Abstract

(1) Background: Surgical site infections (SSIs) pose a significant clinical challenge, with early detection hindered by the overlap between physiological postoperative inflammation and incipient infection. Continuous wound temperature monitoring offers a promising, non-invasive method to identify subtle thermal deviations that precede overt clinical signs. This review synthesizes current evidence on the utility of temperature monitoring as an early predictor of SSI and evaluates its clinical applications. (2) Methods: A narrative literature review was conducted using PubMed and Embase for English-language studies published between 2015 and 2025. Following PRISMA principles, eligible studies were selected that examined continuous or repeated local wound temperature measurements in adult postoperative patients and their association with a clinical diagnosis of SSI. (3) Results: Six studies met the inclusion criteria. Key findings indicate that infected wounds may paradoxically exhibit lower temperatures “cold spots” than non-infected wounds in the early postoperative period. Dynamic indicators, particularly the temperature difference (ΔT) between the wound and adjacent skin and the temperature trajectory over time, proved more predictive than single, isolated measurements. Confounding factors such as patient adiposity were noted to influence thermal signatures. (4) Conclusions: Wound temperature monitoring is a valuable strategy for the early risk stratification of SSI. The analysis of thermal trends and dynamic parameters holds greater diagnostic significance than single readings. Integration with other biomarkers may further enhance specificity, but the development of standardized measurement protocols is essential for reliable clinical implementation and improved postoperative outcomes.

1. Introduction

Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) continue to represent a significant, complex clinical problem worldwide, consistently leading to increased patient morbidity, substantially prolonging the necessary duration of hospitalization, and ultimately worsening the overall long-term prognosis for affected individuals [1]. These infections are not merely a clinical complication; among all categories of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), the surgical site infection is consistently cited as one of the most commonly reported infections globally [2]. Critically, beyond the immediate clinical consequences for the patient, SSIs impose a severe burden on the healthcare system: they substantially increase overall healthcare expenditures, frequently necessitate technically demanding reoperations to manage the pathology and, in their most severe manifestations, are directly associated with significantly elevated postoperative mortality rates [3]. In terms of epidemiological scale, it is estimated that approximately 300,000 SSIs occur annually in high-income countries alone, with even higher and more concerning rates reported in low- and middle-income countries, where data suggests they may afflict between 1% and 24% of all surgical procedures performed, underscoring the urgent need for more effective preventative and diagnostic strategies [4].

Patients afflicted with pre-existing metabolic or immunologic comorbidities, which notably encompass conditions such as diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, and malnutrition, exhibit a significantly heightened susceptibility to the development of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) [5]. These underlying systemic states critically impair local tissue perfusion, severely diminish the efficacy of immune cell function, and subsequently compromise the intrinsic wound healing capacity of the host. The confluence of these physiological deficits establishes a complex biological microenvironment within the surgical field that is overtly favorable for robust bacterial colonization and the subsequent rapid progression of infection [6,7]. The resulting poor vascularity and functional immune suppression create a prolonged vulnerability window that facilitates microbial invasion beyond the initial surgical insult. Early and accurate diagnosis of a nascent SSI, however, presents a substantial clinical and diagnostic challenge to the medical team. This difficulty stems primarily from the fact that the initial symptoms, which typically include localized swelling, erythema, and a localized increase in temperature, frequently overlap with and may simply reflect a normal, physiological inflammatory response that is an expected part of the standard post-operative healing cascade, rather than definitively indicating the presence of a pathological, escalating infection [8]. Consequently, the differentiation between benign inflammation and true microbial invasion requires careful, sustained clinical observation and often necessitates further investigative measures to confirm the infectious etiology.

Wound healing is fundamentally a dynamic, complex physiological process in which continuous alterations in microcirculation and tissue metabolism work in concert to generate characteristic and predictable thermal gradients. The initial inflammatory phase of this process is typically characterized by a period of increased local perfusion and resultant local hyperthermia, reflecting the heightened metabolic activity and immune cell recruitment at the injury site. Following this, during the subsequent proliferative phase, the wound temperature gradually equilibrates to match that of the surrounding healthy tissues as acute inflammation subsides and tissue remodeling begins [8]. Conversely, the onset of an infection profoundly disrupts this finely tuned biological sequence, leading instead to sustained local vasodilation, enhanced neutrophilic infiltration, and a marked increase in bacterial metabolism. This pathological cascade reliably manifests thermographically as a persistent or progressive elevation of the wound temperature [1,9]. Crucially, among all objectively measurable wound parameters, temperature is widely regarded as the most reliable, non-invasive indicator of the wound status, given that its variations and specific trajectories throughout the entire healing process systematically differ according to the wound type and underlying pathology [10]. This makes continuous thermal monitoring an indispensable tool for surveillance.

Infrared (IR) thermography presents a sophisticated, non-contact methodological approach for the comprehensive assessment of surgical wounds and their immediate surrounding tissues by facilitating the precise visualization of spatial and temporal temperature distributions. The core utility of this technique lies in its ability to enable the detection of subtle thermal asymmetry and fine-grained temperature gradients across the wound site. These deviations from normal thermal patterns can serve as early biophysical indicators potentially signifying the onset of a developing infection, thereby offering a crucial pre-symptomatic detection capability. Moreover, the inherent non-invasive nature of IR thermography is paramount, as it critically minimizes the risk of cross-contamination or mechanical disruption of the surgical site [11]. The field has seen considerable technological advancements, particularly with the widespread development and miniaturization of highly sensitive, portable IR cameras and their subsequent seamless integration with robust digital data processing platforms. This evolution has significantly enhanced the practical applicability and accessibility of the technique, suggesting considerable promise for future utilization in both traditional clinical settings and increasingly in remote or telemedicine-based Surgical Site Infection (SSI) monitoring programs [11]. This technological progression is setting the stage for more proactive, continuous surveillance of postoperative recovery.

Building on these developments, recent evidence underscores the importance of carefully selecting thermal descriptors when interpreting IR-derived temperature data. Research on nonsteady thermal states such as those following physical exertion shows that relying solely on the maximal temperature within the ROI can bias interpretation. Although Tmax is easily obtained and strongly related to other upper-range metrics, its dependence on the extreme upper tail renders it susceptible to noise and disproportionately influenced by isolated hot spots. In contrast, more integrative statistics provide greater robustness but may miss subtle perfusion-related elevations that Tmax can detect. These observations highlight that thermal indicators differ in sensitivity and vulnerability to artefacts, reinforcing the need for context-dependent metric selection to achieve reliable wound thermography assessment [12].

Intelligent dressings and advanced sensors that enable continuous wound temperature monitoring offer substantial potential for the non-invasive and highly timely detection of early infection-related changes [13,14,15,16]. This is achieved through the sophisticated analysis of thermal trends, the identification of differences relative to the surrounding healthy skin (ΔT), the detection of thermal asymmetry across the wound surface, and the interpretation of disrupted circadian patterns. Utilizing these integrated data streams makes it possible to identify subtle physiological deviations within the wound microenvironment even before the onset of overt clinical symptoms or measurable alterations in systemic biomarkers [13,14,15,16]. This capability positions continuous wound temperature monitoring, particularly when combined with robust predictive analytics, to serve as the foundation for innovative new tools dedicated to early Surgical Site Infection (SSI) diagnosis [17,18]. By allowing for such early and objective assessment, these systems promise to enable personalized intervention strategies and ultimately contribute significantly to the reduction in severe complications [17,18]. Consequently, the detailed assessing of wound temperature variations can powerfully support a more precise wound status evaluation, contribute effectively to individualized treatment planning and provide crucial predictive insights into the healing trajectories of patients [10].

Equally important as early infection detection is the broader, systemic role of continuous monitoring systems within the context of modern surgery and comprehensive postoperative care [19]. Extending beyond the crucial function of identifying infection, such advanced systems can provide essential support for the objective assessment of wound healing progression, allowing clinicians to optimize the precise timing of interventions such as suture removal or necessary dressing changes, and thereby significantly facilitate highly individualized patient management strategies [20]. Furthermore, the strategic integration of sensor-derived data with electronic health records (EHRs) and sophisticated telemedicine platforms fundamentally opens new possibilities for robust remote monitoring, which crucially reduces the need for frequent, resource-intensive in-person clinic visits [21]. This capability is particularly vital as it enables earlier and more effective intervention for complications in patients managed in outpatient or resource-limited settings [21]. Moreover, these same continuous monitoring systems inherently serve as valuable, high-fidelity research tools, providing real-time, granular data on wound physiology and the precise response kinetics to different therapeutic strategies being evaluated [22]. This dual clinical and research utility confirms their importance as an indispensable component of future surgical care models.

Although numerous studies have examined temperature monitoring, many reviews highlight that, despite the promising potential of thermography, additional research is required to validate its routine clinical application and to establish standardized diagnostic thresholds. In this context, our review integrates these emerging insights and specifically focuses on postoperative wound assessment, addressing an area that remains insufficiently characterized.

Despite the genuinely promising preliminary results demonstrated by this technology, a critical gap persists in the widespread clinical adoption of thermal monitoring: the current lack of standardized protocols, absence of universally accepted decision thresholds, and a need for the unified interpretation of temperature variations observed in post-operative wounds [8]. The absence of these foundational methodological elements substantially hinders the reliable and consistent application of the technique across diverse clinical settings. Therefore, conducting a structured review of the comprehensive literature specifically concerning the thermal characteristics of postoperative wounds represents an absolutely necessary and foundational step. This rigorous synthesis of existing data is vital for the eventual development of highly precise monitoring methods and robust infection prediction algorithms [8]. By methodically consolidating and evaluating existing knowledge derived from various research efforts, such endeavors can effectively pave the way for the establishment of clear, evidence-based clinical guidelines. This crucial progression from research synthesis to practical guidelines will ultimately serve to significantly improve patient safety and elevate the quality of surgical outcomes on a broad scale [23].

Physiology and Pathophysiology of Wound Inflammation

To enhance the comprehension of postoperative wound monitoring, the article necessitates a detailed elucidation of the physiological and pathological thermal dynamics observed in both sterile and infected wounds. This foundational context is crucial for interpreting local thermal responses, which are a direct reflection of underlying immune and microvascular coordination.

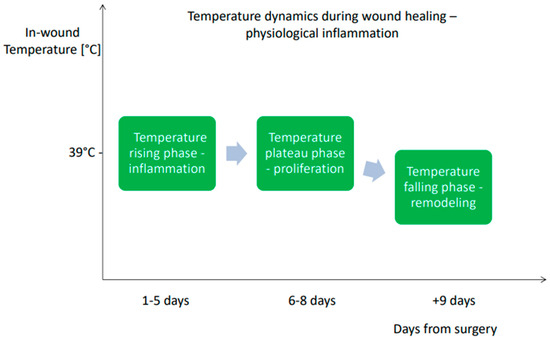

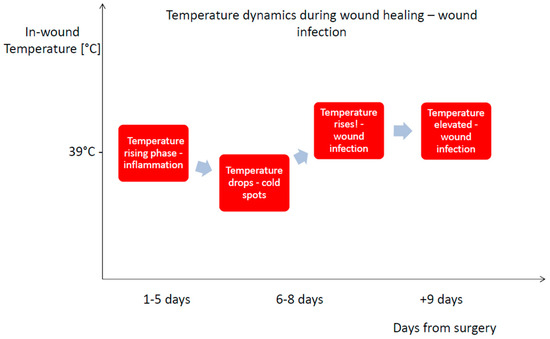

In uncomplicated healing, early hyperthermia is driven primarily by inflammation, dominated by increased metabolic activity of resident immune cells, prostaglandin-mediated vasodilation, and transient recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages [24,25,26,27]. During the initial inflammatory phase of uncomplicated healing, local wound temperature typically reaches approximately 39 °C as shown in Figure 1 [28,29]. This physiological response is self-limiting as cytokine concentrations decline, perfusion stabilizes, and tissue metabolism gradually normalizes during the transition into the proliferative, and remodeling phase [30,31]. In contrast, pathogen invasion initiates a qualitatively different and far more sustained inflammatory cascade. Recognition of microbial components by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors on neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells, triggers rapid NF-κB–mediated transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 [32,33,34]. These mediators amplify local vasodilation, increase endothelial permeability, and enhance leukocyte recruitment, markedly increasing regional blood flow and the intensity of metabolic processes [35,36]. Bacterial proliferation itself further contributes to localized thermogenesis through intensified nutrient utilization and oxygen consumption within the wound microenvironment [37,38,39]. The temperature within the wound undergoes dynamic changes, in the early postoperative phase, infection may initially manifest as localized hypothermic “cold spots” due to perfusion disturbances [40]. Following this period, the temperature within the wound begins to rise, and once the threshold of 39.5 °C is exceeded, it is regarded as an indicator of an evolving infection. as shown in Figure 2 [16,29]. The fluctuations in wound temperature make diagnosis more challenging and necessitates evaluating the dynamics of temperature changes rather than relying solely on absolute values [1,41]. The combined effect of host-driven cytokine signaling and pathogen-driven metabolic activity generates a thermal profile characterized by sustained or progressively rising temperature, exceeding the physiological peak seen in non-infected postoperative inflammation [26,42]. This pathophysiological framework explains why continuous thermal monitoring can reliably detect the transition from normal healing to infection even before overt clinical symptoms emerge. It is important to emphasize that tissue temperature is generally higher than the corresponding surface temperature measured by infrared (IR) thermography, a topic that is discussed later in the article [40].

Figure 1.

The characterization of temperature dynamics during wound healing—physiological inflammation [29].

Figure 2.

The characterization of temperature dynamics during wound healing—wound infection [29].

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative literature review was conducted using a systematically structured search strategy with the explicit aim of evaluating the critical role of temperature monitoring in postoperative wounds, focusing specifically on the analysis of the temperature trajectory change as a potential, non-invasive indicator of Surgical Site Infection (SSI). The core objective was to establish the viability of using these thermal signatures to act as an effective and objective early warning system. The authors chose a narrative review format with a systematic search strategy in order to ensure an objective approach to the subject matter and to obtain maximally precise results regarding data relevant to the issues addressed in this study. This review was meticulously designed to synthesize the current body of evidence regarding normal and aberrant temperature trajectories observed in healing wounds, to identify the most reliable diagnostic parameters (such as ΔT and Tmax), and to explore current and emerging clinical applications of thermal data within the context of early SSI detection. The entire review protocol, including the search and selection strategy, was developed a priori using clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the PICOS framework, a variation in the original PICO model proposed by Richardson et al. in 1995 [43]. The PICOS/PICO approach is among the most widely used tools for formulating clinically oriented research questions, including those related to diagnosis, therapy, and etiology [44].

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive systematic search was performed across two major electronic databases—PubMed (MEDLINE) and Embase, due to their broad and complementary biomedical coverage, controlled vocabularies (MeSH and Emtree), and robust indexing of clinical and translational literature. Pilot searches indicated substantial overlap with diminishing returns from additional databases for this focused topic. To mitigate the risk of omission, database searches with backward/forward citation chasing of key articles and screening of relevant review bibliographies was complemented. The search was limited to full-text articles published in English between 1 January 2015, and 31 January 2025. This timeframe was selected to capture recent technological advances and digital health monitoring systems while ensuring clinical relevance.

The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms with free-text keywords using Boolean operators. The following search string was used for Embase:

‘adult’/exp AND (‘thermography’/exp OR ‘temperature measurement’/exp) AND (‘wound infection’/exp OR ‘surgical infection’/exp) AND (2015:py OR 2016:py OR 2017:py OR 2018:py OR 2019:py OR 2020:py OR 2021:py OR 2022:py OR 2023:py OR 2024:py OR 2025:py) AND ('controlled study'/de OR 'human'/de OR 'meta-analysis'/de OR 'observational study'/de OR 'prospective study'/de OR 'randomized controlled trial'/de OR 'retrospective study'/de OR 'systematic review'/de) AND 'article'/it

A parallel search strategy was adapted for PubMed using equivalent terms and keywords. Additional keywords included: “temperature” since PubMed did not recognize the term “temperature measurement” as an indexed phrase.

2.2. Study Selection

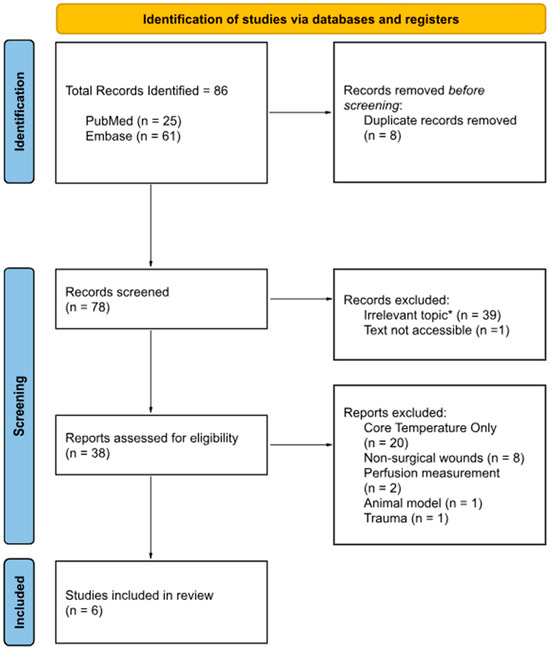

The study selection process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—PRISMA 2020 principles [45]. All retrieved records were imported into Microsoft Excel for screening and data management. Duplicate records were identified and removed using automated tools combined with manual verification.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The selection of publications was based on the following PICOS framework:

- -

- Population (P): Adult patients following any type of surgical procedure (in vivo human studies). Studies were excluded if they involved animal models, in vitro experiments, or focused exclusively on chronic wounds (e.g., diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers, venous leg ulcers) without postoperative context.

- -

- Intervention (I): Continuous, repeated, or serial objective measurement of wound temperature using digital sensors, wearable devices, thermal imaging systems (infrared thermography, LWIT), or smart dressings with integrated temperature monitoring capabilities. Studies were excluded if they reported only single-point measurements, relied on subjective assessment (palpation), or measured exclusively core body temperature without local wound assessment.

- -

- Comparison (C): Standard postoperative care, clinical assessment, alternative monitoring methods (e.g., laboratory biomarkers, imaging), or control groups without temperature monitoring. Studies without a comparator were included if they provided diagnostic performance metrics or described temperature patterns associated with SSI.

- -

- Outcomes (O): Primary outcomes included the association between wound temperature changes and clinical diagnosis of SSI according to standardized definitions (e.g., CDC/NHSN criteria, WHO definitions). Secondary outcomes included diagnostic performance indicators (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value [PPV], negative predictive value [NPV], area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC]), temperature thresholds (ΔT, Tmax), trajectory patterns, and integration with other biomarkers (pH, inflammatory markers).

- -

- Study design (S): Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, systematic reviews, and scoping reviews were included. Excluded study types included: non-systematic narrative reviews without structured methodology, single case reports, editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts without full-text availability, and purely technical or engineering articles lacking clinical validation or patient data.

2.4. Search Results

The initial database search identified 86 records: 25 from PubMed and 61 from Embase. After removal of 8 duplicate records, 78 unique citations remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 39 records were excluded based on title and abstract review, primarily due to irrelevant topics, wrong patient population (chronic wounds), or the inability to access full-text article.

The remaining 38 full-text articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Following detailed evaluation, 32 articles were excluded for the following reasons:

- -

- Studies focusing on chronic wounds without postoperative context (n = 8).

- -

- Measurement of core body temperature only, without local wound assessment (n = 20).

- -

- Two articles described the use of IR imaging in tissue perfusion measurement.

- -

- One study was an animal model.

- -

- One publication was excluded on the basis of including surgical patients after major lower extremity trauma.

Ultimately, 6 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. Three observational studies, two prospective studies, one cross-sectional study. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram; Source: Page MJ et al. BMJ 2021;372:n71 [45]. * Thirty-nine records were excluded as they were retrieved solely due to keyword matches, yet their scope was misaligned with the predefined inclusion criteria and offered no substantive relevance to the objectives of this narrative review.

Due to substantial heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, surgical procedures, temperature monitoring technologies, measurement protocols, and outcome definitions, a quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a narrative synthesis approach was employed to summarize and interpret findings across studies.

Data were synthesized thematically according to:

- -

- Temperature monitoring technologies and measurement protocols.

- -

- Diagnostic parameters (ΔT, Tmax, trajectories).

- -

- Clinical applications and implementation considerations.

Results were organized into a table to facilitate comparison across studies. Temperature patterns were categorized as physiological (normal postoperative healing) versus pathological (infection-associated). Where possible, ranges of diagnostic thresholds and performance metrics were reported.

All data extraction, quality assessment, and synthesis were managed using Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize study characteristics and outcomes.

3. Results

A total of six studies published between 2015 and 2025 met the inclusion criteria, comprising four prospective observational studies, one prospective exploratory study and one cross-sectional study. The main characteristics and findings of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

3.1. Study Cohorts and SSI Incidence

Four prospective observational studies were synthesized. Two studies enrolled post-caesarean women and two enrolled patients following colorectal enterostomy closure or other abdominal surgery. SSI incidence ranged from 25% to 50% across cohorts:

- -

- Enterostomy-closure ward cohort: 15/60 (25%) developed SSI within 30 days [46].

- -

- Obese post-caesarean cohort: 14/50 (28%) received antibiotics for presumed SSI by day 30 [47].

- -

- Pilot enterostomy-closure series: 5/10 (50%) infected by day 7 [41].

- -

- Post-caesarean feasibility cohort: 2/20 with established infection at presentation [48].

Table 1.

Review of studies on wound temperature as an indicator of surgical site infection.

Table 1.

Review of studies on wound temperature as an indicator of surgical site infection.

| First Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Type of Surgery | Device Used for Temperature Monitoring | Number of Confirmed SSI (%) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benvenisti et al., 2024 [49] | Israel | Prospective Observational Study | 45 Patients | Abdominal Surgery | LWIR Camera | 10 (22%) | SSIs were characterized by a reduction in IR wavelength that appeared within regions previously exhibiting higher IR wavelength emission. |

| Childs et al., 2016 [48] | England | Prospective Observational Study | 20 Patients | Cesarean Section | FLIR Camera | 3 (15%) | Four participants showed >2 °C “cold spots” on thermal images; three later developed wound infections (one patient could not be reached for a follow-up). The temperature difference was significant for infected cases (p = 0.006) |

| Siah et al., 2019 [46] | Singapore | Prospective Observational Study | 60 Patients | Colorectal Surgery | FLIR Camera | 15 (25%) | For noninfected surgical wounds, the mean skin surface temperature readings taken at 0–4 days ranged from 33.9–35.6 °C, whereas infected ones ranged from 34.1–35.4 °C |

| Childs et al., 2019 [47] | England | Prospective Observational Study | 50 Patients | Cesarean Section | FLIR Camera | 14 (28%) | A 1 °C drop in abdominal temperature or widening of the wound–abdomen temperature difference significantly increased infection risk (OR ≈ 2–3), with logistic models predicting wound outcomes correctly in 70–79% of cases |

| Siah et al., 2015 [41] | Singapore | Prospective Exploratory Study | 10 Patients | Abdominal Surgery | LWIR Camera | 5 (50%) | Development of ‘cold’ spots by day 3 could be an objective indication of a potential SSI, although abdominal fat may alter the appearance of the thermal wound map towards that of an infected rather than a healing wound |

| Fridberg et al., 2024 [11] | Denmark | Cross-sectional study | 1970 Pin Sites | Orthopedic Surgery | FLIR Camera | 231 (12%) | There was a significant 0.9 °C temperature difference (CI 0.7–1.1) between clean and inflamed pin sites, with 34.1 °C identified as the optimal cut-off to distinguish between them |

3.2. Temporal Evolution of Wound and Abdominal Temperatures (Days 0–4)

In the immediate postoperative period, both infected and non-infected wounds showed progressive warming from Day 0 to Day 4. However, infected wounds demonstrated significantly lower surface temperatures than non-infected wounds on postoperative Days 1–2:

- -

- Day 1: median temperature lower in infected vs. non-infected (U = 216, Z = −2.07, p = 0.03; also significant for highest reading, U = 211.5, Z = −2.15, p = 0.03).

- -

- Day 2: median lower in infected vs. non-infected (U = 171.5, Z = −2.84, p = 0.01); lowest reading also lower (U = 185.5, Z = −2.60, p = 0.01).

- -

- No statistically significant between-group differences at Day 0, Day 3, or Day 4 [46].

Descriptively, non-infected wounds increased from approximately 33.9–35.6 °C (mean range) over Days 0–4 versus 34.1–35.4 °C (mean range) for infected wounds, with the between-group gap narrowing by Days 3–4 [46].

3.3. Qualitative Thermographic Signatures: “Cold Spots” and Delayed Warming

In the examined cases, infected wounds commonly exhibited discrete “cold spots”, defined as localized low-temperature territories, situated either directly along or immediately adjacent to the incision line; occasionally, these thermal anomalies were observed tracking perpendicularly away from the main surgical scar. Notably, in several of the analyzed instances, these localized cold areas precisely corresponded to underlying subcutaneous purulent collections which were subsequently drained or expressed during clinical management [41]. Furthermore, detailed pixel-level thermal profiling performed following caesarean sections definitively identified a larger negative ΔT (calculated as the healthy reference skin temperature minus the scar/wound temperature) in those wounds confirmed as infected. This negative difference often exceeded 2−4 °C, providing a strong thermal signature. Conversely, the vast majority of non-infected scars typically demonstrated a ΔT that remained within ±1 °C when assessed at Day 2 post-operation [48]. In sharp contrast, the anticipated and expected thermal pattern for non-infected wounds involved an early reduction in the initial cold linear scar appearance and a progressive peri-incisional warming by Days 3–4. Crucially, any failure of the wound to exhibit this warming trend, or the distinct re-emergence or enlargement of cold territories observed by Day 3, was statistically and clinically associated with a subsequent diagnosis of later infection within the specific enterostomy-closure cohort studied [41].

3.4. Influence of Adiposity on Abdominal Skin Temperatures

In a study focusing on healthy volunteers, a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) was systematically observed to be associated with a lower mean abdominal skin temperature across several distinct abdominal regions, particularly within the umbilical and lumbar territories [41]. This finding is fundamentally consistent with the biophysical effect of increased subcutaneous adipose tissue acting as thermal insulation [41]. Translating these principles to the surgical context, a specific observation was made in postoperative patients: an obese but non-infected subject exhibited a delayed transition from the initial “cold” to the subsequent “warm” scar appearance. This strongly suggests that underlying adiposity itself may inherently blunt or significantly delay the expected peri-incisional warming trajectory, even when the physiological healing process is progressing normally and in the absence of any true infectious pathology [41]. Furthermore, within the specific cohort of obese patients post-caesarean section, the most significant prognostic value for predicting infection resided less in the absolute wound temperature (which tended to remain generally elevated) and more significantly in the low adjacent abdominal temperature and the resulting widened wound-to-adjacent-abdomen temperature gradient that was detectable prior to the definitive clinical diagnosis [47].

3.5. Ancillary Observations

Visual assessment relying solely on the scrutiny of digital photographs by experienced clinicians demonstrated notably poor inter-rater agreement concerning the capacity to predict a later Surgical Site Infection (SSI) [47]. This lack of consensus among experts strongly underscores the intrinsic value and necessity of employing objective, thermography-based metrics for reliable wound surveillance. Furthermore, across the various collected datasets, it was consistently observed that core body temperature did not significantly differ between the infected and non-infected patient groups, indicating the absence of systemic fever as a differentiating factor. Given that ambient environmental conditions were systematically controlled or meticulously recorded, the observed thermal differences between the groups unequivocally reflect local alterations in tissue perfusion and/or inflammatory states, rather than merely being a consequence of a generalized, systemic fever response.

3.6. Summary of Key Quantitative Signals

The comprehensive analysis of thermographic data establishes distinct and highly informative patterns that delineate the trajectory of healing versus the onset of infection during the critical post-operative period. In the early postoperative period (Days 1–2), a critical finding is that infected wounds are measurably cooler than their non-infected counterparts, an observation consistently documented with small-to-moderate effect sizes [46]. This localized hypothermia is counterintuitive yet crucial, often suggesting underlying issues like compromised perfusion rather than the superficial warmth of acute inflammation. Extending into post-caesarean surveillance (Days 2–7), thermal monitoring offers superior predictive value, where the earliest indicators that reliably precede the clinical diagnosis of Surgical Site Infection (SSI) include a lower overall abdominal temperature and, most significantly, a wider wound-to-adjacent-abdomen temperature gradient [47]. For robust quantitative assessment, the most potent single-parameter discrimination between healing and infected cases is provided by the abdominal temperature recorded specifically on Day 7, alongside the Wound-Adjacent Temperature Difference (WATD) assessed on both Day 2 and Day 7 [47]. Beyond quantitative metrics, several crucial qualitative flags are strongly characteristic of impending infection or severely delayed healing [41,48]: these encompass the presence or progression of peri-incisional “cold spots” (localized low-temperature areas), the failure of the surgical site to exhibit the expected progressive warming trend by Day 3–4, and the identification of marked negative ΔT profiles along the scar line, confirming that the incision is distinctly cooler than the surrounding reference skin [41,48]. Together, these findings rigorously support local wound temperature monitoring as a possibly feasible, objective adjunct for the early risk stratification of SSI, providing actionable thermal thresholds and characteristic image features that emerge well before the presence of overt clinical signs, thereby facilitating proactive intervention.

4. Discussion

Continuous monitoring of postoperative wound temperature constitutes a highly valuable method for the early detection of subtle deviations in tissue perfusion and local inflammatory response, changes that frequently and significantly precede the development of overt clinical signs of infection. The practice of diligently monitoring the temperature profile of a surgical wound is therefore of critical importance, particularly throughout the first week following wound formation, as this period is decisive. Thermal data provides valuable, non-invasive insight into the delicate regenerative processes or, conversely, undesirable pathophysiological changes actively occurring within the wound area and the adjacent tissue bed. This comprehensive assessment capability is vital as it not only facilitates an effective and objective assessment of the healing dynamics of the damaged tissue but also allows for a prompt and targeted clinical response should pathological developments be detected [10]. Among the numerous metrics derived, specific parameters such as the temperature difference (ΔT), the maximum temperature (Tmax), and a rigorous trajectory analysis of temperature changes over time demonstrate the greatest diagnostic potential. This potential is significantly amplified when these thermal metrics are combined with concurrent perfusion and local pH data [9]. However, realizing the full scope of their clinical utility requires the strict standardization of all measurement procedures and a meticulous consideration of potential confounding factors, such as environmental temperature and patient systemic status, to ensure the reliability and interpretability of the data [9].

A noteworthy finding, consistently reported across several included studies, is the paradoxical appearance of localized hypothermia in wounds that subsequently develop SSIs. Analysis of postoperative abdominal wounds using Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR) imaging revealed that SSIs often manifest as areas of lower infrared emission, or “cold spots,” developing in regions that were previously warming as part of the normal healing cascade [49]. This phenomenon was also observed in prospective studies involving post-caesarean and abdominal surgery patients, where the emergence of such “cold spots” by the second or third postoperative day served as an early indicator of subsequent infection [41,48]. These observations underscore the critical importance of dynamic assessment, as a single thermal image taken out of context is unlikely to be diagnostic. Instead, the evaluation of healing is best achieved through continuous, daily comparisons against a baseline thermal profile established immediately after skin closure [49]. The subtle nature of these changes is further highlighted by findings showing minimal differences in the absolute temperature ranges between infected and non-infected wounds, whereas the temperature trajectory over time shows statistically significant variations, reinforcing the argument that temporal analysis is more valuable than single-point measurements [46].

Further complicating the rigorous interpretation of thermal data are the numerous patient-specific physiological factors and the anatomical context of the specific wound site. This complexity is vividly illustrated in a detailed study focused exclusively on obese women following caesarean sections, where a significant and reliable predictor of infection was not the absolute temperature of the wound itself, but rather the temperature measured in the adjacent abdominal region [47]. Specifically, a 1 °C decrease in the temperature of this adjacent tissue area was statistically associated with an approximately threefold increase in the odds of developing a Surgical Site Infection (SSI) [47]. This crucial finding powerfully suggests that patient adiposity can substantially alter the thermal landscape through its insulating effects, potentially masking or significantly delaying the expected peri-incisional warming trajectory even in genuinely non-infected wounds, a confounding factor also corroborated in other preliminary exploratory research [41]. Respiration-driven thermal fluctuations introduce an additional physiological confounder that can meaningfully modify abdominal temperature patterns and thus affect IR data interpretation. Comparative analyses of thoracic versus diaphragmatic breathing demonstrate distinct temporal thermal behaviors: thoracic breathing produces a delayed but progressive temperature rise in the upper thorax followed by gradual cooling, whereas diaphragmatic breathing elicits an early, near-linear decline that normalizes only after the exercise ends. Correlation analyses (R > 0.85) further show that respiratory activity can synchronously influence broad regions of the anterior torso. These observations indicate that breathing mechanics generate structured thermal variability that must be considered when interpreting temperature distributions near postoperative abdominal wounds [50]. In sharp contrast, the characteristic thermal signature of inflammation can differ markedly in alternative clinical scenarios. For example, in the specific context of orthopedic pin-site inflammation, a statistically significant increase of 0.9 °C was precisely identified as the key differentiator between sites classified as clean versus actively inflamed, with a specific temperature of 34.1 °C established as an optimal diagnostic cut-off threshold [11]. This fundamental distinction underscores that thermal signatures are intrinsically highly context-dependent, necessitating the development of tailored diagnostic algorithms and standardized protocols that are specific to different surgical sites and unique patient populations to ensure both the accuracy and reliability required for robust clinical implementation.

Collins et al. provided empirical evidence demonstrating that a point measurement of the central wound temperature, specifically acquired using a commercially available IR camera (FLIR ONE Pro), is strongly correlated with the mean temperature calculated across the entire wound surface, achieving a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.977) [9]. This high correlation validates the practical utility of taking a single, well-placed thermal measurement. Furthermore, the study suggested that the temperature difference between the wound and the surrounding healthy skin (ΔT), particularly a deviation of approximately 1.1 °C, may reliably serve as a critical early indicator of developing infection [9]. These findings collectively emphasize the significant practical value of objective thermal data in informing clinical decision-making processes and underscore the potential efficacy of utilizing simple, well-positioned thermal sensors for the rapid detection of subtle temperature deviations indicative of pathology. Building upon these thermal measurement advancements, although considerable advancements in temperature sensor technology have been observed over time, Li J. suggested that the integration with other continuous monitoring systems that simultaneously measure supplementary parameters such as humidity or mechanical pressure could also prove substantially beneficial for truly comprehensive human health monitoring [51]. This convergence of technologies represents a significant developmental potential for advanced wound parameter monitoring systems, which—by systematically collecting a broader, multi-modal range of data—could ultimately achieve a substantially greater clinical effectiveness and diagnostic precision than single-parameter approaches [51].

Frey et al. introduced a sophisticated “system-on-chip” platform that strategically combines continuous monitoring of biophysical parameters, such as temperature and pH, with the simultaneous electrochemical detection of key inflammatory biomarkers, specifically C-reactive protein (CRP) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) [36,52]. This innovative multi-sensor integration significantly enhances the diagnostic specificity and reliability for early infection detection compared to traditional single-parameter monitoring [51,52]. Crucially, the platform enables continuous, remote monitoring of outpatient populations, aligning with the growing demand for wearable and smart bandage technologies in wound management [53]. This multi-parametric strategy is vital for expanding the diagnostic window available to clinicians, as it captures the dynamic, multi-factorial nature of the complex healing process, which is influenced by numerous systemic and local factors [36]. From a clinical perspective, the integration of multiple parameters directly within a pathologically altered area substantially enhances diagnostic accuracy [54]. This is of paramount relevance in complex patient groups, such as those with comorbidities like diabetes mellitus or among elderly individuals, where the innate healing cascade is often significantly altered or delayed [55,56]. For instance, elevated IL-6, particularly when combined with CRP and localized pH changes, serves as a highly specific indicator of subclinical inflammation and potential surgical site infection (SSI) progression in high-risk cohorts [55,57]. Without the benefit of such appropriate, sensitive diagnostic tools, these specific patients face a greater risk of silent infection progression, which can escalate to severe clinical complications, resulting in prolonged hospital stays and imposing substantial financial burdens on the healthcare system [58,59].

Bu et al. established a critical distinction by highlighting that core body temperature measurements are fundamentally insufficient for the early and accurate prediction of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs), thereby underscoring the imperative need to functionally separate systemic thermal monitoring from dedicated local wound surveillance [60,61,62]. The primary complication stems from routine perioperative warming practices, such as active patient “re-warming,” which are known to effectively mask subtle, localized temperature gradients that are essential diagnostic indicators of incipient infection [61,63]. This systemic interference significantly reduces the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting local inflammatory thermal changes [61]. These observations provide a strong rationale for two key developments: the necessity of integrating dedicated, wound-focused thermal sensors, such as those utilized in advanced wearable devices or localized infrared thermography, to provide high-resolution data directly from the site of interest [8,64] and the crucial need for future clinical study designs to meticulously control for and report the extent of systemic thermoregulatory interventions, ensuring that the diagnostic efficacy of local thermal sensing is accurately assessed [60,63]. The use of localized thermal sensing, supported by recent systematic reviews, offers a non-invasive, cost-effective adjunct to traditional methods for the early identification of inflammatory processes specifically in the surgical wound environment [8]. Furthermore, multiple studies underscore the practical importance of accounting for these thermoregulatory practices, which can obscure the delicate local temperature differences indicative of early pathology. Rezaei et al. specifically emphasize that the extensive diversity of patient risk factors—including advanced age (>65 years), immunosuppression, obesity, diabetes, prolonged operative duration, and the presence of implants profoundly modifies the expected healing process and alters the relevant wound temperature cutoff values [5]. This necessitates patient- or risk-group-specific calibration, which is critical when setting reliable alarm thresholds in continuous monitoring systems [5]. Encouragingly, several recent technological advances have now rendered these complex monitoring principles actionable at scale: the development of stretchable, printed “smart dressings” and flexible hydrogel-based temperature sensors permits continuous, localized measurements without the need for frequent, disruptive dressing changes [65,66,67]. Crucially, these systems often integrate pH and moisture sensors and, in advanced prototypes, even on-demand local drug release, enabling a multimodal diagnostic readout directly at the wound site [64,66]. While many of these innovative solutions are still at the prototype or early clinical-evaluation stages, consistent early clinical and preclinical reports suggest a tangible improvement in the accurate detection of aberrant healing trajectories when a multimodal, continuous monitoring paradigm is rigorously applied [64,65,66,67].

Power et al. underscored a critical methodological issue by highlighting meaningful discrepancies between localized point measurements and comprehensive imaging thermography, thereby stressing that the choice of thermal assessment method can significantly shape the clinical interpretation of postoperative wounds [68,69]. These discrepancies are further compounded by a lack of standardized imaging protocols. Recent evidence suggests that establishing strict environmental controls, patient acclimatization times, and camera calibration procedures is essential to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of thermal data [70,71]. The generally accepted physiological pattern of normal healing involves an initial, early temperature increase during the first postoperative days, followed by a gradual return to baseline values within approximately two weeks, any sudden deviations or sustained hyperthermia beyond this period may robustly indicate the onset of infection [68,72]. Furthermore, the challenge of interpretation is being addressed by the integration of artificial intelligence. Deep learning models are now being trained to automatically detect subtle patterns in thermal imagery associated with infection, potentially reducing observer bias and improving the diagnostic accuracy of thermography for postoperative monitoring [72]. Building upon this time-dependent understanding, Huang et al. compellingly indicate that the analysis of wound temperature change trajectories and the assessment of relative temperature differences (ΔT) possess a greater diagnostic and prognostic value than any single static measurement [15]. This is because trajectories more accurately reflect dynamic underlying alterations in local perfusion, cellular recruitment, and bacterial metabolic activity. Specifically in their analysis, abnormal deviations from the expected gradual cooling pattern after Day 7–14 of healing were identified as particularly informative for early infection signaling [15]. In a related manner, Fridberg et al. further refined these observations by describing distinct thermal patterns: they confirmed that normal postoperative hyperthermia typically persists for 7−14 days, and a sudden, sharp temperature spike occurring after a period of initial thermal stability should immediately raise the clinical suspicion of infection [8]. Their findings emphasize that a detailed analysis of trajectory deviations provides a critical opportunity for early, targeted intervention well before the full development of overt clinical symptoms [8]. Taken together, these consistent observations provide strong support for continuous or repeated monitoring over a period of time, emphasizing the necessity of tracking change rather than simply thresholding a single absolute value, which is essential to reliably distinguish expected normal postoperative inflammation from the insidious onset of an incipient Surgical Site Infection (SSI).

From a crucial prognostic perspective, the research by Liu et al. compellingly demonstrated that the continuous monitoring of relative temperature differences (ΔT) between the surgical or chronic wound site and established control points is not only prognostically useful but also serves as a direct indicator reflecting the efficacy of underlying vascular reconstruction [73]. Notably, within high-risk patient cohorts such as those with diabetic foot ulcers, a smaller ΔT observed between the compromised wound area and the contralateral intact skin is a strong thermal signature that predicts better healing potential and more favorable outcomes. Conversely, consistent or progressive ΔT increases above 2−3 °C frequently and robustly coincide with the onset of infection or indicate excessive, non-resolving inflammation [73]. Complementing this diagnostic utility, Chanmugam et al. advocated for a refined clinical approach by suggesting the implementation of multi-level alarm thresholds based on thermal data [74]. This proposed system could utilize thresholds such as ΔT > 1 °C for an initial warning signal requiring increased surveillance, and a higher threshold of ΔT > 3−4 °C combined with elevated systemic biomarkers like C-Reactive Protein (CRP) or more specific and rapidly responding markers such as Procalcitonin (PCT) or local pH changes for a critical, actionable alert [74,75]. Evidence suggests that PCT may rise earlier and with greater specificity for bacterial infection than CRP, making it a promising candidate for integration into multi-parameter early warning systems [76,77]. Recent conceptual advances propose moving beyond static thresholds towards personalized, dynamic risk scores. These models integrate baseline patient characteristics with continuous thermal data and other biomarkers to generate a real-time, patient-specific risk of complication, potentially offering greater accuracy than a one-size-fits-all ΔT value [78]. This hierarchical approach is designed to minimize unnecessary clinical interventions stemming from transient thermal fluctuations and instead focuses scarce clinical attention and resources on patients identified to be at the highest and most immediate risk of complication. This methodology directly aligns with the mounting body of evidence confirming that combining objective local temperature measurements with other relevant physiological or biochemical biomarkers substantially enhances diagnostic specificity and improves the overall clinical management pathway [74,79].

In terms of clinical decision support, Bhavani et al. showed that longitudinal body-temperature trajectories in infection and sepsis encode prognostic information independent of single readings: hypothermic trajectories were associated with higher mortality, whereas febrile responses correlated with improved survival. Although their work centered on systemic illness, the conceptual takeaway—trajectories capture biologic heterogeneity and can reveal treatment-responsive subphenotypes—translates to wound monitoring, where trajectory deviations may identify patients who benefit from early diagnostics or targeted therapy [20,80]. The methodology for identifying these subphenotypes is also advancing; unsupervised machine learning techniques can now objectively deconstruct longitudinal physiological data, such as wound temperature trajectories, to uncover distinct clusters of patients with divergent clinical outcomes, moving beyond pre-defined thresholds to data-driven discovery [81].

In the realm of clinical decision support, the foundational work by Bhavani et al. definitively showed that longitudinal body-temperature trajectories—tracked over time in patients battling systemic infection and sepsis-encode prognostic information that is independent of any single, isolated temperature reading [81]. Specifically, they demonstrated that hypothermic trajectories were strongly associated with a higher mortality risk, whereas robust febrile responses correlated positively with improved survival outcomes [81]. Although their study primarily centered on systemic illness, the conceptual takeaway—that trajectories capture crucial biologic heterogeneity and can effectively reveal treatment-responsive subphenotypes—is highly translatable to local wound monitoring. In this local context, trajectory deviations in wound temperature can serve as an early, objective signal to identify patients who would most benefit from immediate diagnostics or highly targeted therapeutic interventions [81]. Furthermore, the most prognostically powerful approach may involve integrating both local wound trajectories and systemic core temperature trajectories, as the dynamic relationship between the two can provide a more comprehensive picture of the host’s inflammatory and immune response [82]. Directly supporting this application, in the context of leveraging wound temperature trends, dedicated monitoring systems such as SteadyTemp® provide continuous, non-invasive core body temperature monitoring. When this core data is combined with readings from local wound temperature sensors, these integrated systems offer a powerful mechanism to support the early detection of infection and subsequently optimize timely clinical decision-making [13].

The accumulated body of evidence robustly indicates that the continuous analysis of postoperative wound temperature can significantly aid in the early and proactive detection of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs); however, its ultimate diagnostic value is critically contingent upon the proper, nuanced interpretation of the obtained thermal signals [83,84,85]. Crucial diagnostic importance therefore lies not merely in the absolute temperature level recorded at any single point in time, but, above all, in assessing the dynamics of temperature changes over time, analyzing the differences relative to the surrounding healthy skin (ΔT), and detecting sudden, sustained deviations from the expected physiological healing trajectory [40,83]. The integration of these core thermal data with other complementary biochemical parameters, specifically local pH or systemic inflammatory markers, has been shown to synergistically enhance both the sensitivity and specificity of the monitoring method, moving it beyond a mere warning signal toward a definitive diagnostic tool [64,84].

In summary, the dynamic analysis of wound temperature, especially when synergistically combined with other relevant biological parameters, represents an exceedingly promising and robust tool for the accurate diagnosis, continuous surveillance, and effective monitoring of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs). The validation of this approach is now being demonstrated through first-in-human studies of smart wound dressings that enable continuous, simultaneous monitoring of temperature and pH, providing a tangible pathway to clinical translation [85,86]. The trajectory of future postoperative wound monitoring critically hinges upon achieving widespread standardization of measurement protocols, facilitating intelligent integration of diverse data streams, and driving multi-parameter innovation. For instance, research now shows that fusing thermal imaging data with other data sources, such as computerized visual wound assessment, within a machine learning framework can significantly outperform single-modality assessments [87]. Establishing rigorous, consensus-based clinical guidelines and systematically validating these across diverse patient demographics and surgical groups will be crucial for significantly improving reliability and generalizability. Concurrently, the seamless integration of continuous monitoring data into Electronic Health Records (EHR) is essential to enable features such as automated alerts, robust longitudinal tracking, and sophisticated predictive analytics [67,84]. Crucially, recent studies have begun to develop and validate the specific predictive models needed for this integration, creating AI algorithms trained on continuous vital signs to forecast SSI risk before it is clinically obvious, thereby demonstrating the feasibility of this vision [88]. Furthermore, anticipated advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are expected to fundamentally support highly refined early infection prediction, the calculation of personalized diagnostic thresholds, and the optimization of intervention timing based on complex pattern recognition. Finally, expanding the accessibility of wearable, wireless monitoring systems to the outpatient and home care settings will dramatically enhance follow-up capabilities for high-risk patients. Crucially, the incorporation of additional physiological and biochemical parameters such as pH, bioimpedance, specific biochemical markers, and advanced optical imaging will further augment diagnostic accuracy while simultaneously maintaining a highly desirable non-invasive, continuous monitoring paradigm.

Limitations

This review is subject to certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Although only a small number of studies met the inclusion criteria and individual sample sizes were modest, we believe that the included evidence collectively provides a coherent overview of current knowledge on postoperative thermal monitoring. While a structured and comprehensive search strategy was employed, the narrative review design inherently carries some risk of selection or interpretation bias. Additionally, all included studies used similar infrared thermography systems and broadly comparable measurement protocols; although this consistency strengthens internal comparability, it may limit extrapolation to other emerging monitoring technologies. The surgical populations were also relatively homogeneous, with the majority of procedures involving abdominal incisions, which may reduce generalizability to other surgical sites or specialties. These considerations underscore the need for further well-designed, preferably multicenter research to refine diagnostic thresholds, validate these findings, and support broader clinical implementation.

5. Conclusions

Continuous monitoring of local wound temperature emerges as a powerful tool for identifying early deviations from expected healing trajectories, offering a level of temporal resolution that precedes the onset of overt clinical symptoms. The evidence synthesized in this review demonstrates that dynamic indicators such as wound-to-adjacent skin temperature differences (ΔT), thermal asymmetry, and departures from the expected postoperative trajectory possess greater diagnostic value than isolated temperature measurements. When these metrics are interpreted in conjunction with inflammatory biomarkers or complementary physiological signals, their specificity improves markedly, reducing the likelihood of false alarms attributable to normal postoperative inflammation. At the same time, the reliability of thermal data depends critically on methodological consistency, standardized measurement protocols and careful consideration of confounding factors including environmental conditions, thermoregulatory practices, and patient comorbidities.

Looking forward, the emergence of smart dressings and integrated multiparametric platforms represents a transformative direction for postoperative surveillance, enabling continuous and personalized assessment of wound physiology. These technologies, when combined with advanced analytical methods, offer the potential for earlier and more targeted intervention, particularly in high-risk patient populations. Of equal importance is the rapid development of artificial intelligence techniques capable of recognizing complex thermal patterns and modeling temperature trajectories with far greater nuance than is possible through manual interpretation alone. Incorporating AI-driven analysis into wound monitoring systems may ultimately support the creation of individualized diagnostic thresholds, automated alerts, and predictive models that anticipate infection before it becomes clinically apparent. Realizing this potential will require rigorous validation across diverse surgical populations, but the convergence of continuous sensing, standardized protocols, and intelligent analytics signals a promising pathway toward more proactive, precise, and patient-centered postoperative care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.F., B.P., A.J., S.K., E.M.K. and J.M.; methodology, T.F., A.J., J.M. and E.M.K.; software, T.F., A.J., B.P. and S.K.; validation, T.F., J.M., B.P. and A.J.; formal analysis, T.F., A.J., J.M., E.M.K. and B.P.; investigation, T.F., E.M.K. and S.K.; resources, T.F., B.P. and J.M.; data curation, T.F., A.J., E.M.K., S.K. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F., J.M., S.K., A.J., E.M.K. and B.P.; writing—review and editing, J.M., T.F. and B.P.; visualization, A.J., T.F. and S.K.; supervision, B.P., T.F. and J.M.; project administration, T.F., B.P. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSI | Surgical site infections |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IR | Infrared |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| LWIT | Long wave infrared thermography |

| WATD | Wound abdominal temperature difference |

| LWIR | Long wave infrared |

References

- Derwin, R.; Patton, D.; Strapp, H.; Moore, Z. The effect of inflammation management on pH, temperature, and bacterial burden. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, D.A.; Alemu, A.; Abdukadir, A.A.; Mohammed Husen, A.; Ahmed, F.; Mohammed, B.; Musa, I. Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Among Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Inquiry 2023, 60, 469580231162549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Cai, Y. Meta-analysis of efficacy of perioperative oral antibiotics in intestinal surgery with surgical site infection. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 35, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidelman, J.; Anderson, D.J. Surgical Site Infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 901–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.R.; Zienkiewicz, D.; Rezaei, A.R. Surgical site infections: A comprehensive review. J. Trauma Inj. 2025, 38, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.I.G.; Cockram, C.S.; Ma, R.C.W.; Luk, A.O.Y. Diabetes and infection: Review of the epidemiology, mechanisms and principles of treatment. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Pugliese, G.; Laudisio, D.; Castellucci, B.; Barrea, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. The impact of obesity on immune response to infection: Plausible mechanisms and outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridberg, M.; Bafor, A.; Iobst, C.A.; Laugesen, B.; Jepsen, J.F.; Rahbek, O.; Kold, S. The role of thermography in assessment of wounds. A scoping review. Injury 2024, 55, 111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.R.; O’Connor, G.M.; Ryan, D.A.; Parmeter, M.; Dinneen, S.; Gethin, G. Wound Bed Temperature has Potential to Indicate Infection Status: A Cross-Sectional Study. Wound Repair Regen. 2025, 33, e70072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.F.; Wang, Z.C.; Xue, Y.N.; Zhao, W.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Hu, Y.Y.; Fang, Q.Q.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.Z.; et al. The importance of temperature monitoring in predicting wound healing. J. Wound Care 2023, 32, lxxxvii–xcvi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridberg, M.; Rahbek, O.; Husum, H.C.; Anirejuoritse, B.; Duch, K.; Iobst, C.; Kold, S. Can pin-site inflammation be detected with thermographic imaging? A cross-sectional study from the USA and Denmark of patients treated with external fixators. Acta Orthop. 2024, 95, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, D.; Ludwig, N.; Rossi, A.; Trecroci, A.; Alberti, G.; Gargano, M.; Merla, A.; Ammer, K.; Caumo, A. Is the maximum value in the region of interest a reliable indicator of skin temperature? Infrared Phys. Technol. 2018, 94, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, T.; Zeng, D.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Guo, J.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.J.; et al. Integrated Multiplex Sensing Bandage for In Situ Monitoring of Early Infected Wounds. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 3112–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodes-Carbonell, A.M.; Torregrosa-Valls, J.; Guill Ibáñez, A.; Tormos Ferrando, A.; Juan Blanco, M.A.; Ferriols, A.C. Flexible Hybrid Electrodes for Continuous Measurement of the Local Temperature in Long-Term Wounds. Sensors 2021, 21, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fan, C.; Ma, Y.; Huang, G. Exploring Thermal Dynamics in Wound Healing: The Impact of Temperature and Microenvironment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, B.; Huang, R.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X. Flexible integrated sensing platform for monitoring wound temperature and predicting infection. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 1566–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.R.; Ng, N.; Tsanas, A.; Mclean, K.; Pagliari, C.; Harrison, E.M. Mobile devices and wearable technology for measuring patient outcomes after surgery: A systematic review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenen, J.P.L.; Ardesch, V.; Kalkman, C.J.; Schoonhoven, L.; Patijn, G.A. Impact of wearable wireless continuous vital sign monitoring in abdominal surgical patients: Before-after study. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrad128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignami, E.G.; Panizzi, M.; Bezzi, F.; Mion, M.; Bagnoli, M.; Bellini, V. Wearable devices as part of postoperative early warning score systems: A scoping review. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2025, 39, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, J.; Rochon, M.; Harris, R.; Beckhelling, J.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Mason, L.; Bouttell, J.; Bolton, S.; Dummer, J.; Wilson, K.; et al. Digital wound monitoring with artificial intelligence to prioritise surgical wounds in cardiac surgery patients for priority or standard review: Protocol for a randomised feasibility trial (WISDOM). BMJ Open 2024, 14, e086486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baniasadi, T.; Hassaniazad, M.; Rostam Niakan Kalhori, S.; Shahi, M.; Ghazisaeedi, M. Developing a mobile health application for wound telemonitoring: A pilot study on abdominal surgeries post-discharge care. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mahajan, A.; Powell, D. Advancing perioperative care with digital applications and wearables. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, T.; Modestini, C.; Mizzi, A.; Falzon, O.; Cassar, K.; Mizzi, S. The Effects of Skin Temperature Changes on the Integrity of Skin Tissue: A Systematic Review. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2022, 35, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorg, H.; Sorg, C.G.G. Skin Wound Healing: Of Players, Patterns, and Processes. Eur. Surg. Res. 2023, 64, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Guarino, M.; Naharro-Rodriguez, J.; Bacci, S. Aberrances of the Wound Healing Process: A Review. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, K.; Okuno, T.; Yokomizo, T. Eicosanoids in Skin Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, H.; Guo, Z.; Chang, Y.; Li, Z. Role of prostaglandin E2 in tissue repair and regeneration. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8836–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.-H.; Samandari, M.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Song, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tamayol, A.; Wang, X. Multimodal Sensing and Therapeutic Systems for Wound Healing and Management: A Review. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2022, 4, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.; Pang, Q.; Pei, X.; Dong, S.; Li, S.; Tan, W.Q.; Ma, L. Flexible wound healing system for pro-regeneration, temperature monitoring and infection early warning. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 162, 112275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Shao, C.; Geng, P.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J. Recent advances in molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing and its treatments. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1395479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Dorantes, L.; Cañedo-Ayala, M. Skin Acute Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Inflam. 2019, 2019, 3706315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guarino, M.; Hernández-Bule, M.L.; Bacci, S. Cellular and Molecular Processes in Wound Healing. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, D.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Ma, W.; Tan, Y.; Gygi, S.P.; Higgins, D.E.; Kagan, J.C. Molecular definition of the endogenous Toll-like receptor signalling pathways. Nature 2024, 631, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Infection, Inflammation, and Immunity in Sepsis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wautier, J.L.; Wautier, M.P. Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Prostaglandins and Cytokines in Humans: A Mini Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Rush, B.; Boyd, J. Pathophysiology of Septic Shock. Crit. Care Clin. 2018, 34, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlow, J.; Bowler, P.G. Acute and chronic wound infections: Microbiological, immunological, clinical and therapeutic distinctions. J. Wound Care 2022, 31, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegadło, K.; Gieroń, M.; Żarnowiec, P.; Durlik-Popińska, K.; Kręcisz, B.; Kaca, W.; Czerwonka, G. Bacterial Motility and Its Role in Skin and Wound Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Su, R.; Han, F.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Q.; Zhai, X.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; et al. A soft intelligent dressing with pH and temperature sensors for early detection of wound infection. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3243–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-GarciaLuna, J.L.; Bartlett, R.; Arriaga-Caballero, J.E.; Fraser, R.D.J.; Saiko, G. Infrared Thermography in Wound Care, Surgery, and Sports Medicine: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 838528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siah, C.J.; Childs, C. Thermographic mapping of the abdomen in healthy subjects and patients after enterostoma. J. Wound Care 2015, 24, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwin, R.; Patton, D.; Strapp, H.; Moore, Z. Wound pH and temperature as predictors of healing: An observational study. J. Wound Care 2023, 32, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.B.; Christensen, L.; Zafar, S.N. How to perform an effective literature review. Am. J. Surg. 2022, 224, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, C.R.; Childs, C.; Chia, C.K.; Cheng, K.F.K. An observational study of temperature and thermal images of surgical wounds for detecting delayed wound healing within four days after surgery. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, C.; Wright, N.; Willmott, J.; Davies, M.; Kilner, K.; Ousey, K.; Soltani, H.; Madhuvrata, P.; Stephenson, J. The surgical wound in infrared: Thermographic profiles and early stage test-accuracy to predict surgical site infection in obese women during the first 30 days after caesarean section. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, C.; Siraj, M.R.; Fair, F.J.; Selvan, A.N.; Soltani, H.; Wilmott, J.; Farrell, T. Thermal territories of the abdomen after caesarean section birth: Infrared thermography and analysis. J. Wound Care 2016, 25, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benvenisti, H.; Cohen, O.; Feldman, E.; Assaf, D.; Jacob, M.; Bluestein, E.; Strechman, G.; Orkin, B.; Nachman-Farchy, H.; Nissan, A. The Thermal Signature of Wound Healing. J. Surg. Res. 2024, 303, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, N.; Gargano, M.; Formenti, D.; Bruno, D.; Ongaro, L.; Alberti, G. Breathing training characterization by thermal imaging: A case study. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2012, 14, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fang, Z.; Wei, D.; Liu, Y. Flexible Pressure, Humidity, and Temperature Sensors for Human Health Monitoring. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2401532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, J.; Holm, M.; Janson, M.; Egenvall, M.; van der Linden, J. Relation of intraoperative temperature to postoperative mortality in open colon surgery--an analysis of two randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2016, 31, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnaboina, V. Recent Advancements in Smart Bandages for Wound Healing. J. Sens. Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Ershad, F.; Zhao, M.; Isseroff, R.R.; Duan, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C. Wearable electronics for skin wound monitoring and healing. Soft Sci. 2022, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Li, L.; Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Luo, D.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Song, X.; Zhou, X. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 127, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fan, S.; Sun, J. Delayed Wound Healing in the Elderly and a New Therapeutic Target: CD271. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 19, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, P.J.; Ecker, C.; Jäckle, K.; Meier, M.P.; Reinhold, M.; Klockner, F.S.; Lehmann, W.; Weiser, L. Interleukin-6 as a critical inflammatory marker for early diagnosis of surgical site infection after spine surgery. Infection 2024, 52, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound healing: Cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciuttolo, M.G.; Specchia, M.L.; Bonacquisti, M.; Russo, L.; Murri, R.; Fantoni, M.; Di Donato, M.; Raponi, M.; La Greca, A.; Sganga, G.; et al. Economic Impact of Surgical Site Infections Prevention across Surgical Units at Gemelli University Hospital: Insights from a Point Prevalence Survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 2025, 167, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, P.; Dincler, S.; Buchmann, P. A multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for intra- and postoperative complications in 1316 elective laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]