Featured Application

A process of brown onion skin transformation into a cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier oriented toward the “zero waste” model of circular economy has been proposed. A BOS-derived enzyme immobilization carrier has been proven as suitable for Burkholderia cepacia lipase immobilization by adsorption.

Abstract

The present study aimed to design a process of brown onion skin transformation by sequential extraction to a cellulose-based immobilization carrier, along with detailed analysis of obtained extracts, pointing to approaching a “zero-waste” model of circular economy. The process of brown onion skin transformation started with semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction via consecutive use of five solvents of increasing polarity (96, 75, 50, and 25% ethanol and water), followed by alkaline liquefaction of solid residue by 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide. The designed BOS transformation process resulted in 16.62 g of cellulose-based immobilization carrier derived from 100 g of brown onion skin. Extracts obtained by semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction contained 37 mg/g of proteins, 40 mg/g of sugars, 17.5 mg/g of uronic acids, 28 mg/g of polyphenols, and 36 mg/g of flavonoids, while those obtained by alkaline liquefaction 19 mg/g of proteins, 58 mg/g of sugars, 10 mg/g of uronic acids, 6.6 mg/g of polyphenols, and 0.5 mg/g of flavonoids. The suitability of the cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier was evaluated by B. cepacia lipase immobilization by adsorption, where a maximal 31 U of lipase activity per 1 g of wet carrier was achieved. Based on the results obtained, it seems that the proposed process of brown onion skin transformation shows the possibility of being used for the production of a cellulose-based immobilization carrier, approaching the “zero-waste” model of a circular economy.

1. Introduction

Brown onion skin (BOS) is residual waste generated during industrial packhouse processing of brown onions, part of onion waste from the industrial processing of brown onions for the production of various food products, as well as part of onion biowaste generated in kitchen households during cooking, whose worldwide annual amount ranges from 500,000 to 600,000 tons [1,2,3,4]. Unfortunately, even nowadays, the majority of BOS generated worldwide ends up in landfills, simply due to the fact that it cannot be used for animal feeding due to the strong onion aroma, nor as fertilizer due to the possibility of pathogen development [2,3,5,6]. However, if one considers its chemical composition, it is more than clear that BOS presents a valuable raw material for various industries, including food, pharmaceutical, medical, chemical, and cosmetics. Brown onion skin is a low-moisture material (4–10%) that contains a significant amount of insoluble dietary fiber ranging from 44 to 70% [4,5,7], with cellulose comprising almost half of it [8]; 1.7 to 8.2% of soluble dietary fiber [4,5,7]; between 2.3 and 6.1% of crude proteins; crude fat ranging from 0.3 up to 6.5% [4,9,10,11,12]; ash content between 2.6 and 12.3% [4,5,7,9,10,11,12]; and total phenolics ranging from 5.2 up to 11.2%, among which flavonoids and flavanols with the dominance of quercetin and its glycosides, are the most abundant [4,5,9]. In addition, the presence of anthocyanins (0.29–0.38%) [4,12] and a small amount of alkenyl cysteine sulfoxides (4.6 μmol/g) [5] should not be neglected.

Therefore, it is not surprising that numerous studies on BOS potential utilization have been carried out. Besides those oriented toward detailed BOS chemical analysis [5,7,12], the majority of up-to-date research was oriented toward utilization of BOS-bioactive components, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, flavanols, including quercetin and its glycosides, or non-structural carbohydrates using various types of extraction [4,10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. On the other hand, according to our knowledge, there is only one research dealing with the possibility of the production of cellulose microfibers from BOS [8]. Therefore, the need for the design of the process of BOS transformation oriented toward a “zero-waste” model of circular economy still exists.

One of the potential possibilities for BOS utilization is its transformation into a cellulose-based carrier for enzyme immobilization, since it contains up to 70% of insoluble dietary fibers, of which approximately half is cellulose [4,5,7,8]. The use of lignocellulosic materials derived from various agri-food industrial wastes and cellulosic materials for enzyme immobilization is well documented [24]. Various enzymes have been immobilized on lignocellulosic material derived from rice bran [25,26], corn stalks [27], coconut husks [27,28], palm stalks [27], spent coffee grounds [29,30], or cellulosic materials, including loofah sponges [31], cotton fabric [32], cotton yarn [33], cotton buds, disk make-up remover, and cotton and linen tissues [34]. Strikingly, so far, there has been no report on the possibility of enzyme immobilization onto brown onion skin, probably due to the fact that it has been designated as a rich source of bioactive components [4,10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] with solid residue obtained after extraction as a promising fuel due to its high heating value [13,14,21]. However, few reports on the ability of enzyme immobilization on the inner epidermis of onion bulb scale, including immobilization of pancreatic lipase intended for milk fat hydrolysis and glucose oxidase for the development of a glucose biosensor [35,36,37], have been reported.

Encouraged by our previous report on the ability of the production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier derived from spent coffee grounds by multi-step extraction [38] and the fact that lipases immobilized onto it show practical utilization in high-lipid-loaded wastewater treatment and the production of cocoa butter substitute [30], here we report the possibility of the production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier derived from brown onion skin using sequential extraction transformation. The process of BOS transformation started with semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction (ScSeqSubE) by consecutive use of 96, 75, 50, and 25% ethanol and finally water, followed by alkaline liquefaction of the remaining solid residue with a 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide. The remaining solid residue, BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier, was tested on desired carrier properties and immobilization suitability by immobilizing Burkholderia cepacia lipase via immobilization by adsorption. In addition, each of the extracts obtained during BOS-transformation was tested on the targeted compound composition in order to designate its possible use.

Based on the results obtained, it seems that the proposed process of BOS sequential extraction transformation has the potential to be used for the production of BOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier together with a few other “high-value” added products, and present an additional step toward sustainable brown onion skin transformation approaching a “zero waste” model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

Brown onion skin from the industrial packhouse processing of brown onions (Figure S1) has been generously supplied by Enna Fruit d.o.o. (Dugo Selo, Croatia).

Semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of brown onion skin (BOS) was performed with different aqueous ethanolic solutions prepared from 96% ethanol obtained from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia), while alkaline liquefaction of the solid residue obtained after ScSeqSubEof brown onion skin (SEBOS) by aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) prepared from NaOH pellets purchased from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia).

Quercetin and quercetin-3 glucoside purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), quercetin-4-glucoside and quercetin-3,4-glucoside from Extrasynthese (Genay, France) were used as authentic standards of phenolic compounds used for the construction of calibration curves (HPLC) and sample spiking, while glucose and xylose purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), arabinose from LGC-TRC (Vaughan, ON, Canada) and rhamnose from Byosinth (Staad, Switzerland) as authentic standards for the construction of examined sugars calibration curves (HPLC).

Glucose obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), sulfuric acid (95–97%) from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia), and phenol from Lach-Ner (Neratovice, Czech Republic) were used for the construction of a calibration curve for the determination of total sugars by the phenol: sulfuric acid method. Bovine serum albumin purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for the construction of a calibration curve for the determination of proteins by the Bradford method. Glucuronic acid, carbazole, and sodium tetraborate decahydrate obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), sulfuric acid (95–97%) from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia), and absolute ethanol from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia) were used for the construction of a calibration curve for the determination of uronic acid by the carbazole method. Quercetin hydrate purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and sodium carbonate anhydrous from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia) were used for the construction of calibration curve for determination of total polyphenols, while for total flavonoid content determination besides quercetin hydrate, anhydrous aluminum chloride obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and sodium nitrite from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia) were used.

Amano lipase PS from Burkholderia cepacia (≥30,000 U/g) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 prepared from sodium dihydrogen phosphate anhydrous and di-sodium hydrogen phosphate anhydrous from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) were used for Burkholderia cepacia lipase immobilization by adsorption onto BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier. Olive oil, gum Arabic, sodium dihydrogen phosphate anhydrous, and di-sodium hydrogen phosphate anhydrous obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), acetone and 96% ethanol from LabExpert (Ljubljana, Slovenia), volumetric standard of sodium hydroxide (0.1 mol/L), sodium chloride and glycerol from Gram-mol (Zagreb, Croatia) were used for the titrimetric determination of lipase activity.

All other chemicals used in this research were of pro-analysis purity.

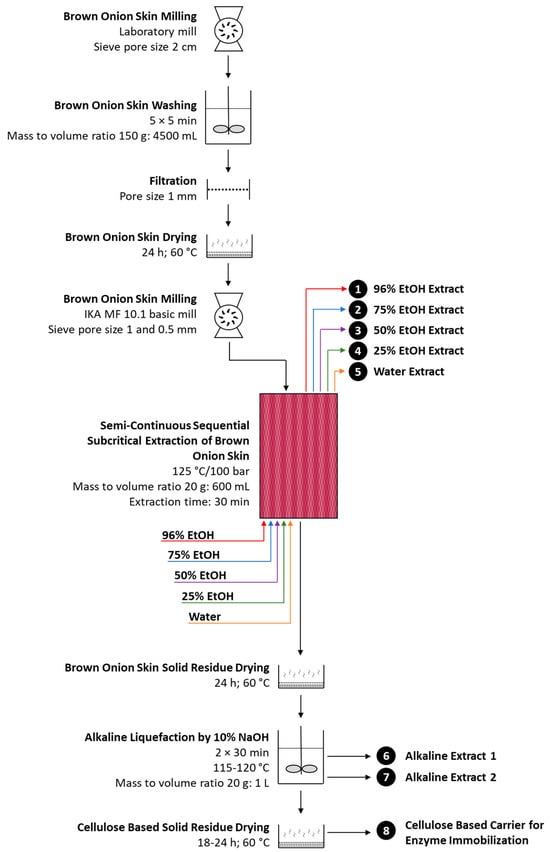

2.2. Semi-Continuous Sequential Subcritical Extraction of Brown Onion Skin

Prior to the performance of semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction, it was necessary to adequately prepare brown onion skin for the extraction process. Preparation included: (a) initial milling of originally supplied brown onion skin (Figure S1) to particle size of 2 cm using laboratory mill (Albrigi Luigi s.r.l., Verona, Italy) (b) tap water washing of milled BOS 5 × 5 min in mass to volume ratio 1:30 followed by subsequent filtration through plastic sieve of 1 mm pore size in order to remove impurities, (c) drying of washed BOS at 60 °C during 24 h, and (d) dried BOS particle size reduction to less than 0.5 mm by double milling on laboratory mill IKA MF 10.1 basic grinder (IKA, Staufen, Germany) where first milling included passage of milled BOS through sieve of pore size 1 mm, and second through sieve of pore size 0.5 mm (Figure 1) in order to obtain material of particle size suitable for enhanced subcritical extraction as reported by Munir and coworkers [20].

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the multistep extraction and transformation of brown onion skin.

Semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of prepared BOS was performed with five solvents of increasing polarity (96% EtOH, 75% EtOH, 50% EtOH, 2% EtOH, and distilled water) in a system designed for laboratory subcritical extraction, well described in our previous work [38]. A mass of 20 g of BOS of average particle size diameter of 364 µm (Figure S2) was added to the extractor equipped with Teflon coated mixing stirrer, followed by hermetical sealing of the extractor, and subsequent filling of the extractor chamber from the bottom at an initial 50 bars with 600 mL 96% ethanol pre-heated to ~125 °C. Once suspension of BOS in 96% ethanol in the extractor chamber with continuous stirring of mixing stirrer set at 250 rpm reached desired temperature of 125 °C and pressure of 100 bars (approximately 20 min), extraction process continued for 30 min. Thermal stability of the system was monitored by an internal temperature sensor K-type thermometer (model DT-610B) positioned in the center of the extraction vessel. Afterwards, the extract was released, a new preheated solvent of increased polarity (75% EtOH) was introduced to the extractor, and the extraction process continued. The process was repeated with 50 and 25% EtOH. ScSeqSubE ended with water extraction, followed by drying of the remaining solid residue (SEBOS; sequentially extracted brown onion skin) at 60 °C for 24 h. Obtained extracts (96% EtOH, 75% EtOH, 50% EtOH, 25% EtOH, water) were analyzed on chemical composition, while SEBOS, besides the determination of chemical composition, was used for alkaline liquefaction.

2.3. Alkaline Liquefaction of Sequentially Extracted Brown Onion Skin

Alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS was performed by the procedure described in our previous work [38]. In a preliminary study, 20 g of SEBOS was mixed with 1000 mL of aqueous sodium hydroxide solutions (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10%), and alkaline liquefaction with continuous stirring and reflux was performed 2 × 30 min at 115–120 °C. Afterwards, solid residue (ALSEBOS; alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin) was separated by vacuum filtration through Whatman 113 filter paper, washed with distilled water until the pH of the filtrate reached pH = 7, washed with acetone, and dried at 60 °C for 24 h. Dried ALSEBOSs were analyzed for leakage and chemical composition by FTIR-ATR.

Leakage of ALSEBOS was performed by a procedure well-described in our previous paper [38].

Once the optimal sodium hydroxide percentage was found (10%), based on the lack of leakage from ALSEBOS, the process of alkaline liquefaction with 10% sodium hydroxide solution was performed at the above-mentioned conditions, in several independent extractions. Obtained alkaline extracts were examined on chemical composition, while ALSEBOS besides determination of chemical composition on the selected physical characteristics, was used for lipase immobilization by adsorption.

2.4. Physical-Chemical Analysis of Brown Onion Skin and Solid Residues Obtained After Subcritical Extraction and Alkaline Liquefaction

BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS were analyzed on chemical composition by standard methods, as well as by infrared spectroscopy. Dry matter content was determined by drying the samples at 103 °C to a constant mass, protein content by the Kjeldahl method, and ash content by combustion of the samples at 500 °C for 4 h in a muffle furnace. Fat content was determined by Soxhlet extraction with n-hexane at a mass/volume ratio of 1:30 using a SoxROC SX-360 extractor (Opsis Liquidline, Furulund, Sweden). The crude fibers were analyzed according to the ISO 6865:2000 method [39], while the total polyphenol and flavonoid content was determined according to Matić et al. [40]. Infrared spectra recordings of BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS were performed on a Carry 630 FTIR ATR spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in the range from 650 to 4000 cm−1.

Physical characterization of BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS included: determination of particle size distribution, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Particle size distribution was determined by the laser light scattering method using the Mastersizer Scirocco analyzer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK), where the results obtained were the averages of three independent measurements. The physisorption analysis was performed at a temperature of −196 °C (liquid nitrogen) operating with Autosorb IQ (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, FL, USA). Using a fixed 52-point p/p0 table, the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were gained. In addition, to extract impurities and moisture from the pores, the brown onion skin samples were pretreated under vacuum for 12 h at a temperature of 110 °C. Applying the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, which is based on the physical adsorption of nitrogen molecules onto a solid surface in the range of 0.05–0.3 p/p0, the specific surface areas were calculated. The total pore volumes were acquired in fixed single point p/p0 of 0.99, while the pore sizes were measured using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. SEM analysis was used to determine differences in surface morphology between BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS. Before analysis, all samples were deposited on a thin layer of gold (10 nm) to obtain better quality micrographs and were analyzed at different magnifications (from 500× up to 2000×) using a Hitachi TM 3030 electron microscope (Hitachinaka, Japan).

2.5. Chemical Analysis of Extracts

Extracts obtained from ScSeqSubE of brown onion skin (96%, 75%, 50%, 25% EtOH and water) were examined on dry matter content, amount of extractable proteins, sugars, polyphenols and flavonoids, on the content of specific flavonoids and monosaccharides, uronic acid content, as well as by UV-Vis spectra recordings. In the case of alkaline liquefaction, extracts of SEBOS obtained by 10% aqueous sodium hydroxide analysis of chemical composition included determination of extractable proteins, sugars, polyphenols and flavonoids, and uronic acid content. Dry matter content determination was performed by drying of 10 mL aliquot at 103 °C to constant mass, protein content by Bradford method [41], sugar content by phenol: sulfuric acid method according to Yue et al. [42], total polyphenols and flavonoids according to Matić et al. [40], while uronic acid content by carbazole method according to Bitter and Muir [43].

UV-Vis spectra of extracts obtained after subcritical extraction were recorded in the range from 200 to 500 nm using a UV-Vis 1280 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany). Prior to the spectra recordings, extracts were diluted tenfold with the appropriate extraction solvent.

Specific monosaccharides (arabinose, glucose, rhamnose, and xylose) in the extracts were analyzed HPLC system equipped with a RID-10AD refractive index detector, LC-20AD prominence solvent delivery module, DGU-20A5R degassing unit, and SIL-10AF automatic sample injector (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany). Prior to HPLC analysis, it was necessary to prepare the extracts. The first step of preparation included standardization of extracts to 80% ethanol content by adding a certain amount of absolute ethanol to 75, 50, and 25% EtOH extracts, as well as to the water extracts, while in the case of 96% EtOH extract, by addition of a certain amount of deionized water. From standardized extracts, an aliquot of 10 mL was transferred to a centrifuge tube, allowed to stand 30 min at room temperature, and clarified by centrifugation using Sigma 2-16 centrifuge (Sigma Laborzentrifugen GmbH, Osterode am Harz, Germany) at 1448× g (3 000 rpm; rotor 267/D). The supernatants obtained were decanted and concentrated by evaporation to a volume of 2 mL, followed by subsequent filtration through a 0.22 μm nylon syringe filter into the vial. Monosaccharide separation was performed on a Zorbax NH2 column of 4.6 × 250 mm and 5 µm particle size (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 30 °C, using an injection volume of 10 µL and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and ultrapure water (80/20 v/v). Calibration solutions were prepared in the range of 0.1–10.0% and the obtained results were analyzed using LabSolution Lite Version 5.52 software.

Phenolic compounds were analyzed on a HPLC system (1260 Infinity II, with a quaternary pump, a PDA detector and a vial sampler, a Poroshell 120 EC C-18 column (4.6 × 100 mm, 2.7 µm), and a Poroshell 120 EC-C18 4.6 mm guard-column) (Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Two mobile phases were used for the analysis: 0.1% H3PO4 as a mobile phase A, and 100% methanol as a mobile phase B. A volume of 10 µL of samples was injected in the column, and compounds were separated with a following gradient (0 min 5% B, 5 min 25% B, 14 min 34% B, 25 min 37% B, 30 min 40% B, 34 min 49% B, 35 min 50% B, 58 min 51% B, 60 min 55% B, 62 min 80% B, 65 min 80% B, 67 min 5% B, 72 min 5% B) and a flow of 0.5 mL/min. The identification was based on the comparison of UV/Vis spectra and retention times of peaks from samples with those of authentic standards. Quantification was based on calibration curves constructed by measuring different concentrations of standards. Flavanols were quantified at 360 nm, and anthocyanins at 510 nm. Total flavanols were obtained by adding the areas of all peaks at 360 nm belonging to flavanols and quantified by the calibration curve of quercetin.

2.6. Immobilization of Burkholderia cepacia Lipase on BOS-Derived Cellulose-Based Immobilization Carrier

Burkholderia cepacia lipase (BCL) immobilization by adsorption on the produced BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier (ALSEBOS) was performed by a combination of methods of Ittrat et al. [27], Bonet-Ragel et al. [44], and Cui et al. [45]. Immobilization process was carried out over a period from 1 to 6 h with constant 360° stirring/rotation of the suspension of BCL and BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier suspension (0.5 g of carrier mixed with 10 mL of BCL of desired activity) in 15 mL Falcon tubes on Multi-Rotator PTR-60 (Grant-Instruments Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK) set at 17 rpm/min, at room temperature. BCL solutions in 50 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.5 (10 mL) exhibited desirable lipase activity of 320, 840, 1160, 1480, 2240 U per gram of carrier. The effect of time and lipase activity load on the immobilization was monitored by titrimetric determination of lipase activity [46], where the activity of immobilized BCL was expressed in units per gram of the wet carrier (U/g), and immobilization yield at optimal immobilization time calculated according to Trbojević Ivić et al. [47].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the obtained data included determination of average values and standard deviations using Microsoft Excel 365 software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

The present study aimed to design a process of brown onion skin transformation to a cellulose-based immobilization carrier. The main task set for a BOS transformation process design included: (a) BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier should be chemically and thermally stable, as well as insoluble under biocatalytic reaction conditions, (b) extracts obtained during BOS transformation should be thoroughly examined on its chemical composition in order to find their “niche” for the production of additional value-added products, and (c) BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier should be tested on desirable enzyme immobilization carrier properties, as well as on its suitability for immobilization of B. cepacia lipase by adsorption.

3.1. Transformation of Brown Onion Skin to a Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carrier: A Process Design Overview

The process of BOS transformation started with ScSeqSubE via consecutive use of five solvents of increasing polarity (96, 75, 50, and 25% EtOH and water), mass to volume ratio of 1:30, and temperature of 125 °C (Figure 1). It is well established that temperatures above 130 °C might lead to the increased extraction of structural carbohydrates from lignocellulosic materials and their partial degradation [13,38]. Therefore, a temperature of 125 °C was selected as the most prominent since the preparation of cellulose-based enzyme carrier from BOS was one of the tasks of the current research. Upon completion of subcritical extraction, the transformation process of solid residue continued by alkaline liquefaction, intended for lignin and other undesirable component removal. The use of alkaline liquefaction in the removal of multiple undesirable components (proteins, lignin, and remaining polyphenols) from sequentially extracted defatted spent coffee ground has been previously reported by our research group [38]. To achieve a chemically and thermally stable, and under biocatalytic reaction conditions, insoluble BOS-derived enzyme carrier it was necessary to find an optimal percentage of sodium hydroxide for alkaline liquefaction. In this respect, sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS) was exposed to several aqueous solutions of sodium hydroxide (2, 4, 6, 8, 10%) at 115–120 °C, and remaining solid residues (ALSEBOS; alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin) were examined for leakage. Since ALSEBOS obtained with a 10% aqueous solution of NaOH did not show leakage of proteins, polyphenols, and sugars, alkaline liquefaction using a 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide was designated as optimal. With the selection of optimal NaOH concentration, it was possible to complete the BOS-transformation scheme to cellulose-based carrier as shown in Figure 1.

During the development of the BOS transformation process, the major process streams, including obtained solid residues and brown onion skin as starting material, and extracts obtained during the transformation procedure, have been thoroughly examined on physical-chemical properties.

3.2. Physical-Chemical Characterization of Brown Onion Skin and Solid Residues Obtained During Transformation Process

As previously mentioned, the major task of the BOS transformation process was the production of a cellulose-based immobilization carrier that should be chemically and thermally stable, as well as insoluble under biocatalytic reaction conditions. In this respect, it was necessary to monitor the changes in chemical composition of obtained solid residues in comparison with starting material—brown onion skin (Table 1, Figure 2), as well as, physical changes including particle size distribution, specific surface area, total volume pore, pore diameter (Table 2, Figures S2–S5), solid residues color (Figure 3), and surface morphology (Figure 4). In addition, chemical and thermal stability and insolubility under biocatalytic reaction conditions were monitored by the determination of leakage of solid residues during the BOS-transformation process (Table S1). Finally, BOS transformation into cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier was evaluated by the changes in mass yield (Table S2 and Table 3).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of brown onion skin (BOS), sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS), and SEBOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier obtained after alkaline liquefaction (ALSEBOS). Results are presented as average values ± standard deviations of at least three independent determinations.

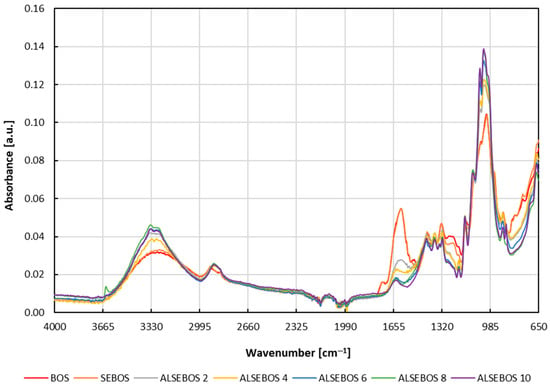

Figure 2.

FTIR-ATR spectra of solid residues obtained during the production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier from brown onion skin. Legend: BOS—brown onion skin; SEBOS—sequentially extracted brown onion skin; ALSEBOS 2, 4, 6, 8, 10—alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin (number 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 equals the NaOH percentage used for alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS).

Table 2.

Physical properties of brown onion skin (BOS), sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS), and SEBOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier obtained after alkaline liquefaction (ALSEBOS).

Figure 3.

Color changes in brown onion skin solid residues obtained during the production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier. Legend: BOS—brown onion skin; SEBOS—sequentially extracted brown onion skin; ALSEBOS 2, 4, 6, 8, 10—alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin (number 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 equals the NaOH percentage used for alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS).

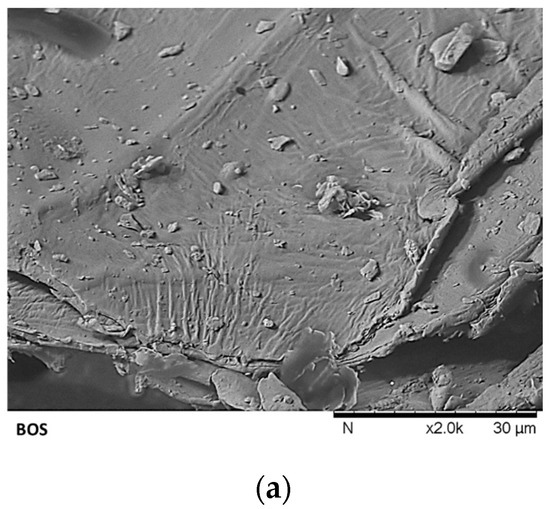

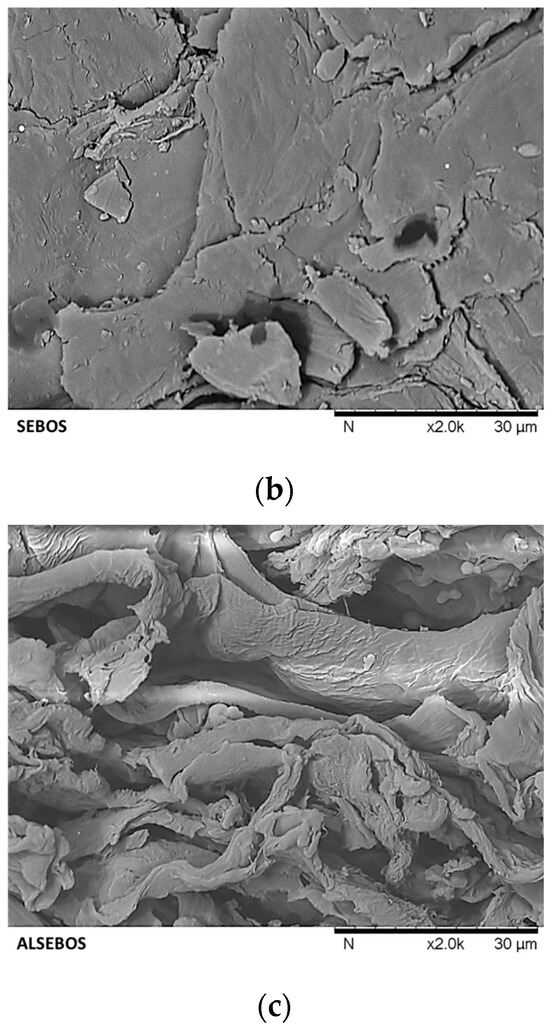

Figure 4.

Surface morphology of (a) brown onion skin (BOS), (b) sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS), and (c) alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin (ALSEBOS) determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 2000 magnification.

Table 3.

Mass yield of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier produced from brown onion skin. Results are presented as average values ± standard deviation of at least three independent determinations.

Initially prepared BOS (milling, washing, drying, milling; Figure 1) for the purpose of ScSeqSubE contained around 92.3% of dry matter with ~37.3% of crude fibers, ~10.8% of ash, ~4.3% of each, total polyphenols and flavonoids, ~3.1% of proteins and less than 1% of free fats (Table 1) what is congruent with previous reports on brown onion skin composition [4,5,9]. Application ScSeqSubE of BOS resulted in solid residue (SEBOS, sequentially extracted brown onion skin) of changed chemical composition and mass loss of ~24% in comparison to the BOS used for subcritical extraction. Obtained SEBOS was devoid of fats, contained at least 14-fold lesser amounts of total polyphenols and flavonoids, around 24% increased content of crude fibers, and apparently unchanged content of proteins and ash (Table 1). Subsequent use of alkaline liquefaction at optimal sodium hydroxide percentage (10%) resulted in solid residue (ALSEBOS) of 70% reduced mass in comparison to SEBOS (Table S2) and significantly changed chemical composition. ALSEBOS was found devoid of total polyphenols and flavonoids, containing ~71% of crude fibers, around 6.5% of ash, and less than 1% of proteins (Table 1). Changes in chemical composition of solid residues obtained during BOS transformation were well in accordance with our previous report on spent coffee ground transformation into cellulose-based immobilization carrier [38], where spent coffee ground-derived immobilization carrier contained a lower amount of crude fibers (~55%) and somewhat higher amount of proteins (1.1%) than ALSEBOS. In contrast to ALSEBOS (Table 1), rice husk-derived immobilization carrier was reported to contain 46.5% of cellulose, 31.9% of lignin, and 22.1% of pentosans [25].

Selection of 10% aqueous sodium hydroxide as optimal solvent for alkaline liquefaction was based on the lack of leakage of obtained ALSEBOS’s (Table S1). In a preliminary study prepared SEBOS was subjected to alkaline liquefaction with 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide, followed by leakage testing of the obtained solid residues. With an increasing percentage of aqueous sodium hydroxide obtained, ALSEBOS showed a decreased leakage of proteins, sugars, polyphenols, and flavonoids (Table S1), while ALSEBOS prepared with a 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide showed no detectable leakage.

Transformation of BOS to a cellulose-derived immobilization carrier was also monitored by infrared spectroscopy, more precisely, Fourier Transform Infrared-Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR). Prior to the FTIR-ATR spectra’s recording, BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS obtained after alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS with the use of various aqueous solutions of NaOH (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10%) were dried to a constant mass, to avoid any possible differences caused by variations in dry matter content, i.e., water content, which could alter the intensity of absorption bands of the samples [48]. FTIR-ATR spectrums of BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS showed almost identical position of centered peaks, but differences in peak absorbance intensities could be observed (Figure 2). The most pronounced differences in peak intensities could be noticed within the region between 985 and 1085 cm−1, where peaks centered at 1028 and 1054 cm−1, attributable to the C–O and C–O–C stretching vibrations of carbohydrates including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [48,49,50,51] had much higher intensities in ALSEBOS in comparison to BOS and SEBOS, being the highest in ALSEBOS prepared by alkaline liquefaction with 10% aqueous solution of NaOH (ALSEBOS 10). In addition, a slight increase in intensity of wide peak in the region between 2995 and 3665 cm−1 attributable to symmetric and asymmetric C–H stretching vibrations in CH, CH2, and CH3 groups of carbohydrates, symmetric and asymmetric stretching of NH groups, as well as OH intramolecular and intermolecular stretching in polysaccharides [49,51] has been noticed between BOS, SEBOS and ALSEBOS’s. Observed increase in peak intensities in these two regions was well in accordance with the detected increase in crude fiber content (Table 1). Decreased content of proteins, polyphenols, and flavonoids during BOS transformation could be observed by a decrease in peak intensities from BOS to ALSEBOS in the region between 1170 and 1770 cm−1. A wide peak between 1170 and 1310 cm−1 in BOS and SEBOS, obviously consisting of several overlapped peaks, found to disappear in ALSEBOS, could be attributed to C–N stretching and N-H in-plane bending of the amide III band of proteins, C–O stretching of the C–OH groups of serine, threonine tyrosine in proteins, CH2 wagging vibration of the acyl chains, CH in-plane bending of the phenyl ring, as well as in-plane C–O stretching vibrations combined with the ring stretch of phenyl [48,50,51,52,53]. Intensity decrease from BOS to ALSEBOS was also noticed for several peaks centered at 1315, 1368 and 1424 cm−1 attributable to skeletal vibrations of the syringyl and condensed guaiacyl ring, symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of CAr–O–C and C–O in phenols, symmetric bending vibrations of C–H in CH3 groups and in-plane bending vibrations of O–H in phenols, all present in lignin molecules [50,51]. Finally, a significant decrease in peak intensity centered at 1602 cm−1 could be noticed between SEBOS and ALSEBOS, attributable to the C–C stretching skeletal vibrations and C=O stretching of the aromatic ring present in lignin molecules [50,51]. Besides the fact that FTIR-ATR spectrum changes (Figure 2) were well in accordance with observed changes in the chemical composition (Table 1) during BOS transformation, it also indicated changes in the composition of crude fibers obtained by alkaline liquefaction using 2–10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide. Based on the significant decrease in intensity of peaks attributable to the structural features of lignin including wide peak in region from 1170 to 1310 cm−1, and peaks centered at 1315, 1368, and 1602 cm−1 it can be assumed that the majority of BOS present lignin’s were removed from crude fibers by alkaline liquefaction with 10% NaOH solution, leaving the cellulose enriched crude fibers. It is well established that an increased percentage of NaOH in the solution for alkaline liquefaction of lignocellulosic material leads to its greater delignification [54].

Transformation of BOS into a cellulose-derived enzyme immobilization carrier (ALSEBOS) was also monitored by visual color changes in solid residues (Figure 3). The reddish-brown color of BOS has been changed to a brownish color of SEBOS upon application of ScSeqSubE. Following the alkaline liquefaction, the brownish color of SEBOS was found to fade out with the increased percentage of NaOH present in aqueous solution, with the most significant color change at an optimal NaOH percentage of 10%, where cellulose-derived enzyme carrier (ALSEBOS 10) had a light brown color. Observed color changes in solid residues could be attributed to the extraction of color-forming molecules of brown onion skin, including flavonoids and anthocyanins [55,56,57].

Determination of other physical characteristics of solid residues obtained during BOS to ALSEBOS transformation was oriented toward the most desirable enzyme immobilization carrier properties, and was restricted to the analysis of BOS, SEBOS, and ALSEBOS prepared at optimal NaOH percentage (10% aqueous solution). Among a numerous characteristic of carriers used for enzyme immobilization, well reviewed by Zdarta et al. [58], Mohamad et al. [59], Rodríguez-Restrepo and Orrego [60], Khan [61] and Xie et al. [62], the most prominent ones were selected and determined within the current work including changes in surface morphology, average particle size diameter, specific surface area, total pore volume and pore diameter.

It is well established that lignocellulosic fibers of various plant materials, including brown onion skin, have a complex structure consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. The core of such fibers is made of cellulose molecules aligned in parallel via hydrogen bonds to form rod-like cellulose microfibers, followed by intertwining of cellulose microfibers to a cellulose macrofibers via the same bonds. Intertwining of cellulose microfibers results in gaps, which are filled with hemicellulose and lignin. In the structural hierarchy related to the formation of lignocellulosic fibers, hemicellulose plays a key component acting as a flexible matrix/network which surrounds cellulose macrofibres and binds to them via hydrogen bonds and Van der Walls forces, while lignin molecules act as a glue which keeps cellulose-hemicellulose complex structure more strengthen/tighten via covalent linkages (ether and ester bonds) with hemicellulose [63,64,65,66].

Surface morphology changes from BOS to ALSEBOS, determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, are shown in Figure 4. Prior to ScSeqSubE, BOS showed a compact, intact, dense, and non-porous layered structure with individual lines and furrows, attributable to the presence of extractable compounds layered on the surface and within the BOS lignocellulosic fiber structure [8,63]. Following ScSeqSubE obtained SEBOS was found to possess a more irregular structure containing microcracks and voids attributable to the extraction of low molecular weight substances and partial swelling of fibers caused by loosening and rearrangement of hydrogen bonds between cellulose microfibers and hemicellulose-lignin matrix, probably caused by partial rupture of hemicellulose three-dimensional network [8,67]. Alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS by 10% NaOH led to drastic morphological changes in ALSEBOS, which possessed an irregular and more open rough structure with multiple depressions/pores visible, attributable to the significant hemicellulose-lignin matrix degradation/hydrolysis [8,68].

For an effective enzyme carrier, a large surface area achieved by small particles or larger particles of highly porous materials, allowing unhindered diffusion of the substrate to the immobilized enzyme, is of the utmost importance [59,69]. While nanosized particles (10–300 nm) offer greater surface area and high enzyme loading, the use of microscale particles (1–1000 µm) offers greater mechanical and thermal stability and ease in recovery, handling, and reuse of enzyme carriers, beneficial for industrial applications [70,71,72,73]. Since the main task of current research was the production of cellulose-based immobilization carrier intended for industrial application, it was expected that the average particle size of the obtained BOS-derived carrier would lie within the range of microscale particles from 1 to 1000 µm.

Initially prepared BOS (milling, washing, drying, milling; Figure 1) for the purpose of ScSeqSubE had a volume weighted mean diameter of 364 µm (Table 2, Figure S2). Following the subcritical extraction, SEBOS obtained possessed a slightly increased volume weighted mean diameter of 377 µm (Table 2, Figure S2), attributable to the slight swelling of fibers and subsequently changed surface morphology (Figure 4b). Following the alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS, the volume weighted mean diameter of ALSEBOS was reduced to 247 µm (Table 2, Figure S2), probably caused by hemicellulose-lignin matrix degradation/hydrolysis. Regardless of the fact that the BOS to ALSEBOS transformation led to average particle size reduction, BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier (ALSEBOS) possessed an average particle size well within the expected range of carriers intended for use in industrial applications.

BOS to ALSEBOS transformation also led to the changes in specific surface area, total pore volume, and pore diameter (Table 2) derived from the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (Figures S3–S5). Specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, pore sizes using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) test method, while total pore volume was read from the amount of nitrogen adsorbed at the relative pressure (p/p0) of 0.99. Initially prepared BOS had a specific surface area of 4.038 m2/g, total pore volume of 8.441 × 10−3 cm3/g and average pore diameter of 4.876 nm, which was slightly higher than the data reported for brown onion peel by Lizcano-Delgado et al. [11]. Semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of BOS led to decreased specific surface area, total pore volume, and pore diameter of SEBOS, probably caused by the slight swelling of fibers. Following the alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS, obtained cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier (ALSEBOS) had an increased specific surface area of 3.821 m2/g, total pore volume of 7.193 × 10−3 cm3/g, and average pore diameter of 5.573 nm. This was well in line with the observed ALSEBOS surface morphology of open rough structure with multiple depressions/pores visible (Figure 4c). Based on the appearance of the isotherm (Figure S5) and the obtained data on the pore size (Table 2), it can be concluded that BOS-derived cellulose-based carrier (ALSEBOS) belongs to the mesoporous supports, which are characterized by pore size between 2 and 50 nm [74]. Comparison of BOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier physical properties with other mesoporous supports derived from lignocellulosic materials used for lipase immobilization shows its great potential to be used for immobilization. Spent coffee ground-derived immobilization carrier prepared by a similar transformation scheme as ALSEBOS had a much higher specific surface area of 7.12 m2/g, somewhat higher total pore volume of 7.71 × 10−3 cm3/g, but lower average pore diameter of 3.80 nm [30]. On the other hand, defatted SCG used from lipase immobilization had quite a lower value of specific surface area of 0.42 m2/g, total pore volume of 1.22 × 10−4 cm3/g, and average pore diameter of 1.17 nm [75]. Lower values of specific surface area of 1.42 m2/g and total pore volume of 2.321 × 10−3 cm3/g were also reported for defatted rice husk as lipase immobilization carrier, but with somewhat greater average pore diameter of 6.54 nm than ALSEBOS [75].

Table 3 shows the cumulative mass yield of solid residues produced during the transformation of brown onion skin to a cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier. Around 30% of the mass of the originally supplied BOS has been lost during the initial preparation of the BOS. Following ScSeqSubE mass yield of SEBOS was reduced to ~56%. With the completion of BOS transformation into cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier (ALSEBOS) using alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS, 16.62 ± 1.55 g of ALSEBOS as a potential enzyme immobilization carrier was produced from 100 g of originally supplied BOS.

Based on all of the above mentioned it can be concluded that proposed BOS transformation process (Figure 1) seems quite applicable for the production of significant amount of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier (Table 3) of desirable characteristic including chemical and thermal stability and insolubility under biocatalytic reaction condition (Table S1), developed surface morphology (Figure 4c), and adequate particle size, specific surface area, total pore volume and pore diameter (Table 2). However, to approach a “zero-waste” model of circular economy, it was necessary to examine the chemical composition of the extracts obtained during BOS transformation to find their “niche” in the potential production of additional value-added products.

3.3. Physical-Chemical Characterization of Extracts Obtained During Brown Onion Skin Transformation

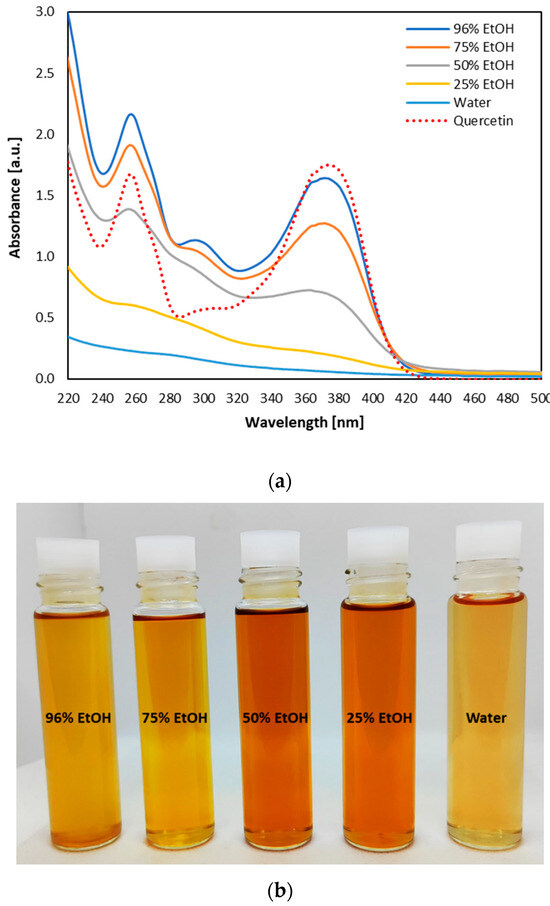

Semi-continuous sequential extraction of brown onion skin by consecutive use of five solvents of increasing polarity (96, 75, 50, and 25% EtOH and water) resulted in yellow to orange-colored extracts (Figure 5b), initially screened on the origin of color-forming molecules by UV-Vis spectra recordings (Figure 5a). Three distinctive peaks positioned at 260, 296, and 370 nm could be observed in the spectrum of ethanolic extracts (96, 75, and 50%), but diminished in the spectra of 25% ethanolic extract and water extract. A similar peak position was found for the spectra of quercetin ethanolic solution (Figure 5a), where the peak positioned at 296 nm was less visible. Based on the fact that peak positioned around 260 nm could be assigned to π → π* electron transition of benzoyl group, while those at 370 nm to electron transition of cinnamoyl group of quercetin and other flavanols [76,77] it can be assumed that quercetin and its glucosides, as well as other flavanols could be the major coloring pigments present in 96, 75, and 50% ethanolic extracts. This was additionally confirmed by quercetin and quercetin-4-glucoside content in the extracts (Table 4).

Figure 5.

UV/Vis spectra (a) and color of the extracts (b) obtained by semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of brown onion skin by 96%, 75%, 50%, 25% ethanol (EtOH) and water. UV/Vis spectra obtained from extracts diluted ten-fold are compared with UV/Vis spectra of an ethanolic solution of quercetin (γ = 0.025 mg/mL).

Table 4.

Chemical composition of the extracts obtained by semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of brown onion skin with 96%, 75%, 50%, 25% ethanol (EtOH) and water. Results are presented as average values ± standard deviations of at least three independent determinations.

Obtained extracts were analyzed on dry matter content and chemical composition (Table 4). In total, semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of BOS resulted with ~169 mg/g (~16.9%) of extracted matter, containing around 37 mg/g of proteins, 40 mg/g of total sugars, 17.5 mg/g of uronic acids, 28 mg/g of total polyphenol and 36 mg/g of total flavonoids (Table 4). Extracts were found to contain 13 mg/g of arabinose, around 9 mg/g glucose, 12 mg/g rhamnose, and 9 mg/g xylose in total, and around 10 mg/g of quercetin, 2 mg/g of quercetin-4-glucoside, and 11 mg/g of total flavanols (Table 4). On the other hand, there was no detectable amount of quercetin-3-glucoside and quercetin-3,4-glucoside. Obtained data on the total amount of extractives and examined compounds were somewhat different from reports dealing with subcritical water extraction (SubWE) of brown onion skin. A higher amount of extracted matter (20.9%) was reported by Benito-Román and coworkers [13] at a SubWE temperature of 125 °C. The content of extracted proteins in current research was higher than that reported by Ko et al. [10] (1.14%) and Trigueros et al. [22] (22.8 mg/g). On the contrary, total sugar content was much lower in comparison to the report of Ko et al. [10] (13.24%) and Trigueros et al. [22] (207 mg/g), but higher in comparison to Salak et al. [21] (17 mg/g). Total phenolic content was found to be much lower than that reported by Benito-Román et al. [15] (45 mg/g), while total flavonoid content was higher in comparison to Benito-Román et al. [15] (23 mg/g) and Triqueros et al. [22] (26 mg/g). Amount of extracted arabinose, glucose, rhamnose, and xylose in current research was higher than those reported by Benito-Román et al. [13] at SubWE temperature of 125 °C, while uronic acid content was 3 to 4-fold lower in comparison to Benito-Román and coworkers [13,14]. Great variability in the content of quercetin and its glucosides present in SubWE extracts of brown onion skin can be found in available literature. Quercetin content was reported to range from 2.3 to 25 mg/g, quercetin-3-glucoside from 0.1 to 0.27 mg/g, quercetin-4-glucoside from 3.15 to 7.5 mg/g, while quercetin-3,4-glucoside from 0.38 to 0.84 mg/g [10,15,19,21,22]. Total content of quercetin and quercetin-4-glucoside found in current research (Table 4) is well within the range of reported values.

Application of sequential subcritical extraction was found partially successful in the fractionation of molecules. Although none of the obtained extracts had a single class of molecules, some grouping could be observed (Table 4). Extracted proteins, total polyphenols, and total flavonoids were found to be highest in 96% ethanolic extracts, subsequently decreasing in other ethanolic extracts (75, 50, and 25%), with a minor quantity of proteins present in water extracts, apparently devoid of total polyphenols and flavonoids. Similar distribution could be observed for quercetin, quercetin-4-glucoside, and total flavanols, whose minor presence in water extract has been detected. On the other hand, the extracted amount of total sugars and uronic acids was found to increase with increasing solvent polarity. The highest content of total sugars was found in the 25% ethanolic extract, while in the case of uronic acid, in water extracts. Similar distribution between extracts could be observed for arabinose, glucose, rhamnose, and xylose (Table 4). Based on the distribution of examined compounds between extracts, the potential use of the extracts obtained could be proposed. Since more than 90% of total quercetin and flavanols were found concentrated in 96 and 75% ethanolic extracts, there is a possibility to pool these two extracts and use them for the production of quercetin, as well as for some valuable hydrophobic BOS proteins. On the other hand, 50 and 25% ethanolic and water extracts might be pooled and used for the production of sugars and uronic acids. However, for any further extract exploitation oriented toward the production of value-added products, the implementation of some purification methods will be necessary.

The second step in the production of BOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier was the application of alkaline liquefaction. Based on the lack of leakage of obtained ALSEBOS (Table S1), alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS using a 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide, via two consecutive steps, was chosen as optimal. Chemical composition of the obtained alkaline extracts is shown in Table 5. While 1st alkaline liquefaction extracts contained a significant quantity of proteins, total sugars, uronic acids, and total polyphenols, the second one had only remnants of extractives, fulfilling its intended use, with the complete lack of leakage of obtained ALSEBOS (Table S1). First alkaline liquefaction extracts contained around 19 mg/g of proteins, 58 mg/g of total sugars, 10 mg/g uronic acids, 6.6 mg/g total polyphenols, and 0.5 mg/g of total flavonoids. While the presence of proteins in alkaline extracts was in line with the observed decrease in the protein content between SEBOS and ALSEBOS (Table 1), high amounts of total sugars and polyphenols indicated that some degradation of constitutive structural carbohydrates and SEBOS-color-forming anthocyanins obviously occurred during alkaline treatment. It is well established that alkaline treatment of lignocellulosic biomass leads to partial hydrolysis/depolymerization of lignin and hemicellulose [54,64,68], as well as degradation of anthocyanins [78], followed by subsequent release of phenolic compounds and monosaccharides into the extracts. Therefore, it can be assumed that a high content of total sugars present in alkaline extract might be related to partial degradation of hemicellulose, as well as the release of sugars from glycosylated anthocyanins, while the presence of total polyphenols is related to the release of phenolic compounds from lignins and anthocyanins. Significant change in color between SEBOS and ALSEBOS 10 (Figure 3) indicates that anthocyanin depolymerization/degradation occurred. In addition, the presence of uronic acids in alkaline extracts might be related to the hydrolysis of pectic substances remaining in SEBOS after semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of BOS.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of brown onion skin alkaline liquefaction extracts. Results are presented as average values ± standard deviation of three independent determinations, each performed in triplicate.

Based on the chemical composition of alkaline extracts (Table 5), it is more than obvious that it presents a valuable source of sugars, uronic acids, proteins, and phenolics. However, due to the high concentration of sodium hydroxide (2.5 mol/L), retrieval and more detailed analysis of valuable compounds from alkaline extracts seems quite challenging. One of the most probable possibilities is neutralization of sodium hydroxide present in alkaline extracts by sulfuric acid, where sodium sulfate will be produced. Based on the temperature-dependent solubility of sodium sulfate in water, as well as its reduced solubility in ethanol [79], it seems quite possible that a combination of low temperature and addition of ethanol as antisolvent might be quite useful in sodium sulfate precipitation and subsequent retrieval of compounds present in alkaline extracts.

Based on all the above-mentioned, it seems that the proposed BOS transformation process (Figure 1), besides the production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier of desirable characteristics (Table 2 and Table S1, Figure 4), enables the production of valuable extracts with potential use in the production of value-added compounds. However, based on the extract’s chemical composition (Table 4 and Table 5), distribution of targeted compounds between extracts obtained after sequential subcritical extraction (Table 4) and comparison of their quantities with the most prominent reports [13,14,15], multiple questions regarding currently proposed BOS transformation process (Figure 1) has been raised in order to make it more perfect. According to the our humble opinion, modulation of semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of brown onion skin by increase in solvent volume to solid BOS mass ratio (up to 50 mL per 1 g), extension in the extraction time from 30 up to 60 min for each solvent applied, and slight increase in the extraction temperature from 125 to 145 °C could lead to the increased level of extracted compounds and better fractionation of molecules of interest between extracts, and consequent production of cellulose enriched solid residue (SEBOS). With such an approach, it seems quite possible that subsequent alkaline liquefaction of SEBOS might be performed at a lower sodium hydroxide percentage to achieve a desirable cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier.

3.4. Immobilization of Burkholderia cepacia Lipase onto BOS-Derived Cellulose-Based Immobilization Carrier by Adsorption

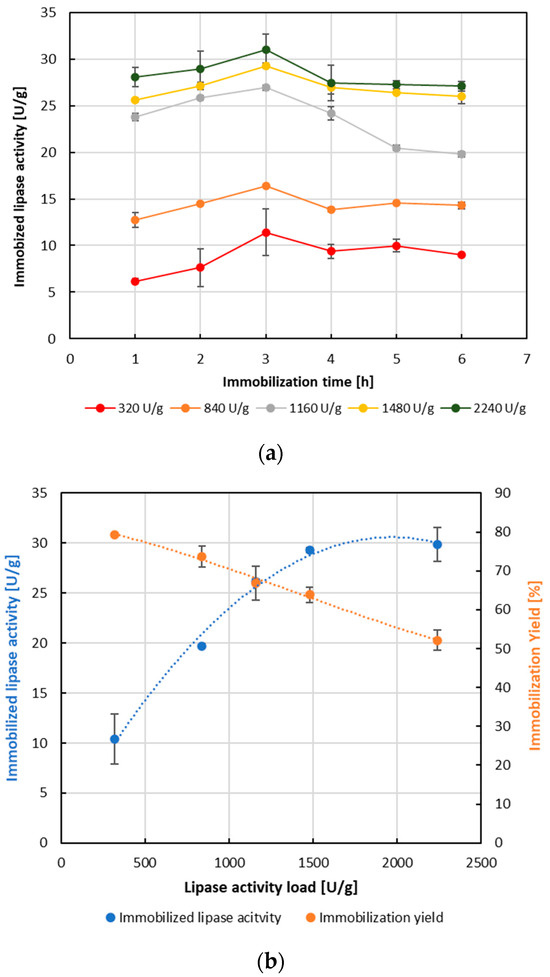

The last step in the evaluation of the proposed process of BOS transformation into a cellulose-based immobilization carrier (Figure 1) was carrier testing on its immobilization suitability for B. cepacia lipase immobilization by adsorption. In this respect, the effect of time and free lipase activity load per 1 g of dry carrier on the immobilization efficiency was monitored (Figure 6). Based on the results obtained (Figure 6a), the highest immobilized lipase activity of 30.99 U per 1 g of wet carrier was achieved at the highest free lipase activity load of 2240 U per 1 g of dry carrier after 3 h of immobilization at room temperature (25 °C). Similar results were found for BCL immobilization by adsorption on spent coffee ground-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier, where maximal immobilized BCL activity of 30.38 U per 1 g of wet carrier was detected at the third hour of immobilization [30]. Figure 6b shows the effect of free lipase activity load on the immobilized lipase activity and immobilization yield at the optimal immobilization time of 3 h. An increase in free BCL activity load per 1 g of dry carrier led to an increase in immobilized BCL activity at lower applied lipase activity loads (320–1160 U/g), and almost identical immobilized BCL activity at higher free lipase activity loads of 1480 and 2240 U/g (Figure 6b). On the contrary, immobilization yield was found to decrease with increased free lipase loading, reaching a yield of 52% at the highest lipase activity load. Similar decrease in the immobilization yield by adsorption was reported by Ostojčić et al. [30] and Bonet-Raquel and coworkers [44]. Regardless of the fact that an increase in free lipase activity load led to reduced immobilization yield (Figure 6b), it should be noted that the observed maximal activity of B. cepacia lipase immobilized by adsorption on BOS-derived cellulose-based immobilization carrier was congruent with the report of Ostojčić et al. [30], where almost identical BCL activity around 30 U per 1 g of spent coffee ground-derived cellulose-based carrier was reported. Higher values of lipase activity per g of dry carrier (135 U/g) was reported for Candida antartica lipase B immobilized by adsorption on coconut fibers [28], while much lower for Acinetobacter baylyi lipase immobilized by adsorption on partially treated lignocellulosic materials including corn cob, rice hulls, banana stalks, W. bifurcate leaves, coconut husks and S. wallichiana stems, ranging from 0.11 to 3.32 U/g of support [27], and for Candida antartica lipase B immobilized on rice husk by adsorption (<5 U/g) [25]. Therefore, it seems that the produced BOS-derived cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier has the potential to be used as a carrier for lipase immobilization. Nevertheless, its potential use in some other techniques of lipase immobilization and subsequent use in biocatalytic processes as reported by Ostojčić et al. [30] remains to be elucidated.

Figure 6.

Immobilization of Burkholderia cepacia lipase by adsorption onto brown onion skin-derived cellulose-based carrier. (a) Effect of time and free lipase activity load on immobilized B. cepacia lipase activity. (b) Immobilized B. cepacia lipase activity and immobilization yield dependence on the activity load of free lipase. Results are presented as average values ± standard deviation of at least three independent determinations each performed in triplicate. Immobilized lipase activity is expressed in units (U) per 1 g of immobilization carrier (on a wet basis). Lipase activity load is expressed in units (U) per 1 g of dry immobilization carrier used for immobilization.

4. Conclusions

This work demonstrated the possibility of brown onion skin transformation into a cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier. Application of semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction of brown onion skin via consecutive use of 5 solvents of increasing polarity (96, 75, 50, and 25% EtOH and water) has been proven as a good starting point for the transformation process, yielding the extracts containing valuable bioactive compounds partially fractionated among them. Alkaline liquefaction using a 10% aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide has been proven as a necessary step in the production of a carrier of desirable physical characteristics. Finally, the BOS-derived cellulose-based carrier was found to possess quite good suitability for Burkholderia cepacia lipase immobilization by adsorption, achieving up to 31 U of lipase activity per g of wet carrier. Altogether, the proposed process of brown onion skin transformation shows potential to be used for simultaneous production of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier and extracts containing value-added compounds, enabling an approach to a “zero-waste” model of circular economy.

Nevertheless, some new perspectives arising from current research are being opened. One is related to the enhanced extractability of brown onion skin bioactive compounds and their better fractionation between extracts obtained by semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction. This might be achieved by modulation of subcritical extraction conditions, including increased solvent volume to BOS mass ratio from 30:1 up to 50:1, prolonged time of extraction from 30 min up to 1 h, as well as a slight increase in extraction temperature from 125 to 145 °C. With such an approach, it seems quite possible that enhanced extractability of bioactive compounds and their better fractionation between extracts will be achieved. The second one is related to the retrieval of valuable compounds from alkaline extracts, which could be achieved by neutralization of sodium hydroxide with sulfuric acid, where the produced sodium sulfate might be separated from valuable bioactive compounds by precipitation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412970/s1: Figure S1: Brown onion skin from the industrial packhouse processing of brown onions; Figure S2: Particle size distribution of brown onion skin (BOS) sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS) and alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin (ALSEBOS); Figure S3: Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of brown onion skin (BOS); Figure S4: Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS); Figure S5: Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of alkaline liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin (ALSEBOS); Table S1: Leakage of brown onion skin solid residues obtained during preparation of cellulose-based enzyme immobilization carrier; Table S2: Effect of alkaline liquefaction of sequentially extracted brown onion skin (SEBOS) by 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10% NaOH on the mass yield of obtained solid residue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.; methodology, I.S., K.A., L.J.B. and I.D.; validation, I.S., L.J.B., I.D. and S.Š.; formal analysis, M.B., M.O., M.S., P.M., B.B.R., L.J.B., J.S. and S.Š.; investigation, I.S., S.B. and S.J.; resources, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., B.B.R., K.A., L.J.B., M.S., J.S. and S.Š.; writing—review and editing, I.S., L.J.B., S.J., I.D. and S.B.; visualization, I.S.; supervision, I.S., S.B., I.D. and S.J.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, grant number IP-2020-02-6878.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the company Enna Fruit d.o.o. (Dugo Selo, Croatia) for the generous supply of brown onion skin from the industrial packhouse processing of brown onions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOS | Brown onion skin |

| SEBOS | Sequentially extracted brown onion skin |

| ALSEBOS | Alkaline-liquefied sequentially extracted brown onion skin |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| BCL | Burkholderia cepacia lipase |

| SubWE | Subcritical water extraction |

| FTIR-ATR | Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance |

| ScSeqSubE | Semi-continuous sequential subcritical extraction |

References

- Jaganmohanrao, L. Valorization of Onion Wastes and By-Products Using Deep Eutectic Solvents as Alternate Green Technology Solvents for Isolation of Bioactive Phytochemicals. Food Res. Int. 2025, 206, 115980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, S.K.; Frimpong, A.J.; Agorku, E.S.; Eke, W.I.; Akaranta, O. Onion (Allium cepa L.) Skin Waste for Industrial Applications: A Sustainable Strategy for Value Addition and Circular Economy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 29, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Punia, S.; Dhumal, S.; Radha; Rais, N.; Chandran, D.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) Peels: A Review on Bioactive Compounds and Biomedical Activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osojnik Črnivec, I.G.; Skrt, M.; Šeremet, D.; Sterniša, M.; Farčnik, D.; Štrumbelj, E.; Poljanšek, A.; Cebin, N.; Pogačnik, L.; Smole Možina, S.; et al. Waste Streams in Onion Production: Bioactive Compounds, Quercetin and Use of Antimicrobial and Antioxidative Properties. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez, V.; Mollá, E.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A.; Aguilera, Y.; López-Andréu, F.J.; Cools, K.; Terry, L.A.; Esteban, R.M. Characterization of Industrial Onion Wastes (Allium cepa L.): Dietary Fibre and Bioactive Compounds. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2011, 66, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, E.; Noble, R.; Mead, A.; Whipps, J.M. Control of Allium White Rot (Sclerotium cepivorum) with Composted Onion Waste. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaime, L.; Mollá, E.; Fernández, A.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A.; López-Andréu, F.J.; Esteban, R.M. Structural Carbohydrate Differences and Potential Source of Dietary Fiber of Onion (Allium cepa L.) Tissues. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, J.P.; Rhim, J.-W. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Microfibers from Agricultural Wastes of Onion and Garlic. J. Nat. Fibers 2018, 15, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, J.; Marra, G.; Olt, V.; Fernández-Fernández, A.M.; Medrano, A. Potential of Onion Byproducts as a Sustainable Source of Dietary Fiber and Antioxidant Compounds for Its Application as a Functional Ingredient. In Proceedings of the International Electronic Conference on Foods, Virtual, 14 October 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, M.-J.; Cheigh, C.-I.; Cho, S.-W.; Chung, M.-S. Subcritical Water Extraction of Flavonol Quercetin from Onion Skin. J. Food Eng. 2011, 102, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizcano-Delgado, Y.Y.; Martínez-Vázquez, O.T.; Cristiani-Urbina, E.; Morales-Barrera, L. Onion Peel: A Promising, Economical, and Eco-Friendly Alternative for the Removal of Divalent Cobalt from Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2024, 12, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, N.A.; Khar, A.; Vikas; Tarafdar, A.; Pareek, S. Physicochemical and Thermal Characteristics of Onion Skin from Fifteen Indian Cultivars for Possible Food Applications. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 7178618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Román, Ó.; Alonso-Riaño, P.; Díaz De Cerio, E.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Semi-Continuous Hydrolysis of Onion Skin Wastes with Subcritical Water: Pectin Recovery and Oligomers Identification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Román, Ó.; Melgosa, R.; Illera, A.E.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Kinetics of Extraction and Degradation of Pectin Derived Compounds from Onion Skin Wastes in Subcritical Water. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Román, Ó.; Blanco, B.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Subcritical Water Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Onion Skin Wastes (Allium cepa Cv. Horcal): Effect of Temperature and Solvent Properties. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.S.; Cho, E.J.; Moon, J.-H.; Bae, H.-J. Onion Skin Waste as a Valorization Resource for the By-Products Quercetin and Biosugar. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.Y.; Lim, S.; Kim, S.O.; Park, Y.-S.; Jang, J.K.; Chung, M.-S.; Park, H.; Shim, K.-S.; Choi, Y.J. Optimization of Various Extraction Methods for Quercetin from Onion Skin Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsampa, P.; Valsamedou, E.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. A Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Process for the Recovery of Antioxidant Polyphenols and Pigments from Onion Solid Wastes Using Box–Behnken Experimental Design and Kinetics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Ko, M.-J.; Chung, M.-S. Extraction of the Flavonol Quercetin from Onion Waste by Combined Treatment with Intense Pulsed Light and Subcritical Water Extraction. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Kheirkhah, H.; Baroutian, S.; Quek, S.Y.; Young, B.R. Subcritical Water Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Waste Onion Skin. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salak, F.; Daneshvar, S.; Abedi, J.; Furukawa, K. Adding Value to Onion (Allium cepa L.) Waste by Subcritical Water Treatment. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 112, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, E.; Benito-Román, Ó.; Oliveira, A.P.; Videira, R.A.; Andrade, P.B.; Sanz, M.T.; Beltrán, S. Onion (Allium cepa L.) Skin Waste Valorization: Unveiling the Phenolic Profile and Biological Potential for the Creation of Bioactive Agents through Subcritical Water Extraction. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velisdeh, Z.J.; Najafpour Darzi, G.; Poureini, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Sedighi, A.; Bappy, M.J.P.; Ebrahimifar, M.; Mills, D.K. Turning Waste into Wealth: Optimization of Microwave/Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Maximum Recovery of Quercetin and Total Flavonoids from Red Onion (Allium cepa L.) Skin Waste. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.Y. Enzyme Immobilization on Cellulose Matrixes. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2016, 31, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corici, L.; Ferrario, V.; Pellis, A.; Ebert, C.; Lotteria, S.; Cantone, S.; Voinovich, D.; Gardossi, L. Large Scale Applications of Immobilized Enzymes Call for Sustainable and Inexpensive Solutions: Rice Husks as Renewable Alternatives to Fossil-Based Organic Resins. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 63256–63270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespugli, M.; Lotteria, S.; Navarini, L.; Lonzarich, V.; Del Terra, L.; Vita, F.; Zweyer, M.; Baldini, G.; Ferrario, V.; Ebert, C.; et al. Rice Husk as an Inexpensive Renewable Immobilization Carrier for Biocatalysts Employed in the Food, Cosmetic and Polymer Sectors. Catalysts 2018, 8, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittrat, P.; Chacho, T.; Pholprayoon, J.; Suttiwarayanon, N.; Charoenpanich, J. Application of Agriculture Waste as a Support for Lipase Immobilization. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brígida, A.I.S.; Pinheiro, Á.D.T.; Ferreira, A.L.O.; Gonçalves, L.R.B. Immobilization of Candida Antarctica Lipase B by Adsorption to Green Coconut Fiber. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008, 146, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasińska, K.; Zieniuk, B.; Jankiewicz, U.; Fabiszewska, A. Bio-Based Materials versus Synthetic Polymers as a Support in Lipase Immobilization: Impact on Versatile Enzyme Activity. Catalysts 2023, 13, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojčić, M.; Brekalo, M.; Stjepanović, M.; Bilić Rajs, B.; Velić, N.; Šarić, S.; Djerdj, I.; Budžaki, S.; Strelec, I. Cellulose Carriers from Spent Coffee Grounds for Lipase Immobilization and Evaluation of Biocatalyst Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Lai, Q.; Jiang, B. Loofah Sponge Activated by Periodate Oxidation as a Carrier for Covalent Immobilization of Lipase. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondul, E.; Dizge, N.; Albayrak, N. Immobilization of Candida Antarctica A and Thermomyces Lanuginosus Lipases on Cotton Terry Cloth Fibrils Using Polyethyleneimine. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 95, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, T.; Kostic, M.; Praskalo, J.; Pejic, B.; Petronijevic, Z.; Skundric, P. Sodium Periodate Oxidized Cotton Yarn as Carrier for Immobilization of Trypsin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, A.M.; Salvagni, L.; Tarola, A.M. Use of Lipase Immobilized on Celluse Support for Cleaning Aged Oil Layers. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 23, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas, V.; Kumar, R.; Pundir, C.S. Covalent Immobilization of Lipase onto Onion Membrane Affixed on Plastic Surface: Kinetic Properties and Application in Milk Fat Hydrolysis. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; D’Souza, S.F. Inner Epidermis of Onion Bulb Scale: As Natural Support for Immobilization of Glucose Oxidase and Its Application in Dissolved Oxygen Based Biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 1792–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yao, J.; Russel, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Ceccanti, B.; Zaray, G.; Choi, M.M.F. Development and Analytical Application of a Glucose Biosensor Based on Glucose Oxidase/O-(2-Hydroxyl)Propyl-3-Trimethylammonium Chitosan Chloride Nanoparticle-Immobilized Onion Inner Epidermis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekalo, M.; Rajs, B.B.; Aladić, K.; Jakobek, L.; Šereš, Z.; Krstović, S.; Jokić, S.; Budžaki, S.; Strelec, I. Multistep Extraction Transformation of Spent Coffee Grounds to the Cellulose-Based Enzyme Immobilization Carrier. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6865:2000; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Crude Fibre Content—Method with Intermediate Filtration. International Standard Organization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Matić, P.; Sabljić, M.; Jakobek, L. Validation of Spectrophotometric Methods for the Determination of Total Polyphenol and Total Flavonoid Content. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, F.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Niu, T.; Lü, X.; Liu, M. Effects of Monosaccharide Composition on Quantitative Analysis of Total Sugar Content by Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 963318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitter, T.; Muir, H.M. A Modified Uronic Acid Carbazole Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1962, 4, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet-Ragel, K.; López-Pou, L.; Tutusaus, G.; Benaiges, M.D.; Valero, F. Rice Husk Ash as a Potential Carrier for the Immobilization of Lipases Applied in the Enzymatic Production of Biodiesel. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2018, 36, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Tao, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, B.; Tan, T. Improving the Activity and Stability of Yarrowia Lipolytica Lipase Lip2 by Immobilization on Polyethyleneimine-Coated Polyurethane Foam. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2013, 91, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustranta, A.; Forssell, P.; Poutanen, K. Applications of Immobilized Lipases to Transesterification and Esterification Reactions in Nonaqueous Systems. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1993, 15, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trbojević Ivić, J.; Veličković, D.; Dimitrijević, A.; Bezbradica, D.; Dragačević, V.; Gavrović Jankulović, M.; Milosavić, N. Design of Biocompatible Immobilized Candida rugosa Lipase with Potential Application in Food Industry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4281–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Ur Rehman, D.I. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. Spectroscopic Tools. Available online: https://www.science-and-fun.de/tools/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kostryukov, S.G.; Matyakubov, H.B.; Masterova, Y.Y.; Kozlov, A.S.; Pryanichnikova, M.K.; Pynenkov, A.A.; Khluchina, N.A. Determination of Lignin, Cellulose, and Hemicellulose in Plant Materials by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 78, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier-Astete, R.; Jimenez-Davalos, J.; Zolla, G. Determination of Hemicellulose, Cellulose, Holocellulose and Lignin Content Using FTIR in Calycophyllum Spruceanum (Benth.) K. Schum. and Guazuma Crinita Lam. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Ross, C.F.; Powers, J.R.; Rasco, B.A. Determination of Quercetins in Onion (Allium cepa) Using Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 6376–6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Al-Qadiri, H.M.; Ross, C.F.; Powers, J.R.; Tang, J.; Rasco, B.A. Determination of Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Onion (Allium cepa) and Shallot (Allium oschaninii) Using Infrared Spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, T.H. A Review on Alkaline Pretreatment Technology for Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samota, M.K.; Sharma, M.; Kaur, K.; Sarita; Yadav, D.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Tak, Y.; Rawat, M.; Thakur, J.; Rani, H. Onion Anthocyanins: Extraction, Stability, Bioavailability, Dietary Effect, and Health Implications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 917617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Pandey, V.K.; Dash, K.K.; Zanwar, S.; Singh, R. Natural Bio-Colorant and Pigments: Sources and Applications in Food Processing. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveoglu, O. A Review on Onion Skin, a Natural Dye Source. J. Text. Color. Polym. Sci. 2022, 19, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarta, J.; Meyer, A.; Jesionowski, T.; Pinelo, M. A General Overview of Support Materials for Enzyme Immobilization: Characteristics, Properties, Practical Utility. Catalysts 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.R.; Marzuki, N.H.C.; Buang, N.A.; Huyop, F.; Wahab, R.A. An Overview of Technologies for Immobilization of Enzymes and Surface Analysis Techniques for Immobilized Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Restrepo, Y.A.; Orrego, C.E. Immobilization of Enzymes and Cells on Lignocellulosic Materials. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R. Immobilized Enzymes: A Comprehensive Review. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Simpson, B. Food Enzymes Immobilization: Novel Carriers, Techniques and Applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]