Abstract

Recent advances in vibration-based pavement assessment have enabled the low-cost monitoring of road conditions using inertial sensors and machine learning models. However, most studies focus on isolated tasks, such as roughness classification, without integrating statistical validation, anomaly detection, or maintenance prioritization. This study presents a unified framework for road roughness severity classification and predictive maintenance using multi-axis accelerometer data collected from urban road networks in Pretoria, South Africa. The proposed pipeline integrates ISO-referenced labeling, ensemble and deep classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost, MLP, and 1D-CNN), McNemar’s test for model agreement validation, feature importance interpretation, and GIS-based anomaly mapping. Stratified cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning ensured robust generalization, with accuracies exceeding 99%. Statistical outlier detection enabled the early identification of deteriorated segments, supporting proactive maintenance planning. The results confirm that vertical acceleration (accel_z) is the most discriminative signal for roughness severity, validating the feasibility of lightweight single-axis sensing. The study concludes that combining supervised learning with statistical anomaly detection can provide an intelligent, scalable, and cost-effective foundation for municipal pavement management systems. The modular design further supports integration with Internet-of-Things (IoT) telematics platforms for near-real-time road condition monitoring and sustainable transport asset management.

1. Introduction

High-quality road infrastructure is essential for safe and efficient transportation, economic growth, and sustainable urban development. However, over time, road surfaces deteriorate due to aging materials, heavy traffic loads, and environmental impacts such as temperature fluctuations and precipitation. From a structural standpoint, rigid pavements (e.g., Portland cement concrete) and flexible pavements (asphalt) exhibit distinct vibration signatures under vehicle loading. Differences in stiffness, joint transfer, and viscoelastic properties alter the spectral content and amplitude of vertical acceleration (accel_z), which may shift classification boundaries. While the present framework did not stratify by pavement type, it remains adaptable to type-specific models or the inclusion of a pavement-type covariate in future deployments. In colder regions, freeze–thaw cycles act as a dominant deterioration mechanism. Repeated moisture ingress and ice lens formation cause scaling and surface cracking, accelerating roughness progression. This degradation increases road roughness, leading to reduced ride comfort, elevated maintenance costs, and heightened safety risks. Maintaining road smoothness is thus vital for optimizing transportation efficiency and user satisfaction.

Traditionally, road roughness assessment has relied on specialized equipment such as profilometers and manual inspections. Although these methods offer accuracy, they are often expensive, labor-intensive, and limited in spatial and temporal resolution. As a result, many road networks in developing regions lack frequent or comprehensive monitoring, delaying maintenance interventions and exacerbating infrastructure decay. Recent research has investigated automated and data-driven methods for evaluating the status of roads in order to get beyond these constraints. The authors in [1] stressed the value of technology-driven, objective approaches for evaluating road roughness and how it affects driver comfort. The authors in [2] suggested a methodology based on machine learning for forecasting aggregate segregation and pavement roughness during construction. The International Roughness Index (IRI) was accurately predicted using deep learning models and digital image analysis, proving the usefulness of machine learning (ML) in pavement quality control.

In this study, the focus is not on directly measuring physical surface damage (such as potholes or cracks) but rather on quantifying ride-induced roughness severity based on ISO 2631-1 [3] vibration exposure thresholds. This distinction is essential because road roughness is a measurable dynamic response experienced along the vehicle trajectory, whereas surface damage refers to the geometric deterioration of the pavement layer. The present framework therefore functions as a screening-level indicator of segments that may require further inspection, rather than a substitute for surface-scale damage mapping.

Advancements in intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and the proliferation of in-vehicle sensors offer new opportunities for scalable, low-infrastructure screening road condition monitoring. In particular, accelerometer data collected from moving vehicles can provide rich insights into pavement conditions. When combined with machine learning (ML), these sensor signals can be harnessed to detect road anomalies, classify roughness severity, and inform proactive maintenance strategies.

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of ML for pavement quality assessment. For example, a machine learning pipeline for road roughness prediction using in-vehicle sensors was proposed in [4], illustrating that ML techniques can reliably evaluate road conditions using reasonably priced sensors mounted in passenger automobiles. The significance of data-driven approaches for assessing road conditions and their effects on drivers was also highlighted in [1] in which a Random Forest approach was used to investigate the association between road roughness and driver comfort in long-haul transportation.

However, ref. [5], which focused on impact detection using a machine learning approach for experimental road roughness classification, underscored the importance of continuous evaluation of road conditions under normal operating conditions, further validating the role of ML in real-time road monitoring. One possible approach to improving road maintenance procedures is the incorporation of machine learning techniques into road roughness evaluation. Transportation authorities may optimize resource allocation, carry out preventative maintenance interventions, and eventually raise road safety and user happiness by utilizing sensor data and cutting-edge algorithms.

In order to facilitate predictive maintenance planning, this study suggests a machine learning-based framework for determining the degree of road roughness and predicting deterioration rates. The framework seeks to improve road infrastructure management decision-making by utilizing cutting-edge data-driven methodologies, facilitating proactive maintenance interventions and optimizing budget allocation. Moreover, most prior works lack a multi-model comparison framework and often overlook the utility of anomaly detection in ranking road segments for urgent repair. There is also limited application of these technologies in African urban contexts where road degradation is a pressing issue due to funding limitations and rapid urbanization.

In the South African context, road degradation is exacerbated by unique local factors such as intense temperature fluctuations, suboptimal construction materials, and limited maintenance funding. Urban areas like Pretoria face persistent challenges from heavy vehicle loads and delayed repairs, which accelerate the wear and roughness of road surfaces. Furthermore, the backlog in infrastructure renewal due to budget constraints often leads to the prolonged exposure of users to deteriorating roads. By focusing this research on Pretoria, a representative urban center with diverse traffic and environmental conditions, the framework provides an evidence-driven solution tailored to low-resource urban environments. Although limited to a single city in this phase, the approach is designed for scalability and can be extended to other cities in South Africa or to similar developing regions with minimal calibration.

Despite the promising advances in machine learning for pavement monitoring, several research gaps remain. First, most existing studies treat roughness classification and anomaly detection as independent tasks, with limited focus on integrating these into a unified decision-support pipeline for maintenance planning. Second, benchmark comparisons often emphasize a single model, overlooking the practical value of evaluating multiple algorithms side by side under identical conditions. Third, the majority of road roughness studies are concentrated in developed regions, with little application in African urban contexts where infrastructure degradation is accelerated by climatic extremes, heavy vehicle traffic, and constrained maintenance budgets. Addressing these gaps is essential for building scalable, low-infrastructure, and context-specific road condition monitoring systems.

In addition to widely used ensemble and shallow neural network methods, recent research highlights the value of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for pavement condition assessment. CNNs are particularly effective at learning localized patterns from sensor signals, making them a strong candidate for vibration-based road monitoring tasks [6,7]. To ensure fair benchmarking with state-of-the-art approaches, this study also incorporates a one-dimensional CNN as a deep learning baseline alongside Random Forest, XGBoost, and MLP.

In this work, we quantify vibration-based ride roughness from tri-axial accelerations and categorize roughness severity with reference to ISO 2631-1 exposure/comfort guidance. We do not directly segment or size discrete surface damage (e.g., pothole diameter, crack length). Instead, roughness serves as a screening-level proxy to prioritize segments for subsequent, imaging-based inspection and maintenance planning. Throughout, we use the terms “roughness severity” and “anomaly flagging” rather than “damage detection” to reflect this scope.

Within this clarified scope, our work makes the following contributions:

- Integrated framework: We propose a unified pipeline that combines supervised machine learning classification, z-score-based anomaly detection, and the statistical ranking of road segments to support predictive maintenance planning.

- Comparative benchmarking: We benchmark four models (Random Forest, XGBoost, MLP, and a 1D-CNN) under identical conditions. Using this structured accelerometer dataset, the ensemble models and MLP outperform the 1D-CNN, establishing a fair state-of-the-art baseline for comparison.

- Contextualized application: We apply the framework to road data from Pretoria, South Africa, highlighting its adaptability to low-resource urban environments where conventional inspection is infeasible.

- Robust validation and interpretability: We evaluate statistical significance (McNemar’s test) and model feature importance, ensuring transparency and reliability.

- Actionable decision-support: By prioritizing road segments based on anomaly severity, the framework provides a practical tool for transport authorities to optimize repair scheduling and resource allocation.

In summary, this study contributes a scalable, interpretable, and context-sensitive machine learning approach for near-real-time screening and predictive maintenance, with implications for both developing and developed transport systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in ML-based road roughness analysis. Section 3 details the methodology, including dataset description, preprocessing, feature engineering, and model training. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Section 5 concludes the study with recommendations and suggestions for future work.

2. Related Work

Extensive research studies have been conducted to explore machine learning techniques for pavement condition assessment. Most of the existing studies leverage sensor or image data to evaluate surface anomalies, classify road types, or predict roughness indices. Using data from the Falling Weight Deflectometer (FWD), the study in [8] created a machine learning-based method for predicting the Pavement Condition Index (PCI). The Committee Machine Intelligent System (CMIS) attains maximum accuracy while testing a variety of models, including MLP, RBF, and hybrid techniques. Results demonstrated that increased road inspection efficiency and decreased human error using data from 236 pavement segments on the Tehran–Qom expressway. It was further highlighted that future studies need to investigate non-destructive testing techniques like Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), increase datasets, and take environmental aspects into account.

With the use of gyroscope and accelerometer data, the authors in [9] investigated the use of machine learning for road surface classification. It was shown that CNNs performed better than conventional techniques when compared to deep learning with classical models and attained an accuracy of 93.17%. In addition to highlighting CNNs’ efficacy for Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) and Advanced Drivers Assistance System (ADAS), the report makes recommendations for further research on weather aspects, sensor fusion, and lightweight embedded system models. In order to overcome the high expense of conventional measurements, ref. [10] explores the use of machine learning to predict the International Roughness Index (IRI) based on pavement distress characteristics. The study addresses the high costs and limitations of traditional IRI measurements, which exclude certain road classes at the network level. The research aimed to determine whether IRI can be reliably estimated using distress types, densities, and severities, reducing the need for direct roughness measurements. The study made use of a Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naïve Bayes, and Logistic Regression on data from 50,400 road segments. The study demonstrated that SVM has the highest accuracy (0.96). The findings indicate that pavement type affects the results obtained although distress features can accurately estimate IRI. It was recommended that time-lagged models and distress probability estimation needed to be investigated in future studies.

A low-infrastructure screening machine learning method for real-time road abnormality identification, utilizing accelerometers installed on vehicles, was presented in [11]. The best performance is achieved by floorboard-mounted sensors (91.9%), while SVM attains the highest accuracy (86.4%). For better monitoring, the study recommended that deep learning be combined with crowdsourcing data. In order to overcome the shortcomings of conventional evaluation techniques, the work in [12] created a machine learning model to forecast flood-induced pavement damage. Flooding speeds up pavement roughness and cracking according to results from the application of SVM, MLP, K-Nearest Neigbour (KNN), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) on Louisiana’s pavement distress records, flood data, and traffic statistics. XGB achieved the highest accuracy. In terms of prediction dependability, Louisiana’s 2016 flood maps fare better than FEMA’s. The study recommended adding real-time monitoring and other environmental parameters for better predictions, and it emphasized the advantages of combining historical data for proactive maintenance.

To predict the deterioration of pavement, the research in [13] created a machine learning framework that takes uncertainty, interpretability, and feature selection into account. Based on road data from Jiangsu Province, the model achieved great accuracy (R2 = 0.86), using BorutaShap for feature selection, a Bayesian neural network (BNN) for prediction, and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) for explanation. Road age, traffic volume, and temperature are important deterioration variables. It was highlighted that the framework needed to be expanded to include other indicators, that the data collection needed to be improved, and uncertainty handling needed to be enhanced in future studies. A machine learning approach for identifying roadway defect hotspots utilizing probabilistic risk assessments and multi-asset interrelations is presented in [14]. It was shown that, in terms of predicting defect risk, Random Forest Regression was shown to perform better than conventional models. For increased accuracy, the paper recommended that real-time sensor data be combined and that the framework be expanded to additional infrastructure networks.

The absence of specialized datasets and models for identifying road rutting, a significant pavement distress, is addressed in [15]. The goal of the project is to create a deep learning-based detection framework by utilizing semantic segmentation (PSPNet, DeepLabV3+) and object detection (YOLO (You Only Look Once) X) models. In total, 949 photos were gathered from various Japanese sources and annotated at the object and pixel levels. PSPNet had an accuracy of 72.67% and an IoU of 54.69%, whereas YOLOX-s had the highest detection accuracy (mAP@IoU = 0.5 of 61.6%). The study draws attention to issues including incorrect classification brought on by road markings and shadows. The dataset should be enlarged in future studies, and road rutting detection should be incorporated into more comprehensive road damage categorization models.

An interpretable machine learning framework for predicting the IRI is developed in the study “Pavement Roughness Prediction Using Explainable and Supervised Machine Learning” [16]. Due to the inability of traditional models to capture non-linear interactions, Sri Lankan road data (2013–2018) was subjected to RF, DT (Decision Tree), XGB, SVM, and KNN. Pavement age is the primary predictor, according to SHAP analysis, and RF performs better than the others (R2 = 0.906, MAE = 0.310). For improved accuracy, future studies should combine deep learning and contextual elements.

The study in [17] investigated machine learning by contrasting MLR, ANN (artificial neural network), and FIS (Fuzzy Inference System) methods for predicting the Pavement Condition Index (PCI). It was shown that ANN performed better than other approaches, increasing R2 by as much as 51.32%. For improved pavement management, the study recommends combining hybrid models with real-time sensor data. The work in [18] made use of deep learning for automated road defect detection using Faster R-CNN (Regions with convolutional neural networks) and SSD (Single-Shot multibox Detector) models. The best accuracy (mAP 40%) was obtained with faster R-CNN that had been fine-tuned on high-resolution data. For better predictive maintenance, it was recommended that future studies should incorporate multi-modal sources, sophisticated designs, and real-time sensor data. Using vehicle vibration data, the study in [7] created a lightweight 1D-RCNN model for pavement roughness classification in real time. With an accuracy of 98.7%, it surpassed CNN, LSTM, and GRU models. It was recommended that for additional advancements, future studies are needed to investigate transformer-based systems and the integration of real-world data.

The authors in [19] investigated the use of machine learning for asphalt overlay optimization and predictive pavement performance prediction. The study demonstrated how distresses such as alligator cracking, rut depth, and IRI can be predicted using LTPP data and SVR (Support Vector Regressor), RF, GBM (Gradient Boosting Machine), and Stacking Ensemble models. While RF and Stacking are excellent at predicting alligator cracking, GBM was shown to be the best at rut depth and IRI prediction. The results demonstrated how recycled asphalt and milling affected pavement degradation. Deep learning was recommended by the study for increased accuracy. The impact of road roughness on driver comfort during long-distance travel was examined using Random Forest regression in [1]. The MIRANDA app’s more than 1 million acceleration data points were used to reveal a clear relationship between discomfort and uneven roadways. Even though XGBoost was more accurate, Random Forest was demonstrated to be the better choice for real-time implementation. The report recommended that future research should focus on other parameters such as regional extension and real-time road monitoring systems, emphasizing smoother road maintenance for increased safety and efficiency.

The application of machine learning to forecast IRI and examine the effects of distress intensity was examined in the study [20] that considered the influence analysis of pavement distress on IRI using ML. The study made use of Long-Term Pavement Performance (LTPP) data to create RF and XGB models since traditional models are unable to capture complex, non-linear relationships between multiple variables. It was shown that RF performed better, with RMSE = 0.2191 and R2 = 0.7874. Transverse fractures, rutting, and alligator cracks are identified by SHAP analysis as major contributors to IRI, with a 7 mm rutting depth threshold being crucial for the escalation of roughness. For increased accuracy, the study recommended adding more variables and extending models to urban networks.

To get beyond the drawbacks of traditional monitoring, the article in [21] used machine learning to categorize road conditions. The paper examined the MLP, DNN, KNN, and logistic regression models using a Kaggle road picture dataset. Following preprocessing, it was shown that MLP performed poorly (40.48%) while DNN attained the maximum accuracy (89.31%). Larger datasets, model optimization, and real-time applications for smart city infrastructure was recommended to be investigated in future studies. Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) are compared for predicting the International Roughness Index (IRI) on Thailand’s highways in the publication Comparative Analysis of Deep Neural Networks and Graph Convolutional Networks for Road Surface Condition Prediction by [22]. Because geographical dependencies are difficult for traditional models to handle, 3023 highway sections (104,606 km) were used in this study. The results indicated that while GCNs operate well on congested city roadways, DNNs perform better in networks with lower connectivity. For increased accuracy, it was recommended that future research should improve data collecting and GCN application refinement.

The Automated Road Quality Assessment (ARQA) framework for deep learning is presented in the study [23]. It was shown that ResUNeXt (Residual U-Networks with Next-level design) performed exceptionally well in crack segmentation (Dice = 0.94), YOLOv8 in vehicle detection (mAP = 0.954), and YOLOX in pothole detection (mAP = 0.816). It was recommended that future research consider creating a real-time mobile application and adding other road elements.

To boost climate resilience, the study in [24] investigated predictive maintenance for highways utilizing machine learning and IoT technology. Models forecast pavement deterioration and maximize maintenance by evaluating sensor data on stress, temperature, and moisture. According to case studies, improved asphalt binders increase durability while permeable pavements improve stormwater management. Proactive actions are made possible by real-time condition evaluations offered by IoT-based monitoring devices. For increased accuracy and cost-effectiveness, it was recommended that future research should investigate hybrid AI models, dataset sizes be increased, and environmental aspects be taken into account.

A drone-based method for evaluating road roughness was suggested in the study in [25]. The creation of a CNN model, employing Gray Level Size Zone Matrix (GLSZM) features and K-means clustering for segmentation, was prompted by the expense and inefficiency of traditional techniques. Because of the model’s 91.94% accuracy, preventive maintenance and extensive monitoring are made possible. For increased accuracy, it was recommended that future studies need to investigate multi-view analysis and sophisticated deep learning models. For better roughness prediction, the authors in [26] include physics-based restrictions into neural networks in their research, “Roughness Prediction of Jointed Plain Concrete Pavement Using Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)”. Because of the inaccuracy of traditional models, PINNs trained on Long-Term Pavement Performance data with MEPDG constraints are used. The model outperformed traditional methods with an R2 of 0.90 and an MAE of 0.134 after optimization with Optuna (hyperparameter optimization framework). Transverse cracking and early roughness are important predictors. Future research should improve data collection techniques and apply PINNs to additional pavement distress categories. A Reinforcement Learning (RL)-based framework was developed in the study [27] to optimize road maintenance under flood threats. When addressing pavement deterioration and financial restrictions, RL-TB and RL-TH models were shown to perform better than conventional methods when using real-world flood data. Expanding to multimodal networks, including real-time sensor data, and investigating financial tactics like flood insurance are all areas that require more research.

Although ML-based road roughness categorization has made great strides, several gaps remain unaddressed. Most studies focus on classification or regression without integrating post-processing mechanisms such as anomaly detection or repair prioritization. Additionally, few studies compare multiple ML models side-by-side using identical feature sets. Real-time signal-processing techniques, such as RMS-based thresholding, are also often excluded as baselines, limiting comparative assessment.

Notably, there is limited literature focusing on African urban regions, despite the urgent need for scalable and low-infrastructure road monitoring. This study aims to contribute to filling these gaps by performing the following functions:

- Comparing four ML classifiers (RF, XGB, MLP, 1D-CNN) using in-vehicle accelerometer data.

- Integrating anomaly detection and z-score-based prioritization for maintenance planning.

- Demonstrating real-world application in Pretoria, South Africa.

- Providing a reproducible framework adaptable to low-resource settings.

Deep learning models, particularly CNNs, have recently been applied to road roughness detection using vibration and sensor signals. Study [6] demonstrated that 1D CNNs effectively detect pavement distress from acceleration sensor data, achieving robust performance across multiple conditions. Similarly, ref. [7] proposed a residual CNN for real-time pavement roughness classification, reporting an accuracy of 98.7% and outperforming LSTM and GRU variants. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating CNNs as state-of-the-art baselines in road monitoring research.

The next section presents the methodological design considered in this study, dataset characteristics, and the model development pipeline.

3. Methodology

This section presents the methodology used for classifying road roughness severity and enabling predictive maintenance. It analyzes road roughness and identifies significant road deterioration anomalies using a data-driven methodology. The dataset, which includes 159,411 rows and 24 columns with different road condition metrics, was extracted from [1], and stored in an Excel file (Appendix A.1). In data preprocessing, duplicates were eliminated, missing values were handled, and numerical features were normalized as needed. In order to achieve the robust evaluation of the model, the dataset was then divided into subsets of 80% training and 20% testing. Feature selection approaches were used to find the most pertinent variables influencing road roughness in order to increase model efficiency.

Python (version 3.10) was used in the JupyterLab (Anaconda) environment for the study’s model development and analysis. To predict and rate road roughness, three machine learning models were trained: Random Forest, XGBoost, and a neural network. The choice of the models was based on the following: The neural network captured complex non-linear correlations in the data, while Random Forest and XGBoost provided significant feature importance insights. These models were selected due to their prediction powers. In order to ensure reliability in predicting road conditions, the model performance was evaluated using appropriate evaluation metrics (precision, recall, f1-score, and accuracy).

Z-score-based anomaly detection was employed to systematically identify statistically significant departures from the mean roughness values thereby indicating segments with critical road deterioration. We used z-scores to standardize acceleration magnitude and flag statistically unusual segments. A threshold of z ≥ 2, commonly used to identify outliers, was adopted to indicate critical deterioration warranting inspection and potential maintenance. This standardization is crucial for establishing a consistent and objective criterion for identifying anomalies across different road segments. For this study, road segments with z-scores exceeding a threshold of 2 were flagged as critical. This threshold is widely adopted in statistical practice to identify outliers or unusual data points, as values beyond two standard deviations typically represent approximately 5% of data in a standard normal distribution, signifying a notable deviation from the norm. In the context of road maintenance, this threshold serves as a robust criterion for pinpointing segments exhibiting exceptionally high roughness levels that likely warrant immediate attention and further investigation for potential maintenance interventions.

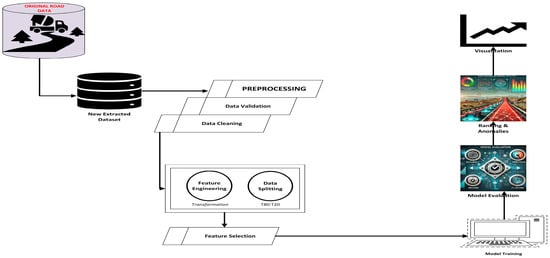

Data patterns, relationships, and distributions were examined using visualization techniques such as scatterplot and heatmap. The final product was a significant road summary analysis report (Appendix A.3) that highlighted important discoveries and offered data-driven insights for infrastructure development and road maintenance (Appendix A.2). By adopting a methodical and analytical approach to road condition evaluation, this methodological framework (Figure 1) helps transportation management make well-informed decisions. For clarity, Figure 1 visualizes the complete framework pipeline, integrating data preprocessing, feature engineering, supervised classification, statistical anomaly detection, and maintenance prioritization.

Figure 1.

Integrated framework overview.

3.1. Data Collection

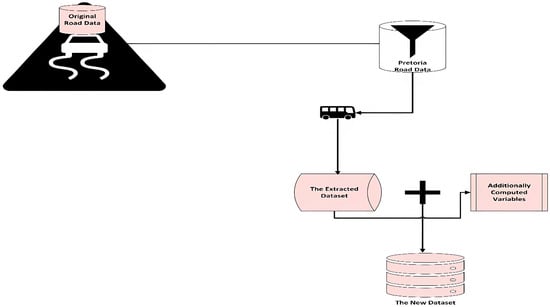

An existing dataset from [1] is used in this study. The dataset, which initially included 20 columns and 1,048,575 rows of data, recorded different driving traits and road conditions. A subset of the data was taken out for this study, with a particular emphasis on the road conditions in the city of Pretoria in Gauteng Province, South Africa (Figure 2). Road conditions in Pretoria might not be accurately reflected using the complete dataset, which introduces variability from other locations. In addition, reducing the dataset enhances computational efficiency while retaining a sufficiently large sample to ensure statistical significance. The dataset comprises 159,411 rows and 24 features derived from in-vehicle sensor recordings collected in Pretoria, South Africa (Appendix A.2). After segmentation, the Pretoria subset contained 17 unique road segments (road_id) spanning 133.0 km of driven network. To focus on Pretoria, we geo-filtered coordinates within a bounding box for the city and excluded points outside this range. Additional filters removed unrealistic speeds (>160 km/h) and prolonged idling (<2 km/h sustained). Key features include raw accelerometer data (accel_x, accel_y, accel_z), timestamps, and computed values like acceleration magnitude, time, and distance traveled. A summary of the core features is presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Data extraction flow (DEF).

Table 1.

Selected features.

Although vehicle-mounted IMUs only capture vibration responses along the tire path, they provide a scalable and low-infrastructure means of assessing ride roughness over time. The intent is not to replace full-surface imaging systems but to enable the rapid, first-level screening of pavement sections that may warrant closer inspection. To mitigate potential biases from speed, suspension, or vehicle differences, our analysis incorporates normalization by speed bins, multiple traversal averaging, and z-score anomaly consensus across runs. High-precision IMUs were not required; the sensors used were consumer-grade units (<R 1000) similar to those embedded in smartphones, making the approach comparatively low-cost relative to laser or camera arrays.

The selection of an inertial measurement unit (IMU) platform for vibration capture is scientifically justified by the extensive literature demonstrating its reliability for road roughness characterization. Modern low-cost IMUs have been shown to correlate strongly (r > 0.9) with International Roughness Index (IRI) or profilometer readings when appropriate calibration and filtering are applied [9,11,28]. The vertical acceleration component (accel_z) effectively represents suspension deflection and tire–road normal force, which are sensitive to pavement irregularities. Therefore, while high-precision laser or profilometer instruments remain the reference for certification, IMU-based measurements offer a validated, low-cost alternative for network-level screening, particularly suited to data-scarce regions. The present study follows this validated principle by mounting a calibrated tri-axial accelerometer on a standard vehicle chassis to record translational vibrations under controlled speed and load conditions.

In order to improve the study’s analytical depth, four additional variables were computed throughout the preprocessing and feature engineering stages:

- accel_magnitude: This measure of total vibration intensity is derived from accelerometer readings (x, y, z).

- Distance: Calculated to evaluate the spatial features of irregularities and rough roads.

- Time: Allows for time-based analysis by capturing the temporal component of road data (conversion of timestamps).

- road_id: This helps with location-based evaluations by giving each road section a unique identity.

Distance was computed between successive GPS points using the Haversine formula and accumulated within each run. road_id was assigned by segmenting continuous runs: a new ID was triggered by time gaps > 60 s or direction changes > 45°, enabling road-level aggregation without external map-matching. These extra features help to increase the model’s forecast accuracy and offer more information about variances in road surfaces.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing, which entails converting raw data into a clear, organized, and useable format, is an essential stage in data analysis and machine learning. It guarantees that there are no errors, inconsistencies, or noises in the dataset that could impair the effectiveness of prediction models [29]. Preprocessing included the removal of duplicate and missing records, the conversion of timestamp formats, and the normalization of numeric values. Records with missing accelerometer values (accel_x, accel_y, accel_z) were dropped. GPS rows with absent latitude/longitude or precision > 25 m were excluded. Non-core numerical fields with <0.5% missing entries were median-imputed; categorical fields were mode-imputed. Overall, <2% of rows were removed, ensuring negligible bias. The two core components of the preprocessing phase are data validation and data cleaning. Since the study made use of derived data from the previous study, comprehensive validation and cleaning were performed to ensure integrity prior to modeling.

The process of determining the quality, completeness, and integrity of data prior to any changes or analysis is known as data validation [30]. Python scripts were used in this study to check for duplicate records and missing values and confirm data types.

According to Rahm and Do [31], data cleaning is the process of deleting or rectifying erroneous, insufficient, or inconsistent data from a dataset as part of preprocessing efforts and ensuring data suitability and conformity before data modeling. For instance, Temp Acquisition is a time variable captured in the original dataset but not stored in time format. At this phase, it was coded and transformed into the usable time format, preserving and naming the former column as ‘Time’ and giving the new variable the previous name ‘Temp Acquisition’ to enhance understanding.

3.3. Feature Engineering

Feature engineering is an essential stage in machine learning that entails turning unstructured data into meaningful representations, which can be used to improve model performance [32]. Relevant python snippets were applied in the creation and modification of features, and the appropriate encoding of variables was performed to ensure accurate predictive analysis. Road roughness classification, feature transformation, and label encoding were the three main feature engineering procedures carried out in this study. Feature engineering introduced derived metrics such as acceleration magnitude to capture dynamic road responses. Label encoding was applied to convert categorical roughness classes into integers.

3.4. Data Labeling and Roughness Categorization

In accordance with ISO 2631-1:1997 [3], which classifies vibration exposure severity according to human comfort levels, a roughness classification based on acceleration magnitude was developed. The nature of the data gathered by in-car sensors [1] that capture tri-axial acceleration signals is in good agreement with this standard. Using ISO 2631-1 thresholds, the acceleration magnitude (accel_magnitude) was converted into four categorical classes (Smooth, Moderate, Rough, Very Rough) (Table 2). This served as the target for training, while only accel_x, accel_y, accel_z were used as predictors to avoid leakage. The new column ‘roughness_category’ contained these categories, which were used as the target labels for training the model.

Table 2.

Road roughness classification.

These labels served as the target classes for model training. In order to smooth acceleration magnitude values, the newly developed roughness_category was employed as the objective variable, and three important accelerometer readings, accel_x, accel_y, and accel_z were chosen as input features (Equation (1)).

Let,

where

X = [accel_x, accel_y, accel_z]

Y = roughness_category

X is the input feature matrix;

Y is the target variable.

The relationship among these variables is expressed as follows:

Label encoding was used to transform the categorical target variable (roughness_category) into a numerical form because machine learning models usually require numerical inputs. The four roughness categories were converted into integer labels using the LabelEncoder() function from the sklearn.preprocessing library so that the model could process them efficiently. After processing, the final dataset was saved as processed_road_dataset.csv, guaranteeing that it was organized properly and prepared for model training.

We refer to the target as roughness severity rather than surface damage; labels are defined by acceleration magnitude thresholds (ISO 2631-1), while predictors remain the raw tri-axial signals (ax, ay, az); statistics such as peak z-score and p95 are computed for reporting/prioritization, not as labels, thereby avoiding label leakage.

3.5. Data Splitting

The process of separating a dataset into smaller groups, usually a training set and a test set (and occasionally a validation set), is known as data splitting. This guarantees the model’s generalizability by enabling it to learn from one set of data and be assessed on another [32]. Data splitting was performed here prior to feature selection to avert possible data leakage and overfitting. The dataset was split using a 80:20 ratio for training and testing, respectively. A stratified random 80:20 split (scikit-learn train_test_split, random_state = 42) was applied to preserve class balance. No temporal sorting was used, preventing leakage from contiguous driving runs. Class proportions in the training and test sets matched the full dataset due to stratified splitting (see Table 3), ensuring that performance was not inflated by class imbalance. To avoid leakage, only raw tri-axial accelerations (accel_x, accel_y, accel_z) were used as predictors; the label-deriving accel_magnitude was not used as a model input.

3.6. Feature Selection

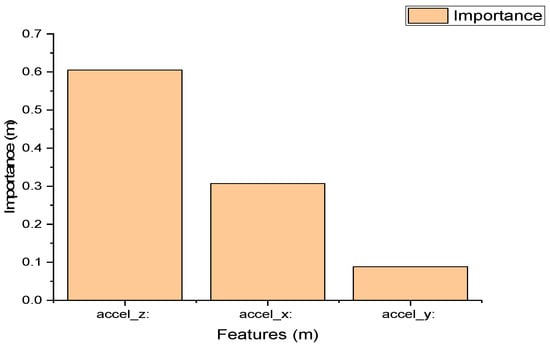

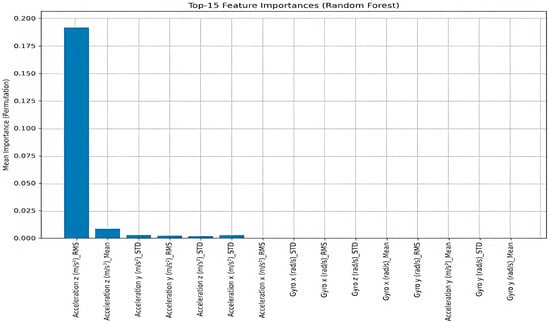

The process of choosing the most pertinent features from a dataset in order to enhance model performance, lessen overfitting, and save computing costs is known as feature selection. Numerous strategies, such as filter methods, wrapper methods, or embedded methods, can be used to accomplish it [33]. For this study, however, the embedded method (feature importance from a Random Forest model) was preferred and applied. This is due to its inherent ability to evaluate feature importance through tree-based mechanisms. Unlike XGBoost and neural networks, which lack direct and interpretable feature selection methods, Random Forest assigns feature importance scores based on decision splits, thus enhancing computational efficiency, and ensures that only the most relevant features are retained before model training. Equation (2) shows the top k (k here is 3) important features, while Table 3 and Figure 3 present the output.

where

Figure 3.

Bar chart of feature importance.

S is the set of selected features;

Top-k(I(x)) refers to the indices of the top k largest values in I(x).

Table 3.

Feature importance.

Table 3.

Feature importance.

| Features | Order/Magnitude of Importance |

|---|---|

| accel_z: | 0.6049 |

| accel_x: | 0.3069 |

| accel_y: | 0.0882 |

3.7. Model Training

In order to discover patterns and connections between input features and target labels, model training is applied to refine the machine learning algorithm, using training data [34]. In this study, four classifiers, the Random Forest Classifier (RFC), Extreme Gradient Boost Classifier (XGBoost), neural network classifier (MLP—multi-layer perceptron), and 1-dimensional convolutional neural network (CNN), were trained using an 80/20 train–test split. Feature selection was performed using embedded importance scores from Random Forest. For benchmarking, a rule-based classifier using only acceleration thresholds was implemented to evaluate the added value of ML.

1D-CNN Architecture

The 1D-CNN comprises two convolution–pool blocks (Conv1D(32, kernel_size = 5, activation = ReLU) → MaxPool1D(pool_size = 2); Conv1D(64, kernel_size = 3, activation = ReLU) → MaxPool1D(pool_size = 2)); these are followed by GlobalAveragePooling1D, Dropout(p = 0.3), and Dense(64, activation = ReLU), with a final Dense(4, activation = Softmax) output. We trained with Adam (learning rate = 1 × 10−3), categorical cross-entropy, batch size = <64>, and early stopping (patience = <10>) using a 0.2 validation split. This lightweight baseline is appropriate for vibration signals while limiting overfitting on structured inputs. The training settings are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The 1D-CNN training settings.

Because Random Forest is ensemble-based, it resists overfitting and is renowned for handling high-dimensional data [35]. Compared to black-box models like deep learning, it is easier to interpret. It works best with structured datasets with numerical and categorical input features, such as road roughness data. Equation (3) represents RFC.

where

is the predicted class label.

Ti(X) represents the prediction from the i-th decision tree.

The final prediction is the most frequent class among all tree predictions.

XGBoost was considered in this study because it is a potent boosting technique that successively optimizes errors and typically performs better than traditional machine learning models when it comes to structured data [36]. By utilizing feature importance and boosting techniques, it strikes a balance between high accuracy and interpretability. Similarly to RF, XGBoost works well with structured datasets with numerical and categorical input features, such as road roughness data. Equation (4) is the mathematical representation of the XGBoost modeling prediction.

where

is the predicted class label;

T is the number of trees;

ft(Xi) is the prediction from the t-th tree.

The model minimizes the following objective function (Equation (5)):

where

L = loss function;

l(yi,) is the loss function (log loss for classification);

Ω(ft) is the regularization term to prevent overfitting.

Variations in road roughness can be captured by neural networks (MLP), which are able to understand intricate, non-linear correlations in the data. Complex patterns that may be challenging for tree-based models to capture can be modeled by MLP. Although they are more frequently used for unstructured data (such as text or images), MLPs can nonetheless function effectively where deep feature interactions exist (Equations (6) and (7)).

where

W(l) and b(l) are the weight matrix and bias of layer l;

σ(·) is the activation function (e.g., ReLU).

In road roughness classification, robust and varied learning patterns are made possible by the combination of deep learning (neural networks) and ensemble learning (Random Forest and XGBoost). While Random Forest excels at interpretability, XGBoost optimizes errors through boosting, and neural networks use deep learning approaches to capture complicated relationships.

While numerous studies have employed complex deep learning models such as CNNs or LSTMs, these are typically optimized for unstructured data types such as images or sequential time-series. In contrast, the input dataset used in this study comprises structured tabular data (sensor-derived acceleration values), for which Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) have shown superior performance with faster training times and lower computational overheads. Preliminary trials with deeper architectures did not yield substantial performance gains and incurred higher risks of overfitting due to the lack of temporal dependencies in the preprocessed data format. While many studies use deeper architectures optimized for unstructured or sequence data, our inputs are structured tri-axial samples. Accordingly, we include an MLP as a lightweight deep learning model suited to tabular features.

To ensure fair benchmarking against state-of-the-art approaches for vibration/sensor signals, we also implement a one-dimensional CNN (1D-CNN) as the deep learning baseline. The 1D-CNN comprises convolution and pooling layers for local feature extraction, followed by fully connected layers with softmax output. All models used the same 80/20 split. The neural models (MLP, 1D-CNN) were trained with Adam and categorical cross-entropy, whereas the tree ensembles (RF, XGB) used their standard training procedures in scikit-learn/XGBoost. The motivation for including CNN lies in its demonstrated ability to capture temporal and localized vibration patterns in accelerometer data, providing a fair state-of-the-art benchmark against which classical machine learning models can be compared.

We selected hyperparameters via randomized search with cross-validation. For RF, we varied between n_estimators, max_depth, and max_features; for XGB, we varied between n_estimators, max_depth, learning_rate, subsample, and colsample_bytree; and for MLP, we used the hidden_units, layers, and dropout. Within the tested ranges, the performance ranking (RF ≈ XGB > MLP > 1D-CNN) remained stable; top models varied by less than ±1% absolute accuracy across settings. Search ranges and the selected values are provided in Appendix A.1 (notebook/config cell).

3.8. Model Performance and Evaluation

Model performance was assessed using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrices (Appendix A.1). Ground truth was derived from the acceleration-based labeling process. Although this approach lacks direct IRI validation, it provides a viable approximation in the absence of gold-standard data.

The accuracy metric measures the model’s performance by dividing the number of accurate predictions by the total number of predictions the model made (Equation (8)).

The classification report contains important metrics that give a more thorough insight of how well the models perform across various classes; these are precision, recall, and F1-score. The model’s ability to handle unbalanced datasets is also assessed using the classification report. Equations (9)–(11) show the mathematical equations for computing these metrics.

where

TP = Number of True Positives;

FP = Number of False Positives;

Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions.

where

TP = Number of True Positives;

FN = Number of False Negatives;

Recall, also called sensitivity, measures the ability of the model to capture all positive occurrences.

The F1-score is the harmonic (balancing) mean of both the precision and recall metrics.

3.9. Ranking Road Roughness and Anomaly Detection

Using the statistically established threshold of 2 standard deviations, as discussed in the methodology, segments exceeding this threshold above the mean were flagged as critical. These were ranked by severity to guide maintenance prioritization. This complements ML classification by enabling actionable decision-support.

4. Results and Interpretation

This section presents the performance of the trained models, interprets the results in the context of road roughness detection, and discusses the effectiveness of the anomaly detection and prioritization framework.

4.1. Model Validation and Overfitting Control

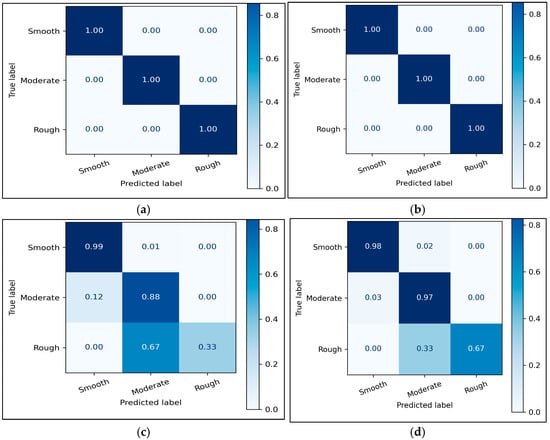

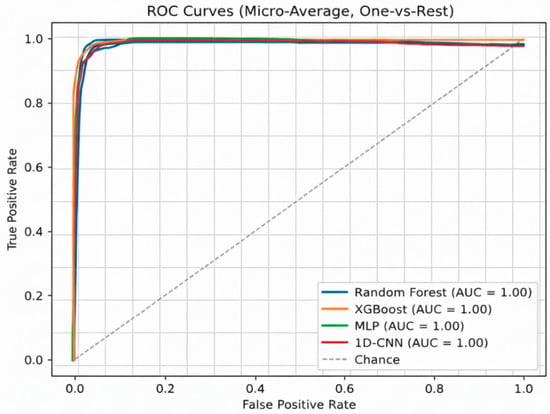

To preclude data leakage, only raw tri-axial accelerations (accel_x, accel_y, accel_z) were used as predictors, excluding any derived features such as accel_magnitude. A stratified 80/20 split preserved class proportions, and 10-fold cross-validation confirmed consistent accuracies (SD < 1%). Figure 4a–d summarizes the confusion matrices for four classifiers, while Figure 5 plots ROC curves, illustrating near-perfect separability across classes. These validations corroborate that the high accuracies arise from strongly separable vibration signatures rather than model memorization.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrices for (a) random forest, (b) XGBoost, (c) Multi-Layer Perceptron, and (d) 1D-CNN.

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves showing average AUC for the tree-ensemble models.

Figure 4 presents the normalized confusion matrices for all four classifiers, confirming near-perfect discrimination across the four roughness severity categories. Each matrix is normalized by true-class frequency. The high diagonal values indicate consistent class-wise accuracy across models, validating balanced performance and correct roughness severity discrimination. Misclassifications are minimal and randomly distributed, with no class dominance, demonstrating balanced model learning.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves in Figure 5 further illustrate classifier separability, with ensemble models achieving the largest area under the curve (AUC ≈ 0.99) and neural models maintaining robust generalization. Shaded regions denote 95% confidence intervals across ten-fold cross-validation. High AUC values (>0.98) confirm strong class separability and low false-positive rates, reinforcing model reliability.

4.2. Model Performance Comparison

To orient the reader, we first summarize the class distribution and dataset balance; we then compare model performance (Table 5 and Table 6) and statistical significance (Table 7).

Table 5.

Class distribution of road roughness categories.

Table 6.

Model performance evaluation results.

Table 7.

McNemar’s test results.

Before evaluating model performance, it is important to highlight the distribution of samples across the four roughness categories to demonstrate dataset balance and reduce concerns of overfitting (Table 4).

The dataset is approximately balanced across the four roughness categories, as shown in Table 5. To preserve this balance during evaluation, we used a stratified 80/20 train–test split, which maintains class proportions and mitigates imbalance effects.

Counts reflect the post-preprocessing dataset and stratified split; percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding. As shown in Table 5, the dataset is approximately balanced across the four categories, which reduces the risk that performance metrics are inflated by class imbalance and ensures that no single class dominates the learning process; this strengthens the validity of the classification metrics reported in Table 6.

The ensemble models (RF and XGB) achieved perfect accuracy, while MLP and CNN delivered competitive but slightly lower performances. The consistently high performance across models provides a solid foundation for subsequent anomaly detection and prioritization. In particular, the strong separation achieved by RF and XGB ensures that misclassified segments are rare, thereby improving confidence when these models are later used to flag statistically significant anomalies.

To further analyze the statistical significance of performance differences among the models, McNemar’s test was conducted for pairwise comparisons (Table 7). The test assesses whether two classifiers differ significantly in terms of their prediction disagreement on the same instances.

The comparison between Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB) yielded a chi-squared value of 0.1458 with a p-value of 0.7026, indicating no significant difference in their predictions. This suggests a substantial overlap in the types of instances both models correctly or incorrectly classified. By contrast, both comparisons involving the neural network (MLP) model showed statistically significant differences. The RF vs. MLP comparison produced a chi-squared value of 105.14 (p < 0.0001), while the XGB vs. MLP comparison yielded one of 115.81 (p < 0.0001). These results suggest that the MLP model made significantly different prediction decisions, likely due to its distinct modeling approach compared to the tree-based models. This highlights the diversity in learning mechanisms among the models, which could be beneficial if considered for ensemble methods or model fusion.

These findings reinforce the fact that the perfect accuracies observed for RF and XGB are not artifacts of overfitting but reflect their consistent predictive overlap, whereas the statistically significant differences with MLP highlight methodological diversity rather than dataset imbalance.

Across all classifiers, false-positive (FP) and false-negative (FN) rates were consistently below 1%, confirming that the models rarely misclassify smooth segments as rough or vice versa. This observation aligns with the ROC analysis (AUC > 0.98 for RF and XGB; 0.96 for 1D-CNN), indicating a negligible trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, the framework demonstrates operational reliability suitable for first-level screening, where minimizing missed detections is more critical than completely eliminating minor false alarms.

4.3. Rule-Based Baseline vs. ML Models

A rule-based classifier using acceleration thresholds achieved only 91.8% accuracy, substantially lower than that of the ML models. This validates the added value of learning-based approaches in capturing non-linear relationships among features.

While ensemble models and the MLP substantially outperformed the rule-based baseline, residual misclassifications occurred, particularly in the MLP and CNN models. Inspection suggested that such errors were often associated with road segments influenced by transient conditions such as wet pavement, uneven speed humps, or abrupt braking events, which introduce noisy vibration signals. Deep learning models, especially CNNs, were more sensitive to these local perturbations, whereas ensemble methods demonstrated greater robustness due to their averaging mechanism. This error behavior reinforces the decision to integrate anomaly detection as a complementary safeguard for identifying unusual cases that classification alone may misinterpret.

Thus, the limitations of the rule-based baseline and the error tendencies of certain ML models underscore the importance of coupling classification with anomaly detection in the integrated framework.

4.4. Interpretation of McNemar’s Test and Model Diversity

The McNemar test was selected because it is a well-established statistical method for assessing whether two classifiers differ significantly in their proportions of correct and incorrect predictions on the same test set. It complements accuracy metrics by evaluating the symmetry of misclassifications rather than their overall counts. Applying it here verifies that observed performance differences among RF, XGB, MLP, and 1D-CNN are not due to random variation but genuine model architecture effects. This ensures statistical rigor in comparative evaluation and supports the fairness of the benchmarking process.

The identical predictions from Random Forest and XGBoost reflect the structural similarity of both tree-ensemble learners, each partitioning the feature space through successive decision splits that handle non-linearity and heteroscedasticity efficiently. The statistically significant divergence between MLP and the ensemble models (p < 0.001) indicates complementary learning behavior, suggesting potential for stacked or hybrid ensemble fusion that could enhance generalization across heterogeneous driving conditions.

The comparative agreement between the ensemble models further emphasizes their internal consistency, yet it is equally important to understand why certain input variables dominate the learning process. This motivates a closer physical interpretation of the feature importance results presented next.

4.5. Physical Interpretation of Feature Importance

Random Forest’s embedded feature importance revealed that vertical acceleration (accel_z) contributed over 60% to classification accuracy, followed by accel_x and accel_y (Figure 6). This aligns with expectations, as vertical vibrations are the most sensitive to surface irregularities and thus capture roughness severity more directly than lateral or longitudinal components. The dominance of vertical acceleration also aligns with the anomaly detection process: segments exhibiting extreme z-scores in vertical vibration correspond directly to the most severe anomalies identified in Section 4.6, reinforcing the reliability of combining feature importance with statistical outlier detection.

Figure 6.

Feature importance scores computed from the Random Forest (RF) model.

From a physical standpoint, this dominance stems from vehicle–road dynamics. Surface irregularities primarily excite vertical motion transmitted through suspension deflection and tire–road normal forces, whereas lateral and longitudinal vibrations are partially damped by steering and traction systems. Consequently, lightweight models relying predominantly on accel_z signals could enable cost-effective deployment using single-axis sensors without substantial loss of predictive power.

The strong predictive role of vertical acceleration (accel_z) not only strengthens model interpretability but also provides a natural bridge to anomaly detection. Segments characterized by extreme z-axis deviations are most likely to exhibit structural degradation, forming the basis for data-driven road prioritization, as discussed in the next subsection.

Figure 6 summarizes the feature importance ranking derived from Random Forest embedded metrics, highlighting the dominance of vertical acceleration (accel_z) as the primary predictor of surface roughness. Vertical acceleration (accel_z) contributes ≈ 60% of total predictive power, followed by longitudinal (accel_x) and lateral (accel_y) components. The predominance of accel_z reflects the vehicle–road dynamic response in the vertical direction, confirming that single-axis or reduced-sensor implementations could retain high accuracy.

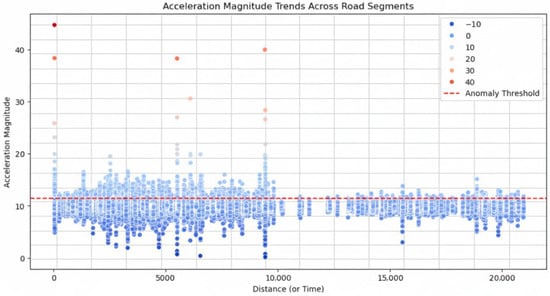

4.6. Anomaly Detection and Road Prioritization

As explained in the methodology, using a statistically determined threshold of z ≥ 2, segments exceeding this threshold above the mean acceleration magnitude are identified as roughness anomalies. For each flagged segment, we compute start/end coordinates, segment length, p95 acceleration magnitude, and the peak z-score, and we export GIS-ready layers for planning. Road segment ID 14, for example, exhibited a peak z-score of 44.50, indicating extreme roughness severity. The top-10 highest-priority segments are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Top-10 road segments requiring urgent maintenance.

Beyond technical accuracy, the anomaly detection framework provides direct actionability for road agencies. Detected anomalies can be flagged within hours of data collection, allowing for near-real-time reporting into asset management systems. This rapid turnaround is particularly valuable in urban environments where dangerous defects can escalate quickly.

From an economic perspective, prioritization ensures that limited budgets are allocated to the most critical segments first. Repairing the top 10 identified roads could prevent escalating damage, vehicle wear, and accident risks, thereby reducing long-term maintenance expenditure. Even a qualitative cost–benefit view suggests that proactive repairs, guided by statistical ranking, are more cost-effective than reactive maintenance cycles. In practice, such prioritization reduces inspection frequency and extends pavement lifespan, resulting in both financial savings and improved public safety.

These findings demonstrate that anomaly detection is not only a technical tool but also a practical decision-support mechanism with direct socio-economic benefits.

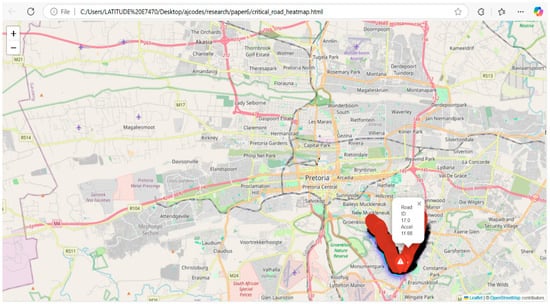

Each statistically flagged anomaly is georeferenced (start–end latitude/longitude) and assigned a severity rank and peak z-score. These outputs can be directly ingested into road-asset management or GIS systems, providing maintenance teams with map-based prioritization of segments for inspection. Thus, the framework yields decision-support information rather than raw vibration values.

Table 9 shows the critical anomalies of these roads, while Figure 7 is the scatter plot. Figure 8 provides a GIS-based visualization of the top-ranked deteriorated segments across Pretoria, illustrating spatial clustering of high-z-score anomalies.

Table 9.

Detected critical anomalies in road deterioration (high acceleration).

Figure 7.

Road anomaly plot.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of statistically significant roughness anomalies (z ≥ 2) across Pretoria, South Africa. Warmer colors represent higher acceleration magnitude z-scores, identifying segments that require urgent maintenance. Visualization supports data-driven prioritization and integration into municipal asset-management systems.

Repeated road IDs indicate multiple critical segments on the same road. These road segments were prioritized for urgent maintenance. Extremely high z-scores were re-verified to rule out scaling or unit inconsistencies; values reflect rare but valid spikes in vertical acceleration magnitude. Values at z ≈ 2.00 correspond to the threshold boundary; we include them to illustrate the cut-off. The results support data-driven decision-making, allowing transportation agencies to allocate resources based on real-time deterioration trends.

While the anomaly detection framework effectively identifies critical segments within the Pretoria dataset, the robustness of these models under varying road and vehicular conditions remains a key consideration. The next subsection therefore evaluates the framework’s potential generalization and transferability to broader contexts.

4.7. Generalization Potential

Although models were trained on Pretoria data, the methodology is transferable to other cities and vehicle fleets. Future domain adaptation experiments should test robustness under varying pavement types (rigid/flexible), vehicle suspensions, tire pressures, and weather conditions. Such validation will ensure scalability for regional road-network monitoring.

These insights collectively demonstrate that the proposed framework can be adapted across heterogeneous environments while maintaining its predictive accuracy. The following section integrates these findings within the wider body of related research and discusses their practical and policy implications.

5. Discussion, Limitations and Future Work

5.1. Discussion

The preceding subsections have demonstrated that the proposed machine learning framework achieves robust, interpretable, and transferable performance for road roughness severity classification and predictive maintenance. By integrating validation, model agreement analysis, feature importance interpretation, and anomaly detection, the study establishes both statistical and operational credibility. This section consolidates these results within the context of prior research on vibration-based pavement monitoring and discusses their broader implications for transport infrastructure management in data-scarce urban environments such as Pretoria.

Machine learning-based pavement assessment has evolved rapidly over the past decade, with most prior works emphasizing either vibration signal classification or deep-learning model optimization in isolation. Regarding recent vibration-based studies, ref. [11] achieved approximately 86% accuracy using low-cost smartphone accelerometers, while the authors of [28] reported between 98.9% and 100% accuracy for unsprung-mass vibration-based roughness recognition under simulation and real-vehicle tests. By comparison, the present study contributes an integrated framework that extends beyond classification accuracy. Unlike those single-stage models, the proposed approach couples ISO-referenced severity labeling with ensemble and deep classifiers, McNemar-based agreement testing, feature importance interpretation, statistical anomaly detection, and GIS-based maintenance prioritization. This multi-layer integration delivers an interpretable and transferable pipeline suited to operational deployment by road-management authorities.

While individual components such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and CNN have been independently explored in previous research, the novelty of this work lies in unifying these components into a single, validated decision-support pipeline. The holistic design yields competitive accuracy and simultaneously produces GIS-ready anomaly maps and maintenance-priority indices, bridging the gap between analytical prediction and actionable infrastructure management. The unified framework therefore transforms stand-alone predictive models into an operational decision-support system that is both technically robust and contextually adaptable to resource-constrained urban environments.

Beyond its technical merit, the framework’s modular structure supports future integration with Internet-of-Things (IoT) telematics platforms and real-time fleet data acquisition systems. Such interoperability will enable continuous monitoring and automatic anomaly reporting, shortening inspection cycles from months to hours and ensuring the optimal allocation of maintenance funds. Nevertheless, several constraints remain: (i) the dataset originates from a single city and vehicle platform; (ii) environmental variables such as temperature and precipitation were not yet incorporated; and (iii) external validation against International Roughness Index (IRI) measurements and expert survey data is still pending. Addressing these limitations will further enhance real-world reliability and scalability.

Overall, the findings confirm that combining supervised learning with statistical anomaly detection provides a reliable, low-cost foundation for intelligent pavement management systems. The dominance of vertical acceleration underscores the feasibility of lightweight sensing, while the framework’s modular design facilitates adaptation across diverse geographic contexts. These outcomes collectively position the framework as a practical and extensible tool for municipal road agencies seeking to optimize maintenance scheduling and inform evidence-based transport asset planning. Although the present analysis focused on a single-vehicle platform and road network within the Pretoria metropolitan area, the framework was intentionally designed to be transferable across cities and vehicle types. Because the pipeline relies on relative vibration metrics (normalized accelerations and z-score anomalies) rather than absolute amplitude thresholds, retraining with new city-specific data can rapidly adapt the model to different suspension systems, payloads, and pavement typologies. Future work will extend the dataset to include multi-city recordings from varied climatic and traffic contexts across South Africa, enabling domain adaptation and robust generalization assessment. The ensuing section concludes the paper by summarizing key insights, outlining limitations, and identifying avenues for continued research and deployment.

5.2. Limitations

Despite its promising results, several limitations remain.

- Geographical scope: the dataset was collected from a single metropolitan area using one vehicle platform, limiting external generalization.

- Environmental and contextual variables: weather, traffic loading, and temperature influences were not incorporated and may affect vibration signatures.

- Reference benchmarking: external validation against standardized indices such as the International Roughness Index (IRI) and expert-based field assessments is pending.

- Sensor heterogeneity: the framework assumes consistent sampling from calibrated inertial sensors; performance may vary with different hardware and mounting positions.

In addition, the dataset represents one city and a single-vehicle configuration recorded during a limited climatic period; consequently, seasonal and vehicular variability were not captured. Future multi-city and multi-vehicle extensions, already planned under the same framework, will address these external-validity constraints and enable broader generalization.

5.3. Recommendations and Future Work

Future efforts should focus on the following objectives:

- Multi-modal data fusion, integrating environmental, traffic, and weather factors to improve prediction robustness;

- Hybrid deep architectures, such as CNN–LSTM or Transformer-based models, for capturing temporal dynamics of vibration signals;

- Edge deployment, using lightweight, single-axis sensors or embedded microcontrollers for on-board real-time inference;

- Benchmarking with IRI and profilometer data, ensuring cross-validation with established pavement standards; and

- Policy and cost–benefit integration, aligning predictive outputs with budget-allocation models for optimal maintenance planning.

By pursuing these directions, the framework can evolve into a fully automated, IoT-enabled infrastructure-monitoring ecosystem that supports proactive, sustainable road-network management.

6. Conclusions

This study presented a reproducible, low-cost, and interpretable machine learning framework for vibration-based road condition assessment and maintenance prioritization. By integrating ISO-referenced severity labeling, ensemble and deep classifiers, statistical anomaly detection, and GIS-based prioritization, the framework advances beyond predictive modeling to an operational decision-support tool. Evaluation using real-world data from Pretoria demonstrated robust performance across roughness severity categories, validating the dominant role of vertical acceleration as an indicator of surface irregularity.

The unified pipeline provides clear benefits for transport asset management, including improved interpretability, transparency through feature importance analysis, and actionable outputs for maintenance scheduling. Its modular structure also supports integration with Internet-of-Things (IoT) telematics and municipal GIS dashboards, enabling the near-real-time monitoring of pavement conditions. Overall, the study offers a practical, scalable, and adaptable approach for intelligent pavement management applications, particularly in resource-constrained urban environments. Future extensions will focus on broader geographic deployment, the incorporation of environmental and contextual variables, and benchmarking against standardized roughness indices to further strengthen reliability and generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.K., O.O.A., K.D. and L.D.; methodology, O.O.A.; software, O.O.A.; formal analysis, O.O.A.; investigation, O.O.A.; resources, O.O.A.; data curation, O.O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.O.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.K., K.D., L.D. and O.O.A.; visualization, O.O.A.; supervision, A.M.K. and L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was made possible through funding received from The Transport and Education Training Authority (TETA), project number: TETA22/R&K/PR0011.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made publicly available at the project repository upon publication; anonymized subsets are available to reviewers on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the funding provided by The Transport and Education Training Authority (TETA) for the execution of this research project. The encouragement and enabling environment from Tshwane University of Technology is appreciated herewith.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ADAS | Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems |

| CMIS | Committee Machine Intelligent System |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IRI | International Roughness Index |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| PINNs | Physics-Informed Neural Networks |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Program Codes

https://github.com/ajayioo/research_data_codes/blob/main/pretoria_roughroad_pro_newest.ipynb (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Appendix A.2. Data Collected (The Extracted New Dataset)

https://github.com/ajayioo/research_data_codes/blob/main/extracted_pretoria_road_data.csv (accessed on 20 October 2025).

Appendix A.3. Critical Road Summary File (After Road Roughness Ranking)

https://github.com/ajayioo/research_data_codes/blob/main/critical_road_summary.xlsx (accessed on 20 October 2025).

References

- Ajayi, O.O.; Kurien, A.M.; Djouani, K.; Dieng, L. Analysis of Road Roughness and Driver Comfort in ‘Long-Haul’ Road Transportation Using Random Forest Approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elseifi, M.A.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hassan, M.M. Machine Learning-Based Framework for Predicting Pavement Roughness and Aggregate Segregation During Construction. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2024, 150, 04024029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2631-1; Mechanical Vibration and Shock—Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration—Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Bajic, M.; Pour, S.M.; Skar, A.; Pettinari, M.; Levenberg, E.; Alstrøm, T.S. Road roughness estimation using machine learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.01199. [Google Scholar]

- Gorges, C.; Hoven, C.; Dellwig, C. Impact Detection: A Machine Learning Approach for Experimental Road Roughness Classification. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2019, 132, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, J. Pavement distress detection using 1D convolutional neural networks with acceleration sensor data. Sensors 2020, 20, 5244. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yu, X. Pavement Roughness Grade Recognition Based on One-Dimensional Residual Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karballaeezadeh, N.; Zaremotekhases, F.; Shamshirband, S.; Mosavi, A.; Nabipour, N.; Csiba, P.; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R. Intelligent Road Inspection with Advanced Machine Learning; Hybrid Prediction Models for Smart Mobility and Transportation Maintenance Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegazzo, J.; Von Wangenheim, A. Road Surface Type Classification Based on Inertial Sensors and Machine Learning: A Comparison Between Classical and Deep Machine Learning Approaches for Multi-Contextual Real-World Scenarios. Computing 2021, 103, 2143–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Chen, S.; Alinizzi, M.; Alamaniotis, M.; Labi, S. Estimating IRI based on pavement distress type, density, and severity: Insights from machine learning techniques. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.05413. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Meocci, M.; Dolfi, M.; Branzi, V.; Morosi, S.; Argenti, F.; Berzi, L.; Consumi, T. Road Surface Anomaly Assessment Using Low-Cost Accelerometers: A Machine Learning Approach. Sensors 2022, 22, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariatfar, M.; Lee, Y.-C.; Choi, K.; Kim, M. Effects of flooding on pavement performance: A machine learning-based network-level assessment. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2022, 7, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Leng, Z.; Jiang, J.; Ni, F. Modelling of pavement performance evolution considering uncertainty and interpretability: A machine learning-based framework. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 5211–5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, A.; Shoghli, O.; Sabeti, S.; Tabkhi, H. Multi-Asset Defect Hotspot Prediction for Highway Maintenance Management: A Risk-Based Machine Learning Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.K.; Arya, D.; Kumar, A.; Maeda, H.; Sekimoto, Y. Road rutting detection using deep learning on images. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022. [Google Scholar]