Abstract

The processes occurring inside a spiral jet mill are significantly influenced by the flow conditions within the grinding chamber. As part of this work, an experimental 3D model of the grinding gas flow is successfully developed for the first time based on the results of PIV measurements. This model demonstrates the typical spiral vortex flow superimposed by the nozzle jets, as well as the characteristic comminution and classifying zones. In addition, the three-dimensional analysis of the nozzle jet enables the first experimental validation of the theoretical assumption proposed in the literature that the flow dynamics in this region can be described by Abramovich’s nozzle jet model. The vortex pair located on the back of the nozzle jet essentially contributes to the formation of the kidney-shaped flow cross-section of the nozzle jet. The two vortices are verified both by the flow dynamics based on the unloaded grinding gas flow and by observing the abrasion on the inner wall of the grinding chamber caused by the particle-loaded flow. Consequently, the experimental findings can be utilized to create a model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet, thereby providing a profound understanding of the flow processes within a spiral jet mill, particularly in the region of the nozzle jets.

1. Introduction

Spiral jet mills have a wide range of applications, especially in the pharmaceutical, chemical, and pigment industries, where the final product requires particle sizes below 5 to 10 µm [1,2]. The configuration of the nozzles at an inclined angle and the central product outlet generate a complex, highly turbulent flow field within the flat-cylindrical grinding chamber [3]. According to Kürten and Rumpf [1], the flow field consists of a basic spiral vortex flow that is superimposed and disturbed by the nozzle jets. Consequently, the grinding process in spiral jet mills is combined with a simultaneous classifying process, so that the achievable grinding fineness is not solely determined by the grinding performance in the nozzle jet region, but also by the efficiency of the classification in the region surrounding the product outlet [1,2,4]. The two processes are both significantly defined by the flow conditions within the grinding chamber. In particular, due to their extremely high energy consumption, spiral jet mills still offer considerable potential for sustainable optimization, highlighting the crucial need to examine the occurring flow fields in greater detail, as these are still not fully understood [5].

In terms of fluid mechanics, the basic flow can be described in a simplified manner by the frictionless and isoenergetic model of the vortex sink characterized by a potential flow consisting of logarithmic spirals. The vortex sink arises from the superposition of the potential vortex, creating a centrifugal force and the potential sink, causing a drag force towards the outlet. Therefore, the flow is significantly influenced by the circumferential and radial velocities [6].

In the individual sectional planes within the grinding chamber, different flow conditions deviating from the basic spiral vortex flow occur as a result of the suction effect of the nozzle jets that enter the grinding chamber at high velocity and the friction phenomena in the region close to the walls [7]. These deviating flow fields can basically be described by the three-level model proposed by Kürten and Rumpf [4] based on their experimental qualitative flow investigations in a water-operated spiral jet mill that was selectively colored with ink. In the outer region of the grinding chamber, the flow at nozzle height (level III) is determined by the nozzle jets and their deflection by the spiral vortex flow or by the adjacent nozzle jets, depending on the nozzle number and angle. On the contrary, the flow below and above the nozzle height (level II) is characterized by backflows in the form of flat spirals toward the peripheral grinding chamber wall, which occur for continuity reasons as a result of the suction effect of the nozzle jets, whereas in the inner region of level II and III, the grinding gas flows in a flat spiral toward the product outlet in the center of the spiral jet mill. In contrast to these two main flow levels, a boundary layer forms at the front walls at the bottom and cover of the spiral jet mill (level I), in which the grinding gas flows directly from the outer region to the outlet in a steep spiral due to wall friction.

Bauer [8] extended the three-level model at the main flow levels II and III by adding a radial subdivision of the spiral jet mill into the outer nozzle jet zone (comminution zone), which is delimited by the nozzle jets, and the inner vortex sink zone (classification zone).

The increasing velocity from the outside to the inside of the mill in the vortex sink zone has already been confirmed at the main flow levels II and III by the experimentally determined radial profile of the static pressure within the grinding chamber by Muschelknautz et al. [1] and Bauer [8], as well as later by Rief [9], Marquardt [10] and Hagendorf [11]. Hagendorf [11] and Fulga and Strajescu [12] were also able to prove the increased flow velocities in the nozzle jet zone and the typical spiral vortex flow by the additional measurement of the total pressure of the unloaded grinding gas flow. Similar velocity profiles have also been observed when different anemometers were used for experimental flow investigation, as reported in the studies of Muschelknautz et al. [1], Bauer [8], and Kushimoto et al. [13]. However, the backflows on level II could not yet been experimentally verified. Through qualitative observation of the streamlines in the boundary layer at the bottom of the mill, Bauer [8] was able to confirm the steep spiral flow at level I.

The methods outlined for the indirect measurement of flow velocities through the use of pressure sensors and anemometers only provide information about the local velocity at the specific position under consideration and concurrently influence the flow and the grinding gas properties due to the necessary installation of the measuring instruments within the grinding chamber. The laser-optical method of particle image velocimetry (PIV), which allows the complete measuring equipment to be positioned outside the flow, offers a significantly more appropriate alternative for the experimental investigation of the flow conditions inside spiral jet mills. By applying this method for the direct measurement of flow velocities, Luczak et al. [14,15,16] and Radeke et al. [17,18] determined the entire two-dimensional velocity fields at three different grinding chamber levels of a spiral jet mill, which show and confirm the typical spiral vortex flow superimposed by the nozzle jets, as well as the division of the cross-section into the comminution and classification zone. However, due to the limited spatial resolution, these results do not provide any information about how the flow between the 2D velocity fields under consideration proceeds. Nevertheless, this method is unique worldwide and remains the only opportunity for comprehensive experimental determination of the flow velocities inside the grinding chamber of spiral jet mills to date.

All other studies presenting entire three-dimensional flow fields of spiral jet mills corresponding qualitatively with the experimental findings are based on CFD- [19,20,21] or CFD-DEM simulations [13,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], whose numerical flow results have not yet been comprehensively validated through experimental data. Yu et al. [21] lately calculated the gas flow velocities in the grinding chamber using large eddy simulation (LES), while recent studies of Sabia et al. [20,31,32] deal with the development of a novel uncoupled quasi-3D Euler–Euler model for describing the grinding process in a large industrial spiral jet mill based on a detailed CFD simulation of the single-phase gas flow and subsequent calculation of the radial particle velocities using a 1D compartmentalized model. Conversely, Kushimoto et al. [13] investigated the flow behavior of the grinding gas and the solid particles within the grinding chamber by using CFD-DEM simulation through a one-way coupling method, whereas Yu et al. [28] employed the same method to calculate the flow in the feed pipe of a spiral jet mill. In contrast, the CFD-DEM simulation in recent studies by Scott et al. [29,30] and Bna et al. [27] has been performed with a four-way-coupling method, applying coarse-graining and taking into account the particle breakage in order to characterize the entire grinding process in a spiral jet mill. Other recent studies that did not consider any flow conditions in the grinding chamber focused instead on conventional grinding experiments, as described in the works of Dhakate et al. [33,34,35], Deng et al. [36] and Bultereys et al. [37]. In addition, certain of these results have been used to develop a population balance model (PBM) based on breakage functions to provide a mathematical description of the grinding process in spiral jet mills.

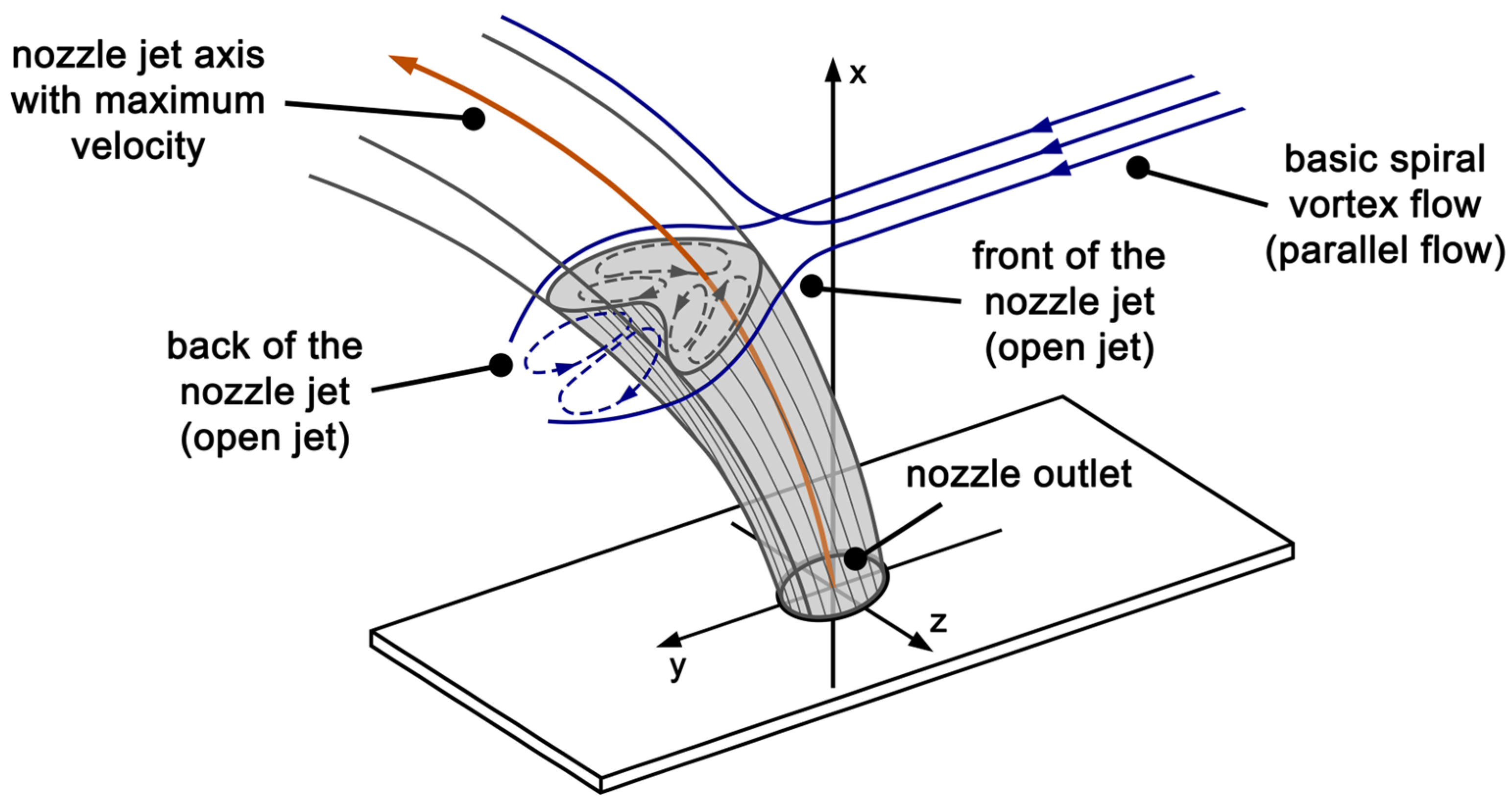

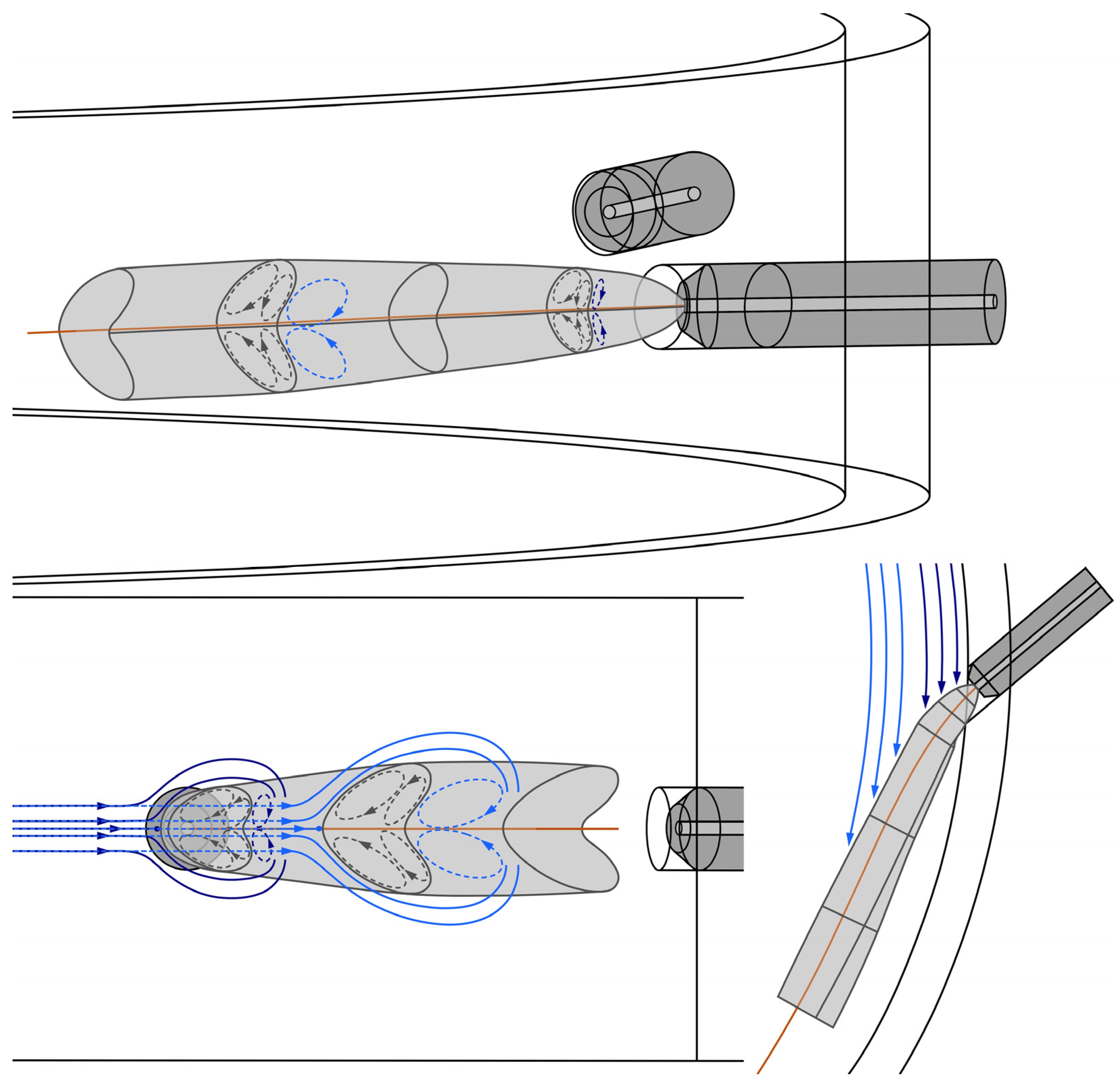

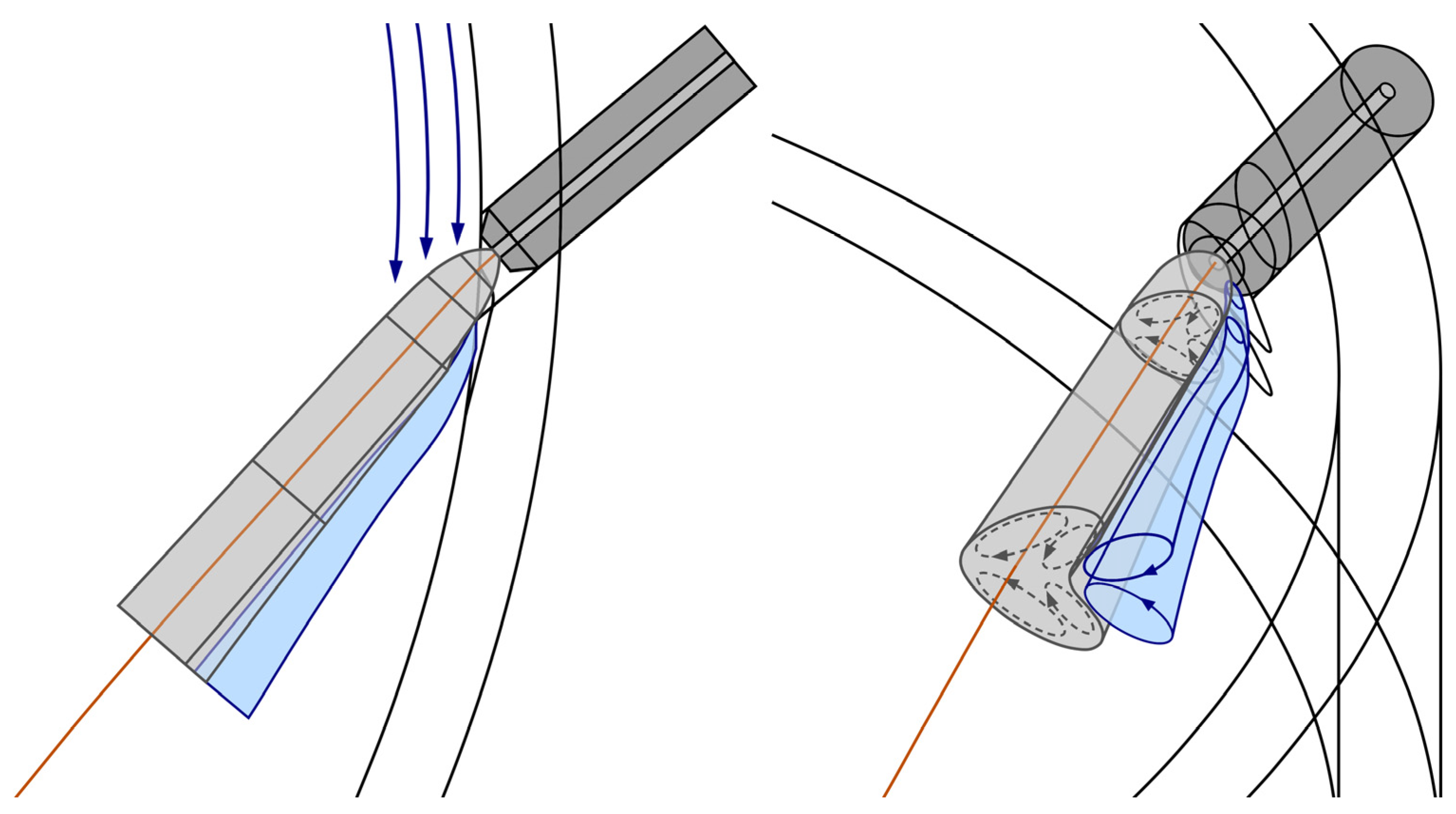

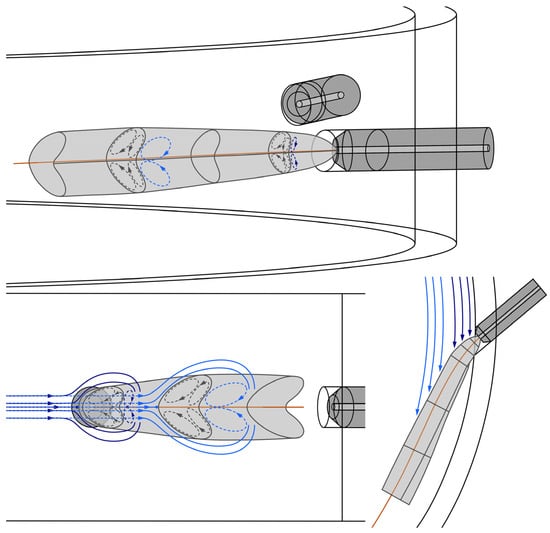

As previously outlined, the flow conditions in spiral jet mills are significantly influenced by the nozzle jets entering the grinding chamber at high velocity. In accordance with Kürten und Rumpf [4], the flow in this region can basically be described by Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38], as shown in Figure 1. This model is based on the experimental investigation of an open jet that is encountered and deflected by a parallel flow perpendicular to the nozzle axis. The basic spiral vortex flow in the grinding chamber, representing the parallel flow, is decelerated and redirected by the incoming nozzle jet, since its momentum at the nozzle outlet is significantly greater than the momentum of the basic flow. This creates an overpressure region on the front of the nozzle jet in the surroundings of the stagnation point, while large velocity gradients and thus high shear forces exist at the sides of the nozzle jet due to the redirected flow. On the back of the nozzle jet, the flow separates, creating a region of negative pressure with a wake zone. This results in two counter-rotating vortices and thus strong turbulence, which are not carried away by the basic spiral vortex flow but are entrained by the nozzle jet due to its significantly greater momentum.

Figure 1.

Model of the encountered and deflected open jet according to Abramovich, adapted to the nozzle jet in a spiral jet mill (illustrated model adapted from [4,38]).

As a consequence of the negative pressure that is accompanied by a strong suction effect and the flow of the vortex-pair, the nozzle jet preferentially aspirates grinding gas from the main flow on its back. In addition, this also induces an internal circulation and thus a strong mixing inside the nozzle jet flow. Due to the influence of the pressure field and the lateral shear forces, increasing distance from the nozzle outlet not only causes a deflection of the nozzle jet in the direction of the basic spiral vortex flow, but also a deformation of the initial circular jet into a kidney-shaped flow cross-section. Therefore, according to Bauer [8], the flow conditions are modified so that the flow resistance increases as the jet deforms more intensely.

Both the stagnation zone in front of the nozzle jet and the redirection of the surrounding basic spiral vortex flow, as well as the turbulence on the back of the nozzle jet, have been experimentally confirmed by observing the streamlines in the boundary layer of the peripheral wall by Kürten and Rumpf [4] and by Strajescu and Fulga [39], at least in the immediate vicinity of the nozzle outlet. However, the actual flow pattern of the nozzle jet in the basic flow of the spiral jet mill, as well as its deformation and the kidney-shaped cross-section, could not yet be experimentally or numerically verified. Consequently, despite their significant influence on the processes inside the grinding chamber, the precise flow field within the nozzle jet region remains unknown.

Nevertheless, based on Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38] transferred to the one in a spiral jet mill, Kürten and Rumpf [4] explained the results of their grinding investigations with triboluminescent materials [40] and the fact that the comminution preferably takes place on the back of the nozzle jets, provided that the loading of the grinding material in the mill is not too high. As a result of the negative pressure and the flow of the vortex-pair, the solid particles can easily penetrate the nozzle jet in this region, causing high relative velocities between the particles already accelerated in the jet direction and those just entering the nozzle jet. This substantially increases the probability of particle–particle collisions that actually lead to breakage on the back of the nozzle jet. Moreover, Bauer [8] developed a model to calculate the internal circumferential velocity and the cut size diameter, which is based on the model of the encountered and deflected open jet and the jet expansion theory according to Abramovich [38] in the comminution zone.

The aim of this work is to extend the experimental determination of flow fields using PIV, based on the investigations by Luczak et al. [14,15,16] and Radeke et al. [17,18], to further levels within the grinding chamber in order to develop a three-dimensional model of the grinding gas flow based on experimental data for the first time. This should provide a better understanding of the flow processes both in the radial and height-dependent velocity profile and, in particular, in the region of the nozzle jets that has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive analysis in the literature. Although it is currently assumed that the comminution occurs on the back of the nozzle jets, Abramovich’s model, on which this assumption is primarily based, has not yet been proven either experimentally or numerically, highlighting the novelty of the problem. For this reason, in addition to the development of an experimental 3D model, this study focuses particularly on the investigation of the flow conditions in the immediate surroundings of the nozzle jet.

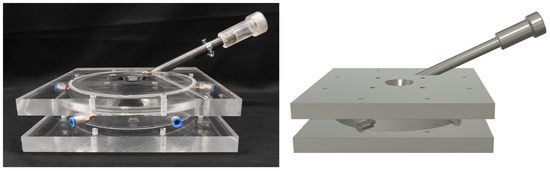

2. Materials and Methods

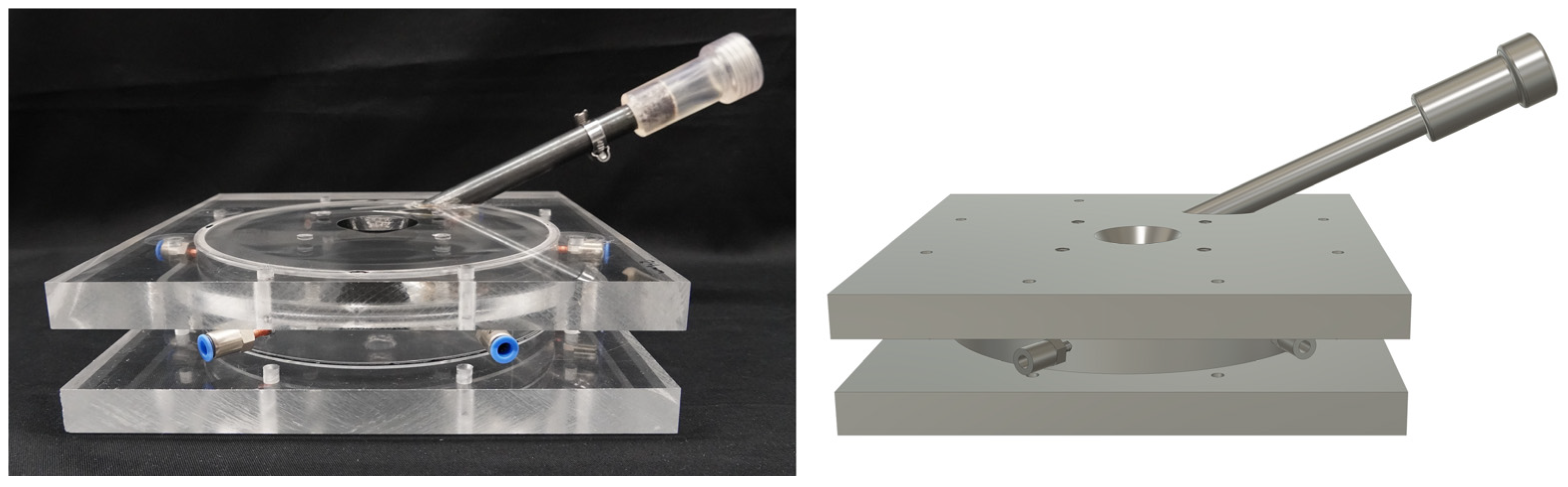

The experimental investigation of the flow conditions inside the spiral jet mill is performed by applying Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV). This non-invasive laser optical measurement method enables the analysis of the two-dimensional velocity fields at different levels within the grinding chamber (planar PIV). For this purpose, a scale-down model of an industrial spiral jet mill with a grinding chamber diameter of 190 mm and a grinding chamber height of 24 mm is used. This model is made of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) for the most part and, therefore, almost completely optically accessible (see Figure 2). This characteristic is a mandatory requirement for the application of PIV. The considered mill configuration in this work has a product outlet diameter of 24 mm and is equipped with 6 convergent-cylindrical nozzles at medium height with a minimum diameter of 0.8 mm and a radial angle of 40°.

Figure 2.

Spiral jet mill made of PMMA (left) and corresponding CAD model (right).

Prior to its entry into the spiral jet mill, the compressed air utilized as grinding gas is divided into two separate gas flows in order to supply both the nozzles of the grinding ring and the injector. A calorimetric mass flow sensor (Inline Flow Sensor VA 520, CS Instruments GmbH & Co. KG, Villingen-Schwenningen Tannheim, Germany) and a digital pressure gauge (Baroli 05, BD Sensors GmbH, Thierstein, Germany) have been integrated into each of the two lines to enable a precise adjustment of the respective gas mass flows ( and ) and pressures (pn and ps or pinj) using pressure reducers (DM 1/2 W, Schneider Druckluft GmbH, Reutlingen, Germany). The mass flow of the grinding ring is then evenly distributed across the installed nozzles of the spiral jet mill.

When investigating the unloaded grinding gas flow, the injector mass flow is entirely fed to a seeder (LS-10e, SCITEK Consultants Ltd., Derby, UK) that generates an aerosol of very fine diethylhexyl sebacate (DEHS, Palas GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) droplets dispersed in compressed air. The DEHS droplets function as tracer particles, thereby allowing the investigation of the grinding gas flow without particle loading. Downstream of the seeder, a further digital pressure gauge (Baroli 05, BD Sensors GmbH, Thierstein, Germany) is installed, the function of which is to measure the pressure of the aerosol (pm) before it enters the simplified injector system of the spiral jet mill and is distributed within the grinding chamber. The compressed air enriched with DEHS droplets leaves the mill via the discharge system and is subsequently fed into the exhaust air system.

Conversely, when investigating the particle-loaded grinding gas flow, the injector mass flow is directly fed to the injector nozzle of the spiral jet mill. The grinding material (calcium carbonate, CaCO3, with an average particle size of about 6.2 µm, Dr. Lohmann Diaclean GmbH, Dortmund, Germany) is conveyed into the injector funnel by a vibratory feeder (Vibri, Sympatec GmbH, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany), where it is accelerated and transported into the grinding chamber through the gas flow of the injector nozzle. In this case, the solid particles of the grinding material function as a tracer, thereby allowing the investigation of their own flow behavior inside the spiral jet mill. The particle-loaded compressed air leaves the mill through the discharge system and is separated by a filter bag (Filteron GmbH, Solingen, Germany).

The tracer particles, DEHS or CaCO3, following the grinding gas flow within the spiral jet mill are illuminated with a double-pulsed Nd:YAG laser (DualPower Nano L 135-15, Litron Lasers Ltd., Rugby, UK), which is stretched into a thin horizontal light sheet using laser optics. At the same time, double images of the grinding chamber cross-section are captured from below using a CCD camera (FlowSenseEO 4M, Dantec Dynamics A/S, Skovlunde, Denmark). Provided that the measuring area is darkened, only the particles exposed within the laser light sheet are visible on the images, enabling the flow fields to be recorded at different levels. The displacement of the tracer particles within a double image can then be used to calculate the spatially resolved velocity vectors using Dynamic Studio Version 2015a software (Dantec Dynamics A/S, Skovlunde, Denmark).

A more detailed description of the measurement method and the associated setup for investigating the flow conditions inside the spiral jet mill using PIV can be found in previous work by Radeke et al. [17,18].

In order to develop an experimental three-dimensional model of the flow, the two-dimensional velocity fields of the unloaded grinding gas are determined at different horizontal levels within the grinding chamber. The height (z) of the levels is varied at intervals of 2 mm, with the measurement commencing 1 mm above the bottom and concluding 1 mm below the cover of the spiral jet mill. In the grinding chamber region between 9 and 15 mm above the bottom, the distance between the levels is reduced to 1 mm due to the presence of the nozzle jet. The two-dimensional data exclusively encompass the flow components in the x- and y-directions, whereas the component in the z-direction cannot be represented. However, since the z-component is significantly lower due to the high tangential spiral vortex flow within the grinding chamber, the measured two-dimensional velocity fields represent a very good approximation of the actual flow conditions.

In order to enable a comprehensive comparison of the flow patterns across all levels, the measurements are conducted both under constant operating parameters, as outlined in Table 1, and with the same measurement and evaluation settings of the PIV system (time between laser pulses = 3 µs, trigger rate = 7 Hz, size of interrogation areas = 32 × 32 pixels). These settings were defined based on the results of extensive preliminary studies. A total of 300 double images are captured, whose velocity vectors are averaged to form one velocity field under the simplified assumption of steady-state conditions. Unsteady flow conditions within the grinding chamber, such as those that can occur in the region of the product outlet and the nozzle jets as a result of the high turbulent flow, cannot be represented using this method. However, a comparison of the individual velocity fields of the particular double images has previously demonstrated that the flow patterns obtained by PIV measurements remain largely constant for the mill configuration and operating parameter settings under consideration. Consequently, the flow can be assumed to be in a steady state in this study.

Table 1.

Operating parameters averaged across all levels (z = 1 to 23 mm) with standard deviation for the PIV investigations of the unloaded grinding gas flow with DEHS as tracer.

The velocity field of the particle-loaded grinding gas flow is only determined at the nozzle level, 12 mm above the bottom, in order to compare the flow conditions without and with particle loading at the most meaningful horizontal level inside the grinding chamber. The operating parameters, as well as the measurement and evaluation settings, are almost identical to those previously described and shown in Table 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Horizontal Velocity Fields of the Unloaded Grinding Gas Flow

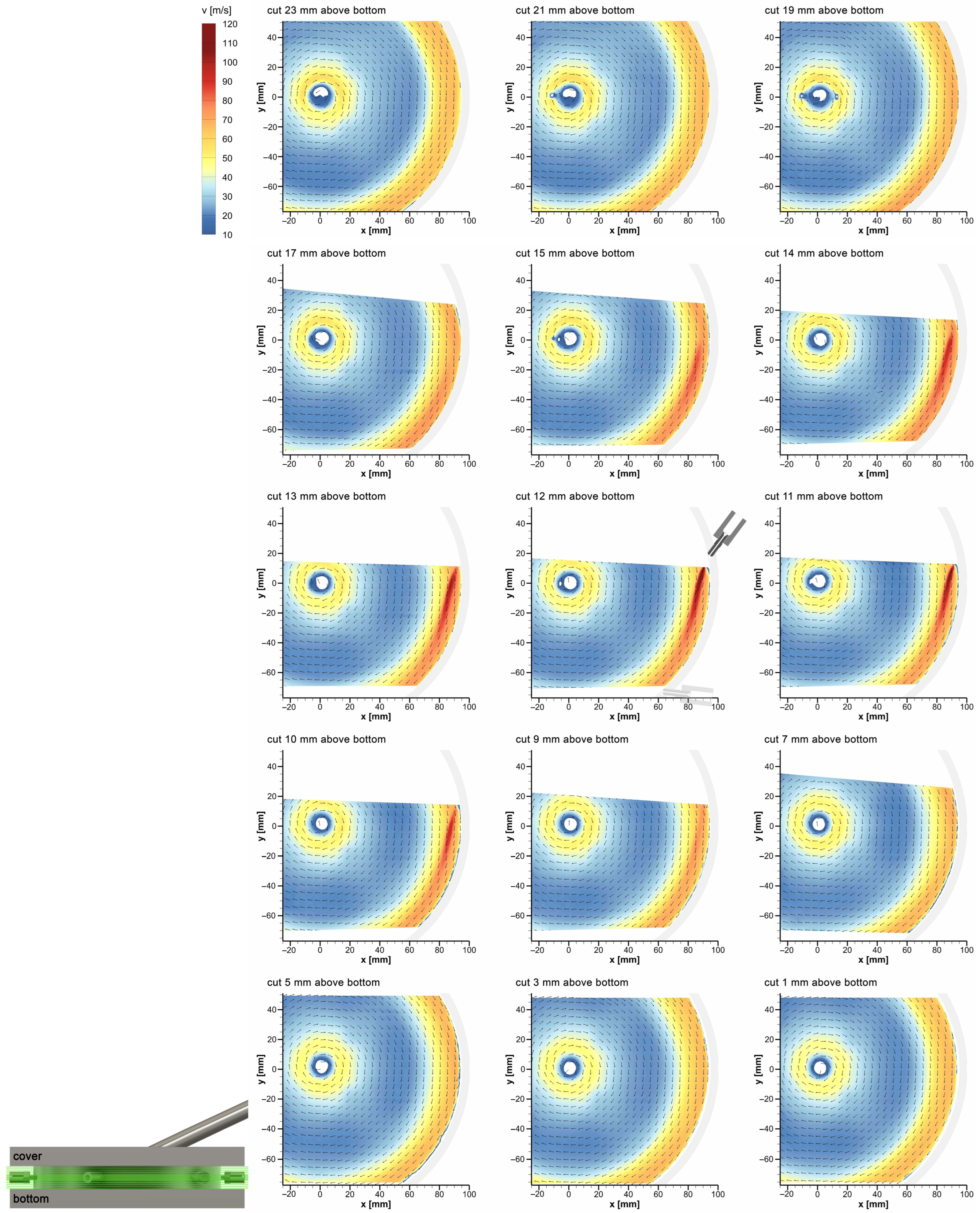

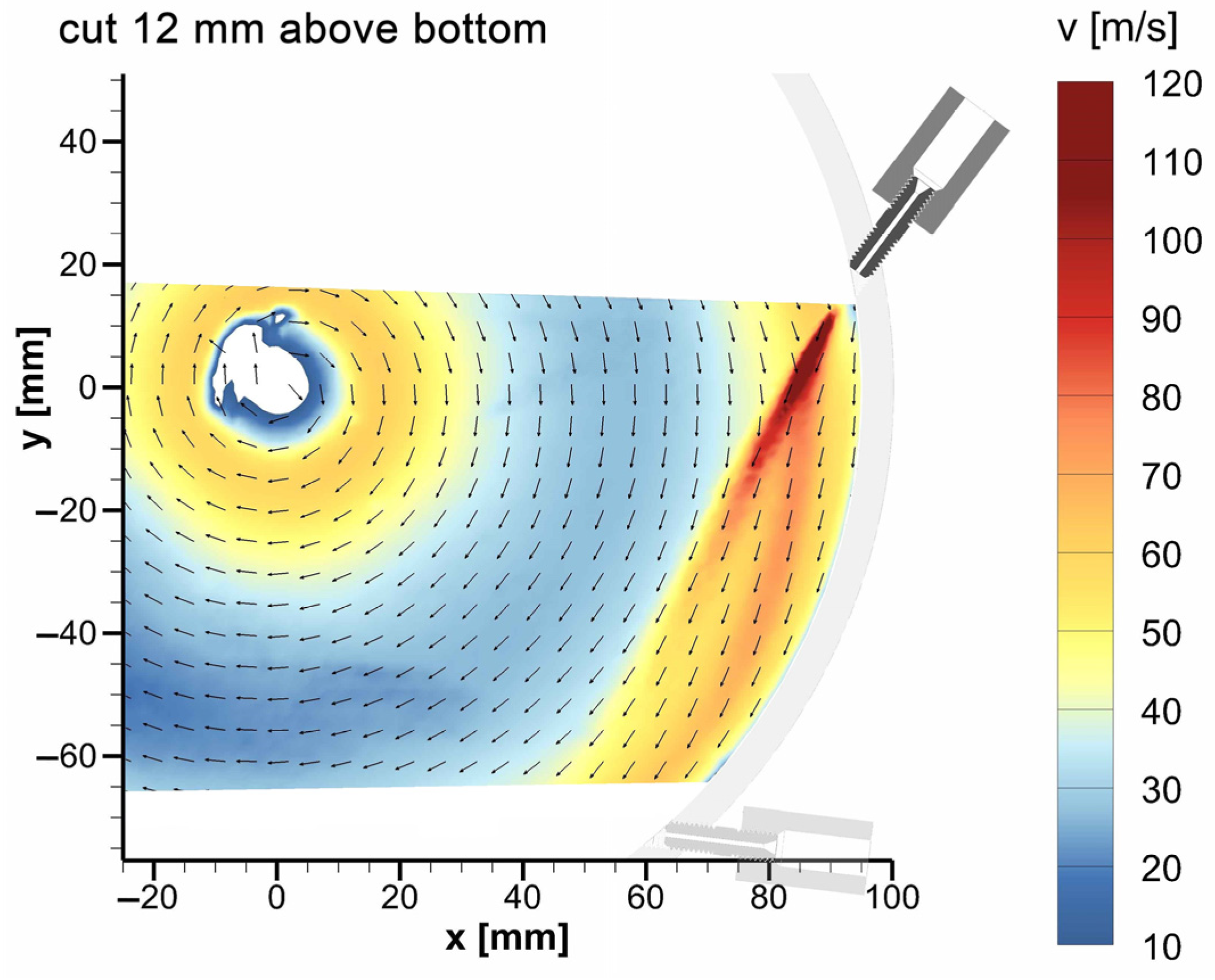

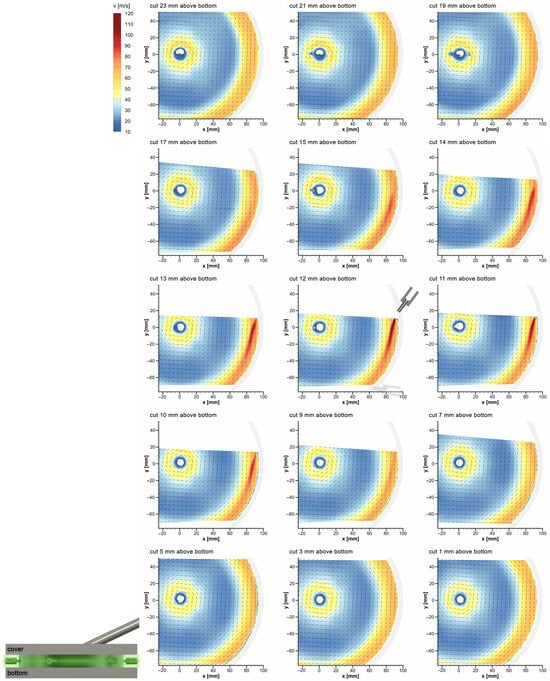

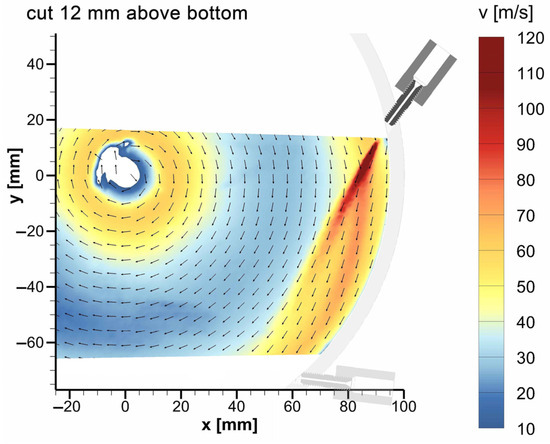

Figure 3 shows the two-dimensional velocity fields of the unloaded grinding gas flow obtained by PIV measurements at various horizontal levels within the grinding chamber. The coordinate system (x, y) is positioned in such a manner that the center of the spiral jet mill is located at point (0, 0). Each velocity field reveals the typical basic spiral vortex flow and the two regions with increased flow velocity in the comminution zone for r ≥ 70 mm and the classification zone for r ≤ 30 mm. With the exception of the nozzle jet superimposing the basic flow in the comminution zone, no substantial disparities between the various heights can be discerned in the flow fields. Only in the classification zone located within the inner region of the spiral jet mill, the velocity exhibits an increase with decreasing distance from the cover, which is particularly apparent when comparing the levels immediately below the cover and directly above the bottom. This phenomenon is attributable to the proximity to the product outlet, which necessitates that the flow of the entire grinding gas passes through the outlet cross-section. Consequently, the velocity has to increase in accordance with the continuity equation.

Figure 3.

Horizontal velocity fields of the unloaded grinding gas flow obtained by PIV measurements with DEHS as tracer—comparison of different horizontal levels within the grinding chamber at a height of z = 1 to 23 mm above the bottom, as outlined in the CAD model at the bottom left, position and orientation of nozzles are shown in image “cut 12 mm above bottom”.

The restriction of the optical accessibility of the grinding chamber, indicated by the white-covered areas within the flow fields, commences 7 mm above the bottom and concludes 7 mm below the cover. This limitation is caused by the shadow cast by the laser light behind the nozzles (cf. Figure 2). Therefore, the flow can only be partially examined in the region between the two nozzles.

As anticipated, the most intense nozzle jet with the highest velocities is recorded directly at the nozzle outlet in the flow field 12 mm above the bottom, thus precisely at the medium height of the grinding chamber. Since the unloaded grinding gas flow without particles is analyzed here, the nozzle jet experiences significant deflection by the basic spiral vortex flow upon its entry into the grinding chamber. As the distance from the horizontal nozzle level at medium height increases, the nozzle jet core undergoes a further shift in the direction of the flow, accompanied by a decrease in intensity. This phenomenon is evident in the flow fields located in the immediate surroundings of the nozzle level between 10 and 14 mm above the bottom. However, the direct impact of the nozzle jet due to its expansion still remains discernible 3 mm below and above the nozzle outlet at the levels between 9 and 15 mm above the bottom.

A qualitative comparison of the experimental results obtained in this study (cf. Figure 3) with the numerical velocity fields of the grinding gas flow calculated by CFD simulation for a similar nozzle angle of 45° presented in the work of Bna et al. [27] shows a good agreement of the data at the nozzle level, especially in the comminution zone and the region of the nozzle jets. However, in the classification zone, the numerical data differ significantly due to the completely different geometry of the product outlet being equipped with two classifier rims. In contrast, the numerical results of Kushimoto et al. [13] obtained by CFD simulation for the same nozzle angle of 45° show a relatively good agreement with the experimental results in the inner region of the mill, but deviate clearly from the numerical data of Bna et al. [27] and the experimental data in the comminution zone, especially in the region of the nozzle jets. A quantitative comparison of the results is not presented, as both the geometric and operating parameters differ significantly from each other.

3.2. Development of the 3D Model

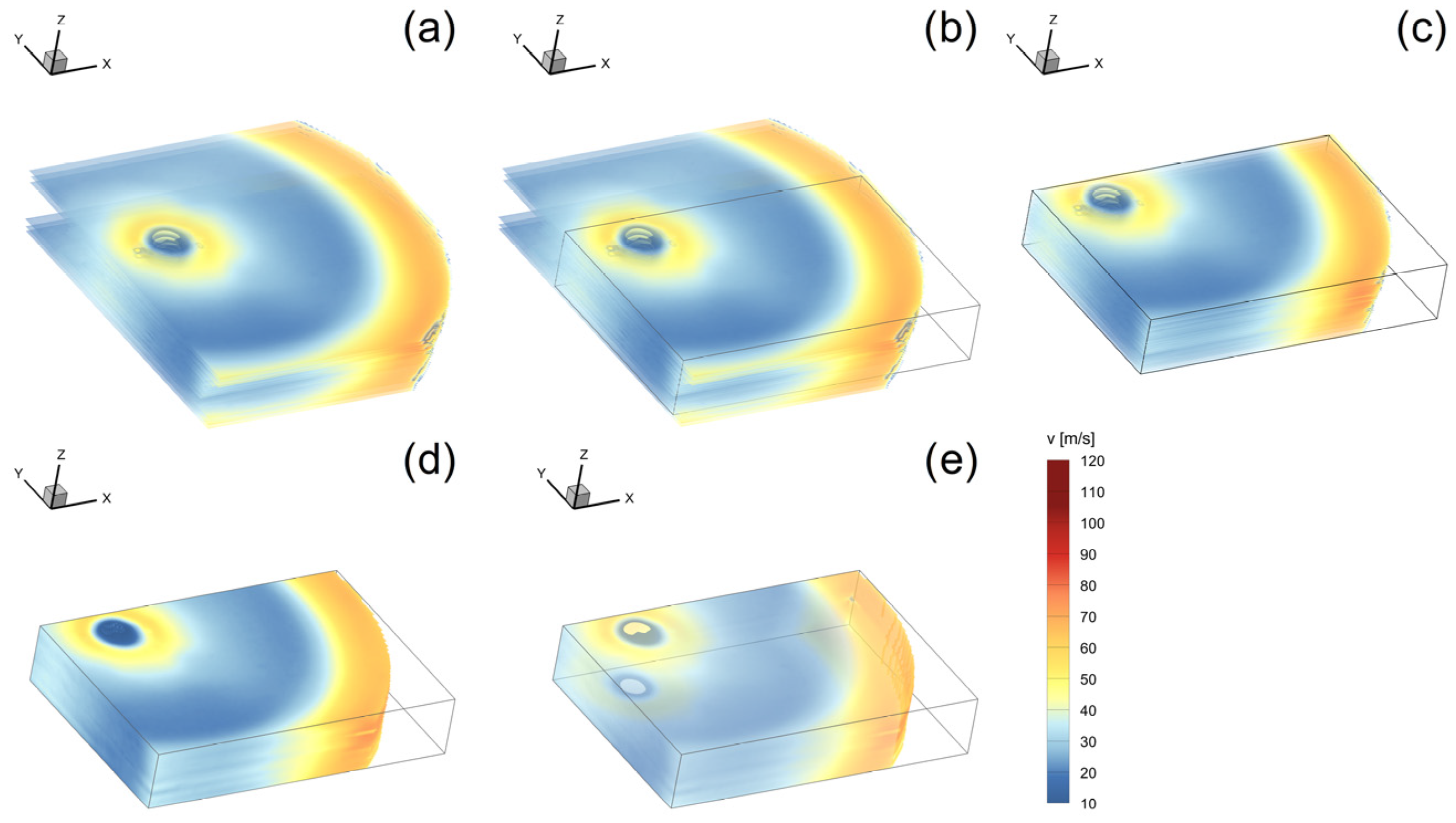

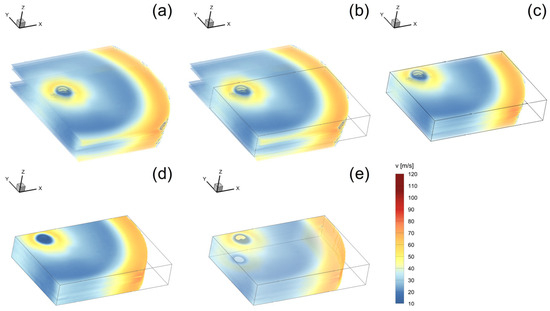

The two-dimensional velocity data obtained by PIV measurements, being available on 15 horizontal levels, is used to generate a three-dimensional model of the unloaded grinding gas flow in the spiral jet mill that almost completely reproduces the flow conditions in the grinding chamber.

For this purpose, the z-coordinate, defined as the height of the corresponding level, is initially incorporated into the two-dimensional data sets so that the velocity fields from Figure 3 can be represented in three-dimensional space, as illustrated in Figure 4a. Subsequently, the bounding box is determined (see Figure 4b), which encompasses the maximum area of the grinding chamber cross-section in the x- and y-direction, for which meaningful velocity data is available on all levels under consideration. The data outside the confines of the bounding box is deemed unsuitable for the generation of the 3D model due to its incompleteness. Consequently, this data is concealed, as shown in Figure 4c. The flow immediately at the bottom and cover of the grinding chamber (z < 1 mm and z > 23 mm) cannot be experimentally measured or covered by interpolation. In addition, the flow dynamics in this region are already influenced by the specific conditions of the walls, therefore, extrapolating beyond the data sets is not useful. For these reasons, the flow in the region proximate to the walls cannot be taken into account in this study. After defining the dimensions of the bounding box, a corresponding solid body is generated in which the flow velocities between the discrete horizontal levels are completely calculated using the inverse distance interpolation method. Figure 4d,e illustrates the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow created by interpolating between the experimentally examined flow fields. The region for r > 95 mm is concealed within the bounding box, as it is located outside the grinding chamber.

Figure 4.

Development of the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow—experimentally determined velocity fields by PIV measurements (a), definition of the bounding box (b), concealing unsuitable measurement areas (c), calculation of the flow velocities throughout the entire volume of the bounding box using inverse distance interpolation (d) and final 3D model based on experimental data with partially transparent representation of visible surfaces (e).

In the context of the 3D model analysis, it is imperative to take into account that the data under consideration exclusively encompasses the flow components in the x- and y-direction. The component in the z-direction, which is relevant for the discharge of the grinding gas and the particles from the spiral jet mill, cannot be represented. However, since the components in the x- and y-direction are significantly larger than the z-component, due to the spiral vortex flow within the grinding chamber and the associated high tangential component of the flow, the calculated 3D model still represents a very good approximation of the actual flow conditions.

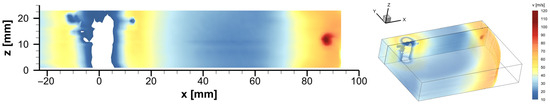

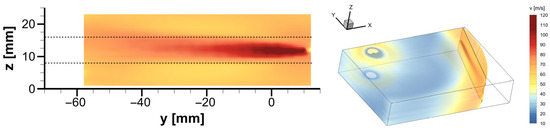

3.3. Vertical Velocity Fields and Profiles of the Unloaded Grinding Gas Flow

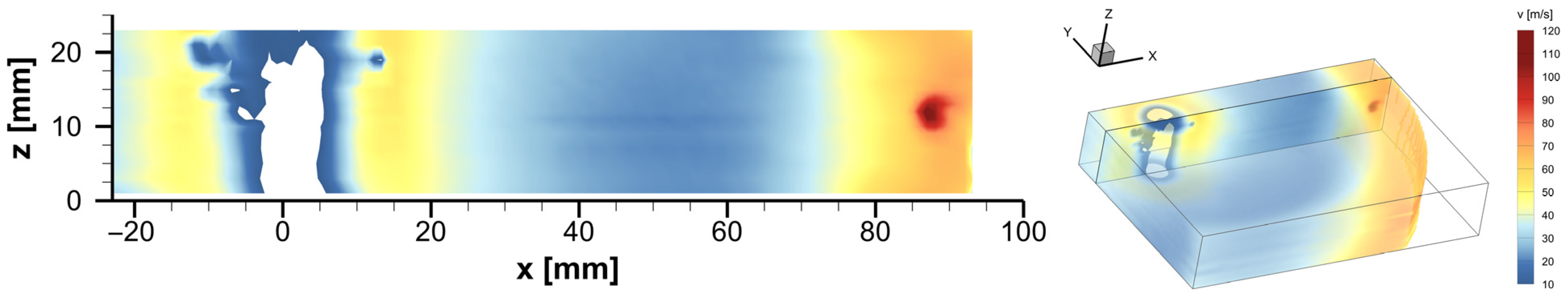

In order to describe the three-dimensional flow in the spiral jet mill more precisely, a vertical velocity section at y = 0 mm is extracted from the experimental 3D model in Figure 4, as illustrated in Figure 5. The section reveals an almost rotationally symmetric cylindrical classification zone, whose maximum flow velocity, as previously mentioned, increases with decreasing distance from the product outlet of the mill due to the consequences of the continuity equation. Moreover, a closer inspection of the flow discloses a slight enlargement of the classification zone with increasing proximity to the cover, attributable to the same underlying reasons. Within the classification zone, a channel is formed through which the grinding gas flows towards the product outlet, subsequently exiting the mill. As previously explained, the flow in the z-direction cannot be represented in this study, signifying that the velocity in this channel is close to zero in the 3D model.

Figure 5.

Vertical velocity field at y = 0 mm extracted from the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow based on experimental data—two-dimensional view (left) and visualization in the 3D model (right).

The inner region of the classification zone, characterized by increased flow velocities, verges on the ring-shaped flow-calmed region that represents a clear delimitation from the comminution zone in the outer area of the mill due to its low flow velocities.

A closer look at the velocity field depicted in Figure 5 reveals that the similarly ring-shaped comminution zone exhibits a slightly concave boundary that extends to the flow-calmed region. Concurrently, the velocity increases as the distance from the peripheral grinding chamber wall decreases. The nozzle jet appears as a local circular increase in velocity at the medium height of the spiral jet mill, with the maximum flow velocity being attained at its center. However, a thorough examination of the nozzle jet shape indicates that the contour of the back of the jet oriented to the peripheral grinding chamber wall is not circular, but has a slightly kidney-shaped form, whereas the maximum velocity is located further towards the front of the nozzle jet.

The concave boundary between the comminution zone and the flow-calmed region is created by two flow phenomena that occur as a result of the nozzle jet entering the grinding chamber. On the one hand, a stagnation zone arises on the front of the nozzle jet due to the deceleration of the basic spiral vortex flow while encountering the nozzle jet. Consequently, the velocities at the medium height of the spiral jet mill in the region of the nozzle jet are slightly reduced compared to those towards the bottom and cover of the mill, where the basic flow can develop without disruption. In addition, the stagnation zone contributes to the positioning of the maximum velocity in the nozzle jet core, which is located further towards the front. On the other hand, the nozzle jet entering the grinding chamber with a very high velocity induces a substantial suction effect, which aspirates grinding gas from the entire surrounding region. Therefore, the velocity vectors of the horizontal flow field under consideration, oriented along the basic tangential flow and the nozzle jet, are to a certain extent compensated by the flow vectors of the grinding gas aspirated from the surrounding region, thereby resulting in a slight reduction in the flow velocity in this region. Due to the stagnation zone and the suction effect of the nozzle jet, the boundary between the comminution zone and the flow-calmed region is thus slightly distorted, causing it to transition into a concave shape.

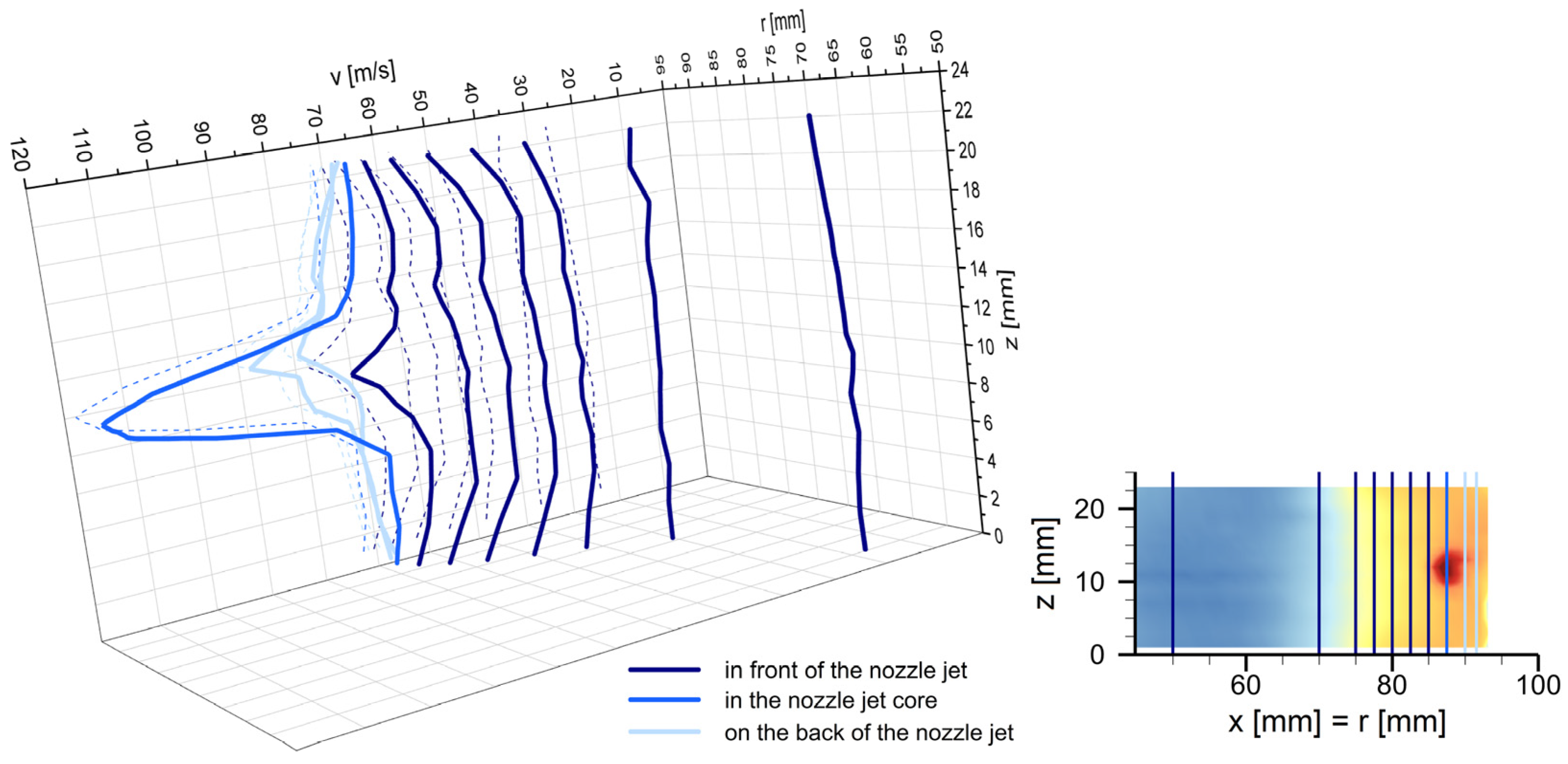

This phenomenon is also reflected in the height-dependent velocity profiles shown in Figure 6 at selected radial positions within the grinding chamber, which have been extracted from the vertical velocity field at y = 0 mm in Figure 5. In the flow-calmed region for a radius of r ≤ 70 mm, the flow velocity remains almost constant regardless of the height-dependent position z. In front of the nozzle jet, at a radius of r ≥ 75 mm, the nearly constant profile is distorted, with the flow velocity increasing equally toward the bottom and cover of the spiral jet mill. The velocity difference between the grinding chamber walls and the nozzle height increases as the distance from the nozzle jet decreases. Conversely, at the radial position of the nozzle jet core, as well as on the back of the nozzle jet, at a radius of r ≥ 87.5 mm, the immediate increase in velocity and the acceleration of the entire flow in the outer region of the comminution zone due to the nozzle jets predominate as a result of the relatively large radial nozzle angle of 40° considered in this study. Consequently, the velocity profile toward the bottom and cover of the spiral jet mill remains nearly constant or decreases slightly.

Figure 6.

Height-dependent velocity profile at selected radial positions for r ≥ 50 mm extracted from the vertical velocity field at y = 0 mm, shown in Figure 5 (positions in the vertical velocity field at which the data have been extracted are outlined in the detailed view of Figure 5 at the bottom right).

3.4. Grinding Gas Flow in the Nozzle Jet Region

As the flow in the region of the nozzle jet primarily influences the comminution process in the spiral jet mill, the increased velocities of the nozzle jet and its three-dimensionality, as previously established in Figure 3 and Figure 5, will be examined more precisely in the following sections.

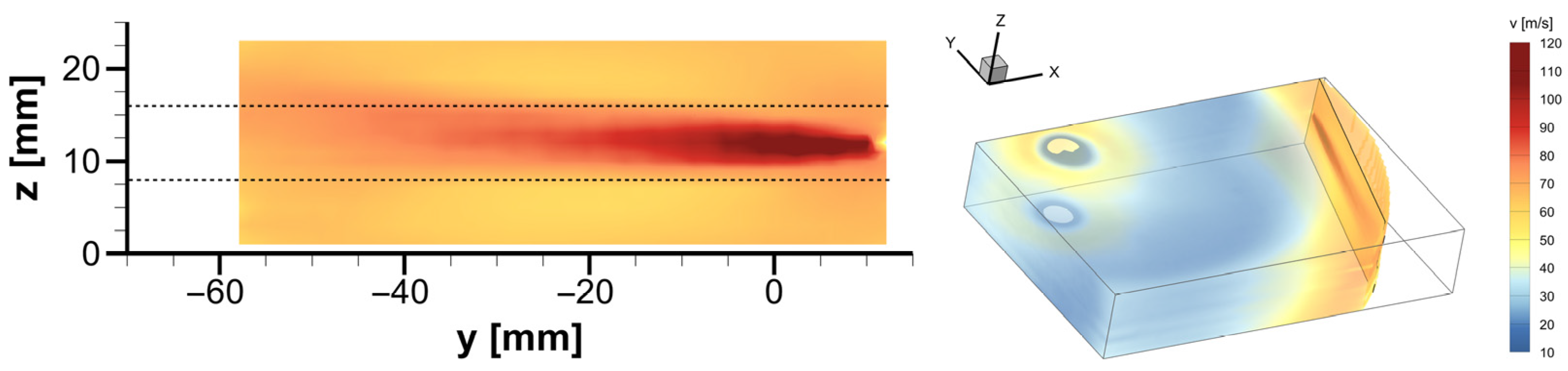

For this purpose, an oblique vertical velocity section in the core of the nozzle jet in the flow direction is extracted from the experimental 3D model in Figure 4, as illustrated in Figure 7. The flow field reveals that the nozzle jet expands immediately after entering the grinding chamber, thereby increasing its flow cross-section as well as its velocity. However, as the distance from the nozzle outlet increases further, the flow velocity decreases again until the jet eventually merges with the basic spiral vortex flow of the comminution zone.

Figure 7.

Velocity field in the core of the nozzle jet in the flow direction extracted from the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow based on experimental data (dotted lines indicate the nozzle jet’s region of influence)—two-dimensional view (left) and visualization in the 3D model (right).

The evident expansion of the nozzle jet is attributable to the fact that the flow behind the nozzle outlet is supercritical due to the high nozzle inlet pressure. Consequently, the pressure in the jet at the outlet of the nozzle is greater than the ambient pressure within the grinding chamber, resulting in a local pressure gradient. Therefore, when the grinding gas flow exits the nozzle into the grinding chamber, components of the flow deviating from the direction of the outflow axis emerge. These components lead to a bursting of the nozzle jet and subsequent oscillations, thereby giving rise to unsteady flow conditions [41]. The pressure in the nozzle jet equalizes with the ambient pressure in the grinding chamber and the flow expands. By reason of the unsteady conditions, an increased energy loss occurs due to friction, causing the flow velocity to decrease sharply with increasing distance from the nozzle outlet, so that the nozzle jet finally merges with the basic spiral vortex flow. However, the jet oscillations are not visible in the experimental flow fields in Figure 3 and Figure 7, as they probably arise irregularly and, consequently, cannot be represented in the averaged steady-state velocity fields. The visibility of such unsteady flow conditions in the PIV results depends strongly on the time and spatial resolution of the measurement, as well as on the position and orientation of the considered level, rendering their detection particularly challenging.

Figure 8 presents a selection of streamlines at different heights within the grinding chamber, illustrated in front of the velocity field in the nozzle jet core shown in Figure 7. The streamlines were extracted from the 3D model by tracking the paths of massless tracer particles placed in the flow, provided that the velocity vector field fulfills the steady-state condition. In order to emphasize the nature of the flow, the streamlines are located at four positions in the immediate surroundings of the nozzle jet and two positions towards the cover and the bottom, where the flow is not directly influenced by the nozzle jet. The expansion of the nozzle jet is discernible by the increasing distance in the flow direction between the four streamlines at the medium height of the spiral jet mill. Additionally, the suction effect of the nozzle jet, through which the grinding gas is aspirated from the surrounding region, can be suspected from the lowest of the four streamlines, as it originates in the region below the nozzle jet. The two streamlines above and below the nozzle jet, close to the bottom and cover of the mill, however, completely follow the tangential basic spiral vortex flow in the comminution zone. The nozzle jet’s region of influence is thus confined to a specific location above and below the nozzle outlet and extends to approximately 10 times the nozzle diameter with respect to the grinding chamber height (z = 8–16 mm) in the considered case, as indicated in Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Selected streamlines at different heights of the grinding chamber extracted from the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow by path tracking of massless tracer particles (streamlines illustrated in front of the velocity field in the core of the nozzle jet in the flow direction from Figure 7).

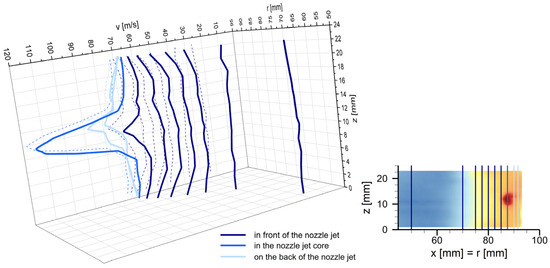

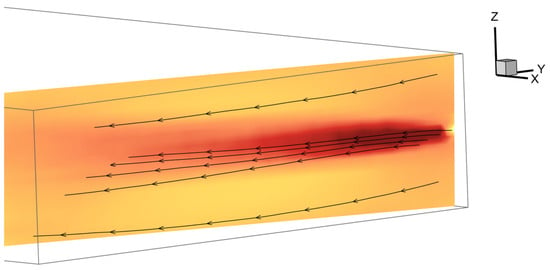

The velocity field of the unloaded grinding gas flow at nozzle level 12 mm above the bottom, shown in Figure 3, clearly reveals that the nozzle jet is deflected almost immediately by the basic spiral vortex flow as soon as it enters the grinding chamber. This phenomenon can be qualitatively described by Abramovich’s model of the encountered and deflected open jet [38]. According to Bauer [8], the deflection of the nozzle jet depends on the mass-related momentum of the nozzle jet in relation to that of the basic spiral vortex flow:

In the literature, various approaches exist for calculating the nozzle jet axis of an air jet that enters a lateral parallel flow at a certain angle from a circular nozzle with a diameter of dn. According to Abramovich [38], Shandorov (Equation (2)) and Ivanov (Equation (3)) determined the following empirical equations based on experiments in order to describe the deflection of a jet emerging from a nozzle at the point (x′, y′ = 0, 0):

Conversely, Abramovich [38] established a balance of forces between the aerodynamic drag force and the centrifugal force on a volume element of the nozzle jet leading to the following theoretical analytical equation, after assuming certain boundary conditions:

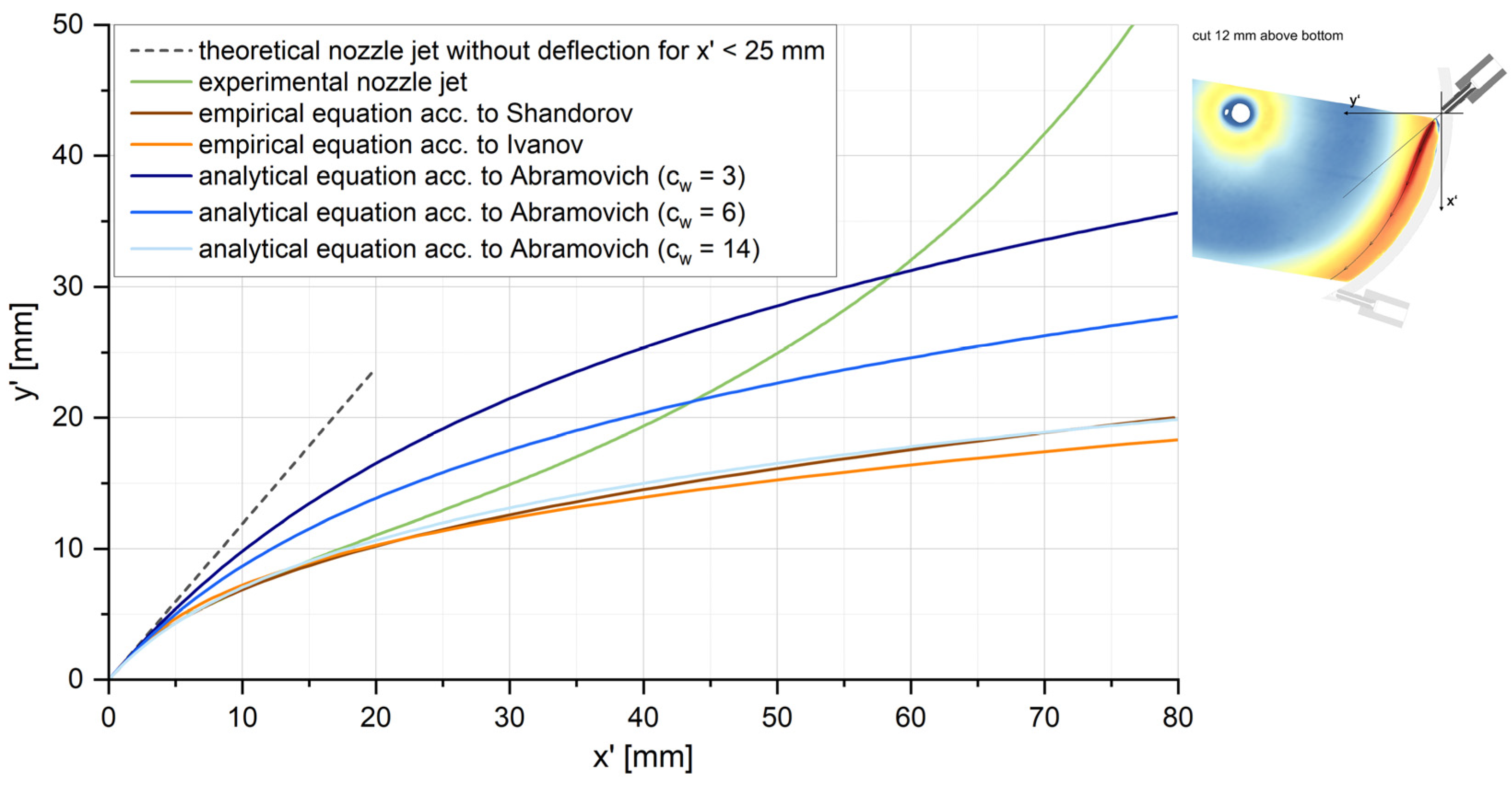

Figure 9 shows the results of these three approaches describing the deflection of the nozzle jet axis in comparison to the experimental data obtained by PIV measurements. The experimental curve corresponds to the streamline located in the core of the nozzle jet after the coordinate system has been shifted accordingly to the literature. Due to the limited optical accessibility of the grinding chamber at the nozzle outlet, the experimental data is only available for x′ > 6 mm.

Figure 9.

Course of the nozzle jet axis as a result of the deflection by the basic flow—comparison of the experimental data with empirical and analytical equations from the literature according to Equations (2)–(4) (adjusted coordinate system is outlined in the velocity field at nozzle level from Figure 3 at the top right).

Since the flow at the outlet of the nozzle is supercritical (the actual pressure ratio pm/pn′ is less than the critical pressure ratio pcrit,s/pn′), the velocity reaches a maximum equal to the sonic velocity that can be calculated as follows, assuming an ideal gas and an isentropic adiabatic change in state [41]:

With = 1.41 [41,42], Ri = 287.12 J/(kg K) [42], and a temperature at the nozzle inlet of Tin = 20 °C, the sonic velocity is vcrit = 313.8 m/s. If friction losses are taken into account according to a polytropic change in state described by Bohl and Elmendorf [41] the velocity at the outlet of the nozzle is reduced to vn = 301.8 m/s with a corresponding density of n = 3.99 kg/m3. The velocity of the basic flow of vf = 75 m/s, simplified and assumed to be constant, is extracted from the velocity field at the nozzle level immediately before reaching the nozzle jet, while the density of f = 1.37 kg/m3 is estimated based on the ideal gas law, considering a pressure in the grinding chamber of pm = 1.16 bar and a temperature of Tm = 20 °C. Taking these values into account, the nozzle jet axis can be calculated according to Equations (2)–(4), whereby a drag coefficient of cw = 3 is assumed for the analytical function based on the results of Abramovich [38]. In order to adjust the analytically determined data to the experimental and empirical data, the drag coefficient is increased up to cw = 14.

The comparison of the curves in Figure 9 indicates that the experimental nozzle jet axis can be described with a high degree of accuracy by the empirical equations of Shandorov and Ivanov for x′ < 20 mm. Conversely, the analytical function, according to Abramovich, only exhibits a similarity to these curves for a very large drag coefficient of cw = 14. This discrepancy arises because the derivation of the analytical equation based on force balance neglects the fact that the velocity and density of the nozzle jet decrease with increasing distance from the nozzle outlet. Consequently, the nozzle jet is deflected to a greater extent than predicted by the calculated values. In contrast to the initial deflection of the nozzle jet immediately after entering the grinding chamber, the course of the jet axis for x′ > 20 mm is no longer described by the equations from the literature, since the surrounding circular wall of the grinding chamber determines the further flow of the nozzle jet and its transition into the basic spiral vortex flow. The empirical and analytical equations, however, are based on a rectangular flow chamber and a parallel base flow, so that the calculated nozzle jet axis does not experience any further deflection.

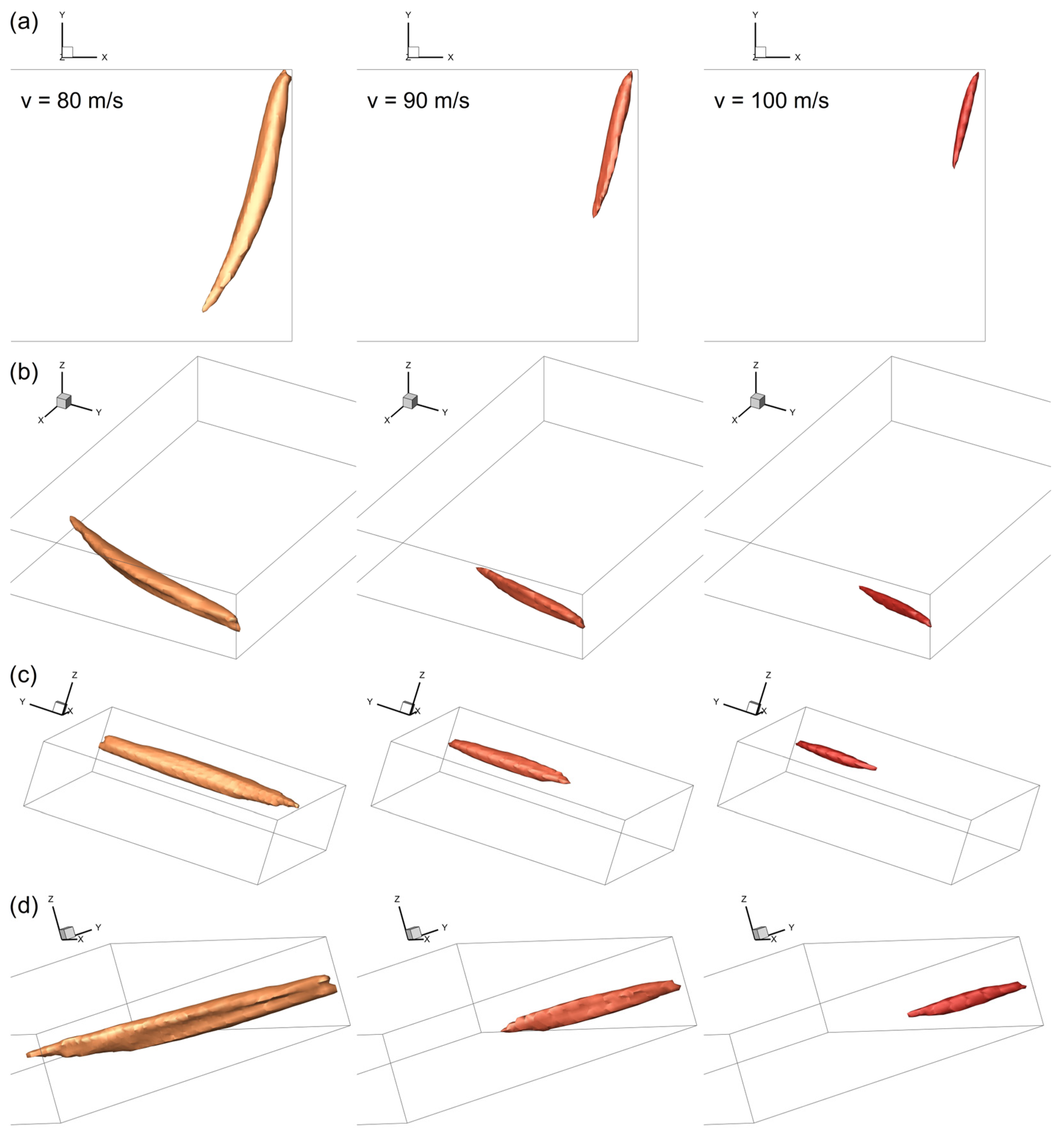

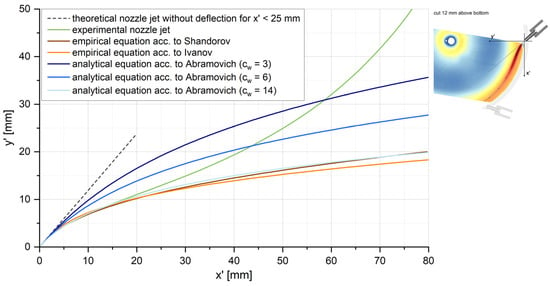

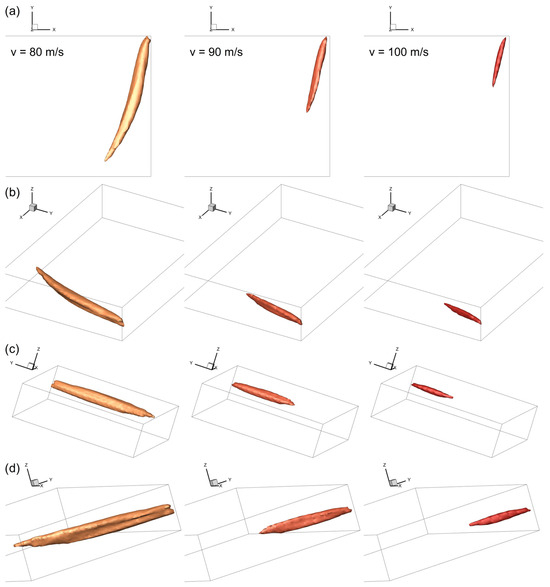

In order to provide a more precise description of the nozzle jet’s shape, a series of iso-surfaces for a velocity limit of v = 80, 90, and 100 m/s is generated from the experimental 3D model, as illustrated in Figure 10 from various perspectives. As the velocity limit increases, the size of the iso-surface decreases according to the established flow pattern, while the shape of the nozzle jet concurrently undergoes a significant change.

Figure 10.

Iso-surfaces for a flow velocity limit of v = 80, 90, and 100 m/s (from left to right) generated from the 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow based on experimental data in Figure 4—top (a) and oblique view (b) as well as view of the front (c) and back of the nozzle jet (d).

At a velocity limit of v = 100 m/s, the nozzle jet exhibits an almost circular flow cross-section in the direction of the jet, whose size initially increases after entering the grinding chamber due to the expansion before decreasing again due to frictional energy loss and the associated deceleration of the flow.

In contrast, at a velocity of v = 80 m/s, the flow of the nozzle jet deforms into a kidney shape, while the size of the flow cross-section shows a similar correlation as previously described for a velocity of v = 100 m/s. The observation of a kidney-shaped flow cross-section is in complete agreement with the description of the flow in the nozzle jet region of a spiral jet mill by Kürten and Rumpf [4], which is based on Abramovich’s model of the encountered and deflected open jet [38].

The round front of the nozzle jet visible in the iso-surface is caused by the deceleration of the encountered basic spiral vortex flow and the resulting formation of a stagnation zone (overpressure region). Subsequent to the redirection in the surroundings of the nozzle jet, the basic flow separates on the back of the nozzle jet, giving rise to a wake zone (region of negative pressure) with two counter-rotating vortices that are carried along by the nozzle jet. The kidney-shaped deformation of the jet, induced by the pressure forces on its front and back and the lateral shear forces, is particularly evident in the iso-surface due to the notch on the back of the nozzle jet, where the vortex-pair rotates. These findings thus provide the first experimental confirmation of the assumption of Kürten and Rumpf [4], based solely on theoretical considerations, that the flow in the nozzle jet region of a spiral jet mill can be described by Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38].

At a velocity limit of v = 90 m/s, the iso-surface continues to exhibit the kidney-shaped flow cross-section. However, this deformation of the cross-section is considerably less pronounced compared to its manifestation at the lower velocity of v = 80 m/s, whereas the shape of the nozzle jet in the flow direction already resembles the shape observed at a velocity of v = 100 m/s.

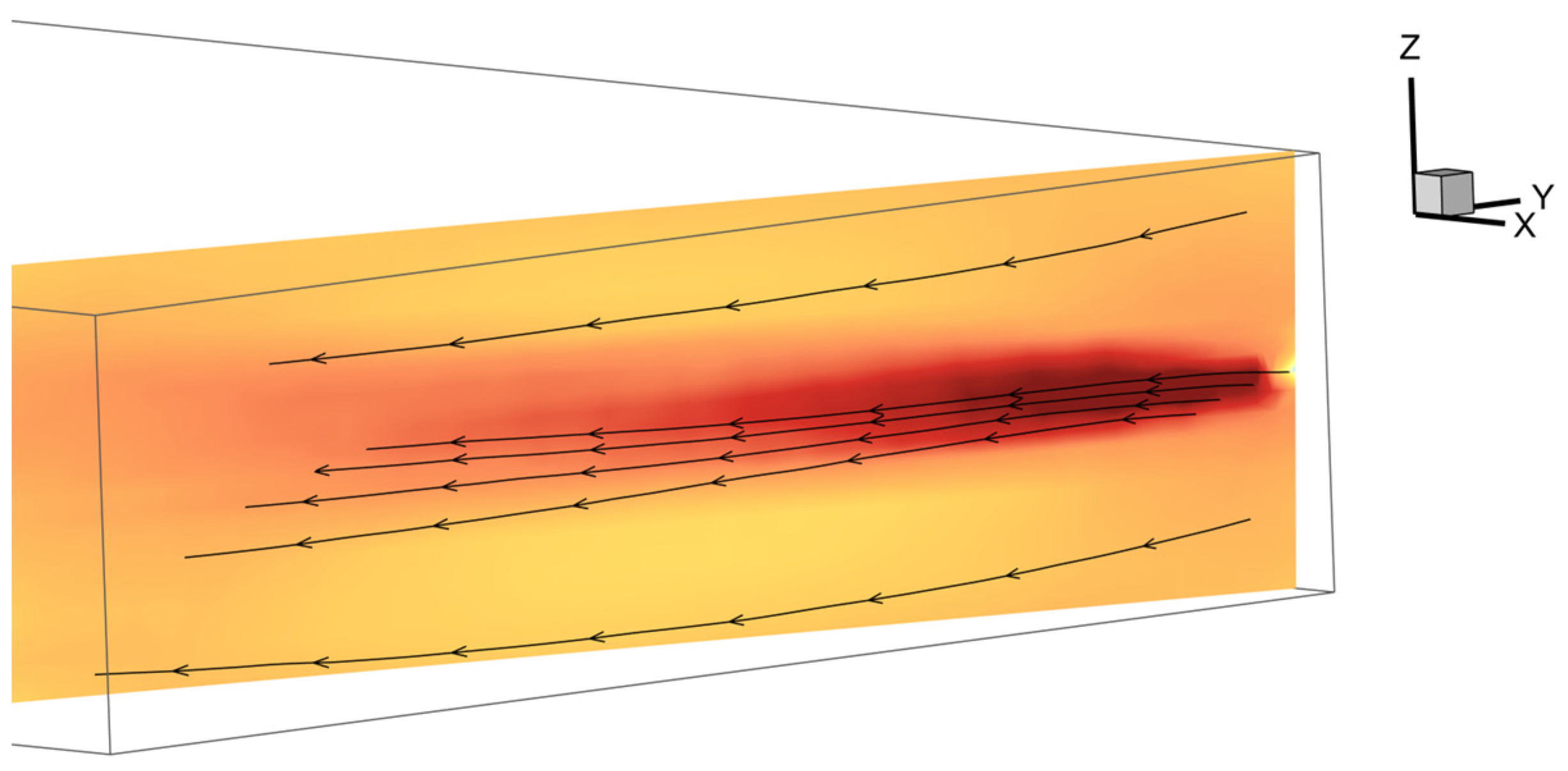

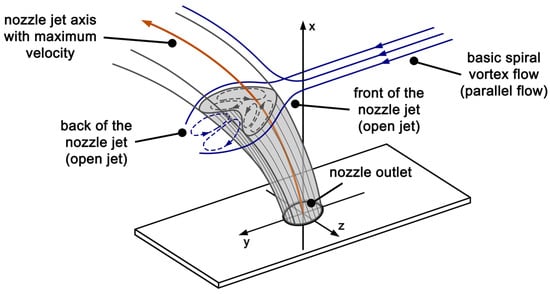

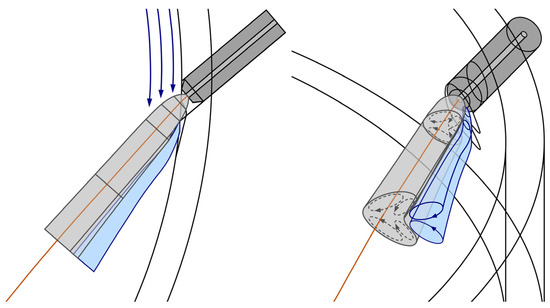

Based on Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38] and the experimental findings regarding the aerodynamics obtained in the course of this work, a model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet of the unloaded grinding gas flow in a spiral jet mill is created, as illustrated in Figure 11. After exiting the nozzle outlet and entering the grinding chamber, the nozzle jet initially expands with a circular flow cross-section. As soon as the jet is encountered and deflected by the basic spiral vortex flow, the vortex-pair forms on its back, resulting almost directly in a deformation of the nozzle jet that intensifies with increasing distance from the nozzle outlet. Due to the restriction of the optical accessibility of the grinding chamber by the nozzle borehole in the grinding ring, the circular flow cross-section cannot be captured experimentally (cf. Figure 10), as it rapidly transitions into the kidney-shaped cross-section.

Figure 11.

Model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet of the unloaded grinding gas flow in a spiral jet mill, based on Abramovich’s nozzle jet model, from different perspectives.

In contrast to Abramovich’s nozzle jet model, this one accounts for the fact that the nozzle jets enter the spiral vortex flow at an oblique angle, rather than perpendicularly. Moreover, the basic flow in this model is characterized by a tangential flow with an increasing velocity in the direction of the peripheral grinding ring, as opposed to the parallel flow with constant velocity as presumed in Abramovich’s model. Additionally, the fixed wall boundaries of the grinding chamber are taken into account, thereby ensuring that the vortex pair on the back of the nozzle jet cannot expand unimpeded.

3.5. Influence of Particle Loading on the Grinding Gas Flow in the Nozzle Jet Region

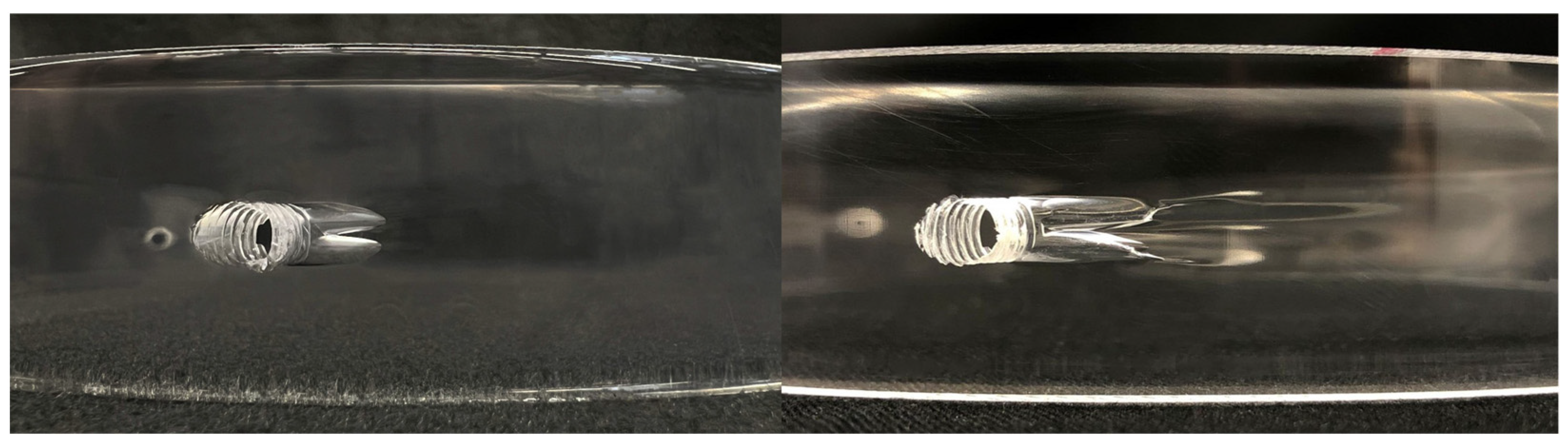

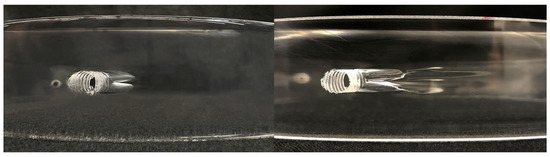

The existence of the vortex pair on the back of the nozzle jet can be confirmed not only through the experimental 3D model of the unloaded grinding gas flow, but also through the observed abrasion on the inner wall of the grinding chamber subsequent to conventional grinding experiments with particle loading, as depicted in Figure 12. Two symmetrical notches are formed behind the nozzle outlet in the direction of flow, whose intensity increases with increasing grinding duration. However, in the mid-range of the nozzle jet at the medium height of the mill, there is negligible abrasion, resulting in the formation of a material bridge that remains even after a long grinding duration. The two notches in the grinding ring each measure approximately 3 to 4 times the height of the nozzle diameter in the case under consideration. A very similar abrasion behavior has also been observed in industrial spiral jet mills made of metallic materials.

Figure 12.

Abrasion on the inner wall of the grinding chamber in the nozzle jet region after a short (left) and after a long grinding duration (right) in operation with particle loading.

The formation of the two notches through abrasion can be most adequately explained by the two-dimensional velocity field of the particle-loaded grinding gas flow obtained by PIV measurements at the nozzle level, as shown in Figure 13, and the corresponding model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Horizontal velocity field of the particle-loaded grinding gas flow obtained by PIV measurements with CaCO3 as tracer at the nozzle level (at a height of z = 12 mm above the bottom).

Figure 14.

Model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet of the particle-loaded grinding gas flow in a spiral jet mill, taking into account the vortex-pair on its back and the abrasion on the inner wall of the grinding chamber in the nozzle outlet region, from different perspectives.

The velocity field in Figure 13 reveals that, unlike the unloaded grinding gas flow, the nozzle jet of the loaded flow is barely affected by the basic spiral vortex flow, but protrudes far into the grinding chamber according to the nozzle angle, with only slight deflection occurring. This results from the strong acceleration of the solid grinding material particles by the nozzle gas flow due to their significantly higher inertia. However, the flow velocity in the outer region of the grinding chamber decreases due to the deceleration of the basic spiral vortex flow as a result of the forced redirected flow around the nozzle jet.

A qualitative comparison of the experimental data obtained in this study (cf. Figure 13) with the numerical results concerning the particle flow calculated by CFD-DEM simulation for a slightly different nozzle angle of 50°, presented in the work of Scott et al. [30] shows a good agreement of the data at the nozzle level, at least in the comminution zone and the region of the nozzle jets. However, in the classification zone, no numerical data is available for the average particle velocity. Similar to the grinding gas flow, a quantitative comparison of the particle flow results is not presented, as both the geometric and the operating parameters differ significantly from each other.

The model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet of the unloaded grinding gas flow depicted in Figure 11 can be completely transferred to the particle-loaded flow except for the adjusted nozzle jet axis due to the reduced deflection of the nozzle jet, as illustrated in Figure 14. The protruding nozzle jet causes an increase in the free space between the grinding chamber wall and the back of the nozzle jet, facilitating the formation of the vortex-pair in this region. Similar to the nozzle jet, the cross-section of the two vortices carried along by the nozzle jet increases with increasing distance from the nozzle outlet due to the expansion of the grinding gas. The two notches in the grinding ring, caused by material abrasion, occur precisely in the region where the vortex-pair is formed on the back of the nozzle jet. However, as the two vortices are carried along by the nozzle jet, the abrasion only occurs immediately behind the nozzle outlet.

4. Conclusions

As part of this work, an experimental three-dimensional model of the unloaded grinding gas flow within a spiral jet mill was successfully developed for the first time based on the two-dimensional velocity fields determined using the experimental planar PIV measurement method at various horizontal levels within the grinding chamber.

The experimental 3D model demonstrates the typical spiral vortex flow, which is superimposed by the nozzle jets, as well as the two characteristic regions of accelerated flow velocity in the comminution and classification zone. Moreover, the three-dimensional analysis of the nozzle jet enabled the first experimental validation of the theoretical assumption proposed by Kürten and Rumpf [4], that the flow dynamics in the nozzle jet region of a spiral jet mill can be described by Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38]. After exiting the nozzle outlet, the nozzle jet expands with a circular cross-section. As soon as the jet is encountered and deflected by the basic flow, a vortex pair is formed on the back of the nozzle jet, resulting almost directly in a deformation of the nozzle jet into a kidney-shaped flow cross-section.

Based on Abramovich’s nozzle jet model [38] and the experimental findings regarding the aerodynamics obtained in the course of this work, a model of the deflected and deformed nozzle jet of a spiral jet mill could be created that is relevant for both the unloaded and the particle-loaded grinding gas flow. Due to the experimental 3D model, a profound understanding of the flow processes within a spiral jet mill, particularly in the region of the nozzle jets, was achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.R., M.U. and H.J.S.; methodology, L.M.R. and H.J.S.; software, L.M.R.; validation, L.M.R. and H.J.S.; formal analysis, L.M.R.; investigation, L.M.R.; resources, H.J.S.; data curation, L.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.R.; writing—review and editing, L.M.R., M.U. and H.J.S.; visualization, L.M.R.; supervision, M.U. and H.J.S.; project administration, M.U. and H.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial, administrative, and technical support of their efforts provided by the internal research program of the University of Applied Sciences Niederrhein, as well as the Institute for Coatings and Surface Chemistry (ILOC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and symbols are used in this manuscript:

| 2D, 3D | two- and three-dimensional | |

| CaCO3 | calcium carbonate | |

| CAD | computer-aided design | |

| CCD | charge-coupled device | |

| CFD | computational fluid dynamics | |

| DEHS | diethylhexyl sebacate | |

| DEM | discrete element method | |

| LES | large eddy simulation | |

| Nd:YAG | neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet | |

| PBM | population balance model | |

| PIV | particle image velocimetry | |

| PMMA | polymethyl methacrylate | |

| cw | [ ] | drag coefficient |

| dn | [mm] | nozzle outlet diameter (minimum diameter) |

| minj | [kg·h−1] | injector gas mass flow rate |

| mn | [kg·h−1] | grinding gas mass flow rate (nozzles) |

| mtotal | [kg·h−1] | total grinding gas mass flow rate |

| pcrit,s | [bar] | critical pressure for an isentropic change of state |

| pinj | [bar] | injector gas pressure (in case of particle-loaded flow) |

| pm | [bar] | gas pressure downstream of the seeder (in case of unloaded flow) |

| pn | [bar] | grinding gas pressure (nozzles) |

| pn′ | [bar] | grinding gas pressure (nozzles) considering a pressure drop of 50 mbar |

| ps | [bar] | gas pressure upstream of the seeder (in case of unloaded flow) |

| R | [ ] | mass-related momentum ratio of the nozzle jet and the basic flow |

| Ri | [J·kg−1·K−1] | specific gas constant of dry air |

| r | [mm] | radius |

| s | - | standard deviation |

| Tn | [°C] | temperature at the nozzle outlet |

| Tin | [°C] | temperature at the nozzle inlet |

| v | [m·s−1] | flow velocity |

| vcrit | [m·s−1] | sonic velocity |

| vf | [m·s−1] | flow velocity of the basic spiral vortex flow or parallel flow |

| vn | [m·s−1] | flow velocity at the nozzle outlet |

| x | [mm] | horizontal coordinate |

| x′ | [mm] | adjusted x-coordinate |

| y | [mm] | vertical coordinate |

| y′ | [mm] | adjusted y-coordinate |

| z | [mm] | height-dependent coordinate |

| Ø | - | arithmetic mean value |

| [°] | tangential nozzle angle | |

| f | [kg·m−3] | density of the basic spiral vortex flow or parallel flow |

| n | [kg·m−3] | density at the nozzle outlet |

| [ ] | isentropic exponent of dry air | |

References

- Muschelknautz, E.; Giersiepen, G.; Rink, N. Strömungsvorgänge bei der Zerkleinerung in Strahlmühlen. Chem. Ing. Tech. 1970, 42, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Polke, R.; Schädel, G. Spiral jet mills: Hold up and scale up. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1996, 44–45, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönert, K.; Bauckhage, K. Zerteilprozesse. In Handbuch der Mechanischen Verfahrenstechnik, 1st ed.; Schubert, H., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; pp. 299–431. ISBN 978-3-527-30577-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kürten, H.; Rumpf, H. Strömungsverlauf und Zerkleinerungsbedingungen in der Spiralstrahlmühle. Chem. Ing. Tech. 1966, 38, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodnianski, V.; Krakauer, N.; Darwesh, K.; Levy, A.; Kalman, H.; Peyron, I.; Ricard, F. Aerodynamic classification in a spiral jet mill. Powder Technol. 2013, 243, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieß, M. Mechanische Verfahrenstechnik: Partikeltechnologie 1, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-540-32551-2. [Google Scholar]

- Höffl, K. Zerkleinerungs-und Klassiermaschinen, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; ISBN 3-540-16232-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, V. Experimentelle und theoretische Betrachtungen der Strömungsverläufe in Bezug auf die Sichtwirkung und Zerkleinerungsvorgänge in Spiralstrahlmühlen, (Fortschritt-Berichte VDI); Reihe 3, Nr. 589; VDI: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1999; ISBN 3-18-358903-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rief, F. Untersuchungen zum Betriebszustand einer Spiralstrahlmühle. Ph.D. Thesis, Bayerische Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, K. Untersuchungen zum Zerkleinerungsverhalten Kristalliner Stoffe in einer Spiralstrahlmühle. Ph.D. Thesis, Bayerische Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hagendorf, A. Untersuchungen zum Strömungsverhalten in einer Spiralstrahlmühle mittels Druckmessungen. Ph.D. Thesis, Bayerische Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fulga, I.; Strajescu, E. Theoretic and experimental contribution concerning the measurement of the functional parameters of the fluidic mill with spiral jets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic Engineering and Manufacturing Systems, Brasov, Romania, 25–26 October 2007; Volume 8, pp. 474–479. [Google Scholar]

- Kushimoto, K.; Suzuki, K.; Ishihara, S.; Soda, R.; Ozaki, K.; Kano, J. Analysis of the particle collision behavior in spiral jet milling. Adv. Powder Technol. 2023, 34, 103993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczak, B.; Müller, R.; Ulbricht, M.; Schultz, H.J. Experimental analysis of the flow conditions in spiral jet mills via non-invasive optical methods. Powder Technol. 2018, 325, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczak, B. Flow Conditions Inside Spiral Jet Mills and Impact on Grinding Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luczak, B.; Müller, R.; Kessel, C.; Ulbricht, M.; Schultz, H.J. Visualization of flow conditions inside spiral jet mills with different nozzle numbers—Analysis of unloaded and loaded mills and correlation with grinding performance. Powder Technol. 2019, 342, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeke, L.M.; Lindner, A.; Jongebloed, N.; Ulbricht, M.; Schultz, H.J. Optimization of the Classifying Efficiency of Spiral Jet Mills by Investigating the Flow Conditions and the Grinding Performance. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2023, 95, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeke, L.M.; Jongebloed, N.; Ulbricht, M.; Schultz, H.J. Experimental Investigation of the Flow Conditions in Spiral Jet Mills via Particle Image Velocimetry—Influence of Product Outlet Diameter and Gas Flow Rate. Powders 2023, 2, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozawa, K.; Seto, T.; Otani, Y. Development of a spiral-flow jet mill with improved classification performance. Adv. Powder Technol. 2012, 23, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabia, C.; Frigerio, G.; Casalini, T.; Cornolti, L.; Martinoli, L.; Buffo, A.; Marchisio, D.L.; Barbato, M.C. A detailed CFD analysis of flow patterns and single-phase velocity variations in spiral jet mills affected by caking phenomena. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 174, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, D.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J. Large Eddy Simulation of Swirl Topology Evolution in Strong Oxidant Jet Milling Force Field. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2025, 18, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogbe, S.C. Predictive Milling of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Excipients. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bnà, S.; Ponzini, R.; Cestari, M.; Cavazzoni, C.; Cottini, C.; Benassi, A. Investigation of particle dynamics and classification mechanism in a spiral jet mill through computational fluid dynamics and discrete element methods. Powder Technol. 2020, 364, 746–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Borissova, A.; Burns, A.; Ghadiri, M. Influence of holdup on gas and particle flow patterns in a spiral jet mill. Powder Technol. 2021, 377, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Borissova, A.; Burns, A.; Ghadiri, M. Effect of grinding nozzles pressure on particle and fluid flow patterns in a spiral jet mill. Powder Technol. 2021, 394, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhonsale, S.; Scott, L.; Ghadiri, M.; van Impe, J. Numerical Simulation of Particle Dynamics in a Spiral Jet Mill via Coupled CFD-DEM. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bnà, S.; Bottau, F.; Niemann, M.; Goniva, C.; Cottini, C.; Benassi, A. 4-way coupling CFD-DEM simulation of particle breakage and classification in a spiral jet mill: A critical analysis. Powder Technol. 2024, 439, 119722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, K.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J. CFD-DEM simulation of AP particle transport and breakage in a feed pipe. Powder Technol. 2025, 460, 121077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.M. Analysis of Fluid and Particle Dynamics in a Spiral Jet Mill by Coupled CFD-DEM. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, L.; Borissova, A.; Di Renzo, A.; Ghadiri, M. Application of coarse-graining for large scale simulation of fluid and particle motion in spiral jet mill by CFD-DEM. Powder Technol. 2022, 411, 117962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabia, C.; Casalini, T.; Cornolti, L.; Spaggiari, M.; Frigerio, G.; Martinoli, L.; Martinoli, A.; Buffo, A.; Marchisio, D.L.; Barbato, M.C. A novel uncoupled quasi-3D Euler-Euler model to study the spiral jet mill micronization of pharmaceutical substances at process scale: Model development and validation. Powder Technol. 2022, 405, 117573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabia, C. Numerical Investigation of Particles Breakage and Growth in Gas-Solid Processes: Spiral Jet Milling and Polyolefin Polymerization in Fluidized Bed Reactors. Ph.D. Thesis, Scuola di Dottorato, Turin, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakate, M.M.; Joshi, J.B.; Khakhar, D.V. Analysis of grinding in a spiral jet mill. Part 1: Batch grinding. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 231, 116310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakate, M.M.; Joshi, J.B.; Khakhar, D.V. Analysis of grinding in a spiral jet mill. Part 2: Semi-batch grinding. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 253, 117544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakate, M.M.; Joshi, J.B.; Khakhar, D.V. Influence of nozzle angle and classifier height on the performance of a spiral air jet mill. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Luo, H.; Bai, L.; Fan, X.; Baeyens, J. Novel production of ultrafine particles to meet environmental and energy sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultereys, V.; Matsunami, K.; Descamps, L.; Mertens, R.; Collas, A.; Kumar, A. In-Depth Understanding of the Impact of Material Properties on the Performance of Jet Milling of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramovich, G.N. The Theory of Turbulent Jets, 1st ed.; MIT-Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Strajescu, E.; Fulga, I. The vizualization of the fluidic fluxes in the mills with jets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economic Engineering and Manufacturing Systems, Brasov, Romania, 25–26 October 2007; Volume 8, pp. 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kürten, H.; Rumpf, H. Zerkleinerungsuntersuchungen mit tribolumineszierenden Stoffen. Chem. Ing. Tech. 1966, 38, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, W.; Elmendorf, W. Technische Strömungslehre: Stoffeigenschaften von Flüssigkeiten und Gasen, Hydrostatik, Aerostatik, Inkompressible Strömungen, Kompressible Strömungen, Strömungsmesstechnik, 13th ed.; Vogel: Würzburg, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-8343-3029-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, P.; Kabelac, S.; Kind, M.; Martin, H.; Mewes, D.; Schaber, K. VDI-Wärmeatlas, 11th ed.; VDI-Gesellschaft Verfahrenstechnik und Chemieingenieurwesen, Ed.; Springer Vieweg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-19980-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).