Abstract

This study discovers a real-time method for simulating progressive cutting in the Unity game engine. The proposed approach utilizes Position-Based Dynamics (PBD) to model deformable objects, making it suitable for applications such as surgical simulation training. Additionally, Unity’s compute buffers are employed to enhance computational efficiency through parallel processing. The cutting simulation operates on the surface mesh of the object, while internal deformations and volume preservation are represented using internal shape-preserving constraints (ISPCs). A series of progressive cutting experiments were conducted on various 3D models to evaluate the performance and accuracy of the algorithm. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves visually plausible real-time simulations of cuts.

1. Introduction

Cutting simulation is an important research field focused on developing methods to accurately represent object disintegration under physical constraints. Cutting simulation can be used in many different scenarios, such as 3D modeling, animation, biomechanics, medicine, and education. Recently, virtual reality (VR)- and augmented reality (AR)-based surgical training simulators have gained significant attention due to their advantages over traditional education [1]. In [2], it was found that in the scope of laparoscopic surgery training, VR simulators provide realistic surgical scenarios and objective performance assessments, while AR simulators have the potential to combine haptic feedback with visual guidance overlays, enhancing the overall learning experience. In dental education, VR- and haptics-based simulators have become globally acknowledged as essential learning tools [3,4]. A study in [5] reported that virtual simulation enables immersive and interactive environments where students can practice procedures, receive instant feedback, and build confidence without risking patient safety. The authors in [6] discovered that VR/AR training in oral and maxillofacial surgery not only improves performance but also supports planning for complex procedures, such as facial transplantation, where precise donor–recipient matching is very important. The study in [7] analyzed how surgery simulators are applied in the field of orthopedics. It revealed that VR-based simulators are more cost-effective than cadaveric- and animal-based training, as they allow unlimited practice without the substantial maintenance costs associated with animal laboratories.

In surgery simulation, one of the most challenging parts is the simulation of incisions, as it typically requires topology updates and complex physical responses [8,9]. A comprehensive literature review in [8] categorizes state-of-the-art cutting simulation techniques into mesh-based and mesh-free methods. Many studies have explored cutting simulation using geometrical elements such as vertices, edges and faces to represent model topology. These approaches can be grouped as a mesh-based cutting simulation. These methods are easy to construct, but they are prone to generating ill-shaped elements during cutting and require computationally expensive topological operations. From early research to modern work, tetrahedron-based simulations have received considerable attention as a simple yet accurate way to represent a deformable body. The study in [10] combines multiresolution techniques with particle systems derived from tetrahedral mesh decomposition. However, the authors acknowledge that particle systems are limited in their ability to model complex material properties. Subsequent research in [11] applied finite element method (FEM) to tetrahedral models to simulate more accurate material properties. To avoid an excessive increase in the number of tetrahedra, cuts were restricted to existing mesh faces. In [12], the authors proposed FEM-based cutting simulation using a tetrahedral mesh to model elastic–plastic deformation for brain surgery simulation. Here, plastic deformation is introduced to enhance fibrous tissue behavior under external load.

Although mesh-based methods still prevail in cutting simulation research, meshless models and hybrid approaches are frequently proposed to avoid the computationally expensive topological updates. Mesh-free methods replace vertices and elements with point clouds, where each point’s deformation is controlled by the declared equations of elasticity. However, maintaining accurate point-to-point neighborhood relationships is essential to calculate correct local deformation. In [13], the authors introduced a hybrid approach that combines a node-snapping algorithm with a mesh-free point-associated finite field method. Also, the work investigates knife–tissue interaction to apply pressure-induced deformation before cutting. The approach in [14] decomposes the simulated object into discrete nodes and stores the topological relations as an undirected graph. A bounding volume hierarchy is used for intersection testing and object reconstruction, enabling real-time performance. More recently, [15] proposed a meshless voxel-based simulation in which voxels deform under stretching and shape-matching constraints of Position-Based Dynamics (PBD).

Within computational modeling, FEM remains one of the most widely used approaches for physically simulating deformable bodies. Although FEM produces highly accurate results, it requires solving the governing equations of elasticity [16], which makes many FEM-based methods suitable only for interactive scenarios or even offline computation. The study in [17] presented an FEM-based cutting simulation designed for a real-to-sim-to-real loop in robotic applications. A highly detailed tetrahedral model of a tongue was used to simulate electrosurgery. However, the simulation was computationally intensive and could not be executed in real-time. As an alternative, PBD offers a constraint-based formulation that directly manipulates particle positions during deformation [18]. PBD is preferred in applications which require real-time performance over strict physical accuracy. The work in [19] introduced a PBD-based cutting method that achieves real-time simulations across various organs, employing a coarse tetrahedral mesh for deformation and cutting, while using a fine triangular mesh for rendering. In [20], authors combine PBD with FEM to implement blood suction and tissue cutting for teleoperation scenarios.

This study presents a novel method for simulating cuts in deformable objects using only a triangular surface mesh. We intentionally avoid tetrahedral meshes, as they require complex geometric reconstruction during cutting and significantly increase the number of degrees of freedom in the computational model. Instead, we employ internal shape-preserving constraints (ISPCs) [21] to approximate volumetric behavior and support large deformations. Our experiments show that ISPCs effectively restore the original volume of a deformed model. The proposed approach uses PBD to model physical behavior, enabling fast and stable simulation during cutting. Although PBD is generally less accurate than force-based methods such as FEM, its computational efficiency and robustness make it well-suited for real-time applications, with no drastic degradation of perceived physical behavior. ISPCs are integrated into the PBD pipeline to maintain the object’s internal volume and shape, even as the mesh undergoes cutting. To further optimize performance, an oriented bounding box (OBB)-based algorithm is used to reduce the number of intersection checks between the deformable model and the cutting tool. The remainder of the paper is as follows: Section 2 explains the core methodologies employed in this work, Section 3 presents the experimental setup and results, and Section 4 investigates the main findings and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

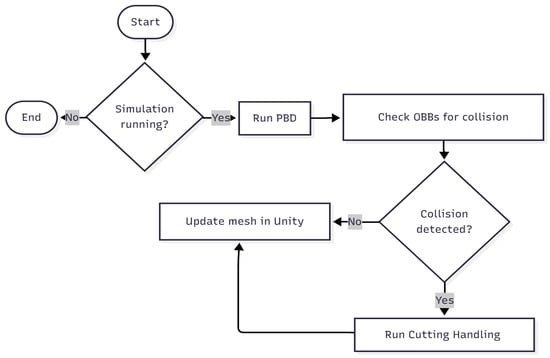

The proposed method includes three main parts: computational model, collision detection and handling, and cutting. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow of the algorithm.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the cutting algorithm.

2.1. Computational Model

In the present study, PBD was employed to simulate the physical behavior of deformable objects. Within the PBD framework, an object is discretized into a set of mass points interconnected by constraints [18,22]. These constraints define relationships between two or more mass points and play a crucial role in updating their positions during the simulation. Owing to its computational efficiency and simplicity, PBD is widely adopted in applications that demand real-time performance, while still offering stable and physically plausible results.

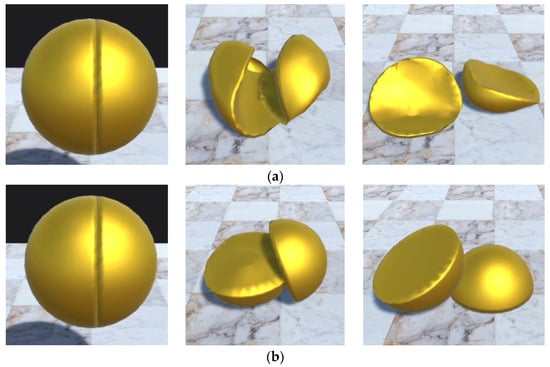

In this work, stretching and bending constraints were employed. Stretching constraints enforce a minimum and maximum allowable distance between mass points, thereby preserving local edge lengths. Bending constraints regulate the angle between adjacent triangles that share a common edge, maintaining surface smoothness. The Gauss–Siedel-like solver adjusts vertex positions to satisfy constraints. Additionally, custom internal shape-preserving constraints (ISPCs), as proposed in [21], were incorporated to prevent excessive deformation and to maintain the object’s volume throughout the simulation. The experiments in [21] show that ISPCs can reproduce deformation behavior comparable to that of tetrahedral meshes while requiring significantly less computational effort. Therefore, compared to other studies, the proposed method adopts ISPCs as an efficient alternative for simulating volumetric deformations. This allows us to avoid the use of additional internal mesh structures and the costly topology updates typically required during cutting. Figure 2 illustrates two sphere models that were cut in half and then collided with the floor. In (a), where no ISPCs were applied, the model exhibits a noticeable loss of volume. In contrast, (b) demonstrates that the use of ISPCs effectively preserves the sphere’s original volume and shape.

Figure 2.

Volume and shape comparison after cutting depending on ISPCs application: (a) without ISPCs; (b) with ISPCs.

2.2. Parallel Implementation

To accelerate constraint computations, Unity’s compute shaders were utilized. Compute shaders enable parallel execution by solving each constraint in a separate thread on the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). In Unity, these shaders are written in High-Level Shading Language (HLSL) for Direct3D. In the compute shader, functions are defined as kernels, and each kernel is executed over a specified number of workgroups. Each workgroup consists of multiple threads that run in parallel. In the current implementation, all kernels use 8 workgroups with 1024 threads per workgroup. A total of 10 GPU buffers were employed, as summarized in Table 1. Buffers associated with vertex data are allocated with a size equal to the number of vertices N. Buffers for distance and bending constraints are sized according to the number of constraints M. The ISPC buffer size is determined by the number of ISPC L. Finally, the CollidableCubes buffer is sized to match the number of cubes in the scene that can collide with the simulated object. Parallel implementation significantly increases the computational efficiency of the PBD framework. However, in the current cutting algorithm, each cut introduces additional vertices and triangles, making it challenging to fully exploit parallel processing since compute shaders do not support dynamic allocation of data buffers. Consequently, only the PBD constraint calculations and the collision detection and handling algorithms were implemented using compute shaders.

Table 1.

GPU buffers used in PBD routine.

2.3. Collision Detection and Handling

To realistically simulate the interaction between the cut parts of an object, we used the collision detection and handling approach described in [23]. Here, an axis-aligned bounding box (AABB) is used in the broad phase to detect the objects that may potentially collide. Then, the more precise Möller–Trumbore intersection algorithm is applied in the narrow phase. The algorithm uses a ray-to-triangle intersection test to detect the exact colliding triangles. To further enhance the computational efficiency of the algorithm, an octree of AABBs is built to reduce the number of triangle intersection tests.

Once a collision is detected, the collision response algorithm is invoked. The proposed algorithm calculates the average velocity of a triangle and the relative velocity for both intersecting triangles. Using this information, the direction of collision response is determined. However, the resulting repulsive effect can become excessively large, since a single vertex may simultaneously receive force from multiple triangles. To address this, the collision response is averaged before being applied to update the vertex positions.

To detect collisions between the cutting tool and the simulated object, we used oriented bounding box (OBB). As shown in [23], this bounding volume approach is more sophisticated than a simple AABB, because it aligns with the object’s local x, y and z axes according to its orientation. Consequently, the OBB remains aligned with the object it encloses and provides more accurate collision tests. However, this improved precision comes at a higher computational cost compared to AABB. Therefore, we only apply it in the broad phase of collision detection.

2.4. Cutting Handling

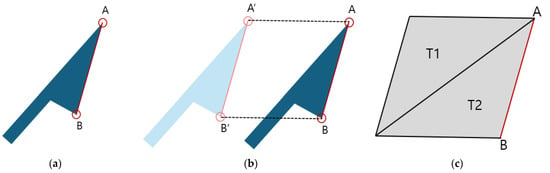

The current cutting algorithm consists of the following main functions: cutting plane update, triangle intersection check, triangle subdivision, hole patching and refinement, and constraints update. Algorithm 1 summarizes the implementation of cutting in the current study. Cutting starts with the cutting plane update in line 4. To accurately detect triangle intersections, a sweeping cutting plane is constructed, similar to the method in [24]. The knife blade is represented as a line segment with endpoints A and B as shown in Figure 3a. These are then connected to their previous positions, A’ and B’, forming a quadrilateral as in Figure 3b. This quadrilateral is subsequently divided into two triangles, T1 and T2, as in Figure 3c. Here, the current cutting edge AB is highlighted in red.

| Algorithm 1. Cutting Handling |

| 1: Require: initial surface triangles t 2: Require: initial vertices v 3: while simulation is running 4: UpdateCuttingPlane() 5: if(collision with the cutting tool) 6: for all ti triangles in t 7: if(intersected with current cutting plane cp) 8: add current triangle ti to trianglesToTraverse 9: end for 10: end if 11: end for 12: end if 13: for all triangles ti in trianglesToTraverse 14: for all triangles tj in ti’s adjacentTrianglesList 15: if(intersected with current cutting plane cp) 16: set intersection point, intersection edges, intersection vertices 17: add tj to trianglesToTraverse 18: add tj to intersectedTrianglesList 19: end if 20: end for 21: end for 22: for all ti in intersectedTrianglesList 23: subdivide triangle ti according to its intersection information 24: use cp to divide intersected edges into positiveEdgesList and negativeEdgesList 25: end for 26: patchTrianglesList ← triangulate(positiveEdgesList) 27: refinedTrianglesList ← refine(patchTrianglesList) 28: add refinedTrianglesList to the surface triangles list 29: repeat steps 27–30 for the negativeEdgesList 30: end while |

Figure 3.

Cutting plane construction: (a) A cutting tool is represented as a cutting edge(illustrated as the red line AB); (b) Cutting path captured by current position of cutting edge AB and previous position A’B’; (c) A cutting plane divided into two triangles T1 and T2.

When the OBBs of the cutting tool and the simulated object collide, the ray-to-triangle intersection algorithm is invoked. The two triangles, T1 and T2, that define the current cutting plane are tested against the object’s surface triangles t, as in line 7 of Algorithm 1. If an intersection is detected, the current triangle ti is added to the trianglesToTraverse list, and the loop ends. This triangle ti then serves as the seed triangle from which traversal begins. In this study, we propose to search only through adjacent triangles to identify intersected regions, rather than testing all surface triangles, in order to reduce computational cost. To enable this, triangle adjacency is constructed during preprocessing and updated dynamically during cutting. In lines 13–14, we iterate over triangles adjacent to those in trianglesToTraverse. Each adjacent triangle tj of intersected triangle ti is then tested for intersection with the current cutting plane, as in line 15. To detect intersection, tj’s 3 edges are treated as rays and each ray is tested against both cutting plane triangles. Then, the edges of the cutting plane are represented as rays and tested against tj. In total, 10 ray-to-triangle intersection checks are conducted. If an intersection is detected, the number of intersected edges and vertices, as well as the intersection point positions, are calculated and saved for current triangle tj, as in line 16. All intersected adjacent triangles are added to trianglesToTraverse and intersectedTrianglesList. More detailed information about the triangle traversal can be found in Appendix A Algorithm A1.

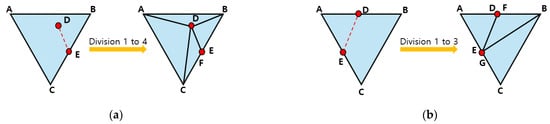

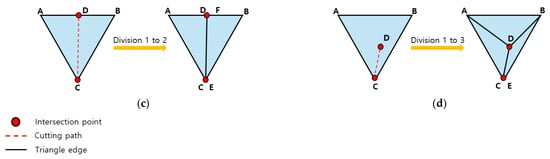

In this work, we use an element subdivision method to keep the cutting path as accurate as possible. When intersection checking step is finished for the current time step, all intersected triangles are subdivided in line 23 of Algorithm 1, depending on the intersection information. Figure 4 illustrates different subdivision patterns for a triangle ABC intersected by the cutting plane, according to number of intersected edges and intersection points. In Figure 4a, triangle ABC has one intersected edge BC and two intersection points: one on the edge BC and one inside the triangle’s interior. A 1-to-4 subdivision is performed by first connecting the intersection point D to the original vertices A, B, and C. The intersection point E is then duplicated as point F to fully subdivide edge BC. Then, E and F are connected to intersection point D. This produces four new triangles: ADB, ACD, DCF and DEB. Figure 4b demonstrates the 1-to-3a subdivision. Here, triangle ABC has two intersected edges, AB and AC, with intersection points D and E, respectively. New vertices F and G are created by duplicating D and E. One of the new vertices is then connected to one of the original vertices of triangle ABC, resulting in three new triangles: AED, FGB and GCB. In Figure 4c, a 1-to-2 subdivision is used. The cutting path intersects edge AB at point D and passes through the existing vertex C. New vertices F and E are generated by duplicating D and C, respectively. The triangle is then split into two new triangles: ACD and FEB. Figure 4d illustrates the 1-to-3b subdivision. Here, triangle ABC is intersected at the existing vertex C and at intersection point D. Only vertex C is duplicated to create a new vertex E. The intersection point D is then connected to vertices A, B, C and E, yielding three new triangles: ADB, ACD, DEB. In line 24, the intersected edges are divided into positive and negative lists depending on what side of the cutting plane they lie.

Figure 4.

Triangle subdivision schemes: (a) subdivision 1-to-4; (b) subdivision 1-to-3a; (c) subdivision 1-to-2; (d) subdivision 1-to-3b.

As our method uses only surface triangle mesh, completing a cut leaves an open hole in the mesh interior. To fill the hole, an ear-clipping triangulation algorithm from [25] is used in line 26 of Algorithm 1. The method generates new triangles using only existing boundary vertices. However, the resulting triangles can be significantly larger in size than those in the original mesh. Therefore, in line 27, a refinement algorithm from [25] is also applied to match the triangle resolution between the existing and the new mesh regions. Finally, the refined triangles are added to the surface mesh in line 28.

As the mesh topology of the object changes, the PBD constraints should be updated accordingly. First, stretching and bending constraints associated with the intersected triangles are removed. Then, new constraints are created for the newly generated triangles. In case of ISPCs, only intersected constraints are deleted. Then, new ISPCs are generated for vertices that do not yet have it. The new ISPCs help to keep the shape and volume of the simulated object even after it has been cut into parts and subjected to deformation.

3. Results

The technical specifications of the computer used in our research are Intel Core i7-7700 3.6 GHz CPU, 32 GB RAM, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060Ti and 8 GB V-RAM. The programming code was written and run in Unity 3D using JetBrains’ Rider IDE in C# language. We conducted progressive cutting experiments on the model Sphere 20, Sphere 80, Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana. Table 2 demonstrates vertices, triangles and ISPC numbers for each experiment model before and after cutting. Also, the deformation experiments were performed to observe shape and volume preservation of the models after cutting.

Table 2.

Three-dimensional models for the cutting experiments.

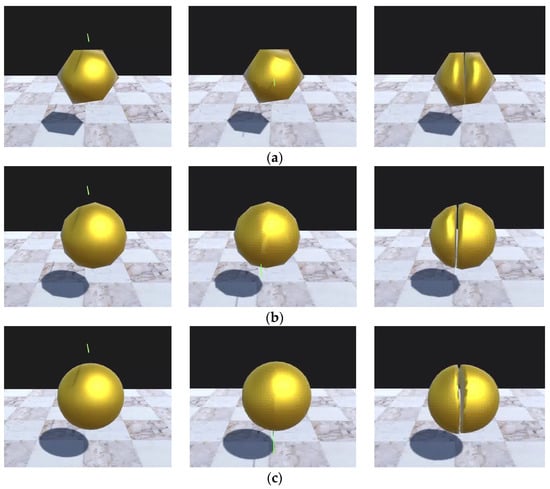

3.1. Progressive Cutting Eperiments

Progressive cutting experiments were executed on static models with no force applied to them. The cutting tool is simulated as a green prolongated cube model in Unity 3D. It moved vertically and cut the objects into two parts, as can be seen in Figure 5 and Figure 6. After cutting was finished, the gravity force and the collision detection algorithm were applied to the cut parts. The applied forces make the cut parts slightly move away from each other, as shown in Figure 4. It might be observed that in all five models, the element subdivision algorithm produces accurate cut surfaces which are aligned with the cutting trajectory. Time step and iteration number were set to 0.005 and 30 for Sphere 20 and Sphere 80, 0.005 and 20 for Sphere 768, 0.003 and 20 for Octopus, and 0.003 and 10 for Banana.

Figure 5.

Cutting simulation: (a) Sphere 20: time step 0.005, iteration number 30; (b) Sphere 80: time step 0.005, iteration number 30; (c) Sphere 768: time step 0.005, iteration number 20.

Figure 6.

Cutting simulation: (a) Octopus: time step 0.003, iteration number 20; (b) Banana: time step 0.003, iteration number 10.

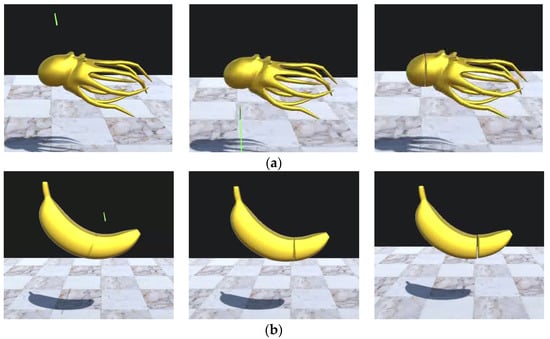

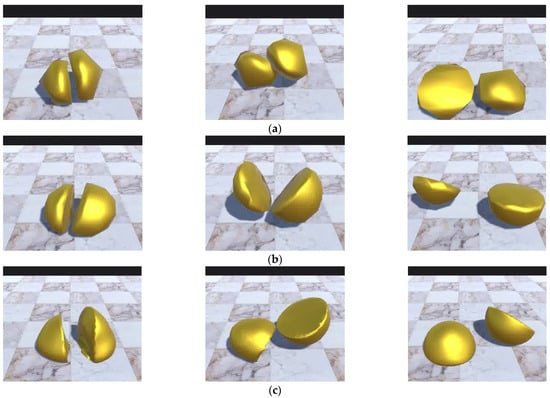

3.2. Deformation Experiments with ISPCs

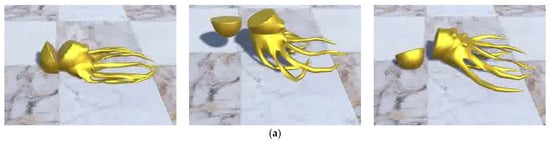

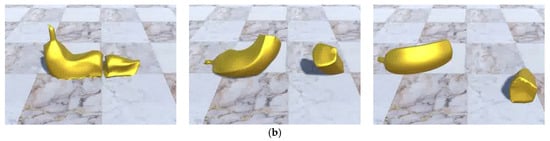

To evaluate the behavior of the models undergoing deformations, we simulated their collision with a floor. Therefore, the gravity force was applied to the cut pieces. The floor collision invoked the collision and handling algorithm from Section 2.3. Under the influence of gravity, the experimental models fall onto the floor. Despite experiencing significant deformation, the models could maintain their structure and recover their volume due to embedment of the internal shape-preserving constraints (ISPCs). The outcomes of these simulations are illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8. It is clear that high-resolution models such as Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana undergo more pronounced deformation upon impact with the floor. Nevertheless, the ISPCs effectively restore the original shape even in such cases. Furthermore, the collision detection and response algorithm described in [23] prevent interpenetration between separated parts during contact with the floor. The provided results also show that the method from [24] effectively triangulates the cut mesh.

Figure 7.

Deformation after cutting: (a) Sphere 20: time step 0.005, iteration number 30; (b) Sphere 80: time step 0.005, iteration number 30; (c) Sphere 768: time step 0.005, iteration number 20.

Figure 8.

Deformation after cutting: (a) Octopus: time step 0.003, iteration number 20; (b) Banana: time step 0.003, iteration number 10.

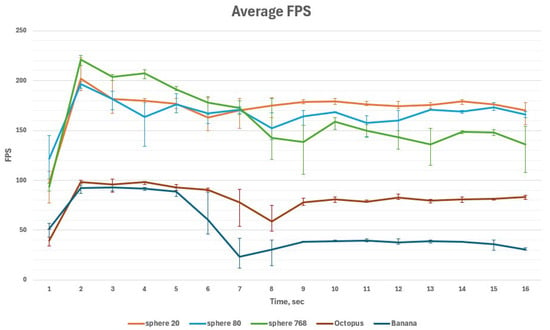

Figure 9 presents the average frames per second (FPS) recorded during cutting simulation for the Sphere 20, Sphere 80, Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana models. The average FPS were 172.1, 166.1, 160.5, 81.1 and 51.8 for Sphere 20, Sphere 80, Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana, respectively. Error bars in Figure 9 describe the smallest and biggest average FPS values calculated during experiments. The small models show very high FPS throughout the simulation, while the bigger Octopus and Banana models demonstrate relatively large FPS drop during the cutting.

Figure 9.

Average FPS with error bars of the cutting simulation of Sphere 20, Sphere 80, Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana.

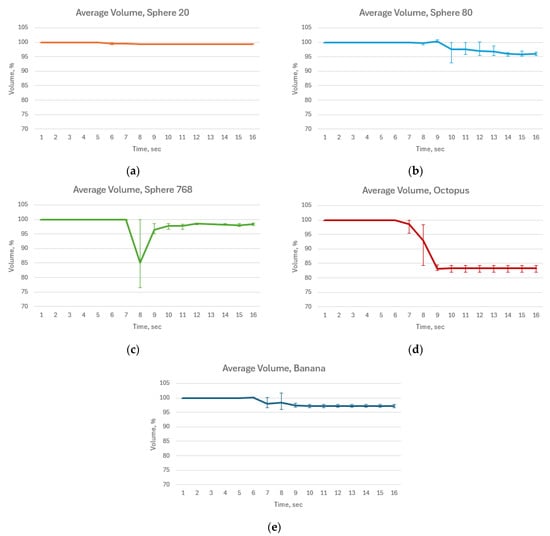

Figure 10 illustrates the average volume with error bars calculated during cutting simulation. The average volume rate was 99.6%, 98.5%, 98.0%, 91.1%, and 98.3% for Sphere 20, Sphere 80, Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana, respectively. As shown in Figure 10a,b,e, Sphere 20, Sphere 80 and Banana demonstrate negligible volume change throughout the simulation. In contrast, the Sphere 768 and Octopus models experience a significant volume drop when collided with the floor. However, Sphere 768 successfully recovered its original volume after the collision. In case of the Octopus model, the volume loss, despite not being very critical, stays on the same level.

Figure 10.

Average volume with error bars of the cutting simulation of (a) Sphere 20; (b) Sphere 80; (c) Sphere 768; (d) Octopus; (e) Banana.

3.3. Performance Evaluation

To further evaluate the performance of the proposed ISPC-based method, we conducted a comparison with our previous work in [24]. Table 3 summarizes the average FPS values obtained by both methods. While the previous method achieves higher average FPS for the simpler models, Sphere 20 and Sphere 80, the ISPC-based method clearly outperforms it on more complex models. For Sphere 768, Octopus, and Banana, the ISPC-based method yields performance gains of 48.06%, 56.87%, and 61.37%, respectively.

Table 3.

Performance evaluation of previous work and the ISPC-based method.

To more comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed ISPC-based method, Table 3 also reports the average, maximum and minimum computation time in ms for the deformation, collision, and cutting stages of the algorithm. The deformation stage comprises time integration, constrains solving and positions updates in the PBD framework. For all experimental models, the average and maximum deformation times are very small. The collision stage includes the time required to detect and handle collisions between the separated parts of the model. Here as well, the average and maximum times remain very low across all five models. The cutting stage measures how long it takes to perform the cut and update the mesh topology. On average, all models exhibit small cutting times, which increase gradually from the smallest to the largest model. However, the maximum computational times are noticeably higher than those for the deformation and collision stages. It is especially high in the Banana model, leading to interactive FPS rates during topology update. The computation time analysis shows that deformation and collision stages have only a minor or negligible impact on overall performance, whereas the cutting and topology update constitute the primary performance bottleneck.

4. Discussion

The current research introduces a new cutting simulation method, which uses surface triangle mesh for topology representation and ISPCs for shape and volume preservation. The experiments show that the cutting simulation can be performed with high FPS rate. As can be seen in Figure 9, the Sphere 20 model maintains a relatively stable FPS throughout the simulation, without significant frame drops. In comparison, the Sphere 80 model shows slightly less stability in FPS performance. The Sphere 768 model exhibits a noticeable FPS decline, particularly after the cutting operation is completed and new triangles are generated. However, on average, there was no big difference in FPS rate for all three models. For the more complex models, Octopus and Banana exhibit a greater FPS drop during cutting. However, after the cut, the FPS for Octopus recovers to a level comparable to that before cutting, whereas Banana shows a substantial and persistent FPS reduction. Also, the provided experiments demonstrate that ISPCs are an adequate method to efficiently preserve the original shape and volume even when the cut parts of an object experience large stress such as falling and collision with the floor.

The comparison with our previous work shows that the new ISPC-based method is substantially more efficient for larger models, such as Sphere 768, Octopus and Banana. We attribute this performance gain to the revised triangle intersection algorithm, which restricts the search to adjacent triangles, and thus, greatly reduces computational cost. Although the new method yields lower FPS for the simpler Sphere 20 and Sphere 80 models, it should be noted that the ISPC-based approach incorporates a more complex collision detection scheme and ISPC handling, whose overhead has a relatively larger impact on small-scale models.

During the computation time analysis, we found that cutting and topology updates have the greatest impact on the overall performance of the proposed method. It should be noted that deformation and collision stages are executed on the GPU, whereas cutting is performed on the CPU. Offloading the cutting process to the GPU is challenging due to frequent data updates and the need to dynamically increase buffer size. In future work, we plan to focus on performance optimization, considering these limitations and the difficulties of implementing the cutting algorithm in parallel with the GPU.

Further investigation using models with higher face counts and more complex geometries is necessary to validate the applicability of the proposed method in diverse cutting scenarios. To advance the system toward use in surgical simulation, we consider it is essential to develop a realistic environment and incorporate the actual material properties of the simulated tissues. Also, to provide more comprehensive performance and accuracy results in the future, we consider comparing our method to one of those based on FEM architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.K., T.K. and M.H.; methodology, L.D.K. and M.H.; software, M.H.; validation, L.D.K., T.K. and M.H.; formal analysis, L.D.K.; investigation, L.D.K. and T.K.; resources, L.D.K. and T.K.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.K.; writing—review and editing, L.D.K., T.K. and M.H.; visualization, L.D.K.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, T.K.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2022R1I1A3069371), funded by BK21 FOUR (Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research) (No.: 5199990914048), and was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBD | Position-Based Dynamics |

| ISPC | Internal Shape-Preserving Constraints |

| AABB | Axis-Aligned Bounding Box |

| OBB | Oriented Bounding Box |

Appendix A

Here, we present additional algorithms used in the current work.

| Algorithm A1. Triangle Traversal |

| 1: Require: Intersected triangles to traverse trianglesToTraverse, adjacency dictionary adjacentTriangles, cutting plane cp, cutting triangles T1 and T2, list of visited triangles visited 2: Output: list to store intersected triangles after traversing intersectedTrianglesList 3: while trianglesToTraverse is not empty 4: dequeue ti from trianglesToTraverse 5: for all triangles tj in adjacentTriangles[ti] 6: if visited contains tj 7: continue 8: for all edges e in tj 9: for all cutting triangles T1 and T2 10: if e intersects T1 or T2 11: set intersection point, intersection edges, intersection vertices 12: end if 13: end for 14: end for 15: for all edges e in cp 16: if e intersects tj 17: set intersection point, intersection edges, intersection vertices 18: end if 19: end for 20: if (tj intersects with cp) 21: add tj to intersectedTrianglesList 22: enqueue tj to trianglesToTraverse 23: add tj to visited 24: end if 25: end for 26: end while |

References

- Riddle, E.W.; Kewalramani, D.; Narayan, M.; Jones, D.B. Surgical Simulation: Virtual Reality to Artificial Intelligence. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2024, 61, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.; Rozenblit, J.W.; Hamilton, A.J. Simulation-based surgical training systems in laparoscopic surgery: A current review. Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, H.; Ye, F.; Liu, Y.; Lv, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y. The Current Situation and Future Prospects of Simulators in Dental Education. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, E.; Adanir, N.; Khurshid, Z. Significance of Haptic and Virtual Reality Simulation (VRS) in the Dental Education: A Review of Literature. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badash, I.; Burtt, K.; Solorzano, C.A.; Carey, J.N. Innovations in surgery simulation: A review of past, current and future techniques. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucki, J.; Dastgir, R.; Baur, D.A.; Quereshy, F.A. The use of virtual reality and augmented reality in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A narrative review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2024, 137, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruikar, D.D.; Hegadi, R.S.; Santosh, K.C. A Systematic Review on Orthopedic Simulators for Psycho-Motor Skill and Surgical Procedure Training. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Westermann, R.; Dick, C. A Survey of Physically-based Simulation of Cuts in Deformable Bodies. Comput. Graph. Forum 2015, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, Y. A review of virtual cutting methods and technology in deformable objects. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2018, 14, e1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganovelli, F.; Cignoni, P.; Montani, C.; Scopigno, R. A Multiresolution Model for Soft Objects Supporting Interactive Cuts and Lacerations. Comput. Graph. Forum 2000, 19, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuys, H.W.; van der Stappen, A.F. A Surgery Simulation Supporting Cuts and Finite Element Deformation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2001, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 14–17 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.X.; Hou, W. Modeling fibrous soft tissue dissection with elastic-plastic deformation for simulation of brain tumor removal. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 232, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.-J.; Jin, W.; De, S. On some recent advances in multimodal surgery simulation: A hybrid approach to surgical cutting and the use of video images for enhanced realism. Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2007, 16, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Lee, D.Y. Real-time cutting simulation of meshless deformable object using dynamic bounding volume hierarchy. Comp. Anim. Virtual Worlds 2012, 23, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Milef, N.; De, S. Divided Voxels: An efficient algorithm for interactive cutting of deformable objects. Vis. Comput. 2021, 37, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gockenbach, M.S. Understanding and Implementing the Finite Element Method; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, L.; Kilmer, E.; Mady, L.; Opfermann, J.; Krieger, A. Enhancing Surgical Precision in Autonomous Robotic Incisions via Physics-Based Tissue Cutting Simulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.; Heidelberger, B.; Hennix, M.; Ratcliff, J. Position based dynamics. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2007, 18, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, R.; Ma, L.; Xu, M.; Zhou, Y. Hybrid Optimization-based Cutting Simulation for Soft Objects. Comput. Aided Des. 2023, 163, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Zargarzadeh, S.; Sedighi, P.; Tavakoli, M. A Realistic Surgical Simulator for Non-Rigid and Contact-Rich Manipulation in Surgeries with the da Vinci Research Kit. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR), New York, NY, USA, 24–27 June 2024; pp. 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-K.; Kim, T.-W.; Choi, Y.-J.; Hong, M. Volumetric Object Modeling Using Internal Shape Preserving Constraint in Unity 3D. Intell. Autom. Soft. Comput. 2022, 32, 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.; Müller, M.; Macklin, M. A survey on position based dynamics. In Proceedings of the European Association for Computer Graphics: Tutorials (EG ‘17), Lyon, France, 24–28 April 2017; Eurographics Association: Goslar, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, N.-J.; Ma, J.; Hor, K.; Kim, T.; Va, H.; Choi, Y.-J.; Hong, M. Real-Time Physics Simulation Method for XR Application. Computers 2025, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Choi, Y.-J.; Hong, M. Cutting Simulation in Unity 3D Using Position Based Dynamics with Various Refinement Levels. Electronics 2022, 11, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, D. Triangulation by Ear Clipping; Geometric Tools: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008; pp. 2002–2005. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).