Abstract

To address the limitations of single evaluation methods, complex risk factors, and subjective weight allocation in university mining lab safety management, this study proposes an improved EW-FCE model integrating entropy weighting and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation. A multi-level evaluation index system was developed, covering personnel status, hazardous objects, operating environment, and lab standardization (4 secondary and 24 tertiary indicators). By combining objective entropy weights with quantitative risk affiliation from fuzzy evaluation, the model overcomes traditional subjectivity. Applied to a key mining lab in Shanxi, it calculated indicator weights and overall risk values using survey data. Key risk factors identified include special equipment operation certification (weight 0.0909), heavy machinery maintenance records (0.0813), and radioactivity detector qualification (0.0761). The model enables scientific risk ranking and aligns closely with actual lab safety conditions, offering a practical tool for safety management and supporting AI-assisted decision-making in engineering universities.

1. Introduction

With the development of in-depth experimental research and the expansion of cross-function exploratory innovation in China, not only have the types and scale of laboratories in China’s colleges and universities expand significantly [1], but also the intersection across academic disciplines in university laboratories has become more frequent [2]. Statistical analysis reveals that accidents stemming from inadequate laboratory management are frequently severe, and their occurrence is fundamentally linked to unsafe human behaviors [3].

Laboratory safety has received more and more attention in recent years thanks to the increasing activities of scientific research [4]; colleges and universities have been exploring the path to improve the level of laboratory safety management continuously in recent years [5] to strengthen the experimental environment [6] and facilitate its implementation and the effectiveness of the laboratory management workforce [7]; however, there are still many limitations and deficiencies in the safety evaluation methods that seriously restrict the improvement of the laboratory safety management [8], including the breadth and depth of laboratory evaluation, the efficiency and quality of safety management, and the system and assignment of the point of contact for safety management [9].

Mining laboratories are complex laboratories due to the fact that they are highly integrated with various academic fields, including mineralogy, materials science, chemistry, mechanics, engineering, and environmental science [10]. There are a wide range of in-depth scientific research tasks undertaken in the mining laboratories, such as high-stakes chemical experiments, precision instrumentation with powerful, precise, and large-scale experimental simulation, storage of various complex ore samples, onsite trail tests, or even semi-industrial experiments. Intensive field knowledge is required for the staff involved [11], not to mention that a number of uncertainties and potential safety risks could arise with a lack of adequate supervision. The feature of its comprehensiveness and complexity pose serious challenges to the lab safety management [12], from preventing equipment damage and environmental pollution to ensuring the orderly development of mining scientific research and the sustainable development of the mining industry [13], hence there is an urgent need to introduce a more scientific, systematic, and comprehensive evaluation method in order to accurately identify and effectively respond to various types of safety risks, and to ensure laboratory safety and the continuous progress of scientific research activities [14]. Currently, traditional safety evaluation methods are difficult to comprehensively capture and accurately assess the safety performance of mining laboratories, and it is difficult for them to fully consider the special needs of mining laboratories [15]. Therefore, it is particularly urgent to introduce a more advanced and comprehensive safety evaluation method [16].

The entropy weight fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (EW-FCE) method integrates the entropy weight method (which provides objective weighting) with fuzzy mathematics (used for handling uncertainty). The entropy weighting method is used to ascertain the weights; it determines the weights by quantifying the entropy value of each index and employing the fuzzy membership function [17]. As for quantitative scoring, it is achieved through the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method, which effectively addresses the fuzzy and uncertain factors, enhancing the accuracy and objectivity of the evaluation [18]. This method overcomes the limitations identified in traditional statistical analysis in systematic and objective mechanisms for assigning weights [19]: AHP/ANP (Analytic Network Process/Analytic Hierarchy Process) can introduce bias, inconsistency, and strong subjectivity, as it is heavily reliant on expert judgment for pairwise comparisons [20]. The method also effectively handles the comprehensive evaluation of multiple, complex risk factors, which is absolutely advantageous over Fault Tree Analysis (FTA), which is a binary tool that is not inherently designed for comprehensive or multi-criteria evaluation [21]. In recent years, this approach has been widely applied in the field of multi-indicator decision-making [22], giving its outstanding performance in the objectivity of weight distribution [23], the ability to handle fuzziness [24], and the comprehensiveness of the evaluation [25], such as engineering management [26], goaf safety in metal mine [27], and environmental evaluation such as mountainous landslides susceptibility [28,29].

2. The Proposed Methodology

This paper introduces the EW-FCE method into mining laboratories, with the aim of providing robust support for safety management, risk identification, and sustainable development, eventually to help achieve a harmonious balance among economic, social, and environmental benefits, which is significant for enhancing the level of safety management in the field of mining laboratories and promoting sustainable development.

Model Construction

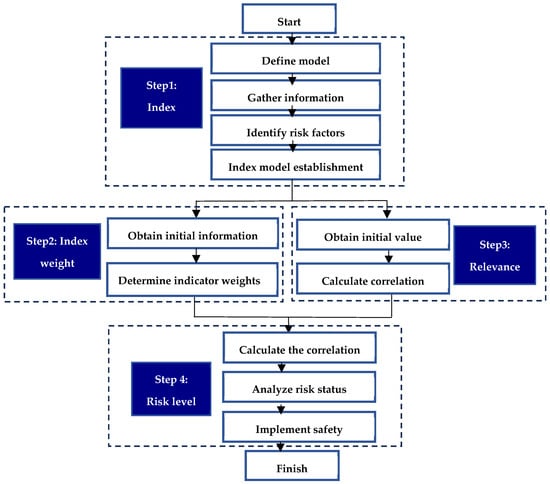

Below, the flowchart showcases the evaluation process regarding the safety evaluation process: details can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Application flow chart of entropy-weighted fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method.

- Step 1, identify risk indicators and establish the index model [30].

Establish a hierarchical safety evaluation system based on an object university mining laboratory.

The evaluation of laboratory safety (A), the first level indicator, covers various types of risks in the mining laboratory and indicates the overall safety status among various types of laboratories in universities, companies, and the other research affiliates. It covers all the possible aspects of the hazards that may exist in the university laboratory [31].

When it comes to secondary indicators, given the complexity and extensive range of experiments inherent in university mining laboratories [32,33], major risks in university mining laboratories are listed and categorized, as can be seen in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Identification of major risks in mining laboratory.

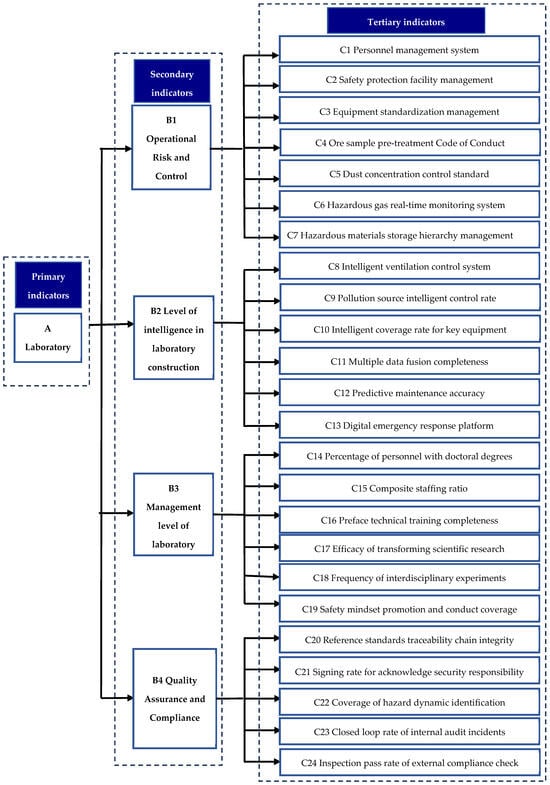

Four aspects are summarized as the secondary indicators to propose a safety evaluation framework to assess the comprehensive performance and characteristics, respectively: operational risk and control (B1) [34], the extent of intelligence in laboratory construction (B2), the management level of laboratory team (B3), and quality assurance and compliance (B4) [35].

As for tertiary indicators, they are further subdivided from the above secondary indicators to reflect specific aspects, with the aim of capturing the nuanced characteristics or performance of the secondary indicators. Specifically, standardized management covers personnel management, safety management, and instrument and equipment management [36]; intelligent construction includes the introduction of intelligent equipment, monitoring and identification alarm system, and information technology platform construction [37]; team and implementation management involves the composition of the team, the implementation of work, and the implementation of safety education and training [38]; responsibility system management covers the traceability of dangers, the implementation of the safety responsibility system, and the implementation of the safety incentive verses punishment mechanism, as well as the auditing of internal and external problems. Three levels of indicators covering 24 aspects of mining laboratories are illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Mining laboratory indicator selection system.

- Step 2, establish evaluation ratings and obtain the initial scoring.

Laboratory staff who have access to the object university laboratory of this paper, including staff operators, safety officers, teachers and trained students, are invited to grade the 24 evaluation criteria and complete the questionnaire. The importance of the index is graded into five dimension, as Table 2 shows below, to determinate the level for each safety factor [39].

Table 2.

Dimension of index importance of each safety factor. Questionnaire respondent ranks the level of every indicator by ticking ✓/✗ to its corresponding dimension.

- Step 3, Calculate the weight indicators occupied by each influence factor through the entropy weight method.

The basic steps of the entropy weight method are as follows.

① Determine the matrix R of factors influencing the object of evaluation.

② Calculate the weights of the indicators of the evaluation object.

③ Calculate the entropy value of the evaluation object indicator.

where k = 1/ln(m).

The formula transforms to

④ Calculate the entropy weight of the indicators of the evaluation object.

The formula transforms to

⑤ Determine the combined weight βj of the indicators of the evaluation object.

Following the calculation process described above, it is possible to determine the specific weights of each tertiary indicator and each secondary indicator, thus obtaining weight indicators for the next step of specific analysis [40].

- Step 4, determine the index weights by calculating the degree of correlation.

Fuzzy comprehensive analysis is proposed to integrate fuzzy logic and hierarchical analysis. The basic steps of the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method are as follows.

① Primary fuzzy comprehensive evaluation organizes the weight vector of each three-level indicator and completes a 4 × 5 fuzzy relationship matrix based on the factors affecting safety production in the example laboratory.

② Synthesize the influencing factors of the various processes in the various types of laboratories in the evaluation example and utilize the primary fuzzy synthesis evaluation matrix with secondary weights to derive an evaluation B.

Utilizing the principle of maximum affiliation, the entropy weight method, and fuzzy comprehensive analysis, the evaluation of B is derived. Consequently, the safety hazard level of the laboratory can be determined.

Specific improvements can be achieved with the EW-FCE method; first of all, the improved EW-FCE method constructed the risk indicators into hierarchical 4 × 24 evaluation framework, which spans from physical hazards to managerial and digital risks for university mining laboratory. Another incorporated improvement is the iteration system for dynamic updating; for example, when new equipment is introduced, a provisional risk assessment is first conducted based on manufacturer specifications and hazard analysis, followed by a 3–6 months monitoring period to collect operational safety data, after which the model is re-run to objectively recalibrate the relevant indicator weights. Furthermore, a Risk Response Matrix is proposed, linking the output of the method to specific management actions. The matrix aims to trigger an immediate action plan under severe scenarios and call for annual review by a committee of safety managers and senior researchers for the technological or regulatory changes, as well as to analyze the safety standards, recent incidents, and user feedbacks, in order to make sure that the evaluation model remains relevant and accurate, and the system remains comprehensively aligned.

- Step 5, analyze the risk status to determine the risk level and implement safety measures [41].

The evaluated risk level of each indicator reflects the relative importance of the associated hazard, thereby guiding the prioritization of control measures in the university mining laboratory’s risk management. Based on this prioritization, targeted safety measures can be developed to reduce the likelihood or mitigate the consequences of potential accidents. Ultimately, a follow-up risk assessment should be conducted to verify the effectiveness of the implemented measures, forming a closed-loop safety management system. To ensure the model’s long-term validity, the weight coefficients and indicator system are designed for an annual review cycle. This update can be triggered by significant changes, such as the introduction of new equipment, which requires a provisional risk assessment followed by a validation period using operational data to recalibrate the model.

3. Case Study

This study takes a mining laboratory in Shanxi Province as its research subject. This laboratory is comprehensive and the goal is to conduct research in multiple areas of the mining industry. Among a ballpark figure of 200 laboratory staff who have access to this paper’s object university mining laboratory, 50 frequent visitors were invited, including staff operators, safety officers, teachers, and trained senior students, to grade the 24 evaluation criteria and complete the questionnaire. Table 3 below shows how many of the respondents assigned each of the five risk levels—Low, Relatively Low, Medium, Relatively High, and High—to the 24 tertiary indicators.

Table 3.

Statistics of evaluation level of each safety factor.

3.1. Model Calculation

The data calculated based on statistics is as follows.

- (1)

- Determine the entropy weight values of the tertiary indicators of entropy weight sorting using the following formula:

- (2)

- Calculate the measurement values of the tertiary indicators of personnel status factors for C1–C7 and organize the fuzzy comprehensive judgment matrix as follows:

- (3)

- Obtain the information entropy values for each tertiary indicator:

Similarly, ; ; ; ; ;

From the following formula:

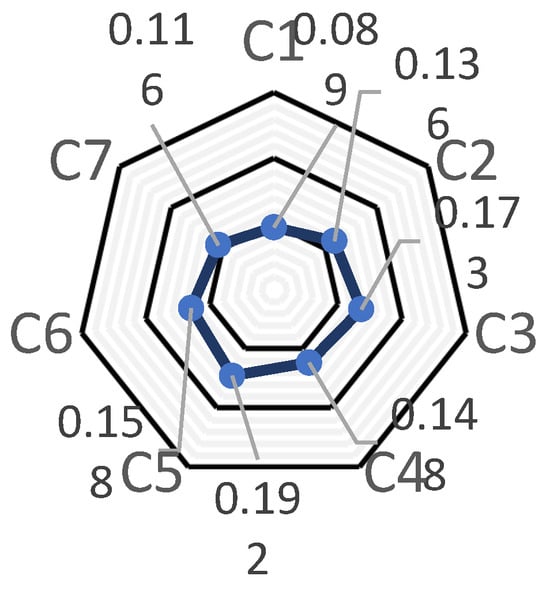

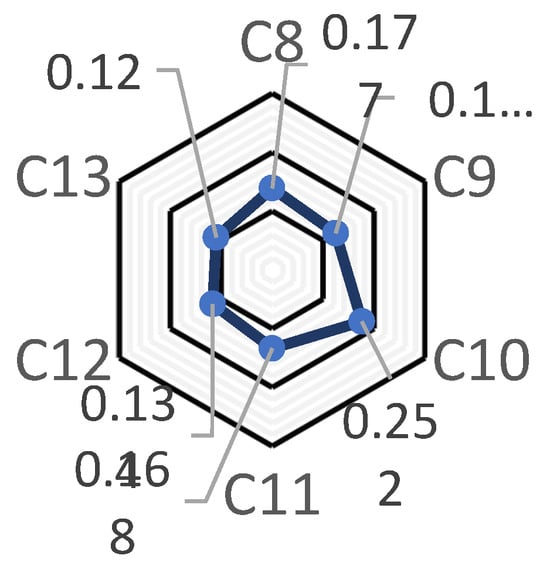

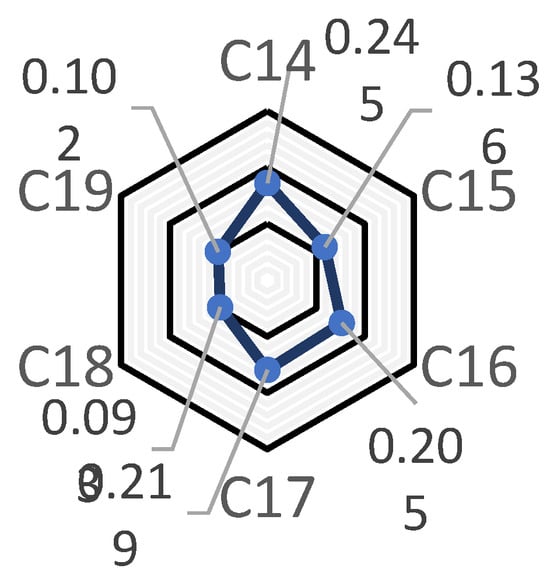

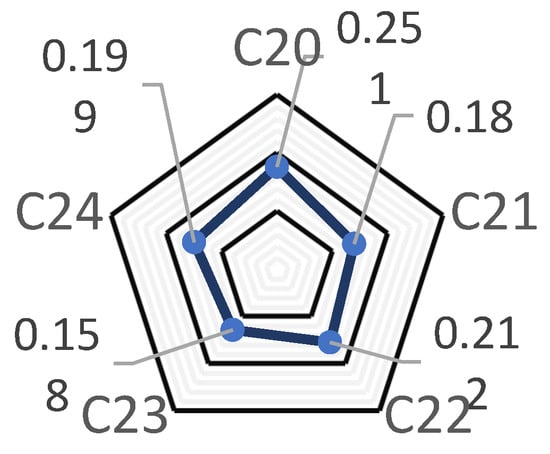

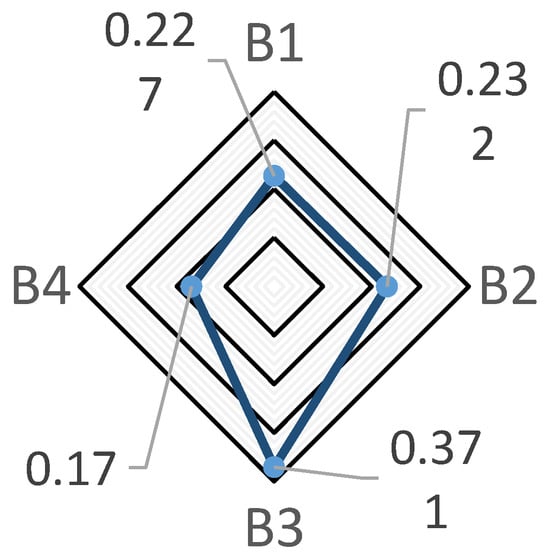

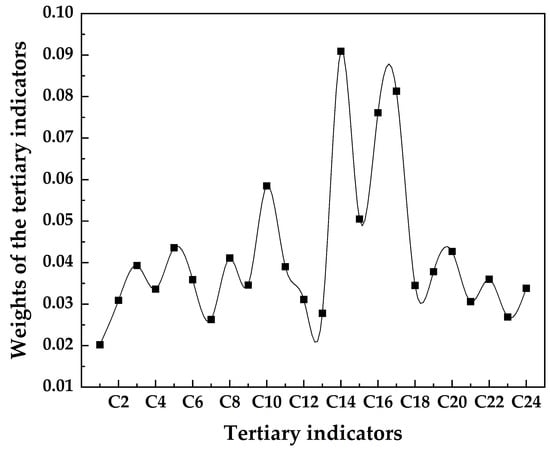

The information entropy weight is shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 below.

Figure 3.

C1–C7 indicators weights.

Figure 4.

C8–C13 indicator weights.

Figure 5.

C14–C19 indicator weights.

Figure 6.

C20–C24 indicator weights.

Figure 7.

Weights of indicators B1–B4.

- (4)

- Calculate each secondary weight.

First calculate the sum of variation coefficients for each secondary indicator; then apply Formula (12) to obtain secondary weights.

Next, calculate the weighting results of the target layer derived from the secondary indicator layer for the tertiary indicator Ci, and represent the weighting results of the tertiary indicator Ci for the primary indicator A as WA/Ci.

Refer to Table 4 for the statistical table of laboratory safety factor analysis.

Table 4.

Statistical table of factors analysis.

The weights of the tertiary indicators were calculated using the entropy weight method. By comparing the model’s output with the laboratory’s historical accident records after consulted and audited by safety experts on-site [42], the results showed that 83% of the identified high-risk factors corresponded to the primary causes of incidents over the past three years, indicating strong practical concordance. In order to further strengthen the finding validity, Cohen’s Kappa analysis as a statistical test was performed to measure the agreement between the risk levels identified by our improved EW-FCE model and the risk levels derived from the laboratory’s historical incident reports and expert audits. The analysis resulted in a Kappa statistic of 0.78, which indicates substantial agreement beyond chance. The result showed that our model’s assessments are consistent with the laboratory’s documented safety performance.

The results as shown in Figure 8 indicated that within the standardization of laboratory management (B1), the weights of dust concentration control standard (0.0436) and equipment standardization management (0.0393) were significant. In laboratory responsibility system management level (B4), the reference standards traceability chain integrity (0.0427) notably influences overall risk. The top five weighted indicators are predominantly concentrated in laboratory team and the level of execution management (B3), affirming the characteristic of human-factor risk dominance in mining laboratories.

Figure 8.

Comprehensive risk value of tertiary indicators.

The membership distribution of safety states indicates that the average membership value for high-risk levels is 0.18, and 0.42 for medium-risk levels, which aligns with the laboratory’s actual “medium-risk dominant” status. The weight distribution of engineering control measures, such as the intelligent ventilation control system (0.0411), validates the effectiveness of equipment upgrades in mitigating risks.

3.2. Result Analysis

The calculated weights and comprehensive risk values presented in Table 2 provide a quantitative ranking of risk factors. The results indicate that human-factor-related indicators within the “Laboratory team and the level of execution management” (B3) category, such as the “Percentage of personnel with doctoral degrees” (C14, weight 0.0909), and “Efficacy of transforming scientific research” (C17, weight 0.0813), are the most critical, affirming the personnel-dependent nature of safety in mining laboratories. Furthermore, engineering controls like the “Intelligent coverage rate for key equipment” (C10, weight 0.0585) also carry significant weight, validating the importance of technological investments in risk mitigation.

However, the identification of risk levels is only the first step in effective safety management. To translate these diagnostic results into actionable strategies, a Risk Response Matrix is proposed, linking the output of the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (e.g., Low, Lower, Medium, Higher, and High) to specific management actions. This framework provides laboratory managers with a clear and immediate protocol for incident prevention and control, moving beyond assessment to proactive governance. The matrix is detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Risk Response Matrix for laboratory safety management.

The application of the improved EW-FCE model successfully identified and quantified key risk factors within the mining laboratory, and the evaluation results obtained through this method correspond with actual conditions [43]. The results demonstrate a high degree of concordance with empirical safety records. The concentration within the “Laboratory team and the level of execution management (B3)” category affirms the characteristic of human-factor dominance in mining laboratory risks, providing laboratory managers universal and operational decision-making with a scientific, quantitative basis [44,45].

Furthermore, it validates the importance of specific engineering controls, such as the intelligent ventilation control system (C8, Weight: 0.0411), confirming the effectiveness of equipment upgrades in risk mitigation. In the current era of rapid AI development, AI software such as DeepSeek and ChatGPT is continuously emerging. The results enable laboratory managers to prioritize resources and interventions effectively, focusing on the most impactful risk factors. For example, users can import the model into these platforms, input the collected data, and obtain safety analyses based on the model [46,47], which significantly improves the model’s computational efficiency and reduces the time required, making it convenient for other university laboratories to adopt and promote.

4. Conclusions

The improved EW-FCE model developed in this study achieves three major breakthroughs: it proposes a multi-level indicator system for mining laboratories (4 × 24 structure), encompassing all elements from traditional mechanical safety to intelligent monitoring systems; through the integration of entropy weight and fuzzy algorithms, it reduces subjective judgment errors to 9.7% (compared to the traditional AHP method); and the development of a weight calculation module embedded in AI platforms enables full-process automation from data collection to risk visualization.

The EW-FCE method holds promising future prospects for mining laboratories, as it can scientifically and objectively evaluate various factors such as equipment performance, resource utilization efficiency, and safety management levels. As mining technology continues to advance and requirements for laboratories become increasingly stringent, the use of computer programs to collect information and perform calculations will demonstrate significant advantages and broad application prospects. This method not only provides quantitative management tools for mining laboratories but also offers a transferable methodological framework for safety governance in high-risk industrial laboratories.

While this model provides a robust framework for scientific risk identification, its full value can be further solidified through a comprehensive cost–benefit analysis in future work. Tracking key performance indicators (KPIs), such as the reduction in equipment repair costs, decreases in safety incident-related downtime, and potential savings on insurance premiums, is essential. Quantifying the model’s economic impact by calculating the system’s payback period will be critical for demonstrating a clear return on investment (ROI). This financial validation will not only underscore the model’s practical utility but also accelerate its adoption across engineering universities, transforming safety management from a cost center into a strategic, value-adding investment. Future research will therefore focus on integrating financial and operational data to track these KPIs, providing stakeholders with a complete picture of the model’s risk-management and economic benefits.

Despite its advantages, the improved EW-FCE model has certain limitations. Firstly, the model is used for university mining laboratory, with the characteristics of comprehensiveness and large scale, the effectiveness massively relies on the quality and comprehensiveness of the raw input data. Secondly, the initial construction of the evaluation index system is of great importance to the evaluation result. An improperly structured indicator system may fail to capture critical risks, leading to an incomplete safety picture. Future research may focus on developing a dynamic indicator system that can be updated with new data, integrating real-time sensor data streams to automate the data collection process and exploring adaptive learning algorithms to further minimize the need for manual re-calibration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and C.Z.; methodology, C.Z.; validation, Y.T.; data curation, Y.T. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and Y.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.T.; visualization, D.Z., H.Y., B.S. and J.S.; supervision, J.L. and J.G.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanxi Provincial Education Reform Project, grant number J20240248, and Shanxi Key Laboratory Funds of Mine Rock Strata Control and Disaster Prevention, grant number 202104010910021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks for Taiyuan Wendao Enterprise Management Consulting Co., Ltd. and PuShiRangYou Group for the support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Kang, Q.; Zou, Y.; Yu, S.; Ke, Y.; Peng, P. Research on Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Metal Mine Emergency Rescue System Based on Game Theory and Regret Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Yang, M.; Li, H. A Semi-Quantitative Methodology for Risk Assessment of University Chemical Laboratory. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 72, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, T.; Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, D.; Fu, G. Current Challenges of University Laboratory: Characteristics of Human Factors and Safety Management System Deficiencies Based on Accident Statistics. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 86, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L. Coal Mine Safety Evaluation Based on EWM-Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1549, 042055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Liang, W.; Zhao, G. Linguistic Neutrosophic Power Muirhead Mean Operators for Safety Evaluation of Mines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, L.; Tian, S. Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Coal Mine Safety under the Combination of Game Theory and TOPSIS. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5623282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Liu, H.; Ren, F.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y. Comprehensive Evaluation and Decision for Goaf Based on Fuzzy Theory in Underground Metal Mine. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Pang, C. Evaluation on the Risk of Water Inrush Due to Roof Bed Separation Based on Improved Set Pair Analysis–Variable Fuzzy Sets. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 9430–9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, A.U.C.; Lawrence, W.; Jalsa, N.K. Chemical Laboratory Safety Awareness, Attitudes and Practices of Tertiary Students. Saf. Sci. 2017, 96, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Jing, G.; Zeng, Q. Online Evaluation Method of Coal Mine Comprehensive Level Based on FCE. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubis, A.; Werbińska-Wojciechowska, S.; Wroblewski, A. Risk Assessment Methods in Mining Industry—A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimdel, M.J.; Mohammadpour, R. Enhancing Mineral Transportation Systems in Underground Mines: A Framework for Capacity Analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Han, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, K.; Du, Z.; Miao, T. Risk Assessment of Water Inrush from Coal Seam Roof Based on Combination Weighting-Set Pair Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingwen, L.; Jiangang, Q.; Yuanming, D.; Xu, F.; Xiaoli, L. Safety Evaluation Method of Antifloating Anchor System Based on Comprehensive Weighting Method and Gray-Fuzzy Theory. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3216948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, N. Study on the Model of Safety Evaluation in Coal Mine Based on Fuzzy-AHP Comprehensive Evaluation Method. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Mechatronic Science, Electric Engineering and Computer (MEC), Jilin, China, 19–22 August 2011; pp. 1671–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Cinar, U.; Cebi, S. A Hybrid Risk Assessment Method for Mining Sector Based on QFD, Fuzzy Inference System, and AHP. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. Appl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 39, 6047–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhravar, H. Quantifying Uncertainty in Risk Assessment Using Fuzzy Theory. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.J.; Ren, J.H.; Yu, S.H.; Cui, W. Entropy Weight-Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method of the Safety Evaluation of Water Inrush. AMR 2013, 868, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanaseva, O.; Bezyukov, O.; Pervukhin, D.; Tukeev, D. Experimental Study Results Processing Method for the Marine Diesel Engines Vibration Activity Caused by the Cylinder-Piston Group Operations. Inventions 2023, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, C.C.C.; Xu, J.; Ma, Z.; Shuai, P.; Zhang, L. Safety Risk Assessment and Management of Panzhihua Open Pit (OP)-Underground (UG) Iron Mine Based on AHP-FCE, Sichuan Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-L.; Shia, Y.-B.; Sun, Z.-Y. A Hybrid Fuzzy FTA-AHP Method for Risk Decision-Making in Accident Emergency Response of Work System. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 29, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chong, X.; Bao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, S. Fuzzy Comprehensive Assessment Method Based on the Entropy Weight Method and Its Application in the Water Environmental Safety Evaluation of the Heshangshan Drinking Water Source Area, Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Water 2017, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Jia, B.; Shen, Z.; Wang, P.; Hu, E.; Wang, H. Research on Evaluation of Coal Mine Safety Risk Based on AHP-MCS Coupling TOPSIS. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 115016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Wei, W.; Xia, X.; Woźniak, M.; Damaševičius, R. Safety Risk Assessment of a Pb-Zn Mine Based on Fuzzy-Grey Correlation Analysis. Electronics 2020, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, S.R.; Durdyev, S.; Sadeghi, H.; Mahdiyar, A.; Hosseini, M.R.; Banihashemi, S.; Martek, I. Towards Enhancement in Reliability and Safety of Construction Projects: Developing a Hybrid Multi-Dimensional Fuzzy-Based Approach. ECAM 2023, 30, 2255–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.; Ak, M.F.; Guneri, A.F. Pythagorean Fuzzy VIKOR-Based Approach for Safety Risk Assessment in Mine Industry. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 69, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yao, L.; Mei, G.; Liu, T.; Ning, Y. A Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation Method Based on AHP and Entropy for a Landslide Susceptibility Map. Entropy 2017, 19, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hao, Z.; Liu, K.; Tao, Z.; Shi, G. An Improved Unascertained Measure-Set Pair Analysis Model Based on Fuzzy AHP and Entropy for Landslide Susceptibility Zonation Mapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation of Collapse Risk in Mountain Tunnels Based on Game Theory. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubis, A.; Werbińska-Wojciechowska, S.; Sliwinski, P.; Zimroz, R. Fuzzy Risk-Based Maintenance Strategy with Safety Considerations for the Mining Industry. Sensors 2022, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; He, R.; Ma, C.; Zhang, W. Evaluation of Urban Taxi-Carpooling Matching Schemes Based on Entropy Weight Fuzzy Matter-Element. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 81, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ye, Y.; Hu, N.; Wang, Q.; Tan, W. Uncertainty Prediction of Mining Safety Production Situation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 64775–64791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Jiang, P.; Zheng, S. The Application of Cloud Model Combined with Nonlinear Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process for the Safety Assessment of Chemical Plant Production Process. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 145, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannani, M.; Bascompta, M.; Sabzevar, M.G.; Dehghani, H.; Khajevandi, A.A. Causal Analysis of Safety Risk Perception of Iranian Coal Mining Workers Using Fuzzy Delphi and DEMATEL. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Shi, L.; Qu, X.; Bilal, A.; Qiu, M.; Gao, W. Multi-Model Fusion for Assessing Risk of Inrush of Limestone Karst Water through the Mine Floor. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, L.; Zheng, M.; Wan, H.; Dong, Y.; Lu, G.; Xu, C. Comprehensive Evaluation of Crack Safety of Hydraulic Concrete Based on Improved Combination Weighted-Extension Cloud Theory. Water 2024, 16, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Johansson, J.; Zhang, J. Comprehensive Evaluation on Employee Satisfaction of Mine Occupational Health and Safety Management System Based on Improved AHP and 2-Tuple Linguistic Information. Sustainability 2017, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiskani, I.M.; Han, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Shahani, N.M.; Tariq, M.; Brohi, M.A. An Integrated Entropy Weight and Grey Clustering Method–Based Evaluation to Improve Safety in Mines. Min. Metall. Explor. 2021, 38, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Fang, H.; Liu, K.; Xue, B.; Cai, X. Environmental Evaluation of Coal Mines Based on Generalized Linear Model and Nonlinear Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 8836908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, G. Combination Evaluation Method of Fuzzy C-Mean Clustering Validity Based on Hybrid Weighted Strategy. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 27239–27261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Chen, S.-M. Multiattribute Decision Making Based on Converted Decision Matrices, Probability Density Functions, and Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Values. Inf. Sci. 2021, 554, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Ren, B.; Su, M.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Yu, G.; Wei, T.; Han, Y. A New Quantitative Method for Risk Assessment of Coal Floor Water Inrush Based on PSR Theory and Extension Cloud Model. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 5520351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, J. Risk Assessment and Zonation of Roof Water Inrush Based on the Analytic Hierarchy Process, Principle Component Analysis, and Improved Game Theory (AHP–PCA–IGT) Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Cao, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, J. The Evaluation of Coal Mine Safety Based on Entropy Method and Mutation Theory. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 769, 032023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Sui, W. Risk Evaluation of Mine-Water Inrush Based on Principal Component Logistic Regression Analysis and an Improved Analytic Hierarchy Process. Hydrogeol. J. 2021, 29, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, M.; Baïna, K.; Tabii, Y.; Ressami, E.M.; Adlaoui, Y.; Benzakour, I.; Abdelwahed, E.H. The Future of Mine Safety: A Comprehensive Review of Anti-Collision Systems Based on Computer Vision in Underground Mines. Sensors 2023, 23, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Geng, Z. Safety Monitoring Method of Moving Target in Underground Coal Mine Based on Computer Vision Processing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).