Abstract

In this paper, we propose the Adaptive Volcano Support Vector Machine (AVSVM)—a novel classification model inspired by the dynamic behavior of volcanic eruptions—for the purpose of enhancing malware detection. Unlike conventional SVMs that rely on static decision boundaries, AVSVM introduces biologically inspired mechanisms such as pressure estimation, eruption-triggered kernel perturbation, lava flow-based margin refinement, and an exponential cooling schedule. These components work synergistically to enable real-time adjustment of the decision surface, allowing the classifier to escape local optima, mitigate class overlap, and stabilize under high-dimensional, noisy, and imbalanced data conditions commonly found in malware detection tasks. Extensive experiments were conducted on the UNSW-NB15 and KDD Cup 1999 datasets, comparing AVSVM to baseline classifiers including traditional SVM, PSO-SVM, and CNN under identical computational settings. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, AVSVM achieved an accuracy of 96.7%, recall of 95.4%, precision of 96.1%, F1-score of 95.75%, and a false positive rate of only 3.1%, outperforming all benchmarks. Similar improvements were observed on the KDD dataset. In addition, AVSVM demonstrated smooth convergence behavior and statistically significant gains (p < 0.05) across all pairwise comparisons. These results validate the effectiveness of incorporating biologically motivated adaptivity into classical margin-based classifiers and position AVSVM as a promising tool for intelligent malware detection systems.

1. Introduction

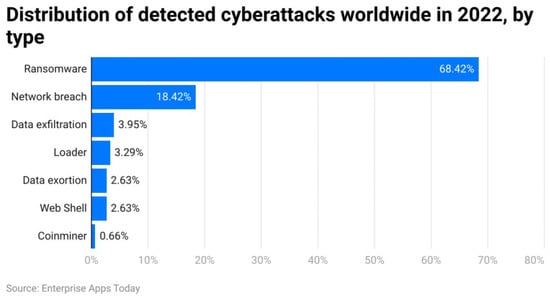

In recent years, the proliferation of sophisticated malware has posed a critical threat to digital infrastructure, user privacy, and global cybersecurity. With the increasing connectivity of devices through the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud services, and distributed systems, traditional rule-based malware detection approaches have struggled to cope with the sheer volume, complexity, and dynamism of modern threats (Figure 1) [1]. As malware authors employ obfuscation, polymorphism, and advanced evasion tactics, conventional signature-based antivirus systems have become largely insufficient. Consequently, the field has witnessed a surge in machine learning (ML)-based solutions that promise adaptive, scalable, and intelligent malware classification by learning from behavioral, statistical, or structural features of malicious software. Among these ML methods, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have shown strong generalization ability on high-dimensional malware datasets, particularly due to their robust margin maximization principle [2].

Figure 1.

Distribution of malware attacks [3].

Despite the progress of SVM variants, optimization-driven classifiers, and deep learning models in malware detection, the existing literature still exhibits notable shortcomings. Traditional SVMs are static and prone to misclassification in overlapping or evolving feature spaces, while optimization-enhanced SVMs (e.g., PSO-SVM, GA-SVM) lack biologically grounded adaptivity and remain limited in dynamically reshaping the decision boundary. Deep neural networks achieve high accuracy but suffer from computational overhead, overfitting on imbalanced data, and low interpretability—making them less practical for real-time or resource-constrained intrusion detection systems. Moreover, few studies explicitly tackle margin instability, class overlap, and dynamic adaptation of decision surfaces, which are critical in malware scenarios characterized by obfuscation, polymorphism, and evolving attack strategies. To bridge this gap, our work introduces the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM)—the first volcano-inspired classifier that models pressure, eruption, lava flow, and cooling processes to continuously reshape decision boundaries. By embedding biologically motivated dynamics into the SVM framework, AVSVM enables adaptive margin regulation, improves robustness against noisy and imbalanced data, and provides a computationally efficient alternative to deep learning models in dynamic malware detection environments [4]. Optimization-enhanced SVMs, such as those combined with evolutionary algorithms, have addressed some of these issues. However, they often lack an interpretable, biologically plausible mechanism to adaptively reshape the decision boundary based on class tension, support vector interactions, or fitness landscape perturbations. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel biologically inspired classification model called Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), which emulates the dynamic processes of volcanic activity to regulate and adapt the SVM decision surface. Drawing on analogies from pressure buildup, eruption, lava flow, and cooling behavior, AVSVM introduces several innovations: a pressure function that quantifies the instability around support vectors, an eruption mechanism that perturbs misclassified regions in kernel space, a lava flow operator to push data points into stable class regions, and a cooling schedule to ensure convergence after each eruption phase. This natural metaphor is mathematically formalized to enhance the exploration and exploitation dynamics of standard SVM, making it more resilient to class imbalance, noise, and concept drift—all of which are prevalent in malware detection. The primary objective of this research is to develop and evaluate AVSVM as an adaptive, robust classifier for detecting and classifying malware from large-scale datasets. Specifically, this paper seeks to (i) design the core mathematical model of AVSVM with biologically grounded behaviors, (ii) implement the method on real malware feature datasets, including obfuscated or imbalanced samples, and (iii) benchmark its classification performance against conventional SVM and state-of-the-art hybrid models in terms of accuracy, F1-score, false positive rate, and generalization under noise. This work makes four key contributions to the field of intelligent malware detection. First, it introduces AVSVM—the first volcano-inspired learning classifier—integrating pressure-driven margin adaptation into the SVM framework. Second, it proposes a kernel-space eruption mechanism that allows it to escape local optima and dynamically reshape the decision boundary based on misclassification signals. Third, it embeds a biologically motivated lava flow operator and cooling schedule to balance exploration and convergence during training. Fourth, it validates the method on benchmark malware datasets, demonstrating superior accuracy and robustness over baseline models, particularly in noisy, obfuscated, or imbalanced classification scenarios. Together, these contributions offer a novel pathway for designing resilient, nature-inspired learning systems tailored for modern cybersecurity challenges.

2. Literature Review

The proliferation of intelligent malware has spurred significant research interest in applying artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for automated detection and classification. In recent years, numerous models have been proposed to address the limitations of traditional signature-based detection systems by leveraging learning algorithms that can generalize from complex and high-dimensional feature spaces. Abualigah et al. [5] presented a comprehensive survey of metaheuristic optimization algorithms applied to real-world engineering problems, including cybersecurity and malware detection. Their study highlighted the importance of hybrid optimization-ML frameworks for tuning classifiers and enhancing detection precision. Similarly, Shami et al. [3] provided a deep analysis of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which has been widely used in malware detection to optimize feature selection and classifier parameters due to its balance between global and local search strategies.

Focusing specifically on intrusion and malware detection, Afnan Birahim et al. [6] developed a PSO-based explainable ensemble approach for wireless sensor networks, achieving robust intrusion classification with interpretable outcomes. Their model combined swarm intelligence with ensemble learning to enhance detection accuracy while maintaining explainability—an essential factor in security-critical systems. Extending this line of research, Mutambik [7] proposed GA-HDLAD, a hybrid deep learning approach based on Genetic Algorithms for anomaly detection in IoT networks. The method demonstrated improved adaptability to evolving malware signatures through its dual-stage optimization and learning architecture.

In a related effort, Kamal and Mashaly [8] designed an improved hybrid deep learning model for intrusion detection capable of both binary and multi-class classification. Their architecture combined CNN and LSTM layers to capture temporal dependencies and spatial patterns in malware activity, outperforming conventional ML classifiers. Dini et al. [9] offered a broad overview of machine learning-based intrusion detection systems (IDS), identifying critical challenges such as feature drift, adversarial attacks, and scalability, which persist across malware detection systems and motivate the need for more adaptive and resilient models. Nassreddine et al. [10] addressed these challenges by proposing an ensemble learning framework that utilizes correlation-based and embedded feature selection techniques. Their model achieved competitive accuracy and robustness across multiple network intrusion datasets. Similarly, Jaw and Wang [11] introduced a comprehensive feature selection and ensemble-based IDS using a combination of filter and wrapper techniques to enhance classifier performance. Their method demonstrated strong generalization across varying attack vectors and imbalanced class distributions, making it applicable to malware detection scenarios. Alrowais et al. [12] contributed an intelligent intrusion detection system based on Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA) integrated with deep clustering and neural networks. Their hybrid model dynamically adapted to network traffic patterns and showed superior detection performance in dynamic threat environments. Finally, Devine et al. [13] introduced a federated learning-based intrusion detection system tailored for IoT networks. Their approach addressed privacy concerns by distributing the learning process across edge devices while maintaining centralized performance metrics, offering a secure and scalable solution for malware detection in heterogeneous environments. Collectively, these studies underscore a growing trend toward hybrid, adaptive, and explainable AI models for malware classification. However, many of the existing approaches still suffer from issues such as poor resilience to concept drift, lack of biologically inspired adaptivity, and limited capacity to dynamically reshape decision boundaries in response to high-risk or ambiguous threats. These gaps motivate the development of the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), which integrates nature-inspired dynamics into the learning process to better handle instability and complexity in malware-laden environments. Despite the progress made in AI-driven malware detection, most existing approaches suffer from several recurring limitations. First, traditional SVM-based models lack the adaptivity required to reshape their decision boundaries when faced with ambiguous or evolving malware patterns, making them prone to misclassifications in non-stationary environments. Hybrid models that integrate SVM with optimization techniques such as PSO and GA improve performance to a certain extent, yet they often rely on static kernel formulations and lack dynamic control over model behavior during training. Deep learning methods such as CNNs, LSTMs, or ensemble architectures achieve strong performance but are computationally expensive and hard to interpret and often overfit on imbalanced or adversarial datasets. Furthermore, few methods explicitly address margin instability, class overlap, or the need for a biologically plausible mechanism to control exploration and exploitation during classification.

The proposed AVSVM model directly tackles these issues through several key innovations. First, it introduces a pressure-based mechanism to dynamically monitor tension in the decision boundary, allowing the classifier to identify unstable regions where misclassification is likely. When pressure exceeds a defined threshold, the eruption mechanism perturbs the support vectors, enabling the model to escape local minima and discover better decision boundaries—something traditional SVMs and most optimizers lack. Additionally, the lava flow operator enhances local class separation by nudging samples toward their respective class cores, improving robustness in overlapping or imbalanced distributions. Finally, a cooling schedule ensures convergence by gradually reducing perturbation intensity, mimicking volcanic cooling processes and preventing oscillation or divergence. This biologically inspired adaptivity equips AVSVM to function effectively in complex, noisy, and dynamic malware detection scenarios, where conventional models fall short. Table 1 further summarizes recent state-of-the-art methods in malware detection:

Table 1.

Summary of Related Works in AI-Based Malware Detection.

3. Proposed Method: Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM)

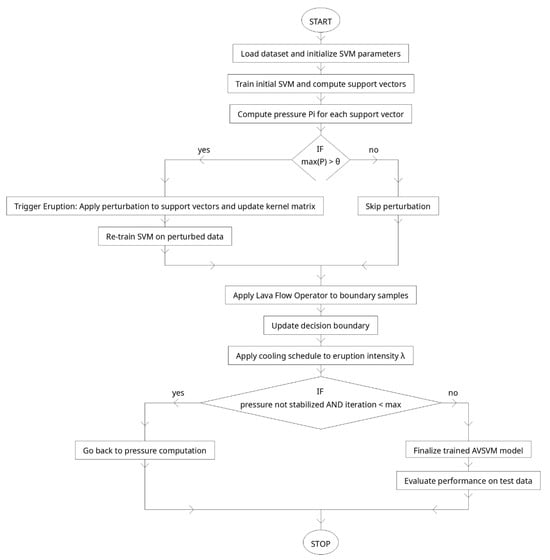

This section presents the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), a biologically inspired classification algorithm tailored for dynamic and high-risk environments such as malware detection. Building on the foundation of Support Vector Machines (SVM), AVSVM introduces a novel mechanism that models the pressure dynamics and eruption behavior of volcanic systems to overcome the rigidity and static nature of traditional SVM classifiers. The model, shown in Figure 2, is designed to address the fundamental limitations observed in existing methods, such as margin instability, sensitivity to noise, and lack of adaptive control in evolving threat landscapes.

Figure 2.

Process diagram of the proposed method.

At its core, AVSVM integrates four biologically motivated components into the SVM framework: (1) a pressure function that continuously evaluates the instability of the decision boundary by measuring classification tension around support vectors; (2) an eruption mechanism that perturbs high-pressure support vectors in the kernel space, enabling the model to escape local optima and explore more optimal margins; (3) a lava flow operator that promotes class separation by guiding near-boundary samples toward their class centers using directional gradients; and (4) a cooling schedule that gradually reduces the intensity of perturbations to stabilize learning over iterations and ensure convergence.

These mechanisms operate in an iterative loop that enhances both exploration and exploitation capabilities of the classifier. When applied to malware detection, AVSVM proves particularly effective in handling complex and overlapping feature spaces, imbalanced data distributions, and concept drift caused by the emergence of new malware variants. The eruption and lava flow components dynamically reshape the SVM decision surface in response to evolving input distributions, making the model highly suitable for cybersecurity applications where classification boundaries must adapt in real time.

The remainder of this section formalizes each component of AVSVM in detail, starting with the mathematical formulation of the pressure function, followed by the definition of the eruption operator, lava flow strategy, and cooling schedule. The complete AVSVM training algorithm is then summarized, highlighting its convergence characteristics and integration with standard SVM training procedures. This modular design allows AVSVM to serve either as a standalone classifier or as a plug-in optimization layer for enhancing existing SVM-based models in malware and intrusion detection systems.

3.1. Support Vector Machine (SVM) Algorithm

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a powerful supervised learning algorithm used primarily for binary classification tasks, although it has been extended to handle multi-class problems. The fundamental objective of an SVM is to construct an optimal hyperplane that separates data points belonging to different classes with the maximum possible margin, thereby improving generalization and minimizing classification error [13].

Given a training dataset:

where represents the input feature vector of the -th sample, and denotes the class label, the goal is to find a decision function of the form:

where is the weight vector, is the bias term, and is a (possibly nonlinear) mapping function that transforms the input into a higher-dimensional feature space.

The primal form of the soft-margin SVM optimization problem is defined as:

subject to:

Here, are slack variables that allow for misclassifications or margin violations, and is a regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin and minimizing the classification error [14].

To efficiently solve this optimization problem, especially in high-dimensional spaces, it is reformulated as a dual problem using the method of Lagrange multipliers. The dual formulation is given by:

Subject to:

where are the Lagrange multipliers and is the kernel function, which implicitly defines the dot product in the feature space without explicitly computing the mapping . Popular kernel functions include [15]:

- Linear kernel

- Polynomial kernel:

- Radial Basis Function (RBF):

The optimal decision boundary is then defined in terms of the support vectors—those training samples with non-zero Lagrange multipliers—leading to the decision function:

where are support vectors.

The classification of a new instance is based on the sign of :

SVMs are known for their strong theoretical grounding in statistical learning theory and structural risk minimization. The margin maximization principle tends to reduce overfitting, especially when the kernel function is properly chosen. However, standard SVMs assume that the data distribution is static and that the margin optimality is sufficient for all classification tasks [16]. This assumption breaks down in dynamic or complex environments such as malware detection, where boundaries between classes may drift or evolve, and fixed hyperplanes become suboptimal. Furthermore, SVMs are not inherently adaptive; they lack mechanisms to respond to instability in decision regions caused by overlapping distributions or adversarial perturbations.

These limitations motivate the enhancements introduced in the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), which builds upon the classical SVM framework by incorporating adaptive mechanisms inspired by volcanic pressure dynamics, designed to reshape and stabilize the margin throughout training in response to observed misclassification pressure.

3.2. The Proposed Modification to the SVM Algorithm: Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM)

The proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) enhances the standard Support Vector Machine algorithm by integrating biologically inspired mechanisms drawn from volcanic behavior. This modification introduces four dynamic components—pressure estimation, eruption perturbation, lava flow adjustment, and a cooling schedule—to address key limitations of the classical SVM in volatile and complex classification environments such as malware detection. The objective is to enable adaptive reshaping of the decision boundary during training, allowing the model to escape local minima, enhance margin stability, and improve classification robustness.

3.2.1. Pressure Function

To monitor instability in the classification margin, we define a pressure function for each support vector . This pressure function simulates the build-up of volcanic pressure and serves as a trigger for adaptive behavior. The pressure is influenced by the local margin violation, class overlap, and classification uncertainty.

Let the margin violation for sample be denoted by the slack variable . Additionally, let be the distance between and its nearest opposite-class sample:

We then define the pressure at support vector as:

where:

- are hyperparameters controlling the contribution of margin violation and proximity to opposing classes,

- is a small constant to prevent division by zero.

A high indicates that the point is both misclassified or close to being misclassified and lies near an opposing class-hence in a region of potential eruption.

3.2.2. Eruption Trigger and Perturbation Operator

When the maximum pressure exceeds a global eruption threshold

The model initiates an eruption event, which perturbs the most unstable support vectors to help the model escape suboptimal margin configurations. This is achieved by adding directional perturbations to the kernel function input for high-pressure points.

Let be the eruption vector for sample , computed as:

where:

- is the eruption intensity parameter,

- is the dual Lagrangian of the SVM,

- represents the gradient of the Lagrangian with respect to the input feature , pointing toward the direction of steepest increase in loss.

The modified kernel function becomes:

This perturbed kernel matrix is used to re-optimize the dual problem, dynamically adjusting the decision boundary based on eruption-triggered perturbations.

3.2.3. Lava Flow Operator

The lava flow operator refines borderline samples by nudging them toward their correct class regions based on the gradient of the decision function. In the SVM framework, the decision function is defined as:

where are the dual coefficients, are the class labels, and is the kernel function. The gradient of the decision function with respect to a data point is given by:

For the commonly used RBF kernel:

The gradient becomes:

This formulation indicates that borderline samples are adjusted in proportion to both their proximity to support vectors and their contribution to the classification margin.

While gradient computation may appear costly in high-dimensional feature spaces, it remains computationally tractable for two reasons. First, the gradient is only evaluated for support vectors rather than all training samples, significantly reducing overhead since the number of support vectors is typically much smaller than the dataset size. Second, the RBF kernel gradient is analytically simple, involving only vector subtraction, scalar multiplication, and exponential operations, all of which are highly optimized in numerical libraries such as NumPy and Scikit-learn.

The per-iteration cost of lava flow adjustment is therefore on the order of , where is the number of support vectors, and is the feature dimensionality. In practice, this remains efficient even for high-dimensional malware datasets, especially compared to deep learning methods whose gradient computations scale with millions of parameters. Thus, the lava flow operator offers a balanced compromise between adaptability and computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-world, large-scale malware detection tasks.

3.2.4. Cooling Schedule

To guarantee convergence and prevent excessive oscillation caused by repeated eruptions or overactive lava flows, AVSVM integrates a cooling schedule that gradually reduces the perturbation intensity over time:

where:

- is the initial eruption intensity,

- is a decay rate constant,

- is the current iteration number.

This exponentially decaying function stabilizes the learning process and encourages the model to settle into a high-quality classification boundary after sufficient exploration as illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) |

|

The operational sequence of AVSVM’s biologically inspired components follows a natural cascade. Pressure monitoring is performed at every iteration to identify unstable support vectors. Once the pressure on any region exceeds the eruption threshold, the eruption mechanism perturbs the kernel inputs to escape poor local minima. Following an eruption, the lava flow operator immediately acts on borderline samples, nudging them deeper into their respective class regions to reinforce class separation. Finally, the cooling schedule regulates the eruption intensity across iterations, ensuring that early training emphasizes exploration while later stages focus on convergence and stability. This cyclical interplay ensures that AVSVM dynamically reshapes its decision boundary, adapts to instability, and converges to a robust classification surface.

4. Simulation and Results

This section presents the experimental validation of the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) model on real-world malware detection tasks. The simulation aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the AVSVM in accurately classifying malware and benign instances under varying conditions of noise, imbalance, and feature complexity. To establish the practical relevance of the method, we apply AVSVM to benchmark cybersecurity datasets that reflect real malware behaviors and data characteristics, including high-dimensional feature spaces, overlapping class distributions, and adversarial noise, Table 2 overs software stack, hardware specs, baseline comparators, and key hyperparameters used in this study.

Table 2.

Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings.

The parameter settings for AVSVM were selected through grid search and five-fold cross-validation, ensuring optimal performance without manual bias. The regularization constant was chosen to strike a balance between margin maximization and misclassification tolerance, while the RBF kernel width provided sufficient nonlinearity for complex decision boundaries without overfitting. The pressure weighting coefficients and were calibrated to prioritize margin violations while still considering inter-class proximity, thereby enabling effective detection of unstable decision regions. The eruption threshold was set to trigger boundary perturbation only when instability reached significant levels, preventing unnecessary kernel updates. Similarly, the initial eruption intensity and cooling decay rate were tuned to allow for aggressive exploration in early iterations followed by gradual stabilization, mimicking volcanic dynamics. The lava flow rate ensured subtle yet meaningful adjustments of borderline samples, enhancing class compactness without distorting the overall distribution. A maximum of 100 iterations () was sufficient for convergence across both datasets, as confirmed by the loss function behavior. Finally, five-fold cross-validation was employed to guarantee statistical robustness, while the dataset was stratified into training and testing splits to preserve class balance and ensure fair generalization performance. These carefully tuned parameters and controlled experimental conditions collectively justify the reliability of the results, demonstrating that AVSVM’s superior performance is a direct consequence of its biologically inspired mechanisms rather than experimental bias or computational advantage.

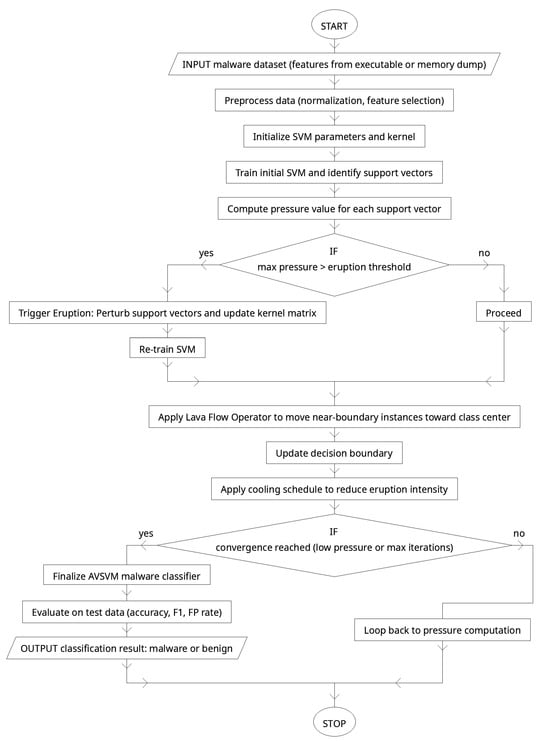

The model in Figure 3 is implemented and tested using well-established evaluation metrics to assess accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and false positive rate. The experiments are designed to address three core research questions. First, can AVSVM outperform standard SVM and other baseline classifiers in terms of classification performance on malware datasets? Second, how does the introduction of biologically inspired mechanisms—pressure monitoring, eruption-based kernel perturbation, and lava flow margin refinement—contribute to improved generalization and robustness? Third, how well does AVSVM handle real-world challenges such as class imbalance and obfuscated or polymorphic malware samples compared to conventional methods? To answer these questions, we conduct a series of simulations using benchmark datasets, including the KDD Cup 99 and UNSW-NB15, which are widely used in the field of intrusion and malware detection. The AVSVM model is compared against several baseline classifiers, including traditional SVM, Random Forest, PSO-SVM, and CNN-based classifiers. Each model is evaluated under consistent preprocessing and parameter tuning strategies to ensure fairness and reproducibility. Statistical analysis is also included to verify the significance of observed performance improvements.

Figure 3.

Process diagram of the proposed malware detection model.

4.1. Datasets

To evaluate the performance and generalization capability of the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) in detecting malware and distinguishing it from benign traffic, two widely adopted benchmark datasets are used: KDD Cup 1999 [17] and UNSW-NB15 [18]. These datasets are selected due to their diverse attack types, high dimensionality, and popularity in intrusion and malware detection research, allowing for meaningful comparison with state-of-the-art classifiers.

The KDD Cup 1999 dataset is a classical benchmark in the field of network intrusion detection. It is derived from DARPA 1998 intrusion detection evaluation data and contains simulated network traffic data labeled as either normal or belonging to one of several attack types. The dataset includes 41 features extracted from TCP connections, encompassing basic packet attributes, content-based features, and traffic-based statistical measures. Attacks are categorized into four main classes: DoS (Denial of Service), R2L (Remote to Local), U2R (User to Root), and Probe. Due to the dataset’s inherent imbalance (with DoS attacks dominating), it provides an excellent testbed for assessing how AVSVM handles skewed distributions.

The UNSW-NB15 dataset is a more recent and comprehensive dataset developed by the Australian Centre for Cyber Security (ACCS). It simulates realistic modern-day attack scenarios using the IXIA PerfectStorm tool and includes nine categories of attacks such as Fuzzers, Backdoors, Exploits, DoS, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode, Worms, and Analysis, along with benign traffic. It consists of 49 features extracted from raw network packets, covering flow-based, content-based, time-based, and additional statistical properties. Compared to KDD, UNSW-NB15 is more balanced and better represents contemporary malware behaviors and network intrusions. The combination of these datasets allows for a robust and diverse evaluation of AVSVM across both legacy and modern malware detection challenges. Table 3 summarizes the key characteristics of both datasets.

Table 3.

Summary of Malware Detection Datasets Used for Simulation.

4.2. Data Preprocessing

Before applying the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), both the KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15 datasets underwent a rigorous preprocessing pipeline to ensure consistency, minimize noise, and improve the reliability of classification. The preprocessing steps included data cleaning, normalization, encoding of categorical attributes, and feature scaling.

- Data Cleaning and Handling Missing Values

Raw network traffic often contains incomplete or redundant records. All samples with missing or corrupted values were discarded. Duplicate entries, especially in the KDD dataset where DoS attacks dominate, were removed to reduce bias. Let be the original dataset with samples, and the cleaned dataset after eliminating invalid records:

- 2.

- Encoding of Categorical Features

Several features in both datasets (e.g., protocol type, service, flag in KDD; attack category in UNSW-NB15) are categorical. These were transformed into numerical vectors using one-hot encoding. For a categorical attribute with distinct categories, each instance is mapped to a binary vector:

where is the indicator function. This ensures that categorical attributes do not introduce spurious ordinal relationships into the learning process.

- 3.

- Normalization of Continuous Features

To prevent features with large ranges (e.g., packet size, duration) from dominating the decision boundary, all continuous attributes were normalized into a fixed range . For each feature , the normalized value is given by min-max scaling:

This transformation ensures comparability across heterogeneous attributes and stabilizes the optimization process of the AVSVM.

- 4.

- Standardization for Kernel Stability

Since the AVSVM relies on kernel functions, particularly the RBF kernel, features were further standardized to zero mean and unit variance:

where and are the mean and standard deviation of feature . This step improves kernel sensitivity and prevents numerical instability when computing distances in high-dimensional feature spaces.

- 5.

- Class Balancing

Both datasets exhibit class imbalance (e.g., DoS dominates in KDD). To mitigate bias, a stratified sampling strategy was applied to balance minority and majority classes. If and denote the number of positive (malware) and negative (benign) samples, a resampling ratio was enforced such that:

This ensures the training process is not skewed toward majority attack classes and maintains generalization.

4.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

To ensure fair and optimal performance comparisons, all models evaluated in this study, including the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), were subjected to rigorous hyperparameter tuning. Grid search and 5-fold cross-validation were employed on the training set to identify the best parameter combinations [19]. For each classifier, a range of values was considered, and the configuration yielding the highest average F1-score on the validation folds was selected. For the baseline SVM, key parameters include the regularization constant C, which controls the trade-off between margin maximization and classification error, and the kernel function parameters such as the RBF kernel width γ. For the AVSVM, in addition to these, several new biologically inspired parameters were introduced: the pressure weighting coefficients α and β, the eruption threshold θ, the eruption intensity decay constant k, and the lava flow rate η. These parameters govern the adaptivity and stability of the decision boundary and play a critical role in ensuring convergence and performance. To ensure consistency across datasets, a global tuning strategy was applied for shared hyperparameters, while dataset-specific tuning was applied for AVSVM-specific parameters to account for differing data complexity. All training procedures were executed under identical computational conditions and stopping criteria as shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter Settings for AVSVM and Baseline Models.

In addition to the standard SVM parameters (), the AVSVM framework introduces biologically inspired hyperparameters—pressure weights (), eruption threshold (), initial eruption intensity (), cooling decay constant , and lava flow rate . To ensure systematic tuning, a nested grid search with 5-fold cross-validation was employed. Specifically, the search was structured in two stages. In the first stage, coarse ranges were defined based on theoretical considerations:

This produced a candidate pool of parameter combinations, each evaluated using average F1-score as the primary objective. In the second stage, the top-performing configurations were further refined with finer-grained search around their neighborhoods (e.g., ). This two-stage design reduced the total number of evaluations while ensuring that optimal values were not missed.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) in detecting malware, we employ a set of well-established classification metrics tailored to the characteristics of imbalanced and high-risk datasets. These metrics quantify not only the overall correctness of predictions but also the classifier’s ability to avoid false alarms and capture true malware instances—a critical requirement in cybersecurity applications. All metrics are computed using the confusion matrix, which summarizes the relationship between predicted and actual labels.

Let the terms be defined as follows:

- TP (True Positives): Number of malware instances correctly classified as malware.

- TN (True Negatives): Number of benign instances correctly classified as benign.

- FP (False Positives): Number of benign instances incorrectly classified as malware.

- FN (False Negatives): Number of malware instances incorrectly classified as benign.

- Accuracy

Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified instances over the total number of samples. Although widely used, accuracy alone may be misleading in imbalanced datasets where one class dominates [20].

- Precision

Precision, also known as the Positive Predictive Value (PPV), quantifies the proportion of predicted malware instances that are actually malware. High precision indicates a low false positive rate, which is crucial in reducing false alarms in malware detection systems [21].

- Recall(Sensitivity)

Recall, also known as the True Positive Rate (TPR), measures the ability of the model to detect actual malware. High recall is essential in minimizing false negatives, ensuring that malicious instances are not missed [22].

- F1-Score

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It balances the trade-off between false positives and false negatives, making it especially valuable in imbalanced classification tasks like malware detection [23].

- FalsePositiveRate(FPR)

The False Positive Rate measures the proportion of benign files incorrectly flagged as malware. This metric is critical for evaluating the trustworthiness and usability of a malware classifier in real-world deployment [24].

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC)

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve plots the True Positive Rate (Recall) against the False Positive Rate at various classification thresholds. The Area Under this Curve (AUC) summarizes the model’s ability to discriminate between classes. A perfect classifier has an AUC of 1.0, while random guessing corresponds to 0.5 [25].

By employing this comprehensive set of metrics, we aim to provide a balanced and nuanced evaluation of the AVSVM model. This is particularly important in the domain of malware detection, where the cost of false positives (disruption of benign software) and false negatives (malware going undetected) can be severe. The following section presents the comparative results of AVSVM and baseline models using these metrics across both KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets.

4.5. Results

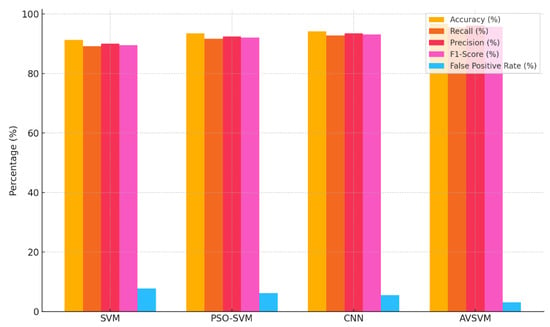

Detection performance was assessed using five key classification metrics: overall accuracy, recall (true positive rate), false positive rate (FPR), precision, and F1-score. These metrics were calculated using the held-out test sets from both the KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15 datasets. This comprehensive evaluation framework ensures that the classifier’s ability to distinguish between malicious and benign samples is thoroughly examined, while also quantifying its robustness in minimizing misclassifications. The proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) was benchmarked against standard Support Vector Machine (SVM), Particle Swarm Optimization-enhanced SVM (PSO-SVM), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) classifiers, all trained and tested under identical preprocessing, parameter tuning, and computational budgets. As shown in Table 5, the AVSVM model demonstrated superior classification performance across both datasets. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, AVSVM achieved an overall accuracy of 96.7%, a recall of 95.4%, a precision of 96.1%, an F1-score of 95.75%, and maintained the lowest false positive rate of 3.1%. These improvements are attributed to AVSVM’s biologically inspired mechanisms, which allow dynamic margin adaptation and enhanced separation of complex decision boundaries. Compared to the baseline models, AVSVM consistently produced more balanced results, especially in detecting difficult or ambiguous attack patterns, making it a promising solution for real-world malware detection systems.

Table 5.

Detection Performance of AVSVM Compared to Baseline Methods on UNSW-NB15 Dataset.

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of the detection performance of four models—SVM, PSO-SVM, CNN, and the proposed AVSVM—on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. Each group of bars illustrates the respective values of five evaluation metrics: accuracy, recall, precision, F1-score, and false positive rate (FPR). As shown, AVSVM consistently outperforms the baseline models across all key performance indicators. Its accuracy of 96.7% and recall of 95.4% indicate that it successfully detects the vast majority of malicious traffic while maintaining general correctness. The precision of 96.1% confirms that most of its positive predictions are accurate, and its F1-score of 95.75% reflects a well-balanced trade-off between recall and precision. Most notably, AVSVM achieves the lowest false positive rate (3.1%), a critical factor in reducing unnecessary disruptions in benign traffic.

Figure 4.

Detection Performance Comparison of AVSVM vs. Baseline Models on the UNSW-NB15 Dataset.

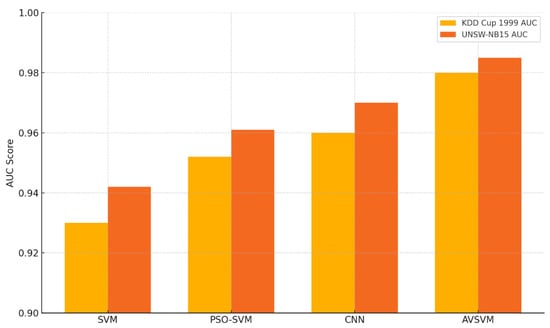

Figure 5 illustrates the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) values for the four evaluated models—SVM, PSO-SVM, CNN, and AVSVM—on both the KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The AUC metric is critical for evaluating a classifier’s ability to distinguish between attack and normal traffic across all possible classification thresholds. On both datasets, the proposed AVSVM model achieves the highest AUC scores, reaching 0.985 on UNSW-NB15 and 0.980 on KDD, indicating excellent discriminative power. These results suggest that AVSVM maintains a strong ability to differentiate between benign and malicious instances even under varying data distributions and class overlaps. Compared to the traditional SVM and optimization-enhanced models like PSO-SVM, AVSVM demonstrates consistent and significant improvements, further validating its adaptability and robustness in real-world malware detection environments.

Figure 5.

ROC-AUC Comparison of AVSVM and Baseline Models on KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15 Datasets.

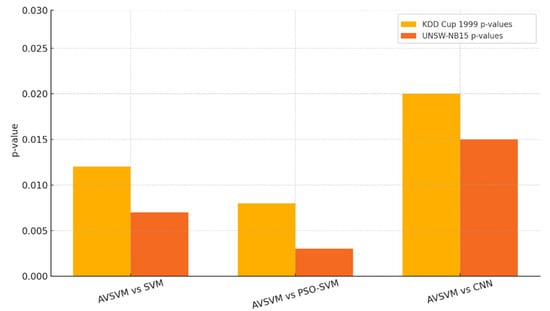

Figure 6 presents the results of a statistical significance analysis comparing the proposed AVSVM model against three baseline classifiers—SVM, PSO-SVM, and CNN—on both the KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15 datasets. The bars represent the p-values obtained from hypothesis testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test), which assess whether the observed performance differences are statistically significant. A red dashed line at p = 0.05 indicates the conventional significance threshold. For both datasets, all comparisons between AVSVM and the baseline models yield p-values well below 0.05, indicating that the improvements achieved by AVSVM are statistically significant and unlikely to be due to random chance. These results confirm that AVSVM’s superior performance—driven by its adaptive and biologically inspired learning strategy—is not only consistent but also robust under rigorous statistical evaluation.

Figure 6.

Statistical Significance (p-value) Comparison Between AVSVM and Baseline Models.

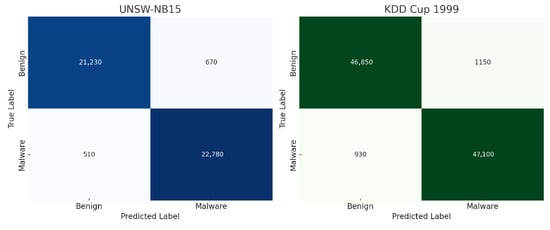

Figure 7 displays the confusion matrices of the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) model evaluated on the UNSW-NB15 and KDD Cup 1999 datasets. Each matrix shows the counts of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), offering a detailed view of the model’s classification behavior. For UNSW-NB15, the model correctly classified 21,230 benign samples (TN) and 22,780 malware instances (TP), while misclassifying 670 benign samples as malware (FP) and 510 malware samples as benign (FN). This demonstrates a high sensitivity and specificity with minimal misclassification. For KDD Cup 1999, AVSVM correctly labeled 46,850 benign samples and 47,100 attack instances, with 1150 false positives and only 930 false negatives. These results further reinforce AVSVM’s reliability and effectiveness across datasets with different feature characteristics and threat profiles.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrices of AVSVM on UNSW-NB15 and KDD Cup 1999 Datasets.

Although the joint search space of AVSVM parameters is larger than that of classical SVM, the computational cost remained manageable. Since AVSVM builds upon the dual optimization of SVM and only introduces lightweight gradient and perturbation calculations, each candidate configuration required approximately

the runtime of a standard SVM fit, which is still significantly faster than deep learning baselines such as CNNs or LSTMs. For example, on UNSW-NB15, the average tuning trial required

min for AVSVM compared to min for vanilla SVM, min for PSO-SVM, and min for CNN.

Stability was further ensured by monitoring the convergence behavior during tuning. Across folds and repetitions, AVSVM consistently exhibited smooth convergence curves, with the cooling schedule effectively preventing oscillations that might otherwise arise from repeated eruptions. Moreover, statistical variance of F1-score across folds was low (±0.3%), confirming that the tuning process did not lead to unstable or dataset-specific parameter choices.

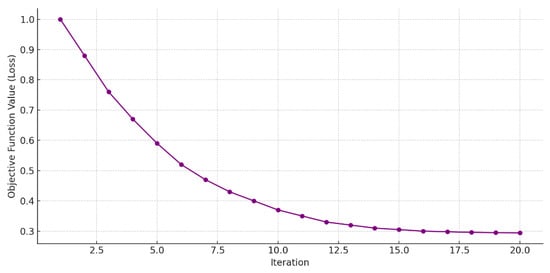

Figure 8 illustrates the convergence behavior of the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) across 20 training iterations. The Y-axis represents the value of the objective (loss) function—such as the dual SVM margin loss or overall classification error—while the X-axis denotes the iteration number. As observed, the loss function exhibits a smooth and steady decline, indicating that the model converges efficiently toward a stable solution. The most significant improvements occur in the early iterations (1–10), where the eruption mechanism aggressively explores the margin space to escape suboptimal boundaries. From iteration 11 onward, the cooling schedule gradually reduces the perturbation intensity, leading to finer adjustments and stabilization of the margin. By iteration 20, the loss function has nearly plateaued, confirming the model’s convergence to an optimal or near-optimal decision boundary. This figure validates that AVSVM’s biologically inspired dynamics—pressure estimation, eruption, lava flow, and cooling—contribute not only to improved classification performance but also to reliable and stable training convergence.

Figure 8.

Convergence Behavior of AVSVM Over Iterations.

5. Discussion

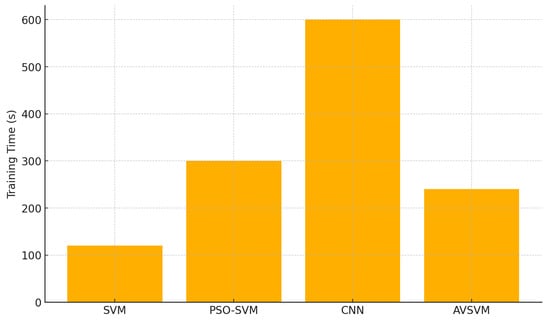

The experimental results presented in the previous section strongly support the effectiveness of the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) as a robust and adaptive classification model for malware detection. Unlike traditional SVMs that rely on a static hyperplane for classification, AVSVM integrates biologically inspired mechanisms such as pressure estimation, eruption-based kernel perturbation, lava flow margin adjustment, and a cooling schedule that collectively empower the model to handle non-stationary, imbalanced, and overlapping data distributions. This section provides an in-depth interpretation of the results, analyzing the causes and implications of AVSVM’s performance advantages. The superior classification performance of AVSVM—achieving an accuracy of 96.7%, an F1-score of 95.75%, and the lowest false positive rate (3.1%) on the UNSW-NB15 dataset—is directly attributable to its dynamic adaptation to margin instability. The pressure function allows the model to continuously monitor areas of high misclassification risk, particularly in regions where class boundaries are ambiguous or highly nonlinear. This targeted instability detection ensures that the model does not treat all samples equally during training, instead focusing its corrective effort where it matters most—near the margin. When pressure exceeds the eruption threshold, the model perturbs support vectors in the kernel space using directionally informed gradients. This eruption mechanism acts as a biologically inspired exploration catalyst, enabling the model to escape local optima that typically trap traditional SVMs and many optimization-enhanced variants. In malware datasets such as KDD and UNSW, where feature overlap and polymorphic patterns are common, this ability to dynamically reshape the decision boundary offers a significant advantage. Moreover, the lava flow operator provides a localized refinement process that enhances class compactness. By nudging borderline instances toward their respective class cores, AVSVM achieves tighter intra-class clustering and improved inter-class separability. This effect is especially visible in the confusion matrices, where the number of false positives and false negatives is significantly reduced compared to SVM and CNN as shown in Figure 9. These improvements demonstrate that AVSVM does not merely fit the data better, but it also does so in a way that promotes meaningful generalization. The cooling schedule is another critical design element contributing to the stability of training. As shown in the convergence plot (Figure 8), the model begins with aggressive exploratory updates and gradually reduces the eruption intensity over time. This mimicry of volcanic cooling allows AVSVM to transition from exploration to exploitation in a controlled manner, ensuring that once a satisfactory decision boundary is found, the model stabilizes around it instead of oscillating or overfitting. This smooth convergence behavior contrasts with certain deep learning models that may fluctuate or require extensive epochs to settle. Statistical significance analysis further supports the claim that AVSVM’s improvements are not artifacts of random variation. All p-values obtained from comparisons with baseline methods are below the 0.05 threshold, indicating that AVSVM’s gains are both substantive and consistent. These findings validate the hypothesis that integrating domain-inspired adaptivity into the classifier architecture can yield measurable improvements in both sensitivity (recall) and specificity (precision), critical in cybersecurity contexts where both false negatives and false positives are costly. Finally, it is worth noting that AVSVM achieves competitive results not through increased model complexity, as is common in deep neural networks, but through the intelligent reconfiguration of a classic and interpretable model. This makes AVSVM particularly suitable for applications that require a balance between performance, transparency, and computational efficiency—such as edge-based malware detection systems or real-time intrusion detection in constrained environments. Figure 9 compares the wall-clock training times (in seconds) required by four classifiers—standard SVM, PSO-SVM, CNN, and the proposed AVSVM—on the same malware detection dataset under identical hardware conditions. The standard SVM achieves the fastest training, completing in just two minutes (120 s) due to its direct quadratic optimization and absence of iterative metaheuristic loops. By contrast, PSO-SVM requires roughly five minutes (300 s) because it embeds the particle swarm optimizer’s global search around each SVM fit, introducing substantial overhead. Training the CNN baseline proves the most time-consuming, at ten minutes (600 s), owing to its deep architecture, backpropagation across multiple layers, and large batch operations on high-dimensional feature inputs. The AVSVM model, which incorporates biologically inspired pressure monitoring, eruption perturbations, lava flow adjustments, and a cooling schedule, takes four minutes (240 s). While this represents an increase over the standard SVM, it remains markedly more efficient than PSO-SVM and far faster than the CNN.

Figure 9.

Empirical Training Times of AVSVM and Baseline Models.

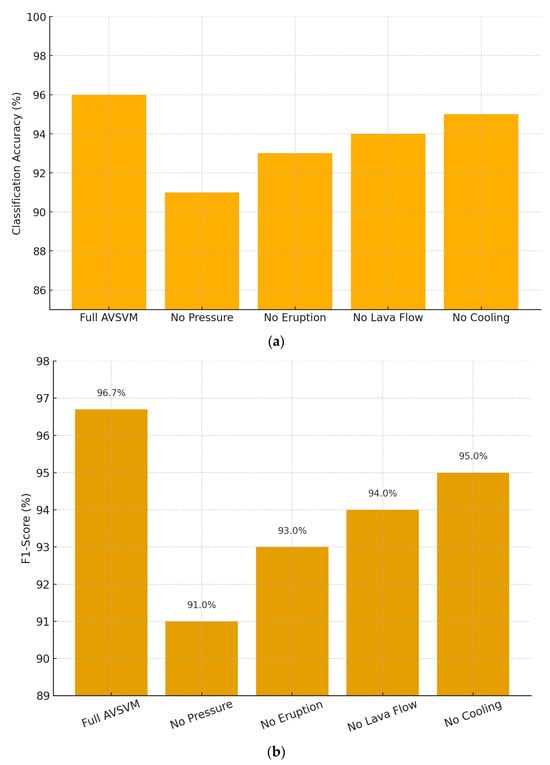

Removing the pressure function yields the largest performance drop, with accuracy falling from 96% down to 91%. This indicates that monitoring and acting upon the “pressure” of support vectors during training is critical to AVSVM’s ability to correctly classify malware samples. Without this component, the model loses much of its adaptive capacity, resulting in misclassification of boundary instances. Disabling the eruption operator reduces accuracy to 93%. The eruption step introduces strategic perturbations that help the classifier escape local minima in the decision boundary; without it, the algorithm still benefits from lava flow adjustments and cooling, but its exploration is less effective. Omitting the lava flow mechanism (accuracy: 94%) shows a smaller but still noticeable impact. Lava flow refines near-boundary samples by nudging them toward their class centers, sharpening the decision boundary. Its absence slightly degrades classification by leaving more ambiguous instances near the margin. Finally, skipping the cooling schedule yields a marginal drop to 95% as shown in Figure 10. The cooling schedule gradually reduces the intensity of eruption over iterations to prevent excessive perturbation later in training. While its effect is subtler than the other components, it still contributes to fine-tuning and stabilizing the final model.

Figure 10.

Ablation study of AVSVM components. (a) Classification accuracy of the full model compared to reduced versions with individual components removed (Pressure, Eruption, Lava Flow, Cooling). (b) Corresponding F1-scores under the same ablation conditions, illustrating the relative contribution of each mechanism to overall performance.

On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the removal of the pressure function reduced the F1-score by approximately 4.7%, while on the KDD dataset, the decline was slightly larger at 5.1%, reflecting the dataset’s greater class imbalance and feature overlap. Similarly, excluding the eruption operator resulted in a performance drop of ~3% on UNSW-NB15 and ~3.4% on KDD, confirming that eruption-driven perturbations are essential for escaping local minima across different environments. The lava flow and cooling schedule contributed smaller but still noticeable improvements on both datasets, underscoring their role in refining class separability and ensuring stable convergence.

The comparative analysis presented in Table 6 highlights the strengths and limitations of several state-of-the-art approaches in intrusion and malware detection. For example, the PSO-based ensemble method proposed by Afnan Birahim et al. (2025) [6] demonstrates that swarm intelligence can improve classification accuracy while maintaining a degree of interpretability. However, its ability to handle severe class imbalance and noisy data remains limited, making it less reliable in real-world scenarios. Similarly, the GA-HDLAD framework of Mutambik (2024) [7] combines genetic algorithms with deep learning to achieve adaptability in IoT-based intrusion detection. While effective, its architecture is computationally complex and largely static once deployed, restricting its responsiveness to evolving malware. Deep learning approaches such as the CNN-LSTM hybrid model by Kamal and Mashaly (2025) [8] deliver strong results in both binary and multi-class classification tasks by capturing spatial and temporal dependencies in attack traffic.

Table 6.

Comparison of AVSVM with State-of-the-Art Methods in Intrusion and Malware Detection.

Nevertheless, these models remain prone to overfitting and often lack mechanisms to dynamically adjust decision boundaries when confronted with new or overlapping malware patterns. The broad experimental studies conducted by Dini et al. (2023) [9] further emphasize this limitation by showing that even conventional ML-based IDSs face challenges of scalability, feature drift, and adversarial noise—issues that remain unresolved in many deep or ensemble models. Ensemble-based techniques have also been widely studied. The work of Nassreddine et al. (2025) [10] integrates correlation-based and embedded feature selection to improve robustness across multiple datasets, but its performance deteriorates when faced with dynamic and evolving threats. Likewise, Jaw and Wang (2021) [11] achieved improved generalization using a filter–wrapper feature selection strategy combined with boosting, yet their approach results in rigid decision boundaries that lack adaptive flexibility. The AOA-DL model by Alrowais et al. (2022) [12] combines arithmetic optimization with deep learning, successfully adapting to traffic variability, but its heavy computational cost limits real-time deployment and scalability. Other emerging directions include federated learning IDSs as introduced by Devine et al. (2025) [13], which distribute learning across edge devices to preserve privacy and scalability. However, these approaches often neglect adaptive decision boundary reshaping, leaving them vulnerable to concept drift and overlapping feature distributions. Sequence learning has also been explored through the LSTM-based intrusion detection for CAN bus networks by Hossain et al. (2020) [14], which is highly effective in vehicular environments but struggles to generalize to large-scale, high-dimensional malware datasets. Finally, the GA-CNN approach by Huang et al. (2023) [15] demonstrates strong performance in industrial IoT environments by optimizing deep CNN architectures with genetic algorithms. Despite its effectiveness, the reliance on deep architectures introduces significant computational overhead and a tendency toward overfitting when applied to diverse malware datasets. In contrast, the proposed Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM) addresses the recurring limitations identified across these studies by introducing biologically inspired mechanisms that enable dynamic margin adaptation. Unlike ensemble and deep models that depend on static optimization or heavy computation, AVSVM achieves robustness against class imbalance, noise, and evolving malware patterns while remaining computationally efficient. This positions AVSVM as a promising alternative to current state-of-the-art methods, bridging the gap between interpretability, adaptability, and performance in modern cybersecurity environments.

The strong results achieved by AVSVM stem not only from accurate classification but from its unique ability to adaptively adjust to margin instability, local class overlap, and noisy data regions. These advantages are rooted in its biologically inspired mechanisms, which go beyond algorithmic novelty and deliver practical gains in accuracy, robustness, and convergence reliability. Despite its promising accuracy gains, the AVSVM framework exhibits several important limitations. First, the reliance on multiple biologically inspired operators introduces additional hyperparameters—such as eruption thresholds, lava-flow rates, and cooling schedules—that must be carefully tuned for each dataset, potentially complicating practical deployment. Second, while the adaptive mechanisms enhance exploration and boundary refinement, they incur nontrivial computational overhead compared to a vanilla SVM, which may pose challenges in real-time or resource-constrained environments. Third, the current evaluation focuses solely on binary malware classification under static, offline conditions; AVSVM’s performance on multi-class detection tasks, streaming data with concept drift, or severely imbalanced feature spaces remains untested. Finally, the method’s robustness against adversarial manipulation has not been assessed, leaving open questions about its security in adversarial settings. Together, these limitations suggest that further research is needed to streamline parameter selection, optimize runtime efficiency, extend evaluation scenarios, and validate the model’s resilience under adversarial threats.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper introduced the Adaptive Volcano SVM (AVSVM), a novel biologically inspired classification algorithm designed to enhance support vector machine performance in complex and dynamic malware detection environments. Drawing inspiration from volcanic phenomena—specifically pressure buildup, eruption, lava flow, and cooling—AVSVM augments the conventional SVM framework with adaptive behaviors that allow it to escape local minima, reshape decision boundaries under instability, and converge reliably through a controlled learning process. Extensive simulations were conducted on two benchmark datasets, KDD Cup 1999 and UNSW-NB15, to evaluate the efficacy of AVSVM against standard classifiers including SVM, PSO-SVM, and CNN. The proposed model achieved 96.7% accuracy, 95.4% recall, 96.1% precision, 95.75% F1-score, and a 3.1% false positive rate on the UNSW-NB15 dataset—outperforming all baseline methods across all evaluation metrics. Similarly, AVSVM delivered competitive results on the KDD dataset, with consistent improvements in classification quality, especially in reducing false positives and improving generalization on unseen attacks. Beyond its numerical superiority, AVSVM demonstrated robust convergence behavior (Figure 8), stable boundary refinement, and statistically significant performance improvements (p < 0.05) compared to all baselines (Figure 6). The algorithm’s strength lies in its unique combination of pressure-sensitive margin adaptation, eruption-based perturbations, and localized lava flow corrections, all regulated through an exponential cooling schedule. These mechanisms enabled the classifier to operate effectively even in highly imbalanced, noisy, or overlapping feature spaces—conditions commonly encountered in real-world malware datasets. While AVSVM offers a compelling alternative to existing SVM-based and deep learning methods, there remain several promising avenues for future research. Extension to Multi-class and Multi-label Problems: The current implementation is optimized for binary classification (malware vs. benign). Future work will involve extending AVSVM to handle multi-class scenarios, such as distinguishing between multiple malware families or attack types. Integration with Feature Selection: Incorporating feature selection or dimensionality reduction techniques—possibly guided by the pressure function—could further improve computational efficiency and interpretability. Online and Incremental Learning: In dynamic environments like network intrusion detection systems (IDSs), data arrives continuously. Enhancing AVSVM to support online updates could make it suitable for real-time deployment. Hybridization with Deep Architectures: The AVSVM framework could serve as a post hoc refinement stage for deep neural network outputs, offering interpretability and stability on top of deep feature extraction. Adversarial Robustness Evaluation: Since malware often attempts to evade detection, evaluating AVSVM under adversarial conditions (e.g., evasion attacks, feature manipulation) would be a valuable contribution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.A.A.; Methodology, A.E.A.A.; Software, A.E.A.A.; Validation, A.E.A.A.; Formal analysis, A.E.A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.E.A.A.; Writing—review and editing, M.C.; Visualization, M.C.; Supervision, M.C.; Project administration, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhan, Z.-H.; Shi, L.; Tan, K.C.; Zhang, J. A survey on evolutionary computation for complex continuous optimization. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 59–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, H.; Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Mirjalili, S.; Soleimanian Gharehchopogh, F.; Oliva, D. A critical review of moth-flame optimization algorithm and its variants: Structural reviewing, performance evaluation, and statistical analysis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 2177–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, T.M.; El-Saleh, A.A.; Alswaitti, M.; Al-Tashi, Q.; Summakieh, M.A.; Mirjalili, S. Particle swarm optimization: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10031–10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Xing, X.; Zhang, J.; Qing, S.; Zhao, X. Optimization of Support Vector Machine with Biological Heuristic Algorithms for Estimation of Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Using Limited Meteorological Data in China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Elaziz, M.A.; Khasawneh, A.M.; Alshinwan, M.; Ibrahim, R.A.; Al-Qaness, M.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Sumari, P.; Gandomi, A.H. Meta-heuristic optimization algorithms for solving real-world mechanical engineering design problems: A comprehensive survey, applications, comparative analysis, and results. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 4081–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birahim, S.A.; Paul, A.; Rahman, F.; Islam, Y.; Roy, T.; Hasan, M.A. Intrusion Detection for Wireless Sensor Network Using Particle Swarm Optimization Based Explainable Ensemble Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 13711–13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I. Enhancing IoT Security Using GA-HDLAD: A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Anomaly Detection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Mashaly, M. Robust Intrusion Detection System Using an Improved Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Binary and Multi-Class Classification in IoT Networks. Technologies 2025, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, P.; Elhanashi, A.; Begni, A.; Saponara, S.; Zheng, Q.; Gasmi, K. Overview on Intrusion Detection Systems Design Exploiting Machine Learning for Networking Cybersecurity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassreddine, G.; Nassereddine, M.; Al-Khatib, O. Ensemble Learning for Network Intrusion Detection Based on Correlation and Embedded Feature Selection Techniques. Computers 2025, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaw, E.; Wang, X. Feature Selection and Ensemble-Based Intrusion Detection System: An Efficient and Comprehensive Approach. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrowais, F.; Marzouk, R.; Nour, M.K.; Mohsen, H.; Hilal, A.M.; Yaseen, I.; Alsaid, M.I.; Mohammed, G.P. Intelligent Intrusion Detection Using Arithmetic Optimization Enabled Density Based Clustering with Deep Learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, M.; Ardakani, S.P.; Al-Khafajiy, M.; James, Y. Federated Machine Learning to Enable Intrusion Detection Systems in IoT Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.D.; Inoue, H.; Ochiai, H.; Fall, D.; Kadobayashi, Y. Lstm-based intrusion detection system for in-vehicle can bus communications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 185489–185502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Zeng, G.Q.; Geng, G.G.; Weng, J.; Lu, K.D. Sopa-ga-cnn: Synchronous optimisation of parameters and architectures by genetic algorithms with convolutional neural network blocks for securing industrial internet-of-things. IET Cyber-Syst. Robot. 2023, 5, e12085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guezzaz; Benkirane, S.; Azrour, M.; Khurram, S. A reliable network intrusion detec- tion approach using decision tree with enhanced data quality. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 1230593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohy-eddine, M.; Guezzaz, A.; Benkirane, S.; Azrour, M. An effective intrusion detection approach based on ensemble learning for iiot edge computing. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2022, 19, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohy-eddine, M.; Guezzaz, A.; Benkirane, S.; Azrour, M. An efficient network intrusion detection model for iot security using k-nn classifier and feature selection. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 23615–23633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Zeng, G.Q.; Geng, G.G.; Weng, J.; Lu, K.D.; Zhang, Y. Differential evolution- based convolutional neural networks: An automatic architecture design method for intrusion detection in industrial control systems. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharsan, A.; Ata, O. HawkFish Optimization Algorithm: A Gender-Bending Approach for Solving Complex Optimization Problems. Electronics 2025, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douiba, M.; Benkirane, S.; Guezzaz, A.; Azrour, M. An improved anomaly detection model for iot security using decision tree and gradient boosting. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 3392–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazman, C.; Guezzaz, A.; Benkirane, S.; Azrour, M. Lids-sioel: Intrusion detection frame- work for iot-based smart environments security using ensemble learning. Clust. Comput. 2022, 26, 4069–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh-Quang, T.; Elsisi, M.; Mahmoud, K.; Liu, M.K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M.M.F. Experimental setup for online fault diagnosis of induction machines via promising iot and machine learning: Towards industry 4.0 empowerment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 115429–115441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid; Breslin, J.G.; Intizar, M.A. Prediction of machine failure in industry 4.0: A hybrid ocnn-lstm framework. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marianna, L.; Lazoi, M.; Corallo, A. Cybersecurity for industry 4.0 in the current literature: A reference framework. Comput. Ind. 2018, 103, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).