Abstract

Professional truck drivers spend prolonged periods seated, often leading to discomfort and fatigue. Conventional seats are typically designed for average body dimensions rather than individual morphology, which limits their ability to provide optimal support. This study investigates whether 3D-printed personalized seat inserts, developed through an integrated digital workflow, can improve pressure distribution and perceived comfort compared with a standard truck seat. Sixteen participants completed the full workflow from body-data acquisition to comfort evaluation in a static truck buck. Unlike existing personalization approaches, the workflow explicitly incorporates occupational context and task-related posture constraints as design inputs, and validates a complete, reproducible end-to-end process combining vacuum cushion molding, 3D scanning, computational modelling, and large-format additive manufacturing. Pressure mapping and subjective comfort ratings were collected for both baseline and personalized conditions. The personalized inserts reduced mean pressure by 39% and peak pressure by 18%, while increasing contact area by 15%. Subjective comfort scores improved significantly across all regions, particularly in the buttock area, with participants describing firmer yet more stable support. Beyond these ergonomic outcomes, the study contributes a context-driven personalization method and demonstrates that geometric adaptation informed by real use conditions yields quantifiable comfort benefits in an occupational transport setting.

1. Introduction

Professional truck drivers spend most of their working hours seated, often for more than eight hours per day [1]. Prolonged static sitting, combined with restricted movement and exposure to whole-body vibration, leads to discomfort and fatigue [2]. Seating comfort directly influences alertness, task performance, and perceived well-being during long-duration driving [3]. Understanding, measuring, and improving seating comfort is therefore not a matter of luxury but a central ergonomic requirement in occupational transport design.

Despite advances in vehicle seat technology, discomfort among professional drivers remains common. Many commercial seats follow a “one-size-fits-most” design logic derived from certain anthropometric databases [4]. However, drivers differ substantially in body dimensions, body composition, posture preferences, and support needs [5]. When seat geometry does not match an individual’s morphology, it can produce uneven pressure distribution, localized stress points, and postural instability [6]. Over time, such mismatches accumulate, resulting in discomfort and fatigue during extended driving sessions.

Seating comfort is a multidimensional construct that combines physiological, physical, and psychological aspects [7,8]. Among these, pressure distribution is one of the most direct physical determinants of perceived comfort, as it reflects how body loads are supported by the seat [6,9,10]. Pressure distribution can be quantified through several measurable features: mean pressure (MP), representing overall load intensity; peak pressure (PP), capturing local stress concentrations; and contact area (CA), indicating how extensively the body is supported. Additional descriptors such as standard deviation (SD), variance (Var), and seat pressure distribution percentage (SPD%) describe the uniformity and balance of interface loads [11]. Together, these metrics provide an objective means to evaluate seat performance. As summarized in Table 1, automotive seating studies consistently show that lower MP and PP and a larger CA are associated with higher comfort, while lower SD, Var, and SPD% indicate more even pressure distribution and improved postural stability. Overall, a well-distributed pressure profile remains a reliable indicator of seating quality and perceived comfort, especially for the seat pan, which may bear up to 90% of the total body weight [12].

Table 1.

Seating comfort studies using standardized pressure-distribution metrics (MP = Mean Pressure, PP = Peak Pressure, CA = Contact Area, SD = Standard Deviation, Var = Variance, and SPD% = seat pressure distribution percentage).

Beyond conventional pressure-distribution studies, several related fields have explored digital or morphology-based approaches to improving seated support. Research in rehabilitation and wheelchair seating has shown that individualized contouring can reduce pressure hotspots and improve pelvic stability [17,18], while computational modelling studies demonstrated that human morphology and internal tissue mechanics can predict high-pressure zones and guide geometry adaptation [19]. Complementing these findings, recent additive-manufacturing research has introduced lattice and functionally graded structures that enable tunable stiffness and improved load distribution compared with uniform foams [20,21]. Together, these studies highlight the importance of matching seat-support geometry and stiffness to individual morphology in order to achieve more favorable pressure distributions.

Integrating individual morphology into product design requires a smooth and coherent workflow. Personalized orthotic workflows have established the value of integrating 3D scanning, parametric modelling, and additive manufacturing to create patient-specific support surfaces with improved fit and biomechanical performance [22,23]. Similarly, computational approaches to personalized seating have demonstrated how digital human body models can predict seat–body interaction and generate optimized support surfaces for specific postures (e.g., Leimer et al. [24]), and complete end-to-end workflows have been developed for translating morphology into manufacturable geometry (e.g., Hale et al. [22]). Minnoye et al. [25] linked anthropometric inputs with parametric modelling and fabrication parameters, enabling a reproducible process for personalized seating design. However, despite these advances, most existing developments remain concentrated in medical or non-dynamic anthropometry applications, with limited translation to occupational driving environments where constrained posture, long-duration sitting, and vibration impose unique ergonomic demands.

Existing digital workflows have rarely been applied or validated in occupational transport settings, where long-term sitting and task-specific postures impose distinct ergonomic demands. This study addresses that gap by applying personalized product design to truck-driver seating comfort. In detail, it investigates whether 3D-printed, geometry-personalized seat inserts can be produced and whether they can improve pressure distribution and perceived comfort compared with a standard truck seat. Accordingly, the research questions are defined as follows: (1) How can 3D scanning, computational design, and additive manufacturing be used to design personalized seat inserts for truck drivers? (2) How does a personalized insert influence pressure distribution and perceived comfort compared with a standard seat? By addressing these scientific gaps, this study contributes a context-driven personalization workflow for truck-driver seating and provides empirical evidence that personalized geometry improves pressure distribution and perceived comfort compared with a standard seat.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Approach

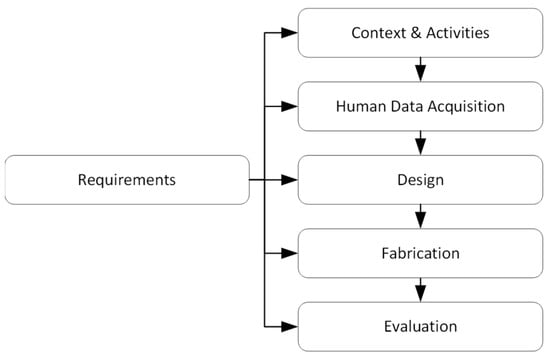

Building on the personalized product-design framework, the study followed five sequential and interrelated phases, as shown in Figure 1. In this workflow, the requirements, comfort during driving, inform every phase, ensuring that personalization is grounded in the functional needs of truck driving and the constraints of the cabin environment. The first phase, Context and Activities, defined the experimental setting, intended use scenario, and relevant driver tasks that shape seated posture and support demands. The second phase, Human Data Acquisition, captured each participant’s anthropometric and postural characteristics using vacuum-cushion molding and 3D scanning to obtain accurate body–seat interface geometries in a natural driving posture. The third phase, Design, translated these digital anthropometric models into personalized seat-insert geometries through computational modelling. The fourth phase, Fabrication, produced the inserts using large-format additive manufacturing. Finally, the Evaluation phase assessed the personalized inserts in terms of objective pressure distribution and subjective comfort relative to the baseline truck seat.

Figure 1.

A schematic overview of the approach.

2.2. Context & Activities

This phase established the experimental context and defined the key user activities to be simulated. All work was carried out in collaboration with CoverWorks Health (Katwijk, The Netherlands), where a stationary truck-cabin buck was developed to reproduce a realistic driving scenario (Figure 2). The buck comprised a full-scale driver’s seat, steering wheel, and pedal assembly mounted on a rigid platform that replicated the interior geometry of a long-haul truck. This setup ensured consistent seat positions, spatial layout, and view angles across all participants while providing a controlled and repeatable environment for data collection.

Figure 2.

Participant sits on the top of the vacuum bag in the stationary truck-cabin buck.

The selected seat was a commercial heavy-duty truck driver’s seat commonly used in European vehicles. It included standard mechanical adjustments for height, fore–aft position, and backrest recline, but no active suspension or lumbar actuation. The seat frame and base cushion served as the structural reference for integrating the personalized inserts in later phases.

This contextualization phase represents a key methodological extension beyond previous personalization frameworks. Rather than beginning with geometry alone, the present workflow anchors personalization in the realistic occupational context, in this case truck driving, considering seat layout, driver posture, and task constraints as integral design inputs. By defining use conditions and user activities at the outset, the workflow ensures that subsequent anthropometric modelling and fabrication steps address functional comfort in context, rather than purely geometric fit.

2.3. Human Data Collection

2.3.1. Participants

A priori power analysis using G*Power (v3.1.9.7) indicated that a minimum of 16 participants was required for a within-subject, one-tailed design to achieve a statistical power of 0.9 in detecting large effects (0.8) between the baseline and the new seat insert design. Seventeen volunteers (11 male, 6 female) were therefore recruited, including one additional participant to account for potential dropouts. Participant ages ranged from 24 to 60 years (M = 43.5, SD = 10.2). All participants had at least five years of driving experience and reported no acute musculoskeletal discomfort during the week of testing. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

2.3.2. Anthropometric Data Collection

To capture each participant’s individual body–seat interface, vacuum bags (McLean REHAtechnik GmbH, Duderstadt, Germany, E 1 6 100 = 45R, E 1 6 100 = 45S, Green parts in Figure 2) were positioned between the seat and the participant to obtain a negative imprint (mould) of the back, buttock, and thigh contours. Participants were seated in a neutral driving posture within the simulator for approximately five minutes while the cushion conformed to their body shape. The mould was then fixed under vacuum pressure to preserve the impression, providing a physical record of each participant’s seat-contact geometry. Each mould was digitized using a structured-light scanner (Creality 3D CR-Scan Ferret SE [26]) to generate a 3D surface model with a point-distance resolution of approximately 0.16 mm.

2.4. Computational Design

The digitized seat-contact surfaces were processed in Rhinoceros 3D (v8.0) with Grasshopper in a semi-automatic workflow that removed artefacts, smoothed local irregularities, and defined the insert boundaries. As a first step, the raw scans of the truck seat and the vacuum-cushion mould were spatially aligned within a shared coordinate system. Each mesh was then reconstructed into a smooth NURBS surface, enabling controlled curvature editing while preserving the key anatomical and seat-frame contours captured during scanning. Computational design tools were subsequently applied to adjust local curvature, ensuring both functional support and manufacturing feasibility [27]. Parametric curvature refinements removed sharp transitions and undercuts, while surface-offset operations established the final insert thickness. The in-between volume defined by the reconstructed seat and mould surfaces was extracted parametrically and served as the basis for generating the personalized insert geometry.

Boundary trimming followed the scanned seat-pan geometry to ensure that each insert aligned precisely with the commercial truck seat and remained compatible with its adjustment mechanisms. During iterative development, each design was inspected in PrusaSlicer [v2.9.3, prusa3d.com, accessed on 4 December 2025] to detect unsupported regions, overhang behavior, and wall-thickness consistency. Minor geometric adjustments were performed as needed to achieve clean toolpaths suitable for large-format pellet extrusion.

2.5. Fabrication

Final CAD models were exported as STL files and fabricated with fused deposition modelling (FDM). The hardware, material, and process settings are summarized in Table 2. A thermoplastic elastomer (TPE TF40QD-LCNT [28]) material was used on a WASP 3MT HDP printer, a large-format 3D printer with a build volume of 1000 mm in diameter and 1000 mm in height, capable of printing directly from plastic pellets [29]. The inserts were printed using a 2 mm nozzle at a nozzle temperature of 200 °C. Based on prior company experience and iterative prototype testing, the backrest component was printed with a 13% infill density, while the seat-pan component utilized an 18% infill to provide additional stiffness and support. Besides, the first five layers were printed as single walls to ensure structural continuity. Printing time per insert ranged from 10 to 14 h, depending on the geometry and size of the inserts. After fabrication, the printed parts were mounted onto the seat pan using upholstery made from AirMesh fabric (Changshu Dashijia Textiles, Changshu City, China) to provide a breathable interface.

Table 2.

3D printer, material, and process settings used to fabricate the seat inserts.

2.6. Evaluation

2.6.1. Experiment Setup

All comfort evaluations were performed in the stationary truck-cabin simulator. Seat pan pressure was recorded using a 48 × 48 sensor pressure mat (XSENSOR LX100:48.48.02, XSENSOR Technology Corporation, Calgary, AB, Canada) covering the seat pan. Data were sampled at 10 Hz using the provided software suite. Environmental conditions were maintained at 21 ± 1 °C air temperature and 50 ± 5% relative humidity, with normal indoor lighting and ambient noise levels to minimize distraction.

2.6.2. Procedure

Each participant completed two consecutive sitting sessions: (1) a baseline condition using the original truck seat without an insert, and (2) a personalized condition with the participant’s 3D-printed insert installed. Each session lasted approximately 20 min. Participants were instructed to maintain a natural driving posture and were free to make seat adjustments as they would in real use. Pressure data were recorded at the end of each session under static conditions for subsequent analysis.

After each session, participants completed a 10-point Likert-scale comfort questionnaire, and a simplified Local Postural Discomfort (LPD) questionnaire [30]. Short semi-structured interviews were conducted to capture qualitative impressions of support, stability and thermal perception.

2.6.3. Data Analysis

Objective comfort measures were derived from the pressure-mapping data and included mean pressure (MP), peak pressure (PP) and contact area (CA). These parameters were computed using the XSENSOR X3 Pro analysis tools (v7.0) based on the average of the captured frames.

Subjective comfort ratings were analyzed using the same procedure. A Shapiro–Wilk test was performed on the acquired data. As the distribution was not normal, differences between baseline and personalized conditions were assessed using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, implemented in a self-developed Python program (v3.13.5). Qualitative interview responses were transcribed and analyzed to highlight perceived differences.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of the Participants

Seventeen Dutch participants (11 males, 6 females) were initially recruited for the study. One male participant withdrew before completion, resulting in 16 valid data sets used for analysis. As summarized in Table 3, participant ages ranged from 24 to 60 years, covering both younger and older adult groups commonly found in the logistics workforce. Male participants were generally taller and heavier, with greater seated height and leg length, whereas female participants exhibited slightly larger mean hip widths and greater variability in lower-body dimensions, particularly in buttock–knee depth.

Table 3.

Participant demographics by sex.

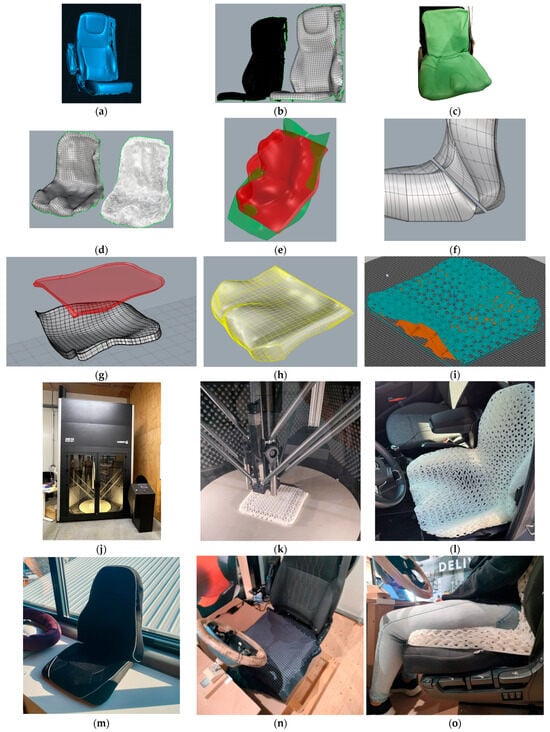

3.2. Seat-Insert Design

All sixteen personalized seat inserts were successfully generated and fabricated following the workflow described in Section 2. Figure 3 illustrates the outcomes of each step in the design and manufacturing workflow for the personalized seat inserts. The reference truck seat was first scanned (a), and its surface geometry was reconstructed (b). Each participant’s vacuum-molded form was then digitized (c) and converted into a continuous surface (d). The personalized insert geometry was generated between the reconstructed mold and seat surfaces (e) and subsequently segmented into printable components (f), including the backrest (g) and cushion (h). The printing process was prepared and visualized in PrusaSlicer (i) and fabricated using a WASP large-format FDM printer (j,k) [WASP S.r.l., Massa, Lombarda, Italy]. The assembled insert was installed on a reference seat (l), and the final upholstery-applied version is shown in (m). During the experiment, pressure profiles were captured for the original truck seat without an insert (n) and for the seat with the insert installed. Figure 3o shows a participant sitting on the insert; the upholstery was removed for improved visualization of the geometry.

Figure 3.

Design and fabrication workflow of the personalized seat inserts. (a) 3D scan of the truck seat; (b) Reconstructed surface of the truck seat; (c) 3D scan of the vacuum mould; (d) Reconstructed surface of the mould; (e) Insert generated between mould and seat surfaces; (f) Split inserts as backrest and cushion for 3D printing; (g) Backrest of the insert; (h) Cushion of the insert; (i) PrusaSlicer [v2.9.3] preview of the 3D-print paths of the backrest; (j) WASP printer; (k) Printing process; (l) Printed insert on a seat before upholstery; (m) Finished insert with upholstery; (n) Pressure profile acquisition (seat without insert); (o) User sits on insert (upholstery removed).

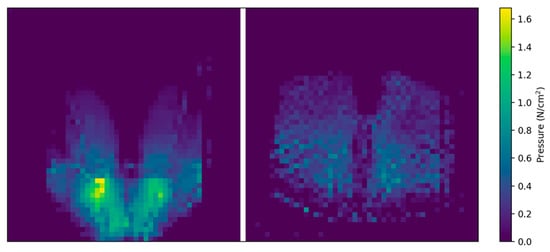

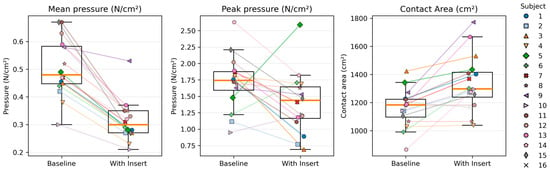

3.3. Pressure-Distribution Analysis

Objective seat-interface pressure data were collected for all 16 participants in both the baseline (regular seat) and personalized-insert conditions. Figure 4 shows examples of pressure maps from one participant: the left panel corresponds to the baseline condition, and the right panel to the personalized-insert condition. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the three-pressure metrics across participants. Each box indicates the median and interquartile range, while the colored dots represent individual participant values connected across conditions. The figure highlights a consistent downward shift in both mean pressure (MP) and peak pressure (PP) with the personalized inserts, accompanied by an increase in contact area (CA), suggesting a more even load transfer and improved pressure dispersion.

Figure 4.

Representative pressure maps from one participant. The left panel shows the baseline (regular-seat) condition and the right panel the personalized-insert condition. The color scale represents seat-interface pressure (N/cm2).

Figure 5.

Comparison of seat-pressure metrics between baseline and personalized-insert conditions across 16 participants. Each box indicates the median and interquartile range, while colored markers represent individual participants connected across conditions.

Table 4 summarises the results of the pressure-mapping analysis. The personalised inserts produced a 39% reduction in MP, an 18% reduction in PP, and a 15% increase in CA compared with the baseline seat. All differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05), confirming the beneficial effect of the inserts on pressure distribution and seated comfort potential.

Table 4.

Results from the pressure-mapping analysis (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

3.4. Subjective Comfort Ratings

Subjective comfort was evaluated immediately after each sitting condition using a 10-point scale (1 = no comfort, 10 = very comfortable). Participants provided ratings for overall comfort, seat cushion, backrest, thigh support, and buttock comfort. Table 5 summarizes the mean comfort ratings for the baseline and personalized-insert conditions. Across all regions, comfort scores improved significantly (p < 0.05). Overall comfort increased by +1.9 points. Region-wise, the largest increases were observed for the buttock (+2.4 points), followed by the thigh (+1.7) and the back (+0.9).

Table 5.

Mean comfort ratings (1–10 scale) for baseline and personalized conditions (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

3.5. Qualitative Feedback

Qualitative insights were obtained from short semi-structured interviews conducted immediately after each test session. Participants were invited to describe their comfort experience, perceived differences between the two seat conditions, and any sensations of support, stability, or thermal perception. Their comments revealed three recurring themes.

First, support and pressure distribution. Most participants described the personalized insert as providing firmer yet more stable support, particularly under the buttocks and thighs. Several reported a more even pressure distribution and less localized discomfort or numbness during the 20-min sitting period.

Second, postural control and stability. Many participants noted that the insert reduced the tendency to slide forward and helped them maintain a neutral posture with less effort. These perceptions of improved stability aligned with the reduced peak-pressure and increased contact-area measurements.

Third, surface feel and thermal perception. A few participants mentioned that the insert felt slightly warmer than the baseline seat, although none associated this with discomfort. Several participants also noted that the surface felt smoother when the pressure-mapping mat was placed on top.

Overall, participants perceived the personalized insert as more supportive, stable, and comfortable than the baseline truck seat. These qualitative impressions reinforce the quantitative trends observed in the pressure-mapping and comfort-rating analyses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview and Main Findings

This study aimed to address two research questions: (1) How can 3D scanning, computational design, and additive manufacturing be used to design personalized seat inserts for truck drivers? (2) How does a personalized insert influence pressure distribution and perceived comfort compared with a standard seat? Regarding the first question, the study demonstrated a reproducible end-to-end workflow consisting of five sequential phases: Context & Activities, Human Data Acquisition, Design, Fabrication, and Evaluation as shown in Figure 1. Requirements informed each phase, ensuring that the workflow remained grounded in real driving posture, cabin geometry, and task constraints. The integration of vacuum molding, 3D scanning, computational design, and large-format additive manufacturing proved technically feasible, and the resulting inserts were successfully integrated into an existing truck seat without affecting its adjustability.

For research question 2, both objective and subjective results indicated significant benefits of personalization. Interface pressure analysis revealed a 39% reduction in mean pressure (MP) and an 18% reduction in peak pressure (PP), alongside a 15% increase in contact area (CA). Correspondingly, all comfort ratings improved significantly (p < 0.05), with the largest gains observed in the buttock region (+2.4 points). Participants described firmer yet more stable support and reduced local discomfort. Together, these findings confirm that personalized inserts enhance comfort and pressure distribution, and that the proposed workflow offers a viable pathway for implementing personalization in occupational seating.

4.2. Pressure Distribution

The inserts effectively altered the physical interaction between body and seat. Lower MP and PP indicate that loads were spread across a wider contact surface, reducing localized stress beneath the ischial tuberosities. The larger CA supports this interpretation, suggesting improved conformity between the seat pan and body contours.

These findings are consistent with prior comfort studies that have identified a more uniform pressure distribution as a key determinant of perceived support quality [6,9]. Kilincsoy et al. [12] and Halder et al. similarly reported that even small reductions in local pressure peaks can lead to notable improvements in comfort ratings. The magnitude of improvement observed in the present study—up to a 40% reduction in MP—is greater than typically achieved through material changes alone, highlighting the importance of geometric adaptation rather than solely modifying foam or damping properties.

Although this experiment was static, the reduction in concentrated load areas suggests that, under dynamic driving conditions, the inserts may mitigate micro-movements and muscular tension required to maintain posture, thereby delaying the onset of discomfort.

4.3. Subjective Comfort

The subjective ratings closely mirrored the pressure-mapping results. Participants consistently rated the personalized inserts as more comfortable, with significant improvements across all measured regions. The greatest gains were observed for the buttock area, which also exhibited the largest reductions in interface pressure. This correspondence reinforces the established relationship between pressure distribution and perceived comfort [6,9].

Interestingly, several participants described the inserts as firmer yet more stable. This suggests that comfort improvements are derived primarily from geometric conformity rather than material compliance. Similar observations were reported by Vink and Hallbeck [7], who noted that comfort involves both physical and psychological factors such as predictability, balance, and perceived fit. In this context, firmness may have contributed to a stronger sense of stability, allowing participants to maintain an upright and balanced posture with less effort.

4.4. Qualitative Interviews

The interviews provided complementary insights consistent with the quantitative findings. Three themes emerged: support stability, pressure relief, and thermal perception. Most participants reported improved lateral and vertical stability, reduced sliding, and easier posture maintenance, echoing Porter et al. [5], who emphasized the importance of stable support for driver comfort and perceived safety.

Participants also reported more even pressure under the buttocks and thighs, consistent with the measured pressure redistribution. A few participants mentioned a slightly warmer seat surface. Future work should therefore examine the thermal performance of the upholstery and its influence on humidity accumulation and airflow.

4.5. Personalized Product Design and Fabrication

Beyond the ergonomic outcomes, this study demonstrates the feasibility of integrating 3D scanning, computational design, and additive manufacturing into a coherent workflow for personalized seating insert design [31]. Each insert was designed, printed, and installed using commercially available tools, with fabrication times ranging from 10 to 14 h per participant. Comparable levels of efficiency and workflow structure have been reported in digital orthotic fabrication pipelines, where 3D scanning and additive manufacturing enable individualized support surfaces with reasonable turnaround times [22]. Research on customized wheelchair seating similarly highlights the potential of additive manufacturing for low-volume, user-specific seating components [32].

From a design perspective, the workflow translates human morphology directly into manufacturable geometry, thereby reducing reliance on empirical fitting or manual adjustments. This mirrors the processes used in bespoke orthosis design that combine 3D body scanning with parametric CAD to achieve reproducible, user-specific geometries [22]. The inserts maintained full compatibility with the existing seat structure and adjustment mechanisms, demonstrating how individualization can be embedded within conventional seat architectures without extensive redesign.

A key advancement of the proposed workflow is the explicit inclusion of contextual and activity-based factors as the starting point of personalization. Unlike previous approaches such as Minnoye et al. [25], which derive support surfaces primarily from morphology, the present workflow uses the driver’s use scenario, task constraints, and cabin layout to establish the target posture and ergonomic configuration. By grounding personalization in both context and activities, the resulting geometry addresses functional and situational needs rather than purely anatomical fit.

These results suggest broader applications in mass personalization and inclusive design, including wheelchair seating for persons with reduced mobility (PRM), rehabilitation seating, and operator environments where extended sitting is required. In such scenarios, individualized support informed by both anthropometric and contextual data has the potential to substantially enhance long-term comfort and performance.

4.6. Limitations

Several methodological considerations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results. Overall, the study represents an initial laboratory validation of the personalization workflow rather than a full dynamic or long-duration driving evaluation. All measurements were conducted in a static seating buck, which ensured experimental control and repeatability but did not capture dynamic influences such as vibration, acceleration, active seat suspension, or prolonged exposure to road-induced movements. The relatively short sitting duration (approximately 20 min per condition) also limits insights into long-term discomfort. Previous research suggests that meaningful differences in discomfort may emerge only after 40 min or more of continuous sitting [6]. Accordingly, the present findings should be interpreted as reflecting short-term comfort responses only. We have therefore clarified that future work should include experiments in real vehicles or high-fidelity driving simulators with representative vibration profiles and long-duration or repeated-measures protocols.

The sample provided realistic anthropometric diversity but did not include professional truck drivers, who represent the intended end-user group. Professional drivers may have distinct postural habits, musculoskeletal adaptations, and comfort expectations developed through long-haul experience. This limits the ecological validity of the present findings for occupational transport. The age and gender distribution also differed from the current workforce. Given the modest sample size (n = 16), the study was adequately powered for within-subject comparisons but not for subgroup analyses such as gender or body-size clusters. As a result, population-level generalization is limited, and a follow-up study involving more professional long-haul drivers in operational environments is required to confirm the transferability and usability of the personalized inserts in real-world practice. In addition, body-shape capture was performed with participants wearing indoor clothing; while clothing thickness was relatively consistent due to the climate-controlled environment, small variations may still influence local geometry and frictional behavior, suggesting that future protocols could standardize garments or compensate for clothing thickness during digital processing.

Using a single thermoplastic elastomer restricted the ability to tailor the stiffness properties of the inserts. Multi-material or functionally graded printing may support local stiffness tuning and improved thermal comfort. Moreover, the current seat-insert design employed a fixed lattice topology and uniform parametric settings; exploring computationally optimized lattice geometries and locally varied stiffness gradients may further enhance adaptability and comfort performance.

The pressure-mapping system measured only normal forces, preventing analysis of shear loading and micro-movements that contribute to discomfort during real driving. Incorporating shear sensors, posture-tracking, or physiological indicators (e.g., muscle activity) in future work would allow a more comprehensive assessment of tissue loading, postural stability, and fatigue development over time. Finally, although spatial pressure data were available, region-level comparisons (e.g., ischial tuberosities, thighs) were not performed because the personalized inserts reposition participants slightly within the seat pan, preventing consistent anatomical alignment across subjects. Future work will incorporate anatomical registration methods to enable robust region-by-region analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that integrating 3D scanning, computational design, and large-format additive manufacturing enables the creation of personalized seat inserts that measurably improve seating comfort for truck drivers. Across 16 participants, the inserts reduced mean pressure by 39%, peak pressure by 18%, and increased contact area by 15%, indicating a more even pressure distribution and improved physical support. Subjective comfort ratings were consistently higher for the personalized condition, with the largest improvements reported for buttock and thigh comfort. Qualitative feedback further highlighted enhanced postural stability, reduced sliding, and a generally firmer yet more secure seating experience. Together, these results confirm that geometry-based personalization offers a practical and quantifiable route to improving seating comfort in occupational transport.

Beyond the empirical findings, the study contributes a reproducible, context-driven personalization workflow that incorporates occupational posture, seat layout, and task constraints as design inputs. By anchoring personalization in real use context rather than generic anthropometry alone, the workflow provides a foundation for translating digital-fabrication methods into realistic transport applications, enabling individualized comfort solutions that remain compatible with existing seat architectures.

Future investigations should include long-duration and dynamic on-road evaluations, ideally involving a larger sample of professional truck drivers, to assess sustained comfort and the influence of vibration, motion, and seat-suspension dynamics. Integrating shear-force sensors, motion-tracking systems, or physiological measures would enable a more comprehensive understanding of posture stabilization, micro-movements, and comfort or discomfort development [33]. Further development of multi-material or functionally graded inserts may allow localized stiffness tuning and improved thermal behavior. In addition, establishing quantitative links between insert geometry and pressure-distribution outcomes would support data-driven refinement of personalized designs. Simulation-based approaches, such as finite element analysis (FEA) or machine-learning-assisted geometry optimization, may further enable predictive tuning of local stiffness and deformation characteristics. Future work should also include formal long-term durability testing of the printed materials to evaluate performance under repeated loading cycles. Finally, because the current process is semi-automated, advancing the workflow toward more automated or batch-personalization processes would increase scalability and reduce production time and cost, supporting broader adoption in occupational transport, rehabilitation seating, and inclusive mobility applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., M.Ö. and A.A.-H.; Methodology, Y.S., M.Ö. and B.S.; Validation, B.S. and A.A.-H.; Formal analysis, B.S. and Y.S.; Investigation, B.S. and Y.S.; Data curation, B.S. and Y.S.; Writing—original draft, B.S. and Y.S.; Writing—review and editing, M.Ö., A.A.-H. and Y.S.; Visualization, B.S. and Y.S.; Supervision, Y.S., M.Ö. and A.A.-H.; Project administration, A.A.-H., M.Ö. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of Delft University of Technology (Reference No. 5654, 27 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants for their time and contribution, as well as the support of colleagues at CoverWorks Health for their assistance in building the prototype and conducting the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Amir Anwar-Hameed was employed by CoverWorks Health. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Robb, M.J.M.; Mansfield, N.J. Self-Reported Musculoskeletal Problems amongst Professional Truck Drivers. Ergonomics 2007, 50, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyi, D.E.; Porter, J.M. Musculoskeletal Problems and Driving in Police Officers. Occup. Med. 1998, 48, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helander, M.G.; Zhang, L. Field Studies of Comfort and Discomfort in Sitting. Ergonomics 1997, 40, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Manary, M.A.; Schneider, L.W. Methods for Measuring and Representing Automobile Occupant Posture; SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE Technical Paper 1999-01-0959; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J.M.; Gyi, D.E.; Tait, H.A. Interface Pressure Data and the Prediction of Driver Discomfort in Road Trials. Appl. Ergon. 2003, 34, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Looze, M.P.; Kuijt-Evers, L.F.M.; van Dieën, J. Sitting Comfort and Discomfort and the Relationships with Objective Measures. Ergonomics 2003, 46, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, P.; Hallbeck, S. Editorial: Comfort and Discomfort Studies Demonstrate the Need for a New Model. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, N.; Naddeo, A.; Frohriep, S.; Vink, P. Integrating and Applying Models of Comfort. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 82, 102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, R.; Franz, M.; Bubb, H.; Vink, P. Technical Note: Spine Loading in Automotive Seating. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Vink, P. On the Objective Assessment of Comfort. In Proceedings of the International Comfort Congress 2021, Nottingham, UK, 2–3 September 2021; TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; He, Y.; Udomboonyanupap, S.; Hessenberger, N.; Song, Y.; Vink, P. Measuring Pressure Distribution under the Seat Cushion and Dividing the Pressure Map in Six Regions Might Be Beneficial for Comfort Studies of Aircraft Seats. Ergonomics 2023, 66, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilincsoy, U.; Wagner, A.; Vink, P.; Bubb, H. Application of Ideal Pressure Distribution in Development Process of Automobile Seats. Work 2016, 54, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, G.; Nussbaum, M.A. Driver Sitting Comfort and Discomfort (Part II): Relationships with and Prediction from Interface Pressure. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2008, 38, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noro, K.; Naruse, T.; Lueder, R.; Nao-I, N.; Kozawa, M. Application of Zen Sitting Principles to Microscopic Surgery Seating. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, Z.; Gao, F.; Zhang, T.; Mei, X.; Yang, F. Quantitative Evaluation of Vehicle Seat Driving Comfort during Short and Long Term Driving. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 111420–111432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantoine, P.; Lecocq, M.; Bougard, C.; Dousset, E.; Marqueste, T.; Bourdin, C.; Allègre, J.-M.; Bauvineau, L.; Mesure, S. Car Seat Impact on Driver’s Sitting Behavior and Perceived Discomfort during Prolonged Real Driving on Varied Road Types. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprigle, S.; Chung, K.C.; Brubaker, C.E. Reduction of Sitting Pressures with Custom Contoured Cushions. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 1990, 27, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, R.; Taylor, W.R.; Lorenzetti, S. Seat Pan and Backrest Pressure Distribution While Sitting in Office Chairs. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsous, M.; Lim, D.; Hendrix, R.; Bankard, J.; Rymer, W.Z.; Lin, F. Finite Element Analysis for Evaluation of Pressure Ulcer on the Buttock: Development and Validation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2007, 15, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Rosa, S.; Mayuet, P.F.; Silva, C.S.; Sampaio, Á.M.; Rodríguez-Parada, L. Design and Characterization of 3D-Printed TPU-Based Lattice Structures. Application to Methodology for the Design of Personalized Therapeutic Products. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, R.; Pickering, E.; Woodruff, M.A.; Holmes, D.W. Functionally Graded TPU Gyroid Structures for Cushioning Applications. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.; Linley, E.; Kalaskar, D.M. A Digital Workflow for Design and Fabrication of Bespoke Orthoses Using 3D Scanning and 3D Printing, a Patient-Based Case Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Che, L.; Shi, G.; Niu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; He, Y.; et al. Design of Personalized Cervical Fixation Orthosis Based on 3D Printing Technology. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2022, 2022, 8243128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leimer, K.; Winkler, A.; Ohrhallinger, S.; Musialski, P. Pose to Seat: Automated Design of Body-Supporting Surfaces. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2020, 79, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnoye, A.S.L.; Tajdari, F.; Doubrovski, E.Z.L.; Wu, J.; Kwa, F.; Elkhuizen, W.S.; Huysmans, T.; Song, Y. Personalized Product Design through Digital Fabrication. In Proceedings of the Volume 2: 42nd Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (CIE), St. Louis, MO, USA, 14–17 August 2022; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CR-Scan Ferret SE 3D Scanner. Available online: https://store.creality.com/products/cr-scan-ferret-se-3d-scanner (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Elkhuizen, W.S.; van den Dool, A.C.; Castro, J.M.; Song, Y.; Ozdemir, M.; Doubrovski, E.L.; Huysmans, T. Computational Design for (Industrial) Designers Using Rhino Grasshopper; TU Delft OPEN Publishing: Delft, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TF4OQD-LCNT FC/LF Series|THERMOLAST® K. Available online: https://pdb.kraiburg-tpe.com/?cid=5917 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- WASP 3MT HDP. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/large-scale-3dprinting/wasp-3mt-hdp/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Anjani, S.; Kühne, M.; Naddeo, A.; Frohriep, S.; Mansfield, N.; Song, Y.; Vink, P. PCQ: Preferred Comfort Questionnaires for Product Design. Work 2021, 68, S19–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, M.; Verlinden, J.; Cascini, G. Design Methodology for Mass Personalisation Enabled by Digital Manufacturing. Des. Sci. 2022, 8, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nace, S.; Tiernan, J.; Ní Annaidh, A. Manufacturing Custom-Contoured Wheelchair Seating: A State-of-the-Art Review. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2019, 43, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruithof, A.; Song, Y.W.; Vink, P. In-Chair Movements: Categorizations and Patterns over Time Based on a Literature Review. Work 2025, 10519815251394878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).