Abstract

Skin diseases are common conditions that pose a significant threat to human health, and automated classification plays an important role in assisting clinical diagnosis. However, existing image classification approaches based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Transformers have inherent limitations. CNNs are constrained in capturing global features, whereas Transformers are less effective in modeling local details. Given the characteristics of dermoscopic images, both local and global features are equally crucial for classification tasks. To address this issue, we propose an improved Swin Transformer-based model, termed MaLafFormer, which incorporates a Modulated Fusion of Multi-scale Attention (MFMA) module and a Lesion-Area Focus (LAF) module to enhance global modeling, emphasize critical local regions, and improve lesion boundary perception. Experimental results on the ISIC2018 dataset show that MaLafFormer achieves 84.35% ± 0.56% accuracy (mean of three runs), outperforming the baseline 77.98% ± 0.34% by 6.37%, and surpasses other compared methods across multiple metrics, thereby validating its effectiveness for skin lesion classification tasks.

1. Introduction

The skin is the largest organ of the human body [1], maintaining continuous contact with the external environment and serving as the first barrier against exogenous threats. Skin lesions indicate a compromise of this barrier and can be broadly categorized into benign and malignant types. Malignant skin lesions may be life-threatening, while benign lesions increase susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections, potentially leading to other diseases. Regardless of the type, skin lesions warrant serious attention. Therefore, accurate identification of the lesion type is crucial, as it serves as a prerequisite for subsequent treatment [2]. Traditionally, the diagnosis of skin lesion types has primarily relied on physicians’ medical expertise and clinical experience [3]. However, this approach is subject to individual variability, as different physicians may arrive at divergent diagnostic conclusions, which can in turn affect the formulation of treatment plans. To reduce excessive dependence on personal experience and improve diagnostic efficiency, image classification techniques have been increasingly introduced into the medical domain. Image classification leverages computer algorithms to extract features from images and categorize them based on these features.

In the early stages, the classification of medical images, such as skin lesions, relied on traditional computer vision techniques and manual feature extraction, primarily involving shape, texture, color, and combined descriptors [4,5]. These features were then classified using classifiers such as support vector machines (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (K-NN), or random forests. However, the representational capacity of such handcrafted features is limited, making it challenging to accommodate the complex and diverse morphologies of skin lesions. Over the past decade, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [6] have steadily established themselves as the prevailing paradigm in image classification and have found broad utility across medical image analysis tasks, including skin lesion classification [7]. For example, VGGNet [8] enhances the feature representation capability of the model by increasing network depth and has demonstrated outstanding performance in skin lesion classification tasks [9]. The key design of VGGNet lies in its hierarchical structure, in which the network is divided into five modules, each consisting of a sequence of convolutional layers. The modules are interconnected via 2 × 2 max-pooling layers, which are succeeded by three fully connected stages and a final softmax unit for the prediction. All hidden layers employ the ReLU activation function. The MobileNet architecture was proposed to address the challenge of deploying deep learning models in resource-constrained environments, leading to the development of MobileNetV1 [10], MobileNetV2 [11], and MobileNetV3 [12]. Building upon MobileNetV2, MobileNetV3 introduces several improvements, including the adoption of hard activation functions to reduce computational demands and the incorporation of a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module to enable automatic learning of feature weights, thereby enhancing the model’s focus on salient regions. This design allows MobileNetV3 to retain the advantages of a lightweight architecture while exhibiting greater attention to lesion areas on the skin [13].

Although CNNs exhibit strong capabilities in capturing local features, their convolutional kernels inherently limit the ability to model global information. With the advent of Vision Transformers (ViTs) [14], the Transformer [15] architecture has been introduced into the field of computer vision, demonstrating outstanding performance in capturing global contextual relationships and gradually emerging as an alternative to CNNs. Consequently, various Transformer-based approaches for skin lesion classification have been proposed by researchers. Wang et al. [16] divided the melanoma classification task into two stages. In the first stage, melanoma images generated by a generative adversarial network (GAN) were used to augment the original dataset, and in the second stage, image feature extraction and skin lesion detection were performed within the BatchFormer [17] framework. Manzari et al. [18] proposed embedding a Kolmogorov–Arnold Network into the Transformer feed-forward path to replace the traditional multilayer perceptron (MLP), thereby enabling high-order global mappings. In addition, an enhanced Dilated Neighborhood Attention (DiNA) mechanism was employed to capture global contextual information. A hierarchical hybrid strategy was adopted to alternately stack these components, aiming to jointly extract local and global features. Finally, a linear classifier was used to predict the categories of skin lesions. Reis and Turk [19] proposed a method named MABSCNET, which combines the strengths of CNNs and Transformers. Depthwise separable convolutions were used as the fundamental building blocks and integrated with a multi-head attention mechanism to extract both local and global features, achieving high accuracy in skin cancer classification tasks.

However, existing classification approaches generally exhibit two limitations. First, they lack effective fusion of multi-scale information and cross-layer feature interaction modeling, which constrains the models’ ability to fully leverage multi-level semantic information [20]. Second, skin lesion images often contain prominent boundary information, and during diagnosis, only the lesion regions are of interest while normal areas are irrelevant. Existing methods, however, insufficiently focus on modeling lesion boundaries, resulting in limited precision in localizing the affected regions [21].

A novel Swin Transformer-based model, termed MaLafFormer, is proposed herein to mitigate the aforementioned issues in skin lesion classification. While maintaining the ability to model global features, the model introduces a Modulated Fusion of Multi-scale Attention (MFMA) module to enhance multi-scale contextual modeling, and a Lesion-Area Focus (LAF) module to strengthen the perception of local details and boundary information. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We propose MaLafFormer, a Swin Transformer-based model that further enhances the ability to capture global information while simultaneously capturing local features and focusing on lesion regions, enabling efficient feature encoding and precise classification.

- We design the Modulated Fusion of Multi-scale Attention (MFMA) module. By integrating cross-layer fusion with multi-scale attention mechanisms, the module strengthens the model’s ability to model cross-scale context, which is particularly critical for capturing global information.

- We introduce the Lesion-Area Focus (LAF) module, which employs grouped channel attention and spatial attention for fine-grained local modeling of feature maps. This module focuses on lesion regions while suppressing irrelevant areas, thereby improving the model’s sensitivity to texture, boundaries, and other local details.

This paper is organized into five sections. Section 2 reviews previous related work; Section 3 presents the proposed method; Section 4 details the experimental results and analysis of the proposed model on the ISIC2018 dataset; finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and presents potential avenues for future research.

2. Related Works

The advent of Convolutional Neural Networks has propelled rapid advancements and established dominance in the field of image classification. Rasti et al. [22] proposed a ME-CNN model based on CNNs and a gated network for classifying breast tumors as benign or malignant. Yang et al. [23] selected two stages of CNNs via Deep Tree Training (DTT) to form an optimal classifier, achieving favorable classification results on both breast histopathological images and chest X-ray images. Furthermore, CNNs have been extensively applied to the classification and detection of various medical conditions, including, for instance, liver masses classification [24], skin cancer classification [25,26] abnormality detection in chest radiographs [27], glaucoma diagnosis [28], left ventricular hypertrophy classification [29], and pulmonary embolism diagnosis [30].

The Transformer architecture was initially applied in natural language processing (NLP) [31,32,33,34]. Subsequently, Dosovitskiy et al. [14] pioneered the Vision Transformer (ViTs), which implemented this architecture purely in computer vision. By capturing global contextual relationships through self-attention mechanisms, ViTs addresses the limitations of CNNs in modeling long-range dependencies, thereby establishing itself as a competitive alternative. Consequently, ViTs has demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse computer vision tasks, including image classification [35,36,37], image enhancement [38,39,40], and image generation [41,42,43,44]. In the field of medical imaging, ViTs have been successfully applied to various disease detection and classification tasks. For instance, Xin et al. [45] employed ViTs as a backbone network, utilizing multi-scale and overlapping sliding windows for feature extraction and contrastive learning to differentiate encoded representations from different data. Their approach demonstrated effectiveness in skin cancer classification. Mohamed et al. [46] leveraged a Cross Vision Transformer to capture image features and enhanced the Nutcracker Optimizer (NO) efficiency via Chaotic Game Optimization (CGO), achieving promising results in breast cancer classification. Wang et al. [47] proposed RanMerFormer for brain tumor classification, introducing a token merging mechanism atop ViTs to eliminate redundant tokens. This method not only improved computational efficiency but also attained competitive accuracy in brain tumor classification.

However, ViTs often suffer from overlooking local features. To address this limitation, Liu et al. [48] proposed Swin Transformer, which employs a shifted window attention mechanism to enable interactions between local regions, thereby effectively capturing local feature representations. Li et al. [49] introduced UniFormer, achieved by merging the local inductive bias inherent in CNNs with the long-range modeling capabilities of ViTs. This architecture captures local features through convolution-like operations in shallow layers and models global dependencies in deeper layers. Furthermore, numerous ViT variants incorporating local inductive bias have been developed, including DeiT [50], T2T-ViT [51], and MobileVit [52]. Architectures combining such localized feature extraction with global semantic modeling capabilities have been extensively adopted in medical image classification, demonstrating significant performance gains. Chen et al. [53] proposed a multi-scale vision Transformer model named GasHis-Transformer, which combines the strengths of conventional CNNs and the Transformer architecture to enable the extraction of both global and local features, achieving favorable results on classification tasks involving gastric cancer histopathology, breast cancer, and lymphoma datasets. Horst et al. [54] developed the CellViT model, in which the encoder employs a ViT and the decoder retains a U-Net-like structure, thereby balancing global context modeling with the preservation of local details, and achieving superior performance over conventional Transformers and pure CNN architectures in cell nuclei detection and classification. Manigrasso et al. [55] proposed a novel approach that integrates a graph convolutional network with a multi-view vision Transformer, trained in a weakly supervised setting on a breast cancer classification dataset, demonstrating both the effectiveness of Transformers in multi-view fusion and the necessity of complementarity across architectures.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

MaLafFormer is a novel approach for skin lesion image classification that simultaneously enhances global semantic understanding and local detail perception. Based on the Swin Transformer, MaLafFormer incorporates a cross-layer multi-scale information modeling mechanism and improved local feature perception capabilities. Through cross-layer feature fusion, the model strengthens its ability to capture global representations, while its sensitivity to texture, boundary, and other fine-grained details enables more focused attention on critical regions. This section commences with an introduction to the full architecture of the MaLafFormer model, followed by a detailed description of the SMFMA and LAF modules, and finally outline the evaluation metrics employed in the subsequent experiments.

3.2. MaLafFormer Overall Architecture

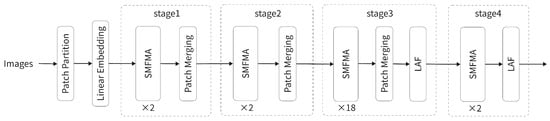

The overall architecture of MaLafFormer is illustrated in Figure 1, consisting of four stages that contain 2, 2, 18, and 2 SMFMA modules, respectively, with the LAF module additionally incorporated in Stages 3 and 4. The input RGB image is first processed by the Patch Embedding module, where it is divided into non-overlapping 4 × 4 patches. These patches are flattened and mapped to a 128-dimensional feature space through a linear embedding layer, generating a patch token sequence with a spatial resolution of H/4 × W/4. The features are then sequentially fed into the four stages, within each of which multiple SMFMA modules are stacked to perform feature modeling via local window attention, followed by multi-scale fusion and attention enhancement. Between consecutive stages, Patch Merging is applied to perform downsampling, progressively halving the spatial resolution and doubling the channel dimension. From Stage 1 to Stage 4, the spatial resolutions evolve as H/4 × W/4, H/8 × W/8, H/16 × W/16, and H/32 × W/32, while the corresponding channel dimensions increase as 128, 256, 512, and 1024. This process ensures that the model compresses spatial redundancy while preserving the depth of the semantic hierarchy, thereby obtaining more abstract image representations. To enhance the local modeling capability of features in the middle and later stages, the LAF module is added after the Patch Merging operations in Stages 3 and 4. It provides dynamic guidance to the feature maps in both the channel and spatial dimensions, which strengthens the model’s ability to perceive local edges and to represent fine-grained details. Finally, the high-level features extracted from all stages are normalized and passed through a global average pooling layer, followed by a fully connected classification head that produces the final classification output.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of MaLafFormer.

3.3. SMFMA Module

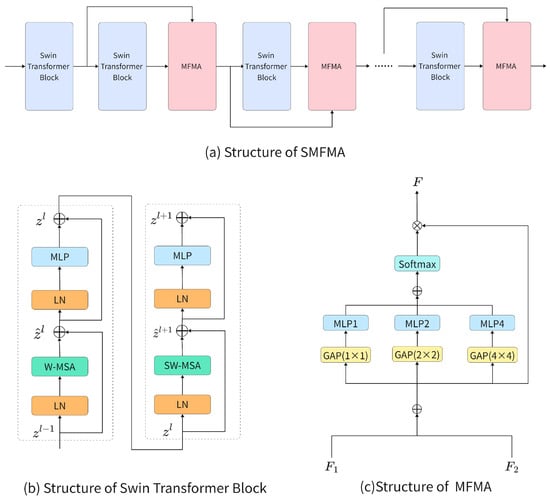

The SMFMA module consists of Swin Transformer Blocks and MFMA modules, and its structure is illustrated in Figure 2a. Starting from the second Swin Transformer Block, after each block, the output of the previous Swin Transformer Block and the output of the current Swin Transformer Block or MFMA module are used together as the input to the next MFMA module for cross-layer feature fusion.

Figure 2.

SMAMA, Swin Transformer Block, and MFMA structure.

The Swin Transformer Block was first introduced in Swin Transformer [48], and its configuration is illustrated in Figure 2b. The Layer Normalization (LN) module standardizes the input features, which serves to stabilize training and ensure comparable feature scales across various dimensions. Furthermore, the Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (W-MSA) calculates self-attention independently within each local window, thereby facilitating the model’s acquisition of correlation information among features in different regions. The Shifted Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (SW-MSA) shifts the window partitions to allow information exchange between adjacent windows, thereby achieving cross-window modeling. Each attention module is followed by a MLP layer, which consists of two fully connected layers and a GELU activation, enabling complex nonlinear transformations for higher-level feature extraction. In addition, residual connections are employed within the block to enhance information flow and mitigate gradient vanishing. Through these operations, feature modeling within windows is effectively achieved.

Although the Swin Transformer Block can achieve efficient local modeling through its fixed-window mechanism, it has limited capability in capturing cross-layer and multi-scale contextual information. To address this limitation, the MFMA module enhances the network’s capacity to capture features from different layers and scales through cross-layer feature fusion and multi-scale attention weighting. The structure of this module is depicted in Figure 2c. Specifically, the MFMA takes as input the output features and from two adjacent Swin Transformer Blocks, both with shape [B, C, H, W]. The two feature maps are first concatenated along the channel dimension to form a fused feature of shape [B, 2C, H, W], which is then rearranged into the shape [B, 2, C, H, W]. By summing along the feature-map dimension (dim = 1), the fused feature with shape [B, C, H, W] is obtained. To construct multi-scale contextual representations, is processed in parallel using adaptive average pooling at three scales (1×, 1/2×, 1/4×), corresponding to receptive fields of 1 × 1, 2 × 2, and 4 × 4, respectively. The features at each scale are passed through corresponding MLPs to generate attention maps , , and , which are then upsampled to the original spatial resolution and summed to produce a fused attention map. The fused attention map is normalized using Softmax along the feature-map dimension (dim = 1), yielding the fusion weights A with shape [B, 2, C, 1, 1]. The fused attention map is normalized along the height dimension using Softmax to obtain the fusion weights A. Finally, the fusion attention weights A are multiplied with the fused feature to produce the output feature:

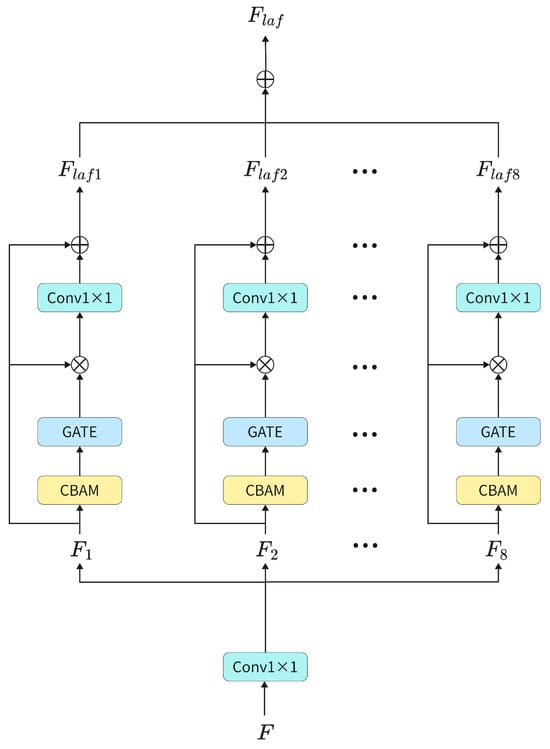

3.4. LAF Module

After multiple SMFMA modules and Patch Merging operations, deep features of the image can be extracted; however, the network lacks selective suppression of spatially redundant regions, which may introduce background noise. To address this issue, the LAF module is introduced to guide the network to focus on the target regions. It enhances the model’s ability to perceive lesion boundaries and to extract local key features by applying a grouped version of the CBAM module [56]. In addition, a gating mechanism is incorporated to further assign weights, highlighting features in the target regions while reducing the network’s attention to irrelevant areas.

The structure of the LAF module is depicted in Figure 3. The output feature F from the SMFMA module is initially subjected to a convolution to regulate the number of input channels. It is then partitioned into eight groups, specifically , along the channel dimension. Each of these feature groups is subsequently inputted into a CBAM module to determine the local attention weight, expressed as

Here, denotes the CBAM weight for the i-th group of features , with values ranging from 0 to 1, where higher weights indicate more important feature information. To emphasize the lesion regions in skin lesion images, a gating mechanism is applied to adjust . Elements with values greater than the mean are set to 1, while the remaining elements retain their original values. The adjusted weight map is then multiplied with , and the result is passed through a 1 × 1 convolution to restore the channel dimension:

In addition, we introduce learnable residual scaling. The output of the module is added to its input through a residual connection, and a learnable scaling factor is applied to dynamically adjust the contribution of the residual branch, ensuring training stability and smooth gradient flow

Here, denotes the learnable scaling factor. Finally, the features are concatenated along the channel dimension to obtain the enhanced output feature .

Figure 3.

Structure of LAF.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

For the assessment of the proposed model’s classification performance pertaining to skin lesion images, a set of overall classification metrics was chosen, specifically encompassing accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1 score. Accuracy is computed in a micro-averaged manner to reflect overall diagnostic efficacy, while the precision, recall, and F1 are macro-averaged across classes to ensure equal contribution from each lesion type. Additionally, to evaluate the model’s discriminative ability for each individual category, we compute separate confusion matrices for every class and report the precision, recall, F1, specificity, and ROC-AUC metrics.

Among these metrics, the AUC is derived from the one-vs-rest ROC curves. The remaining metrics are calculated based on the confusion matrix, where a correct prediction of a positive sample is a true positive (TP), a correct prediction of a negative sample is a true negative (TN), an incorrect prediction of a negative sample as positive is a false positive (FP), and an incorrect prediction of a positive sample as negative is a false negative (FN). Accuracy refers to the proportion of samples correctly predicted by the model out of the total number of samples, reflecting the overall classification performance of the model. The calculation formula is as follows:

Precision refers to the proportion of samples predicted as positive that are actually positive. The higher the value, the stronger the model’s ability to distinguish negative samples, reflecting the model’s ability to distinguish negative samples. The calculation formula is:

The recall rate indicates the proportion of samples that are correctly identified as positive. The higher the value, the stronger the model’s ability to identify positive samples, reflecting the model’s ability to identify positive samples. The calculation formula is:

The F1 score is a weighted average of precision and recall. The higher the value, the more robust the model is. The formula is:

Specificity measures the proportion of samples not belonging to the target class that are correctly identified as negative. A higher value indicates a better ability of the model to exclude false positives for that class.The formula is:

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Dataset

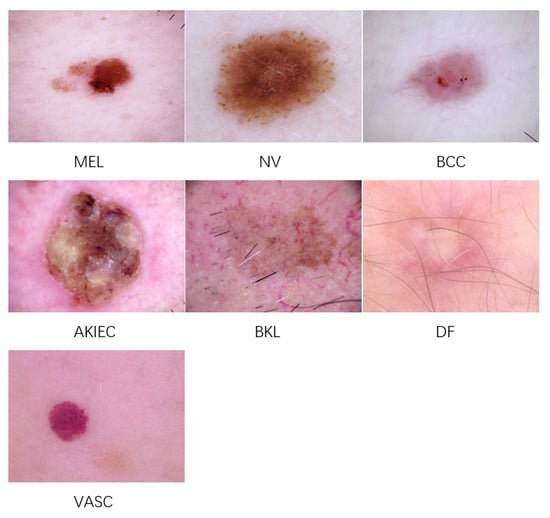

In our experiments on skin lesion image classification, we employed the ISIC 2018 dataset [57], specifically Task 3—skin lesion classification. This dataset was collaboratively developed by dermatology experts worldwide, comprising a large collection of annotated skin lesion images. It contains 11,720 high-resolution images categorized into seven classes: vascular skin lesions (VASC), melanocytic nevi (NV), dermatofibroma (DF), benign keratosis (BKL), melanoma (MEL), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and actinic keratosis (AKIEC). Representative images from these seven categories are displayed in Figure 4. All images in the dataset have a resolution of 600 × 450 pixels, which were resized to 224 × 224 pixels for our experiments.

Figure 4.

Representative images of each skin lesion class.

The dataset was split into 8715 images for training, 1493 for validation, and 1512 for testing. Table 1 delineates the data partitioning scheme and the corresponding class distribution. As evidenced in Table 1, the ISIC2018 manifests severe class imbalance across all partitions, with this challenge being particularly pronounced in the training set. Among the training samples, the NV category constitutes the majority, accounting for approximately 67% of the total samples. In contrast, the DF, VASC, and AKIEC categories collectively represent less than 6% of the training data. MEL, being the clinically most critical malignant category, comprises 11% of the training samples yet remains outnumbered by NV samples by nearly a 6:1 ratio. This extreme class imbalance predisposes the model to exhibit bias toward majority classes during training, consequently compromising its recognition capability for minority classes. This substantial data challenge constitutes the primary motivation for our research.

Table 1.

The detailed distribution of samples across the 7 classes of the ISIC 2018 dataset.

4.2. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on a GeForce RTX 4090D GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 24 GB of memory, and the models were implemented using the PyTorch 1.10.0 framework. Regarding weight initialization, we initialized the Swin-B backbone by loading pre-trained weights from the ImageNet-22k dataset, while for the newly added modules, we adopted PyTorch’s default Kaiming Normal Initialization method. After multiple rounds of manual hyperparameter tuning on the validation set, we determined a stable and optimal parameter configuration. During training, AdamW was adopted as the optimizer for the proposed MaLafFormer model. The training was performed for 100 epochs with a batch size of 32, an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, a minimum learning rate of 1 × 10−6, and a weight decay coefficient of 1 × 10−4. The first five epochs were set as a warm-up phase, followed by a cosine decay strategy to automatically adjust the learning rate. The detailed parameter settings are presented in Table 2. To enhance the generalization capability of the model, we applied data augmentation to the training images, including random cropping to 224 × 224 pixels, as well as random horizontal flipping (probability: 0.4), random vertical flipping (probability: 0.3), and random rotation with an angle range of ±15° (probability: 0.6).

Table 2.

Experimental parameters.

During training, we employed an Early Stopping strategy for all models. Specifically, after the completion of each training epoch, we calculated the loss value on the validation set and saved the model checkpoint that exhibited the minimum validation loss. All results reported in this paper are derived from the checkpoint that achieved the minimum loss on the validation set. This method of selecting the best checkpoint based on validation set performance ensures that the reported results reflect the model’s optimal generalization ability on unseen data, thereby safeguarding the impartiality of the experimental findings.

4.3. Ablation Study

The MFMA and LAF modules are the two key components of the proposed model. To validate their effectiveness, ablation studies were executed on the ISIC2018 dataset for the skin lesion classification task, thereby allowing for the assessment of each component’s impact on the final performance metrics. Our baseline is Swin-B and all experiments used the parameter configuration described in Section 4.2. To verify robustness, we repeated every method three times with seeds 42, 217 and 3407. All metrics in Table 3 are reported as average ± standard across these three runs.

Table 3.

Overall performance of ablation experiment on ISIC2018.

As shown in Table 3, incorporating the MFMA and LAF modules improved the model’s classification accuracy by 4.41% and 5.20%, respectively. Specifically, the MFMA module establishes connections between feature layers through multi-scale global pooling and cross-layer feature fusion, thereby enhancing inter-layer contextual modeling capability and improving the perception of the overall image structure. The LAF module performs fine-grained local modeling of feature maps via channel grouping and local attention mechanisms, which strengthens the model’s ability to discriminate key regions and to perceive lesion boundaries.

Furthermore, when both MFMA and LAF modules are incorporated, the model achieves optimal performance, reaching an average classification accuracy of 84.35%, representing a 6.37% improvement over the baseline model. Precision, Recall, and F1 score are also significantly enhanced. This indicates that MFMA and LAF contribute complementarily to the model’s classification outcomes. MFMA strengthens global semantic understanding, while LAF focuses on local salient regions and boundary structures. Together, they synergistically enhance the model’s classification performance.

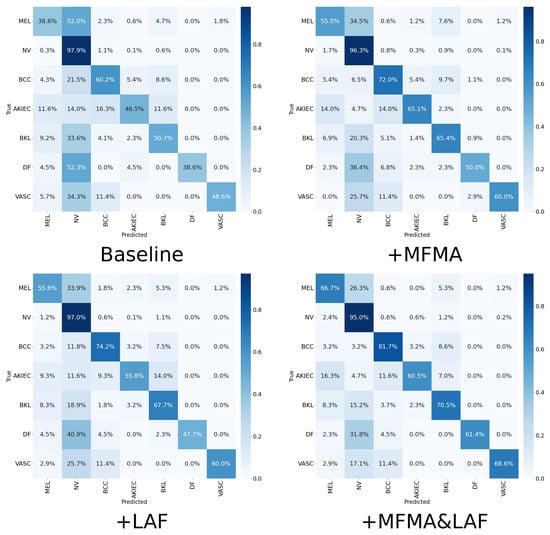

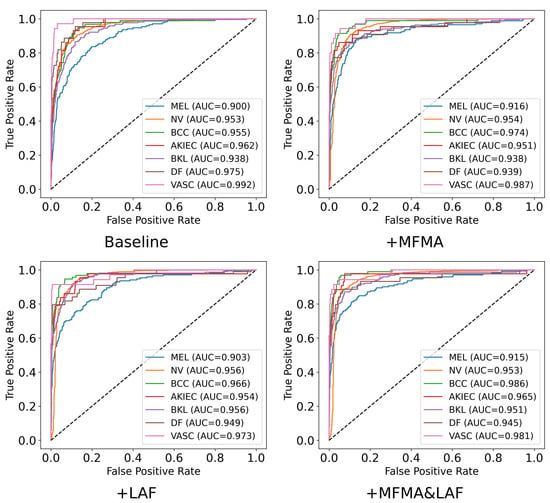

To further explore the specific performance of the MFMA and LAF modules across the seven diagnostic categories, particularly the clinically important MEL, we present in Table 4 the precision, recall, F1 score, specificity, and AUC achieved by each method. The corresponding confusion matrices and ROC plots are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. To ensure clarity and facilitate comparison, the results in Table 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 are from a single run with seed 42. As shown, when MFMA and LAF are introduced separately, the model achieves better classification metrics than the baseline model for most categories. For MEL, the baseline model achieves a recall of only 0.386, clearly exposing its substantial deficiency in identifying this key minority class. After introducing MFMA, the recall for MEL increases to 0.550, while incorporating LAF results in a recall of 0.556, demonstrating the effectiveness of both modules.

Table 4.

Per-Class performance of ablation experiment on ISIC2018.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrices of ablation experiment on ISIC2018.

Figure 6.

ROC plots of each class for the ablation experiment on ISIC2018.

When MFMA and LAF are jointly deployed, the model achieves the best overall performance, especially for the critical categories of MEL, BCC, DF, and VASC, where its recall and F1 are the highest among all methods. This indicates that the combination of MFMA and LAF exhibits a strong synergy, most effectively enhancing the model’s ability to capture positive samples and its overall performance. Notably, MaLafFormer attains the highest recall of 0.667 and F1 score of 0.677 on MEL, the most clinically significant category. Compared with the baseline, recall increases by 0.281 and F1 by 0.193, suggesting a substantially reduced risk of missing fatal cases. Meanwhile, for the most prevalent category of NV, MaLafFormer maintains a high F1 while achieving a specificity of 0.829, effectively lowering the risk of mistakenly excising benign lesions. In addition, for the rare but highly malignant BCC, MaLafFormer raises recall from 0.602 to 0.817, significantly contributing to the early detection of this cancer.

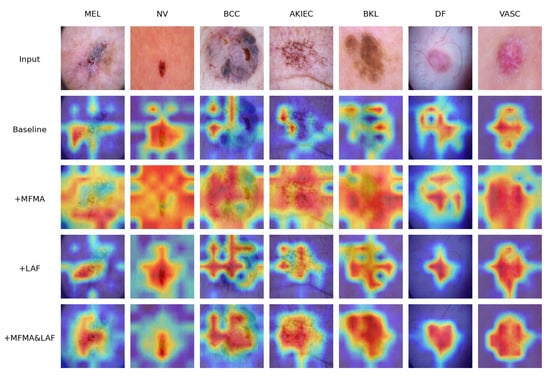

In addition, we employed Grad-CAM to visualize the layer preceding the classification head of the model, allowing the model’s attention regions to be depicted through heatmaps. Grad-CAM visualization results for selected skin lesion images are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Grad-CAM heat maps of ablation study.

It can be observed that, for the baseline model, the attention distribution is easily affected by the background, making it difficult to consistently focus on the lesion regions, with some lesion areas receiving low attention. After introducing the MFMA module, the heatmaps show a significant enhancement of feature responses across the global context, allowing the model to better capture the overall lesion. However, there is also some over-attention to irrelevant areas, indicating that while this module improves global feature modeling, it struggles to focus on key regions. With the addition of the LAF module, the model demonstrates stronger local attention, forming high-response areas in the core lesion regions and covering most of the lesion, showing more precise localization of local target areas, although the overall coverage is still somewhat limited.When both the MFMA and LAF modules are simultaneously incorporated, the heatmaps show coverage of the entire lesion structure while accurately localizing the core lesion regions. This demonstrates that the model not only possesses strong global semantic understanding but also sensitively perceives lesion boundaries, achieving comprehensive and precise attention to the lesion areas.

This coordinated attention to both global and local information enables the model to perform more stably and accurately in identifying lesion boundaries and distinguishing between similar classes, further validating the complementary role and effectiveness of MFMA and LAF in feature modeling.

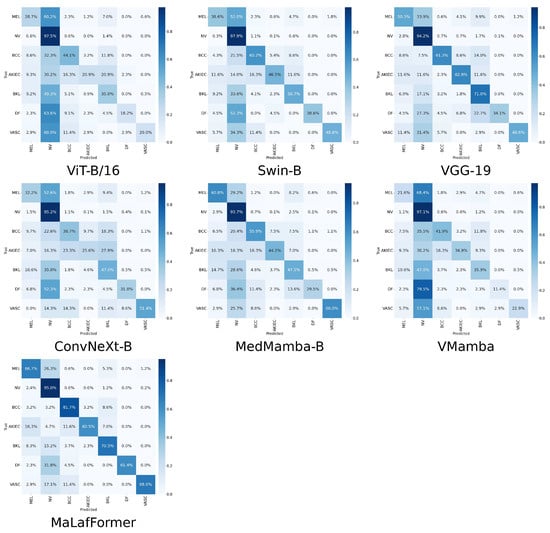

4.4. Comparison with Other Models

We selected six representative image classification models as comparison models, including VGG-19 and ConvNeXt based on CNN architecture, ViT and Swin based on Transformer architecture, and MedMamba and VMamba from the Mamba series. Experiments were conducted on the ISIC2018 dataset, and the overall classification results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Overall performance comparison between MaLafFormer and reference models on the ISIC2018 dataset.

The evaluation results in Table 5 show that the proposed method achieves the best performance in ACC, Precision, Recall, and F1 score. Compared with the ViT and Swin models, MaLafFormer improves classification accuracy by 13.76% and 7.14% respectively. It also outperforms the CNN-based models VGG-19 and ConvNeXt in classification performance. Compared to VMamba, which has a similar parameter scale, MaLafFormer achieved better performance in terms of accuracy with a 14.48% advantage.

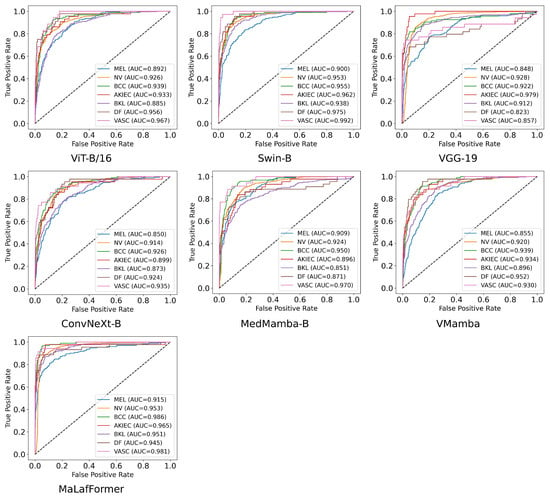

To provide a comprehensive comparison of model performance at the category level, Table 6 presents the per-class precision, recall, F1, specificity, and AUC for all models across the seven lesion categories of the ISIC2018. The corresponding confusion matrices and ROC plots are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Overall, our MaLaFormer demonstrates leading performance across all categories, indicating a robust and generalized capability with no apparent weaknesses on this dataset. Specifically, for MEL, the category with the highest fatality rate, MaLaFormer achieves the highest scores in precision, recall, F1, and AUC while maintaining a specificity of 0.961. Compared to all competing models, MaLaFormer attains the highest specificity for the NV, which has the largest number of samples, suggesting its potential to effectively reduce unnecessary biopsies. Even for the categories with extremely limited samples, namely DF and VASC, our model maintains a recall greater than 61%, confirming its sensitivity to rare lesions. In contrast, models such as VGG-19, ConvNeXt, and MedMamba exhibit relatively low precision and recall rates for most categories. Meanwhile, ViT and Vmamba appear to be significantly influenced by the majority class, resulting in degraded classification performance for other classes.

Table 6.

Per-Class performance of comparison experiment on ISIC2018.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrices of comparison experiment on ISIC2018.

Figure 9.

ROC plots of each class for the comparison experiment on ISIC2018.

These results indicate that MaLafFormer effectively improves the model’s discriminative ability and feature expression ability without relying on a massive increase in parameters or computational complexity.In the comparison of skin lesion classification datasets, it achieves better diagnostic performance than other methods.

5. Conclusions

To assist physicians in rapidly analyzing and identifying skin lesion types, thereby improving diagnostic efficiency, this study presents an enhanced model named MaLafFormer, developed based on the Swin Transformer framework and tailored for skin lesion image classification tasks. Given the limited availability of skin lesion image data and the inherent inter-class similarities, coupled with intra-class variations, conventional classification models often fail to achieve satisfactory performance. MaLafFormer addresses these challenges by integrating MFMA modules and LAF modules, enabling joint modeling of local and global features to effectively enhance overall classification performance. The MFMA module establishes connections between feature layers through cross-layer feature fusion, thereby strengthening the model’s global context modeling capability, while the LAF module guides the model to focus on lesion regions from both channel and spatial perspectives, enhancing its sensitivity to local details and boundary information. Experimental results demonstrate that MaLafFormer achieves a classification accuracy of 84.33% on the ISIC2018 dataset, significantly outperforming baseline models.

Although MaLafFormer has demonstrated promising results, it still exhibits certain limitations. First, the model has been validated only on the ISIC2018 dataset, and its generalization capability to external datasets with different imaging characteristics remains unverified, so the results may not be applicable to other datasets. In addition, the proposed architecture is relatively complex and incurs substantial computational overhead, consequently impeding its applicability for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. In future work, our strategy will be to optimize the model based on the following directions:

- Evaluating the model on other skin lesion datasets, such as HAM10000 and ISIC2019, and extending its application to a broader range of medical image classification tasks.

- Incorporating model compression techniques such as knowledge distillation and pruning to reduce computational complexity and parameter count while maintaining performance, thereby enabling lightweight deployment.

- Leveraging the model’s strengths in feature representation to explore its potential in medical image segmentation tasks.

We anticipate that this study can contribute to advancing practical applications and deployment in the medical domain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W.; methodology, D.W.; software, Q.L. and Y.H.; validation, D.W. and Q.L.; data curation, Q.L. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W., Q.L. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanity and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (No. 21YJA630054), the Zhejiang Province Soft Science Research Program Project (No. 2025C35098), the Open Access Publication Funds/transformative agreements of the Göttingen University (no grant number), and the China Scholarship Council (no grant number).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this paper are available from the ISIC Challenge https://challenge.isic-archive.com/data/#2018 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants for their generous involvement in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNNs | convolutional neural networks |

| MFMA | Modulated Fusion of Multi-scale Attention |

| LAF | Lesion-Area Focus |

| ViTs | Vision Transformers |

| MLP | multilayer perceptron |

| TP | true positive |

| TN | true negative |

| FP | false positive |

| FN | false negative |

| VASC | vascular skin lesions |

| NV | melanocytic nevi |

| DF | dermatofibroma |

| BKL | benign keratosis |

| MEL | melanoma |

| BCC | basal cell carcinoma |

| AKIEC | actinic keratosis |

References

- Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. Dialogue between Skin Microbiota and Immunity. Science 2014, 346, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.T.; Matin, R.N.; Van Der Schaar, M.; Prathivadi Bhayankaram, K.; Ranmuthu, C.K.I.; Islam, M.S.; Behiyat, D.; Boscott, R.; Calanzani, N.; Emery, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Algorithms for Early Detection of Skin Cancer in Community and Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e466–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarin, Y.A.; McCullum, C.; Patel, V.A. 33256 Skin Cancer Screening Practices among Dermatologists: A Survey Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, AB203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cai, W.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, D.D. Feature-Based Image Patch Approximation for Lung Tissue Classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2013, 32, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, D.N.H.; Erkan, U.; Prasath, V.B.S.; Kumar, V.; Hien, N.N. A Skin Lesion Segmentation Method for Dermoscopic Images Based on Adaptive Thresholding with Normalization of Color Models. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ICEEE), Istanbul, Turkey, 16–17 April 2019; pp. 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Morganti, S.; Pareja, F.; Campanella, G.; Bibeau, F.; Fuchs, T.; Loda, M.; Parwani, A.; Scarpa, A.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Entering the Pathology Arena in Oncology: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.; Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.K. Skin Lesion Classification Using Modified Deep and Multi-Directional Invariant Handcrafted Features. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 231, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elaziz, M.A.; Dahou, A.; Mabrouk, A.; El-Sappagh, S.; Aseeri, A.O. An Efficient Artificial Rabbits Optimization Based on Mutation Strategy For Skin Cancer Prediction. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 163, 107154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Qian, C.; Yao, L.; Zhang, K. A Novel Approach for Melanoma Detection Utilizing GAN Synthesis and Vision Transformer. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 176, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Yu, B.; Tao, D. BatchFormer: Learning to Explore Sample Relationships for Robust Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 7246–7256. [Google Scholar]

- Manzari, O.N.; Asgariandehkordi, H.; Koleilat, T.; Xiao, Y.; Rivaz, H. Medical Image Classification with KAN-Integrated Transformers and Dilated Neighborhood Attention. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.C.; Turk, V. Fusion of Transformer Attention and CNN Features for Skin Cancer Detection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilhore, U.K.; Sharma, Y.K.; Simaiya, S.; Alroobaea, R.; Baqasah, A.M.; Alsafyani, M.; Alhazmi, A. SkinEHDLF a Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Accurate Skin Cancer Classification in Complex Systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilandasowmya, G.; Nirmaladevi, G.; Suganthi, S.; Aishwariya, A. Skin Cancer Diagnosis: Leveraging Deep Hidden Features and Ensemble Classifiers for Early Detection and Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti, R.; Teshnehlab, M.; Phung, S.L. Breast Cancer Diagnosis in DCE-MRI Using Mixture Ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 72, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Two-Stage Selective Ensemble of CNN via Deep Tree Training for Medical Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 9194–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğantekin, A.; Özyurt, F.; Avcı, E.; Koç, M. A Novel Approach for Liver Image Classification: PH-C-ELM. Measurement 2019, 137, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhn, J.; Krieghoff-Henning, E.; Jutzi, T.B.; Von Kalle, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Meier, F.; Gellrich, F.F.; Hobelsberger, S.; Hauschild, A.; Schlager, J.G.; et al. Combining CNN-Based Histologic Whole Slide Image Analysis and Patient Data to Improve Skin Cancer Classification. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Sun, G.; Tian, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Long, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, A. HiFuse: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network for Medical Image Classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 87, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.-X.; Tang, Y.-B.; Peng, Y.; Yan, K.; Bagheri, M.; Redd, B.A.; Brandon, C.J.; Lu, Z.; Han, M.; Xiao, J.; et al. Automated Abnormality Classification of Chest Radiographs Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, T.J.; Eom, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, C.; Park, J.-H.; Nguyen, H.M.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, D. TRk-CNN: Transferable Ranking-CNN for Image Classification of Glaucoma, Glaucoma Suspect, and Normal Eyes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 182, 115211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, A.; Ong, J.R.; Tibrewal, A.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Deep Echocardiography: Data-Efficient Supervised and Semi-Supervised Deep Learning towards Automated Diagnosis of Cardiac Disease. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-C.; Kothari, T.; Banerjee, I.; Chute, C.; Ball, R.L.; Borus, N.; Huang, A.; Patel, B.N.; Rajpurkar, P.; Irvin, J.; et al. PENet—a Scalable Deep-Learning Model for Automated Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism Using Volumetric CT Imaging. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yahyapour, R. Forecast Stock Price Based on GRA-LoGo Model of Information Filtering Networks. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 45, 12329–12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yahyapour, R. Nonlinear Parsimonious Modeling Based on Copula–LoGo. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yahyapour, R.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y. A Novel Combining Method of Dynamic and Static Web Crawler with Parallel Computing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 60343–60364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, H. Multi-Feature Stock Price Prediction by LSTM Networks Based on VMD and TMFG. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tao, D. ViTAEv2: Vision Transformer Advanced by Exploring Inductive Bias for Image Recognition and Beyond. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2023, 131, 1141–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, W.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Jiao, L. Multiscale Sparse Cross-Attention Network for Remote Sensing Scene Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5605416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Sisaudia, V.; Meena, J. AgriTL-ViT: A Vision Transformer Model with Attention Techniques for Classification of Plant Leaf Disease. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 294, 128793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, Y.S. Image Super-Resolution Using Dilated Window Transformer. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 60028–60039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Tian, S. Transformer and GAN-Based Super-Resolution Reconstruction Network for Medical Images. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2024, 29, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, H. Depth Information Assisted Collaborative Mutual Promotion Network for Single Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16 June 2024; pp. 2846–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Chang, S.; Wang, Z. TransGAN: Two Pure Transformers Can Make One Strong GAN, and That Can Scale Up. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 14745–14758. [Google Scholar]

- Crowson, K.; Baumann, S.A.; Birch, A.; Abraham, T.M.; Kaplan, D.Z.; Shippole, E. Scalable High-Resolution Pixel-Space Image Synthesis with Hourglass Diffusion Transformers. In Proceedings of the Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Xu, M.; Ren, J.; Cong, Y.; He, S.; Xie, Y.; Sinha, A.; Luo, P.; Xiang, T.; Perez-Rua, J.-M. GenTron: Diffusion Transformers for Image and Video Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16 June 2024; pp. 6441–6451. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, Z.; Liao, B.; Liew, J.H.; Yan, H.; Feng, J.; Wang, X. DiG: Scalable and Efficient Diffusion Models with Gated Linear Attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Miao, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Yang, F.; et al. An Improved Transformer Network for Skin Cancer Classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 149, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.F.; Saba, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Youssef, H.M.; Dahou, A.; Elsheikh, A.H.; El-Bary, A.A.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Ibrahim, R.A. Boosted Nutcracker Optimizer and Chaos Game Optimization with Cross Vision Transformer for Medical Image Classification. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 26, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, S.-Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, Y.-D. RanMerFormer: Randomized Vision Transformer with Token Merging for Brain Tumor Classification. Neurocomputing 2024, 573, 127216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, P.; Song, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. UniFormer: Unifying Convolution and Self-Attention for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12581–12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jégou, H. Training Data-Efficient Image Transformers & Distillation through Attention. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 139, 10347–10357. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Yu, W.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Tay, F.E.H.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. Tokens-to-Token ViT: Training Vision Transformers from Scratch on ImageNet. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 538–547. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: Light-Weight, General-Purpose, and Mobile-Friendly Vision Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.02178. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Rahaman, M.; Sun, H.; Hu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, C.; et al. GasHis-Transformer: A Multi-Scale Visual Transformer Approach for Gastric Histopathological Image Detection. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 130, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörst, F.; Rempe, M.; Heine, L.; Seibold, C.; Keyl, J.; Baldini, G.; Ugurel, S.; Siveke, J.; Grünwald, B.; Egger, J.; et al. CellViT: Vision Transformers for Precise Cell Segmentation and Classification. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 94, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manigrasso, F.; Milazzo, R.; Russo, A.S.; Lamberti, F.; Strand, F.; Pagnani, A.; Morra, L. Mammography Classification with Multi-View Deep Learning Techniques: Investigating Graph and Transformer-Based Architectures. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 99, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Module. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Codella, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Tschandl, P.; Celebi, M.E.; Dusza, S.; Gutman, D.; Helba, B.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Marchetti, M.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.03368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 11966–11976. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.; Li, Z. MedMamba: Vision Mamba for Medical Image Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.03849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10166. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).