Multi-Objective Optimization Design and Numerical Study of Water-Cooled Microwave Ablation Antennas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Finite Element Model

2.2. Numerical Evaluation of Antennas

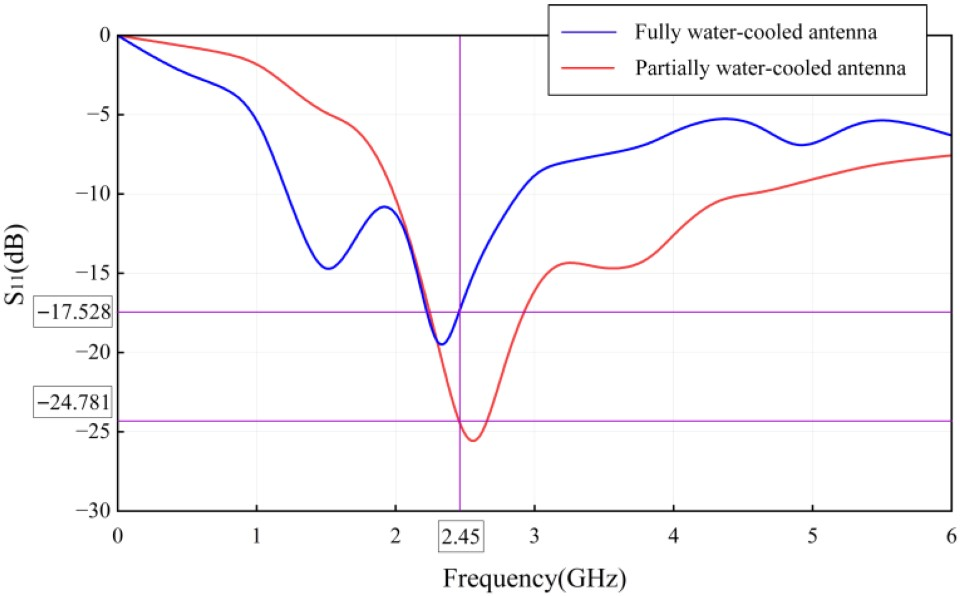

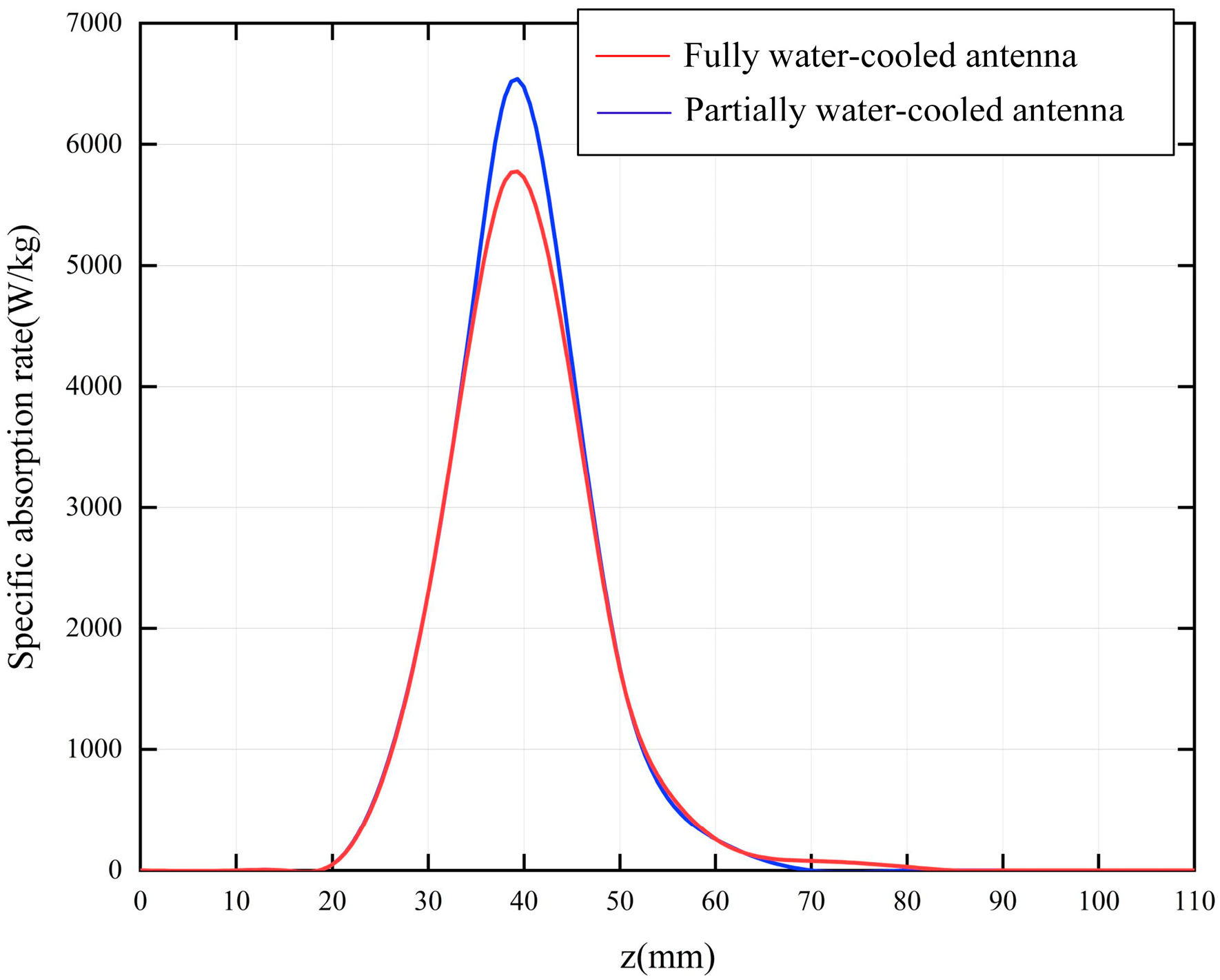

2.2.1. Coupling Power Between Antenna and Biological Tissue

2.2.2. Ablation Volume

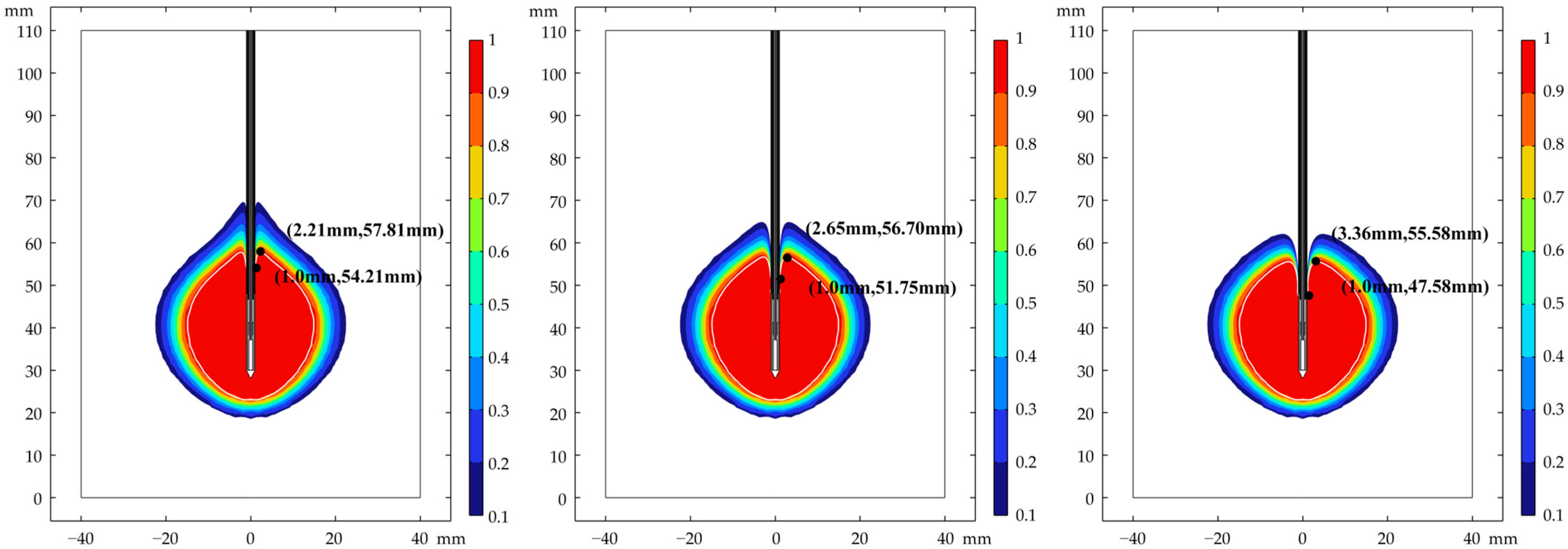

2.2.3. Ablation Roundness

2.3. Multi-Objective Optimization

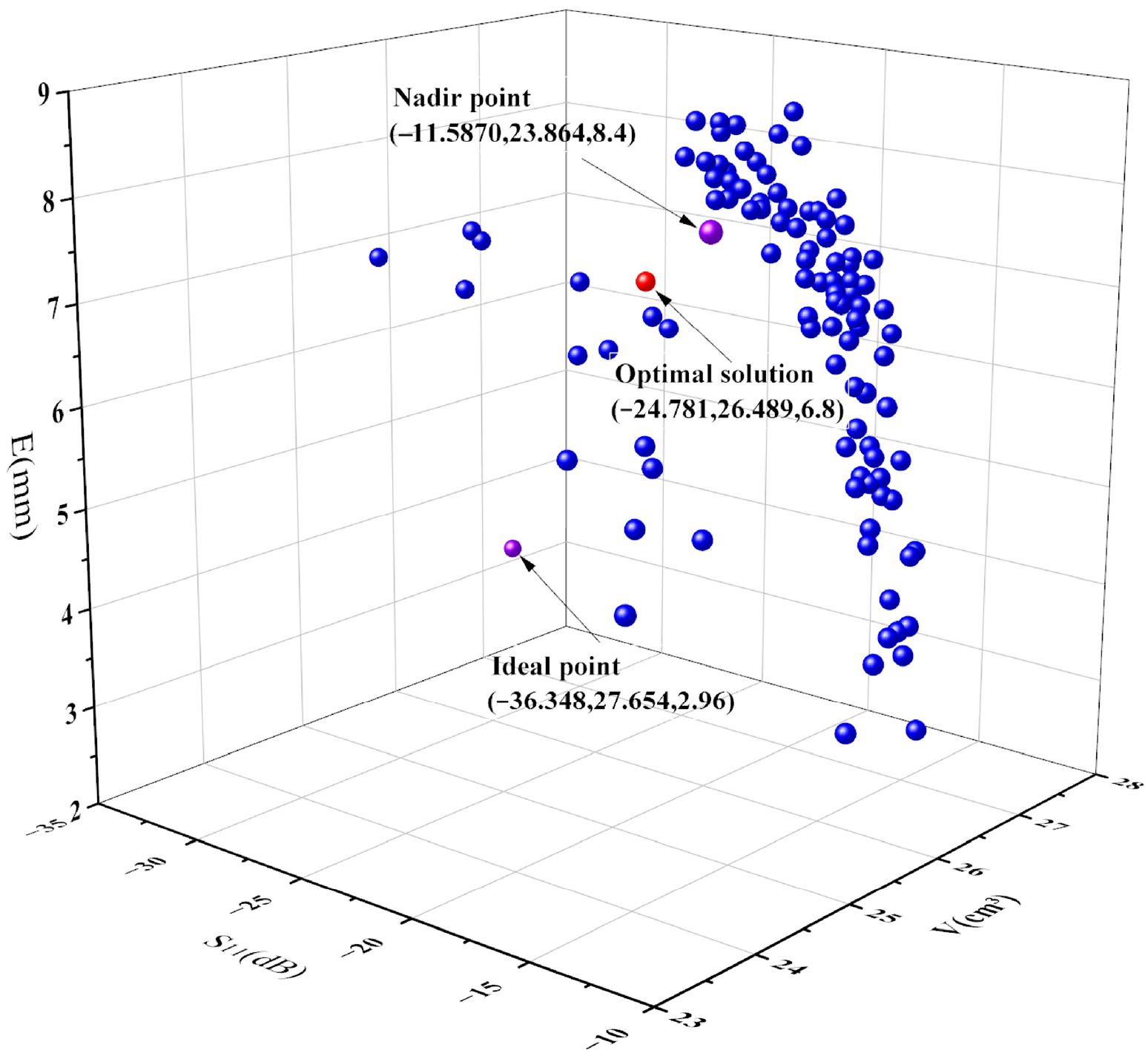

2.4. Multi-Objective Decision-Making

3. Results

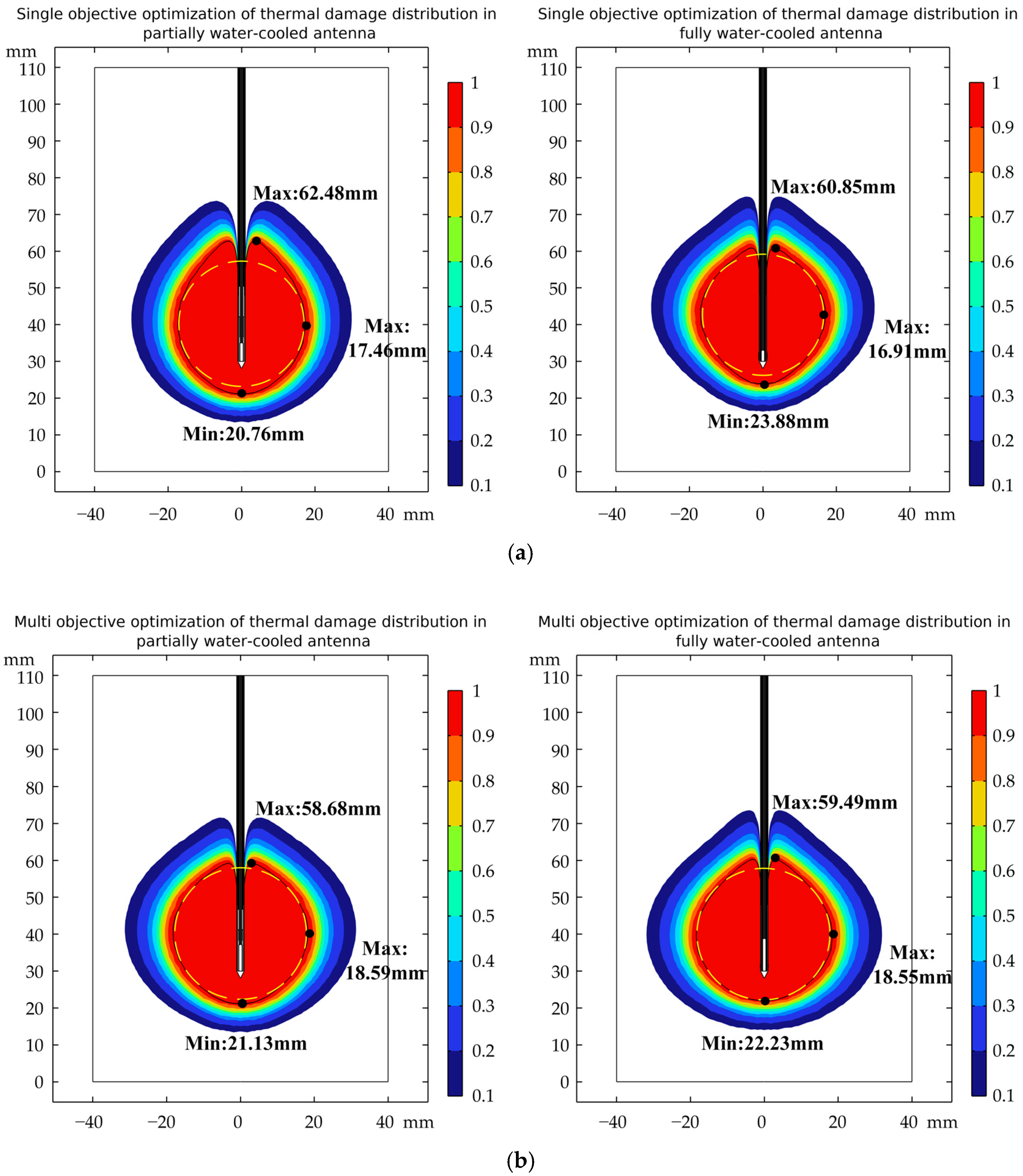

3.1. Analysis of Ablation Performance

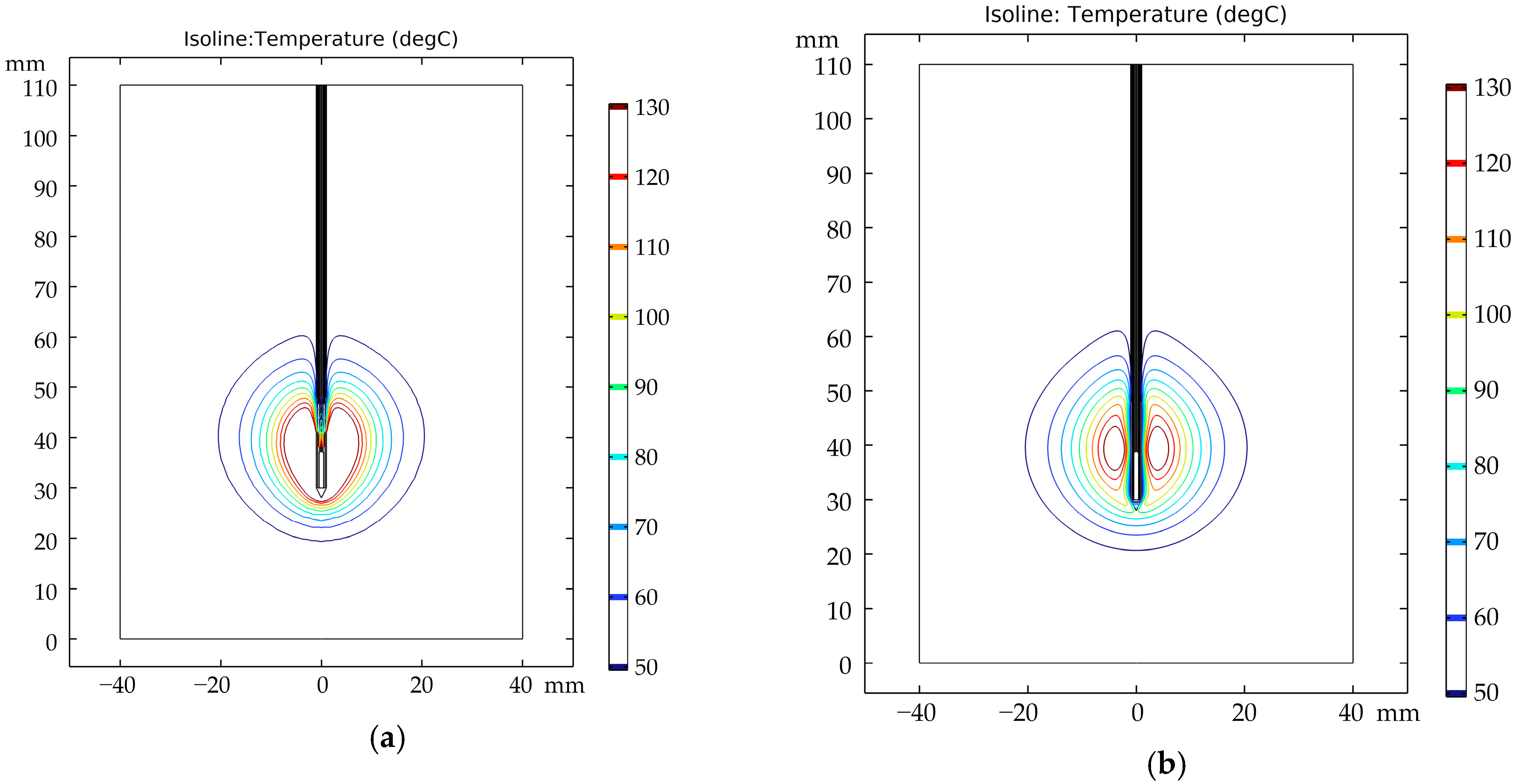

3.2. Distribution of Temperature Field

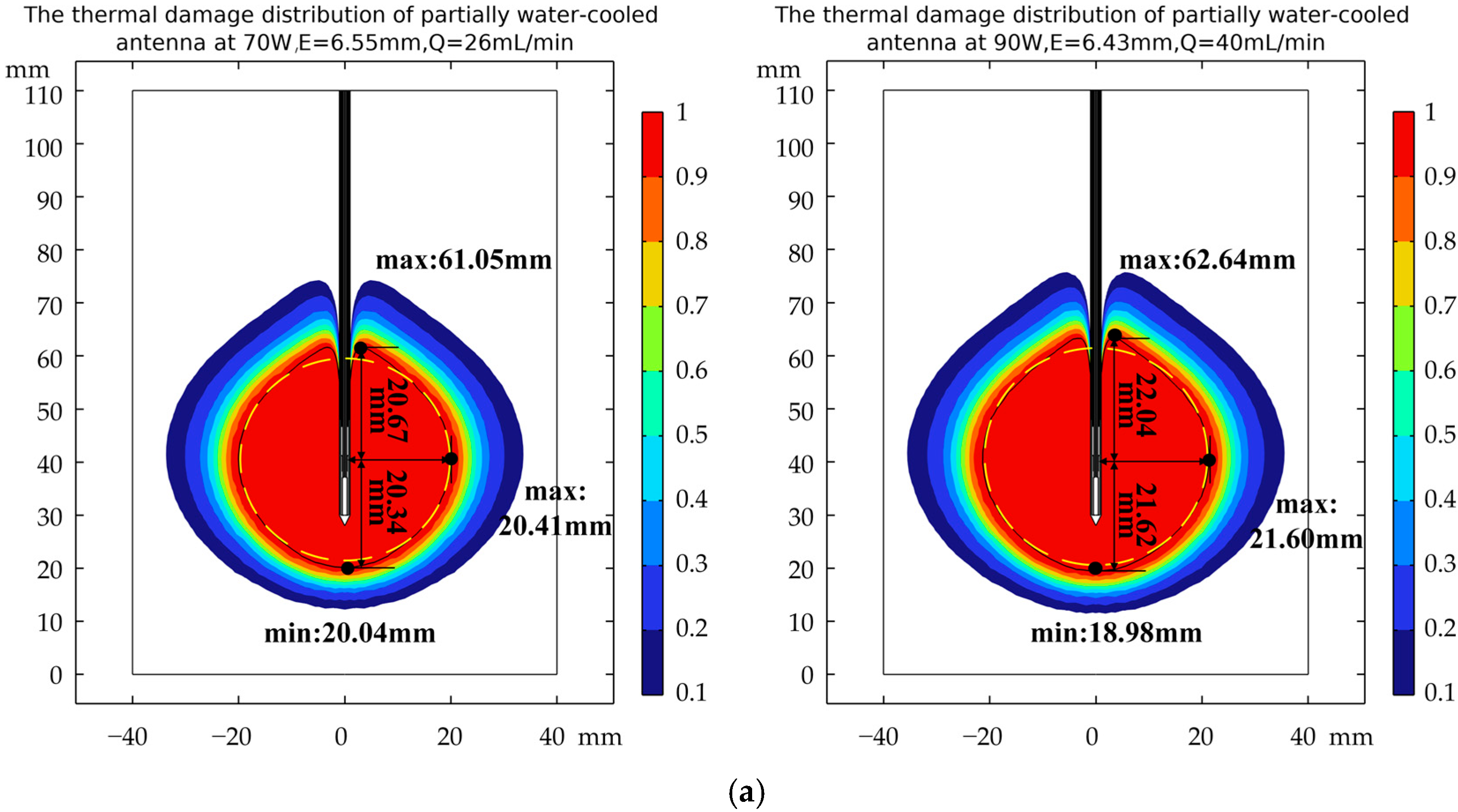

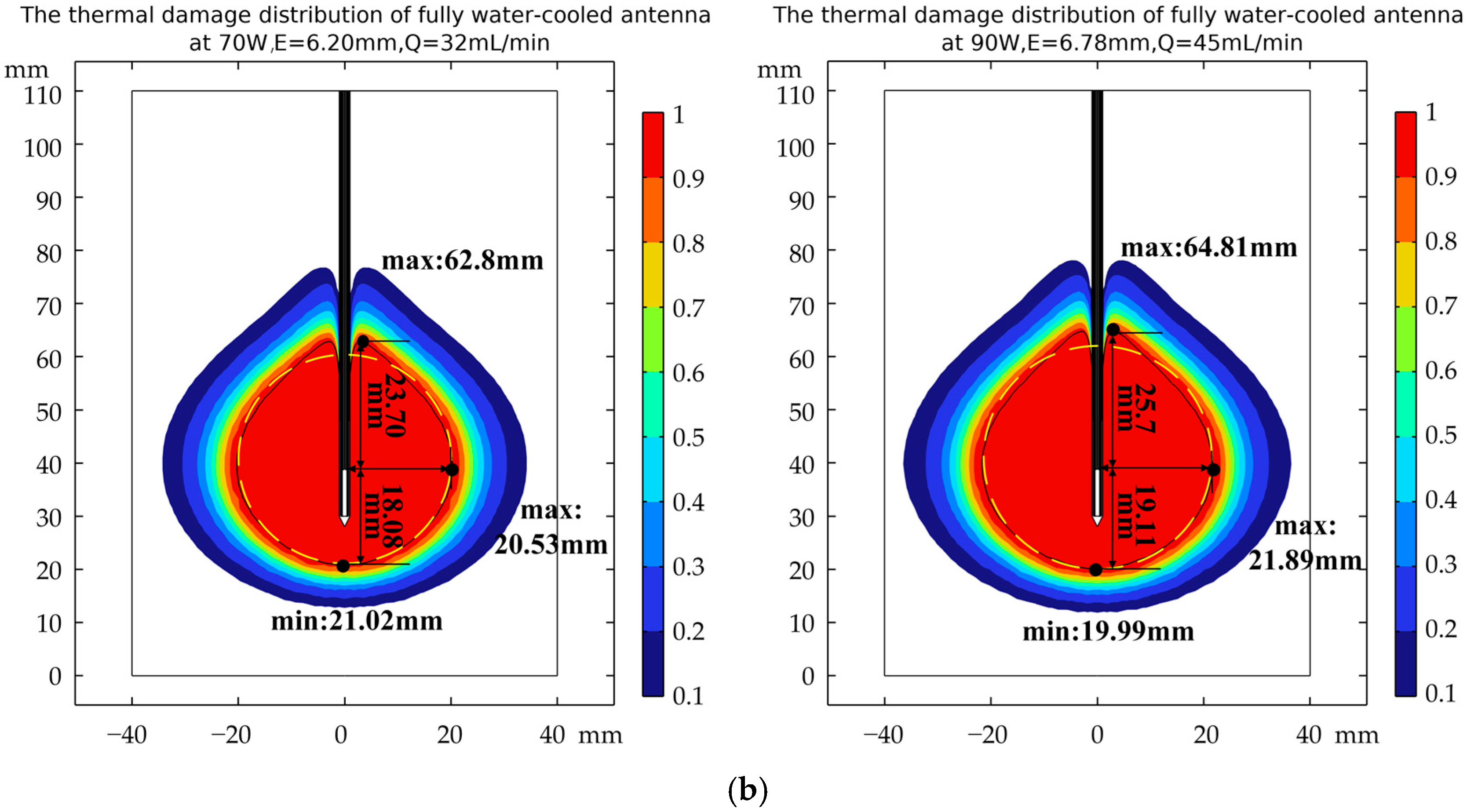

3.3. Verification of Robustness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, X. Microwave Ablation Versus Surgical Resection for Small (≤3 cm) Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Older Patients: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Korean J. Radiol. 2025, 26, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Han, Z.; Liu, F.; Yu, X.; Tan, X.; Han, B.; Dou, J.; Yu, J.; Liang, P. Percutaneous Microwave Ablation Versus Open Surgical Resection for Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 638165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, S.; Shao, X.; Du, H.; Li, P.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Feng, E.; Li, C. Initial experience of the treatment of large glioma with microwave ablation-assisted surgical resection. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2023, 19, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazlollahi, F.; Makary, M.S. Precision oncology: The role of minimally-invasive ablation therapy in the management of solid organ tumors. World J. Radiol. 2025, 17, 98618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Moser, M.A.J.; Zhang, E.M.; Luo, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W. A review of radiofrequency ablation: Large target tissue necrosis and mathematical modelling. Phys. Medica 2016, 32, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Moser, M.A.J.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. Chemical Enhancement of Irreversible Electroporation: A Review and Future Suggestions. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 18, 1533033819874128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.I.; Field, D.; Lynskey, G.E.; Kim, A.Y. Technology of irreversible electroporation and review of its clinical data on liver cancers. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2018, 15, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, C.; Navuluri, R.; Ahmed, O. Percutaneous microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 4467–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Qi, X.; Xin, Y. Effectiveness and safety of percutaneous microwave ablation and radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of pulmonary metastasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2025, 21, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, R.; Bie, Z.; Li, B.; Li, X. Safety and efficacy of co-ablation vs. microwave ablation in the treatment of subpleural stage I non-small cell lung cancer: A comparative study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 5534–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, M.; Belfiore, M.P.; Floridi, C.; Serra, N.; Belfiore, G.; Carmignani, L.; Grasso, R.F.; Mazza, E.; Pusceddu, C.; Brunese, L.; et al. Radiofrequency versus microwave ablation for treatment of the lung tumours: LUMIRA (lung microwave radiofrequency) randomized trial. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, P.; Stefan, S.; Eckhard, K.; Tobias, K.; Tarkan, J.; Romana, U.; Jörg, H.; Daniel, N.; Dietmar, Ö.; Stefan, S. Thermographic real-time-monitoring of surgical radiofrequency and microwave ablation in a perfused porcine liver model. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, C.; Lingnan, S.; Fereidoun, A.; Yahya, R. Efficacy of Lung-Tuned Monopole Antenna for Microwave Ablation: Analytical Solution and Validation in a Ventilator-Controlled ex Vivo Porcine Lung Model. IEEE J. Electromagn. RF Microw. Med. Biol. 2021, 5, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Bertram, J.M.; Converse, M.C.; O’Rourke, A.P.; Webster, J.G.; Hagness, S.C.; Will, J.A.; Mahvi, D.M. A floating sleeve antenna yields localized hepatic microwave ablation. IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 2006, 53, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, R.; Yu, J. Thermal field study of ceramic slot microwave ablation antenna based on specific absorption rate distribution function. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2020, 16, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Moser, M.A.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, B. A review of antenna designs for percutaneous microwave ablation. Phys. Medica 2021, 84, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, Z.; Alexis, O.; Hakan, Y.; Pinar, Y.; Noaman, A.; Eren, B. Laparoscopic microwave thermosphere ablation of malignant liver tumors: An analysis of 53 cases. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, C.; Claudio, A.; Paolo, B.; Stefano, P.; Nevio, T. A minimally invasive antenna for microwave ablation therapies: Design, performances, and experimental assessment. IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 2011, 58, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, C.L. Dual-slot antennas for microwave tissue heating: Parametric design analysis and experimental validation. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 4232–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, R.-G.T.; Jessica, T.-R.C.; Arturo, V.-H.; Lorenzo, L.-S.; Josefina, G.-M. Performance evaluation of a novel cooling system for micro-coaxial antennas designed to treat bone tumors by microwave thermal ablation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 193, 108515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, Z.A.; Nwoye, E.O.; Aweda, M.A.; Oremosu, A.A.; Annunobi, C.C.; Akanmu, O.N. Optimization of dual slot antenna using floating metallic sleeve for microwave ablation. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keangin, P.; Rattanadecho, P.; Wessapan, T. An analysis of heat transfer in liver tissue during microwave ablation using single and double slot antenna. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 38, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.P.; Bottiglieri, A.; Conceição, R.C.; O’Halloran, M.; Farina, L. Characterisation of Ex Vivo Liver Thermal Properties for Electromagnetic-Based Hyperthermic Therapies. Sensors 2020, 20, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Wu, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Z. RF ablation thermal simulation model: Parameter sensitivity analysis. Technol. Health Care 2018, 26, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Palacios, R.; Trujillo-Romero, C.J.; Cepeda-Rubio, M.F.J.; Leija, L.; Hernández, A.V. Heat Transfer Study in Breast Tumor Phantom during Microwave Ablation: Modeling and Experimental Results for Three Different Antennas. Electronics 2020, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhradini, S.S.; Dehkordi, M.M.; Ahmadikia, H. Enhancing liver cancer treatment: Exploring the frequency effects of magnetic nanoparticles for heat-based tumor therapy with microwaves. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 203, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Lin, X.-Q.; Li, C.-N.; Fan, Y.-L. A low-cost invasive microwave ablation antenna with a directional heating pattern. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 038401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglianti, B.L.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Abraham, J.P.; Gorman, J.M.; Sparrow, E.M. Rationalization of thermal injury quantification methods: Application to skin burns. Burns 2014, 40, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarena, T.; Enrique, B. Review of the mathematical functions used to model the temperature dependence of electrical and thermal conductivities of biological tissue in radiofrequency ablation. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etoz, S.; Brace, C.L. Analysis of microwave ablation antenna optimization techniques. Int. J. RF Microw. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2018, 28, e21224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Nan, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Numerical study on thermal field of microwave ablation with water-cooled antenna. Int. J. Hyperth. 2009, 25, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, H.; Clausing, D.; Shahzad, A.; O’Halloran, M.; Dennedy, M.C.; Prakash, P. Microwave antennas for thermal ablation of benign adrenal adenomas. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2019, 5, 025044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zheng, P.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y. A new method for evaluating roundness error based on improved bat algorithm. Measurement 2024, 238, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Saremi, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Coelho, L.d.S. Multi-objective grey wolf optimizer: A novel algorithm for multi-criterion optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 47, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Gong, C.; Li, W.; Liao, C. Multi-Objective Optimization of Pulse Electrochemical Machining Process Parameters by CRITIC-TOPSIS. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2024, 60, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, R.; Qian, L.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zou, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Z. Temperature control and intermittent time-set protocol optimization for minimizing tissue carbonization in microwave ablation. Int. J. Hyperth. 2022, 39, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat (J/kg·K) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 1079 | 3570 | 0.52 |

| Zirconia ceramic | 6050 | 400 | 2.2 |

| PTFE | 800 | 1000 | 0.25 |

| Stainless steel | 8055 | 500 | 16.2 |

| Copper | 8960 | 386 | 401 |

| Material | Relative Permittivity | Conductivity (S/m) | Relative Permeability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 43.03 | 1.69 | 1 |

| Zirconia ceramic | 25 | 0 | 1 |

| PTFE | 2.03 | 0 | 1 |

| Stainless steel | 1 | 1.1 × 106 | 1 |

| Copper | 1 | 5.8 × 107 | 1 |

| Design Variables | Range of Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Partially water-cooled antenna | Length of dipole tip, l1 | 1–20 mm |

| Width of feed gap, w1 | 0.1–10 mm | |

| Length of choke, l2 | 1–10 mm | |

| Location of choke, l3 | 0.1–15 mm | |

| Flow rate of cooling water, Q1 | 10–40 mL/min | |

| Fully water-cooled antenna | Length of dipole tip, l4 | 1–20 mm |

| Width of feed gap, w2 | 0.1–10 mm | |

| Flow rate of cooling water, Q2 | 10–40 mL/min |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Population size | 120 |

| Number of generations | 50 |

| Size of external archive | 120 |

| Repository Member Selection Pressure | 2 |

| Leader Selection Pressure | 4 |

| Grid Inflation Parameter | 0.1 |

| Number of Grids per each Dimension | 10 |

| Design Variables | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Partially water-cooled antenna | Length of dipole tip, l1 | 7.13 mm |

| Width of feed gap, w1 | 1.08 mm | |

| Length of choke, l2 | 5.51 mm | |

| Location of choke, l3 | 3.02 mm | |

| Flow rate of cooling water, Q1 | 18 mL/min | |

| Fully water-cooled antenna | Length of dipole tip, l4 | 8.77 mm |

| Width of feed gap, w2 | 0.68 mm | |

| Flow rate of cooling water, Q2 | 22 mL/min |

| (dB) | (cm3) | E (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partially water-cooled antenna | Single objective | −27.798 | 25.753 | 9.54 |

| Multi-objective | −24.781 | 26.489 | 6.80 | |

| Fully water-cooled antenna | Single objective | −8.889 | 22.013 | 5.79 |

| Multi-objective | −17.528 | 26.065 | 5.48 | |

| Relative Permittivity | S11 (dB) | |

|---|---|---|

| Partially water-cooled antenna | 47.33 | −22.644 |

| 43.03 | −24.781 | |

| 38.73 | −26.204 | |

| Fully water-cooled antenna | 47.33 | −18.023 |

| 43.03 | −17.528 | |

| 38.73 | −17.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Lu, R.; Xu, Q. Multi-Objective Optimization Design and Numerical Study of Water-Cooled Microwave Ablation Antennas. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13049. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413049

Zhang P, Lu R, Xu Q. Multi-Objective Optimization Design and Numerical Study of Water-Cooled Microwave Ablation Antennas. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13049. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413049

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peiwen, Rongjian Lu, and Qiang Xu. 2025. "Multi-Objective Optimization Design and Numerical Study of Water-Cooled Microwave Ablation Antennas" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13049. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413049

APA StyleZhang, P., Lu, R., & Xu, Q. (2025). Multi-Objective Optimization Design and Numerical Study of Water-Cooled Microwave Ablation Antennas. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13049. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413049