Featured Application

This article provides an overview of information on fire emissions from various facilities and locations, which are a key safety tool for both people and the environment. Depending on the type of substance and the location of the fire, various compounds are emitted into the air, including nanoparticles of metals and organic compounds. Information in this area is essential for taking appropriate action, including developing anti-pollution solutions. Implemented modifications, including those based on nanotechnology, also alter the toxic clouds generated during fires. Therefore, knowledge in this area must be constantly updated.

Abstract

Fires are among the few processes that significantly impact the state and quality of the environment. Depending on the type and quantity of materials, products, or waste accumulated at a given location, various substances can be released into the environment during a fire. Knowledge of the potential hazards resulting from emission levels allows for appropriate action to be taken and protective measures to be implemented for those present at the scene. Therefore, this article analyzes the composition of emissions depending on the type of material involved in the fire, with particular emphasis on forest fires, substance dumps, and waste disposal sites. An analysis of the available literature revealed the presence of countless toxic organic and inorganic substances, including ultrafine particles and nanoparticles of metals, nonmetals and their compounds, and compounds with long-term toxic and mutagenic effects, such as benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), formaldehyde, and 1,3-butadiene. The development of new materials influences the composition of gases and fumes released during fires; therefore, continuous quantitative and qualitative analysis, the development of appropriate analytical tools, and legal requirements are essential.

1. Introduction

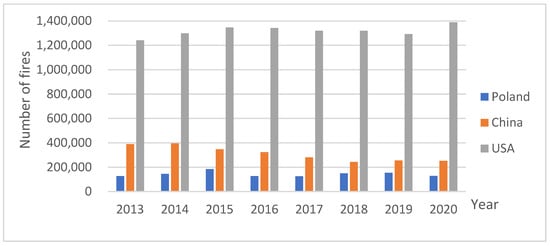

Fires are often uncontrolled events whose effects include direct costs from loss of property and human lives. They significantly impact the surrounding environment by polluting the air, soil, and surface waters and, indirectly, groundwater [1]. In a functioning ecosystem, two types of fires occur: natural fires, which are caused by natural factors independent of human activity, and anthropogenic fires, which are caused by human activity. The occurrence of both types undeniably influences biological evolution and global biogeochemical cycles, therefore making fire an integral part of some biomes [2]. The number of fires is determined by a country’s area, land use, and human responsibility. Thus, comparing statistical data on the total number of fires between 2013 and 2020 in Poland, China, and the United States, it should be noted that the most fires occurred in the USA, and the fewest in Poland (Figure 1). In China’s case, the data show a decreasing trend, while for the United States, the trend is increasing.

Figure 1.

Total number of fires in Poland, China and the USA in 2013–2020 [3,4,5].

The structure of the combustible material, oxygen availability, temperature, and the location of the fire primarily determine the composition of combustion products. It should be noted that the physical state and composition of the burning substance have a greater impact on fire development than the chemical composition of the fuel itself. This principle is very important when assessing the qualitative and quantitative composition of substances emitted during a fire [6,7]. At the moment of ignition, as a fire begins to develop, the combustion processes of organic matter occur with high efficiency. In a well-oxygenated environment, this leads to the formation of practically exclusively carbon dioxide and water. An increase in temperature also causes the appearance of nitrogen monoxide and nitrogen dioxide in the fire gas mixture. As the fire develops, a situation may arise where the oxygen supply to the combustible substance becomes limited, leading to incomplete combustion. Most fires that occur in confined spaces, such as building fires, are characterized by such incomplete combustion. As oxygen access to the burning material becomes restricted, the concentration of other compounds in the resulting gases increases, including particulate matter, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and other organic and inorganic compounds. At the same time, high temperature can cause chemical changes in the combustible material due to the pyrolysis process occurring on the surface of the combustible material, with or without the presence of oxygen. However, it should be noted that slow oxidation does not lead to the formation of a flame, but it does produce more various toxic compounds than combustion in a flame [6,8].

Previous studies have shown that approximately 130 chemical substances, both organic and inorganic, are present in a fire environment [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Among the released compounds, the presence of various substances has been confirmed, including saturated and unsaturated aliphatic hydrocarbons, saturated and unsaturated aromatic hydrocarbons, benzene, toluene, xylenes, ethylbenzene, as well as metals, nitrogen oxides, carbon oxides, sulphur oxides, and dust. In many cases, hydrocarbon mixtures formed the main component of the aerosol creating smoke, which makes it a flammable system. The composition of substances emitted during fires also identified trimethylbenzene isomers, dimethylbenzene, and dichloroethane. Aldehydes, including formaldehyde, and nitrogen oxides were present in all air samples. Additionally, sulphates were found in dozens of samples [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

The released substances often possess toxic properties and, frequently, also carcinogenic and mutagenic ones. During the combustion process plastic materials alone generate substances classified by the IARC as “probable” and “possibly carcinogenic” [24,25,26,27,28]. Thus, the environment created during a fire constitutes a mixture of substances, including those classified in the first group of the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) carcinogens [29], which significantly impacts the threat to the life and health of individuals involved in the incident [30,31,32].

Due to technological advancements, nanoparticles are increasingly being identified in fire environments, and their properties can significantly determine the processes occurring within that environment. As numerous studies have shown, nanosubstances introduced into the body can, in some cases, be potentially carcinogenic and elicit a more pronounced pro-inflammatory response than larger particles of the same material [33,34]. However, there are few studies that unequivocally indicate the quantitative and qualitative emission parameters of nanosubstances during fires. Therefore, it is essential to continuously update information in this area.

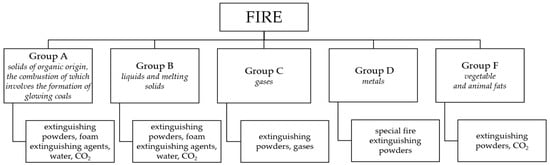

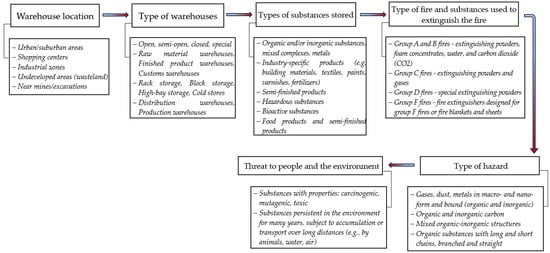

The diversity of fires necessitates the use of not only appropriate equipment but, above all, adequate extinguishing agents in rescue and firefighting operations. For example, for extinguishing Group A fires (solid materials of organic origin that burn with the formation of embers [35]), as well as Group B fires (fires involving liquids and melting solid materials), fire extinguishing powders, foam concentrates, water, and carbon dioxide (CO2) are used (Figure 2). For extinguishing Group C fires (gas fires), fire extinguishing powders and gases are utilized, while for metal fires (Group D), special fire extinguishing powders are employed [35,36,37]. Fires involving vegetable and animal fats (Group F fires) hold a particular position [38], and these are usually extinguished using fire extinguishers designed for Group F fires or fire blankets and sheets.

Figure 2.

Classification of fires and means used to extinguish them ([37,38,39]).

The type of agent matters for analysing the transformations and processes occurring both during a fire and its extinguishing and the overhaul phases. For instance, the use of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC)-based extinguishing agents leads to the formation of hydrogen fluoride gas [HF(g)] during the thermal decomposition of the agent [40]. However, the scale and potential for fire spread mean that the mechanisms of extinguishing agents are diverse. They include those based on heat removal from the burning material’s surface, cooling, oxygen deprivation, and the inhibition of radical reactions occurring in the flame [41]. All these elements make fire environments a very complex system.

It should also be emphasised that the continuous development of the economy, industry, and new technologies, such as electric vehicles, photovoltaics, and nanotechnology, compel fire protection to develop and implement new fire extinguishing solutions, adequate to the changing threats. Therefore, current knowledge regarding the qualitative and quantitative emissions from a given source is essential. The aim of this review is to present information on the emissions of various substances, including nanostructures, resulting from fires in natural ecosystems, buildings, warehouses, and landfills. Therefore, a literature review was conducted using the following databases: Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Google (gray literature), as a source of knowledge about global social and economic life. The search period was not limited. The databases were searched in four groups, taking into account the different elements under analysis. The following keywords were used in each group (in various combinations, using AND/OR operators):

- -

- forest, fire, emission, organic substances, inorganic substances, gases, dust, toxic substances, nanoparticles,

- -

- buildings, houses, shops, fire, emission, organic substances, inorganic substances, gases, dust, toxic substances, nanoparticles,

- -

- warehouses, fire, emission, organic substances, inorganic substances, gases, dust, toxic substances, nanoparticles,

- -

- landfills, fire, emission, organic substances, inorganic substances, gases, dust, toxic substances, nanoparticles.

The search results were checked for substantive relevance. Duplicates and publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria (lack of quantitative and qualitative data, lack of description of emissions, or lack of connection to a fire in a given facility/area) were excluded. The following inclusion criteria were used:

- −

- Publications containing quantitative data on at least one of numerous pollutant groups (including HCl, HF, PAHs, PM, heavy metals, nanoparticles).

- −

- Articles describing the emission process conditions (substance group, environmental conditions, area characteristics, extinguishing agents used).

- −

- Studies assessing the impact of factors on emissions (environmental conditions, type of material, land use, meteorological conditions).

- −

- Publications and reports from recognized research centers and territorial units, local government units, and firefighting organizations.

Studies reporting concentrations of individual metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cr, As) and studies providing aggregated indicators of “heavy metals” were included. A similar approach was taken for organic compounds, i.e., groups of compounds such as PAHs, NMHCs, and PBDDs were included, as well as individual organic compounds (e.g., benzene, naphthalene, benzo(a)pyrene).

The following exclusion criteria were used in the analysis:

- −

- Publications not containing data on emitted compounds (commentaries, journalistic articles),

- −

- Studies not describing the measurement methodology used,

- −

- Reports not concerning pollutant emissions (e.g., descriptions of fires).

The collected numerical data were subjected to comparative analysis, which included standardization of units (mg/kg), categorization of results by pollutant type (including HCl, HF, PAHs, PM, heavy metals, nanoparticles), quantitative and qualitative comparison of emissions, and comparison of the impact of factors such as temperature, management, plant species (etc.) on pollutant emissions from fires. The information was discussed in a discussion, relating it to the legal requirements of six countries (Poland, Germany, Japan, Australia, France, and the USA). The data were not statistically averaged across studies. Due to the numerous factors that differentiate the data, descriptive characterization was used.

The information obtained will help determine directions for emission monitoring, analytical methods and techniques, and fire propagation, including those involving new substances that are increasingly used in various areas of human life. It will also provide guidance for improving IT tools, as the information obtained and the identified significant gaps will allow for increased awareness and refinement of fire and contaminant migration models.

2. Natural Ecosystem Fires

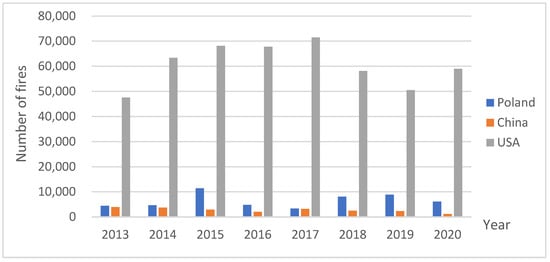

Globally, depending on the region, the frequency of forest fires shows an increasing trend, bringing negative consequences for both the environment and people. Between 2001 and 2010 alone, the globally burned area increased by 35% or 120 Mha/year, with the largest changes recorded in Asia (157% increase), Central America (143%), and Europe (112%) [42]. In the Mediterranean basin alone, the average annual number of forest fires is approximately 50,000, which is about twice as high as in the 1970s. However, an accurate assessment is difficult due to varying methodologies for recording fires in different countries. Some sources indicate an approximately threefold increase in the number of fires in Spain (from 1900 to 8000) and in Italy (from 3400 to as many as 10,500) since the late 1950s. In contrast, for Greece and Turkey, the increase was the smallest, from 700 to 1100 and from 600 to 1400, respectively. In Portugal, a record area of forest and cultivated land burned in 2017 [43]. Despite the comparable area of countries like the United States and China, the most fires are recorded annually in the United States (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Total number of forest fires in Poland, China and the USA in 2013–2020 [44,45,46].

According to information published by the European Commission, in the European Union, the 2022 fire season was the second worst in the EU since 2000, when the Copernicus European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) began. Fires also affected ecologically valuable, protected areas such as Natura 2000 sites. The total burned area within these protected zones in 2022 reached 365,308 hectares—the highest value in the last ten years. Damages were particularly concentrated in three countries: Spain, Romania, and Portugal. Together, they accounted for over 75% of the total area burned in the protected areas [47].

Fires in protected areas are associated with biomass combustion and occur in all vegetated terrestrial ecosystems. Most fires are ignited by humans in tropical and subtropical forests. Another source of ignition is lightning strikes in remote boreal regions [48]. According to 2006 data from the Global Fire Partnership (GFP), 25% of land area remains undisturbed relative to fire regime conditions. Ecoregions with degraded fire regimes cover 53% of the world’s land area. Those with highly degraded fire regimes cover 8%. Globally, boreal forests are the most undisturbed ecosystems concerning fire regime conditions [49]. Peatland fires are exceptionally difficult to extinguish due to the soft, marshy ground, which prevents wheeled firefighting equipment from accessing the area. In consequence aerial suppression is the only option, further hindered by rising plumes of smoke. Moreover, peat, similar to lignite or hard coal, is a fossil fuel. When a peatland fire occurs, the underground fire can persist for a very long time—several months, or even years. This is because peat often lies several meters deep beneath the surface, allowing the fire to smoulder underground, subside, and then reignite. An additional problem is that most fens in Europe have been drained, increasing the risk of peat ignition [43].

Fires in natural ecosystems determine air quality. However, this depends on many factors, including meteorology and the dynamics of the fire plume. It is also dependent on the quantity and chemical composition of emitted substances, as well as the atmosphere into which they are dispersed. The main factor is also the fuel characteristics combined with meteorology and topography, which control fire behaviour.

The primary components of emissions from forest fires include organic compounds in both gaseous and particulate phases. Nevertheless, the main products of biomass combustion are CO2 and water vapour. However, a large number of particulate matter (including what is known as Black Carbon, BC) and trace gases are produced. They include products of incomplete combustion (CO, NMVOCs) and various nitrogen and sulphur compounds, which arise partly from the nitrogen and sulphur contained in vegetation and organic matter in surface soils [50].

An analysis of substances emitted solely by forest fires has shown that the main components are particulate matter (PM), CO2 (90–95%), CO, nitrogen compounds (NOx, N2O), sulphur compounds (XS), hydrocarbons (THC), including methane (CH4) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [51]. Saha et al. [52] demonstrated that during a dry deciduous forest fire on the Chota Nagpur plateau (India) in the Ayodhya Mountain range in March 2021 alone, the emission of carbon and nitrogen in the form of selected compounds was 294.15 g CO2, 1.44 g CH4, 21.03 g CO, 0.0099 g NO2, and 0.0231 g NOx [53]. Some of the directly emitted compounds, such as H2, COS, and to a lesser extent CH3Cl [50], pose a significant threat to air quality, while others can react with oxidants to form secondary pollutants, including ozone and secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Furthermore, compounds emitted in the particulate phase can volatilize during smoke transport and may then serve as SOA precursors [54]. Kjällstrand et al. [55], on the other hand, demonstrated through laboratory studies that significant amounts of methoxyphenols were released as a result of the combustion of forest material.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released during the burning of natural ecosystems include a group of non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs). They are photochemically active and are a major photochemical precursor to smoke. NMHCs consist of alkanes, olefins, aromatic hydrocarbons, and other organic compounds that are unstable, flammable, and explosive. Thereby, they increase the hazards associated with extinguishing forest fires [56].

Fire development and the types of emissions also depend on the moisture content of the litter. This factor influences fire initiation and spread, though there is limited data on its effect on pollutant emissions. Ma et al. [51] conducted research to quantitatively estimate the composition of pollutants emitted by forest fires at varying litter fuel moisture content, encompassing both branches and leaves. Low moisture content caused concentrations of compounds like CO, CO2, NOx, and SO2 to reach their peak values more quickly. As the litter fuel moisture content increased, CO emission factors rose, while CO2, NOx, and SO2 emission factors decreased. The material composing the litter also plays a crucial role. For material sourced from coniferous trees, the emission factors for CO, CO2, NOx, and SO2 released during combustion significantly increased with fuel moisture content compared to burning deciduous tree material. In the case of NMHC compounds, it was found that an increase in fuel moisture content also led to higher emissions of multi-branched and long-chain alkanes. On the other hand, there was a decrease in the emission of olefins and aromatic hydrocarbons. However, it was observed that for olefins and aromatic hydrocarbons with more branched chains, emission levels increased under the same environmental conditions [51].

It should be noted that estimating CH4 concentration levels is becoming increasingly important in emission monitoring. CH4 sources are associated with biogenic, thermogenic, or pyrogenic processes, with fires being the largest source of pyrogenic CH4 emissions. Fires generate CH4 emissions through the incomplete combustion of biomass and organic soil carbon under hot, dry weather conditions and high fuel loads. It is estimated that fires account for approximately 4% of global total CH4 emissions annually [57,58]. Methane released during a fire is isotopically heavier than that of biogenic origin. This is because methane from burning vegetation (e.g., trees, tropical grasses, corn, sugarcane) is typically enriched in the 13C isotope compared to biogenic emissions from wetlands, ruminants, or waste [59,60,61]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the composition of emitted mixtures in forest and savanna areas is similar and very complex (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of emitted compounds depending on the biomass covered by the fire ([37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]). X—occurrence.

Results from various research centers indicate that the emission level of individual compounds depends on the type of plants involved in the fire. Guo et al. [62] demonstrated the importance of tree species and fuel type for qualitative and quantitative parameters of emissions during fire. Emission factors (EF) were quantified for gaseous pollutants such as CO, CO2, NOx, hydrocarbons, organic carbon, and inorganic elements, as well as fine suspended particulate matter such as PM2.5, non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHC), and water-soluble inorganic ions. The analysis included leaves, branches, and bark from five dominant tree species in the Chinese boreal region: two conifer species (Larix gmelinii and Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica) and three broadleaved species (Betula platyphylla, Quercus mongolica, and Populus tomentosa). The results show that emission factors for various pollutants varied depending on the tree species and fuel type. A total of 48 NMHC species (19 alkanes, 15 alkenes, and 14 aromatics) were identified during the combustion of leaves, bark, and branches, with pollutant emissions ranging from 982 mg/g to 1375 mg/g. However, burning bark from selected tree species resulted in higher emissions compared to burning leaves and branches, which may indicate that emissions during the cold season, when trees are defoliated, will be characterized by different parameters than during the summer months, when trees are leafy. Comparing the total emissions from burning coniferous and broadleaf trees, it was also found that broadleaf species emitted more CO2, NOx and hydrocarbons than coniferous species, while coniferous species emitted more CO, OC, EC and PM2.5 [62].

In case of fires involving less diverse biomass, the resulting pollutants may be less complex. However, in all cases, alongside organic compounds, nanoparticles are formed, including carbon nanoparticles, whose toxicity is very high.

The wide range of substances emitted during forest fires contributes to air pollution by increasing toxin levels even at great distances from the fire’s origin. Air quality can deteriorate due to the transport and transformation of fire-related emissions on local, regional, and continental scales [63]. However, the scale and scope of the impact on the environment and humans depend on meteorological conditions, land use, vegetation affected by the fire, and the properties of the emitted substances.

3. Building Fires

Modern building constructions are made from many different materials. Their chemical composition influences the course of a fire and the profile of the released pollutants. These pollutants primarily, though not exclusively, originate from combustible carbon-containing materials such as wood-based composites made from cellulose fibres and sawdust, plastics like polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride. These come in the form of panels and composite boards (chipboard, flax board, and fibreboard) consisting of thin wooden layers glued with formaldehyde-urea and polyurethane resins. They are increasingly used due to their moisture resistance. Building construction also increasingly utilizes products made exclusively from plastics, such as window frames and floor panels made from polyvinyl chloride, as well as attic insulation made from PUR foams, facade insulation from polystyrene boards, etc. All these materials may also contain various additives in their composition, such as fillers, plasticizers, and flame retardants. These can also be released or undergo chemical transformations during a fire.

Similarly, some inorganic materials used in construction can influence the profile of substances released during a fire. These include structural metals with low melting points, such as zinc (melting point 419.53 °C), aluminium (melting point 660.32 °C), copper (melting point 1084.62 °C), mineral wool facade insulation, and asbestos cement roof tiles, which are being phased out.

In addition to carbon and nitrogen oxides and incomplete combustion products like formaldehyde, acrolein, and PAH hydrocarbons, which are always present in fire gases, hydrogen chloride, polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PCDD), and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDF) may also be present (depending on the construction materials used). During fires involving PVC panels and window frames, hydrogen cyanide and diisocyanate are released [64]. They are used as initiators for the polymerization of resins and polyurethane foams, such as methylenediphenyl diisocyanate (MDI) and toluidinyl diisocyanate (TDI).

One of the elements of every building is its electrical infrastructure, especially the materials used for insulation. Research conducted by Zhu et al. [65] and McNeill et al. [66] revealed that during cable fires, large quantities of hydrogen chloride (HCl) and aromatic and alkylaromatic compounds are released. Fillers used in these materials (such as CaCO3, CaO, and Ca(OH)2) acted as factors limiting HCl release by binding chloride radicals. During the pyrolysis of dioctyl phthalate (DOP), which occurs during a fire, products such as benzene, toluene, benzaldehyde, phthalic anhydride, isooctenes, unsaturated ketones, and alcohols are formed. In addition to the pyrolysis products of PVC (Polyvinyl chloride) and DOP, the pyrolysis of a PVC-DOP mixture leads to the formation of products from a series of radical reactions [65,66]. Chong et al. [67] investigated the composition of substances emitted during the combustion of PVC pipes, which are an equally crucial element of building equipment, not only in residential but also in industrial and service sectors. The research results showed the presence of chlorinated components, including chlorine dioxide, methylene chloride, allyl chloride, vinyl chloride, ethyl chloride, 1-chlorobutane, tetrachloroethylene, chlorobenzene, HCl, benzene, 1,3-butadiene, methyl methacrylate, CO, acrolein, formaldehyde, and many other long-chain HCs [68].

However, it was observed that requirements on fire safety have necessitated modifications to materials to reduce flammability. Both organic and inorganic fillers are used. Therefore, the combustion reactions of polymeric materials result in the release of various additives used in polymer production, such as fillers (carbon black, metal oxides), plasticizers (phthalic acid esters), and flame retardants (polybrominated biphenyls [PCBFs] or phosphoric acid esters and aliphatic or aromatic alcohols like tris(chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP), tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate (TEHP), and tricresyl phosphate (TCP)). A broad group of compounds used in construction are polymeric nanocomposite materials, such as organosilicon polymers (silicones), primarily branched polymers like silicone resins, and linear polymers like silicone rubbers [68]. The thermal decomposition processes of polysiloxanes, especially those occurring at low temperatures, can be determined by contaminants that catalyse degradation, such as acidic or basic contaminants, oxygen, or water. Furthermore, degradation can occur due to changes in interactions between the polymer and reinforcing fillers, including, for example, silica, graphene, CeO2, Al2O3, TiO2 nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes [69].

Inorganic materials used in building constructions, such as frames and other aluminium structural elements, can also be sources of pollution. At temperatures typically exceeding 1000 °C reached during a building fire, structural elements made from materials like copper and aluminium alloys can melt and penetrate the ground. Zinc, with a boiling point of 907 °C, can vaporize under these conditions. In suitable conditions, such vapours can be rapidly dispersed into the atmosphere. This leads to their cooling and the formation of ZnO particles with a diameter corresponding to the respirable or nanoparticle fraction [70].

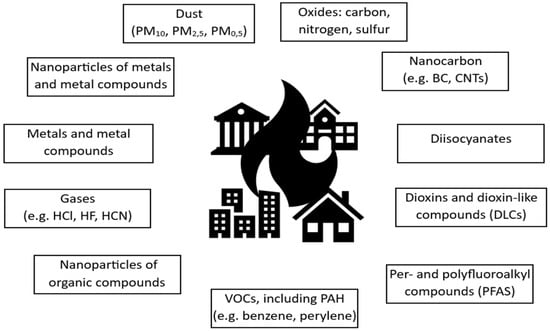

It should be emphasised that fires in residential buildings or shops, which are places with the greatest diversity of both organic and inorganic materials, at both macro and nano scales, pose a serious threat to both the environment and individuals involved in the incident (Figure 4). The analysis of nanoparticles formed during fires primarily focuses on identifying nanoparticles of metals and metal compounds. To a lesser extent, quantitative analysis is performed on nanoparticles of organic compounds (NOC). Sgro et al. [71] found that NOCs with diameters of d = 1–3 nm, formed during the combustion process, significantly shape the physicochemical properties of the organic fraction of PM.

Figure 4.

Examples of compounds emitted during residential building fires.

One group of products used in residential buildings that is a source of diverse pollutants is furniture upholstery. Depending on the measures used, fires can release inorganic acids such as HCN, HCl, H3PO4, and CO; nitrogen compounds such as NO, NO2, and NH3; and organic compounds such as PAHs, VOCs, SVOCs, TCPP, TCEP, PCDDs, PCDFs, isocyanates, and PM. The situation is similar for carpets. Vinyl carpets exposed to fire will generate compounds such as HCl, CO, PCDDs, and PCDFs, while polyamide carpets will generate a different group of compounds, including NO, NO2, NH3, HCN, CO, PAHs, VOCs, SVOCs, isocyanates, and PM [72]. The quantity and type of furniture, carpets, household appliances, and other products will determine the varying qualitative and quantitative emissions, which means that each fire must be approached individually, with appropriate knowledge and awareness.

The circulation of these pollutants in nature is determined by their state of matter under normal conditions and their susceptibility to oxidation by atmospheric oxygen. Gases such as carbon, sulphur, and nitrogen oxides, hydrogen chloride, hydrogen cyanide, and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) disperse most rapidly in the atmosphere. Some of these compounds, like nitrogen and sulphur oxides, react with water vapour in the atmosphere and then fall to the surface as acid rain. VOCs undergo photochemical reactions in the atmosphere, ultimately leading to their oxidation into carbon dioxide and water. Heavier pollutants, which do not exist as gases or vapours under normal conditions, form aerosols during a fire. Depending on the density of the substances forming the aerosol, these systems can be transported over shorter or longer distances. This applies to soot particles, metal oxides, aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, and dibenzofurans. These compounds ultimately settle on the ground, becoming soil pollutants.

Most of these pollutants, however, are deposited in the burn area, from which they can also be leached into the soil by water. The degree to which individual compounds are leached into the soil is primarily influenced by the pH of water. Among them are additives, such as anions that form soluble salts with leached metals, or detergents that increase the water solubility of hydrophobic organic compounds like PAHs.

Wooden materials, which form parts of the structure and furnishings like furniture, ceilings, floors, stairs, or heating material stored in homes for fireplaces and stoves, are also important. Arinaitwe et al. [73] showed that, on one hand, flame-retardant wood produces significantly less soot than non-flame-retardant wood. Nonetheless, flame-retardant wood generates more toxic gases, such as HCl, than wood without flame retardants and aged flame-retardant wood.

4. Warehouse Fires

Warehouse fires are characterized by a variable profile of emitted pollutants, which stems from differences in the combustion process of various materials. For this reason, the composition of post-fire gases and smoke will contain, in addition to ever-present substances such as carbon and nitrogen oxides and formaldehyde, substances specific to the burning material [74]. Fires in warehouses containing textile materials made from natural fibres have a pollutant profile similar to that measured in natural ecosystems. Whereas fires involving fabrics made from synthetic fibres can result in emissions caused by the release of toxic additives and enhancers. This group of compounds includes, among others, heavy metals used in the production of polyester fibres, halogenated hydrocarbons and phenols used as dye carriers, plasticizers for synthetic fibres (e.g., phthalic and phosphoric acid esters), additives improving hydrophobicity (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS), and compounds facilitating transport and preventing the aging of clothing (biocides, mainly halogenated phenols) [74].

However, fires in grain elevators can result in the emission of pesticides, dioxins, and large quantities of particulate matter. In places where furniture or construction materials containing polyurethane foam (PUR) are stored, emissions will be characterized by a high proportion of nitrogen oxides, isocyanates, and hydrogen cyanide. Building materials based on halogenated polymers like PVC lead to the release of corresponding hydrogen halides [75]. These types of fires are most often extinguished with water, or in the case of flammable liquid warehouses, with appropriate firefighting foam. Special guidelines in this regard apply to facilities that meet the Installation Classified for Environmental Protection (ICPE) criteria, for which recommendations were developed after the fire in the Lubrizol factory warehouse in September 2019 [76]. Fires involving pesticides, which typically contain heteroatoms such as chlorine, nitrogen, or phosphorus, are characterized by combustion with the release of hydrogen chloride, molecular chlorine, and reactive forms of nitrogen such as nitrogen dioxide and nitric acid(V).

Fires at chemical warehouses involve the release of the chemicals stored within them. For example, a case study of a warehouse fire and explosion in Italy resulted in an explosion and the release of its contents into the environment [77]. The warehouse had accumulated chemicals including potassium nitrate(V), magnesium chlorate(V), potassium hydroxide, sodium 1-hydroxyethylene-1,1-diphosphonate, potassium dichromate, powdered nickel, copper sulphate, copper chloride, N,N-diethylhydroxylamine, sodium phosphate, polyethylene glycol, and hydroxylamine sulphate.

In this type of fire, chemical hazards arise not only from the nature of the stored substances but also from the interaction of substance X with substance Y and with atmospheric oxygen. Reactions between strong acids and metals, which result in the release of hydrogen or the hydrolysis of carbides, as well as exothermic acid-base reactions, are particularly dangerous. Explosions can result from exoenergic thermolysis reactions, for example, hydroxylamine sulphate producing sulphur(VI) oxide, nitrogen(I) oxide, ammonia, and water vapour [78], or the thermolysis of potassium chlorate(V) yielding potassium chloride and oxygen [79,80]. Reactions that release oxygen provide an additional amount of oxidizer and increase the combustion temperature of adjacent flammable materials. These substances are released into the environment as a result of firefighting efforts. Inorganic salts enter the soil as dispersed dust, and a solution is formed with extinguishing water. Organic substances, such as polyethylene glycol and lignite, are combusted into carbon dioxide and water. The presence of heavy metals or their compounds with catalytic properties, such as iron ions or titanium oxide nanoparticles, can also influence the thermolysis process, accelerating it rapidly [50,51,54,55,81]. For this reason, it is not recommended to store large quantities of flammable materials in the immediate vicinity of substances that may act as oxidizers.

Fires in textile warehouses are characterized by the production of typical fire gases, i.e., carbon oxides, formaldehyde, and acrolein [82]. Additionally, when fibres containing heteroatoms such as nitrogen (e.g., Nylon) or chlorine (PVC) are stored, specific pollutants related to these heteroatoms may be released. In case of nitrogen compounds, it is ammonia as well as hydrogen cyanide, in case of chlorine—hydrogen chloride and dioxins. Most of the produced compounds are emitted into the atmosphere as fire dust and gases. Whereas soot containing PAHs and dioxins primarily pollutes the ground in the immediate vicinity of the burned-out warehouse. A specific type of storage facility is battery energy storage systems, which house a large number of lithium-ion batteries in a confined space [83]. NMC (Nickel, Manganese, Cobalt) type batteries consist of a cathode made of lithium-nickel-cobalt-magnesium oxide, a lithium or graphene anode, and an electrolyte which is lithium hexafluorophosphate dissolved in a carbonic acid ester. Battery casings can be made from steel, aluminium, or plastics. In the event of a fire in such a storage facility, these metals are released into the environment as smoke and ash, while the electrolyte solvent and plastic components combust into carbon oxides and water vapour. The lithium hexafluorophosphate used as an electrolyte undergoes hydrolysis with water vapour and extinguishing water, releasing hydrogen fluoride into the atmosphere and phosphoric acid, which is deposited in post-fire ash in the form of phosphates [84]. Larger quantities of this compound can also be released as a result of the thermolysis of halogenated hydrocarbons. They are frequently used to protect electrical installations from fire, aiming to limit damage and hazards associated with extinguishing live electrical systems with water. During the thermolysis of these agents, carbonyl fluoride is also released. As a phosgene analogue, it is also a highly toxic compound [85]. These reactions occur when halogenated hydrocarbons are heated to temperatures above 500 °C. The results of the conducted research also indicate that the extension of fire duration results in the release of larger amounts of heavy metals and semi-volatile organic compounds, including PAHs, into the air [86].

In the residues left after firefighting operations, large quantities of soot, phosphoric acid, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are always observed. Additionally, the use of firefighting foam (specifically, Aqueous Film Forming Foam—AFFF) can further introduce PFAS compounds into the environment. As a result of using a foam-forming extinguishing agent, solvents such as 2-(2-butoxyethoxy)ethanol and detergents like sulfonated alcohol derivatives from C3 to C16 may also be released into the environment. However, these substances, unlike PFAS compounds, are readily biodegradable [84].

Given that new materials are increasingly based on nanotechnology, the mixture emitted during warehouse fires also includes nanoparticles of metals, metal compounds, and organic compounds. An example is the production of construction materials, where nanoparticles are used as photocatalysts, substances that support the self-cleaning process, and flame retardants. Therefore, among the nanoparticles, TiO2 structures can be found. They are often modified with nitrogen, sulphur, boron, carbon, or combinations of these nonmetals. In addition to TiO2, other metals are also emitted, including Au, Cr, Fe, Mn, Mo, Nb, V, Pd, Ru, Ag, Pt, and their compounds, such as CdS.

The analysis of the impact of a warehouse fire on the environment and the associated risks should therefore cover many aspects, including the location of the warehouse, the composition of the stored materials and the fire extinguishing measures used (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Example of a warehouse fire hazard analysis.

5. Landfill Fires

Waste is generated by every type of human activity. Forecasts indicate that global waste production could reach 7 billion tons annually by 2050 [87], with only a portion of it being recycled. At the same time, approximately 41% of waste produced worldwide is being openly burned [88]. Various types of waste are accumulated both in designated and properly prepared facilities, as well as in so-called illegal dumps. The immense heterogeneity of waste can determine the likelihood and progression of a fire. It should be noted that no two fire emissions are the same when analyzing different landfills. Emissions are determined by numerous factors, including the location, amount, and type of materials, products, and nano-waste accumulated at a given site, their degree of decomposition and degradation, the location of the waste (e.g., near the surface, at the bottom of the landfill), and many other factors (Figure 6). Therefore, comparing the levels of emitted substances without precise knowledge of the quantitative and qualitative composition of the items accumulated at the fire site is unjustified.

Figure 6.

Examples of factors determining emissions from waste storage sites during fires.

Landfill fires encompass a large group of incidents at facilities used for waste storage and processing. Between 2017 and 2022, in Poland alone, there were 754 such fires at both legal and illegal waste disposal sites [89]. It is predicted that due to global climate change, the occurrence of these types of events may become more frequent [90]. However, not only climate change but also intentional human actions must be considered. The ignition of waste materials can occur as a result of poor operation and maintenance, deliberate burning, or the disposal of undetected smouldering materials. Risk can also arise from heat generated by biological and chemical reactions on and below the landfill surface [91].

In contrast to surface fires, which can be monitored and extinguished relatively easily upon early detection, underground or subsurface fires are quite difficult to mitigate. It is due to the fact that they remain unnoticed when smouldering in their early stages. These fires arise from the spontaneous combustion of waste materials under conditions conducive to increased aerobic decomposition activity. This leads to a significant temperature increase within the landfill [91,92]. Furthermore, the presence of methane “pockets” in the landfill, where this gas is trapped, can fuel fires and intensify their spread within the site [87]. Such fires can persist for many days or weeks as so-called smouldering fires, leading to the formation of toxic products of incomplete combustion such as aromatic hydrocarbons, n-alkanes, polyterpenes [93], plasticizers including phthalic and orthophosphoric acid esters [94], polychlorinated dibenzofurans, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, polyhalogenated biphenyls [95], as well as dust (BC, PM10, and PM2.5) or smokes containing heavy metals [96].

For example, Elihn et al. [96], who studied a landfill fire in Kagghamra, Stockholm County, Sweden, where wood, demolition wood, and metal construction waste (such as gypsum, metals, and plastics) were accumulated, identified nitrogen oxides, PAHs, VOCs, PFAS, extractable organic fluorine (EOF), total fluorine (TF), particulate matter, BC, and metals in the air. It was discovered that during open burning, high concentrations of PM10, PM2.5, and BC co-occurred. High concentrations of the 16 analysed PAHs (acenaphthene, acenaphthylene, anthracene, benzo[a]anthracene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[k]fluoranthene, benzo[ghi]perylene, benzo[a]pyrene, chrysene, dibenz[a,h]anthracene, fluoranthene, fluorene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene, naphthalene, phenanthrene, and pyrene) coincided with high concentrations of PM and BC originating from the fire. The highest daily average concentrations were observed for benzo[a]anthracene (18 ng/m3) and chrysene (17 ng/m3). Elevated concentrations of TEOF (Total Extractable Organofluorine), which is a measure of the sum of all organic substances containing fluorine, including PFAS, were also detected in air samples, with the highest concentrations among PFAS being perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA, 8.5 pg/m3), fluorotelomer sulfonic acids 6:2 FTS (1.29 pg/m3) and 8:2 FTS. In the case of metals, it was found that the amount of metals such as Pb, Cd, and As in the air was significantly elevated during the period of open burning compared to the regional background [96].

To identify the substances that may be produced during a fire, it is essential to determine the types of waste accumulated at a given site and the chemical composition of each waste component. Mixed waste landfills are among the most challenging systems to manage or dispose of [97]. Among these types of systems are municipal waste landfills, which consist of a mixed mass of diverse waste. They often have differing characteristics in terms of physicochemical properties, biological activity, and state of matter.

Pollutant emissions and the nature of fires at landfills depend on the type of substances stored there. These fires can involve solids, liquids, and gases, such as in the case of landfill gas fires (resulting from the decomposition of organic substances and containing methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen) or biogas fires, which primarily contain methane. Fires at waste disposal sites differ from those in warehouses, industrial halls, and similar facilities. This difference stems from the fact that industrial facilities are usually designed and operated to minimize fire risk. They are also intended to facilitate firefighting operations, whereas at landfills, the method of waste storage can significantly hinder firefighting efforts. Moreover, when waste accumulation is impossible or unprofitable to recycle, it may even be perceived by some entities as a convenient way to dispose of it. This problem particularly concerns entities that store waste without the appropriate permits stipulated by law.

Research conducted by Ćetković et al. [98] and others has shown that burning tires emit significant amounts of harmful organic compounds, including aromatic hydrocarbons. Benzene, which is carcinogenic, and its derivatives, such as toluene, ethylbenzene, styrene, and xylenes, containing a single aromatic ring, have been identified. Among the toxins, benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are also present. These compounds can be found in both dust and, in the case of lighter ones with fewer rings, in the gas phase. Seidelt et al. [99] demonstrated that the composition of emitted compounds reflects the chemical composition of tires, which consist of 50% natural or synthetic rubber (by weight), 25% carbon black, 10% metal (mainly in the steel belt), 1% sulphur, 1% zinc oxide, and trace amounts of other materials. On the other hand, Downard et al. [100] indicated that among the products of tire combustion, in addition to PAHs (Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons), CO, CO2, SO2, particle number (PN), fine particulate matter mass (PM2.5), elemental carbon (EC), formaldehyde and acrolein are also present. Furthermore, it was shown that PM2.5 from tire combustion contains PAHs with nitrogen heteroatoms (azaarenes) and picene, a compound previously suggested as a unique product of coal combustion. A high degree of variability in daily emission factors was observed, reflecting the range of flaming and smouldering conditions of a large-scale fire.

Electrical waste landfills are characterized by a concentration of metals (including heavy metals, alkali metals, and alloys) and plastics, which determines the emission composition during a fire. Burning electrical waste can also be a source of various metals and their compounds—many of which are highly toxic, such as lead and cadmium. When various plastics are burned, even those not containing chlorine, compounds from the group of polychlorinated dibenzofurans and dibenzodioxins (PCDD/F, PBDD/F, PXDD/Fs) and polychlorinated dioxin-like biphenyls (DL-PCB), i.e., dioxins, can be formed in quantities dangerous to health and the environment [101]. The casings of electronic and electrical equipment, as well as cable insulation contain flame retardants, most commonly brominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). PBDEs released from plastics not only pose a health risk in themselves (affecting hormonal balance and fetal development), but their incineration typically also leads to the formation of brominated dioxin equivalents (PBDD/F), which are only slightly less harmful than PCDD/F themselves. Both PCDD/F, PBDEs, and PBDD/F are classified as persistent organic pollutants, meaning they remain in the environment for very long periods [102,103,104].

An important group of waste materials includes products containing brominated flame retardants (BFRs), which are increasingly used in fire protection. The emission of BFRs into the environment and the formation of both polybrominated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PBDD/F), as well as mixed polybromochloro-dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PBCDD/F or PXDD/F), are growing concerns due to the high toxicity of these compounds. Structural similarities between PBDD/F and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/F) suggest comparable formation pathways for both PBDD/F and PCDD/F. However, BFRs also act as specific precursors for the creation of additional PBDD/F [103,105]. It should also be emphasised that polybrominated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans (PBDD/Fs), polybromochloro-dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PXDD/Fs) are among the most toxic byproducts [105]. Theoretically, there are 4600 mixed bromochlorodibenzo-p-dioxin or dibenzofuran congeners (mixed PXDD/F), consisting of 3050 polybromochlorodibenzofurans (PXDF) and 1550 polybromochloro-dibenzo-p-dioxins (PXDD) [105,106]. This group of compounds includes substances that exhibit toxicity similar to that of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxins (TCDD), which are the most potent toxins in these compound groups. These substances can cause skin damage (chloracne), immunotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and adverse effects on reproduction, development, and endocrine function [105,107].

Vejerano et al. [108,109] demonstrated that nanomaterials added to polymer composites influence combustion byproducts. Nanomaterials embedded in nanocomposites can be potentially released during combustion in a form that may or may not differ from their original state. They found, among other things, that single-walled carbon nanotubes embedded in polymer matrices are released unmodified as isolated and joined fibres, while some nanomaterials undergo physicochemical modification during combustion. The total PAH emission factors were, on average, 6 times higher for fires involving waste containing nanomaterials compared to their bulk counterparts. The presence of nanomaterials in the waste stream led to higher emissions of some PAH compounds and lower emissions of others, depending on the type of waste. The main PAH compounds were phenanthrene and anthracene. The emissions were sensitive to the amount of nanomaterials in the waste. In case of metal oxide nanoparticles, such as NiO, Fe2O3, TiO2, which have an extensive surface area and are present in, for example, construction waste, a reduction in PAH emissions was observed due to the binding of organic substances to their surface [108,109].

A particularly problematic group of waste in recent times, apart from “nano-waste”, is waste that is not classified as “nano-waste” but contains nanoparticles in its structure. However, accurate quantification of such waste can only be achieved through analysis of the waste’s composition. This group of waste includes, among other things, packaging containing products containing metal nanoparticles, such as cream jars containing n-TiO2, and containers for transporting nanoparticles in the form of emulsions or powders. Filters used in industrial plants to capture nanoparticles emitted at various points in the technological process, offices, and customer service points also contain nanoparticles. However, there is no distinction based on particle composition, structure, or properties. Filters with adsorbed nanoparticles are stored and managed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, often through standard landfilling. This type of waste, due to the presence of heavy metals in the form of nanostructures, should be treated as hazardous waste. In the event of a fire involving this type of waste, nanoparticle emissions occur throughout the entire fire area. The lack of guidelines for controlling this group of compounds, as well as precise data on the number of nanoparticles, their composition, surface area, and biological and chemical activity emitted during uncontrolled combustion or hot embers, such as fires, prevents precise information about the threat level.

6. Quantitative and Qualitative Emission Analysis

Toxic substances enter a firefighter’s body through three routes: inhalation, the digestive system, and the skin [110]. The primary route of exposure for firefighters involved in rescue and extinguishing operations is the skin, which is the largest absorptive organ of the human body. During a fire, harmful substances are present on all surfaces at and near the scene of operations. Contaminants also settle on the rescuer’s equipment, often penetrating the material from which items like helmets, tools, straps, gloves, clothing, and balaclavas are made. They expose the firefighter to absorb them even after operations are complete.

The multitude and physicochemical diversity of compounds that can occur as toxic combustion products in the air necessitate the use of varied analytical techniques to assess the concentrations of compounds formed in chemical reactions accompanying the combustion process. There is no single technique that allows for a comprehensive determination of all toxic substances that may appear in gases and smokes produced during a fire. Direct-reading analysers, based on detectors such as NIR (Near InfraRed), TCD (Thermal Conductivity Detector), or ECD (Electron Capture Detector), can be used for the simultaneous analysis of several selected compounds. However, this is dependent on the sensors used and the concentration range (Table 2). Some of these concentrations can be determined almost instantaneously using direct-reading instruments, while other analyses require the collection of a physical sample. This is then analysed under laboratory conditions.

Table 2.

Examples of analytical techniques used to analyse selected substances emitted during fires.

As a rule, direct-reading instruments can immediately alert the user to the presence of contaminants in inhaled air. However, their low sensitivity renders them unsuitable for analysing more complex mixtures. Examples include attempts by the Provincial Sanitary and Epidemiological Station (WSSE) to measure ozone in swimming pool halls. Efforts have also been made to monitor benzene and formaldehyde levels in facilities belonging to Warsaw’s public transport companies, which ultimately failed due to the insufficient selectivity of such instruments. However, these instruments do allow continuous monitoring of fire pollutant movement using automated measuring stations or drones. Such measurement relies on monitoring indicator substances whose concentrations can be easily tracked by direct-reading instruments, such as total dust, SO2, NOx, or CO2.

Small concentrations of pollutants are determined in air samples. Air is passed through various types of filters and sorbents using passive methods (rarely used, where the sampler is simply exposed to atmospheric air) or active (aspirating) methods, in which an appropriate volume of air is passed through a suitably chosen sorbent. These sorbents utilize physical phenomena such as dissolution or adsorption, or chemical phenomena (chemisorption) to retain the analyte in the adsorbent or convert it into a more stable or easily measurable form. The sorbents used, categorized by their state of matter, are divided into:

- −

- Solid sorbents—categorized as non-porous (membrane filters and silica aerogels) and porous (silica gels, activated carbons, molecular sieves, porous glass); they can be impregnated with appropriate chemical compounds enabling chemisorption,

- −

- Liquid sorbents—used with impinger scrubbers in various forms, less commonly used due to the risk of damage and sample loss, as well as the aeration of analytes from the solution in some cases.

For collecting pollutants present in high concentrations, isolation methods using Tedlar bags and gas pipettes can be employed. For lower concentrations, it is essential to use sorbents that allow for the isolation of pollutants from a large volume of air into a small-sized sample. The sorbent and the air filtration process through it should be selected considering the expected concentration of the analyte in the air, the required uncertainty of the final result, and the variability of concentration over time. Mobile or stationary air aspirators are used to force airflow. Stationary aspirators are generally adapted to provide a higher flow rate, which positively impacts the sensitivity of the measurements.

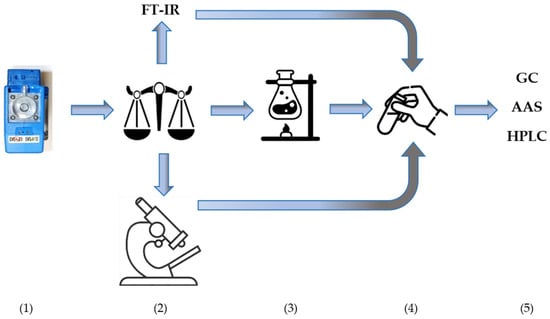

One of the significant substances emitted during fires is dust, whose composition can be very complex depending on the materials involved in the fire or the combustion process itself. Metals and their compounds, as well as highly toxic organic substances, are often adsorbed onto the dust’s surface. Therefore, dust analysis is one of the more important factors allowing for the determination of the degree of hazard posed by substances after a fire. However, for the collected information to be reliable, it is essential to use appropriate and validated analytical techniques covering both the material sampling process for testing and the qualitative-quantitative analysis itself. The analytical process, depending on the available tools, can be single-stage, based on online measurement, or multi-stage. This involves sample collection using a personal aspirator on a PVC filter, gravimetric analysis of total dust, followed by non-destructive analysis for quartz content using FT-IR, and then mineralization of the filter and analysis of metal content in the solution (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Stages of airborne dust analysis: (1) sampling using an individual aspirator onto a PVC filter, (2) analysis of the total dust using the gravimetric method, (3) FTIR analysis, (4) filter mineralization, (5) analysis of the metal content in the solution using the AAS, GC, HPLC or other analytical method.

For individuals involved in the incident, it is also crucial to determine the permissible concentration levels of harmful agents (Table 3) to implement appropriate protective measures.

Table 3.

Permissible concentration of selected harmful factors in the work environment in selected countries (in [mg/m3]).

It should be noted, however, that nanoparticles, whose number and diversity are rapidly growing and constitute an increasingly important component of emissions, are not subject to standard measurement. At the same time, they are not standardized, as is the case with, for example, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides, or PAH compounds. Given the development of nanotechnology and their proven toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic nature, nanoparticles should also be subject to monitoring and safety standards.

Another crucial aspect is the qualitative and quantitative assessment of emissions of a group of pollutants known as greenhouse gases or indirect gases, meaning they contribute to the greenhouse effect. Forest fires are a source of gases such as CO2, CH4, and particulate matter or VOCs, which contribute to climate change. Large-scale fires observed in recent years are causing a drastic increase in gas and particulate matter emissions, simultaneously destroying humans’ natural allies in the fight against climate change. Fires, primarily in natural areas, and climate change are therefore interconnected [141], which is why determining the qualitative and quantitative levels and trends of greenhouse gas emissions is so crucial. Creating a database containing information on emission levels and processes occurring during a fire, combined with machine learning, will enable prediction of the impact of fire on a given area and climate, and will enable appropriate actions to combat global climate change.

7. Conclusions

The dynamic development of civilization significantly influences the scale and types of threats. Hazardous chemical, mutagenic, allergenic, and corrosive substances emitted during fires can have a harmful effect on human health. Analysis of hazardous factors has shown that people participating in firefighting operations are exposed to numerous factors. Therefore, awareness of the threat, appropriate response at the first signs of danger, and the use of protective measures to limit the impact of harmful factors on health and life are fundamental.

One of these factors is smoke, which carries various substances, including toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic compounds. These are combustion products of fires, whose dynamics and pace far outweigh changes in material use and technological development.

In an era of rapid material innovation, it is essential to continuously update information on substances emitted during fires, taking into account both the location of their occurrence and the type and composition of the materials. Continuous integration of physicochemical data on new materials is essential, understanding their impact on fire processes. It should be noted that in addition to compounds such as carbon, sulphur, and nitrogen oxides, dust, and gases such as HCl, HCN, and HF, fires also emit dioxins, volatile organic compounds, and more or less complex organic structures.

Continuous technological advances and material modifications also alter the composition of emitted compounds. The emitted substances include an increasing number of metal nanoparticles and metal compounds, as well as nanoparticles of organic compounds. However, in the case of nanoparticles, their qualitative and quantitative analysis is currently insufficient, especially in the case of organic compounds, and requires comprehensive research. The changing composition of pollutants released during fires also requires the use of appropriate analytical techniques. These techniques are crucial for obtaining precise information about the composition of the air at the scene. Identification of compounds is also crucial for determining the impact on the health and lives of victims. Current analytical techniques are insufficient for the identification and qualitative and quantitative analysis of nanoparticles. Therefore, the development of procedures and tools in this area is necessary, as well as legal requirements covering the emission of nanoparticles of new substances as components of new products introduced to the market. The identification of nanosubstances will also allow for work to be undertaken on determining the processes occurring during emission, as nanostructures, due to their extensive surface area and chemical properties, different from their macro counterparts, may determine processes other than those previously known.

It should be emphasized that each fire should be analyzed individually, due to the diversity and broad spectrum of factors influencing its propagation and determining emissions and the impact on human health and the environment. This will allow for the development of a reliable database in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., J.G., P.S. and Ł.B.; formal analysis, A.R., J.G., P.S. and Ł.B.; investigation, A.R., J.G., P.S., Ł.B., J.R. and D.B.; resources, A.R., J.G., P.S. and Ł.B.; data curation, A.R., J.G., P.S. and Ł.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R., J.G., P.S., Ł.B. and J.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R., J.G., P.S., Ł.B., J.R. and D.B.; visualization, A.R. and J.G.; supervision, A.R. and J.G.; project administration, A.R. and J.G.; funding acquisition, A.R. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education as part of a granted subsidy for maintaining research potential in CNBOP-PIB—research work No. 074/BU/CNBOP-PIB/MNiSW/2018-2026 Testing the chemical composition of extinguishing agents and emissions, release of hazardous substances into the indoor air.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAS | Atomic Absorption Spectrometry |

| AFFF | Aqueous Film-Forming Foam |

| BaP | Benzo(a)pyrene |

| NMC type Batteries | Batteries (Nickel, Manganese, Cobalt) |

| BC | Black Carbon |

| BFRs | Brominated Flame Retardants |

| CNTs | Carbon Nanotubes |

| DLCs | Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds |

| DL-PCB | Dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls |

| DNPH | 2,4-Dinitrophenylhydrazine |

| DOP | Dioctyl phthalate |

| ECD | Electron Capture Detector |

| EOF | Extractable Organic Fluorine |

| ETAAS | Electrothermal Atomic Absorption |

| FAAS | Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GC-FID | Gas Chromatography–Flame Ionization Detector |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| GC-NCD | Gas Chromatography–Nitrogen Chemiluminescence Detector |

| HPLC-UV | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Ultraviolet |

| IC | Ion Chromatography |

| ICPE | Installation Classified for Environmental Protection |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission spectroscopy |

| MCE Membranes | Mixed Cellulose Ester Membranes |

| MDI | Methylene diphenyl diisocyanate |

| NIR | Near InfraRed |

| NMHC | Non-methane Hydrocarbons |

| NMVOC | Non-methane Volatile Organic Compounds |

| NOC | Nanoparticles of Organic Compounds |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| PBDDs | Polybrominated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins |

| PBDE | Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether |

| PBDFs | Polybrominated Dibenzofurans |

| PCBF | Polychloro-dibenzo Furan |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated biphenyls |

| PCDDs | Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins |

| PCDFs | Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans |

| PFAS | Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances |

| PFPeA | Perfluoropentanoic Acid |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PN | Particulate Number |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| PXDD/Fs | Mixed halogenated dioxins/furans |

| SOA | Secondary Organic Aerosols |

| TCD | Thermal Conductivity Detector |

| TCDD | 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin |

| TCP | Tricresyl Phosphate |

| TCPP | Tris(chloroisopropyl)phosphate |

| TDI | Toluene Diisocyanate |

| TEHP | Tris(2-ethylhexyl)phosphate |

| TEOF | Total Extractable Organofluorine |

| TF | Total Fluorine |

| THC | Total Hydrocarbon |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Martin, D.; Tomida, M.; Meacham, B. Environmental impact of fire. Fire Sci. Rev. 2016, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.; Johnston, F.H.; Keeley, J.E.; Krawchuk, M.A.; et al. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Data of the National Headquarters of the State Fire Service of Poland. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kgpsp/interwencje-psp (accessed on 28 April 2025). (In Polish)

- Fan, D.; Wang, M.; Liang, T.; He, H.; Zeng, Y.; Fu, B. Estimation and trend analysis of carbon emissions from forest fires in mainland China from 2011 to 2021. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, V. Total Number of reported fires in the U.S. from 1990 to 2021. Stat. Geogr. Nat. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/203760/total-number-of-reported-fires-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Hadden, R.; Switzer, C. Combustion Related Fire Products: A Review; The University of Edinburgh, School of Engineering: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2020; p. 139. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f8f09efd3bf7f49a3583570/Combustion_related_fire_products_review_ISSUE.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Lemieux, P.M.; Lutes, C.C.; Santoianni, D.A. Emissions of organic air toxics from open burning: A comprehensive review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2004, 30, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefiled, J.C. A Toxicological Review of the Products of Combustion; Health Protection Agency: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-85951-663-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pośniak, M. Chemical hazards in fire-fighting environments. Med. Pr. 2000, 51, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-García, C.; Santín, C.; Neris, J.; Sigmund, G.; Otero, X.L.; Manley, J.; González-Rodríguez, G.; Belcher, C.M.; Cerdà, A.; Marcotte, A.L.; et al. Chemical characteristics of wildfire ash across the globe and their environmental and socio-economic implications. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, K.; Ursič, M.; Tavzes, Č.; Knez, F. Review: The Use of Bench-Scale Tests to Determine Toxic Organic Compounds in Fire Effluents and to Subsequently Estimate Their Impact on the Environment. Fire Technol. 2021, 57, 625–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolstad-Johnson, D.M.; Burgess, J.L.; Grutchfield, C.D.; Storment, S.; Gerkin, R.; Wilson, J.R. Characterization of firefighters exposures during fire overhaul. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 2000, 61, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.J.; Cook, A.; Devine, B.; Thompson, P.J.; Weinstein, P. Effect of protective filters on fire fighter respiratory health during simulated bushfire smoke exposure. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, J.; Mäkelä, M.; Mikkola, J.; Huttu, I. Firefighters’ multiple exposure assessments in practice. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 213, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiston, J.R.; Davidson, W.; Attridge, S.; Li, G.T.; Brauer, M.; van Eeden, S.F. Wood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefighters. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 32, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. Guidelines for Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Mixtures; Risk Assessment Forum, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2014-11/documents/chem_mix_1986.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- IARC. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. Firefighting 2010, 98, 397–451. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, J.C.; Carreón, T.; Cogliano, V.J.; Demarini, D.M.; Fowler, B.A.; Goldstein, B.D.; Hemminki, K.; Hines, C.J.; Hoar Zahm, S.; Hopf, N.B.; et al. Research recommendations for selected IARC-classified agents. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caux, C.; O’Brien, C.; Viau, C. Determination of firefighter exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and benzene during firefighting using measurement of biological indicators. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2002, 17, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, J.; Mäkelä, M.; Mikkola, J.; Huttu, I. Firefighting trainers’ exposure to carcinogenic agents in smoke diving simulators. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarie, Y. Toxicity of fire smoke. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2002, 32, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMasters, G.K.; Genaidy, A.M.; Succop, P.; Deddens, J.; Sobeih, T.; Barriera-Viruet, H.; Dunning, K.; Lockey, J. Cancer risk among firefighters: A review and metaanalysis of 32 studies. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 48, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golga, K.; Weistenhofer, W. Fire fighters, combustion products, and urothelial cancer. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2008, 11, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descatha, A.; Dousseau, H.; Pitet, S.; Magnolini, F.; McMillan, N.; Mangelsdorf, N.; Swan, R.; Steve, J.M.; Pourret, D.; Fadel, M. Work Exposome and Related Disorders of Firefighters: An Overview of Systematized Reviews. Saf. Health Work. 2025, 16, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Xu, C.; Agnew, R.J.; Clifton, S.; Malone, T.R. Health Risks of Structural Firefighters from Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keir, J.L.A.; Akhtar, U.S.; Matschke, D.M.J.; Kirkham, T.L.; Chan, H.M.; Ayotte, P.; White, P.A.; Blais, J.M. Elevated Exposures to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Other Organic Mutagens in Ottawa Firefighters Participating in Emergency, On-Shift Fire Suppression. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12745–12755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, H.W. Percival Pott, The Environment and cancer. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrack, M. Best Practices Report. Minimizing Firefighters’ Exposure to Toxic Fire Effluents. University of Central Lancashire UCLan. 2020. Available online: https://www.ctif.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/FBU%20UCLan%20Contaminants%20Interim%20Best%20Practice%20gb.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- IARC Monographs Q&A. International Agency for Research n Cancer WHO. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Wright, S. Minimizing Firefighters’ Exposure to Toxic Fire Effluents. Best Practice Report. University of Central Lancashire UCLan. 2025. Available online: https://www.fbu.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/20426_02%20FBU%20Contaminants%20Best%20Practice%20UPDATED%20March%202025.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- NFPA. Firefighters and Cancer. Firefighting Is a Dangerous Profession, and a Growing Body of Research and Data Shows the Contributions That Job-Related Exposures Have in Chronic Illnesses, Such as Cancer and Heart Disease. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/emergency-response/firefighters-and-cancer (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Guidotti, T.L. Health Risks and Occupation as a Firefighter, a Report Prepared for the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Commonwealth of Australia. 2014. Available online: https://www.dva.gov.au/sites/default/files/guidotti_report.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Trojanowski, R.; Fthenakis, V. Nanoparticle emissions from residential wood combustion: A critical literature review, characterization, and recommendations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabajczyk, A.; Zielecka, M.; Porowski, R.; Hopke, P.K. Metal nanoparticles in the air: State of the art and future perspectives. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 3233–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire Safety Advice Centre. Fire Extinguishers–Classes, Colour Coding, Rating, Location and Maintenance. Available online: https://www.firesafe.org.uk/portable-fire-extinguisher-general/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Sutton, I. Chapter 11—Emergency management and security. In Process Risk and Reliability Management; Sutton, I., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich. NY, USA, 2010; pp. 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Lu, L.; Qian, X.; Kang, Q.; Fu, L. Research on the influence of driving gas types in compound jet on extinguishing the pool fire. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 363, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonov, A.; Skorobagatko, T.; Yakovchuk, R.; Sviatkevych, O. Interaction of Fire-Extinguishing Agents with Flame of Diesel Bio Fuel and Its Mixtures. Zesz. Nauk. SGSP 2020, 73, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 2:1992; Classification of Fires. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1992.

- Krebs, R.; Owens, J.; Luckarift, H. Formation and detection of hydrogen fluoride gas during fire fighting scenarios. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 127, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabajczyk, A.; Zielecka, M.; Gniazdowska, J. Application of Nanotechnology in Extinguishing Agents. Materials 2022, 15, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerson, J.T.; Chen, Y.; van der Werf, G.R.; Rogers, B.M.; Morton, D.C. Global burned area and biomass burning emissions from small fires. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, G04012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszczyk, K. Natural Fires in the Mediterranean Constitute no More Than 1–5 Percent, Says Environmental Biologist. 2021. Available online: https://scienceinpoland.pl/en/news/news%2C88833%2Cnatural-fires-mediterranean-constitute-no-more-1-5-percent-says-environmental (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Statistical Data of the National Headquarters of the State Fire Service of Poland. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kgpsp/ksrg (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Textor, C. Number of Forest Fires in China from 2013 to 2023. Stat. Geogr. Nat. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/300382/china-forest-fire-count/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Korhonen, V. Number of Wildland Fires in the United States from 1990 to 2024. Stat. Geogr. Nat. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/203983/-number-of-wildland-fires-in-the-us/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).