EMS-UKAN: An Efficient KAN-Based Segmentation Network for Water Leakage Detection of Subway Tunnel Linings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Efficient backbone with depthwise separable convolutions and edge enhancement: Reduces computational cost and parameter count while preserving accuracy, with EEDM enhancing boundary feature representation in the decoder.

- Incorporation of PKAN block: Captures complex nonlinear relationships and long-range dependencies, improving representation of subtle and irregular leakage patterns.

- AMS Block in skip connections: Captures both fine-grained local details and large-scale leakage regions, enhancing robustness under varying conditions.

- Validation on the TWL dataset: Extensive experiments demonstrate superior segmentation with an accuracy of 86.52%, an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 82.19%, and a Dice coefficient of 85.46% while reducing computational complexity—highlighting the model’s practical potential for real-world tunnel inspection scenarios.

2. Related Works

2.1. Feature Extraction Architectures

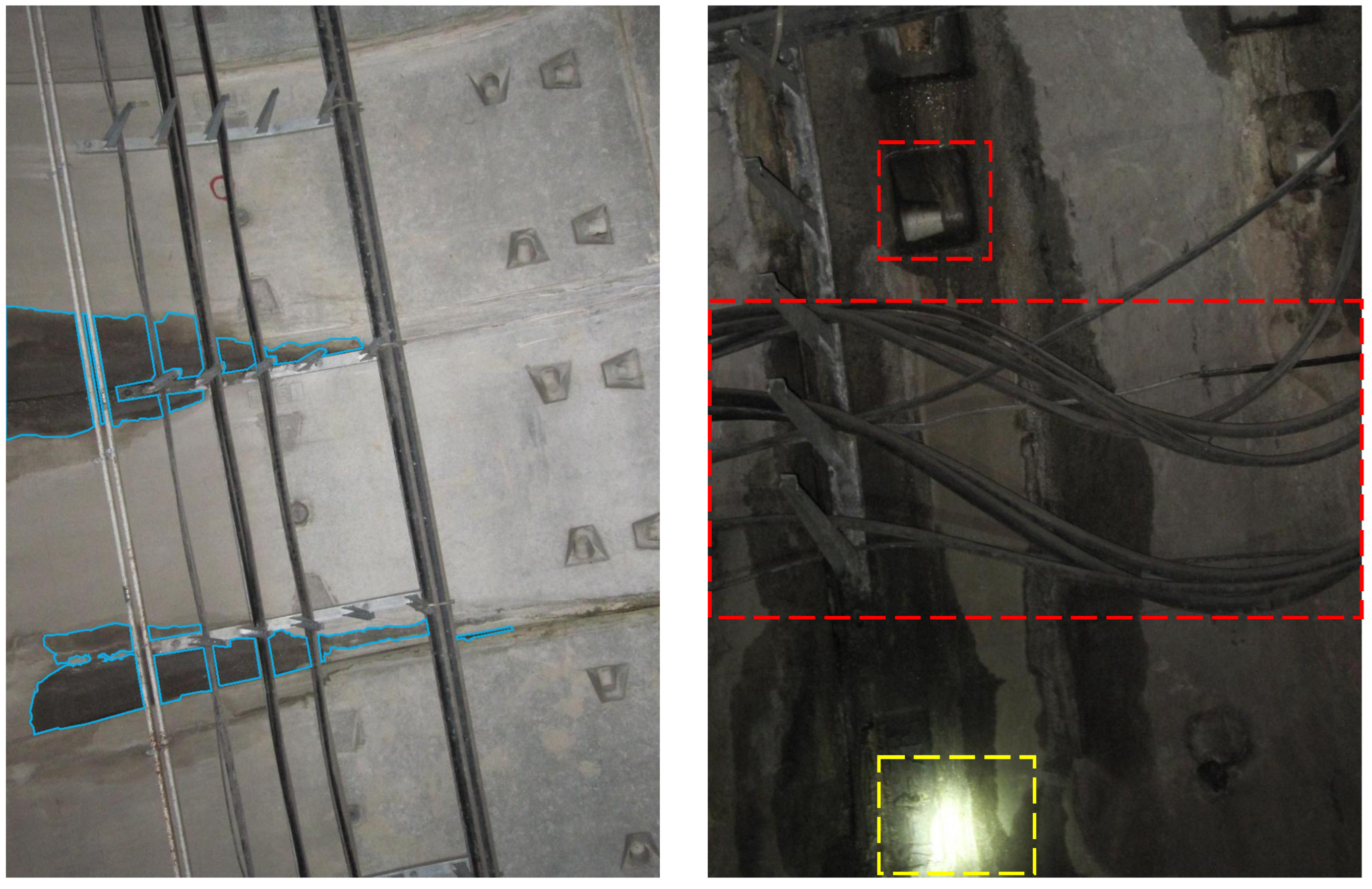

2.2. Segmentation Models Applied to Tunnel Water Leakage Detection

3. Methods

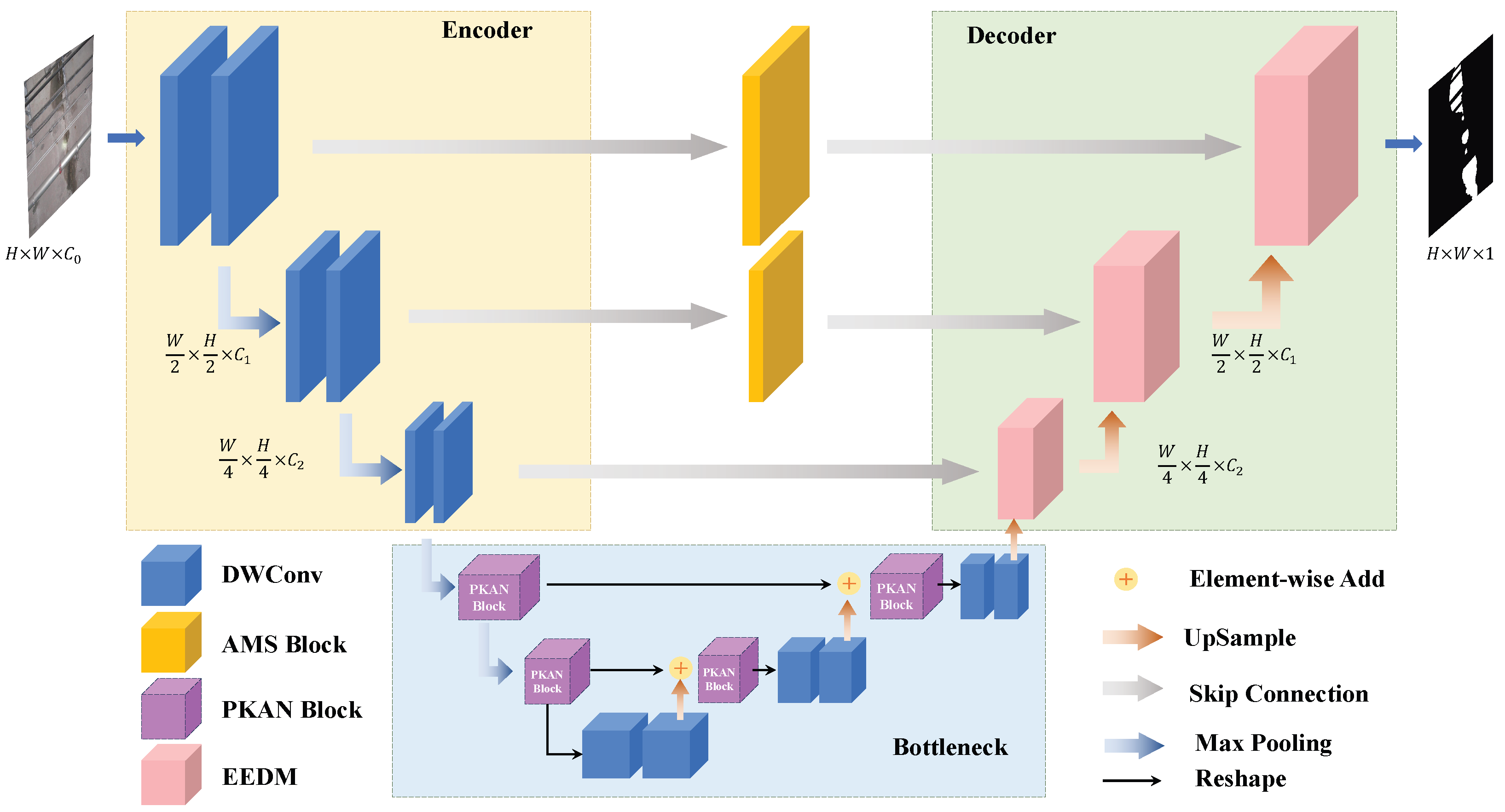

3.1. Overall Architecture

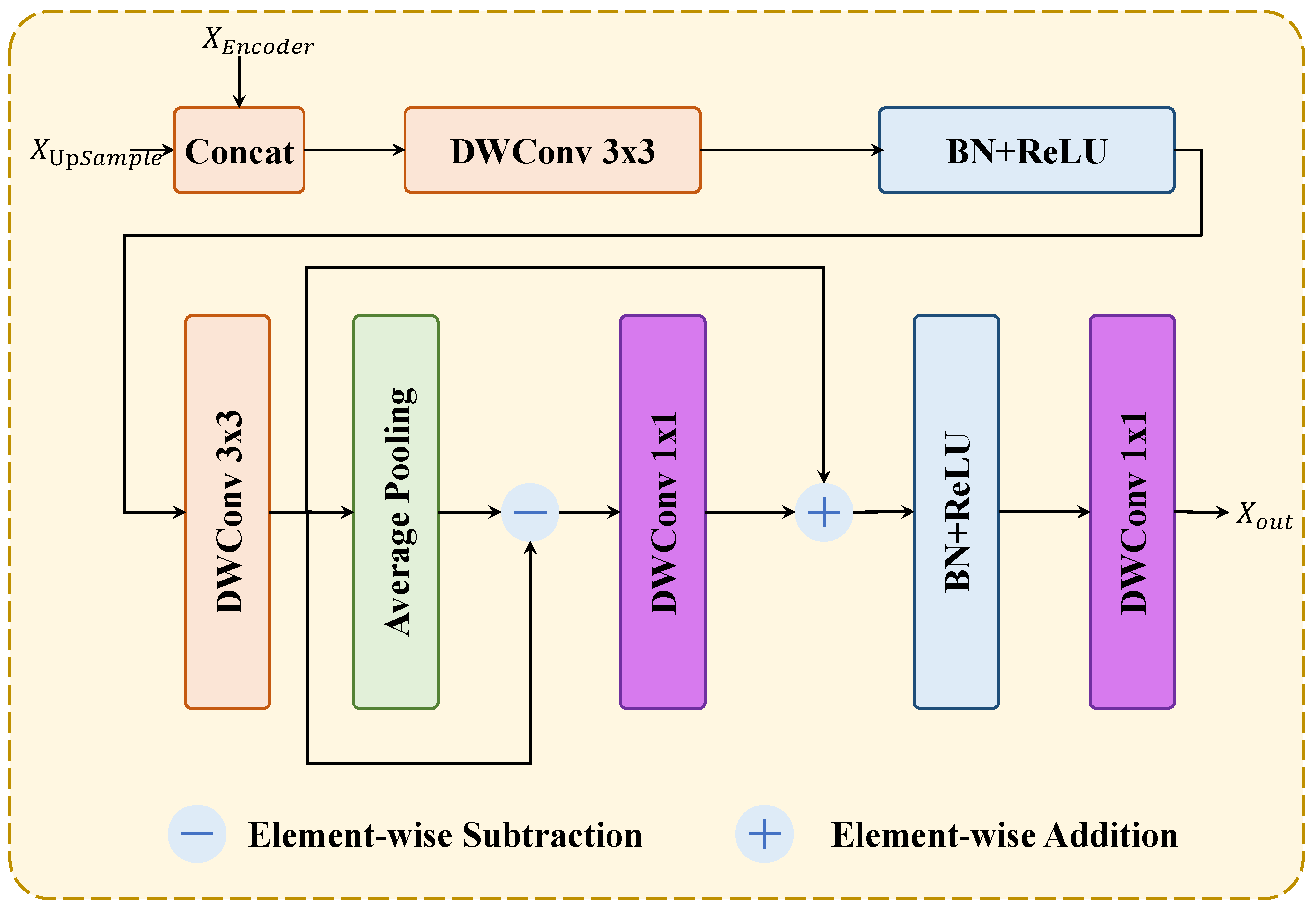

3.2. Efficient Backbone with Depthwise Separable Convolutions and EEDM

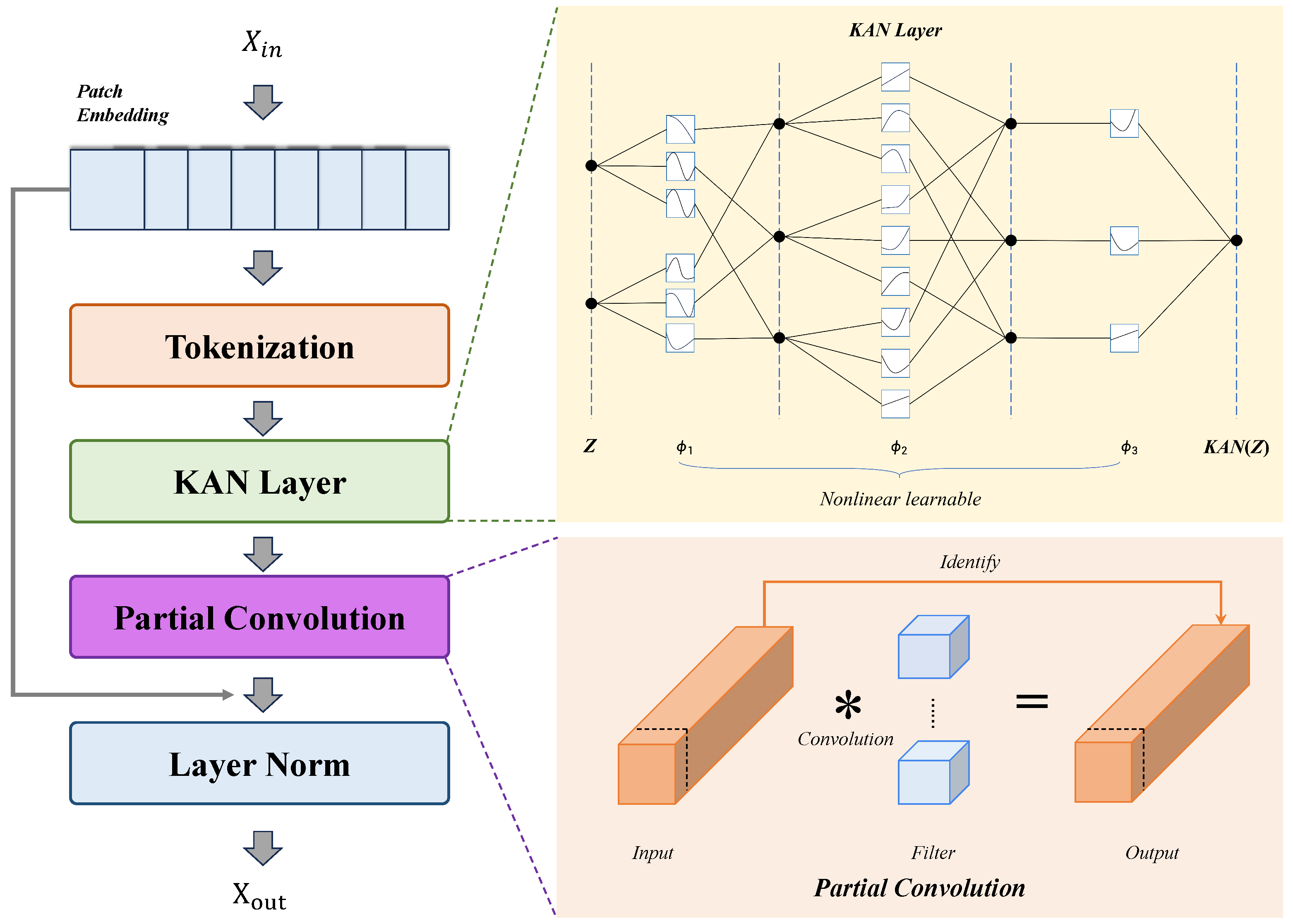

3.3. Tokenized PKAN Block

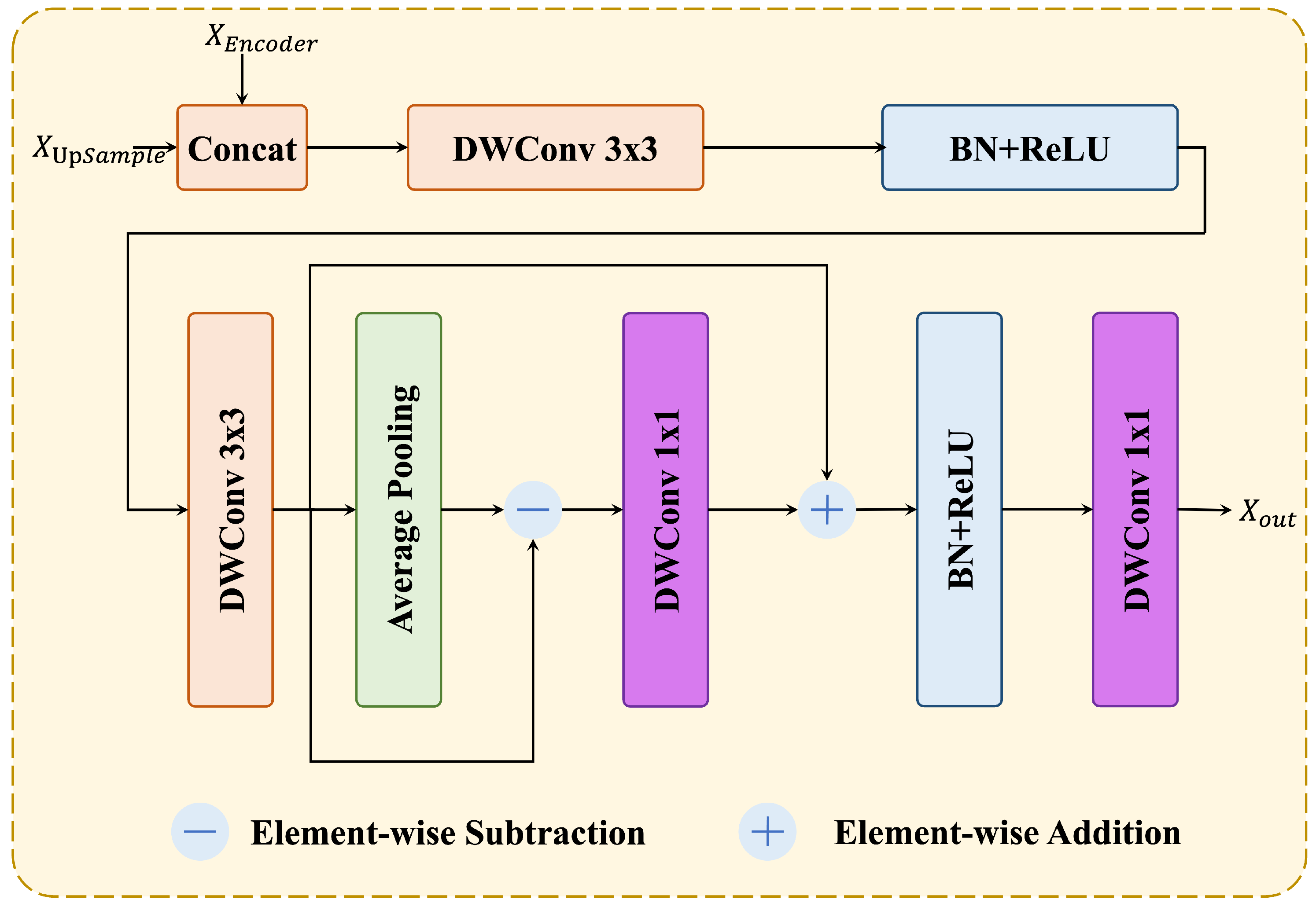

3.4. Adaptive Multi Scale Feature Extraction Block

4. Experiments Details

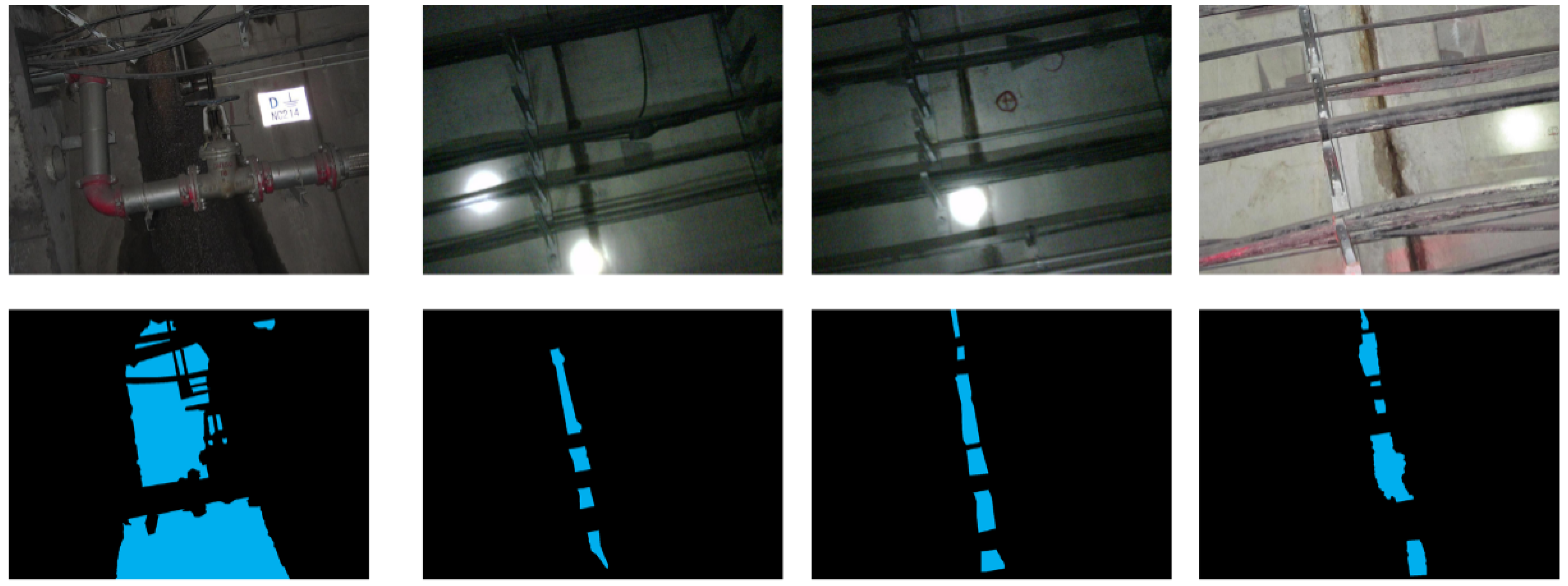

4.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

4.2. Experimental Details

4.3. Training Loss Function

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Quantitative Comparison

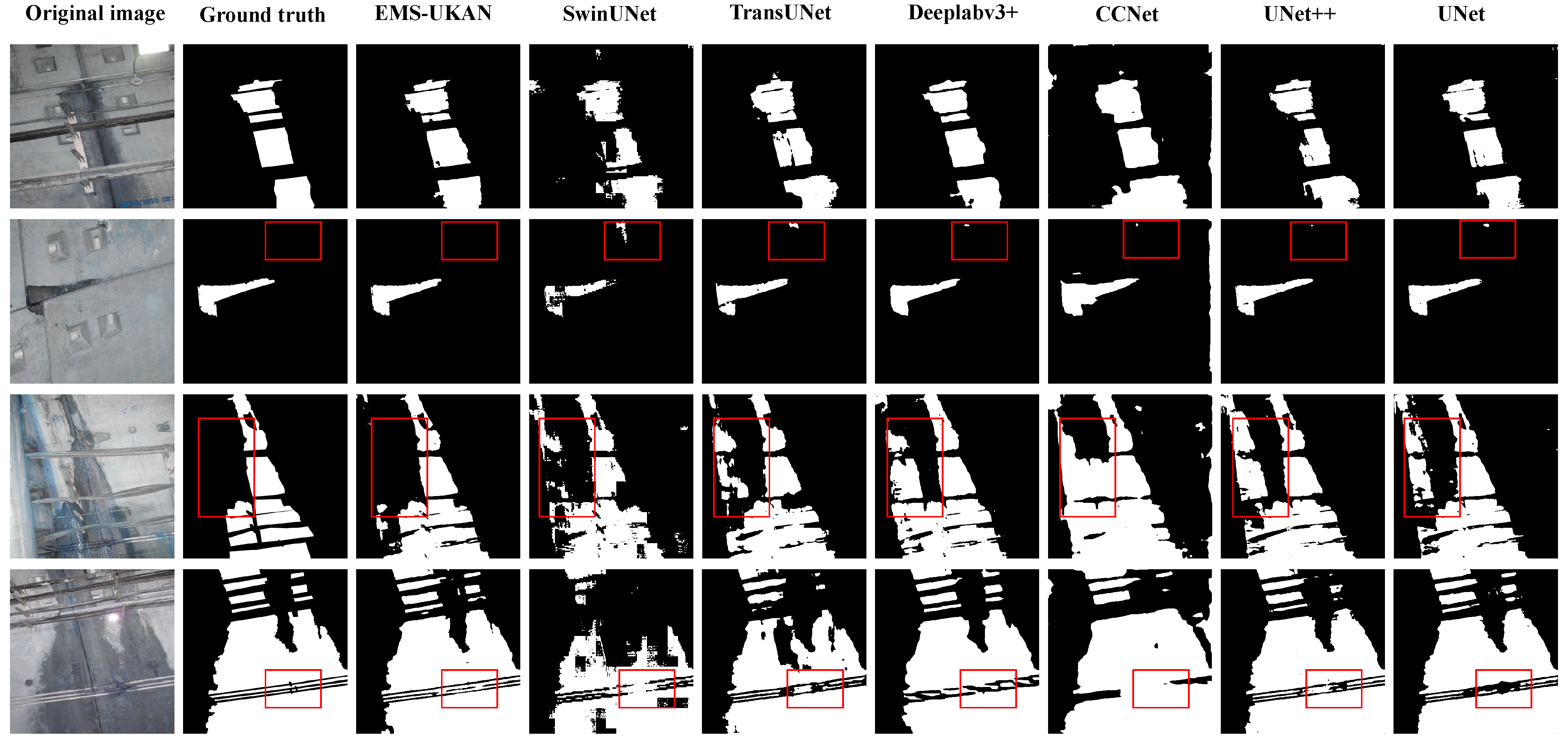

5.2. Qualitative Comparison

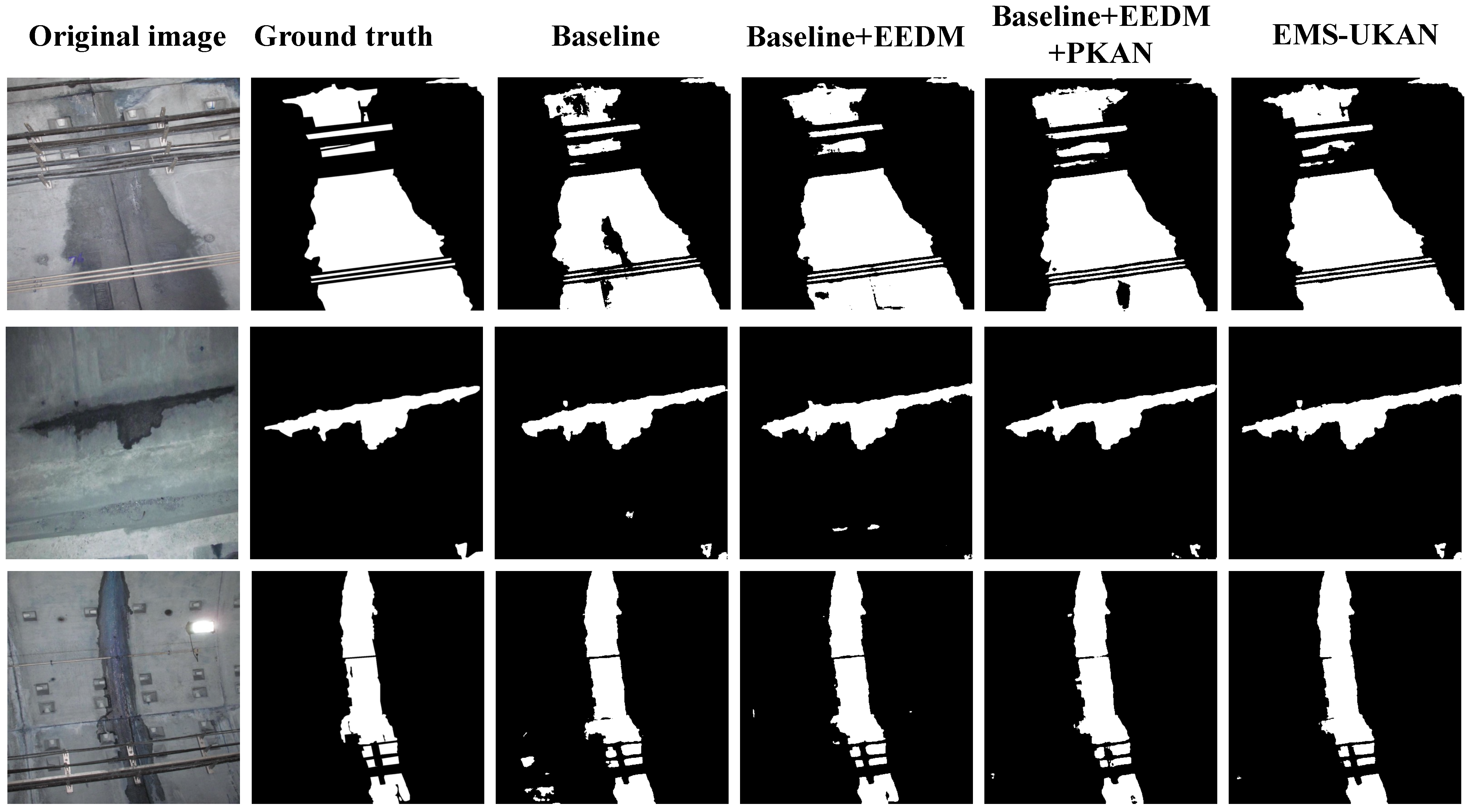

5.3. Ablation Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, X. Research on Inertial Force Suppression Control for Hydraulic Cylinder Synchronization of Shield Tunnel Segment Erector Based on Sliding Mode Control. Actuators 2025, 14, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Tang, T. LCJ-Seg: Tunnel Lining Construction Joint Segmentation via Global Perception. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 993–998. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Fu, S.; Guo, K.; Ferreira, V. Advances and challenges in water leakage detection techniques for shield tunnels: A comprehensive review. Measurement 2025, 257, 118763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Tang, T. Dmdsnet: A computer vision-based dual multi-task model for tunnel bolt detection and corrosion segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Bilbao, Spain, 24–28 September 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 4827–4833. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, M.; Ge, Z.; Chen, C. Experimental investigation of ground collapse induced by Soil-Water leakage in local failed tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Hu, X.; Tang, T.; Yuan, D. A lightweight metro tunnel water leakage identification algorithm via machine vision. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 150, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, N.; Wang, Z.; Kou, Y. EDT-Net: A Lightweight Tunnel Water Leakage Detection Network Based on LiDAR Point Clouds Intensity Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 7334–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, P.; He, B.; Li, W.; Song, T. Automated detection and segmentation of tunnel defects and objects using YOLOv8-CM. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 150, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, R.; Yu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ji, H. Localization of cyclostationary acoustic sources via cyclostationary beamforming and its high spatial resolution implementation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 204, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Hou, F.; Cui, G.; Ding, G. REN-GAN: Generative adversarial network-driven rebar clutter elimination network in GPR image for tunnel defect identification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Chiu, Y.C.; Wang, T.T.; Huang, T.H. Application and validation of simple image-mosaic technology for interpreting cracks on tunnel lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 34, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yao, X. Rapid detecting equipment for structural defects of metro tunnel. In Life Cycle Analysis and Assessment in Civil Engineering: Towards an Integrated Vision; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1561–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Adin, V.; Bader, S.; Oelmann, B. Leveraging acoustic emission and machine learning for concrete materials damage classification on embedded devices. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Sun, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, F. Inspection equipment study for subway tunnel defects by grey-scale image processing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 32, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, L.; Wang, N.; Ni, S. Research on Recognition Algorithm of Tunnel Leakage Based on Image Processing; Technical report, SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Attard, L.; Debono, C.J.; Valentino, G.; Di Castro, M. Tunnel inspection using photogrammetric techniques and image processing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. Tiny-machine-learning-based supply canal surface condition monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, S.; Song, S.; Qin, R.; Tang, Y. Remote sensing object detection in the deep learning era—A review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Song, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Wu, L. Water leakage and crack identification in tunnels based on transfer-learning and convolutional neural networks. Water 2022, 14, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, G. Optimization of Shield Tunnel Lining Defect Detection Model Based on Deep Learning. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2020, 47, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xie, Q.; Gong, X.; Yu, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J. Automatic defect detection of metro tunnel surfaces using a vision-based inspection system. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 47, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mo, J.; Xu, L.; Zheng, X. Lightweight Tunnel Leakage Water Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8n. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 25th China Conference on System Simulation Technology and Its Application (CCSSTA), Tianjin, China, 21–23 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Cai, X.; Shadabfar, M.; Shao, H.; Zhang, S. Deep learning-based automatic recognition of water leakage area in shield tunnel lining. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 104, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, N.; Xu, F.; Du, Y.; Xu, H. Visual detection method of tunnel water leakage diseases based on feature enhancement learning. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 153, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shi, G. Image segmentation of tunnel water leakage defects in complex environments using an improved Unet model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Luo, X.; Haruna, S.A.; Zareef, M.; Chen, Q.; Ding, Z.; Yan, Y. Au-Ag OHCs-based SERS sensor coupled with deep learning CNN algorithm to quantify thiram and pymetrozine in tea. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Hu, X.; Miao, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, D. Adaptive Measurement for High-Speed Electromagnetic Tomography via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, J. Unet 3+: A full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020–2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2012/file/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Paper.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Abbas, I.; Noor, R.S. Development of Deep Learning-Based Variable Rate Agrochemical Spraying System for Targeted Weeds Control in Strawberry Crop. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, T. Railway Automatic Switch Stationary Contacts Wear Detection Under Few-Shot Occasions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 14893–14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 459–479. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pvt v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; proceedings, part III 18. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.Y.; Tegmark, M. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. Intelligent Identification of Tunnel Lining Water Leakage Based on Deep Learning. Hans J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 12, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Su, C.; Han, G.; Dong, Y. Efficient segmentation of water leakage in shield tunnel lining with convolutional neural network. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Zheng, K.; Liu, S. DAEiS-Net: Deep Aggregation Network with Edge Information Supplement for Tunnel Water Stain Segmentation. Sensors 2024, 24, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Sun, L.; Gao, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X. WLAN: Water Leakage-Aware Network for water leakage identification in metro tunnels. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 22179–22189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Wu, Y.; Wan, L.; Shao, S.; Wu, H. SE-TransUNet-Based Semantic Segmentation for Water Leakage Detection in Tunnel Secondary Linings Amid Complex Visual Backgrounds. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, J. PDS-UKAN: Subdivision hopping connected to the U-KAN network for medical image segmentation. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2025, 2025, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Reda, F.A.; Shih, K.J.; Wang, T.C.; Tao, A.; Catanzaro, B. Image inpainting for irregular holes using partial convolutions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Gong, T.; Shan, Z. A novel noise-aided fault feature extraction using stochastic resonance in a nonlinear system and its application. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 11856–11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Huo, X.; Zhu, C.; Chen, S. Minimum redundancy maximum relevancy-Based multiview generation for time series sensor data classification and its application. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 12830–12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, S.; Yu, H.; Li, C.; Hu, X. SCESS-Net: Semantic consistency enhancement and segment selection network for audio-visual event localization. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2025, 262, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Tan, L.; Tang, T. Simultaneous Fault Diagnosis for Sensor and Railway Point Machine for Autonomous Rail System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; pp. 1011–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W. Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

| Model | GFLOPs | Param (M) | Acc (%) | IoU (%) | Dice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 124.37 | 13.4 | 85.96 | 78.60 | 83.27 |

| UNet++ | 138.86 | 9.16 | 86.03 | 79.18 | 83.79 |

| CCNet | 216.78 | 49.48 | 82.79 | 68.00 | 68.28 |

| Deeplabv3+ | 164.1 | 39.63 | 83.68 | 71.39 | 74.18 |

| TransUNet | 130.1 | 67.87 | 85.57 | 74.13 | 79.92 |

| SwinUNet | 30.88 | 27.18 | 84.16 | 64.31 | 72.51 |

| EMS-UKAN | 34.9 | 19.37 | 86.52 | 82.19 | 85.46 |

| Model | Acc (%) | IoU (%) | Dice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNet w/DWConv(Baseline) | 86.26 | 78.92 | 83.62 |

| Baseline + EEDM | 86.29 | 79.30 | 84.24 |

| Baseline + EEDM + PKAN | 86.31 | 81.70 | 84.95 |

| EMS-UKAN | 86.52 | 82.19 | 85.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, M.; Tan, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, X. EMS-UKAN: An Efficient KAN-Based Segmentation Network for Water Leakage Detection of Subway Tunnel Linings. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412859

He M, Tan L, Yang X, Liu F, Zhao Z, Wu X. EMS-UKAN: An Efficient KAN-Based Segmentation Network for Water Leakage Detection of Subway Tunnel Linings. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412859

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Meide, Lei Tan, Xiaohui Yang, Fei Liu, Zhimin Zhao, and Xiaochun Wu. 2025. "EMS-UKAN: An Efficient KAN-Based Segmentation Network for Water Leakage Detection of Subway Tunnel Linings" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412859

APA StyleHe, M., Tan, L., Yang, X., Liu, F., Zhao, Z., & Wu, X. (2025). EMS-UKAN: An Efficient KAN-Based Segmentation Network for Water Leakage Detection of Subway Tunnel Linings. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412859