Aero-Structural Analysis and Dimensional Optimization of a Prototype Hybrid Wind–Photovoltaic Rotor with 12 Pivoting Flat Blades and a Peripheral Stiffening Ring

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Justification for Flat Blades

1.2. Multi-Fidelity Design Workflow

1.3. Stiffening via Peripheral Ring

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recommended Operational Parameters

- ω—angular velocity of the rotor [rad/s];

- D—rotor diameter [m];

- R—rotor radius [m];

- n—rotor rotational speed [rpm];

- V—wind speed [m/s].

- Vcut-in ≤ 3 m/s (with initially high β for torque);

- Vnominal = 5–6 m/s (typical average for reasonable sites);

- Vcut-out/storm = 20–25 m/s (feathering + brakes).

- Beam model:

- -

- without the stiffening ring, i.e., the blade acts as a cantilever beam, Equation (3):

- -

- with a stiffening ring, i.e., the blade is supported at both ends (double-supported beam—hub joint and ring joint), Equation (4):

- Load distribution q(r):

- Stress concentration at r = 0.2 m:

- Section torsion:

- Adhesive/PV cells:

- N—number of blades, —mean chord, R—rotor radius.

- ϕ—resulting flow angle (from wind + tangential speed);

- βopt—depends on TSR, airfoil profile, and (indirectly) on solidity.

2.2. Aerodynamic Modelling

- Active geometry: R = 1.5 m; Rhub = 0.2 m → effective blade length L ≈ 1.3 m.

- Blades: 12 units, geo twist = 0°, variable chord.

- Polars: set Cl(α), Cd(α) for flat plate (entered in “Polars_flat”).

- Default condition: V = 5 m/s, λ = 2.6, βcoll = 10°.

- Additional cases:

- -

- Cut-in: V = 3 m/s, λ ≈ 2.0, β ≈ 22°;

- -

- Extreme: V = 25 m/s, λ ≈ 0.8, β ≈ 80°.

- Radial BEM discretization:

- Power coefficient:

- Ptotal—mechanical shaft power;

- ρ—air density;

- Aeff—effective blade area (1);

- V—wind speed.

- 2.

- Radial integration (BEM)—for each radial section r:

2.3. Verification and Validation

2.4. Structural Analysis and Stiffening Ring Design

2.4.1. Adopted Structural Model

- Flat blade considered as a thin rectangular beam, mainly loaded in bending and shear, with minor torsion from qt.

- Support scenario:

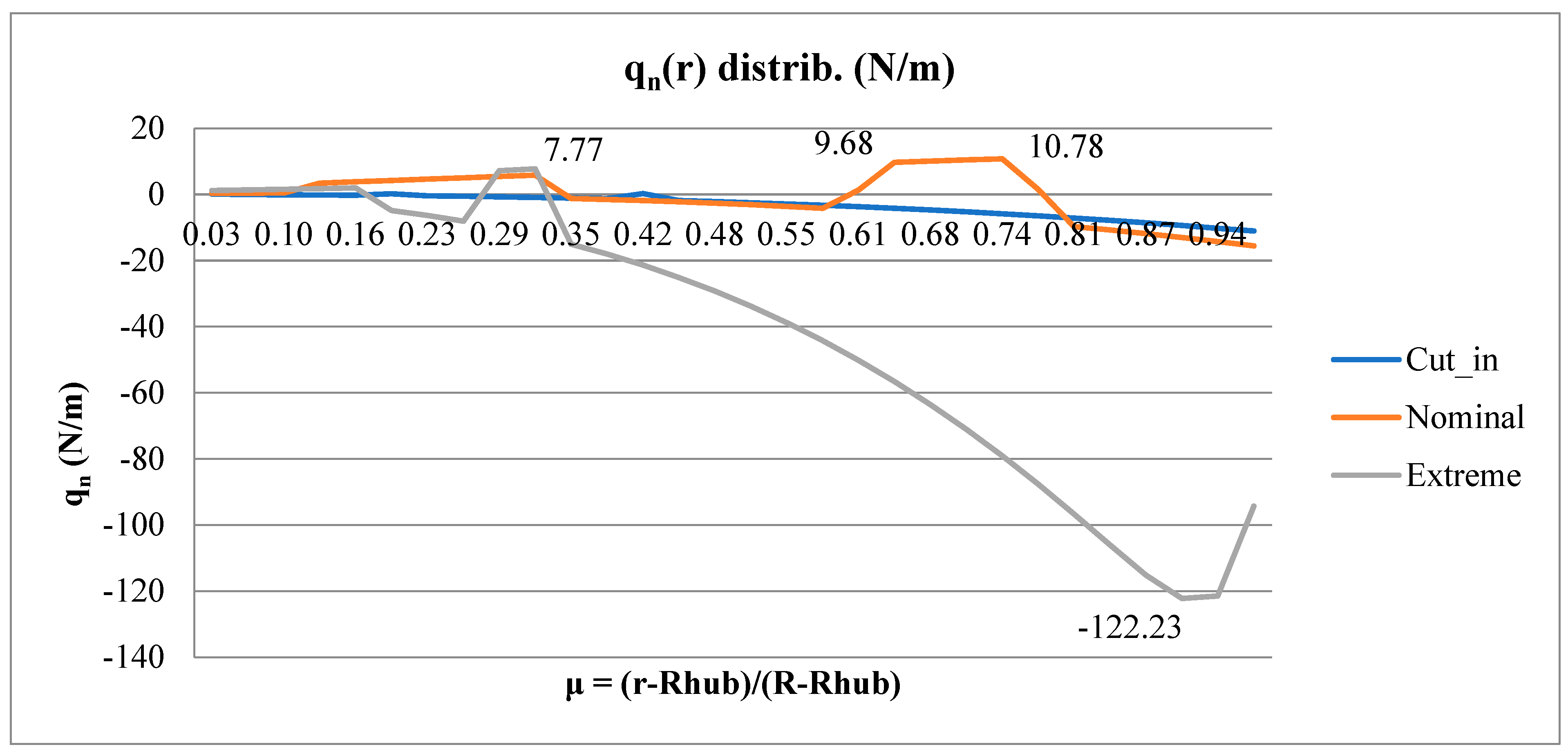

2.4.2. Load Cases (From BEM with Aerodynamic Input)

- Cut-in (V = 3 m/s, λ ≈ 2.0, β ≈ 22°)—low loads, but critical for starting (high local torque).

- Nominal (V = 5 m/s, λ ≈ 2.6, β ≈ 10°)—used for optimal Cp/operational sizing.

- Extreme (V = 20–25 m/s, β ≈ 80–90°)—blades feathered; qn decreases, but dynamic shocks and stresses appear in the ring/spokes.

- PV Park (β ≈ 0°, moderate wind)—flat disk, nearly uniform pressure; local check on PV adhesive.

- qn(r), qt(r) will be extracted and converted to pressures for FEM:

- Distributed loads will be applied on the blade and stiffening ring mesh.

2.4.3. Proposed Materials

- Flat blade: GFRP sandwich (PET core) for low cost; CFRP for minimum weight; 6061-T6 aluminum for rapid prototyping. Fatigue and UV resistance is critical for laminated wood.

- Ring and spokes: Aerodynamic aluminum tube or pultruded CFRP profile; parametric studies show that a ≈ 300 mm width and 15° spoke spacing ensure tip displacements < 1% of length [24].

2.4.4. Structural Analysis Method (FEM)

- Linear static—check σmax < σadm/SF (safety factor 1.5–2) and δtip < 1%·L;

- Local buckling—eigenmodes for flat panel with λcr > 2;

- Fatigue—106 cycles at real stress amplitudes using GFRP S–N curve (IEC 61400-2);

- Modal—first natural frequency f1 > 3·nrotor to avoid resonances.

2.4.5. Stiffening Ring Design

2.4.6. Validation Loop BEM → FEM → CFD

3. Results

3.1. Results of Aerodynamic Studies

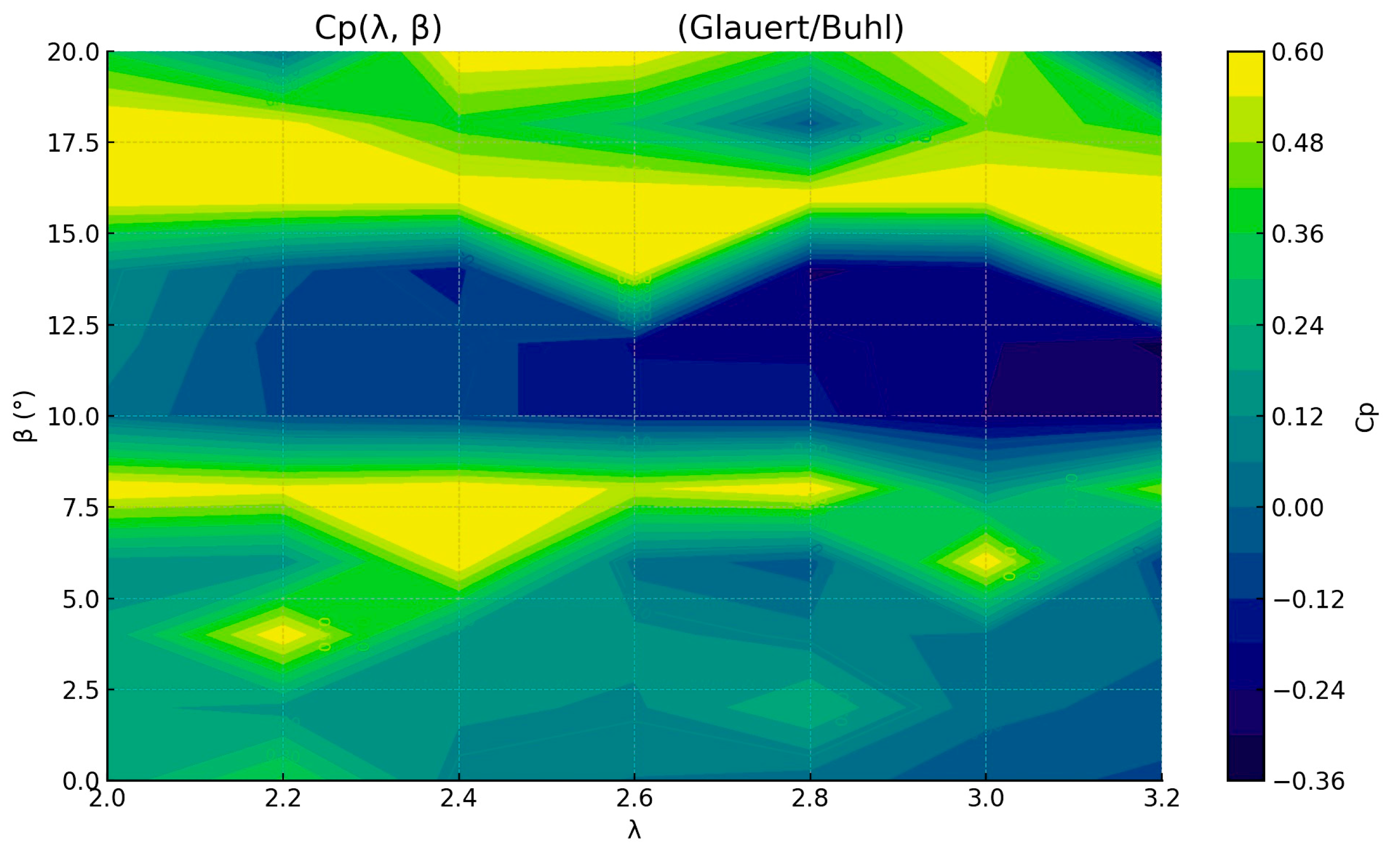

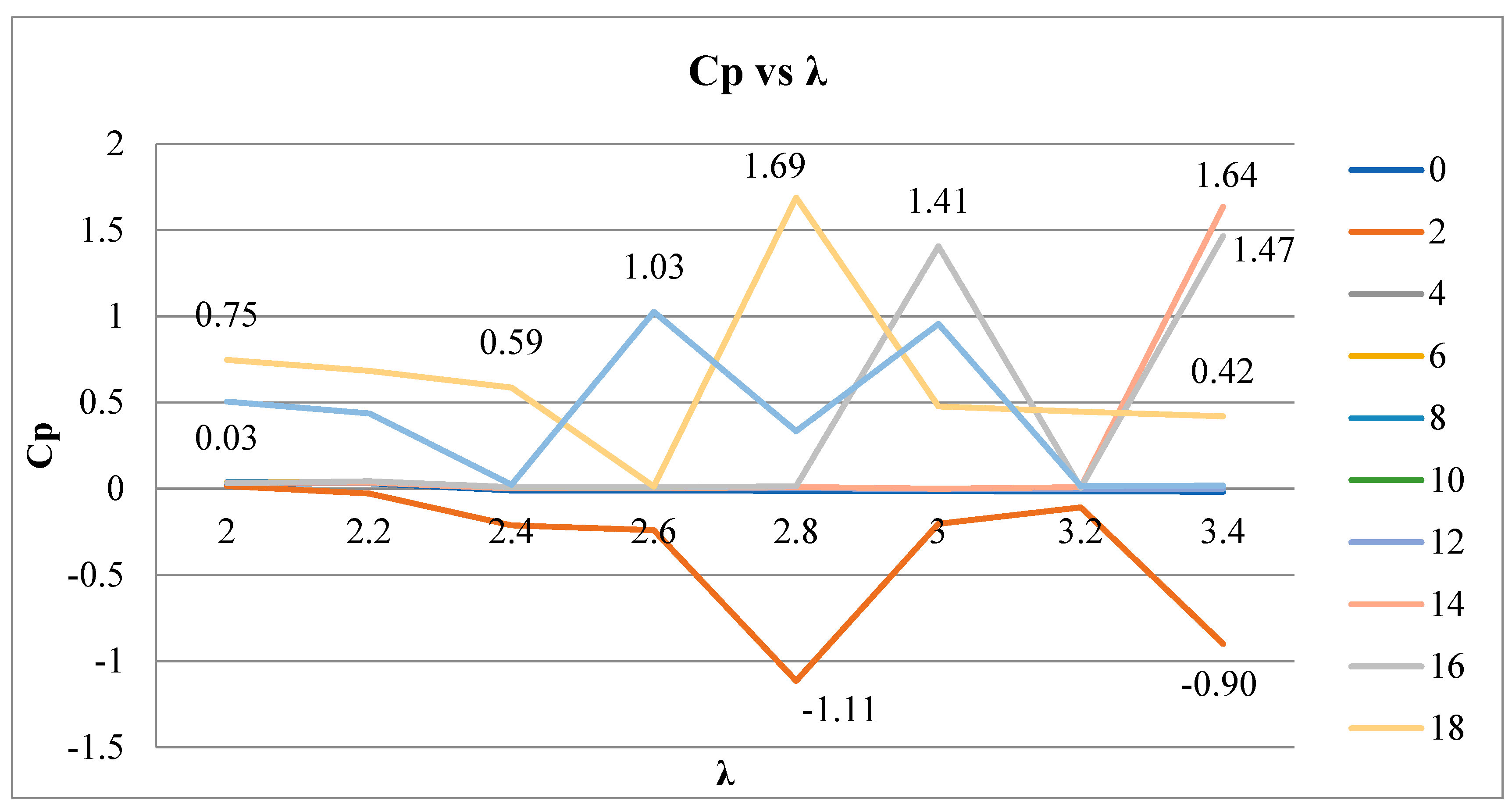

3.1.1. Cp(λ,β) Map

3.1.2. Radial Distributions

3.1.3. Power and Rotational Speed

3.2. Consolidation of Aerodynamic Loads for FEM − Flat Blade + Stiffening Ring

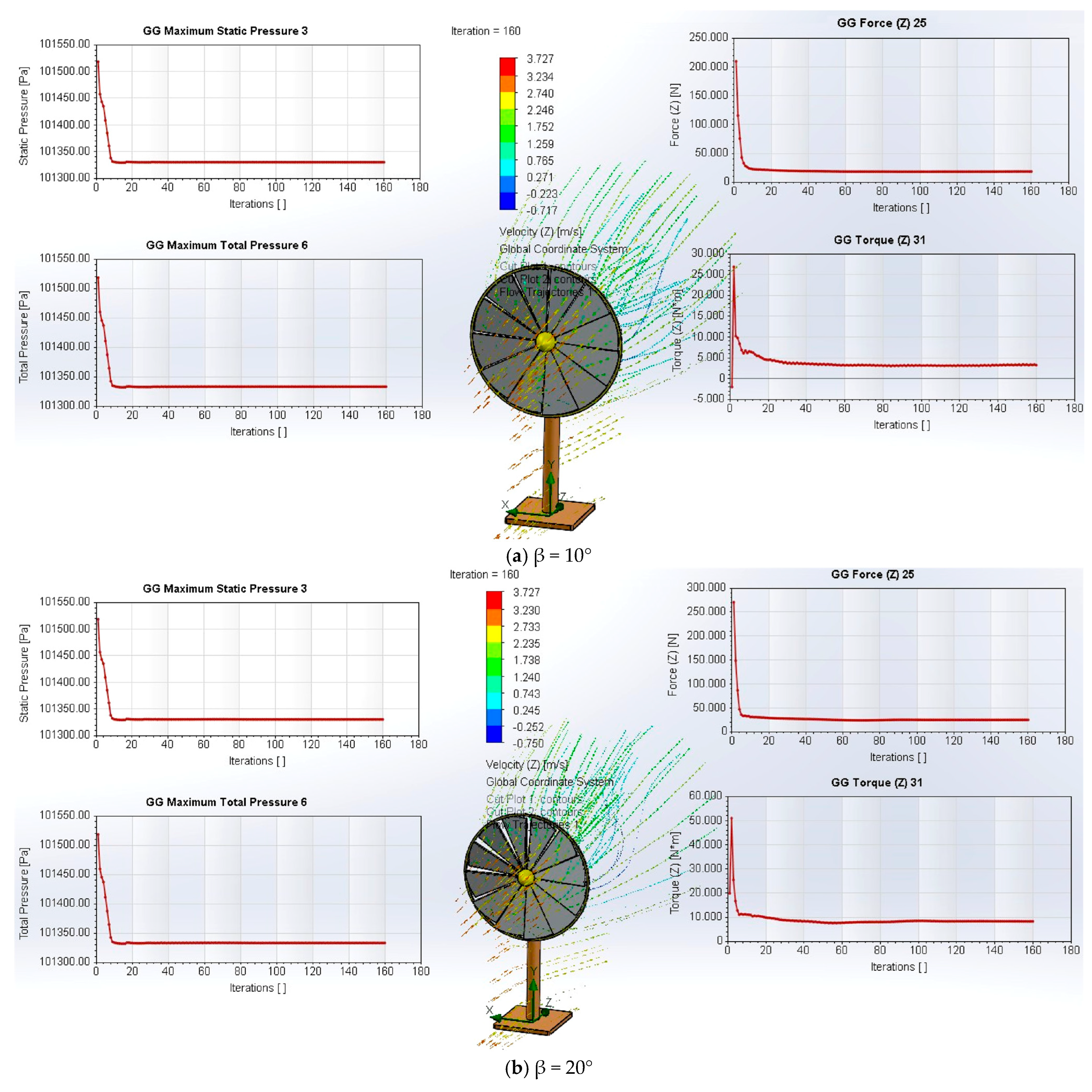

3.3. CFD Analysis

- Cut-in—V = 3 m/s, β = 10°, β = 20°

- At β = 0° (PV mode), air passes almost undisturbed through the rotor plane.

- At β = 10°, blades induce moderate deflection, with local downstream velocities reduced to ~1 m/s and a narrow wake.

- At β = 20°, flow deviation intensifies, producing a wider wake and local velocities below 0.5 m/s, directly correlating with the higher torque.

- β = 0° (PV mode) generates negligible torque,

- β = 10° produces minimal startup torque (~2.5 N·m),

- β = 20° yields sufficient torque (~9 N·m) for reliable self-start, while axial forces remain non-critical.

- β = 10° is validated as the nominal operating setting,

- At V = 5 m/s, β = 10°, the rotor operates efficiently at the nominal point, with ~60 N·m torque, low thrust (~50 N), and safe pressure levels.

- At V = 10 m/s, β = 20°, torque reaches ~100 N·m (~1.2 kW power), with moderate thrust (~350 N), attached flow, and structurally safe load levels.

- Axial thrust. Force (Z) stabilizes around ~600 N, far below the axial bearing limit (~15 kN), so no structural concern for thrust.

- Pressures. Maximum static/total pressures remain modest for this wind speed (order of kPa, well within FEM safety margins), scaling with ρV2 as expected for flat surfaces [13].

- Flow features. Velocity maps show strong lateral deflection of the incoming flow with no large recirculation behind the disc; with blades near-feathered, the wake is present but narrow and energy extraction is minimized.

- Axial thrust. Force (Z) < 1 kN, well within the bearing capacity and tower design limits.

- Pressures. Max pressure ≈ 9 kPa, still below the limits verified by FEM for the blade/ring assembly.

- Flow-field evidence (Figure 14).

- -

- The rotor becomes aerodynamically “invisible”: the disc appears only as a faint low-speed spot behind the nacelle while the freestream (≈25 m/s) bypasses the rotor almost undisturbed.

- -

- The wake is very narrow, with no significant recirculation, confirming the near-zero torque and the low axial load recorded by the goals.

- β = 80°: structurally acceptable thrust but residual torque ≈ 400 N·m → not sufficient for storm protection.

- β = 90°: torque effectively eliminated, thrust remains < 1 kN, and pressures are within FEM-validated margins → safe storm configuration.

- β = 0° for PV mode,

- β = 20° → 10° for startup and nominal operation,

- β = 90° for storm protection.

3.4. FEM Analysis

3.4.1. Single Blade Analysis

- Fixed/Fixed—both hub and ring fully constrained.

- Fixed/Hinge—hub side hinge, ring side fixed.

- Hinge/Hinge—both hub and ring hinge.

- Results and Interpretation

- Fixed/Fixed (Figure 16).Maximum von Mises stress ≈ 10 MPa, displacement ≈ 0.07 mm, and FOS ≈ 3. The blade remains very stiff, with tangential moment absorbed through the ring. Comparable low values (σ < 12 MPa, U < 0.1 mm) were reported in the literature for flat blades with dual welded hubs [27].

- Fixed/Hinge.Stress increases slightly (~11 MPa) while tip-side deformation grows to ~0.67 mm, confirming added torsional compliance, consistent with pivoting-blade tests (U ≈ 0.9 mm) [39].

- Hinge/Hinge (Figure 17).σvM,max ≈ 392.2 MPa at the upper shaft (blade–ring connection), exceeding Rp0.2 = 276 MPa for Al 6061-T6. Maximum displacement (≈16.8 mm) occurs in the lower pitch-arm lever, which is under-dimensioned. FOS falls to 0.70. These values are consistent with experimental data for feathered flat blades (σ ≈ 380–420 MPa, Utip ≈ 15 mm) [13]. Consequently, the pitch-arm lever will be redesigned in steel instead of aluminum.

- σvM,max ≈ 392 MPa at the upper shaft in the ring → exceeding Rp0.2 (onset of local yielding);

- URESmax ≈ 16.8 mm in the lower pitch-arm lever (global deflection);

- FOSmin ≈ 0.70 at the same critical node.

- torsional locking at least one pitch shaft (Fixed/Hinge or Fixed/Fixed),

- stiffening the lower pivot region,

- relocating the pitch drive internally,

- or adding an auxiliary radial support at μ ≈ 0.8.

- Elastic safety is ensured for Fixed/Fixed and Fixed/Hinge (σ ≲ 0.1·Rp0.2).

- Hinge/Hinge must be avoided: local yielding at the upper shaft in the ring and large global rotation governed by the lower pitch-arm lever.

- -

- torsional lock on at least one side (Fixed/Hinge or Fixed/Fixed);

- -

- redesign the pitch-arm lever in steel (current aluminum lever is too compliant);

- -

- local fillet/rib stiffening at the lower pivot, and an auxiliary radial support at μ ≈ 0.8 to redistribute moment.

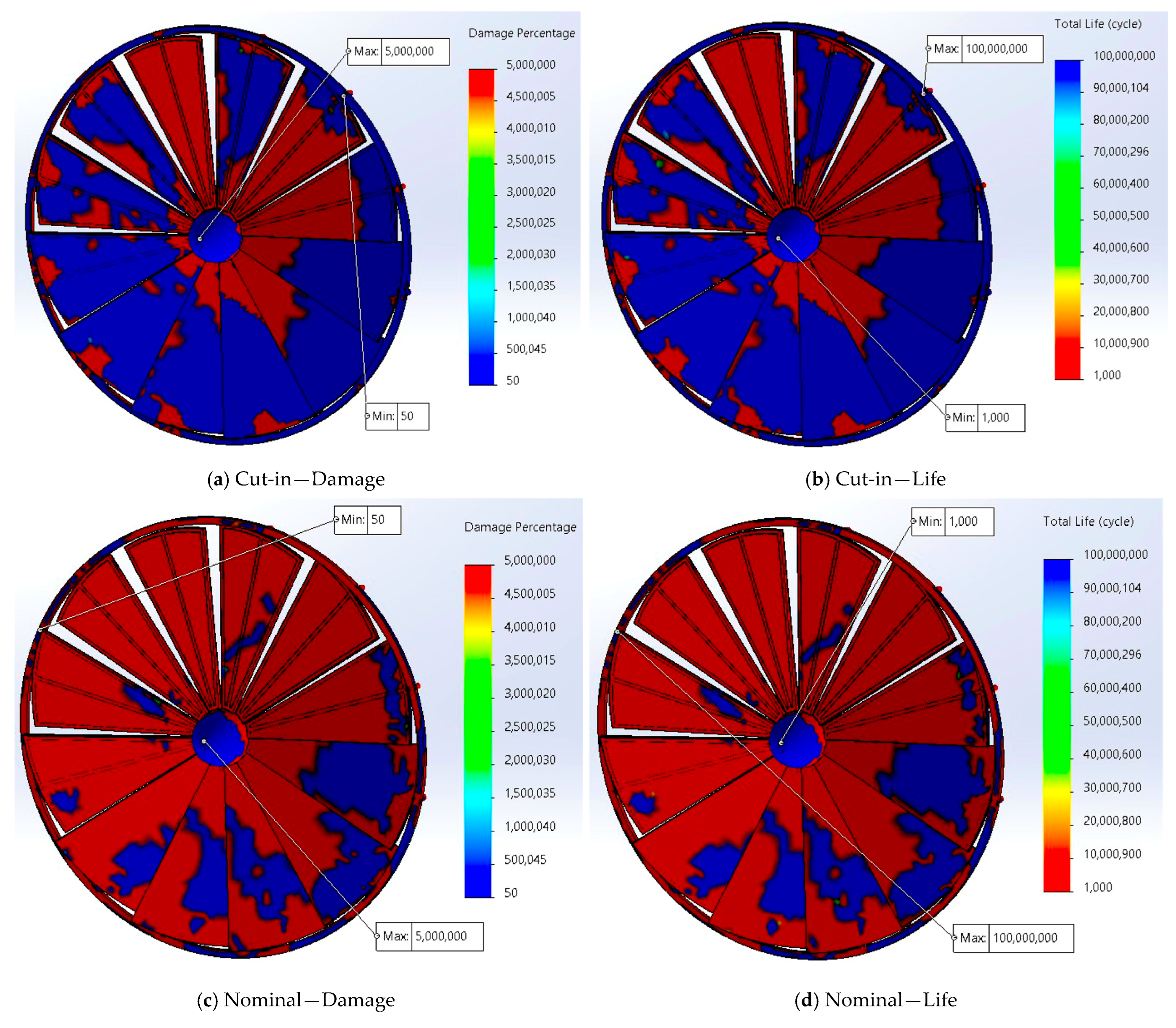

3.4.2. Blade Fatigue Analysis (S–N, Miner) and Life Maps

3.4.3. Full Blade Assembly Analysis

- β = 10° → σ ≈ 27 MPa, Utip ≈ 1.3 mm, FOS > 8;

- β = 20° → σ ≈ 50 MPa, Utip ≈ 2.9 mm, FOS > 5.

- operates in the elastic domain (σvM,max < 0.5·Rp0.2);

- shows deflections < 0.5%·R, well within IEC 61400-2 [10];

3.4.4. Fatigue Assessment of the 12-Blade/Ring Assembly (S–N/Miner) and Life Maps

4. Discussion

4.1. How the Results Fit into a Context with No Direct Precedent

- The aerodynamic penalty of flat blades (~−20% compared to airfoils) becomes acceptable if the pitch (β ≈ 10–20°) and moderate TSR (λ ≈ 2.6) are optimized;

- Peripheral stiffening can keep σ < 0.25·Rp0.2 even in 25 m/s gusts, without excessive mass (total weight increase +76%).

4.2. Technical and Market Implications

- Urban/peripheral applicability. The starting torque > 3 N·m at 3 m/s and nominal power ~0.6 kW at 5 m/s place this prototype in the SWT (≤10 kW) segment, suitable for rooftops or off-grid stations. The ring stiffener reduces noise levels by eliminating the free blade tip, meeting urban acoustic standards [33].

- Hybrid PV integration. At feathering (β = 90°), the rotor allows ~90% of solar irradiance to pass through—a key advantage for agrivoltaic configurations, where <15% shading is considered acceptable [40].

- Simplified control strategy. Simulations indicate only three critical pitch positions: 20° (self-start), 10° (nominal), and 90° (protection). This allows a mechanical stop + bevel gear mechanism, more reliable and cheaper than continuous servo systems.

4.3. Influence of the Stiffening Ring Mass and Inertia

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

- β ≈ 20° enables reliable self-start at 3 m·s−1;

- β ≈ 10° maximizes power at ~5 m·s−1 (Cp plateau ≈ 0.35 at λ = 2.4–2.8);

- β ≈ 90° reduces net torque to near-zero at 25 m·s−1, ensuring storm protection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| a, a′ | Axial and tangential induction factors |

| Aeff | Effective swept area |

| BC | Boundary condition |

| BEM/BEMT | Blade Element Momentum (Theory) |

| β | Blade pitch angle |

| CAISO | California Independent System Operator |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| Cl | Lift coefficient |

| Clmax | Maximum lift coefficient |

| Cd | Drag coefficient |

| Cp | Power coefficient |

| CFRP | Carbon-Fibre-Reinforced Polymer |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| EP | European Patent (e.g., EP 3736438 B1) |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FOS | Factor of Safety |

| GG | Global Goal (SolidWorks CFD output) |

| GFRP | Glass-Fibre-Reinforced Polymer |

| GMNIA | Geometrically & Materially Non-linear Imperfection Analysis |

| GW/MW/kW | Giga-/Mega-/Kilowatt |

| HAWC2 | Horizontal Axis Wind turbine Code 2 (aero-elastic solver) |

| HAWTs | Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbines |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| k-ω SST | k-omega Shear-Stress-Transport turbulence model |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| LSB | Laminar Separation Bubble |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| OpenFAST/ElastoDyn | Open-source aero-elastic code/structural module |

| PIV | Particle-Image Velocimetry |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| qn | Normal distributed blade load |

| qt | Tangential distributed blade load |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| RPM | Revolutions per minute |

| SF | Safety Factor |

| SWTs | Small Wind Turbines |

| TSR | Tip-Speed Ratio |

| URES | Resultant displacement (FEM post-processing) |

| UQ | Uncertainty Quantification |

| VRE | Variable Renewable Energy |

| WEC | Wind Energy Conversion |

| σvM | von Mises stress |

| ω | Angular velocity (rad s−1) |

References

- International Energy Agency. Renewables 2024: Analysis and Forecasts to 2030; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gorman, W.; Rand, J.; Manderlink, N.; Cheyette, A.; Bolinger, M.; Seel, J.; Jeong, S.; Wiser, R.H. Hybrid Power Plants: Status of Operating and Proposed Plants, 2024 Edition; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://emp.lbl.gov/hybrid-power-plants-status-operating-and-proposed-plants-2024-edition (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Hassan, Q.; Algburi, S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A Review of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems: Solar and Wind-Powered Solutions: Challenges, Opportunities, and Policy Implications. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaimi, F.B.I.; Kazem, H.A.; Alzakri, A.B.; Alatir, A.M. Design and Implementation of Smart Integrated Hybrid Solar-Darrieus Wind Turbine System for In-House Power Generation. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2024, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 24th International Wind & Solar Integration Workshop 2025—Preliminary Program. Berlin, Germany, 7–10 October 2025. Available online: https://windintegrationworkshop.org/program-overview-preliminary/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), Government of India. Amendment in the Guidelines for Tariff-Based Competitive Bidding Process for Procurement of Power from Grid-Connected Wind–Solar Hybrid Projects; MNRE: New Delhi, India, 2022. Available online: https://mnre.gov.in/en/notices/amendment-in-the-guidelines-for-tariff-based-competitive-bidding-process-for-procurement-of-power-from-grid-connected-wind-solar-hybrid-projects (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Meister, R.; Yaïci, W.; Moezzi, R.; Gheibi, M.; Hovi, K.; Annuk, A. Evaluating the Balancing Properties of Wind and Solar Photovoltaic System Production. Energies 2025, 18, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Solar and Wind Power Curtailments Are Increasing in California. Today in Energy, 28 May 2025. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=65364 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Pelletier, A.; Mueller, T.J. Low Reynolds Number Aerodynamics of Low-Aspect-Ratio, Thin/Flat/Cambered-Plate Wings. J. Aircr. 2000, 37, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-2:2019; Wind Energy Generation Systems—Part 2: Small Wind Turbines. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Burton, T.; Jenkins, N.; Sharpe, D.; Bossanyi, E. Design Loads for HAWTs. In Wind Energy Handbook, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, K.; Schepers, J.G.; Madsen, H.A.; Pirrung, G.R.; Echeverri, D.; van Garrel, A.; Lutz, T.; Stoevesandt, B.; Rahimi, H.; Meister, R.; et al. Progress in the Validation of Rotor Aerodynamic Codes Using Field Data. Wind Energy Sci. 2023, 8, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIAA. Guide for the Verification and Validation of Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations. AIAA G-077-1998 (Reaffirmed 2002); American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Kulkarni, V. Monitoring the Wake of Low Reynolds Number Airfoils for Their Aerodynamic Loads Assessment. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2024, 17, 2481–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, L.W. Wing Efficiency Enhancement at Low Reynolds Number. Aerospace 2024, 11, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Castillo, P.; Aguilar-Cabello, J.; Alcalde-Morales, S.; Parras, L.; del Pino, C. On the lift curve slope for rectangular flat plate wings at moderate Reynolds number. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 208, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahle, F.; Li, A.; Lønbæk, K.; Sørensen, N.N.; Riva, R. Multi-fidelity, steady-state aeroelastic modelling of a 22-megawatt wind turbine. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2767, 022065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribnitzky, D.; Berger, F.; Petrović, V.; Kühn, M. Hybrid-Lambda: A Low-Specific-Rating Rotor Concept for Offshore Wind Turbines. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribnitzky, D.; Petrović, V.; Kühn, M. A Scaling Methodology for the Hybrid-Lambda Rotor—Characterization and Validation in Wind Tunnel Experiments. Wind Energy Sci. 2025, 10, 1329–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M.H.A.; Zahle, F.; Sørensen, N.N.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Multipoint High-Fidelity CFD-Based Aerodynamic Shape Optimization of a 10 MW Wind Turbine. Wind Energy Sci. 2019, 4, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Shen, E.; Wu, J.; Guo, T.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, D. Aerodynamic Prediction and Design Optimization Using Multi-Fidelity Deep Neural Network. Aerospace 2025, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Fan, X.; Xu, S.; Li, B. Study on the Structural Strength Assessment of Mega Offshore Wind Turbine Tower. Energies 2024, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantes, C.J.; Vernardos, S.M.; Koulatsou, K.G.; Gül, S. Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis of Tubular Steel Wind Turbine Towers near Man Door and Ventilation Openings to Optimize Design against Buckling. Vibration 2024, 7, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Baniotopoulos, C.C. Repowering Steel Tubular Wind Turbine Towers Enhancing Them by Internal Stiffening Rings. Energies 2020, 13, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Electric Renovables España, S.L. Rotor Assembly Having a Pitch Bearing with a Stiffener Ring. EP Patent EP 3 736 438 B1. 20 December 2023. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/EP3736438B1/en (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Gantes, C.J.; Koulatsou, K.G.; Chondrogiannis, K.-A. Alternative Ring Flange Models for Buckling Verification of Tubular Steel Wind Turbine Towers via Advanced Numerical Analyses and Comparison to Code Provisions. Structures 2023, 47, 1366–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, T.; Jenkins, N.; Sharpe, D.; Bossanyi, E.; Graham, M. Further Aerodynamic Topics for Wind Turbines. In Wind Energy Handbook, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Chapter 4; pp. 153–225. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119451143.ch4 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- IEC 61400-2:2013; Wind Turbines—Part 2: Small Wind Turbines. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Schepers, J.G.; Boorsma, K.; Aagaard Madsen, H.; Pirrung, G.; Bangga, G.; Sørensen, N.N.; Grinderslev, C.; Forsting, A.M.; Imiela, M.; Ramos-García, N.; et al. Final Report of IEA Wind Task 29, Phase IV: Validation of Aerodynamic Models; International Energy Agency, IEA Wind: Roskilde, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://iea-wind.org/task-29 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Cardamone, R.; Broglia, R.; Papi, F.; Rispoli, F.; Corsini, A.; Bianchini, A.; Castorrini, A. Aerodynamic Design of Wind Turbine Blades Using Multi-Fidelity Analysis and Surrogate Models. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2025, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, J.G.; Boorsma, K.; Madsen, H.; Pirrung, G.; Özçakmak, Ö.S.; Bangga, G.; Guma, G.; Lutz, T.; Potentier, T.; Braud, C.; et al. IEA Wind TCP Task 29, Phase IV: Detailed Aerodynamics of Wind Turbines; IEA Wind: Roskilde, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.B.; Ghia, U.; Roache, P.J.; Freitas, C.J.; Coleman, H.; Raad, P.E. Procedure for Estimation and Reporting of Uncertainty Due to Discretization in CFD Applications. J. Fluids Eng. 2008, 130, 078001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, E.; Siegfriedsen, S. Wind Turbines: Fundamentals, Technologies, Application, Economics, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Baniotopoulos, C. Effect of Internal Stiffening Rings and Wall Thickness on the Structural Response of Steel Wind Turbine Towers. Eng. Struct. 2014, 81, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiomitsu, D.; Yanagihara, D. Estimation of Ultimate Strength of Ring-Stiffened Cylindrical Shells under External Pressure with Local Shell Buckling or Torsional Buckling of Stiffeners. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 161, 107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinderslev, C.; Henriksen, L.C.; Zahle, F.; Bak, C. Implementation of the Blade Element Momentum Model on a Polar Grid and Its Aeroelastic Load Impact. Wind Energy Sci. 2020, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, S.; Biswas, A. Investigations on Self-Starting and Performance Characteristics of Simple H and Hybrid H-Savonius Vertical Axis Wind Rotors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 87, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, J.; Butterfield, S.; Musial, W.; Scott, G. Definition of a 5-MW Reference Wind Turbine for Offshore System Development. NREL/TP-500-38060; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Castaignet, D.; Barlas, T.K.; Buhl, T.; Poulsen, N.K.; Wedel-Heinen, J.J.; Olesen, N.A.; Bak, C.; Kim, T. Full-Scale Test of Trailing Edge Flaps on a Vestas V27 Wind Turbine: Active Load Reduction and System Identification. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, H.; Pearce, J.M. The Potential of Agrivoltaic Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, R.; Davis, D. Design Load Basis Guidance for Distributed Wind Turbines; SR-5000-91458; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Golden, CO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy25osti/91458.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Evans, S.; Dana, S.; Clausen, P.; Wood, D. A Simple Method for Modelling Fatigue Spectra of Small Wind Turbine Blades. Wind Energy 2021, 24, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, H.J. On the Fatigue Analysis of Wind Turbines. SAND99-0089; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Schaarup, J. (Ed.) Guidelines for Design of Wind Turbines; Risø National Laboratory/DNV: Roskilde, Denmark, 2001; 253p; Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/guidelines-for-design-of-wind-turbines (accessed on 30 July 2025).

| Objective | Method (Section) | Key Inputs and Settings | Primary Metrics | Acceptance/ Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build Cp(λ,β) and radial loads | BEM (Section 2.2) | 25 radial stations; Prandtl tip/hub; Glauert–Buhl; |Δa|, |Δa′| < 1 × 10−4 | Cp map; qn(r), qt(r) | Plateau at λ ≈ 2.4–2.8, β ≈ 8–14°; stable inductions |

| Check pressures and torque | CFD RANS (Section 3.3) | k–ω SST; y+ ≈ 1; residuals < 1 × 10−4; 3 meshes; goal monitors | Δp(μ), Mz | |ΔCp| ≲ 4%, Δp < ~6% vs. BEM; mesh-independent |

| Size ring/blade/pins | FEM static/modal (Section 3.4) | Shell/beam; load mapping from BEM/CFD; support cases | σvM, Utip, f1 (first natural frequency) | σvM ≤ 0.25·Rₚ0.2; Utip < 0.5%·R; f1 > 3·nmax (operating band) |

| Service life | S–N/Miner (Section 3.4.2/Section 3.4.4) | Goodman correction; duty blocks (Cut-in/Nominal/Extreme) | Dtotal; Life maps | Dtotal < 1; hot-spots localized |

| Credibility and scope | V&V/UQ * (Section 2.3; Section 4.4) | Convergence; model-to-model checks; literature anchors | Coherency BEM–CFD–FEM | Pre-declared test targets |ΔCp| ≤ 10%, |Δp| ≤ 15% |

| V (m/s) | n (rpm) to λ = 2.0 | λ = 2.6 | λ = 2.8 | λ = 3.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 38.2 | 49.7 | 53.5 | 57 |

| 4 | 51 | 66 | 71 | 76 |

| 5 | 64 | 83 | 89 | 96 |

| 6 | 76 | 99 | 107 | 115 |

| 7 | 89 | 116 | 125 | 134 |

| Operating Mode | V (m/s)/λ | Collective β (°) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Startup | ≤3/1.5–2.0 | 18–25 | High starting torque |

| Nominal | 5–6/2.6–2.8 | 8–12 | Maximum Cp, stable speed |

| Limiting | 7–10 | 4–6 | Power control, reduced noise |

| PV Mode | Low wind | ≈0 | Maximum solar exposure |

| Storm | ≥20 | 85–90 | Feathering, protection |

| λ | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.201 | 0.192 | 0.192 | 0.154 | 0.6 | 0.037 | 0.093 | 0.114 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.352 |

| 2.2 | 0.37 | 0.153 | 0.6 | 0.136 | 0.565 | −0.07 | −0.089 | −0.04 | 0.6 | 0.563 | 0.053 |

| 2.4 | 0.083 | 0.133 | 0.143 | 0.6 | 0.6 | −0.099 | −0.087 | −0.154 | 0.6 | 0.394 | 0.6 |

| 2.6 | 0.057 | 0.11 | 0.138 | 0.034 | 0.529 | −0.162 | −0.185 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.285 | 0.6 |

| 2.8 | 0.029 | 0.242 | 0.084 | −0.034 | 0.6 | −0.168 | −0.185 | −0.25 | 0.6 | −0.033 | 0.379 |

| 3.0 | −0.038 | 0.017 | 0.041 | 0.6 | 0.139 | −0.242 | −0.232 | −0.208 | 0.6 | 0.467 | 0.6 |

| 3.2 | −0.075 | −0.021 | 0.009 | −0.105 | 0.466 | −0.249 | −0.314 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.383 | −0.275 |

| Case | V (m/s) | λ | β (°) | Cp * | P (W) | Q (Nm) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-in | 3 | 2.0 | 22 | 0.12 | 14 | 3.52 | High pitch angle → sufficient torque for startup; low power output, but Cp reaches the imposed ceiling. |

| Nominal | 5 | 2.6 | 10 | 0.369 | 594.7 | 88.9 | Recommended operating regime (after corrections): Cp was capped; actual values may fall slightly below 0.6. |

| Extreme | 25 | 0.8 | 80 | −0.02 | −1450 | −109 | Very high β (feathering) ⇒ braking torque (negative power): case used for structural checks and braking analysis. |

| Case | V (m/s) | λ | β (°) | qn, peak (N/m) | μ(qn) | pnorm (Pa) | qt, peak (N/m) | μ(qt) | ptang (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-in | 3.0 | 2.0 | 22 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 39.8 | 0.77 | 90.5 |

| Nominal | 5.0 | 2.6 | 10 | 1.80 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 92.7 | 0.73 | 210.9 |

| Extreme (feather) | 25.0 | 0.8 | 80 | 15.13 | 0.41 | 25.1 | 416.4 | 0.27 | 946.0 |

| Case | Wind Speed (Velocity Inlet) | Blade Pitch β |

|---|---|---|

| Cut-in | 3 m/s | 0° (PV mode), 10°, 20° |

| Nominal | 5 m/s | 10° (operation) |

| Extreme | 25 m/s | 80° (feather) |

| Parameter | β = 10° | β = 20° |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum static/total pressure (Pa) | ~101,340 | ~101,365 |

| Axial force (N) | ~18 | ~35 |

| Torque (N·m) | ~2.5 | ~9 |

| Global Parameter (Goal) | Convergence | Final Value β = 10° | Final Value β = 20° | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG Maximum Static/Total Pressure | stabilizes in <25 iterations | ~101,340 Pa (≈+140 Pa vs. ambient) | ~101,365 Pa (≈+165 Pa vs. ambient) | At β = 20°, the pressure center rises slightly—flow is still attached, but the magnitude remains very small; flat blades do not create significant pressure differentials at 3 m/s. |

| GG Force Z (axial) | initial numeric spike, then flat | ≈18 N | ≈35 N | Doubling of force at β = 20° confirms increased lift; values are still modest → axial load is non-critical. |

| GG Torque Z (shaft torque) | converges in <50 iterations | ≈2.5 N·m | ≈9 N·m | Startup torque nearly triples at β = 20°—sufficient to overcome mechanical friction (≈3 N·m estimated from BEM). |

| Streamlines/velocity vectors | — | slight deviation, no recirculation | slight inclination toward suction side, no stall | Flow remains attached across the entire chord; actual angle of attack < 6° even at β = 20°. |

| Indicator (Goal) | Stabilized Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| GG Force Z | ≈350,000 N·mm → ≈350 N | Axial thrust is 7× greater than at 5 m/s; remains under the axial bearing capacity (1 kN) → structurally safe. |

| GG Torque Z | ≈100,000 N·mm → ≈100 N·m | Double the nominal torque (~80 N·m at 5 m/s); with ω ≈ 12 rad/s, this yields P ≈ 1.2 kW, confirming Cp(λ,β) curve at λ ≈ 2.4. |

| Maximum Pressure | ~101,520 Pa (≈+200 Pa) | Pressure increases linearly with ρV2; value remains far below 1 kPa—expected for flat blades. |

| Convergence | Stable after 25 iterations | Robust solution, mesh is adequate (y+ < 1). |

| Streamlines | Significant deviation, no major recirculation | Flow stays attached to the chord → β = 20° is still below stall angle even at Re ≈ 5 × 105. |

| Case | pnorm, peak (Pa) | ptang, peak (Pa) | Source q (BEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-in | 0.38 | 90.5 | [36] |

| Nominal | 0.51 | 210.9 | [36] |

| Extreme | 25.1 | 946.0 | [36] |

| Boundary Condition | σvM,max (MPa) | Location | URES (mm) | Location | FOS | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed/ Fixed | 10 | Upper joint (hub side) | 0.07 | Tip/upper joint | 3.0 | Very stiff; tangential moment closed through ring |

| Fixed/Hinge | 11.3 | Upper joint | 0.67 | Tip/upper joint | 3.0 | Slight increase in stress; higher torsional flexibility |

| Hinge/Hinge | 392.2 | Upper shaft in the ring | 16.8 | Lower pitch-arm lever | 0.70 | Local yielding; global deflection due to under-dimensioned lever |

| Step | Model/Boundary Conditions | Loading Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 0. CAD Model |

| — |

| 1. “Flat” Case (β = 0°) |

| Verifies torsional stiffness of assembly: σvM,max < 0.3·Rp0.2, Utip < 1 mm |

| 2. β Parameter—Cut-in | Blades rotated at β = 0°, 10°, 20° | Evolution of σ and U in linkages & ring; identifies β threshold where FOS < 1.5 |

| 3. Nominal (V = 5 m/s) | Average β = 10° for all blades Pressure: qn = 0.51 Pa, qt = 210.9 Pa | Expected σvM,max ≈ 60–80 MPa in pivots; Utip ≈ 7 mm |

| 4. Extreme (Feather) | Simultaneous β = 80° Pressure: qn = 25.1 Pa, qt = 946 Pa | Checks for local yielding in pivots: σvM,max < Rp0.2, global FOS > 1 |

| 5. Comparison & Calibration | Compare σvM,max and Utip to data from Zhang et al. [22] for β = 80°, and Sharpe & Jenkins [27] for β = 0°; geometry to be adjusted if FOS < 1.5 | — |

| FEM Result | Value | Location | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum von Mises stress (σvM,max) | 44.6 MPa | Hub–ring interface, near the first blade connection | ≈16% of Rp0.2 (Al 6061-T6 = 276 MPa) ⇒ good safety margin; stress concentration caused by bolt shear toward the ring |

| Total displacement (URES) | 2.02 mm | Blade tips along 60° arc | Equivalent to a rotation of β ≈ 0.3°; <0.15%·R → stiffness is acceptable for Cut-in regime |

| Safety Factor (FOS) | ≥3 across the entire rotor (plot capped at 3.00) | Even in critical zones, FOS > 3 → structure remains elastic; minimum recommended by IEC 61400-2 for prototypes is 1.5 | - |

| Case | Pitch β | pnorm (Pa) | ptang (Pa) | Cycles ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-in (3 m·s−1) | 10°/20° | 0.38 | 90.5 | 5 × 107 |

| Nominal (5 m·s−1) | 10°/20° | 0.51 | 210.9 | 5 × 107 |

| Extreme/feather (25 m·s−1) | 10° | 25.1 | 946 (braking) | 2 × 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiriță, G.D.; Filip, V.; Negrea, A.D.; Tătaru, D.V. Aero-Structural Analysis and Dimensional Optimization of a Prototype Hybrid Wind–Photovoltaic Rotor with 12 Pivoting Flat Blades and a Peripheral Stiffening Ring. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413027

Chiriță GD, Filip V, Negrea AD, Tătaru DV. Aero-Structural Analysis and Dimensional Optimization of a Prototype Hybrid Wind–Photovoltaic Rotor with 12 Pivoting Flat Blades and a Peripheral Stiffening Ring. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413027

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiriță, George Daniel, Viviana Filip, Alexis Daniel Negrea, and Dragoș Vladimir Tătaru. 2025. "Aero-Structural Analysis and Dimensional Optimization of a Prototype Hybrid Wind–Photovoltaic Rotor with 12 Pivoting Flat Blades and a Peripheral Stiffening Ring" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413027

APA StyleChiriță, G. D., Filip, V., Negrea, A. D., & Tătaru, D. V. (2025). Aero-Structural Analysis and Dimensional Optimization of a Prototype Hybrid Wind–Photovoltaic Rotor with 12 Pivoting Flat Blades and a Peripheral Stiffening Ring. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413027