Abstract

Background: Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability globally. Conventional physiotherapy, while effective, faces barriers including accessibility and adherence. Telerehabilitation augmented by wearable sensor technology and AI-driven feedback offers a scalable alternative. Objective: This pilot randomized controlled trial compared the feasibility, safety, and preliminary clinical effectiveness of a sensor-based telerehabilitation protocol using the KneE-PAD patient monitoring approach which was also combined with an avatar-guided visual feedback add-on tool. Although this approach is capable of AI-driven postural error detection, this feature was not enabled during the current study, and feedback was provided solely through visual cues. Methods: Twenty adults with radiographically confirmed Kellgren–Lawrence grade 1 to 3 knee OA were randomized into two groups (Control/Intervention groups, n = 10 in each). The control group received in-person physiotherapy, while the intervention group engaged in remote rehabilitation supported by wearable sEMG and IMU sensors. The 8-week program included supervised and home-based sessions. Primary outcomes were WOMAC scores (Functionality/Pain), quadriceps strength, and sEMG-derived neuromuscular activation. Secondary outcomes included Timed Up and Go test (TUG), psychological measures (HADS, TSK), and self-efficacy measure (ASES). Analyses employed both parametric and non-parametric statistics including an effect size estimation. Results: Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in WOMAC total scores (Intervention: −11.8 points; Control: −6.4 points), exceeding the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for knee OA. Strength and mobility also improved significantly in both groups, with the Intervention group showing superior gains in sEMG measures (RMS: p = 0.0077; Peak-to-Peak: p < 0.005), indicating enhanced neuromuscular adaptation. TUG performance improved more in the intervention group (–3.17 s vs. –2.57 s, p = 0.037). Psychological outcomes favored the control group, particularly in depression scores (HADS-D, t(18) = 2.37, p = 0.03). Adherence was high (94.8%), with zero attrition and no adverse events. Conclusions: The KneE-PAD monitoring approach offers a feasible and clinically effective alternative to conventional physiotherapy, enhancing neuromuscular outcomes through real-time sensor feedback. These findings support the viability of intelligent telerehabilitation for scalable OA care and inform the design of future large-scale trials.

1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability and chronic pain worldwide, particularly among aging populations. Characterized by progressive degradation of articular cartilage, subchondral bone changes, and synovial inflammation, OA severely impairs functional mobility and quality of life [1]. Globally, over 300 million individuals are affected, with the prevalence expected to rise as life expectancy increases [2,3]. In addition to physical impairments, OA is associated with comorbid depression, reduced productivity, and a substantial economic burden on health systems [1,4].

First-line OA management typically includes conservative, non-pharmacological strategies such as physiotherapy and structured exercise programs [5,6]. Exercise therapy—particularly muscle strengthening and neuromuscular training—has been consistently shown to reduce pain and improve physical function [7,8]. However, widespread implementation of these interventions remains limited due to barriers such as clinic availability, transportation, cost, and inconsistent adherence to home-based programs [9,10].

To overcome these limitations, telerehabilitation has emerged as a promising alternative that enables remote delivery of therapeutic interventions. This approach leverages digital platforms to provide supervised or semi-supervised exercise programs with clinician oversight, offering solutions for geographic and logistical constraints. Systematic reviews confirm the effectiveness of telerehabilitation in OA, reporting improvements in both pain and physical function that are comparable to traditional face-to-face physiotherapy [11,12,13]. Furthermore, remote interventions may enhance patient autonomy and reduce healthcare costs, supporting long-term sustainability.

Despite promising outcomes, many existing telerehabilitation systems rely on generic video instruction or basic self-report tools. These lack real-time feedback mechanisms, making it difficult to ensure correct execution or track objective progress. The recent integration of wearable sensor technologies—such as surface electromyography (sEMG) and inertial measurement units (IMUs)—has enabled a new era of sensor-guided rehabilitation. These tools allow for continuous monitoring of muscle activation, joint angles, and movement velocity, facilitating more precise and personalized feedback [14,15].

In this context, KneE-PAD (Knee Exercise-Postural Assessment Dataset) was developed as the first large-scale dataset capturing real patient movement during unsupervised rehabilitation tasks. Unlike prior datasets based on healthy volunteers mimicking dysfunction, KneE-PAD comprises over 2000 annotated sensor recordings from patients with knee OA performing exercises like squats, walking, and leg extensions, collected over six months with 8 synchronized sEMG and IMU sensors [16,17]. This rich, multimodal dataset supports the development of machine learning models capable of detecting postural errors, identifying motor compensations, and tailoring feedback to optimize outcomes. It is worth noting that while KneE-PAD refers to a dataset, the monitoring and assessment framework used in this study shares the same name.

The current pilot study evaluates a novel telerehabilitation protocol utilizing the KneE-PAD monitoring system to deliver individualized, sensor-driven rehabilitation with real-time biomechanical feedback. The study compares this approach to conventional physiotherapy, examining feasibility, adherence, patient satisfaction, and short-term clinical outcomes across multiple dimensions including pain, strength, neuromuscular activation, and psychological status. Of particular interest is the platform’s ability to enhance engagement through visual cues and data-driven personalization while maintaining the safety and effectiveness of in-person care.

The innovation of this pilot trial lies in its integration of wearable technology, AI-assisted movement analytics, and patient-centered design principles to enable truly remote, autonomous rehabilitation. The potential to scale such solutions to larger populations and incorporate them into mainstream musculoskeletal care offers substantial implications for clinical practice. Furthermore, this study serves as a methodological foundation for future large-scale randomized trials, contributing to evidence-based digital rehabilitation frameworks in OA care.

In summary, as the burden of OA continues to grow, the development of scalable, intelligent, and home-based rehabilitation systems is critical. This pilot trial explores the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of a next-generation telerehabilitation platform that combines objective sensor data, real-time feedback, and remote monitoring to deliver individualized care for people with knee osteoarthritis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a two-arm, parallel-group, single-blind pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) aimed at evaluating the feasibility, safety, and preliminary effectiveness of a novel telerehabilitation protocol compared to conventional physiotherapy for patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA). The study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and received approval from the University of West Attica’s Research Ethics Committee (Approval Protocol: 61121/27-06-2023) [18]. It was prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06416332) (date of registration: 27 June 2023).

2.2. Participants

Twenty participants aged between 40 and 70 years with radiographically confirmed Kellgren–Lawrence grade 1 to 3 knee OA were enrolled. Inclusion criteria required participants to be capable of providing informed consent, ambulate independently, and follow instructions. Exclusion criteria included prior knee surgery within three years, neurological or cognitive impairments, inflammatory arthritis, recent physiotherapy or lower limb training, or contraindications to physical activity. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Participant Demographics

Demographic characteristics were assessed to confirm baseline comparability between the intervention (tele-rehabilitation) and control (in-person therapy) groups. Categorical variables included gender, occupational status, side of affected limb, and treatment assignment (Table 1). The sample was composed of 45% males and 55% females (Figure 1). Most participants were employed in the private sector (45%), followed by retirees (20%) and state employees (15%) (Figure 2). Laterality was equally distributed between right and left side (50% each), minimizing asymmetry bias.

Table 1.

Categorical Participant Characteristics.

Figure 1.

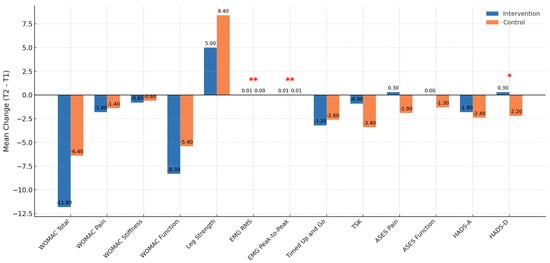

Between-group comparison of outcome changes. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

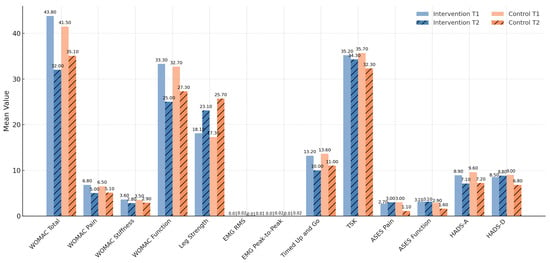

Within-group comparison of outcomes at T1 and T2.

Continuous demographic variables are summarized in Table 2. The average age was 56.0 years (SD = 7.3), with a median of 59 (Figure 3). Mean height was 168.5 cm (SD = 10.4; IQR = 16.25 cm), and weight was 88.95 kg (SD = 14.98; median = 86.5 kg; IQR = 18.5 kg) (Figure 4). No statistically significant baseline differences were detected between the groups in demographic or clinical parameters, confirming balanced initial conditions for subsequent comparisons.

Table 2.

Summary of Continuous Participant Characteristics.

Figure 3.

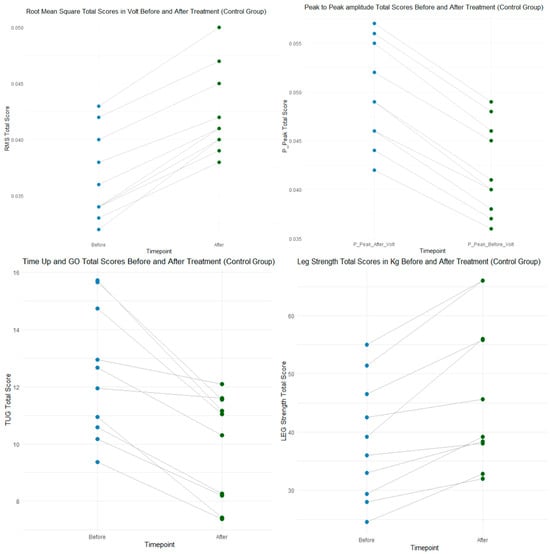

Baseline—1st Follow Up Control Group.

Figure 4.

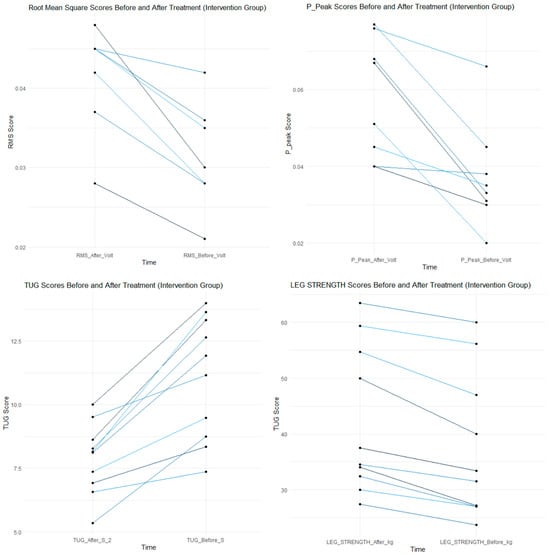

Baseline—1st Follow Up Intervention Group.

2.3. Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into two groups (n = 10 per group) using computer-generated random numbers and allocation concealment with sealed opaque envelopes. An independent researcher who was not involved in recruitment or assessment procedures managed randomization. Blinding was maintained for outcome assessors, who were unaware of group assignments, to minimize bias in outcome measurements. Given the behavioral nature of the interventions, participant blinding was not feasible; however, assessor blinding was strictly maintained to minimize measurement bias. Outcome assessors were unaware of group allocation, and participants were instructed not to disclose their treatment modality during evaluations. Potential expectancy effects were mitigated through standardized pre-assessment instructions.

2.4. Interventions

Both groups followed an 8-week structured physiotherapy program, based on international clinical guidelines for OA management [6]. Each participant received two supervised sessions weekly (45 min) and was instructed to complete three additional home-based sessions. Group A attended in-person physiotherapy at affiliated outpatient clinics. Sessions included isometric exercises for quadriceps and gluteal muscles, balance training using wobble boards, and proprioceptive tasks with elastic bands.

Group B followed the identical protocol remotely through a telerehabilitation platform supported by wearable technology and the KneE-PAD data capturing approach. Participants were equipped with Trigno Avanti wearable sensors (sEMG and IMU; [19]), enabling real-time biofeedback during exercise sessions. In addition to this, they wore 17 XSENS awinda IMU sensors (60 Hz sampling rate), providing real-time feedback via a visual avatar based on the processed sensor signals. During the evaluation, the developed AI-based module for automatic classification of exercise correctness (i.e., correct vs. faulty execution) was not utilized [20]. Feedback was visual-only, without automated labeling of performance quality. The AI-based postural correction module was intentionally disabled to ensure unbiased feasibility evaluation of real-time sensor feedback; its future activation is expected to further enhance corrective guidance and motor learning. Physiotherapists monitored movements live.

As described in the introduction, the KneE-PAD dataset was developed during a previous phase involving 31 patients with knee OA, yielding 2086 annotated files used for training machine learning algorithms for posture estimation [16]. Sensor placements in this study, similarly to the initial one, adhered to SENIAM guidelines to ensure accurate capture of lower limb muscle activity. A detailed description of all exercises, including sets, repetitions, and intensity parameters, is provided in the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D, where Figures S1–S30 illustrate the initial and final positions of each movement performed during the KneE-PAD intervention protocol. The same exercise sequence and parameters were applied in both the in-person and telerehabilitation groups.

2.5. Outcome Measures

Outcomes were assessed at baseline and after the 8-week intervention, covering patient-reported, functional, physiological, and psychological dimensions through validated instruments and objective devices. Clinical symptoms were assessed with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), muscle strength with handheld dynamometry, neuromuscular activity with surface electromyography (sEMG) sensors equipped with inertial measurement units (IMUs), and functional mobility with the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. Psychological dimensions were captured with the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES), the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), all validated in Greek clinical populations.

Primary outcomes included pain, stiffness, and neuromuscular performance. The WOMAC is a 24-item self-administered questionnaire with three subscales (pain: 5 items; stiffness: 2 items; physical function: 17 items), each scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4), with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The Greek version has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in osteoarthritis cohorts [21]. Quadriceps isometric strength was assessed with the ActivForce 2 handheld dynamometer (ActivBody, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.), a portable tool with excellent reproducibility (ICC = 0.75–0.95) for isometric strength testing [22,23]. Neuromuscular activation was recorded via sEMG using Delsys Trigno Avanti sensors [19], with electrodes placed according to SENIAM guidelines to ensure accurate and reproducible biosignal acquisition.

Secondary outcomes included mobility, self-efficacy, kinesiophobia, and psychological well-being. Mobility was assessed with the TUG test, which measures the time required to rise from a chair, walk 3 m, return, and sit, a validated indicator of balance and functional mobility [24]. Self-efficacy was measured with the ASES, a 20-item scale comprising three domains (pain, function, symptom management) rated on a 10-point scale, with the Greek version showing adequate reliability [25,26]. Kinesiophobia was evaluated with the 17-item TSK (score range: 17–68), where higher scores denote greater fear of movement; the Greek version has been validated in musculoskeletal populations [27,28]. Anxiety and depression were assessed using the HADS, a 14-item instrument with two subscales (7 items each; score range: 0–21), with higher scores reflecting more severe symptoms. Its Greek version has demonstrated robust validity in both clinical and general populations [29,30].

Adherence was monitored via participant-maintained exercise diaries and therapist logs, and calculated as the percentage of completed sessions relative to the total prescribed. All assessments were performed by trained, blinded assessors in a standardized sequence to minimize measurement bias.

2.6. Feasibility Indicators

Feasibility of the intervention was assessed using key indicators such as recruitment rate, session attendance, and participant retention throughout the study period. Treatment engagement was monitored through digital exercise diaries and therapist-maintained records, allowing for evaluation of session completion rates relative to the prescribed program. Retention was defined as the proportion of participants who completed both baseline and post-intervention assessments. All participant activity was documented, and no dropouts or adverse events were recorded during the intervention.

These findings offered valuable insight into implementation logistics, participant acceptance of the digital tools, and overall procedural efficiency, informing the future development and refinement of large-scale clinical trials exploring digitally assisted physiotherapy in individuals with knee osteoarthritis.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The primary objective was to evaluate both within-group changes over time and between-group differences in outcomes following intervention, comparing a tele-rehabilitation protocol with conventional in-person therapy.

Descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, and range) were computed for all outcome variables to summarize participant characteristics and clinical measures. Data visualization included histograms, boxplots, and Q-Q plots to inspect distributional properties and identify outliers.

Prior to inferential testing, the assumption of normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. For visual confirmation, Q-Q plots were reviewed. Homogeneity of variances between groups was evaluated via Levene’s test.

To examine pre-to-post intervention changes within each group, paired samples t-tests were employed for normally distributed data. In cases where the normality assumption was violated, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used as a robust non-parametric alternative. All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Between-group comparisons were based on change scores (post–pre) for each outcome metric. When the assumption of equal variances was met, independent samples t-tests (pooled) were used. Otherwise, Welch’s t-test, which does not assume equal variances, was applied. For non-normally distributed variables or unequal variances, the Mann–Whitney U test was implemented.

To account for potential violations of distributional assumptions and to reinforce the robustness of findings, permutation tests were also conducted. These resampling-based tests offer reliable inference under minimal assumptions and are especially suitable in smaller sample contexts or skewed distributions.

All analyses were performed at a 95% confidence level, and where appropriate, effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, rank-biserial correlation) were calculated to complement p-values and provide insight into clinical relevance.

As this was an exploratory pilot study, no formal correction for multiple comparisons (e.g., Bonferroni) was applied. Nevertheless, the potential inflation of Type I error was acknowledged and mitigated through effect size reporting and permutation-based validation. The analytical focus was primarily on identifying feasibility patterns and estimating effect sizes to inform the design of future adequately powered trials.

Sample Size Estimation for Future Trial

To inform the design of a future randomized controlled trial (RCT), an a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 software [31]. Based on the primary outcomes assessed in this pilot study, effect sizes were derived from relevant meta-analyses and prior trials. Specifically, Cottrell et al. [32] reported a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.66 for pain-related outcomes, while [33] an SMD of 0.42 in quadriceps strength following rehabilitation interventions involving isokinetic dynamometry was observed. Assuming an α level of 0.05, statistical power of 80%, and a two-tailed test, the minimum sample size required was estimated at 34 participants. Accounting for a 10% attrition rate, the projected recruitment targeted for the full-scale trial is 42 participants.

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcome Measures

3.1.1. WOMAC Index

Significant improvements were observed in the WOMAC total score and its subscales (pain, stiffness, and function) in both the intervention and control groups.

In the intervention group, the WOMAC total score decreased from 43.8 ± 18.5 to 32.0 ± 16.9 (t = 2.38, p = 0.027, Cohen’s d = 0.60). Pain scores improved from 6.8 ± 3.0 to 5.0 ± 2.3 (t = 2.32, p = 0.030), stiffness from 3.6 ± 1.2 to 2.8 ± 1.0 (t = 2.39, p = 0.025), and function from 33.3 ± 13.1 to 25.0 ± 11.5 (t = 2.29, p = 0.034).

In the control group, the WOMAC total score decreased from 41.5 ± 17.9 to 35.1 ± 16.0 (t = 2.45, p = 0.021), with pain improving from 6.5 ± 2.8 to 5.1 ± 2.4 (t = 2.23, p = 0.040), stiffness from 3.5 ± 1.1 to 2.9 ± 1.0 (t = 2.82, p = 0.010), and function from 32.7 ± 12.8 to 27.3 ± 11.3 (t = 2.31, p = 0.030).

No significant interaction effect between groups was detected (t = 1.91, p = 0.067), suggesting that both groups improved comparably over time.

Importantly, the mean reductions in WOMAC scores exceeded the established minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 9–12 units for patients with knee OA, Refs. [34,35] indicating that the observed improvements are not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful in both groups.

3.1.2. Quadriceps Strength (Dynamometry)

Quadriceps strength increased significantly in both groups. The intervention group improved from 18.1 ± 5.9 kg to 23.1 ± 6.0 kg (t = 3.90, p = 0.0012, Cohen’s d = 0.90), while the control group improved from 17.3 ± 6.1 kg to 25.7 ± 5.6 kg (t = 4.44, p = 0.0004, d = 1.26). Although both improvements were large, the between-group difference was not significant (t = 1.13, p = 0.270). From a clinical standpoint, both groups surpassed the MCID threshold of ≥5 kg for quadriceps strength gains in knee OA populations [23,36], confirming the practical relevance of the observed improvements beyond statistical testing.

3.1.3. Surface Electromyography (sEMG)

Surface EMG variables revealed stronger neuromuscular gains in the intervention group. RMS amplitude increased from 0.011 ± 0.002 mV to 0.016 ± 0.002 mV (t = 6.83, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.18), while the control group improved from 0.011 ± 0.002 mV to 0.014 ± 0.002 mV (t = 5.31, p < 0.001, d = 1.00). The group × time interaction for RMS was statistically significant (t = 2.89, p = 0.008), suggesting greater neuromuscular activation in the intervention group.

Peak-to-peak amplitude rose from 0.015 ± 0.002 mV to 0.022 ± 0.003 mV in the intervention group (t = 7.92, p < 0.001, d = 1.53), compared to 0.015 ± 0.002 mV to 0.020 ± 0.003 mV in the control group (t = 6.39, p < 0.001, d = 1.30). Again, a significant group × time interaction was observed (t = 3.26, p = 0.0023), further supporting enhanced neuromuscular adaptation with the sensor-based intervention.

Although no standardized MCID exists for sEMG outcomes, prior work has emphasized that test–retest reliability is robust in knee OA patients [36], and the large effect sizes (d > 1.0) observed here indicate clinically relevant neuromuscular adaptations, likely facilitated by real-time biofeedback during telerehabilitation.

3.2. Secondary Outcome Measures

3.2.1. Timed up and Go (TUG)

Mobility, assessed by the TUG test, improved significantly in both groups. The intervention group improved from 13.2 ± 2.7 s to 10.0 ± 2.4 s (t = 6.24, p < 0.0001, Cohen’s d = 1.19), while the control group improved from 13.6 ± 2.9 s to 11.0 ± 2.5 s (t = 5.40, p = 0.0002, d = 1.07). The group × time interaction was not significant (t = 0.91, p = 0.37), indicating comparable improvements. Importantly, the observed reductions exceeded the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of ~1.5–2.0 s for older adults with mobility limitations [37], confirming that the gains were both statistically and clinically meaningful.

3.2.2. Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES)

The control group improved in ASES Pain from 3.0 ± 1.5 to 1.1 ± 1.2 (t = 2.44, p = 0.025, d = 0.66) and ASES Function from 2.9 ± 1.4 to 1.6 ± 1.2 (t = 2.14, p = 0.045, d = 0.52), while no significant changes were observed in the intervention group. Group × time interactions were not significant (Pain: t = 0.85, p = 0.41; Function: t = 1.09, p = 0.29). Although only the control group showed significant within-group changes, the magnitude of change (Δ > 1 point) corresponds to the MCID for self-efficacy [25,38] measures in arthritis populations, supporting a clinically relevant improvement in self-management confidence.

3.2.3. Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK)

No significant changes were observed in TSK scores. The intervention group changed from 35.2 ± 6.9 to 34.3 ± 7.5 (t = 0.31, p = 0.756), while the control group moved from 35.7 ± 6.7 to 32.3 ± 7.1 (t = 1.10, p = 0.294). The group × time interaction was not significant (t = 0.74, p = 0.47). Given that the MCID for TSK is estimated at ~4 points [39], neither group reached a clinically meaningful change, suggesting that kinesiophobia remained largely unaffected by either intervention.

3.2.4. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

Anxiety scores (HADS-A) decreased in both groups, but significantly only in the control group (from 9.6 ± 3.4 to 7.2 ± 3.3, t = 2.51, p = 0.022). Depression scores (HADS-D) improved significantly only in the control group (from 9.0 ± 3.1 to 6.8 ± 2.9, t = 2.50, p = 0.024, d = 0.68), while the intervention group remained stable (from 8.5 ± 2.9 to 8.8 ± 3.0, t = −0.15, p = 0.882). Between-group interaction for depression was significant (t = 2.29, p = 0.03).

These changes exceeded the MCID for HADS, estimated at 1.5–1.8 points in chronic disease populations [40,41] indicating that reductions in depression symptoms among the control group were both statistically significant and clinically meaningful, while anxiety reductions remained modest

Summary of psychological outcomes (TSK, HADS, ASES): Comprehensive data for the psychological and self-efficacy measures are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. TSK scores decreased by 3.4 points in the Control group (p = 0.294) and 0.9 points in the Intervention group (p = 0.756), showing no statistically significant or clinically meaningful change (MCID ≈ 4 points). For HADS, the Control group demonstrated significant reductions in both Anxiety (−2.4 points, p = 0.022) and Depression (−2.2 points, p = 0.024), whereas the Intervention group showed non-significant changes (HADS-A = −1.8, p = 0.141; HADS-D = +0.3, p = 0.882). Regarding ASES, the Control group exhibited significant improvements in Pain (+1.92 points, p = 0.025) and Function (+1.24 points, p = 0.045), exceeding the MCID (~1 point) for arthritis self-efficacy, while the Intervention group showed no significant change. Full pre- and post-intervention means, 95% confidence intervals, p-values, and Cohen’s d effect sizes are detailed in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Primary Outcome Measures by Group. Primary outcome measures presented separately for each group (Control and Intervention). The table reports means and standard deviations at T1 and T2, 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T2, p-values for within-group comparisons, group × time interaction effects, and Cohen’s d effect sizes.

Table 4.

Secondary Outcome Measures by Group. Secondary outcome measures presented separately for each group (Control and Intervention). The table reports means and standard deviations at T1 and T2, 95% confidence intervals (CI) for T2, p-values for within-group comparisons, group × time interaction effects, and Cohen’s d effect sizes.

3.3. Between-Group Comparison of Outcomes

Although both intervention and control groups showed significant within-group improvements in primary and secondary outcomes, several between-group differences emerged, shedding light on the distinct contributions of each therapeutic approach (Table 5).

Table 5.

Between-Group Comparison. Comparative analysis of outcome measures between Intervention and Control groups. Values represent means and standard deviations at T1 and T2, group × time interaction p-values, and Cohen’s d effect sizes for both groups.

For WOMAC scores, both groups improved significantly in total, pain, stiffness, and function subscales. No statistically significant group × time interaction was found (p = 0.067). However, the intervention group demonstrated a numerically larger reduction in the function subscale (−8.3 vs. −5.4 points). Both groups exceeded the minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) [35] threshold for WOMAC (≈9–12 units), as defined by OMERACT–OARSI. Refs. [34,35] confirming that functional improvements were not only statistically but also clinically meaningful in both settings.

Although both groups demonstrated improvements in quadriceps strength, the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance (interaction p = 0.270). Specifically, the control group improved by +8.42 kg and the intervention group by +5.04 kg, with large within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.26 and 0.90, respectively). These findings indicate that there was no statistically significant difference in strength gains between the groups.

Neuromuscular activation, as assessed by surface EMG, revealed significant between-group effects favoring the intervention group. The group × time interaction was statistically significant for both RMS amplitude (t = 2.94, p = 0.0077) and peak-to-peak amplitude (t = 3.43, p = 0.0023), with larger gains in the intervention group (ΔRMS = +0.005 mV; ΔPP = +0.007 mV). Given that EMG amplitude changes reflect enhanced motor unit recruitment and neuromuscular efficiency, these findings suggest superior neural adaptation facilitated by biofeedback and consistent motor retraining in the tele-rehabilitation system.

In mobility, both groups improved in TUG performance. The intervention group exhibited a slightly larger reduction (−3.17 s vs. −2.57 s), although between-group interaction was not significant (t = 0.91, p = 0.37). Notably, both groups exceeded the MCID for TUG [37], (~1.5–2.0 s), confirming that functional mobility gains were clinically meaningful. Furthermore, the post-intervention TUG score was lower in the intervention group (10.0 s vs. 11.0 s), suggesting more rapid gait efficiency recovery.

Regarding self-efficacy, only the control group showed significant improvements in ASES pain and function subscales. While the intervention group remained unchanged, the observed improvements in the control group (Δ > 1 unit) exceeded the MCID for arthritis self-efficacy [38] (~1 point), indicating clinically relevant gains in perceived self-management ability.

For psychological outcomes, particularly depression (HADS-D), a significant group × time interaction was detected (t = 2.26, p = 0.03). The control group improved from 9.0 ± 3.1 to 6.8 ± 2.9 (p = 0.024), a mean reduction exceeding the MCID [40] for HADS-D (1.5–1.8 points), while the intervention group remained stable. In contrast, anxiety symptoms (HADS-A) decreased slightly in both groups but without significant between-group differences.

Kinesiophobia (TSK) scores declined marginally in the control group (−3.4 points) and remained stable in the intervention group (−0.9 points). Neither group reached the MCID [39] threshold for TSK (~4 points), indicating that reductions in fear of movement were not clinically relevant.

In summary, sEMG outcomes and HADS-D presented statistically and clinically significant between-group differences, favoring neuromuscular adaptation in the intervention group and psychological relief in the control group. All other outcomes showed improvements beyond MCID [36,37,38,39,40] thresholds in both groups, with comparable effectiveness between modalities.

3.4. Visualization of Key Findings

To enhance interpretability, representative visualizations of the main functional and neuromuscular outcomes were included (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

These plots illustrate the pre–post changes in Timed Up-and-Go performance, quadriceps strength, and EMG-derived RMS and peak-to-peak activation for the Control and Intervention groups.

The figures clearly demonstrate significant within-group improvements, with greater neuromuscular activation gains observed in the Intervention group, consistent with the statistical findings reported in Table 2 and Table 3. This visualization complements the quantitative data and facilitates an intuitive understanding of the intervention effects.

4. Discussion

4.1. PROMs vs. Objective Metrics

Both groups demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in subjective measures, as assessed by the WOMAC Index. The WOMAC is a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) that evaluates patient-perceived pain, stiffness, and physical function [21]. PROMs have been recognized as essential tools in chronic musculoskeletal rehabilitation, aligning with the principles of value-based and patient-centered care [25,26]. However, the lack of statistically significant between-group differences in PROMs (WOMAC, HADS, TSK) aligns with previous literature, indicating their limited sensitivity in short-term interventions or technologically novel settings [10,15], where expectations may elicit placebo or masking effects [11,12].

4.2. Neuromuscular Gains and Functional Performance

The KneE-PAD intervention resulted in statistically and clinically significant increases in RMS and peak-to-peak sEMG amplitudes, reflecting improved motor unit activation and recruitment. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as sEMG amplitude may also be influenced by electrode placement accuracy, skin impedance, and signal normalization procedures, and therefore may not directly quantify neural adaptation. These outcomes, supported by large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 1.0), are consistent with the hypothesis that real-time biofeedback promotes motor relearning through enhanced sensorimotor integration [14,42]. Compared to conventional telerehabilitation protocols that rely mainly on video guidance [43], the KneE-PAD system offers active posture correction and interactive feedback [16,17]. Functional improvements were further confirmed by the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, with the intervention group surpassing the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) [24].

Psychological Outcomes Interpretation: The limited improvements observed in psychological measures (HADS-D, TSK, and ASES) may be attributed to the absence of structured psychological support, such as cognitive-behavioral guidance, and the relatively short duration of the intervention. While both programs effectively improved physical outcomes, addressing emotional and cognitive aspects of pain management likely requires dedicated behavioral interventions. Future iterations of the KneE-PAD system could integrate digital cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) modules or e-coaching components to enhance affective and self-efficacy outcomes, fostering a more holistic biopsychosocial rehabilitation approach.

4.3. Muscle Strength and Psychological Outcomes

Quadriceps strength improved significantly in both groups, with slightly higher gains in the control group—possibly due to in-person therapist-supervised progressive resistance training. However, the intervention group still exceeded the MCID without supervision, affirming the potential of remote sensor-based training [44]. Regarding psychological outcomes, depressive symptoms declined more notably in the control group, likely due to direct therapeutic rapport. However, the digital group also showed modest improvement, suggesting beneficial effects from perceived autonomy and engagement [1,28,30]. Although both groups followed identical exercise content, the higher degree of therapist interaction in the control group may have contributed to better self-efficacy and affective outcomes. Future studies should consider equalizing supervision intensity or including motivational e-coaching elements to control for this effect.

These findings underscore the need to integrate digital CBT or e-coaching tools into future iterations [43,45]. While both modalities produced clinically meaningful gains, between-group differences were largely non-statistically significant; hence, the results should be interpreted as supporting comparable rather than superior effectiveness. This finding reinforces the feasibility of digital physiotherapy approaches as a viable alternative rather than a replacement to conventional in-person care.

4.4. Feasibility, Usability, and Safety

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, usability, and safety of the KneE-PAD platform. The results confirm full feasibility, with adherence rates exceeding 94% and no adverse events reported. The accurate and uninterrupted collection of biosignals in real-time also supports its technical reliability [46,47]. Usability was confirmed through qualitative and compliance data: participants reported ease of use, comprehension of instructions, and a positive overall experience. Although standardized tools like SUS were not applied, user feedback and compliance data indicate high acceptance and long-term use potential [3,48]. This serves as a fundamental issue in applying this specific type of research in larger samples of patients.

4.5. Clinical Integration and Scalability

KneE-PAD demonstrates promise for remote high-quality care delivery to patients facing geographical, mobility, or socioeconomic limitations. The real-time processing of biosignals enables the development of predictive machine-learning models that could be embedded in hybrid care models (e.g., asynchronous supervision with periodic check-ins) [16,20]. Additionally, integrating psychological support modules (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, coaching) may enable the platform to address the psychosocial dimension of recovery, supporting holistic and patient-centered rehabilitation [6,49]. From a health policy perspective, the implementation of such platforms could reduce per-session costs, alleviate clinical workload, and enhance access for underserved populations, in alignment with modern principles of technology-enabled, patient-centered care [6,44].

5. Strengths and Limitations

This study’s primary strength lies in its integration of wearable sensing with home-based rehabilitation, enabling high-resolution monitoring without compromising ecological validity. The inclusion of multiple physical measures (sEMG, TUG) alongside psychological and functional assessments provided a multidimensional view of therapeutic impact. Zero attrition and absence of technical failures further reinforce intervention feasibility.

On the other hand, although the sample size was small, which is inherent in pilot designs, this was counterbalanced by robust within-group improvements that exceeded MCID thresholds. Use of non-parametric and permutation-based methods enhanced statistical reliability despite limited power.

Furthermore, the 8-week duration may appear restrictive; however, it mirrors durations in existing digital rehabilitation literature and sets the stage for more prolonged studies. On the psychosocial perspective, while the lack of structured psychological support may have blunted effects on affective domains, even modest improvements suggest underlying behavioral activation potential [25]. This is enforced by the fact that although formal usability assessments were omitted, high adherence and satisfaction indicated strong user acceptance, which can be further validated in future work. Future studies should include standardized usability and user experience tools, such as the System Usability Scale (SUS), the mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ), or the UTAUT2 model, to objectively quantify system acceptability and enhance comparability across digital rehabilitation studies.

Lastly and also importantly, the use of sensor-derived metrics addressed the often-reported ceiling effects of PROMs in digitally fluent cohorts. The study thus underscores the value of combining subjective and objective outcomes when assessing technology-enhanced interventions. Given the pilot nature of this study, the limited sample size may have constrained statistical power, increasing the risk of type II error. Therefore, findings should be interpreted as preliminary indicators guiding future adequately powered trials.

6. Future Directions

Future trials should scale the sample size and extend follow-up periods to assess long-term adherence, functional maintenance, and relapse risk. Cost-effectiveness analyses will be essential for evaluating the economic viability of the KneE-PAD methodology relative to in-person care.

Enhancing the psychological dimension of the intervention through cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) modules or digital coaching may also yield more pronounced affective benefits. Moreover, adaptive personalization via machine learning algorithms can improve targeting of feedback and progression based on user-specific responses.

User-centered evaluations using validated instruments like the System Usability Scale (SUS), mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ), and UTAUT2 are recommended to assess interaction dynamics. Additionally, coupling sensor-based personalization with asynchronous clinician oversight may provide a robust hybrid care model.

Deploying hybrid trial designs in primary care or community settings can facilitate broader scalability and increase ecological validity, particularly for underserved populations.

7. Conclusions

This pilot randomized controlled trial demonstrates the feasibility, safety, and promising clinical utility of the KneE-PAD platform as a telerehabilitation solution for individuals with knee osteoarthritis. The integration of sensor-based biofeedback led to significant neuromuscular improvements, surpassing conventional physiotherapy in key objective measures such as sEMG amplitude and functional mobility, while maintaining high adherence and safety. Although subjective outcomes improved comparably across groups, the lack of significant between-group differences reflects the known limitations of PROMs in early-phase trials, underscoring the necessity for objective biomechanical indices in evaluating digital interventions.

Importantly, the study addressed critical feasibility questions: the system was usable without technical complications, well-tolerated by participants, and maintained engagement despite the absence of in-person supervision. These findings validate the platform’s readiness for broader deployment and potential scalability in diverse care settings. Furthermore, the capacity for real-time signal processing and remote monitoring highlights KneE-PAD’s alignment with contemporary trends in decentralized, personalized rehabilitation—particularly for populations facing geographic, mobility, or socioeconomic barriers. While limitations such as small sample size, short intervention duration, and deactivated AI-driven posture correction warrant cautious interpretation, the results contribute meaningfully to the growing literature on digital physiotherapy. Future trials should incorporate long-term follow-up, advanced algorithmic modules, formal usability assessments, and integration with psychological support frameworks to maximize both motor and affective rehabilitation outcomes.

Taken together, these findings support the KneE-PAD platform as a viable, scalable, and clinically relevant tool within evolving models of technology-enabled, patient-centered musculoskeletal care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412988/s1, Figure S1. Isometric quadriceps contraction(Initial position); Figure S2. Isometric quadriceps contraction (final position); Figure S3. Heel press (initial position); Figure S4. Heel press (final position); Figure S5. Straight leg raise (initial position); Figure S6. Straight leg raise (final position); Figure S7. Bridge (initial position); Figure S8. Bridge (final position); Figure S9. Seated knee extension (initial position); Figure S10. Seated knee extension (final position); Figure S11. Prone knee flexion (initial position); Figure S12. Prone knee flexion (final position); Figure S13. Sit-to-stand (initial position); Figure S14. Sit-to-stand (final position); Figure S15. mini squat (initial position); Figure S16. mini squat (final position); Figure S17. Hip abduction (initial position); Figure S18. Hip abduction (final position);Figure S19. Hip extension (initial position); Figure S20. Hip extension (final position); Figure S21. Standing knee flexion (initial position); Figure S22. Standing knee flexion (final position); Figure S23. Heel raises (initial position); Figure S24. Heel raises (final position); Figure S25. Step-up (initial position); Figure S26. Step-up (final position); Figure S27. Step-down (initial position); Figure S28. Step-down (final position); Figure S29. Single-leg stance (initial position); Figure S30. Single-leg stance (final position).

Author Contributions

Methodology, T.P. and G.G.; software, P.K. and A.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P.; writing—review and editing, T.P., D.S. and G.P.; supervision, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received financial support from the project “Social and Human-Centered XR – XR-SUN” (European Commission, Horizon Europe, Grant Agreement No. 101092612).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics and Deontology Committee (R.E.D.C.) of the University of West Attica (U.W.A.) (protocol code 61123/27-06-2023 and approval date 27 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s). The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study, including synchronized sEMG and IMU biosignals, is openly accessible on Zenodo at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12112951.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| sEMG | Surface Electromyography |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| WOMAC | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go Test |

| ASES | Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale |

| TSK | Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| UTAUT2 | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| KneE-PAD | Knee Exercise-Postural Assessment Dataset |

| SENIAM | Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles |

Appendix A. Technical Specifications of Equipment

Appendix A.1. Wearable Sensors: Delsys Trigno Avanti

To record both electromyographic and kinematic data during the telerehabilitation protocol, we employed eight Delsys Trigno Avanti wireless wearable sensors, each integrating:

- -

- 1 sEMG channel (surface electromyography), and

- -

- 6 IMU channels (3-axis accelerometer and 3-axis gyroscope).

Technical Specifications of Trigno Avanti:

| Parameter | Value |

| Sensor Dimensions | 27 × 37 × 13 mm |

| Weight | 14 g |

| Battery Life | Up to 8 h |

| sEMG Sampling Rate | 1259.259 Hz |

| IMU Sampling Rate | 148.148 Hz |

| sEMG Signal Range | ±11 mV |

| sEMG Bandwidth | 20–450 Hz |

| Accelerometer Bandwidth | 24–470 Hz |

| Accelerometer Range | ±2 g |

| Gyroscope Bandwidth | 24–360 Hz |

| Gyroscope Range | ±250 deg/s |

| Wireless Communication | Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) |

Signal Synchronization:

All signals were captured and synchronized in real-time using Trigno Discover Software, Version 1.7.0, ensuring precise alignment of sEMG and IMU data streams for each recording window.

Appendix A.2. Sensor Placement—Following SENIAM Guidelines

Sensor placement followed the SENIAM (Surface Electromyography for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles) recommendations to ensure high-quality and reproducible sEMG measurements. Sensors were symmetrically placed on key lower limb muscles:

| Sensor ID | Muscle Group | Body Side |

| 1 | Rectus femoris | Right |

| 2 | Hamstrings | Right |

| 3 | Tibialis anterior | Right |

| 4 | Gastrocnemius | Right |

| 5 | Rectus femoris | Left |

| 6 | Hamstrings | Left |

| 7 | Tibialis anterior | Left |

| 8 | Gastrocnemius | Left |

Axis Orientation of IMUs:

- -

- Z-axis (Roll): forward-backward motion

- -

- X-axis (Pitch): lateral (left–right) motion

- -

- Y-axis (Yaw): vertical movement

Appendix A.3. Auxiliary Sensors

In addition to Trigno Avanti units, participants were equipped with:

- -

- A heart rate monitor

- -

- A muscle oxygenation sensor (to monitor physical exertion)

- -

- A goniometer (to track knee joint angles)

- -

- An RGB camera for visual session recordings (used only for annotation; not included in the KneE-PAD dataset)

Appendix A.4. Signal Recording Format

Recording Duration per Session: ~4.2 s

Export Format: .npy files (converted from proprietary .shpf format)

sEMG Files: Matrices of 8 × 5037 samples

IMU Files: Matrices of 48 × 593 samples (6 IMU channels per sensor × 8 sensors)

Appendix A.5. Signal Preprocessing

High-pass filtering with a 2nd-order Butterworth filter at 50 Hz for sEMG to eliminate motion artifacts and baseline noise.

Amplitudes below 0.3 mV were filtered as low-level noise.

Window segmentation: 4 s windows with overlapping steps (250 ms for squats/extensions, 500 ms for gait).

Z-score normalization applied to enhance input suitability for ML models.

Appendix A.6. Role in Telerehabilitation System

The signals were used to:

- -

- Identify exercise type (squat, leg extension, gait)

- -

- Classify execution as correct or faulty using a Hierarchical Deep Learning (HDL) model combining CNNs and RNNs

- -

- Deliver personalized real-time feedback via visual and audio cues

- -

- Support immersive visualization through realistic avatars and Augmented Reality (AR) environments

Appendix B. Technical Specifications of Equipment (Additional: XSENS Awinda IMUs)

Appendix B.1. Wearable Sensor System: XSENS Awinda IMUs

The telerehabilitation system employed 17 wireless inertial measurement units (IMUs) from the XSENS Awinda series. These sensors were body-mounted using elastic Velcro straps and provided full-body motion capture with the following core specifications:

| Specification | Value/Description |

| Number of Sensors | 17 wireless IMUs, full-body placement |

| Sampling Rate (Update Rate) | Up to 60 Hz for full-body capture |

| Wireless Range | Up to 50 m in open-field conditions |

| Battery Life | Approx. 12 h (for units manufactured after October 2024) |

| Latency | ~30 ms |

| Synchronization Accuracy | ≤10 μs between sensors via Awinda Station |

| Communication Protocol | Awinda radio protocol based on IEEE 802.15.4 ISM 2.4 GHz |

| Synchronization with External Devices | 4 BNC ports (2 input/2 output) for TTL (≤3.3 V) synchronization |

| Connection Capacity | Supports up to 20 IMUs in parallel (up to 32 depending on model) |

Appendix B.2. MTw Awinda Tracker—Technical Specifications

Form Factor & Weight:

- Dimensions: ~47 × 30 × 13 mm

- Weight: ~16 g

Performance Characteristics:

- Internal Sampling Rate: ~1000 Hz (buffered locally)

- Data Buffering: Up to 10 s

- Orientation Accuracy (RMS error):

- ○

- Static Roll/Pitch: ~0.5°

- ○

- Static Heading: ~1.0°

- ○

- Dynamic Roll/Pitch: ~0.75°

- ○

- Dynamic Heading: ~1.5°

Appendix C. Exercise Protocol

The intervention protocol consisted of two experimental groups: Group A (in-person therapeutic exercise) and Group B (telerehabilitation program).

Group A—In-Person Therapeutic Exercise

Participants followed a structured in-person exercise protocol supervised by a physiotherapist twice per week, with each session lasting 45 min over a total intervention period of eight weeks. The program’s structure and progression were adjusted in-person according to patient performance. In addition, participants were instructed to perform a home-based exercise program three times per week. The standardized program included:

- Strengthening exercises for hip and knee muscles using isometric contractions and resistance band training.

- Balance and neuromuscular coordination exercises.

The program was based on international guidelines, including those from the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). It allowed for progression or regression depending on pain or performance, ensuring patient-centered adaptability. and allowed for progression or regression depending on pain or performance, ensuring patient-centered adaptability.

Educational Component

Patients received initial education on the pathophysiology and evidence-based management of knee osteoarthritis, followed by a detailed explanation of the progressive therapeutic exercise plan, aligned with international literature [8]; Educational handouts were also distributed.

Group B—Telerehabilitation Program

Participants in the telerehabilitation group followed an identical structure and content as Group A. However, the key distinction was that all instructions, demonstration of exercises, monitoring, and feedback were delivered remotely through a telehealth platform and dedicated software for sensor data analysis. The physiotherapist used the real-time data provided by the platform to assess performance and adapt the exercise program accordingly during the 45 min sessions. All other intervention parameters, including session duration and frequency, remained consistent with the in-person group.

Appendix D. Exercise Protocol Description

The standardized physiotherapy program included 15 exercises focusing on quadriceps and gluteal muscle strengthening, balance, and proprioception training. Each exercise is illustrated in Figures S1–S30 (initial and final position) and described below with corresponding sets and repetitions.

| Exercise | Description (Brief) | Sets × Repetitions | Progression/Notes |

| 1. Isometric quadriceps contraction | Supine position, pillow under the affected knee; press down, dorsiflex foot. | 3 × 15 | Hold for 10 s in later sessions. |

| 2. Heel press | Supine with knees flexed, heels pressing downward. | 3 × 15 | Hold 10 s for progression. |

| 3. Straight leg raise | Supine; tighten quadriceps, lift leg 40°. | 3 × 15 | Add ankle weight later. |

| 4. Bridge | Supine, knees bent, lift pelvis. | 2 × 8 | Progress to single-leg bridge. |

| 5. Prone knee flexion | Prone; flex knee against gravity. | 3 × 15 | Add ankle weight. |

| 6. Seated knee extension | Sitting on chair, extend affected leg. | 3 × 15 | Use resistance band. |

| 7. Sit-to-stand | From chair, rise to stand and sit back. | 2 × 8 | Avoid arm support. |

| 8. Mini squat | Standing, perform half-squat. | 2 × 8 | Add resistance band. |

| 9. Hip abduction | Standing, lift leg laterally. | 2 × 8 | Add resistance band. |

| 10. Hip extension | Standing, move leg backward. | 2 × 8 | Add resistance band. |

| 11. Standing knee flexion | Standing, bend knee backwards. | 2 × 8 | Add resistance band. |

| 12. Heel raises | Standing, rise on toes. | 2 × 8 | Single-leg variation. |

| 13. Step-up | Step onto a stair and back down. | 2 × 8 | Hold light weights. |

| 14. Step-down | Descend with healthy leg; load on affected limb. | 2 × 8 | Add hand-held weights. |

| 15. Single-leg stance | Stand on affected leg for 10 s. | 3 reps | Progress to 30 s + arm movement. |

Figure A1.

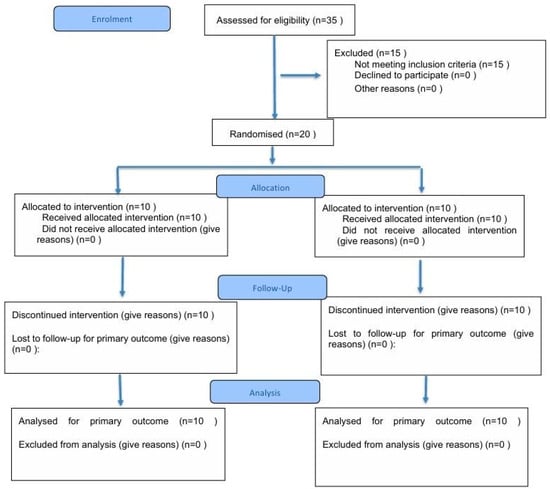

CONSORT 2025 Flow Diagram.

Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of a randomised trial of two groups (that is, enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis).

Table A1.

Consort 2025 check list item description.

Table A1.

Consort 2025 check list item description.

| Section/Topic | No | CONSORT 2025 Checklist Item Description | Reported on Page No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | |||

| Title and structured abstract | 1a | Identification as a randomized controlled trial | Page 2 (Abstract, Section 2.1) |

| 1b | Structured summary of the trial design, methods, results, and conclusions | Page 2 (Abstract) | |

| Open science | |||

| Trial registration | 2 | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06416332, registered on 27 June 2023 | Page 2, Section 2.1 |

| Protocol and statistical analysis plan | 3 | Described in Section 2.7; full protocol available upon request to corresponding author | Page 15–18 |

| Data sharing | 4 | De-identified dataset and code available at Zenodo | Page 18, Data Availability Statement |

| Funding and conflicts of interest | 5a | Funded by Horizon Europe (Grant No. 101092612, XR-SUN Project); no funder involvement in design, analysis, or reporting | Page 34 |

| 5b | Authors declare no conflicts of interest | Page 34 | |

| Introduction | |||

| Background and rationale | 6 | Background on OA and telerehabilitation rationale | Page 3–6 |

| Objectives | 7 | To evaluate feasibility, safety, and preliminary effectiveness of KneE-PAD telerehabilitation vs conventional physiotherapy | Page 6 |

| Methods | |||

| Patient and public involvement | 8 | Participants not directly involved in design; feedback collected during pilot testing for usability | Page 14 |

| Trial design | 9 | Two-arm, parallel-group, single-blind pilot RCT | Page 8 |

| Changes to trial protocol | 10 | None after trial commencement | Page 8 |

| Trial setting | 11 | University of West Attica, Athens, Greece | Page 9 |

| Eligibility criteria | 12a | Inclusion/exclusion criteria detailed | Page 9 |

| 12b | All interventions delivered by licensed physiotherapists | Page 9–10 | |

| Intervention and comparator | 13 | Described in Section 2.4; identical exercise protocol across groups (Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D) | Page 10–12 |

| Outcomes | 14 | Primary: WOMAC, Strength, sEMG; Secondary: TUG, ASES, TSK, HADS; pre-specified | Page 12–14 |

| Harms | 15 | Monitored throughout; no adverse events reported | Page 14 |

| Sample size | 16a | A priori power analysis for future RCT (n=42 estimated) | Page 18 |

| 16b | No interim analyses performed | Page 18 | |

| Randomisation – Sequence generation | 17a | Computer-generated random numbers; allocation ratio 1:1 | Page 9 |

| 17b | Simple randomisation; no stratification | Page 9 | |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 18 | Sealed opaque envelopes handled by independent researcher | Page 9 |

| Implementation | 19 | Allocation by independent researcher; blinded outcome assessors | Page 9 |

| Blinding | 20a | Outcome assessors blinded; participants unblinded due to behavioral nature | Page 9 |

| 20b | Blinding achieved through assessor independence | Page 9 | |

| Statistical methods | 21a | Parametric/non-parametric comparisons; t-tests, Mann–Whitney, permutation tests | Page 15–18 |

| 21b | All randomized participants analyzed (intention-to-treat) | Page 15 | |

| 21c | No missing data; complete case analysis | Page 15 | |

| 21d | Exploratory subgroup analysis not pre-specified | Page 18 | |

| Results | |||

| Participant flow (with diagram) | 22a | CONSORT 2025 flow diagram (Assessed: 35, Randomized: 20, Allocated: 10/10, Analyzed: 10/10) | Page 33 |

| 22b | No exclusions post-randomization | Page 33 | |

| Recruitment | 23a | Recruitment June–September 2023; follow-up 8 weeks | Page 8 |

| 23b | Trial completed as planned; no early termination | Page 8 | |

| Intervention and comparator delivery | 24a | Delivered per protocol (supervised sessions) | Page 10–12 |

| 24b | No concomitant care differences | Page 10 | |

| Baseline data | 25 | Table 1 and Table 2 | Page 11 |

| Numbers analysed, outcomes and estimation | 26 | Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, full descriptive and inferential stats with CI and effect sizes | Page 22–27 |

| Harms | 27 | None observed | Page 14 |

| Ancillary analyses | 28 | Exploratory feasibility indicators; effect size estimation for future trial | Page 18 |

| Discussion | |||

| Interpretation | 29 | Interpretation consistent with results; balanced clinical and technical outcomes | Page 28–31 |

| Limitations | 30 | Small sample size, short duration, limited psychological module | Page 30–31 |

References

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.; Smith, E.; Hoy, D.; Nolte, S.; Ackerman, I.; Fransen, M.; Bridgett, L.; Williams, S.; Guillemin, F.; Hill, C.L.; et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from 79 the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel-Pelletier, J.; Barr, A.J.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Conaghan, P.G.; Cooper, C.; Goldring, M.B.; Goldring, S.R.; Jones, G.; Teichtahl, A.J.; Pelletier, J.-P. Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Gupte, C.; Akhtar, K.; Smith, P.; Cobb, J. The Global Economic Cost of Osteoarthritis: How the UK Compares. Arthritis 2012, 2012, 698709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.; Hagen, K.B.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Andreassen, O.; Christensen, P.; Conaghan, P.G.; Doherty, M.; Geenen, R.; Hammond, A.; Kjeken, I.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, M.; McConnell, S.; Harmer, A.R.; Van der Esch, M.; Simic, M.; Bennell, K.L. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: A Cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L.; Taki, J.; Desjardins, B.; Thevenot, O.; Fransen, M.; Wells, G.A.; Imoto, A.M.; Toupin-April, K.; Westby, M.; Gallardo, I.C.Á.; et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part one: Introduction, and mind-body exercise programs. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, K.; McLean, S.; Moffett, J.A.K.; Gardiner, E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisters, M.F.; Veenhof, C.; Schellevis, F.G.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Dekker, J.; De Bakker, D.H. Exercise adherence improving long-term patient outcome in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.-H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.-Q.; Wang, L.; Song, K.-P.; He, C.-Q. Effect of internet-based rehabilitation programs on improvement of pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, W.; Wang, J.-Y.; Ji, B.; Li, L.-J.; Xiang, H. Effectiveness of different telerehabilitation strategies on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.L.; Campbell, P.K.; Egerton, T.; Metcalf, B.; Kasza, J.; Forbes, A.; Bills, C.; Gale, J.; Harris, A.; Kolt, G.S.; et al. Telephone coaching to enhance a home-based Physical Activity Program for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 69, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.; Folgado, D.; Nunes, F.; Almeida, J.; Sousa, I. Using inertial sensors to evaluate exercise correctness in electromyography-based home rehabilitation systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Istanbul, Turkey, 26–28 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Vakanski, A.; Xian, M. A deep learning framework for assessing physical rehabilitation exercises. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 28, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasnesis, P.; Plavoukou, T.; Syropoulou, A.C.; Georgoudis, G.; Toumanidis, L. KneE-PAD [Data set]. Zenodo 2024, 12112951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, J.; Cao, R.; Du, X.; Mo, S. Finerehab: A multi-modality and multi-task dataset for rehabilitation analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 3184–3193. [Google Scholar]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

- Delsys Avanti. Trigno Avanti Sensor Superior emg + imu Technology. 2023. Available online: https://delsys.com/trigno-avanti/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Sarri, F.; Kasnesis, P.; Symeonidis, S.; Paraskevopoulos, I.T.; Diplaris, S.; Posteraro, F.; Mania, K. Embodied augmented reality for lower limb rehabilitation. Creat. Lively Interact. Popul. Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, G.; Stasi, S.; Oikonomou, L.; Roussou, I.; Papageorgiou, E.; Chronopoulos, E.; Korres, N.; Bellamy, N. Clinimetric properties of WOMAC index in Greek knee osteoarthritis patients: Comparisons with both self-reported and physical performance measures. Rheumatol. Int. 2015, 5, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, T.; Walker, B.; Phillips, J.K.; Fejer, R.; Beck, R. Hand-held dynamometry correlation with the gold standard isokinetic dynamometry: A systematic review. PM&R 2013, 3, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentiplay, B.F.; Perraton, L.G.; Bower, K.J.; Adair, B.; Pua, Y.H.; Williams, G.P.; McGaw, R.; Clark, R.A. Assessment of Lower Limb Muscle Strength and Power Using Hand-Held and Fixed Dynamometry: A Reliability and Validity Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.; Chastain, R.L.; Ung, E.; Shoor, S.; Holman, H.R. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989, 32, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakou, A.; Fijalkowska, M.; Lazari, E.; Georgoudis, G. Translation, Validation, and Reliability of the Greek Version of the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale. Eur. J. Physiother. 2023, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgoudis, G.; Papathanasiou, G.; Spiropoulos, P.; Katsoulakis, K. Physiotherapy assessment in painful musculoskeletal conditions: The validation of the Greek version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (pilot study). In Proceedings of the International Forum on Pain Medicine, Sofia, Bulgaria, 5–8 May 2005; European Federation of IASP Chapters; World Institute of Pain: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Georgoudis, G.; Raptis, K.; Koutserimpas, C. Cognitive Assessment of Musculoskeletal Pain: Validity and Reliability of the Greek Version of the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in Patients Suffering from Chronic Low Back Pain. Maedica 2022, 17, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Georgoudis, G.; Oldham, J.A. Anxiety and Depression as Confounding Factors in Cross-cultural Pain Research Studies: Validity and reliability of a Greek version of the HAD scale. Physiotherapy 2001, 87, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, I.; Douzenis, A.; Kalkavoura, C.; Christodoulou, C.; Michalopoulou, P.; Kalemi, G.; Fineti, K.; Patapis, P.; Protopapas, K.; Lykouras, L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, M.A.; Galea, O.A.; O’Leary, S.P.; Hill, A.J.; Russell, T.G. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piqueras, M.; Marco, E.; Coll, M.; Escalada, F.; Ballester, A.; Cinca, C.; Belmonte, R.; Muniesa, J.M. Effectiveness of an interactive virtual telerehabilitation system in patients after total knee arthoplasty: A randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 45, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubach, F.; Ravaud, P.; Baron, G.; Falissard, B.; Logeart, I.; Bellamy, N.; Bombardier, C.; Felson, D.; Hochberg, M.; van der Heijde, D.; et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: The minimal clinically important improvement. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pham, T.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Lassere, M.; Altman, R.D.; Anderson, J.J.; Bellamy, N.; Hochberg, M.; Simon, L.; Strand, V.; Woodworth, T.; et al. OMERACT-OARSI Outcome variables for osteoarthritis clinical trials: The OMERACT-OARSI set of responder criteria. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Staehli, S.; Glatthorn, J.F.; Casartelli, N.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Maffiuletti, Test–retest reliability of quadriceps muscle function outcomes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 1058–1065, ISSN 1050 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiengkaew, V.; Jitaree, K.; Chaiyawat, P. Minimal detectable changes of the berg balance scale, fugl-meyer assessment scale, timed "up & go" test, gait speeds, and 2-minute walk test in individuals with chronic stroke with different degrees of ankle plantarflexor tone. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, T.J. Measures of self-efficacy: Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES), Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale-8 Item (ASES-8), Children’s Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (CASE), Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale (CDSES), Parent’s Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (PASE), and Rheumatoid Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (RASE). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. S11), S473–S485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Rocca, B.; Foti, C.; Ferrante, S. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important changes for the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia after lumbar fusion during cognitive behavioral rehabilitation. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhan, M.A.; Frey, M.; Büchi, S.; Schünemann, H.J. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lemay, K.R.; Tulloch, H.E.; Pipe, A.L.; Reed, J.L. Establishing the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2019, 39, E6–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.; Ramos, E.; Branco, J. Osteoarthritis. Acta Med. Port. 2015, 28, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennell, K.; Nelligan, R.K.; Schwartz, S.; Kasza, J.; Kimp, A.; Crofts, S.J.; Hinman, R.S. Behavior change text messages for home exercise adherence in knee osteoarthritis: Randomized trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Severo, M.; Barros, H.; Branco, J.; Santos, R.A.; Ramos, E. The effect of depressive symptoms on the association between radiographic osteoarthritis and knee pain: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Or, C.K.; Chen, J. Effects of technology-supported exercise programs on the knee pain, physical function, and quality of life of individuals with knee osteoarthritis and/or chronic knee pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Med Informatics Assoc. 2021, 28, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perera, C.K.; Hussain, Z.; Khant, M.; Gopalai, A.A. A motion capture dataset on human sitting to walking transitions. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Peleteiro, B.; Araújo, J.; Branco, J.; Santos, R.A.; Ramos, E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: A systematic review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Osteoarthritis: Care and Management. NICE Guideline [NG226]. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226 (accessed on 19 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).