Abstract

Early risk prediction is essential for hospitalized prostate cancer (PCa) patients, who face acute events, such as mortality, ICU transfer, AKI (acute kidney injury), ED30 (unplanned 30-day Emergency Department revisit), and prolonged LOS (length of stay). We developed an MMoE (Multitask Mixture-of-Experts) model that jointly predicts these outcomes from the features of the multimodal EHR (Electronic Health Records) in MIMIC-IV (3956 admissions; 2497 patients). A configuration with six experts delivered consistent gains over strong single-task baselines. On the held-out test set, the MMoE improved rare-event detection (mortality AUPRC (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) of vs. , ) and modestly boosted ED30 discrimination (AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) with leakage-safe ClinicalBERT fusion) while maintaining competitive ICU and AKI performance. Expert-routing diagnostics (top-1 shares, entropy, and task-dead counts) revealed clinically coherent specialization (e.g., renal signals for AKI), supporting interpretability. An efficiency log showed that the model is compact and deployable (∼85 k parameters, MB; s/sample); it replaced five single-task predictors with a single forward pass. Overall, the MMoE offered a practical balance of accuracy, calibrated probabilities, and readable routing for the prognostic layer of digital-twin pipelines in oncology.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is among the most common malignancies in men and “ranks as the most frequently diagnosed cancer in 118 countries” [1,2,3]. Hospital admissions for this type of cancer are frequently complicated due to multimorbidity, treatment toxicity, peri-procedural events, and infection [4,5]. In the first hours of care, clinicians should decide on the monitoring intensity, escalation, and discharge planning under uncertainty across several short-horizon endpoints. Point solutions that predict a single endpoint (e.g., mortality or readmission) can be useful. However, they may present a fragmented signal and yield inconsistent risk scales, in addition to requiring multiple calibrations and maintenance burdens [6].

In parallel, digital twins—data-driven, patient-specific virtual counterparts—are gaining traction as a unifying lens for forecasting and “what-if” reasoning in oncology. A key building block for such twins is a predictive risk layer that supplies coherent, calibrated probabilities for several clinically salient outcomes at once. Therefore, we present a single multitask predictor that can exploit cross-task structure while keeping deployment and governance simple (as summarized in our recent review on AI-driven digital twins for PCa [7]) instead of a stack of one-off models.

This paper presents an MMoE model that jointly estimates five endpoints from routinely available EHR features—namely, in-hospital mortality, ICU transfer, AKI, ED30, and LOS. The design of this model encourages task-aware specialization (via task-specific gates) while retaining shared structure across outcomes, seeking strong discrimination under class imbalance and well-calibrated probabilities with lightweight introspection of how the model partitions clinical signals. On a real-world PCa cohort, we observed improved rare-event detection (e.g., mortality AUPRC ↑) and modest ED30 gains (with leakage-safe text fusion), alongside better calibration on key endpoints and a small runtime footprint.

Our goals may be enumerated as follows: (i) Discrimination under class imbalance: strong ranking performance was reported for the AUROC and AUPRC on rare and common events alike; (ii) Calibrated probabilities: outputs suitable for thresholding and decision support (Brier score and ECE (Expected Calibration Error); (iii) Interpretability: expert-routing diagnostics reveal how the model partitions clinical signals across tasks.

We accompany the model with systematic ablations over the number of experts and regularization. Additionally, we report efficiency metrics (i.e., parameters, size, and latency) to emphasize deployability.

Contributions

The main contributions of the work described in this paper may be enumerated as follows:

- A compact MMoE that replaces five single-task predictors with a single, calibrated risk layer for mortality, ICU transfer, AKI, ED30, and LOS;

- Evidence that expert routing produces clinically coherent specialization (e.g., renal vs. decompensation pathways) without sacrificing cross-task sharing;

- Systematic ablations that show how a six-expert configuration could provide a strong performance–complexity trade-off, with improved rare-event discrimination and better probability calibration on key endpoints.

- Practicality: a small footprint and single-pass inference that simplify calibration, monitoring, and governance compared to baseline stacks.

Accordingly, we position our framework as a practical “predictive risk layer” for digital-twin workflows in oncology.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work. Section 3 presents the detailed methodology, including data availability, cohort construction, outcome definitions, model architecture, and the results. Section 4 includes insights and findings from the reported results and discusses their significance in the development of digital twins. Section 5 concludes with a summary and discussion of future research directions.

2. Related Work

This work sits at the intersection of the following research directions: (i) Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models for task-aware sharing, (ii) Multitask Learning (MTL) for clinical prediction under class imbalance, and (iii) multimodal fusion of structured EHR with clinical notes within the broader lens of oncology digital twins (DTs). The workflow of a DT includes a multi-endpoint, calibrated predictive risk layer that underpins monitoring, threshold-based alerts, and downstream “what-if’’ simulation; our MMoE targets this role by replacing a stack of single-task models with a single interpretable backbone [7,8]. We briefly review each research direction, then position our contributions and DT compatibility.

2.1. Mixture of Experts and Task-Aware Sharing

MoE decomposes complex prediction problems into modular experts with a learned gate that routes inputs to specialists [9]. MMoE extends this principle to multitask settings by giving each task its own gate while sharing experts across tasks and allowing task-aware specialization without abandoning cross-task sharing [10]. This is attractive in clinical EHR, where heterogeneous signals (e.g., labs, vitals, medications, and notes) and outcomes (rare vs. common) benefit from both the shared structure and task-specific views.

Recent medical ML has used MoE to improve efficiency and to maintain interpretability at scale. As an example, lightweight domain-specific experts for medical vision–language tasks can match larger monolithic models while activating only a subset of parameters at inference, enabling faster and more frugal deployment [11]. In structured clinical applications, MoE has also been used to jointly stratify risk and surface phenotypes, revealing subgroups with distinct treatment responses that are obscured by single-stream models [12]. Sparse MoE variants (e.g., switch Transformers) further simplify routing to top-1 experts, improving throughput and scalability [13], and large, modern MoE models(e.g., Mixtral [14]) demonstrate that sparse activation can outperform dense models at lower computational cost, a practical benefit for on-premise clinical settings where privacy and latency matter.

- Gap:

Prior MoE work rarely targeted PCa EHR prediction, and few studies have reported routing diagnostics (entropy, top-1 usage, and task-dead experts) alongside calibration and efficiency–all essential for clinical deployment. Our study addresses these gaps with a compact MMoE model, explicit routing summaries, and deployment-centric metrics.

2.2. Multitask Learning for Clinical Prediction

MTL exploits related endpoints to improve generalization through shared inductive bias [10]. In critical-care benchmarks (e.g., MIMIC-III), joint training across mortality, decompensation, LOS, and phenotyping showed benefits but also negative transfer when unrelated tasks compete for capacity [15]. A follow-on work proposed routing/partitioning mechanisms (e.g., sequential subnetwork routing) to manage task interactions and to improve label efficiency [16]. Other studies have jointly modeled temporally linked targets (e.g., AKI→CRRT; short–mid–long-horizon mortality), capturing the progression structure missed by single-task models [17,18].

Beyond shared-bottom LSTM models, recent deep learning approaches have explored more expressive architectures for clinical MTL. Rajkomar et al. [19] trained deep models on multi-hospital EHR data to jointly predict mortality, readmission, and LOS from structured and unstructured inputs. Transformer-based approaches have also gained traction. For instance, TransformEHR [20] introduced a generative encoder–decoder architecture pretrained on disease outcome prediction, achieving state-of-the-art results on MIMIC-IV; MulT-EHR [21] combined heterogeneous graph learning with causal denoising for multi-task prediction of mortality, readmission, LOS, and drug recommendation. Multimodal fusion methods integrate clinical notes, vital signs, and imaging within unified Transformer frameworks [22], while attention-based models like RETAIN [23] prioritize interpretability through reverse-time attention mechanisms.

- Gap:

Many clinical MTL papers optimize discrimination but under-report probability calibration and do not provide transparent routing analyses. Additionally, most approaches target general ICU populations with high-frequency time-series data, leaving disease-specific cohorts and admission-level prediction underexplored. We adopted MMoE to mitigate negative transfer via task-specific gates plus entropy regularization. Unlike monolithic encoders, the MMoE’s gating mechanism makes cross-task sharing explicit and interpretable, allowing for the examination of expert specialization along clinically meaningful dimensions. We operate on admission-level tabular features aligned with clinical decision points and explicitly evaluate calibration (Brier/ECE), routing metrics, and deployment constraints. For ED30, we further incorporate leakage-safe text fusion with explicit temporal safeguards, addressing a gap in a prior multimodal MTL framework that typically lacks task-specific leakage analysis. Because the above studies used different datasets (MIMIC-III, MIMIC-IV general ICU, or multi-hospital EHR), inclusion criteria, and outcome definitions, a direct numerical comparison is not meaningful; instead, we position this literature as conceptual context for our architectural choices and provide strong single-task baselines based on our prostate cancer cohort.

2.3. Multimodal Fusion and Notes-Aware ED30

Integrating EHR structure with text generally improves downstream prediction. This has been demonstrated by recent (hypergraph and Transformer-based) frameworks that demonstrate gains over unimodal baselines across tasks and datasets (see [24,25,26,27]). In practice, leakage control dictates which endpoints can safely use notes; readmission-like targets (ED30) often benefit most from late-stage documentation, whereas mortality or ICU predictions risk post hoc (fit on validation, applied to test; AUROC/AUPRC unchanged) leakage if discharge-time text is included.

- Gap:

Prior fusion studies emphasized average gains but often lacked endpoint-specific, leakage-aware integration. Therefore, we restrict text to ED30 (leakage-safe) and achieve a modest but consistent improvement with a lightweight ClinicalBERT blend, keeping other endpoints purely tabular so that inputs remain fully traceable (explicit time stamps and deterministic transforms) and easy to audit for leakage and compliance.

2.4. Digital Twins in Oncology

Digital twins (DTs) are data-driven virtual counterparts of physical entities that evolve with the physical entity over time. In healthcare, the term is often used across a spectrum ranging from digital models (manually refreshed) to digital shadows (one-way, automatically refreshed) and true digital twins (bidirectional synchronization) [8,28]. Oncology DTs have appeared in several forms, including physics/mechanistic models of tumor growth and therapy response [29,30,31,32,33], imaging-driven twins for treatment planning [34,35,36,37], and data-centric twins that integrate multi-source clinical data for forecasting [7,38,39].

Within this spectrum, a foundational building block is a predictive risk layer that supplies coherent, calibrated probabilities for multiple short-horizon endpoints relevant to acute care. Most existing oncology DT efforts emphasize imaging or mechanistic components and were evaluated on small cohorts, whereas comparatively fewer leverage routine EHR data for multi-endpoint prognostics in specific cancer populations (e.g., prostate cancer inpatients). Our work addresses this gap by delivering a compact multitask risk layer based on an MMoE model, producing five calibrated risks in a single pass with interpretable expert routing. This predictive layer is DT-compatible: it can underpin monitoring, threshold-based alerts, and parallel “what-if’’ modules in a broader DT pipeline. Additionally, it naturally complements prescriptive components (e.g., causal effect estimation/policy learning) without adding deployment complexity.

Recent works outside the clinical domain have also explored digital-twin architectures for real-time system monitoring and predictive maintenance, illustrating the broader interest in combining mechanistic models with data-driven components. Examples include digital-twin frameworks for remaining useful life estimation in mechanical systems [40] and for efficiency optimization in photovoltaic installations [41]. Although these applications differ from the inpatient setting considered here, they reflect a growing trend toward compact, deployable models that support real-time decision-making.

2.5. Positioning and Novelty

We do not claim to build a full bidirectional DT in this work. Rather, we contribute the prognostic core—a multitask, calibrated, and interpretable risk layer designed to be embedded in DT workflows for oncology. In contrast to prior DT works, which are often imaging- or physics-forward, we demonstrate that routine EHR signals can support a single efficient model.

Relative to prior work, our contributions may be enumerated as follows:

- MMoE for PCa admissions: A compact, MMoE model jointly predicts five endpoints (namely, mortality, ICU, AKI, ED30, and LOS) from routine EHR data, replacing a stack of one-off models with a single calibrated risk layer.

- Interpretable routing with calibration: We report gate entropy, top-1 shares, and task-dead experts alongside AUROC/AUPRC and Brier/ECE by linking specialization patterns.

- Principled configuration selection: Systematic ablations over a number of experts, load-balance regularization, and task weights identify six experts as the knee of the performance–complexity curve (by considering discrimination under imbalance, calibration, and LOS fit).

- Leakage-safe ED30 fusion: We show targeted text fusion only where temporally appropriate (ED30), thereby confirming modest gains while preserving auditability for other endpoints.

- Deployability: We document parameter count, model size, and latency, demonstrating that a single-pass MMoE model reduces operational burden compared to five per task baselines.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Availability

MIMIC-IV [42,43] is available to credentialed researchers through PhysioNet under a data use agreement. Access to the database for this study was granted following completion of the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) “Data or Specimens Only Research” course and acceptance of the PhysioNet Credentialed Health Data Use Agreement (version 1.5.0) [44]. All the analyses were conducted using the de-identified MIMIC-IV dataset in full compliance with PhysioNet’s data use requirements, including the obligations to (i) avoid re-identification of any individual or institution, (ii) prevent disclosure of protected health information, (iii) maintain secure handling of the restricted data, and (iv) report any potentially identifying information to PHI-report@physionet.org. Access was requested solely for lawful scientific research, and results produced from the restricted data are shared alongside the anonymized reproducibility code. Because the redistribution of MIMIC-IV is not permitted, patient-level data used in this study cannot be shared. However, all reproducibility artifacts, including the SQL cohort-construction scripts, BigQuery feature-engineering pipeline, PyTorch training code, and the evaluation scripts have been released in a public GitHub repository. The repository includes a detailed README with step-by-step instructions for environment setup and pipeline execution. Researchers with their own credentialed PhysioNet access can use these scripts to fully regenerate the analytic dataset and replicate all the results. No patient-level data are included in the repository.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Cohort and Problem Setting

All the modeling was performed on a prostate cancer (PCa) inpatient cohort derived from MIMIC-IV v3.1. Admissions with ICD-9 185 [45] or ICD-10 C61 [46] were included, yielding 3956 admissions from 2497 unique patients. The objective is to estimate acute risks during and shortly after the index hospitalization: in-hospital mortality, ICU transfer, AKI, LOS, and 30-day ED revisit (ED30). Splits are at the patient level to avoid identity leakage (64% train, 6% validation, and 30% test), and the temporal order is preserved to approximate prospective deployment. We used routinely recorded EHR signals; text is incorporated only for ED30 in a leakage-safe manner.

3.2.2. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on the Google Cloud Platform using a Vertex AI Workbench instance. The computational environment consisted of an n2-standard-16 machine type equipped with 16 vCPUs (8 physical cores) and 64 GB of RAM, running on Intel Cascade Lake processors. The instance ran Debian GNU/Linux 11 (Bullseye) with a 150 GB boot disk and 100 GB data workspace using balanced persistent disk storage. All model training and the evaluation were performed using CPU-based computation without GPU acceleration. The framework was implemented in Python using PyTorch 2.8.0. Training of the MMoE model for 60 epochs required approximately 10 h.

3.2.3. Feature Engineering and Missing Data Handling

We used a straightforward, rule-based approach to handle missing values so that no patients were excluded and all features could flow cleanly through the downstream preprocessing and modeling steps. At the database level, we did not impute clinical values; instead, count-based summaries (e.g., number of pharmacy orders or transfers) were coalesced to 0 and all time-series streams were coalesced to empty arrays when no events were present. All other fields were left as NULL.

After loading the table into pandas, we normalized nullable “dtypes” and converted all pandas <NA> values to standard NaN. Sequence columns (labs, vitals, chart events, pharmacy, prescriptions, and eMAR) were parsed into lists of event dictionaries, with missing or malformed entries mapped to empty lists. Numerical predictors (e.g., counts, durations, and sequence-derived statistics) were converted to float64 and median-imputed using only the training split. Categorical variables (admission type, insurance, race, marital status, primary service, top medication indicators, and anchor year group) were cast to object, and missing values were assigned an explicit “missing” level before one-hot encoding. Boolean indicators were coerced to 0/1, with missing values mapped to 0. “Datetime” fields were parsed to datetime64[ns], and missing timestamps were replaced with a neutral epoch value (1970–01–01); these fields were only used to derive relative time features and were not modeled directly.

Finally, the scikit-learn preprocessing pipelines applied a second layer of median (numeric) or most frequent (categorical) imputation before scaling and encoding, thereby ensuring that no patients were removed due to missingness.

3.2.4. Outcomes

We predicted five endpoints representing key inpatient decision points:

- In-hospital mortality: death during the index admission;

- ICU transfer: any ICU admission during hospitalization;

- AKI: KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes)-inspired SCr-only criteria: mg/dL within any 48 h window or, where (admission-day baseline) [47];

- LOS: total hospital days (continuous);

- ED30: emergency department return within 30 days of discharge.

3.2.5. Features

Structured covariates include demographics, admission metadata, comorbidities/ procedures, pharmacy/prescription summaries, and early-window (first 12 h) temporal aggregations of labs, vitals, and ICU charted events. For ED30 only, we additionally derived text features from discharge/radiology notes (TF–IDF [48], ClinicalBERT [49], BioBERT [50]), restricted to pre-outcome content to prevent label leakage.

3.2.6. Model Architecture for the MMoE

Let be an input and be the task set.

- Experts:

A shared bank of experts (), each comprising a two-layer MLP (Multi-layer Perceptron):

- Task-specific gating:

Each task (t) has a linear gate( ) with soft weight of and . The mixed representation is .

- Heads:

One linear head per task, i.e., ; sigmoid for binary tasks (mortality/ICU/ED30/AKI) and linear for LOS.

3.2.7. Training Objective and Regularization

For binary tasks, we used binary cross-entropy (BCE with logits) (the linear head outputs logits () and probabilities ()); LOS uses MSE:

To discourage expert collapse and encourage mixing, we added the negative entropy term (minimizing it increases entropy):

Class imbalance is handled via pos_weight inside BCE (computed from the training split).

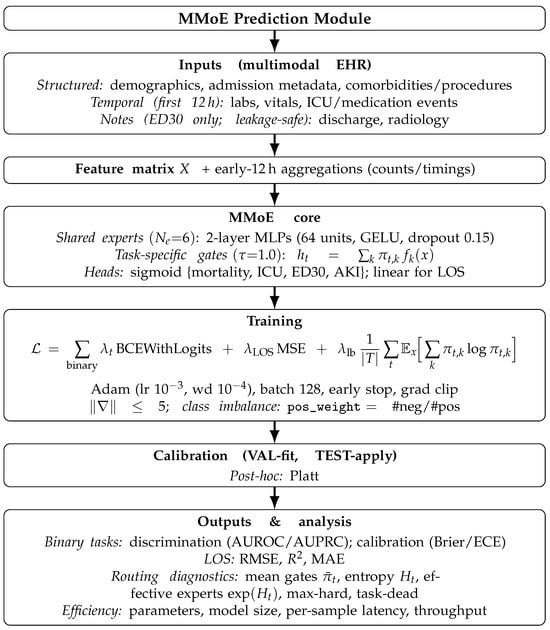

An overview of the end-to-end MMoE prediction module is shown in Figure 1. Let be an input and be the task set.

Figure 1.

End-to-end schematic of the MMoE risk layer.

3.2.8. Hyperparameter Tuning and Final Configuration

- Search space:

, , weights .

- Training setup:

Adam (lr , wd ), batch 128, grad clip , patience 10.

- Early stopping:

At the end of each epoch, we evaluated the validation and kept the checkpoint with the best composite. Let U be the present set of binary tasks (). The validation composite used by the training script is

that is, the mean of the binary-task AUROCs and the non-negative LOS . (Note that AUPRC is not used for early stopping; it is reported later.)

- Final configuration and rationale:

The configuration we report is , , equal task weights based on the composite computed:

where and .

- Mortality gains: higher AUROC/AUPRC than the best classical baseline (AUROC 0.817 vs. 0.799; AUPRC 0.163 vs. 0.091);

- AUPRC across tasks: highest mean AUPRC among the settings we tried; this is consistent with better rare-event detection;

- Calibration: lower ECE on mortality/ICU/AKI at versus , indicating probability quality benefits from entropy load balancing;

- Knee in : moving from improves utility, whereas 8–10 adds complexity without consistent lift, favoring as the performance–complexity elbow;

- Trade-off on LOS: a small decrease vs. some alternatives is acceptable, given the rare-event and calibration gains; a hybrid deployment can retain a tree-based LOS regressor if desired.

3.2.9. Evaluation and Calibration

For the four binary endpoints (mortality, ICU, ED30, and AKI), we report the following:

- Discrimination: how well scores separate positives from negatives—using AUROC and AUPRC;

- Calibration: whether predicted probabilities match observed risks—using the Brier score and ECE (10 bins).

- For LOS (regression), we report the RMSE, , and MAE.

- Probability calibration:

We calibrated predicted probabilities on the validation split and applied the calibrator for testing.

- Routing summaries:

To make the gating behavior readable, we summarized the per task mean gate weights (), the entropy () (and effective experts ()), hard top-1 routing fractions, and the count of task-dead experts (never selected as top-1).

- Robustness probes (no retraining):

We varied the gate temperature (sharper/flatter softmax), enforced top-K gating (), and masked individual experts to assess the sensitivity of discrimination/calibration to routing changes.

- Exploratory saliency:

We computed simple input-gradient saliency to visualize features that mostly influence the score; this is for explanation only; it was not used for model selection.

3.2.10. Baselines

We trained strong single-task baselines per endpoint using the same tabular features as in the MMoE.

- For classification (mortality, ICU, ED30, and AKI), Logistic Regression (L1/L2/ElasticNet), linear/RBF SVM, kNN, Random Forest (100/300 trees), Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, LightGBM, and a two-layer MLP were used.

- For LOS (regression), Ridge, Lasso, ElasticNet, LinearSVR, and RF/GBM regressors were used.

All baselines were tuned on the validation split, calibrated on the validation split, and evaluated on the held-out test split.

3.2.11. ED30 Text Fusion (Leakage-Safe)

For ED30 (30-day emergency department return) only, we augmented structured features with clinical text to test whether the documentation provides a complementary signal. For each admission, we constructed a single text field by concatenating the discharge summary and radiology reports from the index hospitalization. The ED30 label is derived from downstream encounters (whether a separate ED visit occurred within 30 days of discharge); critically, no notes from future ED visits or subsequent admissions were exposed to the model—only the documentation from the index stay was used. We built three text encoders on the training split: TF-IDF with Logistic Regression, ClinicalBERT [49], and BioBERT [50] (pooled [CLS] embeddings → LR). Each encoder outputs a calibrated ED30 probability, which is fused with the tabular MMoE output via two strategies: (i) a validation-tuned convex probability blend and (ii) a logistic meta-model. The method with the higher validation AUROC was evaluated on the held-out test set, with pairwise DeLong tests quantifying the statistical significance of fusion gains.

We intentionally excluded text features for mortality, ICU transfer, AKI, and LOS. These outcomes occurred during the index admission, and notes written after the event could leak label information. Rigorous intra-stay censoring would be required to safely incorporate text for these tasks. For ED30, because all text derives from the index stay and the outcome occurred after discharge, temporal separation was naturally preserved.

3.2.12. Efficiency and Reproducibility

For each baseline and MMoE run, we logged parameter counts, serialized size, per sample inference time, and the throughput. A consolidated table summarizes the efficiency. All experiments used a fixed global seed and deterministic cuDNN settings. A unified driver orchestrated sweeps, checkpointing, logging of metrics, calibration, routing summaries, and probes; outputs were consolidated into CSV/JSON for reproducibility.

3.3. The Results

The proposed MMoE model delivered a single calibrated backbone for five acute endpoints in PCa admissions. Across a held-out test cohort, it improved rare-event detection, sustained competitive performance on common endpoints, and preserved probability quality while replacing a stack of per task models with one compact network.

3.3.1. Ablations and the “Knee”

Systematic sweeps identify a principled operating point (, , ). Moving from 4→6 experts produced clear utility gains, pushing to 8–10added complexity with no reliable lift. Entropy load balancing () reduced ECE on key endpoints, thereby indicating healthier expert usage and better probability quality. This “knee” balanced discrimination, calibration, and size.

3.3.2. Baselines vs. MMoE (EHR Only)

We compared the proposed MMoE model against the strong single-task baselines trained per endpoint using identical EHR inputs and per model calibration (Table 1 and Table 2). The MMoE model (one model for five endpoints) was reported with , , and . Final calibrated test metrics are reported in Table 3.

Table 1.

Best classical baselines per task on TEST. Arrows indicate directionality of improvement: “↑” denotes that higher values are better, and “↓” denotes that lower values are better.

Table 2.

Best classical baseline for LOS on TEST. Arrows indicate directionality of improvement: “↑” denotes that higher values are better, and “↓” denotes that lower values are better.

Table 3.

Final MMoE performance on TEST. , , equal task weights for (mort, icu, ed30, aki, los).

To assess the reliability of the reported performance metrics, we computed the non-parametric bootstrap confidence intervals. For each task, we repeatedly resampled the test set with replacement (1000 bootstrap draws) and recalculated AUROC, AUPRC, or regression metrics on each sample. The 95% confidence interval was obtained by taking the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution. This procedure was applied consistently across the MMoE model and the best classical baseline for each outcome to provide a clearer sense of which performance differences are likely to be meaningful. Table 4 reports this for the metrics that outperform the baselines.

Table 4.

TEST metrics where the MMoE outperforms the best classical baseline. Outputs were calibrated post hoc; AUROC/AUPRC on TEST. * ED30 uses the MMoE + ClinicalBERT blend.

3.3.3. Findings

- Mortality: Clear improvement over the best classical baseline (LR–L2): AUROC of 0.817 vs. 0.799 and AUPRC of 0.163 vs. 0.091 (Table 4).

- ICU: Essentially tied on AUROC (0.878 vs 0.877), with a higher AUPRC (0.689 vs. 0.659).

- AKI: AUROC slightly lower (0.718 vs. 0.745), and AUPRC is higher (0.344 vs. 0.313).

- ED30: Structured EHR alone is hard (MMoE ∼0.617); leakage-safe text fusion raises AUROC to ∼0.659.

- LOS: Tree models remain stronger (RF–REG: vs. MMoE: ).

3.3.4. Discrimination Under Class Imbalance

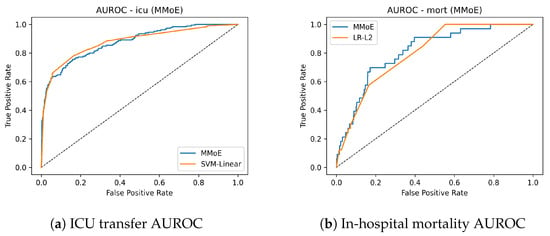

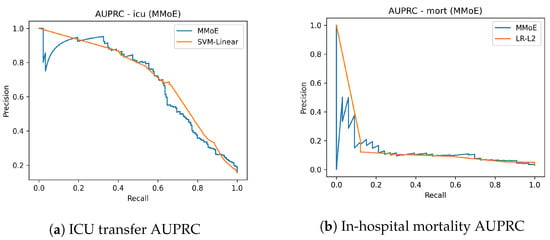

On mortality, where informative signal is sparse and class imbalance is severe, the MMoE models nearly doubles the precision–recall performance relative to the best classical baseline (AUPRC 0.163 vs. 0.091) while lifting the AUROC to (0.817 vs. 0.799). This is the hardest and most clinically critical endpoint; the gain indicates that cross-task sharing helps uncover weak, dispersed risk patterns that single-task learners generally miss (Table 4). For ICU transfer, the model ties or slightly improved discrimination relative to the compared counterpart (AUROC 0.878 vs. 0.877; AUPRC 0.689 vs. 0.659), showing that consolidation into one backbone does not degrade a common endpoint. For AKI, the results reflect the expected trade-off: AUROC is modestly lower (0.718 vs. 0.745), while AUPRC improves (0.344 vs. 0.313), suggesting better ranking in the high-risk but rare outcomes—often the actionable regime for alerts. Figure 2 shows the AUROC curves for ICU transfer prediction on the test set. The MMoE model achieved a similar AUROC to the best classical baseline while improving sensitivity in clinically relevant operating regions. Complementary precision–recall curves are shown in Figure 3. The mortality AUROC and AUPRC curves (Figure 2 and Figure 3) demonstrate that the MMoE model produced better calibrated high-risk predictions compared to Logistic Regression.

Figure 2.

ROC curves for ICU transfer and in-hospital mortality (TEST).

Figure 3.

Precision–recall curves for ICU transfer and mortality (TEST).

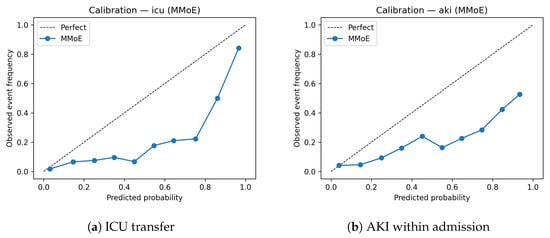

3.3.5. Calibration for Decision Support

After validation-fit calibration, the MMoE model attained a lower Brier/ECE on mortality, and its ED30 is comparable on AKI; it incurred only a small ECE deficit on ICU (Table 3). In other words, the endpoints that most need calibrated probabilities (rare and noisy) benefit most from multitask sharing. This is consistent with our design goal of producing probabilities that can be thresholded, combined, and governed in production. This also matches the following intuition: tasks with rarer, noisier signals benefit more from multitask sharing and Platt correction. Calibration curves (Figure 4) indicate that the MMoE model is reasonably well calibrated for ICU transfer, with slight underestimation in the highest decile. Similar patterns were observed for AKI.

Figure 4.

Calibration curves for the MMoE model on the TEST set.

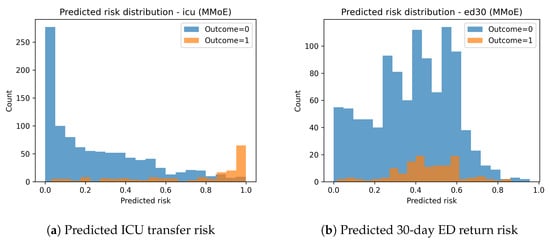

The predicted risk distributions in Figure 5 show clear separation between positive and negative cases for ICU transfer. ED30 risk distributions demonstrate significant class overlap, aligning with the lower predictive performance for this task.

Figure 5.

Distribution of MMoE risk scores on the TEST set.

3.3.6. Notes-Aware Readmission (ED30) Without Leakage

The availability fo structured EHR data alone makes ED30 difficult (MMoE AUROC ∼0.617). Because discharge-time notes preceded the outcome, we evaluated leakage-safe text fusion. A lightweight ClinicalBERT blend consistently raised the ED30 AUROC to ∼0.659 and significantly outperformed the text-only configuration (Table 5 and Table 6). This matters, as ED revisits are operationally consequential yet poorly captured by structure; a conservative text bridge recovers signal without compromising auditability.

Table 5.

ED30 text–EHR fusion variants.

Table 6.

DeLong pairwise AUROC tests for ED30 (TEST). Bold p indicates .

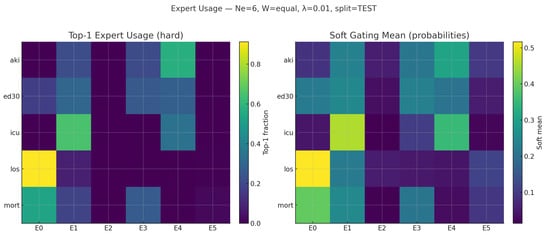

3.3.7. Expert Routing and Interpretability

Gate summaries and heat maps reveal macro-specialization with micro-redundancy: a severity/resource axis (E0) leads mortality/LOS, a decompensation axis (E1) leads ICU/ED30, and a renal axis (E4) leads AKI, while 3–5 experts are softly mixed per task. These patterns are clinically coherent and provide a readable reason for why a score is high—an ingredient for clinician trust and post hoc auditing.

Figure 6 reports two complementary views for the selected model:

Figure 6.

Expert routing for the selected configuration (, TEST, , ). (Left) Hard top-1 expert selection by task; (Right) mean soft gate probabilities.

- A hard top-1 routing matrix (left), where each row sums to 1 and shows, for a given task, the fraction of patients routed to each expert as the primary winner;

- A soft heat map of mean gate probabilities (right), which visualizes how much each task consults each expert, on average. Hard routing exposes who leads, whereas soft routing shows who helps.

- Quantifying specialization vs. mixing:

For each task (t), we summarized the gate as follows:

- Soft-mix entropy: Let be the gate probability that task t assigns to expert e for sample , and let n be the number of evaluation samples. The effective number of mixed experts is , with . Here, it is important to note that high entropy indicates broader mixing, whereas low entropy indicates specialization.

- Max-hard (decisiveness): Let the hard (top-1) expert for beand define the top-1 frequency for expert e asThen, the decisiveness for task t is

- Task-dead experts: The count of experts with for task t (never selected top-1). An expert can be dead for one task (never top-1) yet active for others (nonzero on a different task); “dead” refers only to hard top-1 selection.

Table 7 reports these summaries. In our cohort, nats (effective ∼3.5–5 experts), while max-hard spans 0.30–0.91, indicating macro-specialization with micro-redundancy: one expert often leads, but 3–5 experts are mixed softly as backups.

Table 7.

Expert spread per task (TEST, , , ).

A clinically coherent division of labor can be easily observed in Figure 6:

- Severity/resource axis (E0): Leads to Mortality and LOS (high max-hard, e.g., LOS ∼0.91), reflecting general severity and resource utilization.

- Acute decompensation (E1): Leads to ICU and is prominent in ED30; this is consistent with early deterioration signals.

- Renal axis (E4): Leads to AKI, with E1/E3 as secondary contributors, capturing renal-specific patterns distinct from mortality/LOS.

- Even when a task has a clear primary expert (e.g., LOS→E0), the soft gate still allocates non-trivial mass to other experts, which we found helpful for calibration and robustness.

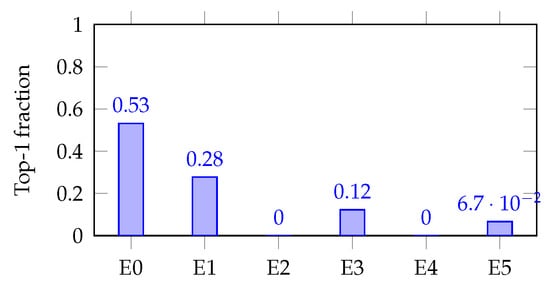

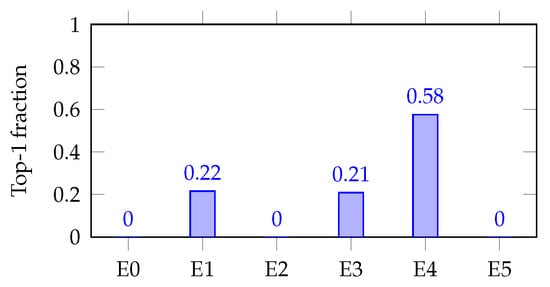

- Per task bar charts (decisiveness examples):

Figure 7 and Figure 8 (single-task bar plots) show how decisiveness is concrete. Mortality shows a dominant expert (E0; max-hard ), but with visible secondary routes (E1/E3). AKI concentrates on E4 (max-hard ), backed by E1/E3. These patterns mirror the soft heat map and align with expected clinical axes.

Figure 7.

Expert utilization for mortality (TEST, ).

Figure 8.

Expert utilization for AKI (TEST, ).

- Illustrative examples (schematic):

The following schematic examples (aggregate-derived, not single patient records) are presented to illustrate how routing aligns with clinical pathways:

- Case A (prolonged LOS): Early-window labs/vitals are stable, but operational signals are high (multiple service transfers, medication burden). The gate routes strongly to E0 (LOS/“severity–resource” axis), with secondary mass on E1/E5. The prediction is for higher LOS risk and neutral mortality.

- Case B (AKI risk): Rising creatinine from a low admission-day baseline with nephrotoxin exposure. The gate routes primarily to E4 (renal axis), with E1/E3 assistance. The prediction is for elevated AKI risk and less decisive results for LOS/mortality.

These schematic examples reflect what the matrices show at scale: coherent expert subchannels (severity–resource, acute decompensation, and renal) with soft mixing for redundancy.

For decision support, who handled a prediction is as important as how high the score is. Expert identities (E0/E1/E4) act like named latent pathways; entropy/max-hard/task-dead metrics provide quick health checks against expert collapse, and the soft mixing we observed likely contributes to the MMoE model’s better post hoc calibration on mortality and ED30.

3.3.8. Robustness Probes

We stress-tested routing by varying the gate temperature (), enforcing top-K gating (), and masking experts one at a time. Discrimination and calibration remained stable across these probes, indicating that the learned specialization is not brittle.

3.3.9. Efficiency and System Cost

The MMoE models contains 85 k parameters (0.34 MB) and runs at ∼0.027 s/sample, replacing a ∼60 MB five-model stack with a single pass (Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10). This consolidation makes it compact and fast while simplifying calibration governance, monitoring, and change control—practical constraints that often block otherwise strong models from clinical use.

Table 8.

Efficiency metrics across baselines and the MMoE model ().

Table 9.

Model size and per sample inference time for best baselines per task (TEST).

Table 10.

System-level efficiency to compute all five outcomes (TEST).

3.3.10. LOS Head and the Case for a Hybrid

For LOS, a tree regressor remains stronger on TEST (RF–REG vs. MMoE ; Table 2). Therefore, we recommend a hybrid deployment by serving the four classification heads from the MMoE model and the LOS from the RF regressor behind the same API. This keeps the interface unified while preserving the best single-task performance.

- Summary:

The proposed single-backbone MMoE model achieved what individual predictors could not: (i) it improved rare but clinically critical outcomes (mortality AUPRC +0.072, ICU AUPRC +0.030, and ED30 AUROC +0.030); (ii) it produced reliable probabilities that can be thresholded and audited, particularly on low-prevalence endpoints; (iii) it revealed a clinically coherent structure through stable and redundant expert routing rather than opaque black-box behavior; and (iv) it compressed the deployment cost by replacing a ∼60 MB ensemble with a compact 0.34 MB model. Together, these advances demonstrate that a single, interpretable, and efficient backbone can deliver both performance and trustworthiness; they are precisely the qualities required for multi-endpoint hospital decision support and as a foundational risk layer in oncology digital-twin pipelines.

4. Clinical Validation Pathways and Workflow Integration

Although our focus in this work is on the technical performance of the MMoE encoder, any practical use of this model in a hospital would require a clear path for clinical integration. In most hospitals, laboratory values, vitals, and medication orders enter the electronic medical record (EMR) through standard interfaces such as HL7 or FHIR [51]. These streams can be used to generate the structured inputs needed by the model. In a deployment scenario, the risk scores would simply appear in the same clinical views that the staff already use—rather than in a separate interface—so that they fit naturally into existing monitoring or triage workflows.

Before a model like this influences healthcare, hospitals typically run a “silent” phase [52] where predictions are produced in the background. while remaining invisible to clinicians. This allows teams to monitor calibration drift, stability, and whether the scores behave sensibly across common clinical situations. If the model remains reliable, the next step is a small observational pilot where clinicians can view the scores without acting on them. Only after these stages would a controlled evaluation be considered [53].

To make this monitoring operational during a silent deployment, a practical surveillance framework could combine calibration tracking, performance monitoring, and data-drift detection. For calibration, the hospital analytics team could compute the Brier score, the expected calibration error (ECE), and the calibration intercept/slope on a rolling 30-day window, with alerts triggered when these metrics deviate meaningfully from the baselines established on the validation set (e.g., ECE increases beyond a predefined tolerance band). Updated reliability curves could be regenerated monthly and compared against the original validation curves using standard goodness-of-fit tests (such as the Hosmer–Lemeshow test) and visual inspection. In parallel, discrimination metrics (AUROC and AUPRC) would be tracked for each of the five prediction tasks, with pre-specified thresholds for acceptable degradation (for instance, an AUROC drop larger than 0.05 from the baseline). These checks can be stratified by demographic subgroups, admission type, or severity to detect differential degradation across populations. Finally, incoming feature distributions can be compared to those of the training data using simple drift statistics (e.g., Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests or population stability indices) to flag covariate shift, which may precede performance loss. If any monitoring threshold is breached, the protocol would trigger model review and either recalibration (e.g., updated Platt scaling or isotonic regression) or full retraining on more recent data before promoting the model beyond the silent phase. While our retrospective study does not implement this pipeline, outlining it clarifies how calibration drift and performance degradation could be managed in a real deployment.

5. Operational Efficiency and System Footprint

Beyond predictive capabilities, a clinically deployable system should place minimal computational burden on hospital infrastructure. The final MMoE model is deliberately lightweight, containing only 85k trainable parameters (0.34 MB on disk) and requiring approximately 0.027 s per admission for inference on a standard CPU. This footprint enables real-time scoring in producing EMR environments without dependence on GPU acceleration. A typical hospital server (8–16 CPU cores and 32–64 GB RAM) could score thousands of patients per minute while maintaining sufficient headroom for routine EMR operations. The model’s memory access pattern is also extremely compact, allowing for efficient embedding into containerized microservices or on-premise HL7/FHIR middleware. These properties support seamless workflow integration, enabling the risk-scoring service to run in parallel with existing clinical decision-support modules without interfering with EMR latency or resource allocation.

6. Implementation Considerations: API, Privacy, and Interoperability

If a system like this were used in practice, the model would sit behind a small service layer that receives structured features and returns the calibrated risk scores for each endpoint. In most hospitals, laboratory values, vitals, and medication orders already move through HL7 or FHIR interfaces, so an integration script can convert these streams into the fixed feature representation used by the MMoE encoder. The service itself would likely take the form of a simple REST-style API that accepts JSON inputs and produces the corresponding predictions, without needing direct access to the EMR.

Any clinical deployment would also have to follow standard privacy and security practices. Requests to the model would be encrypted, authenticated through the hospital’s existing access controls, and logged through routine audit mechanisms. Since the model processes inputs in memory and does not store patient data, the main considerations are the security of the communication channels and the boundary between the service and the clinical network. These requirements are typical for clinical decision-support tools and help to ensure that the predictive layer can be integrated into existing hospital IT infrastructure without major system changes.

7. Decision Thresholds and Use of Calibrated Probabilities

Because the model outputs calibrated risks, choosing an operating threshold becomes a clinical rather than a modeling decision. In practice, teams typically review how sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV change across a grid of thresholds on the validation set and select the point that best matches local priorities [54]. For example, ICU transfer predictions often prioritize sensitivity, since missing a deteriorating patient carries greater harm than evaluating an additional false-positive alert [55]. In contrast, thresholds for prolonged length of stay or mortality may aim for a more balanced trade-off or may target a specific risk percentile (e.g., flagging the top 5–10% of highest-risk admissions).

Hospitals also frequently use simple risk tiers (e.g., low, intermediate, and high) instead of a single cutpoint, which makes the interpretation easier and reduces alert fatigue [56]. These thresholds are typically determined through clinician review of confusion matrices at different operating points and by consideration of unit resource constraints. Since calibration and practice patterns can shift over time, thresholds are revisited periodically in most clinical decision-support deployments [57]. Our calibrated probability outputs are compatible with any of these approaches and allow institutions to tailor the operating point to their workflow and tolerance for false alarms.

8. Discussion

Our design decisions were motivated by a simple clinical reality: hospitalized patients with PCa rarely face a single risk in isolation. Mortality, ICU transfer, AKI, ED30, and prolonged LOS all co-evolve during the same admission and influence the same decisions about monitoring, escalation, and discharge, yet most predictive models treat these outcomes separately, yielding fragmented signals, inconsistent probability scales, and duplicated calibration and monitoring overhead. This paper shows how a compact MMoE framework can unify these risks into a single predictive backbone—one that is not only accurate but also calibrated, interpretable, and deployable.

8.1. Performance Where It Matters Most

The clearest strength of the proposed MMoE lies in rare-event detection, where improvements are most needed. For in-hospital mortality, the AUPRC nearly doubled compared to the best classical baseline (0.163 vs. 0.091), alongside a gain in AUROC (0.817 vs. 0.799). For ICU transfer, a more common event, the model maintained top discrimination (AUROC 0.878) and still improved AUPRC (+0.030 over the best SVM). ED30—one of the hardest endpoints to predict from structure alone—saw its AUROC rise from 0.629 to 0.659 once leakage-safe notes were fused in. Even AKI, where AUROC slipped modestly, showed improved AUPRC (+0.031), highlighting the model’s ability to better rank the highest-risk patients. Together, these results show that multitask sharing amplifies weak signals in the tail while preserving robustness on frequent outcomes.

8.2. Probabilities Clinicians Can Use

In clinical deployment, raw rankings are not enough; decisions depend on whether a predicted risk behaves like a probability. After Platt calibration, the MMoE delivered lower Brier scores and ECE for the endpoints where calibration is hardest and most valuable—mortality and ED30. This means thresholds can be set with confidence and probabilities can be communicated, audited, and compared across tasks without additional scaling. The addition of a simple entropy load-balancing penalty further reduced calibration error, underscoring that small architectural choices can translate into more trustworthy probabilities at the bedside.

8.3. Interpretability That Maps onto Clinical Reasoning

Black-box performance is not enough to earn clinical trust. The MMoE model’s routing diagnostics revealed a division of labor that clinicians would recognize: one expert focusing on severity and resource use (mortality and LOS), another on acute decompensation (ICU and ED30), and another on renal function (AKI). Importantly, this was not brittle specialization: each task still mixed three to five experts softly, providing redundancy and stability. These interpretable routing patterns are more than visualizations—they offer an audit trail of which pathway drove a prediction and quick health checks against expert collapse. This transparency makes the model easier to explain, easier to govern, and easier to trust.

8.4. Leakage-Safe Text Fusion

Our design also demonstrates discipline in multimodal integration. ED30 predictions benefited from incorporating clinical notes through a ClinicalBERT blend, lifting AUROC to ∼0.659 and significantly outperforming text-only baselines. Just as important is what we did not do: mortality, ICU, and AKI heads remained purely tabular to avoid leakage. This restraint preserves auditability and ensures that gains are genuine rather than artifacts of post-outcome information—an important signal to clinical stakeholders.

8.5. Compactness as an Enabler

A key lesson from our experiments could be articulated as follows: high performance does not require bloated models. The MMoE model is lightweight, comprising only 85 k parameters, a 0.34 MB footprint, and ∼27 ms inference per sample. This single model replaces a ∼60 MB stack of five baselines. In practice, this lowers the surface area for drift detection, reduces calibration and monitoring burden, and simplifies IT governance. In hospital environments, where every additional artifact is a liability, compactness is not just a convenience—it is the difference between a promising prototype and a system that can be deployed.

8.6. A Principled Configuration, Not a Lucky Guess

Through ablations, we identified a “knee” operating point at experts with . Moving from 4 to 6 experts yielded clear gains in discrimination and calibration, while pushing to 8–10 only added complexity, without consistent benefit. These sweeps provide a principled rationale for our chosen setting and show that the strengths of the model are not the product of arbitrary hyperparameters but of a reproducible trade-off between performance, interpretability, and size.

8.7. Hybridization Where Appropriate

The only endpoint where a specialized model remained superior was LOS regression, where a random forest regressor outperformed the MMoE. Rather than obscuring this, we propose a hybrid deployment strategy: use the MMoE model for the four classification heads and a tree for LOS, all served behind the same interface. This ensures each outcome is handled by its most effective predictor while maintaining the simplicity of a unified system.

8.8. Why This Matters for Digital Twins

Digital twins require two pillars—namely, a state-to-risk mapping and an action-to-outcome mapping. The MMoE fills the first role. By producing coherent, calibrated, and interpretable risk estimates across multiple acute endpoints in a single pass, the developed model lays the groundwork for prescriptive layers that can simulate treatments and recommend policies. Without a stable and trustworthy risk layer, DTs remain conceptual. However, with the risk layer, they can move closer to actionable decision support in oncology.

8.9. Clinical and Governance Alignment

Finally, our design choices reflect an awareness of deployment realities. Restricting inputs to the first 12 h aligns with actionable decision windows. Exposing thresholds, calibrators, and gate summaries as first-class outputs enables co-design with clinicians and provides the auditability demanded by clinical QA and regulators. These elements are often afterthoughts in machine learning research; here, they were integral to the design.

8.10. Takeaway

The proposed MMoE model transforms five disjoint prediction problems into a single calibrated, interpretable, and operationally light risk layer. It excels where detection is hardest (rare events); outputs risks that reflect observed frequencies, enabling reliable decisions; reveals clinically coherent structure; and packages everything into a form that can be governed and deployed. This is precisely what is needed to move multi-endpoint prediction from a research curiosity to a critical enabling component of digital twins and precision inpatient care.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we set out to design a practical and interpretable predictive layer for DTs in prostate cancer care. Our motivation was straightforward: hospitalized patients face multiple acute risks simultaneously, yet most existing models treat each outcome in isolation. This fragmentation produces inconsistent risk scales, complicates calibration, and increases the maintenance burden. By turning to an MMoE design, we sought a single model that could capture cross-task structure while retaining flexibility for task-specific specialization.

The results confirm the promise of this approach. On a real-world prostate cancer cohort from MIMIC-IV, the MMoE model not only improved discrimination of rare outcomes such as mortality, with the AUPRC nearly doubling compared to the best single-task baseline, but also maintained competitive performance on more common endpoints like ICU transfer and AKI. For ED30, where readmission risk is notoriously difficult to capture from structured data alone, the careful addition of leakage-safe text features provided further gains. Importantly, these performance improvements came without sacrificing calibration: Platt-adjusted probabilities were well aligned with observed event rates, thereby making the outputs suitable for threshold-based decision support.

Equally significant is what the model revealed about its internal organization. Expert-routing diagnostics consistently exposed clinically meaningful divisions of labor, such as renal-focused experts for AKI and severity-driven experts for LOS and mortality. This interpretability is not just a technical curiosity but a step toward clinical trust, offering a window into how the model partitions patient signals. Coupled with its efficiency—85k parameters in a 0.34 MB footprint and inference times measured in milliseconds—the MMoE model demonstrates that high-performing models can also be lightweight, auditable, and deployment-ready. In short, it fulfills the practical promise we outlined at the start—namely, a single predictive backbone that balances accuracy, calibration, interpretability, and efficiency.

Our evaluation used a patient-level split that prevents leakage across admissions and gives a stable estimate of discrimination and calibration. However, clinical data are not stationary over time; protocols, documentation patterns, and patient case mix can shift due to changes in coding practices, the introduction of new treatments, or evolving admission criteria. As a natural extension, it would be useful to examine cross-temporal generalization by training the model on earlier segments of the MIMIC-IV timeline and evaluating it on later years. Although exact event timestamps in MIMIC-IV are partially de-identified, the broader ordering of admissions over the database’s timespan is preserved, making temporal holdout feasible. Such an evaluation would provide insight into how sensitive the MMoE encoder is to practice drift and how often recalibration or periodic retraining may be needed in deployment.

Because this study is based entirely on MIMIC-IV, the model reflects the clinical patterns and documentation practices of a single academic medical center. MIMIC-IV over-represents certain demographic groups and care pathways, and it does not include outpatient history or longitudinal follow-up, which limits how fully the model can represent patients outside the inpatient setting. These factors can introduce bias into the learned associations and may affect how well the model transfers to hospitals with different patient populations, resource constraints, or workflow structures. Any use of the model in a new environment would therefore require local validation to assess calibration, subgroup performance, and the extent to which practice patterns differ from those captured in MIMIC-IV.

This analysis is based on a static retrospective snapshot of MIMIC-IV; therefore, the model was not exposed to changes in practice patterns, documentation conventions, or patient case mix that can occur over time. In a real clinical setting, these shifts, often described as concept drift, can affect both calibration and discrimination. While the MMoE architecture does not inherently prevent drift, it is compatible with routine maintenance steps used in other clinical decision-support tools. These include periodic evaluation on more recent cohorts, monitoring of calibration curves, and retraining or reweighting of the model if performance begins to degrade. Drift-detection methods that track changes in the distribution of key features or outputs can also be layered on top of the predictive model. Incorporating these steps would be necessary for any long-term deployment, even though they are beyond the scope of the present retrospective study.

Although our analysis focuses on aggregate performance, any prospective use of the model would require monitoring for differential performance across demographic groups. Clinical datasets such as MIMIC-IV are known to be imbalanced with respect to age, race, and socioeconomic factors, and these imbalances can lead to systematic differences in calibration or error rates. In practice, hospitals typically assess bias by examining discrimination and calibration curves within subgroups and by monitoring whether thresholds or positive predictive values differ in clinically meaningful ways. If disparities are detected, common mitigation strategies include recalibration on local data, subgroup-specific thresholds, or targeted retraining on under-represented cohorts. Because practice patterns and population mix evolve over time, these checks would need to be repeated as part of routine model maintenance. While such mechanisms are beyond the scope of the present retrospective study, the calibrated outputs of our MMoE model are compatible with these standard auditing and mitigation workflows.

Looking ahead, several avenues invite further exploration. While MIMIC-IV provided a rich and diverse test bed, external validation across institutions and oncology-specific cohorts is essential to confirm generalizability, especially in settings with different practice patterns and richer longitudinal variables such as PSA trends, Gleason scores, and therapy timelines. Similarly, some of our outcome definitions were deliberately pragmatic—for example, AKI labeling followed a KDIGO-inspired, SCr-only variant, and text was restricted to ED30 to prevent leakage. Future work could relax these constraints, experimenting with alternative operationalizations that may capture subtler aspects of disease progression and readmission risk. For heterogeneous tasks such as LOS prediction, where tree-based regressors remain strong, a hybrid deployment that combines the MMoE architecture with specialized models is another promising direction.

Beyond these methodological extensions, the natural next step is to incorporate prescription along with prediction. While we frame our motivation in the context of future digital-twin systems, the present study focuses specifically on the prognostic layer rather than a full digital twin. A true digital twin must not only forecast risks but also simulate interventions and recommend safe courses of action. The MMoE model can serve as the prognostic core of such a system, complementing causal policy layers that estimate treatment effects and enforce safety constraints. Finally, deployment will require attention to human factors: thresholds and alerts should be co-designed with clinicians to balance net benefit and workload, while per expert feature attributions and auditable logs will be vital for regulatory compliance and clinical QA.

In conclusion, the proposed MMoE framework demonstrates that a compact, interpretable, and efficient model can unify multiple acute risk predictions for prostate cancer inpatients. By addressing the three-fold challenge of performance, interpretability, and deployability, it provides a strong foundation for digital-twin systems in oncology. At the same time, it opens a clear agenda for future research, extending validation, enriching data modalities, integrating prescriptive logic, and engaging directly with clinical stakeholders. Together, these steps will help transform multitask predictors from research prototypes into practical tools for precision oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A., J.R., and A.J.; methodology, R.A., J.R., and A.J.; software, A.J.; validation, A.J.; investigation, R.A., J.R., and A.J.; data curation, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.; writing—review and editing, R.A., J.R., and A.J.; supervision, R.A., and J.R.; project administration, R.A., and J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study uses the publicly available, de-identified MIMIC-IV database, which is exempt from institutional review board approval under the PhysioNet credentialed access framework.

Informed Consent Statement

The study uses only de-identified secondary data from MIMIC-IV; no identifiable human subjects were contacted or enrolled.

Data Availability Statement

The MIMIC-IV dataset is available to credentialed researchers through PhysioNet (https://physionet.org) under a data use agreement. Because redistribution of the dataset is prohibited, patient-level data cannot be shared. All reproducibility artifacts—including cohort construction SQL, BigQuery pipelines, model training code, and evaluation scripts—are available in the accompanying public GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI) for language and stylistic refinements of this manuscript. The tool was not used for data analysis, interpretation of results, or drafting of scientific content. All substantive ideas and conclusions are the authors’ own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Prostate Cancer: Cancer Stat Facts. 2025. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Moodie, L.; Ilie, G.; Rutledge, R.; Andreou, P.; Kirkland, S. Assessment of current mental health status in a population-based sample of Canadian men with and without a history of prostate cancer diagnosis: An analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 586260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.B.; Duan, Z.; Chamie, K.; Hoffman, K.E.; Smith, B.D.; Hu, J.C.; Shah, J.B.; Davis, J.W.; Giordano, S.H. Risk of hospitalisation after primary treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2016, 120, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Pate, A.; Dhiman, P.; Archer, L.; Martin, G.P.; Collins, G.S. Clinical prediction models and the multiverse of madness. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Alhajj, R.; Rokne, J. A systematic review of AI as a digital twin for prostate cancer care. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 268, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakis, E.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H.; Shahriyari, L.; Fletcher, R.; Liu, J.; Achenie, L.; Liu, H.; Jackson, P.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Digital twins for health: A scoping review. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.A.; Jordan, M.I.; Nowlan, S.J.; Hinton, G.E. Adaptive Mixtures of Local Experts. Neural Comput. 1991, 3, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, X.; Chen, J.; Hong, L.; Chi, E.H. Modeling Task Relationships in Multi-task Learning with Multi-gate Mixture-of-Experts. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (KDD ’18), London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Z. Med-moe: Mixture of domain-specific experts for lightweight medical vision-language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.10237. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, N.C.; Dhruva, S.S.; Desai, N.R.; Ross, J.R.; Ngufor, C.G.; Masoudi, F.; Krumholz, H.M.; Mortazavi, B.J. Clinical Phenotyping with an Outcomes-driven Mixture of Experts for Patient Matching and Risk Estimation. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 2023, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models with Simple and Efficient Sparsity. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 23, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Roux, A.; Mensch, A.; Savary, B.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Hanna, E.B.; Bressand, F.; et al. Mixtral of Experts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan, H.; Khachatrian, H.; Kale, D.C.; Ver Steeg, G.; Galstyan, A. Multitask learning and benchmarking with clinical time series data. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Mincu, D.; Loreaux, E.; Mottram, A.; Protsyuk, I.; Harris, N.; Xue, Y.; Schrouff, J.; Montgomery, H.; Connell, A.; et al. Multitask prediction of organ dysfunction in the intensive care unit using sequential subnetwork routing. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 1936–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Dede, M.; Mohanty, V.; Dou, J.; Hill, H.; Bernstam, E.; Chen, K. Forecasting acute kidney injury and resource utilization in ICU patients using longitudinal, multimodal models. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 154, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Roberts, K. Deep patient representation of clinical notes via multi-task learning for mortality prediction. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2019, 2019, 779. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkomar, A.; Oren, E.; Chen, K.; Dai, A.M.; Hajaj, N.; Hardt, M.; Liu, P.J.; Liu, X.; Marcus, J.; Sun, M.; et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Mitra, A.; Liu, W.; Berlowitz, D.; Yu, H. TransformEHR: Transformer-based encoder-decoder generative model to enhance prediction of disease outcomes using electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.H.; Yin, G.; Bae, K.; Yu, L. Multi-task heterogeneous graph learning on electronic health records. Neural Netw. 2024, 180, 106644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhang, P. Multimodal risk prediction with physiological signals, medical images and clinical notes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Bahadori, M.T.; Sun, J.; Kulas, J.; Schuetz, A.; Stewart, W. Retain: An interpretable predictive model for healthcare using reverse time attention mechanism. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Fang, X.; Xu, R.; Kan, X.; Ho, J.C.; Yang, C. Multimodal fusion of ehr in structures and semantics: Integrating clinical records and notes with hypergraph and llm. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, P.N.M.; Dao, C.T.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.Z.; Liu, S.; Ding, J.E.; Restrepo, D.; Liu, F.; Hung, F.M.; Peng, W.C. Medfuse: Multimodal ehr data fusion with masked lab-test modeling and large language models. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 3974–3978. [Google Scholar]

- Guarrasi, V.; Aksu, F.; Caruso, C.M.; Di Feola, F.; Rofena, A.; Ruffini, F.; Soda, P. A systematic review of intermediate fusion in multimodal deep learning for biomedical applications. Image Vis. Comput. 2025, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Capurro, D.; Nguyen, A.; Verspoor, K. Attention-based multimodal fusion with contrast for robust clinical prediction in the face of missing modalities. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 145, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Gomez, D.; Borau, C.; Garcia-Aznar, J.M.; Gomez-Benito, M.J.; Girolami, M.; Perez, M.A. Physics-informed machine learning digital twin for reconstructing prostate cancer tumor growth via PSA tests. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, H.; Yousefirizi, F.; Shiri, I.; Brosch-Lenz, J.; Mollaheydar, E.; Fele-Paranj, A.; Shi, K.; Zaidi, H.; Alberts, I.; Soltani, M.; et al. Theranostic digital twins: Concept, framework and roadmap towards personalized radiopharmaceutical therapies. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Pash, G.; Hormuth, D.A.; Lorenzo, G.; Kapteyn, M.; Wu, C.; Lima, E.A.; Yankeelov, T.E.; Willcox, K. Predictive digital twin for optimizing patient-specific radiotherapy regimens under uncertainty in high-grade gliomas. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1222612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, G.; Heiselman, J.S.; Liss, M.A.; Miga, M.I.; Gomez, H.; Yankeelov, T.E.; Reali, A.; Hughes, T.J. A pilot study on patient-specific computational forecasting of prostate cancer growth during active surveillance using an imaging-informed biomechanistic model. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, G.; Ahmed, S.R.; Hormuth, D.A., II; Vaughn, B.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Solorio, L.; Yankeelov, T.E.; Gomez, H. Patient-specific, mechanistic models of tumor growth incorporating artificial intelligence and big data. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 26, 529–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eminaga, O.; Abbas, M.; Kunder, C.; Tolkach, Y.; Han, R.; Brooks, J.D.; Nolley, R.; Semjonow, A.; Boegemann, M.; West, R.; et al. Critical evaluation of artificial intelligence as a digital twin of pathologists for prostate cancer pathology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N.; Kardamakis, D. A smart IoT platform for oncology patient diagnosis based on ai: Towards the human digital twin. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, S.; Rojas-Valenzuela, I.; Rojas, F.; Valenzuela, O.; Herrera, L.J.; Rojas, I. Novel methodology for detecting and localizing cancer area in histopathological images based on overlapping patches. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 168, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, I.Y. Machine-learning-based digital twin system for predicting the progression of prostate cancer. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.R.; Islam, M.F.; Uddin, M.Z.; Ghoshal, G.; Hassan, M.M.; Huda, S.; Fortino, G. Prostate cancer classification from ultrasound and MRI images using deep learning based Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 127, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, A.; Attia, S.; Zhang, X.; Canahuate, G.; Fuller, C.D.; Marai, G.E. DITTO: A Visual Digital Twin for Interventions and Temporal Treatment Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2024, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Huang, X.; Wu, G.; Shen, X.; Zhu, D. Digital twin-driven water-wave information transmission and recurrent acceleration network for remaining useful life prediction of gear box. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.K.; Farag, M.M.; Hussein, M. Enhancing photovoltaic system efficiency through a digital twin framework: A comprehensive modeling approach. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 26, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Bulgarelli, L.; Pollard, T.; Horng, S.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R. Mimic-iv. PhysioNet. 2020. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/1.0/ (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Johnson, A.E.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng, S.; Pollard, T.J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B.; et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PhysioNet. License for MIMIC-III Clinical Database (v1.4). 2025. Available online: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciii/view-dua/1.4/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Code 185: Malignant Neoplasm of Prostate. 2015. Available online: https://www.icd9data.com/2015/Volume1/140-239/179-189/185/185.htm (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code C61: Malignant Neoplasm of Prostate. 2025. Available online: https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/C00-D49/C60-C63/C61- (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Khwaja, A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2012, 120, c179–c184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, G.G. Introduction to Modern Information Retrieval; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alsentzer, E.; Murphy, J.R.; Boag, W.; Weng, W.H.; Jin, D.; Naumann, T.; McDermott, M. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.03323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.C.; Kreda, D.A.; Mandl, K.D.; Kohane, I.S.; Ramoni, R.B. SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beede, E.; Baylor, E.; Hersch, F.; Iurchenko, A.; Wilcox, L.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Vardoulakis, L.M. A human-centered evaluation of a deep learning system deployed in clinics for the detection of diabetic retinopathy. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Faes, L.; Kale, A.U.; Wagner, S.K.; Fu, D.J.; Bruynseels, A.; Mahendiran, T.; Moraes, G.; Shamdas, M.; Kern, C.; et al. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e271–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.E.; Lasko, T.A.; Chen, G.; Siew, E.D.; Matheny, M.E. Calibration drift in regression and machine learning models for acute kidney injury. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churpek, M.M.; Yuen, T.C.; Winslow, C.; Meltzer, D.O.; Kattan, M.W.; Edelson, D.P. Multicenter comparison of machine learning methods and conventional regression for predicting clinical deterioration on the wards. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginestra, J.C.; Giannini, H.M.; Schweickert, W.D.; Meadows, L.; Lynch, M.J.; Pavan, K.; Chivers, C.J.; Draugelis, M.; Donnelly, P.J.; Fuchs, B.D.; et al. Clinician perception of a machine learning–based early warning system designed to predict severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.J.; Van Calster, B.; Steyerberg, E.W. Net benefit approaches to the evaluation of prediction models, molecular markers, and diagnostic tests. BMJ 2016, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]