Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Narrative Review of Biomechanical Foundations, Clinical Protocols, and Technological Advances

Abstract

1. Introduction

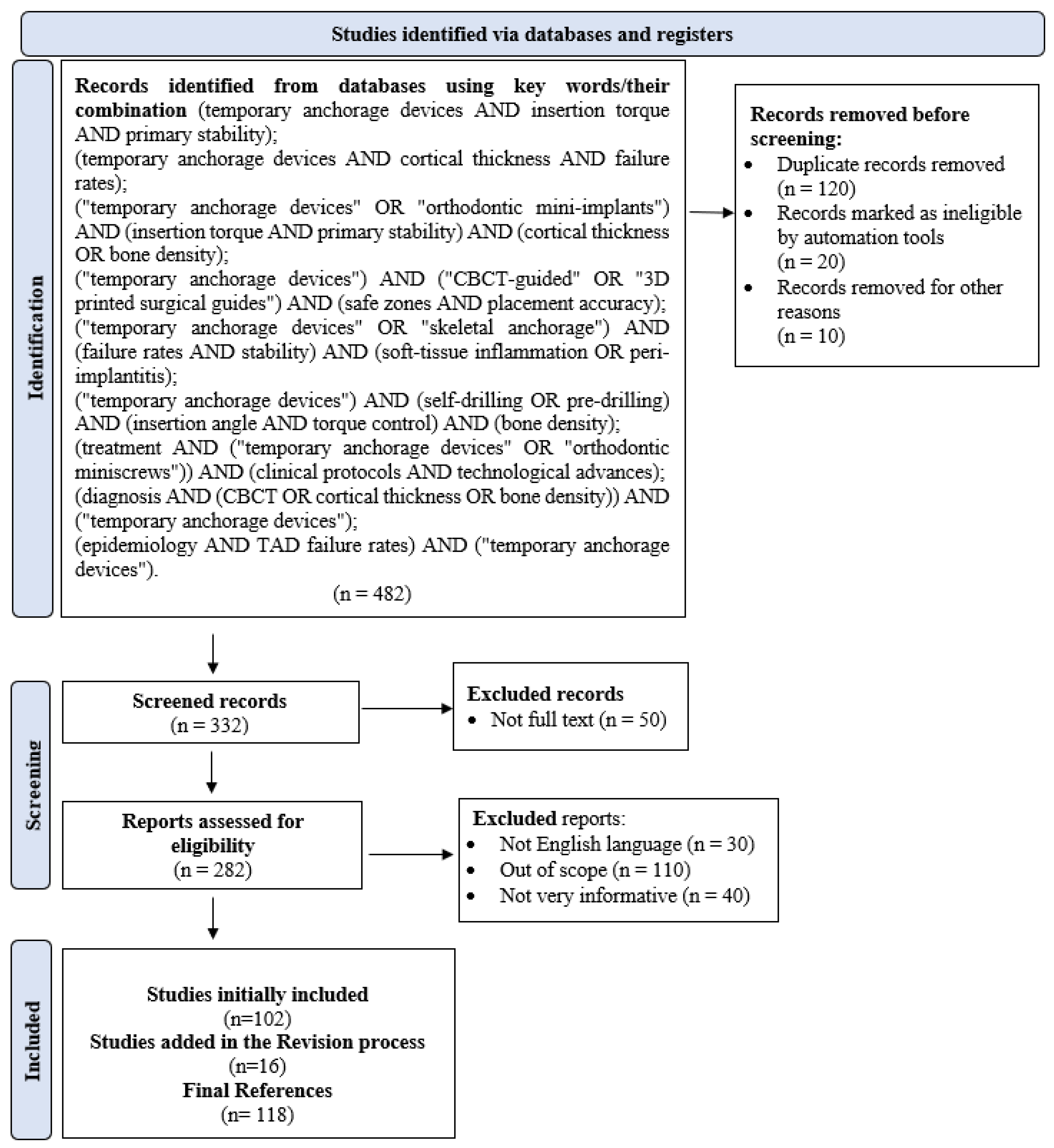

2. Methodology of Research

3. Types of Anchorage and Biomechanical Principles

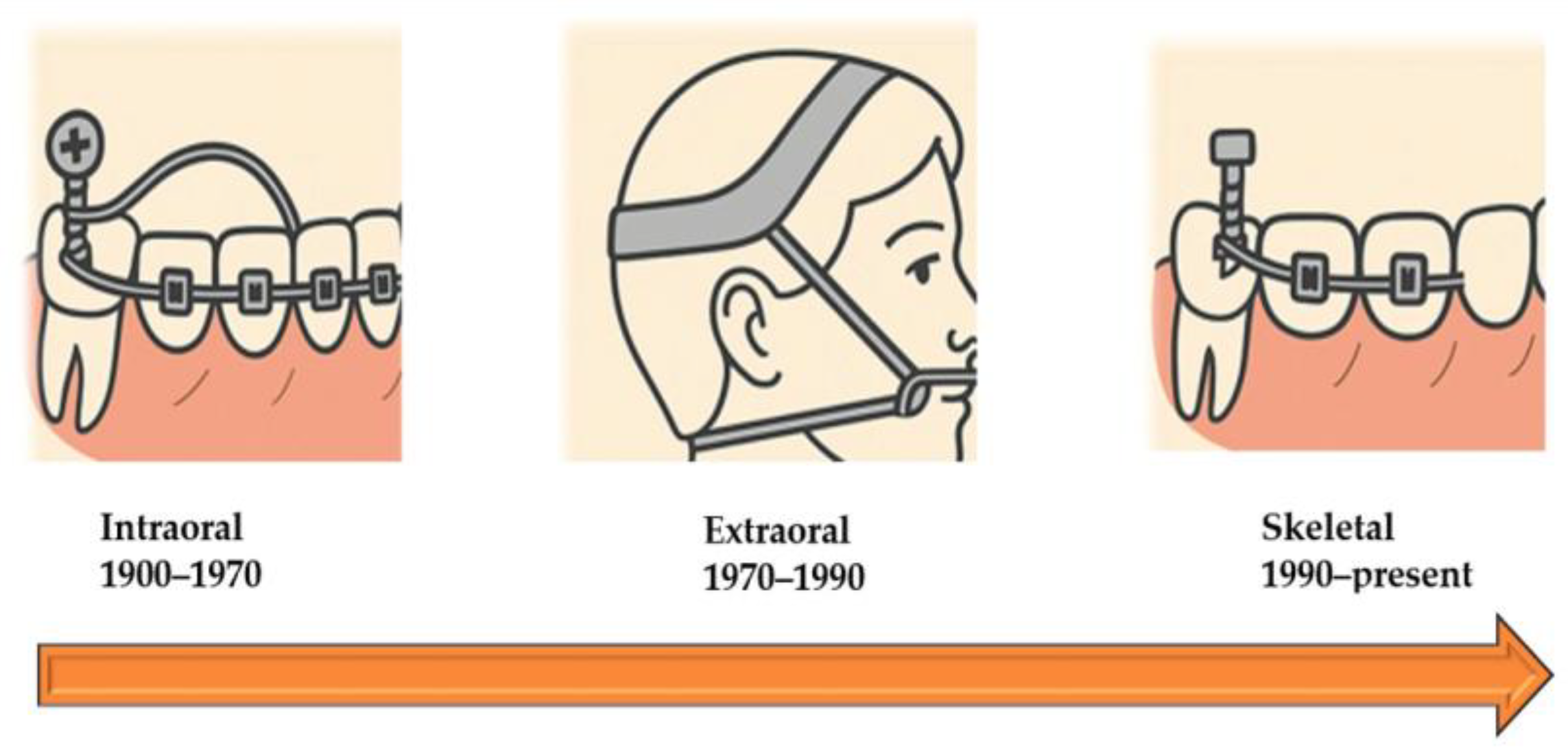

3.1. Classification of Orthodontic Anchorage

3.2. Biomechanical Foundations of Anchorage

3.3. Indications and Comparative Use of Anchorage Types

3.4. Biomechanical Advantages and Limitations of TADs

4. Temporary Anchorage Devices: Design and Selection

4.1. General Design Principles

4.2. Structural Design: Head, Neck, and Thread Geometry

4.3. Insertion Torque and Stability

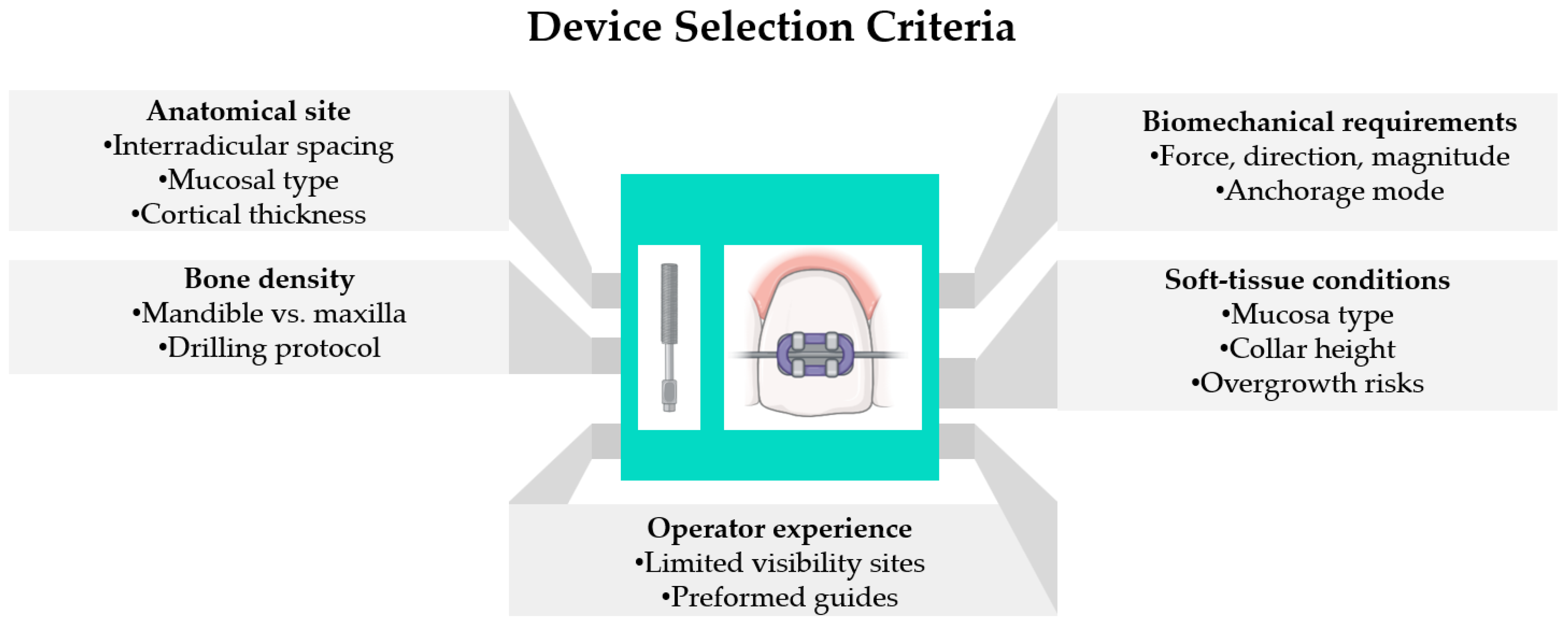

4.4. Device Selection Criteria

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Soft-Tissue Response, Patient Comfort, Hygiene, and Inflammation: Critical Appraisal

5. Clinical Technique, Stability, and Evidence-Based Outcomes

5.1. Insertion Techniques, Protocols, and Decision Pathways

5.2. Stability Determinants, Complications, and Risk Management

5.3. Clinical Guidelines and Evidence-Based Recommendations

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone-beam computed tomography |

| EA | Evidence analysis (implicit in evidence-level discussions) |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

| MARPE | Miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion |

| OCEBM | Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine |

| OHRQoL | Oral health–related quality of life |

| PD | Probing depth |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| TAD | Temporary anchorage device |

References

- Ramírez-Ossa, D.M.; Escobar-Correa, N.; Ramírez-Bustamante, M.A.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A. An Umbrella Review of the Effectiveness of Temporary Anchorage Devices and the Factors That Contribute to Their Success or Failure. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxi, S.; Bhatia, V.; Tripathi, A.; Prasad Dubey, M.; Kumar, P.; Mapare, S. Temporary Anchorage Devices. Cureus 2023, 15, e44514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Kuitert, R.; Wang, M.; Kou, W.; Hu, M.; Liu, Y. Progress of Surface Modifications of Temporary Anchorage Devices: A Review. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 20, 022011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, N.; Siemers, P. Re: Viewing Observation. The Philosophy of Medical Imaging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1392, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cunha, A.C.; da Veiga, A.M.A.; Masterson, D.; Mattos, C.T.; Nojima, L.I.; Nojima, M.C.G.; Maia, L.C. How Do Geometry-Related Parameters Influence the Clinical Performance of Orthodontic Mini-Implants? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Namura, Y.; Motoyoshi, M. Optimal Insertion Torque for Orthodontic Anchoring Screw Placement: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.D.; Ha, A.; Lee, S.; Mohajeri, A.; Schwartz, C.; Hung, M. Where You Place, How You Load: A Scoping Review of the Determinants of Orthodontic Mini-Implant Success. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamaki, T.; Watanabe, K.; Iwasa, A.; Deguchi, T.; Horiuchi, S.; Tanaka, E. Thread Shape, Cortical Bone Thickness, and Magnitude and Distribution of Stress Caused by the Loading of Orthodontic Miniscrews: Finite Element Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Lin, Y.; Ji, M.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Tan, J.; Jia, R.; Li, J. Effects of Exposure Length, Cortical and Trabecular Bone Contact Areas on Primary Stability of Infrazygomatic Crest Mini-Screws at Different Insertion Angles. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, S.H.P.; Sufarnap, E.; Bahirrah, S. The Orthodontic Mini-Implants Failures Based on Patient Outcomes: Systematic Review. Eur. J. Dent. 2024, 18, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santmartí-Oliver, M.; Jorba-García, A.; Moya-Martínez, T.; De-la-Rosa-Gay, C.; Camps-Font, O. Safety and Accuracy of Guided Interradicular Miniscrew Insertion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stursa, L.; Wendl, B.; Jakse, N.; Pichelmayer, M.; Weiland, F.; Antipova, V.; Kirnbauer, B. Accuracy of Palatal Orthodontic Mini-Implants Placed Using Fully Digital Planned Insertion Guides: A Cadaver Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronsivalle, V.; Venezia, P.; Bennici, O.; D’Antò, V.; Leonardi, R.; Giudice, A. Lo Accuracy of Digital Workflow for Placing Orthodontic Miniscrews Using Generic and Licensed Open Systems. A 3d Imaging Analysis of Non-Native.Stl Files for Guided Protocols. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindanil, T.; Marinho-Vieira, L.E.; De-Azevedo-Vaz, S.L.; Jacobs, R. A Unique Artificial Intelligence-Based Tool for Automated CBCT Segmentation of Mandibular Incisive Canal. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2023, 52, 20230321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Sharma, D.; Thakur, G.; Gurung, D.; Thakur, A. Basic Principles of Anchorage: A Review. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 12, 4378–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Su, X.; Lei, Y. Analysis of the Efficacy of Conventional, Skeletal and Invisible Orthodontic Appliance for Upper Molar Distalization in Class II Malocclusion Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Tandon, A.; Chandrasekaran, D.; Purushothaman, D.; Katepogu, P.; Mohan, R.; Angrish, N. Anchorage and Stability of Orthodontic Mini Implants in Relation to Length and Types of Implants. Cureus 2024, 16, e73056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelo, V.; Olate, G.; Brito, L.; Sacco, R.; Olate, S. Tooth Movement with Dental Anchorage vs. Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. J. Orthod. Sci. 2024, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, G.; Volcheski, F.; Petrovska, J.; Endjekcheva, S. Extraoral Orthopedic Appliances-Headgear, Face Mask and Chin Cup—A Review Article. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2023, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.S.; Parmar, I.; Digumarthi, U.K.; Parmar, J.; Quraishi, A.; Patel, K.; Shah, A.; Shah, K.; Jani, B.; Arora, M.A. Temporary Anchorage Device: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e81617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manea, A.; Dinu, C.; Băciuţ, M.; Buduru, S.; Almășan, O. Intrusion of Maxillary Posterior Teeth by Skeletal Anchorage: A Systematic Review and Case Report with Thin Alveolar Biotype. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakra, O.; Datana, S.; Walia, B.S.; Soni, P.; Joshi, R.K. Assessment of Anchorage Loss with Conventional versus Contemporary Method of Intraoral Anchorage: A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Dent. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umalkar, S.S.; Jadhav, V.V.; Paul, P.; Reche, A. Modern Anchorage Systems in Orthodontics. Cureus 2022, 14, e31476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, I.; Bondemark, L. Orthodontic Anchorage: A Systematic Review. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.-H. Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 144. [Google Scholar]

- Mothobela, T.F.; Sethusa, M.; Khan, M.I. The Use of Temporary Skeletal Anchorage Devices amongst South African Orthodontists. South Afr. Dent. J. 2016, 71, 513–517. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.-C.J.; Lai, E.H.-H.; Chang, J.Z.-C.; Chen, I.; Chen, Y.-J. Comparison of Treatment Outcomes between Skeletal Anchorage and Extraoral Anchorage in Adults with Maxillary Dentoalveolar Protrusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 134, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podda, R.; Imondi, F.; De Stefano, A.A.; Horodynski, M.; Vernucci, R.A.; Galluccio, G. Clinical Outcomes of Skeletal Anchorage Versus Conventional Anchorage in the Class III Orthopaedic Treatment in Growing Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Turkish J. Orthod. 2025, 38, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jia, T.T.; Wang, Z. Comparative Analysis of Anchorage Strength and Histomorphometric Changes after Implantation of Miniscrews in Adults and Adolescents: An Experimental Study in Beagles. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, R.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Jin, Z. Anchorage Loss of the Posterior Teeth under Different Extraction Patterns in Maxillary and Mandibular Arches Using Clear Aligner: A Finite Element Study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möbs, J.; Stuhrmann, G.; Wippermann, S.; Heine, J. Optical Properties and Metal-Dependent Charge Transfer in Iodido Pentelates. Chempluschem 2023, 88, e202200403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.M.; Shibl, L.A.; Dehis, H.M.; Mostafa, Y.A.; El-Beialy, A.R. Evaluation of Anchorage Loss after En Masse Retraction in Orthodontic Patients with Maxillary Protrusion Using Friction vs Frictionless Mechanics: Randomized Clinical Trial. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Ahmed, N.; Younus, A.A.; Ranjan, R.B.K. Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Review. IP Indian J. Orthod. Dentofac. Res. 2020, 6, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.M.; Al-Sabbagh, R.; Hajeer, M.Y. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Platelet-Rich Plasma Compared to the Injectable Platelet-Rich Fibrin on the Rate of Maxillary Canine Retraction: A Three-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, 46, cjad056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, J.H.; Son, D.-W.; Choi, T.-H. Comparison of Treatment Effects between Two Types of Facemasks in Early Class III Patients. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havakeshian, G.; Koretsi, V.; Eliades, T.; Papageorgiou, S.N. Effect of Orthopedic Treatment for Class III Malocclusion on Upper Airways: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Kumar, V.; Verma, R.K.; Singh, S.P.; Sharma, S. Effectiveness of Mini-Screw and Nance Palatal Arch for Anchorage Control Following Segmental Maxillary Canine Retraction in Adolescents with Angle Class I Crowding Using 3D Digital Models: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2025, 14, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.E.; Kim, J.-Y.; Jung, H.-D.; Park, J.J.; Choi, Y.J. Posttreatment Stability of an Anterior Open-Bite by Molar Intrusion Compared with 2-Jaw Surgery—A Retrospective Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 6607–6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akl, H.E.; Abouelezz, A.M.; El Sharaby, F.A.; El-Beialy, A.R.; El-Ghafour, M.A. Force Magnitude as a Variable in Maxillary Buccal Segment Intrusion in Adult Patients with Skeletal Open Bite. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M.; Afzoon, S.; Karandish, M.; Parastar, M. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of the Cortical and Cancellous Bone Density and Thickness for Miniscrew Insertion: A CBCT Study of Interradicular Area of Adults with Different Facial Growth Pattern. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-P.; Tsai, M.-T.; Yu, J.-H.; Huang, H.-L.; Hsu, J.-T. Bone Quality Affects Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrews. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswal, S.; Deshmukh, S.V.; Agarkar, S.S.; Durkar, S.; Mastud, C.; Rahalkar, J.S. In Vivo Comparison of the Efficiency of En-Masse Retraction Using Temporary Anchorage Devices with and Without Orthodontic Appliances on the Posterior Teeth. Turkish J. Orthod. 2022, 35, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golshah, A.; Gorji, K.; Nikkerdar, N. Effect of Miniscrew Insertion Angle in the Maxillary Buccal Plate on Its Clinical Survival: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamurali, V.; Magesh, V.; Harikrishnan, P. Effect of Cortical Bone Thickness on Shear Stress and Force in Orthodontic Miniscrew-Bone Interface—A Finite Element Analysis. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2024, 10, 055013. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, J.; Rumin, K.; Sarul, M.; Kawala, B. Effect of the Increasing Operator’s Experience on the Miniscrew Survival Rate. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioana, T.R.; Boeru, F.G.; Mitruț, I.; Rauten, A.-M.; Elsaafin, M.; Ionescu, M.; Staicu, I.E.; Manolea, H.O. Analysis of Insertion Torque of Orthodontic Mini-Implants Depending on the System and the Morphological Substrate. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Y.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chang, S. Primary Stability Analysis of the Torque-Resistant Orthodontic Miniscrew Anchorage. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221081580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methawit, P.; Uezono, M.; Ogasawara, T.; Techalertpaisarn, P.; Moriyama, K. Cortical Bone Microdamage Affects Primary Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrew. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2023, 12, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.E.; Vanz, V.; Chiqueto, K.; Janson, G.; Ferreira, E. Mechanical Strength of Stainless Steel and Titanium Alloy Mini-Implants with Different Diameters: An Experimental Laboratory Study. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.W.; Park, Y.-S. Revisiting the Complications of Orthodontic Miniscrew. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8720412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schätzle, M.A.; Hersberger-Zurfluh, M.; Patcas, R. Factors Influencing the Removal Torque of Palatal Implant Used for Orthodontic Anchorage. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalu, D.; Simon, V.; Banica, F. In Vitro Study of Collagen Coating by Electrodeposition on Acrylic Bone Cement with Antimicrobial Potential. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostructures 2011, 6, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Marica, A.; Fritea, L.; Banica, F.; Sinescu, C.; Iovan, C.; Hulka, I.; Rusu, G.; Cavalu, S. Carbon Nanotubes for Improved Performances of Endodontic Sealer. Materials 2021, 14, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burak, K.; Hilmi, B.M. Evaluating Palatal Mucosal Thickness in Orthodontic Miniscrew Sites Using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merati, M.; Ghaffari, H.; Javid, F.; Ahrari, F. Success Rates of Single-Thread and Double-Thread Orthodontic Miniscrews in the Maxillary Arch. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, A.L.; Rustico, L.; Longo, M.; Oteri, G.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Nucera, R. Complications Reported with the Use of Orthodontic Miniscrews: A Systematic Review. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarul, M.; Lis, J.; Park, H.-S.; Rumin, K. Evidence-Based Selection of Orthodontic Miniscrews, Increasing Their Success Rate in the Mandibular Buccal Shelf. A Randomized, Prospective Clinical Trial. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.A.J.; Karl, P.A.M.; Mielke, J.M.-K.; Roser, C.J.; Lux, C.J.; Scheurer, M.; Keilig, L.; Bourauel, C.; Hodecker, L.D. Development and in Vitro Testing of an Orthodontic Miniscrew for Use in the Mandible. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2025, 86, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasagan, S.; Subramanian, A.K.; Nivethigaa, B. Assessment of Insertion Torque of Mini-Implant and Its Correlation with Primary Stability and Pain Levels in Orthodontic Patients. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Barrak, I.; Braunitzer, G.; Piffkó, J.; Segatto, E. Heat Generation and Temperature Control during Bone Drilling for Orthodontic Mini-Implants: An In Vitro Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, K.; Jedliński, M.; Mazur, M.; Janiszewska-Olszowska, J. Fracture and Deflection of Orthodontic Miniscrews—A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Park, H.-S. Long-Term Evaluation of Factors Affecting Removal Torque of Microimplants. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motoyoshi, M.; Hirabayashi, M.; Uemura, M.; Shimizu, N. Recommended Placement Torque When Tightening an Orthodontic Mini-Implant. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2006, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, T.; Nasu, M.; Murakami, K.; Yabuuchi, T.; Kamioka, H.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Quantitative Evaluation of Cortical Bone Thickness with Computed Tomographic Scanning for Orthodontic Implants. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 721.e7-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, E.Y.; Suzuki, B. Placement and Removal Torque Values of Orthodontic Miniscrew Implants. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2011, 139, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanec, C.L.; Panaite, T.; Zetu, I.N. Dimensions Define Stability: Insertion Torque of Orthodontic Mini-Implants: A Comparative In Vitro Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki, S.; Koyama, I.; Inoue, M.; Mishima, K.; Sugahara, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Factors Associated with the Stability of Titanium Screws Placed in the Posterior Region for Orthodontic Anchorage. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 124, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ding, X. Evaluation of Palatal Bone Thickness for Insertion of Orthodontic Mini-Implants in Adults and Adolescents. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 1468–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Guo, J.; Chen, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, L.; Pu, L.; Lai, W.; Long, H. Assessment of Available Sites for Palatal Orthodontic Mini-Implants through Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli, J.A.; Rocha, T.F.; Coelho, F.; de Oliveira Capote, T.S.; Saska, S.; Melo, M.A.; Pingueiro, J.M.S.; de Faveri, M.; Bueno-Silva, B. Metabolic Activity of Hydro-Carbon-Oxo-Borate on a Multispecies Subgingival Periodontal Biofilm: A Short Communication. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 5945–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Lin, J.-H.; Roberts, W.E. Success of Infrazygomatic Crest Bone Screws: Patient Age, Insertion Angle, Sinus Penetration, and Terminal Insertion Torque. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 161, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Santos, P.; Sousa-Santos, S.; Oliveira, A.C.; Queirós, C.; Mendes, J.; Aroso, C.; Mendes, J.M. Evaluation of Orthodontic Mini-Implants’ Stability Based on Insertion and Removal Torques: An Experimental Study. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, K.L.; Ali Mahmood, T.M. The Effect of Different Orthodontic Mini-Implant Brands and Geometry on Primary Stability (an in Vitro Study). Heliyon 2023, 9, e19858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, A.; Cyan, C. Effects of a Mini Implant’s Size and Site on Its Stability Using Resonance Frequency Analysis. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2021, 55, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Hsu, J.-T.; Yu, J.-H.; Huang, H.-L. Effects of an Augmented Reality Aided System on the Placement Precision of Orthodontic Miniscrews: A Pilot Study. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashil, A.M.; Sharma, A.; Jose, L.K.; Grover, S.; Kochar, A.S.; Varghese, S.T.; Sharma, T.; Ismail, P.M.S. A CBCT Assessment of Orthodontic Mini-Implant Placement. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S927–S929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riad Deglow, E.; Zubizarreta-Macho, Á.; González Menéndez, H.; Lorrio Castro, J.; Galparsoro Catalán, A.; Tzironi, G.; Lobo Galindo, A.B.; Alonso Ezpeleta, L.Ó.; Hernández Montero, S. Comparative Analysis of Two Navigation Techniques Based on Augmented Reality Technology for the Orthodontic Mini-Implants Placement. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Tripathi, T.; Rai, P.; Kanase, A. Evaluation of Orthodontic Mini-Implant Placement: A CBCT Study. Prog. Orthod. 2014, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, M.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Pu, L.; Lai, W.; Long, H. Optimal Sites and Angles for the Insertion of Orthodontic Mini-Implants at Infrazygomatic Crest: A Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT)-Based Study. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 8893–8902. [Google Scholar]

- Golshah, A.; Salahshour, M.; Nikkerdar, N. Interradicular Distance and Alveolar Bone Thickness for Miniscrew Insertion: A CBCT Study of Persian Adults with Different Sagittal Skeletal Patterns. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, I.; Milanovic, P.; Vasiljevic, M.; Milanovic, J.; Stevanovic, M.Z.; Jovicic, N.; Stepovic, M.; Ristic, V.; Selakovic, D.; Rosic, G.; et al. A Cone-Beam Computed Tomography-Based Assessment of Safe Zones for Orthodontic Mini-Implant Placement in the Lateral Maxilla: A Retrospective Morphometric Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay Elibol, F.K.; Oflaz, E.; Buğra, E.; Orhan, M.; Demir, T. Effect of Cortical Bone Thickness and Density on Pullout Strength of Mini-Implants: An Experimental Study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 157, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hafidh, N.N.; Al-Khatib, A.R.; Al-Hafidh, N.N. Clinical and Investigative Orthodontics Cortical Bone Thickness and Density: Inter-Relationship at Different Orthodontic Implant Positions Cortical Bone Thickness and Density: Inter-Relationship at Different Orthodontic Implant Positions. Clin. Investig. Orthod. 2022, 81, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Han, B.; Xu, T.; Chen, G. Vertical Changes in the Hard Tissues after Space Closure by Miniscrew Sliding Mechanics: A Three-Dimensional Modality Analysis. Head Face Med. 2023, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, H.S.; El-Beialy, A.R.; Palomo, J.M.; Mostafa, Y.A. Space Closure with Different Appointment Intervals: A Split-Mouth Randomized Controlled Trial. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2024, 15, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, L.; Kakoschke, T.K.; Keller, A.; Hötzel, L.; Baumert, U.; Otto, S.; Wichelhaus, A.; Sabbagh, H. Accuracy of Guided Insertion of Orthodontic Temporary Anchorage Devices Comparing Two Different 3D Printed Surgical Guide Designs: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, R.; Fabiane, M.; Zuccon, A.; Conte, D.; Ludovichetti, F.S. Maintaining Hygiene in Orthodontic Miniscrews: Patient Management and Protocols-A Literature Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicioni-Marques, F.; Pimentel, D.J.B.; Matsumoto, M.A.N.; Stuani, M.B.S.; Romano, F.L. Orthodontic Mini-Implants: Clinical and Peri-Implant Evaluation. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2022, 11, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilli, D.; Giansanti, M.; Bertoldo, S.; Cauli, I.; Cassetta, M. Dynamic Navigation System Accuracy in Orthodontic Miniscrew Insertion in the Palatine Vault: A Prospective Single- Arm Clinical Study. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2025, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Mitchell, B.; Sakamaki, T.; Hirai, Y.; Kim, D.-G.; Deguchi, T.; Suzuki, M.; Ueda, K.; Tanaka, E. Mechanical Stability of Orthodontic Miniscrew Depends on a Thread Shape. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraws Yalda, F.; Chawshli, O.F.; Al-Talabani, S.Z.; Ali, S.H.; Shihab, O.I. Evaluation of Palatal Thickness for the Placement of MARPE Device among a Cohort of Iraqi-Kurdish Population: A Retrospective CBCT Study. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 6741187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıklaçandır, S.; Kara, G.G.; İşler, Y. Investigation of Different Miniscrew Head Designs by Finite Element Analysis. Turkish J. Orthod. 2024, 37, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioana, T.R.; Boeru, F.G.; Antoniac, I.; Mitruț, I.; Staicu, I.E.; Rauten, A.M.; Uriciuc, W.A.; Manolea, H.O. Surface Analysis of Orthodontic Mini-Implants after Their Clinical Use. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaite, T.; Savin, C.; Olteanu, N.D.; Karvelas, N.; Romanec, C.; Vieriu, R.-M.; Balcos, C.; Baltatu, M.S.; Benchea, M.; Achitei, D.; et al. Heat Treatment’s Vital Role: Elevating Orthodontic Mini-Implants for Superior Performance and Longevity—Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, J.; Sarika, K.; Ajith, V.V.; Sapna Varma, N.K. Evaluation of Strain and Insertion Torque of Mini-Implants at 90° and 45° Angulations on a Bone Model Using Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2023, 14, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M.S.; Ulutas, P.A.; Ozenci, I.; Akcalı, A. Clinical and Radiographic Assessment of the Association between Orthodontic Mini-Screws and Periodontal Health. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, N.; Sabri, H.; Galindo-Fernandez, P.; Mirmohamadsadeghi, H.; Valian, N.K. Periodontal Status Following Orthodontic Mini-Screw Insertion: A Prospective Clinical Split-Mouth Study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, M.A.; Qasim, M.; Udeabor, S.E.; Hameed, M.S.; Mannakandath, M.L.; Alshahrani, I. Impact of Riboflavin Mediated Photodynamic Disinfection around Fixed Orthodontic System Infected with Oral Bacteria. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Łopaciński, M.; Los, A.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Riboflavin-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy in Periodontology: A Systematic Review of Applications and Outcomes. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami, L.; Shahabi, S.; Jazaeri, M.; Hadilou, M.; Fekrazad, R. Clinical Applications of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in Dentistry. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1020995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Du, Y.; Yang, K. Comparison of Pain Intensity and Impacts on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life between Orthodontic Patients Treated with Clear Aligners and Fixed Appliances: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, C.J.; Zubir, M.I.; Iskandar, M.H.; Ibrahim, M.S.M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Cross Sectional Study on Adolescents and Adults in Orthodontic Treatment in Kuantan, Pahang. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2025, 43, e20251156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouns, V.E.H.W.; de Waal, A.-L.M.L.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M.; Ongkosuwito, E.M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life before, during, and after Orthodontic-Orthognathic Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.W.; Jensen, E.D.; Sampson, W.; Dreyer, C. Torque Requirements and the Influence of Pilot Holes on Orthodontic Miniscrew Microdamage. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijarn, S.; Uezono, M.; Takakuda, K.; Ogasawara, T.; Techalertpaisarn, P.; Moriyama, K. Effect of Cutting Flute Geometry of Orthodontic Miniscrew on Cortical Bone Microdamage and Primary Stability Using a Human Bone Analog. Oral Sci. Int. 2025, 22, e1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinela, P.; Daniel-Nicolae, O.; Carina Ana-Maria, B.; Karvelas, N.; Savin, C.; Romanec, C.; Luchian, I.; Zetu, I.-N. The assessment of the orthodontic mini-implants risk of fracture—A literature review. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ummat, A.; Shetty, S.; Desai, A.; Nambiar, S.; Natarajan, S. Comparative Assessment of the Stability of Buccal Shelf Mini-Screws with and without Pre-Drilling- a Split-Mouth, Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, R.; Emori, T.; Ohama, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Horiguchi, Y.; Yoshida, N. The Impact of Drilling Guide Length of a Surgical Guide on Accuracy of Pre-Drilling for Miniscrew Insertion. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, V.; Perez, A.; Lombardi, T.; Felice, R.D. Heat Generated during Dental Implant Placement: A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-S.; Oh, J.-W.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.-W. Thermal Changes during Implant Site Preparation with a Digital Surgical Guide and Slot Design Drill: An Ex Vivo Study Using a Bovine Rib Model. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2022, 52, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Accuracy of Orthodontic Miniscrew Implantation Assisted by Dynamic Navigation Technology Combined With Cone Beam Computed Tomography. Cureus 2025, 17, e80882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, C.; McGregor, S.; Bearn, D.R. Temporary Anchorage Devices and the Forces and Effects on the Dentition and Surrounding Structures during Orthodontic Treatment: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.R.; Choi, J.Y.; Ahn, H.W.; Kim, S.H.; Nelson, G. Geometry of Anchoring Miniscrew in the Lateral Palate That Support a Tissue Bone Borne Maxillary Expander Affects Neighboring Root Damage. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, R.; Sukegawa, S.; Sukegawa, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Ono, S.; Fujimura, A.; Yamamoto, I.; Ibaragi, S.; Sasaki, A.; Furuki, Y. Subcutaneous Emphysema Related to Dental Treatment: A Case Series. Healthcare 2022, 10, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obara, T.; Nojima, T.; Nakatsuji, K.; Hongo, T.; Yumoto, T.; Nakao, A. Subcutaneous and Periorbital Emphysema Following a Dental Procedure. Cureus 2025, 17, e83089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seif, S.A.; AlNatheer, Y.; Al Bahis, L.; Ramalingam, S. Surgical Removal of an Orthodontic Mini-Screw Displaced Into the Lateral Pharyngeal Space: A Case Report and Review of Pertinent Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e52343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Anchorage Type | Typical Devices | Clinical Indications | Main Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoral (dental) | Consolidated teeth, ligatures, transpalatal arch | Mild space closure, alignment and leveling, limited canine retraction | Simple, low-cost, no external devices | Risk of anchorage loss, reciprocal forces | [24,25] |

| Dentomucosal | Tooth–mucosa-supported appliances (e.g., acrylic plates, buttons) | Mixed dentition, early transverse control, guidance of eruption | Noninvasive, reinforced soft-tissue support | Variable soft-tissue compliance, reduced force control | [26,27] |

| Extraoral | Headgear, facemask, chin cup | Growth modification, molar distalization, Class II/III correction in children | High skeletal effects, modulates growth | Compliance-dependent, esthetic concerns, potential safety risks | [28,29] |

| Skeletal (TADs) | Mini-implants, miniplates | En-masse retraction, molar intrusion, asymmetrical or 3D movements, noncompliant adults | Absolute anchorage, predictable, minimal cooperation | Technique-sensitive, anatomical variability, risk of soft-tissue complications | [30] |

| Design Parameter | Effect on Clinical Behavior | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Head profile | Auxiliary versatility; soft-tissue irritation risk | Low-profile, multipoint fixation |

| Neck height | Muco-gingival adaptation, hygiene, inflammation control | Match to mucosal thickness (1–3 mm) |

| Outer diameter | Insertion torque, fracture resistance, interradicular compatibility | 1.5–2.0 mm |

| Thread pitch and depth | Retention, insertion resistance, microfracture risk | Fine pitch with moderate depth |

| Thread shape | Load distribution, stress absorption, ease of removal | Conical in dense bone; cylindrical in soft bone |

| Tip design | Insertion ease, thermal trauma, bone microdamage | Self-drilling in soft/moderate bone; self-tapping in dense bone |

| Anatomical Site | Bone Density | Screw Diameter | Recommended Torque (N·cm) | Clinical Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior maxilla | Low–moderate | 1.4–1.6 mm | 5–7 | Pre-drilling often unnecessary; avoid overtightening to prevent early mobility | [64,65,66] |

| Posterior maxilla | Low density | 1.6–2.0 mm (conical) | 4–6 | Use conical or larger-diameter screws; high failure risk if over-torqued | [64,65,67] |

| Anterior mandible | Moderate–high | 1.4–1.6 mm | 8–10 | Good cortical support; monitor torque to avoid microfracture | [65,67] |

| Posterior mandible | High density/thick cortex | 1.6–2.0 mm | 10–12 | Self-tapping preferred; consider a pilot hole to reduce heat generation | [67,68,69] |

| Midpalatal suture | High density | 1.6–2.0 mm | 7–10 | Excellent primary stability; digital torque drivers recommended | [70,71] |

| Zygomatic crest | Very high density | ≥1.8 mm | 10–15 | Risk of overheating; CBCT evaluation essential for depth and trajectory planning | [61,65,72,73] |

| Domain/Variable | Clinical Impact | Practical Implication | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-miniscrew tissue indices (plaque, bleeding on probing, PD) | Strongly associated with mucositis and progressive instability risk, even in clinically asymptomatic but inflamed sites | Integrate periodontal index charting at each follow-up; manage inflammation as early risk rather than benign sign | [90,98] |

| Soft-tissue phenotype and collar adaptation | Inadequate adaptation correlates with radiographic bone changes and inflammation | Prioritize keratinized mucosa; measure mucosal thickness for collar-height matching | [98] |

| Hygiene feasibility and protocol type | Structured hygiene protocols reduce mucositis and risk of early mobility | Routine interdental brushing + alcohol-free chlorhexidine/essential oils rinse + reinforcement at each visit | [89] |

| Adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic strategies | Proven biofilm reduction on orthodontic surfaces in vitro and promising safety profile, but limited TADs-specific clinical data | Consider only in high-risk or maintenance-resistant cases; currently considered adjunctive rather than routine therapy | [100,101,102] |

| Screw dimension vs. comfort | Larger screws increase stability but also pain & inflammation | Match screw diameter to anchorage need, not default preference | [59] |

| OHRQoL impact (pain domain) | Early deterioration in OHRQoL mainly related to pain and ulceration | Discuss expected discomfort trajectory & provide supportive strategies | [103,104,105] |

| Parameter | Self-Drilling | Pre-Drilling | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | No pilot hole; sharp-cutting tip | Pilot hole (0.2–0.3 mm smaller) | [52,60,106,107] |

| Indicated Bone Type | Moderate to soft (maxilla) | Dense (mandibular posterior) | [59,106,108,109] |

| Insertion Torque | Higher; may need torque control | Lower; smoother path | [6,106,110] |

| Heat Generation Risk | Low | High if >1000 rpm or poor irrigation | [62,111,112] |

| Primary Stability | Higher | Slightly lower | [42,109] |

| Clinical Advantage | Faster, less instrumentation | Safer in dense bone | [52,62,106] |

| Complication Type | Examples | Preventive Measures | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative | Root contact, excessive torque, fracture | CBCT planning, optimized insertion angle, torque-limited driver | [11,60,68,79,113] |

| Postoperative | Mucositis, early mobility, inflammation | Hygiene, correct collar height, force control (<200 g) | [47,56,89,98,114] |

| Rare/Severe | Sinus perforation, emphysema, neurovascular injury | Avoid deep insertions, air-driven tools, monitor anatomical landmarks | [115,116,117,118] |

| Recommendation | Justification | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Use self-drilling in maxilla | Less dense bone, faster insertion | [59,62,109] |

| Use pre-drilling in dense mandible | Prevent overheating and torque overload | [6,60,68] |

| Maintain 5–10 N·cm torque | Ensures stability without damage | [47,60] |

| Apply force ≤ 200 g post-insertion | Avoids overload during healing | [47,114] |

| Use CBCT for planning | Increases safety and predictability | [79,88,91] |

| Enforce hygiene protocols | Prevents mucositis and late mobility | [56,89,98] |

| Clinical Question/Decision | Predominant Evidence Types (OCEBM Levels) | Effect Direction and Consistency | Clinical Applicability | Overall Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended insertion angle (perpendicular vs. 30–45°) | Clinical survival studies, CBCT geometric mapping, FEA | Perpendicular insertion reduces peak stress in dense cortical bone; 30–45° angulation improves root safety in narrow interradicular sites | Site-specific angle selection | Low–moderate |

| Optimal insertion torque range (5–10 N·cm for 1.5–1.6 mm screws) | Clinical torque–removal studies, CBCT-derived cortical thickness data, in vitro mechanical tests | Consistent association between moderate torque and higher primary stability with reduced microdamage risk | Routine torque selection for most alveolar sites | Moderate |

| Hygiene protocols and inflammation control | Clinical studies, periodontal assessments, narrative reviews, in vitro biofilm work | Consistent reduction of mucositis with structured hygiene | Universal applicability; intensified for high-risk patients | |

| Self-drilling vs. pre-drilling (maxilla vs. dense mandible) | RCTs, clinical comparative studies, thermal/mechanical in vitro experiments | Convergent evidence: self-drilling suitable for moderate-density maxilla; pre-drilling safer in dense mandibular cortex | Widely applicable for routine placement | Moderate–high |

| Collar height and soft-tissue management | Prospective clinical studies, CBCT soft-tissue thickness assessments, periodontal evaluations | Consistent association between matched collar height and lower inflammation/mobility | Routine device selection; critical in non-keratinized mucosa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bungau, T.C.; Marin, R.C.; Țenț, A.; Ciavoi, G. Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Narrative Review of Biomechanical Foundations, Clinical Protocols, and Technological Advances. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413035

Bungau TC, Marin RC, Țenț A, Ciavoi G. Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Narrative Review of Biomechanical Foundations, Clinical Protocols, and Technological Advances. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413035

Chicago/Turabian StyleBungau, Teodora Consuela, Ruxandra Cristina Marin, Adriana Țenț, and Gabriela Ciavoi. 2025. "Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Narrative Review of Biomechanical Foundations, Clinical Protocols, and Technological Advances" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413035

APA StyleBungau, T. C., Marin, R. C., Țenț, A., & Ciavoi, G. (2025). Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics: A Narrative Review of Biomechanical Foundations, Clinical Protocols, and Technological Advances. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413035