Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of a fine-tuned generative AI system—trained with a domain question bank—for question generation and automated grading in programming education, and evaluates its instructional usability. Methodologically, we constructed an annotated question bank covering nine item types and, under a controlled environment, compared pre- and post-fine-tuning performance on question-type recognition and answer grading using Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1. We also collected student questionnaires and open-ended feedback to analyze subjective user experience. Results indicate that the accuracy of question-type recognition improved from 0.6477 to 0.8409, while grading accuracy increased from 0.9474 to 0.9605. Students’ subjective perceptions aligned with these quantitative trends, reporting higher ratings for grading accuracy and question generation quality; overall interactive experience was moderately high, though system speed still requires improvement. These findings provide course-aligned empirical evidence that fine-tuning with domain data can jointly enhance the effectiveness and usability of both automatic question generation and automated grading.

1. Introduction

In recent years, advances in Generative AI (GenAI) have driven innovations in educational technology. UNESCO’s Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research explicitly notes that GenAI will profoundly reshape how knowledge is produced and accessed. The report also emphasizes that before adopting GenAI in education, institutions should uphold a human-centered principle and establish rigorous ethics and quality-assurance mechanisms to prevent the instrumentalization of educational values and the propagation of misinformation that could harm learning [1]. For example, in educational applications, Large Language Models (LLMs) show potential for automatically generating questions, instructional materials, and learning resources; however, their outputs often exhibit “hallucination,” namely information that appears plausible yet is factually incorrect [2,3]. This poses a clear warning for education, as erroneous materials or exercises can directly lead learners to form misconceptions. In domains requiring strict informational accuracy, such as education and healthcare, such errors are particularly consequential [4].

Programming courses are widely regarded as foundational in computing education, and the C language remains a core component of many universities’ “Introduction to Computer Science” offerings [5]. Renowned for structural rigor and logical clarity, C demands abstract thinking and problem-solving skills while requiring correctness in program logic. To support the acquisition of these skills, classroom lectures alone are insufficient; extensive practice and hands-on activities are essential. Yet designing a question bank that is diverse in content, progressively scaffolded in difficulty, and tightly aligned with the syllabus is highly time-consuming and labor-intensive for instructors [6]. Empirical work shows that even when using the GPT-3.5 API to batch-generate 120 programming questions, only 21% were directly usable; most contained errors or required substantial revision [7]. Another defect taxonomy study on LLM-generated code reported common issues such as semantic misunderstandings, missing boundary conditions, incorrect input types, hallucinations, inconsistent API objects, and incomplete code generation [8]. In addition, researchers have noted that existing programming evaluation datasets often lack sufficient test cases, creating an illusion whereby faulty programs appear to pass testing [9]. These limitations imply that, even with AI-assisted question generation, substantial human review is still required, undermining the value of “automation.”

Thus, although LLMs demonstrate cross-domain generative capabilities and can rapidly produce diverse content, their application in educational settings remains constrained. First, the generation process is frequently accompanied by hallucination, producing information that conflicts with course materials or is simply incorrect [2]. In programming education, this issue is especially acute, for instance when models generate nonexistent libraries, syntactically invalid code, or answers that ignore boundary conditions [8,10]. Second, general-purpose models lack awareness of course syllabi and learning objectives, and may therefore generate tasks that exceed curricular scope or misalign with learners’ developmental stages, leading to frustration and misdirection [11]. Third, although prompt engineering can partially adjust difficulty, models struggle to maintain consistency and stability when producing items across multiple difficulty levels over time [11,12]. Finally, quality checks for AI-generated questions have largely relied on the perspective of teachers or researchers alone, overlooking learners’ lived experiences and the potential for AI self-checking. This can yield partial evaluations and bias [13,14,15].

Given these constraints, judging whether GenAI or LLMs can adequately support question generation and grading in programming education based solely on individual cases or small samples risks over- or under-estimating their true effectiveness. More importantly, different item types embed distinct cognitive processes and scoring mechanisms—for example, the single-solution nature of closed-ended questions, the executability and multiplicity of solutions in coding tasks, and the dependence of debugging items on boundary conditions and semantic interpretation. As a result, a model’s performance may diverge fundamentally across item types. Without a systematic, item-type-sensitive comparison, it is difficult to provide actionable evidence for instructional decision-making. Moreover, model performance in generation and grading is jointly shaped by interactions among the in-domain or out-of-domain distribution of training data, fine-tuning strategies (e.g., instruction tuning and alignment), inference parameters (e.g., temperature and top-p), prompt design (e.g., few-shot and chain-of-thought), and evaluation protocols (e.g., whether tool use is allowed and whether execution-based evaluation is employed). If the practical influence of these methodological and control parameters is not clarified, it is difficult to establish reproducible and scalable pipelines for instructional automation.

Building on the above research gaps, this study proposes an integrated evaluation and implementation route. First, we construct a standardized dataset that covers nine item types—single-choice, fill-in-the-blank, multiple-choice, true–false, code fill-in, debugging, full-program tasks, matching, and short-answer—and collect diverse response samples (correct, incorrect, partially correct, ambiguous) to support learning the distinct features of item types and their grading logics. Technically, we adopt GPT-4o as the base model and conduct multi-round fine-tuning with cross-validation, while introducing an iterative data feedback loop to improve robustness across three facets: question-type recognition, difficulty estimation, and grading consistency. Under a standardized environment, we then perform paired evaluations of the original versus fine-tuned models on the same item sets and protocols for two tasks—question generation and answer grading—quantifying performance with Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1.

In sum, this study builds a multi-type training dataset and applies fine-tuning to optimize a generative AI model, followed by a systematic assessment of performance across item types to verify feasibility and effectiveness for programming instruction. We articulate three core objectives as research questions and explain their necessity and applied significance as follows.

- RQ1: Do large language models exhibit systematic differences in generation and grading performance across item types, and what is the structure of those differences?

Item type determines the structure of valid answers, the degree of decisiveness in scoring, and the sensitivity to boundary conditions. From closed-ended items to executable programming tasks, scoring mechanisms and error patterns differ markedly. Without using item type as the unit of analysis, a single aggregate metric can mask critical differences and mislead instructional decisions. Some item types may be suitable for priority automation, whereas others may require retained human review. Focusing explicitly on item-type differences enables an actionable capability profile and risk map to guide course adoption and resource allocation.

- RQ2: What practical influence do model-training and inference designs—such as fine-tuning strategies, prompt design, sampling and decoding parameters, and execution-based evaluation conditions—have on generation and grading performance?

In applied settings, performance gains often arise jointly from the base model and parameter choices. Without disentangling these factors, it is impossible to identify which designs are repeatable and scalable. Addressing this question clarifies the quality–cost relationship and yields concrete optimization guidelines that help reach instructional usability thresholds under limited resources while maintaining stability, consistency, and operational feasibility.

- RQ3: Are the quantitative performance patterns consistent with users’ perceived effectiveness and usability, and how do these two sources jointly define adoption conditions and governance principles in practice?

Quantitative metrics alone do not guarantee instructional adoption. Teachers’ and learners’ subjective judgments of question quality, grading trustworthiness, interaction experience, and difficulty appropriateness determine actual uptake and sustained scaling. By linking objective performance with perceived usability, this question extracts the process specifications and governance mechanisms needed for deployment—alignment with curriculum and units, difficulty banding, scoring consistency, and avenues for appeal—to delineate when the system may operate autonomously and when human oversight must be invoked, ensuring that technical capability translates into a sustainable instructional practice.

2. Related Work

2.1. Question Generation for Programming

A primary challenge in programming instruction lies in the diversity of learners’ needs and abilities. Because students progress at different rates, they often approach the same problem with different understandings and solution strategies. Traditional teaching models struggle to respond flexibly to such variability, making it difficult for instructors to provide timely and targeted support for individual learners. As educational demand becomes more diverse and scaled—particularly with the rise of massive open online courses (MOOCs)—this challenge grows more pronounced. Educators must not only supply appropriate learning resources for heterogeneous needs but also generate and automatically grade large volumes of work rapidly, making automated question generation and grading systems a key part of the solution.

The original intent of automated question generation is to reduce instructors’ workload in item authoring, grading, and timely feedback. A substantial body of literature highlights its advantages in lowering authoring costs and improving instructional efficiency [7,16,17]. For example, studies report that automated systems not only shorten item design time but also meet the volume requirements for high-quality questions in MOOCs and adaptive learning systems [15]. With advances in AI, the precision and adaptivity of automatic generation have improved, enabling the creation of appropriately challenging questions tailored to learner levels and boosting learning outcomes and engagement [17,18,19,20]. Existing techniques often rely on syntax and semantic processing as well as template-based methods, each with trade-offs. Template-based approaches, while easier to implement, can be limited in linguistic variety and may not satisfy learners’ higher demands for language comprehension [15]. Some work leverages large language models such as OpenAI Codex to generate programming problems and code explanations, raising quality and interest; however, concerns remain about correctness and diversity, and the accuracy of generated content can be affected by model bias [7].

To address heterogeneity, adaptivity has received increasing attention within automated generation systems. For instance, a programming exercise generator can adjust difficulty according to student progress and verify solutions using automatically generated test data. Such systems have been shown to help learners deepen their understanding of programming concepts incrementally [16]. Other studies embed automated generation in educational platforms via neural language generation to improve diversity and adaptivity, while providing immediate feedback to enhance learning [18].

Despite these advances, key challenges persist, including accuracy of generated items, diversity of content, and insufficient adaptivity across proficiency levels. Studies note that LLM-generated content can suffer from grammatical and semantic inaccuracies; in code explanations, errors often arise from misinterpreting conditionals or comparison operators, potentially misleading learners [7]. Moreover, many systems lack principled control over distractors, resulting in weaknesses in grammatical correctness and item variety that call for further optimization [15]. Although ongoing progress in AI and NLP may mitigate these issues, recent work on an intelligent model for automatically generating code-tracing questions—implemented as a Moodle plugin (CodeCPP)—showed that it can substantially reduce instructors’ preparation time for large classes and ensure equivalent difficulty across versions. It can also reduce opportunities for cheating and support immediate feedback; however, it requires instructors to possess technical skills to configure templates and editing rules, and still relies on human intervention during evaluation [21].

Beyond conventional question-generation approaches, research on learning problem generation (LPG) provides a broader perspective relevant to programming tasks such as debugging and full-program construction. LPG methods focus on generating structured learning problems by encoding domain constraints, prerequisite relations, and common misconceptions. Constraint-Based Modeling and Answer Set Programming demonstrate that large sets of pedagogically valid problems can be created with minimal human authoring effort [22]. For programming domains, methods based on mining open-source code and converting it into language-independent Meaning Trees have generated over a million diverse problems with rich pedagogical metadata and expert-validated quality [23]. Findings from STEM Automatic Item Generation further show that small discrete parameter changes can activate misconception-prone reasoning, a phenomenon also observed in programming items [24]. These LPG frameworks complement our multi-type item design by highlighting that many programming “questions” operate as structured learning problems requiring conceptual and semantic reasoning.

Synthesizing these findings, our study adopts an evidence-informed plan for question generation. We first build a standardized item bank covering nine item types and apply dual annotation for question-stem semantics, knowledge points, and scoring rules to serve as a consistent basis for model training and evaluation. We then employ intermediate schemas and reusable templates to guide the model in generating stems, options, and reference answers by item type and knowledge point, and we design distractors to target common misconceptions so as to improve discriminability and diagnostic value. For programming-related item types, we combine static analysis with execution-based verification and prepare baseline, boundary, and randomized test cases to ensure executability and correctness. We also provide difficulty tags and curriculum-alignment fields to support course scheduling and item sequencing. Finally, we use version control and audit sampling to ensure traceability of revisions and sources. Within an internal test environment, we compare the base and fine-tuned models under identical protocols to assess specification adherence and stability in question generation, thereby operationalizing the method described in the Section 3.

2.2. Automated Grading

In research on automated grading, early approaches relied on instructors predefining the correct answers and having the system verify submissions against those answers—for example, in true–false, single-choice, and matching items where keys can be specified in advance. Although this requires instructors to configure answer keys beforehand, it can substantially reduce grading time [25]. In programming education, instructors similarly design test data in advance so that, once students submit code, program outputs can be compared against predefined test cases, markedly reducing the grading workload for instructors and teaching assistants [26]. While such methods enable correctness checking—including for boundary conditions—they also demand considerable instructor time to design comprehensive tests. Moreover, insufficiently broad test data may allow faulty programs to appear to pass, leaving vulnerabilities undiscovered; for instance, failing to validate inputs and outputs can lead to security issues such as SQL injection or code injection [27]. Hence, end-to-end verification is needed so learners understand that merely passing a few tests does not constitute success and that reliable programs depend on thorough testing [28].

Recent studies have explored how AI can enhance programming instruction [29]. Some employ DevOps-style systems that use version control platforms such as Git to track contributions within programming assignments, thereby quantifying individual performance in teams. Although such designs can accurately assess individual contributions, they often focus on a single team-performance indicator and fall short of supporting adaptivity for learners’ individual progress [30]. The ProgEdu system likewise quantifies team contributions using code-quality tools such as SonarQube and implements automated feedback, yet its feedback centers on code style and basic error detection and does not dynamically adapt to learners’ behaviors [31,32]. A related line of work, ProgEdu4Web for web programming courses, integrates static analysis tools such as HTMLHint and StyleLint to help students follow quality standards and adopts an iterative strategy that allows multiple submissions until requirements are met, thereby improving code quality and collaboration [33]. However, ProgEdu4Web primarily targets static analysis and gives limited attention to dynamic faults and boundary scenarios.

Against this backdrop, our study formalizes automated grading along several dimensions. First, we establish an annotation schema that links item types to grading tasks, mapping single-choice, fill-in-the-blank, true–false, multiple-choice, and programming-related items to explicit decision rules, and we standardize evaluation procedures and the testing environment to ensure comparability across models and versions. Second, we fine-tune the model with a domain question bank so it can learn grading rules specific to programming education, and we incorporate error-type–oriented prompting to reflect common learner mistakes, improving the stability and interpretability of grading decisions. For programming items, we integrate consistent checks of input–output behavior and boundary scenarios directly into the grading pipeline so that text-based judgments are corroborated by execution-based evidence, reducing the risk of misclassification from description alone. Finally, we quantify grading effectiveness using standard machine learning metrics—Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1—while conducting error analyses by item type and class to calibrate and refine grading rules. This processing pipeline aligns with the performance evaluation and comparison stage, yielding reproducible quantitative evidence. To support practical adoption, we also collect learners’ perceptions of grading trustworthiness, interaction experience, and difficulty appropriateness, and triangulate these with quantitative results to adjust explanatory feedback and presentation details, thereby connecting technical gains to usability in instructional settings.

3. Materials and Methods

To systematically evaluate generative AI for automatic recognition of diverse programming item types and for answer grading, and to compare pre- and post-fine-tuning performance, we adopted a controlled experimental design within a single internal testing environment to avoid bias from data or execution conditions. The overall pipeline comprised question-bank construction and data preparation, model training and optimization, internal testing, performance evaluation and comparison, followed by user-context verification and questionnaire collection.

The experimental course was a first-year required programming course in a computing-related department at a university in Taiwan, taught in C and covering fundamental programming concepts, function writing and applications, as well as advanced topics such as pointers and linked lists. Participants were 29 students from electrical and information disciplines, including 25 first-year students and 4 repeaters. The sample included 17 men (58.6%) and 12 women (41.4%), mean age approximately 18. All students had experience using generative-AI-based assistance during the course.

3.1. Question-Bank Construction and Data Preparation

We built a standardized item bank spanning nine item types: single-choice, fill-in-the-blank, multiple-choice, true–false, code fill-in, debugging, full-program tasks, matching, and short-answer. Each with at least 50 training instances and 30 test instances. Item-type frequencies were intentionally stratified to reduce topic-level imbalance. Each item was paired with student response samples covering correct, incorrect, partially correct, and ambiguous categories. Correct responses constituted the majority category (56.8%), followed by incorrect responses (26.7%), while ambiguous (16.4%) and partially correct (15.8%) answers appeared far less frequently. This distribution mirrors typical learner performance but naturally introduces class imbalance. All data were dual-annotated and cross-checked by at least two domain experts to clarify stem semantics, knowledge-point tags, answer rules, and grading classes, and to define naming conventions and field structures. We then performed stratified random splits by topic and item type to create training, validation, and test sets, preventing data leakage.

3.2. Model Fine-Tuning Procedure

In this study, we fine-tuned two separate GPT-4o models, one for item-type recognition and one for answer grading. Both models were trained using chat-style JSONL files that encode each instance as a short dialogue between a user and an assistant. The following steps describe the fine-tuning procedure so that it can be reproduced or extended by other researchers.

Step 1: Data encoding. For each task, we constructed a JSONL file in which every line represents a single training instance with a messages field. Each messages array contains one user message and one assistant message. The user message includes the full item content and, for grading, the student’s answer; the assistant message contains only the ground-truth label. For item-type recognition, the label is one of the nine predefined item types in the question bank. For answer grading, the label is one of four categories: correct, incorrect, partially correct, or ambiguous. All labels are written as plain text strings to facilitate direct comparison with model outputs.

Step 2: Dataset composition. For item-type recognition, each of the nine item types contributes 50 training instances and 30 test instances, as summarized in Section 3.1. For answer grading, all available annotated responses were included in the training set, and a disjoint subset was reserved as the test set. No test instances were used during fine-tuning. The same question–answer pairs that appear in the evaluation were never present in the training data.

Step 3: Fine-tuning configuration. Both models were fine-tuned using the official GPT-4o fine-tuning API in chat-completion mode. We did not perform manual hyperparameter tuning; instead, we relied on the provider’s default optimization settings for batch size, learning rate scheduling, and number of epochs. The objective is to minimize the cross-entropy loss between the model’s predicted label and the ground-truth label in the assistant message. Separate fine-tuning jobs were launched for item-type recognition and answer grading, each using its own JSONL file.

Step 4: Inference setup for evaluation. During evaluation, we used the same model family (GPT-4o) for both the base and fine-tuned conditions. For each test instance, we constructed a chat-completion request containing only a single user message (item content plus student answer, if applicable) and a fixed system prompt that instructs the model to output one label from the predefined set. Temperature was set to 0 and the maximum number of output tokens was kept small to encourage deterministic, label-only outputs.

Step 5: Output normalization and metrics. The raw model outputs were post-processed by a rule-based normalizer that maps them back to the valid label set (see Appendix A). We then computed Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1 on the held-out test sets, and performed paired comparisons between the base and fine-tuned models across item types.

3.3. Model Inference and Output Normalization

For both item-type recognition and answer grading, inference consisted of a single chat-completion call to the model. The input comprised a system prompt specifying the allowed label set and one user message containing the item content (and the student answer, for the grading task). Temperature was fixed at 0 to ensure deterministic outputs. Since the model occasionally produced descriptive text instead of label-only responses, we applied a deterministic normalization procedure. The output string was lowercased, whitespace-trimmed, and matched against the predefined label set using exact or nearest-string mapping rules. Outputs that did not map to a valid label were discarded and re-evaluated once with stricter system instructions. This procedure ensured that both the base and fine-tuned models were evaluated under identical constraints.

3.4. Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Analysis

For the item-generation task, model outputs were evaluated against the ground-truth item-type label specified in the test set. Although the task involves natural-language generation, the evaluation reduces to a multi-class classification problem by extracting the model’s predicted item type from the generated text. The system prompt explicitly instructs the model to output one label from the predefined set, and a normalization procedure (Section 3.3) maps outputs to valid labels.

Following this mapping, Precision, Recall, and F1 were computed using standard multi-class definitions. A true positive (TP) occurs when the predicted item type matches the ground-truth type; a false positive (FP) when the model predicts an item type different from the correct one; and a false negative (FN) when the model fails to generate the correct type for an instance belonging to that class. True negatives (TN) are implicitly defined as all remaining class–instance combinations. These definitions enable classification-based evaluation even for generation tasks, as all model outputs are normalized to a single categorical label.

For answer grading, evaluation follows the same multi-class framework using the four ground-truth labels (correct, incorrect, partially correct, ambiguous). Metrics were computed on the held-out test set, and paired-sample comparisons between models were conducted as described earlier in this section.

3.5. User-Context Verification and Questionnaire

After training and internal testing, the fine-tuned model was deployed in our instructional system [34]. To assess perceived differences after model calibration, students first used the system for one month prior to adjustment as Phase 1. To ensure exposure, each student was required to operate the system for at least two hours per week during class time, yielding a minimum of eight hours of use per student. After one month, we updated the model and provided another month of use as Phase 2. At the end, a structured questionnaire gathered learners’ perceptions of question quality, grading trustworthiness, explain ability, difficulty appropriateness, and overall experience, along with an open-ended section for improvement suggestions. Questionnaire data and system logs were anonymized and triangulated with quantitative performance outcomes to guide further optimization.

The questionnaire is shown in Table 1. Items 1–5 adopted a five-point Likert scale with anchors strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree. Item 6 was open-ended for qualitative analysis to capture students’ actual views. For questionnaire evaluation, we used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 27.0) to conduct Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Sampling adequacy was first examined via the KMO measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, indicating suitability for factor analysis. Components were extracted using PCA with the criterion eigenvalues greater than 1, yielding principal elements with a cumulative explained variance of 71.11%, indicating that PCA accounted for 71.11% of the original variance. Varimax rotation (orthogonal, maximum variance) was then applied to magnify differences and structure among factor loadings, facilitating interpretation.

Table 1.

Questionnaire.

Following rotation, items loaded on the intended dimensions, supporting content validity. All factor loadings exceeded 0.50, indicating good construct validity. Internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s α, yielding α = 0.730, which indicates satisfactory homogeneity and scale reliability.

4. Results

This study adopted a mixed-methods design that combined quantitative and qualitative approaches to examine the usability of a fine-tuned generative AI system in programming-education contexts from two perspectives: objective performance and subjective experience. We first focus on a quantitative comparison conducted with standardized metrics and a homogeneous testing environment to assess how fine-tuning affects accuracy in question generation and answer grading. We then shift to the learner perspective, using questionnaires and open-ended feedback to determine whether the observed objective gains translate into perceivable learning quality and system usability. The aim is to provide multi-level converging evidence for the system’s overall functionality.

4.1. Quantitative Evaluation of AI Model Performance

The quantitative analyses describe how the base model and the fine-tuned model performed under the controlled conditions of this study (Table 2 and Table 3). These observations should be interpreted as specific to the dataset, item distribution, and prompting configuration employed here.

Table 2.

Paired-sample analysis for pre–post model performance (Question Generation).

Table 3.

Paired-sample analysis for pre–post model performance (Answer Grading).

For item-type recognition, the fine-tuned model produced higher values across Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1. These differences were examined using paired-sample analyses across the nine item types, each represented by at least 50 training instances and 30 testing instances. The paired-sample comparisons indicated that the differences in all four metrics were statistically distinguishable within this dataset (p values near 0.03–0.05), and the 95% confidence intervals for the paired differences did not include zero. Effect-size estimates (Cohen’s d ranging from −0.74 to −0.85) represent moderate magnitudes under the present conditions. These results suggest that fine-tuning aligned the model more closely with the annotation conventions and structural regularities of the item bank used for training.

For answer grading, the baseline performance of the base model was already close to ceiling across item types. As a result, differences between the base and fine-tuned model were small and not statistically distinguishable in the paired tests. The confidence intervals for all paired differences included zero, and effect-size estimates were small. These findings indicate that, for grading tasks with limited room for upward change, fine-tuning produced only marginal adjustments that should be interpreted cautiously and within the bounds of this dataset.

Across both tasks, overall accuracy was higher than the macro-averaged metrics. This pattern reflects the class distribution of the data: “correct” responses are more frequent than “partial”, “ambiguous”, or “incorrect” responses. Because accuracy is sensitive to majority-class prevalence, macro-averaged metrics provide a more balanced depiction of performance across all classes, including minority error types.

Beyond aggregate metrics, a closer inspection of item-type–level behavior reveals a pronounced structural pattern underlying these improvements. Rather than uniform gains, the fine-tuned model showed the largest advances in item types that require semantic interpretation or multi-step reasoning, particularly debugging, full-program tasks, and code fill-in items. These categories previously yielded no correct predictions from the base model but achieved near-perfect performance after fine-tuning. In contrast, recognition-oriented types such as single-choice, true–false, and matching showed little change because the base model already operated at ceiling. This pattern highlights that the benefits of fine-tuning are concentrated precisely in the cognitively demanding regions of the task space, where domain-specific structure and annotation regularities are most influential.

4.2. User-Experience Analysis

To verify whether the quantitative gains in AI-based generation and grading align with students’ perceived value in use, we conducted qualitative and descriptive analyses of questionnaire data from participating students. The questionnaire employed a five-point Likert scale to evaluate question quality, grading accuracy, generation quality, difficulty appropriateness, and overall interaction experience; results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Questionnaire Statistics.

Findings show an overall positive trend with differentiated performance across dimensions. First, the mean for AI grading accuracy was 4.0870 (SD = 0.6683), with a positive-rating rate of 82.6%, the highest among all dimensions, indicating strong perception of improved scoring correctness in Phase 2. Second, clarity of question generation averaged 3.9565 (SD = 0.8245), with a 73.9% positive-rating rate, suggesting clearer stems and option design than in Phase 1 and broad learner approval. Third, overall interaction experience averaged 3.8261 (SD = 1.1141), with a 65.2% positive-rating rate, a mid-to-high level indicating that readability, feedback presentation, and interaction flow supported learning, though room for refinement remains. Fourth, difficulty appropriateness averaged 3.6957 (SD = 0.9740), with a 56.5% positive-rating rate, implying general acceptability while signaling the need to better accommodate variability across proficiency levels. Fifth, perceived speed for generation and grading averaged 3.1304 (SD = 1.1795), with a 26.1% positive-rating rate, the lowest and most dispersed of the five, reflecting limited perceived improvement in response time and identifying speed as a priority for optimization.

In sum, two implications emerge. On accuracy-related dimensions, including grading accuracy and question clarity, learners reported clear positive perceptions that align with the objective gains noted earlier, indicating that core quality improvements are indeed felt at the interface. On process-efficiency dimensions, particularly speed, evaluations were evidently lower and more variable, showing substantial differences across students’ perceptions of response time. This identifies the reduction in perceived waiting and the enhancement of interaction flow as primary targets for subsequent system improvements.

5. Discussions

Before interpreting the implications of the findings, it is important to foreground two structural limitations of the present study. First, the sample size was modest and drawn from a single course within one institution, which constrains the external validity of the results. Second, although the controlled setting enabled a clean comparison between the base and fine-tuned models, it also limits the diversity of instructional contexts represented.

To address these constraints, we propose a succinct replication roadmap that allows other researchers to reuse and extend our study design. Because all training and evaluation data follow a consistent JSONL schema with explicit item-type, knowledge-point, and grading-label fields, researchers can replace or augment the datasets with items from their own courses while preserving the same experimental pipeline. The reproducibility appendix further specifies the prompt templates, normalization rules, evaluation procedures, and item-bank schema, enabling others to rerun the model comparison or substitute a different model family while maintaining methodological consistency. Together, these components form a portable framework that can be readily adapted to new cohorts, new institutions, or expanded multi-site studies.

5.1. Discussion Addressing the Research Questions (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3)

Regarding RQ1, our multi–item-type evaluation indicates that large language models exhibit structured performance differences across item types. Closed-ended items (single-choice, true–false, fill-in-the-blank), with limited answer spaces and explicit rules, allow the model to attain higher consistency in question generation and greater accuracy in answer grading. In contrast, programming-related items (code fill-in, debugging, full-program tasks) involve executability and multiple equivalent solutions; scoring depends on boundary conditions and semantic context and is therefore more sensitive to data distribution and specification control. Similar performance discrepancies between closed-ended and programming-oriented items have also been reported in prior research. Sarsa, Denny, Hellas and Leinonen [7] found that LLMs performed reliably on well-structured multiple-choice questions but struggled substantially with code-generation and debugging tasks due to semantic ambiguity and boundary-condition sensitivity. Likewise, Tambon, Moradi-Dakhel, Nikanjam, Khomh, Desmarais and Antoniol [8] observed that LLM-generated code frequently failed in correctness checks, highlighting the same structural vulnerabilities seen in our item-type–specific results.

To support the interpretation of RQ1, we provide performance differences between base and fine-tuned models in Table 5. These results show that improvements were not uniformly distributed across all item types. Fine-tuning yielded the largest gains for structurally complex categories such as debugging and code-writing items, whereas simpler formats such as single-choice or true–false questions exhibited smaller differences. This pattern aligns with our qualitative expectation that item types requiring multi-step reasoning or semantic consistency benefit more from task-specific tuning.

Table 5.

Performance Differences Between Base and Fine-Tuned Models (FT—Base).

Table 5 illustrates not only numerical differences but a meaningful reorganization of the model’s capability profile. The fine-tuned model’s dramatic gains in debugging (+1.000 F1), full-program tasks (+1.000 F1), and code fill-in (+0.929 F1) suggest that domain-specific regularities, such as error-pattern distributions, common boundary-condition structures, and canonical execution flows were effectively internalized during fine-tuning. These item types are inherently open-ended: small deviations in logic or syntax can produce cascading failures in executability. The fact that fine-tuning almost entirely eliminated such failures indicates that structured domain annotation may act as a strong inductive guide for LLMs, enabling them to approximate consistent reasoning over program semantics. Conversely, the lack of change in single-choice, true–false, and matching items reinforces an important practical implication: when the base model already possesses high-precision recognition rules for closed-ended formats, additional fine-tuning yields little marginal benefit. This asymmetry highlights where instructional automation is most promising and where traditional methods remain sufficient.

It is important to note that the evaluation in this study measures only whether the generated output corresponds to the correct item type after normalization. This approach captures structural correctness but does not assess the substantive pedagogical quality of the generated learning problems. We did not evaluate whether a generated problem is conceptually accurate, free of misleading information, understandable to students, or ready for use in authentic instructional settings. As such, the applicability of our findings is inherently limited: a model may generate the correct type of question while still producing content that is incorrect, vague, or pedagogically inappropriate.

At the current stage, the use of such generated items in real courses still requires teacher review and validation to determine whether the learning problem is accurate, comprehensible for students, and aligned with instructional goals. The improvements observed in this study therefore represent advances in structural control, rather than guarantees of educational quality. Future work should incorporate semantic validation or instructor-based rating protocols to ensure classroom readiness.

The findings for RQ2 reflect how the model behaved after applying the complete fine-tuning pipeline, rather than the influence of any individual design decision. Because the present study compares only the base GPT-4o model with the final fine-tuned version, the results capture the aggregate impact of all modifications embedded in the fine-tuning process, including dataset composition, label formatting, prompting structure, and exposure to task-specific examples. The study did not incorporate an ablation design that systematically varies these components one at a time. Consequently, the analysis cannot isolate the specific contribution or relative importance of any particular modification to the observed performance changes. This limitation is consistent with findings from prior domain-adaptation studies. Zhang and Liu [35] similarly reported that fine-tuned LLMs for programming tasks demonstrated aggregate performance gains without clear attribution to specific training components, while Gu et al. [36] emphasized that performance changes after domain fine-tuning often emerge from intertwined effects rather than isolated design factors.

Within this methodological scope, the results indicate that the fine-tuned model offers more stable performance across item types in Phase 2 compared with the base model in Phase 1, particularly in programming-oriented tasks that require structural or semantic understanding. However, these improvements should be interpreted as the outcome of the overall configuration rather than attributable to any single adjustment. It remains possible that some components of the pipeline contributed more strongly than others, or that certain modifications had negligible or even negative effects that were masked by the overall gains.

To draw firmer conclusions about the causal role of specific design elements, future research should include controlled ablation experiments that vary one component at a time. Such analyses would allow researchers to determine which aspects of the fine-tuning pipeline—such as dataset balancing, prompt design, normalization strategies, or example selection—are most critical for improving model generalization and task-specific behavior.

With respect to RQ3, the quantitative performance patterns and users’ subjective perceptions are broadly aligned, yet a critical gap remains. Learners give positive judgments to grading trustworthiness and question clarity, indicating that gains in correctness and structural coherence are perceptible at the interface. However, ratings for speed and interaction smoothness are weaker, implying that without concurrent optimization of response time and interaction rhythm, technical improvements can be diluted in practice. These observations define adoption thresholds and governance principles: set confidence thresholds and spot-check rates so low-confidence or high-risk item types trigger human review to preserve grading credibility; establish traceability and appeal mechanisms that retain generation and scoring rationales to reduce dispute costs; incorporate speed and stability into routine monitoring indicators and optimize at key nodes—from feedback presentation and task scheduling to inference length—so correctness and timeliness are met together. Only when objective performance and perceived usability both exceed these thresholds can classroom automation operate sustainably.

Although several design factors such as temperature settings, sampling configurations, tool use, and execution-based checks may influence LLM behavior, these aspects were not part of the analytic scope of the present study. Rather than examining the causal contribution of individual design elements, this work focused on evaluating the aggregate behavior of the base and fine-tuned models. This is primarily because the study intentionally adopted a single model GPT-4o as the fixed foundation for all analyses. The differences observed before and after fine-tuning therefore reflect adjustments to internal parameters within the same underlying model rather than changes in the model architecture or inference mechanisms. The potential influence of specific design parameters is explicitly as an avenue for future research. Moreover, design factors such as temperature or tool-use configuration exhibit model-dependent behavior, and their baseline configurations vary substantially across model families. Introducing multiple models or conducting factor-wise manipulation would broaden the methodological scope in ways that deviate from the central focus of this study. For these reasons, the evaluation emphasized a controlled comparison between the base and fine-tuned versions of GPT-4o under a unified configuration, rather than an ablation-style analysis of design factors. Future research may extend this work by varying inference parameters or incorporating additional model families to more fully characterize how design choices interact with model architecture and training strategies.

5.2. Classroom Utility

Converging quantitative and questionnaire evidence shows that, after fine-tuning, the generative tool’s classroom utility is reflected primarily in improved correctness and usability. More reliable identification and generation of item structures enhance alignment between stems and knowledge points, reducing instances of ambiguous prompts or ill-formed options. These observations align with reports from educational systems that integrate generative AI into programming exercises. Šarčević et al. [37] found that students similarly valued improved clarity and correctness in AI-assisted feedback, indicating that usability gains in generative educational tools often hinge on stability and interpretability. On an already high baseline, grading decisions become more stable, increasing learners’ trust in scores and reducing anxiety about misclassification, which, in turn, strengthens willingness to persist. This combination of correctness and stability substantially enhances the feasibility of automated grading as a formative-assessment instrument, enabling frequent practice at lower staffing cost.

The tool’s effects also extend to self-regulation. When the model consistently identifies errors and returns actionable cues, students can locate problems and initiate revisions, shifting from passively “waiting for a score” to actively “understanding the error.” Positive questionnaire responses to feedback usefulness and question clarity suggest that practice can be converted into opportunities for strategy internalization rather than mere repetition. Over time, such tools can foster reflection and error awareness—especially vital in programming tasks that demand repeated verification and boundary checking.

Operationally, the tool can relieve grading pressure and scheduling bottlenecks. With stable, high accuracy in grading, instructors and TAs can reallocate time to difficult or contentious cases, focusing scarce human resources on higher-value diagnosis and guidance. This rebalances classroom pacing, making high-frequency practice and timely feedback the norm rather than a function of grading queues. Nonetheless, limitations are evident. Perceived slowness and heterogeneous user experiences can impede learning flow and amplify frustration, particularly when non-learning interactions consume time. The lesson is clear: effectiveness requires both accuracy and speed; otherwise, perceived waiting can offset technical gains.

Implications for equity also merit attention. Stable decisions reduce “same item, different grade” inconsistencies, strengthening a baseline for grading consistency and making outcomes more predictable for students, which may lower appeals and disputes. At the same time, small but persistent borderline cases can still yield isolated misclassifications, indicating that while the tool reduces uncertainty, it does not eliminate risks at the margins. Therefore, reproducibility and consistency gains should be complemented by spot-checks and audit trails to handle ambiguous cases and realize equity benefits for every learner.

The issue of class imbalance also carries important educational consequences. When the “correct” category is overrepresented, a model may exhibit a tendency to overpredict correctness, effectively treating many erroneous or partially correct responses as acceptable. Such misclassification could mislead learners, reinforce misconceptions, or inflate confidence by signaling that incorrect reasoning is valid. Conversely, minority categories such as “incorrect” or “vague” are pedagogically critical because they indicate where students require clarification or targeted feedback. Underperformance on these classes therefore presents a substantive instructional risk. Ensuring balanced evaluation data and applying model oversight remains essential for preventing such unintended negative learning effects.

Finally, motivational effects depend on interaction tempo. When question quality and grading credibility earn student approval, willingness to keep answering and iteratively revising rises. Conversely, delays, stutters, or excessive nonessential steps dilute focus and prolong time-to-item, dampening engagement. These findings remind us that technical accuracy and reliability are necessary conditions; converting them into sustained learning momentum hinges on interaction fluency and the immediate visibility of feedback.

5.3. Implications for Instructional Design in Programming Courses

Our quantitative results indicate that, after fine-tuning, the system recognizes item structures more reliably and produces more stable grading decisions. For course design, this suggests that instructors can pre-label unit-level knowledge points, item types, and difficulty levels, and use the system prior to class to generate multiple parallel versions that are equivalent in structure but differ in surface features. Coupled with expert spot-checking and test-data verification, this process yields a ready-to-teach item bank. During class, teachers can then assign cross-type practice on the same concept based on students’ ongoing performance, converting the model’s structural strengths into adaptive learning while reducing the burden of on-the-fly item selection and revision.

For feedback design, we recommend standardizing feedback around common error patterns, such as missing control-flow branches, unhandled boundary conditions, inconsistent input–output formats, and unnecessarily high time complexity. After grading, the system should first localize the error, then present a minimal counterexample and concrete repair steps, and finally suggest a small set of key test cases for self-verification. Class activities can incorporate “micro-debugging stations” where students revise according to system feedback, compare alternative fix paths with peers, and the instructor closes with a synthesis of shared strategies. Feedback organized by error pattern helps translate the model’s stable judgments into executable learning actions.

Quality control in generation and scoring benefits from human–AI collaboration. In practice, set model confidence thresholds and fixed spot-check rates so that low-confidence or high-risk items are queued for priority human review, allowing teaching assistants to focus on genuinely contentious or error-prone cases. With version and provenance records, the system can automatically store grading rationales and feedback traces. When students appeal, instructors can quickly diagnose whether the issue lies in the stem specification, insufficient test data, or conceptual misunderstanding, and then perform targeted corrections. This preserves credibility while reducing manual costs.

To shorten waiting and avoid unverified content degrading the experience, separate generation and verification into two stages. Complete stem generation and test-data checks before class; during class, restrict operations to lightweight parameterized rewrites and sampled delivery to reduce latency. Fix the grading pipeline to a clear sequence of rule checks, unit-level test execution, model decision, and feedback integration. Any failure should return a clear, readable reason rather than a vague message, preventing frustration from repeated opaque attempts. Such a process turns model stability into a predictable learning rhythm.

5.4. Analysis of Open-Ended Student Feedback

To deepen qualitative evidence, we analyzed open-ended comments. Observations clustered into four themes: the degree to which game mechanics interfere with learning flow, system performance and stability, interaction tempo and perceived waiting, and assessment presentation with learning supports.

The instructional platform in this study is the Game-based Programming Learning System (GBPLS) developed by Chen, Chen, Lai and Peng [34], which integrates game-based learning with generative AI to enhance programming learning. A key feature is the use of generative AI to create programming questions tightly aligned with course content through instructor-guided prompt design. Instructors provide lecture notes and related materials from an introductory computing course as training inputs, covering variables, conditionals, loops, arrays, and structures. By internalizing these knowledge points, the model generates targeted practice questions.

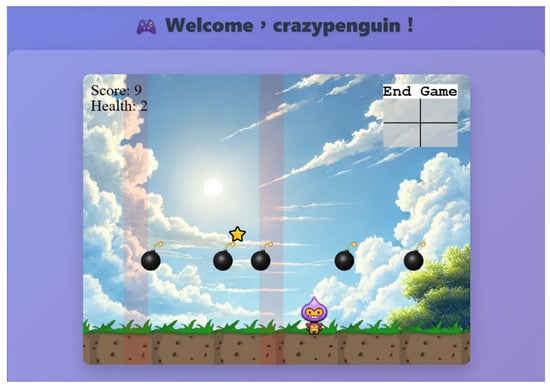

To increase engagement and challenge, GBPLS adopts a “bomb-dodging” mechanic, as shown in Figure 1. Students move a character to avoid falling bombs; collisions reduce life, and the game ends when life reaches zero, at which point a score is recorded. Contact with a star triggers a programming question generated by the AI according to instructor prompts (Figure 2). Students must answer correctly to earn points and continue; incorrect answers incur penalties. Over time, the question difficulty increases and bombs fall faster. This design heightens excitement while prompting repeated practice and consolidation of concepts.

Figure 1.

In the game interface, students move a character left and right to dodge bombs falling from the top; the top bar shows lives and score, and stars occasionally appear from both sides to trigger questions.

Figure 2.

After the character touches a star, a programming-question window pops up with the stem, a response area (options or code box), a submit button, and a feedback section for immediate answering and grading results.

Because points are awarded for correct answers and recorded each round, the system encourages students to tackle more items and provides instructors with a basis for gauging achievement. A leaderboard further stimulates peer competition and sustained engagement (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

GBPLS leaderboard interface showing students’ performance by rank, student ID or nickname, and cumulative points, with multi-round aggregation and real-time updates to encourage peer competition and motivation.

Given these mechanics, the most frequent feedback focused on “excessive bomb density and speed,” which imposed non-learning cognitive load. Many students repeatedly noted that there were too many bombs, rounds lasted too long, stars were too scarce, and time spent between questions felt wasted. These comments suggest that current difficulty tilts toward action demands rather than quickly returning students to problem-solving, which risks diluting attention and reducing persistence. Corresponding design adjustments include lowering bomb spawn rates and speed, increasing star frequency, and prioritizing “time-to-question” over high-tension operation.

Regarding system performance and stability, students reported freezes or interruptions, pages failing to load, grading stalls, and symbol rendering as question marks that obscured meaning. Some encountered outages during maintenance and recommended prior notices to avoid replay. These concerns align with questionnaire findings on limited perceived speed gains and high variance in experience. Planned remedies include preloading questions and grading results, standardizing text encoding, decoupling level loading from grading services, in-system maintenance announcements with countdowns, and automatic return to the latest checkpoint after crashes to prevent replaying an entire round.

For interaction tempo and waiting, many cited delays before questions appeared and slow movement speed, indicating a high entry cost before answering. A two-stage presentation can reduce perceived waiting by immediately showing a brief “star collected; question loading” message or a short exemplar while the actual item is retrieved or generated in the background. Movement parameters and path layouts can be adjusted to shorten average travel time to questions. Caps on maximum score or round duration can also prevent overly long sessions caused by generation delays.

In assessment presentation and learning support, students requested immediate access to correct answers or references after mistakes, clearer options that avoid two seemingly valid statements with unclear preference, and fixes for symbol rendering that impedes comprehension. These requests point to two principles. First, post-grading explanatory feedback should include the correct answer, key steps, and a minimal counterexample to help students pinpoint misconceptions. Second, distractor language should follow consistent, comparable, and diagnostic rules rather than relying on semantic ambiguity. Similar concerns have been noted in large-scale analyses of AI-generated educational items. Johnson, Dittel and Van Campenhout [13] reported that learners are particularly sensitive to distractor clarity and feedback transparency, both of which strongly shape perceived fairness and usability. Our findings echo these results, highlighting the need for item-quality controls that go beyond correctness to incorporate format clarity and conceptual discriminability.

Finally, the interpretation of student survey responses warrants cautions due to the structure of the questionnaire. The items used a binary comparative format, asking students whether the system felt “better” after the update. Such a formulation does not capture the magnitude of perceived improvement and treats slight and substantial changes equivalently. Consequently, the survey results indicate only that students did not perceive the system as worse after fine-tuning, rather than providing evidence of strong or measurable improvements in user experience. As a result, the findings should be understood as reflecting general acceptability rather than significant perceived enhancement. Future studies should employ multi-level Likert scales or validated perception instruments to obtain more granular measurements of user-perceived improvement.

6. Conclusions

Situated in a programming-education context, this study examined the practical benefits of a domain-fine-tuned generative tool for two core capacities: the recognition and generation of item structures and the stability of answer judgments. In contrast to prior work that highlights the content uncertainty and error propagation of directly applying general-purpose models [2,3], our findings show that fine-tuning with a rigorously annotated, item-explicit, and test-data-complete domain question bank yields a marked improvement in question generation and a further stabilization of grading performance that was already strong at baseline. These results align with the broader claim that educational tasks require contextualized and structured model adaptation and provide reproducible quantitative evidence specifically for programming item types, extending earlier inferences drawn from examples or small-scale observations [35,36]. Moreover, learner questionnaires and open-ended feedback indicate that gains in correctness and clarity are perceptible to students and can translate into higher trust and sustained engagement, thereby complementing studies that have focused mainly on system-level metrics while paying less attention to learner experience [37]. At the same time, the data underscore that interaction speed and flow remain decisive: in authentic classroom use, perceived waiting and interface pacing can modulate the practical impact of technical improvements.

Although the present findings demonstrate clear improvements in question generation and grading stability after fine-tuning, they should be interpreted as preliminary evidence derived from a single course context within one institution. The sample size and course specificity impose natural constraints on external validity. Consequently, these results represent an initial indication of feasibility rather than conclusive evidence of general effectiveness across broader instructional settings. Future studies must therefore examine whether the observed performance gains can be reproduced under varied curricular structures, different student populations, and alternative instructional modalities.

To strengthen the generalizability of the system’s observed benefits, we propose a concrete multi-stage replication plan. First, the model will be deployed in additional introductory programming courses that differ in class size, instructional pacing, and assessment formats to examine whether performance improvements remain stable across heterogeneous teaching contexts. Second, the system will be implemented in advanced programming or data-structures courses to evaluate transferability to knowledge domains that were not present in the original training distribution. Third, cross-institutional studies will be conducted by collaborating with universities that teach C, Python, or Java as their introductory language, enabling comparisons across cohorts with distinct learning backgrounds. If immediate large-scale replication is not feasible due to institutional constraints, we will conduct an interim evaluation using a smaller held-out subset of topics not included in the fine-tuning data. Examples of such topics include pointer arithmetic, multi-dimensional arrays, recursion, or string-processing functions, which represent conceptually distinct domains relative to the original question bank. Testing these unseen topic categories can provide an early indication of how well the fine-tuned model generalizes beyond its local task templates. These planned efforts form a systematic strategy for validating the robustness and scalability of the current preliminary results.

A further limitation concerns temporal stability. The evaluation in this study was conducted within a single cohort and over two consecutive phases under a controlled instructional environment. Although the results show consistent improvements after fine-tuning, additional work is required to examine whether model performance remains stable across different semesters, future cohorts, or varied course designs. Such investigations would help determine the extent to which the system is robust to potential data drift, prompt drift, or changes in instructional context, thereby strengthening the generalizability of the findings.

Another limitation relates to the potential influence of game mechanics embedded in the instructional platform. Because the system incorporates non-learning interactions such as bomb-dodging, these elements may shape learners’ perceptions of speed, usability, or cognitive load independently of the model’s underlying performance. Although our analyses focused on model-level outcomes, it is possible that perceived delays, interaction pacing, or frustration associated with game operations interacted with students’ evaluations of the AI component. Future research should consider isolating the effects of the game environment from those of the generative model, possibly through controlled comparisons or alternative interface conditions that minimize non-instructional cognitive demands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.L. and Y.-J.C.; methodology, C.-H.L., Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; software, Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; validation, C.-H.L., Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; formal analysis, Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; investigation, C.-H.L., Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; resources, Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; data curation, C.-H.L., Y.-J.C. and Z.-P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.L.; visualization, C.-H.L.; supervision, C.-H.L.; project administration, C.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to school privacy policies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

To support independent verification and reproduction of the results, we provide a concise summary of the core artefacts used in model training and evaluation: the prompt templates, parsing and normalization procedures, evaluation scripts, and the item-bank schema. These components together define the essential experimental pipeline.

Appendix A.1. Prompt Templates

All grading experiments used a fixed system prompt that constrains the model to return only one label from the predefined grading set:

You are a programming education quiz grading assistant. Please judge whether the students’ answers are correct and simply reply with the grading result. For example: “Correct”.

During evaluation, this system prompt replaces any existing system message in the JSONL instance. User messages contain the full item stem and the student’s answer. Assistant messages in the dataset store the ground-truth label. This template ensures that both the base model and the fine-tuned model operate under identical constraints.

Appendix A.2. Parsing and Normalization Code

To ensure consistent comparison across models, all raw model outputs are normalized using a simple rule-based routine:

- Strip whitespace and punctuation.

- If the output exactly matches one of the allowed labels “Correct”, “Incorrect”, “Ambiguous”, “Partially Correct”, it is accepted directly.

- If no exact match exists, the code searches for any of the labels as substrings.

- If exactly one label is detected, it becomes the normalized output.

- If the output still cannot be mapped, the original string is retained.

This procedure aligns free-form model outputs with the closed grading label set used in performance metrics.

Appendix A.3. Evaluation Scripts

The evaluation is implemented in the script, which:

- Loads each instance from JSONL files as a chat-style message sequence.

- Overrides the system prompt with the strict grading template.

- Queries both the base model and the fine-tuned model using identical inference parameters (temperature = 0, constrained max tokens).

- Applies the normalization routine to each output.

- Computes Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1 using scikit-learn.

- Exports detailed logs (item text, ground-truth label, predictions, correctness) to an Excel report.

This script fully defines the evaluation pathway used to generate all reported grading results.

Appendix A.4. Item-Bank Schema

The item bank used for both fine-tuning and evaluation follows a structured schema with the following required fields:

- Item type: One of the nine question types, such as multiple choice, fill in the blank, matching, error correction, and full-process questions.

- Knowledge point: corresponds to the knowledge points in the course, such as conditional judgment, loop, array, indicators, etc.

- stem: The question stem text.

- options/code/response format: Presented according to the question type.

- Reference answer: The correct answer or program output.

- Student responses (grading dataset only): Contains correct, incorrect, partially correct, and ambiguous examples.

- Grading label: Manually labeled standard answer categories, used for model training and testing.

This schema ensures consistent formatting of all training and testing instances and provides the structural basis for building JSONL message sequences used by the evaluation script.

References

- Holmes, W.; Miao, F. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; Unesco Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Labadze, L.; Grigolia, M.; Machaidze, L. Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigci, D.; Eryilmaz, M.; Yetisen, A.K.; Tasoglu, S.; Ozcan, A. Large Language Model-Based Chatbots in Higher Education. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 7, 2400429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; McCoy, A.B.; Wright, A. Improving large language model applications in biomedicine with retrieval-augmented generation: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical development guidelines. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmar, H. Review on the teaching of programming and computational thinking in the world. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 4, 997222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Y.; Leal, J.P.; Queirós, R. Authoring Programming Exercises for Automated Assessment Assisted by Generative AI. In Proceedings of the 5th International Computer Programming Education Conference (ICPEC 2024), Lisbon, Portugal, 27–28 June 2024; pp. 21:21–21:28. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsa, S.; Denny, P.; Hellas, A.; Leinonen, J. Automatic generation of programming exercises and code explanations using large language models. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research-Volume 1, Lugano, Switzerland, 7–11 August 2022; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tambon, F.; Moradi-Dakhel, A.; Nikanjam, A.; Khomh, F.; Desmarais, M.C.; Antoniol, G. Bugs in large language models generated code: An empirical study. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2025, 30, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xia, C.S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Is your code generated by chatgpt really correct? rigorous evaluation of large language models for code generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 21558–21572. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, S.R.; Denny, P.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Payne, S.H.; Ridge, P.G. Evaluating a large language model’s ability to solve programming exercises from an introductory bioinformatics course. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Krantz, A.; Lobczowski, N.G. From Recall to Reasoning: Automated Question Generation for Deeper Math Learning through Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. Higher order prompting: Applying Bloom’s revised taxonomy to the use of large language models in higher education. Stud. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2025, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.G.; Dittel, J.S.; Van Campenhout, R. Intrinsic and Contextual Factors Impacting Student Ratings of Automatically Generated Questions: A Large-Scale Data Analysis. J. Educ. Data Min. 2025, 17, 217–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lodovico Molina, I.; Švábenský, V.; Minematsu, T.; Chen, L.; Okubo, F.; Shimada, A. Comparison of Large Language Models for Generating Contextually Relevant Questions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, Krems, Austria, 16–20 September 2024; pp. 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdi, G.; Leo, J.; Parsia, B.; Sattler, U.; Al-Emari, S. A systematic review of automatic question generation for educational purposes. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2020, 30, 121–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovietov, P. Automatic generation of programming exercises. In Proceedings of the 2021 1st International Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning in Higher Education (TELE), Lipetsk, Russian, 24–25 June 2021; pp. 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Radošević, D.; Orehovački, T.; Stapić, Z. Automatic on-line generation of student’s exercises in teaching programming. In Proceedings of the Radošević, D., Orehovački, T., Stapić, Z:” Automatic On-line Generation of Students Exercises in Teaching Programming”, Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems, CECIIS, Varaždin, Croatia, 22–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, J.; Chen, L.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, X. A review on question generation from natural language text. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2021, 40, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.H.; Peng, J.; Liu, P. Question generation based on chat-response conversion. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch, D.R.; Saha, S.K. Generation of multiple-choice questions from textbook contents of school-level subjects. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2022, 16, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, E.; Jovanov, M.; Madevska Bogdanova, A. Smart generation of code tracing questions for assessment in introductory programming. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Mitrovic, A. Automatic Problem Generation in Constraint-Based Tutors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, San Sebastian, Spain, 2–7 June 2002; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 388–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sychev, O.; Shashkov, D. Mass Generation of Programming Learning Problems from Public Code Repositories. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, E.; Butler, E.; Díaz Tolentino, A.; Popović, Z. Automatic Generation of Problems and Explanations for an Intelligent Algebra Tutor. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, Chicago, IL, USA, 25–29 June 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.-H.; Jong, B.-S.; Hsia, Y.-T.; Lin, T.-W. Association questions on knowledge retention. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2021, 33, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y. Analysis of Learning Behaviors and Outcomes for Students with Different Knowledge Levels: A Case Study of Intelligent Tutoring System for Coding and Learning (ITS-CAL). Appl. Sci. (2076-3417) 2025, 15, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.-S. Detection of SQL injection vulnerability in embedded SQL. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2020, 103, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, K.; Huang, H.; Yu, L.; Zhao, J. A Static Detection Method for SQL Injection Vulnerability Based on Program Transformation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, F. Research on construction and practice of precision teaching classroom for university programming courses. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9560–9576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gauna, B.; Rojo, N.; Graña, M. Automatic feedback and assessment of team-coding assignments in a DevOps context. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Nguyen, B.-A.; Dow, C.-R. Code-quality evaluation scheme for assessment of student contributions to programming projects. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 188, 111273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.; Hays, B.; McMillin, C.; Rezig, E.K.; Rodriguez-Rivera, G.; Turkstra, J.A. Eastwood-tidy: C linting for automated code style assessment in programming courses. In Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–18 March 2023; pp. 799–805. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, H.T.; Chen, H.M. ProgEdu4Web: An automated assessment tool for motivating the learning of web programming course. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2024, 32, e22770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, Z.-P.; Lai, C.-H.; Peng, C.-W. Generative Artificial Intelligence-Based Gamified Programming Teaching System: Promoting Peer Competition and Learning Motivation. Eng. Proc. 2025, 98, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, K. JavaLLM: A Fine-Tuned LLM for Java Programming Education. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Symposium on Computer Science and Intelligent Control (ISCSIC), Zhengzhou, China, 6–8 September 2024; pp. 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Chen, M.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wan, C.; Wei, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. On the Effectiveness of Large Language Models in Domain-Specific Code Generation. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2023, 34, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]