1. Introduction

For most Turkic languages, there is a severe lack of large open audio corpora, especially those containing parallel transcriptions and translations [

1]. This problem significantly hinders the development of speech processing technologies such as automatic speech recognition (ASR), text-to-speech (TTS), and especially machine translation of spoken language [

2]. Unlike languages with global coverage, such as English, Chinese, or Spanish, Turkic languages are rarely represented in international multimodal corpus collection initiatives. Even for the relatively well-resourced Turkish language, audio corpora with accurate speech-to-text alignment—and even more so with translations into other languages—are the exception rather than the rule. This shortage of structured and slim audio resources greatly limits the ability to design and train effective models that can handle the phonetic complexity, prosody, and morphological richness inherent to these languages. Among the Turkic language family, Turkish remains the most developed in terms of available speech corpora and audio technologies, supported by commercial applications and a growing set of open datasets. In contrast, Central Asian Turkic languages remain underrepresented mainly in global speech technology efforts, not to mention languages where such resources are either absent altogether or are presented as small, fragmented collections that do not meet the requirements of machine learning. The lack of such corpora not only increases the cost of developing and training language models and diminishes the accuracy of speech technologies but also significantly affects the digital landscape, restricting the presence and use of Turkic languages in this increasingly vital domain.

One of the key challenges in creating parallel audio corpora for Turkic languages is the quality and origin of the available speech data. Since there are virtually no targeted recordings of speech in these languages in the public domain, researchers are forced to collect audio materials from secondary sources such as radio broadcasts, TV shows, podcasts, or YouTube videos. However, such data usually contains much noise—background sounds, echo recordings, background music, interruptions, recording defects, and other acoustic artifacts such as reverberation or distortion—that significantly complicate ASR. Moreover, such sources are rarely accompanied by accurate, aligned transcriptions, making it impossible to use these data for model training without prior, labor-intensive annotation.

Aligning audio fragments with parallel texts at the sentence or word level (forced alignment) is a task that demands tremendous time and computational resources. In the absence of reliable language models and specialized tools, the task becomes virtually impossible to solve. This is especially true for Turkic languages, which have the potential to benefit significantly from fully developed and stable ASR and TTS systems. However, these systems are either non-existent or in the experimental stage and currently lack the accuracy and reliability for widespread use. The formation of synthetic parallel speech corpora in Turkic languages is hindered not only by the shortage of structured resources but also by the lack of the technical infrastructure needed for their effective processing and subsequent integration into machine learning systems and intelligent technologies. Overcoming these challenges is crucial to realizing the potential of ASR and TTS systems for Turkic languages.

Modern multilingual automatic speech recognition models, such as Whisper [

3], Massively Multilingual Speech (MMS) [

4], and Soyle Automatic Speech Recognition Model (Soyle) [

5], demonstrate impressive results for widely spoken Turkic languages; however, their efficiency decreases significantly when working with rare and low-resource languages. For Turkic languages, this is reflected in a high proportion of speech recognition errors (Word Error Rate, WER), especially in the presence of dialectal features, non-standard phonetics, and limited training material. In addition, models pre-trained on one Turkic language often do not demonstrate satisfactory transferability to other related languages such as Uzbek, Kyrgyz, or Turkmen. Despite their genetic and typological closeness, differences in phonetics, intonation, alphabet, and orthographic norms create significant obstacles to effective interlingual transfer.

The scientific novelty of the proposed study lies in the creation of the first synthetic multilingual parallel audio corpus for Turkic languages, built on a unified, controlled methodology for “machine translation and its synthesis into speech” grounded in qualitative and synthetic data.

The paper is organized as follows: The Introduction discusses the resource scarcity issues for resource-poor Turkic languages.

Section 2 provides an overview of the literature and resources on speech technology and Natural Language Processing (NLP).

Section 2.1 provides an overview of high-resource multilingual speech corpora for speech-to-speech (S2S) and speech synthesis languages and their contributions to the field.

Section 2.2 details the resources available for Turkic languages and their applicability to language technologies.

Section 2.3 presents a comparative analysis of available audio and text resources for Kazakh, Tatar, Uzbek, and Turkish.

Section 3 describes the methods used in the study and consists of five subsections.

Section 3.1 discusses the creation of the audio corpus using a cascade scheme.

Section 3.2 discusses the methodology for creating audio corpora for Turkic languages using the text-first approach.

Section 3.3 describes text-to-speech systems developed for Turkic languages, including their features, limitations, and performance.

Section 3.4 provides a detailed discussion of the datasets used in the study. Finally,

Section 3.5 explains the metrics used to evaluate the quality of the resulting audio corpora and TTS systems. This section presents the results of the developed parallel audio corpora for the Kazakh–Turkish, Kazakh–Uzbek, and Kazakh–Tatar languages, as well as evaluations of synthesized speech quality using various metrics.

Section 5 discusses the results, challenges encountered, and an analysis of the obtained results. The article concludes with a summary of the main findings and suggests future directions for work on audio corpora of Turkic languages for speech technologies.

2. Related Works

In recent years, speech technologies have expanded beyond basic tasks focused solely on speech recognition ASR and TTS. Multilingual and multidialectal systems capable of operating under resource-constrained and non-standard scenarios are of increasing interest.

One of the key drivers of this development has been the availability of large, open corpora of speech and translation data, which have enabled the training and comparison of different models. Most of the currently available resources focus on European and major Asian languages. Despite the rich morphology and historical significance of Turkic languages, they remain underrepresented in modern speech research. The lack of high-quality parallel and annotated corpora limits the development of effective translation systems. Nevertheless, research in this area has advanced in recent years. Specialized corpora have been created for a number of Turkic languages, including Kazakh, Tatar, Uzbek, and Turkish, and neural network models are being actively adapted to their specific features. These steps form the basis for integrating Turkic languages into the global system of multilingual speech technologies. This paper presents an overview of current speech and translation corpora used in speech recognition and synthesis, as well as in speech translation systems.

2.1. Multilingual Speech Corpora

Recent research has focused extensively on developing multilingual and multidialectal speech corpora to support tasks such as speech recognition, S2S translation, and speech synthesis.

Certain methodologies were applied to construct SpeechMatrix, a large-scale multilingual corpus for speech-to-speech translation, using real speech data mined from recordings of the European Parliament. These approaches demonstrated strong performance and scalability [

6]. To assess the quality of the extracted parallel speech data, bilingual S2S translation models were trained exclusively on the mined corpus, establishing baseline performance metrics on the Europarl-ST, VoxPopuli, and FLEURS test sets. A thorough evaluation demonstrated high-quality speech alignments. However, SpeechMatrix does not include Kazakh as a source language and contains no systematically aligned synthetic data for Turkic languages; therefore, it cannot serve as a parallel resource comparable to the corpus proposed in this study.

Building upon this, the Multilingual TEDx corpus [

7] extended the availability of multilingual data beyond English-centric resources, focusing on ASR and ST tasks across eight languages. Baseline experiments explored multilingual modeling strategies to enhance translation for low-resource pairs. Continuing this line, VoxPopuli [

8] offered one of the world’s largest open speech datasets, comprising 400,000 h of unlabeled speech in 23 languages, and included the first large-scale open-access S2S interpretation data. Efforts have also targeted regional and dialectal diversity. For example, SwissDial provides parallel text and audio data across eight Swiss German dialects, with quality assessed via neural speech synthesis experiments covering multiple configurations [

9]. Further methodologies introduced unified multilingual S2S translation frameworks leveraging vocabulary masking and multilingual vocoding to mitigate cross-lingual interference and improve model performance [

10].

In addition to curated resources, community-driven projects such as Common Voice [

11] and CVSS [

12] have expanded the multilingual landscape. Common Voice facilitates scalable multilingual ASR development through crowd-sourced data, while CVSS integrates speech-to-speech translation pairs from 21 languages into English, validated through baseline direct and cascaded S2ST models. Beyond supervised datasets, unsupervised approaches have also emerged. Unlike CVSS, which does not cover Kazakh, Uzbek, or Tatar and does not generate controlled parallel audio across related languages, the present work introduces a synthetic Kazakh-centric parallel corpus specifically designed for Turkic languages. A method for building parallel corpora from dubbed video content combined visual and linguistic cues to align speech across languages, achieving high accuracy and robustness on Turkish–Arabic data [

13]. Similarly, the MuST-C corpus addressed the scarcity of large-scale end-to-end SLT resources by aligning English TED Talk audio with multilingual translations, providing valuable training data for SLT systems [

14]. Finally, wSPIRE contributed parallel data for both neutral and whispered speech, opening new research directions in speech modality analysis [

15].

Together, these resources demonstrate steady progress toward building scalable and diverse multilingual corpora. However, challenges remain in ensuring balance across languages, improving data quality for low-resource settings, and facilitating cross-corpus interoperability—areas that continue to motivate further research.

2.2. Resources for Turkic Languages

While these resources have significantly advanced multilingual speech translation, they remain limited in coverage and applicability for Turkic languages, which continue to face data scarcity and underrepresentation in existing corpora. The following reviews existing research and available resources related to speech and translation technologies for Turkic languages. Certain methodologies were applied to develop KazakhTTS2, an extended version of an earlier open-source Kazakh text-to-speech (TTS) corpus. The updated dataset increases from 93 to 271 h of speech and includes recordings from five speakers (three female, two male) across a wider range of topics, such as literature and Wikipedia articles. The corpus is designed to support high-quality TTS systems for Kazakh, addressing challenges typical of agglutinative Turkic languages. Experimental evaluations report mean opinion scores ranging from 3.6 to 4.2. The dataset, including code and pretrained models, is publicly available on GitHub [

16]. Specific methodologies were also employed to develop a cascade speech translation system for translating spoken Kazakh into Russian. The system is based on the ST-kk-ru dataset, which is derived from the ISSAI Corpus and includes aligned Kazakh speech and Russian translations. It consists of an ASR module for Kazakh transcription and an NMT module for translation into Russian. The study demonstrates that augmenting both components with additional data improves translation performance by approximately two BLEU points. Further comparison between DNN-HMM and End-to-End Transformer-based ASR models was conducted, with results reported using Word Error Rate (WER) and Character Error Rate (CER). These findings highlight the importance of data augmentation for improving speech translation systems in low-resource languages such as Kazakh [

17].

For languages with limited digital resources, such as Tatar, the availability of corpus-based resources has become increasingly critical. In recent years, several open-access Tatar-language text and speech corpora have been developed through both academic initiatives and crowdsourced contributions, aiming to address data scarcity in Turkic-language technologies.

The development and implementation of the national corpus of the Tatar language “Tugan tel”, which represents an important step in the digitalization of the Tatar language, are described in the article [

18]. The corpus includes more than 27-million-word usages from texts of various genres—from fiction to journalism and official documents. The authors consider the principles of morphological annotation adapted to the agglutinative structure of the Tatar language. Building on this foundation, the authors in [

19] proposed a methodology and a toolkit for automatic grammatical disambiguation in a large Tatar-language corpus. The system demonstrates the ability to improve the accuracy of morphological processing significantly. The study makes an important contribution to the corpus infrastructure for the Tatar language and can become a basis for further improvements in the field of morphology and NLP. Complementary resources, such as the Corpus of Written Tatar [

20], expand the infrastructure by offering detailed linguistic, morphological, and frequency data. The system later incorporated a multi-component morphological search engine [

21], enabling flexible searches by lemma, affix, or structural parameters, and supporting advanced corpus analysis. Further research [

22] discussed challenges in building a large-scale corpus exceeding 400 million tokens, outlining technical, annotation, and organizational solutions for sustainable corpus development. The first systematic study of semantic relation extraction from the Tatar corpus “Tugan Tel” was presented [

23]. Algorithmic limitations, morphological difficulties, and the need for lexical semantic infrastructure are highlighted. The study makes a step towards semantically rich tools and resources for Turkic languages.

Progress in Tatar language technologies also extends to speech processing. The authors in [

24] described the construction of an automatic speech recognition (ASR) system for the Tatar language using an iterative self-supervised pre-training approach. The paper demonstrates the potential of self-supervised methods in the context of limited manually annotated resources, which makes it especially valuable for low-resource languages such as Tatar. The TatarTTS dataset [

25] provides an open-source speech synthesis corpus comprising 70 h of professionally recorded Tatar audio, facilitating TTS research and applications. Additionally, in [

26], the authors presented a noise-robust multilingual ASR system adapted for Tatar, based on the Whisper model and trained on over 260 h of speech data from the TatSC_ASR corpus.

Overall, these studies on Tatar language resources demonstrate a gradual transition from corpus compilation and morphological annotation to more advanced semantic and speech technologies, highlighting the growing potential for integrating the Tatar language into multilingual and multimodal artificial intelligence systems.

While some Turkic languages still lack large publicly available datasets of both speech and audio, Uzbek has seen significant progress in recent years. The following is an overview of existing work related to the development of speech and audio resources for Uzbek. Several earlier efforts have explored Uzbek speech recognition, though most were limited in scope and dataset availability. For instance, specific methodologies were applied to build an ASR system focused on recognizing geographical entities, using a small dataset of 3500 utterances [

27]. In a related study, a read speech recognition system was proposed based on 10 h of transcribed Uzbek audio [

28]. A significant step forward was made with the introduction of the Uzbek Speech Corpus (USC)—the first open-source corpus for Uzbek. The dataset comprises 105 h of manually validated speech from 958 speakers. Baseline ASR experiments using both DNN-HMM and end-to-end architectures yielded word error rates of 18.1% and 17.4% on the validation and test sets, respectively. The dataset, along with pretrained models and training recipes, is publicly available to support reproducibility [

29]. A crowdsourced contribution to Uzbek ASR was made through the Common Voice project—a multilingual corpus whose Uzbek subset includes 266 h of speech from over 2000 speakers, representing a valuable resource for building robust ASR systems in low-resource settings [

11]. Additionally, FeruzaSpeech was introduced as a 60 h single-speaker read speech corpus recorded by a native female speaker from Tashkent. The dataset contains literary and news texts in both Cyrillic and Latin scripts and demonstrates improvements in ASR performance when integrated into training pipelines for Uzbek [

30].

In recent years, there has been active development of Turkish speech corpora, contributing significantly to advances in automatic speech recognition and synthesis. Specific analyses were conducted to provide a comprehensive review of studies on Turkish automatic speech recognition systems, covering approaches from classical HMM-GMM models to modern transformer and self-supervised architectures. The main limitations were identified as a lack of resources and computational power, and it was concluded that targeted efforts are needed to achieve quality comparable to human speech perception [

31]. A LAS (Listen-Attend-Spell)-based transformer architecture for Turkish ASR was proposed and trained on multilingual data, achieving high recognition performance on a Turkish subcorpus [

32].

An end-to-end Turkish speech synthesizer based on the Tacotron2 architecture was developed with modifications to account for the morphological features of the language. The model was trained on a local corpus of audio and text, using the WaveGlow vocoder to generate sound. Experiments showed improvements in synthesis quality according to the MOS metric compared to traditional TTS systems, highlighting the potential of the technology for practical applications in voice interfaces and assistive technologies [

33]. Comparative studies of Whisper Small and Wav2Vec2 XLS R 300M models were conducted on the Mozilla Common Voice Turkish v11 dataset, yielding WER scores of approximately 0.16 and 0.28, respectively, with additional testing on real call center data [

34]. Adaptation of the Whisper model to Turkish speech using the LoRA (low-rank adaptation) method demonstrated a significant WER improvement—up to 52% compared to the original model—across five Turkish datasets, confirming the effectiveness of parameter-efficient fine-tuning for low-resource languages [

35]. An ASR system based on the XLSR-Wav2Vec2.0 model retrained on Turkish Mozilla Common Voice recordings achieved an impressive WER of 0.23, demonstrating the high potential of self-trained transformer models on under-labeled data [

36].

Further efforts were dedicated to creating Turkish speech resources. A collaborative initiative by METU and CSLR resulted in a 193-speaker audio corpus and accompanying newspaper text. Automatic phoneme alignment achieved an accuracy of 91.2% within ±20 ms relative to manual tagging, and a phoneme error rate (PER) of 29.3%, demonstrating that the ported SONIC ASR engine was successfully applied to Turkish. The development of a phonetic dictionary and corpus tools provided a foundation for further research and opened new opportunities for improving ASR systems [

37]. The porting of the SONIC recognition OS to Turkish, along with the creation of new corpora, achieved up to 91% phoneme alignment accuracy compared to the standard. Analysis of the phoneme model showed that while some PER remained around 30%, the system was technically suitable for ASR, highlighting the importance of architecture transfer approaches and phonological tool development for low-resource languages [

38]. These results mark an important milestone for Turkish ASR systems and lay the foundation for subsequent corpora and models.

A corpus-based analysis of the oral speech of Arabic–Turkish bilinguals and Turkish monolinguals revealed no major differences in word order, voice structures, or frequency of interjections. However, bilinguals produced a greater number of general sentences, indicating differences in speech structure strategies. This corpus-driven approach made it possible to identify subtle variations in linguistic repertoire and behavior, enriching the understanding of bilingualism and demonstrating the methodological value of corpus data for psycholinguistic analysis [

39]. Finally, a methodology for creating a large Turkish spoken corpus was developed based on audio extracted from subtitled movies, yielding 90 h of synchronized audio and transcription. The integration of preprocessor, parser, and speech extractor modules ensured efficient automation of corpus acquisition and tagging, essential for scalable language resource construction. Speech data from 120 movies showed an average segment length of 45 min, confirming the high density of speech and lexical diversity. The corpus proved suitable for training and testing acoustic ASR models, demonstrating a scalable framework for future research in Turkish speech processing [

40].

2.3. A Comparative Analysis of Available Audio and Text Resources for Kazakh, Tatar, Uzbek, and Turkish

The Kazakh Speech Corpus 2 (KSC2) [

41] is the first industrial-scale, open-source Kazakh speech corpus developed by the Institute of Intelligent Systems and Artificial Intelligence (ISSAI) at Nazarbayev University. This corpus combines data from two corpora—the Kazakh Speech Corpus and KazakhTTS2—and includes additional material collected from a wide range of sources, such as radio, magazines, television programs, and podcasts. It contains approximately 1200 h of high-quality data, comprising over 600,000 utterances. The corpus is freely available and can be used for both academic research and industry. KazakhTTS2 [

42] is a high-quality speech dataset and an updated, expanded version of the KazakhTTS dataset. Compared to the previous version of KazakhTTS, the audio data size has been increased from 90 to 271 h. Three new professional speakers (two female and one male) have also been added, each recording over 25 h of carefully transcribed speech. The inclusion of texts from various sources, including fiction, articles, and Wikipedia, has also enriched thematic content. Like the previous version, KazakhTTS2 is freely available and can be downloaded from the official ISSAI website. Relevant data on these corpora are shown in

Table 1.

The National Corpus of the Kazakh Language is a large-scale collection of electronic texts containing millions of words, fully covering the lexical and grammatical structure of the Kazakh language (with extensive annotations), and a “smart” specialized knowledge base that collects all information about the Kazakh language. The total number of words is 65,000,000. The National Corpus of the Kazakh Language currently consists of 16 subcorpora, each specifically developed for a specific purpose. All internal subcorpora contain morphological, semantic, lexical, and phonetic-phonological annotations [

45,

46].

The TatSC_ASR corpus is one of the largest and most systematic speech datasets for the Tatar language. This corpus includes over 269 h of audio recordings annotated with transcriptions in the Tatar language. The corpus materials were collected from various sources, including crowdsourcing platforms and audiobooks. Hackathon Tatar ASR is a corpus that was assembled during the Tatar.Bu Hackathon in 2024 and is an example of a coordinated crowdsourcing approach to creating speech resources. The corpus size is about 90 h of audio data distributed across almost 69 thousand segments. TatarTTS is a specialized open corpus focused on speech synthesis tasks for the Tatar language. The distinctive feature of this corpus is that the audio recordings are made by professional speakers and are accompanied by high-quality transcriptions, which makes it optimal for Text-to-Speech (TTS) tasks. The corpus contains about 70 h of audio recordings.

Table 2 provides an analysis for each of these corpora.

The Tatar corpus “Tugan tel” is a linguistic resource reflecting the modern literary Tatar language. This corpus is being developed for a wide range of users: linguists, specialists in Tatar and Turkic languages, general linguists, typologists, etc. The corpus includes texts of various genres—fiction, media materials, official documents, educational and scientific texts, etc. Each document is provided with a meta description, including information about the authors, publication data, creation dates, genres, and structural parts of the text. The Corpus of Written Tatar is a collection of electronic texts in the Tatar language created to support scientific research in the field of Tatar vocabulary. Currently, the corpus volume exceeds 500 million words (more than 620 million tokens), and the total number of unique word forms is about 5 million. The corpus is aimed at anyone interested in the structure, current state, and development of the Tatar language. The Tatar–English Corpus is an open parallel corpus containing ~7775 aligned pairs of Tatar and English sentences. However, despite its small size, this corpus is of great importance for various studies in the field of multilingual models and the development of machine translation systems for low-resource languages. A comparative analysis of the corpora is shown in

Table 3.

The Uzbek Speech Corpus (USC), introduced by Musaev et al. [

53], contains over 105 h of transcribed speech data from 958 speakers of different ages and dialects. This corpus is freely available and widely used in ASR research. Another important resource is FeruzaSpeech [

30,

54], a 60 h mono-speaker corpus of read speech with both Latin and Cyrillic transcriptions. It offers high-quality recordings and includes punctuation, casing, and contextual information, making it particularly valuable for robust model training. In addition, Uzbek is included in multilingual open-source datasets such as Mozilla’s Common Voice [

55], although the amount of data remains limited and less curated. These corpora complement each other: USC offers diversity of speakers, FeruzaSpeech provides clarity and consistency, and Common Voice contributes with volume and crowd-sourced variation. In addition to publicly available speech corpora, several large-scale Uzbek speech datasets exist in closed access, including commercial corpora, a 392 h mobile-recorded dataset of 200 speakers [

56]. Information about these corpora is presented in

Table 4 below.

The following section outlines the key initiatives taken to develop and compile text corpora for the Uzbek language. The UzWaC (Uzbek Web Corpus), hosted on the Sketch Engine platform, contains around 18 million words collected from online sources and is used for lexical and frequency analysis [

57]. Another significant project is the Uzbek National Corpus (UNC), which encompasses millions of words drawn from a wide range of sources, including literature, newspapers, and academic works [

58]. Serving as a fundamental linguistic resource, the UNC provides extensive support for morphological and syntactic annotation tasks.

Another important dataset is the TIL Corpus, developed as part of the TIL project, which focuses on parallel Uzbek–English data for machine translation tasks [

59]. The Leipzig Corpora Collection (uzb_community_2017) contains around 9 million tokens and is freely available with automatic linguistic annotation [

60]. The Uzbek Corpus Sample, hosted on GitHub, is a small open-access corpus of approximately 100,000 sentences suitable for basic text analysis tasks [

61]. The Text Classification Dataset includes more than 500,000 news articles and is used for training and evaluating topic classification models [

62]. In addition, Uzbek is included in multilingual datasets such as the OPUS collection, particularly in corpora like OpenSubtitles, GlobalVoices, and Tatoeba, though the size and quality of Uzbek content vary significantly [

63]. These resources serve different purposes: the UNC provides linguistic richness and structural annotation, the TIL Corpus is valuable for translation and alignment, and OPUS-based datasets contribute with multilingual breadth. Furthermore, some large-scale Uzbek textual corpora remain in closed access, including commercial datasets containing millions of sentences from web-crawled content, social media, and online publications. Information on these corpora is summarized in

Table 5 below.

In recent years, there has been significant progress in the creation and publication of Turkish speech corpora, which is especially important for the tasks of automatic speech recognition (ASR), text-to-speech (TTS), linguistic analysis, and language learning. Among the presented resources, the Spoken Turkish Corpus (STC) developed by METU stands out as one of the most valuable academic corpora, including synchronized audio and transcriptions obtained from natural conversations [

64]. The Middle East Technical University Speech Corpus focuses on structured speech and is a balanced corpus useful for building acoustic models and testing microphone speech [

65]. The Mozilla Common Voice Turkish Corpus is a crowdsourced open resource, available without restrictions, and is actively used in educational and applied projects [

11]. Despite its small size (about 22 h), it is regularly updated by the community. The largest by volume is the ASR-BigTurk Conversational Speech Corpus, which contains over 1500 h of spontaneous speech, making it particularly valuable for industrial applications, but its commercial license limits access for research projects [

66]. The PhonBank Turkish Istanbul Corpus offers unique child speech data collected as part of projects studying phonological development and is of great importance for clinical linguistics and speech therapy [

67]. Also noteworthy is the TAR Corpus, developed by the ITU NLP Group, as it is one of the few fully open resources that includes a variety of speech genres: reading, spontaneous dialogues, and interviews. It provides both audio data and verified transcriptions, making it easy to integrate into machine learning [

68].

Thus, there is a growing diversity of Turkish speech corpora in both genres and intended uses—from academic research to commercial use. At the same time, problems remain related to limited access to large and well-annotated corpora, especially for spontaneous and dialectal speech recognition tasks. The development of open and accessible corpora such as the Mozilla Common Voice Turkish and the Turkish Broadcast News Speech & Transcripts corpus (developed by the ITU NLP Group, approximately 130 h of professionally recorded and transcribed news data) ITU NLP Group—Turkish Broadcast News Speech & Transcripts contributes to the democratization of research in the field of Turkish speech processing and supports the multilingual development of artificial intelligence systems. Information about these corpora is presented in

Table 6 below.

The most significant project is the METU Turkish Corpus, which has pioneered the systematic collection of modern Turkish texts in a balanced genre composition. Despite its relatively small size (~2 million words), it contains high-quality markup (XCES and discourse annotation), making it valuable for academic research [

69,

70]. The largest in terms of scope and volume is the TS Corpus, which includes over 1.3 billion tokens. It covers both written and web texts, with automatic morphological and syntactic annotation. It is accessible via a user-friendly web interface, although downloading the raw data is limited [

71,

72]. Another large-scale resource is trTenTen20, a web text corpus of almost 5 billion words, accessible through the commercial Sketch Engine platform and widely used in statistical linguistic research [

73]. The Turkish National Corpus (TNC) is the official national corpus of Turkey. It is an academically verified resource (~50 million words), with a carefully thought-out genre structure and time coverage (2000–2009). However, its access is limited: the full data are not always open, and access to it is carried out through the website interface [

74,

75,

76]. In contrast, trWaC, created using CLARIN technologies, is a lightweight version of the web corpus and is available for free [

77]. A special category is made up of corpora with syntactic and semantic annotations, such as ITU Web Treebank and Boun Treebank, made in the Universal Dependencies (UD) format. These resources are focused on training and testing parsing models and are intended for use in NLP competitions and educational projects [

78,

79].

Political discourse is represented in the ParlaMint-TR corpus, which contains speeches from members of the Turkish parliament from 2011 to 2021. The corpus is annotated with metadata about the speakers (gender, party, position) and provided with morphological markup, which makes it useful for studying political rhetoric and analyzing opinions [

80].

Overall, the diversity of available Turkish-language text corpora enables effective solutions to a wide range of linguistic and engineering problems. At the same time, certain limitations remain, including limited access to the largest resources (TNC, TS Corpus) and underrepresentation of certain genres, such as fiction and social media. Information about these corpora is presented in

Table 7 below.

Despite the diversity of corpora found through OPUS and other sources, the analysis reveals that Turkish still lacks sufficiently large, well-annotated, and balanced open-access resources, especially for speech-related systems.

Multilingual corpora play an important role in the development of modern speech processing and translation technologies. However, their linguistic diversity is limited. Most resources focus on high-resource languages, while morphologically complex and agglutinative languages, including Turkic, are either poorly represented or completely absent. Therefore, existing multilingual models require additional adaptation and data expansion to effectively work with Turkic languages.

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed methodology for constructing a parallel audio corpus for Turkic languages is implemented as a sequential workflow comprising several stages. In the first step, a validated Kazakh audio-text corpus is selected as the initial dataset. Transcriptions are then extracted from the corpus and automatically translated into the target Turkic languages (Turkish, Uzbek, and Tatar) using the NLLB-200 model. The resulting translations are synthesized into audio files using modern speech synthesis systems (MMS-TTS, TurkicTTS, ElevenLabs, and CoquiTTS). Then, each initial unit is mapped to four interconnected components: Kazakh audio, Kazakh transcription, translated text, and synthesized audio in the target(Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek) language. The final stage involves corpus evaluation and validation using automated metrics (BLEU, chrF) to assess translation quality, along with manual verification of naturalness and pronunciation consistency. This overview provides a conceptual description of the methodological pipeline and serves as a guide for the detailed discussion in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5 3.1. Cascade Audio Corpus Generation

The collection of similar speech corpora for low-resource languages using the cascade technology (STT—TTT—TTS) has several serious drawbacks, especially when working with Turkic and other low-resource languages.

The cascade scheme, with its sequential data processing from transcription to translation and speech synthesis, is highly scalable. It utilizes available resources at every stage, such as audio corpora, LLM translators, and TTS models, allowing for seamless adaptation to new languages or domains. Its scalability highlights the framework’s flexibility, requiring modifications only to specific modules when expanding or adjusting its scope. This scheme, with its use of a ready-made corpus (audio and transcription) and automated tools (an LLM for translation and a TTS for synthesis), offers a significant reduction in labor and financial costs. This cost-effectiveness is a key advantage, especially when compared to the full cycle of recording and manual data processing.

In this study, we introduced a highly efficient cascade technology for forming a parallel audio corpus. This innovative approach is based on the reuse of an existing resource—a structured Kazakh-language audio corpus with verified transcriptions. By eliminating the need for speakers and studio recordings, as well as manual audio segmentation, which is typical for processing unstructured Internet sources, we have significantly streamlined the process.

At the first stage, text transcriptions of the Kazakh corpus are automatically translated into target languages (Turkish, Uzbek, Tatar) using a large language model (NLLB-200 1.3B). The translated texts are subsequently processed by text-to-speech (TTS) systems, which produce corresponding audio files in the target languages. This process results in a fully developed parallel dataset that includes both audio and text components in the source language (Kazakh) and the respective target languages.

To quantify the accuracy of machine translation produced by the NLLB-200 (1.3B) model, the system was evaluated using two widely adopted automatic metrics: BLEU and chrF. In the absence of standardized benchmark datasets for the Kazakh → Turkish, Kazakh → Uzbek, and Kazakh → Tatar translation directions, a manually curated test set comprising 1000 parallel sentences for each target language was constructed. The evaluation results are provided in

Table 8.

The developed approach significantly reduces the amount of work and financial costs required to form audio corpora in several languages. The advantages of the proposed approach include:

no need for manual recording and segmentation of audio;

complete automation of translation and voice-over stages;

the ability to scale to multiple target languages with minimal resources;

focus on supporting low-resource Turkic languages, for which the number of open parallel corpora is minimal.

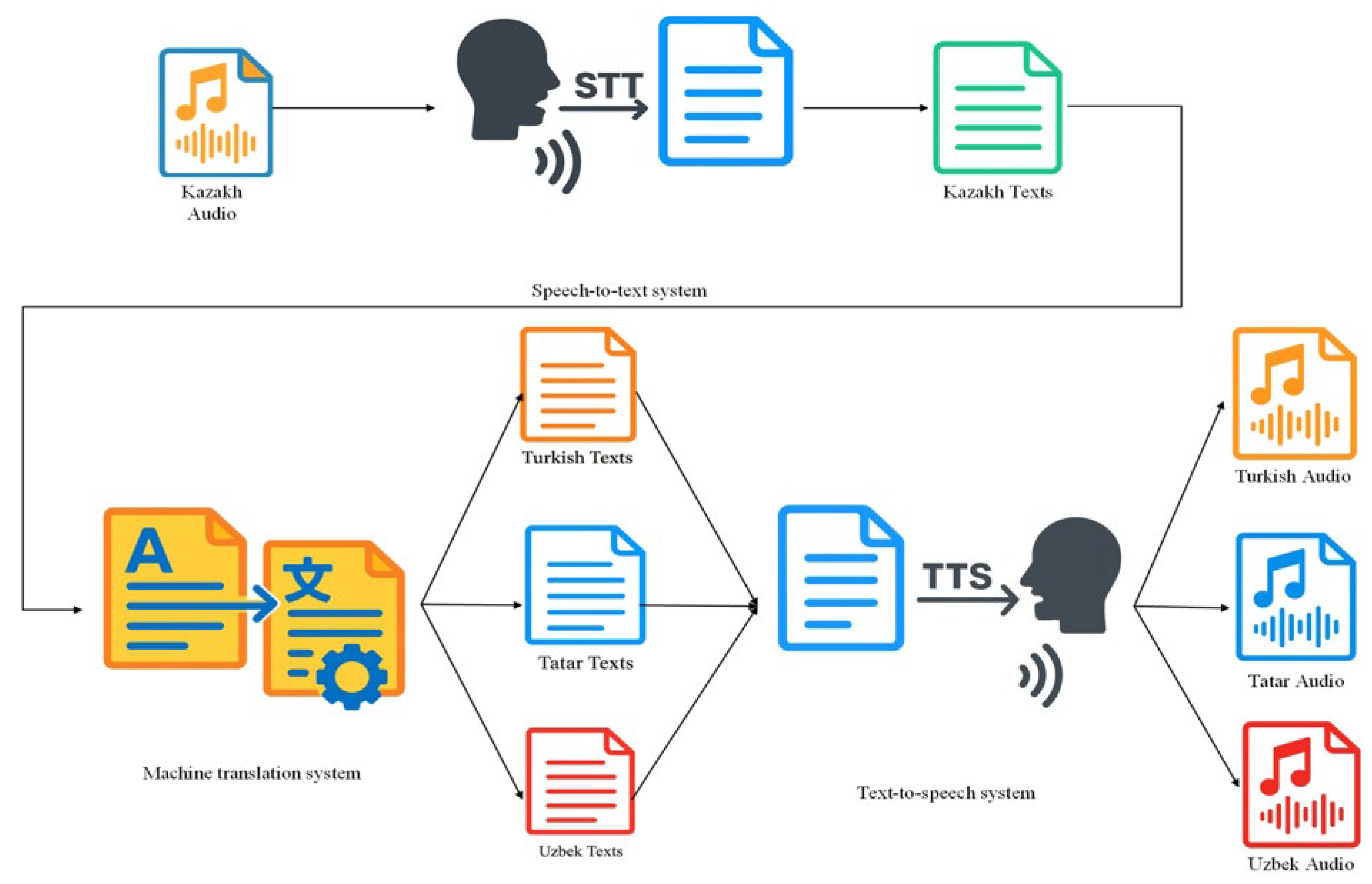

The architecture of the cascade technology for forming a parallel audio corpus is implemented as a sequence of steps. This process aims to transform audio data in the Kazakh language into multilingual text–audio pairs (Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek). The process includes the following steps (

Figure 1):

Initial audio corpus (L1):

As a starting point, a ready-made audio corpus in the Kazakh language (L1) is used, including synchronized pairs of “audio + transcribed text”. The source of the corpus is Nazarbayev University (17 K and 12 K sentences.

Text transformation (L1 → L2):

The transcribed Kazakh text is passed to the input of a large language model (LLM), which performs automatic machine translation into the target language (L2), for example, Turkish, Uzbek, or Tatar.

Text-to-speech (TTS, L2 → audio):

The resulting translation is used as input for a neural network text-to-speech (TTS) model, which generates an audio file corresponding to the translated text in L2.

Parallel data generation:

As a result of cascade processing, a complete dataset is created for each source sentence:

audio file in Kazakh (L1),

transcription in Kazakh (L1),

translation into the target language (L2),

generated an audio file in the target language (L2).

This resulted in four interconnected output components: (1) audio and (2) text in the source Kazakh language, and (3) audio and (4) text in the target language. This structure provides parallel correspondence at both text and audio data levels, making the corpus suitable for training and evaluating models in speech machine translation and multilingual TTS/STT.

Despite the high quality of output data achieved using cascade speech translation technology, this approach places high demands on resources at the stage of preparing training corpora. Building a reliable corpus involves several meticulous steps: organizing studio recordings with native speakers, manually segmenting audio files, performing transcription, conducting linguistic proofreading, and verifying the final transcriptions. These processes are highly labor-intensive and costly, particularly for low-resource languages like Kazakh, where access to extensive audio data and qualified experts remains limited. The impact of these challenges is profound, as they directly influence the progress and availability of speech translation technologies. Given these limitations, this paper also considered an alternative, less labor- and time-consuming method for preparing a parallel audio corpus. In

Section 3.2, we introduce the use of crowdsourced data and automated tools for corpus preparation, which can significantly reduce the resources and time required to create corpora.

3.2. Text-First Cascade Audio Corpus Generation for Turkic Languages

Classical approaches using automatic speech recognition (ASR) for languages with limited resources, in particular Turkic languages (Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar), are associated with significant difficulties. A significant number of recognition errors, a shortage of large speech databases, pronunciation variability, and richness of vocabulary hinder the effective use of STT technologies for the formation of high-quality parallel audio corpora. These limitations indicate the need for alternative methodologies.

The TTT approach is a reliable tool that offers a more accurate solution, guaranteeing high quality and reliability of the obtained data. In this methodology, parallel text pairs are first created manually or semi-automatically. Then, each side is processed using text-to-text (TTT) systems. This approach enables complete control over all critical parameters of the parallel corpus, from the semantic accuracy of translation to consistent sentence alignment and stylistic equivalence of texts. This meticulous control ensures the preservation of the grammatical and morphological integrity characteristic of agglutinative languages such as Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar, and others.

First, controlling the process at the text level allows for eliminating distortions that often occur during automatic speech transcription. Moreover, the use of modern speech synthesis systems trained on high-quality and verified data ensures the generation of sound that is virtually indistinguishable from natural speech while accurately conveying the content of the source text. This emphasis on the naturalness of sound creates a sense of authenticity and closeness to the original.

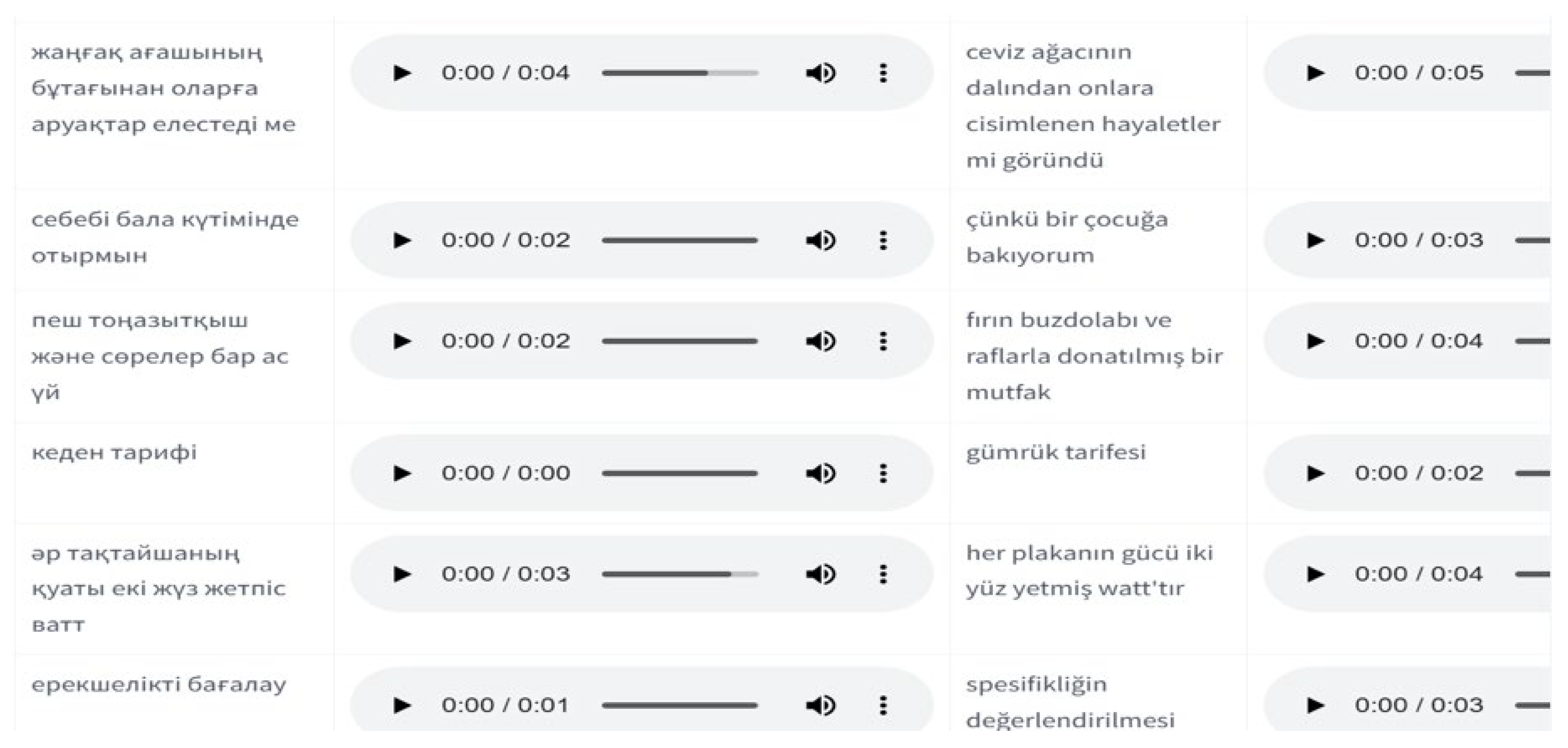

We present an approach to forming audio corpora for Turkic languages, utilizing speech synthesis technology to eliminate the traditional stage of recording audio data with speaker participation. The source material is Kazakh texts, which are fed to the input of a neural machine translation system, particularly the NLLB (No Language Left Behind) model. This system provides automatic translation from Kazakh into closely related Turkic languages: Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek. The translated texts are then processed using speech synthesis systems (TTS—Text-to-Speech), resulting in the formation of audio files corresponding to the translated texts. Thus, based on the synthesis, a parallel audio corpus is formed for the specified languages. Additionally, the original Kazakh texts are also synthesized using the same TTS system, allowing for the generation of synthetic audio data in the source language.

This approach is designed to automate the process of creating audio corpora, offering high scalability and reducing the dependence on resources required in the traditional approach involving speakers. This automation is a key feature of the methodology. An illustrative diagram of the proposed methodology is presented in

Figure 2.

Thus, the TTT → TTS approach, which consists of the formation of parallel text pairs (TTT) with their subsequent pronunciation by speech synthesis systems (TTS), ensures not only high accuracy of parallel corpora but also the necessary flexibility for working with languages with limited resources, where automatic methods have not yet demonstrated sufficient reliability. This approach, with its inherent flexibility, becomes especially valuable for creating training datasets needed for the development of multilingual models for translation, speech generation and analysis, as well as the digital preservation and development of minority languages.

Using the Text-to-Text (TTT) method instead of Speech-to-Text (STT) when creating parallel audio data appears more justified from both theoretical and practical perspectives. This is especially relevant in the context of machine translation of speech, building multilingual systems, and forming synthetic parallel speech corpora for Turkic languages.

Firstly, the TTT method achieves high accuracy through the manual or semi-automatic creation of parallel texts. This approach is particularly effective for Turkic languages, which are characterized by rich morphological agglutination, the process of forming words by combining multiple morphemes, along with flexible word order and diverse grammatical sentence structures.

The use of TTT is a relief for low-resource Turkic languages, such as Uzbek, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and even Kazakh, despite the limited available resources. In these cases, STT often produces high recognition errors due to insufficient model training, limited speech data, substantial dialectal variation, accents, noise, and phonetic distortions. TTT, on the other hand, significantly reduces these risks, providing a more secure and reliable basis for work.

In addition, the use of TTT enables the standardization of input texts, automatic normalization, morphological analysis, and filtering, which is critical when building training corpora for machine translation systems and multilingual speech synthesis. This is especially relevant in research on creating multimodal models and in projects like KazParC, TurkicASR, and KazakhTTS, where parallel text-audio data are generated for dozens of languages, including Turkic.

The proposed approach to creating audio corpora, based on automatic translation and speech synthesis, is of particular value for low-resource languages. It allows for a significant reduction in time and resource costs by eliminating the need for studio recording with speakers and special equipment. The complete automation of the process ensures high reproducibility and scalability, making it possible to quickly generate large volumes of audio data in several Turkic languages. This method opens up the possibility of creating speech resources even for those languages where traditional methods of collecting audio corpora are difficult or impossible. Its potential impact on the digital representation of low-resource languages in modern information systems is significant, contributing to their increased visibility and accessibility.

3.3. TTS Systems for Turkic Languages

Despite the advances in speech synthesis, not all modern TTS systems currently support Turkic languages, and many of them require additional adaptation and training efforts. Below are the TTS systems, which are described by the degree of openness, language support, and voice quality.

MMS-TTS, developed by Meta AI, is a truly advanced open-source speech synthesis system [

81]. It supports more than 1100 languages, including resource-poor Turkic languages such as Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Tatar. The system, presented in May 2023 on GitHub, has quickly become one of the most ambitious projects in the field of multilingual speech synthesis, catering to a wide range of linguistic diversity.

MMS-TTS uses a unified multilingual architecture based on Transformer and HiFi-GAN technologies, which allows it to effectively work with typologically diverse languages, including agglutinative Turkic languages. The system’s adaptability is a testament to its robustness, using cross-lingual phoneme representations and joint acoustic modeling, making it especially effective for low-resource languages.

It stands out for its high naturalness of synthesized speech in the Kazakh language, with correct intonation and accent design. This impressive capability is made possible by the use of open corpora KazakhTTS and KazakhTTS2, which significantly facilitate additional training and adaptation of models.

MMS-TTS is not just a theoretical concept, but a practical tool actively used in scientific initiatives and open-source projects such as TTS4All and TurkicTTS. This active use reassures the audience about its reliability and relevance in the academic environment.

Despite its strengths, MMS-TTS is not without limitations. One notable issue is the limited variety of voices, with most models lacking female speakers. The system also struggles with supporting dialects and tonal variations, particularly in the Tatar language. Furthermore, the lack of support for the Latin alphabet in the Uzbek language, the official script in Uzbekistan, poses a significant challenge. MMS either fails to voice such texts or makes segmentation errors. The scarcity of large open corpora in the Uzbek Latin alphabet further complicates the training and objective assessment of model quality. In some instances, models designed for English prosody yield inconsistent results when synthesizing Turkish speech, particularly in terms of stress and intonation.

Despite these technical and resource limitations, MMS-TTS remains a significant solution for speech synthesis in Turkic languages within the open software context. Its unique focus on Turkic languages, high naturalness of synthesized speech, and potential for further development make it a valuable tool for researchers, developers, and students interested in speech synthesis and open-source AI projects.

TurkicTTS is a significant leap in the development of speech synthesis technologies for Turkic languages, underlining our unwavering commitment to linguistic inclusivity and digital accessibility [

82]. Designed explicitly for Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tatar, and other Turkic languages, it considers their phonetic and morphological features, as well as the lack of language resources in public corpora. This commitment ensures that no Turkic language is left behind and that all can benefit from the advancements in speech synthesis technology.

Like Meta AI’s MMS-TTS, TurkicTTS leverages modern deep learning architectures such as Transformer and HiFi-GAN, but with a unique focus on the Turkic language family. These architectures enable a more accurate adaptation of models to the agglutinative structure of languages, complex stress patterns, and pronunciation variability. The system’s extensive use of cross-linguistic phoneme representations ensures robust generation even for dialectal forms and rare sound combinations. One of the key strengths of TurkicTTS is its high expressiveness and naturalness of synthesized speech, even when working with limited data. This, coupled with its high technical maturity, instills confidence in TurkicTTS as a reliable and advanced tool for Turkic language speech synthesis.

The most developed model in the system is the Kazakh model in TurkicTTS, based on the KazakhTTS2 corpus (about 270 h of speech from five speakers, including male and female voices), which ensures high-quality synthesis and stable work with long and complex phrases. However, spoken forms in Kazakh often sound mechanical, with limited intonation and stylistic variability. The model does not support emotional colors, ‘regional accents’ (variations in pronunciation specific to a region), and voice diversity, which makes the intonation monotonous and predictable, with a lack of natural pauses and rhythmic dynamics. Turkish is characterized by a more natural intonation, especially in neutral speech. Uzbek is supported in the Latin script, and at the standard speed, synthesized sentences sound rhythmic and precise. Despite the overall quality of Uzbek synthesis being currently inferior to Kazakh and Turkish, with less natural sound, a limited number of speakers, pronounced synthetic artifacts, and weak intonation modulation, the system’s ability to independently train on user corpora is a reassuring feature. This adaptability offers the potential to enhance quality and adapt to specific tasks, providing reassurance about the Uzbek model’s potential.

ElevenLabs TTS, a cutting-edge commercial speech synthesis system, provides robust support for Turkic languages and is capable of producing highly natural speech with accurate intonation and pauses [

83]. Since 2024, ElevenLabs has gradually introduced support for Turkic languages into its multilingual TTS platform. Leveraging extensive multilingual corpora and advanced deep learning architectures, the system consistently generates high-quality speech in Kazakh, Turkish, Uzbek, and Tatar, ensuring reliable and fluent performance. A key advantage of ElevenLabs is its wide range of available voices, offering variations in timbre and tone that enable users to customize output to their preferences. Its handling of Turkish speech is particularly impressive, maintaining proper rhythm and flow even in lengthy sentences. Unlike many free systems, ElevenLabs fully supports the Latin alphabet—an essential feature for modern Uzbek. However, certain limitations persist. The system may mispronounce foreign names and terms, and difficulties arise when processing specific Uzbek letters (such as o’, g’, sh, and ch), which can affect pronunciation accuracy. Additionally, it sometimes struggles to capture the natural stress and intonation patterns of Uzbek, especially in formal contexts.

ElevenLabs TTS, a state-of-the-art commercial speech synthesis system, offers support for Turkic languages and the creation of very natural speech with the correct intonation and pauses [

83]. Since 2024, ElevenLabs has been rolling out support for Turkic languages within its multilingual speech synthesis system. By utilizing large multilingual corpora and advanced deep learning architectures, the system consistently delivers high-quality speech synthesis in Kazakh, Turkish, Uzbek, and Tatar languages, ensuring a reliable performance. What sets it apart is the variety it offers—users can choose from a range of voices with different timbres and tones, allowing for a high level of customization. The system’s performance with the Turkish language, maintaining the correct rhythm even in long sentences, is exceptional. Unlike free systems, ElevenLabs fully supports the Latin alphabet, a key feature for the modern Uzbek language. However, the system does have its limitations. Foreign names and terms may be mispronounced, and working with the Uzbek language can present challenges with special letters (o’, g’, sh, ch) that can distort pronunciation. The system also struggles to convey Uzbek stress and intonation, particularly in formal speech.

Unlike academic or open solutions, such as MMS-TTS from Meta AI or the specialized TurkicTTS system, the ElevenLabs platform operates on a subscription model, which comes with certain usage restrictions. Even the basic tariffs have strict limits on the number of characters per month, which can pose challenges with intensive use, for instance, when voicing long texts or multiple generations. It is important to be aware of these limitations when considering the system for your needs.

The system does not provide open-source code, does not allow local installation, and excludes the possibility of additional training for specific tasks or accents. In addition, the stability and quality of synthesis in Uzbek and Tatar languages may be inferior to the support of Kazakh and Turkish, which is probably due to the different completeness of the language corpora used in training. Thus, ElevenLabs TTS is associated with financial costs, especially for large-scale tasks, where a paid subscription with a limited character volume may not be economically feasible in the long-term.

CoquiTTS is a modern open speech synthesis system created by the Coqui.ai team based on the Mozilla TTS project [

84]. The system was officially launched in December 2021 by former Mozilla employees, who developed a completely open platform for speech generation. The main difference of CoquiTTS is the ability to work with various languages, including Turkic languages (Kazakh, Turkish, Tatar). The system has a modular structure, which empowers users to create individual voice models even with limited data. This adaptability opens opportunities for high-quality speech synthesis in Turkic languages, which previously did not have sufficient support in the field of voice technologies. The technological base includes modern components (Tacotron 2, Glow-TTS, HiFi-GAN), providing precise intonation control and natural sound. The platform supports working with several languages simultaneously and allows for customization of the voice characteristics, which further empowers users to tailor the system to their specific needs. The highest quality of synthesis is achieved for the Kazakh language, in particular, when using the KazakhTTS2 corpus, as well as for the Turkish language, where the VITS architecture implemented within CoquiTTS shows itself well. Speech in these languages is distinguished by clarity, intonation, expressiveness, and natural melody. The Uzbek language in ElevenLabs also demonstrates moderately high quality, but in terms of intonation, elaboration, and fluency, it is inferior to Kazakh and Turkish.

However, there are no official models for the Uzbek and Tatar languages in CoquiTTS, and their development requires independent training on the corresponding corpora. This complicates the initial setup of the system for low-resource languages. In addition, errors related to incorrect intonation may occur during the generation process, especially in long phrases. It is crucial to note that semantic accents can be lost, which is especially critical for the Uzbek and Tatar languages, where intonation contours play a significant role in conveying meaning.

Modern speech synthesis systems (MMS-TTS, ElevenLabs, CoquiTTS, TurkicTTS) have made significant strides in supporting Turkic languages. Each system has its advantages: TurkicTTS, for instance, has demonstrated remarkable progress in this area, particularly with Kazakh, Turkish, Uzbek, and Tatar. MMS is a versatile, free system that works with many languages. ElevenLabs is a commercial system that creates high-quality and emotional speech. CoquiTTS, on the other hand, allows for training models. While Kazakh and Turkish are currently the best-supported Turkic languages, there are still significant challenges with Uzbek and Tatar.

Thus, the systems considered are reliable and flexible tools for generating speech in Turkic languages. However, for the effective use of these systems, careful data preparation is necessary, which is especially critical when working with low-resource languages.

3.4. Datasets

This study employed two types of corpora: (1) an audio corpus transcription consisting of 1000 recordings for implementing the cascade speech synthesis approach, and (2) a text corpus comprising 4000 sentences for the Text-First method. In total, 5000 sentences were used in the experimental part.

For the cascade approach, the audio data were meticulously selected from the Nazarbayev University (NU) corpus. The NU contains 29,000 professional audio recordings with accurate transcriptions in the Kazakh language and was selected because of a detailed comparison of existing public and partially accessible databases. The Nazarbayev University (NU) corpus was selected as the primary source of real speech data in case of reliable acoustic quality. This choice was the result of a detailed analysis of various corpora by key parameters: quality of audio recordings, correctness of transcriptions, and accuracy of segmentation. The NU corpus, containing professional studio recordings of Kazakh speech, fully met the established requirements and turned out to be optimal for our research tasks. Due to the significant costs of generating synthetic speech by commercial TTS systems, a representative sample of 1000 sentences was formed for experiments, representing the diversity of vocabulary and grammatical structures of the language.

For testing the Text-First Cascade Audio Corpus Generation methodology, a test set containing 4000 sentences was used. This dataset was used to generate speech with four different TTS systems, providing the possibility of complex intersystem analysis using both quantitative and qualitative evaluation criteria. This test dataset included sentences in four Turkic languages: Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkish, and Tatar, with 4000 sentences per language, resulting in a total of 16,000 unique test instances. All sentences in the test set were disjointed from the training data to ensure experimental validity.

The experimental part included the dataset consisting of 1000 high-quality audio recordings, along with their verified transcriptions in Kazakh. These samples served as the reference dataset for the Cascade Audio Corpus Generation methodology. In addition, we prepared 4000 text sentences covering diverse thematic domains (e.g., everyday communication, news, technical discourse, literature) to ensure variability and representativeness in the generated audio for the Text-First Cascade Audio Corpus Generation for Turkic languages.

The combination of these datasets of 5000 sentences was added for the experiments with 4 TTS systems: MMS, TurkicTTS, Elevenlabs, and CoquiTTS.

The audio files generated by all four TTS systems, across a total of 5000 sentences, presented the following statistics. The whole duration in seconds was 508,129 s./8468.81 min/141.14 h. and was distributed among the TTS systems, as shown in

Table 9.

Each TTS model is presented by several voice variations, including 1 female voice for the Kazakh, Tatar, and Uzbek languages and 1 male voice for the Turkish language of the CoquiTTS model; 1 female voice for the Kazakh, Tatar, and Uzbek languages and 1 male voice for the Turkish language of the Elevenlabs; 2 males voices for the Kazakh, Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek languages of the MMS model; 4 males voices for the Kazakh, Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek languages of the TurkicTTS model.

In addition, a monolingual text corpus in Kazakh was compiled, consisting of 100,000 sentences covering topics such as medicine, politics, and social affairs. The Kazakh texts were sourced from formal media and institutional publications and were intended to both enrich the linguistic base and serve as input for TTS synthesis.

An additional subcorpus of 5000 news headlines was extracted from the Kazakh-language news portal 24.kz. Headlines were selected for their linguistic purity and formal style.

These corpora provide broad linguistic coverage of contemporary Kazakh and serve as a robust empirical foundation for research in speech synthesis, TTS evaluation, and cross-lingual modeling.

3.5. Metrics

To evaluate TTS (text-to-speech) systems without original audio (reference-free), the following metrics were used: and .

The

(Mean Opinion Score Network) metric’s function is to estimate the perceived naturalness of synthetic speech, mimicking human judgment typically captured via Mean Opinion Scores (

) [

85]. This metric is especially valuable in text-to-speech (TTS) and voice conversion systems, where producing human-like audio is a key objective.

is a deeply objective deep neural network model. It has been trained on large-scale human-annotated datasets to learn the mapping between audio and corresponding

values. This objective ensures its unbiased evaluation. After training, it functions as a non-intrusive quality estimator that takes an audio signal as input, extracts relevant spectral features, and outputs a predicted

score that reflects the naturalness and intelligibility of the speech (1).

where

—neural network regressor,

—mel spectrum audio,

—predicted

.

(Deep Noise Suppression Mean Opinion Score) is a neural network-based metric developed by Microsoft researchers within the framework of the Deep Noise Suppression (DNS) Challenge [

86]. It aims to automatically estimate the

, a standard subjective measure of speech quality rated by human listeners on a scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). Unlike traditional methods,

is non-intrusive, meaning that it does not rely on a clean reference signal. Instead, it operates directly on noisy or synthesized audio inputs to generate an estimated

score.

The model utilizes a neural function (2):

where

represents the input audio signal,

denote spectral representations (e.g., mel-spectrograms or log-power spectra), and

is a neural network parameterized by

, which outputs the predicted

score

.

Training is performed by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between predicted and actual

values, as defined by Equation (3):

The (Non-Intrusive Speech Quality Assessment) metric is used to assess the naturalness and intelligibility of synthesized audio speech where there is no reference (clean) signal for TTS systems. Its main task is to predict the quality of speech from the standpoint of human perception in situations with noise and distortions that occur during speech synthesis. is based on a neural network model trained on large datasets with quality assessments collected from real users. The model receives an audio file, extracts spectral and statistical features (for example, log-mel spectrograms), and produces predicted scores reflecting the overall quality, noise level, and the presence of gaps. The score gives a reliable idea of the perceived quality: the closer to 5, the more natural and pleasant the sound is considered.

The most modern approach to date is considered to be

(Self-Supervised Learning MOS).

is a state-of-the-art neural network model designed to automatically assess the quality of synthesized speech without requiring human intervention or a reference audio. It utilizes pre-trained self-supervised speech models (e.g., HuBERT, Wav2Vec 2.0, Data2Vec) to extract profound and universal acoustic features, making it more robust, portable, and accurate compared to classic

models (e.g.,

). The high correlation of

with real

assessments instills confidence in its accuracy, making it a reliable tool for speech quality assessment [

87].

Scores predicted by metrics such as and are interpreted as follows:

5.0 ‘Excellent’—speech sounds completely natural;

4.0–4.9 ‘Good’—speech is almost indistinguishable from real;

3.0–3.9 ‘Acceptable’—unnatural elements are heard, but speech is understandable;

2.0–2.9 ‘Poor’—speech is distorted, and the synthetics are noticeable;

1.0–1.9 ‘Very poor’—speech is difficult to understand or incomprehensible.

The obtained values of the synthesized speech quality metrics () are presented in the Results section for each of the languages considered.

3.6. Ethics/Data-Use Statement

In this study, we used a mixed-type audio corpus: (a) a subset of real speech recordings from the licensed Nazarbayev University (NU) corpus; and (b) synthetic speech generated via TTS systems (MMS, TurkicTTS, ElevenLabs, Coqui TTS). The real-speech portion was used under the existing licensing terms of the NU corpus; we did not record any new human voice data for the purposes of this study.

As recommended by Yang et al. [

88], we documented the provenance and nature of all audio data, distinguishing real-speech and synthetic-speech components to ensure transparency in data use and compliance with privacy and ethical standards.

For the synthetic-speech portion, all audio samples were generated from text-only inputs; therefore, they do not represent personally identifiable voice or biometric data tied to any living individuals.

Study participants—native-speaker listeners—were involved solely to perform listening tests (listening to and rating audio samples). Prior to participation, all listener-evaluators provided informed voluntary consent. Their responses and any associated metadata are stored anonymously and will not be publicly disclosed.

Access to raw generated audio files is restricted. While synthetic speech samples were used internally for evaluation and analysis, raw synthetic audio will not be publicly released without explicit control and approval. Any audio shared will be stripped of metadata that could enable speaker identity tracing or misuse, ensuring robust anonymization and minimizing privacy risks.

We commit to providing audio data only under conditions that prevent misuse, require explicit acknowledgment of synthetic origin, and prohibit impersonation or unethical use.

Because our study combines licensed real-speech data and newly generated synthetic audio, without recording new voice talents, the requirement for obtaining additional consent from speakers/voice talents does not apply.

4. Results

Audios in Kazakh, Turkish, Tatar, and Uzbek were generated using four TTS systems: MMS, TurkicTTS, ElevenLabs, and Coqui TTS. Each model was deployed with its own parameters and computational environment.

MMS-TTS (

https://huggingface.co/facebook/mms-tts, accessed on 1 August 2025) integrates a text encoder, stochastic duration predictor, flow-based decoder, and vocoder. Input text is processed end-to-end, producing speech directly from linguistic embeddings.

TurkicTTS (

https://github.com/IS2AI/TurkicTTS, accessed on 1 August 2025) is a multilingual end-to-end model based on Tacotron 2, with IPA-based transliteration and a Parallel WaveGAN vocoder. Fine-tuning uses configurable hyperparameters (e.g., attention threshold, length ratios, speed control α = 1.0).

Coqui TTS (

https://github.com/coqui-ai/TTS, accessed on 1 August 2025) employs XTTS-v2, an end-to-end multilingual voice cloning model. It takes text, a reference speaker’s audio, and a language code as inputs, running on a CUDA-enabled PyTorch GPU (Berlin, Germany) for GPU-accelerated inference.

ElevenLabs TTS (

https://elevenlabs.io/app/speech-synthesis/text-to-speech, accessed on 1 August 2025) operates via a Python API client (v2.11.0). Speech generation is handled entirely on ElevenLabs’ cloud infrastructure, with text, voice_id, and model_id as inputs. Hyperparameter tuning is not available to users.

Hardware setup is following:

MMS and TurkicTTS required a high-performance station (Intel Core i7 CPU, RTX 4090 GPU, 1 TB SSD).

Coqui TTS and ElevenLabs were run on a lighter setup (Intel Core i7 CPU, RTX 2070 GPU, 1 TB SSD) as they do not demand extensive local resources.

The results of evaluating the quality of synthesized speech for Kazakh–Turkish, Kazakh–Uzbek, and Kazakh–Tatar using MOSNet, DNSMOS, NISQA, and SSL-MOS metrics are shown in

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11. They also evaluate the audio intonation, expressiveness, and linguistic adequacy. Intonation refers to the pitch patterns and melodic contours of speech that signal emphasis, emotion, and sentence structure. Expressiveness describes the degree to which speech conveys emotion, style, and natural variation beyond the literal words. Linguistic adequacy is the extent to which the spoken output correctly reflects the intended text in terms of grammar, pronunciation, and semantic meaning.

Although these metrics are designed to evaluate the naturalness and perceptual audio quality, their scores have the potential to reflect aspects of intonation, expressiveness, and linguistic adequacy in generated speech.

Intonation presents the pitch patterns and melodic contour of speech that signal emphasis, emotion, and sentence structure. Expressiveness describes the degree to which speech conveys emotion, style, and natural variation beyond the literal words. Linguistic adequacy is the extent to which the spoken output correctly reflects the intended text in terms of grammar, pronunciation, and semantic meaning. Higher scores on these metrics generally correspond to more natural acoustic patterns and fewer distortions, which often co-occur with well-formed prosody and clearer articulation. SSL-MOS, due to its reliance on self-supervised speech representations, can be sensitive to unnatural pauses or inconsistent phoneme transitions, which are features that relate to intonation and linguistic clarity. Similarly, NISQA’s multi-dimensional modeling of speech quality captures subtle variations in timbre and continuity that influence expressiveness and linguistic adequacy.

The Results section presents the developed parallel audio corpora for Kazakh–Turkish, Kazakh–Uzbek, and Kazakh–Tatar (

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12 and

Table 13), and the results of the evaluation of the quality of synthesized speech using formal metrics aimed at measuring its naturalness, intonation, expressiveness, and auditory perception.