Featured Application

Optimised design of a solid-state circuit breaker for parallel connection of multiple fuel-cell cabinets to a high-voltage bus connection for high-power maritime applications.

Abstract

Designing solid-state circuit breakers (SSCBs) involves a large discrete design space spanning MOSFET type, bypass configuration, and heatsink selection. This work formulates SSCB design as a multi-objective combinatorial optimisation problem that minimises conduction loss and material cost subject to electrothermal feasibility constraints. A validated electrothermal model was developed using experimentally measured RDSon(T) data and thermal-impedance characterisation, allowing rapid and accurate evaluation of candidate configurations. Because the full design space exceeds one million combinations, five representative metaheuristic algorithms: Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO), Grey Wolf Optimisation (GWO), Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), and Gorilla Troops Optimisation (GTO), were benchmarked under an identical computational budget of 2000 evaluations. Sobol sequence initialisation was used to enhance search diversity. Each algorithm was executed 100 times, and its performance was quantitatively assessed using hypervolume, generational distance (GD), inverted generational distance (IGD), Hausdorff distance, overlapping-point score (OP), overall spread (OS), and distribution metrics (DM). GA consistently produced the closest approximation to the true Pareto front obtained from brute-force enumeration, achieving superior accuracy, coverage, and robustness. GTO offered strong secondary performance, while PSO, GWO, and ACO delivered partial front reconstruction. The results demonstrate that metaheuristic optimisation, particularly GA, can reduce SSCB design time significantly while retaining high fidelity, offering a scalable and efficient framework for future power-electronics design tasks.

Keywords:

metaheuristic optimisation; evolutionary algorithms; genetic algorithm; particle swarm optimisation; grey wolf optimisation; ant colony optimisation; gorilla troops optimisation; power electronics design; solid-state circuit breaker; electrothermal modelling; brute-force optimisation; discrete combinatorial design; fuel-cell systems 1. Introduction

Solid-state circuit breakers (SSCBs) rated up to 1.2 kV (e.g., for an 800 V bus) and capable of handling currents exceeding 100 A typically utilise silicon carbide (SiC) devices in various topologies [1]. Among these, SiC MOSFETs and SiC JFETs are most common, with reported switching times ranging from under 200 nanoseconds to several milliseconds and conduction losses between 122 W and 230 W in the on-state [2]. Certain high-current designs demonstrate conduction losses of less than 1 kW at 1 kA, with a voltage drop below 1 V at 400 K (~127 °C) [3,4,5].

While SiC-based switches dominate high-speed applications, insulated gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs) and reverse-blocking integrated gate-commutated thyristors are also employed where very high currents or bidirectional operation are required [3]. Effective SSCB operation must be coordinated with grid protection schemes, tolerate high fault currents, and provide fast isolation [6,7].

SSCBs are increasingly used in high-power sectors such as electric vehicles, medium-voltage grids, aerospace, and marine platforms, where both thermal and electrical optimisation are essential [2,3,8]. Over recent decades, a diverse range of optimisation algorithms has emerged, many inspired by biological evolution or swarm intelligence. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) mimic Darwinian selection, while Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO), Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) draw from social or collective behaviours. Among newer algorithms, Grey Wolf Optimisation (GWO) has proven effective in balancing exploration and exploitation, particularly in discrete design problems [9,10,11].

Recent nature-inspired metaheuristics have also gained traction, particularly those designed for discrete and mixed-integer optimisation. ACO, based on pheromone-guided probabilistic sampling, has been successfully applied to component selection and routing problems with combinatorial structure. More recently, Gorilla Troops Optimisation (GTO) has been proposed as a social-behaviour-based algorithm that alternates between exploration and exploitation modes and has demonstrated strong performance on discrete and mixed-integer engineering problems. These developments have broadened the range of optimisation strategies available for complex design tasks such as SSCBs.

Although most swarm intelligence algorithms were developed for continuous search spaces, recent work has shown successful adaptation to discrete combinatorial domains such as SSCB design. For instance, hybrid PSO-GA methods have demonstrated improved convergence and diversity when applied to complex electrical design tasks [12]. Studies have also validated the effectiveness of GWO for real-time circuit breaker monitoring and DC-link control, reinforcing its applicability in systems with discrete configurations and constraints [13,14].

This relevance is underscored by the nature of SSCB design, which involves selecting from various discrete components, including switch type, bypass configuration, and heatsink, resulting in solution spaces ranging from millions to trillions of configurations. Traditional optimisation techniques (e.g., gradient-based methods) are unsuitable for such non-continuous, high-dimensional design landscapes [15].

Emerging surveys highlight the growing utility of hybrid and modified metaheuristics, which integrate global search with local heuristics or greedy strategies to boost convergence and efficiency [16,17]. For example, hybrid firefly-GAs have been applied to directional overcurrent relay coordination [18], while enhanced GWO techniques have supported fault detection and lifespan prediction in electromagnetic breakers [7,19].

A detailed comparison of the five metaheuristic algorithms considered in this study (GA, PSO, GWO, ACO, and GTO) is presented in Table 1, outlining their search behaviours, strengths, limitations, and applicability to power-electronics design. This expanded comparison highlights the suitability of evolutionary, swarm-based, and nature-inspired methods for SSCB optimisation, with several algorithms demonstrating strong adaptability to discrete design spaces and multi-objective constraints.

Table 1.

Comparison of GA, PSO, and GWO in the context of SSCB design and broader power electronics system applications.

Metaheuristic performance should be assessed across multiple criteria, including convergence rate, solution diversity, and computational cost, especially in multi-objective optimisation scenarios involving thermal, electrical, and economic constraints [16,29]. Recent developments encourage the use of surrogate modelling, adaptive hybridisation, and learning-based strategies to mitigate high simulation costs and expedite convergence [17,24].

In SSCB design, these benchmarking principles are vital due to competing objectives such as on-state power loss, thermal dissipation, and cost. As demonstrated in recent studies of DC modular breakers, algorithmic optimisation significantly enhances fault-handling capability, even enabling interruption transient estimation.

This work formulates SSCB design as a discrete combinatorial optimisation problem, capturing the joint influence of switching device, bypass configuration, and heatsink selection. Unlike traditional optimisation approaches that assume continuous parameters, this formulation explicitly reflects the discrete nature of practical component libraries.

A suite of five metaheuristic optimisation algorithms, GA, PSO, GWO, ACO, and GTO, is implemented and systematically benchmarked against brute-force analysis. Together, these methods span evolutionary, swarm-based, and nature-inspired families, providing a diverse and practically relevant cross-section of optimisation strategies for discrete SSCB design. This broadened set of algorithms allows a more comprehensive comparison of optimisation behaviour under a fixed computational budget.

To enhance the exploration capabilities of the metaheuristics and ensure population diversity from the outset, this work employs Sobol sequence-based quasi-random initialisation, which distributes candidate solutions more uniformly across the search space. This approach helps mitigate premature convergence and improves consistency across multiple runs.

An electrothermal SSCB performance model is developed and validated against experimental measurements, ensuring that optimisation results remain physically meaningful and practically deployable. Results show that genetic algorithms, in particular, can efficiently identify near-optimal configurations with substantial reductions in computational effort. The proposed framework is readily extensible to more complex power-electronic systems such as dual-active-bridge converters and modular multilevel topologies, where discrete component combinations and thermal constraints dominate design feasibility.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

- Formulation of SSCB design as a large-scale discrete combinatorial optimisation problem, explicitly capturing the interaction between switching-device selection, bypass configuration, and heatsink thermal performance.

- Development and experimental validation of a rapid electrothermal modelling framework, enabling accurate prediction of conduction loss and junction temperature across a wide range of SSCB configurations.

- Implementation and fair benchmarking of five metaheuristic optimisation algorithms (GA, GTO, GWO, PSO, and ACO), all evaluated under an identical computational budget of 2000 designs to enable rigorous comparison.

- Use of Sobol sequence initialisation to improve design-space coverage and mitigate premature convergence, enhancing the robustness of population-based optimisation methods.

- Comprehensive multi-metric performance analysis across 100 independent runs, using HV, GD, IGD, Hausdorff, OP, OS, DM, and SPnorm, demonstrating that GA most effectively reconstructs the true Pareto front with over a 100-fold reduction in computational effort compared with brute-force evaluation.

The remainder of the manuscript is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the discrete multi-objective optimisation problem, defining the decision variables, objectives, and feasibility constraints relevant to SSCB design. Section 3 presents the optimisation methods employed, describing the implementation details and parameter settings for the five metaheuristic algorithms. Section 4 reports and analyses the optimisation results, including representative Pareto fronts, feasibility statistics, and a comprehensive multi-metric comparison across 100 independent runs. This is followed by a broader discussion of the implications and scalability of the proposed approach in Section 5. Finally, Section 5 summarises the main conclusions and highlights opportunities for future work.

2. Optimisation of SSCBs (Combinatorial Optimisation Problem)

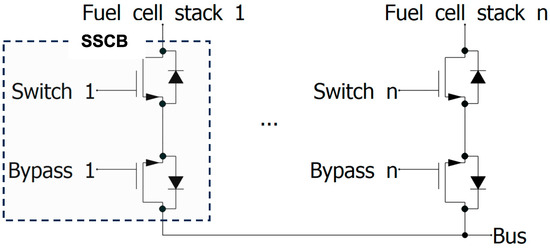

When using fuel cells, it is important to understand the wide operating voltage range, which can be described as a function of current density, as described by their polarisation curves [30]. For maritime applications, the power levels extend into the MW region, and to meet these demands, multiple fuel cell cabinets in parallel are required. When operating at high voltages with multiple fuel cell modules in cabinets in parallel, there is potential for the voltage on the fuel cell to fall below the system bus voltage. In this scenario, without adequate protection, current would flow from the bus into the fuel cell, which could cause significant damage to the fuel cell. There are numerous SSCB topologies reviewed widely in the literature, which balance advantages with drawbacks [31]. A simple method to overcome this is to use a diode to prevent current flow back into the fuel cell. This method is effective; however, the inherent conduction losses of the diode need to be considered. One common method to reduce these losses is to use active (or synchronous) rectification, where diodes are replaced with actively controlled switches. Where this device is a power MOSFET, it is possible to make use of the body diode to support current flow. Additionally, it can enable operation where the fuel cell voltage approaches the bus voltage (albeit at lower power levels). In the simplified schematic in Figure 1, it can be seen that each stack has two switches, with the orientation of the lower switch flipped. The first switch, “main”, enables isolation of the fuel cell from the system. The second, referred to here as “bypass”, continuously connects the first switch to the bus via the body diode and also has a second optional electrical path via the MOSFET channel when the bypass is enabled. The advantage of enabling the bypass MOSFET is that the conduction loss for that device is significantly reduced owing to the low on-resistance (RDSon) of the MOSFETs. However, in this mode of operation, current through the SSCB, the bus voltage and fuel cell stack voltage must be closely monitored, as there is no protection in the event that the fuel cell voltage falls below the bus voltage.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the system incorporating the SSCB with active rectification.

In addition to the electrical performance of the switches, the thermal behaviour of the system also needs to be analysed. The RDSon and body diode conduction characteristics of MOSFETs are highly dependent on the junction temperature (Tj) [32]. To accurately estimate the conduction losses, the device temperature must be calculated; hence, the cooling system (heatsink) options also need to be considered.

The calculation of the conduction loss in steady-state conditions can be solved rapidly using standard computation methods. By iteratively solving both the electrical and thermal domains, the simulator can accurately predict the MOSFET’s temperature and power dissipation under various operating conditions. Several checks are performed on the results to determine if a design is feasible; one key verification being whether the predicted Tj exceeds 70% of the Tjmax for the devices.

This case study focuses on the design of a simple power electronics circuit, an SSCB, aiming to clearly illustrate the advantages of using optimisation algorithms (such as GA) to tackle combinatorial problems. The primary hurdle here lies in the combinatorial nature of the design process. There is a vast array of available MOSFETs from numerous manufacturers, each presenting unique electrical characteristics, thermal behaviours, and cost implications.

Beyond the MOSFET selection, heatsink thermal resistance versus cost was also considered. Given the high current requirements for the target application, single MOSFET solutions (per main and bypass switches) are not sufficient. For this particular application, possible combinations of identified candidate MOSFET models allowed for up to three devices (each) in parallel for both the main switch and the bypass device. Denoting NM and NH as the number of MOSFETs and heatsink options, respectively, the number of configurations per main/bypass switch (NS) and total design configurations (NTOTAL) can be expressed using standard combinatorial counting based on binomial coefficients:

For the example considered in this study, where and , the number of switch configurations becomes:

And therefore:

This formulation highlights that even with a modest set of devices and heatsinks, the design space rapidly expands to well over one million feasible combinations.

For this example application with ≥1.2 kV rated devices, there are hundreds of potential MOSFETs that could be considered. This illustrates the rapid scaling of the design space: increasing the number of candidate switch types (NS) from 10 to 100 causes the total number of combinations (NTOTAL) to grow from 1.1 million to 437 billion. Such explosive growth highlights why brute-force exploration quickly becomes impractical as the parameter set expands.

To more rigorously frame the SSCB design task, the selection of switching devices, the number of devices in parallel, and the heatsink choice are formulated as a discrete multi-objective optimisation problem.

Each design is represented by the decision vector:

where

= (MOSFET model, number in parallel )

= same structure as above

= heatsink index

with MOSFET choices drawn from:

- Objectives:

The multi-objective function to be minimised is:

where

= total conduction loss (main + bypass switches)

= material cost (MOSFETs + heatsink)

- Constraints:

A design is considered feasible only if:

where

= junction temperature of each of the MOSFETs

= maximum junction temperature

The electrothermal model must converge for the given operating point.

This defines the feasible set:

The optimisation task is therefore:

It is worth noting that the SSCB optimisation problem is a fully discrete combinatorial search task. The design variables represent categorical device indices and parallel device counts, and many combinations lead to infeasible operating points. Consequently, the objective functions are discontinuous and non-differentiable, making classical gradient-based optimisation methods unsuitable. For this reason, a range of population-based metaheuristic methods are employed and quantitatively evaluated in Section 4.1.

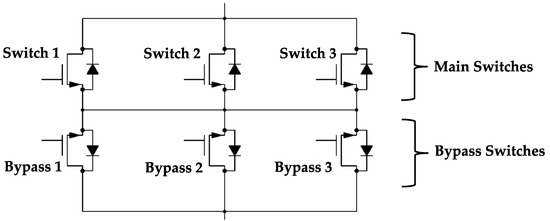

For SSCB design, the thermal performance can be addressed through methods such as finite element analysis, ANSYS (Icepak), and circuit simulation tools (PLECs), while design solutions include low-inductance packaging, air or liquid cooling, and thermally defined fuse curves to manage elevated junction temperatures and ambient constraints above 125 °C [3]. For this work, the focus is on DC performance; hence, a simple thermal network is used, which can be rapidly computed. Even though the conduction loss and cost for each design combination can be calculated in less than 1 s (per design) using a SPICE-based simulator, the sheer volume of combinations makes optimisation by brute force impractical. Restricting the design space to 10 MOSFET models, 14 heatsink options, and up to 3 devices in parallel (Figure 2) makes a brute-force analysis feasible, providing a benchmark for demonstrating the benefits of optimisation algorithms such as GAs.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the SSCB configuration with 3 MOSFETs for the switch and 3 MOSFETs in parallel for the bypass.

3. Materials and Methods

To ensure a fair and representative comparison, a selection of well-established metaheuristic algorithms was chosen, spanning evolutionary methods (e.g., GA), swarm-based approaches (PSO, GWO), and nature-inspired strategies (GTO, ACO). These algorithms are widely applied in engineering optimisation and are compatible with the discrete, combinatorial nature of the SSCB design space. The intent of this study is not to survey all available metaheuristics but to benchmark a diverse and practically relevant subset under an equal evaluation budget.

To enable accurate benchmarking of the optimisation algorithms, a brute-force analysis was performed to generate the complete dataset of feasible solutions, providing the true reference against which algorithm performance could be assessed. The use of a circuit simulator (LTspice) was initially considered; however, the average calculation speed (including processing results) was measured as ~0.825 s/design. For a dataset comprising 1,137,150 designs, the estimated processing time is ~11 days. This projection is based on the optimistic assumption that all designs can be solved efficiently and without encountering simulation issues such as non-convergence.

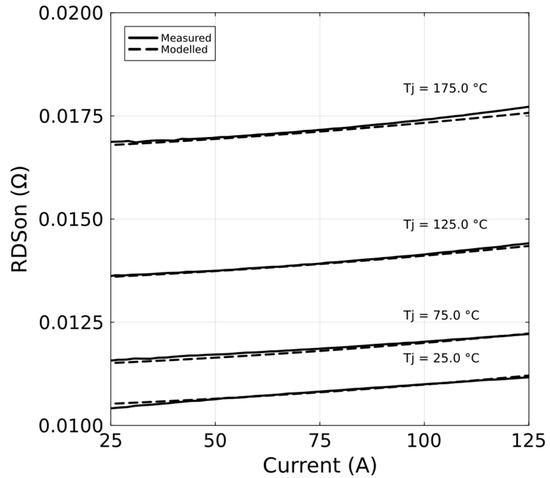

Using datasheets, SPICE models, and experimental data from a curve tracer (Keysight B1505, CA, USA), we created mathematical models for each of the 10 MOSFETs. These models described the effective RDSon as a function of Tj and IDS. These models accurately described the MOSFET behaviour in both the forward and reverse orientations; an example of one MOSFET model in the forward orientation being compared with measured data from the curve tracer can be seen in Figure 3. It can be seen that over the full temperature range from 25 °C to 175 °C and the full current range from 20 A to 120 A, the model accurately describes the RDSon.

Figure 3.

Graph of modelled and measured RDSon as a function of current over a range of Tj values; the model gives excellent agreement with the measured results.

Accurate measurements of the thermal transient behaviour, including the structure function, were achieved using a PowerTester system (Mentor Graphics MicReD 1500A in conjunction with T3sterMaster, Wilsonville, OR, USA). These measurements captured the thermal behaviour of the devices under realistic switching conditions with consideration for the thermal stack (consisting of device, TIM, and heatsink). To determine cost and thermal properties, the models utilised lookup tables for both the components (with values for cost and Rth_jc) and the heatsinks (with corresponding cost and Rth values). The electrothermal calculations for both the brute-force reference and the optimisation algorithms were implemented in a scripting environment using a non-linear solver. Direct LTspice simulation would have required evaluating over one million combinations, resulting in a projected runtime of around 11 days, which is impractical. By re-creating the device and heatsink models directly in a scripting language, the simulations could be executed much faster and with fewer convergence issues. This approach reduced the total brute-force evaluation time to approximately 14 min, while also enabling efficient execution of the metaheuristic optimisation methods.

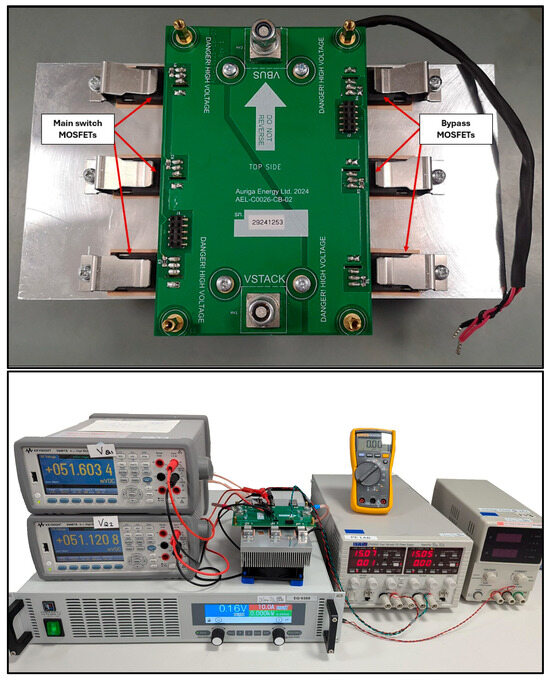

Whilst the emphasis of this work was on the demonstration of the benefit of using optimisation algorithms such as GA for power electronics design optimisation, it is also important to demonstrate that the conduction loss calculation methodology was accurate. To validate the model, a prototype SSCB system was built and tested with a load current up to 120 A, photographs of which can be seen in Figure 4. The test current was provided by a high current power supply (EA Elektro Automatik: EA-PS 9040-120, Beaverton, OR, USA) and measured with a current clamp (Fluke: 325, Everett, WA, USA). During testing, the voltage across the main and bypass switches was monitored using 6 ½ digit multimeters (Keysight: 34461A, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The temperature of the heatsink was monitored using a temperature logger (PicoLog: TC-08, Cambridgeshire, UK). Given the thermal lag of the system, the measurements were taken when the SSCB reached thermal equilibrium (steady state) for each of the current levels tested. The test equipment used offers high resolution and accuracy, and is calibrated on an annual basis. The digital multimeters (Keysight 34461A) have a quoted accuracy of ±35 ppm of reading, the current clamp (Fluke 325) has an accuracy of ±(2% of reading + 5 digits), and the temperature logger (Pico TC-08 with type K thermocouple) has an accuracy of ±(0.2% of reading + 0.5 °C) [33,34,35].

Figure 4.

(Top): photograph showing the prototype SSCB system for validating the model. The system consisted of 3 MOSFETs for the main switch and a further 3 MOSFETs for the bypass switch. The MOSFETs were all the same model. The high current path was created using thick copper traces on the PCB. The MOSFETs were mounted onto a heatsink (with phase change TIM) and supported by spring clips. The heatsink was air-cooled with two fans (attached to the heatsink cooling fins). (Bottom): photograph of the key components of the test setup (some connections, for example, the thermocouple connections from the heatsink to the temperature logger, have been omitted for clarity).

The MOSFET conduction loss was computed using:

where is the steady-state device current and is the temperature-dependent on-state resistance extracted from measured device data (e.g., Figure 3). The junction temperature was obtained by solving the electrothermal network, consisting of the device thermal impedance, thermal interface, and the selected heatsink. This iterative calculation captures the mutual coupling between conduction loss and device temperature, and the resulting model is used to evaluate every SSCB design considered by the optimisation algorithms. A concise pseudo-code description of this evaluation workflow is provided below, which summarises how each candidate design is decoded, assessed for feasibility, and mapped to its corresponding objective values.

| Pseudo-code description for cost–function evaluation for a candidate SSCB design Input: x = (Smain, Sbypass, hs) // device indices and heatsink index Output: f(x) = (Pcond, Cost) // conduction loss and material cost 1. Decode device selections: - Identify MOSFET models for main and bypass switches - Determine the number of devices in parallel - Select heatsink properties 2. Obtain electrical characteristics: - Extract RDSon(T) curve for each MOSFET - Compute steady-state current through main and bypass switches 3. Compute conduction loss: - Pmain = Imain2 × RDSon(Tmain) - Pbypass = Ibypass2 × RDSon(Tbypass) - Pcond = Pmain + Pbypass 4. Solve the electrothermal model: - Use device thermal impedance + interface + heatsink - Iteratively compute junction temperatures Tj until electrical and thermal calculations converge 5. Check feasibility: - If model diverges → return (∞, ∞) - If constraints in Section 2 are violated → return (∞, ∞) 6. Compute material cost: - Cost = cost(MOSFETs) + cost(heatsink) 7. Return objective values: - f(x) = (Pcond, Cost) |

To enable a fair and consistent comparison, all metaheuristic optimisation algorithms employed the same fitness function, incorporating both conduction power loss and component cost. Additionally, each algorithm was constrained to a maximum of 2000 design evaluations, ensuring uniform computational effort across methods. To maintain comparability, the algorithm parameters were selected to be as similar as practicable across the different metaheuristics; however, certain values were adjusted where appropriate to reflect the intrinsic characteristics of each method and to ensure that all approaches reached the same evaluation budget. For reference, a simple random-selection (RS) baseline was also included, in which 2000 randomly sampled SSCB designs were evaluated to provide a lower-bound benchmark for algorithmic performance. The following subsections provide a concise overview of each optimisation method and its specific implementation in the context of SSCB design.

3.1. Genetic Algorithm

A custom Pareto-based multi-objective GA was implemented to efficiently explore the large discrete design space associated with SSCB optimisation. The method is inspired by the NSGA-II framework, retaining its core principles—Pareto dominance ranking, crowding-distance-based diversity preservation, and elitist replacement—while incorporating adaptations required to handle the discrete, combinatorial nature of the problem. Classical NSGA-II maintains several dominance fronts and performs full non-dominated sorting across the entire population; however, in this discrete SSCB configuration space, dominated solutions offer no optimisation value. For this reason, the evolving population is restricted to the first (non-dominated) front, with crowding distance used to maintain diversity. This modification significantly improves computational efficiency while preserving the essential behaviour of NSGA-II in multi-objective search.

To improve the uniformity of exploration from the outset and mitigate premature convergence, the initial population was generated using a Sobol low-discrepancy sequence. An oversized initial pool (three times the nominal population size) was evaluated, and the feasible non-dominated individuals with the highest crowding distance were selected to form the first generation. Parent selection was performed using tournament selection biassed by crowding distance, followed by crossover and mutation (with a mutation rate of 0.01). Each design encoded the top-switch, bottom-switch, and heatsink selections as discrete indices, with decoding performed during evaluation.

An external Pareto archive was maintained throughout the optimisation, storing all non-dominated solutions discovered across generations. The GA used a population of 240 individuals, evolved over 200 generations, corresponding to a computational budget of approximately 2000 design evaluations. Fitness evaluation employed the same multi-objective function used for the other metaheuristic methods, simultaneously minimising conduction loss and component cost.

Overall, this NSGA-II-inspired GA provides a practical and computationally efficient approach for exploring the high-dimensional discrete SSCB design space, while retaining the key advantages of established multi-objective evolutionary algorithms.

3.2. Particle Swarm Optimisation

For comparative analysis, PSO was implemented. Each particle encoded a complete SSCB configuration using a discretised representation of the design variables. Although PSO is inherently formulated for continuous spaces, particle positions were mapped to valid component indices via rounding, ensuring compatibility with the discrete design library. The same multi-objective fitness function (minimising conduction power loss and material cost) was used as for the other algorithms. Particle velocities were updated using the standard PSO equations with inertia and cognitive/social terms, with parameters set to , , and . A swarm of 8 particles was evolved over 249 iterations, corresponding to a maximum of approximately 2000 design evaluations.

3.3. Grey Wolf Optimisation

The third metaheuristic applied was GWO, selected for its leadership hierarchy model and its balance between exploration and exploitation. Each grey wolf encoded a complete SSCB design. The best three candidates in each iteration were designated as the alpha, beta, and delta wolves, guiding the position updates of the remaining agents. Continuous position updates were again discretised by rounding to the nearest valid component indices. A pack of 20 wolves was evolved over 120 iterations, with each iteration updating all agents and evaluating the corresponding SSCB designs under the same multi-objective fitness function as the other methods.

3.4. Ant Colony Optimisation

ACO was included as a discrete probabilistic baseline algorithm, given its natural suitability for categorical decision problems. In this implementation, each ant constructs a complete SSCB design by selecting one top-switch configuration, one bottom-switch configuration, and one heatsink. These selections are sampled from pheromone-weighted probability distributions defined independently for each decision stage.

Pheromone tables for the top switch, bottom switch, and heatsink were initialised uniformly and updated iteratively using standard ACO mechanisms. At each iteration, eight ants generated candidate designs according to sampling probabilities proportional to , where denotes pheromone intensity, and represents heuristic desirability (set to 1 in this work). Following evaluation, pheromone evaporation was applied to prevent stagnation, and reinforcement was added from both the non-dominated solutions of the current iteration and an elitist deposit derived from the best design in the global Pareto archive. This elitist reinforcement served to strengthen promising design paths across iterations.

The ACO procedure was executed for 120 iterations, ensuring consistency with the computational effort allocated to the other metaheuristic baselines. While the algorithm efficiently navigated the discrete decision structure, its relatively small colony size and lack of additional heuristic guidance limited its ability to approximate the true Pareto front in this high-dimensional combinatorial setting.

3.5. Gorilla Troops Optimisation

GTO was implemented due to its strong reported performance in discrete and mixed-integer search spaces. In this method, each gorilla encodes a complete SSCB configuration by representing the top switch, bottom switch, and heatsink as a three-dimensional continuous position vector. Positions are subsequently discretised through index mapping to ensure valid component selections.

The optimisation process is guided by a social hierarchy model that balances exploration and exploitation. In each iteration, the best non-dominated solution in the external Pareto archive is designated as the silverback, providing a strong directional influence. Gorillas perform one of two behaviour modes:

- i.

- exploration, involving migration towards randomly selected design regions and movement influenced by other troop members; and

- ii.

- exploitation, characterised by movement toward the silverback and local competitive perturbation around high-quality solutions.

A linearly decreasing control parameter progressively shifts the algorithm from exploration toward exploitation as iterations advance.

The GTO implementation used a population of 20 gorillas and was executed for 120 iterations, matching the computational budget of the other algorithms. After each iteration, the newly evaluated solutions were merged with the external Pareto archive, ensuring elitist preservation of high-quality designs. Overall, the approach proved effective at navigating the discrete SSCB design space, demonstrating strong convergence and broad Pareto-front coverage.

4. Results

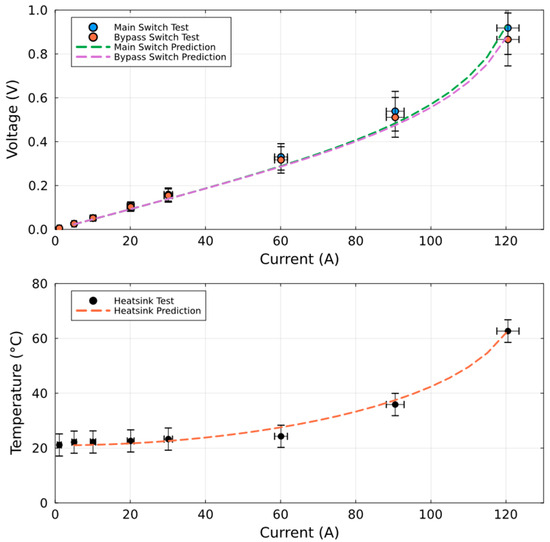

For the validation of the electrothermal model, the SSCB prototype was experimentally characterised and compared with predictions, as shown in Figure 5. The upper plot presents the voltage across the main and bypass switches, while the lower plot shows the steady-state heatsink temperature. In both cases, the dashed lines represent model predictions, and the symbols represent measured data. Across the full current range, the model reproduced the measured behaviour with strong agreement. The largest discrepancy occurred at 90 A, where the predicted case temperature differed from the measurement by only 1.4 °C and the voltage predictions deviated by less than 65 mV. These small absolute differences are well within the combined measurement uncertainty and expected thermal variation, confirming that the model is sufficiently accurate to serve as the foundation for optimisation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of measured data from the SSCB prototype with model predictions for the voltage across the main and bypass switches (top) and the steady-state heatsink temperature (bottom). The current shown is the total current through the SSCB (not per device). Error bars represent the combined effects of instrument measurement uncertainty and potential thermal variation during the experiment. Across the full current range, deviations between measurement and model were limited to <65 mV in voltage and <2 °C in temperature.

The key parameters used for the GA optimisation are detailed in Section 3. To provide a reference benchmark, the full design space was first analysed using a brute-force approach. This exhaustive evaluation of all design options required approximately 14 minutes of simulation time. As outlined in Section 2, each solution was tested for feasibility by enforcing the thermal constraint that the junction temperature, Tj, must not exceed 70% of Tjmax. For a total current of 120 A and an ambient temperature of 25 °C, the brute-force analysis examined 1,137,150 candidate designs, of which 20,375 (1.8%) were deemed feasible. To enable fair comparison, the optimisation algorithms (ACO, GA, GTO, GWO, and PSO) and the random selection baseline were each limited to a maximum of 2000 simulation calls. Under these conditions, the total runtime of all heuristic approaches remained under 5 s, in stark contrast to brute-force calculation.

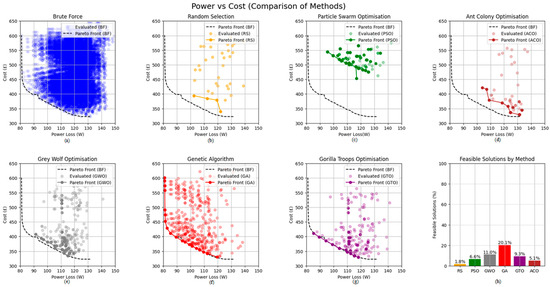

The results from the brute-force evaluation and a representative set of optimisation runs are shown in Figure 6. The brute-force analysis provides the complete true Pareto front of the design space, which is reproduced on all subplots (black dashed line) to support direct comparison with the optimisation methods. The examples shown for each optimiser correspond to one typical run; however, because all metaheuristics are stochastic, individual runs may vary. A full statistical comparison across 100 independent runs is therefore presented later in Section 4.1 using multiple performance metrics.

Figure 6.

(a) Graphs showing Pareto plot of brute force analysis (1,137,150 points). (b–g) Graphs showing typical Pareto plots for each of the optimisation algorithms used (~2000 evaluations per method). (h) Graph of the number of feasibility solutions found. Note that the total cost refers only to the materials cost of the MOSFETs plus the heatsink.

The random selection (RS) baseline (yellow) yields a sparse scattering of solutions, with its Pareto front lying far from the brute-force reference. The Particle Swarm Optimisation method (green) displays improved coherence due to information sharing between particles but remains significantly hindered by the discrete nature of the SSCB design space, resulting in limited coverage and a clear mismatch with the true Pareto front. The Grey Wolf Optimisation method (grey) performs noticeably better, with the leadership hierarchy enabling more structured exploration and improved proximity to the optimal region, though variability remains evident.

The two best-performing methods, GA and GTO, show markedly superior behaviour. The GA (red) produces a dense cluster of high-quality solutions that closely trace the true Pareto front, offering excellent alignment with the global trade-off between conduction loss and cost. The GTO algorithm (purple) also provides strong performance, effectively capturing the curvature of the Pareto boundary and achieving broad coverage of the feasible region, albeit with greater spread than GA. In contrast, the ACO method (brown) exhibits limited exploration and comparatively weak convergence toward the optimal region.

The proportion of feasible designs found within the 2000-evaluation budget reinforces these observations (Figure 6, bar chart). RS identifies 1.8% feasible designs, consistent with the brute-force baseline (1.8%). PSO improves this to 6.0%, GWO to 11.6%, and GTO to 9.3%. ACO achieves 5.1%. The GA identifies the highest proportion of feasible solutions at 20.1%–more than double the next best method.

The close agreement between the GA-derived Pareto front and the brute-force reference demonstrates that high-quality characterisation of the design space can be achieved with substantially lower computational cost. In this study, evaluating all 1.14 million brute-force designs required approximately 14 min, whereas GA reached a comparable characterisation in around 5 s—an improvement of more than two orders of magnitude. As component libraries scale, or as the number of in-parallel MOSFET combinations increases, this disparity grows even further. Consequently, brute-force parameter sweeps are only feasible for very small and rapidly solvable problems, while effective exploration of realistic power-electronic design spaces requires the use of optimisation algorithms such as GA and GTO.

4.1. Discussion of Optimisation Algorithm Performance

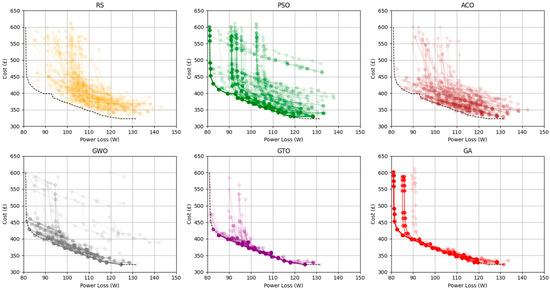

Before presenting quantitative performance metrics, Figure 7 provides a visual illustration of the variability and characteristic behaviour of each optimisation method across multiple runs. Each subplot in Figure 7 overlays the Pareto fronts obtained from 100 independent executions of the respective algorithm, highlighting the inherent stochasticity of metaheuristic methods. The spread, clustering, and general shape of these aggregated fronts give an initial qualitative indication of convergence quality, robustness, and sensitivity to randomness. However, while such visualisations help convey overall tendencies, they are insufficient for rigorous comparison on their own.

Figure 7.

Graphs showing Pareto fronts of total cost versus power loss, where the method has been repeated 100 times for each optimisation algorithm. Note that the total cost refers only to the materials cost of the MOSFETs plus the heatsink. The black dashed line in each plot represents the PF from the BF analysis.

To objectively compare the performance of different optimisation algorithms, several established Pareto-front quality metrics were used.

- Hypervolume (HV): quantifies the volume dominated by the Pareto front, reflecting overall solution quality and coverage (higher = better).

- Generational Distance (GD) and Inverted GD (IGD): measure how close the obtained front lies to the true Pareto front (lower = better).

- Hausdorff Distance (HD): captures the maximum deviation between the obtained and true fronts (lower = better).

- Overlapping Points (OP): indicates how many of the benchmark Pareto solutions are rediscovered (higher = better).

- Overall Spread (OS): assesses how well the algorithm reproduces the range of the objective space.

- Distribution Metrics (DM and SPnorm): evaluate the uniformity and spacing of points along the Pareto front (lower = better).

Given that metaheuristic algorithms are inherently stochastic, each optimisation method was executed 100 independent times. For each run, the resulting Pareto front was extracted, and the above metrics were computed. The final analysis is therefore based on the mean and standard deviation across these 100 runs, providing a robust statistical characterisation of each algorithm’s performance and variability.

For benchmarking, the BF method is used as the gold-standard reference, since it exhaustively explores the entire design space and therefore provides the true Pareto front. The RS method is included as a non-optimising baseline, illustrating the performance one would expect without any guided search.

Table 2 summarises the statistical performance of each optimisation method across all evaluated quality metrics. For every algorithm, the metrics were computed for 100 independent optimisation runs, and the table presents the mean and standard deviation for each indicator. This provides a clear, quantitative comparison of solution quality, robustness, and consistency across the different metaheuristic approaches, as well as against the BF reference and RS baseline.

Table 2.

Summary statistics (mean ± standard deviation) of Pareto-front quality metrics over 100 optimisation runs for each method. The brute-force (BF) front provides the reference benchmark.

4.2. Accuracy with Respect to the True Pareto Front (HV, GD, IGD, Hausdorff)

Across all performance metrics, a consistent pattern emerges regarding the relative quality of the Pareto fronts produced by the optimisation algorithms. The HV results show that the GA delivers the most complete reconstruction of the true design space, achieving the highest HV of all algorithms (1.032 ± 0.038, compared with the brute-force value of 1.063). GTO and PSO form a secondary tier, with HV values between 0.82 and 0.94, while ACO and random search exhibit substantially weaker performance with HV values below 0.72. These results suggest that GA not only approaches the true achievable region more closely than the other methods, but also maintains a stable approximation of that region across multiple runs.

The distance-based metrics reinforce this conclusion. GA yields the smallest Generational Distance (GD = 0.015) and Inverted GD (IGD = 0.026), indicating both excellent convergence to the true Pareto front and strong overall coverage of it. GTO is consistently the second-best performer, whereas PSO and GWO show noticeably larger IGD values, reflecting a tendency to miss sections of the front, particularly at the extremes. ACO and random search again perform the worst. The Hausdorff distance exhibits the same ranking, further confirming that GA offers the most accurate and reliable approximation of the brute-force results, followed by GTO, then PSO and GWO, with ACO and random search trailing significantly.

4.3. Coverage of the True Pareto Front (OP, OS)

A similar hierarchy is observed when examining coverage-based metrics. The Overlapping Points (OP), which measure the fraction of true brute-force Pareto-front points rediscovered by each optimiser, show GA identifying the greatest proportion of these solutions (0.52 ± 0.20). GTO recovers roughly a quarter of the true front, while GWO reaches around 0.14. In contrast, PSO, ACO, and random selection repeatedly fail to rediscover the key low-cost/low-loss “corner” solutions and achieve near-zero overlap. Visual inspection of the Pareto fronts mirrors these quantitative findings.

The Overall Spread (OS) metric, which reflects the extent to which each method spans the true Pareto region, again places GA as the most effective algorithm (OS = 0.77). GTO offers moderate coverage, with PSO and GWO performing similarly but less comprehensively. ACO and random search show very limited spread and fail to span the genuine front. Collectively, the coverage metrics demonstrate that GA provides the most complete and consistent reconstruction of the Pareto front, with GTO performing well but less comprehensively, PSO and GWO offering partial coverage, and ACO and random search proving largely ineffective.

4.4. Distribution and Diversity of PF Points (DM, SPnorm)

The metrics that evaluate the internal structure and smoothness of the recovered Pareto fronts further reinforce these trends. The GA achieves the lowest distribution metric (DM = 0.087), indicating that its solutions are evenly spaced and form a smooth, coherent front rather than a fragmented one. GTO and GWO also produce relatively orderly fronts, albeit with slightly higher DM values, suggesting minor irregularities but still generally well-distributed solutions. In contrast, both PSO and ACO exhibit substantially higher DM and normalised spread (SPnorm) values, reflecting noticeably uneven fronts, with clusters of points interspersed with sparse regions. As expected, random search performs worst, yielding a highly irregular and poorly structured front.

Taken together, these structural metrics show that even when PSO or ACO succeed in locating portions of the feasible region, the fronts they generate are noisy and lack consistent spacing. GA, by comparison, not only approximates the true Pareto front more accurately but also does so with a smooth and well-distributed set of solutions; this is an important characteristic for reliable multi-objective design exploration.

4.5. Final Ranking (Based on All Metrics)

To provide a clear comparison of algorithmic performance, all metaheuristics were ranked according to their accuracy, coverage, structural quality, and stability across 100 repeated optimisation runs. The following summary distils the collective behaviour of each optimiser, bringing together the full suite of performance metrics.

- 1st—Genetic Algorithm

- Highest overlap with the brute-force Pareto front

- Best accuracy across all distance metrics (GD, IGD, and Hausdorff)

- Second-best hypervolume, very close to the brute-force optimum

- Most stable behaviour across repeated runs

- Best front structure (lowest DM, smoothest SPnorm)

- 2nd—Gorilla Troops Optimisation

- Good accuracy and coverage of the feasible region

- Moderate spread and diversity across the front

- Some variability across runs, but still consistently strong

- 3rd—GWO/PSO (tie, with different strengths)

- PSO: reliably locates the mid-range of the Pareto front but struggles to rediscover true BF points

- GWO: moderate coverage and accuracy, but with noticeable variability

- Both clearly behind GA and GTO in all major metrics

- 4th—Ant Colony Optimisation

- Very low coverage of the true Pareto front

- High clustering and irregular spacing

- Among the lowest accuracy scores (only RS is worse)

- Random Search (baseline)

- Very poor accuracy and coverage, as expected

- Serves as a useful baseline: all optimisation algorithms outperform RS by a wide margin

Overall, the GA stands out as the most accurate, most reliable, and most consistent optimiser, repeatedly reconstructing the true Pareto front with high fidelity. GTO performs well as the strongest alternative, offering good convergence and reasonable stability. PSO and GWO deliver mid-level performance, capturing parts of the design space but failing to match the precision or consistency of GA/GTO. ACO and random search generally fail to recover the key regions of the Pareto front. This ranking reinforces that, for discrete combinatorial SSCB design, GA provides the most dependable optimisation performance.

5. Conclusions

Even for a relatively simple circuit topology and a modest set of device options, the optimisation of an SSCB presents a highly combinatorial challenge, with fewer than 2% of configurations proving feasible in brute-force exploration (for the specified current and temperature requirements). This study has shown that metaheuristic algorithms, particularly a GA, enhanced with Sobol sequence initialisation, are highly effective in navigating such discrete design spaces. The GA consistently recovered the Pareto-optimal trade-offs between conduction losses and cost, achieving a ~100-fold reduction in computational effort compared to exhaustive search. By integrating validated electrothermal models with optimisation, the methodology enables a faster, more efficient design process and unlocks performance gains offered by advanced semiconductor technologies.

The BF method, as expected, consistently achieved the optimal scores across all metrics, since it evaluates the entire design space and therefore reconstructs the true Pareto front. This provided an essential benchmark: the closer an optimisation algorithm’s performance is to BF, the more reliable and complete its coverage of the design space.

Among the metaheuristic approaches, the GA exhibited the strongest overall performance. It achieved high hypervolume, low generational distance, and the highest overlapping points among the heuristic methods, indicating that GA reliably finds both high-quality and diverse solutions. Its standard deviations are moderate, showing that performance was reasonably consistent across runs.

The GTO also performed well, particularly in generational distance and hypervolume, where it consistently ranks just behind GA. GTO demonstrates relatively low variability, which suggests that it converges in a stable and repeatable way, although its overlap score and overall spread indicate that it occasionally misses the extreme boundary solutions recovered by GA and BF.

The GWO delivered mixed results: while it performed moderately well on IGD and maintained reasonable hypervolume, it exhibited higher variability and weaker overlap with the true front. This suggests that GWO captures the central trade-off region effectively but tends to miss solutions at both ends of the spectrum.

The PSO showed visibly poorer performance, with substantially lower hypervolume and higher GD/IGD values. PSO tended to produce fronts that sit above the true Pareto front, meaning it often fails to recover low-power or low-cost boundary solutions. Its higher standard deviations also indicate that performance is strongly dependent on initialisation.

The ACO and RS methods expectedly displayed the weakest performance. ACO often failed to locate the true boundary front and exhibited relatively high GD/IGD values. RS, as a non-optimising baseline, achieved minimal overlap and the lowest HV, reflecting its inability to converge towards any meaningful front without guided search pressure. Despite this, RS was valuable as a control method, providing a baseline that demonstrated how much improvement the other algorithms achieve through structured optimisation.

Overall, the combination of metrics clearly shows that GA performed best, followed by GTO, then GWO, with PSO, ACO, and RS forming the lower tier. The BF front remains the gold-standard reference, and the closeness of GA’s and (to some extent) GTO’s metrics to BF confirms that these methods offer the most effective and reliable means of navigating the design space.

The approach becomes even more valuable as designs scale in complexity. For larger problem sizes, where the design space extends to billions of possibilities, brute-force or parameter-sweep methods are no longer practical. Increasing the number of objectives, such as efficiency, cost, volume, mass, ripple voltage, and thermal performance, further increases the complexity of the optimisation landscape and the difficulty of identifying high-quality trade-offs. Looking ahead, this methodology is being applied to the design of a solid-state transformer based on a dual-active-bridge converter, where optimisation must simultaneously consider numerous parameters, including device modules, switching frequency, leakage inductance, heatsink selection, capacitor sizing, and duty-cycle phases (α, β, φ). The multi-objective nature of this problem provides an ideal testbed for the proposed optimisation framework.

Importantly, the benchmarking methodology developed in this work, based on repeated runs, fixed evaluation budgets, and a comprehensive suite of Pareto-front quality metrics, offers a general transferable approach for assessing and comparing optimisation algorithms across a wide range of engineering design tasks. By accelerating iterative design, quantifying algorithmic performance in a rigorous and repeatable manner, and systematically balancing competing objectives, the framework provides a scalable and powerful tool for next-generation power-electronics design and other complex optimisation problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.L. and I.L.; methodology, A.P.L.; software, I.L.; validation, A.P.L., M.G., J.S., J.V.-N. and S.U.; formal analysis, A.P.L.; investigation, A.P.L.; resources, A.P.L., J.S. and M.G.; data curation, A.P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.L.; writing—review and editing, A.P.L., I.L., S.U., G.C.-L., J.V.-N., J.S. and M.G.; visualisation, A.P.L.; supervision, I.L., J.V.-N. and G.C.-L.; project administration, A.P.L.; funding acquisition, A.P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Innovate UK (project number: 160112).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of colleagues Konstantinos Floros, David Macdonald, and Mouhsine Fjer through the provision of MOSFET characterisation data (electrical and thermal). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Adam P. Lewis, Gerardo Calderon-Lopez, Ingo Lüdtke, Jason Vincent-Newson and Sahil Upadhaya were employed by the company Compound Semiconductor Applications Catapult. Authors Jas Singh and Matt Grubb were employed by the company Auriga Energy Limited. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimisation |

| BF | Brute Force |

| DM | Distribution Metric |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GD | Generational Distance |

| GTO | Gorilla Troops Optimisation |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimisation |

| HD | Hausdorff Distance |

| HV | Hypervolume |

| IGBT | Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor |

| IGD | Inverted Generational Distance |

| JFET | Junction Field Effect Transistor |

| MOSFET | Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor |

| NH | Number of heatsink models considered |

| NM | Number of MOSFET models considered |

| NS | Total number of switch configurations |

| NTOTAL | Total number of design combinations |

| OP | Overlapping Score |

| OS | Overall Spread |

| PF | Pareto Front |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimisation |

| RDSon | On-resistance between the drain and source |

| RS | Random Selection |

| Rth | Thermal resistance |

| Rth_jc | Junction-to-case thermal resistance |

| SiC | Silicon Carbide |

| SPnorm | Normalised Spread |

| SSCB | Solid-State Circuit Breaker |

| TIM | Thermal Interface Material |

| Tj | Junction temperature |

References

- Pilvelait, B.; Gold, C.; Marcel, M. A High Power Solid State Circuit Breaker for Military Hybrid Electric Vehicle Applications. In SAE Technical Paper Series; National Defense Industrial Association: Arlington, VA, USA, November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, A.; Wang, Z.; Ortiz, M.U.; Yang, T.; Wheeler, P. Design Considerations for High-Voltage High-Current Bi-Directional DC Solid-State Circuit Breaker (SSCB) for Aerospace Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 23rd European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’21 ECCE Europe), Ghent, Belgium, 6–10 September 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; Vemulapati, U.; Torresin, D.; Arnold, M.; Rahimo, M.; Antoniazzi, A.; Raciti, L.; Pessina, D.; Suryanarayana, H. 1MW bi-directional DC solid state circuit breaker based on air cooled reverse blocking-IGCT. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium (ESTS), Old Town Alexandria, VA, USA, 21–24 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-V.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Nguyen, Q.-T.; Bui, V.-H.; Su, W. Optimal Design Parameters for Hybrid DC Circuit Breakers Using a Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm. Algorithms 2022, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corea-Araujo, J.A.; Martinez-Velasco, J.A.; Magnusson, J. Optimum design of hybrid HVDC circuit breakers using a parallel genetic algorithm and a MATLAB-EMTP environment. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2017, 11, 2974–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, S.A.; Agamy, M.; Li, Z.; Losee, P. Electro-thermal Design of MV SiC JFET Based Solid State Circuit Breakers. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 10th Workshop on Wide Bandgap Power Devices and Applications (WiPDA), Charlotte, NC, USA, 4–6 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Rana, A.S. Protection and Optimal Relay Co-ordination in Microgrid Using FCL. In Proceedings of the Conference on Smart Power Control and System Protection, Rourkela, India, 19–21 July 2024; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10674781 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Malyna, D.V.; Duarte, J.L.; Hendrix, M.A.M.; van Horck, F.B.M. Multi-objective optimization of power converters using genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion, 2006. SPEEDAM 2006, Taormina, Italy, 23–26 May 2006; pp. 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Xu, X.; Xu, J. Grey Wolf Optimizer With a Novel Weighted Distance for Global Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 120173–120197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjafari, M.; Balog, R.S. Survey of modelling techniques used in optimisation of power electronic components. IET Power Electron. 2014, 7, 1192–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ela, A.A.A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Shaheen, A.M.; Ellien, A.R. Review on active distribution networks with fault current limiters and renewable energy resources. Energies 2022, 15, 7648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, E.; Espejo, E.B.; Enríquez, A.C. Metaheuristics Algorithms in Power Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-030-11593-7.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Gao, J.; Yuan, H.; Yang, A.; Rong, M. An Interruption Overvoltage Estimation Method With Improved Swarm Intelligence Algorithm for Modular DC Circuit Breakers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 73, 3504911. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10356152 (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Karthika, R.; Kumar, V.S.; Eswaran, T. Grey wolf optimization based PI controller to maintain constant DC link voltage for improving the performance of shunt active filter. Bull. Polytech. Inst. Iaşi 2019. Available online: https://dspace.upt.ro/xmlui/handle/123456789/7023 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wang, F.; Shen, W.; Boroyevich, D.; Ragon, S.; Stefanovic, V.; Arpilliere, M. Design Optimization of Industrial Motor Drive Power Stage Using Genetic Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the 2006 IEEE Industry Applications Conference Forty-First IAS Annual Meeting, Tampa, FL, USA, 8–12 October 2006; pp. 2581–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sarker, R.; Elsayed, S.; Essam, D.; Siswanto, N. Large-scale evolutionary optimization: A review and comparative study. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 85, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, N.A.; Ali, Y.H.; Rashid, T.A. Advancements in Optimization: Critical Analysis of Evolutionary, Swarm, and Behavior-Based Algorithms. Algorithms 2024, 17, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, J. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Electromagnetic Release Based on Whale Optimization Algorithm—Particle Filtering. Energies 2024, 17, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, F.; Dinc, M.; Arikan, O. DG Optimization in Power Systems Considering Power Losses and CB Rating Violations. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM), Bochum, Germany, 11–13 June 2025; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/11061947 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Dorigo, M.; Maniezzo, V.; Colorni, A. Ant System: Optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. 1996, 26, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stützle, T. Ant Colony Optimization. Comput. Intell. Mag. IEEE 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, B.; Gharehchopogh, F.S.; Mirjalili, S. Artificial gorilla troops optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 5887–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, R.R.; Gaheen, M.A.; ElAziz, M.A.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Ewees, A.A. An improved gorilla troops optimizer for global optimization problems and feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 269, 110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, D.; Arevalo, P.; Ortiz, Y.; Jurado, F. Survey of Optimization Techniques for Microgrids Using High-Efficiency Converters. Energies 2024, 17, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Kamel, S.; Mohamed, A.W. Enhanced gorilla troops optimizer powered by marine predator algorithm: Global optimization and engineering design. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, M.; Musirin, I.; Othman, M. Ant Colony Based Optimization Technique for Voltage Stability Control. In Proceedings of the 6th WSEAS International Conference on Power Systems, Lisbon, Portugal, 22–24 September 2006; pp. 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Slimani, L.; Bouktir, T. An Ant colony optimization for solving the Optimal Power Flow Problem in medium-scale electrical network. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Electrical Systems, Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria, 9–11 May 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadanga, R.K.; Das, D.; Panda, S.; Mahapatro, S.R.; Kar, M.K.; Al Mansur, A.; Ustun, T.S.; Kalam, A. A Novel Modified Gorilla Troops Optimizer Algorithm for Interline Power Flow Controller-Based Damping Controller Design. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 43, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Rahimnejad, A.; Gadsden, S.A. A greedy non-hierarchical grey wolf optimizer for real-world optimization. Electron. Lett. 2021, 57, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, G.; Argumosa, P.; Correro, A.; Maellas, J. Proposal of a New Technique to Obtain Some Fuel Cell Internal Parameters Using Polarization Curve Tests and EIS Results. Energies 2021, 14, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Ming, W.; Li, W. Low-Loss Bidirectional Solid-State Circuit Breakers With Reliable Breaking Capability for Protecting DC Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 16118–16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A. Infineon OptiMOSTMPower MOSFET Datasheet Explanation. Appl. Note 2012, 3, 2012. Available online: https://www.infineon.com/dgdl/Infineon-MOSFET_OptiMOS_datasheet_explanation-AN-v01_00-EN.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Keysight. Digital Multimeters 34460A, 34461A, 34465A (6½ Digit), 34470A (7½ Digit). Keysight. Available online: https://www.keysight.com/gb/en/assets/7018-03846/data-sheets/5991-1983.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Fluke Corporation. Fluke 323/324/325 Clamp Meter Manual [UM R1 ENG]. May 2012. Available online: https://media.fluke.com/8297e9a4-c59b-45fe-9370-b10800c191e7_original%20file.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Pico Technology. TC-08 Data Sheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.picotech.com/download/datasheets/usb-tc-08-thermocouple-data-logger-data-sheet.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).