Abstract

This paper presents OcclusionTrack (OCCTrack), a robust multi-object tracker designed to address occlusion challenges in dense scenes. Occlusion remains a critical issue in multi-object tracking; despite significant advancements in current tracking methods, dense scenes and frequent occlusions continue to pose formidable challenges for existing tracking-by-detection trackers. Therefore, four key improvements are integrated into a tracking-by-detection paradigm: (1) a confidence-based Kalman filter (CBKF) that dynamically adapts measurement noise to handle partial occlusions; (2) camera motion compensation (CMC) for inter-frame alignment to stabilize predictions; (3) a depth–cascade-matching (DCM) algorithm that uses relative depth to resolve association ambiguities among overlapping objects; and (4) a CMC-detection-based trajectory Re-activate method to recover and correct tracks after complete occlusion. Despite relying solely on IoU matching, OCCTrack achieves highly competitive performance on MOT17 (HOTA 64.9, MOTA 80.9, IDF1 79.7), MOT20 (HOTA 63.2, MOTA 76.9, IDF1 77.5), and DanceTrack (HOTA 57.5, MOTA 91.4, IDF1 58.4). The primary contribution of this work lies in the cohesive integration of these modules into a unified, real-time pipeline that systematically mitigates both partial and complete occlusion effects, offering a practical and reproducible framework for complex real-world tracking scenarios.

1. Introduction

The multi-object tracking (MOT) task aims to obtain the spatial–temporal trajectories of multiple objects in videos. The tracking targets in multi-object tracking encompass various types: pedestrians, vehicles, animals, and more. Currently, there are three mainstream paradigms for multi-object tracking: (1) tracking-by-detection (TBD); (2) joint detection and tracking (JDT); and (3) transformer-based tracking. Through experiments, it has been demonstrated that TBD is currently the strongest paradigm in MOT [1,2,3].

TBD includes two main stages: detecting and tracking. The working process of TBD is to input video frames into the detector to generate detection bounding boxes, then run the tracking algorithm to obtain the final tracking results. The tracking stage has two main parts. (1) The motion model, which is used for predicting the states of trajectories at the current frame to generate bounding boxes. Most TBD paradigms employ the Kalman filter [4] as the motion model. (2) Associating new detections with the current set of tracks. The associating task is mainly to compute pairwise costs between trajectories and detections, then solve the cost matrix using the Hungarian algorithm to obtain the final matching results. There are two mainstream methods for cost calculation. (a) Localizing the objects through the intersection-over-union (IoU) between the predicted bounding boxes and the detection bounding boxes [1,3]. (b) The appearance model [2,5,6], which compute the similarity between their appearance features. Both methods are quantified into distances and used for solving the association task as a global assignment problem.

While simple and effective, mainstream TBD methods like SORT [1], DeepSORT [2], and ByteTrack [3] exhibit significant limitations in dense and occluded scenes, primarily stemming from their core components:

- (1)

- Vulnerability to Partial Occlusions: Occlusions pose a major challenge. Partial occlusions can degrade detection quality, but the KF’s update stage typically uses a uniform of measurement noise, failing to account for this variability.

- (2)

- Sensitivity to Camera Motion: The performance of IoU-based tracking is highly dependent on the accuracy of the Kalman filter’s predicted boxes. Camera motion can cause coordinate shifts between frames, leading to prediction offsets and subsequent association failures.

- (3)

- Ineffective Association under Occlusion: During the association stage, occlusion poses significant challenges to matching methods. Because occlusion arises from overlapping targets, the positions and sizes of the bounding boxes for these overlapping targets become extremely close, and conventional matching algorithms fail to deliver satisfactory performance.

- (4)

- Vulnerability to Complete Occlusions: Complete occlusions cause tracks to be lost, meaning that the detector cannot detect that trajectory in the image, during which the KF continues to predict without correction, accumulating significant error and hindering the target’s tracking performance after rematching.

To address these interconnected challenges, we propose a comprehensive framework that enhances the TBD pipeline at multiple stages:

- We introduce a confidence-based Kalman filter (CBKF) that dynamically adjusts the measurement noise based on detection confidence, improving robustness to partial occlusions.

- We incorporate camera motion compensation (CMC) [5] to align frames, thereby rectifying the prediction offsets in the KF and boosting the reliability of IoU-based association.

- We integrate depth–cascade-matching (DCM) [7] into the association phase. By leveraging relative depth information to partition targets and perform matching within the same depth level, DCM effectively resolves ambiguities caused by inter-object occlusions.

- For tracks recovering from complete occlusion, we employ the CMC-detection-based Re-activate method to correct accumulated errors in the track state and KF parameters, which ensures that the target can be successfully associated in subsequent frames.

2. Related Works

The key characteristics and limitations of different classic tracking methods are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The key characteristics and limitations of different tracking methods.

Motion model. In recent years, motion models for multi-object tracking TBD paradigms have primarily fallen into two categories: (1) the Kalman filter [4], based on constant-velocity assumptions [1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9]; and (2) motion prediction grounded in deep learning [10,11]. The traditional Kalman filter offers fast computation and performs well in pedestrian tracking, while deep learning-based motion prediction excels at handling complex non-linear motions. Concurrently, to address camera motion in complex scenes, numerous researchers employ image registration for frame alignment—specifically through methods like maximizing the enhanced correlation coefficient (ECC) or feature-matching techniques such as ORB.

Re-identification. The appearance-based re-identification (Re-ID) technique has also garnered significant attention [2,6,8]. By training an appearance feature extraction network to capture the appearance features of objects within detection bounding boxes, the system calculates the similarities between extracted features and historical appearance features from trajectories. These similarities are then integrated into a cost matrix to achieve superior association performance. However, in scenarios with severe occlusions, the detector performance degrades, causing detection bounding box shifts that make it difficult for the appearance feature extraction network to accurately capture features. Additionally, since the detector and appearance feature extraction network are two separate networks, the computational cost is high. Therefore, researchers have proposed the joint-detection-embedding (JDE) paradigm, which integrates the detector and appearance feature extraction network to reduce computational cost.

Association. Data association is a crucial component of multi-object tracking, and effective data association significantly enhances tracker performance. DeepSORT [2] integrates appearance information into the cost matrix, employing cascaded matching that prioritizes newer trajectories to prevent occluded targets from being incorrectly associated with new detections. ByteTrack [3] divides the detection set into high-score detections and low-score detections based on confidence scores and performs matching from highest to lowest. SparseTrack [7] designed the DCM algorithm, which divides both the trajectory set and the detection set into an equal number of subsets based on depth information. Matching is then performed sequentially. BoTSORT [5] uses the exponential moving average to dynamically update visual characteristics. Most algorithms using appearance features set a hyperparameter to adjust the weighting between motion features and appearance features. Most tracking-by-detection trackers use the Hungarian algorithm to solve the cost matrix to obtain the final matching results.

3. Methods

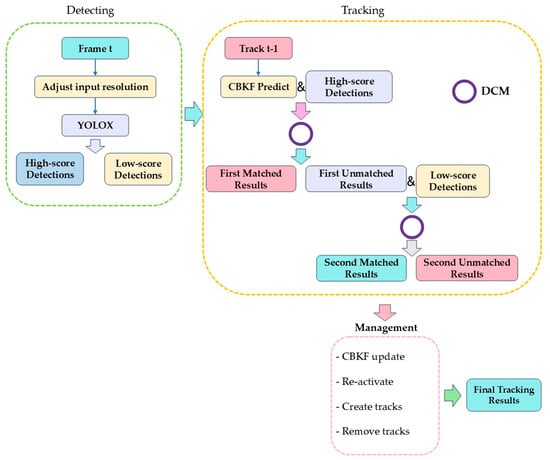

We present four improvements in this paper, and we use ByteTrack [3] as the baseline model. Our tracker only uses IoU matching for data association. The framework of our tracker is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overall framework of our tracker. CMC is included in the CBKF prediction in this figure.

3.1. Confidence-Based Kalman Filter

In recent years, there have been two mainstream motion models in tracking-by-detection: (1) the Kalman filter [4]; and (2) the deep learning motion model. The core task of the Kalman filter is state estimation. Given past state information of a target, it predicts the target’s potential location at the next frame based on a constant-velocity kinematic model. This predicted state is then refined using the current detection bounding box to produce the final result. Deep learning models are primarily data-driven, relying on large training datasets and appropriate training methods. They often demonstrate strong performance in scenarios with highly complex motion patterns. However, in multi-pedestrian tracking scenarios, target motion patterns tend to be relatively simple, and the frame intervals are short, and pedestrian movements over short durations generally align well with the Kalman filter’s prior assumptions about target motion patterns. Consequently, the Kalman filter can demonstrate sufficiently robust performance in such scenarios. Deep learning models, due to their data-driven nature, require large amounts of high-quality training samples for pedestrian tracking scenarios and carry the risk of overfitting. Furthermore, compared to the Kalman filter, deep learning models have a vast number of parameters, increasing computational costs. Therefore, we selected the Kalman filter as the motion model.

The Kalman filter [4] is employed in multi-object tracking for motion state prediction and information fusion after matching. In recent years, the Kalman filter state vector has been defined as an eight-dimensional vector . However, experiments of BoTSORT [5] demonstrated that directly predicting the bounding box width yields better results than predicting the aspect ratio. Therefore, we adopt the eight-dimensional state vector from BoTSORT as detailed in Equation (1). The measurement vector is defined in Equation (2).

Here, and denote the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the center point of the bounding box, while and represent the width and height of the bounding box.

The Kalman filter performs two functions: prediction in Equations (3) and (4) and update in Equations (5)–(7). and are in Equations (8) and (9). In multi-object tracking, prediction generates the predicted state of trajectories, while update combines the detection boxes and predicted boxes to produce the final tracking results.

However, through experiments and some studies, we have discovered that there is a pressing issue that needs to be addressed for the traditional Kalman filter. In dense scenes, occlusions frequently occur, posing significant challenges to detector performance. Severe occlusions will degrade detection results. However, in such cases, the traditional Kalman filter still calculates measurement noise using the same method regardless of detection quality, causing trackers to experience substantial performance degradation when confronting occlusion challenges. Therefore, based on detection confidence, an intuitive metric for quantifying the quality of detection results, we designed a non-linearly varying coefficient to scale measurement noise in Equation (10).

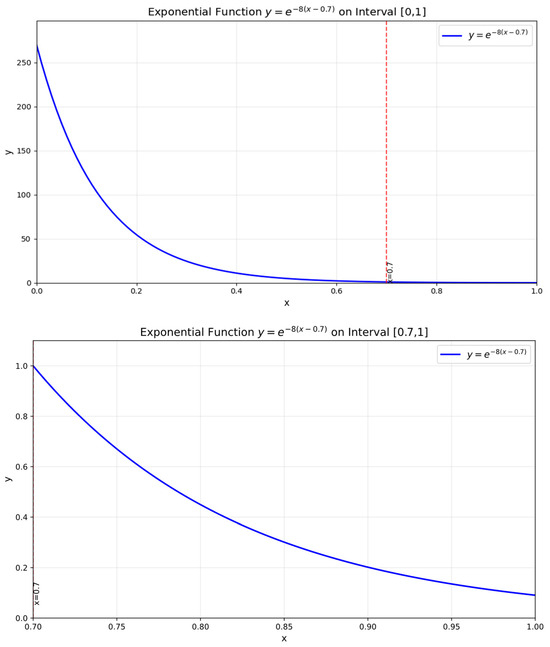

Among these, is an adjustable hyperparameter that controls the rate of change in the scaling factor. is the confidence threshold, representing the boundary line determining whether a detection result is considered reliable. According to the properties of exponential functions, within the interval (, 1], as the confidence level increases, the function curve flattens out, and the scaling factor ultimately approaches zero. Within the interval [0, ], as the confidence level decreases, the function curve becomes steeper, and the scaling factor tends toward a very large value. The curve is shown in Figure 2. This indicates that when confidence is high, the tracker fully trusts the detection result, while when confidence is low, it places greater trust in the predicted state. The improved Kalman filter update functions are in Equations (11)–(13).

Figure 2.

The figure above shows the confidence-based scaling factor function curve in the range from 0 to 1. The figure below shows the confidence-based scaling factor function curve in the range from 0.7 to 1. The horizontal axis represents the confidence score.

Furthermore, to evaluate the performance of different types of scaling factors, we conduct a comparative experiment on the MOT17 validation set. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The impact of different scale factors on MOT17.

3.2. Camera Motion Compensation

Tracking-by-detection trackers that rely solely on IoU distance place significant emphasis on the quality of prediction boxes. However, in complex scenarios where the camera position is not fixed, camera motion causes shifts in the reference coordinate system between consecutive frames. In such cases, the Kalman filter [4] continues to output predicted states based on the previous frame’s coordinate system, resulting in prediction boxes exhibiting substantial bias. Therefore, in recent years, some trackers have begun to apply camera motion compensation to achieve inter-frame coordinate system registration [5,6]. We introduced the global motion compensation (GMC) technique [5] from OpenCV [12]. This registration method is suitable for revealing the background motion of adjacent frames. First, image key-points are extracted [13], followed by feature point tracking using sparse optical flow. Then, based on the corresponding feature points, a system of equations is constructed. The RANSAC algorithm [14] is used to solve this system of equations and obtain the affine matrix in Equation (14).

represents the rotation and scaling components within the affine matrix, while T represents the translation component within the affine matrix. Since the predicted state x is an eight-dimensional vector, each dimension requires transformation. Therefore, the and that satisfy the tracking requirements are as follows in Equation (15). Then, apply and to transform the predicted state and the predicted covariance matrix in Equations (16) and (17).

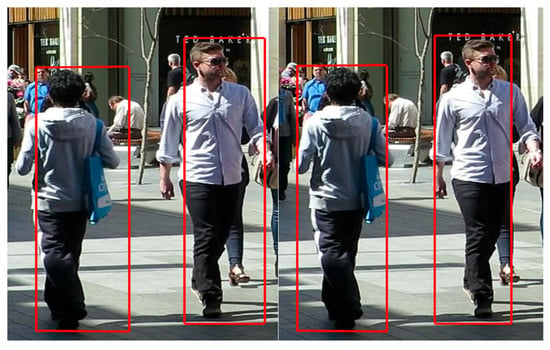

where represents the predicted state before transformation. represents the predicted covariance matrix before transformation. represents the predicted state after transformation. represents the predicted state after transformation. After CMC processing, the predicted state is based on the current frame coordinate system. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The left image is the predicted state before CMC. The right image is the predicted state after CMC.

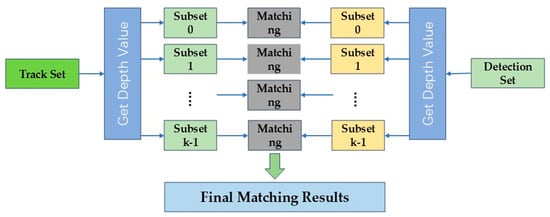

3.3. Depth–Cascade-Matching

Occlusion refers to the overlapping of multiple objects. In dense scenes, due to frequent occlusions, multiple targets are highly prone to overlapping. In such cases, both their prediction boxes and detection boxes become extremely close, making conventional matching methods susceptible to causing ID switches. Therefore, we introduced the depth–cascade-matching (DCM) algorithm [7], shown in Figure 4, to address occlusion issues during the matching phase. The DCM algorithm consists of two main stages: calculating the pseudo-depth value and the cascade-matching bases on the obtained pseudo-depth value.

Figure 4.

The framework of DCM is shown in this figure.

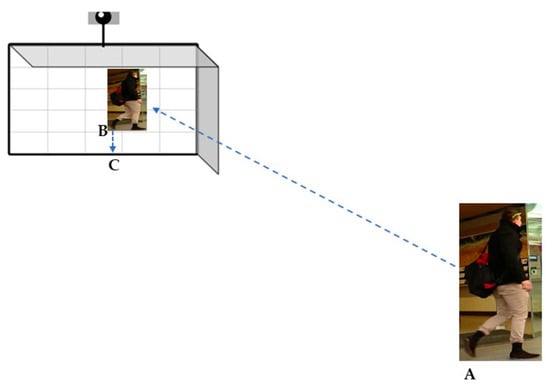

For calculating the pseudo-depth value, we first obtain the connection point between the target and the ground in three-dimensional space. This connection point is then projected onto the camera plane, with the projection point denoted as .

Secondly, a perpendicular line is drawn from point to the bottom edge of the image, with the intersection point denoted as . The Euclidean distance between and is calculated to serve as the pseudo-depth value. The pseudo-depth value, in a certain sense, represents the occlusion relationships between objects. The computational process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The illustration of depth value.

After obtaining the pseudo-depth value, the tracker performs cascade matching. For the detection set, we divided the depth values of detections into k intervals between the maximum depth value and the minimum depth value using a linear method. Based on the depth values, the detection results are assigned to corresponding intervals, forming k subsets . k signifies the highest depth level. Then use the same operation to split the track set into k subsets

Trajectories and detections at the same depth level undergo matching. The matching process proceeds from lower to higher depth levels. Our tracker only uses IoU distance to match, solving the cost matrix through the Hungarian algorithm. Trajectories and detections that remain unmatched at the current level are passed to the next level for matching after the data association of each depth level.

3.4. CMC-Detection-Based Re-Activate Method

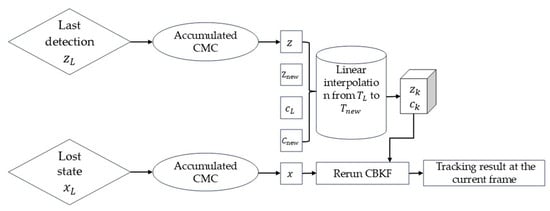

Severe occlusions can cause long-term target lost. During the period of the long-term target loss, both the Kalman filter and deep learning models predict motion state based on the target’s historical trajectory. However, according to the analysis of OC-SORT [9], this prediction method will lead to substantial error accumulation in the trajectory state and the Kalman filter’s parameter during the lost period, meaning that even if the target is rematched, it remains at risk of being lost again in subsequent phases. The accumulation of error mainly stems from the absence of detection in the lost period. Therefore, we propose a Re-activate method based on CMC and detection for generating virtual detections to address the issue of error accumulation. This re-activate method is applied after the trajectory has been rematched.

Firstly, our tracker records the information of the last matched detection before becoming lost, including bounding boxes , detection confidence , and its frame . When a trajectory is marked as lost, our tracker records its trajectory state . Meanwhile, the tracker maintains a CMC list whose length matches the maximum age of the trace to contain the CMC affine matrix at the beginning of tracking. When the trajectory is rematched, the newly matched detection bounding box, confidence score, and frame are denoted as , , and separately.

Secondly, the tracker performs the Re-activate operation by applying the accumulated CMC from to to in Equation (18). Due to and being recorded at different frames, the tracker applies the accumulated CMC from to to in Equation (19). For generating a series of virtual detection bounding boxes , the tracker uses linear interpolation between the newly matched detection bounding box and the last matched detection bounding box after CMC in Equation (20), shown in Figure 6. Then the tracker generates a series of virtual detection confidence scores using linear interpolation between the newly matched detection confidence and the last matched detection confidence in Equation (21). After completing the aforementioned data preparation tasks, the tracker backtracks the trajectory state to the recorded state after CMC, reruns CBKF for the lost period from to and obtains the final trajectory state for the current frame. The operational process of Re-activate is shown in Figure 7.

where represents the trajectory state after cumulative CMC transformation, denotes the last detection box before becoming lost after cumulative CMC transformation, and indicates the frame number corresponding to the generated virtual detection.

Figure 6.

The left image shows the position of the pedestrian in the last frame before becoming lost. The right image shows the position of the pedestrian in the re-associated frame. The dashed rectangles represent the generated virtual detections.

Figure 7.

The operational process of Re-activate.

It is worth noting that, initially, we only intended to use detection bounding boxes and the same confidence score to generate virtual detections. However, experiments reveal that this approach performs poorly in certain scenarios. Therefore, we introduce CMC to help the tracker generate more robust virtual detections; furthermore, linear interpolation is also applied to the confidence score to generate a more reliable confidence level. Additionally, we evaluate both approaches on the MOT17-14 video sequence. The results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 8.

Table 3.

The comparison between the two approaches on MOT17-14.

Figure 8.

The left image was obtained using CMC-detection-based Re-activate. The right image was obtained using the method of detection bounding boxes and the same confidence score.

From Table 2 and Figure 8, we can conclude that the improved Re-activate method indeed demonstrates superior performance in certain scenarios. In the MOT17-14 video sequence scenarios, the camera is in constant motion. Under such conditions, if trackers do not use CMC to calibrate the last detection and coordinate systems, this would introduce additional errors into the target trajectory. Additionally, when we perform linear interpolation between two detection results with different confidence levels to generate virtual detection bounding boxes, accurately evaluating these generated boxes becomes challenging. Therefore, we opt to linearly interpolate the confidence scores to generate virtual confidence scores. These virtual confidence scores gradually decrease from the higher confidence side toward the lower confidence side, indicating that the tracker places greater trust in virtual detection boxes closer to the higher confidence side.

3.5. Tracking Pipeline

To more clearly demonstrate the pipeline of OcclusionTrack and enhance reproducibility, we present Algorithm 1, which integrates ByteTrack with our four improvements.

Step 1: Use the YOLOX detector to detect bounding boxes and confidence scores from the current frame image. Classify these detections into high-score and low-score detections based on confidence scores.

Step 2: Calculate the CMC parameter using the current frame image and the previous frame image. Apply Kalman filtering to predict the trajectory state for the current frame, then correct it using CMC.

Step 3: Perform the first association: match the predicted trajectory state with high-scoring detections using DCM to obtain association results.

Step 4: Perform the second association: match the unmatched trajectory from the first association with low-score detections using DCM to obtain association results.

Step 5: Merge the association results from the first two steps.

Step 6: Update the matched results: if the trajectory state is activated, perform CBKF update; if the trajectory state is lost, perform Re-activate.

Step 7: Process unmatched tracks by incrementing their lost frame count by one. If the lost frame count exceeds the max age, remove the track. If within the max age, set the track state to lost.

Step 8: Initialize unmatched detections as new tracks.

Step 9: Output the current frame tracking results.

| Algorithm 1: Proposed OcclusionTrack Pipeline for Frame t. |

| Input: Current frame I_t, Previous tracks T_{t-1}, Previous image I_{t-1} Output: Updated tracks T_t # Step 1: Object Detection and Classification 1: D_all = detector(I_t) // Get all detections {bbox, score} 2: D_high = {d ∈ D_all | d.score ≥ τ_high} // High-score detections 3: D_low = {d ∈ D_all | d.score < τ_high ∧ d.score ≥ τ_low} // Low-score detections # Step 2: Kalman Filter Prediction with CMC 4: H = estimate(I_{t-1}, I_t) // Camera motion compensation 5: for each track τ in T_{t-1} do 6: if τ.state ∈ {“active”, “lost”} then 7: τ.pred_box = KalmanPredict(τ) // Standard prediction 8: τ.pred_box = compensate(H, τ.pred_box) // Apply CMC 9: end if 10: end for # Step 3: First Association (High-score detections) 11: T_candidates = {τ ∈ T_{t-1} | τ.state ∈ {“active”, “lost”}} // All tracks 12: matches_high, unmatched_tracks_1, unmatched_dets_high = DCM_Association(D_high, T_candidates) # Step 4: Second Association (Low-score detections) 13: matches_low, unmatched_tracks_2, unmatched_dets_low = DCM_Association(D_low, unmatched_tracks_1) # Step 5: Merge Matching Results 14: all_matches = matches_high ∪ matches_low 15: unmatched_tracks = unmatched_tracks_2 16: unmatched_dets = unmatched_dets_high ∪ unmatched_dets_low # Step 6: Track Update and Management 17: for each match (τ, d) in all_matches do 18: if τ.state == “lost” then 19: τ = Re_activate(τ, d, CMC) // Re-activate for lost tracks 20: end if 21: 22: # CBKF update with non-linear measurement noise 23: R = compute_measurement_noise(d.score, R) // Measurement noise based on confidence 24: KalmanUpdate(τ, d.bbox, R) 25: τ.state = “active” 26: τ.lost_count = 0 // Reset lost counter 27: end for # Step 7: Handle Unmatched Tracks 28: for each track τ in unmatched_tracks do 29: τ.lost_count += 1 30: if τ.lost_count > max_age then 31: τ.state = “removed” // Delete track 32: else 33: τ.state = “lost” 34: end if 35: end for # Step 8: Initialize New Tracks 36: for each detection d in unmatched_dets do 37: if d.score ≥ τ_init then 38: create_new_track(d) 39: end if 40: end for # Step 9: Output Results 41: T_t = {τ ∈ T_{t-1} ∪ new_tracks | τ.state ≠ “removed”} 42: return T_t |

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate the performance of our tracker on the MOT17 [15], MOT20 [16], and DanceTrack [17] datasets. Tracking is performed on the test sets of MOT17 and MOT20, and tracking results are submitted to MOTchallenge to obtain tracking metrics. Based on ByteTrack [3], we split the MOT17 and MOT20 training sets in half to form validation sets and evaluate the performance of each component on the validation sets.

MOT17. The MOT17 [15] dataset is one of the most influential and widely used benchmark datasets in the field of multi-object tracking (MOT). It aims to provide a unified, rigorous, and challenging platform for evaluating and comparing multi-object tracking algorithms. The MOT17 dataset comprises 14 video sequences primarily featuring pedestrian tracking scenarios across both indoor and outdoor environments. It encompasses multiple key challenges: (1) occlusion; (2) lighting variations; (3) camera motion; (4) scale changes; and (5) dense crowds.

MOT20. The MOT20 [16] dataset is a benchmark dataset proposed in the field of multi-object tracking (MOT) to address scenarios involving extremely dense crowds. The core objective of MOT20 is to evaluate the robustness and accuracy of tracking algorithms in environments characterized by exceptionally high crowd density and severe occlusions. MOT20 comprises eight video sequences primarily captured at large public gatherings, train stations, and plazas. The key challenges of MOT20 are extremely high target density and severe and persistent occlusions.

DanceTrack. The DanceTrack [17] dataset exhibits the following characteristics: tracking targets share similar visual features, their motion patterns are highly complex, and occlusion occurs frequently. Dancetrack comprises a total of 100 video sequences, including 40 training sequences, 20 validation sequences, and 40 test sequences. Furthermore, similar to the MOT series datasets, test set metrics require uploading results to the official website to obtain.

4.2. Metrics

We employ the general CLEAR metrics [18], HOTA [19], MOTA, IDF1 [20], ID Switch, FP, and FN to evaluate the performance of our tracker. MOTA emphasizes detector performance. ID Switch represents the number of target ID switches, reflecting the identity retention capability of a tracker. Additionally, IDF1 emphasizes association performance. HOTA serves as a comprehensive metric to evaluate the overall effectiveness of detection and association.

4.3. Implementation Details

During the confidence-based Kalman filter update and Re-activate phases, we set different values based on distinct datasets. For MOT17, the default value for is 8. For MOT20, the default value is set to 12. For DanceTrack, we set the default value of at 12. Additionally, the confidence threshold is set to 0.7 in MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack. During the DCM association stage, for MOT17, the default depth levels are set to 3, for MOT20, the default depth levels are set to 8, and for DanceTrack, the default depth levels are set to 12. The high-score and low-score detection threshold is set to 0.6 and 0.1 by default. The down scale of CMC is set to 4 by default. The method of CMC is the sparse optical flow method. All our tracking results rely solely on IoU distance.

In the comparison experiments, to ensure fair comparison, we employed the pre-trained YOLOX detector from ByteTrack [3], utilizing the same weights and NMS threshold as ByteTrack [3]. Additionally, all experiments are performed on the NVIDIA GeForce RTX3060 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.4. Comparison on MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack

We evaluate our tracker on the MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack test sets in comparison with other state-of-the-art trackers. The best results are shown in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 4.

The comparison of our tracker with other state-of-the-art methods under the “private detector” protocol on the MOT17 test set.

Table 5.

The comparison of our tracker with other state-of-the-art methods under the “private detector” protocol on the MOT20 test set.

Table 6.

The comparison of our tracker with other state-of-the-art methods under the “private detector” protocol on the DanceTrack test set.

MOT17. Through the comparison with other state-of-the-art methods, our tracker has demonstrated strong performance on the MOT17 test set. Compared to the baseline ByteTrack [3] with the same pre-trained detector YOLOX, our tracker achieves gains of +1.8 HOTA, +0.6 MOTA, and +2.4 IDF1, and ID Switch reduced to almost half that of ByteTrack’s.

MOT20. Through the comparison with other state-of-the-art methods, our tracker has demonstrated that it still maintains robust tracking performance in scenes with severe occlusion on the MOT20 test set. Compared to the baseline (ByteTrack) with the same pre-trained detector YOLOX, our tracker achieves gains of +1.9 HOTA and +2.3 IDF1, and ID switch has been reduced by twenty-five percent.

DanceTrack. Through the comparison with other state-of-the-art methods, our tracker has demonstrated strong performance on the DanceTrack test set. Compared to the baseline with the pre-trained YOLOX detector from OC-SORT, our tracker achieves gains of +9.8 HOTA, +1.8 MOTA, and +4.5 IDF1.

4.5. Ablation Studies of Different Components

We evaluate our tracker on the validation sets of MOT17 and MOT20 to observe the impact of different components on tracking performance. The results are shown in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Ablation studies on the MOT17 validation set.

Table 8.

Ablation studies on the MOT20 validation set.

MOT17. On the MOT17 validation set, we set to 8 and to 0.7. The depth level is set to 3. We use sparse optical flow as the CMC method. We use the pre-trained detector YOLOX from ByteTrack [3] as the detector. Through the experiments, CMC achieves primary gains of +0.9 IDF1, CBKF achieves gains of +0.3 IDF1, and Re-activate achieves gains of +0.1 MOTA.

MOT20. On the MOT20 validation set, we set to 15 and to 0.7. The depth level is set to 8. We use sparse optical flow as the CMC method. We use the pre-trained detector YOLOX from SparseTrack [7] as the detector. Through the experiments, CBKF and DCM both achieve gains of +0.3 IDF1 and Re-activate achieves gains of +0.1 HOTA.

4.6. The Impact of Different Values

We evaluate our tracker on the MOT17 validation set to obtain the impact of different values on tracking performance. The results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

The performance of the OcclusionTrack when using different values.

We set the value to 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. As values increase, the tracking performance gradually improves. When values reach 6 and 8, the tracking performance achieves the best scores. When we continue to increase to 10, tracking performance begins to decline. This indicates that a larger value facilitates Kalman filter update. However, when it becomes excessively large, performance actually deteriorates. We think that an overly large value may cause measurement noise to fluctuate too rapidly, thereby interfering with detection results with confidence between 0.4 and 0.6.

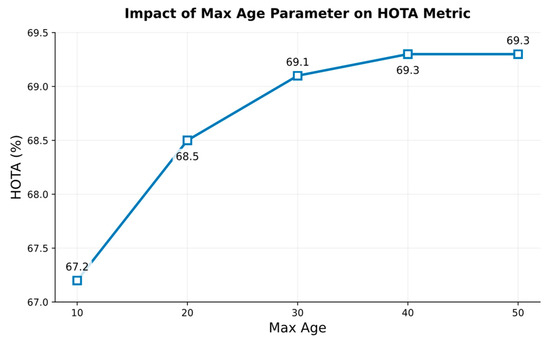

4.7. The Impact of the Max Age

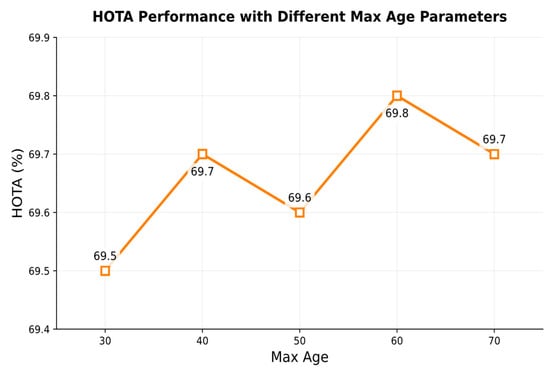

Severe occlusions can cause the long-term lost of trajectories. The max age represents the maximum number of frames a trajectory remains lost for before being removed. Both excessively low and excessively high max age values can degrade tracking performance. When the max age is set too low, even if a trajectory is rematched in subsequent frames, it cannot recover its original ID because it has already been removed by the tracker. Instead, it is assigned a new ID. When the max age is set too high, the target may have disappeared from the frame, yet the tracker continues to predict its state. This not only increases computational loads but also risks erroneous matches. Therefore, we evaluate the tracking performance of different max age settings on the MOT17 and MOT20 validation sets to observe the impact of the max age on tracking performance. The results are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

The impact of different max age settings on the MOT17 validation set.

Figure 10.

The impact of different max age settings on the MOT20 validation set.

4.8. The Impact of Different Detectors

Tracking-by-detection (TBD) trackers rely heavily on the detection quality of the detector. It can be said that TBD’s current powerful capabilities are inseparable from the continuous advancement of detectors. Therefore, we evaluate our tracker’s performance with different detectors to obtain the impact of the detector on tracking performance. The results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

The performance of the OcclusionTrack when using different detectors.

We can observe that detectors with enhanced performance significantly improve the tracking capabilities of trackers. This indicates that we can enhance tracking performance by designing detectors with superior capabilities.

To observe the generalization capabilities of each module when using different detectors, we replaced the detector with a more powerful one and conducted ablation experiments on each module. The results are shown in Table 11. Through the above two experiments, we observed that OcclusionTrack is highly sensitive to detector performance; poor-quality detectors significantly limit the tracker’s capabilities. This situation may be due to the fact that each module within OcclusionTrack relies heavily on the data provided by the detector.

Table 11.

Performance analysis of each module when using a better detector on the MOT17 validation set.

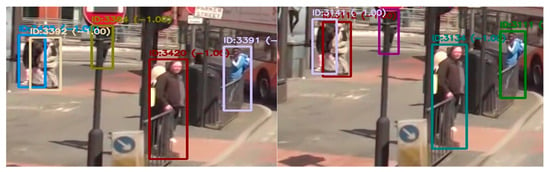

4.9. Visualization

To better evaluate the tracking performance of our tracker and observe the specific performance of our tracker, we conduct visualization experiments on the MOT20 and MOT17 test sets. The visualization results are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

These two images are taken from two consecutive frames within the same MOT20 video sequence.

Figure 12.

These two images are taken from two consecutive frames within the same MOT17 video sequence.

This MOT20 video sequence represents a scene with severe occlusion. The scene depicted in the MOT17 video sequence is a street between two buildings. Certain areas within the sequence feature relatively dense targets and moderate occlusion.

5. Conclusions

A robust tracking-by-detection framework named OcclusionTrack has been proposed to address key challenges in dense multi-object tracking, particularly those arising from occlusions and camera motion. The framework integrates four core improvements into a cohesive pipeline: (1) a confidence-based Kalman filter (CBKF) for adaptive state update under partial occlusion; (2) camera motion compensation (CMC) for inter-frame alignment; (3) a depth–cascade-matching (DCM) algorithm for association in overlapping scenarios; and (4) a CMC-detection-based trajectory Re-activate method for recovering from complete occlusion.

The effectiveness of the proposed method has been validated through comprehensive experiments on the MOT17, MOT20, and DanceTrack benchmarks. OcclusionTrack achieves highly competitive performances, notably improving IDF1 by 2.4 and reducing ID switches by nearly 50% over the ByteTrack baseline on the MOT17 test set, improving IDF1 by 2.3 and reducing ID switches by nearly 25% over the ByteTrack baseline on the MOT20 test set, and improving IDF1 and HOTA by 4.5 and 9.8 over the ByteTrack baseline on the DanceTrack test set.

The experimental results demonstrate that all the predefined research objectives have been met to a certain extent, with quantitative evidence supporting each contribution:

- (1)

- Objective 1 (Handling Partial Occlusion Challenges during Kalman Filter Update): To mitigate the impact of detection quality degradation during partial occlusion, the CBKF module was designed. Its efficacy is confirmed through experiments, where its introduction leads to the +0.3 IDF1 improvement on both the MOT17 and MOT20 validation sets. This gain is attributed to the module’s ability to dynamically change the weight of detections during the Kalman update, preventing trajectory drift.

- (2)

- Objective 2 (Compensation for Camera Motion): To stabilize the prediction base for IoU matching, a CMC module was incorporated. Results indicate a +0.9 IDF1 increase on the MOT17 validation set. It is the component with the greatest improvement among the four. More importantly, its application is a prerequisite for the effective functioning of the reactivation mechanism, showcasing its systemic value beyond a direct performance bump.

- (3)

- Objective 3 (Robust Association under Occlusion): To resolve ambiguities in dense, overlapping scenes, the DCM algorithm was integrated. DCM contributes significant gains, boosting IDF1 by +0.4 on the MOT20 validation set. This confirms that depth-level partitioning effectively addresses complex inter-object interactions.

- (4)

- Objective 4 (Correction for Complete Occlusion): To address error accumulation in lost tracks, a Re-activate method was proposed. While its isolated impact is smaller (+0.1 HOTA) on the MOT20 validation set, its role in maintaining long-term identity consistency is critical.

While demonstrating strong performance, the portability and effectiveness of OcclusionTrack are subject to certain conditions which define its scope of applicability:

- (1)

- Dependence on Detector: Experiments demonstrate that TBD trackers are highly dependent on detector performance, with higher-quality detectors significantly improving tracking accuracy. Additionally, the CBKF module relies on the confidence scores from the detector being reasonably calibrated to detection quality. Performance may degrade if confidence scores are not predictive of localization accuracy.

- (2)

- Assumption for Camera Motion Scenario: The CMC module employs a global 2D model, which assumes dominant, low-frequency camera motion. Its effectiveness may diminish in scenarios with highly dynamic, non-planar backgrounds or very high-frequency jitter. Moreover, it cannot meet the requirements of 3D scenes.

- (3)

- Scene-Type Specificity: The current motion model retains a linear constant-velocity assumption. Consequently, tracking performance can decline in sequences with extremely low frame rates or highly non-linear, agile object motion. Furthermore, the framework is primarily designed and tested on pedestrians, and its extension to objects with highly deformable shapes may require adjustments.

Future research will focus on enhancing generalizability by (1) exploring the joint optimization of the detector and tracker components to reduce dependency on the performance of the detections; (2) investigating adaptive, scene-aware CMC strategies that can handle more diverse camera dynamics; and (3) developing deep, data-driven motion models to replace the linear Kalman predictor for handling complex motions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and F.M.; methodology, Y.C. and F.M.; software, Y.C.; validation, Y.C.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Y.C., F.M. and Z.C.; resources, F.M., Y.C. and Z.C.; data curation, Y.C. and Z.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, F.M.; visualization, Z.C.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the New Generation Information Technology Innovation Project under Grant 2021ITA10002, in part by the Sichuan Provincial Key Research and Development Program under Grant 2025YFHZ0006, and in part by the Sichuan University of Science and Engineering Talent Introduction Program under Grant 2025RCZ064.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are presented in https://motchallenge.net/ and https://github.com/DanceTrack/DanceTrack (accessed on 7 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full Term |

| OCCTrack | OcclusionTrack |

| MOT | Multi-Object Tracking |

| CBKF | Confidence-Based Kalman Filter |

| CMC | Camera Motion Compensation |

| DCM | Depth–Cascade-Matching |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| TBD | Tracking-By-Detection |

References

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upadhya, A. Simple Online and Realtime Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8296962 (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking byassociating every detection box. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems; Wiley Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 82D, pp. 35–45. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5311910 (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Aharon, N.; Orfaig, R.; Bobrovsky, B.Z. BoT-SORT: Robust Associations Multi-Pedestrian Tracking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.14651. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiolino, G.; Ahmad, A.; Cao, J.; Kitani, K. Deep OC-SORT: Multi-pedestrian tracking by adaptive re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 3025–3029. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10222576 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Bai, X. Sparsetrack: Multi-object tracking by performing scene decomposition based on pseudo-depth. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 4870–4882. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10819455 (accessed on 4 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, F.; Gong, T.; Meng, H. Strongsort: Make deepsort great again. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 8725–8737. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10032656 (accessed on 22 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Pang, J.; Weng, X.; Khirodkar, R.; Kitani, K. Observation-Centric SORT: Rethinking SORT for Robust Multi-Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 9686–9696. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lin, R.S.; Han, M.; Zeng, D. Diffmot: A real-time diffusion-based multiple object tracker with non-linear prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 19321–19330. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Wei, X.; Xian, W.; Qin, Y. KalmanFormer: Integrating a Deep Motion Model into SORT for Video Multi-Object Tracking. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9727. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/15/17/9727 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Bradski, G. The opencv library. Dr. Dobb’s J. Softw. Tools Prof. Program. 2000, 25, 122–125. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233950935_The_Opencv_Library (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Shi, J. Good features to track. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 21–23 June 1994; pp. 593–600. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/323794 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/358669.358692 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Milan, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Reid, I.; Roth, S.; Schindler, K. Mot16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.00831. [Google Scholar]

- Dendorfer, P.; Rezatofighi, H.; Milan, A.; Shi, J.; Cremers, D.; Reid, I.; Roth, S.; Schindler, K.; Leal-Taixé, L. Mot20: A benchmark for multi object tracking in crowded scenes. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.09003. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Wang, J. DanceTrack: Multi-Object Tracking in Uniform Appearance and Diverse Motion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9879192 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Bernardin, K.; Stiefelhagen, R. Evaluating multiple object tracking performance: The clear mot metrics. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2008, 2008, 246309. Available online: https://jivp-eurasipjournals.springeropen.com/articles/10.1155/2008/246309 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Luiten, J.; Osep, A.; Dendorfer, P.; Torr, P.; Geiger, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Leibe, B. Hota: A higher order metric for evaluating multi-object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 548–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristani, E.; Solera, F.; Zou, R.; Cucchiara, R.; Tomasi, C. Performance measures and a data set for multi-target, multi-camera tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–10 and 15–16 October 2016; pp. 17–35. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-48881-3_2 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Pang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Lu, C. Tubetk: Adopting tubes to track multi-object in a one-step training model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 6308–6318. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Koltun, V.; Krähenbühl, P. Tracking objects as points. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 474–490. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ban, Y.; Delorme, G.; Gan, C.; Rus, D.; Alameda-Pineda, X. TransCenter: Transformers with Dense Representations for Multiple-Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 7820–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. Fairmot: On the fairness of detection and re-identification in multiple object tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Wang, J.; You, Q.; Ling, H.; Liu, Z. Transmot: Spatial-temporal graph transformer for multiple object tracking. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.00194. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10030267 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Stadler, D.; Beyerer, J. Modelling ambiguous assignments for multi-person tracking in crowds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2022; pp. 133–142. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9707576 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Yang, M.; Han, G.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, D. Hybrid-sort: Weak cues matter for online multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; pp. 6504–6512. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, K.; Luo, K.; Luo, X.; Huang, J.; Wu, H.; Hu, R.; Hao, W. Ucmctrack: Multi-object tracking with uniform camera motion compensation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; pp. 6702–6710. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Ke, W.; Xiong, Z. Multiplex labeling graph for near-online tracking in crowded scenes. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 7892–7902. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9098857 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Sun, P.; Cao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xie, E.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; Luo, P. Transtrack: Multiple-object tracking with transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.15460. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Xia, W. Semi-TCL: Semi-supervised track contrastive representation learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.02396. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, E.; Li, Z.; Han, S.; Wang, H. RelationTrack: Relation aware multiple object tracking with decoupled representation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.04322. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9709649 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Qin, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wang, L.; Duan, J.; Hua, G.; Tang, W. MotionTrack: Learning Robust Short-term and Long-term Motions for Multi-Object Tracking. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.10404. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Cao, J.; Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Yuan, J. Track to detect and segment: An online multi-object tracker. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12352–12361. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9578864 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Zeng, F.; Dong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. MOTR: End-to-end multiple-object tracking with transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 659–675. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).