Inter-seeding of legume and grass forages is recognized as an important cultivation strategy that leverages complementary traits; relative to monoculture, it significantly increases forage yield and quality [

1,

2] and enhances the economic value of the soil resource and overall production efficiency [

3]. Among commonly used legume–grass mixtures, mixed sowing of vetch and oat exhibits a pronounced quality-complementarity effect. It has been shown that the mixing ratio is the primary determinant of forage yield [

4,

5,

6]. When vetch and oat seeds are combined at a 4.5:5.5 ratio, higher dry-matter proportions and improved forage quality are achieved [

7]. However, substantial differences in particle shape, size, and physical properties between legume and grass seeds complicate the calibration of physical parameters for seed mixtures; in particular, accurately reproducing motion and contact behaviors in discrete element method (DEM) simulations remains a pressing technical challenge.

With the development of computer technology, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) has been widely applied to analyze particle motion mechanisms and optimize seed metering devices [

8,

9,

10]. It has been proven to be an effective tool for studying the working mechanism of seed metering devices and the movement characteristics of seed particles [

11,

12]. In the process of computer simulation for seed placement, physical parameters such as seed density, size, moisture content, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus, as well as contact parameters such as restitution coefficient, static friction coefficient, and rolling friction coefficient, are key variables in determining particle collision, sliding, and rolling behaviors [

9,

13]. Since the contact parameters between particles are difficult to obtain through actual experiments, the calibration and optimization of DEM contact parameters are particularly important. The calibration of discrete element method (DEM) contact parameters is an effective approach for obtaining the physical parameters of particulate materials. Hu et al. [

9], Shi [

13], and Yong [

14] have, respectively, calibrated the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio for cotton and watermelon seeds. Chen et al. [

15] and Wang et al. [

16] conducted systematic experiments on the restitution coefficient and static friction coefficient for potato tubers and red pine seeds. Zhou et al. [

17], Cao et al. [

18], and Zhang et al. [

19] calibrated the rolling friction coefficient through angle of repose or material flow tests. The results indicate that a reasonable combination of contact parameters can significantly improve the simulation accuracy of DEM for angle of repose and seed placement performance. Binnan Zhou et al. [

20] utilized bonding bonds and the Hertz–Mindlin model to achieve high-precision simulations of walnut behavior during crushing and bending tests. Zhu et al. [

21] constructed a discrete element method (DEM) model for edible sunflower seeds and validated its reliability through seeding and transport tests. Li et al. [

22] and Adilet Sugirbay et al. [

23], respectively, completed the calibration of contact parameters for maize and wheat seeds, providing important references for simulations of air seeding or mechanized operations for different crops. Although the aforementioned methods provide insights for this study, significant differences in physical characteristics such as size and shape exist between Malva sylvestris and oat seeds, and there is currently a lack of systematic research on their contact parameters, which limits the optimization of seeders under mixed planting conditions. In terms of constructing discrete element models, researchers generally begin with actual sizes and shapes to enhance the model’s realism. For example, Guopeng Mi et al. [

24] extracted the outline of sorghum seeds using 3D scanning and developed a discrete element method (DEM) model for sorghum seeds using the spherical particle filling method in EDEM software, demonstrating that the model exhibits high accuracy in simulating sorghum packing and transport behaviors. Wang et al. [

25] and Shi et al. [

26] proposed a modeling strategy combining multiple spheres and polyhedra for sunflower seeds and maize kernels, respectively, and validated the model’s applicability through angle of repose and flow tests. Li et al. [

27] and Chen et al. [

28] compared assembly modeling methods under various combinations of particle shapes and sizes, using buckwheat and maize as research subjects, and demonstrated that reasonably simplified particle combinations can maintain shape characteristics while also ensuring computational efficiency. The aforementioned studies indicate that simulating real particle shapes through methods such as multi-sphere or polyhedron packing, combined with accurate contact parameter calibration, is an effective approach to improving the quality and computational efficiency of DEM simulations. Existing work has predominantly focused on the calibration of physical and contact parameters for individual crop seeds, while systematic studies on mixed seed systems with significant differences in particle shape and density, particularly legume–grass seed mixtures, remain limited.

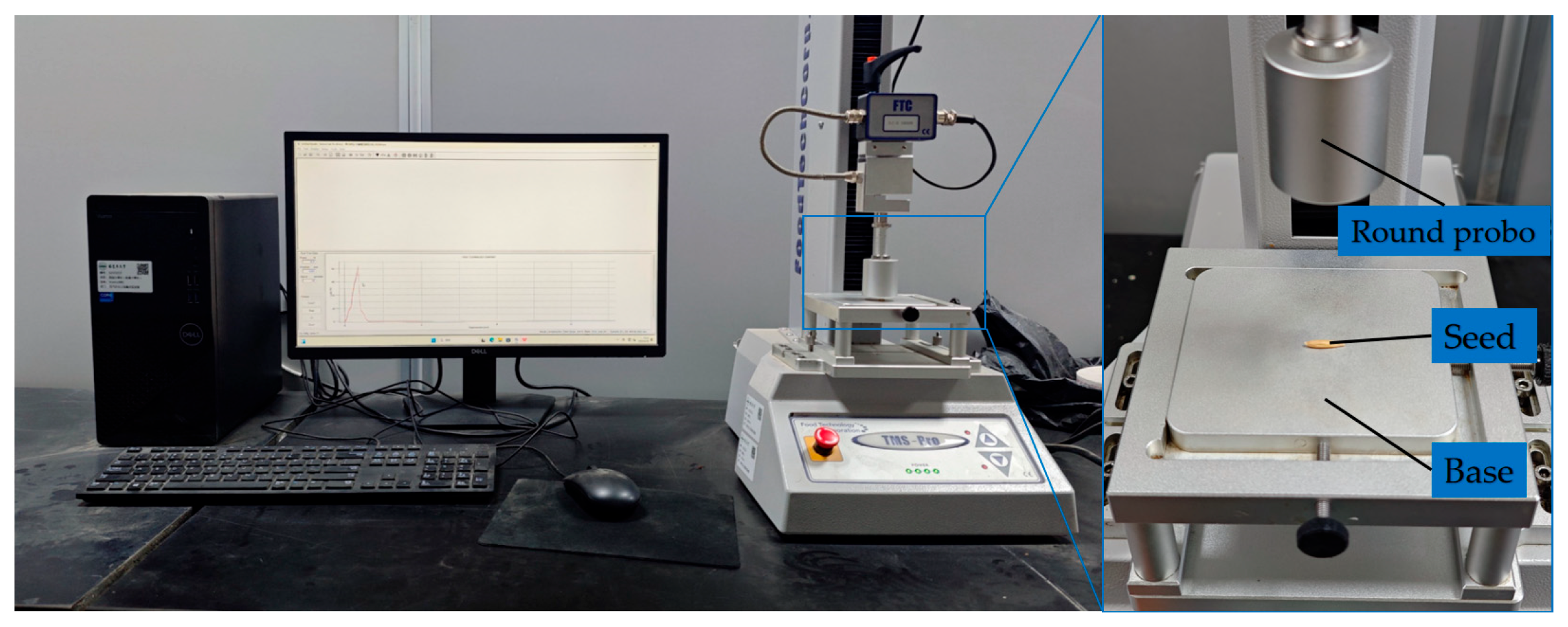

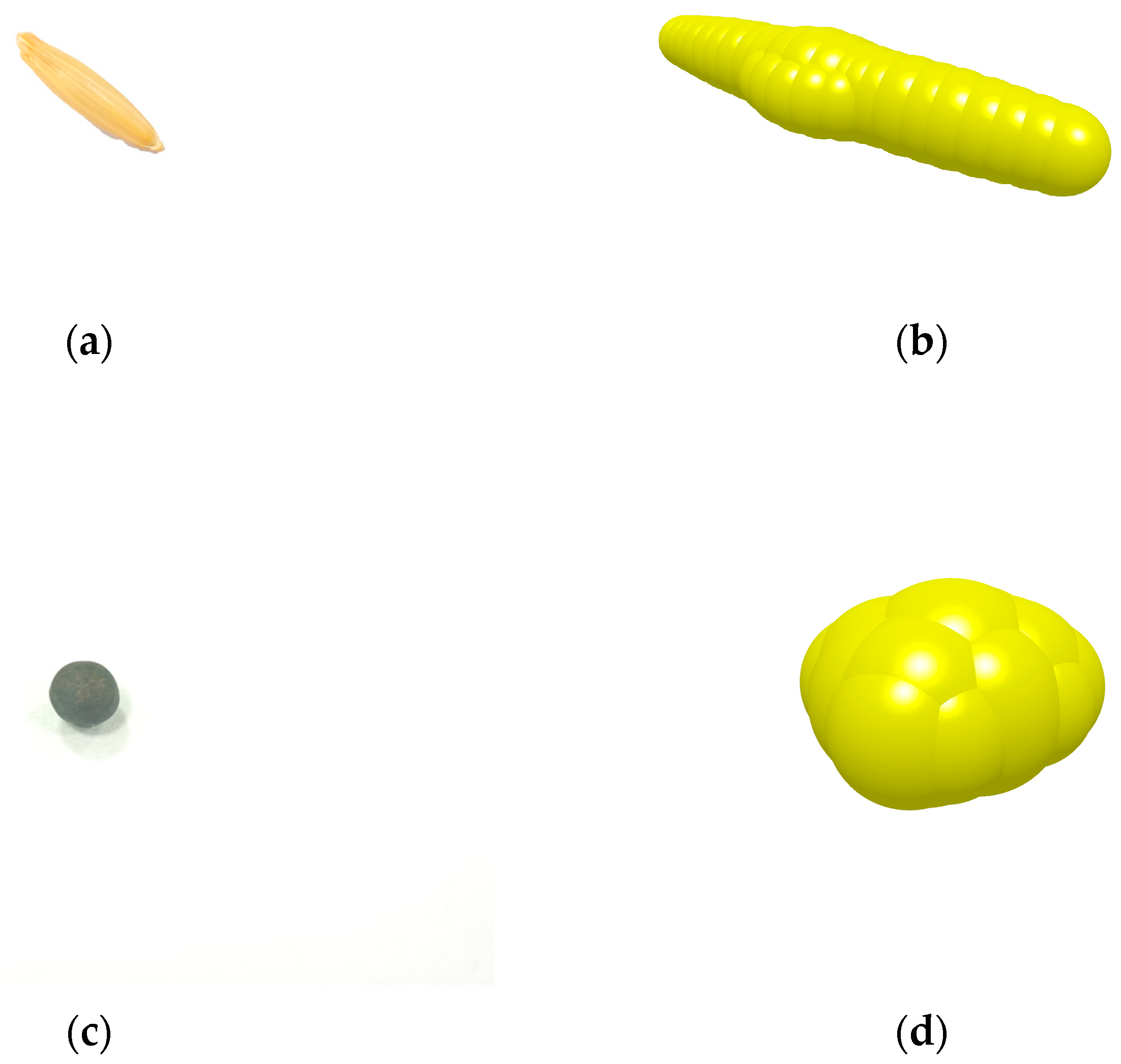

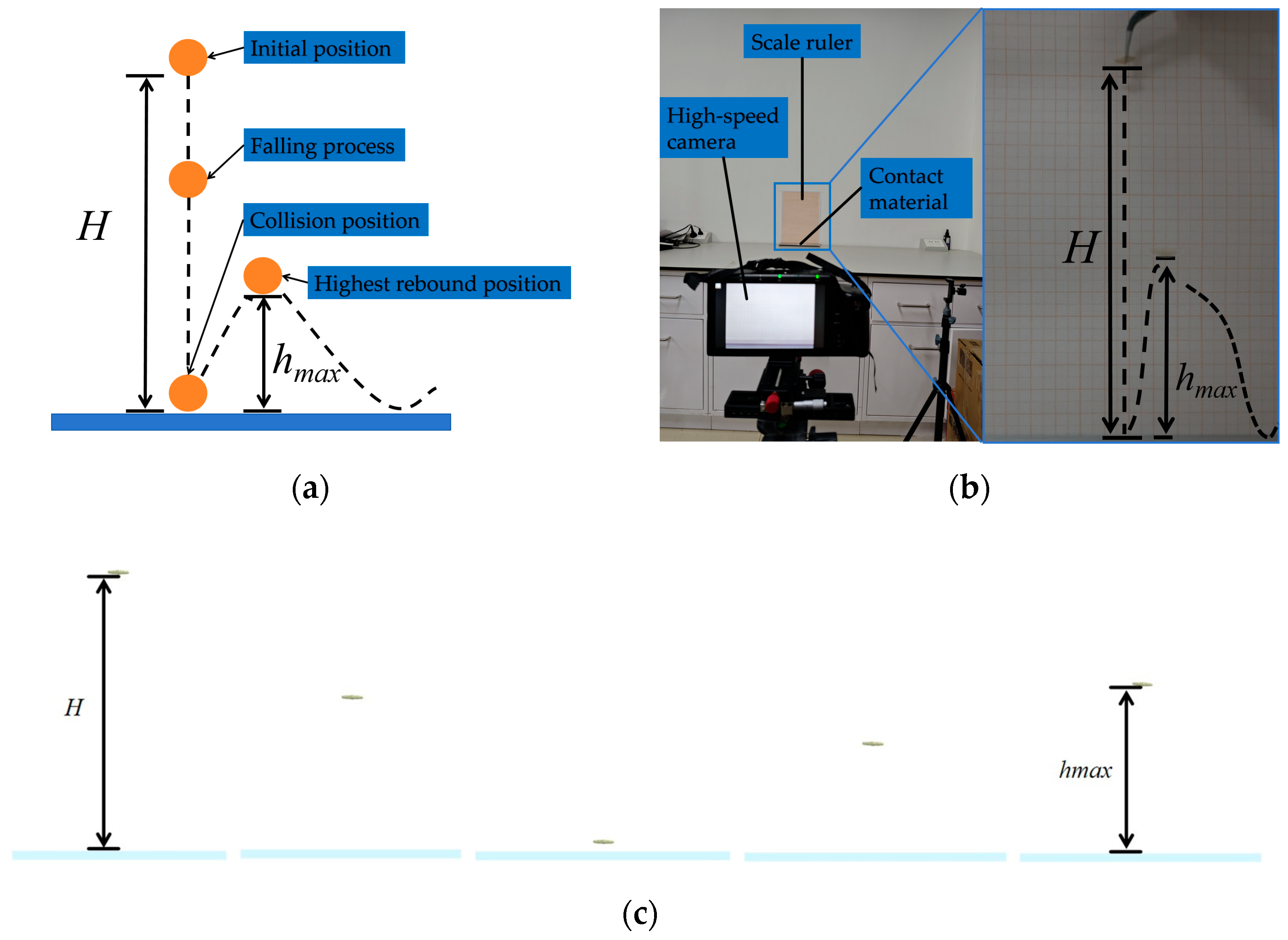

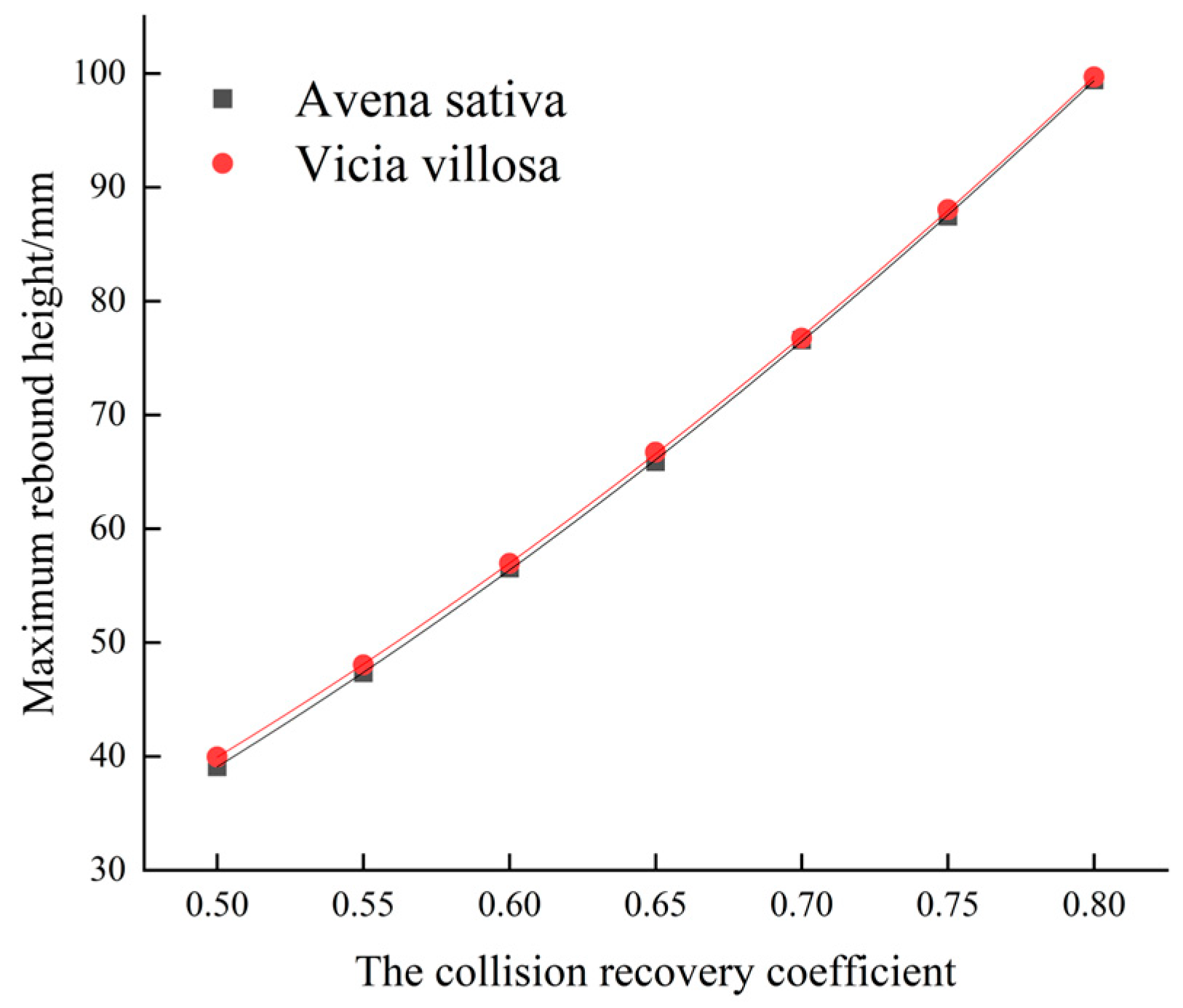

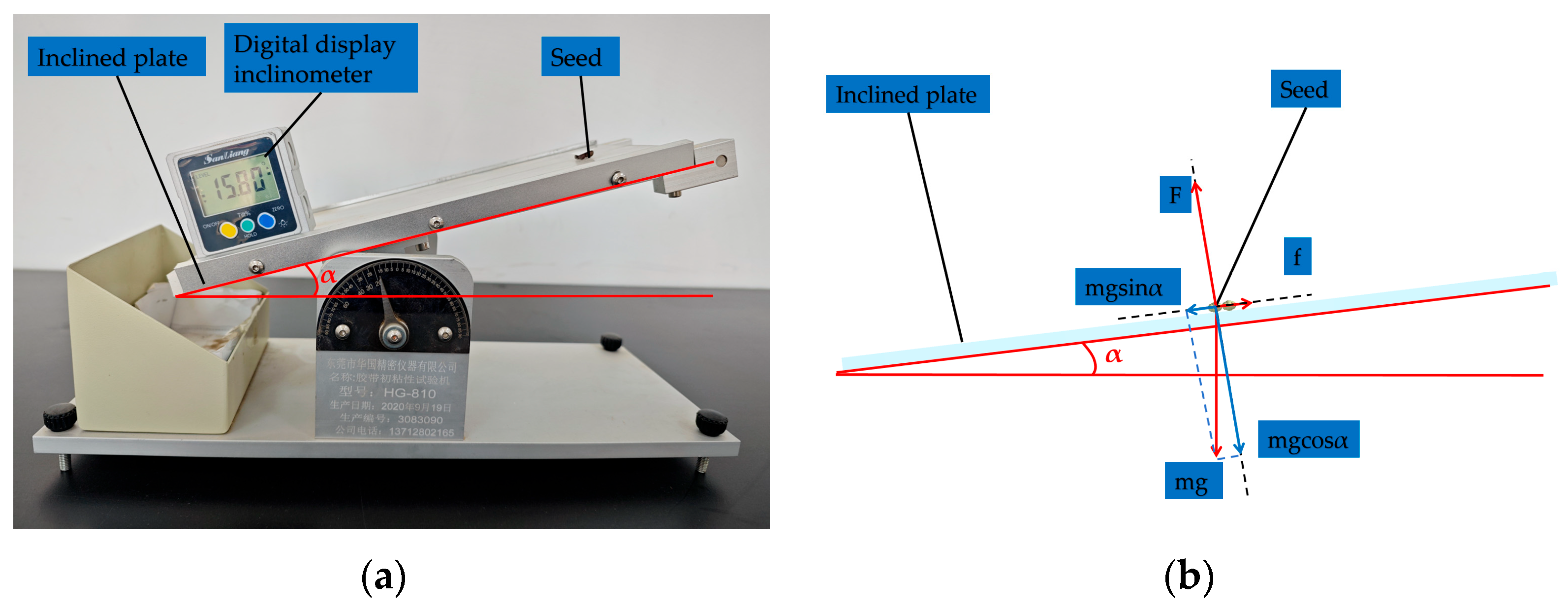

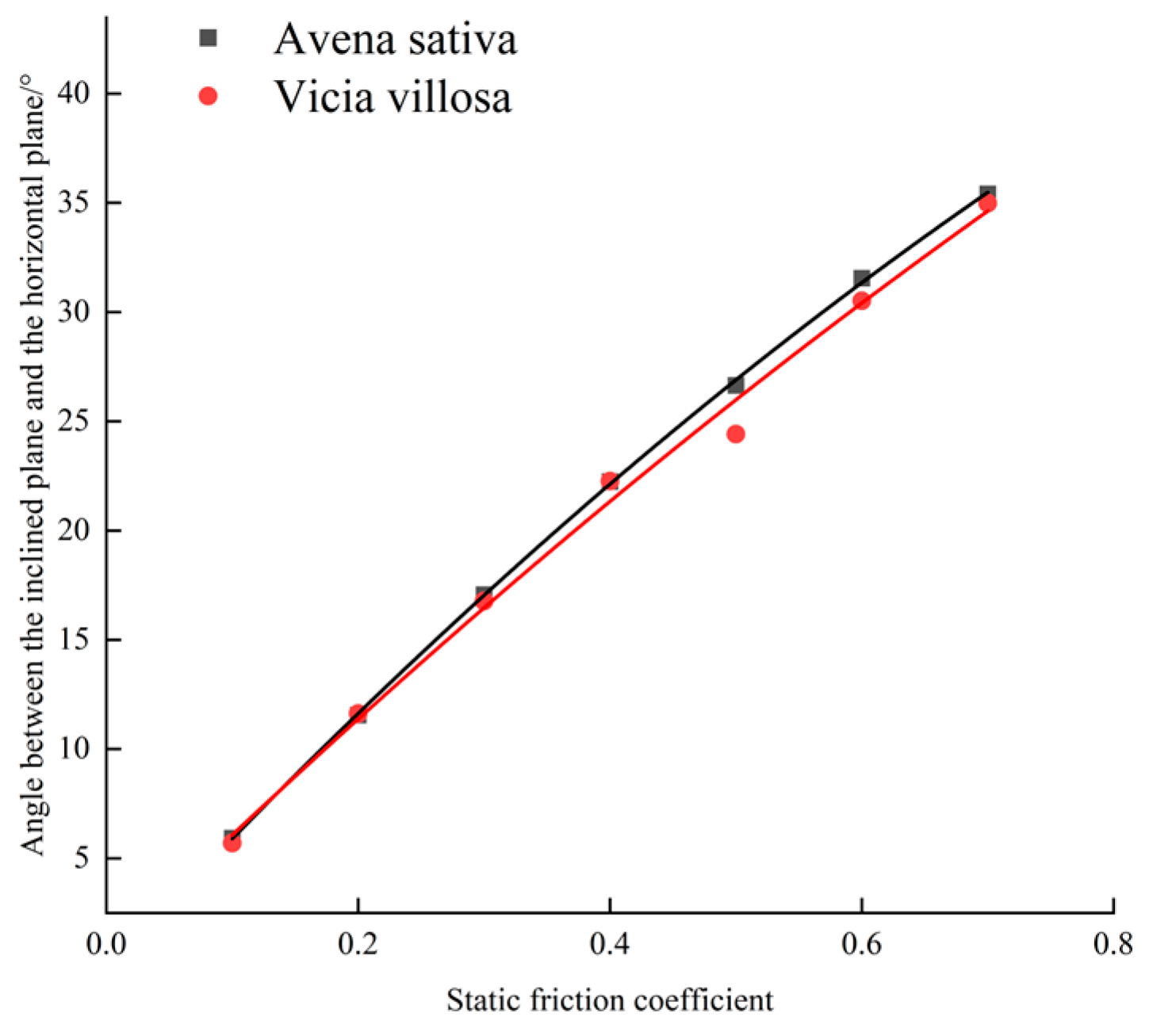

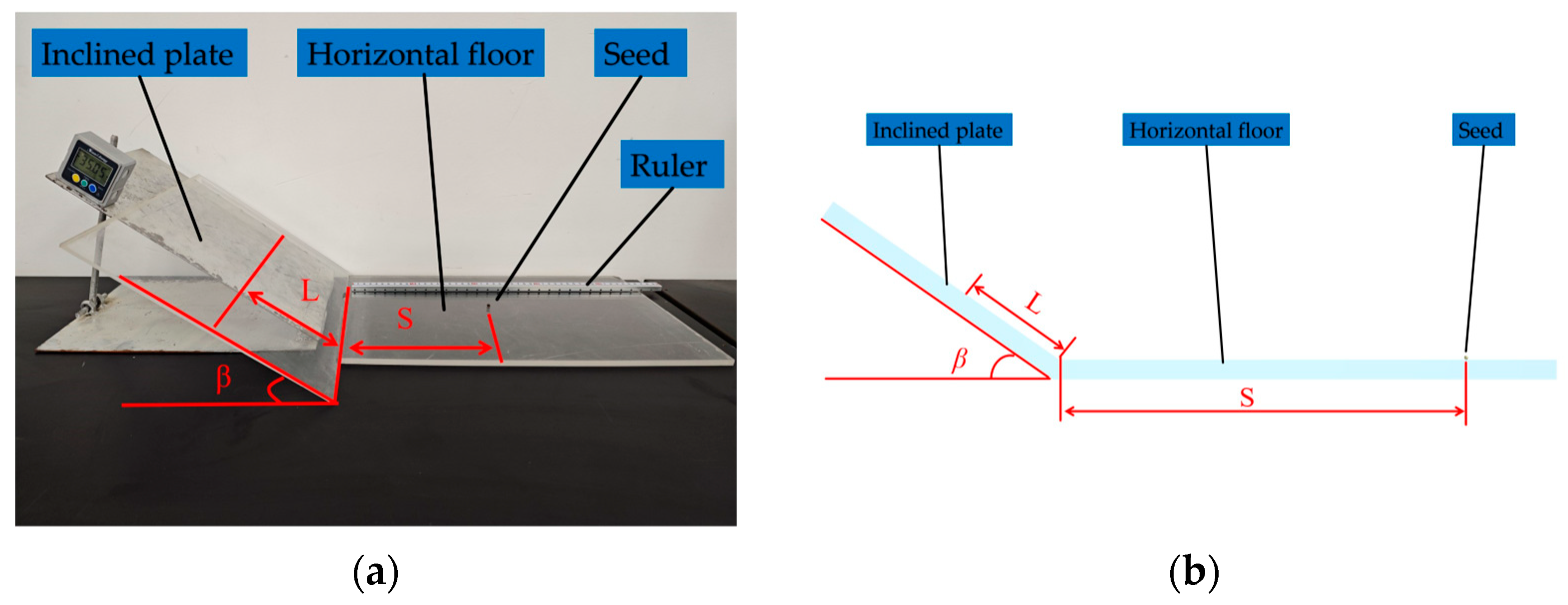

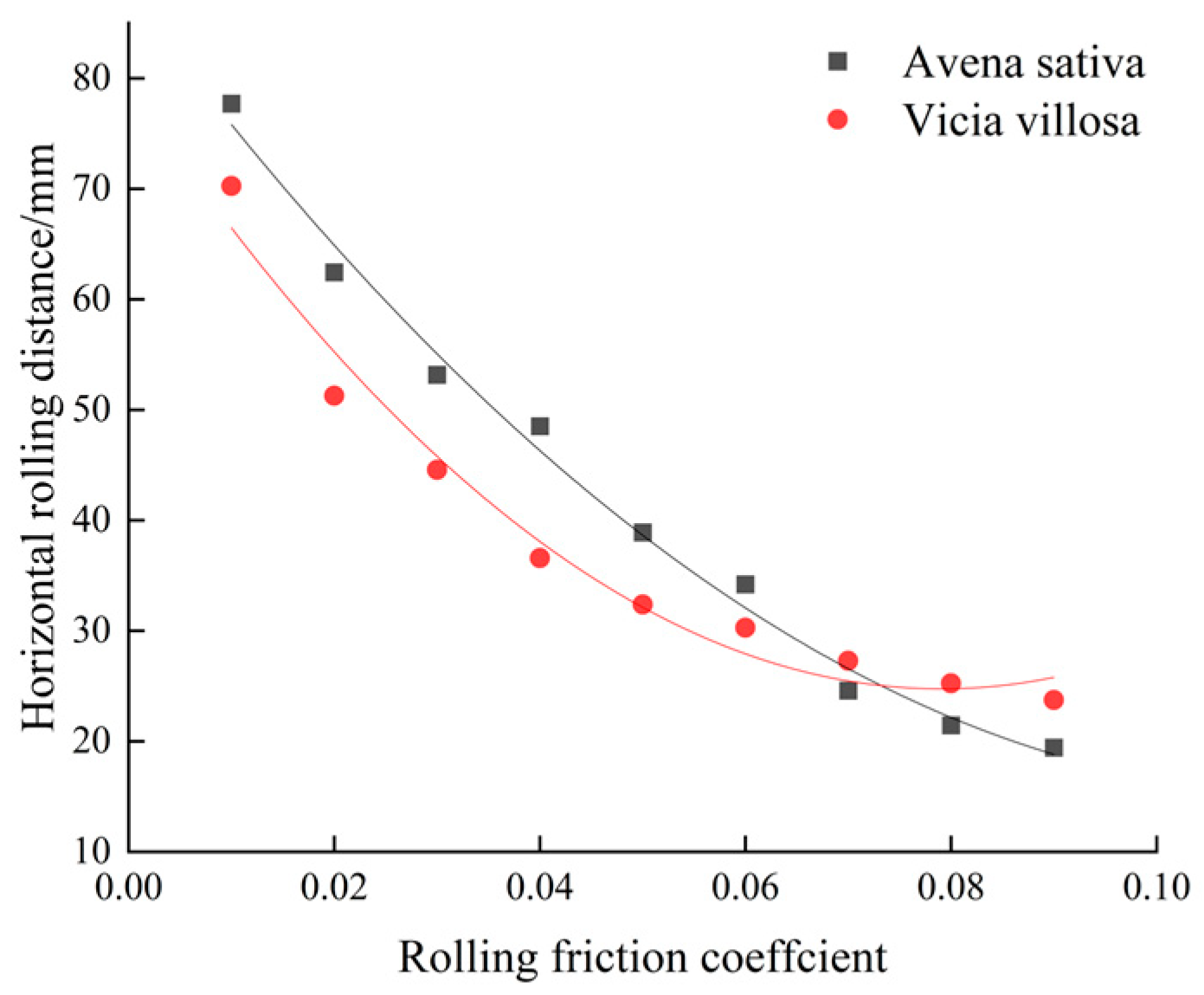

Based on the current research and technological needs, this study focuses on Malva sylvestris and oat seeds as research subjects. First, physical parameters such as triaxial dimensions, thousand-grain weight, density, moisture content, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus are measured to provide empirical data for the setting of particle geometry and elastic variables in the DEM model. Second, free fall, inclined plane sliding, and inclined plane rolling tests are conducted to calibrate the restitution coefficient, static friction coefficient, and rolling friction coefficient between the seeds and PLA material. Additionally, angle of repose tests and a two-level factorial design are used to optimize the response surface of contact parameter combinations for mixed seeds, with the goal of minimizing the relative error between simulated and measured values of the angle of repose to determine the optimal parameter set. On this basis, the DEM models of Malva sylvestris and oats are established using the multi-sphere manual packing method. These models are coupled with Fluent for gas–solid interaction simulations, and the calibrated contact parameters are applied to the simulation of air-assisted, collective seeders. The flow behavior of mixed seeds in the distributor under various inlet wind speeds and mass flow rate conditions, as well as the consistency of seed placement across rows, are systematically analyzed. Finally, by comparing with bench tests, the model’s predictive capability for key response variables such as angle of repose and seed placement variation coefficient is validated. This provides theoretical guidance and data support for the selection of DEM parameters and the structural optimization of pneumatic seeders for seed systems with significant morphological differences in legume–grass mixed sowing.