1. Introduction

The 15-a-side version of rugby is a discipline in which players are divided into forwards and backs. The forward formation consists of eight players, while the back formation includes seven. Each of these formations has distinct and specific tasks; however, on the field, they operate as an integrated whole. Players in the 15-a-side version are characterized by highly diverse somatic builds. Forwards may weigh approximately 85 up to even 140 kg, with the total mass of the entire pack reaching about 900 kg. Backs usually weigh less, which is due to the fact that their primary tasks require greater running speed and agility [

1].

As mentioned above, in 15-a-side rugby, two formations can be distinguished:

Forwards (the pack): consisting of eight players divided into the first, second, and third rows (three, two, and three players, respectively).

Backs: including the scrum half, fly half, two centers, two wings, and the fullback [

2].

The group of forwards is responsible for performing the physical groundwork that serves as the platform for the attacking play of the backs. A well-organized pack can push opponents into a defensive position, providing both psychological and territorial advantages.

The first row of the scrum (players no. 1, 2, and 3) is primarily responsible for its stability, for lifting players of the second and third rows during lineouts, and for regaining and maintaining possession during rucks.

The second row (players no. 4 and 5) plays a key role in contesting lineouts, providing opportunities for offensive play following set pieces.

The back row (players no. 6, 7, and 8) serves as the driving force of the team. The number 8 often initiates offensive actions by picking up the ball from the base of the scrum or another set phase [

3].

Back-row players act as a bridge between the forwards and the backs. They are required to possess high endurance, speed, and the ability to make immediate tactical decisions. They are present in nearly all rucks and actively participate in both defensive and offensive phases of play.

The backline formation in rugby plays the main role in organizing the team’s offensive play. These players perform various tasks: initiating attacks (scrum half and fly half), breaking through defensive lines (centers), and exploiting speed on the flanks (wings).

The backline is also characterized by tactical flexibility—players must react rapidly to changing in-game situations and decide whether to run, pass, or kick the ball forward. The backline focuses on quick and technical ball movement, utilizing strength, speed, and agility to break through defensive lines. Centers and wings work closely together to stretch the defense and create gaps for penetration. The fullback provides defensive security and relies on reaction speed and effective game reading.

The backline, also referred to as the “backs,” introduces tension and unpredictability into offensive play through rapid position exchanges and complex passing combinations. Coordination, communication, and adaptability to the opponent’s tactics are key. An effective backline allows the team to exploit individual strengths and adapt instantly to game situations. The backline forms the heart of offensive play in rugby, responsible for creating and executing strategies to score points through organized, fast, and creative teamwork.

In summary, excluding the half-backs (numbers 9 and 10), the backline consists mainly of centers who build attacking power through strength and technique, wings who utilize their speed to finalize plays, and the fullback, who safeguards the backfield and provides tactical support.

Just as the back-row players belong to the forward formation but perform different roles from the rest of the forwards, the scrum half (position no. 9) and the fly half (position no. 10) are part of the backline, yet their roles differ significantly from those of the other backs.

The structure of rugby play is such that the half-backs determine the organization and tactical direction of the entire team. They handle the ball much more frequently than other players and can be described as the “heart of the team” [

4].

Both positions require a high level of physical fitness; however, the scrum half more often moves laterally, performing feints and short sprints over limited distances, whereas the fly half must demonstrate excellent spatial awareness and peripheral vision. Their running trajectory is generally oriented forward, in contrast to the predominantly lateral movements of the scrum half [

5].

Regarding the distances covered during a match, fly halves run the most—on average around 6620 m per game—due to their constant involvement in both offensive and defensive actions and their frequent contact with the ball. The scrum half, on the other hand, covers an average distance of approximately 5850 m per match [

6].

In summary, the scrum half initiates play and distributes the ball during the initial phase of an action, while the fly half serves as the main offensive strategist, responsible for directing the attacking formation and exploiting gaps in the opponent’s defensive structure. Both positions require advanced technical skills, speed, and strong tactical and spatial awareness.

In 15-a-side rugby, a single play (also referred to as a “phase of play”) typically lasts from a few to several seconds, depending on the nature of the action and the situation on the field. Research indicates that, on average, during an 80 min rugby match, there are approximately 180 phases of play (also called rucks or regrouping actions). This means that a single phase—from the moment the ball is received until the next regrouping—lasts on average about 26–27 s.

Short actions: 3–8 s (few passes, quick contact with the opponent);

Medium actions: 10–20 s (series of passes, open play, several phases);

Long actions: over 30 s (usually within the opponent’s defensive zone, involving the entire team on offense) [

7].

In 15-a-side rugby, reaction time and decision-making accuracy are key elements determining the effectiveness of play. Reaction time is defined as the interval between the appearance of a stimulus (such as the movement of an opponent or the ball) and the first muscular response. It is essential for reacting swiftly to both offensive and defensive situations. Abilities such as reactive strength, speed, agility, and decision accuracy are interdependent and have a significant impact on player performance.

Quick and correct decision-making also requires strong focus and attention to dynamically changing stimuli on the field, enabling players to anticipate the movements of both opponents and teammates [

8].

Rugby is a game in which most points are scored through tries, making it essential for a team to maintain ball possession for as long as possible. Players must demonstrate speed, power, acceleration, agility, contact-handling skills, and the ability to make appropriate decisions in a short time. SAQ training (Speed, Agility, Quickness)—focused on improving reaction time and decision-making speed—is one of the main components of a rugby player’s training process.

Training designed to enhance reaction time and decision-making speed in rugby includes exercises such as rapidly getting up and catching a ball, receiving and passing the ball with eyes closed, or responding to unexpected visual or auditory stimuli. These exercises develop perception and reflexes. It is also important to train the ability to anticipate and rapidly analyze on-field situations. An adequate level of these abilities often determines the difference between victory and defeat in a rugby match [

9].

Reaction time is defined as the interval between the perception of a stimulus and the initiation of muscle movement. In rugby, it is a critical factor, as a rapid response to an opponent’s movement or to the ball can determine the success of an attack or defense. These reactions may be either simple or choice-based and involve both upper- and lower-limb movements. Reactive strength—the ability to quickly transition from the stretch phase to the muscle contraction phase—is closely related to reaction time and overall player effectiveness [

10].

In 15-a-side rugby, decisions must be made within fractions of a second in a dynamic and constantly changing environment. The ability to perform visual analysis and quickly recognize movement patterns on the field is highly important. Players must constantly scan the situation, memorize the positions of teammates and opponents, and anticipate subsequent actions in order to choose the optimal tactic—whether to pass, run, or defend.

Factors Influencing Reaction Time and Decision-Making

Visual and verbal stimuli: Players learn to recognize cues that help them anticipate upcoming plays.

Motivation and concentration: High levels of motivation and focus reduce reaction time.

Technical proficiency: Regular practice improves the automatization of responses.

Stress and uncertainty reduction: Lower psychological tension facilitates faster decision-making.

In summary, in 15-a-side rugby, the integration of sensorimotor reaction speed and the ability to make quick and accurate decisions are essential. These abilities stem from effective training, concentration, and on-field experience [

11].

The present study offers an original contribution to the growing body of research on perceptual–cognitive skills in rugby by providing a detailed analysis of reaction time differences across player formations and demonstrating their impact on game effectiveness. While previous studies have examined general cognitive demands in team sports, research specifically focusing on reaction time in rugby positions remains limited. By directly comparing players from different formations, this study identifies position-specific response patterns that may influence tactical decision-making, defensive organization, and offensive efficiency. The findings not only expand current scientific understanding but also offer practical implications for coaches, who can use these insights to design more targeted training programs aimed at enhancing players’ reaction capabilities and, consequently, improving overall team performance.

The aim of the present study is to analyze reaction time among rugby players with regard to their playing positions. The study seeks to determine whether reaction time differentiates players in various positions and to what extent it influences the effectiveness of decision-making and the execution of technical and tactical actions during the game.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Group

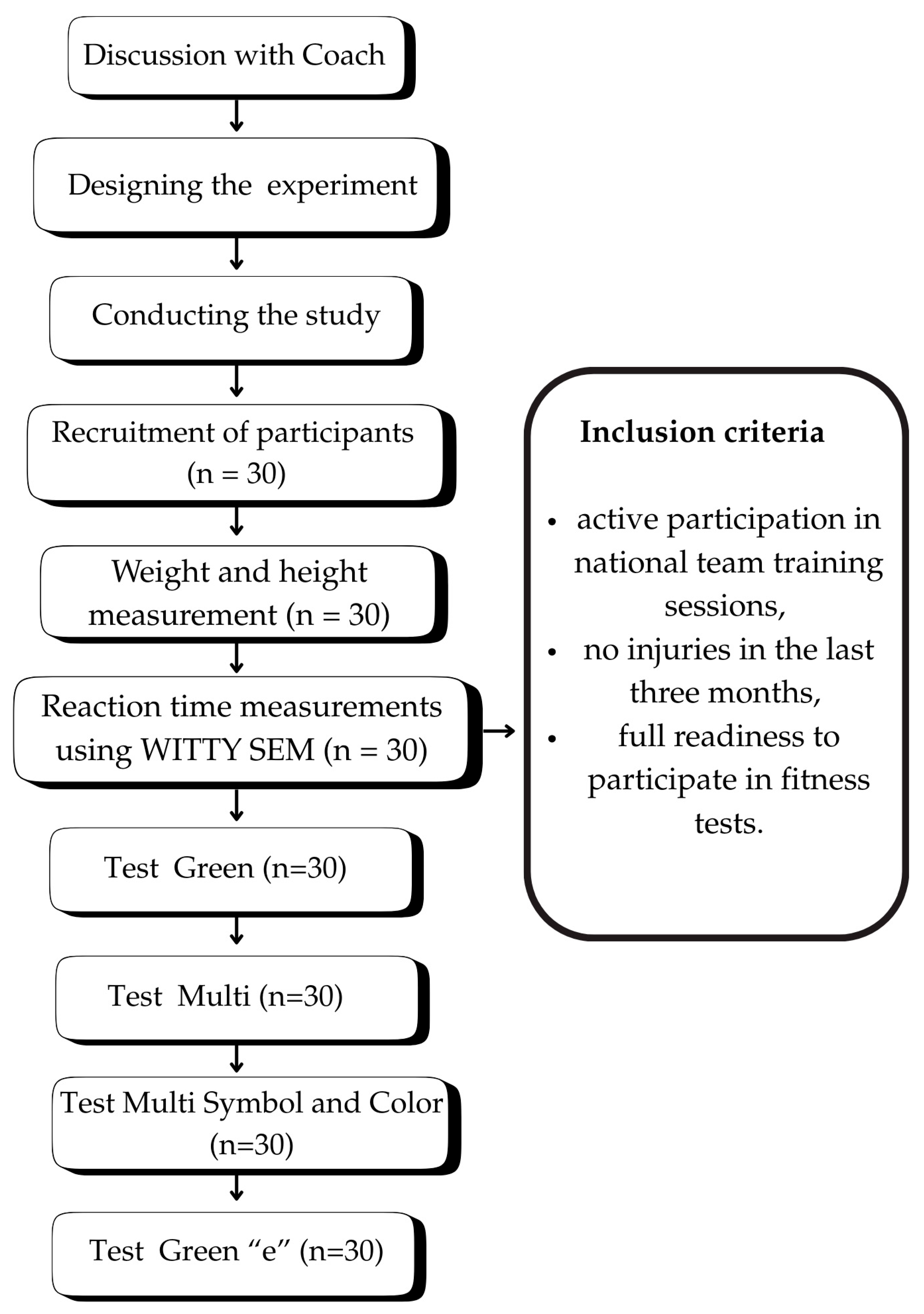

The study involved 30 players, all members of the Polish national under-20 rugby team for the 15-a-side version of the game. The testing took place during a training camp held four weeks before the U20 European Championships in Prague. The participants were players representing Polish clubs from the Ekstraliga (first and second-tier rugby leagues). The inclusion criteria included active participation in national team training sessions, no injuries in the last three months, and full readiness to participate in fitness tests. Among the participants, three players trained and played in England and one in Scotland.

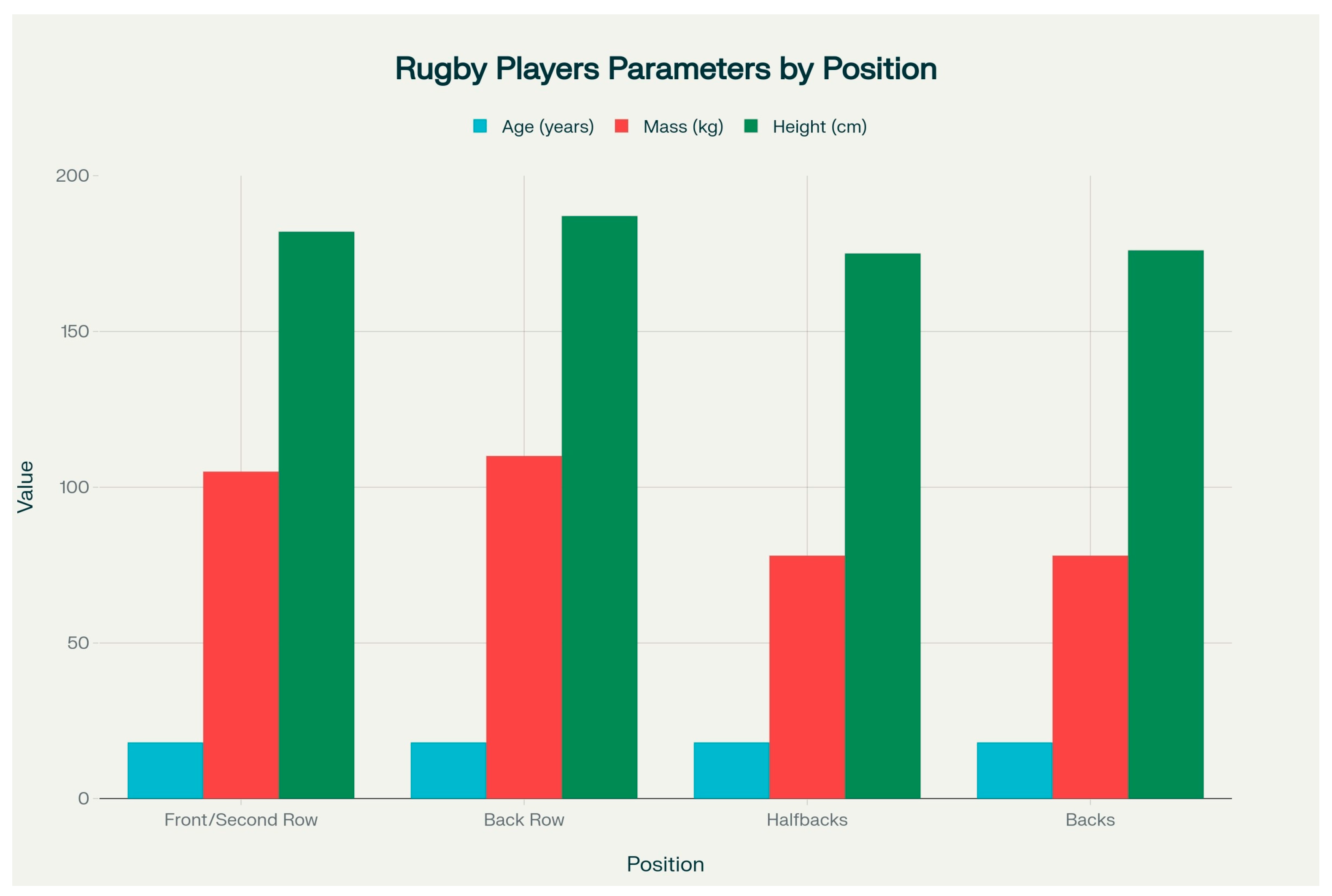

The average age of the entire group was 18.9 ± 0.99 years, with an average body mass of 95.03 ± 23.45 kg and an average height of 182.7 ± 8.09 cm.

For the purposes of the study, the players were divided into four groups based on their position on the field:

Front Row (9 players): Average age 18.66 ± 0.87 years, average body mass 105.89 ± 10.61 kg, and average height 185 ± 8.09 cm.

Back Row (8 players): Average age 19.13 ± 0.99 years, average body mass 110.63 ± 33.45 kg, and average height 189 ± 7.86 cm.

Half-Backs (7 players): Average age 19.14 ± 1.07 years, average body mass 78.14 ± 5.39 kg, and average height 176.42 ± 5.34 cm.

Backs (6 players): Average age 18.66 ± 1.21 years, average body mass 77.67 ± 6.68 kg, and average height 178.16 ± 1.47 cm.

The division of players into the above positions was based on differences arising from the roles they performed on the field, as well as the distinct skills and physical characteristics of each player. This allowed for precise definition of each player’s tasks during the game and facilitated the interpretation of research results.

2.2. Research Tools

To measure the body parameters of the participants, the Soehnle electronic height measurement device (Soehnle, Gaildorfer Straße 6, Backnang, Germany) was used. For body mass measurements, the Tanita InnerScan®V model BC-545N device (Tanita Corporation, Maenocho, Itabashiku, Tokyo, Japan) was utilized. The reaction time test was conducted using the WittySEM system (Microgate Srl, Bolzano, Italy), which consists of 8 semaphore units. Each semaphore is equipped with an integrated LED proximity sensor that records results through hand or object proximity without the need to press any buttons.

2.3. Research Procedures

The study was conducted on 16 October 2024, at the Central Sports Center in Giżycko. The measurements took place in the morning in a room specifically designed to provide an environment conducive to focus and concentration. Participants were introduced into the room individually to eliminate any external factors that might disrupt the measurement process.

The procedure is illustrated in

Figure 1. Firstly, the Soehnle height measurement device was used to measure the height of the participants while they stood upright with their arms along their sides. Then, the participants stepped onto the Tanita InnerScan

®V BC-545N device to measure body weight. The final part of the test involved reaction time trials on the WittySEM system, consisting of 4 trials with varying levels of difficulty.

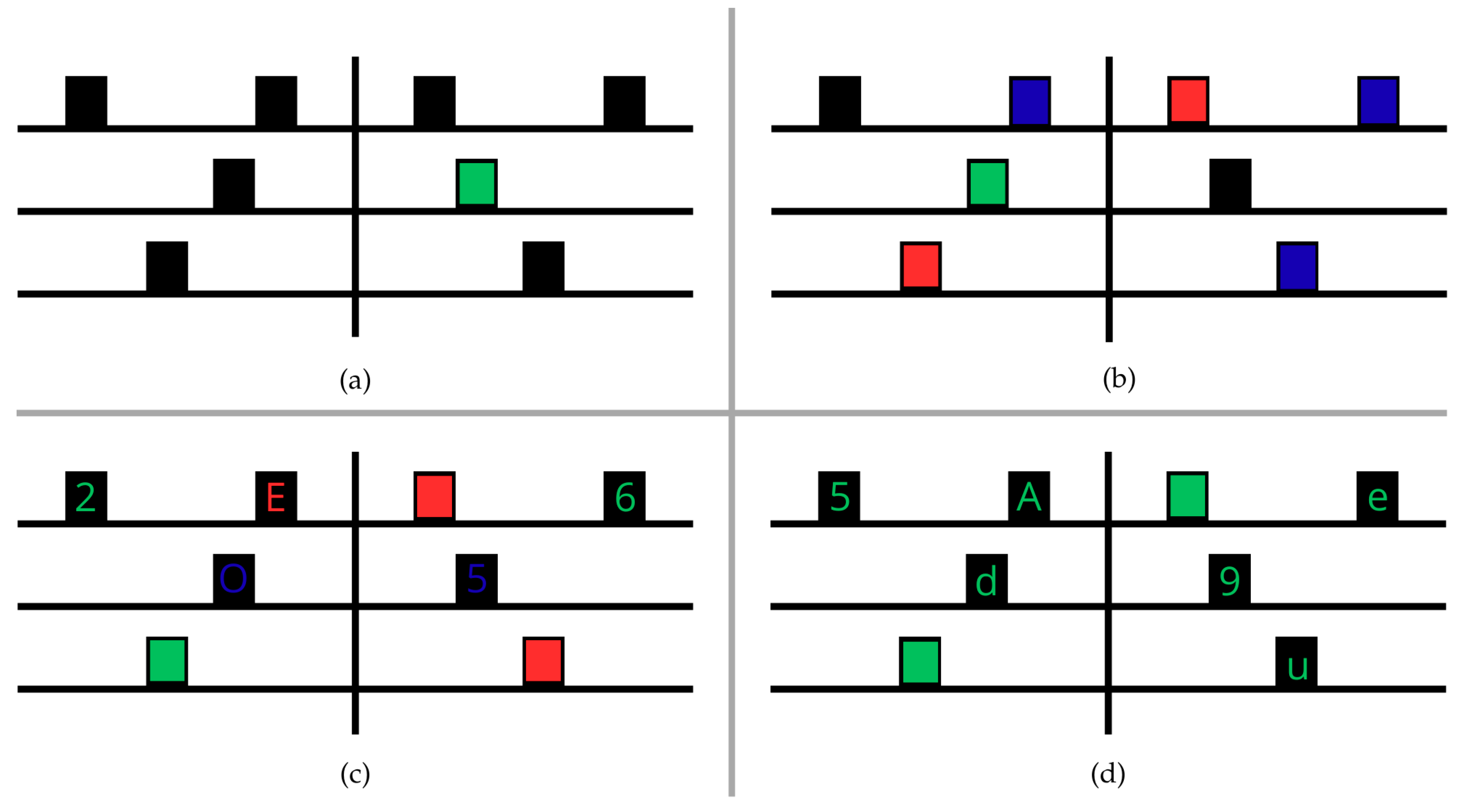

The tests used for the research (

Figure 2) consisted of the following:

Test 1 (Green): The participant reacted to the light signal of the semaphore displaying a green light. At any given moment, only one semaphore was active.

Test 2 (Multi): The participant reacted to the green light signal, while the remaining semaphores displayed lights of various colors.

Test 3 (Multi Symbol and Color): The participant was required to react to the light signal of the semaphore displaying a green light. Other semaphores presented varied combinations of colors and symbols.

Test 4 (Green “e”): The task for the participant was to react to the green letter “e”. The other semaphores displayed different symbols in the same color.

The study employed simple reaction tests (Green, Multi), in which a single stimulus and a single response were presented, and the participant reacted automatically to its appearance. Complex reaction tests (Multi Symbol and Color, Green “E”) required the identification of the correct stimulus among various elements appearing simultaneously—letters, numbers, and symbols—and the execution of an appropriate response, engaging both perception and decision-making processes.

Before conducting the study, the researcher first demonstrated each test to the participants. Immediately before each test began, participants received a verbal explanation of the procedure. They then stood a short distance from the device, and their reaction time was automatically recorded on a portable panel as they moved their hand toward the semaphore displaying the designated symbol. The tests were performed in the following order: Green test, Multi test, Multi Symbol and Color test, and Green “e” test. In each test, the participant had to bring their hand to the assigned light signal 10 times. Each light pulse appeared randomly on one of the 8 semaphores. All participants completed the tests sequentially, starting with the easiest task and progressing to more difficult ones, ensuring that no participant performed all tests at once or in a random order.

During the test, the total time from the moment the first pulse was displayed until the last pulse was identified was recorded, as well as the times between individual pulses.

2.4. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.0 (Statsoft, Kraków, Poland). As the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for further analysis, along with a two-tailed test with Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons. Both total completion times and inter-pulse times were analyzed. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes (η2, eta squared) were calculated to evaluate the practical significance of the results. This choice of tests ensures that the statistical analysis is appropriate for the data distribution and provides clarity on how the results were obtained.

3. Results

Analyzing the conducted tests, differences were found in the results between scrum halves, backs, and back-row forwards across the various tests.

In the first and last tests (

Table 1), scrum halves achieved the best results, while back-row forwards had the slowest reaction times. In the second and third tests, scrum halves performed the weakest, whereas back-row forwards achieved the best results in the second test, and both back-row forwards and backs during a 15-a-side rugby match. Both tests demonstrated large effect sizes, highlighting significant differences between the analyzed player groups.

The fastest reaction times of the scrum halves in the Green test (

Table 2) correlated with their on-field responsibilities. When restarting play, the scrum half can pass the ball, kick it, or run with it. Their reaction time and speed in executing these actions directly influence the pace of the team’s play. If the scrum half is too slow or makes the wrong decision, the opponents gain more time to organize their defense, reducing the attacking team’s chances of quickly advancing past the advantage line and scoring points.

In defense, the scrum half is the main organizer of the “first defense zone.” Their role is to observe the opponent’s offensive play and react and respond to exploit opportunities while covering defensive gaps. Therefore, the scrum half must have the fastest reaction time in the early stages of play (Green test—

Table 2) and be able to maintain a broader field of vision and react to the changing situation on the field (Green “e” test—

Table 3). The results of both tests were statistically significant compared to those of the back-row forwards and backs.

After receiving the ball from the scrum half, the fly half executes a play previously planned with the attacking or forward players, often involving the back-row forwards. The fly half may also adjust their decision in real time if the circumstances allow for a more effective play. The fly half serves as the team’s primary playmaker, with responsibility to initiate the offensive action effectively.

In the later phases of the game, depending on the fly half’s decisions, the back-row forwards, backs, or front-row forwards take over the action. Throughout the later phases of the game, depending on the fly half’s decisions, the back-row forwards, backs, or front-row forwards take over the action. Throughout these phases, the scrum halves and fly halves organize subsequent offensive actions, though they are not directly involved in the central play unless they choose to engage and attempt to break through the defensive line.

Back-row forwards and backs, excluding the scrum halves, are involved in the central phases of the rugby action. Their main goal, after receiving the ball from the scrum half or fly half, is to gain territory through penetrative play or to distribute the ball to the outer zones of the field. They execute the actions planned for them by the scrum halves during the attack. For back-row forwards and backs, the period when the play is executed and the offensive phases unfold is the most intense part of the game, requiring quick reactions.

Scrum halves and fly halves focus on organizing the next phases based on observing the opponent’s defensive setup and their own team’s readiness. They concentrate on starting the planned action as quickly as possible.

Thus, in 15-a-side rugby, the role of back-row forwards and backs is invaluable. Even if the scrum halves choose the optimal way to execute the play and pass the ball quickly, without the support of their teammates, their actions would be ineffective. After completing one phase of play, back-row forwards and backs return to their designated positions or move to where the scrum half requires. This requires speed, anticipation, and good reaction times from the players.

Another aspect supports the claim that the results of the tests (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6) reflect the players’ roles on the field. In defensive team play in rugby, analyses show that the greatest burden falls on back-row forwards and backs, while scrum halves act more organizers of the defensive play than its executors. This is clearly evident in the statistics of tackles. Back-row forwards perform an average of 13 tackles per match, the main organizer of the defensive play [

3]. Both tests revealed large effect sizes, indicating pronounced and meaningful differences between the analyzed player groups.

Back-row forwards make so many tackles because part of their task is to defend their own scrum halves against the opponent’s attacks. One of the key goals of the attacking team is to force the scrum halves to make as many tackles as possible. The high volume of physical contact tires the scrum halves, weakening their decision-making abilities, which is critical since, as mentioned earlier, they are the “brains” of the team. During opponent offensive phases, the quick reaction time of back-row forwards and backs allows them to close the distance to the opponent and execute a more effective defense.

4. Discussion

In research on reaction time in athletes, there is an increasing emphasis on integrated training methods that develop not only physical fitness but also cognitive and neuromotor skills. This is supported by studies such as those by Tomaszewski et al., who demonstrated that incorporating elements of Eastern techniques, such as Tai Chi, into comprehensive rehabilitation programs led to significant improvements in neuromuscular function and participants’ quality of life [

12].

The present study on the analysis of reaction time in 15-a-side rugby players, taking into consideration positional distinctions, provides insights into the positional requirements of this sport. The results obtained using the WittySEM system on a group of 30 Polish U20 national team players offer valuable information on the differences in reaction time between the various formations. The study highlights a novel link between players’ reaction time, positional demands, and game effectiveness across different formations. The findings provide practical guidance for training, player selection, and tactical planning, enabling drills and formations to be tailored to maximize team performance.

The anthropometric differences observed in this study between playing positions (

Figure 3) confirm findings in the global literature. Stoop et al., in their systematic review, also reported that forwards are significantly heavier and taller than players from the backline. This aligns with the results presented in this study, where front-row (105.89 kg) and back-row (110.63 kg) players significantly outweigh the scrum halves (78.14 kg) and backs (77.67 kg) [

13].

Research by Dubois et al. on professional rugby union players showed that backs cover greater distances at higher speeds than forwards, whereas forwards run more in moderate-speed zones. These differences in physical demands correlate with the results of the present study, in which reaction time profiles vary by position, reflecting their tactical roles [

14].

The findings of Glassbrock et al. on professional rugby union players showed similar trends differentiating forwards from backs in terms of running intensity [

15].

Meanwhile, Donkin et al., in their study on South African university rugby players, showed that scrum halves cover the longest total distance (6620.9 ± 784.4 m) and exhibit the highest match intensity (77.7 ± 11.6 m/min). These results highlight the unique role of scrum halves as the most actively involved players on the field, which is reflected by their superior performance in simple reaction tests [

16]. These findings are confirmed by the results obtained in this study.

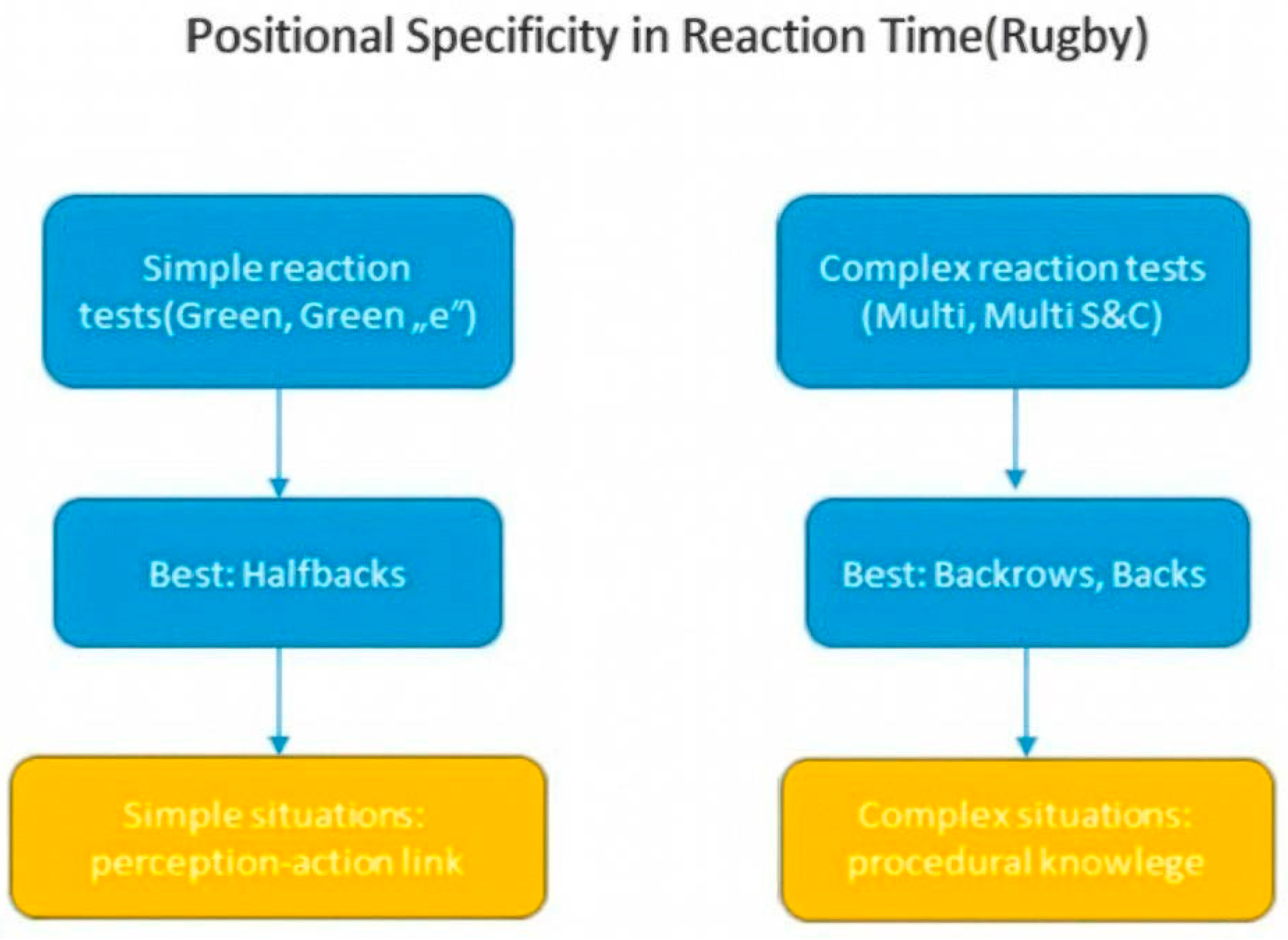

A key finding of this study (

Figure 4) is that scrum halves perform best in simple reaction tests (Green, Green “e”), while back-row forwards and backs outperform them in complex tests (Multi, Multi S&C). This pattern is supported by Ashford et al., who, in their analysis of decision-making mechanisms in rugby, found that different match situations require distinct cognitive processes. In more complex situations, players rely more frequently on procedural knowledge, while in simpler situations, they use a direct link between perception and action [

17].

The results correlating with the tactical roles of different positions are supported by the study of Ceylan et al., who analyzed differences in reaction time between offensive and defensive positions in American football. Offensive players exhibited significantly shorter visual reaction times compared to defensive players, which may be related to different cognitive-decisional demands depending on their position on the field [

18].

The defensive statistics presented in the current study (back-row forwards: 13 tackles/match, fly half: 7–8 tackles, and scrum half: 3–4 tackles) are further supported by analysis of decision-making by players in different positions in Rugby League (13-player version of rugby). The study showed that back-row forwards are required to make the highest number of defensive decisions during a match, which may explain their superior performance in complex reaction tests [

19]. The results of this present study confirm these findings.

A key value of the study is the functional interpretation of the results in a tactical context. While most research focuses on the general differences between forwards and backs, this study provides a more detailed breakdown. Back-row forwards, despite belonging to the forward formation, display reaction patterns more similar to those of backs in complex tests, reflecting their hybrid role as a “bridge” between the two formations.

Studies on decision-making in Rugby League show that players in different positions are exposed to different types of decision-making situations. Back-row forwards experience the highest number of complex situations (e.g., a two-on-one advantage), while, for example, wings have the least exposure to such situations. This may explain why, in the present study, back-row forwards performed better in complex tests [

19].

In the analysis of athletes’ motor abilities, it is important to account for changes occurring throughout the training season, which can affect reaction time, explosive power, and neuromuscular coordination. Jaszczur-Nowicki et al. demonstrated that jumping parameters, a key indicator of neuromuscular dynamics, fluctuate significantly depending on the phase of the season [

20]. In the context of reaction time studies in rugby players, a similar phenomenon may indicate the need to monitor neuromotor response variability within the training cycle. Regular measurements of reaction time can provide valuable insights into the current state of the neuromuscular system, starting readiness, and the effectiveness of training methods employed.

Application of Research Results to Training and Selection:

Specific Training Tailored to Player Positions: Based on the results of this study, specific training recommendations can be made. Scrum halves should focus on simple, quick reactions, while back-row forwards and backs require training in complex decision-making situations. Studies by Pojskić et al. confirm that players in agility-demanding sports show faster reaction times in complex motor tasks [

21].

Player Selection: The study provides selection criteria based on scientific evidence. Candidates for the scrum-half position should demonstrate a quick simple reaction time, while future back-row forwards need to have good responses in multi-element situations. This approach is supported by research by Santos et al., who found a strong correlation between physical fitness parameters and reaction time in football players [

22].

Tactical Periodization: The results confirm the concept of tactical periodization, where specific positional requirements are incorporated into training planning. The study by Hu et al. conducted on professional Rugby Union players confirms the importance of individualization in the training process based on the tasks on the field [

23].