Abstract

Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) has become a promising strategy for accelerating process development in Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Metals (PBF-LB/M), where experimental evaluations are costly, and design spaces are high-dimensional. This study investigates how different initialization strategies affect MOBO performance in a discrete, machine-limited parameter space during the fabrication of AZ31 magnesium alloy. Three approaches to constructing the initial experimental dataset—Latin Hypercube Sampling (V1), balanced-marginal selection (V2), and prior fractional-factorial sampling (V3)—were compared using two state-of-the-art MOBO algorithms, DGEMO and TSEMO, implemented within the AutoOED platform. A total of 180 samples were produced and evaluated with respect to two conflicting objectives: maximizing relative density and build rate. The evolution of the Pareto front and hypervolume metrics shows that the structure of the initial dataset strongly governs subsequent optimization efficiency. Variant V3 yielded the highest hypervolumes for both algorithms, whereas Variant V2 produced the most uniform Pareto approximation, highlighting a trade-off between global coverage and structural distribution. TSEMO demonstrated faster early convergence, whereas DGEMO maintained broader exploration of the design space. Analysis of duplicate experimental points revealed that discretization and batch selection can considerably limit the effective search diversity, contributing to an early saturation of hypervolume gains. The results indicate that, in constrained PBF-LB/M design spaces, MOBO primarily serves to validate and refine a well-designed initial dataset rather than to discover dramatically new optima. The presented workflow highlights how initialization, parameter discretization, and sampling diversity shape the practical efficiency of MOBO for additive manufacturing process optimization.

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) encompasses a family of technologies that fabricate three-dimensional components by adding material layer by layer according to digital models. Among the techniques standardized in ASTM/ISO 52900 [1], Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Metals (PBF-LB/M) has become one of the most advanced and versatile [2]. In this process, a focused laser beam selectively melts regions of a thin powder layer, producing dense, near-net-shape metallic parts with excellent dimensional accuracy and mechanical performance. However, the process involves highly nonlinear thermal phenomena, including rapid melting and solidification, recoil pressure, and vaporization, which make the development of stable processing windows for new alloys both time-consuming and costly.

The PBF-LB/M process depends on a large number of interacting variables—more than fifty according to Spears & Gold [3]—such as laser power, scan speed, point distance, hatch spacing, and layer thickness, which are recognized as the most important ones, affecting the process variability the most. These parameters jointly determine the resulting porosity, microstructure, and build rate [4,5]. Conventional optimization relies on empirical tuning or stepwise adjustment [6,7], where early parameter choices are fixed and later iterations neglect their interactions. Consequently, discovering optimal combinations through direct experimentation becomes prohibitively expensive, especially when each trial requires powder preparation, part fabrication, post-processing, and microscopy or mechanical testing.

1.1. Why Direct Optimization Is Infeasible

Even a coarse parametric grid grows explosively as additional factors are introduced. For example, exploring a space defined by laser power (P), point distance (p), and hatch spacing (h) at only ten levels each already implies 103 = 1000 combinations. Starting from the optimal set retrieved from the previous literature studies for alloys similar by its composition or melting temperature, it is not justified that the published data only considers optimal sets, as opposed to arbitrary ones. Including additional parameters such as laser spot size, focal depth, or layer thickness easily expands this to several thousand possible settings. In more complex systems—e.g., multicomponent alloys or heat-treatment studies—the design space can reach tens of thousands of experiments. Each evaluation in PBF-LB/M involves printing, post-processing, and material characterization, with typical campaigns probing 10–20 parameter sets merely to identify a viable process window before mechanical validation. This combinatorial explosion renders brute-force or exhaustive optimization approaches entirely impractical, motivating the search for data-efficient algorithms that minimize the number of required experiments while maintaining reliable predictive power.

1.2. From Classical to Probabilistic Process Optimization

Traditional Design of Experiments (DoE) frameworks were designed to identify key process variables efficiently [8]. Fractional factorial and response surface designs can reduce the number of tests but remain limited to problems with few variables and a single objective. However, modern manufacturing processes are inherently multi-objective—optimizing density, productivity, and surface quality simultaneously—where objectives often conflict. Multi-objective optimization (MO) methods [9,10], therefore, aim to approximate the Pareto front—the set of trade-off solutions for which no objective can be improved without deteriorating another [11].

Evolutionary algorithms [12] have been widely used for this purpose, but their reliance on stochastic sampling and large iteration counts makes them unsuitable for physical experiments. Furthermore, experimental data in AM are inherently noisy—powder variability, scanning stability, and environmental fluctuations introduce uncertainty even for identical parameter sets. To manage such uncertainty while learning from limited data, Bayesian Optimization (BO) offers a statistically grounded framework [13,14]. BO constructs a probabilistic surrogate model, most commonly a Gaussian Process (GP), that predicts objective values and associated uncertainty across the parameter space. New experimental points are proposed by optimizing an acquisition function that balances exploration and exploitation—seeking regions with both high predicted performance and high uncertainty.

1.3. Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization and Algorithmic Strategies

Extending BO to multiple objective problems leads to Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO), which can approximate Pareto fronts efficiently through iterative experimentation. The algorithms used in Bayesian optimization differ in how they explore the design space [15,16,17,18], define utility functions [19,20,21], and represent objective functions [22,23]. Algorithm selection should depend on the problem’s specific characteristics—such as the number of objectives, noise level, or constraints.

Among the available MOBO algorithms, Diversity-Guided Efficient Multi-objective Optimization (DGEMO) and Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-objective Optimization (TSEMO) have been demonstrated to perform well in “black-box” experimental scenarios where batch selection is required [24,25]. Both algorithms can propose new experiments in batches, rather than sequentially, which is particularly valuable when manufacturing multiple samples in a single build. DGEMO emphasizes maintaining diversity across the parameter space and the Pareto front, reducing the risk of converging prematurely to local optima. In contrast, TSEMO uses probabilistic Thompson sampling to select candidate points that simultaneously reduce model uncertainty and expand the Pareto front. These strategies make MOBO especially well-suited to additive manufacturing, where the cost of each experimental evaluation is high and process–property relationships are complex and partially unknown.

Recent research shows the increasing integration of machine learning (ML) with Bayesian methods in AM [26]. Hybrid models combining BO with neural networks can predict feasible regions and refine acquisition functions [27,28]. Machine learning is also used for in situ monitoring and defect prediction [29,30], and similar optimization frameworks are being extended to other techniques such as Directed Energy Deposition (DED) [31]. The development of open and reproducible optimization platforms is now seen as essential for accelerating process development and knowledge transfer [32].

1.4. Objectives and Scope of the Present Study

The present research aims to evaluate how efficiently Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization can guide process development in PBF-LB/M compared to traditional optimization approaches. Specifically, it analyses how different initial experimental datasets affect convergence, considering both cases where no prior data exist and where results from previous experiments are available as initial input.

To this end, an open and automated optimization framework based on the AutoOED platform is employed. Two MOBO algorithms, DGEMO and TSEMO, are implemented to optimize the process of AZ31 magnesium alloy fabrication. This material serves as a technically demanding case study for verifying the optimization framework due to its high chemical reactivity, narrow processability window, and industrial relevance for lightweight structural and biomedical applications [33,34].

The optimization is formulated as a bi-objective maximization problem targeting (1) the relative density of the fabricated material and (2) the process build rate. The framework iteratively updates Gaussian-process surrogate models and acquisition functions to suggest new experimental batches. Optimization performance is evaluated through the evolution of the Pareto front and hypervolume improvement metrics.

In summary, this work does not seek merely to improve a specific alloy but to demonstrate a generalizable and data-efficient methodology for the optimization of complex additive manufacturing processes. The following section details the experimental and computational methodology, the Results and Discussion section presents and compares the results for DGEMO and TSEMO, and finally, the paper concludes with perspectives on extending this workflow to other materials and process classes.

The novelty of this work lies in three aspects that, to the best of our knowledge, have not been jointly addressed in the context of PBF-LB/M process optimization: (1) systematically compare three fundamentally different initialization strategies (LHS, balanced-marginal, and fractional-factorial-derived sampling) in a discrete, machine-limited design space, which is typical for industrial PBF-LB/M systems but rarely analyzed in MOBO studies; (2) evaluate the performance of two state-of-the-art MOBO algorithms (DGEMO and TSEMO) under identical experimental conditions and identical data budgets, allowing for a fair comparison of exploration–exploitation behaviour in physical experiments rather than simulations; and (3) diagnose the impact of design-space discretization and batch-induced duplication on optimization saturation—an effect acknowledged in theory but not quantitatively demonstrated in real PBF-LB/M experiments.

Taken together, this study provides the first experimental evidence of how initialization strategy and parameter discretization jointly determine the practical efficiency of MOBO in metal AM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Manufacturing

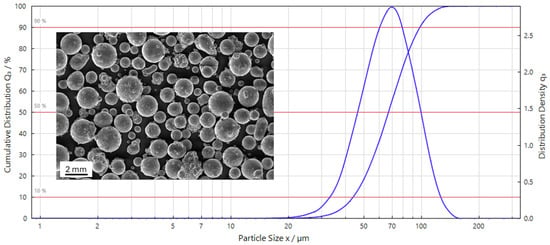

In this study a AZ31 magnesium alloy powder was used with a particle size ranging 45–100 µm (TLS Technik & Spezialpulver GmbH, Bitterfeld, Germany).

The supplier declared particle size distribution was verified using HELOS H3776, RODOS/T4/R4 laser diffraction and VIBRI dispersion unit (Sympatec GmbH, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany)—Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution for AZ31 powder used in the study, and particle morphology–SEM image.

All samples were manufactured with a SLM ReaLizer 50 PBF-LB/M device (ReaLizer GmbH, Borchen, Germany) equipped with an IPG (IPG Laser GmbH, Burbach, Germany) fibre laser of 100 W maximum power and with a fixed layer thickness of 50 µm. During the samples manufacturing process, repeatable conditions were provided, including argon protective atmosphere, no build platform preheating, and scanning the samples cross-sections by vectors, that their orientations alternately switches by 90 degrees every layer.

2.2. Optimization Criteria

In this work, two conflicting objectives for PBF-LB/M process optimization were evaluated at the same time: relative density maximization and an increase in the build rate. In general, we consider the problem as a bi-objective maximization:

where is the sample relative density, is the process build rate.

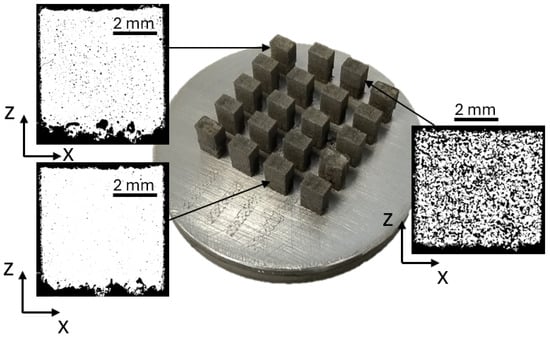

The relative density of the processed material was evaluated using microscopic cross-section analysis. The sample images of ground and polished samples were captured with ×5 magnification, following the standard [35] using an Olympus LEXT OLS 4000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The images covered the entire area of a 5 × 5 mm sample cross-section in the xz plane, by stitching 9 images together into a single picture in a matrix of 3 × 3. The obtained metallographic images were binarized and the ROIs (regions of interest) were evaluated as the number of pixels for the pores compared to the total area of pixels to calculate the relative density of the sample material (Reldens),

The image analysis was performed using ImageJ 1.52a open-source software (LOCI, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA). Figure 2 presents an exemplary build plate with manufactured samples, as well as cross-sections of selected samples.

Figure 2.

An example image of one of the build plates with selected sample cross-sections obtained using a confocal laser microscope.

The build rate (Brt) is a metric, calculated as:

where hd is a hatch distance [mm], and t is a fixed layer thickness [mm] t = 0.05.

The machine used in this study operates in a point-exposure mode, and then an optional kinematic relation may define the scanning velocity:

Otherwise, V can be directly controlled/derived from native machine parameters, when using other PBF-LB/M equipment.

2.3. Design Space

Four different processing parameters were considered as the design space for the experiment: laser power—P [W], point distance—pdist [µm], laser exposure time—texpo [µs], and hatch distance—hd [µm]. For this research, the possible values that each of the above-mentioned parameters (x) could take were restricted, and they belong to a discrete subset (X) of the design space resulting from the technology limitations:

The maximum distance between consecutive scanning points, as well as the hatch distance, was set to be limited to 100 µm. This is justified by the optical system, and the laser beam spot size is 100 µm because of the f-theta lens installed in the PBF-LB/M used. That is why higher values than 100 µm between neighbouring scan tracks would not lead to an overlapping section that ensures the connectivity of the melted material. The laser power was limited to the upper half of the possible range (50–100 W), based on previous research reported on this material [5]. Then the last variable was limited to a very low range of possible values, ranging from 20 to 100 µs, just to evaluate only the maximum possible processing scanning speed. In addition, for each variable, a step size was set in the selected range to limit the possible number of combination variables. Complete information on the possible parameter values for each experiment variable is presented in Table 1. This study introduces limitations by using a reduced range of possible values; however, the total amount of possible combinations to evaluate can reach up to 1980, which would be very time-consuming, costly, and impossible to check:

Table 1.

The complete list of possible processing parameter values and limited ranges used in the experiment.

Additionally, each value that the process variable could take was also coded with an integer number starting from 1, for the lowest possible value.

The entire experiment was set up open-source source automated optimal experiment design software AutoOED [36]. This software was developed by the authors of DGEMO, the state-of-the-art MOBO algorithm [24].

An initial experiment data set size was set to 20 samples () which were prepared using three different approaches.

The first general situation (V1) is to set up an experiment without any preliminary data. In this case, the initial data set with a batch size of q was suggested by the AutoOED software (v. 0.2.0), using a Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS).

The second approach (V2) applies the use of a quasi-uniform random subset selection procedure to the discrete design space . The initial random sampling was iteratively adjusted in a deterministic manner to obtain a near-uniform marginal distribution of parameter values. Let the ideal marginal count for factor j at level l be:

such that . For a candidate set , define the imbalance functional.

We seek:

A practical greedy algorithm (Algorithm 1):

| Algorithm 1: Balanced-Marginal Selection (Greedy Correction) |

| 1: Sample uniformly from with 2: while improvement exists do 3: For each and , consider swap . 4: If , accept the best swap and update . 5. end while 6. Return . |

And then the third approach (V3) used the data from other experiments that were conducted based on three level fractional factorial experiment, that covers the same experimental design space (the same ranges of possible processing parameter values).

Let and define a 3-level orthogonal array with d = 4 columns:

Map each column via a level map . Let . Select a subset , maximizing a dispersion criterion (maximin in coded space):

then

After providing the initial experimental data (one of V1–V3), the MOBO loop proposes the next batch of 10 processing parameter sets (experiments) to evaluate (q = 10). Two separate paths were selected, using DGEMO [24] and TSEMO [25] algorithms, both designed to suggest batches of the next experiments to perform.

Let be the data after iteration t, where are observed. Gaussian process surrogate models yield posteriors for . Given an acquisition and batch size q (here ), the next batch is:

In this research, the MOBO runs for T = 3 iteration:

where is obtained by DGEMO or TSEMO as in the batch rule above.

Consecutive runs were conducted for each algorithm used, which gives in total 18 batches to build and evaluate. In total, 180 samples were fabricated and analyzed.

After the experiments, the pareto front evolution ()

and hypervolume improvement

with respect to a fixed reference datapoint r

were selected as an evaluation metric for each selected optimization path.

3. Results and Discussion

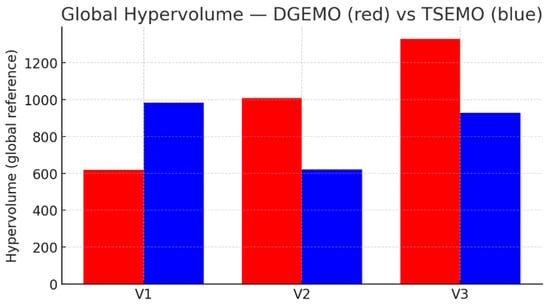

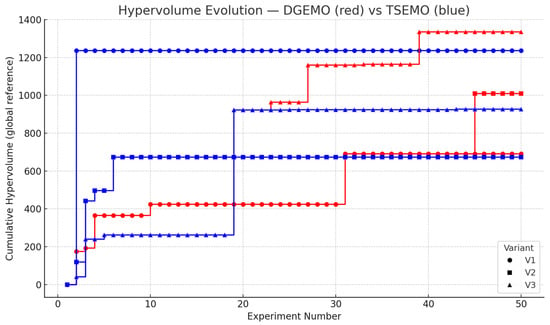

Figure 3 and Table 2 present the comparison of hypervolume (HV) values obtained for both optimization algorithms—DGEMO and TSEMO—across all three initialization variants (V1–V3). Although TSEMO is often characterized as achieving rapid early convergence due to its Thompson-sampling mechanism, the results obtained in this study reveal a more nuanced relationship between the two algorithms. It is important to note that the existing literature does not provide grounds for expecting TSEMO to outperform DGEMO. On the contrary, DGEMO was introduced as an advancement over established MOBO approaches and has been empirically shown to surpass baseline methods, including TSEMO, on a majority of benchmark problems in terms of hypervolume indicator and surrogate-model prediction accuracy [24]. TSEMO itself is reported to perform competitively against algorithms such as NSGA-II, ParEGO, and EHV [25], but the original DGEMO publication demonstrates that DGEMO consistently achieves higher diversity and broader Pareto front coverage. In light of these algorithmic characteristics, it is unsurprising that while TSEMO tends to converge more rapidly in the early stages of exploration, DGEMO achieves comparable or even higher HV values in several cases, particularly for Variant V3. This suggests that DGEMO’s stronger exploratory bias allows it to maintain a wider spread of candidate solutions within the design space, which may ultimately lead to more extensive Pareto coverage. Therefore, rather than assuming a specific ranking of performance between the algorithms, we found their differing exploration–exploitation strategies to manifest in distinct convergence behaviours, which is consistent with the trends observed in the experimental results.

Figure 3.

Comparison histogram of Hypervolume values (HV) obtained after the full optimization run (initial dataset + three MOBO iterations) for each initialization strategy (V1–V3) and each algorithm (DGEMO, TSEMO).

Table 2.

Hypervolume values (HV) obtained after the full optimization run (initial dataset + three MOBO iterations) for each initialization strategy (V1–V3) and each algorithm (DGEMO, TSEMO).

In the present dataset, the variant V3 yielded the highest overall HV for both algorithms, followed by V2 and then V1. This suggests that the sampling approach used in V3, though more stochastic, enabled broader global coverage of the process design space. Although the effect of initial sampling is not explicitly discussed in the works by [37,38,39], the importance of well-distributed initial samples for the accuracy of Gaussian Process surrogate models is well-established in the surrogate modelling literature. Space-filling designs improve global prediction accuracy by ensuring that Gaussian Process surrogates are trained on samples spanning the full variation in the input space. In contrast, clustered or poorly distributed samples restrict the surrogate’s ability to resolve local nonlinearities, which directly affects hypervolume growth in early MOBO iterations [40,41].

TSEMO’s behaviour, rooted in the Thompson-sampling mechanism, focuses on probabilistic exploitation of high-confidence regions, often yielding fast initial gains but with reduced diversity. DGEMO, on the other hand, maintains a broader sampling strategy, trading off early convergence speed for sustained exploration. Such characteristics make DGEMO advantageous when the process model is highly nonlinear or when hidden correlations between process parameters still need to be captured.

Overall, both algorithms exhibit complementary behaviours: TSEMO achieves faster initial improvement, while DGEMO provides broader and more stable coverage of the design space within the same experimental budget of 50 trials.

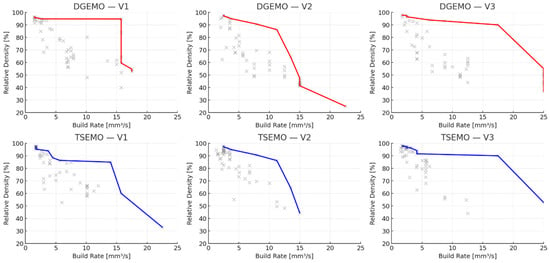

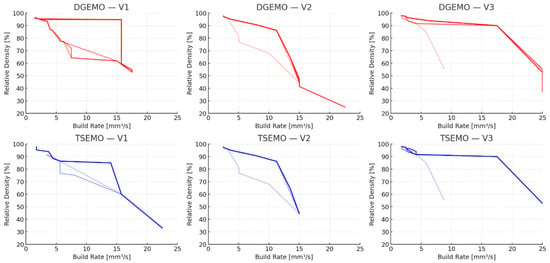

Figure 4 illustrates the resulting Pareto fronts for all six optimization pathways (DGEMO/TSEMO × V1–V3).

Figure 4.

Pareto front grid.

A clear trade-off between Relative Density and Build Rate is visible across all variants. Lower-energy processing conditions favour higher productivity at the expense of density, whereas higher energy input increases densification but reduces throughput. This relationship aligns with the classical productivity–quality compromise observed in PBF-LB/M.

To support this discussion, Supplementary Table S1 provides the full dataset of process parameters, including the calculated volumetric energy density (VED), which in the present study spanned approximately 20–120 J/mm3. Lower VED values corresponded to faster build rates and higher porosity, while higher VED values led to more complete melting and higher densities.

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the hypervolume values over consecutive experimental. The curves are monotonically non-decreasing, as HV increases only when a new experiment expands the dominated region of the objective space.

Figure 5.

Hypervolume evolution.

Importantly, the first 20 experiments correspond to the initial input data (Variants V1–V3) and were not generated by optimization algorithms. Algorithm-driven improvements therefore occur only beyond iteration 20, when DGEMO and TSEMO begin proposing new parameter combinations.

TSEMO demonstrates rapid improvement immediately after initialization, reaching a near-steady HV by experiment 5–20. DGEMO shows a more gradual, stepwise increase with small but continuous gains even at later stages, indicating a more persistent exploration mode. This contrast supports the notion that TSEMO prioritizes fast exploitation, whereas DGEMO maintains exploratory robustness useful for capturing nonlinear or multi-modal responses.

The combined Pareto front visualization (Figure 6) highlights that both algorithms ultimately approximate similar trade-off regions between Build Rate and Relative Density. TSEMO fronts tend to cluster more tightly, while DGEMO fronts are broader and slightly more scattered, especially in Variant V3.

Figure 6.

Comparative Pareto fronts evolution across experiment stages.

Overall, the joint representation confirms that both algorithms successfully delineated a well-defined trade-off frontier, supporting the observed consistency between their respective Pareto approximations.

A diagnostic analysis of parameter-space similarity revealed a high proportion of duplicate or near-duplicate points in several experimental batches, in some cases reaching 60–80% of all points (Table 3). Such repetition stems primarily from the lack of distance-based penalization in batch candidate selection, combined with discrete parameter resolution in the machine tool.

Table 3.

Duplicate statistics and HV calculation results for deduplicated dataset.

The deduplication analysis was performed in silico and should be interpreted with caution. In two cases (V2–DGEMO and V3–TSEMO), the simulated removal of redundant points resulted in modest HV increases (+4–5%), indicating that excessive clustering can limit early exploration. However, in the remaining cases, HV decreased because the removed points were located near the Pareto boundary. Thus, deduplication does not inherently improve performance; rather, it illustrates the sensitivity of HV evaluation to sample distribution in a discretized design space. In other cases, HV decreased slightly, which can be attributed to the removal of points lying on or near the Pareto boundary—reducing the number of extremal solutions retained after filtering.

These results indicate that excessive duplication reduces learning efficiency, although controlled replication (intentional repetition of promising settings) remains beneficial in late optimization phases, when the model’s uncertainty must be evaluated rather than expanded.

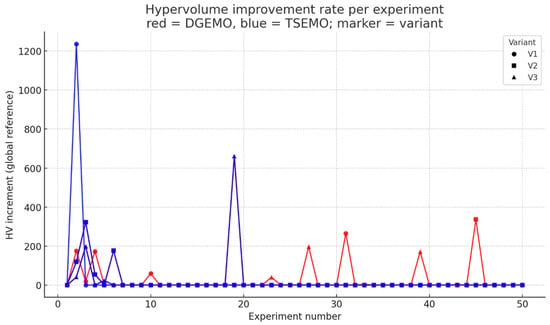

The analysis of hypervolume improvement rate (Figure 7) clearly shows that most performance gains occurred during the initial, pre-optimization phase (experiments 1–20), which corresponds to the baseline input datasets (Variants V1–V3). During this stage, the experimental points substantially expanded the dominated region of the objective space, establishing a well-defined Pareto frontier between Build Rate and Relative Density.

Figure 7.

HV improvement rate per iteration and identification of saturation points for DGEMO and TSEMO.

In contrast, after iteration 20—when the DGEMO and TSEMO algorithms began generating new candidates—the curves flattened almost completely, indicating that the optimization algorithms operated within an already saturated design space. Only a few small hypervolume increments were observed in later iterations, mostly for DGEMO, reflecting minor local refinements rather than genuine discovery of new trade-off regions.

This behaviour implies that the initial sampling strategies already provided sufficiently diverse and near-optimal coverage of the parameter space, allowing the algorithms to confirm existing optima rather than discover new ones. In other words, the optimization phase primarily served as a validation step rather than a driver of additional improvement.

Such convergence saturation is typical when the baseline dataset densely covers the feasible domain or when parameter discretization limits the number of unique process combinations that can be explored. The duplicate-point analysis (Table 3) supports this conclusion: up to 60–80% of the tested configurations were identical or nearly identical in the scaled parameter space, greatly reducing effective search diversity.

Simulated deduplication revealed that removing redundant points sometimes improved hypervolume (e.g., V2–DGEMO + 4.9%, V3–TSEMO + 4.1%), while in other cases it slightly decreased it due to the loss of extremal boundary points. These observations highlight that while duplication hinders exploration, a controlled degree of replication can still be advantageous for assessing measurement noise, experimental reliability and model uncertainty near the Pareto boundary.

Although the optimization algorithms did not discover substantially better trade-offs beyond the initial dataset, this outcome is consistent with the narrow and highly constrained processability window characteristic of AZ31 magnesium alloy. In this context, the MOBO framework served its role not only as a search tool but also as a validation mechanism, confirming that a well-designed initial sampling strategy may already capture most of the feasible design space.

This insight is central to the generalizable methodology proposed in this work: the efficiency of MOBO in complex additive manufacturing systems depends strongly on the structure of the initial dataset, parameter resolution, and the physical constraints of the material. The analysis of duplicates and deduplication demonstrates how data-efficiency principles can be transferred to other alloys and process classes, supporting the broader goal of developing a scalable, automated optimization workflow.

4. Conclusion

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) for process parameter tuning in Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Metals (PBF-LB/M) using AZ31 magnesium alloy as a case study. Two MOBO algorithms, DGEMO and TSEMO, were implemented within the AutoOED framework to simultaneously maximize relative density and build rate.

The results show that MOBO can efficiently approximate the Pareto front with a significantly reduced number of experiments compared to conventional Design of Experiments (DoE) strategies. Among the tested initialization strategies, Variant V3 produced the highest final hypervolume values for both algorithms, whereas V2 yielded the most uniform and well-distributed Pareto front. Thus, V3 was optimal in terms of objective-space coverage, while V2 offered superior structural diversity of the front. TSEMO demonstrated faster convergence and higher Pareto front quality in early iterations, while DGEMO preserved greater diversity across the search space—an advantage for exploratory studies.

The present findings indicate that the optimization efficiency is strongly shaped by the initialization strategy and the discretized nature of industrial PBF-LB/M design spaces. Building on these insights, future research will focus on three directions.

First, refining batch-selection strategies by introducing distance-based penalization or adaptive resolution may reduce duplication and sustain hypervolume growth beyond the saturation observed here.

Second, running a secondary MOBO stage restricted to the high-potential region identified in this study may enable finer exploration of the local process landscape.

The developed workflow offers a generalizable methodology for data-efficient optimization of additive manufacturing processes, combining statistical modelling with experimental automation. Future work should focus on expanding this framework to other alloys and process classes, incorporating additional objectives such as surface quality or residual stress, and integrating in situ sensing for adaptive optimization.

Finally, future comprehensive studies will include a detailed microstructural, chemical and mechanical evaluation of Pareto-optimal samples, enabling correlations between the MOBO-identified process windows and their resulting microstructure, local chemistry and mechanical performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412968/s1, Table S1: Full dataset of process parameters and experiment results.

Funding

This work was supported by a pro-quality subsidy granted by the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, under the “Excellence Initiative—Research University” programme for 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- ISO/ASTM 52900:2021(E); Additive Manufacturing-General Principles-Fundamentals and Vocabulary. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Dejene, N.D.; Lemu, H.G. Current Status and Challenges of Powder Bed Fusion-Based Metal Additive Manufacturing: Literature Review. Metals 2023, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, T.G.; Gold, S.A. In-process sensing in selective laser melting (SLM) additive manufacturing. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2016, 5, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzynowski, T.; Pawlak, A.; Chlebus, E. Processing of Magnesium Alloy by Selective Laser Melting. In Proceedings of the 14th International Scientific Conference: Computer Aided Engineering, Wrocław, Poland, 20–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Rosienkiewicz, M.; Chlebus, E. Design of experiments approach in AZ31 powder selective laser melting process optimization. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2017, 17, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, A.; Jäcklein, M.; Schlager, M.; Harwick, W.; Hoschke, K.; Balle, F. An Empirical Approach for the Development of Process Parameters for Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2020, 13, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Hao, L.; Li, Y.; Tang, D.; Cui, Q.; Feng, Z.; Yan, C. Effect of selective laser melting parameters on morphology, microstructure, densification and mechanical properties of supersaturated silver alloy. Mater. Des. 2019, 170, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiju, A. Design of Experiments for Engineers and Scientists, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Geng, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Han, Y. Review: Multi-objective optimization methods and application in energy saving. Energy 2017, 125, 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, H.; Kita, H.; Kobayashi, S. Multi-objective optimization by genetic algorithms: A review. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, Nagoya, Japan, 20–22 May 1996; pp. 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branke, J.; Deb, K.; Roman, S. Multiobjective Optimization, Interactive and Evolutionary Approaches; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, J.; Cui, H.; Wei, L.; Fan, R. MOEA3D: A MOEA based on dominance and decomposition with probability distribution model. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.I. A Tutorial on Bayesian Optimization. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.02811v1 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process Syst. 2012, 4, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Liu, H. Impact of exploration-exploitation trade-off on UCB-based Bayesian Optimization. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1081, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J.; Nguyen, V.; Gupta, S.; Rana, S.; Venkatesh, S. Exploration enhanced expected improvement for bayesian optimization. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Dublin, Ireland, 10–14 September 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Papenmeier, L.; Cheng, N.; Becker, S.; Nardi, L. Exploring Exploration in Bayesian Optimization. Proc. Mach. Learn Res. 2025, 286, 3388–3415. [Google Scholar]

- Pelamatti, J.; Brevault, L.; Balesdent, M.; Talbi, E.-G.; Guerin, Y. Bayesian Optimization of Variable-Size Design Space Problems. 2020. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.03300 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chen, J.; Luo, F.; Li, G.; Wang, Z. Batch Bayesian optimization with adaptive batch acquisition functions via multi-objective optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 79, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, A.; Verdinelli, I. Bayesian Adaptive Randomization with Compound Utility Functions. Statist. Sci. 2023, 38, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, R.; Lin, Z.J.; Bakshy, E.; Frazier, P.I. qEUBO: A Decision-Theoretic Acquisition Function for Preferential Bayesian Optimization. Proc. Mach. Learn Res. 2023, 206, 1093–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, W.F.; Gerstoft, P.; Park, Y. Bayesian optimization with Gaussian process surrogate model for source localization. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agasiev, T.; Karpenko, A. Exploratory Landscape Validation for Bayesian Optimization Algorithms. Mathematics 2024, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konakovic, M.; Tian, Y.; Matusik, W. Diversity-Guided Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization With Batch Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020), Online, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, E.; Schweidtmann, A.M.; Lapkin, A. Efficient multiobjective optimization employing Gaussian processes, spectral sampling and a genetic algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2018, 71, 407–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktepe, E.; Ergün, U.; Aktepe, E.; Ergün, U. Machine Learning Approaches for FDM-Based 3D Printing: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhong, J.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Accelerating lPBF process optimisation for NiTi shape memory alloys with enhanced and controllable properties through machine learning and multi-objective methods. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2364221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Deng, B.; Shou, W.; Oh, T.-H.; Hu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Shi, L.; Matusik, W. Computational discovery of microstructured composites with optimal stiffness-toughness trade-offs. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Elvitigala, K.C.M.L.; Mubarok, W.; Okano, Y.; Sakai, S. Machine learning-based prediction and optimisation framework for as-extruded cell viability in extrusion-based 3D bioprinting. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2400330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, C.; Xu, Y.; Sing, S.L. Machine learning applications for quality improvement in laser powder bed fusion: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. AI Mater. Des. 2024, 1, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.; Sousa, A.; Brueckner, F.; Reis, L.P.; Reis, A. Human-in-the-loop Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization for Directed Energy Deposition with in-situ monitoring. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Izquierdo, D.S.; Vinel, A.; Shamsaei, N.; Shao, S. A review of machine learning techniques for process and performance optimization in laser beam powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 34, 3249–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K.; Mackiewicz, A.; Stopyra, W.; Dziedzic, R.; Kurzynowski, T. Development of manufacturing method of the MAP21 magnesium alloy prepared by selective laser melting (SLM). Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2019, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Szymczyk, P.; Kurzynowski, T.; Chlebus, E. Selective laser melting of magnesium AZ31B alloy powder. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM F3637−23; Standard Guide for Additive Manufacturing of Metal Finished Part Properties Methods for Relative Density Measurement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Konakovic Lukovic, M.; Erps, T.; Foshey, M.; Matusik, W. AutoOED: Automated Optimal Experiment Design Platform. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/autooed-sim (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Knowles, J. ParEGO: A hybrid algorithm with on-line landscape approximation for expensive multiobjective optimization problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belakaria, S.; Deshwal, A.; Doppa, J.R. Max-value Entropy Search for Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization with Constraints, 2020. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2009.01721 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Hernández-Lobato, D.; Hernández-Lobato, J.M.; Shah, A.; Adams, R.P. Predictive Entropy Search for Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization, 2015. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1511.05467 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Santner, T.J.; Williams, B.J.; Notz, W.I. The Design and Analysis of Computer Experiments; Santner, T.J., Williams, B.J., Notz, William, I., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loeppky, J.L.; Sacks, J.; Welch, W.J. Choosing the Sample Size of a Computer Experiment: A Practical Guide. Technometrics 2009, 51, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).