Implementation and Performance Assessment of a DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator Using TSR-Driven MPPT for Enhanced Power Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

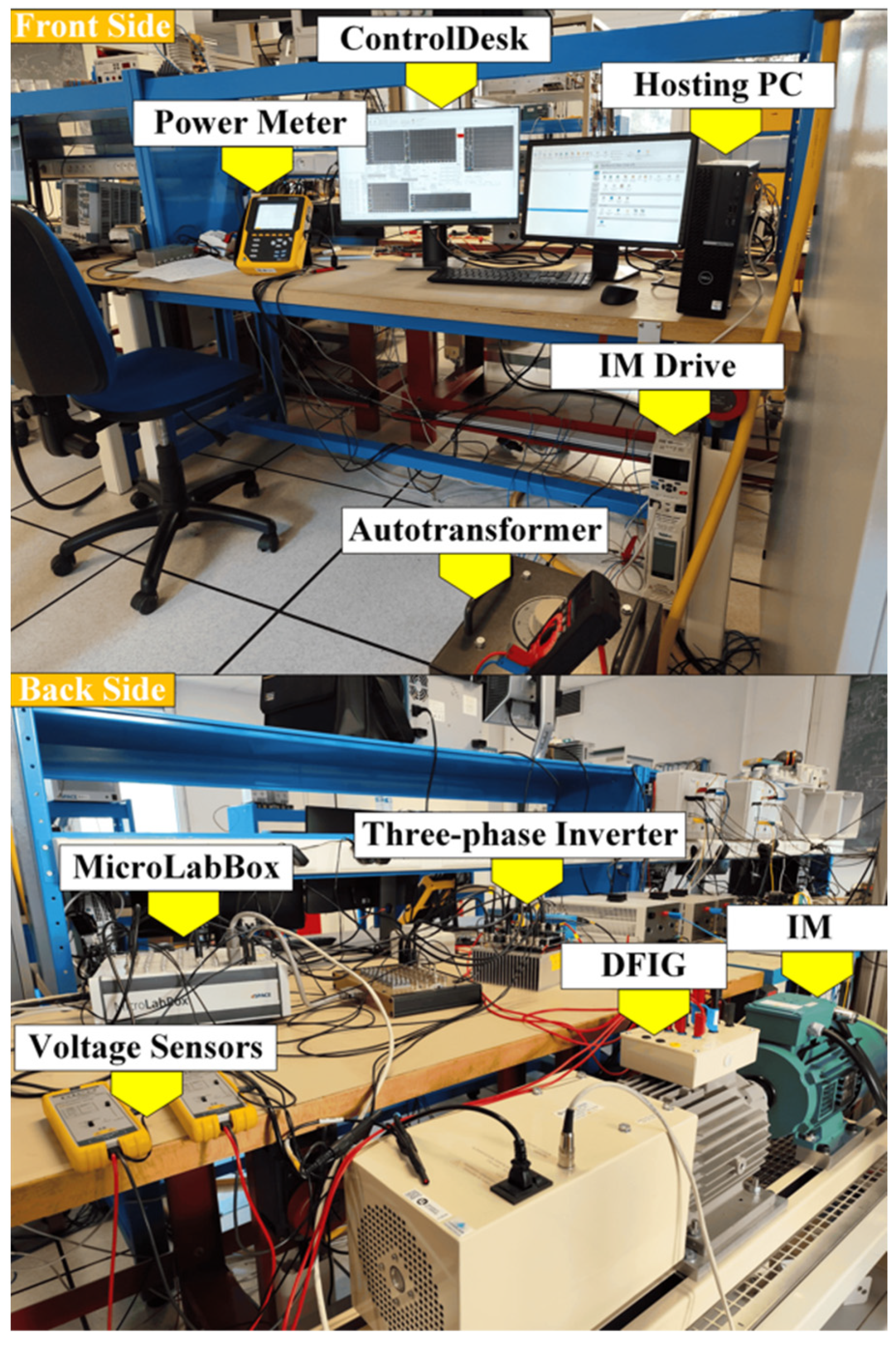

- A complete and fully documented hardware platform for a wind turbine emulator using an IM–DFIG configuration, offering a cost-effective and low-maintenance alternative to classical DCM-based setups.

- A high-performance control framework entirely implemented in C with RTLib, integrating TSR-based MPPT and DFIG flux-oriented control, enabling real-time operation beyond the limits of conventional Simulink/RTI implementations.

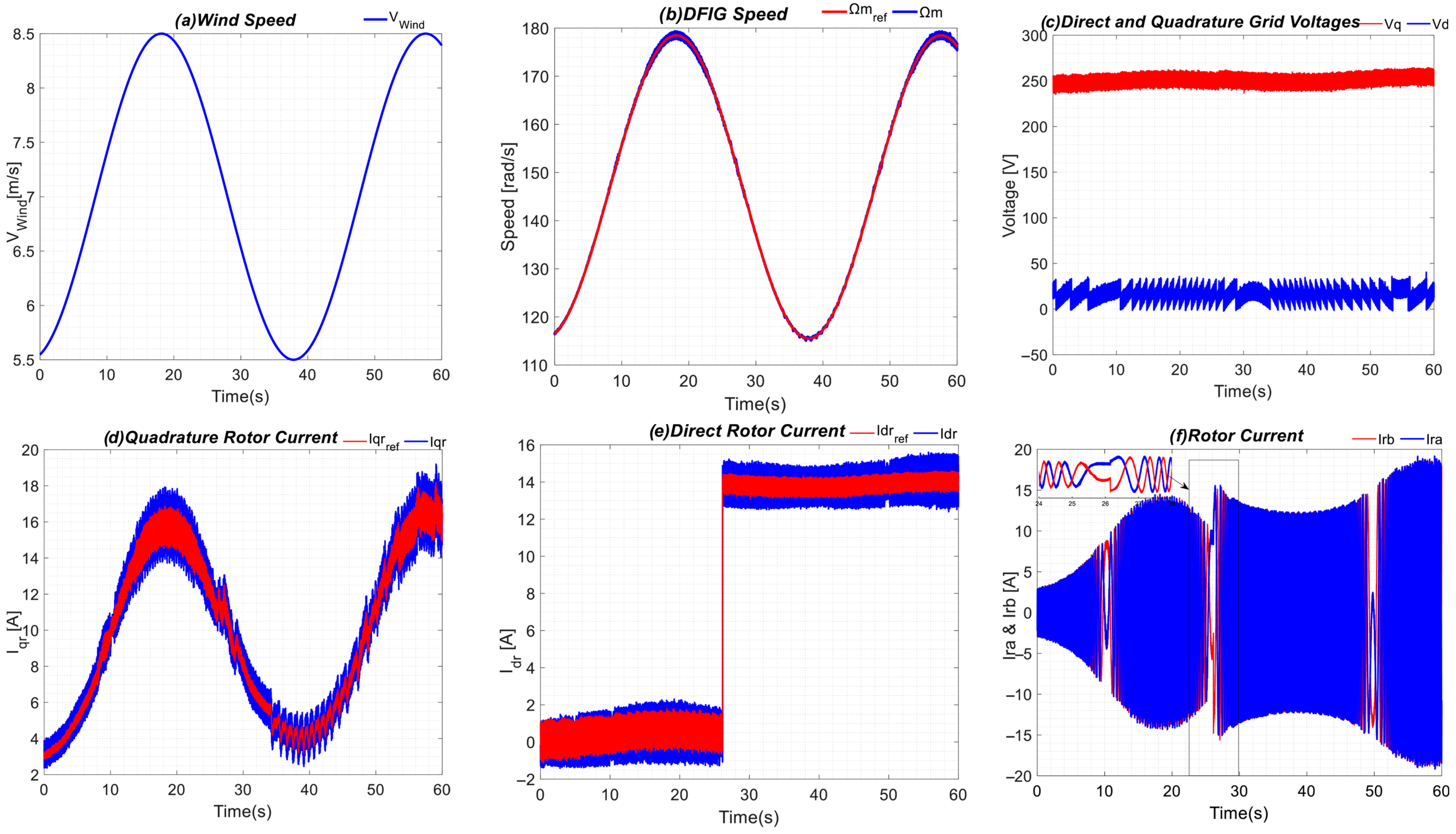

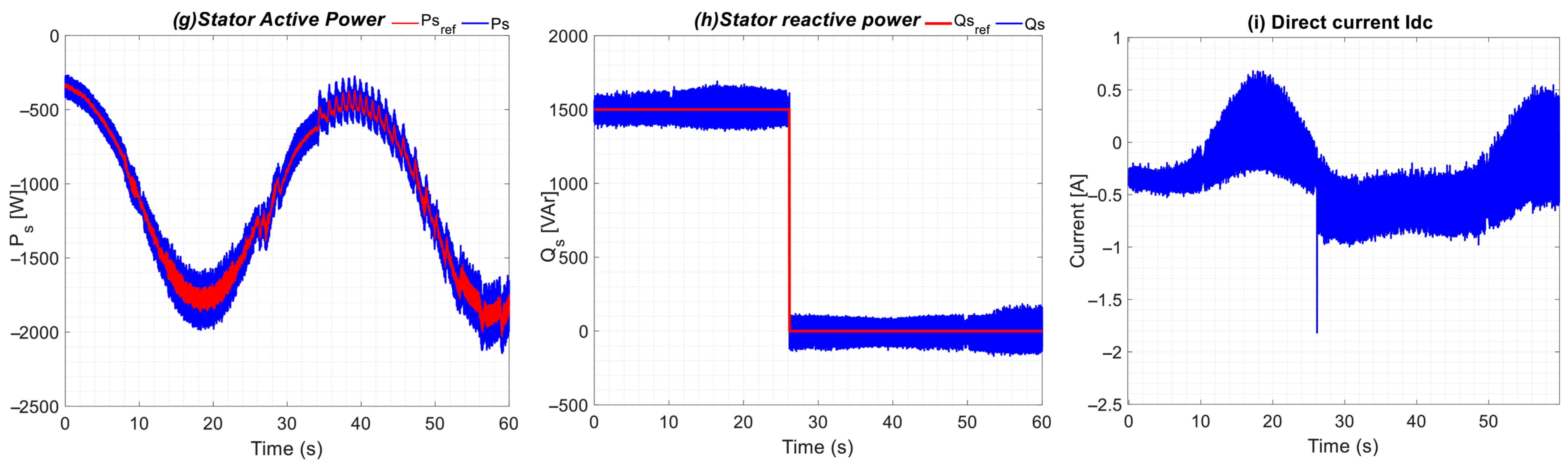

- An extensive experimental validation, demonstrating fast dynamics, accurate power regulation, and reliable operation under a wide range of emulated wind conditions.

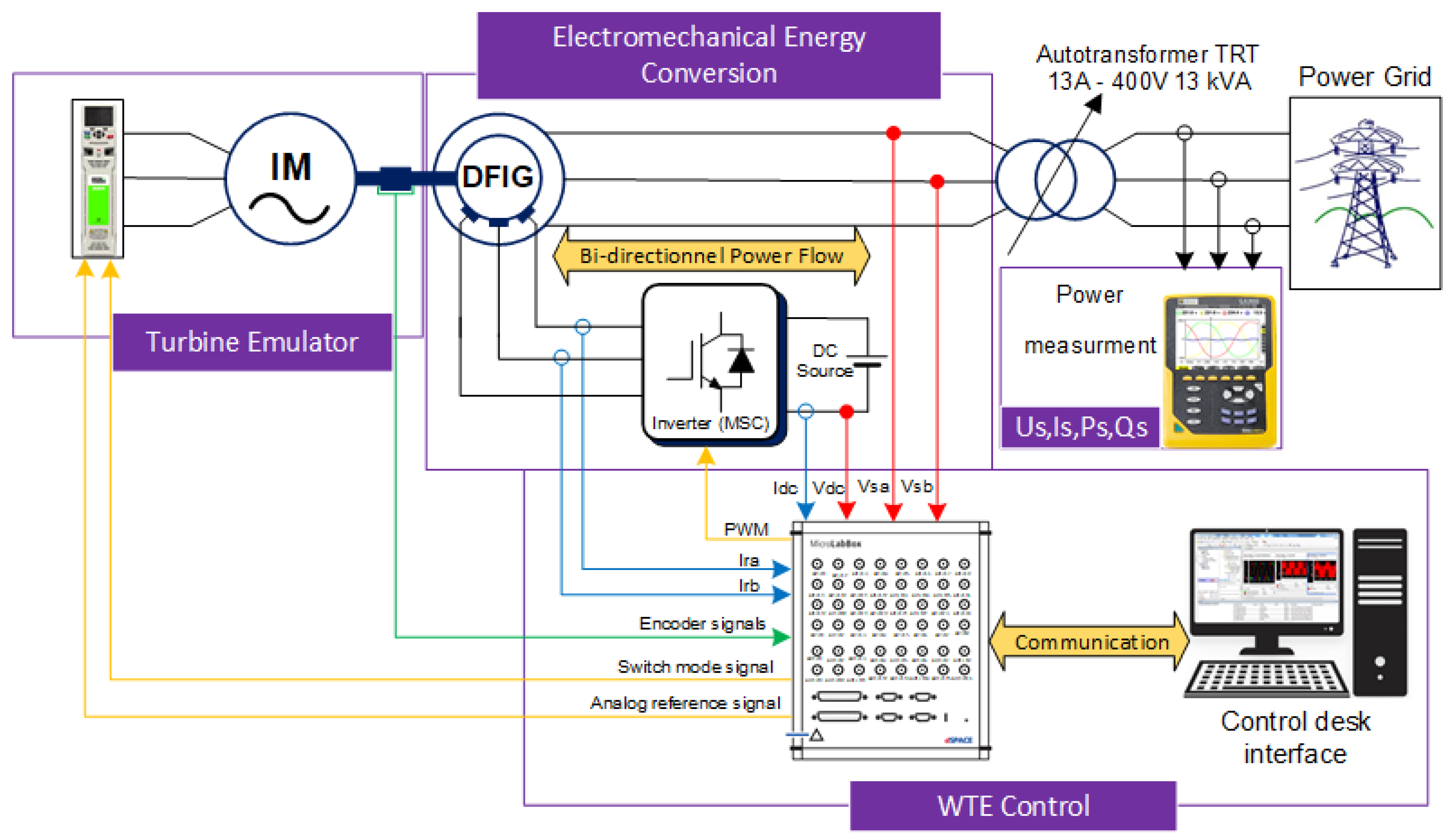

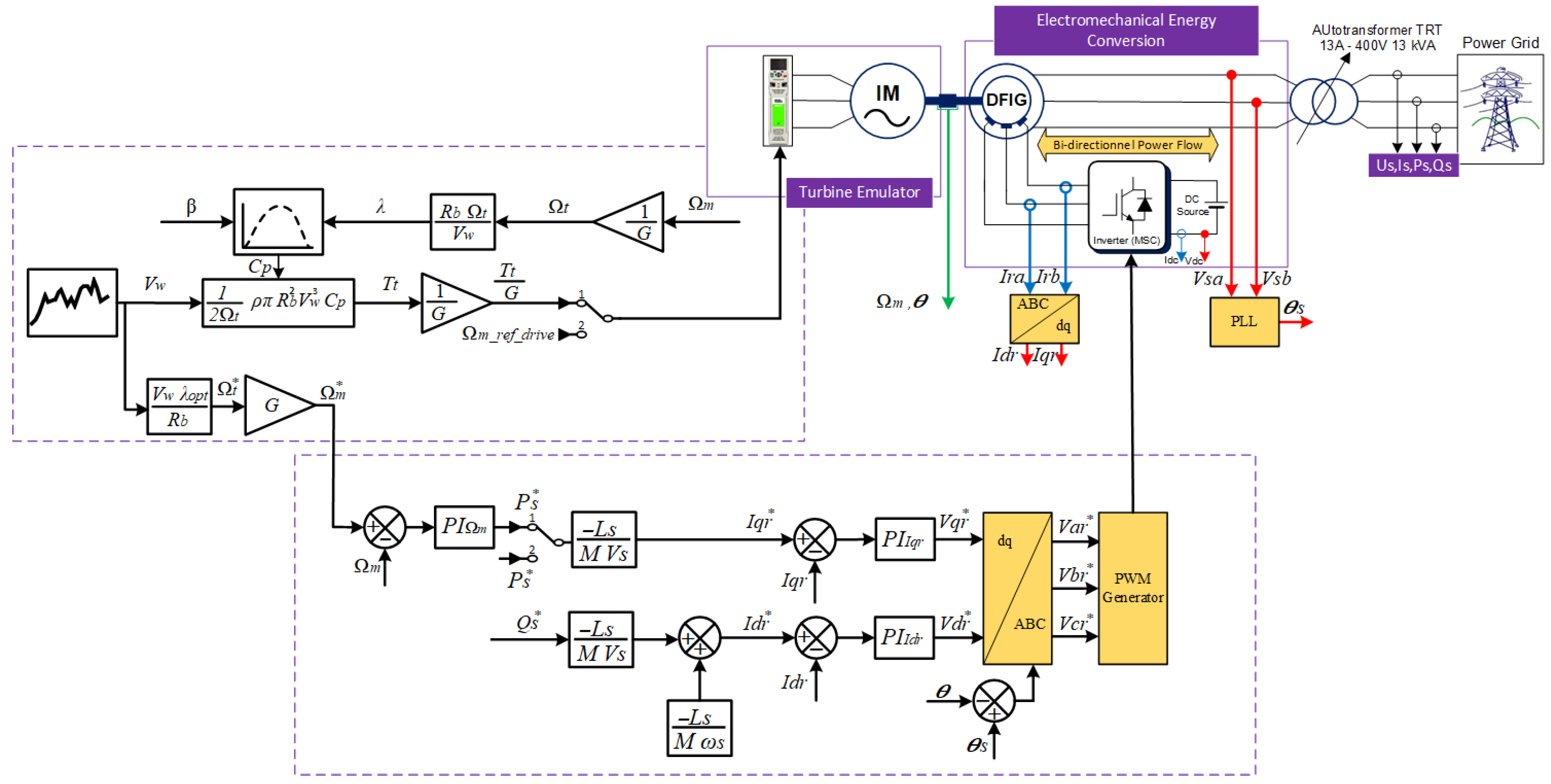

2. Wind Turbine Emulator System Overview

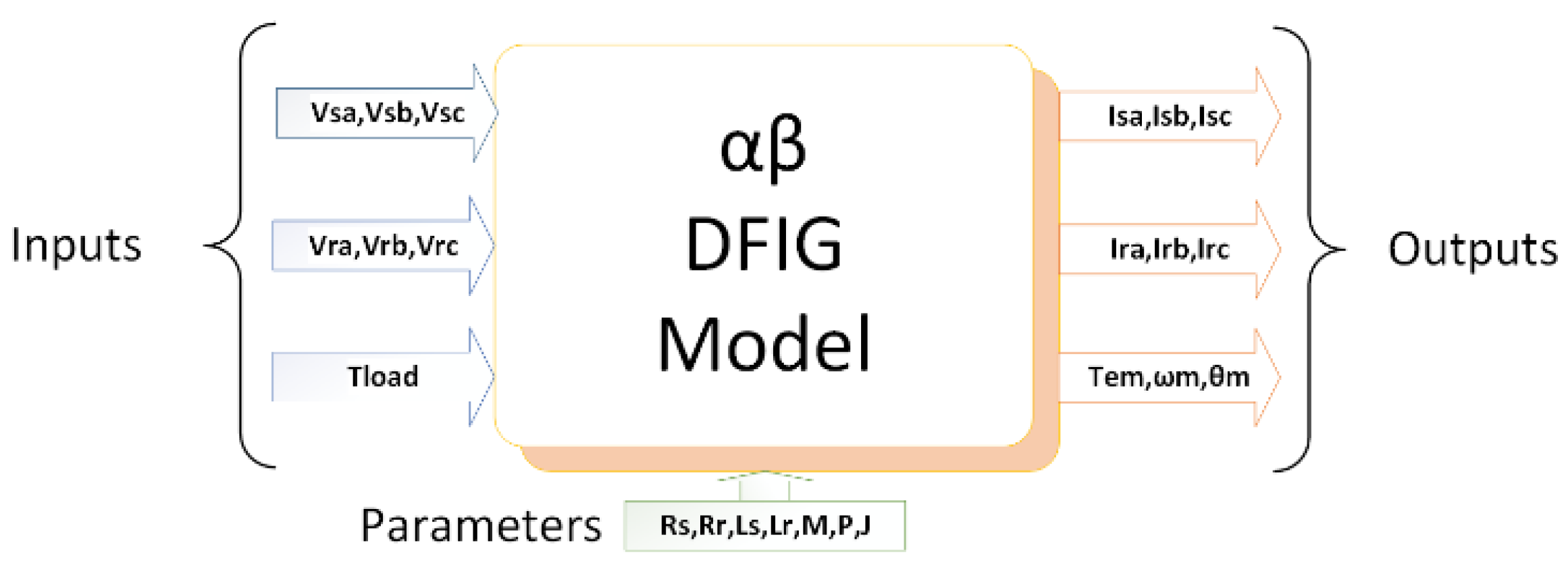

3. Modeling of the DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator

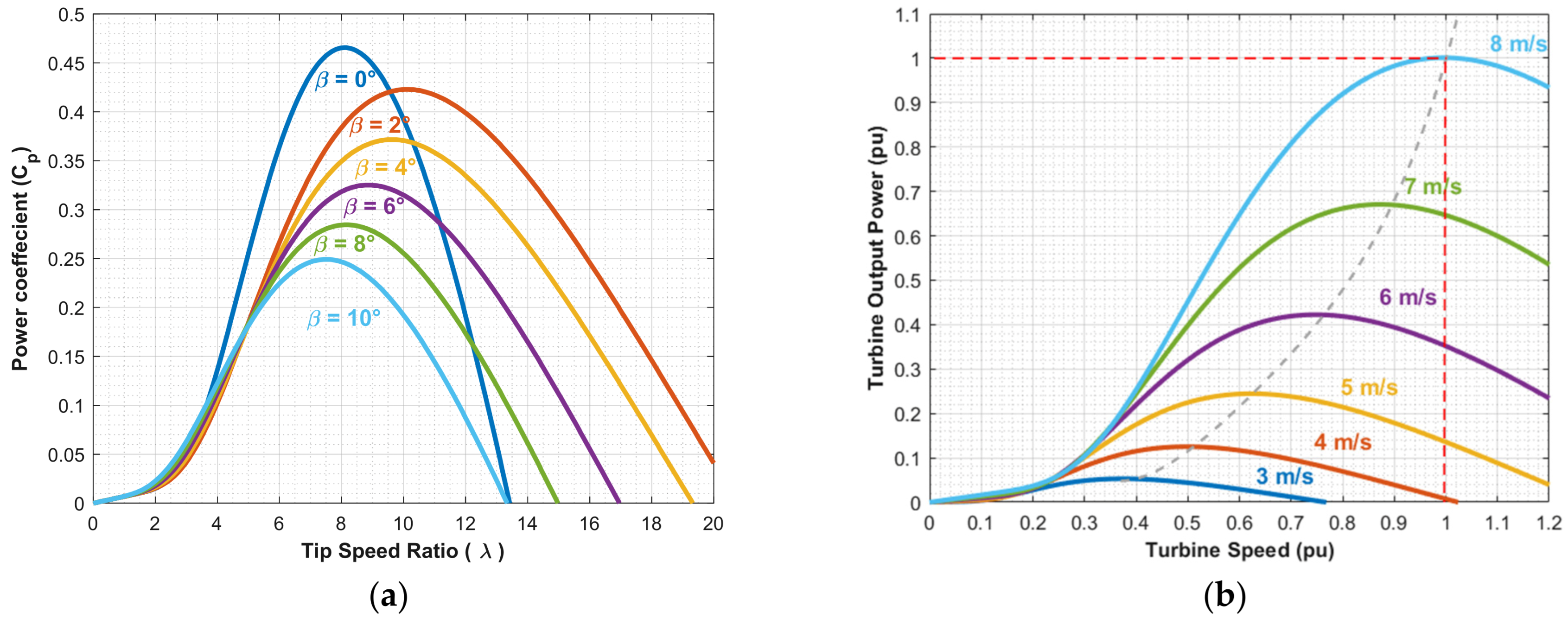

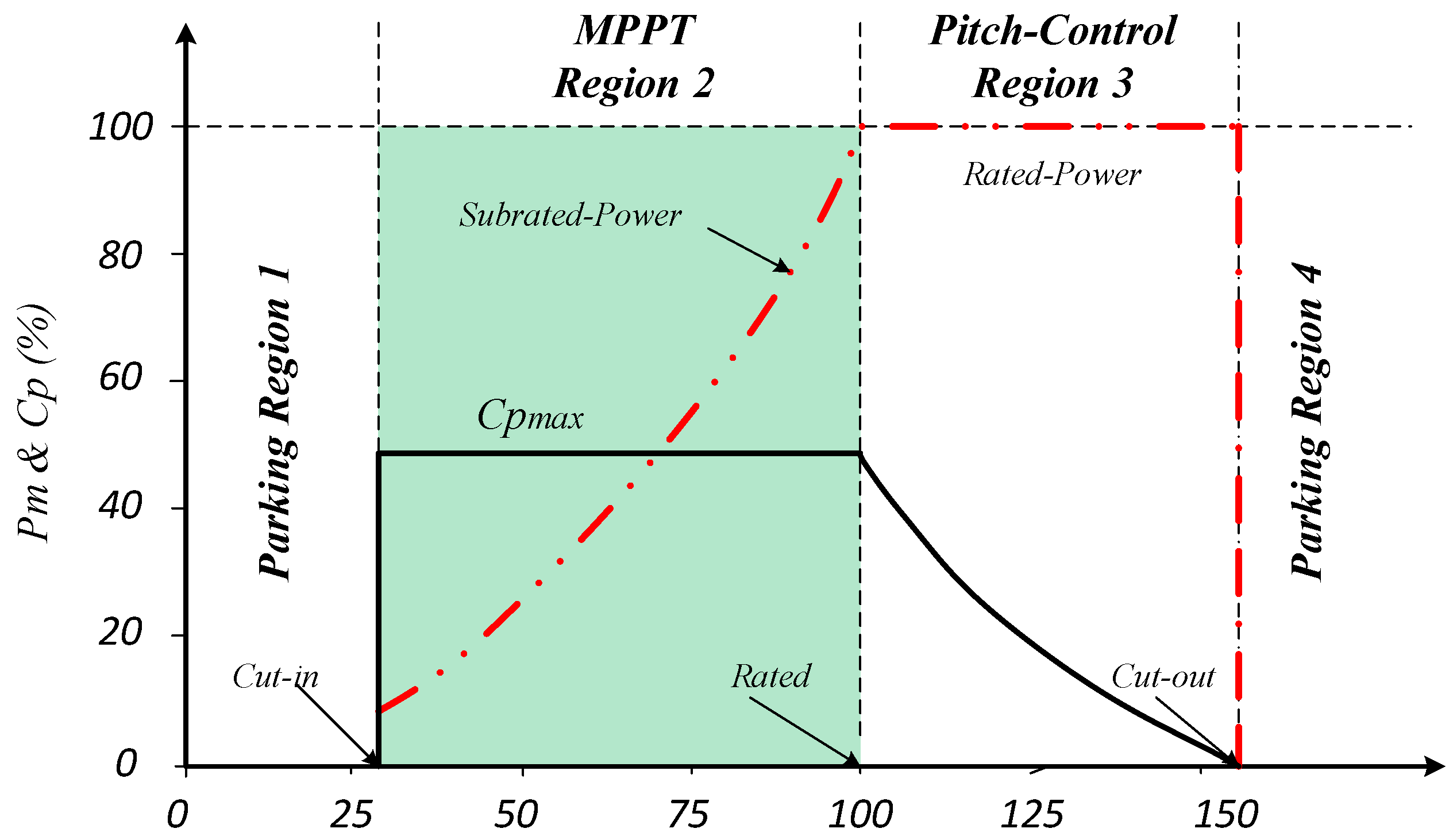

3.1. Wind Turbine Model

3.2. Dynamic Modeling of the DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator

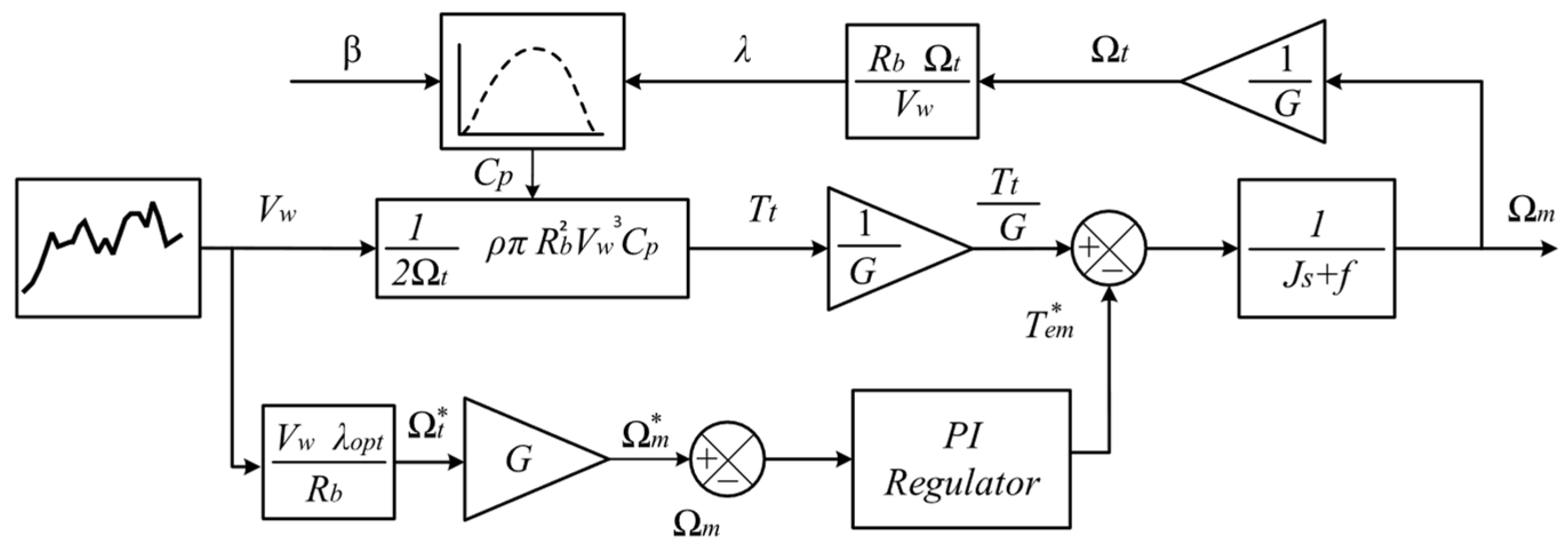

4. Control System of the Wind Turbine Emulator

4.1. TSR-Based MPPT Wind Turbine Control

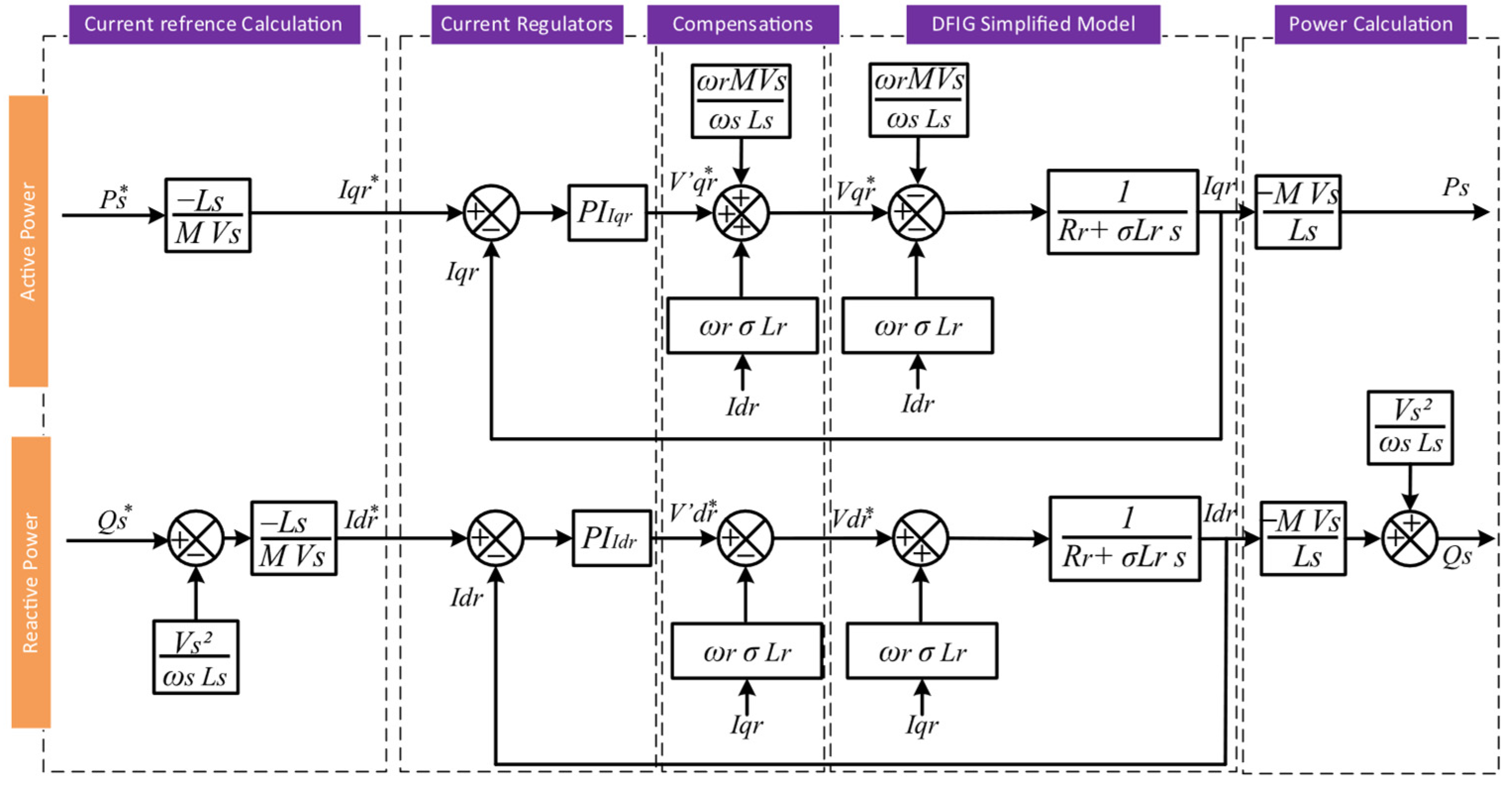

4.2. DFIG Control

5. Experimental Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennia, I.; Daili, Y.; Harrag, A.; Alrajhi, H.; Saim, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Stability and Reactive Power Sharing Enhancement in Islanded Microgrid via Small-Signal Modeling and Optimal Virtual Impedance Control. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2024, 2024, 5469868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, W.; Sharkh, S.; Abusara, M. A review of recent control techniques of drooped inverter-based AC microgrids. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1792–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, M.K.; Al Zaabi, O.; Al Hosani, K.; Al Jaafari, K.; Pradhan, C.; Muduli, U.R. Advancing electric vehicle charging ecosystems with intelligent control of DC microgrid stability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 12, 1792–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennia, I.; Harrag, A.; Dailia, Y. Small-signal modelling and stability analysis of island mode microgrid paralleled inverters. J. Renew. Energ. 2021, 24, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennia, I.; Elbouchikhi, E.; Harrag, A.; Daili, Y.; Saim, A.; Bouzid, A.E.M.; Kanouni, B. Design, modeling, and validation of grid-forming inverters for frequency synchronization and restoration. Energies 2023, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, Z.; Kengne, K.; Bhat, O. A comprehensive review on wind turbine emulators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 180, 113297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouheyr, D.; Lotfi, B.; Abdelmadjid, B. Real-Time Emulation of a Grid-Connected Wind Energy Conversion System Based Double Fed Induction Generator Configuration under Random Operating Modes. Eur. J. Electr. Eng. Int. Génie Electr. 2021, 23, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.M. A nonlinear maximum power point tracking technique for DFIG-based wind energy conversion systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2018, 21, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouari, K.; Belkhier, Y. Model predictive direct torque algorithm for coordinated electrical grid operation of wind energy conversion system-based doubly fed induction generator. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, M.K.; Pradhan, C.; Nayak, P.K.; Padmanaban, S.; Gjengedal, T. Modified demagnetisation control strategy for low-voltage ride-through enhancement in DFIG-based wind systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 3487–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Diaz, M.; Devi, V.; Jena, D.; Travieso, J.; Rodriguez, J. Wind Turbine Emulators—A Review. Processes 2023, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennia, I.; Daili, Y.; Harrag, A. Hierarchical control of paralleled voltage source inverters in islanded single phase microgrids. In Artificial Intelligence and Renewables Towards an Energy Transition 4; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.C.; Amenedo, J.L.R.; Gómez, S.A.; Alonso-Martínez, J. Grid-forming control of doubly-fed induction generators based on the rotor flux orientation. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekali, Z.; Baghli, L.; Lubin, T.; Boumediene, A. Grid side inverter control for a grid connected synchronous generator based wind turbine experimental emulator. Eur. J. Electr. Eng. 2021, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, M.K.; Pradhan, C.; Nayak, P.K.; Samantaray, S.R. Lagrange interpolating polynomial–based deloading control scheme for variable speed wind turbines. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2019, 29, e2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amenedo, J.L.; Gomez, S.A.; Martinez, J.C.; Alonso-Martinez, J. Black-Start Capability of DFIG Wind Turbines Through a Grid-Forming Control Based on the Rotor Flux Orientation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 142910–142924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollz, D.H.; Da Silva, S.A.O.; Sampaio, L.P. Real-time monitoring of an electronic wind turbine emulator based on the dynamic PMSG model using a graphical interface. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Zhou, L.; Xiong, L.; Liu, J.; Li, P. A fixed-time fractional-order sliding mode control strategy for power quality enhancement of PMSG wind turbine. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 134, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xiong, L.; Ma, M.; Huang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z. Energy-shaping L2-gain controller for PMSG wind turbine to mitigate subsynchronous interaction. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 135, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Aragon, D.A.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Inertia emulation control of PMSG-based wind turbines for enhanced grid stability in low inertia power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.H.H.; Youssef, A.-R.; Mohamed, E.E.M. State of the art perturb and observe MPPT algorithms based wind energy conversion systems: A technology review. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 126, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouheyr, D.; Lotfi, B.; Abdelmadjid, B. Improved hardware implementation of a TSR based MPPT algorithm for a low cost connected wind turbine emulator under unbalanced wind speeds. Energy 2021, 232, 121039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Chatterjee, K. A review of conventional and advanced MPPT algorithms for wind energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, A.; Krstić, M.; Seshagiri, S. Power optimization and control in wind energy conversion systems using extremum seeking. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2014, 22, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveiros, F.E.V.; Barros, L.S.; Costa, F.B. Back-to-back converter state-feedback control of DFIG (doubly-fed induction generator)-based wind turbines. Energy 2015, 89, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahfaoui, B.; Zouggar, S.; Mohammed, B.; Elhafyani, M.L. Real time study of P&O MPPT control for small wind PMSG turbine systems using Arduino microcontroller. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Shan, M.; Liu, L.; Guerrero, J.M. A novel improved variable step-size incremental-resistance MPPT method for PV systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 58, 2427–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Yatim, A.H.M.; Tan, C.W.; Saidur, R. A review of maximum power point tracking algorithms for wind energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3220–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennia, I.; Harrag, A.; Daili, Y.; Bouzid, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Decentralized secondary control for frequency regulation based on fuzzy logic control in islanded microgrid. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2023, 29, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.; Herrero, L.C.; de Pablo, S. Open loop wind turbine emulator. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mokadem, M.; Courtecuisse, V.; Saudemont, C.; Robyns, B.; Deuse, J. Experimental study of variable speed wind generator contribution to primary frequency control. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, H.; Dahiya, R. Modelling and Development of Wind Turbine Emulator for the Condition Monitoring of Wind Turbine. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2015, 5, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, J.; Espí, J.M.; García-Gil, R. Development details and performance assessment of a wind turbine emulator. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.; Narayanan, G. Emulation of wind turbine system using vector controlled induction motor drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 4124–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, M.; Fernandez-Ramirez, L.M.; Kamal, T.; Kamal, S. A new hill climbing maximum power tracking control for wind turbines with inertial effect compensation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 8545–8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Fadaeinedjad, R.; Moschopoulos, G. An electromechanical emulation-based study on the behaviour of wind energy conversion systems during short circuit faults. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.R.; De Souza, W.G.; Rocha, M.A.; da Costa, C.F.; Leão, J.V.F.; Andreoli, A.L. Wind turbine emulator using induction motor driven by frequency inverter and hardware-in-the-loop control. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON), Sao Paulo, Brazil, 12–14 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, C.; Bratcu, A.I.; Munteanu, I.; Epure, S. Real-time replication of a stand-alone wind energy conversion system: Error analysis. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 55, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Hu, K.-W.; Lin, Y.-G.; Liaw, C.-M. Development of a prime mover emulator using a permanent-magnsynchronous motor drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 6114–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghli, L.; Jamshidpour, E. Implementing a 200 kHz PWM Field Oriented Control using RTLib and C program on a dSPACE MicroLabBox. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Advanced Electrical Engineering (ICAEE), Constantine, Algeria, 29–31 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, G.; Lopez Taberna, J.; Rodriguez, M.; Marroyo, L.; Iwanski, G. Doubly Fed Induction Machine: Modeling and Control for Wind Energy Generation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouheyr, D. Contribution à la Commande d’un Simulateur HIL d’Éolienne et d’une Génératrice Asynchrone à Double Alimentation. Ph.D. Thesis, Abou Bekr Belkaid University, Tlemcen, Algérie, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmine, I.; Chakib, E.B.; Badre, B. Power control of DFIG-generators for wind turbines variable-speed. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. IJPEDS 2017, 8, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFIG Parameters (Rated Power 3 kw) | |||

| fs | Switching frequency | 10 | kHz |

| P | Pairs of poles | 2 | - |

| Rs | Stator resistance | 2.3 | Ω |

| Rr | Rotor resistance | 0.26 | Ω |

| Ls | Stator inductance | 0.128 | H |

| Lr | Rotor inductance | 0.029 | H |

| M | Mutual inductance | 0.0577 | H |

| J | Inertia | 0.1525 | kg·m2 |

| F | Friction factor | 0.0055 | N·m·s |

| U1/U2 | Transformation ratio | 0.23 | - |

| Wind Turbine Emulator Parameters (Rated Power 3 kw) | |||

| Rb | Blade radius | 3 | meter |

| Air density | 1.225 | kg/m3 | |

| G | Gearbox coefficient | 8 | - |

| β | Blade pitch angle | 2° | Degree |

| Control Parameters | |||

| Kp_I | Current proportional gain | 4.7 | - |

| Ki_I | Current integral gain | 0.8 | - |

| Kp_PLL | PLL proportional gain | 0.5 | - |

| Ki_PLL | PLL integral gain | 0.03 | - |

| Kp_Ω | Speed proportional gain | 45 | - |

| Ki_ Ω | Speed integral gain | 4 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bennia, I.; Baghli, L.; Pierfederici, S.; Mechernene, A. Implementation and Performance Assessment of a DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator Using TSR-Driven MPPT for Enhanced Power Extraction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412966

Bennia I, Baghli L, Pierfederici S, Mechernene A. Implementation and Performance Assessment of a DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator Using TSR-Driven MPPT for Enhanced Power Extraction. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412966

Chicago/Turabian StyleBennia, Ilyas, Lotfi Baghli, Serge Pierfederici, and Abdelkader Mechernene. 2025. "Implementation and Performance Assessment of a DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator Using TSR-Driven MPPT for Enhanced Power Extraction" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412966

APA StyleBennia, I., Baghli, L., Pierfederici, S., & Mechernene, A. (2025). Implementation and Performance Assessment of a DFIG-Based Wind Turbine Emulator Using TSR-Driven MPPT for Enhanced Power Extraction. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412966