Featured Application

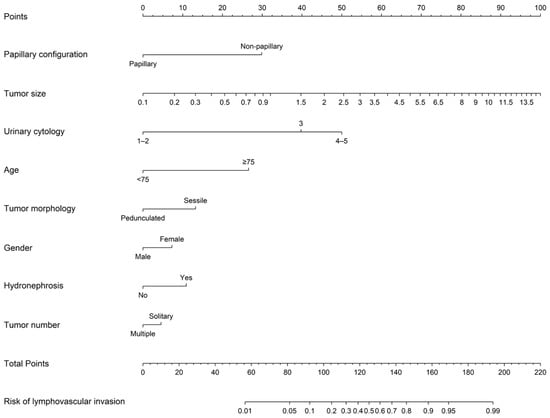

This nomogram demonstrates the possibility that there is lymphovascular invasion at initial transurethral resection of bladder tumors.

Abstract

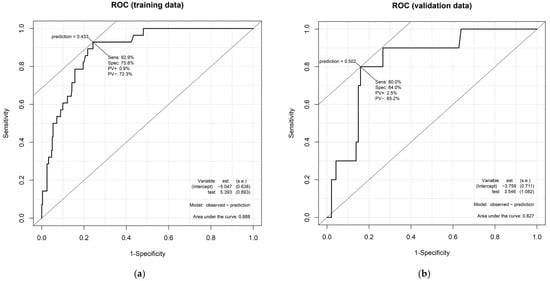

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is a potent yet underutilized prognostic marker in bladder cancer, particularly in non–muscle-invasive disease (NMIBC). We aimed to develop and internally validate a predictive nomogram to estimate the probability of LVI at initial transurethral resection of bladder tumors (TURBT), utilizing preoperative clinical parameters. In this retrospective cohort study, 413 patients with histologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma who underwent initial TURBT were included. LVI was identified histologically in 9.2% of cases. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression, in conjunction with the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator modeling, revealed eight significant predictors: papillary architecture, Box–Cox–transformed tumor size, urinary cytology classification, age ≥ 75 years, pedunculated morphology, gender, hydronephrosis, and tumor multiplicity. The resulting nomogram demonstrated excellent discriminative performance, with an AUC of 0.888 in the training cohort and 0.827 in the validation cohort, and exhibited good calibration based on weighted plots. This model facilitates individualized prediction of LVI using routinely available clinical data. Early detection of LVI may inform risk-adapted management strategies, including repeat resection, or intensified surveillance in patients with bladder cancer. The model complements existing predictive frameworks and can contribute to more personalized and effective bladder cancer care.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer is a common malignancy worldwide, with approximately 614,000 new cases reported in 2022 [1,2,3,4,5]. Its incidence is rising in Asian countries, reflecting aging populations and long-term exposure to smoking and industrial chemicals [1,2,3,4,5]. About 75% of patients present with non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [6,7]. The standard initial treatment for NMIBC is transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT), which is diagnostic and therapeutic [8,9].

Although NMIBC is considered an early-stage disease, it shows a high recurrence rate of 40–80% [10] and a 10–20% risk of progression to muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) [11,12,13,14,15], underscoring the need for early risk stratification to identify patients who may benefit from more aggressive therapy, such as early cystectomy, before progression occurs [16,17]. Predictive models such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and the Club Urológico Español de Tratamiento Oncológico (CUETO) scoring systems estimate recurrence and progression risk after TURBT, but their accuracy in routine practice is limited [17], prompting efforts to identify additional prognostic factors [18].

One such factor is lymphovascular invasion (LVI), defined as the presence of tumor cells within lymphatic or blood vessels [19,20]. In NMIBC, LVI in TURBT specimens is associated with increased risk of disease progression; a meta-analysis showed that LVI strongly predicts recurrence and progression and is linked to upstaging at definitive surgery [21], and high-grade T1 tumors with LVI are particularly prone to progression and metastasis [11,22]. In MIBC, LVI in cystectomy specimens is recognized as an independent predictor of recurrence and poor survival, even in patients with organ-confined, node-negative tumors [23]. Together, these findings indicate that LVI is a powerful marker across both NMIBC and MIBC.

Despite this, LVI is not widely incorporated into clinical decision-making or major risk models. Neither the EORTC nor CUETO models include LVI status, and the European Association of Urology guidelines do not recognize it as a formal risk factor for NMIBC [24], whereas the American Urological Association considers LVI a high-risk feature [25]. Routine use of LVI is further hampered by subjective assessment and interobserver variability among pathologists [20] and by limited concordance between LVI status in TURBT and cystectomy specimens, likely due to sampling error [23]. These issues have prevented the widespread integration of LVI into clinical prediction tools, despite its clear prognostic value [18].

To predict the pathological aggressiveness of bladder cancer before initial TURBT, we previously developed a model to identify high-grade papillary tumors using preoperative parameters such as age, sex, cytology, and tumor morphology [26], but no existing models have specifically targeted the prediction of LVI. As LVI may reflect the tumor immune microenvironment and be associated with responsiveness to immunotherapy [27], and because our recent investigations showed that preoperative features—including gross hematuria, positive cytology, larger tumor size, and sessile or non-papillary morphology—are significantly associated with LVI in TURBT specimens [28], its preoperative prediction could inform both surgical and systemic treatment strategies. These observations supported our development of a nomogram to estimate LVI status at the time of initial TURBT using readily available clinical data and to identify NMIBC patients harboring occult aggressive disease who may benefit from early and intensified therapeutic interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Toho University Sakura Medical Center, a high-volume tertiary referral institution with specialized expertise in the management of bladder cancer. A total of 413 consecutive patients diagnosed with bladder cancer who underwent initial TURBT for histologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma between January 2017 and December 2024 were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they had carcinoma in situ alone, tumors of non-urothelial histology, or incomplete clinical or pathological data. The primary endpoint was the presence of LVI, as determined by standard histopathological evaluation of TURBT specimens, as previously described [28].

2.2. Data Collection and Definitions

Demographic and clinical variables were retrospectively extracted from electronic medical records. Collected parameters included gender, age, presence of macrohematuria, tumor size (cm), tumor number (solitary vs. multiple), papillary configuration (papillary vs. non-papillary), tumor morphology (pedunculated vs. sessile), and the presence of hydronephrosis as identified on computed tomography or ultrasonographic imaging. Urinary cytology was classified according to the Papanicolaou system: Class 1–2 (negative), Class 3 (atypical), and Class 4–5 (suspicious or malignant).

LVI was defined as the unequivocal identification of tumor cells within endothelial-lined lymphatic or vascular channels, as visualized on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections [28]. All pathological evaluations were independently performed by board-certified genitourinary pathologists.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Initially, univariate analyses were conducted to evaluate associations between clinical variables and LVI status within the entire cohort. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Subsequently, variables demonstrating statistical significance in univariate analysis were included in multivariate logistic regression to identify significant predictors of LVI.

To construct the predictive nomogram, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression method was utilized. This technique effectively addresses multicollinearity among predictors and facilitates the selection of the most informative variables while preserving model simplicity and interpretability [29]. After using this model to select predictive variables meeting the criteria for minimal binomial deviance, the final nomogram incorporated the following variables: papillary architecture, Box–Cox–transformed tumor size, cytology classification, age ≥ 75 years, pedunculated morphology, gender, hydronephrosis, and tumor multiplicity. Each predictor was assigned a score within the nomogram, enabling individualized estimation of LVI probability at initial TURBT.

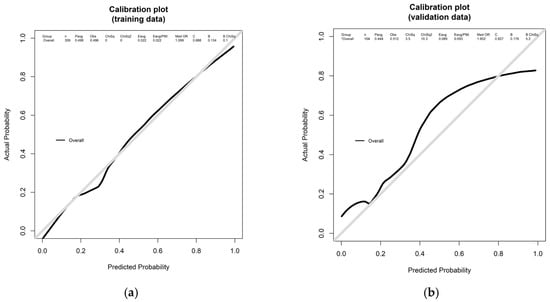

Model discrimination was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Calibration was assessed through a weighted calibration plot, comparing predicted and observed LVI probabilities across deciles of risk. Observed event rates were weighted by group size to provide a robust and interpretable evaluation of model calibration [30].

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.1 (http://www.r-project.org/, accessed on 25 July 2024), SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and EZR (https://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmedEN.html, accessed on 25 July 2024) [31]. A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (Approval No. T2025-037). Owing to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived. The study protocol was publicly disclosed on the institutional website to provide patients the opportunity to opt out. All procedures adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 413 enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. The cohort consisted of 317 males (76.8%) and 96 females (23.2%), with a median age of 75 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 11). Macrohematuria was documented in 273 patients (66.1%). The median tumor size was 1.8 cm (IQR: 1.7). Multiple tumors were observed in 194 patients (47.0%), while 51 patients (12.3%) exhibited non-papillary architecture and 140 (33.9%) demonstrated sessile morphology. Urinary cytology was distributed as follows: Class 1 in 59 patients (14.3%), Class 2 in 49 (11.9%), Class 3 in 163 (39.5%), Class 4 in 1 (0.2%), and Class 5 in 141 (34.1%). Hydronephrosis was identified in 39 patients (9.4%). LVI was histopathologically confirmed in 38 patients (9.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population.

3.2. Uni- and Multivariate Analyses

The results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 2. In univariate analysis, the presence of LVI was significantly associated with female (47.4% in LVI-positive vs. 21.6% in LVI-negative; p = 0.01), larger tumor size (median 2.7 cm vs. 1.7 cm; p < 0.01), non-papillary architecture (47.4% vs. 8.8%; p < 0.01), sessile morphology (63.2% vs. 30.9%; p < 0.01), high-grade cytology (Class 4–5: 57.9% vs. 32.0%; p < 0.01), and the presence of hydronephrosis (23.7% vs. 8.0%; p < 0.01). Age, tumor multiplicity, and macrohematuria did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Uni- and Multivariate Analyses of Clinical Predictors for Lymphovascular Invasion before Initial Transurethral resection of the Bladder Tumor.

In the multivariate analysis, three variables emerged as significant predictors of LVI: non-papillary tumor architecture (odds ratio [OR]: 7.97; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.73–17.00; p < 0.01), tumor size (OR per cm increase: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.08–1.57; p < 0.01), and cytology Class 4–5 (vs. Class 1–3; OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.29–5.62; p < 0.01). Although female, sessile morphology, and hydronephrosis were significant in univariate analysis, they did not retain significance in the multivariate model.

3.3. Model Construction and Validation

The study population was randomly divided into a training cohort (n = 309) and a validation cohort (n = 104), with comparable baseline characteristics. LASSO regression identified eight relevant predictors: papillary architecture, Box–Cox–transformed tumor size, categorized cytology grade (Class 1–2, 3, 4–5), age ≥ 75 years, pedunculated morphology, gender, hydronephrosis, and tumor multiplicity (Figure 1). These variables were incorporated into the final nomogram, providing a graphical tool for estimating the probability of LVI at initial TURBT.

Figure 1.

A Nomogram Predicting the Presence of Lymphovascular Invasion at Initial Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumors. Directions: A line was drawn upwards to the number of points in each category. The points were summed, and then a line of total points was drawn downwards to determine the probability on the bottom line.

The model demonstrated strong performance. The nomogram achieved an AUC of 0.888 in the training set and 0.827 in the validation set (Figure 2), indicating excellent discriminative ability. Weighted calibration plots utilizing locally weighted scatterplot smoothing showed close concordance between predicted and observed LVI probabilities across deciles of risk (Figure 3), indicating good calibration in both cohorts.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the nomogram for predicting the presence of lymphovascular invasion. The discriminative performance of the developed nomogram is illustrated by ROC curves in both (a) the training cohort (n = 309) and (b) validation cohort (n = 104). The area under the curve was 0.888 in the training set and 0.827 in the validation set, indicating strong predictive accuracy in both datasets.

Figure 3.

Calibration plots of the nomogram in the training and validation cohorts. Weighted calibration plots compare the predicted probability of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) with the observed incidence across risk deciles. The curves were smoothed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. Both (a) the training cohort (n = 309) and (b) validation cohort (n = 104) demonstrated good agreement between predicted and actual LVI probabilities, confirming the model’s calibration performance.

4. Discussion

Our study developed a novel nomogram to predict the presence of LVI in bladder tumors at initial TURBT, demonstrating robust discriminatory capacity and internal validity. This tool provides substantial clinical utility, as early identification of LVI can significantly influence therapeutic decision-making. There is also concern that less experienced urologists may encounter challenges in anticipating pathological features of bladder cancer, such as LVI, at the time of diagnosis. Clinical parameters may aid in predicting pathological outcomes prior to TURBT. Accordingly, the present study offers, to the best of our knowledge, valuable preoperative predictors of LVI at the time of initial TURBT. These insights may encourage urologists to perform deeper and more extensive resections.

LVI is a well-established adverse prognostic factor in bladder cancer [11,12], associated with advanced pathological stage, nodal involvement, and inferior oncologic outcomes, including recurrence, progression, and cancer-specific mortality [19,21]. In NMIBC, LVI in TURBT specimens is strongly associated with upstaging to muscle-invasive disease and subsequent progression; in a meta-analysis of approximately 4000 cases, LVI at initial TURBT tripled the risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease [11,13]. Among patients with high-grade T1 tumors, LVI further stratifies prognosis, with LVI-positive tumors showing markedly higher early progression rates (e.g., 66% vs. 10% at one year) and greater metastatic potential than LVI-negative tumors [22]. These data indicate that LVI is a surrogate for biologically aggressive disease with important clinical implications [28,32]. Our findings are concordant, as the predictors in our nomogram—larger, sessile, or multifocal tumors—are features commonly associated with invasive behavior and higher grade or stage. By integrating these variables, the nomogram offers a pragmatic tool to identify patients at risk for occult LVI preoperatively.

Early prediction of LVI status has clear relevance for both NMIBC and MIBC management strategies. In NMIBC, treatment selection is based on risk stratification to guide decisions between intravesical therapy and early radical intervention. Current risk models, such as those from EORTC, do not include LVI status explicitly [17]. However, the American Urological Association recognizes LVI as a high-risk feature [17,25], while the European guidelines have historically excluded it, despite acknowledging its negative prognostic impact when detected on TURBT [24]. Our findings support incorporating LVI risk into such frameworks. A patient predicted to have LVI at initial TURBT may be considered “very high risk,” prompting intensified management, such as early re-resection to confirm stage or even upfront radical cystectomy in selected cases. Several studies suggest that high-grade T1 tumors with LVI exhibit outcomes comparable to MIBC and may benefit from early cystectomy with curative intent [11,12,19,28,32]. One recent study identified LVI as the only independent predictor of progression at one year in T1 high-grade disease, supporting the use of upfront radical cystectomy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy in these patients [22,33]. Our nomogram may therefore facilitate risk-adapted pathways: patients with low predicted LVI risk may continue bladder-sparing strategies, whereas those with high risk can be counseled about definitive intervention, aiming to improve survival while reducing over- and undertreatment.

In patients diagnosed with MIBC at TURBT, LVI prediction remains highly relevant [32]. When LVI is present in specimens confirming ≥T2 disease, the risk of micrometastatic spread is significantly increased. Prior studies have shown that MIBC patients with LVI at TURBT or in cystectomy specimens have worse survival and may benefit more from systemic therapy [23]. In our cohort, clinical stage was among the strongest predictors of LVI: tumors classified as cT2 or greater on imaging were significantly more likely to harbor LVI on pathology [32]. Thus, our model can help identify MIBC patients at elevated risk who may require aggressive multimodal treatment. For example, patients with a high predicted probability of LVI could be prioritized for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and more extensive lymphadenectomy at cystectomy [32]. Although neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care for MIBC [14,17], preoperative knowledge of LVI risk may increase urgency for systemic treatment and surveillance. Notably, all predictors used in our nomogram are readily available in the preoperative setting—such as tumor morphology, imaging features, and cytology—making the model highly practical. Unlike molecular biomarkers, which require specialized assays, our model enables real-time risk estimation using standard clinical data [16].

This study builds upon prior efforts to anticipate adverse pathological features before surgery. Our earlier work showed that larger tumor size, non-papillary morphology, and positive cytology were associated with LVI at TURBT [28], and we incorporated similar predictors here; their concordance with the existing literature supports the model’s validity. The nomogram provides individualized risk probabilities rather than binary outputs, enabling more nuanced decisions. Nomogram-based tools have gained popularity in urologic oncology because they outperform single-variable predictors [29]. Although several nomograms predict recurrence or upstaging after cystectomy [13,29], our model is, to our knowledge, the first to specifically target LVI prediction at initial TURBT, complementing existing models such as those predicting upstaging from cT1 to ≥pT2 to provide a more comprehensive preoperative risk profile. Moreover, awareness of a high LVI probability may prompt pathologists to scrutinize specimens more carefully, particularly when LVI is subtle or under-recognized on standard H&E staining [23].

Beyond our single-center experience, recent work illustrates how contemporary prediction and decision-support tools are reshaping urothelial cancer care across the disease continuum. The IDENTIFY risk calculator for patients with haematuria uses machine learning and external validation in a large, multinational cohort to provide individualized probabilities of urinary tract cancer and to define clinically meaningful risk strata that guide the intensity of diagnostic work-up, exemplifying how quantitative risk estimates can structure referral and investigation pathways in everyday practice [34]. Similarly, a recent multicenter analysis of patients undergoing radical cystectomy showed that even simple preoperative markers such as anaemia are highly prevalent and independently associated with adverse perioperative and oncological outcomes, underscoring the prognostic value of routinely collected baseline clinical variables and the opportunity for risk-directed optimization before definitive treatment [35]. At the same time, studies in digital pathology have highlighted that real-world artefacts, including tissue contamination, can substantially compromise the performance and credibility of machine-learning models when deployed outside tightly controlled laboratory settings, emphasizing the need for rigorous validation, quality assurance, and awareness of local workflow when implementing predictive tools in practice [36]. In the surgical domain, ex vivo optical imaging of urethral and ureteral margins during radical cystectomy has been proposed as a real-time intraoperative decision-support technique, enabling more precise assessment of fresh, unfixed surgical margins and potentially refining oncological control at the time of surgery [37]. Taken together, these developments frame our LVI-focused nomogram as a complementary, low-cost clinicopathological tool that fits within a broader trajectory of guideline-informed, risk-adapted management in both NMIBC and MIBC—bridging pre-TURBT risk stratification with perioperative and intraoperative strategies aimed at improving oncological outcomes.

A critical methodological consideration pertains to the categorization of urine cytology. In our nomogram, cytological results were classified according to the traditional Papanicolaou system—Class I–II (negative), Class III (atypical), and Class IV–V (suspicious or malignant). Although this classification remains widely utilized across many institutions, it does not directly align with the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology (TPS), which is increasingly adopted on an international scale [38,39]. TPS categorizes specimens as “Negative for High-Grade Urothelial Carcinoma (NHGUC),” “Atypical Urothelial Cells (AtUC),” “Suspicious for High-Grade Urothelial Carcinoma (SHGUC),” and “High-Grade Urothelial Carcinoma (HGUC),” with a conceptual emphasis on identifying high-grade lesions. As such, there is no exact one-to-one correspondence between the cytological categories used in our model and those of the Paris System. Nonetheless, practical concordance exists: Class I–II generally aligns with NHGUC, Class III broadly corresponds to AtUC, and Class IV–V approximates SHGUC and HGUC [38,39,40]. Recent studies have demonstrated reasonable concordance between Papanicolaou-based categorization and Paris-based risk stratification in bladder cancer cytology [38,39,40]. Thus, although our model is not explicitly Paris-based, its cytology inputs remain clinically meaningful and readily interpretable within both classification systems. The model may be adapted for use in TPS-aligned settings by appropriately mapping cytological categories, thereby preserving its clinical applicability in modern diagnostic practice.

From a clinical perspective, the predicted probability of LVI may help urologists refine decision-making beyond conventional risk groups. For patients with a high predicted LVI probability (e.g., ≥20–30%), our nomogram may support a more aggressive strategy, such as early re-TURBT, early radical cystectomy in selected high-risk NMIBC, or intensified intravesical therapy and surveillance. In contrast, patients with a low predicted probability (e.g., <10%) might be managed with standard intravesical therapy and routine surveillance. These numeric thresholds are exploratory rather than prescriptive; they illustrate how the model could stratify risk within existing European Association of Urology (EAU)/American Urological Association (AUA) risk categories [6,17,24]. Importantly, the nomogram is not intended to replace EAU/AUA risk groups but to complement them by identifying a very-high-risk subset within the high-risk NMIBC population who may harbor occult LVI and benefit from more intensive management. Prospective studies are needed to define optimal decision thresholds and to evaluate whether model-guided management improves oncological outcomes.

This study has several strengths. It was conducted using a contemporary clinical cohort, and the nomogram demonstrated good calibration and internal discrimination. Because it relies solely on objective and routinely available clinical parameters, the model is applicable in daily practice. If decision-curve analysis was performed, it would likely confirm a net clinical benefit across relevant thresholds, demonstrating added value compared to treating all or no patients. By focusing on LVI—a frequently underappreciated but powerful prognostic marker—our nomogram addresses a key gap in preoperative risk assessment, enabling more personalized and informed patient counseling. Nonetheless, several limitations warrant consideration. First, this retrospective, single-center design may limit generalizability due to institutional variation in TURBT technique and pathological evaluation. Second, although the overall sample size was adequate, the proportion of LVI-positive cases was modest (~9.2%), which may restrict the ability to detect weaker predictors. Third, LVI assessment was based on standard H&E pathology without centralized review or routine immunohistochemistry, introducing potential misclassification. Fourth, the model underwent only internal validation; because preoperative LVI prediction is strongly influenced by local practice patterns—including pathology workflow, completeness of TURBT, and imaging protocols—its performance at other institutions remains uncertain, and external validation in multi-institutional cohorts is essential before routine implementation. Finally, we did not incorporate radiographic information, including CT or MRI-derived features, because imaging data were not collected in a standardized format. Given growing interest in preoperative MRI and radiomics-based markers, future studies integrating clinicopathological variables with quantitative imaging features may yield more accurate and generalizable prediction models.

5. Conclusions

We developed and internally validated a novel nomogram to predict the presence of LVI at the time of initial TURBT. This tool enables preoperative estimation of LVI—a key yet underutilized prognostic factor—using routinely available clinical and pathological parameters. It offers a practical means to support individualized and risk-adapted treatment decisions in both NMIBC and MIBC.

By identifying patients at high risk of LVI before definitive treatment, the model may help guide early re-resection, more intensive surveillance, or decision curve analysis. It complements existing predictive frameworks without added cost or the need for specialized testing. Future studies should focus on external validation and prospective evaluation to confirm its utility and potential to improve treatment strategies and outcomes in bladder cancer care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S. and T.U.; methodology, T.U.; software, T.S.; validation, T.N., T.S. and R.O.; formal analysis, T.S. and T.U.; investigation, Y.S. (Yuta Suzuki) and T.E.; resources, N.I., Y.S. (Yuka Sugizaki) and S.I.; data curation, R.I., Y.S. (Yuta Suzuki), N.I., Y.S. (Yuka Sugizaki), S.I. and T.E.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.U.; visualization, T.U.; supervision, N.K., N.H. and H.S.; project administration, N.K., N.H. and H.S.; funding acquisition, T.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (Grant Number JP24K12519).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Toho University (Approval No. T2025-037).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study was disclosed on the institutional website, allowing potential participants to opt out.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Hiroyoshi Suzuki reports research funding from Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Nihon Kayaku, and Sanofi; advisory fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Chugai-Roche, Eli Lilly, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and lecture fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AtUC | atypical urothelial cells |

| AUA | American Urological Association |

| AUC | area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CUETO | Club Urológico Español de Tratamiento Oncológico |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| HGUC | high-grade urothelial carcinoma |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| LASSO | least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| LVI | lymphovascular invasion |

| MIBC | muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| NHGUC | negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma |

| NMIBC | non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SHGUC | Suspicious for high-grade urothelial carcinoma |

| TURBT | transurethral resection of the bladder tumor |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seisen, T.; Labban, M.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Preston, M.A.; Mossanen, M.; Bellmunt, J.; Rouprêt, M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Kibel, A.S.; Sun, M.; et al. Assessment of the ecological association between tobacco smoking exposure and bladder cancer incidence over the past half-century in the United States. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1986–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washio, M.; Mori, M.; Tamakoshi, A. Lifestyle factors and the risk of kidney and bladder cancer in the Japanese population: A mini-review. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.-S.; Luan, H.-H.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, J.-F.; Zeng, X.-T.; Huang, J.; Jin, Y.-H. The disease burden of bladder cancer and its attributable risk factors in five eastern asian countries, 1990-2019: A population-based comparative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; Cohen, D.; Compérat, E.M.; Escrig, J.L.D.; Gontero, P.; Liedberg, F.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Mostafid, A.H.; et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (ta, T1, and carcinoma in situ). Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Caamaño, A.; García Vicente, A.M.; Maroto, P.; Rodríguez Antolín, A.; Sanz, J.; Vera González, M.A.; Climent, M.Á. Spanish Oncology Genitourinary (SOGUG). Multisiciplinary Working Group Multisiciplinary Working Group Management of localized muscle-invasive bladder cancer from a multidisciplinary perspective: Current position of the spanish oncology genitourinary (SOGUG) working group. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5084–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, R.J.; van der Meijden, A.P.M.; Oosterlinck, W.; Witjes, J.A.; Bouffioux, C.; Denis, L.; Newling, D.W.; Kurth, K. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: A combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur. Urol. 2006, 49, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, Q.; Li, Y. Precise diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer—A clinical perspective. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1042552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrao, D.; Lizana, N.; Saavedra, C.; Larrañaga, M.; Lindsay, C.B.; Francisco, I.F.S.; Bravo, J.C. Active surveillance in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, the potential role of biomarkers: A systematic review. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2201–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Kimura, S.; Foerster, B.; Abufaraj, M.; D’ANdrea, D.; Hassler, M.; Minervini, A.; Rouprêt, M.; Babjuk, M.; Shariat, S.F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of lymphovascular invasion in bladder cancer transurethral resection specimens. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.S.; Seo, H.K.; Joung, J.Y.; Park, W.S.; Ro, J.Y.; Han, K.S.; Chung, J.; Lee, K.H. Lymphovascular invasion in transurethral resection specimens as predictor of progression and metastasis in patients with newly diagnosed T1 bladder urothelial cancer. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 2625–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.P.; Skinner, E.C.; Miranda, G.; Daneshmand, S. A precystectomy decision model to predict pathological upstaging and oncological outcomes in clinical stage T2 bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witjes, J.A.; Bruins, H.M.; Carrión, A.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Fietkau, R.; Gakis, G.; Lorch, A.; Martini, A.; et al. European association of urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2024, 85, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Campi, R.; Tellini, R.; Gandaglia, G.; Albisinni, S.; Abufaraj, M.; Hatzichristodoulou, G.; Montorsi, F.; van Velthoven, R.; Carini, M.; et al. Patterns and predictors of recurrence after open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: A comprehensive review of the literature. World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prijovic, N.; Acimovic, M.; Santric, V.; Stankovic, B.; Nikic, P.; Vukovic, I.; Radovanovic, M.; Kovacevic, L.; Nale, P.; Babic, U. The impact of variant histology in patients with urothelial carcinoma treated with radical cystectomy: Can we predict the presence of variant histology? Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8841–8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.S.; Boorjian, S.A.; Chou, R.; Clark, P.E.; Daneshmand, S.; Konety, B.R.; Pruthi, R.; Quale, D.Z.; Ritch, C.R.; Seigne, J.D.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xylinas, E.; Rink, M.; Robinson, B.D.; Lotan, Y.; Babjuk, M.; Brisuda, A.; Green, D.A.; Kluth, L.A.; Pycha, A.; Fradet, Y.; et al. Impact of histological variants on oncological outcomes of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder treated with radical cystectomy. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, R.; Lucca, I.; Rouprêt, M.; Briganti, A.; Shariat, S.F. The prognostic role of lymphovascular invasion in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2016, 13, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-F.; Zhou, H.; Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Xia, D.; Xiao, H.-B.; Liu, J.-H.; Ye, Z.-Q.; Xu, H.; et al. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in bladder cancer after surgical resection: A meta-analysis. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2015, 35, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, M.; Jeong, C.W.; Kwak, C.; Kim, H.H.; Ku, J.H. Presence of lymphovascular invasion in urothelial bladder cancer specimens after transurethral resections correlates with risk of upstaging and survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gercek, O.; Senkol, M.; Yazar, V.M.; Topal, K. The effect of lymphovascular invasion on short-term tumor recurrence and progression in stage T1 bladder cancer. Cureus 2024, 16, e54844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.J.; Bergey, M.; Magerfleisch, L.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Guzzo, T.J. Longitudinal evaluation of the concordance and prognostic value of lymphovascular invasion in transurethral resection and radical cystectomy specimens. BJU Int. 2011, 107, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gontero, P.; Birtle, A.; Capoun, O.; Compérat, E.; Dominguez-Escrig, J.L.; Liedberg, F.; Mariappan, P.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Mostafid, H.A.; Pradere, B.; et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in situ)-A summary of the 2024 guidelines update. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldu, S.L.; Bagrodia, A.; Lotan, Y. Guideline of guidelines: Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2017, 119, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, K.; Utsumi, T.; Yoneda, K.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Yano, M.; Fujimura, M.; Kamiya, N.; Sekita, N.; Mikami, K.; et al. Development and external validation of a nomogram to predict high-grade papillary bladder cancer before first-time transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 23, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owyong, M.; Lotan, Y.; Kapur, P.; Panwar, V.; McKenzie, T.; Lee, T.K.; Zi, X.; Martin, J.W.; Mosbah, A.; Abol-Enein, H.; et al. Expression and prognostic utility of PD-L1 in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urol. Oncol. 2019, 37, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, K.; Utsumi, T.; Wakai, K.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Yano, M.; Kamiya, N.; Hiruta, N.; Suzuki, H. Preoperative clinical predictors of lymphovascular invasion of bladder tumors at transurethral resection pathology. Curr. Urol. 2020, 14, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, T.; Ishitsuka, N.; Noro, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Iijima, S.; Sugizaki, Y.; Somoto, T.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Kamiya, N.; et al. Development, validation, and clinical utility of a nomogram for urological tumors: How to build the best predictive model. Int. J. Urol. 2025, 32, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; McLernon, D.J.; van Smeden, M.; Wynants, L.; Steyerberg, E.W. Topic Group ‘Evaluating Diagnostic Tests and Prediction Models’ of the STRATOS Initiative. Calibration: The achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, K.; Kamiya, N.; Utsumi, T.; Wakai, K.; Oka, R.; Endo, T.; Yano, M.; Hiruta, N.; Ichikawa, T.; Suzuki, H. Impact of lymphovascular invasion on prognosis in the patients with bladder cancer-comparison of transurethral resection and radical cystectomy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, G.E.; Chang, S.S. Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: Identifying patients to consider timely, initial cystectomy. Bull. Urooncol. 2020, 19, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadhouri, S.; Hramyka, A.; Gallagher, K.; Light, A.; Ippoliti, S.; Edison, M.; Alexander, C.; Kulkarni, M.; Zimmermann, E.; Nathan, A.; et al. Machine Learning and External Validation of the IDENTIFY Risk Calculator for Patients with Haematuria Referred to Secondary Care for Suspected Urinary Tract Cancer. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irmakci, I.; Nateghi, R.; Zhou, R.; Vescovo, M.; Saft, M.; Ross, A.E.; Yang, X.J.; Cooper, L.A.; Goldstein, J.A. Tissue Contamination Challenges the Credibility of Machine Learning Models in Real World Digital Pathology. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 37, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, E.; Antonelli, L.; Afferi, L.; Asero, V.; Prata, F.; Rebuffo, S.; Veccia, A.; Culpan, M.; Tully, K.; Ribeiro, L.; et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Anemia in Radical Cystectomy Patients: A Multicenter Retrospective Observational Study. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 77, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, F.; Anceschi, U.; Taffon, C.; Rossi, S.M.; Verri, M.; Iannuzzi, A.; Ragusa, A.; Esperto, F.; Prata, S.M.; Crescenzi, A.; et al. Real-Time Urethral and Ureteral Assessment during Radical Cystectomy Using Ex-Vivo Optical Imaging: A Novel Technique for the Evaluation of Fresh Unfixed Surgical Margins. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3421–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.A.; Ozretić, L.; El Sheikh, S. The diagnostic accuracy of the paris system for reporting upper urinary tract cytology: The atypical urothelial cell conundrum. Cancers 2025, 17, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikas, I.P.; Seide, S.; Proctor, T.; Kleinaki, Z.; Kleinaki, M.; Reynolds, J.P. The paris system for reporting urinary cytology: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Miki, Y.; Hang, J.; Vohra, M.; Peyton, S.; McIntire, P.J.; VandenBussche, C.J.; Vohra, P. A review of upper urinary tract cytology performance before and after the implementation of the paris system. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020, 129, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).