves nearly overlapping. This indicates that the analytical method accurately predicts displacements under the fully-slip contact mode and agrees well with the numerical simulations. A careful observation shows that, unlike the no-slip contact mode, no oscillations appear in the displacement numerical results under the fully-slip contact mode, further confirming that the analytical model’s predictions of horizontal and vertical displacements on the concrete lining outer surface are in excellent agreement with the numerical simulations.

Figure 8.

Comparison of numerical and analytical displacement results along various measurement lines under fully-slip contact conditions.

In summary, under both no-slip and fully-slip contact modes at the rock-concrete lining interface, the analytical method proposed in this study produces predictions of Mises stress and horizontal and vertical displacements along all measurement lines that are highly consistent with numerical simulations. Under the no-slip contact mode, the analytical solution provides more stable and accurate displacement predictions at the rock-concrete lining interface compared with numerical results. The above comparative analysis fully validates the correctness, stability, and applicability of the proposed analytical method.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the mechanical response of deeply buried tunnels with concrete lining in parallel inclined multilayered rock masses. A plane-strain analytical model incorporating both no-slip and fully-slip rock–lining interface conditions is developed, and explicit stress–displacement solutions are derived using a non-iterative complex variable function method. Boundary-condition checks and numerical comparisons are performed to validate the proposed analytical framework. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The analytical model effectively captures the complex mechanical characteristics arising from the differing properties of arbitrarily inclined multilayered rock strata. This departs significantly from conventional approaches that treat the surrounding rock as a single homogeneous medium. The model also incorporates the concrete lining and considers two typical extreme interface conditions between the lining and the rock—no-slip and fully-slip. By applying the non-iterative complex variable function theory, explicit stress and displacement solutions are obtained. These solutions enable efficient and accurate analysis of the coupled mechanical response of inclined multilayered rock and concrete lining structures in multiply connected domains with multiple planar boundaries.

- (2)

- Comprehensive boundary condition checks under varying contact modes, rock layer inclinations, and lateral pressure coefficients indicate that the stress calculation error on the inner surface of the concrete lining remains on the order of 10−2 Pa. The stress and displacement component curves on both sides of the rock–concrete lining and rock layer interfaces closely coincide, demonstrating that the proposed method effectively satisfies all boundary and continuity conditions.

- (3)

- Comparisons with numerical simulations under non-hydrostatic stress fields show that the analytical predictions of von Mises stress and displacement agree closely with FEM results. Stress errors are generally below 0.03 MPa, displacement errors remain under 0.2 mm, and the maximum relative error of von Mises stress does not exceed 4%. The analytical method also accurately captures stress jumps at rock–layer interfaces and avoids the numerical oscillations typically caused by large stiffness contrasts, demonstrating strong stability and reliability.

The proposed analytical framework provides potential engineering value by offering rapid estimates of stress redistribution and deformation tendencies in multilayered geological conditions. Such capabilities can support the early-stage identification of unfavorable loading scenarios and assist preliminary design considerations. In addition, the explicit formulation of stress and displacement offers a basis for extended applications, such as conducting parameter sensitivity studies or examining the influence of stratigraphic stiffness contrast, layer inclination, and interface behavior under various loading conditions.

Nevertheless, the model involves several simplifications that may affect its applicability in complex settings. Material behavior is idealized as homogeneous and isotropic linear elasticity, and the rock–lining interaction is represented only by two limiting interface conditions—fully-slip and no-slip. Future work will incorporate more realistic partial-slip or frictional interface relationships and more advanced material descriptions, such as anisotropic, viscoelastic, or time-dependent behaviors, to enhance the model’s relevance to practical engineering conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H., P.L. and Z.Z.; methodology, P.L. and Y.X.; software, H.L.; validation, H.L.; formal analysis, H.L. and Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.; resources, X.H. and Z.Z.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.; writing—review and editing, P.L., H.L., Z.Z., Y.X. and Z.D.; visualization, X.H. and H.L.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, X.H.; funding acquisition, X.H., P.L. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Project Foundation of the Key Laboratory of Urban Underground Engineering of Ministry of Education (Beijing Jiaotong University) (Grant No. TUL2024-08); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52504134), and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFF1700905); Science and Technology Major Project of Tibetan Autonomous Region of China (XZ202201ZD0003G).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xuefei Hong, Peng Lin and Haiyan Liu were employed by the Department of Hydraulic Engineering, Tsinghua University. Author Zongliang Zhang was employed by the Power Construction Corporation of China. Author Yong Xia was employed by the company Power China Chengdu Engineering Co., Ltd. Author Zhiyun Deng was employed by Sichuan Energy Internet Research Institute, Tsinghua University. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Z | Global physical coordinate system XOY; |

| z x + iy | Global physical coordinate in XOY; |

| Bij | The j-th independent boundary of the i-th inclined stratum; |

| Zij | Local physical coordinate system of Bij; |

| zij | Local physical coordinate in Zij; |

| ζij | Local mapping coordinate of zij using the conformal mapping function; |

| ωij | Conformal mapping function for Bij; |

| λij | Mapping scaling factor; |

| β | Inclination angle of parallel inclined multi-layered surrounding rocks; |

| Φij(zij), Ψij(zij) | The set of analytic complex potential functions for Bij; |

| φij(ζij), ψij(ζij) | Laurent series expansions of Φij(zij), Ψij(zij) in the mapped plane; |

| aij,0, aij,k, bij,0, bij,k | Undetermined complex coefficients in φij(ζij), ψij(ζij); |

| Ei, μi | Elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the i-th stratum; |

| El, μl | Elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the concrete lining; |

| Gi | Shear modulus of the i-th stratum, ; |

| κi | Material parameter of the i-th stratum, ; |

| R, r | Outer and inner diameters of the concrete lining; |

| P∞, τ∞ | Cartesian components of far-field stresses; |

| λ | Lateral pressure coefficient; |

| Polar components of far-field stresses; | |

| p0 | Normal inward pressure on the inner boundary of the concrete lining; |

| Cartesian components of stresses in the i-th stratum; | |

| Cartesian components of displacements in the i-th stratum; | |

| Polar components of stresses in the i-th stratum; | |

| Polar components of displacements in the i-th stratum; | |

| Cartesian components of stresses in the concrete lining; | |

| Cartesian components of displacements in the concrete lining; | |

| Polar components of stresses in the concrete lining; | |

| Polar components of displacements in the concrete lining. |

Appendix A

First, the undetermined complex coefficients are expressed in vector form. For any independent boundary, the vector of undetermined complex coefficients is expressed as follows.

where are all vectors composed of the real and imaginary parts of the complex coefficients. For example, .

The vector of undetermined complex coefficients for the i-th stratum is shown in Equation (A2).

The vector of undetermined complex coefficients for the support structure is shown in the Equation (A3).

The overall vector of undetermined complex coefficients is shown in the Equation (A4).

Taking boundary Bkl as the reference boundary, consider any e points on path B in the i-th stratum without a tunnel, corresponding to the global physical coordinate vector . Substituting Equations (10) and (17) into Equation (21) yields the expression of the orthogonal curvilinear stress components of the composite surrounding rock at the point set along path B as shown in Equation (A5).

where the vector is the local mapping coordinate vector corresponding to the global coordinate vector , converted using the formula . Similarly, the vector is the local mapping coordinate vector of the global coordinate vector along path B, computed through the same relation . Let be a vector defined with respect to the local mapping coordinate vector , whose elements are determined by a function based on the corresponding element values . this convention applies throughout the study. I denotes a vector or matrix with all elements equal to 1. Stress-type functions f and g are defined corresponding to the a-type and b-type undetermined complex coefficients, respectively. For example, the superscript Bkl of the function indicates the reference boundary, the superscript σρ indicates that the function is determined from the orthogonal curvilinear component σρ, and the subscript ij,k refers to the coefficient index. When the associated boundary Bij is an outer boundary such as a stratum interface or the outer boundary of the support, the stress-type f and g functions are expressed as follows.

where the conformal mapping functions and their derivatives of all orders are written with the independent variable omitted. For example, ωij(ζij) and ω (ζ) are simplified as ωij and ω, respectively.

Equation (A5) can be further rewritten in terms of the unknown complex coefficient vector as follows.

where , and are all coefficient matrices of vector , and their expressions are as follows.

Among them, O denotes a matrix or vector with all elements equal to zero. The coefficient matrix corresponding to vector can be expressed as follows.

Similarly, substituting Equations (10) and (17) into Equation (23) yields the expressions for the orthogonal curvilinear displacement components of the composite surrounding rock at the set of points can be obtained from the Equation (A10).

where and with reference to the stress conditions, displacement-type functions f, and are defined, corresponding, respectively, to the a-type, b-type and c-type unknown complex coefficients. For the case where the associated boundary Bij is the outer boundary of the surrounding rock and the support, these functions are given by the following Equation (A11).

Similarly, rewrite Equation (A10) in the following form in terms of the vector of undetermined complex coefficients.

The expressions of the coefficient matrices of vector in this equation are as follows.

The coefficient matrix corresponding to vector can be expressed as the following the Equation (A14).

Appendix B

Taking boundary Bkl as the reference boundary, consider any e points on path B in the t-th stratum containing a tunnel. Substituting Equations (10), (11) and (17) into Equation (21) yields the expression for the orthogonal curvilinear stress components of the composite surrounding rock at the point set along path B as the following Equation (A15).

where when j ≠ mt, the stress-type functions f and g are calculated in the same manner as in Equation (A6). When j = mt (generally, mt = 3), the corresponding stress-type functions f, , and g are calculated as follows.

The matrix-form expression of Equation (A15) is the same as Equation (A7), where the coefficient matrix of vector can be expressed with reference to Equation (A8) as the Equation (A17).

where, when j ≠ mt,, the coefficient matrix is given by Equation (A9). When j = mt, the coefficient matrix has the following new expression.

Substituting Equations (10), (11) and (17) into Equation (23) yields the expressions for the orthogonal curvilinear displacement components of the composite surrounding rock at the set of points.

where, when j ≠ mt, the displacement-type functions f, , and are calculated in the same manner as in Equation (A11). When j = mt, the corresponding displacement-type functions f, , and are calculated as follows.

The matrix-form expression of Equation (A19) is the same as Equation (A12), where the coefficient matrix of vector can be expressed with reference to Equation (A13) as follows.

where, when j ≠ mt, the coefficient matrix is given by Equation (A14). When j = mt, the coefficient matrix has the following new expression.

Appendix C

Taking boundary Bkl as the reference boundary, consider any e points on the support structure along boundary Bkl. Substituting Equations (10), (11) and (17) into Equation (24), and noting that the support structure necessarily includes an inner boundary, the orthogonal curvilinear stress components of the support at the point set, related to the boundary conditions, are given with reference to Equation (A15) as follows.

where the stress-type functions f, , and are the same as those in Equation (A15).

After simplification, the matrix-form expression with respect to the vector can be written as follows.

where the coefficient matrix of vector and the corresponding coefficient matrix are calculated in the same way as in Equation (A17).

Similarly, substituting Equations (10), (11) and (17) into Equation (25), and with reference to Equation (A19), the orthogonal curvilinear displacement components of the support at the point set, related to the boundary conditions, are expressed as follows.

where the displacement-type functions f, , and are the same as those in Equation (A19). With reference to Equation (A12), the above expression can be written in matrix form with respect to the vector as follows.

where the coefficient matrix of vector and the corresponding coefficient matrix are calculated in the same way as in Equation (A21).

References

- Deng, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; de la Fuente, A.; Han, Y.; Xiong, F.; Peng, H. Field monitoring of mechanical parameters of deep-buried jacketed-pipes in rock: Guanjingkou water control project. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 125, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Liu, X.; Han, Y.; Ding, P.; Xu, B.; Du, W. Study on the field monitoring, assessment and influence factors of pipe friction resistance in rock. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 154, 106053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Huang, H.; Zhong, M.; Wang, H.; Hua, F. Monitoring and early warning mechanism of flood invasion into subway tunnels based on the experimental study of flooding patterns. J. Intell. Constr. 2024, 2, 9180011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.M.; Chen, S.J.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.N.; Zhang, J.R. Determination of the rock mass bearing mechanism following excavation of circular tunnels in layered surrounding rock. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 164, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, J.H.; Huang, H.W.; Ai, Z.Y.; Chen, J.Y. Analytical model for tunnel face stability in longitudinally inclined layered rock masses with weak interlayer. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 143, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.Y.; Zhu, Z.D.; Qu, S.; He, L.K.; Zeng, H.Y.; Zhang, C.X.; Tian, Y. Anisotropic characteristics and deformation behaviors of layered rocks surrounding tunnel: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025. in Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Chen, P.; de la Fuente, A.; Ren, L.; Du, L.; Han, Y.; Xiong, F.; et al. Main engineering problems and countermeasures in ultra-long-distance rock pipe jacking project: Water pipeline case study in Chongqing. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 123, 104420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; He, B.-G.; Meng, X.-R.; Guan, J.-H.; Xu, H.-W. Wave-absorbing grouting for mitigating rockbursts triggered by multi dynamic disturbances in deep tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 168, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.Z.; Tan, F.Y.; Li, F.Q.; Chi, F.D.; Liu, X.F.; Wang, Z.F. A three-dimensional numerical study on the stability of layered rock spillway tunnels in alpine canyon areas. Deep Resour. Eng. 2024, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ren, F.Q.; Chang, Y. Effect of bedding angle on tunnel slate failure behavior under indirect tension. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2020, 11, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, E.; Tilahun, K.; Assefa, S.M.; Jilo, N.Z.; Pantelidis, L.; Sachpazis, C. Stability evaluation of tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock mass using numerical models: A case study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xia, H.; Qin, D.; Luo, J. Tunnel entrance crossing spoil heap deformations control by micropile combine with coupling beams. Geohazard Mech. 2024, 2, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisova, E.V.; Khmelinin, A.P.; Sokolov, K.O.; Konurin, A.I.; Voitenko, A.A. Complex analysis of GPR signals to control contact zone of concrete lining and rock mass. Geohazard Mech. 2025, 3, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Lan, W.; Da, Y.; Hu, K. Intelligent recognition of voids behind tunnel linings using deep learning and percussion sound. J. Intell. Constr. 2023, 1, 9180029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; He, M.; Li, G. Viscoelastic solution of optimal reserved deformation for deep soft rock tunnels with large deformation. Geohazard Mech. 2024, 2, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Liang, N.; Liu, X.; de la Fuente, A.; Lin, P.; Peng, H. Analysis and application of friction calculation model for long-distance rock pipe jacking engineering. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 115, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, Q.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G.; He, Y.; Li, W. Development and engineering application of intelligent management and control platform for the shield tunneling construction close to risk sources. J. Intell. Constr. 2024, 2, 9180018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tao, L.J.; Ding, P.; Wang, Z.G.; Jia, Z.B.; Shi, M. Analytical solution for deep non-circular tunnels considering slippage effects under far-field seismic SV waves. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 144, 105552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.T.; Wang, H.N.; Jia, X.C. New analytical solutions for stress and displacement in deeply buried noncircular tunnels incorporating the influence of seepage flow. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 142, 115990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Peng, Y. Analytical method for the vertical response of existing shield tunnel induced by above-crossing multiple parallel pipe jacking. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 165, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskhelishvili, N.I. Some Basic Problems of the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity; Noordhoff: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, A.Z.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.J.; Zhang, X.L. Analytical Solution for a Lined Tunnel with Arbitrary Cross Sections Excavated in Orthogonal Anisotropic Rock Mass. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04017044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabe Fogang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.L.; Ka, T.A.; Xu, S. Analytical Prediction of Tunnel Deformation Beneath an Inclined Plane: Complex Potential Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verruijt, A. A Complex Variable Solution for a Deforming Circular Tunnel in an Elastic Half-Plane. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1997, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.Y.; Pan, Y.X.; Ye, Z.K.; Wang, D.S. Stress and Displacement Fields of Elliptical Tunnels in Fractional Order Viscoelastic Transversely Isotropic Medium. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2025, 1, 3917–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Xu, B.S.; Yuan, Y. A Closed-Form Elastic Solution of Ground Response Curve for Noncircular Openings. Int. J. Geomech. 2021, 21, 04021235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.B.; Zhang, C.P.; Cai, Y.; Min, B. Complex Analysis of Ground Deformation and Stress for a Shallow Circular Tunnel with a Cavern in the Strata considering the Gravity Condition. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4141–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.L.; Xu, T.; Fang, H.C.; Fang, Q.; Cao, L.Q.; Wen, M. Analytical modeling of complex contact behavior between rock mass and lining structure. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.C.; Wang, H.N.; Song, F.; Rodriguez-Dono, A. Theoretical analysis of stresses and displacements of twin tunnels excavated in saturated ground. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 50, 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.S.; Wang, H.N.; Wu, L.; Jiang, M.J. A Generalized Analytical Model for Mechanical Responses of Rock during Multiple-Tunnel Excavation in Viscoelastic Semi-Infinite Ground. Int. J. Geomech. 2021, 147, 04021051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.S.; Wang, H.N.; Jiang, M.J. Analytical stress and displacement of twin noncircular tunnels in elastic semi-infinite ground. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 160, 105520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.T.; Wang, H.N.; Song, F.; Jia, X.C. Analytical solutions for lined noncircular tunnels in deep ground considering hydromechanical coupling. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, H.N.; Jiang, M.J.; Hu, T. A semi-analytical approach for the stress and displacement around lined circular tunnels at shallow depths. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 27, 3449–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.T.; Chen, G. Pseudo-static simplified analytical solution for seismic response of deep tunnels with arbitrary cross-section shapes. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 137, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yu, H.T.; Bobet, A. Analytical Solution for Seismic Response of Deep Tunnels with Arbitrary Cross-Section Shape in Saturated Orthotropic Rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2022, 55, 5863–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Fang, Q.; Wen, M. A generalized complex variable method for multiple tunnels at great depth considering the interaction between linings and surrounding rock. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 129, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Wen, M.; Hu, X.Y. A non-iterative analytical method for mechanical analysis of surrounding rock with arbitrary shape holes. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2020, 39, 2204–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Huang, C.J.; Fang, Q.; Zhou, M.Z.; Cao, L.Q. Analytical method for mechanical analysis of multiple shallow tunnels with concrete linings. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 116, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Fang, Q. A semi-analytical method for frictional contact analysis between rock mass and concrete linings. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 105, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, H.C.; Jiang, A.N.; Zhang, D.L.; Fang, Q.; Lu, T.; Bai, J.R. Mechanical behaviours of existing tunnels due to multiple-tunnel excavations considering construction sequence. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.F.; Zhang, D.L.; Sun, Z.Y. Mechanical responses of multi-layered ground due to shallow tunneling with arbitrary ground surface load. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2023, 17, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.L.; Fang, H.C.; Hong, X.F. Generalized complex variable analysis of shallow tunneling through multi-layered ground. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 125, 230–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).