Abstract

As large language models (LLMs) improve in understanding and reasoning, they are increasingly used in privacy protection tasks such as de-identification, privacy-sensitive text generation, and entity obfuscation. However, these applications depend on an essential requirement: the accurate identification of personally identifiable information (PII). Compared with template-based PII that follows clear structural patterns, name-related PII depends much more on cultural and pragmatic context, which makes it harder for models to detect and raises higher privacy risks. Although recent studies begin to address this issue, existing work remains limited in language coverage, evaluation granularity, and the depth of error analysis. To address these gaps, this study proposes an error-driven framework that integrates diagnosis and intervention. Specifically, the framework introduces a method called Error-Driven Prompt (EDP), which transforms common failure patterns into executable prompting strategies. It further explores the integration of EDP with general advanced prompting techniques such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT), few-shot learning, and role-playing. In addition, the study constructed K-NameDiag, the first fine-grained evaluation benchmark for Korean name-related PII, which includes twelve culturally sensitive subtypes designed to examine model weaknesses in real-world contexts. The experimental results showed that EDP improved F1-scores in the range of 6 to 9 points across three widely used commercial LLMs, namely Claude Sonnet 4.5, GPT-5, and Gemini 2.5 Pro, while the Combined Enhanced Prompt (CEP), which integrates EDP with advanced prompting strategies, resulted in different shifts in precision and recall rather than consistent improvements. Further subtype-level analysis suggests that subtypes reliant on implicit cultural context remain resistant to correction, which shows the limitations of prompt engineering in addressing a model’s lack of internalized cultural knowledge.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in the reasoning and understanding capabilities of large language models (LLMs) [1] have led to their increasing use in privacy-preserving system workflows. In these systems, LLMs handle core functions such as de-identification [2], privacy-preserving text generation [3], and entity replacement or obfuscation [4]. However, these tasks depend on an essential requirement, which is the accurate identification of personally identifiable information (PII). If this core capability is lacking, all higher-level privacy-preserving tasks built upon it will be unreliable, resulting in security risks. Unlike templated PII such as phone numbers and email addresses, name-related PII serves as a direct link to identity while being highly dependent on cultural and pragmatic contexts, lacking a stable external format [5]. As a result, disambiguation failures are more likely to occur in real-world scenarios. This makes name-related PII both more privacy-sensitive and more effective in exposing limitations in structural and pragmatic reasoning. Recent studies have shown that LLMs perform poorly in recognizing such PII [5,6], showing that this issue requires urgent attention. This technical limitation also carries critical implications for regulatory compliance. Under frameworks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the accurate detection of PII is a prerequisite for fulfilling user rights such as the “Right to Erasure.” The inability of models to recognize culturally specific names therefore poses not just a performance issue but a direct legal risk in cross-border data processing. Consequently, rigorous evaluation of name-related PII recognition and the development of targeted improvement strategies have become important tasks in multilingual and context-sensitive privacy research.

However, although initial explorations have been conducted on this issue, existing studies still exhibit several limitations. First, existing benchmarks for evaluating PII recognition capabilities are predominantly centered on English [7,8,9,10]. Even when test data built on these benchmarks are translated, they may still fail to accurately reflect a model’s true performance in other languages due to embedded cultural biases and pragmatic differences. Second, most existing evaluation frameworks adopt coarse-grained labeling schemes [10,11,12], where “names” are typically treated as a single unified category to be recognized as a whole. This approach lacks fine-grained distinctions and capability decomposition for specific name types, such as localized foreign names, nicknames, and abbreviations, making it difficult to identify the model’s precise weaknesses. In addition, the most recent analysis of name-related PII recognition capabilities [6] was conducted under a “predefined error type plus verification” paradigm and is rarely guided by data-driven approaches. As a result, potential vulnerabilities within models may be overlooked. Finally, although a few studies in the Korean context attempt to categorize name-related PII into “names” and “nicknames” and recognize the performance limitations of current models in handling such tasks, the underlying causes of these limitations are not further analyzed, nor are effective strategies proposed for improvement [5].

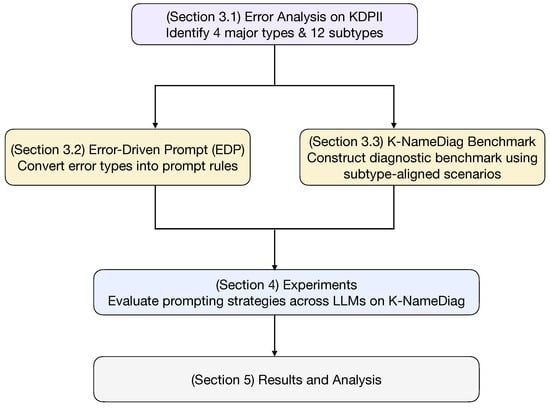

To address these limitations, an error-driven framework integrating diagnosis and mitigation is proposed in this study. The core contributions are summarized as follows: First, to address the gaps in Korean context, coarse-grained evaluation, and superficial analysis methods, a fine-grained taxonomy for Korean name PII is established. This taxonomy is derived from empirical recognition failures, effectively addressing the lack of a fine-grained classification in Korean PII research. Based on this taxonomy, the first Korean name PII diagnostic benchmark, K-NameDiag, is constructed. This benchmark, which comprises 12 fine-grained subtypes, is designed to expose model weaknesses that arise across different forms of Korean name-related PII. Second, to address the research gap characterized by a lack of deep causal analysis and effective mitigation strategies, an Error-Driven Prompt (EDP) methodology is proposed. This methodology, derived from a diagnosis of failure modes on the KDPII benchmark [5], translates diagnosed high-frequency failure modes into explainable and executable prompt intervention strategies. Finally, to validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, comparative experiments are conducted. The performance of the Baseline Prompt (BP), EDP, and Combined Enhanced Prompt (CEP) is evaluated across three leading commercial LLMs, namely Claude Sonnet 4.5, GPT-5, and Gemini 2.5 Pro. The experimental results indicate that EDP achieves consistent cross-model improvements in F1-score, precision, and recall compared to the baseline. In contrast, the performance of CEP is unstable and inconsistent across models, which highlights the limitations of generic reasoning instructions when processing culturally specific contexts. Furthermore, the impact of different prompting strategies on all 12 fine-grained subtypes is analyzed. This analysis shows where EDP delivers clear gains in high-risk categories, while also indicating deeper limitations in current models that cannot be resolved through prompt engineering alone. Figure 1 shows the overall structure of our framework, linking the error taxonomy, prompt design, benchmark construction, and evaluation pipeline.

Figure 1.

Chapter map of the proposed framework.

2. Related Work

2.1. PII Detection Technologies

PII detection is a key task in information security and privacy protection, centered on accurately identifying and classifying sensitive entities in unstructured text [13,14].

2.1.1. Traditional NER-Based PII Detection Methods

Early approaches to the automatic detection of PII primarily rely on traditional named entity recognition (NER) techniques [7], which model the task as a sequence labeling problem. Within this paradigm, although methods such as the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [15] and Support Vector Machine (SVM) [16] are also applied, the Conditional Random Field (CRF) [17,18,19] has long been regarded as one of the most dominant and effective model in early PII detection, owing to its ability to overcome the label bias problem and integrate arbitrary lexical and contextual features efficiently.

Although CRF demonstrates competitive performance on several benchmark through the incorporation of handcrafted features, its methodological limitations become evident when confronted with the diversity and complexity of real-world data. Firstly, the performance of CRF shows a clear brittleness of handcrafted features and a limited ability to generalize. Feature engineering based on regular expressions is highly sensitive to non-standard formats such as phone numbers with varying delimiters or addresses containing typographical errors, which results in low recall [20,21]. At the same time, dictionary-based features fail to capture out-of-vocabulary entities such as nicknames, aliases, or rare personal names, and their maintenance as well as cross-domain adaptation, for example from healthcare to finance, is often costly and inefficient [22].

Another limitation lies in the restricted contextual scope and inherent ambiguity of traditional methods. The discriminative capacity of CRF is largely confined to a narrow local feature window, preventing it from effectively capturing the long-range or document-level dependencies that are important for disambiguating PII. As a result, CRF often fails to resolve deep contextual ambiguities that frequently occur in real-world PII detection. For example, a numeric sequence such as “0108011234” may represent a phone number (PII) or an order ID (non-PII), and common words like “Hope” or “Chase” can denote personal or organizational names (PII) in certain contexts but ordinary terms in others. Without the ability to leverage document-level semantic cues such as preceding mentions of “please call” or “my order number is,” CRF performs poorly in scenarios that require contextual reasoning for accurate identification [23].

2.1.2. Deep Learning and Language Model-Based PII Detection

To overcome the reliance of traditional CRF models on handcrafted features and limited contextual scope, research shifted toward deep neural networks. The Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)-CRF architecture [24,25] quickly became the new benchmark for PII detection, combining bidirectional LSTM layers that capture long-range dependencies with a CRF layer that enforces label consistency. This architecture eliminates the need for manual feature engineering. However, it still depends on large task-specific annotated data and learns linguistic representations from scratch, lacking the deep semantic knowledge gained from large-scale pretraining.

The subsequent paradigm shift is driven by Transformer-based [26] pre-trained language models (PLMs). Models such as BERT [27] learn deep bidirectional contextual representations through large-scale self-supervised pretraining on unlabeled corpora. This pretraining–fine-tuning paradigm effectively addresses the limitation of BiLSTM architectures that learn linguistic representations from scratch. By fine-tuning on task-specific annotated datasets, PLMs such as RoBERTa [28] and DeBERTa [29] achieve state-of-the-art performance on NER benchmarks and excel at resolving deep contextual ambiguities. However, similar to their BiLSTM predecessors, this paradigm still heavily depends on large, high-quality labeled datasets for downstream tasks, which remains a major bottleneck in privacy-sensitive domains such as PII detection [30].

The recent paradigm shift is led by LLMs, which introduce the concept of in-context learning (ICL) [31]. Trained on trillions of tokens, LLMs encode extensive world knowledge and a wide range of linguistic regularities within their parameters, which in turn supports their zero-shot and few-shot reasoning performance. Studies show that, with carefully designed prompts, LLMs achieve competitive performance on NER and PII detection tasks without any gradient updates [32,33], theoretically mitigating the dependence on large-scale annotated datasets.

Despite the remarkable potential of LLMs, their robustness in PII detection remains underexplored. Existing studies are predominantly conducted on English-centric benchmarks [31,34], with only limited efforts extending to multilingual NER settings [35,36]. However, these studies typically focus on high-resource languages and standard entity types, leaving the performance, challenges, and failure modes of LLMs on culturally specific and unstructured non-English PII largely unexplored. For instance, PII such as names and nicknames that carry cultural attributes differ substantially from their English counterparts [5] in both structure and ambiguity. It remains unclear how LLMs can effectively identify such entities through prompt engineering. This study aims to address this research gap.

2.2. Benchmarks for PII Detection

The evaluation of PII detection models critically depends on high-quality and representative benchmarks. However, constructing such datasets poses substantial challenges due to privacy regulations, annotation costs, and cultural diversity.

2.2.1. English-Centric Benchmarks and Their Limitations

Currently, benchmarks for evaluating PII detection can be broadly divided into two categories. The first consists of general-purpose NER benchmarks, which are widely adopted due to their inclusion of PII-related entities such as PERSON and LOCATION. Representative examples include CoNLL-2003 [7] and MUC-7 [8]. However, these benchmarks are not originally designed for privacy protection and therefore lack high-risk structured PII types such as identification numbers, phone numbers, and email addresses.

The second category focuses on privacy protection and de-identification benchmarks. A well-known example is the i2b2/UTHealth 2014 De-identification Challenge [9], which provides medical records containing protected health information (PHI). More recent efforts, such as the AI4Privacy Dataset [10], include 17K unique, semi-synthetic sentences containing 16 types of PII by compiling information from jurisdictions including India, the UK, and the USA.

Although these benchmarks have played an important role in advancing the field, they share a common limitation, an English-centric bias. This bias manifests on two levels. First, the corpora are almost entirely composed of English texts. Second, the definitions, structures, and cultural semantics of PII are heavily influenced by Western-oriented paradigms. For instance, personal names typically follow a linear “first–last” structure, address formats adhere to English-speaking conventions, and culturally distinctive names are often confined to English contexts. While some researchers have attempted to construct benchmarks for low-resource languages by translating existing English datasets [37], such approaches fail to eliminate the underlying cultural bias. Machine translation cannot reproduce culturally authentic PII instances with distinct structural characteristics and contextual ambiguities, and may even amplify semantic distortions, leading to inaccuracies in cross-lingual evaluation.

2.2.2. The Gap in Korean PII Benchmarks

To address the above issues, the Korean NLP (Natural Language Processing) community has made several localized efforts, such as the AI Hub Korean SNS multi-turn dialogue data [38] and the KISTI Network Intrusion Detection Dataset known as NIDD [39]. The Korean SNS dataset consists of daily conversation texts collected under privacy and copyright agreements, while NIDD contains real-world security event logs from KISTI’s intrusion detection systems. However, both datasets are distributed in anonymized form and cover narrow, domain-specific content, making them unsuitable for training or evaluating fine-grained models that detect PII directly from raw text.

Therefore, in practice, researchers often resort to general-purpose NER benchmarks. Among them, KLUE-NER [40] serves as the de facto standard for Korean natural language understanding. However, its applicability to PII detection is notably limited, as it provides only a coarse-grained label “PS” (Person), which fails to capture the structural and semantic complexity of Korean personal names, such as full names, surnames, and aliases, across different contexts.

To address this gap, the recently introduced KDPII (Korean Dialogic PII Dataset) [5] represents an important advancement by establishing a structured classification system for Korean PII that includes more than thirty fine-grained labels. However, the authors of [5] explicitly acknowledge in their discussion that the baseline models perform poorly on culturally specific categories, particularly NAME and NICKNAME. More critically, although [5] identifies this core performance bottleneck, the study stops short of providing any diagnostic analysis of the failure cases. It does not investigate the linguistic or contextual types of names that lead to model errors, nor does it propose any targeted solutions.

Given that personal names represent the most direct and high-risk identifiers in PII detection, these unresolved performance blind spots expose a concrete and foundational research gap. The present study aims to fill this gap.

2.3. Enhancing LLM Performance via Prompt Engineering

As LLMs continue to advance in NLP, prompt engineering [41,42,43] has become an important and cost-effective model optimization approach. It improves task performance without modifying model parameters while enhancing adaptability, output consistency, and cross-context generalization [44].

Existing studies show that various prompt engineering strategies can substantially enhance the performance of LLMs, particularly in language understanding and information extraction tasks.

Zero-shot prompting [45] involves providing task instructions and input text directly to the model, allowing it to perform the task based on its pretrained knowledge. This method is simple and efficient for well-defined and semantically clear tasks.

User prompt: Identify PII in the text below.

Input: "My phone number is 010-1234-5678."

Output: PII (Phone Number)

Few-shot prompting [46] augments the instruction with a few input–output examples, allowing the model to infer the output pattern and format from context. This approach enhances performance on complex or ambiguous tasks.

User prompt: Detect PII in examples.

Ex1: "Tom lives in Seoul." → Name, Location

Now: "Contact me at abc1234@yonsei.ac.kr."

Chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting [47] introduces step-by-step reasoning before the final answer, encouraging logical inference and improving multi-step reasoning.

User prompt: Let’s reason step by step.

Input: "010-1234-5678" has digits and hyphens.

Output: PII (Phone Number)

Role-playing prompting [48] instructs the model to adopt a specific role during task execution, improving domain-specific accuracy and stylistic consistency.

User prompt: You are a privacy auditor.

Task: Identify all PII in this document.

However, as noted in [49], although these methods can guide reasoning, they lack the ability for reflection and error correction, which often causes models to repeat and reinforce existing mistakes. To address this limitation, a philosophy of Error Reflection has been proposed [49,50,51]. The core idea is that models should learn from their trajectories of failure and iteratively reflect on and revise their own behavior. In pioneering works such as [49], this “reflection” is dynamic, meaning that the LLM performs self-assessment of its outputs during runtime through automated generation mechanisms, autonomously producing feedback for iterative correction. While dynamic reflection is powerful, it increases reasoning cost and latency, and the quality of the model’s reflection itself is not controllable. However, in culturally specific tasks like name recognition (e.g., the inability to identify rare Korean surnames), the failure patterns tend to be highly predictable.

This leads to a more direct and controllable strategy: Static Error Reflection, which we refer to in this work as Error-Driven Prompting. The core idea is that human researchers pre-emptively perform the “error reflection” step by accurately analyzing and summarizing the model’s typical failure patterns, and then statically encoding the outcomes of these reflections into the prompt.

As discussed in Section 2.2, previous studies have shown that LLMs have limitations in recognizing culturally specific Korean NAME and NICKNAME PII [5], yet an attribution of these failure patterns remains largely unexplored. Building upon the principle of Static Error Reflection, this study proposes an integrated corrective prompting strategy that combines targeted few-shot examples with general reasoning-enhancing techniques such as CoT prompting and role-playing. The goal is to improve LLM performance in the high-risk and fine-grained task of Korean PII detection through deliberate and structured error-guided intervention.

3. Methodology

This section presents the research methodology aimed at identifying the challenges faced by LLMs in recognizing Korean name-related entities and proposing corresponding improvement strategies. We first propose a novel fine-grained diagnostic framework (Section 3.1), which theoretically deconstructs the underlying causes of model failures. Building upon the specific error patterns identified by this framework, we develop an error-driven prompt enhancement method (Section 3.2), which serves as the core of our mitigation strategy. Finally, to rigorously and fairly evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method, and to avoid bias introduced by testing directly on data used for analysis, we construct a targeted diagnostic benchmark, K-NameDiag (Section 3.3), specifically tailored for this task.

3.1. Building a Diagnostic Framework: From Errors to 12 Fine-Grained Subtypes

3.1.1. Constructing and Executing the Diagnostic Probe

As previously reported in [5], the recognition of unstructured, culturally-specific PII remains a considerable challenge for fine-tuned transformer-based models, with average F1-scores for Korean personal names and nicknames dropping to 0.78 and 0.59, respectively. However, how modern LLMs perform on this task, and the specific mechanisms underlying their failures, remain unexplored. To bridge this gap, we design a diagnostic probing experiment that examines the internal mechanisms of how models process, interpret, and misclassify Korean names and nicknames, aiming to move from surface-level performance analysis toward a mechanistic understanding.

The proposed diagnostic framework consists of three core components: a probing instrument, a stimulus design, and a subject set. This study employs GPT-4o as the diagnostic probing instrument, an LLM known for its stability and representativeness [52]. Subsequently, in the evaluation phase presented in Section 4, we utilize the latest GPT-5 to verify whether the prompts refined based on the error patterns of earlier models remain effective and generalizable in the new generation of models. The stimulus is designed as a BP, as shown in Appendix A. This prompt features a minimal structure and direct instructions, aiming to minimize external guidance and thereby expose the model’s inherent reasoning patterns and latent biases under a zero-shot setting.

The experimental subject set is derived from the original KDPII dataset [5] (an example of its organizational structure is shown in Appendix B), which encompasses 33 distinct PII types. From this benchmark, we select all dialogue samples annotated with PS_NAME or PS_NICKNAME labels. Given that the KDPII data is organized at the sentence level, we first perform text reconstruction for each selected dialogue sample: all sentence_form fields belonging to the same dialogue ID are concatenated in their original order to reconstruct the complete, coherent plain text dialogue. This process yields a subject set containing 2700 personal name entity instances and 1835 nickname entity instances.

The diagnostic process follows a strict experimental protocol. Each dialogue sample in the KDPII subset is individually processed using the BP through the GPT-4o API. All model outputs are fully retained without any filtering or manual modification, forming a diagnostic corpus that authentically reflects the model’s behavior in handling Korean personal names and nicknames.

3.1.2. The Diagnostic Process: From Qualitative Analysis to Pattern Induction

Building upon the diagnostic corpus constructed in the previous section, this study analyzes the errors made by the model in recognizing Korean personal names and nicknames. To extract interpretable patterns from seemingly scattered error instances, we adopt a bottom-up inductive analysis approach. This method does not predefine error types but allows patterns to naturally emerge from the data, thereby highlighting the model’s inherent vulnerabilities and reasoning biases in a data-driven manner. Compared with the previous study on English name recognition [6], this work employs a distinct analytical paradigm. While the prior study follows a top-down framework that evaluates model performance based on predefined error, our approach relies entirely on a data-driven inductive strategy, allowing error patterns to emerge directly from model predictions. This design minimizes the prior bias introduced by human-defined taxonomies and offers a more objective depiction of the model’s failures in recognizing Korean personal names and nicknames.

To ensure objectivity and consistency, this study conducts error analysis collaboratively by a team of six researchers. All members are native Korean speakers with interdisciplinary backgrounds in linguistics and information science. The analysis process follows a collaboration- and consensus-driven approach: each error instance is reviewed and categorized through team discussions, and the final classification is collectively determined. This procedure minimizes individual subjective bias as much as possible.

The analysis begins at a micro-level, involving a two-tier annotation of each error instance in the corpus. At the phenomenological level, we apply automated scripts to compare the model outputs with the gold standard. Based on the matching results, errors are automatically categorized into four types: false negatives (FN), false positives (FP), boundary errors, and label mismatches.

Subsequently, at the causal level, each automatically categorized error is assigned a causal hypothesis. This hypothesis is grounded in a linguistic analysis of the error, including its morphological, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic characteristics, in order to explain the underlying mechanisms of occurrence.

We then systematize these causal hypotheses into a set of challenge-oriented subtypes. Specifically, this systematization process follows the methodological principles of Grounded Theory, employing iterative coding to allow categories to emerge from the data rather than relying on predefined frameworks. The process involves repeated inspection and analysis of the error instances.

In the open coding stage, we examine each error and assign descriptive initial labels or “concepts” to capture its salient features and preliminary causes. Next, through axial coding, we explore relationships among these concepts, grouping semantically or causally related instances around emerging core phenomena such as structural segmentation failure or commonsense bias. Finally, during the selective coding stage, we refine and integrate the core categories into a coherent and explanatory framework. We continuously compare newly encountered error instances with the existing categories, validating and revising definitions until theoretical saturation is achieved, that is, when additional analysis no longer yields new core categories or substantial changes to existing ones.

Through this bottom-up inductive process, we identified twelve subtypes of Korean name-related entities. These subtypes are labeled NAME-S1 to NAME-S6 and NICK-S1 to NICK-S6, where “S” stands for subtype and the number indicates the index within each category. We further group these twelve subtypes into four macro categories, which together constitute the foundation of our diagnostic framework. The following describes each macro category and its corresponding subtypes in detail.

- Structural Decomposition Failure represents errors where the model fails to correctly segment compound name structures, reflecting a lack of morphological and syntactic decomposition ability. The phenomenon is particularly influenced by Korean cultural conventions, where personal names are frequently combined with occupational titles, honorifics, or intimate suffixes, which increases the difficulty of boundary identification for the model.

- (a)

- NAME-S3 (Composite Entity: Name + Position).In Korean discourse, personal names are often attached to professional titles, forming conventionalized expressions such as Park gwajang (manager) or Lee sajang (company president). This “Name + Position” pattern is common in workplace communication and conveys clear signals about a person’s social identity. The model often misinterprets the entire phrase as an inseparable lexical unit, failing to capture the hierarchical structure of the compound.

- (b)

- NAME-S4 (Name + Suffix).Korean names frequently appear with politeness or intimacy suffixes such as -ssi (neutral polite marker), -nim (formal honorific), or -ah/-ya (intimate address form). Examples like Yoon-jung-ssi or Jin-ah illustrate how these suffixes encode social distance within Korea’s speech-level hierarchy. The model’s inability to isolate the core name while recognizing these morphological attachments indicates its limited understanding of Korean sociolinguistic conventions.

- Common-sense Bias refers to a category of errors that arise from the model’s overreliance on “world knowledge” acquired during pretraining, while neglecting contextual cues within discourse. As a result, the model often fails to interpret culturally specific meanings. In Korean communication, it is common to use words with literal meanings as personal names or nicknames, a phenomenon of “semantic overloading” that poses unique challenges for language models.

- (a)

- NAME-S6 (Highly Ambiguous Noun-like Name).Words such as Nara (meaning “nation”) or Uju (meaning “universe”) function both as ordinary nouns and as personal names in Korean usage. The model often activates the literal semantics of such words rather than recognizing their referential role, which indicates its difficulty in handling polysemous name forms grounded in cultural conventions.

- (b)

- NICK-S1 (Common Noun Type).In Korean culture, nicknames derived from everyday nouns such as foods, animals, or objects are frequently used to express intimacy or humor. Examples include Strawberry, Puppy, or Tteok (rice cake). The model tends to interpret these words according to their literal meanings, overlooking their pragmatic function as interpersonal references. This reflects its lack of sensitivity to cultural metaphor and affective expression in nickname usage.

- Recognition Failure refers to a category of errors involving unconventional entities that fall outside the model’s learned representation space, constituting another major source of false negatives (FN). This phenomenon is particularly prominent in Korean contexts, where diverse forms such as foreign names, online identity markers, and colloquial nicknames are widespread.

- (a)

- NAME-S2 (Prototypical Korean Full Name).Standard Korean full names typically follow a one-syllable surname and two-syllable given name structure (e.g., Kim Minji, Park Jisoo), which is the most common and canonical naming convention in Korean. Despite this high prototypicality, the model still fails to recognize such names when explicit contextual or syntactic cues are absent. This indicates the model’s limited morphological sensitivity to Korean naming structures and weak representational capacity for encoding canonical name patterns. At a deeper level, this error reflects insufficient coverage and diversity in Korean-specific training data, exposing structural limitations in the model’s ability to process basic named entity recognition in low-resource languages.

- (b)

- NAME-S5 (Foreign/Atypical Name).Names such as Ahmed or Mika do not conform to Korean phonological or orthographic conventions. The increasing globalization of Korean society has made such foreign names common in workplaces and media, yet the model’s poor recognition performance indicates limited cross-cultural adaptability.

- (c)

- NICK-S2 (ID/Creative Type).In Korean online culture, hybrid nicknames combining Korean, English, and numerals are widely used, such as minsu123 or cute_jin. These creative and personalized forms challenge the model’s ability to detect boundaries and identify entities accurately, reflecting limitations in recognizing culturally specific digital naming patterns.

- (d)

- NICK-S4 (Phonetic/Affectionate Variation Type).In spoken Korean, affectionate nicknames are often formed through abbreviation, phonetic alteration, or reduplication. For instance, suffixes such as -i or -sseu are added to convey intimacy or endearment. The model fails to capture these phonological and morphological variations, which suggests its cognitive limitation in processing colloquial forms shaped by sociolinguistic intimacy conventions.

- Fine-grained Conceptual Confusion refers to a category of errors that reflect the model’s inability to distinguish between semantically similar but pragmatically different expressions, resulting in frequent label mismatches or false positives (FP). This phenomenon is closely related to the complexity of Korean address systems, in which the referential function of an expression often depends on relational roles, communicative context, and social distance.

- (a)

- NICK-S3 (Relational Reference Type).When a relational expression includes an explicit name anchor (e.g., Minsu’s mom, Chulsoo’s brother), it typically refers to a specific individual in real-world Korean discourse, functioning as a stable referential identifier. Therefore, such expressions can be considered personally identifiable information (PII) or name-like nicknames. In contrast, relational expressions without a name anchor (e.g., “my mom,” “your brother,” “the kid’s mom”) merely indicate a relational role or category rather than a specific individual, and thus are not PII. The model often fails to capture this pragmatic distinction: sometimes it extracts only the name while ignoring the relational term (false negative), and sometimes it incorrectly labels non-referential relational expressions as PII (false positive). These inconsistencies indicate that the model lacks a fine-grained understanding of the cultural pragmatics that govern relational reference in Korean, resulting in unstable and context-insensitive behavior.

- (b)

- NICK-S5 (Descriptive/Characteristic Type).Descriptive nicknames in Korean are often derived from personal appearance, personality, or behavioral traits, such as Bossy, Shorty, or Smiley. Depending on the social group and interactional context, these expressions can function either as temporary descriptions or as stable identity markers. The model frequently fails to infer this pragmatic boundary, misclassifying evaluative adjectives or descriptive terms as permanent identifiers. This suggests a lack of sensitivity to the social-pragmatic cues that distinguish contextual characterization from stable personal reference.

- (c)

- NICK-S6 (Foreign-style Nicknames).These expressions refer to foreign-style nicknames derived from non-Korean naming conventions, often exhibiting phonological patterns that differ from standard Korean forms. Because of their atypical structure, models frequently misinterpret them as generic foreign words or non-PII expressions rather than person-specific identifiers.

- (d)

- NAME-S1 (Independent Surname).In Korean discourse, surnames such as Kim, Park, and Lee are commonly used as abbreviated forms of address, particularly in familiar or workplace contexts. When combined with politeness suffixes like -ssi (neutral politeness) or -nim (formal politeness), these forms usually indicate a specific referent and therefore qualify as PII. However, when used generically (e.g., “many Kims,” “a certain Park”), they lose referential specificity. The model exhibits inconsistent behavior in handling such cases: sometimes it omits surnames that carry clear referential intent (false negatives), while at other times it overgeneralizes and mislabels non-specific mentions as PII (false positives). This inconsistency shows the model’s limited understanding of the Korean politeness and address system, as well as its difficulty in modeling pragmatically driven referentiality.

These error patterns directly inform the design of the Error-Driven Prompts (EDP), which are detailed in Section 3.2.

3.2. Error-Driven Prompt Engineering

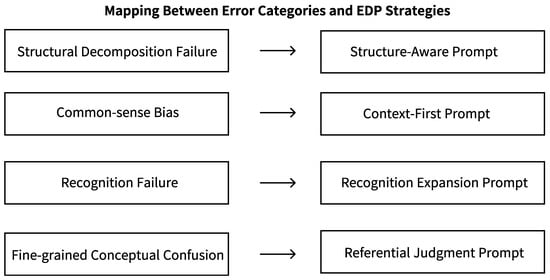

This section introduces the EDP method. We convert the error patterns identified in Section 3.1 into specific instructions designed to fix them. Figure 2 provides a high-level mapping between the four major error categories and their corresponding EDP strategies.

Figure 2.

Mapping between four error categories and their corresponding EDP strategies.

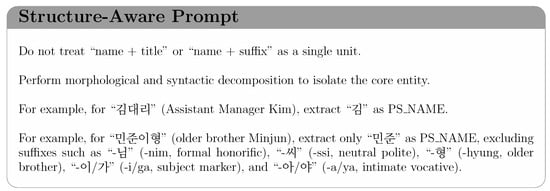

Structure-Aware Prompt directly targets Category 1 (Structural Decomposition Failure). This prompt corrects the model’s tendency to treat compound entities as indivisible wholes by providing explicit instructions for structural parsing and decomposition. This prompt is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Illustration of Structure-Aware Prompt for Structural Decomposition Failure.

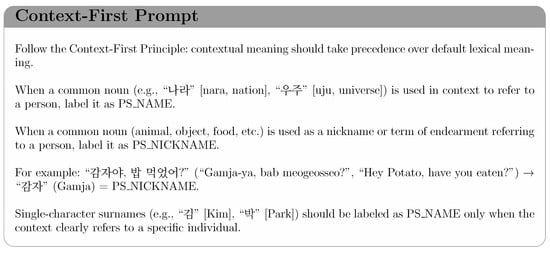

Context-First Prompt targets Category 2 (Common-sense Bias) and aims to correct the model’s tendency to rely excessively on default lexical meanings while neglecting contextual information. To address this issue, the prompt introduces the Context-First Principle, guiding the model to prioritize contextual cues when interpreting meaning. This prompt is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Illustration of Context-First Prompt for Common-sense Bias.

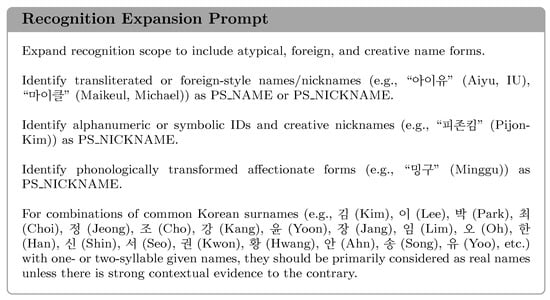

Recognition Expansion Prompt targets Category 3 (Recognition Failure). It instructs the model to expand its recognition scope to include nonstandard, foreign, and creative forms, thereby overcoming the limitations of an overly narrow and conventional representation space. This prompt is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Illustration of Recognition Expansion Prompt for Recognition Failure.

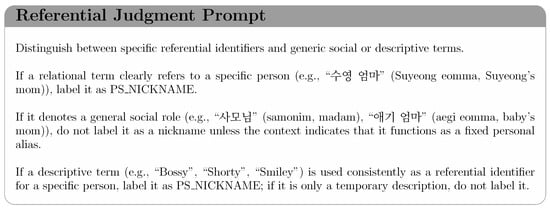

Referential Judgment Prompt targets Category 4 (Fine-grained Conceptual Confusion). It provides a set of nuanced heuristic rules designed to guide the model in pragmatically distinguishing between specific referential identifiers and general or descriptive terms. This prompt is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Illustration of Referential Judgment Prompt for Fine-grained Conceptual Confusion.

Overall, the error-driven prompting methodology proposed in this section translates the qualitative insights derived from the diagnostic framework into a set of actionable, rule-based intervention mechanisms. This prompt suite provides an interpretable approach that aligns model reasoning with the culturally specific challenges of Korean Name PII detection, thereby achieving a methodological integration from empirical diagnosis to strategic optimization.

3.3. K-NameDiag: A Diagnostic Benchmark for Name and Nickname Disambiguation

To rigorously and objectively evaluate the effectiveness of our EDP, it is essential to conduct the assessment on an independent benchmark dataset, thereby avoiding the issue of circular validation that could arise from reusing the original analytical corpus (KDPII). However, existing general benchmarks contain too few samples that exhibit the high cultural specificity and semantic ambiguity necessary for a valid stress test. To address this limitation, we construct a new, independent diagnostic benchmark, referred to as K-NameDiag. This benchmark specifically focuses on the high-risk failure patterns identified in the preceding analysis and is designed to accurately measure the real-world effectiveness of our prompting strategy in addressing these specific weaknesses. The benchmark is developed through three stages: constructing a high-difficulty lexicon based on diagnostic failure patterns, generating adversarial dialogues via a specific pairing protocol, and conducting expert refinement and independent verification to ensure data quality.

3.3.1. Stage 1: Construction of the High-Difficulty Entity Lexicon

In constructing the high-difficulty entity lexicon, this study first faces a key methodological question: whether PII entities that appear in the original corpus (KDPII) should be excluded. We argue that for the specific task of Korean PII recognition, adopting a mechanical “decontamination” strategy, which simply removes all entities that appear in KDPII, does not contribute to a realistic evaluation of model capability and may introduce bias at the methodological level. The reason lies in the high concentration of the Korean naming system, where family names, given names, and nicknames exist within a limited combinatorial space and are highly repetitive in actual language use. If all high-frequency entities from KDPII are excluded, the resulting benchmark deviates substantially from the authentic name distribution in Korean society, thereby weakening the ecological validity of the study.

Based on this consideration, we establish a core design principle for the Korean name recognition task: the essential challenge lies not in lexical novelty, meaning whether the model has seen a particular name before, but in contextual novelty, meaning whether the model can accurately disambiguate and classify the same name in newly constructed contexts that are pragmatically complex and adversarial in nature. Accordingly, the objective of this stage is to extract from KDPII those lexical items that are both highly representative and maximally challenging, serving as the core semantic resources for constructing newly contextualized samples.

The construction process proceeds as follows:

- High-Difficulty Entity Pool Curation: As described in the diagnostic analysis presented in Section 3.1, we quantitatively identify instances of false negatives and false positives in the KDPII dataset. From these diagnostic results, we extract all PII entities that cause recognition failures to form an Error Entity Pool.

- Lexicon Construction based on Frequency and Coverage: From this Error Entity Pool, we curate the final lexicon according to two core criteria:

- High-Frequency First: We prioritize entities with the highest error frequency in the diagnostic analysis. This design inherently guarantees the “high-difficulty” nature of the lexicon, as it directly targets the model’s most common vulnerabilities.

- Ensuring Coverage: To ensure diagnostic comprehensiveness, we conduct expert review and supplementation to confirm that all twelve challenge types, including rare but semantically complex cases, are adequately represented in the lexicon.

Through this curation process, we construct a high-difficulty lexicon containing 1375 unique name-related entities, which serves as the core semantic resource for the subsequent stage of contextual dialogue generation.

3.3.2. Stage 2: Dialogue Generation via Adversarial Pairing Protocol

We adopt a multi-turn dialogue format as the core structure of our benchmark because many challenge types identified in our diagnostic framework, such as name plus suffix combinations and relational references, are inherently conversational in nature. The ambiguity of these entities heavily depends on cross-turn context, sociopragmatic cues, and informal linguistic patterns, all of which are largely absent in static text. Consequently, the dialogue format provides the most ecologically valid medium for embedding these high-difficulty entities and establishes a rigorous testing environment for evaluating the model’s reasoning capability.

To embed the 1375 high-difficulty entities into the dialogue contexts, we adopt an adversarial pairing strategy. The core objective of this strategy is to encourage the model to perform high-level semantic disambiguation during evaluation. To this end, we design a Diagnostic Pairing Protocol that combines entities from different subtypes across the twelve challenge categories to construct adversarial pairs or triplets, thereby maximizing semantic confusion. This combinatorial approach ensures that our benchmark comprehensively covers potential confusion boundaries and diverse contextual scenarios across the twelve challenge types, enhancing the overall diagnostic comprehensiveness and robustness of the evaluation.

Each specific set of entities derived from these adversarial combinations is formatted into a structured prompt template. The template instructs the text generator, GPT-4o, to (1) incorporate all target entities within the dialogue, (2) produce an 8–12-turn conversation that maintains contextual coherence, and (3) ensure that all entities are naturally embedded into the dialogue so that their classification remains genuinely challenging and semantically ambiguous. The complete English prompt template used for dialogue generation is shown in Appendix C. Using this method, a total of 3000 candidate dialogues are generated.

3.3.3. Expert Refinement and Independent Quality Verification

To ensure the data quality of the new benchmark, all 3000 model-generated dialogues undergo a two-stage human review and refinement process. This process is conducted by six researchers with backgrounds in linguistics and information science, with a distinction between the roles of editing and verification.

In the first stage, four researchers conduct a comprehensive review and annotation of all 3000 dialogues. They follow a structured evaluation guideline (see Appendix D) to ensure consistency throughout the review and editing process. This stage comprises three core tasks. First, text quality review and refinement: the researchers assess (a) the linguistic naturalness and coherence of each dialogue, and (b) the contextual appropriateness of the target entity usage. If a dialogue is deemed “unacceptable” according to the criteria in Appendix D, the responsible researcher performs the necessary edits to improve clarity and expression while strictly adhering to the principle of preserving the intended ambiguity, until the dialogue reaches the “acceptable” standard. Second, the researchers verify whether the generator has correctly incorporated the target entities as specified in the Stage 2 prompt. Finally, the researchers conduct a thorough scan of each dialogue to identify and annotate any additional PIIs inadvertently generated by GPT-4o.

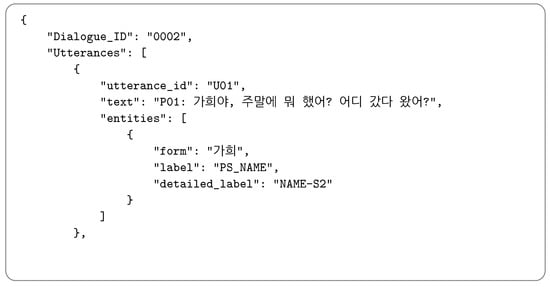

In the second stage, we perform an independent quality–consistency verification. Specifically, we randomly sample 300 dialogues (10%) from the 3000 items. These 300 samples are assigned to the remaining two core researchers, who did not participate in editing these particular items in Stage 1. Working independently and using the same evaluation guideline (Appendix D), the two researchers render a binary pass/fail decision for each sample, defined such that a sample passes only if it is judged acceptable on all four dimensions specified in Appendix D. We then compare the two sets of judgments and compute Cohen’s kappa (). The result yields , indicating substantial agreement. In addition, 289 out of 300 samples (96.33%) are jointly rated as pass. This high joint pass rate further corroborates that the Stage 1–refined benchmark meets our predefined quality standard. Finally, the full set of 3000 dialogues that complete the refine–verify pipeline constitute the final K-NameDiag benchmark. Its gold standard, which combines the Stage 2 objectives and the Stage 3 human annotation and verification, ensures textual quality, contextual appropriateness, and labeling completeness. Detailed statistics of the benchmark are provided in Appendix E and its organizational structure is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Organizational structure of the K-NameDiag benchmark. The “text” field contains an utterance meaning “P01: How was your weekend? Did you go anywhere?”. The “form” field represents the detected personal name in the sentence, which corresponds to the given name “Gahee”.

4. Experimental Setup

This section provides a detailed description of the experimental framework designed to evaluate the proposed method. We outline the benchmark and models used for evaluation, the comparative settings across different prompt configurations, the primary evaluation metrics, and the implementation details of the experiments.

All experiments are conducted on the targeted diagnostic benchmark K-NameDiag. To comprehensively assess the effectiveness and generalizability of our approach, we evaluate three state-of-the-art LLMs that represent the current technological frontier: OpenAI GPT-5, Google Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Anthropic Claude Sonnet 4.5.

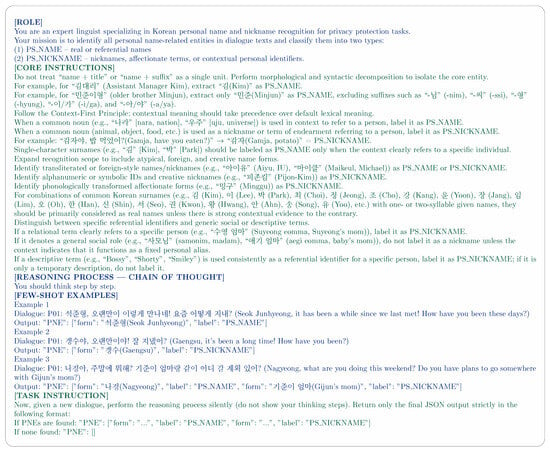

To clearly measure the contribution of each stage within our multi-layered prompt engineering framework, we design three progressively enhanced prompting configurations:

- BP (Baseline Prompt). The basic configuration that serves as the reference point for the models as shown in Appendix A.

- EDP (Error-Driven Prompt) The version that incorporates explicit linguistic and diagnostic knowledge, used to examine the effect of knowledge infusion.

- CEP (Combined Enhanced Prompt). The final configuration integrating structured reasoning instructions to evaluate the impact of general reasoning augmentation. The full prompt content of EDP and CEP is provided in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Comparison of the two enhanced prompting configurations. The green region corresponds to EDP (Error-Driven Prompt), while the green and blue regions together represent CEP (Combined Enhanced Prompt) with structured reasoning augmentation.

Figure 8. Comparison of the two enhanced prompting configurations. The green region corresponds to EDP (Error-Driven Prompt), while the green and blue regions together represent CEP (Combined Enhanced Prompt) with structured reasoning augmentation.

We compare the predicted entity text (form) and its corresponding label against the gold standard to evaluate model performance. Based on this comparison, we calculate Precision, Recall, and F1-Score to quantitatively measure overall effectiveness. The metrics are computed as follows:

where denotes the number of correctly predicted entities, represents the number of incorrectly predicted positive entities, and refers to the number of missed positive entities.

All model evaluations are conducted through their official APIs, using the latest available versions as of October 2025.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental results of the proposed framework and provides a detailed analysis of model performance under different prompting configurations. We first compare the performance between the BP and EDP to validate the effectiveness of the error-driven prompt design. We then introduce the CEP, which incorporates few-shot examples, CoT reasoning, and role-based contextualization to further examine the effect of reasoning enhancement. Finally, we conduct fine-grained analyses across error types and model dimensions to explore the reasoning differences among LLMs.

5.1. Overall Performance Comparison Across Prompt Configurations

Table 1 summarizes the performance of three models (Claude Sonnet 4.5, GPT-5, and Gemini 2.5 Pro) on the K-NameDiag benchmark under three prompting configurations: BP, EDP, and CEP.Under the BP setting, the three models achieved F1 scores ranging from 74.74% (Claude) to 78.92% (GPT-5), indicating that the K-NameDiag benchmark presented substantial challenges in name recognition. The baseline results further indicated reasoning biases across models. GPT-5 exhibited a conservative tendency with high precision and low recall (P = 82.12%, R = 75.96%), favoring fewer false positives at the cost of more false negatives. In contrast, Claude Sonnet 4.5 (P = 70.52%, R = 79.48%) and Gemini 2.5 Pro (P = 73.72%, R = 79.60%) displayed more aggressive behavior with higher recall but lower precision, suggesting a greater propensity to misidentify non-target entities as names. These findings highlighted inherent differences in decision thresholds and inference strategies across models when handling noisy contexts.

Table 1.

Overall performance (F1-Score, Precision, and Recall in %) on the K-NameDiag diagnostic benchmark across three prompt configurations. Arrows (↑ / ↓) indicate performance change from the previous prompt level (i.e., EDP vs. BP; CEP vs. EDP). For each model’s metric, the highest value is bolded and the lowest is underlined.

Transitioning from BP to EDP led to a substantial improvement across all models, demonstrating the effectiveness of error-driven prompt design in structured learning. All models showed a clear increase in F1, with Gemini 2.5 Pro achieving the largest gain (+8.94 points, 76.55% → 85.49%), followed by Claude (+6.88) and GPT-5 (+6.45). EDP improved overall performance while also mitigating baseline bias: GPT-5’s recall rose from 75.96% to 86.99%, while Claude (P: 70.52% → 78.28%) and Gemini (P: 73.72% → 84.43%) exhibited substantial precision improvements. These results indicated that targeted knowledge infusion and corrective heuristics were effective in reducing errors and enhancing model adaptability to domain-specific contexts.

Building on EDP, the introduction of CEP further increased the differences observed across models. The results showed clear differences when models processed more demanding reasoning instructions such as chain-of-thought and role-based prompting. GPT-5 exhibited steady gains across all metrics (F1 = 87.73%), indicating good adaptability in reasoning-oriented settings. In contrast, Gemini 2.5 Pro and Claude Sonnet 4.5 exhibited clear precision–recall trade-offs: Gemini attained even higher recall (88.20%) with a slight drop in precision (84.43% → 83.27%), while Claude showed the opposite pattern, improving precision to 84.68% with a marginal decline in recall (85.25% → 85.17%). These findings suggested that generic advanced prompts can accentuate each model’s inherent decision tendencies toward conservative or aggressive inference strategies.

Overall, the experimental results validated the effectiveness of the proposed multi-layer prompting framework, particularly highlighting the contribution of the error-driven prompt strategy. EDP functioned as a critical stage that advanced model performance from the baseline level to a higher tier by reducing errors and mitigating model bias, while CEP further refined reasoning stability and decision consistency. Although different models exhibited distinct tendencies when processing complex reasoning instructions, the overall trend indicated that the layered prompting structure provided clear performance gains, though advanced reasoning prompts may force models to navigate complex precision–recall trade-offs. Subsequent sections provide a fine-grained analysis of error types and semantic contexts to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying these performance enhancements.

5.2. Fine-Grained Diagnostic Analysis

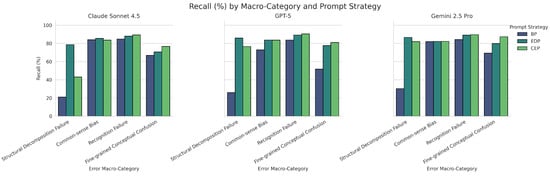

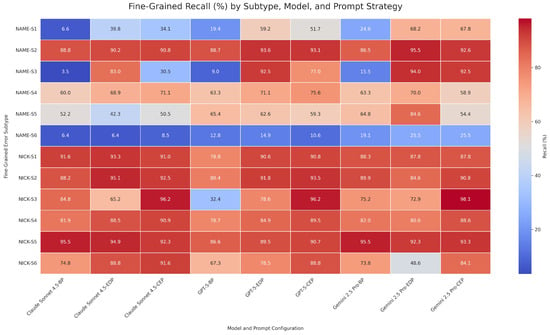

To conduct an in-depth analysis of model failure modes from the perspectives of privacy security and risk diagnosis, this section presents a detailed diagnostic analysis of model recall across four macro-categories and twelve fine-grained subtypes.

The results under BP showed that these evaluated models faced challenges when processing culture-specific phenomena. As shown in Figure 9, although all models exhibited relatively high recall in the categories of Recognition Failure and Common-sense Bias, this masked notable performance deficiencies in other critical categories. In particular, within the macro category of Structural Decomposition Failure, all models experienced a substantial drop in recall, maintaining only a range of 25 to 30 percent. The heatmap in Figure 10 further localized this issue to the fine-grained subtype NAME-S3, which refers to compound entities combining a personal name with a professional title. The recall rates for Claude, GPT-5, and Gemini 2.5 Pro on this subtype were 3.5%, 9.0%, and 15.5%, respectively. These results indicated that state-of-the-art models, when used out of the box, were almost entirely incapable of handling compound structures such as name-plus-title expressions in Korean. The models tended to treat such expressions as indivisible units, leading to failures in entity recognition. This finding shows why the diagnostic framework is necessary and makes clear the value of building fine-grained evaluation benchmarks for multilingual and culturally diverse contexts.

Figure 9.

Macro-level recall performance across four major categories.

Figure 10.

Micro-level recall heatmap across twelve fine-grained subtypes.

With the introduction of EDP, models showed consistent improvements in several major error categories, highlighting the framework’s combined effectiveness in both coverage and precision. In the category of structural decomposition failure, recall rates across all models increased from around 30% in the baseline stage to between 85% and 95% (see Figure 9). The heatmap in Figure 10 further showed that this overall improvement primarily stemmed from performance gains in the NAME-S3 subtype (compound entities). In this subtype, the structure-aware prompt substantially enhanced the models’ ability to recognize name + title combinations, raising the recall of Claude, GPT-5, and Gemini from 3.5%, 9.0%, and 15.5% to 83–94%, respectively. EDP also achieved consistent cross-model gains in the fine-grained conceptual confusion category. Taking NAME-S1 (standalone surnames) as an example—a subtype that heavily relies on contextual reasoning—all models showed extremely low recall under BP (only 6.6% for Claude, and less than 25% for GPT-5 and Gemini). With the referential judgment prompt, all models experienced substantial recall gains (e.g., Claude rose from 6.6% to 39.8%, and Gemini from 24.6% to 68.2%), demonstrating EDP’s practical utility in injecting culturally grounded pragmatic rules. In the recognition failure category, EDP exhibited complex, architecture-dependent effects. For the NAME-S5 subtype (foreign or atypical names), the recognition expansion prompt notably boosted Gemini’s recall (from 64.8% to 84.6%) and had a modest effect on GPT-5 (from 50.5% to 62.6%), but caused a clear performance drop for Claude (from 52.2% to 42.3%). In contrast, For the NICK-S6 subtype, EDP improved recall for Claude and GPT-5 but lowered Gemini’s recall (from 73.8% to 48.6%). These contrasting cross-model outcomes showed the intricate interactions between corrective prompts and each model’s inherent reasoning biases and knowledge structure. Collectively, these results indicated that As an error-driven prompting strategy, EDP can directly address structural weaknesses through clear rule injection, while also providing gains in semantically ambiguous and culturally sensitive contexts. However, the non-uniform effects across models suggested that prompt strategies should be tailored to account for differences in model reasoning mechanisms to enable more adaptive error correction interventions.

Although EDP showed good adaptability in addressing structural errors, its effectiveness was notably constrained in tasks that depend on more complex contextual reasoning. For example, the NICK-S3 subtype (relational referential nicknames), as shown in Figure 10, requires the model to determine whether a relational term functions as a specific referential identifier (for instance, whether “Suyeong’s mom” refers to a unique individual). Such cases involve cross-sentential coreference and role-based semantic inference, both of which extend beyond the operational scope of rule-based prompt injection. In this setting, EDP showed no performance gains and even led to a decrease in recall for Claude (from 84.8% to 65.2%). In contrast, the CEP strategy, which incorporates chain-of-thought reasoning, role simulation, and few-shot demonstrations, substantially improved models’ context understanding and inference capacity. As a result, recall exceeded 96% across all models for this subtype. These findings indicated that EDP was more suitable for addressing deficiencies in structural knowledge, whereas CEP proved more effective for tasks involving context-dependent referential reasoning. The two approaches therefore provided complementary benefits in the context of error correction.

Furthermore, the analysis showed structural limitations in the ability of prompting methods to mitigate deeply embedded common-sense biases. As shown in Figure 9, the macro-level recall for the “common-sense bias” category appeared relatively high under BP (exceeding 85%). However, further analysis indicated that this outcome was primarily driven by low-ambiguity cases within the NICK-S1 subtype, such as common noun nicknames like “Potato.” In contrast, NAME-S6 refers to noun-based person names that carry high semantic ambiguity, with examples such as “Uju” (meaning “universe”). For this subtype, all models performed poorly under all prompting configurations. Regardless of whether BP, EDP, or CEP is applied, recall consistently remained at or below 25.5%, and Claude achieved only 8.5% in the CEP condition. These findings show that the models keep interpreting words like “Uju” as common nouns, and this tendency still affects their behavior. This overrode the intended effects of both the context-first principle employed in EDP and the advanced reasoning mechanisms implemented in CEP. The continued presence of such patterns indicates a notable limitation in current in-context learning capabilities. Overcoming these entrenched inference failures may require strategies that move beyond prompting, such as enhanced representational learning or direct intervention in model-internal mechanisms.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed the issue where large language models fail to recognize culturally specific Korean name PII. To handle this problem, we proposed a Diagnose-and-Mitigate framework comprising a fine-grained error taxonomy, the K-NameDiag benchmark, and the Error-Driven Prompting (EDP) method.

The experimental results confirm two main findings. First, the proposed framework is effective for structural errors. By injecting explicit rules, we improved the ability of the models to recognize complex cases involving names combined with job titles. Second, we identified clear boundaries for prompt engineering. While effective for logic correction, prompting alone is not a complete solution for all error types, as it cannot fully override certain model behaviors.

In summary, this work provides a practical methodology for improving reliability in culturally specific domains. The findings show that securing PII requires a structured approach that involves diagnosing specific weaknesses first and then applying the corresponding solution. This framework serves as a necessary foundation for future research in multilingual privacy protection.

7. Limitations and Future Work

7.1. Limitations

While the proposed framework improved Korean name recognition, the current method has four main limitations. The first limitation involves the boundary of prompt engineering in correcting deep biases. Experimental results showed that for names identical to high-frequency common nouns, models frequently misclassified them as ordinary nouns even with complex reasoning prompts. This indicates that relying solely on context instructions during inference is difficult to fully override the statistical priors formed during pre-training. For such common-sense biases, the effect of prompt engineering is limited.

The second limitation lies in the reliance on expert experience. The current construction process requires linguistic experts to intervene in diagnosing error patterns and writing specific rules. While this approach ensures accuracy in specific contexts, it limits scalability. If the application expands to social media with frequent internet slang or requires handling large amounts of new data, this reliance on manual maintenance will face cost challenges.

The third limitation is the specificity of language and morphology. The heuristic rules summarized in this study are designed based on the characteristics of Korean as an agglutinative language. Although the methodology of diagnosis and mitigation is reusable, the specific prompt content cannot be directly transferred to languages with large morphological differences like English or Chinese. It requires redesigning the rule base for the target language.

The fourth limitation concerns the coverage of PII types. This study focused on recognizing names and nicknames, which are unstructured and have high difficulty. We did not include types such as ID numbers or phone numbers in the experiment. This is because such entities usually have rigid format features and can be solved by traditional regular expressions without using the pragmatic reasoning mechanism in this study. Therefore, the framework is more suitable for solving high-ambiguity privacy entity problems.

7.2. Future Work

Future research can address the limitations regarding scalability and the boundaries of prompting through three main directions. The first direction involves the development of a diagnostic meta-model to automate the diagnosis process. By training a lightweight classifier on error patterns, the system can identify error subtypes automatically and select prompt strategies. This mechanism helps replace the current workflow that depends on manual rules.

The second direction explores the application of supervised fine-tuning to address the limits of in-context learning. Instead of relying on inference instructions, the benchmark can be used to fine-tune model weights directly. This approach aims to realign the internal probability distribution regarding cultural entities.

The third direction involves the integration of retrieval-augmented generation to handle rare or foreign names. By accessing external cultural knowledge bases such as local name registries, the system can verify entities against ground truth data. This method helps reduce hallucination for entities not seen during pre-training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and H.K.; methodology, X.W.; software, X.W., G.C. and S.A.; validation, X.W., G.C., S.A., J.K., S.P. and H.C.; formal analysis, X.W., G.C., S.A., J.K., S.P., H.C. and J.L.; investigation, X.W., G.C. and S.A.; data curation, G.C., S.A., J.K., S.P., H.C. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and H.K.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Personal Information Protection Commission and the Korea Internet & Security Agency (KISA), Republic of Korea, under Project 2780000024; and in part by the Government of the Republic of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/wangxiaonan-git/K-NameDiag (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version 4o) for the purpose of language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Jongkyu Lee is employed by Tscientific Company Ltd. He declares that he has no known personal relationships or competing financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BP | Baseline Prompt |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CEP | Combined Enhanced Prompt |

| CoT | Chain-of-Thought |

| CRF | Conditional Random Field |

| EDP | Error-Driven Prompt |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| ICL | In-Context Learning |

| KDPII | Korean Dialogic PII Dataset |

| KISA | Korea Internet & Security Agency |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PHI | Protected Health Information |

| PII | Personally Identifiable Information |

| PLM | Pre-trained Language Model |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TP | True Positive |

Appendix A. Baseline Prompt Configuration

Table A1 presents the detailed configuration of the Baseline Prompt (BP), which is used for initial diagnostic probing (Section 3.1.1) and serves as the baseline for subsequent evaluation experiments (Section 4).

Table A1.

Configuration of the Baseline Prompt (BP). The output JSON key PNE stands for ‘Personal Name-related Entities’.

Table A1.

Configuration of the Baseline Prompt (BP). The output JSON key PNE stands for ‘Personal Name-related Entities’.

| Instruction | You are an information extraction model. Identify all spans in the given text that contain Korean personal names or nicknames. |

| Input | Dialogue sample from KDPII containing Korean personal names or nicknames. |

| Task | Extract all words or phrases in the text that represent a Korean personal name (PS_NAME) or nickname (PS_NICKNAME). If no entities are found, return an empty list as shown below. |

| Output Format | {“PNE”: [{“form”: “...”, “label”: “PS_NAME”}, {“form”: “...”, “label”: “PS_NICKNAME”}]} If no entities are found, return: {“PNE”: []} |

Appendix B. Organizational Structure of KDPII Dataset

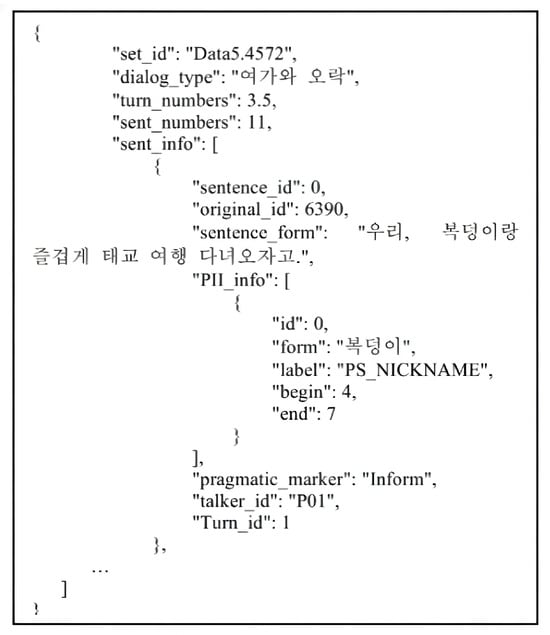

Figure A1 provides an overview of the internal organization of the KDPII dataset for reference.

Figure A1.

Organizational structure of the KDPII dataset, reproduced from [5] with permission. The “dialog_type” field corresponds to the category “Leisure and Entertainment”. The “sentence_form” field expresses the meaning “Let’s go on an enjoyable prenatal trip with Bukdeong-i.” The “form” field in the PII annotation represents a nickname referring to “Bukdeong-i”.

Appendix C. Adversarial Dialogue Generation Prompt

Table A2 provides the complete template used for generating adversarial dialogues in Stage 2. This template includes the role specification, task description, goal definition, adversarial entity set, constraints, and output format.

Table A2.

Prompt used for adversarial dialogue generation. The complete template includes role, task, goal, adversarial set, constraints, and output format.

Table A2.

Prompt used for adversarial dialogue generation. The complete template includes role, task, goal, adversarial set, constraints, and output format.

| Adversarial Dialogue Generation Prompt |

|---|

| # ROLE |

| You are an expert-level Korean scriptwriter and a linguist specializing in subtle linguistic nuances. |

| # TASK |

| Using the provided “Adversarial Name-Related Entity Set,” you must write a natural, multi-turn Korean dialogue of 8–12 turns that embeds these entities ambiguously. |

| # GOAL |

| This dialogue is used to test a language model’s ability to classify the precise label of the name-related entities. Therefore, the entities must be used naturally within the context while simultaneously containing traps or ambiguity that make their classification difficult. |

| # ADVERSARIAL NAME-RELATED ENTITY SET |

| {ADVERSARIAL_ENTITY_SET} |

| # CONSTRAINTS |

| 1. Entity Usage: Include all entities from the provided set in the dialogue. |

| 2. Dialogue Length: The dialogue must contain 8–12 turns and may involve two or three speakers (P01, P02, optionally P03). |

| 3. Naturalness: The dialogue must be realistic and coherent, as if spoken by native Koreans. |

| 4. Maintain Ambiguity (Critical): |

|

| # OUTPUT FORMAT |

| P01: [Dialogue content] |

| P02: [Dialogue content] |

| P03: [Dialogue content, if applicable] |

Appendix D. Dialogue Quality Assessment Rubric

Table A3.

Guideline used for dialogue quality evaluation in K-NameDiag. The rubric defines objectives, procedures, and criteria for four assessment dimensions.

Table A3.

Guideline used for dialogue quality evaluation in K-NameDiag. The rubric defines objectives, procedures, and criteria for four assessment dimensions.

| Dialogue Quality Assessment Rubric |

|---|

| Objective |

| This guideline assists researchers in evaluating the quality of candidate dialogues for K-NameDiag. The goal is to ensure linguistic naturalness, contextual appropriateness, and annotation feasibility of the final benchmark. |

| Evaluation Procedure |

| Each dialogue is evaluated along four core dimensions. For every dimension, the evaluator must assign one of two judgments: Acceptable (Pass) or Unacceptable (Fail). |

| Final Decision Rule |

| A dialogue is considered Pass (1) only if it is rated Acceptable on all four dimensions. If a dialogue is judged Unacceptable in even one dimension, it is rated Fail (0). |

| Dimension 1. Linguistic Naturalness and Coherence |

| Acceptable (Pass): |

|

| Unacceptable (Fail): |

|

| Dimension 2. Contextual Appropriateness of Target Entities |

| Acceptable (Pass): |

|

| Unacceptable (Fail): |

|

| Dimension 3. Verification of Target Entity Generation |

| Acceptable (Pass): |

|

| Unacceptable (Fail): |

|

| Dimension 4. Annotation Feasibility for Incidental PIIs |

| Acceptable (Pass): |

|

| Unacceptable (Fail): |

|

Appendix E. Statistics of the K-NameDiag Benchmark

Table A4 reports detailed statistics of the K-NameDiag benchmark.

Table A4.

Statistics of the K-NameDiag Benchmark.

Table A4.

Statistics of the K-NameDiag Benchmark.

| Category | Label | Value |

|---|---|---|

| A. Overall Scale | ||

| Total Dialogues | 3000 | |

| Total PII Instances | 6105 | |

| Total Dialogue Turns | 30,111 | |

| Total Tokens | 333,934 | |

| B. Label Distribution | ||

| PS_NAME | 3151 | |

| PS_NICKNAME | 2954 | |

| NAME-S1 | 211 | |

| NAME-S2 | 2421 | |

| NAME-S3 | 200 | |

| NAME-S4 | 90 | |

| NAME-S5 | 182 | |

| NAME-S6 | 47 | |

| NICK-S1 | 477 | |

| NICK-S2 | 306 | |

| NICK-S3 | 210 | |

| NICK-S4 | 1541 | |

| NICK-S5 | 313 | |

| NICK-S6 | 107 | |

| Unique PII Forms | 1375 | |

| C. Dialogue Characteristics | ||

| Average Turns per Dialogue | 10.04 | |

| Average PII Instances per Dialogue | 2.04 | |

References

- Li, Y.; Pei, Q.; Sun, M.; Lin, H.; Ming, C.; Gao, X.; Wu, J.; He, C.; Wu, L. CipherBank: Exploring the Boundary of LLM Reasoning Capabilities through Cryptography Challenge. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025; pp. 5929–5965. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhaei, M.S.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, B. An Empirical Study on the Effectiveness of Large Language Models for SATD Identification and Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.06806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deußer, T.; Sparrenberg, L.; Berger, A.; Hahnbück, M.; Bauckhage, C.; Sifa, R. A Survey on Current Trends and Recent Advances in Text Anonymization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.21587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, B.S.H.; Miao, X.; Wang, X. SecureSpeech: Prompt-based Speaker and Content Protection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07799. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, L.; Kang, Y.; Park, S.; Jang, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. KDPII: A new korean dialogic dataset for the deidentification of personally identifiable information. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 135626–135641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.; Kairouz, P.; Mireshghallah, N.; Bagdasarian, E.; Pham, C.M.; Houmansadr, A. Can Large Language Models Really Recognize Your Name? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.14549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, E.F.T.K.; De Meulder, F. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Natural Language Learning at HLT-NAACL 2003, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 31 May–1 June 2003; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chinchor, N.; Robinson, P. MUC-7 named entity task definition. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Message Understanding, Fairfax, VA, USA, 29 April –1 May 1998; Volume 29, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, A.; Uzuner, Ö. Annotating longitudinal clinical narratives for de-identification: The 2014 i2b2/UTHealth corpus. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 58, S20–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Narayanan, S. Unmasking the Reality of PII Masking Models: Performance Gaps and the Call for Accountability. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.12308. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Gu, Z.; Hong, H.; Han, W. PII-Bench: Evaluating Query-Aware Privacy Protection Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18545. [Google Scholar]