Study on the Mechanism and Interpretability of Defect Features on Fatigue Damage in 6061 Aluminum Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

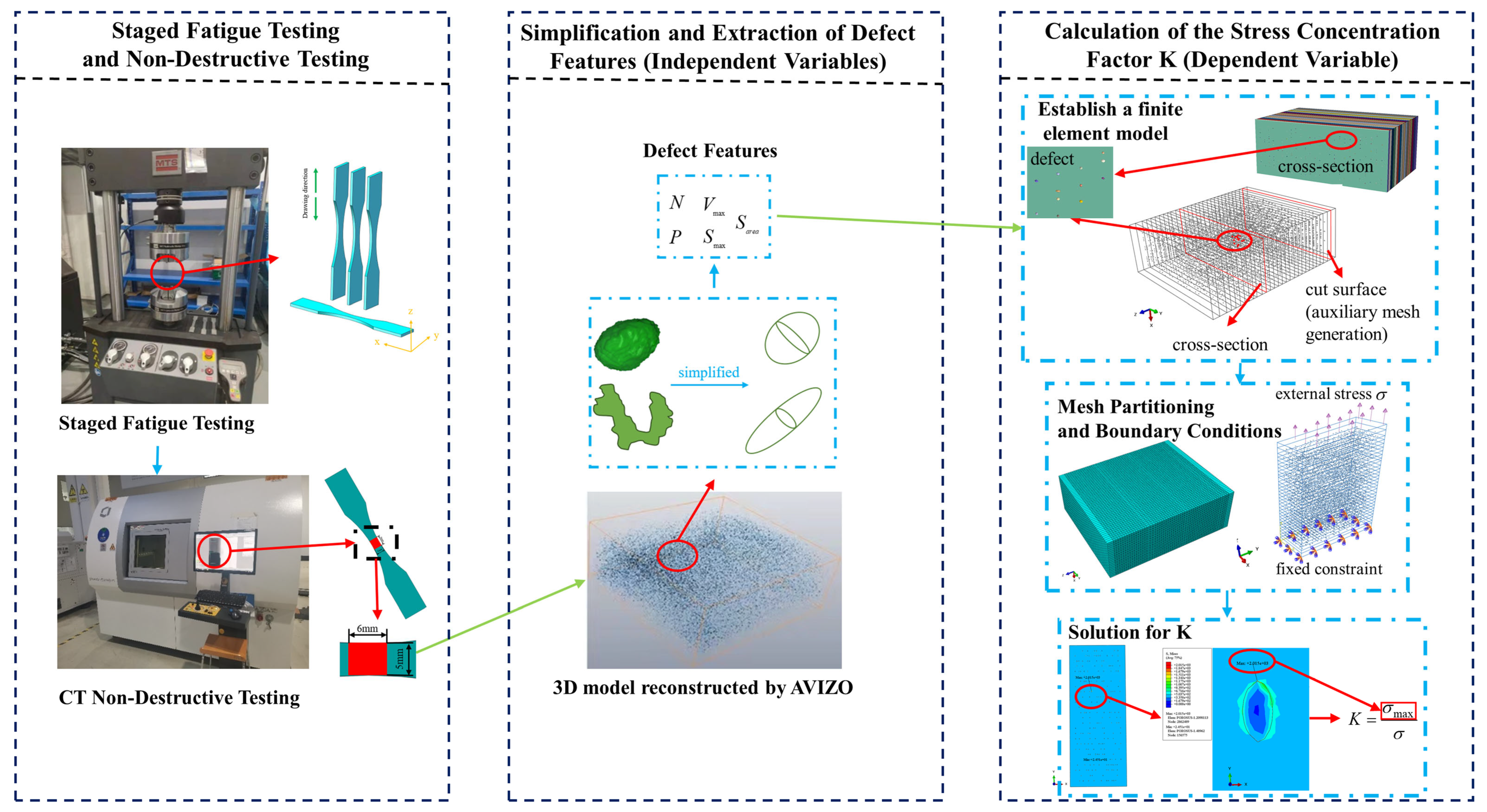

- (1)

- First, 15 sets of damaged specimens are prepared through staged fatigue testing, and their internal defect information is obtained using CT non-destructive testing technology. Using AVIZO v9.2.0 software, the defect data underwent screening, simplification, and 3D reconstruction to extract key pore feature parameters as independent variables for the model. Subsequently, an equivalent numerical model of the defect features is constructed in ABAQUS v2022. Through finite element analysis, the stress concentration factor k—representing the material of damage level—is obtained as the dependent variable. To mitigate the issue of limited original sample size, data augmentation methods are employed to generate additional representative samples.

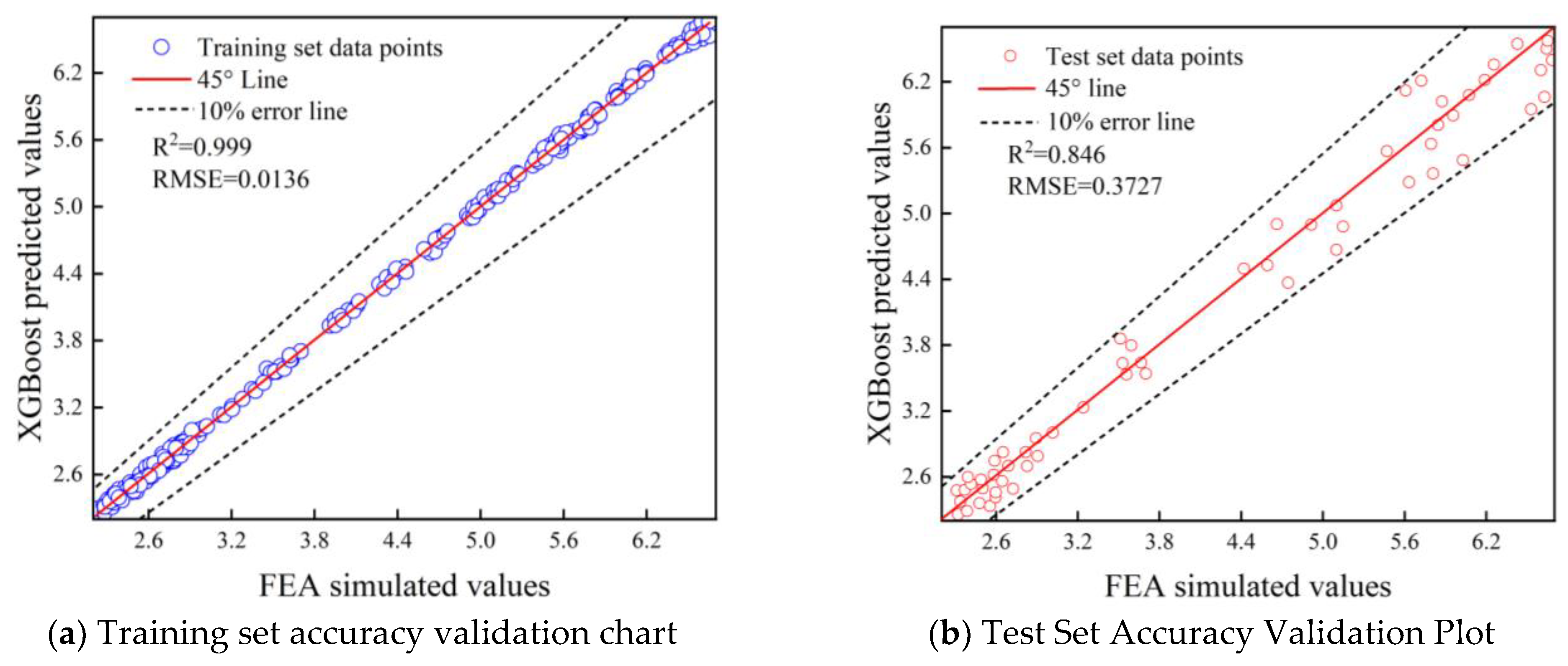

- (2)

- The overall sample is randomly divided into a training set and a test set at a 4:1 ratio. An XGBoost model is constructed using the training set to predict the stress concentration factor k for aluminum alloy materials, yielding a weighted ranking of defect features based on their influence on k. To evaluate model performance, the coefficient of determination R2 and root mean square error (RMSE) are selected as metrics for accuracy validation.

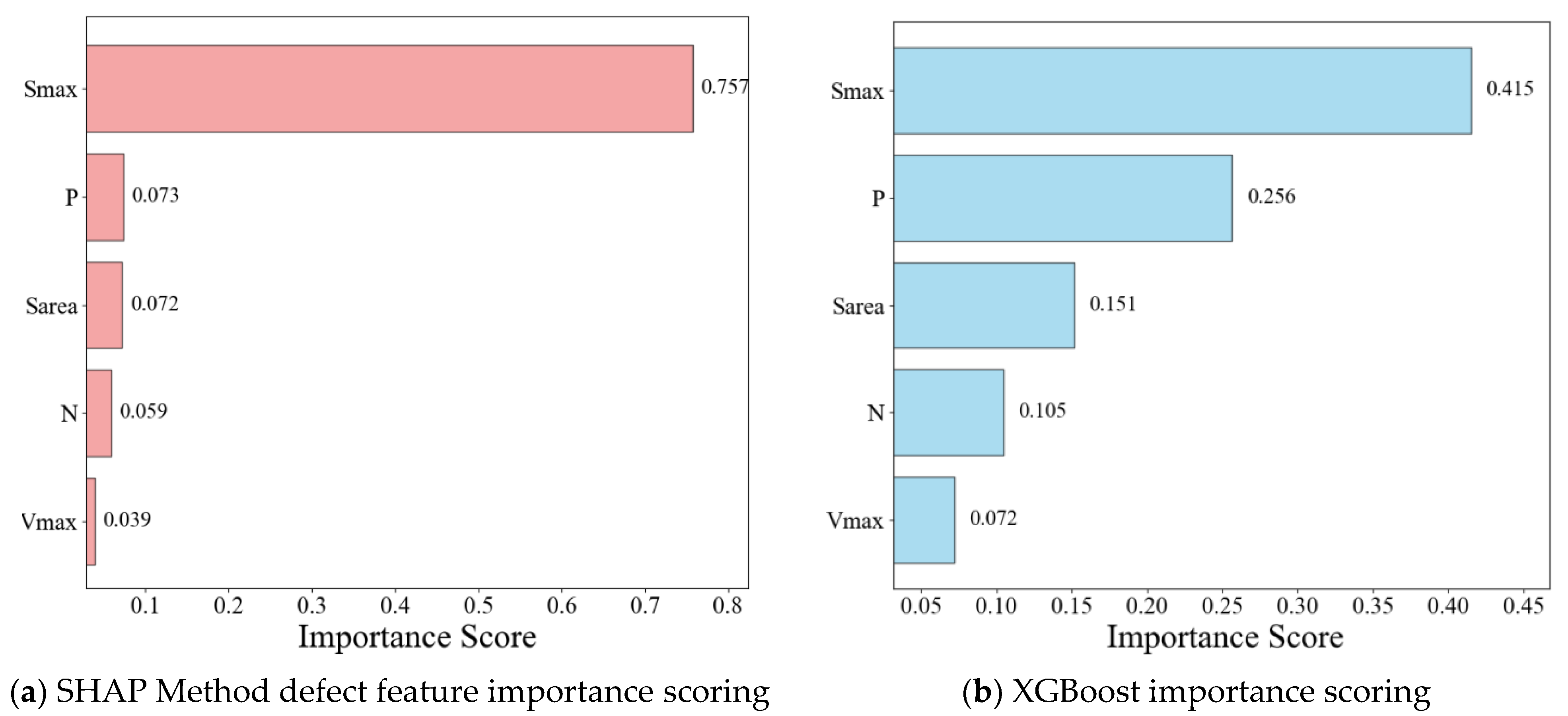

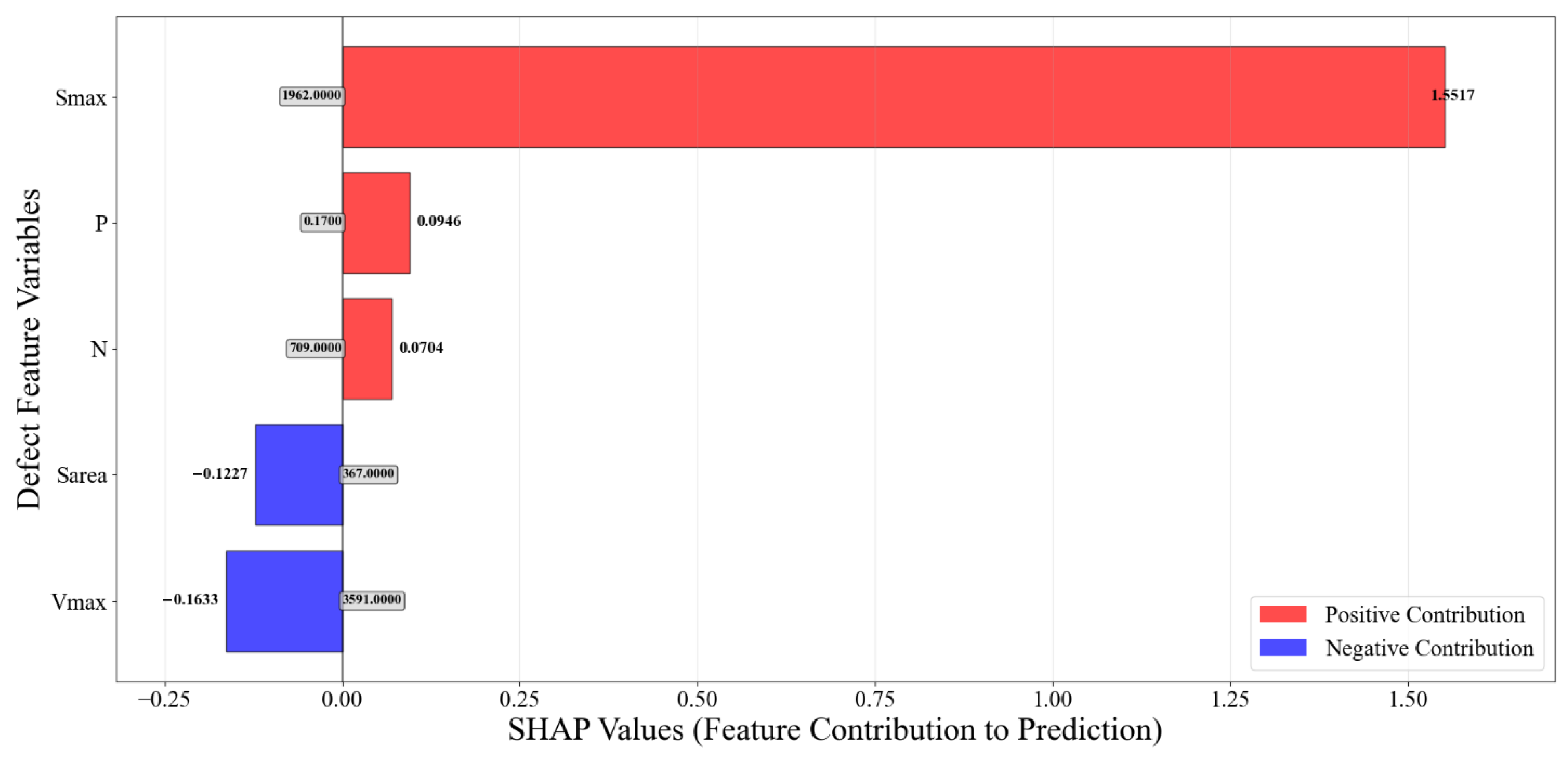

- (3)

- The SHAP interpretation framework is introduced to perform global and local interpretability analysis on the XGBoost model. Through global interpretation, the importance ranking of defect features corresponding to the stress concentration factor k is obtained based on the SHAP mean. This ranking is then compared with the feature weights output by the XGBoost model to achieve mutual validation. Through local explanations, the contribution values of defect features to the stress concentration factor k are calculated for any specific sample. Summing these contribution values yields the k value, which is then compared with the k value predicted by the XGBoost model to validate the accuracy of the local explanations.

- (4)

- By integrating the predicted values from the XGBoost model with the defect feature contribution revealed by SHAP analysis, a damage variable analysis model under the synergistic influence of multiple defect features is constructed. This model not only effectively predicts the stress concentration factor but also elucidates the quantitative mechanisms of different defect features, providing a theoretical basis and methodological support for fatigue damage assessment and risk control in aluminum alloy structures.

2.1. Acquisition of the Dataset

- (1)

- To obtain specimens with varying damage states, fatigue specimens are machined from 6061-T6 aluminum alloy according to ASTM E8/E8M-15a standards [26]. Axial tensile-tensile fatigue tests are conducted at room temperature using an MTS809 hydraulic servo testing system, with a stress ratio R = 0.1, frequency of 50 Hz, and sinusoidal waveform control. Five loading stages are established at 20,000, 40,000, 60,000, 80,000, and 100,000 cycles, with three replicate specimens per stage, totaling 15 specimens. This staged loading strategy enabled the acquisition of specimens exhibiting varying degrees of fatigue damage.

- (2)

- To obtain defect features within the specimens, this study employed an X-ray micro-computed tomography system for non-destructive testing of fatigue specimens. By scanning a specific region (6 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm) in the center of the specimen, approximately 1600 two-dimensional slices containing defect information are obtained and converted into TIF format images. Subsequently, AVIZO 9.2.0 software is employed for three-dimensional reconstruction and feature extraction of this region, enabling precise localization and quantification of defect geometric parameters across different damage stages of the specimens.

- (3)

- The initial defect features obtained using AVIZO 9.2.0 software include the number of holes , maximum hole volume Vmax, maximum damaged surface area Smax, maximum projected area Sarea, and porosity P. To establish an effective finite element model, the reconstructed defect information requires screening and simplification. The screening process primarily relies on two parameters: hole tendency and defect volume. Holes with a hole tendency greater than 1 and a volume exceeding 1000 are identified as valid holes and retained for modeling. To further enhance the convergence and accuracy of numerical calculations, the irregular geometries of identified defects are uniformly simplified into regular ellipsoids. This simplification strategy preserves key geometric features while significantly improving the efficiency and stability of subsequent finite element analysis.

- (4)

- The stress concentration factor k is a key parameter characterizing the local stress amplification effect at geometric discontinuities in structures. This study employs it as an intermediate variable for assessing material damage levels. By utilizing the finite element method (FEA) based on ABAQUS 2022 software, the k values for each specimen are calculated to quantify the degree of stress concentration induced by defects. To ensure physical rigor, the simulation was formulated as a quasi-static boundary value problem, as inertial effects were considered negligible at the experimental loading frequency of 50 Hz. The mechanical response is governed by the equilibrium equation neglecting body forces, , subject to the isotropic linear elastic constitutive law , where and denote the stress and strain tensors, respectively. To guarantee the numerical accuracy of the calculated k values, a mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted. The defect regions were discretized using second-order tetrahedral elements (C3D10M) to capture the curvature of the simplified ellipsoids. The local mesh density was iteratively refined until the variation in the maximum Von Mises stress was less than 5%, ensuring that the numerical solution converged to a stable, mesh-independent result.

- (5)

- To address the issue of limited sample size in the original experimental data, this study employed a data augmentation method based on statistical distribution. The initial 15 sample groups were synthetically expanded using the NumPy library (version 1.23.5) within the Python 3.10 environment. While ensuring the synthetic data maintained consistent statistical characteristics with the original data, this approach effectively increased the dataset size, providing robust support for subsequent machine learning modeling. The augmented portion of the dataset is shown in Table 1.

2.2. Establishing the Prediction Model

2.2.1. Establishment of the XGBoost Model

2.2.2. Establishment of the Evaluation Model

2.2.3. Establishment of SHAP Explainable Models

3. Analysis of the Results

3.1. Analysis of Hyperparameter Optimization for Predictive Models

3.2. Evaluation Model Analysis

3.3. Model Interpretability Analysis

4. Construction of the Damage Variable

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- High-Fidelity Prediction beyond “Black Boxes”: The constructed XGBoost model demonstrated superior predictive capability compared to traditional empirical methods. More importantly, by integrating SHAP analysis, this study successfully overcame the opacity of conventional machine learning. The framework not only predicts damage accurately but also visualizes the decision-making process, ensuring the physical consistency required for engineering applications.

- (2)

- Decoupling Defect Morphology Mechanisms: The SHAP-based global interpretation quantitatively revealed that defect morphology (specifically the maximum damaged surface area, Smax) exerts a more critical influence on fatigue damage than total defect volume (Vmax). This finding challenges the traditional volume-centric assessment criteria, suggesting that quality control should prioritize the geometric sharpness of defects. The consistency between SHAP rankings and mechanical stress concentration theories confirms the physical validity of the data-driven model.

- (3)

- Generalizability and Engineering Impact: A quantitative damage variable was constructed to facilitate real-time safety assessment. Although the experiment was conducted at a nominal frequency of 50 Hz, the proposed framework is inherently robust for fatigue durability tasks. Given the low strain-rate sensitivity of aluminum alloys at room temperature, the identified intrinsic correlations between defect features and damage accumulation remain valid across typical engineering frequency ranges (10–100 Hz). Consequently, this framework provides a generalized, scientific basis for intelligent maintenance and decision-making in aerospace and rail transit sectors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yong, Y. Research on properties and applications of new lightweight aluminum alloy materials. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 84, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Gajević, S.; Sharma, L.K.; Pradhan, R.; Sharma, Y.; Miletić, I.; Stojanović, B. Progress in aluminum-based composites prepared by stir casting: Mechanical and tribological properties for automotive, aerospace, and military applications. Lubricants 2024, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, R.; Palombi, A.; Richetta, M.; Varone, A. Additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys for aeronautic applications: Advantages and problems. Metals 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassu, N. Prevention of Casting Defects in An Aluminum Alloy Component. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, A.M.; Samuel, E.; Songmene, V.; Samuel, F.H. A review on porosity formation in aluminum-based alloys. Materials 2023, 16, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, W.; Zhan, J.; Yu, Y.; Fan, Z. Investigation on characteristic and formation mechanism of porosity defects of Al–Li alloys prepared by sand casting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 4063–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhadfar, P.D.; Thompson, S.; Saharan, A.; Phan, N.; Shamsaei, N. Structural integrity of additively manufactured aluminum alloys: Effects of build orientation on microstructure, porosity, and fatigue behavior. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadot, Y. Fatigue from defect: Influence of size, type, position, morphology and loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 154, 106531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.-P.; Ai, Y.; Liao, D.; Correia, J.A.F.O.; De Jesus, A.M.P.; Wang, Q. Recent advances on size effect in metal fatigue under defects: A review. Int. J. Fract. 2022, 234, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wu, S.; Qian, W.; Bao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Guo, G.; Withers, P.J. The potency of defects on fatigue of additively manufactured metals. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 221, 107185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Poudel, A.; Shamsaei, N. A linear elastic finite element approach to fatigue life estimation for defect laden materials. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 285, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaş, Ö.; Kardeş, F.B.; Foti, P.; Berto, F. An overview of factors affecting high-cycle fatigue of additive manufacturing metals. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2023, 46, 1649–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimark, O.; Oborin, V.; Bannikov, M.; Ledon, D. Critical dynamics of defects and mechanisms of damage-failure transitions in fatigue. Materials 2021, 14, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Basaran, C. A review of damage, void evolution, and fatigue life prediction models. Metals 2021, 11, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgerdi, J.N.; Jaberi, O.; Remes, H.; Lehto, P.; Toudeshky, H.H.; Kuva, J. Fatigue damage process of additively manufactured 316 L steel using X-ray computed tomography imaging. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 70, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, A. Fatigue crack growth simulation by extended finite element method: A review of case studies. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 1819–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horňas, J.; Běhal, J.; Homola, P.; Senck, S.; Holzleitner, M.; Godja, N.; Pásztor, Z.; Hegedüs, B.; Doubrava, R.; Růžek, R.; et al. Modelling fatigue life prediction of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V samples using machine learning approach. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 169, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, R. Comparative analysis of support vector machine, random forest and k-nearest neighbor classifiers for predicting remaining usage life of roller bearings. Informatica 2024, 48, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Akebono, H.; Sugeta, A.; Hayashi, Y. Machine-learning-based investigation into the effect of defect/inclusion on fatigue behavior in steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 155, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiea, M.A.; Reda, R.; Ataya, S.; Ibrahim, M. Explainable AI and Feature Engineering for Machine-Learning-Driven Predictions of the Properties of Cu-Cr-Zr Alloys: A Hyperparameter Tuning and Model Stacking Approach. Processes 2025, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Long, T.; Yang, J.; Cao, R.; Guo, Y. An interpretable stacking ensemble model for high-entropy alloy mechanical property prediction. Front. Mater. 2025, 12, 1601874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jabeur, S.; Stef, N.; Carmona, P. Bankruptcy prediction using the XGBoost algorithm and variable importance feature engineering. Comput. Econ. 2023, 61, 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: A comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Rehman, M.U.; Tayara, H.; Zou, Q.; Chong, K.T. XGBoost framework with feature selection for the prediction of RNA N5-methylcytosine sites. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 2543–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Choi, S.-Y. Baltic dry index forecast using financial market data: Machine learning methods and SHAP explanations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM E8/E8M-15a; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Alabi, R.O.; Elmusrati, M.; Leivo, I.; Almangush, A.; Mäkitie, A.A. Machine learning explainability in nasopharyngeal cancer survival using LIME and SHAP. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamsyah, N.; Budiman, B.; Yoga, T.P.; Alamsyah, R.Y.R. Xgboost hyperparameter optimization using randomizedsearchcv for accurate forest fire drought condition prediction. J. Pilar Nusa Mandiri 2024, 20, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Data | Output Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax | Smax | Sarea | P | k | ||

| 1 | 222 | 2349 | 2106 | 375.8 | 0.05 | 3 |

| 2 | 62 | 1782 | 1818 | 252 | 0.01 | 2.49 |

| … | ||||||

| 299 | 657 | 3584.43 | 2111.5 | 378.41 | 0.15 | 2.62 |

| 300 | 1068 | 2677.89 | 2130.48 | 332.68 | 0.24 | 2.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, T.; Lv, S. Study on the Mechanism and Interpretability of Defect Features on Fatigue Damage in 6061 Aluminum Alloy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413021

Zhang Y, Yang Y, Chen H, Zhang R, Zhou T, Lv S. Study on the Mechanism and Interpretability of Defect Features on Fatigue Damage in 6061 Aluminum Alloy. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413021

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu, Yali Yang, Hao Chen, Ruoping Zhang, Tianjun Zhou, and Shusheng Lv. 2025. "Study on the Mechanism and Interpretability of Defect Features on Fatigue Damage in 6061 Aluminum Alloy" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413021

APA StyleZhang, Y., Yang, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, R., Zhou, T., & Lv, S. (2025). Study on the Mechanism and Interpretability of Defect Features on Fatigue Damage in 6061 Aluminum Alloy. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413021