Abstract

This study synthesizes novel photosensitizer calcination betaine hydrochloride carbon dots (CBCDs) to address the critical challenge of Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) biofilms, a major cause of root canal treatment failure. To this end, this study investigates the effective elimination via reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated by these CBCDs. CBCDs were prepared by calcining betaine hydrochloride and rigorously characterized for their structural and chemical properties using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Their optical characteristics were also thoroughly analyzed through UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy. The RNO-ID assay was performed to explicitly confirm ROS production, particularly verifying significant singlet oxygen (1O2) generation. Bactericidal efficacy of the CBCDs was comprehensively evaluated against planktonic E. faecalis and its formed biofilms. Live/dead staining was subsequently performed to observe their state after treatment. As a result, TEM confirmed nanosized CBCDs, and FTIR/XPS analyses identified crucial functional groups. Colony Forming Unit (CFU) assays revealed a dose-dependent reduction in E. faecalis viability, achieving complete eradication at 200 mg/L under light irradiation. Complete cell death and inactivation of the formed biofilms with increasing CBCD concentrations were also strongly evidenced by red fluorescence. The obtained results underscore CBCDs as highly effective photodynamic agents for the robust elimination of E. faecalis biofilms, offering a promising new strategy to combat persistent oral infections.

1. Introduction

Root canal treatment (RCT) is a therapeutic procedure aimed at alleviating pain and saving teeth by addressing infections or inflammation of the dental pulp (nerve tissue) inside the tooth. It involves removing the damaged or infected pulp tissue, disinfecting the canal space, and then filling it with biocompatible artificial materials. Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacterium primarily residing in the human gastrointestinal tract. This bacterium can enter the oral cavity through various pathways, and once established, it successfully colonizes and proliferates, owing to its remarkable adaptability to environmental changes such as pH, temperature, and nutrient availability. Specifically, E. faecalis acts as an opportunistic pathogen, thriving in microbial ecosystems where other oral microorganisms struggle to survive, such as carious lesions, periodontal pockets, and particularly infected dental root canals, where nutrients are limited and oxygen is scarce. Furthermore, its potent biofilm-forming capabilities and resistance to various antibiotics allow it to persist in the oral cavity, making it a major etiological agent in the failure of dental treatments [1,2,3].

The prevalence of E. faecalis in cases of root canal treatment failure has been widely reported to range from 24% to 77%, with some specific studies observing it at 38%. [4,5]. Researchers are particularly interested in methods for eradicating E. faecalis because, while obligate anaerobic bacteria (such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella nigrescens) that play a major role in lesion development are readily eliminated by medications used in root canal treatment, E. faecalis is difficult to eradicate due to its robust resistance mechanisms to various antibiotics, including the potent antibiotic vancomycin. Furthermore, even when agents like sodium hypochlorite are used, the number of E. faecalis can be reduced, but complete elimination is known to be challenging [6,7,8]. E. faecalis is also a well-known biofilm-forming bacterium, and recent reports suggest that the formation of biofilms is a key mechanism enabling bacteria to survive and resist antimicrobial agents [9,10,11]. Therefore, extensive research is being conducted to find effective methods to eliminate E. faecalis and the biofilms it forms.

Among these, there is increasing interest in the development of new materials with photosensitizer potential [12]. A photosensitizer refers to a chemical substance that absorbs light energy of a specific wavelength to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and then utilizes the strong oxidizing power of these ROS to attack and eradicate cancer cells or bacteria [13,14]. Carbon dots are one of various materials gaining attention as photosensitizers. Carbon dots are promising photosensitizer candidates in the field of periodontal disease treatment due to their biocompatibility, low toxicity, low drug resistance, high efficiency, easy modulation of optical properties, and ability to generate ROS [15,16]. However, what truly distinguishes carbon dots and elevates their potential for addressing challenging bacterial infections, particularly biofilms, lies in their intrinsic physicochemical properties. Their ultrasmall size is critical, enabling them to effectively penetrate the dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix of biofilms, where larger antimicrobial agents frequently struggle to reach the embedded bacteria. Moreover, the high surface-to-volume ratio allows for versatile surface functionalization, which can be tailored to enhance targeted delivery to bacterial cells or to improve dispersibility within complex biological environments [17,18]. Carbon dots also exhibit superior photostability, significantly reducing photobleaching common in traditional organic photosensitizers, thereby ensuring sustained and potent ROS generation critical for complete pathogen eradication. Importantly, the careful selection of precursors and synthesis conditions, such as thermal treatment, allows for the precise engineering of their electronic structure, often involving heteroatom doping (e.g., nitrogen, oxygen). This doping plays a crucial role in dramatically enhancing their efficiency in producing highly potent ROS, specifically singlet oxygen (1O2), upon light activation. This combination of attributes positions carbon dots as exceptionally powerful tools for overcoming persistent microbial threats like E. faecalis biofilms [19,20]. Specifically, research on the influence of photosensitizer structural characteristics on the generation efficiency of ROS, especially singlet oxygen (1O2), is actively progressing [21,22]. Recently, many studies on photosensitizers that offer advantages over conventional photosensitizers, such as chlorin e6 and protoporphyrin IX, using carbon-based materials employing methods such as hydrothermal, microwave, and pyrolysis, are actively being reported [23,24].

In this study, we synthesized carbon dots with a novel structure by calcination using a furnace, selecting betaine hydrochloride as the starting material. Betaine hydrochloride, a zwitterionic amino acid derivative that is widely distributed in nature and readily available, rich in both nitrogen and oxygen atoms, was strategically chosen as the precursor. Its inherent chemical composition makes it an excellent candidate for ‘self-doping’ during the thermal decomposition process. This heteroatom doping (particularly nitrogen and oxygen) is critical as it fundamentally alters the electronic band structure of the resulting carbon dots, significantly enhancing their photoluminescence properties and, more importantly for our application, optimizing their efficiency in generating highly potent reactive oxygen species, particularly 1O2, upon light activation. Although betaine hydrochloride itself does not exhibit photoactivity, the controlled thermal decomposition via calcination effectively transforms this inert organic molecule into highly fluorescent and photosensitizing carbon dots. This approach ensures the formation of a carbon-based nanomaterial with tailored electronic states and surface functionalization, ideal for targeted photodynamic therapy and robust E. faecalis biofilm elimination. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the potential of CBCDs as an effective photosensitizer for inactivating E. faecalis and its biofilms, by elucidating their structural characteristics and the mechanisms of ROS generation and subsequent action.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Synthesis of Calcination Betaine Hydrochloride Carbon Dots (CBCDs)

Calcination betaine hydrochloride carbon dots were synthesized through a calcination method. Briefly, 5 g betaine hydrochloride (Alfa Aesar, Tewksbury, MA, USA) was placed in a crucible. Afterward, the crucible was heated at 280 °C for 20 min with a heating rate of 10 °C/min in a furnace (RF2700, Jaemyung Industry, Gimpo, Republic of Korea). The brown powder was obtained and subsequently dissolved in 10 mL of deionized (DI) water. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to remove the insoluble residue. And the solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to remove large particles. Finally, the uncomplexed betaine hydrochloride was then removed by dialyzing the sample using a dialysis membrane (Biotech CE Tubing MW = 100 ~ 500 Da, Repligen, Waltham, MA, USA). The solution was dried at 90 °C after adding DI water at a 1:9 ratio.

2.2. Characterization of CBCDs

To characterize the synthesized CBCDs, various analyses were performed. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using a Talos F200X (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to confirm their size and morphology. The functional groups of the CBCDs were analyzed using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy within the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 (Spectrum Two, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). To determine the elemental composition of the CBCDs, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed using a K-ALPHA XPS instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The absorbance of the CBCDs was measured using a multiplate reader (BioTek Synergy HTX, Agilent/BioTek, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The photoluminescence (PL) emission spectra of the CBCDs for different emission spectra was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary Eclipse, Agilent, Houston, TX, USA).

2.3. Antibacterial Assay

E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) was cultured in BHI (Brain Heart Infusion) medium (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The bacterial suspension was adjusted to a density of 1 × 106 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL by measuring its optical density at 600 nm and referring to a pre-established standard curve. This standard curve was established by preparing bacterial suspensions of various known concentrations, then comparing their corresponding optical density at 600 nm (OD600) values with directly enumerated CFU counts. Antibacterial tests were conducted on the concentration of CBCDs (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 ppm) with or without light irradiation. CBCDs were diluted in DI water at each concentration to create a solution, and 100 μL of bacteria and 300 μL of solution were mixed in a 48-well plate and treated in an incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Afterwards, each well was divided into two groups: those that were irradiated with a dental light-curing unit (LCU) (Bluephase, Ivocla Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) at approximately 120 mW/cm2 light intensity for 5 min, and those that were not. After that, 100 µL of the solutions were collected from each well, serially diluted and spread onto BHI agar plates. Plates containing 30–300 colonies were then counted to determine the CFU after culturing for 24 h at 37 °C.

2.4. Singlet Oxygen Test

To measure the production of singlet oxygen when CBCDs were exposed to dental LCU irradiation, the RNO-ID (p-nitrosodimethylaniline (RNO)-imidazole (ID)) methods, as reported in the literature, were used. To prepare the RNO-ID solution, 0.225 mg of RNO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 16.34 mg of ID (Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd., Siheung, Republic of Korea) were added to 30 mL of DI water, and the mixture was stirred until completely dissolved. First, for a time-dependent analysis of singlet oxygen production at a specific concentration, the mixed solution was irradiated, and its optical density (OD) was measured using a microplate reader at intervals of 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. This mixed solution was prepared by adding 100 µL of CBCDs solution (with a final CD concentration of 200 mg/L) to 200 µL of the as-prepared RNO-ID solution. Additionally, to investigate the concentration-dependent singlet oxygen production, mixed solutions were prepared by individually adding 100 µL of CBCDs solutions at various final concentrations (0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mg/L) to 200 µL of the as-prepared RNO-ID solution. These mixed solutions were also irradiated, and their OD was measured using a microplate reader at intervals of 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min.

2.5. Evaluation of In Vitro Antibiofilm Properties

Live/dead bacterial staining assay was conducted to evaluate the antibacterial properties of CBCDs. First, to each well, 500 µL of a mixture (1:1 v/v) of E. faecalis cell suspension (1 × 108 CFU/mL) and Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, BD, San Jose, CA, USA) supplemented with 0.5% glucose (Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd., Siheung, Republic of Korea) was added. The wells were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under aerobic conditions, with fresh medium replaced at 24 h. After being incubated with CBCDs (0, 100, 200, 1000 ppm), the biofilms were subjected to 5 min irradiation. Subsequently, the biofilms were washed with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS). Then they were stained with Calcein AM (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) (100 mg/L) and propidium iodide (PI, BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, USA) (50 mg/L) for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the biofilms were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM700, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The results of antibacterial tests were analyzed by t-test for groups between without and with LCU p values < 0.05 are considered significant.

3. Result

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of CBCDs

3.1.1. TEM Analysis

In this study, light brown CD powders were synthesized by calcination using a furnace, with betaine hydrochloride as the starting material. The morphology and size of the thus-synthesized CBCDs were confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in Figure 1A, the CBCDs exhibited well-dispersed spherical morphology with a size less than 10 nm. This result demonstrates that the CBCDs were synthesized at the nanoscale. The average particle size (Dmean) was quantitatively determined by measuring the CBCDs from TEM micrographs using ImageJ software (version 1.54g). The analysis revealed that the CBCDs exhibited a nearly spherical shape with an average diameter of 3.36 ± 0.07 nm. The particle size distribution, fitted with a Gaussian curve, is presented as a histogram in Figure 1B, further confirming the uniform size and dispersion of the synthesized nanomaterials.

Figure 1.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of synthesized CBCDs. (A) TEM image demonstrates the spherical morphology and uniform size distribution of CBCDs (Scale bar: 10 nm). (B) Particle size distribution of synthesized CBCDs with a Gaussian-fitting curve (red line).

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

The FTIR spectra of betaine hydrochloride and the synthesized CBCDs were comparatively analyzed. As shown in Figure 2, strong C-H stretching vibration peaks (2972 cm−1, 2841 cm−1) attributed to the three methyl groups (-CH3) bonded to nitrogen were observed in betaine hydrochloride. Conversely, these CH3 peaks disappeared in the CBCDs, and a broad peak corresponding to N-H stretching vibration newly appeared in the 3000–3600 cm−1 region. This change indicates that during the calcination of betaine hydrochloride, the methyl groups bonded to nitrogen (N) were demethylated and removed, leading to the formation of new N-H groups. Additionally, the C=O stretching vibration peak (1745 cm−1) of the carboxyl group (–COOH), which was observed in betaine hydrochloride, disappeared in the synthesized material. Instead, a new peak appeared at 1638 cm−1, which appears to be attributable to a C=N bond. This finding is consistent with the C=N bond formation results confirmed by XPS analysis. It is thus inferred that the N-H groups formed by demethylation reacted with the carbon atom of the existing carboxyl group to form C=N double bonds. Furthermore, the disappearance of the 1200 cm−1 peak (attributable to a specific C-N stretching vibration) observed in the FTIR results of betaine hydrochloride indicates the complete loss of the C-N bonds in the original N+(CH3)3 structure.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of betaine hydrochloride (black line) and CBCDs (red line).

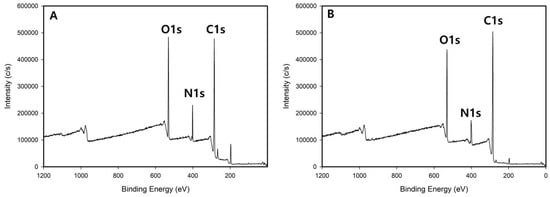

3.1.3. XPS Analysis

XPS analysis results are shown in Figure 3. According to the survey analysis, three typical C, N, and O peaks were observed (Figure 3A,B). From the deconvolution based on high-resolution XPS spectra, Figure 3C,D reveal that the O–C=O peak at 288.5 eV, previously observed in betaine hydrochloride, disappeared, and a new peak was detected at 287.5 eV. This signifies the formation of a C=N bond. Furthermore, the increase in C–C bond intensity suggests that the overall chain length of the CBCDs was extended by residual moieties. In contrast, the C–O bond at 285.5 eV showed negligible change in binding energy in both betaine hydrochloride and CBCDs, indicating no significant alteration during the synthesis process. In Figure 3E, a peak characteristic of quaternary ammonium nitrogen (N+) in betaine hydrochloride appeared at 401.8 eV. Conversely, in Figure 3F, the 401.8 eV peak decreased, and a new peak corresponding to the C=N bond increased at 399.5 eV. This, in conjunction with the previous FTIR results, suggests that the C=N bond was formed as some methyl groups (CH3) attached to N+ in betaine hydrochloride were detached through demethylation. The reduction in the intensity of the 401.8 eV peak further supports this. In the O1s spectrum shown in Figure 3G, the carboxyl group oxygen peak of betaine hydrochloride was observed at 531.5 eV. However, in Figure 3H, the 531.5 eV peak disappeared, and a new peak corresponding to the C–O bond appeared at 530.0 eV. Consistent with the earlier N1s results, this implies that the original C=O bond oxygen site changed with the formation of the C=N bond.

Figure 3.

XPS survey spectra of betaine hydrochloride (A) and CBCDs (B), C1s high-resolution spectra of betaine hydrochloride (C) and CBCDs (D), N1s high-resolution spectra of betaine hydrochloride (E) and CBCDs (F), O1s high-resolution spectra of betaine hydrochloride (G) and CBCDs (H).

3.2. Characterization of Optical Properties

To investigate the changes in the optical properties of the synthesized CBCDs, their absorbance was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. While betaine hydrochloride showed almost no absorbance above 400 nm, the synthesized CBCDs exhibited light absorption in the range of 400 nm to 600 nm (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) UV-Vis spectra of betaine hydrochloride and CBCDs; (B) Fluorescence spectra of CBCDs.

Furthermore, to confirm the photoluminescence properties of the synthesized CBCDs, their fluorescence was analyzed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer. As shown in Figure 4B, the synthesized CBCDs began to emit fluorescence around 300 nm, reaching maximum intensity at 350 nm. Subsequently, the emission wavelength gradually shifted towards longer wavelengths, and the fluorescence intensity slowly decreased. Visually, the emission of blue light was also confirmed when irradiated with light in a similar region.

3.3. Confirmation of Singlet Oxygen (1O2) Production

The production of singlet oxygen (1O2) assayed for different treatment conditions (light irradiation time and CBCD concentration) is shown in Figure 5. Figure 5A showed that upon light irradiation of CBCDs, the characteristic peak absorbance of RNO at 440 nm continuously decreased over time. This clearly demonstrates that the synthesized CBCDs continuously generate 1O2 through photoactivation. Furthermore, to investigate whether the synthesized CBCDs produce 1O2 in a concentration-dependent manner, RNO absorbance changes were measured for 20 min for various CBCD concentrations (0, 50, 100, 150, 200 mg/L). At this fixed irradiation time of 20 min, the results revealed that the intensity at 440 nm decreased more significantly as the CBCD concentration increased.

Figure 5.

Singlet oxygen (1O2) generation by RNO-ID method following 5 min light irradiation intervals. (A) At 200 ppm. (B) Across various concentrations (0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 ppm).

3.4. In Vitro Evaluation of Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity

3.4.1. Assessment of Antibacterial Activity Against Planktonic Bacteria

Figure 6 shows the result of antibacterial activity of CBCDs under light irradiation against E. faecalis against the planktonic state. According to the assay, when CBCD concentrations were increased from 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, to 50 mg/L, no significant bactericidal effect was observed if there was no light irradiation. On the other hand, if there was light irradiation by LCU, a killing rate reached approximately 69.4% at 10 mg/L concentration, and complete eradication was achieved at 50 mg/L concentration. Therefore, LCU irradiation significantly affects the bactericidal effect (p < 0.05). These results are consistent with the RNO-ID assay findings, which confirmed that CBCDs generate 1O2 under light irradiation.

Figure 6.

CFU counts for E. faecalis viability under treatment of CBCDs with different concentrations without or with light irradiation using the dental LCU.

3.4.2. Assessment of Antibiofilm Activity Against E. faecalis Biofilms

Antibacterial activity of CBCDs for E. faecalis biofilms under light irradiation is shown in Figure 7 for different CBCD concentrations. In the case of control (no CBCDs, but with light irradiation), many green fluorescent spots are visible in the whole biofilm up to 10 µm thick. On the other hand, as the concentration of CBCDs was gradually increased, complete cell death resulted, leading to the observation of increasing red fluorescence. While planktonic bacteria could be completely eradicated with a relatively small concentration of 50 mg/L, biofilms approximately 10 µm thick required over 200 mg/L of CBCDs to achieve complete cell death across all layers.

Figure 7.

Confocal Z-stack images of differently treated CBCD-treated biofilms (0, 50, 100, 200, 1000 mg/L). Live and dead cells are stained by calcein-AM and PI, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study, CBCDs were successfully synthesized through a calcination method using a furnace. This approach offers advantages such as simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness, making it a highly suitable technique for the scalable production of nanomaterials for biomedical applications [25,26]. The synthesized CBCDs were then comprehensively evaluated for their photosensitizing potential, demonstrating potent bactericidal activity against E. faecalis in both planktonic and biofilm states. Given the increasing challenges posed by antibiotic resistance and the pervasive nature of E. faecalis in various infections, particularly in endodontic failures, the development of novel antimicrobial strategies such as photodynamic therapy is of paramount importance [27,28].

For photosensitizers to generate ROS, they must absorb light energy and transit from a ground state to an excited state. This excited-state photosensitizer subsequently produces ROS via either electron transfer (Type I reaction) or energy transfer (Type II reaction). Therefore, photosensitizers must be able to efficiently absorb light of specific wavelengths to be irradiated [29]. To confirm the light absorption range of the synthesized CBCDs, their absorption spectrum was measured. As a result, unlike the raw betaine hydrochloride, strong absorption peaks were observed in a broad wavelength range from approximately 380 nm to 600 nm. This spectrum demonstrates that CBCDs can effectively absorb light, particularly in the blue light region. Based on this, we decided to evaluate the photodynamic therapeutic efficacy of CBCDs using a dental LCU, which allows for convenient blue light irradiation without the need for complex light sources. Notably, a higher concentration of CBCDs was required to effectively eradicate E. faecalis biofilms compared to their planktonic counterparts. This significant disparity is primarily attributed to the inherent characteristics of biofilms, specifically their robust extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This intricate matrix, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA, and other polymeric compounds, acts as a formidable physical barrier [30]. It not only entraps the bacterial cells but also severely hinders the penetration of external antimicrobial agents, including photosensitizers and subsequently generated ROS [31]. This observation underscores the challenge of biofilm-associated infections and highlights the need for photosensitizers capable of overcoming such protective barriers.

Further mechanistic insight into the bactericidal action was provided by PI staining. The observation of complete red fluorescence within bacterial cells at CBCD concentrations of 200 mg/L or higher strongly indicated that the primary mode of cell death was mediated by severe cell membrane damage. PI is a fluorescent dye that only penetrates cells with compromised membranes; thus, its uptake serves as a reliable indicator of membrane integrity loss. This direct evidence of membrane disruption confirms the lytic effect of CBCD-generated ROS on bacterial structures. Structural analysis of the synthesized CBCDs revealed the presence of C=N bonds, which are hypothesized to contribute to their photosensitizing properties. While direct evidence establishing a definitive correlation between C=N bonds and photosensitizer activity is not yet fully elucidated in all previous studies, several well-established photosensitizers such as BODIPY and phthalocyanines contain multiple C=N double bonds in their molecular structures [32,33]. Therefore, it can be postulated that CBCDs also function as photosensitizers for similar reasons, driven by their C=N structure. The RNO-ID assay results confirmed that 1O2 was generated in a concentration-dependent manner, strongly supporting that the synthesized CBCDs can function as efficient concentration-dependent 1O2 photosensitizers. This demonstrates their potential for various optical applications, including future photodynamic therapy (PDT). ROS generation mechanisms include Type I, which forms hydroxyl radicals or superoxide radicals based on electron transfer [34], and Type II, which generates 1O2 based on energy transfer [35]. Complementary experiments were conducted to detect other ROS species (e.g., hydroxyl radicals, superoxide radicals), but no evidence of their generation was found. Given that 1O2 was the only ROS detected in this experiment, the ROS generation mechanism of our synthesized CBCDs appears to be Type II. 1O2 is a high-energy ROS in which both electrons are in a spin-paired state. It is generated when ambient oxygen molecules are activated by a photosensitizer during the process of photodynamic inactivation (PDI). Although 1O2 has a short lifespan, it possesses potent oxidative capabilities and primarily sterilizes bacteria through the following mechanisms. 1O2 non-selectively oxidizes critical biomolecules within bacterial cells, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, thereby inducing lethal oxidative stress. Specifically, it damages bacterial cell membranes and cell walls, altering their permeability and paralyzing cellular functions, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death. This broad-spectrum action offers an effective sterilization strategy for various bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains. Therefore, the synthesized CBCDs act as photosensitizers, absorbing light from the dental LCU and becoming excited. This selective generation of 1O2 is particularly advantageous for therapeutic applications, as 1O2 is known for its high cytotoxicity towards various biological targets, including bacterial cell membranes and intracellular components, while typically having a shorter diffusion range, potentially minimizing collateral damage to host tissues. This specificity further underscores their precise photosensitizing action and highlights their potential as targeted antimicrobial agents [36].

Beyond this photodynamic action, the intrinsic characteristics of our CBCDs, derived from betaine hydrochloride, necessitate further consideration regarding their antibacterial mechanism. Betaine hydrochloride possesses a quaternary ammonium structure, and compounds containing quaternary nitrogen are well-known for their potent antibacterial and antibiofilm properties, primarily by interacting with bacterial cell membranes, causing membrane damage, and denaturing cellular proteins. Although our XPS analysis in Figure 3F indicated a decrease in the characteristic quaternary ammonium nitrogen peak at 401.8 eV and the formation of C=N bonds during the calcination process, it is plausible that residual or modified nitrogen-containing structures derived from the original quaternary ammonium moiety could still contribute to the antibacterial activity. This could occur through direct electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged bacterial cell membranes, potentially increasing membrane permeability. Such membrane disruption could facilitate the cellular entry of CBCDs or enhance the destructive impact of the ROS generated within bacterial cells, thereby contributing to the effective inactivation of E. faecalis biofilms and synergizing with the ROS-mediated mechanism. [37,38] This powerful, multi-modal antimicrobial action, particularly the efficient photodynamic component of our CBCDs, offers a promising solution to the persistent problem of E. faecalis biofilms in root canal infections, highlighting the critical need for effective and practical antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation strategies.

Our study presents a novel photodynamic strategy for inactivating E. faecalis biofilms, utilizing calcination betaine carbon dots (CBCDs) to generate ROS under dental LCU irradiation. While carbon dot-based approaches for bacterial eradication are actively being researched, studies that directly integrate a carbon-dot photosensitizer, light-mediated ROS generation, and explicit targeting of E. faecalis biofilms under clinically practical blue light conditions are rarely reported. For instance, research employing Poly(Lysine)-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots (Xu et al., 2024) for E. faecalis elimination and biofilm disruption showed similarities in bacterial target and material type but did not include light irradiation or ROS generation as a primary mechanism [39]. Other studies, such as those on citric acid + PEI-based carbon dots [40] and PEI-based carbon dots [41], have utilized carbon dots and light activation to report antibacterial effects and biofilm inhibition. However, their experimental conditions (e.g., specific light wavelengths, CD concentrations, or distinctions between biofilm vs. planktonic states) and target organisms (E. faecalis) are often not precisely defined, making direct comparison challenging [40,41]. Therefore, our research provides a novel strategy that uniquely integrates a carbon dot photosensitizer with light-mediated ROS generation to effectively inactivate E. faecalis biofilms under clinically practical conditions.

While our current findings provide a robust foundation for the application of CBCDs in photodynamic therapy for E. faecalis infections, we acknowledge areas for further development. First, despite the effective antimicrobial action, a complete and detailed elucidation of the precise final chemical structure and composition of the synthesized CBCDs requires further in-depth investigation. Understanding the exact structural transformation during the calcination process would provide more definitive insights into their multifaceted antibacterial properties. Second, although the synthesized CBCDs exhibited excellent performance as photosensitizers, their relatively low fluorescence intensity suggests the need for further optimization when applied in future bioimaging or real-time diagnostic fields. Future research should explore the synthesis of carbon dots with highly efficient fluorescence properties, aiming for the simultaneous implementation of diagnosis and therapy (theragnostics) for oral diseases. Third, the experiments in this study were conducted entirely in an in vitro environment. Therefore, comprehensive in vivo studies will be required in the future to evaluate the actual efficacy of CBCDs against E. faecalis biofilms in complex biological environments, as well as aspects of safety such as their in vivo distribution, metabolism, and potential systemic toxicity. These future endeavors will further validate the clinical utility of CBCDs and contribute to developing advanced theragnostic solutions for persistent oral infections.

5. Conclusions

Addressing the formidable challenge of antibiotic resistance and persistent E. faecalis infections in dental settings, particularly within the realm of endodontic treatment, this study introduces calcination betaine carbon dots. Synthesized via a facile, cost-effective, and eco-friendly method, these calcination betaine carbon dots effectively eradicate E. faecalis in both planktonic and biofilm states by efficiently generating singlet oxygen (1O2) upon blue light irradiation from a dental light curing unit. These findings underscore the significant potential of calcination betaine carbon dots as an innovative, non-invasive therapeutic strategy. This promises a substantial contribution to effectively eradicating antibiotic-resistant oral pathogens and enhancing the clinical outcomes of dental treatments.

Author Contributions

W.K.: Writing—original draft, methodology, investigation, data curation, funding acquisition; F.G.-G.: review & editing, comment; S.-Y.P.: writing—review & editing, methodology, investigation; H.-O.J.: writing—review & editing, methodology, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00245879).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- La Rosa, S.L.; Snipen, L.-G.; Murray, B.E.; Willems, R.J.L.; Gilmore, M.S.; Diep, D.B.; Nes, I.F.; Brede, D.A. A genomic virulence reference map of Enterococcus faecalis reveals an important contribution of phage03-like elements in nosocomial genetic lineages to pathogenicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, C.H.; Schwartz, S.A.; Beeson, T.J.; Owatz, C.B. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asfaw, T. Biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium: Review. Int. J. Res. Stud. Biosci. 2019, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, T.; Hossain, M.; Mahmud, S.; Saleh, A.A.; Moral, M.A.A. Rate of Enterococcus Faecalis in Saliva and Failed Root Canal Treated Teeth—In Vivo Study. Eur. J. Dent. Oral Health 2023, 4, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, F.; Shakir, M. The Influence of Enterococcus faecalis as a Dental Root Canal Pathogen on Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Jhamb, S.; Mehta, M.; Bhushan, J.; Bhardwaj, S.B.; Kaur, A. Characterization of Enterococcus faecalis associated with root canal failures: Virulence and resistance profile. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2025, 28, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, T.A.; Zaki, B.M.; Mohamed, D.A.; Blasdel, B.; Gad, M.A.; Fayez, M.S.; El-Shibiny, A. Novel strategies for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis biofilm control: Bacteriophage (vB_EfaS_ZC1), propolis, and their combined effects in an ex vivo endodontic model. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2025, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyhani, M.F.; Rezagholizadeh, Y.; Narimani, M.R.; Rezagholizadeh, L.; Mazani, M.; Barhaghi, M.H.S.; Mahmoodzadeh, Y. Antibacterial effect of different concentrations of sodium hypochlorite on Enterococcus faecalis biofilms in root canals. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2017, 11, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhen, Y.; Baima, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Z. Strategies and mechanisms targeting Enterococcus faecalis biofilms associated with endodontic infections: A comprehensive review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1433313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Prentice, E.L.; Webber, M.A. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.-F.C.; O’Toole, G.A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lin, Y.; Ding, S.; Huang, M.; Jiang, L. Recent Advances in Clinically Used and Trialed Photosensitizers for Antitumor Photodynamic Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 3530–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wu, X.; Li, B. Carbon dots as a novel photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy of cancer and bacterial infectious diseases: Recent advances. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Pan, X.; Huang, Z.; Lu, C.; Quan, G. Photodynamic therapy for cancer: Mechanisms, photosensitizers, nanocarriers, and clinical studies. MedComm 2024, 5, e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechnikova, N.A.; Domvri, K.; Porpodis, K.; Istomina, M.S.; Iaremenko, A.V.; Yaremenko, A.V. Carbon Quantum Dots in Biomedical Applications: Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Aggregate 2025, 6, e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, D.; Al Kobaisi, M.; Hocking, R.K.; Fox, B. Properties, synthesis, and applications of carbon dots: A review. Carbon Trends 2023, 12, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Li, C.; Chen, Z. Bacteria-Derived Carbon Dots Inhibit Biofilm Formation of Escherichia coli without Affecting Cell Growth. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, S.; Radha, R.; Terro, T.; Diab, R.; Khodja, A.; Al-Sayah, M.H. Photoactivated carbon dots immobilized on cellulose for antibacterial activity and biofilm inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, R.; Fawad, A.; Ravindran, S.; Boltaev, G.; Philip, S.; Al-Sayah, M.H. Enhanced antimicrobial and biofilm-disrupting properties of gallium-doped carbon dots. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 27559–27574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Ding, J. Antibacterial carbon dots. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 30, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Sun, Q. Strategies to construct efficient singlet oxygen-generating photosensitizers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202202636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manav, N.; Kesavan, P.E.; Ishida, M.; Mori, S.; Yasutake, Y.; Fukatsu, S.; Furuta, H.; Gupta, I. Phosphorescent rhenium-dipyrrinates: Efficient photosensitizers for singlet oxygen generation. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 2467–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagianni, A.; Tsierkezos, N.G.; Prato, M.; Terrones, M.; Kordatos, K.V. Application of carbon-based quantum dots in photodynamic therapy. Carbon 2023, 203, 273–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Du, M.; Guo, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, B.; Fan, Y. Recent advances in carbon dots: Applications in oral diseases. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, L.; Xue, S.; Qu, D.; An, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Recent advances of carbon dots as new antimicrobial agents. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2200376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Singh, A.; Verma, A. Polysaccharide-derived carbon quantum dots: Advances in preclinical studies, theranostic applications, and future clinical trials. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2025, 26, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, A.; Kharbanda, S.; Thakur, P.; Shandilya, M.; Thakur, A. Biomedical application of carbon quantum dots: A review. Carbon Trends 2024, 17, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, P.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, M.; Wang, D.; Tang, B.Z. Type I photosensitizers based on aggregation-induced emission: A rising star in photodynamic therapy. Biosensors 2022, 12, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. Contemporary strategies and approaches for characterizing composition and enhancing biofilm penetration targeting bacterial extracellular polymeric substances. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 14, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.M.; Soares, F.A.; Reis, S.; Nunes, C.; Van Dijck, P. Innovative strategies toward the disassembly of the EPS matrix in bacterial biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, H.; Cakmak, Y. Functionalization of BODIPY Dyes with Additional C-N Double Bonds and Their Applications. Appl. Nanosci. 2023, 10, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihan, H.; Şeker, M.; Gülseren, G.; Bakırcı, M.E.; Boyacı, A.İ.; Cakmak, Y. Nitric Oxide Activatable Photodynamic Therapy Agents Based on BODIPY–Copper Complexes. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, Q.; Du, J.; Fan, X. Optimizing photosensitizers with Type I and Type II ROS generation through modulating. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2401454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Hou, J.; Tang, B.Z. Molecular engineering to boost AIE-active free radical photogenerators and enable high-performance photodynamic therapy under hypoxia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, R.W.; Kochevar, I.E. Spatially resolved cellular responses to singlet oxygen. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006, 82, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygoda, M.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Dynarowicz, K.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Aebisher, D. Cellular Mechanisms of Singlet Oxygen in Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, W.; Gao, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, J.; Dai, J. Antibacterial quaternary ammonium agents: Chemical diversity and biological mechanism. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, 114765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Saini, P.; Kumar, K.; Sethi, M.; Meena, P.; Gurjar, A.; Dandia, A.; Dhuria, T.; Parewa, V. Unlocking the molecular behavior of natural amine-targeted carbon quantum dots for the synthesis of diverse pharmacophore scaffolds via an unusual nanoaminocatalytic route. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 49083–49094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Arif, M.; Xing, X.; Deng, X.; Wang, D.; Meng, Y.; Wang, S.; Hasanin, M.S.; Wang, W.; et al. Poly(Lysine)-derived carbon quantum dots conquer Enterococcus faecalis biofilm-induced persistent endodontic infections. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 5879–5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fu, J.; Lin, H.; Xuan, G.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, G. Shining light on carbon dots: Toward enhanced antibacterial activity for biofilm disruption. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, e2400156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Lin, L.; Lin, L.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Huang, Q. Antibacterial carbon dots integrating multiple mechanisms for selective Gram-positive bacteria elimination and infected wound healing acceleration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 11407–11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).