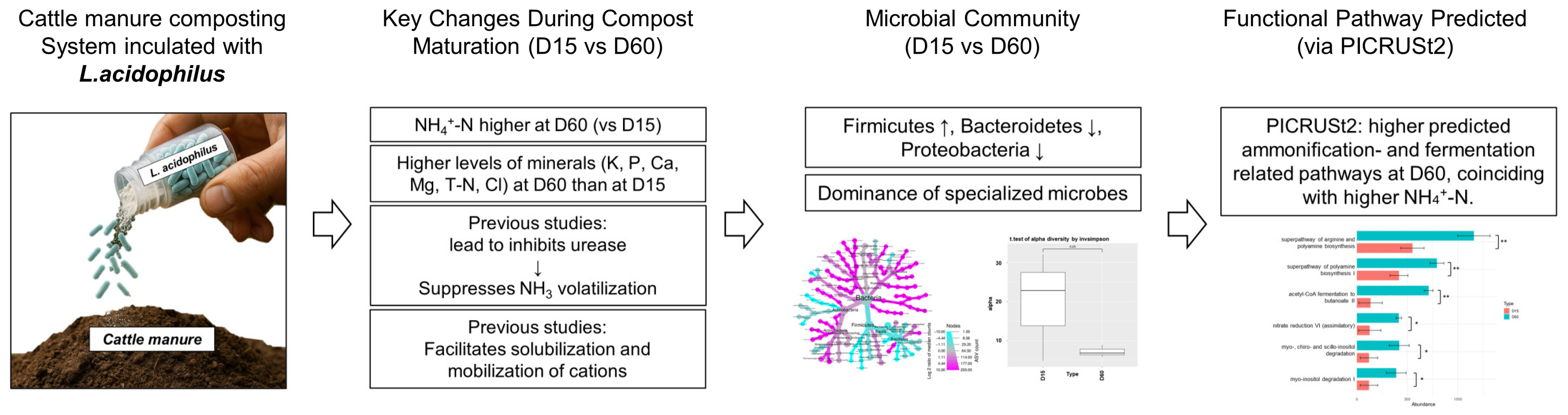

Temporal Nutrient and Microbial Functional Dynamics in a Cattle Manure Composting System Inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Application of L. acidophilus and Manure Properties Analysis

2.2. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Library Preparation

2.3. Read Processing and Taxonomy Assignment

2.4. Microbiome Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

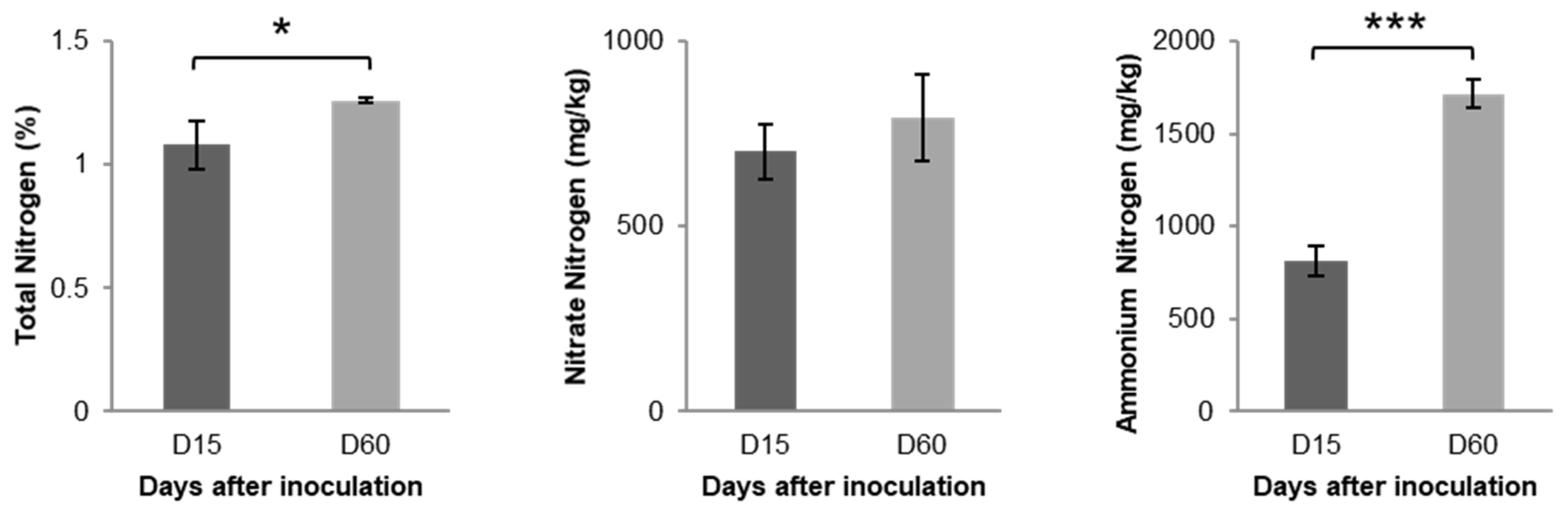

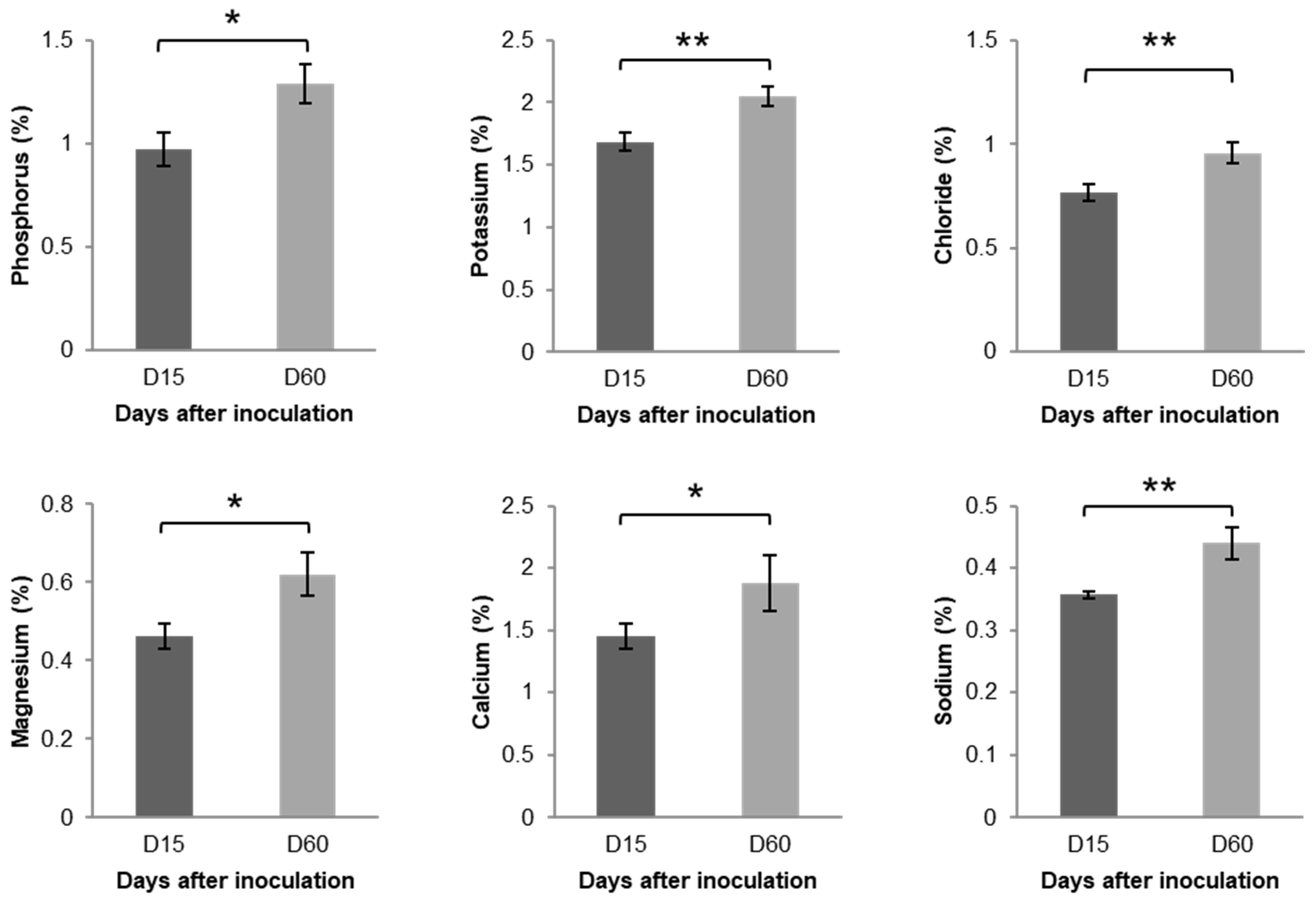

3.1. Changes in Chemical Properties Following L. acidophilus Treatment

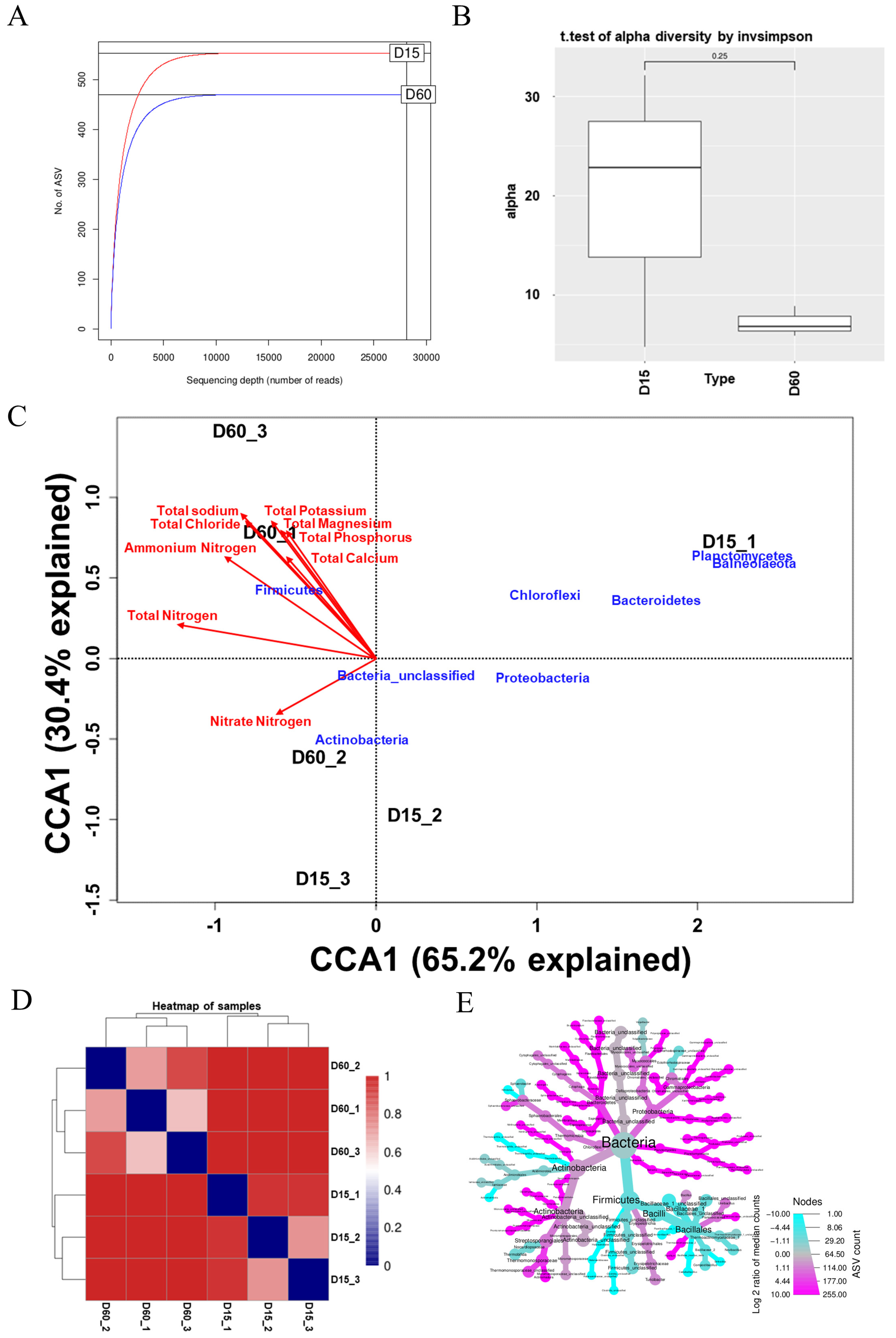

3.2. Alteration of Microbial Community During Composting

3.3. Correlations Between DAB and Manure Properties

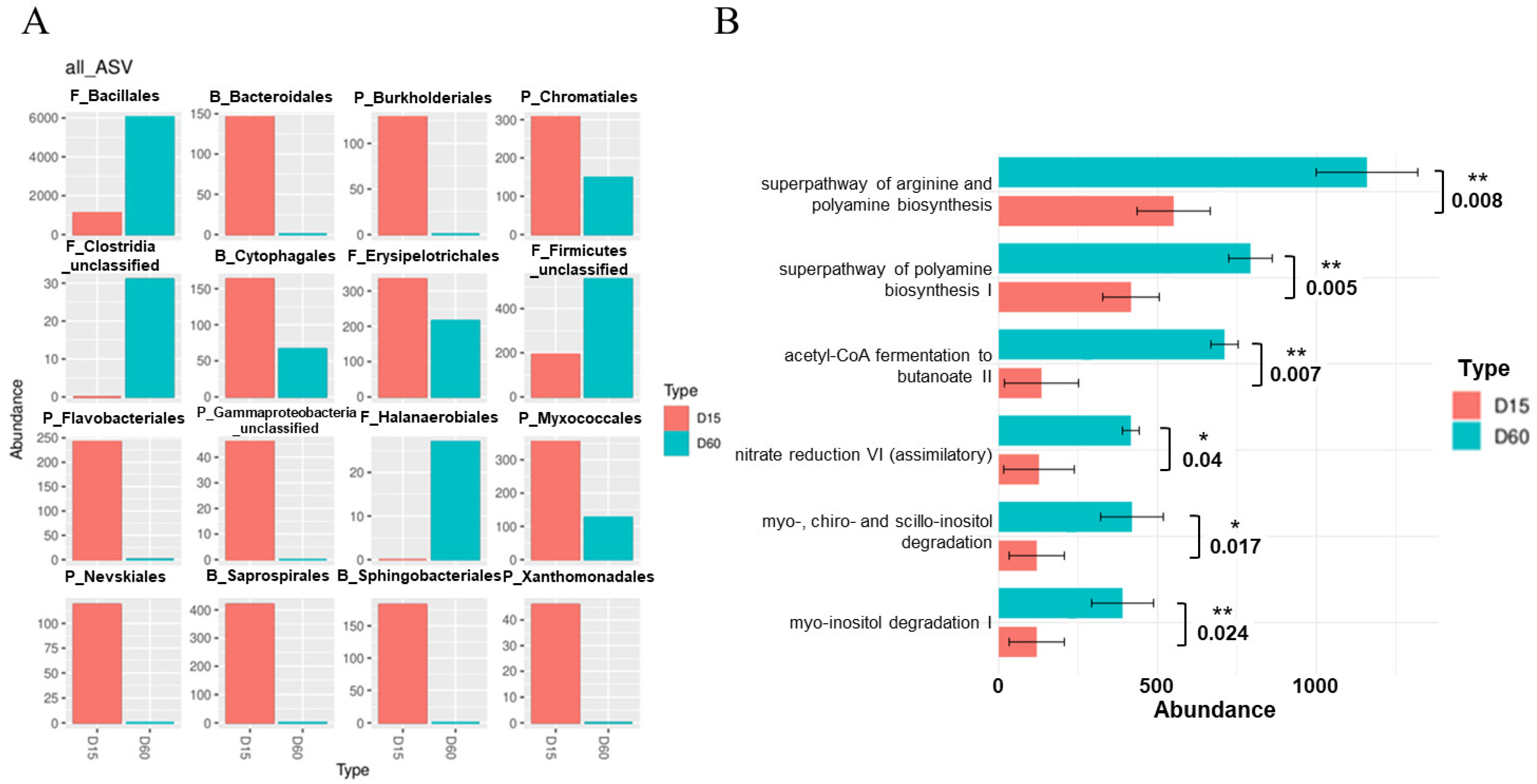

3.4. Variation of DAB and Predicted Functional Pathways During Composting

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium nitrogen |

| K | Potassium |

| P | Phosphorus |

| Ca | Calcium |

| Mg | magnesium |

| T-N | Total nitrogen |

| Cl | Chloride |

| Na | Sodium |

| ASVs | Amplicon sequence variants |

| DAB | Differentially abundant bacteria |

| CCA | Canonical correspondence analysis |

References

- Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Araneda, N.; Valdebenito, E.; Hansen, F.; Nuti, M. Microbial community in the composting process and its positive impact on the soil biota in sustainable agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insam, H.; De Bertoldi, M. Microbiology of the composting process. In Waste Management Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 8, pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckeboer, J.; Mergaert, J.; Vaes, K.; Klammer, S.; De Clercq, D.; Coosemans, J.; Insam, H.; Swings, J. A survey of bacteria and fungi occurring during composting and self-heating processes. Ann. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 349–410. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Yang, W.; Men, M.; Bello, A.; Xu, X.; Xu, B.; Deng, L.; Jiang, X.; Sheng, S.; Wu, X. Microbial community succession and response to environmental variables during cow manure and corn straw composting. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higa, T.; Parr, J.F. Beneficial and Effective Microorganisms for a Sustainable Agriculture and Environment; International Nature Farming Research Center: Atami, Japan, 1994; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffar, N.S.; Jawan, R.; Chong, K.P. The potential of lactic acid bacteria in mediating the control of plant diseases and plant growth stimulation in crop production-A mini review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1047945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, M.N.; Elmaghraby, M.M.; Abdellatif, A.A.; Elmaghraby, I.M. Lactic acid bacteria for safe and sustainable agriculture. In Metabolomics, Proteomics and Gene Editing Approaches in Biofertilizer Industry: Volume II; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, J.; Kim, J.-S.; Choi, K.R.; Eun, H.; Yang, D.; Ko, Y.-J.; Kim, S.-J. Application of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in sustainable agriculture: Advantages and limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Seijas, J.; García-Fraga, B.; da Silva, A.F.; Sieiro, C. Wine lactic acid bacteria with antimicrobial activity as potential biocontrol agents against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Agronomy 2019, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, I.A.; Banday, M.T.; Khan, H.M.; Khan, A.A.; Sheikh, I.U.D. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus (LB) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) fermentation on nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium level of poultry farm waste. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 28, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, R.; Grimm, D.G. Current challenges and best practice protocols for microbiome analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Gu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Understanding host microbiome environment interactions: Insights from Daphnia as a model organism. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliy, O.; Shankar, V. Application of multivariate statistical techniques in microbial ecology. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 1032–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byeon, J.-E.; Lee, J.K.; Park, M.-S.; Jo, N.Y.; Kim, S.-R.; Hong, S.-h.; Lee, B.-O.; Lee, M.-G.; Hwang, S.-G. Influence of hanwoo (Korean native cattle) manure compost application in soil on the growth of maize (Zea mays L.). Korean J. Crop Sci. 2022, 67, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jo, N.-Y.; Shim, S.-Y.; Linh, L.T.Y.; Kim, S.-R.; Lee, M.-G.; Hwang, S.-G. Effects of Hanwoo (Korean cattle) manure as organic fertilizer on plant growth, feed quality, and soil bacterial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1135947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbano, D.M.; Clark, J.L.; Dunham, C.E.; Flemin, R.J. Kjeldahl method for determination of total nitrogen content of milk: Collaborative study. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1990, 73, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, J. Mississippi soil test method and interpretation. In Mississippi Agricultural. Experiment Station Mimeograph; Mississippi State University: Starkville, MS, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, Z.S.; Chamberlain, S.; Grünwald, N.J. Taxa: An R package implementing data standards and methods for taxonomic data. F1000Research 2018, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, Z.S.; Sharpton, T.J.; Grünwald, N.J. Metacoder: An R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Package ‘vegan’. Community Ecol. Package Version 2013, 2, 1–295. [Google Scholar]

- de Mendiburu, F.; de Mendiburu, M.F. Package ‘vegan’. R Package Version 2019, 1, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘ggplot2’. Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. Version 2016, 2, 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kolde, R.; Kolde, M.R. Package ‘pheatmap’. R Package 2015, 1, 790. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. R Package Version 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, E.; Gao, D.; Zheng, G. Effects of lactic acid on modulating the ammonia emissions in co-composts of poultry litter with slaughter sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Qu, H.; Wang, L.; He, M. Highly efficient reduction of ammonia emissions from livestock waste by the synergy of novel manure acidification and inhibition of ureolytic bacteria. Environ. Int. 2023, 172, 107768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Li, J. Greenhouse gas reduction and nitrogen conservation during manure composting by combining biochar with wood vinegar. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares-Morales, J.R.; Cuellar-Nevárez, G.E.; Rivera-Chavira, B.E.; Gutiérrez-Méndez, N.; Pérez-Vega, S.B.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V. Selection of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fresh fruits and vegetables based on their antimicrobial and enzymatic activities. Foods 2020, 9, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Kaur, T.; Kour, D.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, A.N.; Suman, A.; Ahluwalia, A.S.; Saxena, A.K. Minerals solubilizing and mobilizing microbiomes: A sustainable approach for managing minerals’ deficiency in agricultural soil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1245–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Elwany, O.A.; Mohamed, A.M.; Abdelbaky, A.S.; Tammam, M.A.; Hemida, K.A.; Hassan, G.H.; El-Saadony, M.T.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; AbuQamar, S.F.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A. Application of bio-organic amendments improves soil quality and yield of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) plants in saline calcareous soil. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, L.; Luo, J.; Peng, X. Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA) fermenting astragalus polysaccharides (APS) improves calcium absorption and osteoporosis by altering gut microbiota. Foods 2023, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyarko-Mintah, E.; Cowie, A.; Van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.P.; Smillie, R.; Harden, S.; Fornasier, F. Biochar lowers ammonia emission and improves nitrogen retention in poultry litter composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Wen, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, H.; Wang, A.; Liu, S.; Li, Q. Incorporating microbial inoculants to reduce nitrogen loss during sludge composting by suppressing denitrification and promoting ammonia assimilation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Guan, W.; Tai, X.; Qi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; Lin, D. Research Progress on Microbial Nitrogen Conservation Technology and Mechanism of Microorganisms in Aerobic Composting. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Meng, L.; Zheng, Z. Effect of enriched thermotolerant nitrifying bacteria inoculation on reducing nitrogen loss during sewage sludge composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 311, 123461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagnoli, A.; Malibo, S.; Li, T.; Falcioni, S.; Modeo, L.; Petroni, G.; Kongjan, P.; Pecorini, I. Impact of phosphate limitation on PHBV production and microbial community dynamics fed with synthetic fermentation digestate. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Phyla | Chemical Compositions | Mantel’s R | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidetes | Ammonium Nitrogen (mg/kg) | 0.406 | 0.022 |

| Total Nitrogen (%) | 0.830 | 0.001 | |

| Firmicutes | Ammonium Nitrogen (mg/kg) | 0.536 | 0.015 |

| Chloride (%) | 0.554 | 0.011 | |

| Sodium (%) | 0.533 | 0.041 | |

| Proteobacteria | Total Nitrogen (%) | 0.677 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Choi, H.S.; Le, T.Y.L.; Hwang, S.-G. Temporal Nutrient and Microbial Functional Dynamics in a Cattle Manure Composting System Inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412969

Lee J, Choi HS, Le TYL, Hwang S-G. Temporal Nutrient and Microbial Functional Dynamics in a Cattle Manure Composting System Inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412969

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Junkyung, Hyun Sik Choi, Tran Yen Linh Le, and Sun-Goo Hwang. 2025. "Temporal Nutrient and Microbial Functional Dynamics in a Cattle Manure Composting System Inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412969

APA StyleLee, J., Choi, H. S., Le, T. Y. L., & Hwang, S.-G. (2025). Temporal Nutrient and Microbial Functional Dynamics in a Cattle Manure Composting System Inoculated with Lactobacillus acidophilus. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412969