Chemical Transformations and Papermaking Potential of Recycled Secondary Cellulose Fibers for Circular Sustainability

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context: Cellulose Fibers as Renewable Resources and the Circular Economy in the Paper Industry

1.1.1. Cellulose Fibers as Renewable Biomaterials

1.1.2. The Paper Industry and the Circular Economy

1.2. Significance of Recycling Waste Paper for Sustainability

2. Sources and Properties of Secondary Cellulose Fiber

2.1. Overview of Primary vs. Secondary Fibers

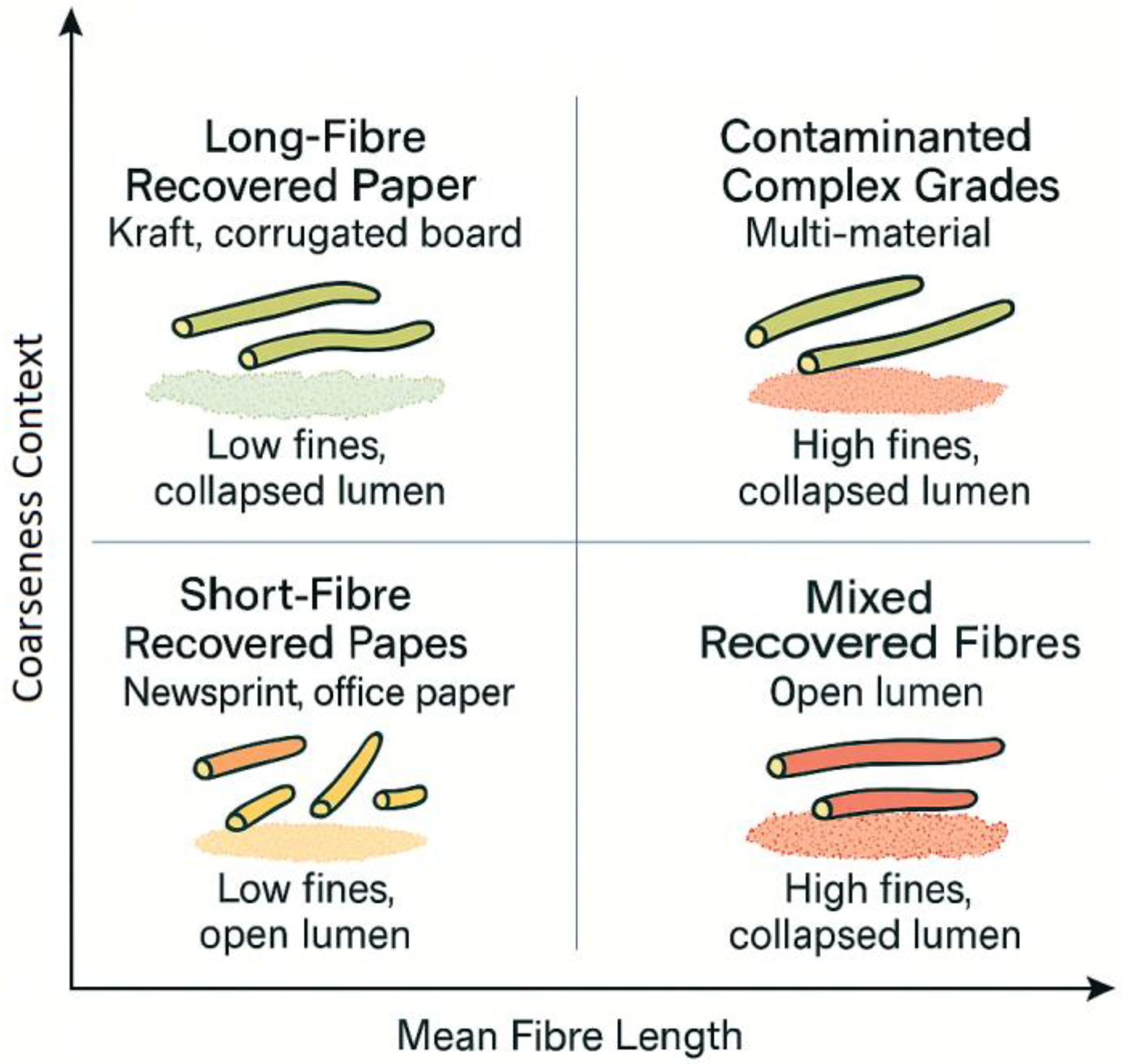

2.2. Main Waste Paper Sources

2.3. Quality Parameters and Contaminants Affecting Fiber Chemistry

3. Chemical and Structural Effects of Fiber Recycling

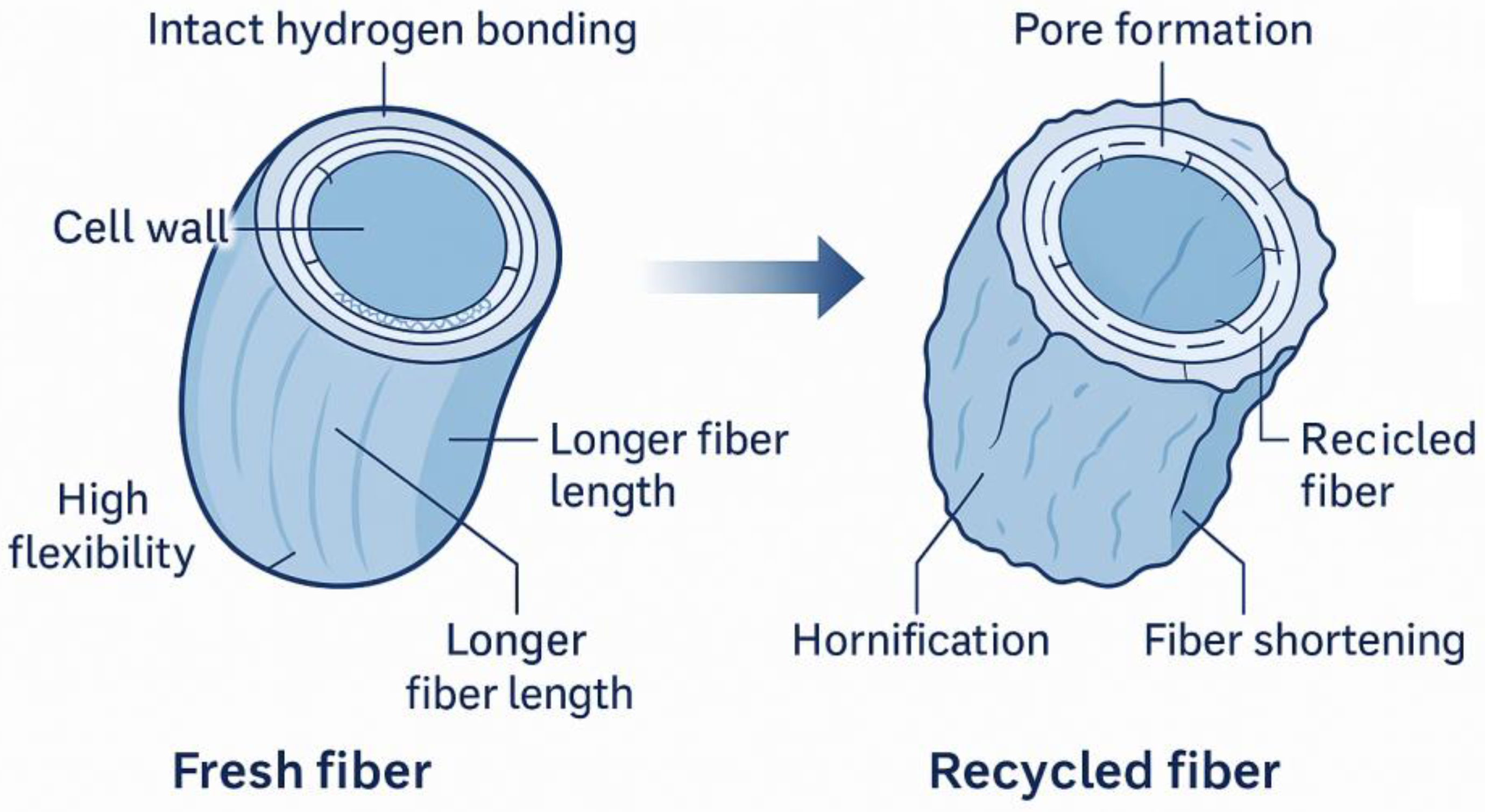

3.1. Dimensional and Morphological Changes

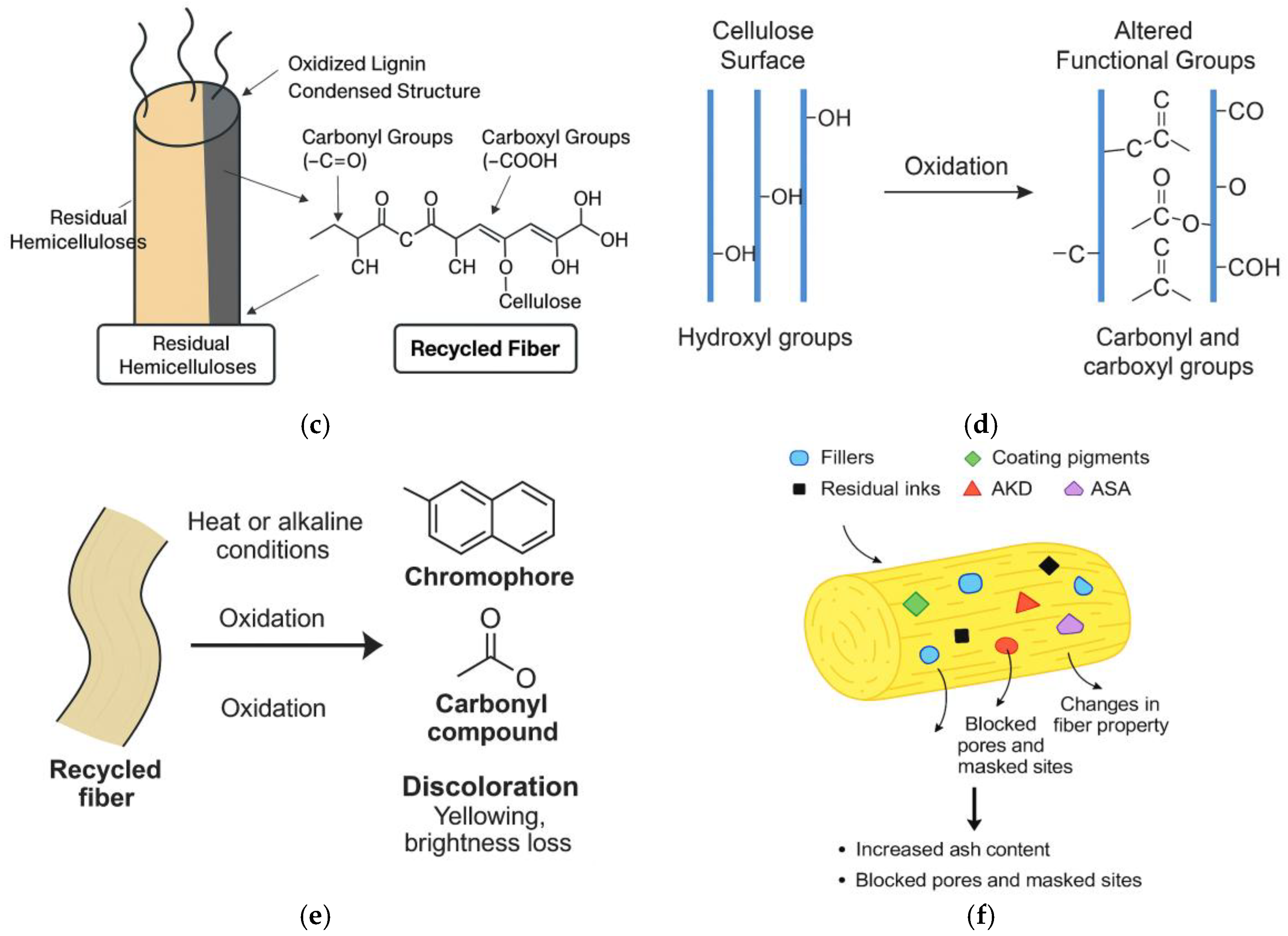

3.2. Chemical Composition and Functional Group Alterations

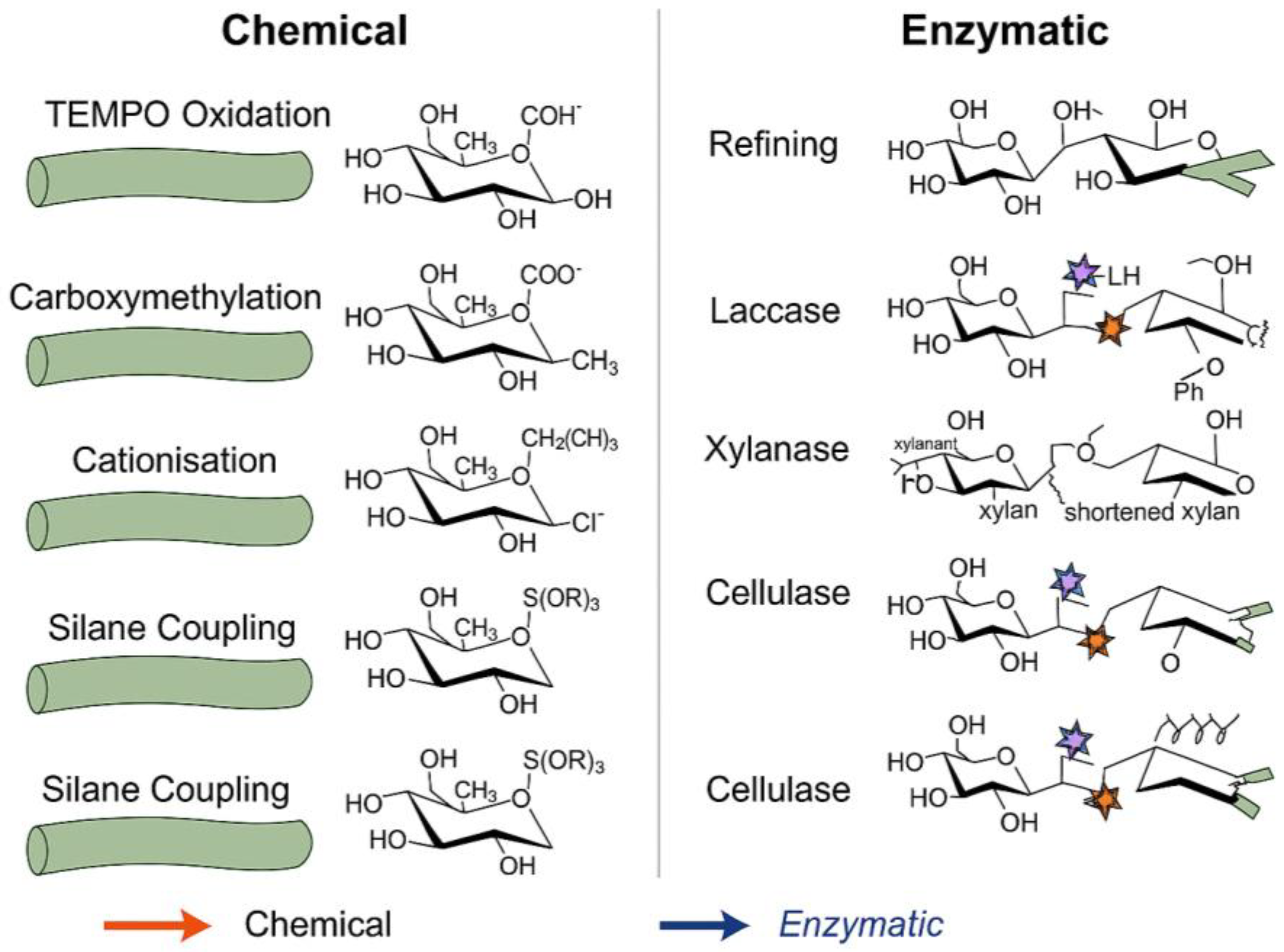

3.3. Chemical and Enzymatic Modification Strategies for Recycled Fibers

3.3.1. Cellulose Nanomaterials from Recycled Pulp and Their Use in Recycled Paper

3.3.2. Green Functionalization Routes: Cationic/Biobased Systems and Surface Modification

3.3.3. Synergistic Enzyme Systems and Integration with Biorefinery Concepts

3.4. Hornification and Fiber Swelling Behavior

3.5. Crystallinity and Cell Wall Structure

3.5.1. From Hydrated Networks to Compact Walls

3.5.2. Crystallinity Changes and What They Mean

3.5.3. Pore Size Distribution and Accessibility

3.5.4. Microfibril Arrangement and Mechanics

3.5.5. How Refining and Treatments Interact with Crystallinity

3.5.6. Tools to Measure and Monitor

- XRD/WAXS for CI, crystallite size, and peak broadening;

- Solid-state 13C NMR for crystalline vs. amorphous fractions and paracrystalline disorder;

- FTIR/Raman band ratios linked to order and hydrogen-bonding environment;

- WRV/FSP and NMR relaxometry for bound water and accessible porosity;

- AFM/SEM for surface fibrillation and wall densification.

3.5.7. Implications for Circular Use

3.6. Surface Chemistry and Fiber Reactivity

3.7. Fines Formation and Its Role in Recycled Fiber Systems

3.7.1. Origins and Types of Fines in Recycling

3.7.2. Effects of Fines on Suspension Behavior, Drainage, and Retention

3.7.3. Contributions of Fines to Sheet Structure and Properties

3.7.4. Chemical Interactions and “Anionic Trash”

3.7.5. Interplay with Hornification and Crystallinity

3.7.6. Process Control and Management Strategies

- Fractionation and white-water management. Hydrocycloning and fine-screening can remove grit and macro-contaminants while allowing retention of beneficial fibrillar fines. White-water clarification (DAF, save-all filters) prevents uncontrolled fines accumulation and closes the mass balance without overloading the headbox [72,83].

- Optimized refining. Light, targeted refining increases external fibrillation (beneficial fines) without excessive fiber cutting that would flood the system with detrimental fines. Refining intensity and specific edge load should be tuned to grade: packaging vs. print/tissue require different fines spectra [103,131].

- Retention/fixation programs. Sequential addition of fixatives (e.g., polyamines, PAC) to immobilize anionic trash on fines, followed by strength aids and a microparticle system, improves fines capture and drainage. Proper ionic strength and pH enhance floc architecture and release in the forming zone [53,64,104,132].

3.7.7. Implications for Circular Performance

3.8. Influence of Additives, Fillers, and Contaminants on Fiber Chemistry

3.9. Relationship Between Chemical and Morphological Degradation of Recycled Fibers

3.9.1. Drying-Induced Coupling: From Chemistry to Structure

3.9.2. Accessibility Feedbacks: From Structure Back to Chemistry

3.9.3. Hemicellulose Depletion and Fines Formation: Chemical–Mechanical Interactions Governing Bonding in Recycled Fibers

3.9.4. Lignin Oxidation Pathways and the Optical–Mechanical Tradeoffs in Recycled Fiber Systems

3.9.5. Surface Charge Dynamics, Contaminant Interactions, and Their Impact on Fiber Network Mechanics

3.9.6. Macroscopic Manifestations of Coupled Chemical and Morphological Degradation in Recycled Cellulose Fibers

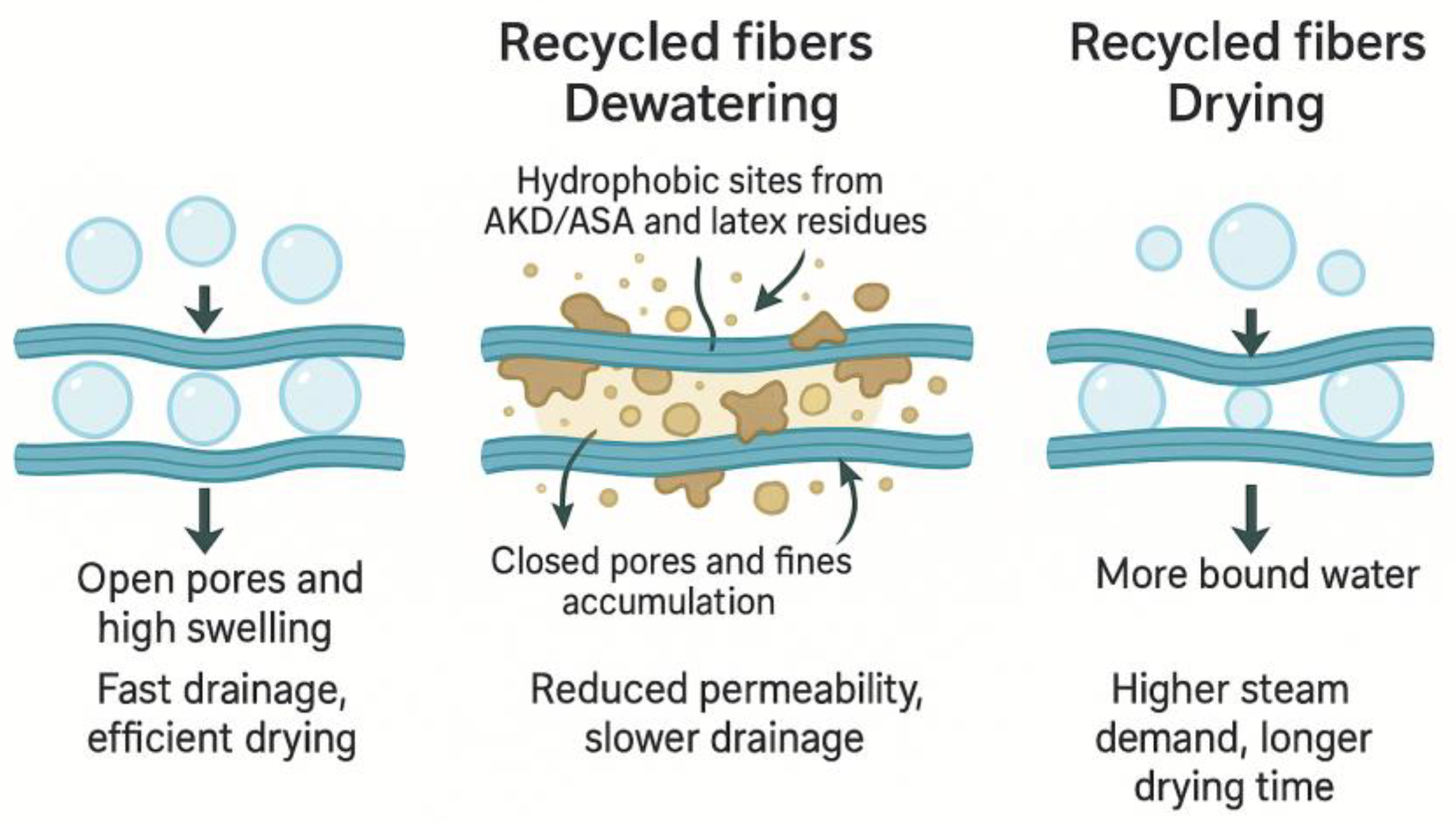

- —

- Lower tensile, burst, and often tear strength, attributable to shorter, stiffer fibers with reduced bonding area and to chemically weakened chains (lower DP).

- —

- Slower drainage and higher steam demand, caused by fines build-up and altered surface charge; densified walls also release water less readily in pressing.

- —

- Greater variability in sizing and printability, due to mosaic hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity from residual sizes and latexes on less-wettable surfaces.

- —

- Higher cationic demand and unstable wet-end chemistry, reflecting the combined effects of increased carboxyls, DCSs, and mineral fines.

3.9.7. Integrated Diagnostics for Correlating Chemical, Structural, and Performance Metrics Across Scales

- WRV/FSP (swelling) and XRD/FTIR/NMR (apparent crystallinity and hydrogen-bonding environment) to track hornification.

- DP (viscometry or SEC) for cellulose chain length; zeta potential and cationic demand for surface charge state.

- AFM/SEM for fibrillation and surface topography; fines/ash fractionation to characterize the fines spectrum.

3.9.8. Coupled Mitigation Strategies Integrating Chemical, Morphological, and Process Controls in Recycled Fiber Systems

- Gentle, targeted refining to restore external fibrillation and reopen access without excessive cutting (controls morphology, improves chemistry access).

- Selective enzymatic conditioning (low-dose endoglucanase/xylanase) or mild surface carboxymethylation to expose/reactivate sites and accelerate polymer uptake, while avoiding deep chain scission (improves chemistry, aided by morphological reopening).

- Wet-end sequencing (fixative → strength aid → microparticle) with ionic-strength/pH control to out-compete DCSs and stabilize floc architecture (chemistry control supporting structure).

- Contaminant management (detackifiers, talc, enhanced screening/DAF) to reduce hydrophobe carryover that would otherwise lock in poor wettability on densified walls.

- Drying profile moderation (temperature and residence time) and periodic virgin fiber supplementation to limit step-changes in hornification and restore long-fiber bonding scaffolds.

3.10. Mitigation Strategies and Chemical Approaches to Preserve Fiber Integrity

3.10.1. Physical and Process-Based Mitigation

3.10.2. Enzymatic and Biochemical Treatments

3.10.3. Chemical Surface Modification

3.10.4. Wet-End Chemistry Optimization

3.10.5. Thermal and Drying Control

3.10.6. Integrated Approach and Future Outlook

4. Influence of Recycled and Reused Fibers on Papermaking Performance

4.1. Impact of Recycled and Reused Secondary Cellulose Fibers on Paper Strength and Quality

4.2. Mechanical, Structural, and Surface Property Evolution in High-Recycled-Content Papers

4.3. Effect of Recycled and Reused Fibers on Dewatering and Drying Behavior

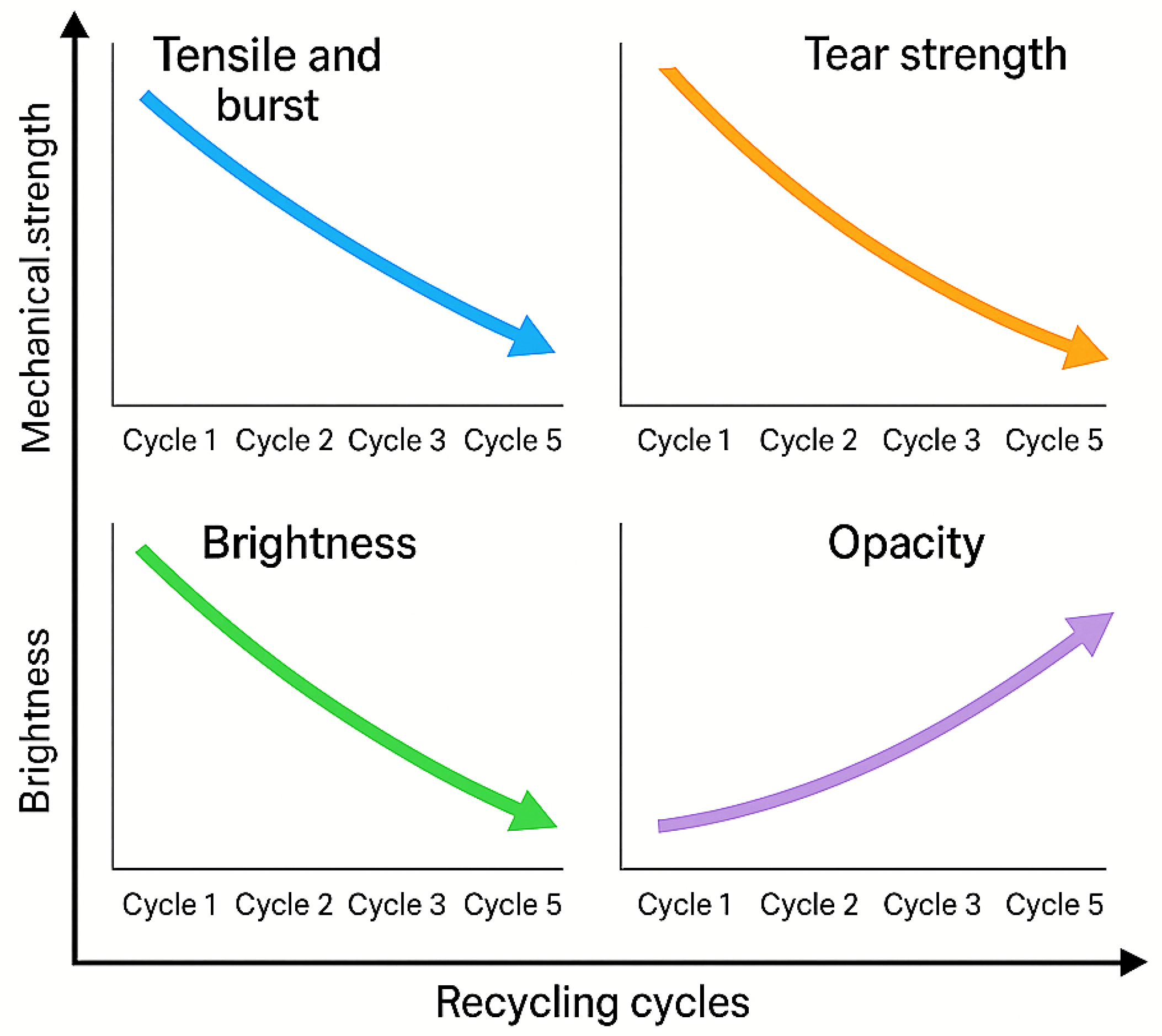

4.4. Influence of Recycling Cycles of Fibers on Paper Quality: Evolution of Mechanical and Optical Parameters with Successive Reuse

4.4.1. Mechanical Properties: Typical Trajectories Across Cycles

4.4.2. Optical Properties: Brightness, Shade, Opacity, and Print Uniformity

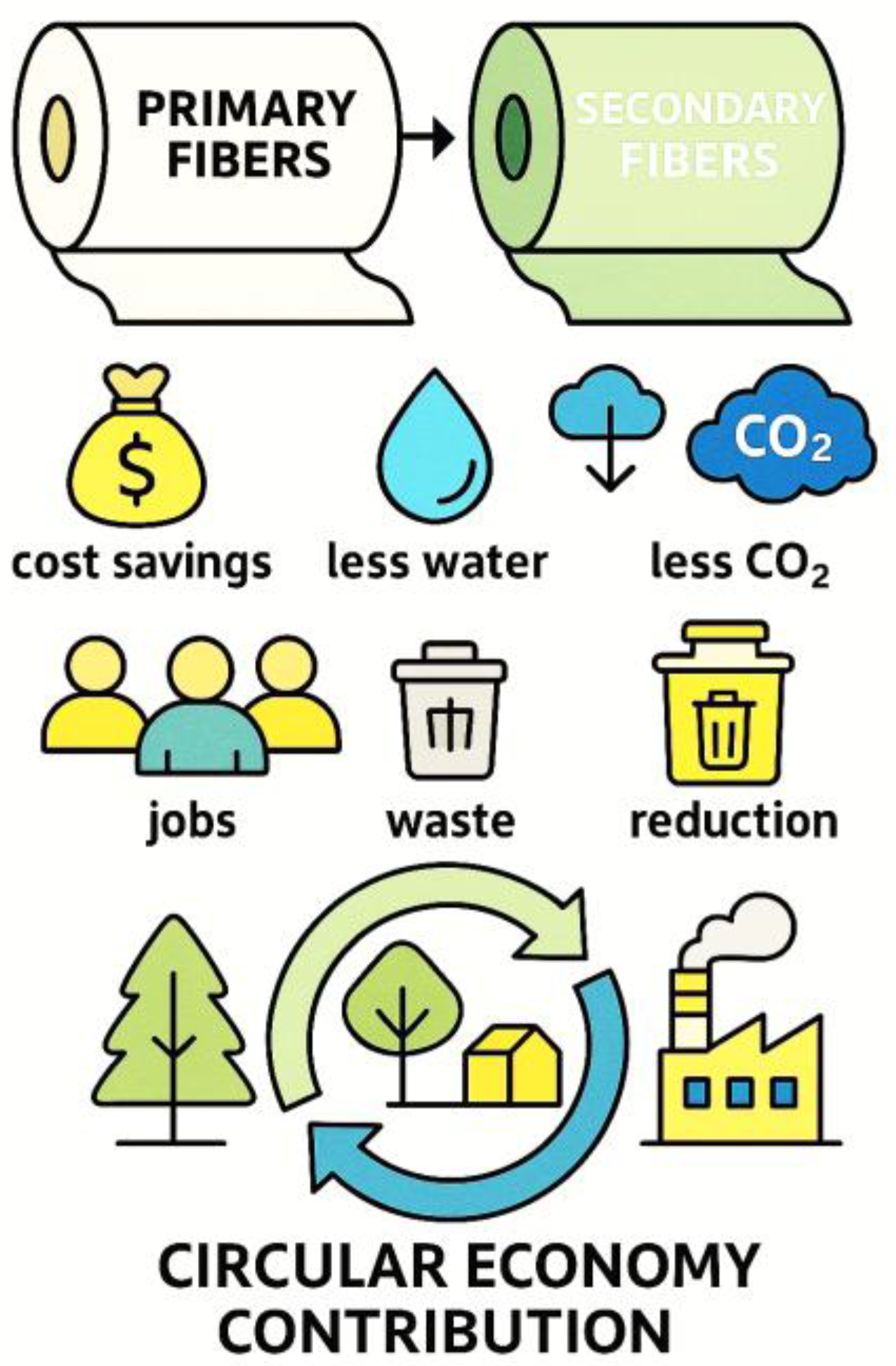

5. Environmental and Economic Impact of Fibers Recycle and Reuse

5.1. Comparison of Energy, Water, and CO2 Footprints: Primary vs. Secondary Fibers

- Recycled pulping avoids wood preparation and most chemical pulping stages, so total process energy per tonne is typically lower. Literature and industry LCAs report 20–60% lower process energy for many recycled grades compared with virgin equivalents, with the upper end for de-inking-free streams (e.g., Old Corrugated Containers (OCC) for packaging) and the lower end where de-inking and high consistency dispersion are required. Mills equipped with CHP/cogeneration further reduce the cradle-to-gate footprint by displacing grid electricity and improving steam efficiency [26,31].

- —

- Recycled mills often operate with tighter water circuits; despite wash steps in de-inking, specific make-up water can be similar or lower than virgin mills when white-water closure and DAF are implemented. Reported savings range from 15 to 50% relative to virgin kraft baselines, but local water management (e.g., loop closure vs. purge for DCS control) drives outcomes [135,178].

- —

- Several mechanisms reduce net GHGs: (i) avoided landfill prevents methane from anaerobic decomposition of paper, (ii) lower process energy (especially with CHP/renewables) cuts Scope 1–2 emissions, and (iii) biogenic carbon retention in recycled products extends storage time. Practical, cited rules-of-thumb indicate that recycling one tonne of paper avoids both energy use and GHG emissions, while meta-analyses show 20–70% lower cradle-to-gate GHG intensity depending on furnish and mill configuration [24,29]. When de-inking is intensive and electricity is carbon-intensive, the advantage narrows; conversely, clean OCC streams in efficient mills deliver the largest benefit.

5.2. Economic Efficiency: Cost Savings, Employment, and Waste Reduction

5.3. Contribution to the Circular Economy and Resource Conservation

5.3.1. Pathways Toward Circularity and Sustainable Resource Utilization

- —

- Material circularity:

- —

- Forest and biodiversity pressure:

- —

- Water and chemical stewardship:

- —

- Design for recyclability

- —

- System value restoration

5.3.2. Practical Implications for Mills and Policymakers

- Pair collection quality (source-separated streams, EN 643 adherence) with mill-side contaminant control (detackifiers, improved screening, DAF) to maximize both environmental gains and economic yield.

- Invest in energy efficiency and CHP to compound the GHG advantage of recycled operations; monitor steam per tonne and drying profiles to capture easy wins.

- Use real-time wet-end metrics (zeta potential, cationic demand, ines/ash) to stabilize retention and drainage, cutting energy and chemical overuse.

- Encourage design-for-recycling across the value chain (inks, adhesives, barrier choices) to improve de-inkability and fiber recovery, sustaining the sector’s circular performance.

6. Research Gaps and Future Perspectives

- Selective enzymatic surface modification prior to secondary refining increases external fibrillation without significant DP reduction, resulting in measurable improvements in bonding after three or more recycling cycles.

- Dual nanocellulose systems combining cationic and anionic fibrils yield superior strength enhancement compared with single-component CNF additives when applied to hornified fibers from advanced recycling loops.

- Bio-based polymer grafting (e.g., chitosan–CMC hybrids) can establish more resilient hydrogen-bond networks that retain bonding efficiency during subsequent drying–rewetting events and over multiple recycling cycles.

- TEMPO-oxidized nanocellulose produced from recycled pulps exhibits reinforcement efficiencies comparable to CNF from virgin sources when normalized to carboxyl content and fibril aspect ratio.

- Enzymatic pre-loosening of fiber walls reduces refining energy demand in closed-loop water circuits while maintaining strength improvements when scaled from laboratory to pilot-plant environments.

7. Conclusions

- Wet-end chemistry should be continuously monitored and adjusted through online charge and turbidity sensors to stabilize electrokinetic conditions.

- Refining intensity and chemical dosing should be tailored to furnish composition, aiming to maximize bonding fines while limiting detrimental fiber shortening.

- Sequential dosing of fixatives, cationic starch or PAE, and microparticles should be optimized by timing and mixing energy to enhance fines fixation and minimize additive waste.

- Periodic ash purging, combined with filler make-up strategies, should be implemented to maintain optical uniformity and thermal efficiency in drying.

- Detackifier and mineral surface treatments must be integrated into de-inking circuits to minimize stickies deposition and ensure cleaner white water systems.

- Developing bio-based and biodegradable polymers as multifunctional fixatives and retention agents compatible with closed water loops;

- Implementing machine-learning-based models to predict fines generation, floc structure evolution, and retention performance under varying conditions;

- Exploring the synergistic use of nanocellulose, biopolymers, and smart fillers to improve strength and optical properties at reduced fiber input;

- Investigating water and energy integration strategies that couple wet-end optimization with wastewater treatment and heat recovery systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marinho, E. Cellulose: A Comprehensive Review of its Properties and Applications. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2025, 11, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azka, M.A.; Adam, A.; Ridzuan, S.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Habib, A. A Review on the Enhancement of Circular Economy Aspects Focusing on Nanocellulose Composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, R.; Iftimi, V.; Gavrilescu, D. Sustainable Use of Recovered Paper—Romanian Paper Industry. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2012, 11, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podara, C.; Termine, S.; Modestou, M.; Semitekolos, D.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Karamitrou, M.; Trompeta, A.-F.; Milickovic, T.K.; Charitidis, C. Recent Trends of Recycling and Upcycling of Polymers and Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Recycling 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, A. Cellulose Fibre Innovation of the Year 2024: Nominated Innovations Range from Resource-Efficient and Recycled Fibres for Textiles and Building Panels to Geotextiles for Glacier Protection. 2024. Available online: https://renewable-carbon.eu/news/cellulose-fibre-innovation-of-the-year-2024-nominated-innovations-range-from-resource-efficient-and-recycled-fibres-for-textiles-and-building-panels-to-geotextiles-for-glacier-protection/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- International Paper. 2024 Sustainability Report; International Paper: Memphis, TN, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.internationalpaper.com/sites/default/files/file/2025-03/International%20Paper%20Annual%20Report%202024.pdf?cacheToken=azSbbqUqqKam37rW (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Suter, E.K.; Rutto, H.L.; Seodigeng, T.S.; Kiambia, S.L.; Omwoyo, W.N. Green Isolation of Cellulosic Materials from Recycled Pulp and Paper Sludge: A Box-Behnken Design Optimization. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2024, 59, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varnaite-Žuravliova, S.; Baltušnikaite-Guzaitiene, J. Properties, Production, and Recycling of Regenerated Cellulose Fibers: Special Medical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femina, C.C.; Kamalesh, T.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Hemavathy, R.V.; Rangasamy, G. A Critical Review on Sustainable Cellulose Materials and its Multifaceted Applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 203, 117221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Savithri, D. Cellulose Fibers as a Trendsetter for the Circular Economy that We Urgently Need. Bioresources 2021, 19, 2007–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subin, A.J.; Cowan, N.; Davidson, M.; Godina, G.; Smith, I.; Xin, J.; Menezes, P.L. A Comprehensive Review on Cellulose Nanofibers, Nanomaterials, and Composites: Manufacturing, Properties, and Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Wen, Y. Optimizing Enzymatic Pretreatment of Recycled Fiber to improve its Draining Ability using Response Surface Methodology. BioResources 2012, 7, 2121–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, E.; Morioka, S.N.; Neri, A.; de Souza, E.L. Understanding how Circular Economy Practices and Digital Technologies are Adopted and Interrelated: A Broad Empirical Study in the Manufacturing Sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 216, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE/FAO. Circularity Concepts in the Pulp and Paper Industry; ECE/TIM/DP/97 Forestry and Timber Section; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.greenindustryplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/ECE_TIM_DP97_2326213_E.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Levin, K.J.; Costa, D.d.S.; Urb, L.; Peikolainen, A.-L.; Venderström, T.; Tamm, T. Feasibility of a Sustainable On-Site Paper Recycling Process. Recycling 2025, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puitel, A.C.; Campean, T.; Grad, F.; Gavrilescu, D. Sustainable Use of Recovered Paper—Romanian Paper Industry. Part II—Environmental Impact. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Sjöstrand, B.; Lestelius, M.; Håkansson, H.; Swerin, A.; Henriksson, G. Swelling of Cellulosic Fibers in Aqueous Systems: A Review of Chemical and Mechanistic Factors. BioResources 2024, 19, 6859–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPI. Key Statistics 2023; Confederation of European Paper Industries, CEPI: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://www.cepi.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Key-Statistics-2023-FINAL-2.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- EPRC. Monitoring Report 2023; European Paper Recycling Council, EPRC: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://www.cepi.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/24-4378_EPRC_2023_Singlepages.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2025/40 on Packaging and Packaging Waste of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2024 on packaging and packaging waste, amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904. Off. J. Eur. Union 2025, L 40, 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Risks and Resilience in Global Trade. Key Trends in 2023–2024; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/12/risks-and-resilience-in-global-trade_c8a001ff/1c66c439-en.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Scott, S.; Ireland, R. China’s Recycled Wastepaper Import Policies: Part 2 Economic Effects and Implications for Associated Industries; United States International Trade Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/executive_briefings/ebot_trade_in_wastepaper.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Qin, S.; Chen, Y.; Tao, D.; Zhang, C.; Qin, X.; Chen, P.; Qi, H. High Recycling Performance of Holocellulose Paper Made from Sisal Fibers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, M.; Imani, M.; Ivanovska, A.; Radojevic, V.; Dimic-Misic, K.; Barac, N.; Stojanovic, D.; Janackovic, D.; Uskokovic, P.; Barcelo, E.; et al. Extending Waste Paper, Cellulose and Filler Use Beyond Recycling by Entering the Circular Economy Creating Cellulose-CaCO3 Composites Reconstituted from Ionic Liquid. Cellulose 2022, 29, 5037–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.D.A.; Nowshin, N.; Uddin, M.M.; Aquib, T.I. Recovery of Cellulose Fibers from Waste Books and Writing Paper by Flotation De-inking. N. Am. Acad. Res. 2024, 7, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiçekler, M.; Tutuş, A. Assessing the Advantages and Disadvantages of Paper Recycling for Sustainable Resource Management: A Systematic Review. In Contemporary Perspectives in Forest Industry Engineering: A Comprehensive Review (65–96); Tutuş, A., Çiçekler, M., Eds.; SRA Academic Publishing: Klaipeda, Lithuania, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, T.; Frattali, A.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y. Regenerated Cellulose Fibers (RCFs) for Future Apparel Sustainability: Insights from the U.S. Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, R.; Iftimi, V.; Gavrilescu, D. Resource Conservation in Sanitary Paper Manufacturing. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2022; Report EPA 430-R-24-004; U.S.; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Shred-It. Paper Recycling: How Does It Help the Environment? 2024. Available online: https://www.shredit.co.uk/en-gb/blog/sustainability/how-does-recycling-paper-help-the-environment?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G. Environmental Assessment of the Recycled Paper Production: The Effects of Energy Supply Source. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, T. Making a Difference: The Environmental Benefits of Recycling Paper; Domtar: Fort Mill, SC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.domtar.com/making-a-difference-the-environmental-benefits-of-recycling-paper/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Kumar, V.; Kalra, J.S.; Verma, D.; Gupta, S. Process and Environmental Benefit of Recycling of Waste Papers. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNees, M. DS Smith to Upgrade, U.K.-Based Kemsley Recycled Paper Mill. Recycl. Today. 2024. Available online: https://www.recyclingtoday.com/news/ds-smith-to-upgrade-paper-machine-at-recycled-paper-mill-in-england/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bajpai, P. Pulp and Paper Industry. Energy Conservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smook, G.A. Handbook for Pulp & Paper Technologists, 3rd ed.; TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Congthai, W.; Phosriran, C.; Chou, S.; Onsanoi, K.; Gosalawit, C.; Cheng, K.-C.; Jantama, K. Exploiting Mixed Waste Office Paper Containing Lignocellulosic Fibers for Alternatively Producing High-Value Succinic Acid by Metabolically Engineered Escherichia coli KJ122. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burggräfa, P.; Steinberg, F.; Sauera, C.R.; Nettesheima, P.; Wiggera, M.; Bechera, A.; Greiff, K.; Raulf, K.; Spies, A.; Köhler, H.; et al. Boosting the Circular Manufacturing of the Sustainable Paper Industry—A First Approach to Recycle Paper from Unexploited Sources such as Lightweight Packaging, Residual and Commercial Waste. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P. Recycling and Deinking of Recovered Paper; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EN 643:2014; European List of Standard Grades of Paper and Board for Recycling. Confederation of European Paper Industries (CEPI) and the European Recovered Paper Council (ERPC): Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Arafat, K.M.Y.; Salem, K.S.; Bera, S.; Jameel, H.; Lucian, L.; Pal, L. Surfactant-Modified Recycled Fibers for Enhanced Dewatering and Mechanical Properties in Sustainable Packaging. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2025, 12, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kóczán, Z.; Pásztory, Z. Overview of Natural Fiber-Based Packaging Materials. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2301364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, J.; Hirtz, D.; Sängerlaub, S. Expert Survey on the Impact of Cardboard and Paper Recycling Processes, Fiber-Based Composites/Laminates and Regulations, and Their Significance for the Circular Economy and the Sustainability of the German Paper Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HeadworksBio. Case Study: Inland Empire Paper Company. 2018. Available online: https://www.headworksinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Inland-Empire-Paper-Company-Case-Study.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- StoraEnso. Transformation Towards a Circular Bioeconomy. 2025. Available online: https://www.storaenso.com (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Smurfit Kappa. Sustainability Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.smurfitkappa.com (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.M.; Ferdous, T.; Hossen, M.N.; Jahan, M.S. Fractionation of Old Corrugated Containers for Manufacture of Test Liner and Fluting Paper. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2024, 58, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirarotepinyo, N.; Nguyen, J.; Cross, A.; Jameel, H.; Venditti, R.A. Impact of Multiple Paper Recycle Loops on the Yield and Properties of Wood Fibers and of Non-Wood Wheat Straw Fibers for Packaging. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkovic, I.B.; Bolanca, Z.; Medek, G. Impact of Aging and Recycling on Optical Properties of Cardboard for Circular Economy. Recycling 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipova, I.; Andze, L.; Skute, M.; Zoldners, J.; Irbe, I.; Dabolina, I. Improving Recycled Paper Materials through the Incorporation of Hemp, Wood Virgin Cellulose Fibers, and Nanofibers. Fibers 2023, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Marcello, C.; Sawant, N.; Salam, A.; Abubakr, S.; Qi, D.; Li, K. Identification and Characterization of Sticky Contaminants in Multiple Recycled Paper Grades. Cellulose 2023, 30, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Ghosh, D.; Haritos, V.; Batchelor, W. Recycling Cellulose Nanofibers from Wood Pulps Provides Drainage Improvements for High Strength Sheets in Papermaking. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 312, 127731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmas, G.M.; Karabulut, B. Determination of Fines in Recycled Paper. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2023, 38, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lejarraga, P.; Martin-Iglesias, S.; Moneo-Corcuera, A.; Colom, A.; Redondo-Morata, L.; Giannotti, M.I.; Petrenko, V.; Monleón-Guinot, I.; Mata, M.; Silvan, U.; et al. The Surface Charge of Electroactive Materials Governs Cell Behaviour through its Effect on Protein Deposition. Acta Biomater. 2024, 184, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Gill, R.A. Fillers for papermaking: A review of their properties, usage practices, and their mechanistic role. BioRes 2016, 11, 2886–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, G.K.; Panjagari, N.R.; Alam, T. An overview of paper and paper based food packaging materials: Health safety and environmental concerns. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 4391–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Chen, K.; Yang, X.; Kong, F.; Liu, J.; Li, B. Elucidating the Hornification Mechanism of Cellulosic Fibers during the Process of Thermal Drying. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 289, 119434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wan, J.; Wu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Huang, M. Effect of Recycling on Fundamental Properties of Hardwood and Wheat Straw Pulp Fibers, and of Handsheets Made Thereof. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, U.; Tutuş, A.; Sönmez, S. Fiber Classification, Physical and Optical Properties of Recycled Paper. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.K.; Kapoor, R.K.; Chhabra, D.; Bhardwaj, N.K.; Shukla, P. Synergistic Effect of Cellulo-Xylanolytic and Laccase Enzyme Consortia for Improved Deinking of Waste Papers. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 408, 131173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, A.d.O.; Vieira, J.C.; Costa, V.L.D.; Pinto, P.; Soares, B.; Barata, P.; Curto, J.M.R.; Amaral, M.E.; Costa, A.P.; Fiadeiro, P.T. Macro Stickies Content Evaluation of Different Cellulose-Based Materials Through Image Analysis. Recycling 2025, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska, E. Impact of Retention Agents on Functional Properties of Recycled Paper in Sustainable Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, R.; Wang, W.-J.; Lim, K.H.; Yang, X. Papers with High Filler Contents Enabled by Nanocelluloses as Retention and Strengthening Agents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 358, 123506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslana, K.; Sielicki, K.; Wenelska, K.; Kedzierski, T.; Janusz, J.; Marianczyk, G.; Gorgon-Kuza, A.; Bogdan, W.; Zielinska, B.; Mijowska, E. Facile Strategy for Boosting of Inorganic Fillers Retention in Paper. Polymers 2024, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, H.; Li, R.Z.; Mu, R.H.; Hou, H.Y.; Ma, T.T. Molecular Dynamics Study on Effects of the Synergistic Effect of Anions and Cations on the Dissolution of Cellulose in Ionic Liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 415 Pt A, 126348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, A.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Asikainen, J. Effects of Hydrophobic Sizing on Paper Dry and Wet-Strength Properties: A Comparative Study between AKD Sizing of NBSK Handsheets and Rosin Sizing of CTMP Handsheets. BioResources 2021, 16, 5350–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, N.N.; Madikizela, L.M.; Tiggelman, I.; Chimuka, L. Chemical Profiling of Paper Recycling Grades using GC-MS and LC-MS: An Exploration of Contaminants and their Possible Sources. Waste Manag. 2024, 189, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 57; Ding, L.; Tian, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Q.; Fang, G. Ozone/Biological Aerated Filter Integrated Process for Recycled Paper Mill Wastewater: A Pilot-Scale Study. Biochem. Eng. J. 2024, 211, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langberg, H.A.; Arp, H.P.H.; Castro, G.; Asimakopoulos, A.G.; Knutsen, H. Recycling of Paper, Cardboard and its PFAS in Norway. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2024, 5, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, J.Y. Effects of Drying-Induced Fiber Hornification on Enzymatic Saccharification of Lignocelluloses. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2011, 48, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keränen, J.Y.; Retulainen, E. Changing Quality of Recycled Fiber Material. Part 1. Factors Affecting the Quality and an Approach for Characterisation of the Strength Potential. BioResources 2016, 11, 10404–10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najideh, R.; Rahmaninia, M.; Khosravani, A. Recyclability of Wastepaper Containing Cellulose Nanofibers. BioResources 2024, 19, 8712–8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Deng, T.; Fu, Q. The Effect of Fiber End on the Bonding Mechanical Properties between SMA Fibers and ECC Matrix. Buildings 2023, 13, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstrand, B.; Karlsson, C.-A.; Barbier, C.; Henriksson, G. Hornification in Commercial Chemical Pulps: Dependence on Drying Temperature. BioResources 2024, 19, 7042–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, M.; Kilpeläinen, I.; Hietala, S. Interaction of Cellulose and Water Upon Drying and Swelling by 13C CP/MAS NMR. Cellulose 2024, 31, 10745–10769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schreeb, A.; Sjöstrand, B.; Ek, M.; Henriksson, G. Drying and Hornification of Swollen Cellulose. Cellulose 2025, 32, 5179–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, T.; Phiri, J.; Zitting, A.; Paajanen, A.; Penttilä, P.; Ceccherini, S. Deaggregation of Cellulose Macrofibrils and its Effect on Bound Water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 319, 121166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Kose, R.; Akada, N.; Okayama, T. Relationship between Wettability of Pulp Fibers and Tensile Strength of Paper during Recycling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, R.; Brondi, M.; Elias, A.M.; Farinas, C.S.; Ribeiro, C. Mechanochemical Recycling of cellulose Multilayer Carton Packages to Produce Micro and Nanocellulose from the Perspective of techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 363, 121254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervos, S.; Alexopoulou, I. Paper Conservation Methods: A Literature Review. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2859–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Tanase, C.E. Design, Characterization and Preliminary Biological Evaluation of New Lignin-PLA Biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska, E.; Dubowik, M.; Przybysz, P. Morphological Differences between Virgin and Secondary Fibers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P. Biermann’s Handbook of Pulp and Paper: Raw Material and Pulp Making; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemzehi, M.; Sjöstrand, B.; Håkansson, H.; Henriksson, G. Degrees of Hornification in Softwood and Hardwood Kraft Pulp during Drying from Different Solvents. Cellulose 2024, 31, 1813–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Park, H.-H.; Lee, T.-G.; Park, J.-H.; Park, M.-S.; Lee, J.-S. Comparative Analysis of Fiber Characteristics on Recycling Potential and Paper Properties of Milk Cartons and PE-Coated Cardboard. J. Korea TAPPI 2025, 57, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, I. Surface Characterization of Pulp Fiber from Mixed Waste Newspaper and Magazine Deinked-Pulp with Combined Cellulase and Laccase-Violuric Acid System (LVS). Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 23, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Sun, X.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, P.; Yu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, F. Effect of Hornification on the Isolation of Anionic Cellulose Nanofibrils from Kraft Pulp via Maleic Anhydride Esterification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 333, 121961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhushree, M.; Vairavel, P.; Mahesha, G.T.; Subrahmanya Bhat, K. Oxidative Modifications of Cellulose: Methods, Mechanisms, and Emerging Applications. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2497910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Mondal, M.; Chakraborty, J.; Sing, N.; Ghosh, B.; Roy, S.; Mahali, K. Advances in Upcycling Waste Cellulose into Functional Materials: Strategies, Challenges, and Emerging Applications—A comprehensive Review. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, F.; Modelli, A. Oxidative Degradation of Non-Recycled Cellulosic Paper Materials: A Spectroscopic Study. Cellulose 2020, 27, 10659–10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjoum, N.; Grimi, N.; Benali, M.; Chadni, M.; Castignolles, P. Extraction and Chemical Features of Wood Hemicelluloses: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 143681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbe, M.; Venditti, R.; Rojas, O. What Happens to Cellulosic Fibers During Papermaking and Recycling? A Review. BioResources 2007, 2, 739–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wan, J.; Ma, Y.; Tang, B.; Han, W.; Ragauskas, A.J. Modification of old corrugated container pulp with laccase and laccase–mediator system. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tze, W.Z.; Gardner, D.J. Swelling of Recycled Wood Pulp Fibers: Effect on Hydroxyl Availability and Surface Chemistry. Wood Fiber Sci. 2001, 33, 364–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, C.; Rao, N.J.; Singh, S.P. Effect of Recycling on Fibre Characteristics; Indian Pulp & Paper Technical Association: Saharanpur, India, 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pfennich, A.C.; Lammer, H.; Hirn, U. Aging Effects on Paper Dispersibility—A Review. BioResources 2026, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcu, A.; Sahin, H.T. Chemical Treatment of Recycled Pulp Fibres for Property Development: Part 1. Effects on Bleached Kraft Pulps. Drewno 2017, 60, 95–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Emsley, A.M.; Herman, H.; Heywood, R.J. Spectroscopic Studies of the Ageing of Cellulosic Paper. Polymer 2001, 42, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesan, A.K.; Bolarinwa, O.Y.; Temitope, O.L. Impact of Kaolin on Physicomechanical Properties of Density-graded Cement Bonded Paperboards. Bioresources 2020, 15, 6033–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signori-Iamin, G.; Aguado, R.J.; Tarrés, Q.; Santos, A.F.; Delgado-Aguilar, M. Exploring the Synergistic Effect of Anionic and Cationic Fibrillated Cellulose as sustainable Additives in papermaking. Cellulose 2024, 31, 9349–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Xu, D.; Luo, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, W.; Leng, X.; Dai, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ahmad, H.; Rao, J.; et al. Overview of Nanocellulose as Additives in Paper Processing and Paper Products. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, T.; Silva, A.C.; Machado, G.; Chaves, D.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Fangueiro, R.; Ferreira, D.P. Reinforcing Cotton Recycled Fibers for the Production of High-Quality Textile Structures. Polymers 2025, 17, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhan, H.; Singhal, N.; Vashistha, P.; Jain, R.; Bist, Y.; Gaur, A.; Wagri, N.K. Starch–Biomacromolecule Complexes: A Comprehensive Review of Interactions, Functional Materials, and Applications in Food, Pharma, and Packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 11, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Biswas, S.K.; Han, J.; Tanpichai, S.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Das, A.K.; Yano, H. Surface and Interface Engineering for Nanocellulosic Advanced Materials. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2002264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Solé, A. A Systematic Review on Enzymatic Refining of Recycled Fibers: A Potential to be Unlocked. BioResources 2025, 20, 7870–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-G.; Choi, H.Y.; Shin, S.-J. Impact of Cellulases Treatment on Pulp Surface and Chemical Composition. J. Korea TAPPI 2024, 56, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagl, M.; Haske-Cornelius, O.; Bauer, W.; Nyanhongo, G.S.; Guebitz, G.M. Enhanced energy savings in enzymatic refining of hardwood and softwood pulp. Energ. Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, N.; Smith, M.M.; Venditti, R.A.; Pal, L. Enzyme-Assisted Dewatering and Strength Enhancement of Cellulosic Fibers for Sustainable Papermaking: A Bench and Pilot Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Van, H.; Kafy, A.; Zhai, L.; Kim, J.W.; Mwongwli, R.; Kim, J. Fabrication and Characterization of Cellulose Nanofibers from Recycled and Native Cellulose Resources Using TEMPO Oxidation. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2018, 52, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.W.; Muchlis, A.M.G.; Devi, R.K.; Cai, D.-L.; Chen, S.-P.; Lee, C.-C.; Huang, K.-Y.; Martinka, M.; Lin, C.C. Biodegradable Composite Material by Silane-Modified Pineapple Leaf Fiber with High Flexibility and Degradation Rate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 9728–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, M.; Reynoso, S.; Rambhia, S.; Noki, G.; Olson, J.; Stoeber, B.; Trajano, H.L. Effect of Incubation Conditions of Cellulase Hydrolysis on Mechanical Pulp Fibre Morphology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Whiteside, W.S.; Kajla, P.; Tavassoli, M. Value Addition of Rice Straw Cellulose Fibers as a Reinforcer in Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 125320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellman, F.A.; Benselfelt, T.; Larsson, P.T.; Wågberg, L. Hornification of Cellulose-Rich Materials—A Kinetically Trapped State. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 318, 121132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Soria, R.; Walton, D.J.; D’Aì, A.; Pintore, F.; Kosec, P.; Alston, W.N.; Fuerst, F.; Middleton, M.J.; Roberts, T.P.; et al. XMM Newton Campaign on the Ultraluminous X-Ray Source NGC 247 ULX-1: Outflows. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 505, 5058–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtović, D.; Zivković, P.; Milivojević, A.; Bezbradica, D.; Band, D.; Van Der Auwera, L. Reduction of Fines in Recycled Paper White Water via Cellulase Enzymes. Bioresources 2024, 19, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, M.-C.; Tanasă, F.; Teacă, C.-A. Crystallinity Changes in Modified Cellulose Substrates Evidenced by Spectral and X-Ray Diffraction Data. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z. Application of Colloidal Chemistry and Polymer Chemistry in Papermaking Industry. Am. J. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2022, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Sjöstrand, B. Hornification of Softwood and Hardwood Pulps Correlating with a Decrease in Accessible Surfaces. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 26164−26171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Feng, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, X. The Stability of Four Kinds of Cellulose Pickering Emulsions and Optimization of the Properties of Mayonnaise by a Soybean Byproduct Pickering Emulsion. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fan, G.; He, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Zhang, L. Diatomite Modified with an Alkyl Ketene Dimer for Hydrophobicity of Cellulosic Paper. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20129–20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Fabià, S.; Torstensen, J.; Johansson, L.; Syverud, K. Hydrophobisation of Lignocellulosic Materials Part I: Physical Modification. Cellulose 2022, 29, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilovic, T.; Despotovic, V.; Zot, M.-I.; Trumic, M.S. Prediction of Flotation Deinking Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuňa, V.; Balberčák, J.; Boháček, S.; Ihnát, V. Elimination of Adhesive Impurities of the Recovered Paper in Flotation Process. Wood Res. 2021, 66, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Reyes Ladino, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Cationic Modification of Cellulose as a Sustainable and Recyclable Adsorbent for Anionic Dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, J.; Bastidas, J.C.; Jameel, H.; Gonzalez, R. Understanding Sizing Conditions with Alkenyl Succinic Anhydride: Experimental Analysis of pH and Anionic Trash Catcher Effects on Softwood Kraft Pulp. BioResources 2025, 20, 4378–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.; Sithole, B. Stickies. Monitoring for Improved Paper Recycling Efficiencies. Int. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 19. Available online: https://www.tsijournals.com/articles/stickies-monitoring-for-improved-paper-recycling-efficiencies.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Park, M.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Park, H.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, J.-S. Optimizing Fiber Quality in Recycled Old Corrugated Containers (OCC) Using Ultra-Fine Bar Plate Technology. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzel, F.; Tassi, E.L.; Rosellini, I.; Marouani, E.; Khouaja, A.; Koubaa, A. Evaluating the Properties of Deinking Paper Sludge from the Mediterranean Area for Recycling in Local Areas as a Soil Amendment and to Enhance Growth Substrates. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgmayr, S.; Tanner, J.; Batchelor, W.; Hoadley, A.F.A. CaCO3 Solubility in the Process Water of Recycled Containerboard Mills. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2022, 38, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, A.; Fischer, J.; Bakhshi, A.; Bauer, W.; Fischer, S.; Spirk, S. Fusion of Cellulose Microspheres with Pulp Fibers: Creating an Unconventional Type of Paper. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 338, 122207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushakov, A.; Alashkevich, Y.; Kozhukhov, V.; Marchenko, R. Role of External Fibrillation in High-Consistency Pulp Refining. BioResources 2023, 18, 5494–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, N.; Gonzalez, M.; Venditti, R.; Pal, R. Synergistic Cell-Free Enzyme Cocktails for Enhanced Fiber Matrix Development: Improving Dewatering, Strength, and Decarbonization in the Paper Industry. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çiçekler, M.; Sözbir, T.; Tutuş, A. Improving the Optical Properties and Filler Content of White Top Testliners by Using a Size Press. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 21000–21007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, R.J.; McDonald, J.D.; Meltzer, F.P. External fibrillation of wood pulp. TAPPI J. 2023, 22, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangel, A., III; Robles, D.; Atzen, J.; Song, X. Recycling Contaminated Wastepaper using Composite-Based Additive Manufacturing. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 297, 112346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Itkor, P.; Lee, Y.S. State-of-the-Art Insights and Potential Applications of Cellulose-Based Hydrogels in Food Packaging: Advances towards Sustainable Trends. Gels 2023, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, A.; Nicastro, G.; Riva, L.; Sacchetti, A.; Ghirardello, D.; Punta, C. Cellulose Nanofibers for Grease and Air Barrier Properties Enhancement: A Comparison on Recycled and Food Contact Paper Samples. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, F.s.M.; Rasouli, S. Recycling Kaolin from Paper Waste and Assessment of its Application for Paper Coating. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 39, 109142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Fereidooni, L.; Morais, A.R.C.; Shiflett, M.B.; Hubbe, M.A.; Venditti, R.A. Valorization of Food Processing Waste: Utilization of Pistachio Shell as a Renewable Papermaking Filler for Paperboard. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 118810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Mo, W.; Zhang, F.; Houtman, C.J.; Wan, J.; Li, B. Surface Modification of Adsorbents for Removing Microstickies from Papermaking Whitewater. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 7950–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.H.; Seo, Y.B.; Han, J.S. Producing Flexible Calcium Carbonate from Waste Paper and their Use as Fillers for High Bulk Paper. BioResources 2023, 18, 3400–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadian, H.; Ceccherini, S.; Sharifi Zamani, E.; Phiri, J.; Maloney, T. Production of Low-Density and High-Strength Paperboards by Controlled Micro-Nano Fibrillation of Fibers. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 17126–17137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Loor, A.; Walger, E.; Mortha, G.; Marlin, N. Oxidation of Fully Bleached Paper-Grade Kraft Pulps with H2O2 Activated by Cu(Phen) and the Effect of the Final pH. BioResources 2023, 18, 5222–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastyanova, Y.; Shcherbak, N.; Konshina, K.; Potashev, A.; Palchikova, E.; Makarov, I.; Kalimanova, D.; Sakipova, L.; Kareshova, Z.; Balabekova, S.; et al. Study of the Change in Properties by Artificial Aging of Eco-Papers. Processes 2025, 13, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzer, F.; Manian, A.P.; Bechtold, T.; Pham, T. The Role of Carboxyl and Cationic Groups in Low-Level Cationised Cellulose Fibres Investigated by Zeta Potential and Sorption Studies. Cellulose 2024, 31, 8501–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelton, R.H.; Karami, A.; Moran-Mirabal, J. Analysis of Polydisperse Polymer Adsorption on Porous Cellulose Fibers. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2024, 39, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, N.A.; Garland, L.J.; Leib, B.D.; Hubbe, M.A. Mechanistic Aspects of Nanocellulose–Cationic Starch–Colloidal Silica Systems for Papermaking. TAPPI J. 2023, 22, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, M.; Salem, K.S.; Musten, E.; Lucian, L.; Hubbe, M.A.; Pal, L. Renovating Recycled Fibres Using High-Shear Homogenization for Sustainable Packaging and other Bioproducts. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2025, 38, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, M.; Patankar, S.C. Regioselective Oxidation of Recycled Cellulosic Fibres for Enhancement in the Mechanical Strength of Resulting Papers. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 102, 3416–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazega, A.; Lehrhöfer, A.; Aguado, R.J.; Potthast, A.; Marquez, R.; Rosenau, T. Key Insights into TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation of Cellulose: Influence of Starting Material. Cellulose 2025, 32, 5227–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Salvador, J.L.; Blanco, A.; Duque, A.; Negro, M.J.; Manzanares, P.; Negro, C. Upscaling Cellulose Oxidation: Integrating TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation in a Pilot-Plant Twin-Screw Extruder for Cellulose Nanofibril Production. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, L.; Marlin, N.; Mortha, G.; Boucher, J.; Lachenal, D. Periodate-chlorite oxidation for dicarboxylcellulose (DCC) production: Activation strategies for the dissolution and visualization of oxidized group distribution. Cellulose 2025, 32, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Ng, Z.Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; He, Y.; Wei, H.; Dang, L. Calcium Ion Deposition with Precipitated Calcium Carbonate: Influencing Factors and Mechanism Exploration. Processes 2024, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francolini, I.; Galantini, L.; Rea, F.; Di Cosimo, C.; Di Cosimo, P. PolymericWet-Strength Agents in the Paper Industry: An Overview of Mechanisms and Current Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sanchez-Salvador, J.L.; Blanco, A.; Balea, A.; Negro, C. Recycling of TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation Medium and its Effect on Nanocellulose Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 319, 121168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo Stampino, P.; Riva, L.; Caruso, M.; Rahman, I.A.; Elegir, G.; Bussini, D.; Marti-Rujas, J.; Dotelli, G.; Punta, C. Can TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers Be Used as Additives in Bio-Based Building Materials? A Preliminary Study on Earth Plasters. Materials 2023, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, A.P.; Sharma, P.; Capalash, N. Use of Laccase in Pulp and Paper Industry. Biotechnol. Prog. 2012, 28, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdoch, W.; Cao, Z.; Florczak, P.; Markiewicz, R.; Jarek, M.; Olejnik, K.; Mazela, B. Influence of Nanocellulose Structure on Paper Reinforcement. Molecules 2022, 27, 4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehman, N.V.; Aguerre, Y.S.; Vallejos, M.E.; Felissia, F.E.; Area, M.C. Nanocellulose addition to recycled pulps in two scenarios emulating industrial processes for the production of paperboard. Maderas. Cienc. Tecnol. 2023, 25, e3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipeni, A.R.H.; Tan, J.W.; Shah, N.J.; Amin, K.N.M. Effect of Nanocellulose Reinforced Recycled Paper Towards Tensile Strength. J. Chem. Eng. Ind. Biotechnol. 2024, 10, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balea, A.; Monte, M.C.; Fuente, E.; Sanchez-Salvador, J.L.; Tarrés, Q.; Mutjé, P.; Delgado-Aguilar, M.; Negro, C. Fit-for-Use Nanofibrillated Cellulose from Recovered Paper. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebreiros, F.; Seiler, S.; Dalli, S.S.; Lareo, C.; Saddler, J. Enhancing Cellulose Nanofibrillation of Eucalyptus Kraft Pulp by Combining Enzymatic and Mechanical Pretreatments. Cellulose 2021, 28, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa Sadr, A.; Maraghechi, S.; Suiker, A.S.J.; Bosco, E. Chemo-Mechanical Ageing of Paper: Effect of Acidity, Moisture and Micro-Structural Features. Cellulose 2024, 31, 6923–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-S.; Sung, Y.J. Changes in Fold Cracking Properties and Mechanical Properties of High-Grammage Paper as Affected by Additive and Fillers. BioResources 2023, 18, 3217–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioritti, R.R.; Revilla, E.; Villar, J.C.; D’Almeida, M.L.O.; Gómez, N. Improving the Strength of Recycled Liner for Corrugated Packaging by Adding Virgin Fibres: Effect of Refrigerated Storage on Paper Properties. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2021, 34, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczulski, M.; Szewczyk, W.; Kuczkowski, M. Possibilities of Reducing the Heat Energy Consumption in a Tissue Paper Machine—Case Study. Energies 2023, 16, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keresztes, J.; Csóka, L. Characterisation of the Surface Free Energy of the Recycled Cellulose Layer that Comprises the Middle Component of Corrugated Paperboards. Coatings 2023, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukoje, M.; Bolanca Mirkovic, I.; Bolanca, Z. Influence of Printing Technique and Printing Conditions on Prints Recycling Efficiency and Effluents Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, S.; Swati, S.; Kecheng, L.; Abdus, S.; Fleming, P.D.; Pekarovicova, A.; Wu, Q. Effect of Progressive Deinking and Reprinting on Inkjet-Printed Paper. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2023, 38, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitbauer, J.; Machado Charry, E.; Eckhart, R.; Sözeri, C.; Bauer, W. Bulk Characterization of Highly Structured Tissue Paper based on 2D and 3D Evaluation Methods. Cellulose 2023, 30, 7923–7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; van Ewijk, S.; Kanaoka, K.S.; Alamerew, Y.A.; Lin, H.; Cao, Z. Sustainability Assessment and Pathways for U.S. Domestic Paper Recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 199, 107249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiewak, R.; Vankayalapati, G.S.; Considine, J.M.; Turner, K.T.; Purohit, P.K. Humidity Dependence of Fracture Toughness of Cellulose Fibrous Networks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 264, 108330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbowski, T.; Knitter-Piatkowska, A.; Winiarski, P. Simplified Modelling of the Edge Crush Resistance of Multi-Layered Corrugated Board: Experimental and Computational Study. Materials 2023, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, S.; Moreira, M.T.; Artal, G.; Maldonado, L.; Feijoo, G. Environmental Impact Assessment of Non-Wood Based Pulp Production by Soda-Anthraquinone Pulping Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.; Wenzel, H. Paper Waste—Recycling, Incineration or Landfilling? A Review of Existing Life Cycle Assessments. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, S29–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simamora, J.; Wiloso, E.I.; Yani, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Paper Products Based on Recycled and Virgin Fiber. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2023, 9, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pulansari, F.; Nugraha, I.; Saputro, E.A. A Desk Study Based on SWOT Analysis: An Adaptation of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in the Pulp and Paper Industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2022, 372, 05005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yin, L.; Wang, R.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, K. Sustainable Utilization of Pulp and Paper Wastewater. Water 2023, 15, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Wastes—Resource Conservation—Common Wastes & Materials—Paper Recycling; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/wastes/conserve/materials/paper/web/html/index-2.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ketkale, H.; Simske, S. A Life Cycle Analysis and Economic Cost Analysis of Corrugated Cardboard Box Reuse and Recycling in the United States. Resources 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batouta, K.I.; Aouhassi, S.; Mansouri, K. Energy Saving Potential in Steam Systems: A Techno-Economic Analysis of a Recycling Pulp and Paper Mill Industry in Morocco. Sci. Afr. 2024, 26, e02375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calanter, P.; Drăgoi, A.-E.; Gramaticu, M.; Dumitrescu, A.; Taranu, M.; Gudanescu, N.; Alina-Cerasela, A. Circular Economy and Job Creation: A Comparative Approach in an Emerging European Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, J.A.; D’Adamo, I.; Wamba, S.F.; Gastaldi, M. Competitiveness and Sustainability in the Paper Industry: The Valorisation of Human Resources as an Enabling Factor. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Malyan, S.K.; Apollon, W.; Verma, P. Valorization of Pulp and Paper Industry Waste Streams into Bioenergy and Value-Added Products: An Integrated Biorefinery Approach. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsch, L.; Breslmayer, G.; Lederer, J. Quantity and Quality f Paper-Based Packaging in Mixed MSW and Separate Paper Collection—A Case Study from Vienna, Austria. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.; Nan, Q.; Chi, W.; Qin, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhu, W.; Wu, W. Recycling Packaging Waste from Residual Waste Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Griffiths, S.; Bazilian, M.; Kim, J.; Foley, A.M.; Rooney, D. Decarbonizing the Pulp and Paper Industry: A Critical and Systematic Review of Socio-Technical Developments and Policy Options. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Panzarasa, G.; Burgert, I. Sustainability in Wood Products: A New Perspective for Handling Natural Diversity. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 1889–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.; Calvez, I.; Koubaa, A.; Landry, V.; Cloutier, A. Sustainability, Circularity, and Innovation in Wood-based Panel Manufacturing in the 2020s: Opportunities and Challenges. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardis, M.; Ferrara, C.; Cantoni, B.; Di Marcantonio, C.; De Feo, G.; Goi, D. How to choose the Best Tertiary Treatment for Pulp and Paper Wastewater? Life Cycle Assessment and Economic Analysis as Guidance Tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaggio, A.L.; Smith, G.; de Kreuk, M.K.; Lindeboom, R.E.F. Application of a Simplified Model for Assessing Particle Removal in Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) Systems: Experimental Verification at Laboratory and Full-Scale Level. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, E.; Kersten, A.; Schabel, S.; Kerpen, J. Microplastics in German Paper Mills’ Wastewater and Process Water Treatment Plants: Investigation of Sources, Removal Rates, and Emissions. Water Res. 2025, 271, 123016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, A.-M.; Blasenbauer, D.; Stipanovic, H.; Koinig, G.; Tischberger-Aldrian, A.; Lederer, J. Technical Evaluation and Recycling Potential of Polyolefin and Paper Separation in Mixed Waste Material Recovery Facilities. Recycling 2025, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Guastaferro, M.; Vaccari, M.; Annunzi, F.; Faè, M.; Tognotti, L.; Nicolella, C. From Pulper Rejects to Paper Mill Resources through Double-Stage Thermal Pyrolysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter/Feature | Description of Change During Recycling | Effect on Fiber Properties | Impact on Paper Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber length | Progressive shortening due to mechanical cutting during pulping and refining. | Reduced fiber–fiber contact area; lower bonding potential. | Decreased tensile and tear strength; need for virgin fiber blending. |

| Fiber width and cross-section | Collapse of cell wall and lumen; irregular cross-sectional shape. | Reduced flexibility and swelling capacity. | Lower bonding and sheet density; poor surface smoothness. |

| Hornification | Irreversible hydrogen bonding during drying leading to wall stiffening. | Loss of swelling ability and rehydration potential. | Reduced tensile strength and poor rewetting behavior. |

| External fibrillation | Loss of surface fibrils due to repeated refining and washing. | Smoother surface, reduced bonding sites. | Decreased fiber bonding and sheet strength. |

| Internal fibrillation | Reduced delamination between cell wall layers. | Limited flexibility and swelling. | Weaker fiber bonding, poorer formation. |

| Fines content | Accumulation of small fiber fragments and cell wall debris. | Increased density but reduced drainage. | Higher smoothness but lower bulk and tear strength. |

| Fiber curl and kink | Increase in fiber distortions with repeated mechanical treatment. | Reduced conformability and orientation in the sheet. | Lower tensile strength, but higher bulk and softness. |

| Surface roughness | Smoothing of fiber surface due to fibril loss. | Reduced surface area and reactivity. | Lower bonding efficiency and coating adhesion. |

| Crystallinity | Increase in crystalline regions due to drying and hornification. | Higher stiffness, lower water absorption. | Reduced flexibility and bonding potential. |

| Fines and ash accumulation | Retention of inorganic fillers and fines in recycled pulp. | Altered fiber chemistry and zeta potential. | Affects drainage, strength, and optical properties. |

| Recycling Stage/ Condition | Degree of Polymerization (DP) | Water Retention Value (WRV) | Freeness (CSF)/Drainage | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin/never-dried pulp | Highest DP; cellulose chains largely intact with minimal hydrolysis or oxidative damage. | High WRV, reflecting fully developed swelling capacity and accessible internal pore structure. | Baseline freeness determined by initial refining; used as reference for subsequent recycling behavior. | [82,92] |

| After first drying/first recycling cycle (no special treatment) | Pronounced initial decrease in DP compared with virgin pulp; largest relative drop often observed between cycle 0 and cycle 1. | Marked decrease in WRV due to hornification and partial collapse of the pore structure; reduced swelling and flexibility. | In many chemical pulps with fines retained, freeness tends to drop (slower drainage) mainly at the first cycle; in systems with fines loss, freeness can increase. | [93,94] |

| 2–3 recycling cycles (no special treatment) | Further DP decrease, but the rate of decline is generally lower than in the first cycle; values begin to approach a plateau influenced by fiber origin and prior aging. | WRV continues to decline with each drying/recycling event, then tends toward a lower steady state; loss of hemicelluloses and increased crystallinity are commonly reported. | Reported trends depend on pulp type and system closure; some studies show continued freeness drop with fines accumulation, others report stabilization or slight increase when fines are lost. | [93,95] |

| ≥4–5 recycling cycles (no special treatment) | Gradual, smaller DP decreases; molecular weight distribution increasingly influenced by oxidative history and prior thermal/chemical exposure rather than the number of cycles alone. | WRV typically remains at a relatively low level; hornification is largely developed and additional recycling induces only limited further changes in swelling. | Freeness behavior strongly process-dependent; in many laboratory studies further changes are modest, but in closed industrial systems fines management and additional refining can dominate drainage trends. | [92,93,96] |

| Recycled fibers with mitigating treatments (e.g., chemical swelling, refining, or enzymatic/chemical re-swelling) | DP can be maintained or only moderately reduced if oxidative severity is controlled; some treatments intentionally trade slight DP loss for improved bonding. | WRV can partially recover or even increase relative to untreated recycled pulp due to re-swelling, increased charge, or enhanced fibrillation. | Refining-based strategies typically reduce freeness (slower drainage) because of increased fibrillation and fines content; chemical/enzymatic swelling without intensive refining has a milder impact on drainage. | [48,94,97] |

| Strategy/System | Representative Mechanism | Observed Effects (Qualitative) | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNF/nanocellulose from recycled or waste fibers | TEMPO-mediated or other oxidation followed by mechanical fibrillation of recycled or waste-paper pulps | CNF from recycled paper or waste fibers shows morphology and properties comparable to CNF from virgin fibers; used as wet-end additive or in fiber blends, it improves tensile strength and stiffness of recycled-paper-based materials | [50,65,109] |

| Dual CNF systems (anionic + cationic) in recycled paper | Cationization of CNF and combination with enzymatically produced anionic micro/nanofibers | Fully cellulose-based dual CNF system acts as both strength and retention aid; breaking length of recycled paper increased by ≈46.5%, outperforming synthetic polyacrylamide | [65] |

| Bio-based polymer and polysaccharide functionalization of recycled fibers | Use of chitosan, CMC, starch and other biodegradable polymers as strengthening agents and cross-linkers | Significant improvement of tensile properties and dimensional stability in recycled-fiber-based materials (shown for cotton recycled fibers) | [102] |

| Surface modification of pulps from mixed waste papers | Deinking and surface treatments applied to mixed waste corrugated carton and office paper pulps | Changes in surface chemistry, charge and roughness documented; basis for targeted surface functionalization and improved compatibility with additives | [86] |

| Silane-based cellulose modification (composites context) | Formation of siloxane bonds between functionalized silanes and cellulose hydroxyl groups | Improved interfacial adhesion, hydrophobicity and mechanical properties in cellulose-based composites | [110] |

| Enzymatic refining of recycled fibers | Use of cellulases and hemicellulases as refining aids | Energy savings up to ≈20% and improved bonding and drainage when enzymatic refining complements mechanical refining | [105,107] |

| Cellulase/cellulase–xylanase pretreatment | Selective modification of fiber surface and hemicellulose content | Increased external fibrillation and WRV; altered surface composition; potential enhancement of flexibility and bonding | [111] |

| Laccase/laccase–mediator systems on recycled pulps | Oxidative modification and partial delignification of fiber surfaces | Improved fiber-bonding capacity, tensile and compressive strengths of unbleached recycled pulps | [86,112] |

| Category | Typical Components | Chemical Effects on Fibers | Management and Control Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sizing agents | Alkyl ketene dimer (AKD), Alkenyl succinic anhydride (ASA), Rosin size | React with cellulose hydroxyl groups forming hydrophobic ester bonds; uneven distribution causes hydrophobic patches; reduces fiber wettability and bonding potential. | Optimize pH and temperature during recycling; use mild oxidative or enzymatic treatments to remove residual hydrophobes; employ retention aids for uniform dispersion. |

| Fillers and coating pigments | Calcium carbonate (CaCO3), Kaolin (Al2Si2O5(OH)4), Titanium dioxide (TiO2) | Block hydrogen-bonding sites, reduce swelling, and increase anionic demand; enhance opacity and brightness but weaken tensile strength if excessive. | Balance filler content by grade; control pH to prevent CaCO3 dissolution; apply optimized retention and drainage aids; partial purge of mineral fines when necessary. |

| Retention and strength aids | Cationic starch, PAE resin, Polyacrylamides (PAMs), Bentonite, Colloidal silica | Improve flocculation and inter-fiber bonding; adsorption limited by hornification and DCS interference; high charge demand in recycled systems. | Use sequential addition (fixative → strength aid → microparticle); monitor cationic demand; adjust polymer dosage and mixing intensity. |

| Dissolved and colloidal substances (DCSs) | Degraded hemicelluloses, dispersants, surfactants, extractives, latex residues | Increase anionic charge, compete with cationic polymers, destabilize flocs; adsorb on fines and fibers, leading to stickies and deposit formation. | Employ fixatives (polyamines, PAC, alum); use DAF and washing to reduce DCSs; maintain balanced white-water chemistry. |

| Inks and pigments | Carbon black, Organic dyes, Metal oxide pigments, Binder polymers | Alter fiber surface energy and zeta potential; create hydrophobic regions that interfere with sizing and bonding; may cause brightness reduction. | Use optimized flotation and surfactant chemistry; peroxide bleaching for optical recovery; minimize ink fragmentation during pulping. |

| Stickies and adhesives | Latex, Polyvinyl acetate (PVA), Styrene–butadiene rubber (SBR), Hot-melt adhesives | Hydrophobic and pressure-sensitive materials deposit on fibers and equipment; disrupt hydrogen bonding and cause sheet defects. | Apply detackifiers (talc, bentonite, PAC); control temperature and pH to minimize tackiness; install fine screening to remove macro-stickies. |

| Coating binders and latex residues | SBR, PVA, Acrylic copolymers | Modify zeta potential and drainage; contribute to hydrophobic surface areas and non-uniform sizing response; generate oligomers during degradation. | Use enzymatic pre-treatment to hydrolyze residues; adjust retention programs to manage increased hydrophobicity; enhance washing stages. |

| Treatment Type | Representative Mechanism | Typical Strength Improvement Trend | Key Notes/ Conditions | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical modification (e.g., TEMPO, CMC grafting) | Increased surface carboxylation, enhanced swelling and charge balance, improved polymer adsorption | Moderate–high tensile and bonding gains when oxidation is controlled; improved internal bonding and sometimes tear strength | Performance depends on pulp type, oxidation severity, and degree of polymerization (DP) loss; over-oxidation can reduce strength or increase brittleness | [151,155,156,157] |

| Enzymatic treatment (e.g., cellulases, xylanases) | Selective hydrolysis of amorphous/hemicellulosic regions; fiber-wall loosening and external fibrillation | Low–moderate tensile gains; improved bonding, sometimes at reduced refining energy | Dosage-sensitive; best results when mild treatment is integrated with refining strategy; excessive hydrolysis may shorten fibers or weaken the sheet | [105,106,108] |

| Laccase-mediator or laccase-only systems | Selective lignin activation and phenolic crosslinking; increased surface charge and functional groups | Moderate strength improvements (tensile, burst, sometimes wet strength), particularly in lignin-containing or OCC furnishes | Effect strongly influenced by mediator type and pulp lignin content; brightness and kappa number may also change | [93,136,156] |

| Nanocellulose reinforcement (CNF/CNF from virgin or recycled pulp) | High-surface-area fibrils fill interfiber voids and create a nanoscale bonding network | High tensile-strength gains and improved stiffness at relatively low addition levels; often strongest reinforcement among the listed strategies | Drainage and dewatering become limiting at higher dosages; effect depends on nanocellulose type (CNF vs. CNC), fibril morphology and dispersion quality | [158,159,160,161] |

| Combined enzymatic–mechanical fibrillation | Enzyme-assisted loosening of the fiber wall that facilitates subsequent mechanical fibrillation | Moderate–high strength gains with reduced specific refining energy compared with purely mechanical routes | Synergistic effects when mild enzymatic pretreatment is followed by optimized mechanical refining; effectiveness depends on enzyme type and treatment time | [105,108,162] |

| Study (Year) | System Boundaries | Functional Unit | Key Findings/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [174] | Cradle-to-gate; EU kraft pulp mill and recycled pulp line | 1 ton paper | Recycling generally lowers energy use and GHG emissions; results sensitive to electricity mix and recycling rate. |

| [175] | Cradle-to-grave; packaging paper loop | 1 ton packaging paper | Recycled fibers reduce carbon footprint but may increase water impacts depending on deinking configuration. |

| [176] | Cradle-to-gate; Asian mixed-furnish mill | 1 ton newsprint | Deinking step dominates energy demand; recycled furnish beneficial unless low-quality waste increases rejects. |

| [177] | Consequential LCA; EU circular-economy scenario | 1 ton recovered fiber | Increasing recycling rate shifts burdens upstream; marginal benefits decrease after ~75% recovery. |

| [18,19] | EU industry-level LCA synthesis | Sector-wide | Recycling outperforms virgin production in GHGs; trade-offs exist in water use and effluent loads depending on water-loop closure. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pătrăucean-Patrașcu, C.-I.; Gavrilescu, D.-A.; Gavrilescu, M. Chemical Transformations and Papermaking Potential of Recycled Secondary Cellulose Fibers for Circular Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13034. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413034

Pătrăucean-Patrașcu C-I, Gavrilescu D-A, Gavrilescu M. Chemical Transformations and Papermaking Potential of Recycled Secondary Cellulose Fibers for Circular Sustainability. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13034. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413034

Chicago/Turabian StylePătrăucean-Patrașcu, Corina-Iuliana, Dan-Alexandru Gavrilescu, and Maria Gavrilescu. 2025. "Chemical Transformations and Papermaking Potential of Recycled Secondary Cellulose Fibers for Circular Sustainability" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13034. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413034

APA StylePătrăucean-Patrașcu, C.-I., Gavrilescu, D.-A., & Gavrilescu, M. (2025). Chemical Transformations and Papermaking Potential of Recycled Secondary Cellulose Fibers for Circular Sustainability. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13034. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413034