Abstract

Additive manufacturing processes like fused filament fabrication (FFF) have gained widespread adoption due to their versatility and cost-effectiveness in creating complex geometries. However, to optimize and control the FFF process effectively, it is crucial from a control perspective to develop accurate process models that capture temperature and flow rate dynamics. This study explores the modeling of FFF process dynamics through system identification techniques, utilizing the process sensing capabilities for a robotic FFF testbed. Various model structures are investigated including first-order and second-order transfer function models, process models, and state space models. The analysis shows that a first-order process model with a first-order disturbance component offers the best fit for the experimental data, demonstrating strong generalized performance (NRMSE fit > 90%). Moreover, an analytical process model for polymer flow rate dynamics developed from first-principles modeling is validated against its empirical counterpart derived through system identification, showing close agreement across operating conditions (NRMSE fit 70 to 90%). These findings advance the fundamental understanding of FFF dynamics and provide a basis for future model-based control strategies.

1. Introduction

Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) is a widely used additive manufacturing process for producing polymer parts in applications ranging from prototyping to functional end-use components. In FFF, a thermoplastic filament is fed into a heated liquefier, melted, and extruded through a nozzle to form a continuous bead of molten material. The deposition of this material along predefined toolpaths and the stacking of successive layers yield the final part geometry. FFF is attractive not only for its low cost and geometric flexibility but also for its ability to process a wide spectrum of thermoplastic polymers, ranging from commodity plastics to engineering-grade and high-performance materials. Common commodity polymers include polylactic acid (PLA), acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS), polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG), and acrylonitrile–styrene–acrylate (ASA), which offer broad processing windows and stable melt behavior. Engineering polymers such as polyamide (PA6/PA12), polycarbonate (PC), polypropylene (PP), thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), and PC-ABS blends require tighter thermal control and exhibit stronger coupling between temperature and viscosity. At the upper tier, high-performance polymers, including polyether ether ketone (PEEK), polyether ketone ketone (PEKK), polyetherimide (PEI, e.g., ULTEM), and polyphenylsulfone (PPSU), demand elevated melt temperatures (300–400 °C) and precise control of thermal histories due to their high melt viscosities and narrow processing windows.

Ensuring consistent part quality remains a challenge in the FFF process. Transient deviations in polymer melt temperature or volumetric flow rate during deposition can cause dimensional inaccuracies, poor inter-layer bonding, and surface defects. In industrial settings, such variability limits process repeatability and complicates part qualification. This has driven growing interest in understanding and modeling FFF process dynamics, where accurate plant models can enable model-based control for compensation of disturbances and facilitate real-time quality assurance.

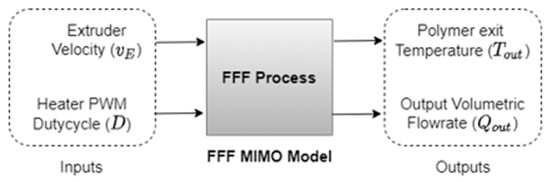

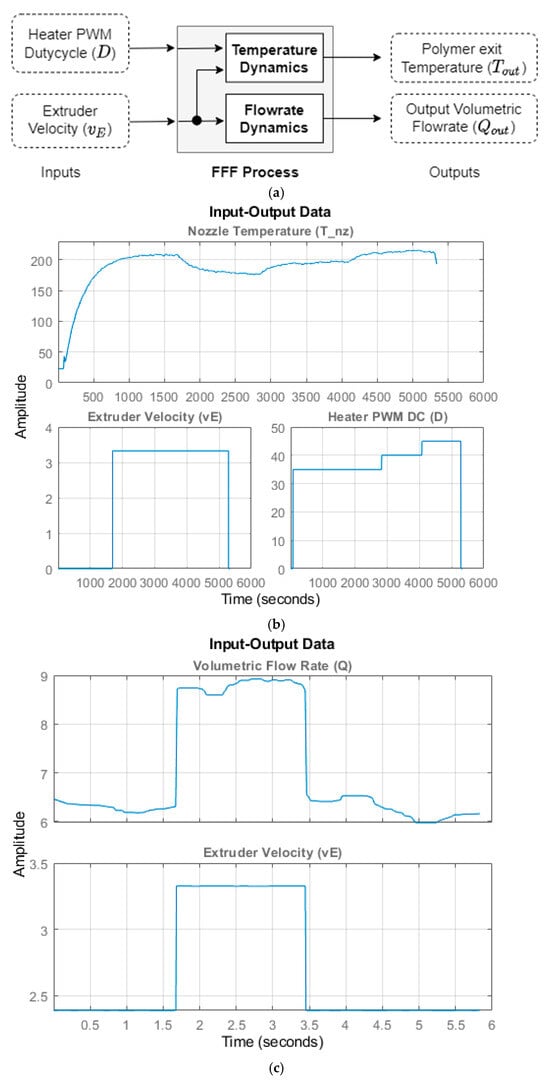

The dynamics of the FFF process can be viewed as a two-input, two-output system, as shown in Figure 1. The inputs to the system are the duty cycle () of the pulse width modulated (PWM) signal that controls the heater in the liquefier block and the linear input velocity of the filament into the liquefier (), while the outputs from the system are the melt temperature of the polymer exiting the nozzle () and the output polymer flow rate (). The goal of this work is to model the dynamics of the FFF process to develop analytical and data-driven process models that are appropriate for real-time process control.

Figure 1.

Multi-input–multi-output (MIMO) model for FFF process.

1.1. Literature Review

There is a dearth of work on modeling extrusion dynamics in the FFF process. The earliest effort in this field was conducted by Bellini et al. [1] who modeled the extrusion dynamics as a first-order linear time-invariant (LTI) model using an equivalent electrical circuit representation of the dynamics. The experimental measurement of deposited road geometry showed that the parameters (time delay, deadtime) of the LTI model vary significantly as functions of the operating condition (e.g., extrusion rate), thus revealing the presence of nonlinearity in extrusion dynamics. A 12% steady-state error between the input command and the resulting flow rate was observed that was deemed to be a result of the slip conditions between filament and rollers. Typically, in an FFF process, the synchronization between motion and extrusion controllers is achieved using a static gain that commands the extrusion rate to be proportional to the motion velocity [2,3]. The gain is usually calibrated using trial and error experiments to achieve the desired wall thickness or extrusion width. In practice, the existing extrusion controllers in the FFF process are mostly based on open-loop, feedforward approaches and are prone to transient errors like over- and under-extrusion. Chesser et al. [4] used an empirically derived model of the extrusion system to implement feedforward control of polymer flow rate in big area additive manufacturing (BAAM) system to realize uniform material deposition during corners and curves. Modern-day firmware (Marlin, Klipper, RepRap-Duet) in FFF printers uses an approach called “Linear Advance” or “Pressure Advance” [5,6,7] to compensate for these transient defects. These advance algorithms assume that the root cause of the transient errors is the compression of the filament in the extruder combined with the pressure loss in the nozzle due to acceleration of material and frictional forces inside the nozzle during the acceleration of the filament. These advance algorithms work to adjust the extrusion rate during acceleration and deceleration of the motion system using an experimentally determined gain called the K-factor. The K-factor is dependent on the material and the layer height parameters [2,8]. Wu et al. [9] developed an empirical nonlinear model of the extrusion process to design a nonlinear feedforward extrusion controller that was shown to improve deposition accuracy by about 35%.

Foundational reviews such as those by Turner, Strong, and Gold [10,11] established the baseline understanding of melt–extrusion physics, process parameter effects, and dimensional accuracy considerations, while more recent surveys by Liu et al. [12], Shaqour et al. [13], and Al-Rashid et al. [14] have updated these insights, emphasizing emerging needs for control-aware modeling and in-situ monitoring. At the process physics level, Serdeczny et al. [15] experimentally and analytically quantified pressure drop through the nozzle under non-Newtonian rheology, linking it to feed-force requirements, whereas Colón et al. [16] mapped the dependencies among feed rate, liquefier temperature, and melt pressure across multiple thermoplastics. Complementing these, Zhang et al. [17] characterized non-isothermal temperature fields from filament entry to deposition, underscoring their influence on melt flow and bonding dynamics.

Interfacial bonding has been extensively studied through the lens of polymer welding theory, with Bellehumeur et al. [18] and Sun et al. [19] demonstrating how inter-layer bond strength is governed by the thermal history at the weld interface. Subsequent work by Zhou et al. [20] and Coogan et al. [21] incorporated molecular diffusion and contact-pressure effects into predictive models, while Costanzo et al. [22] addressed crystallization kinetics in semi-crystalline systems, linking them directly to weld formation quality.

In-situ sensing approaches have sought to capture the melt state directly; for example, Anderegg et al. [23] developed an instrumented nozzle with embedded thermocouples and pressure transducers to reveal melt temperature drops at higher flow rates, validating thermal and pressure models. There have also been numerous studies of in-situ sensing in FFF using optical [24,25], acoustic [26,27,28,29], thermal imaging [30,31,32,33], and combined multimodal approaches [34,35], aimed at monitoring bead geometry, melt state, and defect formation in real time. Geometric and flow monitoring using vision systems has also seen rapid growth. Li et al. [36] demonstrated real-time classification of extrusion states from image sequences, enabling automated defect detection. Moving beyond static correlations, system identification and control frameworks have emerged to capture process dynamics. Habbal [37] proposed an automated bead and flow measurement platform for slicer-aware control design, Read et al. [38] implemented a data-driven extrusion-force controller leveraging real-time feedback, and Zomorodi and Landers [39] formulated an explicit model-predictive control approach for extrusion rate regulation.

However, none of the above-mentioned studies deal with development of plant models to capture the interactions between temperature and extrusion dynamics in the FFF process from a control point of view. Specifically, the temperature of the molten polymer exiting the nozzle is known to be sensitive to transient changes in flow rates during printing. Additionally, to the best of the author’s knowledge, there is no existing analytical plant model for describing extrusion dynamics in the FFF process. Thus, the goal of this paper is to develop a plant model for the FFF process using analytical and/or data-driven system identification techniques that are usable for process control and to explore control strategies for closed-loop control of temperature and polymer flow rate using simulations.

1.2. Contributions of This Work

The main contribution of this work is the development of plant models for both temperature and flow rate dynamics in FFF using control-oriented, data-driven system identification informed by real-time measurements from an instrumented robotic testbed. This includes identification of multiple-input, single-output (MISO) temperature dynamics and single-input, single-output (SISO) flow rate dynamics. In parallel, a first-principles analytical model of flow rate dynamics is formulated based on liquefier and nozzle physics, yielding a first-order process form with physically interpretable gain and time constant parameters. A quantitative cross-validation between the analytical and empirically identified flow models demonstrates strong agreement across operating regimes. While the experimental platform is robotic, the modeling methodology is generic and applicable to any FFF system, regardless of the motion control system.

In Section 2, the analytical model for polymer flow rate dynamics is presented. Section 3 discusses the experimental testbed and data acquisition approach for system identification along with details of the excitation inputs. Section 4 details the data driven system identification process and validation of resulting polymer flow rate and temperature plant models. Section 5 concludes the paper with key findings and outlines directions for future work.

2. Developing an Analytical Process Model for the FFF Process

2.1. Polymer Flow Rate Dynamics

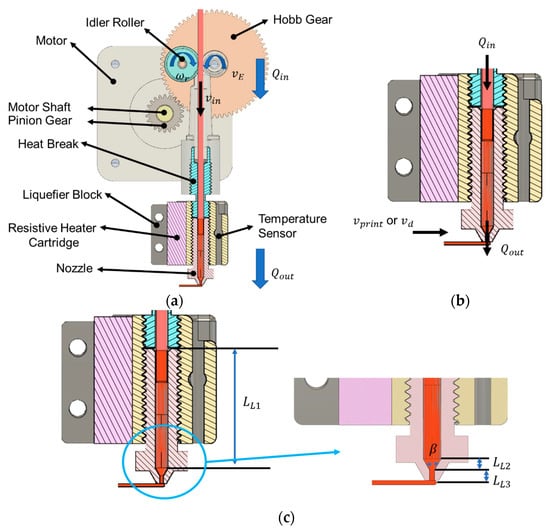

Figure 2 shows the construction of a direct-drive extrusion system used in the FFF process. In the FFF process, the input polymer flow rate () to the liquefier is controlled to produce an output flow rate () from the liquefier that is proportional to the deposition velocity (), resulting in a road of uniform cross-sectional area, as defined by the slicer during toolpath generation. The cross-sectional area of the deposited road () is defined by the extrusion width () and layer height () parameters and can be computed according to Equation (1).

Figure 2.

(a) Overview of direct-drive extrusion system in FFF process; (b) closer view of liquefier block and melt flow output from nozzle; (c) geometry of liquefier for volume calculation.

To model the extrusion dynamics within the liquefier, consider that a strand of filament is fed into the liquefier at an input flow rate . is controlled by the speed of rotation of the motor-driven feed rollers that grip onto the filament and push it down into the liquefier at a linear velocity called extruder velocity (), wherein the solid filament above the liquefier block acts as a piston. The relationship between and is given by Equation (2).

where is the diameter of the filament [mm] and is the linear input velocity of filament into the liquefier [mm/s]. Feeding solid filament strand into liquefier causes pressurization wherein the filament is heated to a semi-liquid state and extruded from the nozzle orifice at a given output flow rate, . The relationship between and deposition velocity () is given by Equation (3).

At any given point of time, the liquefier has a fluid volume, , that changes as the filament is fed into the liquefier. Assuming the molten polymer inside the liquefier is an incompressible fluid, and that the flow is laminar, the change in the polymer melt volume inside the liquefier is given by Equation (4).

This is the same as the mass balance considering the constant density () of the molten polymer:

where is the mass flow rate, i.e., , and is the volumetric flow rate:

Assuming constant polymer density within the liquefier, and since polymer flow, in this case, is a single-input–single-output system, the molten polymer volume within the liquefier–nozzle region changes dynamically during transients. This occurs due to melt compressibility, elastic deformation of the incoming filament (“melt cushion”), thermal expansion, and delayed pressure propagation through the melt pool [15,16,40]. As a result, the inflow, , and outflow, , are equal only at steady state. During transients, the difference is captured by the dynamic volume balance in Equation (7):

We can define the resistance and capacitance of the liquefier system according to Equations (8) and (9), respectively.

Rewriting Equation (9) for and substituting into Equation (4), we get

Rewriting Equation (8) for and substituting into Equation (10), we get

Let be the time constant of the liquefier system. Rearranging the terms and taking the limit as 0, we get

Equation (12) serves as differential equation to describe the extrusion dynamics of FFF process. Taking Laplace transform, we get a model structure identical to the first-order process model, as described by Equation (15).

where is the process gain:

Computing Parameters for Analytical Flow Rate Dynamics Model

A typical diameter of the thermoplastic filament used in FFF is 1.75 mm. Considering manufacturing tolerances of +10% and −5%, the process gain is computed to be

where the bounds are as follows: and

The process time constant () is the product of liquefier resistance and the capacitance is defined in Equations (8) and (9), respectively. The bulk modulus () of the polymer melt within the liquefier is given by

where is the volume of the liquefier melt zone and can be computed from Figure 2c. Rearranging Equation (17) for ΔP and substituting it into Equation (9), the capacitance of the liquefier system can be computed as

The bulk modulus () of a material is related to its elastic/Young’s modulus () and Poisson ratio () as follows: . According to data from Torres et al. [41], E = 3500 MPa and = 0.36. The volume of the liquefier, , can be computed by adding the volumes of the three sections of the liquefier, as shown in Figure 2c. For the current setup, = 305.53 . The capacitance of the liquefier () is computed to be 0.0733 .

The liquefier resistance () is given by Equation (8). The pressure drop () inside the liquefier is due to the acceleration of material and frictional forces, with the frictional forces being the dominant phenomenon [2]. The total pressure drop from the nozzle outlet only, i.e., inside the annular section of the nozzle (section corresponding to in Figure 2c) due to frictional forces can be computed by the Hagen–Poiseuille equation. PLA is found to exhibit low shear thinning and is therefore assumed to be Newtonian. The liquefier resistance () can be computed as follows:

where is the diameter of the nozzle opening [mm]. = 0.60 mm for current setup; is the viscosity of the polymer melt inside the nozzle [Pa-s]; is the length of the last annular section of the nozzle; = 1.20 mm for current setup.

It is important to note that is highly sensitive to the temperature distributions inside the nozzle. Based on data from Zhou et al. [42], the viscosity of molten PLA can vary from approximately 200 to 1000 Pa-s for the temperature range 220–190 °C, respectively. The liquefier resistance () is computed to be 0.0754 to 0.3772 - for = 200 to 1000 Pa-s, respectively. Finally, using Equations (18) and (19), the bounds for the time constant () is computed to be 0.0055 to 0.0276 s for the current setup. It is important to note that small changes in are expected due to the complexity of the thermal distribution within the liquefier and the amount and duration of melting in the liquefier, in addition to the complex behavior of the thermoplastic material.

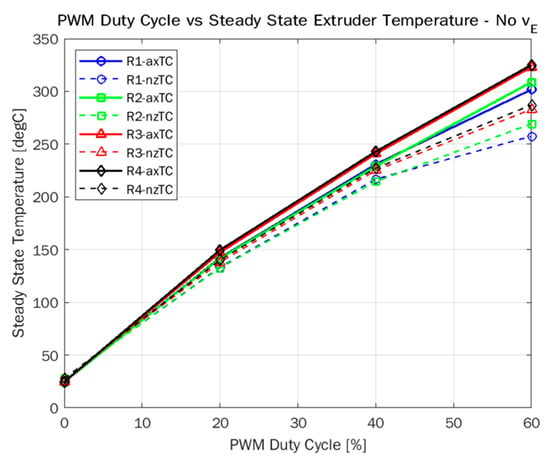

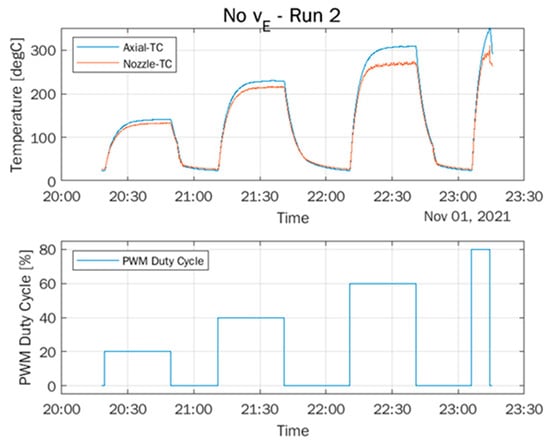

2.2. Temperature Flow Rate Dynamics

The temperature distribution inside the liquefier and the output temperature of the polymer melt exiting the nozzle is a complex function of many factors, including material properties, liquefier geometry, residence time, shear, frictional forces, and the input volumetric flow rate of the filament into the liquefier. Because of the dynamic complexity of the system, it is not feasible to derive a model from the fundamental principles. Therefore, experimental temperature data are taken to develop an empirical model. Based on prior knowledge of the process, the input filament feed rate () directly impacts since the temperature distribution inside the nozzle becomes less homogeneous at higher , leading to a lower . Thus, will be used as an input in addition to the heater PWM duty cycle () to develop an empirical model for temperature dynamics. To test for the linearity of the temperature dynamics, open loop step tests were performed, wherein the was increased from 0 to 60% in 20% increments and the resulting steady-state liquefier temperatures were recorded. Figure 3 shows the results of open loop step tests, and within the FFF operating temperature range (180 °C to 300 °C), the temperature dynamics are found to be linear.

Figure 3.

Results of open loop temperature testing—establishing relationship between heater PWM duty cycle (D) and steady-state temperatures and .

3. Experimental Testbed and Data Acquisition

3.1. Robotic FFF Testbed

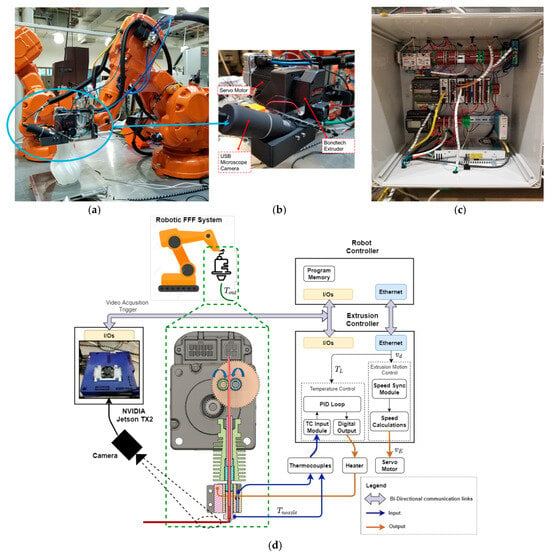

We build upon our previous work on the development of a fully functional robotic FFF testbed [43], in which real-time synchronization between robot motion and the extrusion controller was achieved through two primary mechanisms: (1) transmitting space-variant process parameters via TCP/IP sockets in real time, and (2) implementing analog and digital I/O interfacing to ensure that extrusion velocity and deposition velocity were closely matched, based on an analytical process model.

Building on this platform, our subsequent work focused on engineering and instrumentation of the robotic FFF testbed with additional sensors to gain deeper insight into the dynamics of the FFF process. A K-type thermocouple (McMasterCarr-9251T75, Elmhurst, IL, USA) was installed at the nozzle hex region to provide accurate in-nozzle polymer melt temperature measurements. A current sensor (Sparkfun Current sensor breakout ACS723, Niwot, CO, USA) was added to monitor power consumption by the hot-end’s resistive heating element. The extrusion system was upgraded with a Bondtech BMG extruder (Bondtech BMG IDGA, Malmö, Sweden) featuring dual gripping gears and a closed-loop servo motor (Clearpath CPM-SDSK integrated servo motor, Ham Lake, MN, USA) with torque-feedback capability, enabling improved extrusion reliability and indirect monitoring of filament feed force.

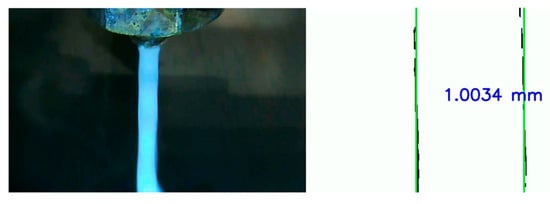

The robotic FFF testbed, shown in Figure 4, was also equipped with a microscope camera (Jiusion USB micrscope camera 40× to 1000×, Shenzhen, China). Using this setup, an image-based measurement technique was developed to measure extrusion width, with ±0.080 mm accuracy validated against caliper measurements. This capability enabled real-time estimation of volumetric flow rate via vision-based sensing, as demonstrated in our previous work [44]. A custom Robust Extrusion Width Recognizer (REXR) algorithm based on OpenCV libraries was developed to process the video data and generate accurate extrusion width and flow rate measurements. Video acquisition was triggered via a digital I/O signal between the PLC of the robotic FFF system and a Nvidia Jetson TX2 board (Santa Clara, CA, USA), with trigger timing embedded into the robot program during toolpath generation based on the (x, y) coordinates of the deposition path. Figure 5 shows the sample output from the vision-based measurement system.

Figure 4.

(a) Robotic FFF testbed; (b) close-up view of vision-based measurement system; (c) control system for extrusion control and synchronization with robot motion; (d) overview of architecture and signal flow for the robotic FFF testbed.

Figure 5.

Output from vision-based measurement system. Left: captured frame; right: measured extrusion width.

This combined sensing, actuation, and control framework provided a high-resolution, synchronized dataset of motion commands, extrusion states, and process measurements, forming the basis for the system identification experiments described in the following section.

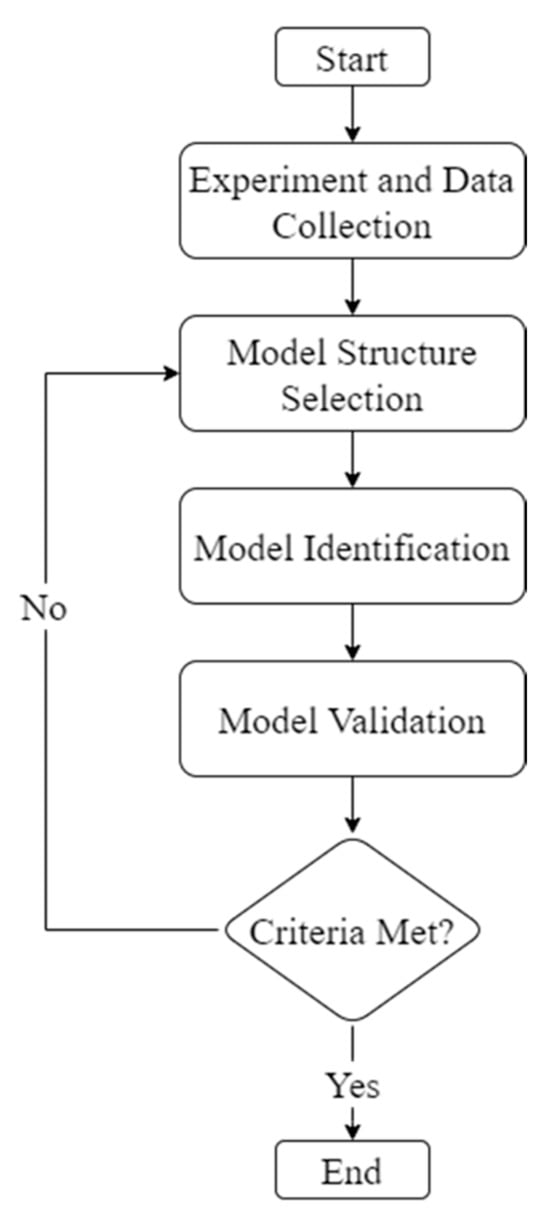

3.2. System Identification Process

System identification is a methodology for building mathematical models of dynamic systems using measurements of the input and output signals of the system. The general workflow of a system identification process is shown in Figure 6. The process of system identification involves the following steps: (1) designing appropriate excitation experiments; (2) collecting high-quality synchronized input–output data; (3) applying estimation methods to derive models in the chosen structure (e.g., transfer functions or state space representations); (4) validating the models against separate datasets to determine whether the model is adequate for the application requirements. To obtain a reliable model of the FFF process, the measured data must adequately reflect the system’s dynamic behavior. The accuracy of the identified model therefore depends directly on the quality of the acquired data, which in turn is dictated by the experimental design. Model selection in the identification workflow was based on three criteria: the suitability of the model structure for control implementation, the physical interpretability of the process–model parameters, and the model accuracy, as quantified using the NMRSE metric. An NMRSE fit of at least 85% was used as the acceptance threshold.

Figure 6.

System identification process workflow.

3.3. Experimental Design for Collecting Input–Output Data for System Identification Process

The experimental design for estimating the dynamical model of the FFF process involves printing a single-walled test specimen subject to excitations from two inputs: (i) the duty cycle () of the pulse width modulated (PWM) signal that controls the heater in the liquefier block; (ii) the linear input velocity of the filament into the liquefier ().

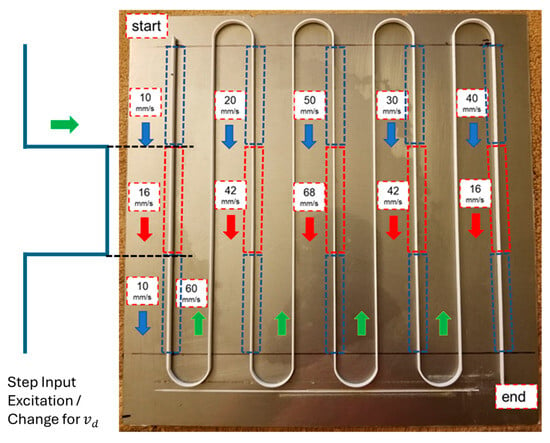

3.3.1. Test Specimen Design and Input Excitation/Step Change

The test specimen consists of continuous paths with regions of varying deposition speeds to exercise the commonly used printing speeds of the FFF process. The printed test specimen and the locations of the step input excitations/changes in the deposition velocity () are shown in Figure 7. It is important to note that deposition velocity () and extruder velocity () are related through the road geometry model given by Equation (20); additionally, the commanded step changes in also result in step changes in , maintaining the requested road geometry.

Figure 7.

Printed test specimen for FFF system identification. Blue and red arrows represent controlled changes or step excitations to while light green arrow represents fixed for non-measuring moves.

The single-wall test specimen was printed using White PLA (Prusament PLA White, Prusa Polymers [45]) material with an extrusion width of 1 mm and a layer height of 0.20 mm, comprising 20 layers in height (4 mm). The specimen consists of five equal-length (200 mm) regions that are printed at varying deposition speeds starting from 10 mm/s up to 50 mm/s incrementing 10 mm/s. Step changes in occur at the middle of each of these five sections and the magnitude of step change varies across the five sections. These five sections are printed from the front to the back of the print bed so that the printing path is visible to the instrumented vision camera and allows for real-time extrusion width and thus polymer flow rate () measurements.

The step changes in the PWM duty cycle () are commanded at the beginning of every fourth layer starting from layer 5, i.e., layers 5, 9, 13, and 17. It is important to note that the test specimen is printed under open-loop temperature conditions, i.e., there is no feedback control of hot-end temperature. Prior experiments were performed to identify the relationship between and steady-state hot-end temperature and the results are provided in Figure 3. A PWM duty cycle of 33% resulted in a steady-state hot-end temperature of 210 °C and was used as the starting point while printing the test specimen.

3.3.2. Output and Measurement

The two outputs of interest are the following: (i) the melt temperature of the polymer exiting the nozzle () and (ii) the output polymer flow rate (). With the existing hardware setup, there are two possible measurements for : (i) temperature measured using instrumented nozzle thermocouple, hereon known as , and (ii) temperature measured using the axial thermocouple, hereon known as . An important distinction between these two measurements is the location of the thermocouple sensors with respect to the molten polymer. comes from a thermocouple mounted axially parallel to the nozzle, but not in contact with the nozzle, and is mounted within the same liquefier block that nozzle screws on to. This is the common location in the majority of existing extruders in the market today. comes from a specially instrumented thermocouple that is embedded into the nozzle and is in actual contact with the nozzle wall and molten polymer inside the nozzle. provides the closest temperature measurement to the polymer melt both inside and when exiting the nozzle. Both these sensors are connected to the PLC, and the temperature measurements are sampled at 20 Hz or every 50 ms. is calculated from vision-based extrusion width measurements processed on the Nvidia Jetson TX2 board and details of instrumentation and measurement can be found in our previous work [44].

3.3.3. Data Synchronization for Output Datasets

Since there are two sources of data acquisition, one for each output of interest ( and ), there is a need to synchronize the data collection to a common clock. This is achieved through digital I/O interfacing between PLC and Nvidia Jetson TX2 board that allowed PLC to trigger video acquisition and measurements on the TX2 board. Each data sample is timestamped with respect to local clocks in both the devices. These timestamps are later used for offline data processing and synchronization to create datasets for the system identification process. It is important to note that the data collection for is carried out continuously in the PLC for the entire test specimen, while the data collection for is only performed during the printing of the five regions for every layer, starting from layer 5, as shown in Figure 7. This results in a total of 5 × (20−4) = 80 multi-experiment datasets for .

4. Data-Driven System Identification for FFF

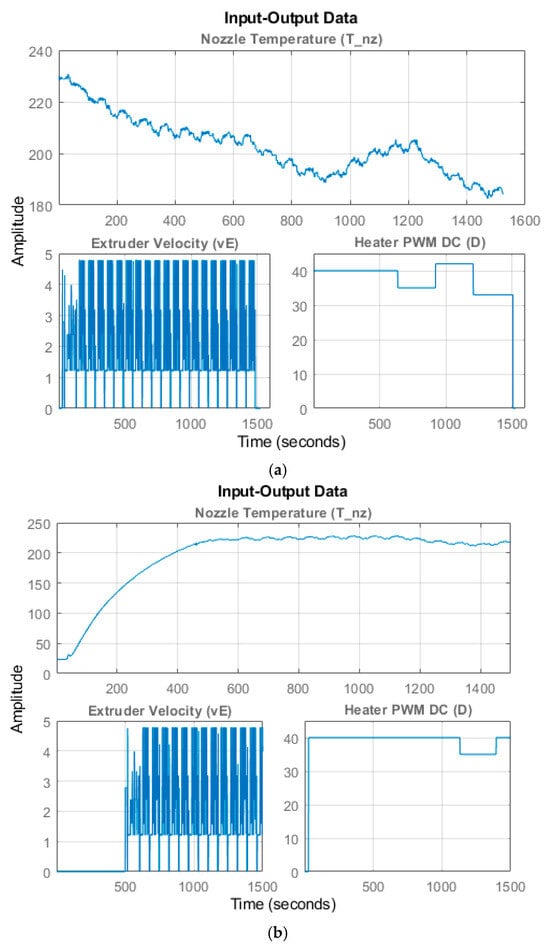

The FFF process’s MIMO model can be segmented into two models, one for each of the outputs: (i) An SISO model for flow rate () dynamics and (ii) an MISO model for temperature () dynamics, as shown in Figure 8a. Examples of the resulting input–output data for the MISO + SISO model structures are shown in Figure 8b,c, respectively. Figure 8b presents sample data used for identifying the MISO temperature model, where the open-loop response of the nozzle thermocouple measurement is recorded under controlled variations of heater PWM duty cycle and the filament input velocity . The temporary decrease in temperature between approximately 1700 s and 2900 s corresponds to the onset of extrusion at a fixed feed velocity, which lowers the melt temperature. Subsequent increases in reflect step changes in heater PWM, applied to excite the system for model identification. Similarly, Figure 8c shows a representative SISO dataset of polymer flow rate versus extruder velocity, used to estimate the flow-rate dynamics model, where step changes in are applied to generate informative excitation for system identification. Figure 8 and Figure 9 present representative input–output subsets extracted from the five-speed test specimen in Figure 3; these are used, respectively, for temperature (MISO) model estimation and flow-rate (SISO) model validation.

Figure 8.

(a) FFF process model, represented as combination of MISO + SISO models for and ; (b) MISO data for output temperature (); (c) SISO data for flow rate ().

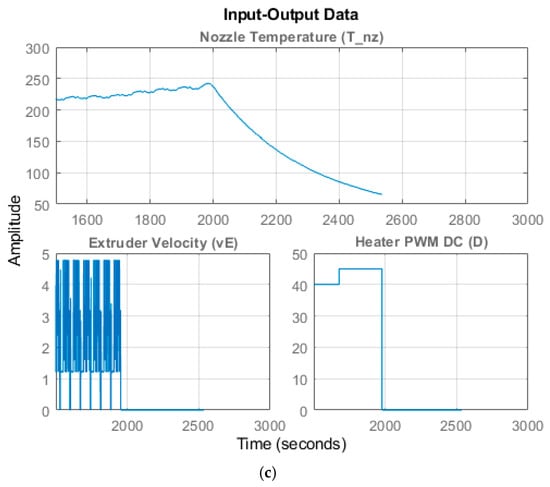

Figure 9.

Validation datasets for temperature () model (a) MISO Validation Dataset 1 (b) MISO Validation Dataset 2 (c) MISO Validation Dataset 3.

4.1. Model Structure Selection

Selecting a suitable model structure is the most crucial step in the system identification workflow since the quality of the resulting model greatly depends on the chosen model structure.

4.1.1. Temperature Dynamics

Since we do not have an analytical candidate model structure for temperature dynamics, several commonly used standard model structures were explored during the model estimation phase, including the first order process model with dead time (FOPDT), first- and second order transfer function models, and a first order state space model.

4.1.2. Flow Rate Dynamics

Based on analytical modeling of flow rate dynamics, which resulted in a first order process model-like structure (Equation (15)), a decision was made to use a first order process model with dead time (FOPDT) as the candidate model structure during the model estimation phase of the system identification process. This enabled a comparison of the estimated free parameters of the model and those computed analytically.

Process models are low-order transfer function models with static gain, time constants, and input–output delays. Process models are popular for describing system dynamics in many industries and are applicable in various production environments. The advantages of these models are that they are simple, they support transport delay estimation, and their model coefficients are easily interpretable as poles and zeros.

4.2. Model Estimation and Validation

4.2.1. Multi-Input–Single Output (MISO) Temperature Model

As stated earlier, there are two possible measurements for with the existing setup: (i) and (ii) . Since is measured using a thermocouple embedded into the nozzle, it provides the temperature closest to the output of interest, i.e., the temperature of the polymer melt within the nozzle and that exiting the nozzle compared to temperatures provided by the axial thermocouple (). The system identification of temperature dynamics uses measurements to describe .

A MATLAB system identification toolbox (R2021a) was used for the model estimation and validation. The input–output experimental data for describing temperature dynamics shown in Figure 8b was used as the estimation dataset. For process model and transfer function models, the resulting model structure for describing temperature dynamics can be represented using Equation (21):

where , and .

The FOPDT model structure for one pole and delay term is given by Equation (22):

where is process gain, is process time constant, and is the dead time.

The transfer function models describe the relationship between the inputs and outputs of a system using a ratio of polynomials. The model order is equal to the order of the denominator polynomial. Three different transfer function models, with one pole and no zeros, two poles and no zeros, one pole and one zero, and two poles with one zero, were used as candidate model structures for estimation.

For the state space model, the optimal order was identified using the Model Order Selection window, which displays the relative measure of how much each state contributes to the input–output behavior of the model (log of singular values of the covariance matrix). The optimal model order was identified to be 1, i.e., one state, and C was forced to be 1 so that and . The generic structure of a state space model with disturbance component is shown in Equation (23):

Figure 9 shows the three datasets that were used for validating the estimated empirical models for describing the temperature dynamics. In each dataset, controlled excitations are applied to the heater PWM duty cycle and the filament input velocity , and the corresponding open-loop response of the nozzle thermocouple measurement is recorded. The small oscillations and local peaks in arise from the start–stop nature of short extrusion segments used to excite the system, during which variations in convective heat removal momentarily perturb the melt temperature. In general, increases in reduce because the incoming filament has less residence time to absorb heat before exiting the nozzle, whereas increases in heater PWM duty cycle raise the by supplying additional thermal energy.

Table 1 summarizes all the different models obtained using the system identification process for describing the temperature dynamics, the fit% to estimation and validation datasets. The fit, in this case, is a normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) [46] that indicates how well the simulated or predicted model response matches the measurement data; this is given by Equation (24):

where is the experimentally obtained physical measurement data, is the simulated or predicted output from the identified model, and is mean of . indicates the 2-norm of a vector.

Table 1.

Estimated models for FFF temperature dynamics using Tnz measurements and NRMSE fit%.

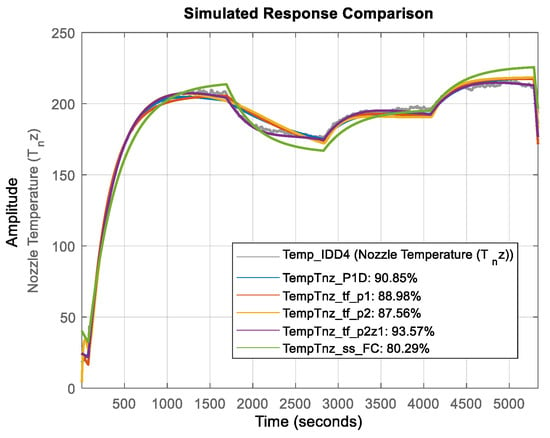

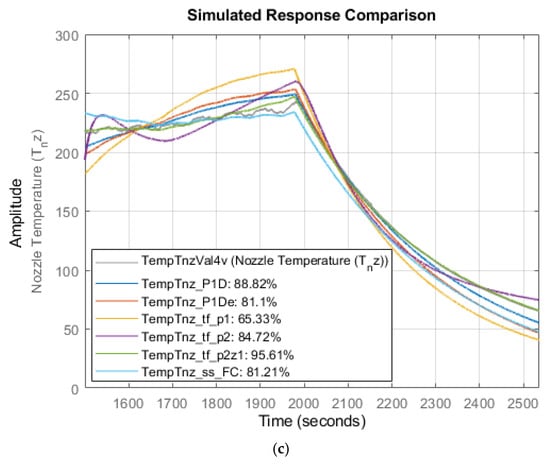

Figure 10 provides the results of model estimation phase where obtained by simulation of estimated empirical models are overlayed on actual experimental values. The percentages in the legend represent the NRMSE values computed using Equation (24).

Figure 10.

Results of model estimation for temperature dynamics: simulated vs. experimental temperatures—all model structures are listed Table 1.

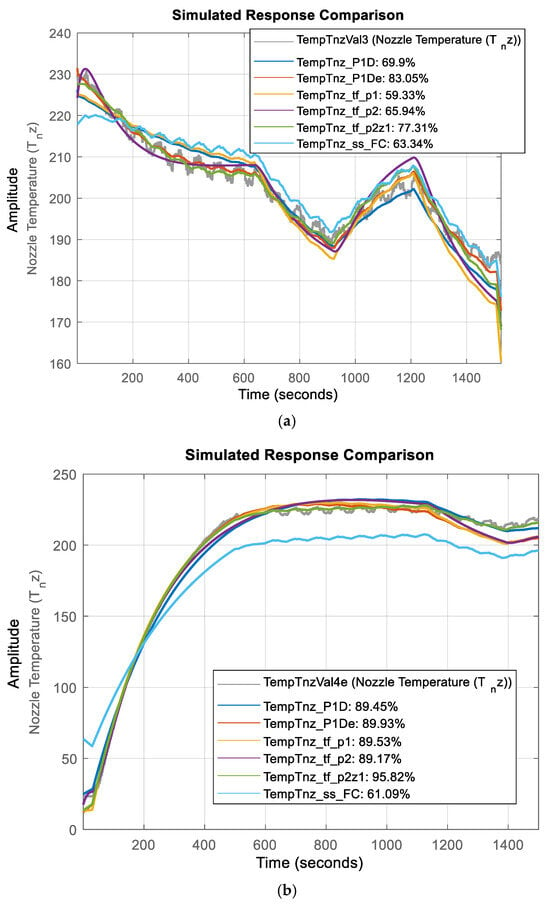

Figure 11 provides the results of model validation phase where values, obtained by the simulation of estimated empirical models, are overlayed on actual experimental values from the three validation datasets (Figure 9). Since the experimental values used in model validation are different from those used in model estimation, validation tests were used to obtain information on how well the simulated or predicted model response matches the new, unseen measurement data and alerts the operator to over-fitting problems in the estimated models.

Figure 11.

Results of model validation for temperature dynamics: simulated vs. experimental temperatures—all model structures are listed Table 1, against (a) validation dataset 1 (b) validation dataset 2 (c) validation dataset 3.

Based on the results in Table 1, Figure 10 and Figure 11, the top three models for describing temperature dynamics in the FFF process are as follows: (i) second-order transfer function model with two poles and one zero—TempTnz_tf_p2z1; (ii) first-order process model with dead time—TempTnz_P1D; (iii) first-order process model with dead time—TempTnz_P1De. The difference between models TempTnz_P1D and TempTnz_P1De is in the estimation data used to build the models. The estimation data used for model TempTnz_P1De are a subset of those used for TempTnz_P1D. The comparison of the model-simulated temperatures against the actual experimental temperatures across all estimation and validation datasets shows very good agreement and is an attestation to the ability of the estimated models to adequately model the temperature dynamics in the FFF process.

While the performance of the second-order transfer function model is good across all the estimation and validation sets, there is room for improvement for the first-order process models. From an implementation point of view, first-order process models are attractive due to their simple model structure, with coefficients that are easy to interpret and relate to the physical process. To verify with confidence that the linear part of temperature dynamics is sufficiently modeled by the process models and thereby account for the unmodelled part of the data, we can use other model validation techniques such as residual analysis.

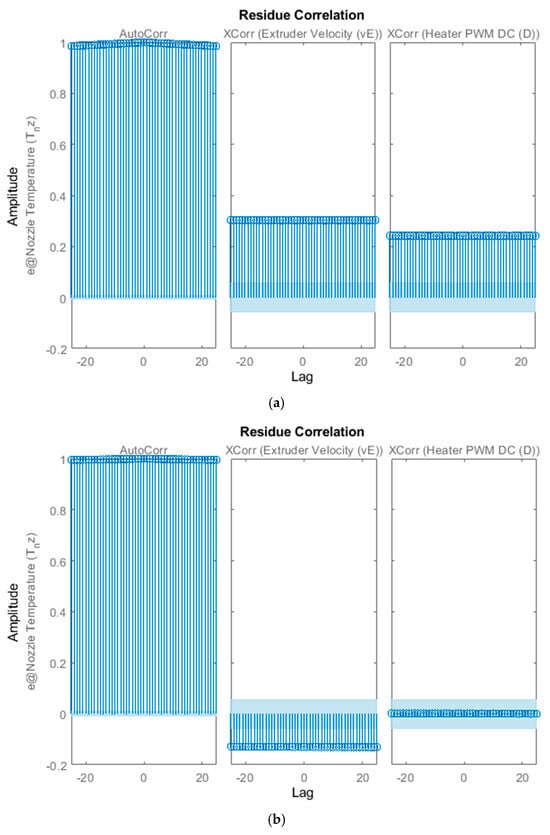

Residuals are the differences between the one-step-predicted output from the model and the measured output from the validation dataset. Thus, residuals represent the portion of the validation data not explained by the model. The residual analysis consists of two tests: the whiteness test and the independence test. According to the whiteness test criteria, a good model has the residual autocorrelation function inside the confidence interval of the corresponding estimates, indicating that the residuals are uncorrelated. According to the independence test criteria, a good model has residuals uncorrelated with past inputs. Evidence of correlation indicates that the model does not describe how part of the output relates to the corresponding input. For example, a peak outside the confidence interval for lag means that the output that originates from the input is not properly described by the model.

Figure 12 illustrates the results of the residual analyses, including the whiteness and independence tests, for the second-order transfer function model (Temp_Tnz_tf_p2z1) and the first-order process model (TempTnz_P1D). As is evident from the figure, the cross-correlation between the residuals and the inputs is low for the process models, while the autocorrelation among the residuals is high for both the models. The high autocorrelation between the residuals and the inputs in the second-order transfer function model indicates that the model is missing some essential dynamics. The process models have a lower cross-correlation between the residuals and the inputs but high autocorrelation among the residuals. This indicates that the estimated models are missing dynamics in the disturbance path and not in the essential dynamics. The remaining non-modeled dynamics tend to be random in nature and could not be captured by the linear models; therefore, we can account for these disturbances by fitting a dynamic and disturbance model simultaneously during the model estimation phase. The MATLAB system identification toolbox (R2021a) enables us to account for these disturbances during the model estimation phase, only for process models. The disturbance dynamics usually fit to the first- or second-order Auto Regressive Moving Average (ARMA) model. The model structure for a process model with the disturbance component is given by Equation (25):

Figure 12.

Residual analysis for (a) second-order transfer function model—TempTnz_tf_p2z1; (b) first-order process model—TempTnz_P1D.

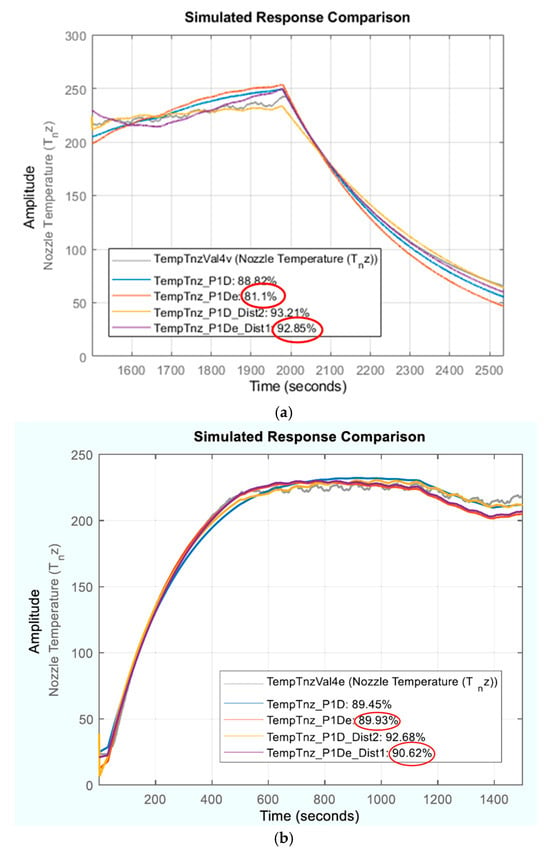

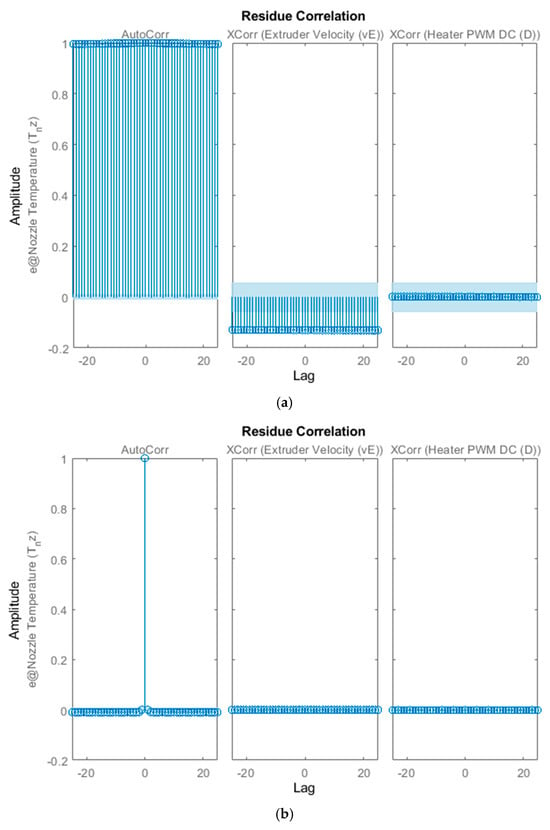

Two additional process models with disturbance components were estimated: (i) a second-order ARMA disturbance model for TempTnz_P1D called “TempTnz_P1D_Dist2”; (ii) a first-order ARMA disturbance model for TempTnz_P1De called “TempTnz_P1De_Dist1”. The performances of these models compared to those of their original counterparts, without disturbance components, on all estimation and validation datasets are provided in Table 2. Figure 13 compares the responses of the process models with and without disturbance components with actual experimental values across all validation datasets. As evident from Table 2 and Figure 13, accounting for random disturbance during model estimation results in improved NRMSE fit values and validates the idea that unmodeled dynamics in the original process models are in fact due to random disturbances. This can be further verified by looking at the results of residual analysis for process models, with disturbance components shown in Figure 14. As evident from the whiteness and independence plots in the residual analyses, the autocorrelation among the residuals and the cross-correlation between the residuals and inputs are very low, which is an indication of good model fidelity.

Table 2.

Process models with disturbance components for modeling temperature dynamics and NRMSE fit %.

Figure 13.

Results of model validation for temperature dynamics: simulated vs. experimental temperatures—all model structures listed Table 2 against (a) validation dataset 1 (b) validation dataset 2. Red circles highlight improvement in model Fit% with addition of disturbance component during model estimation.

Figure 14.

Residual analysis for (a) first-order process model—TempTnz_P1De; (b) first-order process model (TempTnz_P1De) with a first-order ARMA disturbance model—TempTnz_P1De_Dist1. Addition of disturbance components during model estimation phase results in very low autocorrelation among residuals and low cross-correlation between residuals and inputs, which is an indication of good model fidelity.

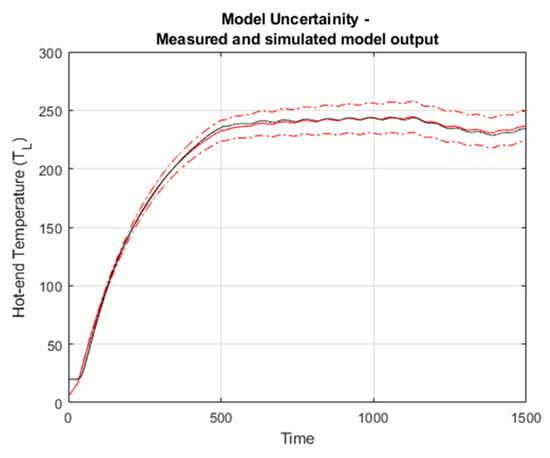

The model “TempTnz_P1De_Dist1” is selected as the final choice for describing the temperature dynamics in the FFF process for the given setup. Any estimated model has a degree of uncertainty, which affects the reliability of the various model properties. Figure 15 shows uncertainty in the response of model “TempTnz_P1De_Dist1” in the time domain for validation dataset 2 using 99% confidence bounds (2.57 standard deviations). The uncertainty region is marked by two dash–dotted lines, one on either side of the nominal model curve, with the same color as the curve. The statistical interpretation is that with 99% probability; the true system response is found within the marked confidence region.

Figure 15.

Model uncertainty—99% confidence bounds for model TempTnz_P1De_Dist1 on validation dataset 2.

In this study, the melt temperature was measured using two thermocouples: a liquefier-block thermocouple, , located near the heating element, and a nozzle-embedded thermocouple, , positioned in direct contact with the molten polymer. Both signals exhibit similar transient trends; however, consistently reports a higher temperature and responds more rapidly to heater inputs due to its proximity to the heat source, while more accurately reflects the true melt temperature at the nozzle exit. Although the two measurements differ by a consistent offset, this does not affect the system-identification methodology. Using either temperature source produces models with comparable dynamic behavior, with differences manifesting only in the steady-state gain and bias terms. Because most commercial FFF systems provide only , the modeling framework presented here remains widely applicable, and calibrated corrections can be used when an estimate of the nozzle-level melt temperature is required. Figure 16 compares the nozzle temperature, , with the liquefier-block temperature, , showing that the two measurements follow similar dynamic behavior, while maintaining a consistent offset resulting from their different sensor locations.

Figure 16.

Comparison of the nozzle thermocouple temperature, , and the liquefier-block temperature, , under step changes in the heater PWM duty cycle.

4.2.2. Single-Input–Single-Output (SISO) Flow Rate Model

Analytical modeling of flow rate dynamics discussed in Section 2.1 resulted in a first-order process model-like structure for describing the relationship between the linear filament feed input rate into the liquefier () and the output polymer volumetric flow rate () given by Equation (15). Based on this knowledge of process dynamics, the model selection stage during the system identification process was limited to first-order process models whose structure is described by Equation (22). The printed test specimen used for system identification consists of five regions of varying steps changes in per layer as shown in Figure 5. The resulting input–output data for a single region is shown in Figure 8c. There are five such regions per layer and a total of 16 layers resulting in a total of 80 input–output datasets. Of these, 64 were selected and a first-order process model was fit to each of these datasets. The results were further filtered to include only those models which had an NRMSE fit% of greater than 70%. Table A1 in Appendix A provides a summary of estimated model parameters () for the filtered set.

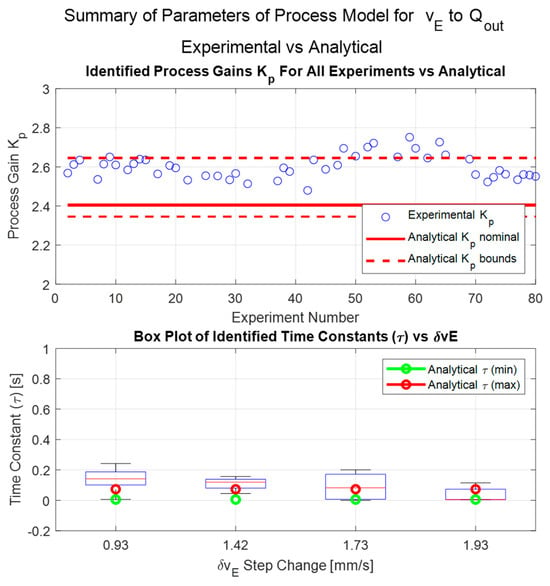

Figure 17 shows comparison between analytically computed model parameters (Section 2.1) and those estimated from the system identification process. The bounds for are calculated based on 10% variation in filament diameter according to Equation (16). There is a good agreement between model parameters computed analytically and those estimated empirically using system identification. This result further validates the analytical modelling approach used for estimating the parameters of the process model.

Figure 17.

Flow rate dynamics system identification—comparing analytical and empirical model parameters.

There is some scatter in the estimated time constant () parameter as seen from the box plot in Figure 17. This can be attributed to three reasons: (i) variations and noise in the extrusion width measurements and resulting output volumetric flow rate measured using vision system; (ii) small changes in are expected due to complex thermal distribution within the liquefier, amount, and duration of melt in the liquefier and complex behavior of the thermoplastic material; (iii) small time delays between internal clocks of PLC and Nvidia Jetson TX2 devices that lead to offset timestamps in the recorded data.

A first-order process model for flow rate dynamics is given by Equation (26). The model parameters used are averaged values of the estimated model parameters in the filtered dataset.

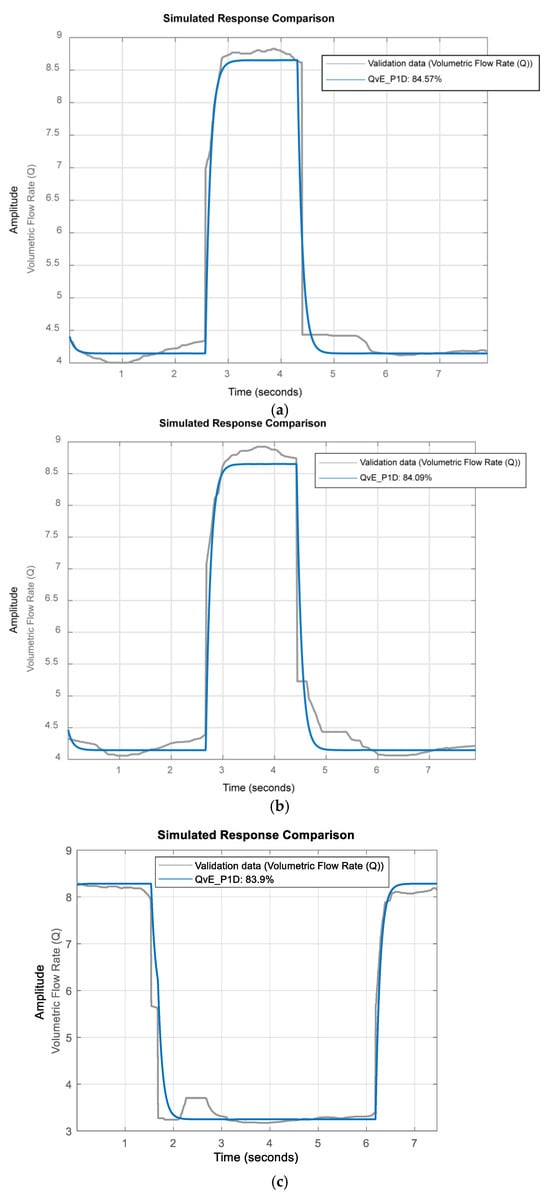

Figure 18 illustrates the performance of the process model described by Equation (26) on various validation datasets. On average, the NRMSE fit% ranges from 78% to 84% across all validation datasets. While the linear time-invariant (LTI) process model’s performance is acceptable, the remaining difference between experimental data and model response can be attributed to measurement noise in vision-based road width measurements and nonlinearities in extrusion dynamics arising from varying polymer melt properties as temperatures and (operating points) change. This is also evident from the scatter in the values as seen in Figure 17. Overall, the process model estimated for flow rate dynamics shows a very good generalized performance on new unseen data as part of the model validation effort shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Results of model validation of flow rate dynamics process model for (a) validation dataset 1 (b) validation dataset 2 and (c) validation dataset 3.

Although PLA was selected for the experimental study due to its stable and repeatable thermal behavior, the modeling and system-identification framework developed in this work is fully material-agnostic. The structure of the analytical model and the SysID procedure does not depend on any specific polymer; instead, differences between materials appear only in the numerical values of the estimated parameters (e.g., gains, thermal and flow-related time constants). Because the methodology is data-driven and relies solely on experimentally generated input–output data, the same identification approach applies directly to engineering polymers as well as high-performance thermoplastics. Consequently, the models and identification strategies presented here provide a general foundation for future closed-loop control development across the full range of materials used in FFF.

5. Conclusions

In this work, modeling of FFF process dynamics was investigated through both analytical modeling and data-driven system identification, enabled by the process sensing capabilities of a previously developed robotic FFF testbed. The FFF process was cumulatively described in terms of temperature and flow rate dynamics, and multiple model structures, including first and second-order transfer functions, process models, and state space representations, were examined. Among these, a first-order process model with a first-order disturbance component was found to best fit the experimental data, achieving strong generalization performance with normalized mean root square error (NRMSE) values exceeding 90%.

A key contribution of this work is the use of multi-source sensor data, including in-nozzle- and block-mounted thermocouples, current sensing, and vision-based extrusion width measurements, to capture coupled temperature–flow rate dynamics. These datasets enabled robust system identification and validation across operating regimes. Importantly, an analytical process model for polymer flow rate dynamics, derived from first principles, was found to be in close agreement with the empirical model obtained through system identification. The similarity of process parameters (gain and time constant) across both approaches underscores the physical interpretability and reliability of the identified models.

Looking forward, this research opens several fruitful opportunities. First, implementation and testing of control algorithms on the robotic FFF hardware will be an important next step toward realizing closed-loop regulation of melt temperature and flow rate. Second, extending the modeling framework to account for the thermal history of the process, including the sub-layer temperature of previously deposited material and the influence of part geometry, can enable novel control strategies targeted at maximizing interlayer bonding and overall part strength. These directions represent the natural evolution of the present work toward adaptive, feedback-driven FFF systems capable of achieving consistent, high-performance additive manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and V.V.P.; methodology, R.B.; software, R.B.; validation, R.B. and V.V.P.; formal analysis, R.B.; investigation, R.B.; resources, V.V.P.; data curation, R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B.; visualization, R.B. and V.V.P.; supervision, V.V.P.; project administration, R.B. and V.V.P.; funding acquisition, V.V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM | additive manufacturing |

| ARMA | auto regressive moving average |

| FFF | fused filament fabrication |

| FOPDT | first-order process model with dead time |

| I/O | input–output |

| LTI | linear time invariant |

| MIMO | multi-input–multi-output |

| MISO | multi-input–single-output |

| NRMSE | normalized root mean square error |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PWM | pulse width modulation |

| SS | state space |

| SysID | system identification |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of estimated model parameters of process model for flow rate dynamics across all experiments filtered with fit% > 70%.

Table A1.

Summary of estimated model parameters of process model for flow rate dynamics across all experiments filtered with fit% > 70%.

| Experiment Number | ] | [s] | ] | NRMSE Fit % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2.5683 | 0.0064 | 0.001122 | 203.55 | 89.60 | 1.7313 |

| 3 | 2.6122 | 0.0968 | 0 | 203.29 | 70.17 | 1.4253 |

| 4 | 2.6351 | 0.0062 | 0 | 201.17 | 87.50 | 0.9373 |

| 7 | 2.5360 | 0.1417 | 0 | 203.17 | 74.41 | 1.7313 |

| 8 | 2.6141 | 0.0446 | 0 | 202.68 | 73.52 | 1.4253 |

| 9 | 2.6508 | 0.0060 | 0 | 200.39 | 84.60 | 0.9373 |

| 10 | 2.6098 | 0.0728 | 0 | 200.21 | 83.98 | 1.9349 |

| 12 | 2.5847 | 0.1079 | 0 | 202.54 | 79.64 | 1.7313 |

| 13 | 2.6160 | 0.1199 | 0 | 201.62 | 70.75 | 1.4253 |

| 15 | 2.6356 | 0.0720 | 0 | 200.01 | 83.02 | 1.9349 |

| 17 | 2.5638 | 0.1739 | 0 | 201.78 | 73.67 | 1.7313 |

| 19 | 2.6070 | 0.0076 | 0 | 199.42 | 87.40 | 0.9373 |

| 20 | 2.5947 | 0.0053 | 0 | 199.65 | 91.42 | 1.9349 |

| 22 | 2.5324 | 0.1413 | 0 | 200.42 | 73.27 | 1.7313 |

| 25 | 2.5548 | 0.1157 | 0 | 195.25 | 79.75 | 1.9349 |

| 27 | 2.5538 | 0.0069 | 0 | 195.79 | 88.56 | 1.7313 |

| 29 | 2.5337 | 0.1855 | 0 | 191.40 | 71.29 | 0.9373 |

| 30 | 2.5665 | 0.0049 | 0 | 191.43 | 90.78 | 1.9349 |

| 32 | 2.5137 | 0.1294 | 0 | 191.53 | 77.10 | 1.7313 |

| 37 | 2.5280 | 0.1313 | 0 | 189.37 | 71.85 | 1.7313 |

| 38 | 2.5950 | 0.1565 | 0 | 189.00 | 73.04 | 1.4253 |

| 39 | 2.5762 | 0.2002 | 0 | 186.85 | 76.82 | 0.9373 |

| 42 | 2.4797 | 0.1826 | 0 | 188.63 | 71.65 | 1.7313 |

| 43 | 2.6355 | 0.1571 | 0 | 189.37 | 71.86 | 1.4253 |

| 45 | 2.5876 | 0.0055 | 0 | 189.06 | 91.94 | 1.9349 |

| 47 | 2.6088 | 0.0329 | 0 | 193.71 | 71.96 | 1.7313 |

| 48 | 2.6948 | 0.0554 | 0 | 194.13 | 72.15 | 1.4253 |

| 50 | 2.6548 | 0.0047 | 0 | 193.66 | 91.66 | 1.9349 |

| 52 | 2.7012 | 0.1907 | 0 | 197.24 | 79.89 | 1.7313 |

| 53 | 2.7214 | 0.0886 | 0 | 197.59 | 72.30 | 1.4253 |

| 57 | 2.6508 | 0.2214 | 0 | 200.22 | 73.87 | 1.7313 |

| 59 | 2.7516 | 0.1456 | 0 | 198.58 | 81.92 | 0.9373 |

| 60 | 2.6949 | 0.0746 | 0 | 198.66 | 83.65 | 1.9349 |

| 62 | 2.6453 | 0.0996 | 0 | 199.91 | 85.23 | 1.7313 |

| 64 | 2.7267 | 0.0820 | 0 | 194.79 | 80.43 | 0.9373 |

| 65 | 2.6612 | 0.0047 | 0 | 193.91 | 93.09 | 1.9349 |

| 69 | 2.6394 | 0.1747 | 0 | 188.82 | 74.72 | 0.9373 |

| 70 | 2.5606 | 0.0783 | 0 | 187.82 | 85.92 | 1.9349 |

| 72 | 2.5230 | 0.1894 | 0 | 187.51 | 76.56 | 1.7313 |

| 73 | 2.5468 | 0.1325 | 0 | 187.05 | 75.05 | 1.4253 |

| 74 | 2.5822 | 0.1614 | 0 | 184.37 | 71.11 | 0.9373 |

| 75 | 2.5624 | 0.0045 | 0 | 183.12 | 91.06 | 1.9349 |

| 77 | 2.5343 | 0.2421 | 0 | 183.89 | 75.92 | 1.7313 |

| 78 | 2.5612 | 0.1270 | 0 | 182.38 | 70.63 | 1.4253 |

| 79 | 2.5580 | 0.0077 | 0 | 180.30 | 84.71 | 0.9373 |

| 80 | 2.5514 | 0.0052 | 0 | 180.78 | 91.37 | 1.9349 |

References

- Bellini, A.; Güçeri, S.; Bertoldi, M. Liquefier Dynamics in Fused Deposition. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2004, 126, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronvoll, S.A.; Popp, S.; Elverum, C.W.; Welo, T. Investigating Pressure Advance Algorithms for Filament-Based Melt Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Theory, Practice and Simulations. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2019, 25, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertay, D.S.; Yuen, A.; Altintas, Y. Synchronized Material Deposition Rate Control with Path Velocity on Fused Filament Fabrication Machines. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesser, P.; Post, B.; Roschli, A.; Carnal, C.; Lind, R.; Borish, M.; Love, L. Extrusion Control for High Quality Printing on Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM) Systems. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressure Advance|Duet3D Documentation. Available online: https://docs.duet3d.com/en/User_manual/Tuning/Pressure_advance (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Pressure Advance—Klipper Documentation. Available online: https://www.klipper3d.org/Pressure_Advance.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Linear Advance|Marlin Firmware. Available online: https://marlinfw.org/docs/features/lin_advance.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Percoco, G.; Arleo, L.; Stano, G.; Bottiglione, F. Analytical Model to Predict the Extrusion Force as a Function of the Layer Height, in Extrusion Based 3D Printing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Ramani, K.S.; Okwudire, C.E. Accurate Linear and Nonlinear Model-Based Feedforward Deposition Control for Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Strong, R.; Gold, S.A. A Review of Melt Extrusion Additive Manufacturing Processes: I. Process Design and Modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Gold, S.A. A Review of Melt Extrusion Additive Manufacturing Processes: II. Materials, Dimensional Accuracy, and Surface Roughness. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, B.; Cui, C.; Guo, Y.; Yan, C. A Critical Review of Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing Technology in Manufacturing Polylactic Acid Parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 2877–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaqour, B.; Abuabiah, M.; Abdel-Fattah, S.; Juaidi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Abuzaina, W.; Qarout, M.; Verleije, B.; Cos, P. Gaining a Better Understanding of the Extrusion Process in Fused Filament Fabrication 3D Printing: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 114, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Fused Filament Fabrication Process: A Review of Numerical Simulation Techniques. Polymers 2021, 13, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdeczny, M.P.; Comminal, R.; Pedersen, D.B.; Spangenberg, J. Experimental and Analytical Study of the Polymer Melt Flow through the Hot-End in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, A.R.; Kazmer, D.O.; Peterson, A.M. The Dependency Chain in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Shaft Torque, Infeed Load, Melt Pressure, and Melt Temperature. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 77, 103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Vasiliauskaite, E.; De Kuyper, A.; De Schryver, C.; Vogeler, F.; Desplentere, F.; Ferraris, E. Temperature Analyses in Fused Filament Fabrication: From Filament Entering the Hot-End to the Printed Parts. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 9, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellehumeur, C.; Li, L.; Sun, Q.; Gu, P. Modeling of Bond Formation Between Polymer Filaments in the Fused Deposition Modeling Process. J. Manuf. Process. 2004, 6, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Rizvi, G.M.; Bellehumeur, C.T.; Gu, P. Effect of Processing Conditions on the Bonding Quality of FDM Polymer Filaments. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2008, 14, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhou, X.; Si, L.; Chen, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. Modeling of Bonding Strength for Fused Filament Fabrication Considering Bonding Interface Evolution and Molecular Diffusion. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 68, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, T.J.; Kazmer, D.O. Prediction of Interlayer Strength in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, A.; Croce, U.; Spotorno, R.; Fenni, S.E.; Cavallo, D. Fused Deposition Modeling of Polyamides: Crystallization and Weld Formation. Polymers 2020, 12, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderegg, D.A.; Bryant, H.A.; Ruffin, D.C.; Skrip, S.M.; Fallon, J.J.; Gilmer, E.L.; Bortner, M.J. In-Situ Monitoring of Polymer Flow Temperature and Pressure in Extrusion Based Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 26, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuchitprasitchai, S.; Roggemann, M.; Pearce, J.M. Factors Effecting Real-Time Optical Monitoring of Fused Filament 3D Printing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 2, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.; Rossi, A.; Senin, N. In-Process Monitoring of Part Geometry in Fused Filament Fabrication Using Computer Vision and Digital Twins. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z. In Situ Monitoring of FDM Machine Condition via Acoustic Emission. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 84, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jin, L.; Yan, Y.; Mei, Y. Filament Breakage Monitoring in Fused Deposition Modeling Using Acoustic Emission Technique. Sensors 2018, 18, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y. A New Approach for Online Monitoring of Additive Manufacturing Based on Acoustic Emission. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lotrakul, P.; San-um, W.; Takahashi, M. The Monitoring of Three-Dimensional Printer Filament Feeding Process Using an Acoustic Emission. In Sustainability Through Innovation in Product Life Cycle Design; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hsieh, S.-J. Thermal Analysis of Fused Deposition Modeling Process Using Infrared Thermography Imaging and Finite Element Modeling. In Proceedings of the SPIE Commercial + Scientific Sensing and Imaging, Thermosense: Thermal Infrared Applications XXXIX, Anaheim, CA, USA, 10–13 April 2017; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10214, p. 1021409. [Google Scholar]

- Malekipour, E.; Attoye, S.; El-Mounayri, H. Investigation of Layer Based Thermal Behavior in Fused Deposition Modeling Process by Infrared Thermography. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 26, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Mesa, R.; Gomez-Gras, G.; Travieso-Rodriguez, J.A.; Garcia-Plana, V. A Comparative Study of the Thermal Behavior of Three Different 3D Printer Liquefiers. Mechatronics 2018, 56, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinwiddie, R.B.; Love, L.J.; Rowe, J.C. Real-Time Process Monitoring and Temperature Mapping of a 3D Polymer Printing Process. In Proceedings of the SPIE Defense, Security, and Sensing, Thermosense: Thermal Infrared Applications XXXV, Baltimore, MD, USA, 30 April–1 May 2013; pp. 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Downey, A.; Yuan, L.; Pratt, A.; Balogun, Y. In Situ Monitoring for Fused Filament Fabrication Process: A Review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.K.; Liu, J.; Roberson, D.; Kong, Z.; Williams, C. Online Real-Time Quality Monitoring in Additive Manufacturing Processes Using Heterogeneous Sensors. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2015, 137, 061007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J.; Kong, Q. Monitoring the Extrusion State of Fused Filament Fabrication Using Fine-Grain Recognition Method. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 125, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbal, O.; Kassab, A.; Ayoub, G.; Mohanty, P.; Pannier, C. System Identification of Fused Filament Fabrication Additive Manufacturing Extrusion and Spreading Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 14–16 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Read, J.R.; Seppala, J.E.; Tourlomousis, F.; Warren, J.A.; Bakker, N.; Gershenfeld, N. Online Measurement for Parameter Discovery in Fused Filament Fabrication. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2024, 13, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomorodi, H.; Landers, R.G. Extrusion Based Additive Manufacturing Using Explicit Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the 2016 American Control Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 6–8 July 2016; pp. 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmer, D.O.; Colon, A.R.; Peterson, A.M.; Kim, S.K. Concurrent Characterization of Compressibility and Viscosity in Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene with Fault Diagnoses. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Cotelo, J.; Karl, J.; Gordon, A.P. Mechanical Property Optimization of FDM PLA in Shear with Multiple Objectives. JOM 2015, 67, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Green, T.B.; Joo, Y.L. The Thermal Effects on Electrospinning of Polylactic Acid Melts. Polymer 2006, 47, 7497–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarinath, R.; Prabhu, V. Integration and Evaluation of Robotic Fused Filament Fabrication System. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 41, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarinath, R.; Prabhu, V. Real-Time Sensing of Output Polymer Flow Temperature and Volumetric Flowrate in Fused Filament Fabrication Process. Materials 2022, 15, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusament PLA Vanilla White 1kg|Original Prusa 3D Printers Directly from Josef Prusa. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/product/prusament-pla-vanilla-white-1kg/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Loss Function and Model Quality Metrics—MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/ident/ug/model-quality-metrics.html (accessed on 22 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).