Abstract

This study assessed whether permitting certified recycled aggregate companies to assign both quality and environmental management responsibilities to a single individual affects the effectiveness of post-certification quality management. Using data from 242 post-certification audits conducted in 2023, six regulatory audit items were quantified using a binary scoring scheme to produce a six-point score for each company. Audit outcomes were compared between companies employing dedicated quality managers (n = 147) and those operating with concurrently appointed managers (n = 95). Before conducting hypothesis testing, skewness, kurtosis, and F-tests were used to verify approximate normality and homogeneity of variances. Two-sample t-tests assuming equal variances revealed no statistically significant differences between the two personnel structures, and the effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.072) indicated negligible practical differences. Additionally, 52 companies (22%) experienced changes in their quality management personnel during the audit period. A separate comparison between companies with and without such changes also showed no statistically significant differences, with a small effect size (d = 0.276). These results suggest that the 2022 regulatory revision authorizing concurrent appointments did not exert any discernible adverse influence on post-certification audit performance and that additional administrative requirements for managing personnel changes may be unnecessary. The findings also highlight recurring deficiencies—particularly in quality testing and equipment management—which warrant continued attention from policymakers, certification bodies, and certified companies seeking to enhance the effectiveness of the recycled aggregate quality certification system.

1. Introduction

On 23 December 2021, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) enacted the 16th amendment to the Regulation on Quality Certification and Management of Recycled Aggregate [1], followed by the 11th amendment to the Instructions for Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregate on 2 November 2022 [2]. These revisions permitted quality managers at certified recycled aggregate companies to concurrently serve as environmental managers. In the 2023 post-certification audits conducted soon after these revisions, 95 out of 242 certified companies (approximately 39%) were found to have adopted such concurrent appointments.

This study investigates whether allowing a single individual to manage both quality and environmental duties affects the effectiveness of post-certification quality management for certified recycled aggregates, compared with the previous system in which each role was assigned to dedicated personnel. Specifically, it examines whether the revised provisions constitute a reasonable regulatory relaxation by testing for statistically significant differences in audit outcomes between the two personnel assignment structures. Using data from 242 post-certification audits conducted in 2023 by the Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology (KICT), the analysis compares quantitative scores for six on-site audit items between companies managed by dedicated personnel and those managed by concurrently appointed personnel.

In addition, multiple cases were identified in which quality management personnel were replaced, often in connection with concurrent appointments. The study therefore also examines the impact of personnel changes on audit results and considers whether enhanced personnel management—such as mandatory reporting of personnel changes to the certification authority, similar to the Korean Industrial Standards (KS) certification system—would be warranted. To this end, the six audit item scores are compared between companies with and without personnel changes to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between the two groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Trends on Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregates

Previous studies in Korea have examined multiple dimensions of recycled aggregate quality certification, including the development of standards, certification procedures, and post-certification management. Lee et al. discussed the establishment of technical quality standards and proposed implementation strategies for the certification system [3]. Lee and Lee analyzed the KS certification process and related quality assurance mechanisms, thereby contributing to the institutional foundation for recycled aggregate management [4]. Jeon investigated the relationship between post-certification document reviews and laboratory test results for certified recycled coarse aggregates [5] and later evaluated the validity of multi-stage testing procedures used within the certification framework [6]. Jeon also reviewed the regulatory evolution of Korea’s recycled aggregate quality certification system, providing context for recent amendments and institutional reforms [7].

Beyond domestic research, international literature has addressed the technical, managerial, and institutional aspects of construction and demolition (C & D) waste management and recycled aggregate utilization. Prior studies have examined national-level waste management systems and policy development related to recycled aggregate production [8], global trends in recycled aggregate properties and performance [9], and stakeholder perceptions, barriers, and behavioral factors influencing the adoption of recycled construction materials [10]. Additional studies have proposed performance evaluation and classification systems for recycled concrete aggregates (RCA), demonstrating how quality parameters can be linked to material performance and offering comparative frameworks relevant to certification criteria [11,12,13]. Furthermore, certification schemes such as the Product Conformity Certification Scheme for Aggregates for Concrete administered by the Hong Kong Concrete Institute exemplify how third-party conformity assessment mechanisms are used in other jurisdictions to ensure aggregate quality [14].

By synthesizing domestic and international research, this section provides a comprehensive overview of current trends in recycled aggregate quality certification and C & D waste management. These findings establish a contextual foundation for the empirical analyses that follow and support the relevance of examining both personnel assignment structures and post-certification management practices within Korea’s certification system.

2.2. Institutional Framework of Recycled Aggregate Quality Certification

The recycled aggregate quality certification system aims to enhance user confidence, improve production practices, and promote the supply of high-quality recycled aggregates. It also contributes to national resource efficiency by encouraging recycling and resource conservation through a process that includes on-site inspections and quality testing prior to certification. Among the regulatory components relevant to this study, two areas—post-certification management and the concurrent appointment of personnel—were the focus of recent amendments to the regulation and instructions.

First, with respect to post-certification management, the scope of exemptions was expanded and the procedures for addressing nonconformities were revised. Under Article 15 of the regulation, certification bodies must conduct at least one post-certification audit each year for certified companies. Previously, exemptions were granted only to companies that had undergone on-site inspections within the preceding year. The amendment introduced an additional exemption for companies whose quality test results from the previous year were satisfactory, substantially increasing the number of companies eligible for exemption [1].

Second, regarding the concurrent appointment of personnel, maintaining certification requires the assignment of four management roles: a management supervisor, quality manager, environmental manager, and safety manager, as summarized in Table 1. The quality manager must hold a relevant professional license or meet experience requirements and complete training in recycled aggregate quality management, whereas the environmental manager must possess a relevant qualification or meet the required experience standard. The quality manager oversees the company’s quality policy and quality control activities, while the environmental manager is responsible for implementing the company’s environmental policy and managing environmental performance.

Table 1.

Manpower requirements.

The management supervisor is typically the chief executive officer, and the safety manager position has no specific qualification requirements. Consequently, fulfilling the eligibility requirements for the quality and environmental managers is generally more demanding. Prior to the revision, the quality and environmental manager roles had to be performed by separate personnel, effectively requiring at least four designated staff members. After the amendment allowed the quality manager to concurrently serve as the environmental manager, many companies began assigning three personnel: a management supervisor, a safety manager, and a combined quality and environmental manager. As shown in Table 2, the qualification requirements for quality managers already encompassed those for environmental managers, which explains the rapid increase in concurrent appointments.

Table 2.

Detailed manpower requirements.

Under Article 14 of the regulation and Article 12 of the instructions, the quality manager is the key individual responsible for quality management activities at certified companies and must sign both the sample collection verification form (Attached Form 1) and the on-site audit checklist (Attached Form 2 of the operational guidelines). Among the four management roles, the quality manager is subject to the most stringent qualification and mandatory training requirements. However, the current regulations do not provide formal procedures for notifying or obtaining approval from the certification authority when the quality manager is replaced.

In addition, corresponding KS specifications exist for recycled aggregates depending on their application, including KS F 2574 (Recycled Aggregate for Subbase) [15], KS F 2573 (Recycled Aggregates for Concrete) [16], and KS F 2572 (Recycled Aggregates for Asphalt Concrete Pavement) [17]. Under the KS certification system, companies must submit the relevant qualification documents to the certification body via the Korean Standards Association platform when the quality manager is replaced, as required by KS Q 8001 KS Certification Scheme—General Requirements for Product Certification [18]. If a vacancy occurs during the transition, a management plan addressing the gap period must also be submitted, and failure to comply may result in suspension of KS certification.

2.3. Research Method

According to Article 36 of the Construction Waste Recycling Promotion Act [19] and Article 15 of the regulation, certification bodies must conduct at least one post-certification audit per year for companies holding recycled aggregate quality certification. The proviso to Article 15 (1) further stipulates that companies whose quality test results were satisfactory and free from administrative penalties in the previous year may be exempted from the following year’s audit. In 2023, a total of 242 companies (corresponding to 311 certifications) underwent post-certification audits. Among these, 95 companies (approximately 39%) had quality managers concurrently serving as environmental managers.

This study quantified the results of six post-certification audit items—including construction waste management—using a six-point scale and compared the outcomes between two groups: 147 companies managed by dedicated personnel and 95 companies managed by concurrently appointed personnel. This procedure followed the same scoring methodology applied in the 2020 study on recycled coarse aggregates [5]. As summarized in Table 3, each audit item was assigned a score of 1 when no corrective action was required and 0 when corrective action was needed, resulting in a total score ranging from zero to six. A two-sample t-test assuming equal variances was then applied to determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the mean audit scores of the two groups.

Table 3.

Detailed audit items.

The t-test is a statistical method used to determine whether the means of two independent groups differ significantly based on estimated variances or standard deviations from sample data. In this study, a two-sample t-test assuming equal variances was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2019 to evaluate whether the difference in mean audit scores between the two personnel assignment groups was statistically significant.

In addition, 52 of the 242 audited companies (approximately 22%) experienced changes in their quality management personnel. A detailed classification of these cases by personnel assignment type is presented in Table 4. Among the 147 companies managed by dedicated personnel, 20 cases (13.6%) involved personnel changes, compared with 32 cases (33.7%) among the 95 companies with concurrent personnel. This indicates that personnel turnover occurred approximately 2.48 times more frequently in companies with concurrently assigned managers.

Table 4.

Case with (without) personnel change.

Using the same quantitative approach applied in the comparison between dedicated and concurrent personnel, the six audit items were again scored on a six-point scale for companies with and without personnel changes. A two-sample t-test assuming equal variances was then conducted to determine whether the mean audit scores differed significantly between the two groups.

To assess the suitability of parametric analysis, the distributional characteristics of the six-point audit score were examined prior to hypothesis testing. Skewness and kurtosis values for the dedicated (kurtosis = 3.33, skewness = −1.95), concurrent (3.35, −1.81), no-change (4.85, −2.18), and change (−0.26, −1.07) groups fell within commonly accepted empirical thresholds for approximate normality (|skewness| < 2–3; |kurtosis| < 7), as widely cited in applied statistical research [20,21]. The sample sizes also satisfied established criteria for robustness, as previous simulation studies have shown that the two-sample t-test remains reliable under moderate non-normality when group sizes exceed approximately 30–40 cases [22,23,24]. In the present study, all group sizes exceeded this threshold (147 vs. 95 and 190 vs. 52), supporting the appropriateness of the t-test despite the discrete nature of the six-point scale.

Homogeneity of variances was evaluated using F-tests. For the comparison between dedicated and concurrent personnel, F = 1.0468 (one-tailed p = 0.40897), and for the comparison between no-change and change groups, F = 0.8506 (one-tailed p = 0.21846). In both cases, the null hypothesis of equal variances could not be rejected, thereby justifying the use of the equal-variance two-sample t-test in the subsequent analyses.

3. Results: Management Audit Results for Recycled Aggregates

3.1. 2023 Post-Certification Audit Targets

As noted earlier, post-certification audits were conducted for 242 companies in 2023. Because some companies held multiple certifications, the total number of certifications subject to audit was 311. Table 5 summarizes the distribution of these certifications. According to Article 5 of the regulation, recycled aggregates are certified for four primary applications: road construction, concrete and concrete product manufacturing (coarse and fine aggregates), and recycled asphalt concrete production. Following the notation system defined in Appendix Table 3 of the Detailed Operational Guidelines for Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregate [25], these categories are represented as follows: R for road construction, C for coarse aggregate, F for fine aggregate, and A for asphalt concrete.

Table 5.

Subject of follow-up management audit in 2023.

Table 5 presents the audit targets using these category codes, along with composite certifications such as RC, RF, RA, RCF, RCA, and CA. The 311 certifications corresponded to 242 distinct companies subject to post-certification audits. This classification provides an overview of the types and combinations of recycled aggregate products produced by the audited companies and establishes the basis for the subsequent analysis of audit outcomes.

3.2. 2023 Post-Certification Audit Results

During the 2023 post-certification audits of recycled aggregates, evaluations were conducted using the Operational Status Inspection Checklist for Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregates (Attached Form 2 of the Detail Instructions) [25]. The audit consists of six items: construction waste management; management of aggregate production and weighing facilities; quality management organization and activities; quality testing and testing equipment; supply performance management; and environmental and safety management.

Each audit item was assigned a score of 1 if no corrective action was required and 0 if corrective action was necessary, resulting in a maximum possible score of six points. Using this scoring system, all 242 audit cases were quantified. Among them, 165 cases achieved a perfect score of six points, indicating the absence of any corrective items, whereas 77 cases required at least one corrective action. The lowest score observed was one point, corresponding to cases in which corrective actions were required for five of the six items. The overall mean score across all cases was 5.41. Table 6 summarizes the average score for each audit item. Supply performance management recorded the highest mean score of 1.00, with no corrective items in any case, whereas quality testing and testing equipment recorded the lowest mean score of 0.83, indicating the most frequent deficiencies.

Table 6.

Audit results by item.

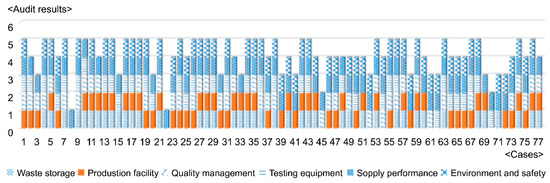

Figure 1 illustrates the results for the 77 cases that required corrective action. The vertical stacked bar chart shows, for each case, the audit items that were rated satisfactory. For example, the first case scored 5 points because only the construction waste management item required corrective action, whereas the eighth case scored 1 point because corrective actions were required for supply performance management and five other items.

Figure 1.

Audit results for the 77 cases with at least one nonconformity.

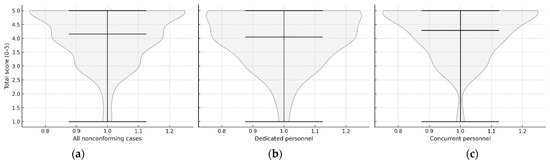

Figure 2 presents violin plots of the total audit scores for (a) all nonconforming cases (n = 77), (b) dedicated personnel cases (n = 42), and (c) concurrent personnel cases (n = 35). These plots summarize score distributions, medians, and variability for each group, complementing the item-level patterns shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3. The results show that most cases cluster within the 4–5 point range, with relatively few low-scoring cases (1–2 points) across all groups. The distributions for the dedicated and concurrent groups exhibit broadly similar patterns, consistent with the statistical results reported in Section 3.4. The visualization provides contextual insight into performance variation both within and between the two personnel assignment groups.

Figure 2.

Scores of nonconforming cases: (a) All; (b) dedicated manager; (c) concurrent manager.

Figure 3.

Audit results for dedicated manager with at least one nonconformity.

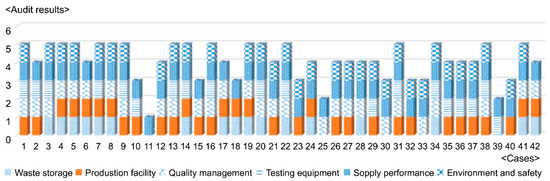

3.3. Audit Results for Companies with Dedicated Management Personnel

Of the 242 audit cases, 147 involved companies managed by dedicated personnel without concurrent appointments. Using the same scoring criteria described earlier, 105 of these cases achieved a perfect score of six points, whereas 42 cases required one or more corrective actions. The lowest score observed was one point, corresponding to cases in which corrective actions were required for five of the six audit items. The overall mean score for the 147 cases was 5.44. Table 7 summarizes the average score for each audit item. Supply performance management again recorded a mean score of 1.00, with no corrective items in any case, whereas construction waste management recorded the lowest mean score of 0.83, indicating the highest frequency of deficiencies among the six items.

Table 7.

Audit results for dedicated manager by item.

Figure 3 illustrates the results for the 42 nonconforming cases, using a vertical stacked bar chart to show the audit items rated satisfactory in each case. This visualization highlights the distribution of deficiencies among the six audit items and provides additional context for interpreting item-level performance patterns within the dedicated management group.

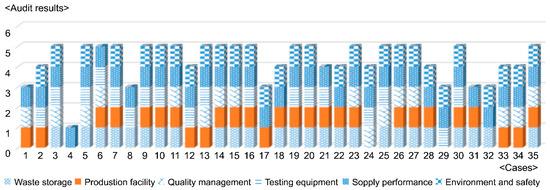

3.4. Audit Results for Companies with Concurrent Management Personnel

Among the 242 total audit cases, 95 involved companies in which the quality manager concurrently performed environmental management duties. Using the same scoring method described earlier, 60 of these cases achieved perfect scores of six points, whereas 35 cases required one or more corrective actions. The lowest score observed was one point, representing cases in which corrective actions were required for five of the six audit items. The overall mean score for the 95 cases was 5.37. Table 8 summarizes the average scores for each audit item. Supply performance management again recorded a mean score of 1.00, with no corrective items across all cases, whereas quality management organization and activities recorded the lowest mean score of 0.80, indicating the highest frequency of deficiencies among the six items.

Table 8.

Audit results for concurrent managers by item.

Figure 4 illustrates the results for the 35 nonconforming cases as a vertical stacked bar chart, indicating the audit items evaluated as satisfactory in each case. This visualization highlights the distribution and nature of deficiencies within the concurrent management group and provides a basis for comparing the performance of dedicated and concurrently assigned personnel.

Figure 4.

Audit results for concurrent manager with at least one nonconformity.

3.5. Audit Results by Personnel Changes

Of the 242 audited companies, 190 had no change in their quality management personnel, while 52 experienced personnel changes. The audit results for both groups were quantified using the same six-point scoring system applied throughout this study, and the average score for each audit item is presented in Table 9. Among the companies without personnel changes, quality testing and testing equipment recorded the lowest mean score (0.85), consistent with the overall findings reported in Section 3.2. In contrast, among the companies that experienced personnel changes, the lowest mean score (0.71) was observed for quality management organization and activities, similar to the pattern reported for companies with concurrent personnel in Section 3.4.

Table 9.

Audit results without/with personnel change.

Before comparing the mean audit scores of the two groups, the distributional characteristics of the six-point scores were examined. The skewness and kurtosis values for both groups fell within empirical thresholds commonly cited in the literature, indicating acceptable levels of non-normality [18,19]. Homogeneity of variances was assessed using F-tests, which showed no statistically significant variance differences between groups (F = 1.0468, p = 0.40897; F = 0.8506, p = 0.21846). Accordingly, subsequent comparisons were conducted using the equal-variance two-sample t-test to evaluate whether statistically significant differences existed between the groups with and without personnel changes.

4. Discussion

A null hypothesis was established to examine whether the audit results differed between companies managed by dedicated personnel (147 cases) and those managed by concurrently appointed personnel (95 cases). The audit scores for both groups were quantified as described earlier and analyzed using a two-sample t-test assuming equal variances. As shown in Table 10, the two-tailed p-value of 0.585 exceeded the significance level of 0.05, indicating that the null hypothesis could not be rejected. The t-statistic of 0.546 was also smaller than the critical two-tailed t-value of 1.970, further confirming the absence of a statistically significant difference between the two personnel assignment structures.

Table 10.

t-Test of audit results (by dedicated/concurrent management).

A second null hypothesis was formulated to examine whether audit results differed between companies whose quality management personnel remained unchanged (190 cases) and those that experienced personnel changes (52 cases). The results of the two-sample t-test assuming equal variances are summarized in Table 11. The two-tailed p-value of 0.079 exceeded the significance threshold, and the t-statistic of 1.764 was less than the critical t-value of 1.970. Consequently, the null hypothesis could not be rejected, indicating no statistically significant difference between companies with and without personnel changes in their quality management positions.

Table 11.

t-Test of audit results (by without/with personnel change).

In addition to statistical significance testing, the practical magnitude of the observed differences was examined using effect size calculations. The effect sizes were small for both comparisons (Cohen’s d = 0.072 for dedicated vs. concurrent personnel and d = 0.276 for no-change vs. change cases). Given the narrow 0–6 scoring range, these effect sizes indicate limited practical impact even when numerical differences exist between group means. This finding is consistent with the non-significant t-test results and further supports the conclusion that the observed group differences do not represent substantively meaningful disparities in audit performance.

To complement these statistical findings, item-level performance was examined to identify areas where deficiencies were most frequently observed. For the full sample of 242 cases, the “Testing & Equipment” item recorded the lowest score (0.83), primarily due to recurring deficiencies in the periodic calibration of testing equipment (Table 6). Among companies managed by dedicated personnel, “Waste Storage” recorded the lowest score (0.83), largely due to insufficient segregation or compartmentalization within construction waste storage facilities (Table 7). In contrast, among companies with concurrent personnel, “Quality Management” recorded the lowest score (0.80), mainly attributable to incomplete fulfillment of mandatory periodic training for quality management staff (Table 8). A similar pattern was observed in the personnel change analysis: among companies without personnel changes, “Testing & Equipment” again recorded the lowest score (0.85), whereas among companies with personnel changes, “Quality Management” recorded the lowest score (0.71), with contributing factors including incomplete training and unmet qualification requirements, such as missing certificates or insufficient relevant experience (Table 9).

Taken together, these findings indicate that neither the assignment structure of management personnel (dedicated vs. concurrent) nor personnel changes produced statistically significant differences in overall audit scores. However, item-level analyses revealed recurring deficiencies—such as inadequate calibration of testing equipment, insufficient management of waste storage areas, and incomplete training or unmet qualification requirements for quality personnel. Although these item-specific shortcomings did not translate into statistically significant differences at the group level, their repeated appearance suggests that certain operational weaknesses continue to affect post-certification audit outcomes. These patterns highlight the importance of monitoring specific audit items that consistently show deficiencies and provide useful insights for improving ongoing post-certification management practices.

5. Conclusions

Following the revision of the regulation and instructions, concurrent appointments of quality and environmental managers were permitted, and 95 companies (39%) adopted concurrent appointments in practice. To evaluate whether companies managed by concurrently appointed personnel maintained quality management performance comparable to those managed by dedicated personnel, this study analyzed 242 post-certification on-site audits conducted in 2023.

The key findings are as follows:

- The average audit score was 5.44 for companies with dedicated management personnel and 5.37 for those with concurrently appointed personnel, showing a slightly higher score in the dedicated personnel group.

- Comparative analysis under the null hypothesis of no difference between the two groups showed that the p-value exceeded the significance level and the t-statistic was smaller than the critical t-value, indicating no statistically significant difference in audit results.

- Concerns that quality management might deteriorate following the introduction of concurrent appointments were not supported by the 2023 audit results. Statistically, the concurrent appointment of quality and environmental managers did not result in any measurable decline in quality management performance. Accordingly, the regulatory amendments allowing concurrent appointments may be regarded as a reasonable form of regulatory relaxation.

The study also examined whether changes in quality management personnel affected post-certification audit outcomes. The findings are as follows:

- The average audit score was 5.47 for companies without personnel changes and 5.19 for those with personnel changes, showing a slightly higher score in the former group.

- A comparative analysis conducted under the null hypothesis of no difference between the two groups found that the p-value exceeded the significance level and the t-statistic was smaller than the critical t-value. Consequently, no statistically significant difference was identified between companies with and without personnel changes.

- Given the absence of a statistically significant difference, it appears unnecessary to strengthen personnel change management requirements—such as mandatory reporting procedures—similar to those in the KS certification system.

These results provide useful implications for stakeholders involved in the recycled aggregate quality certification system. For policymakers, the absence of significant performance differences between dedicated and concurrently appointed personnel suggests that allowing flexibility in personnel assignment does not undermine audit performance. For certification bodies, the recurring deficiencies identified in certain audit items may help refine priorities in post-certification monitoring. For certified companies, the findings highlight the need to improve internal management practices in areas that frequently exhibit nonconformities.

Additional statistical checks reinforced the robustness of the comparative analyses. Although the six-point audit score is discrete, the skewness and kurtosis values remained within commonly accepted empirical thresholds [20,21], and the large sample sizes helped maintain the robustness of the t-test under moderate non-normality [22,23,24]. Furthermore, the absence of significant variance differences between groups supported the use of the equal-variance two-sample t-test. Collectively, these considerations affirm that the analytical conclusions of this study are statistically sound and methodologically reliable.

Finally, this study has a limitation in that it analyzed only 242 on-site post-certification audits conducted in 2023. Further research encompassing different time periods, application types, or quality test results may yield more comprehensive and generalizable findings. In addition, because audit scores were highly concentrated in the upper range across certified companies, the ability to detect performance variation may have been constrained. Moreover, the checklist-based nature of the audit process introduces potential subjectivity, which should be acknowledged as an additional limitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-M.J.; methodology, S.-M.J.; software, S.-M.J.; validation, S.-M.J. and M.-J.K.; formal analysis, S.-M.J.; investigation, S.-M.J. and M.-J.K.; resources, M.-J.K.; data curation, S.-M.J. and M.-J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-M.J.; writing—review and editing, S.-M.J.; visualization, S.-M.J. and S.-H.K.; supervision, S.-H.K.; project administration, S.-H.K.; funding acquisition, S.-H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology (KICT), grant number 20250030-001 (2025 Recycled Aggregate Certification Project).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KATS | Korean Agency for Technology and Standards |

| KICT | Korea Institute of Civil Engineering and Building Technology |

| KS | Korean Industrial Standards |

References

- The Regulation on Quality Certification and Management of Recycled Aggregate; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?section=&menuId=1&subMenuId=15&tabMenuId=81&eventGubun=060101&query=%EC%88%9C%ED%99%98%EA%B3%A8%EC%9E%AC#undefined (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Instructions for Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregate; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://www.molit.go.kr/USR/I0204/m_45/dtl.jsp?gubun=&search=%EC%88%9C%ED%99%98%EA%B3%A8%EC%9E%AC&search_dept_id=&search_dept_nm=&old_search_dept_nm=&psize=10&search_regdate_s=&search_regdate_e=&srch_usr_nm=&srch_usr_num=&srch_usr_year=&srch_usr_titl=Y&srch_usr_ctnt=&lcmspage=1&idx=17621 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Lee, S.H.; Hwang, S.D.; Song, T.H.; Sim, J.W.; Lee, J.C.; Kim, Y.S.; Jeong, J.Y.; Song, Y.C. A Study of Establishment of Quality Standard of Recycled Aggregate and Implementation Plan of the Certification System; Project No.: 04-A08-01; Korea Institute of Civil Engineering & Building Technology: Goyang, Republic of Korea, 2006; p. 737. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, T.S. Research for KS Certification and Quality Assurance of Recycled Aggregate; Publication No.: 11-1613000-001801-01; Korea Institute of Civil Engineering & Building Technology: Goyang, Republic of Korea, 2017; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.M. Follow-up management and test results for certified recycled coarse aggregates for concrete: A review. J. Korea Soc. Waste Manag. 2021, 38, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.M. Study on the validity of tertiary testing of certified recycled coarse aggregates based on the analysis of follow-up audits. J. Korea Soc. Waste Manag. 2022, 39, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.M. Comprehensive review of the evolution and key amendments in the 16th regulation on quality certification and management of recycled aggregate. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2023, 23, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Construction and Demolition Waste Management in Korea: Recycled Aggregate and Its Application. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 2223–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yan, L.; Fu, Q.; Kasal, B. A Comprehensive Review on Recycled Aggregate and Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 171, 105565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtarian, S.; Caldera, S.; Maqsood, T.; Ryley, T. Using Recycled Construction and Demolition Waste Products: A Review of Stakeholders’ Perceptions, Decisions, and Motivations. Recycling 2020, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, G.J.; Raj, P.; Kumar, R. Performance of Quality-Controlled Recycled Concrete Aggregates. ACI Mater. J. 2024, 121, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, G.J. Recycled Concrete Aggregate Classification Based on Quality Parameters and Performance. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2023, 47, 3211–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Du, H. Performance Evaluation and Classification System of Recycled Concrete Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Concrete Institute (HKCI). Product Conformity Certification Scheme—Aggregates for Concrete (PCCS-AC); Issue 1, 2015; Hong Kong Concrete Institute: Hong Kong, China, 2015; Available online: https://www.hongkongci.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PCCS_Aggregates-for-Concrete-ISSUE-1-2015-1.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- KS F 2574; Recycled Aggregate for Subbase. Korea Agency for Technology and Standards: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. Available online: https://www.ks.or.kr/library/search/stddetail.do?itemNo=K001010143037&itemCd=K00101 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- KS F 2573; Recycled Aggregates for Concrete. Korea Agency for Technology and Standards: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: https://www.ks.or.kr/library/search/stddetail.do?itemNo=K001010149828&itemCd=K00101 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- KS F 2572; Recycled Aggregates for Asphalt Concrete Pavement. Korea Agency for Technology and Standards: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. Available online: https://www.ks.or.kr/library/search/stddetail.do?itemNo=K001010144619&itemCd=K00101 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- KS Q 8001; KS Certification Scheme-General Requirements for Product Certification. Korea Agency for Technology and Standards: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. Available online: https://www.ks.or.kr/library/search/stddetail.do?itemNo=K001010149306&itemCd=K00101 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- The Construction Waste Recycling Promotion Act; Article 36; Ministry of the Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2023. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsSc.do?section=&menuId=1&subMenuId=15&tabMenuId=81&eventGubun=060101&query=%EA%B1%B4%EC%84%A4%ED%8F%90%EA%B8%B0%EB%AC%BC%EC%9D%98+%EC%9E%AC%ED%99%9C%EC%9A%A9%EC%B4%89%EC%A7%84%EC%97%90+%EA%B4%80%ED%95%9C+%EB%B2%95%EB%A5%A0#undefined (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanca, M.J.; Alarcón, R.; Arnau, J.; Bono, R.; Bendayan, R. Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicológica 2017, 38, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerland, M.W. t-tests, non-parametric tests, and large studies—A paradox of statistical practice? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detail Instructions for Quality Certification of Recycled Aggregate; Attached Table 3; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2017. Available online: https://www.kict.re.kr/governmentWeb/getGovernmentContentsView.es?mid=a10602050000&pid=93&id=2070&keyWord= (accessed on 18 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).