Quantifying the Multidimensional Benefits of Sustainable Shale Gas Development: A Copula–Monte Carlo Integrated Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

- (1)

- PCA-based dimensionality reduction, copula dependency modeling, and Monte Carlo simulation are integrated into a unified framework capable of capturing high-dimensional correlations and uncertainties.

- (2)

- A comprehensive evaluation system of 25 indicators across four dimensions—economic, environmental, social, and technological—was established, with indicator weights determined objectively using entropy weighting.

- (3)

- The framework quantitatively estimates the improvement of PMC development models over traditional models (22.11%) and provides a corresponding confidence interval.

- (4)

- Sensitivity analysis shows that the marginal benefits of environmental compliance and social governance indicators far exceed their theoretical weights, offering a scientific basis for policy design.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Development of the Indicator System

3.2. Feature Scaling

3.3. Entropy Weighting Method

3.3.1. Entropy Rights Method Process

3.3.2. Interpretation and Thresholds for Weights

3.4. PCA–Copula Modeling

3.4.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- (1)

- Compute the correlation matrix of the standardized data.

- (2)

- Solve for eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

- (3)

- Select principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 (Kaiser’s criterion).

- (4)

- Compute the principal component scores.

3.4.2. Copula Function Modeling

3.5. Monte Carlo Simulation

3.6. Sensitivity Quantification Method

4. Data Sources and Preprocessing

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Data Preprocessing

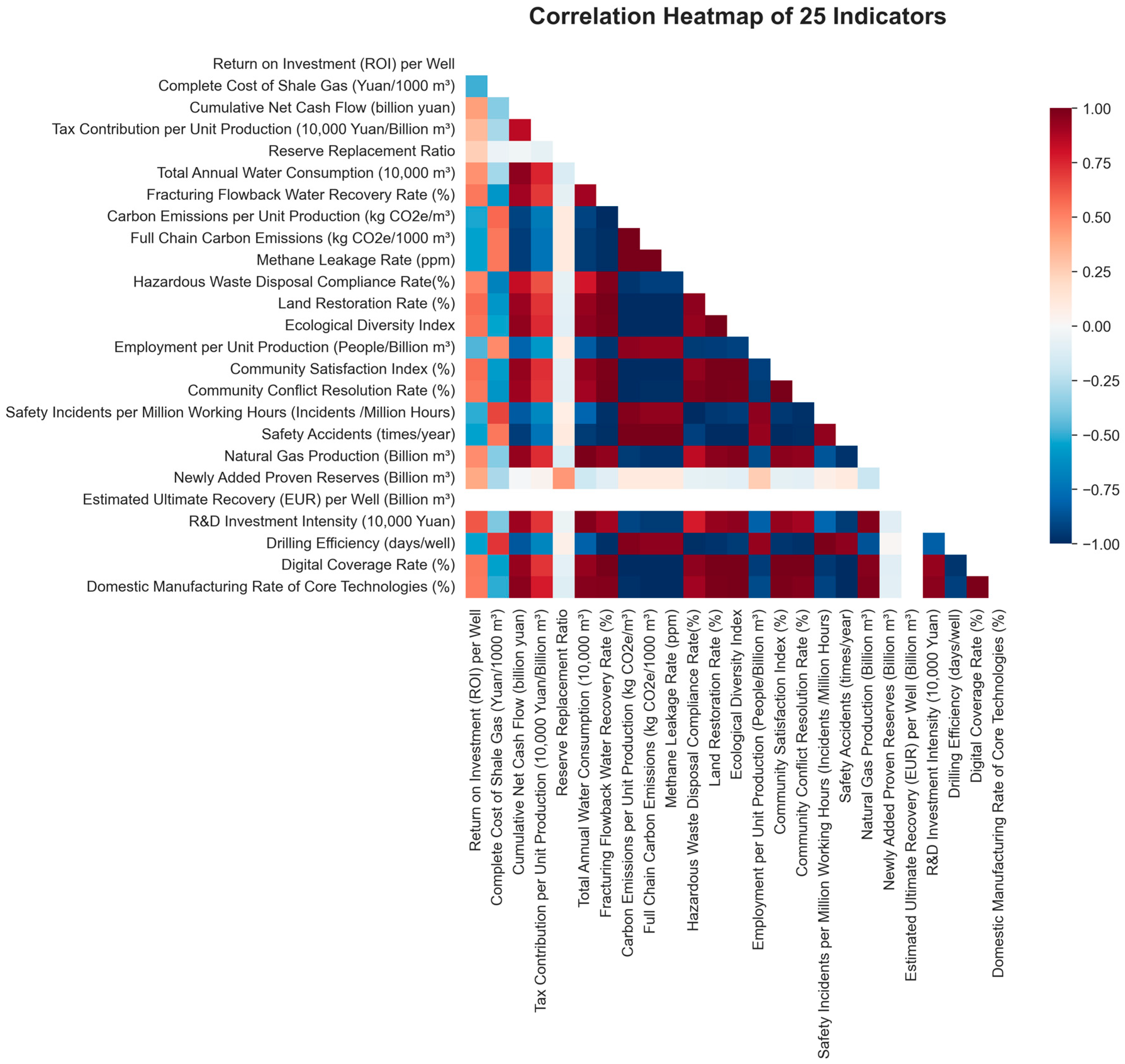

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.3.2. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Trend Analysis

4.4.1. Development Trajectory in the Economic Dimension

4.4.2. Environmental Conditions Continue to Improve

4.4.3. Reconstruction of Social Dimensions and Relationships

4.4.4. Technology-Driven Innovation

5. Results

5.1. Determination of Indicator Weights

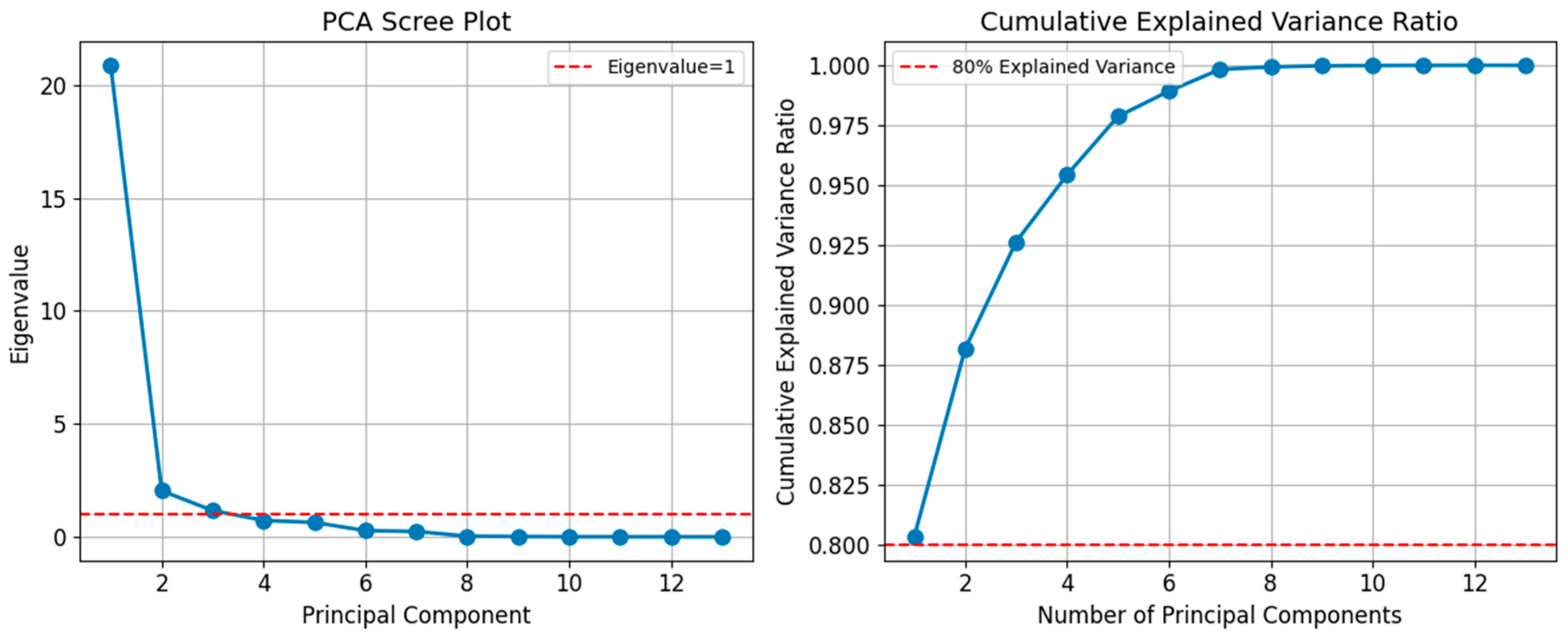

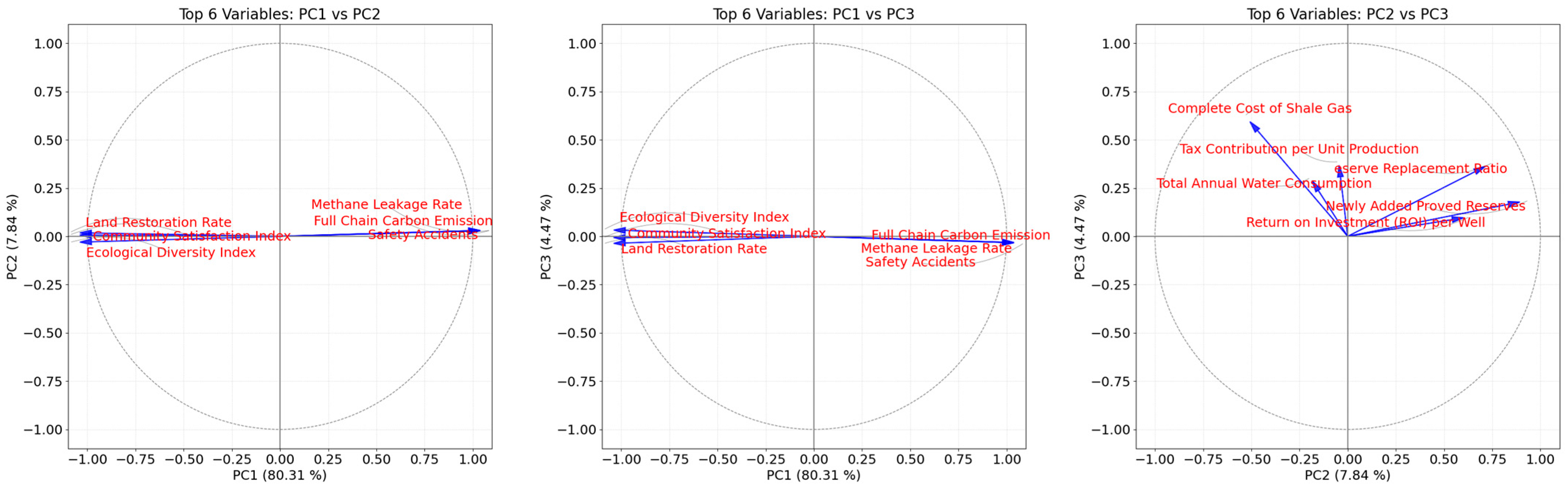

5.2. PCA Dimension Reduction Results

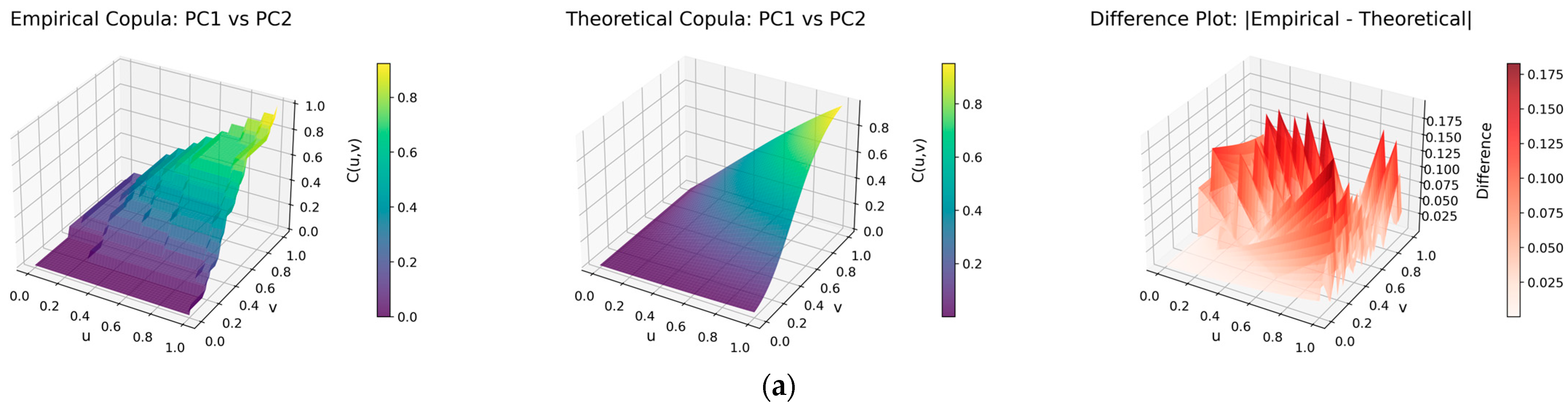

5.3. Copula Model Fitting

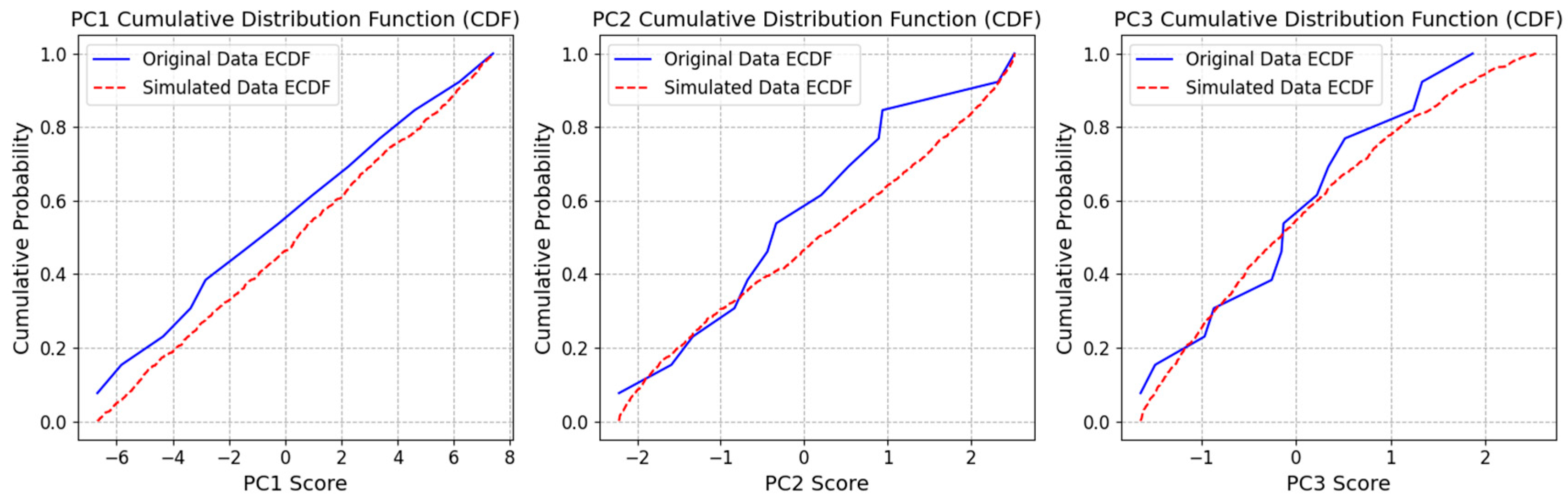

5.3.1. Edge-Distribution Selection

- (1)

- PC1: The KS test p-value is 1.000, well above the 0.05 significance threshold, and its AIC value is comparatively low, indicating that the uniform distribution provides an excellent fit for PC1.

- (2)

- PC2 and PC3: Both are best described by a four-parameter beta distribution (including the location parameter loc and scale parameters). Their KS test p-values, 0.560 and 0.654, respectively, are well above 0.05, meaning the null hypothesis cannot be rejected and the fitted beta distributions adequately represent the data.

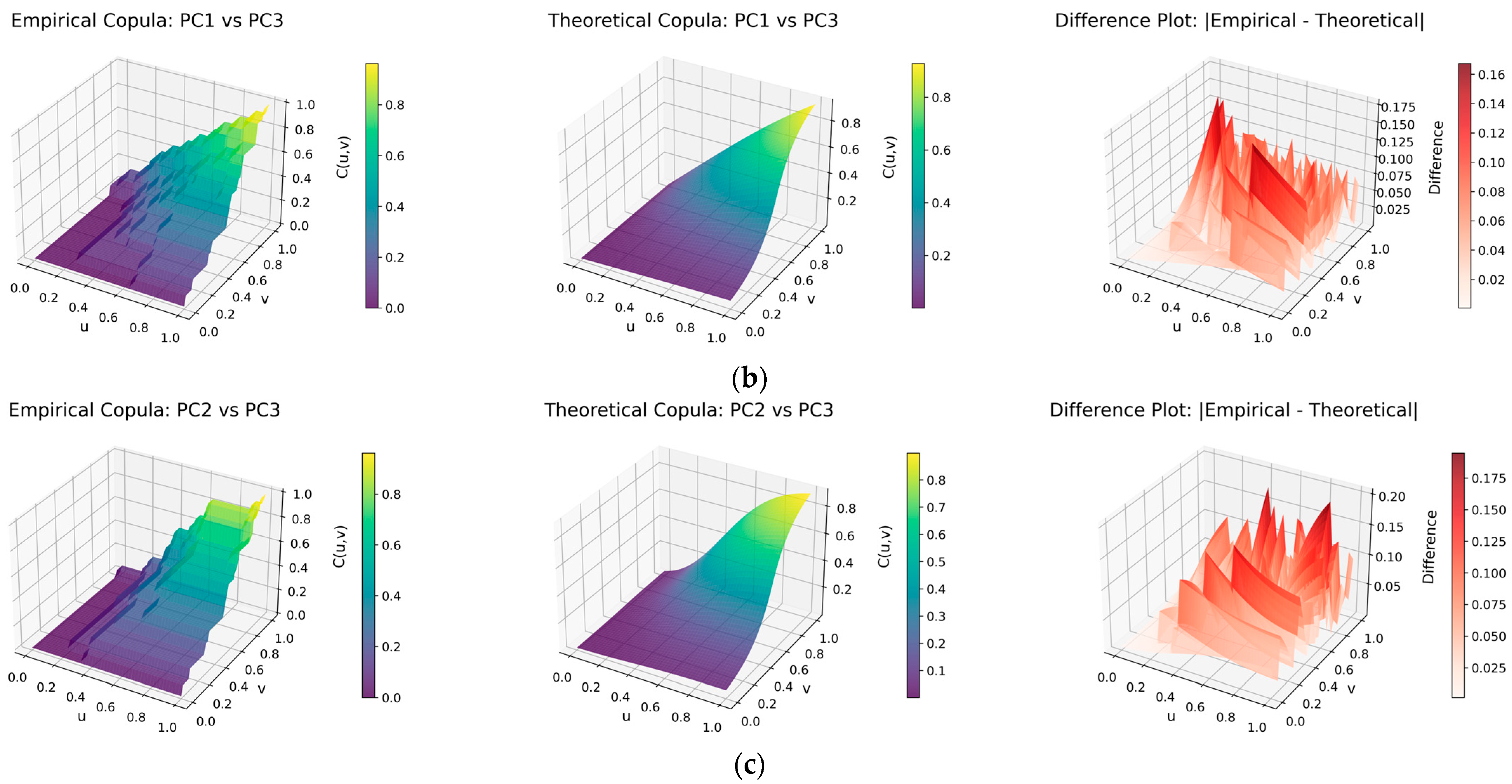

5.3.2. Gaussian Copula Goodness-of-Fit

5.3.3. Model Validation

5.4. Monte Carlo Simulation Results

5.4.1. Comparison of Traditional Models and Green Development Models

- (1)

- The PMC development model achieves an average benefit score of 0.567, an absolute increase of 0.102 over the traditional model’s 0.465, representing a 22% relative improvement. This difference is statistically significant, indicating that adopting the PMC development model yields substantial gains in overall performance.

- (2)

- The 90% confidence interval for the PMC model’s improvement over the traditional model is [2%, 46%]. The interval lies entirely above zero, and even its lower bound (2%) suggests a clear positive effect. This confirms the robustness of the simulation results and indicates that the PMC model’s advantage is not due to random variation.

- (3)

- The PMC model exhibits a smaller standard deviation in benefit scores (0.065 vs. 0.082) and a markedly higher minimum value (0.365 vs. 0.216). This shows that the PMC model not only improves average benefits but also significantly reduces volatility and downside risk, resulting in more stable and predictable performance.

5.4.2. Analysis of Benefit Distribution Characteristics

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

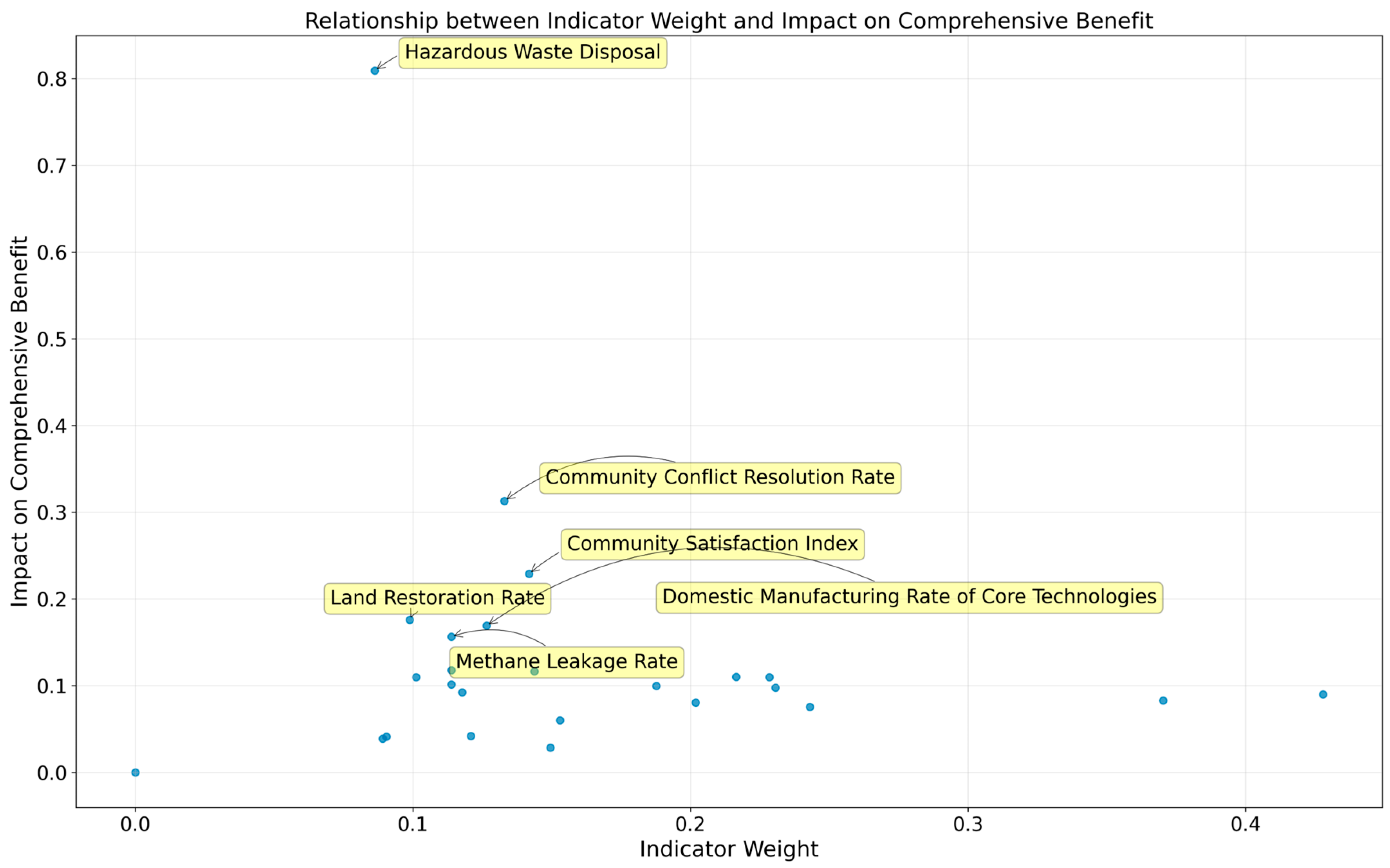

5.5.1. Key Metrics Influence Ranking

- (1)

- The impact coefficient of the hazardous waste compliance disposal rate (0.92) far exceeds its entropy weight method (0.11), demonstrating a clear “leveraging effect.” This indicates that even minor improvements in this indicator can generate disproportionately large gains in overall benefits. The reason is that environmental compliance serves as the “bottom line” and operational license for the project; non-compliance can trigger systemic risks such as work stoppages, hefty fines, or even project shutdowns, severely damaging profitability.

- (2)

- The actual impact coefficients for the Community Conflict Resolution Rate and Community Satisfaction Index (0.356 and 0.26) significantly exceed their theoretical weights. This shows that a “social license to operate” is not a soft requirement but a fundamental constraint that determines whether a projects can proceed smoothly and avoid delays and conflict-related costs.

- (3)

- Traditional financial indicator—such as return on investment (ROI) per well (impact coefficient 0.044) and cumulative net cash flow (0.032)—rank near the bottom. This aligns with the PMC development framework; these indicators function primarily as outcome variables that naturally improve when environmental, social, and technical dimensions perform well, rather than serving as dominant drivers themselves.

- (4)

- Within the technical dimension, the Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies (0.192) has a stronger influence than natural gas output (0.125). This suggests that under current conditions, technological self-reliance and supply-chain security contribute more to overall benefits than simply expanding production.

5.5.2. Analysis of Impact at the Dimensional Level

- (1)

- The environmental dimension shows the highest average impact coefficient (0.227), closely matching its maximum assigned weight (0.293). This confirms its central role in the comprehensive benefit assessment of shale gas development.

- (2)

- The average impact of the social dimension (0.161) exceeds what its weight (0.198) would suggest, indicating that its actual marginal contribution is underestimated. This highlights the need for greater managerial emphasis on social factors.

- (3)

- The economic dimension has a notably low average impact coefficient (0.043) that is below its weight (0.235). This suggests that, within a framework aimed at maximizing comprehensive benefits, overemphasis on short-term financial returns yields diminishing strategic value. Resources should instead be more heavily directed towards environmental and social domains.

5.5.3. Weight–Influence Relationship Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Benefit Mechanism of Green Development Models

6.1.1. Environmental–Economic Positive Feedback

6.1.2. Social–Operational Synergy

6.1.3. Technology-Sustainable Empowerment

6.1.4. Digitalization Drives Intelligent Leap in Systems

6.1.5. Key Drivers of the Green Transition

6.2. Research Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNPC | China National Petroleum Corporation |

| DPSIR | Driving Forces–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses, used to assess and manage environmental problems |

| PPFCI | Projection pursuit fuzzy clustering model |

| RAGA | Real coded accelerated genetic algorithm |

| WSR | Wuli–Shili–Renli |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PMC | PCA–Monte Carlo-based development model |

| ROI | Return on investment |

| LCA | Life-cycle assessment |

| DPSIRM | Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses–Management |

References

- Cooper, J.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Shale Gas: A Review of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability. Energy Technol. 2016, 4, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Duan, H.; Yan, Q. Shale gas: Will it become a new type of clean energy in China?—A perspective of development potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Dong, D.; Tao, K.; Guo, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Experiences and lessons learned from China’s shale gas development: 2005–2019. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 85, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, L. Deep shale gas in China: Geological characteristics and development strategies. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1903–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnaman, T.C. The economic impact of shale gas extraction: A review of existing studies. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasib, A.; Rickman, D.S. Regional economic impacts of the shale gas and tight oil boom: A synthetic control analysis. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2015, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Bentley, Y. Shale gas development and regional economic growth: Evidence from Fuling, China. Energy 2022, 239, 122254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T. Shale gas investment decision-making: Green and efficient development under market, technology and environment uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Du, J. Economic evaluation and environmental assessment of shale gas dehydration process. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Economic viability of UK shale gas and potential impacts on the energy market up to 2030. Appl. Energy 2018, 215, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecu, E.; Aceleanu, M.I.; Albulescu, C.T. The economic, social and environmental impact of shale gas exploitation in Romania: A cost-benefit analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, A.; Han, J.; Clark, C.E.; Wang, M.; Dunn, J.B.; Palou-Rivera, I. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Shale Gas, Natural Gas, Coal, and Petroleum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.W.; Santoro, R.; Ingraffea, A. Venting and leaking of methane from shale gas development: Response to Cathles et al. Clim. Change 2012, 113, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mao, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, W.; Xu, W. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of China shale gas. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, M.; McLellan, B.C.; Tang, X.; Feng, L. Environmental impacts of shale gas development in China: A hybrid life cycle analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 120, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Sun, W.; Höök, M. Environmental impacts from conventional and shale gas and oil development in China considering regional differences and well depth. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, T.V.; Mauter, M.S. Multiobjective Optimization Model for Minimizing Cost and Environmental Impact in Shale Gas Water and Wastewater Management. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3728–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, C.; Lettieri, P.; Chapman, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Shale Gas in the UK. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2706–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaraden, T.; Ayadi, O.; Alahmer, A. Towards sustainable shale oil recovery in Jordan: An evaluation of renewable energy sources for in-situ extraction. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 20, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Social sustainability assessment of shale gas in the UK. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Partridge, T.; Harthorn, B.H.; Pidgeon, N. Deliberating the perceived risks, benefits, and societal implications of shale gas and oil extraction by hydraulic fracturing in the US and UK. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, J.; McCawley, M.; Shonkoff, S.B. Public health implications of environmental noise associated with unconventional oil and gas development. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 580, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, A.K.; Vink, S.; Watt, K.; Jagals, P. Environmental health impacts of unconventional natural gas development: A review of the current strength of evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Hinojosa, M.S.; Hinojosa, R. Societal Implications of Unconventional Oil and Gas Development. In Advances in Chemical Pollution, Environmental Management and Protection; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, M.; Fan, J.; Bentley, Y.; Wang, X. Does shale gas exploitation contribute to regional sustainable development? Evidence from China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 40, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, G.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Deep shale gas exploration and development in the southern Sichuan Basin: New progress and challenges. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2023, 10, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Weng, D.; Guan, B.; Shi, J.; Cai, B.; He, C.; Sun, Q.; Huang, R. Shale oil and gas exploitation in China: Technical comparison with US and development suggestions. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Weng, D.; Xiong, S.; Liu, H.; Guan, B.; Deng, Q.; Yan, X.; Liang, H.; Ma, Z. Progress and development directions of shale oil reservoir stimulation technology of China National Petroleum Corporation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplin, M.; Bilan, T.; Makarov, V.; Novoseltsev, O.; Zaporozhets, A. Optimization of Technological Development of the Oil and Gas Industry. In Geomining: Systems and Decision-Oriented Perspective; Shukurov, A., Vovk, O., Zaporozhets, A., Zuievska, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perov, M.; Makarov, V.; Kaplin, M.; Novoseltsev, O.; Zaporozhets, A. Geological Features and Type of Oil Shale Booth. In Geomining: Systems and Decision-Oriented Perspective; Shukurov, A., Vovk, O., Zaporozhets, A., Zuievska, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xiong, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, X. Green financial regulation and shale gas resources management. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.-B.; Zhang, L.-H.; Zhao, Y.-L.; He, X.; Wu, J.-F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. Techno-economic and sensitivity analysis of shale gas development based on life cycle assessment. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 95, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Lu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Cao, X.; Liang, P.; Zhan, H. Techno-economic integration evaluation in shale gas development based on ensemble learning. Appl. Energy 2023, 357, 122486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S. Shale gas industry sustainability assessment based on WSR methodology and fuzzy matter-element extension model: The case study of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhan, L. Assessing the sustainability of the shale gas industry by combining DPSIRM model and RAGA-PP techniques: An empirical analysis of Sichuan and Chongqing, China. Energy 2019, 176, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, X. Evaluating the potential for sustainable development of China’s shale gas industry by combining multi-level DPSIR framework, PPFCI technique and RAGA algorithm. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, F.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, F.; Wang, D.; Li, H.; Yu, Z.; You, J. Sustainable development index of shale gas exploitation in China, the UK, and the US. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2022, 12, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fang, Y.; Mou, C. Integrated value of shale gas development: A comparative analysis in the United States and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, T. How to optimize the investment decision of shale gas multi-objective green development for energy sustainable development? J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepovitsyn, A.; Rutenko, E.; Solovyova, V. Sustainable Development of Oil and Gas Resources: A System of Environmental, Socio-Economic, and Innovation Indicators. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gu, A.; Jiang, F.; Xie, W.; Wu, Q. Integrated Assessment Modeling of China’s Shale Gas Resource: Energy System Optimization, Environmental Cobenefits, and Methane Risk. Energies 2020, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Shale Gas in the UK. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Patro, S.G.K.; Sahu, K.K. Normalization: A preprocessing stage. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 2, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Hall, C.A.S. Year in review—EROI or energy return on (energy) invested. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1185, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsel, A.; Wiesler, S.; Haas, J.; Bär, K.; Hinderer, M. Accounting for Local Geological Variability in Sequential Simulations—Concept and Application. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Unit | Impact Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Dimension | Return on Investment (ROI) per Well [43] | - | Positive |

| Complete Cost of Shale Gas | CNY/1000 m3 | Negative | |

| Cumulative Net Cash Flow | Billion Yuan | Positive | |

| Tax Contribution per Unit Production | CNY 10,000/Billion m3 | Positive | |

| Reserve Replacement Ratio | - | Positive | |

| Environmental Dimension | Total Annual Water Consumption | 10,000 m3 | Negative |

| Fracturing Flowback Water Recovery Rate | % | Positive | |

| Carbon Emissions per Unit Production | kg CO2e/m3 | Negative | |

| Full-Chain Carbon Emissions | kg CO2e/1000 m3 | Negative | |

| Methane Leakage Rate | ppm | Negative | |

| Hazardous Waste Disposal Compliance Rate | % | Positive | |

| Land Restoration Rate | % | Positive | |

| Ecological Diversity Index | - | Positive | |

| Social Dimension | Employment per Unit Production | People/Billion m3 | Positive |

| Community Satisfaction Index | % | Positive | |

| Community Conflict Resolution Rate | % | Positive | |

| Safety Incidents per Million Working Hours | Incidents/Million Hours | Negative | |

| Safety Accidents | Times/Year | Negative | |

| Technical Dimension | Natural Gas Production | Billion m3 | Positive |

| Newly Added Proven Reserves | Billion m3 | Positive | |

| Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) per Well | Billion m3 | Positive | |

| R&D Investment Intensity | (CNY 10,000) | Positive | |

| Drilling Efficiency | Days/Well | Negative | |

| Digital Coverage Rate | % | Positive | |

| Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies | % | Positive |

| Level | Dimension | Number of Indicators (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | All Dimensions | 4 | 0.25 |

| Secondary | Economy | 5 | 0.2 |

| Secondary | Environment | 8 | 0.125 |

| Secondary | Social | 5 | 0.25 |

| Secondary | Technique | 7 | 0.14 |

| Indicator | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return on Investment (ROI) per Well | 0.0668 | 0.017 | 0.4681 | 0.3926 | 0.2235 | 0.1103 | 0.1674 | 0.3351 | 0.372 | 0.3179 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.4 |

| Complete Cost of Shale Gas (CNY/1000 m3) | 6442.65 | 2440.09 | 1819.49 | 984.74 | 988.72 | 1211.25 | 932.92 | 1101.54 | 1212.7 | 1259.17 | 1300 | 1350 | 1400 |

| Cumulative Net Cash Flow (Billion Yuan) | −2.67 | −12.77 | −8.49 | 6.49 | 1.43 | 36.81 | 36.67 | 37.64 | 36.54 | 35.78 | 65.04 | 90.93 | 93.3 |

| Tax Contribution per Unit Production (CNY 10,000/Billion m3) | 0.0058 | 0.0053 | 0.0068 | 0.0043 | 0.008 | 0.0185 | 0.0173 | 0.0166 | 0.0251 | 0.0043 | 0.0121 | 0.0341 | 0.036 |

| Reserve Replacement Ratio | 3.839 | 3.497 | 4.45 | 7.535 | 1.18 | 4.607 | 3.904 | 3.321 | 5.63 | 1.955 | 6.195 | 3.896 | 2.567 |

| Total Annual Water Consumption (10,000 m3) | 142.06 | 131.52 | 126.08 | 137.26 | 154.84 | 190.06 | 210.25 | 226.33 | 268.65 | 318.19 | 354.18 | 420.28 | 450 |

| Fracturing Flowback Water Recovery Rate (%) | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 96 | 98 |

| Carbon Emissions per Unit Production (kg CO2e/m3) | 45.2 | 42.5 | 40 | 38 | 35 | 32 | 29.5 | 27 | 25 | 23.5 | 22 | 20.5 | 19 |

| Full-Chain Carbon Emissions (kg CO2e/1000 m3) | 120 | 115 | 110 | 105 | 100 | 95 | 90 | 85 | 80 | 75 | 70 | 65 | 60 |

| Methane Leakage Rate (ppm) | 150 | 145 | 140 | 135 | 130 | 125 | 120 | 115 | 110 | 105 | 100 | 95 | 90 |

| Hazardous Waste Disposal Compliance Rate (%) | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| Land Restoration Rate (%) | 65 | 68 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 82 | 85 | 88 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 96 |

| Ecological Diversity Index | 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Employment per Unit Production (People/Billion m3) | 159.5 | 174.6 | 163.6 | 142 | 120.1 | 110.2 | 100.4 | 82.2 | 48.7 | 41.4 | 58 | 63 | 65 |

| Community Satisfaction Index (%) | 70 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 88 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 96 |

| Community Conflict Resolution Rate (%) | 78 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 88 | 90 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 |

| Safety Incidents per Million Working Hours (Incidents/Million Hours) | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Safety Accidents (Times/Year) | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Natural Gas Production (Billion m3) | 142.06 | 151.82 | 137.26 | 154.84 | 190.06 | 210.25 | 226.33 | 268.65 | 318.19 | 354.18 | 383.35 | 420.28 | 450 |

| Newly Added Proven Reserves (Billion m3) | 545.38 | 599.63 | 2406.85 | 1731.02 | 875.72 | 2075.76 | 751.63 | 1512.54 | 621.98 | 194.27 | 1493.46 | 1078.92 | 1200 |

| Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) per Well (Billion m3) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| R&D Investment Intensity (CNY 10,000) | 233.46 | 246.06 | 300.47 | 348.29 | 317.88 | 282.59 | 349.16 | 394.29 | 471.09 | 522.3 | 580.5 | 649.38 | 713.41 |

| Drilling Efficiency (Days/Well) | 108 | 95 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 50 | 45 | 40 | 35 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 26 |

| Digital Coverage Rate (%) | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 92 | 95 |

| Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies (%) | 55 | 58 | 60 | 62 | 65 | 68 | 70 | 72 | 75 | 77 | 80 | 85 | 88 |

| Indicator | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return on Investment (ROI) per Well | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.47 |

| Complete Cost of Shale Gas (CNY/1000 m3) | 1726.41 | 1473.46 | 932.92 | 6442.65 |

| Cumulative Net Cash Flow (Billion Yuan) | 32.05 | 35.20 | −12.77 | 93.30 |

| Tax Contribution per Unit Production (CNY 10,000/Billion m3) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Reserve Replacement Ratio | 4.04 | 1.72 | 1.18 | 7.54 |

| Total Annual Water Consumption (10,000 m3) | 240.75 | 112.65 | 126.08 | 450.00 |

| Fracturing Flowback Water Recovery Rate (%) | 77.69 | 16.46 | 50.00 | 98.00 |

| Carbon Emissions per Unit Production (kg CO2e/m3) | 30.71 | 8.78 | 19.00 | 45.20 |

| Full-Chain Carbon Emissions (kg CO2e/1000 m3) | 90.00 | 19.47 | 60.00 | 120.00 |

| Methane Leakage Rate (ppm) | 120.00 | 19.47 | 90.00 | 150.00 |

| Hazardous Waste Disposal Compliance Rate(%) | 96.85 | 2.58 | 92.00 | 99.00 |

| Land Restoration Rate (%) | 81.92 | 10.01 | 65.00 | 96.00 |

| Ecological Diversity Index | 1.60 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 2.20 |

| Employment per Unit Production (People/Billion m3) | 102.21 | 46.64 | 41.40 | 174.60 |

| Community Satisfaction Index (%) | 83.62 | 8.36 | 70.00 | 96.00 |

| Community Conflict Resolution Rate (%) | 88.85 | 6.36 | 78.00 | 97.00 |

| Safety Incidents per Million Working Hours (Incidents/Million Hours) | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.80 |

| Safety Accidents (Times/Year) | 9.00 | 3.89 | 3.00 | 15.00 |

| Natural Gas Production (Billion m3) | 262.10 | 111.62 | 137.26 | 450.00 |

| Newly Added Proven Reserves (Billion m3) | 1160.55 | 653.48 | 194.27 | 2406.85 |

| Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) per Well (Billion m3) | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| R&D Investment Intensity (CNY 10,000) | 416.07 | 157.27 | 233.46 | 713.41 |

| Drilling Efficiency (Days/Well) | 53.77 | 26.99 | 26.00 | 108.00 |

| Digital Coverage Rate (%) | 69.38 | 18.55 | 40.00 | 95.00 |

| Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies (%) | 70.38 | 10.36 | 55.00 | 88.00 |

| Primary Indicator | Weight of Primary Indicators | of Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicator | Weight of Secondary Indicators | Weight Within Category | of Secondary Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Dimension | 0.225 | 0.25 | Return on Investment (ROI) per Well | 0.033 | 0.146 | 0.2 |

| Complete Cost of Shale Gas (CNY/1000 m3) | 0.014 | 0.063 | ||||

| Cumulative Net Cash Flow (Billion Yuan) | 0.055 | 0.245 | ||||

| Tax Contribution per Unit Production (CNY 10,000/Billion m3) | 0.090 | 0.398 | ||||

| Reserve Replacement Ratio | 0.033 | 0.148 | ||||

| Environmental Dimension | 0.293 | Total Annual Water Consumption (10,000 m3) | 0.032 | 0.109 | 0.125 | |

| Fracturing Flowback Water Recovery Rate (%) | 0.036 | 0.123 | ||||

| Carbon Emissions per Unit Production (kg CO2e/m3) | 0.037 | 0.126 | ||||

| Full-Chain Carbon Emissions (kg CO2e/1000 m3) | 0.041 | 0.139 | ||||

| Methane Leakage Rate (ppm) | 0.041 | 0.139 | ||||

| Hazardous Waste Disposal Compliance Rate (%) | 0.031 | 0.105 | ||||

| Land Restoration Rate (%) | 0.035 | 0.121 | ||||

| Ecological Diversity Index | 0.041 | 0.139 | ||||

| Social Dimension | 0.198 | Employment per Unit Production (People/Billion m3) | 0.054 | 0.271 | 0.25 | |

| Community Satisfaction Index (%) | 0.038 | 0.190 | ||||

| Community Conflict Resolution Rate (%) | 0.035 | 0.178 | ||||

| Safety Incidents per Million Working Hours (Incidents/Million Hours) | 0.031 | 0.157 | ||||

| Safety Accidents (Times/Year) | 0.041 | 0.205 | ||||

| Technical Dimension | 0.284 | Natural Gas Production (Billion m3) | 0.072 | 0.254 | 0.14 | |

| Newly Added Proven Reserves (Billion m3) | 0.040 | 0.142 | ||||

| Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) per Well (Billion m3) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| R&D Investment Intensity (CNY 10,000) | 0.063 | 0.220 | ||||

| Drilling Efficiency (Days/Well) | 0.027 | 0.097 | ||||

| Digital Coverage Rate (%) | 0.039 | 0.138 | ||||

| Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies (%) | 0.042 | 0.149 |

| Principal Component | Eigenvalue | Proportion of Variance Explained | Cumulative Proportion of Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 20.881 | 0.803 | 0.803 |

| PC2 | 2.039 | 0.078 | 0.882 |

| PC3 | 1.163 | 0.045 | 0.926 |

| Principal Component | Optimal Distribution | Distributed Parameters | KS Statistic | p-Value | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | Uniform | a = −6.677, b = 14.070 | 0.087 | 1.000 | 72.745 |

| PC2 | Beta | α = 0.704, β = 0.712, loc = −2.218, scale = 4.743 | 0.208 | 0.560 | 27.382 |

| PC3 | Beta | α = 0.846, β = 1.425, loc = −1.644, scale = 4.192 | 0.192 | 0.654 | 32.537 |

| Analysis Object | MSE | RMSE | JS Divergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1–PC2 pair | 0.0047 | 0.0683 | 0.0178 |

| PC1–PC3 pair | 0.0034 | 0.0582 | 0.0199 |

| PC2–PC3 pair | 0.0044 | 0.0661 | 0.0187 |

| Global Fitting | 0.0041 | 0.0643 | - |

| Mode | Average Score | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | 90% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Model | 0.465 | 0.082 | 0.216 | 0.723 | [0.329, 0.600] |

| Green Development Model | 0.567 | 0.065 | 0.365 | 0.785 | [0.457, 0.678] |

| Increase | +22% | - | - | - | [2%, 46%] |

| Indicator Dimension | Indicator Name | Impact on Comprehensive Benefit (%) | Impact Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Dimension | Hazardous Waste Disposal Compliance Rate (%) | 0.105 | 0.920 |

| Social Dimension | Community Conflict Resolution Rate (%) | 0.178 | 0.356 |

| Social Dimension | Community Satisfaction Index (%) | 0.190 | 0.260 |

| Environmental Dimension | Land Restoration Rate (%) | 0.120 | 0.199 |

| Technical Dimension | Domestic Manufacturing Rate of Core Technologies (%) | 0.149 | 0.192 |

| Environmental Dimension | Methane Leakage Rate (ppm) | 0.139 | 0.179 |

| Environmental Dimension | Full-Chain Carbon Emissions (kg CO2e/1000 m3) | 0.139 | 0.135 |

| Technical Dimension | Natural Gas Production (Billion m3) | 0.254 | 0.125 |

| Environmental Dimension | Fracturing Flowback Water Recovery Rate (%) | 0.123 | 0.124 |

| Environmental Dimension | Ecological Diversity Index | 0.139 | 0.115 |

| Technical Dimension | R&D Investment Intensity (CNY 10,000) | 0.220 | 0.113 |

| Technical Dimension | Digital Coverage Rate (%) | 0.138 | 0.105 |

| Environmental Dimension | Carbon Emissions per Unit Production (kg CO2e/m3) | 0.126 | 0.096 |

| Social Dimension | Employment per Unit Production (People/Billion m3) | 0.270 | 0.092 |

| Economic Dimension | Tax Contribution per Unit Production (CNY 10,000/Billion m3) | 0.398 | 0.085 |

| Social Dimension | Safety Accidents (Times/Year) | 0.205 | 0.069 |

| Environmental Dimension | Total Annual Water Consumption (10,000 m3) | 0.109 | 0.048 |

| Technical Dimension | Newly Added Proven Reserves (Billion m3) | 0.142 | 0.047 |

| Economic Dimension | Reserve Replacement Ratio | 0.148 | 0.046 |

| Economic Dimension | Return on Investment (ROI) per Well | 0.146 | 0.044 |

| Technical Dimension | Drilling Efficiency (Days/Well) | 0.097 | 0.040 |

| Economic Dimension | Cumulative Net Cash Flow (Billion Yuan) | 0.245 | 0.032 |

| Social Dimension | Safety Incidents per Million Working Hours (Incidents/Million Hours) | 0.157 | 0.030 |

| Economic Dimension | Complete Cost of Shale Gas (CNY/1000 m3) | 0.063 | 0.009 |

| Technical Dimension | Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) per Well (Billion m3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dimension | Average Impact (%) | Key Indicator | Maximum Impact (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Dimension | 0.227 | Compliance Rate for Hazardous Waste Disposal (%) | 0.920 |

| Social Dimension | 0.161 | Community Conflict Resolution Rate (%) | 0.356 |

| Technical Dimension | 0.089 | Domestic Production Rate of Core Technology (%) | 0.192 |

| Economic Dimension | 0.043 | Tax Contribution per Unit Production (CNY 10,000/Billion m3) | 0.085 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, T.; Wei, F.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y. Quantifying the Multidimensional Benefits of Sustainable Shale Gas Development: A Copula–Monte Carlo Integrated Framework. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13013. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413013

Yang T, Wei F, Guo Y, Liang Y. Quantifying the Multidimensional Benefits of Sustainable Shale Gas Development: A Copula–Monte Carlo Integrated Framework. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13013. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413013

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Tianxiang, Fan Wei, Ying Guo, and Yuan Liang. 2025. "Quantifying the Multidimensional Benefits of Sustainable Shale Gas Development: A Copula–Monte Carlo Integrated Framework" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13013. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413013

APA StyleYang, T., Wei, F., Guo, Y., & Liang, Y. (2025). Quantifying the Multidimensional Benefits of Sustainable Shale Gas Development: A Copula–Monte Carlo Integrated Framework. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13013. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413013