Production of Lactic Acid Wort-Based Beverages with Rosehip, Lemongrass, and Eucalyptus Oils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials, Media, and Reagents

2.1.1. Raw Materials

2.1.2. Media

2.1.3. Reagents

2.2. Wort Production

2.3. Fermentation

2.4. Analytical Procedures

2.4.1. Fermentation Parameters

2.4.2. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity of the Beverages Produced

2.4.3. Sensory Analysis

2.4.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Oil Additions on the Fermentation Parameters

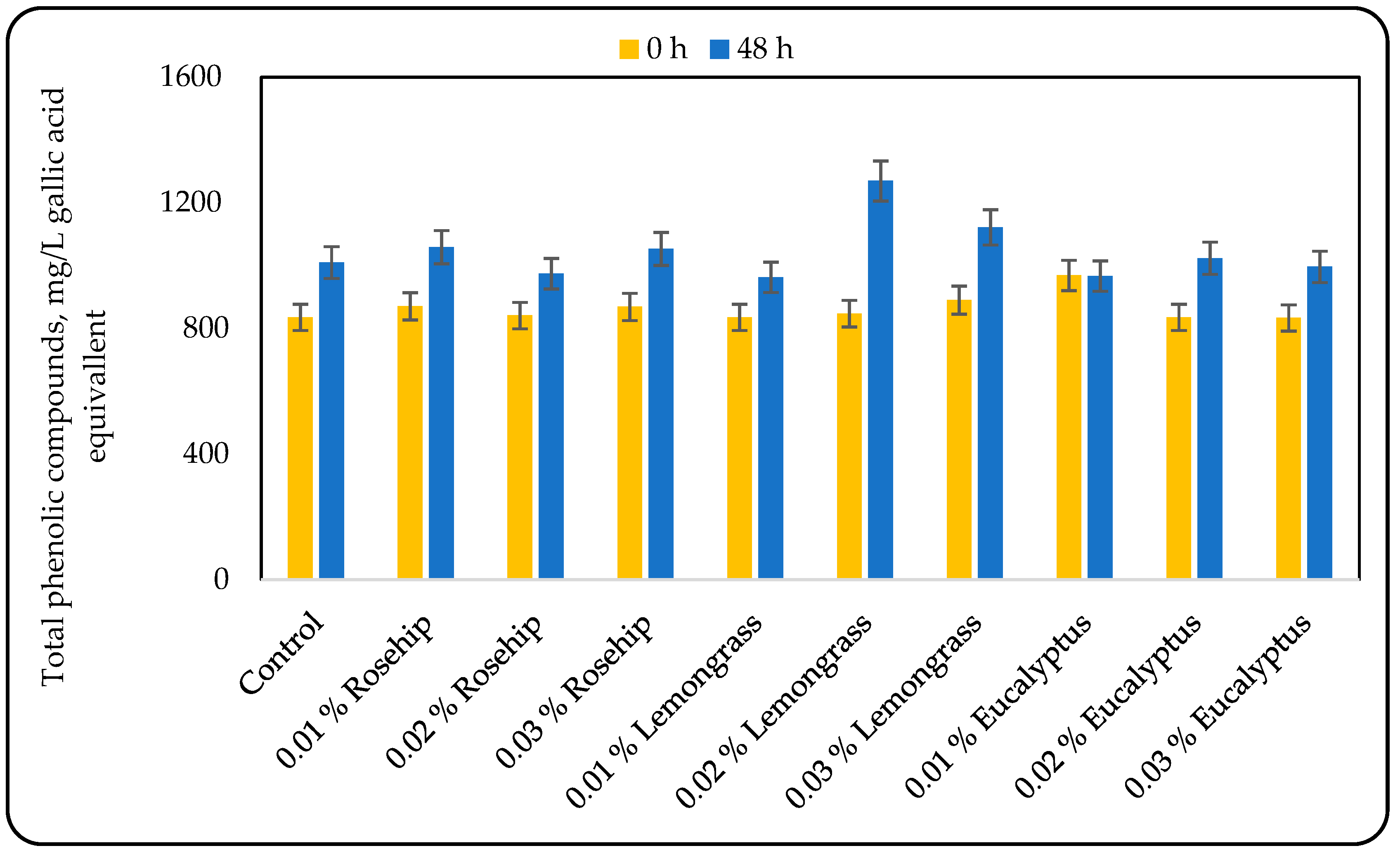

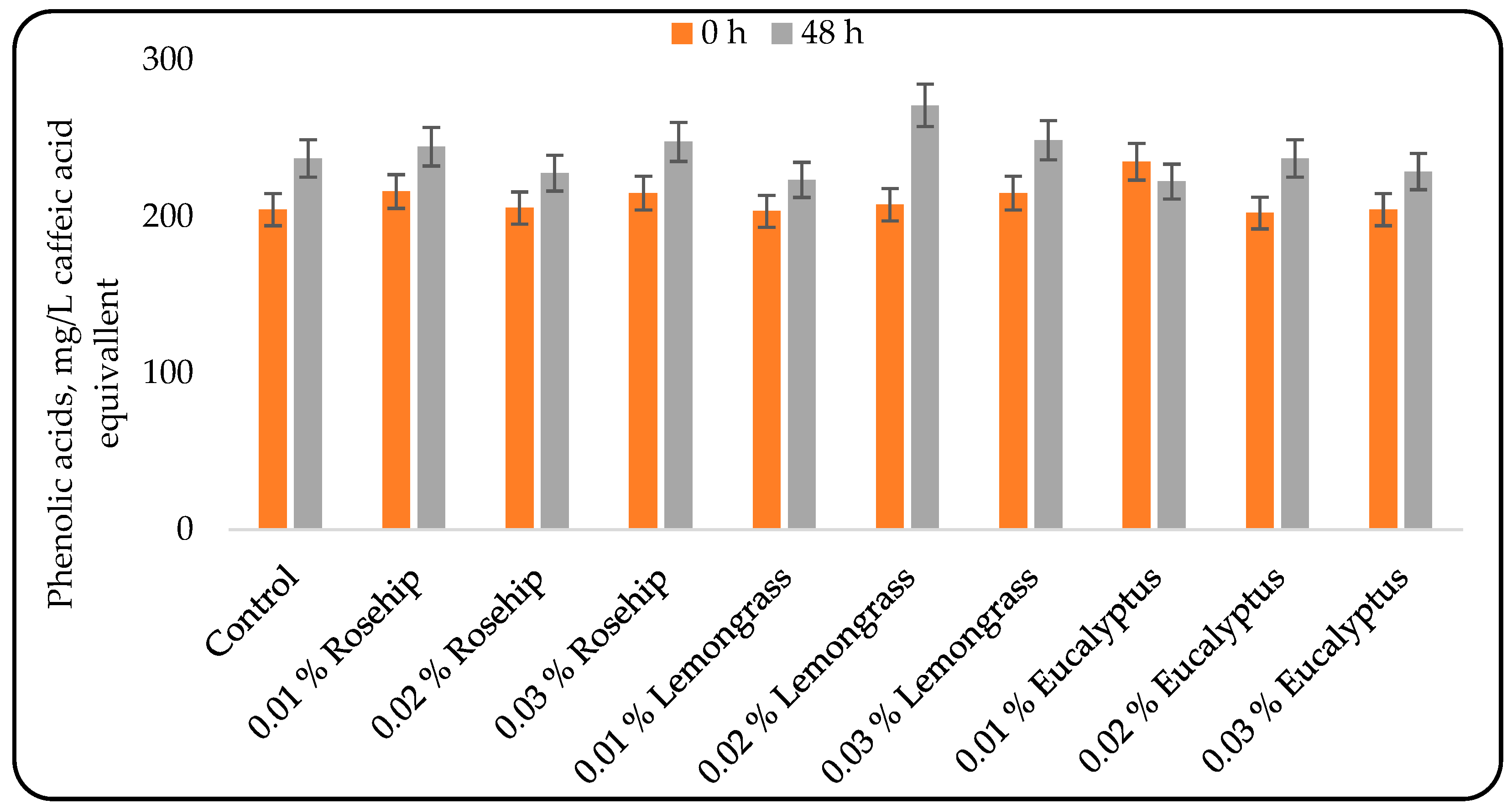

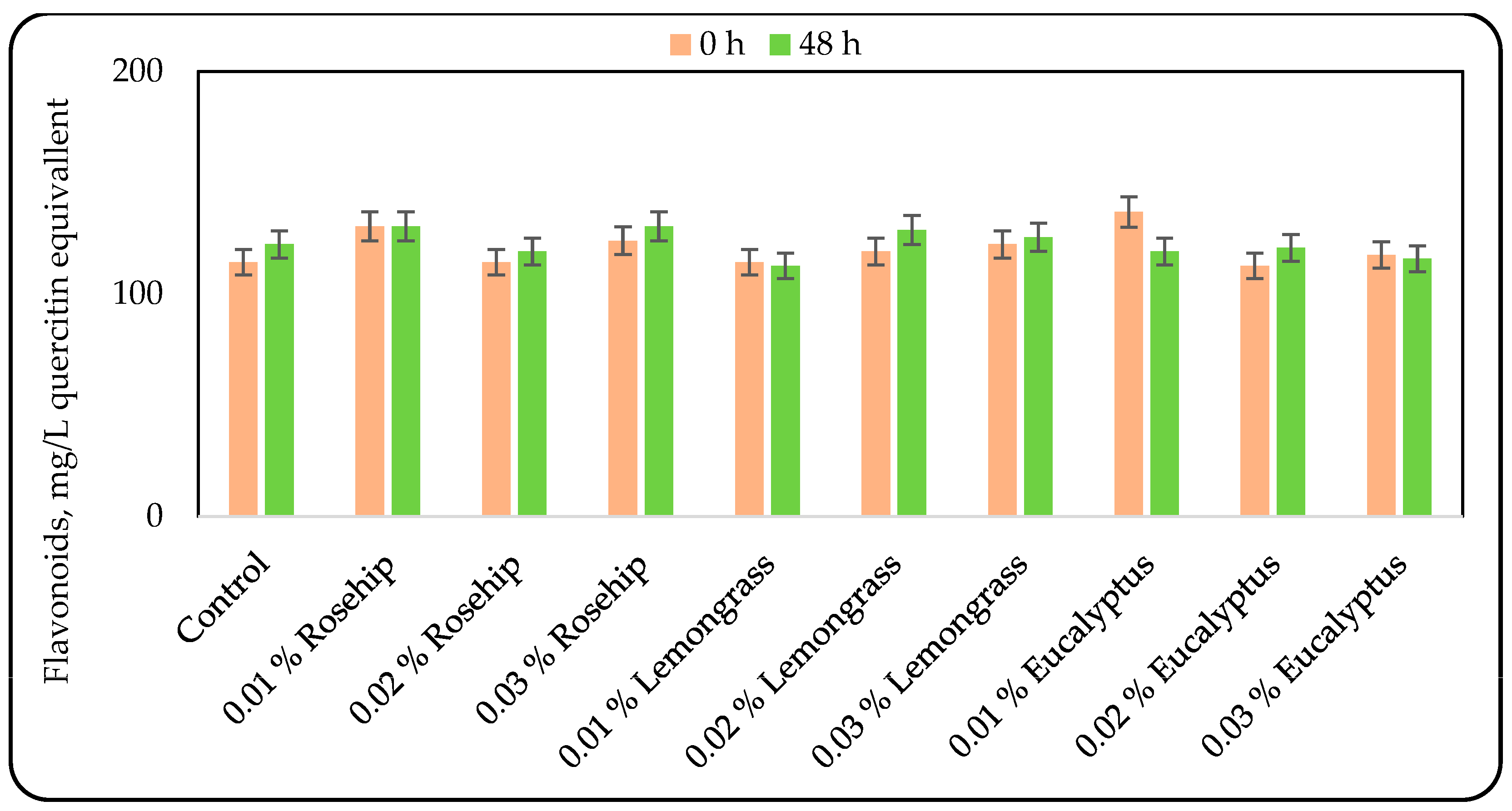

3.2. Effect of Oil Addition on the Phenolic Compounds Content

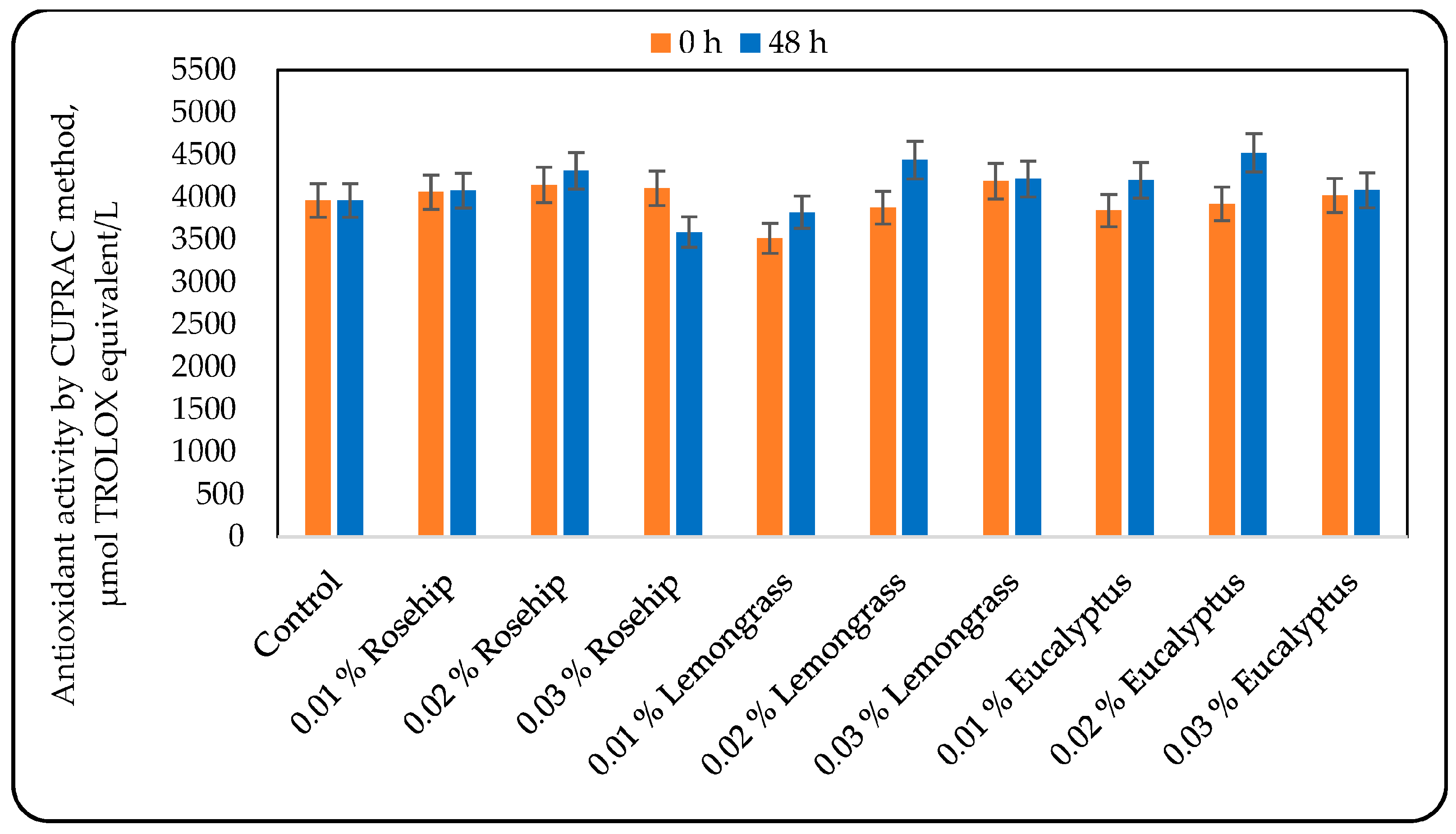

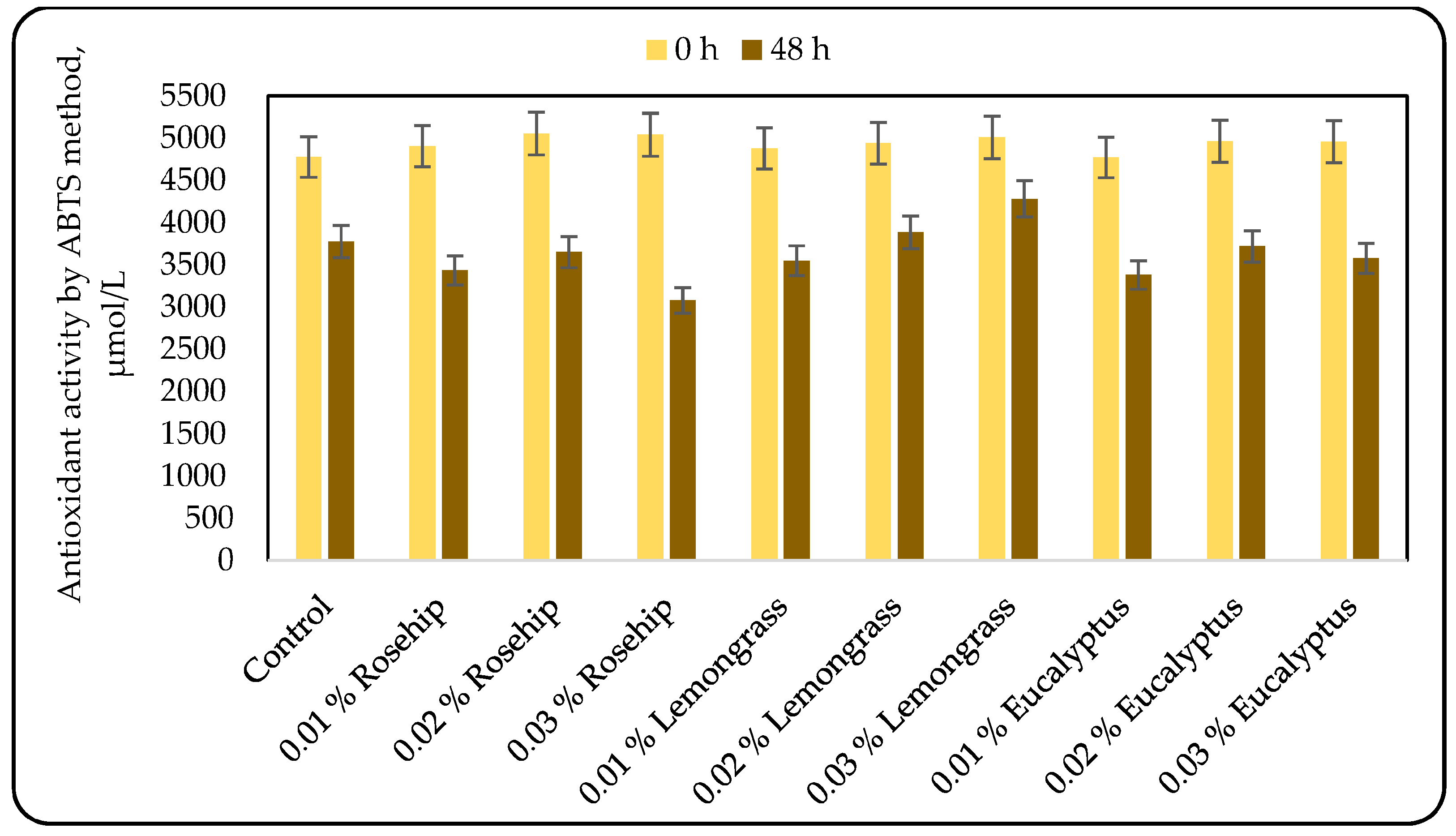

3.3. Effect of the Oil Addition on the Antioxidant Activity (AOA)

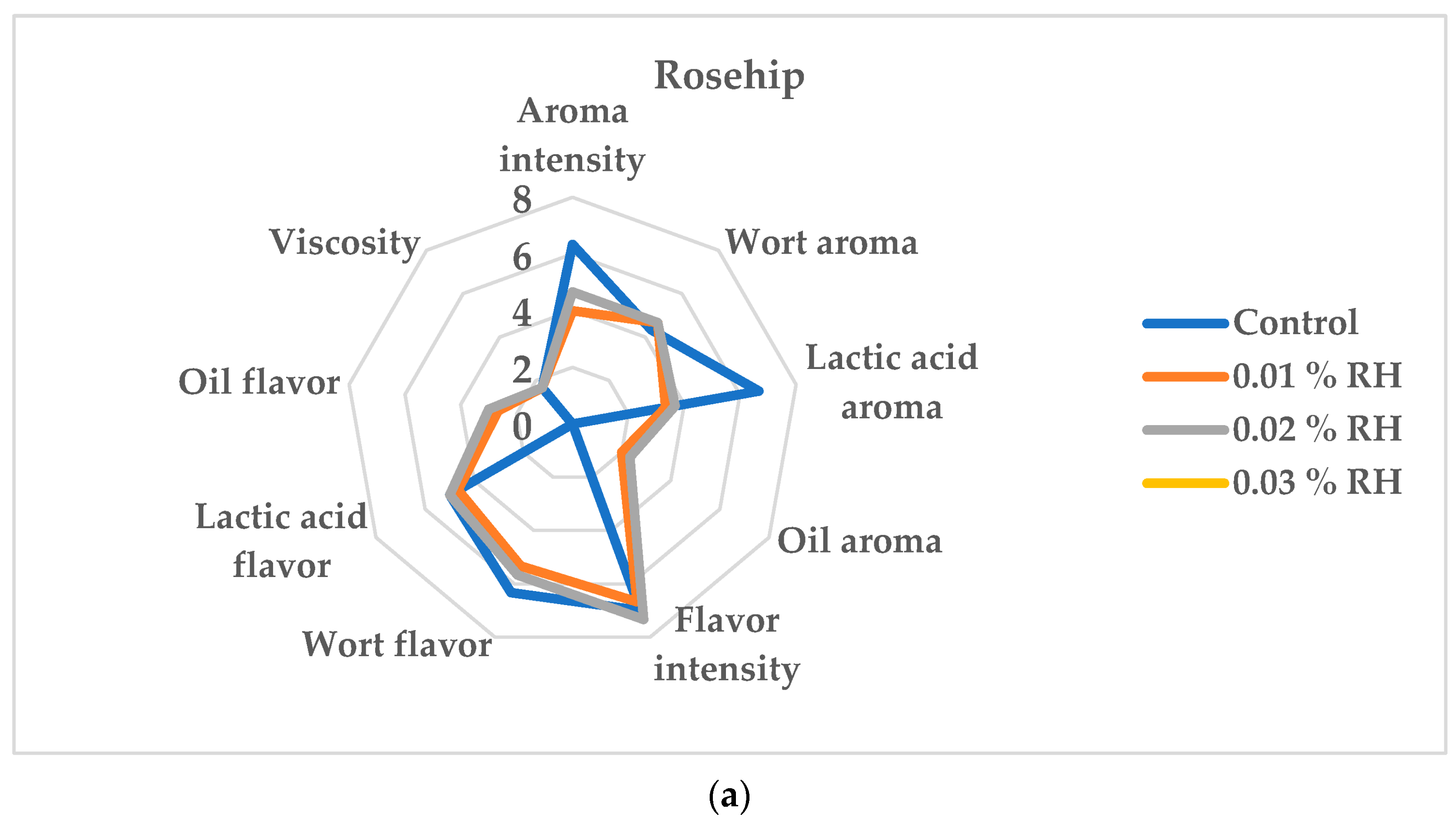

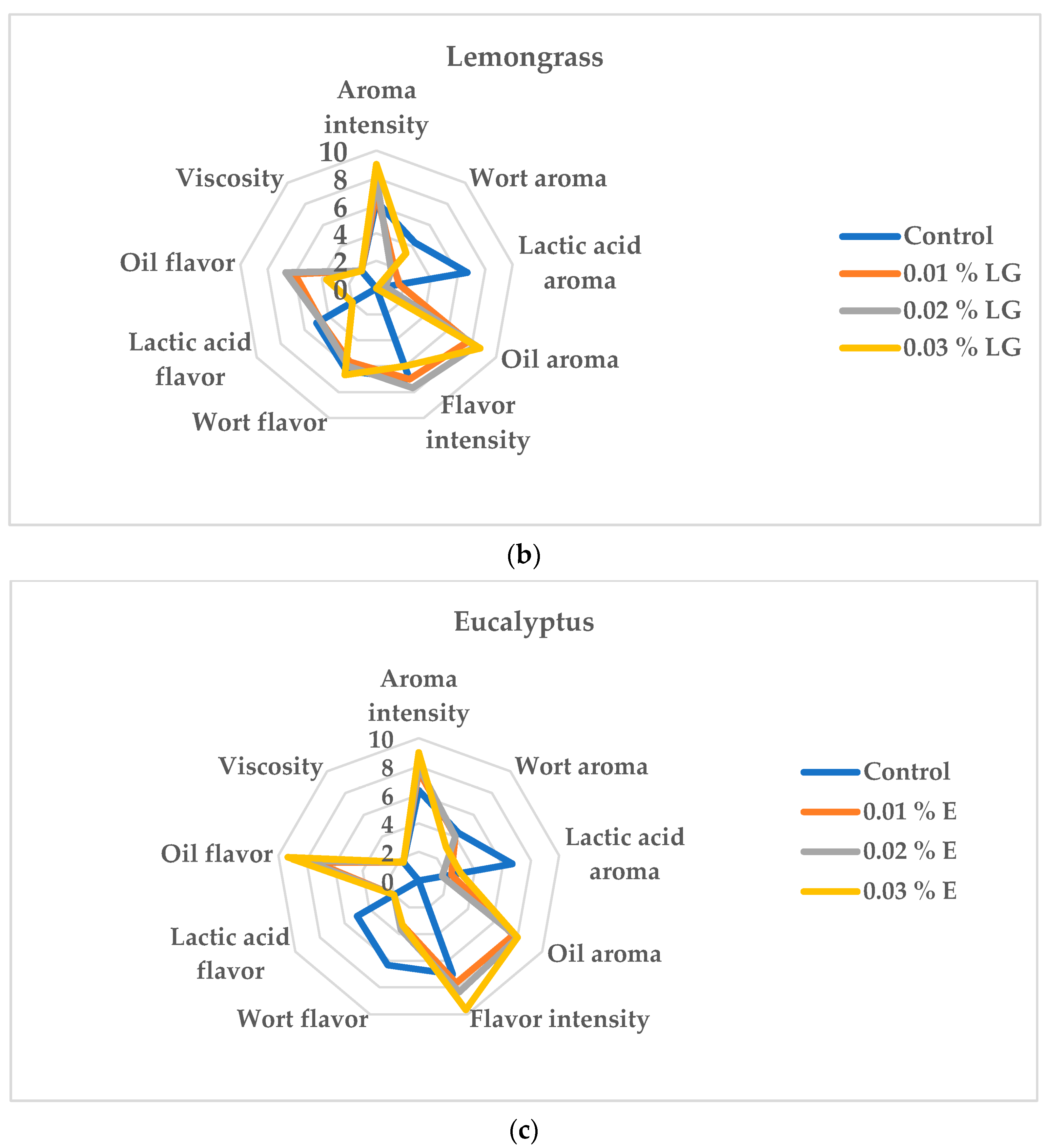

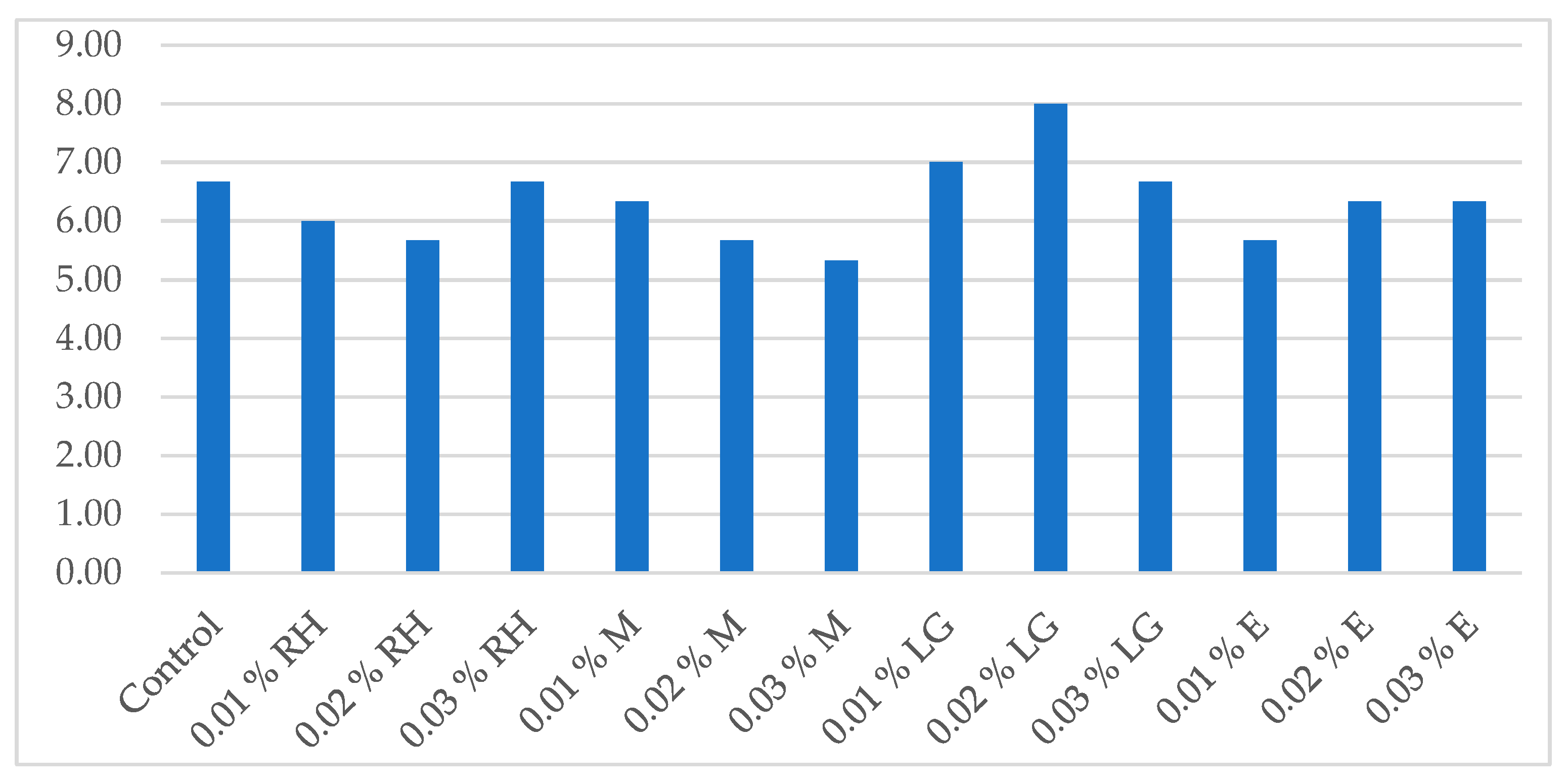

3.4. Effect of Oil Addition on the Sensory Evaluation of the Beverages Produced

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, A.; Sarabi-Aghdam, V.; Fathi, M.; Abbaszadeh, S. Non-Dairy Fermented Probiotic Beverages: A Critical Review on the Production Techniques, Health Benefits, Safety Considerations and Market Trends. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 28, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarno, M.; Cichońska, P. Lactic Acid Bacteria-Fermentable Cereal- and Pseudocereal-Based Beverages. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharousi, Z.S. Highlighting Lactic Acid Bacteria in Beverages: Diversity, Fermentation, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, M.; Goranov, B.; Shopska, V.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Lyubenova, V.; Kostov, G. Production of lactic acid wort-based beverages with mint essential oil addition. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Prot. 2021, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiej-Kozioł, D.; Momot-Ruppert, M.; Stawicka, B.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A. Health Benefits, Antioxidant Activity, and Sensory Attributes of Selected Cold-Pressed Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukvicki, D.; D’Alessandro, M.; Rossi, S.; Siroli, L.; Gottardi, D.; Braschi, G.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R. Essential Oils and Their Combination with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacteriocins to Improve the Safety and Shelf Life of Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranov, B.; Dzhivoderova-Zarcheva, M.; Shopska, V.; Denkova Kostova, R.; Kostov, G. Effect of mint essential oil addition on lactic acid fermentation in stirred tank bioreactor. J. Int. Sci. Publ. Mater. Methods Technol. 2023, 17, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranov, B.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Shopska, V.; Kostov, G. Production of lactic acid wort-based beverage with raspberry seed oil addition under static and dynamic conditions. Bio Web Conf. 2024, 102, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiralan, M.; Yildirim, G. Rosehip (Rosa canina L.) Oil. In Fruit Oils: Chemistry and Functionality, 1st ed.; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 803–814. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyasoğlu, H. Characterization of Rosehip (Rosa canina L.) seed and seed Oil. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Górska, A.; Brzezińska, R.; Piasecka, I. Assessment of the nutritional potential and resistance to oxidation of sea buckthorn and rosehip oils. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibenda, J.J.; Yi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. Review of phytomedicine, phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacological activities of Cymbopogon genus. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 997918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Majewska, E.; Kozłowska, M.; Gruczyńska-Sękowska, E.; Kowalska, D.; Tarnowska, K. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil: Extraction, composition, bioactivity and uses for food preservation—A review. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, I.Y.; Perdana, M.I.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Csupor, D.; Takó, M. Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Kefi, S.; Tabben, O.; Ayed, A.; Jallouli, S.; Feres, N.; Hammami, M.; Khammassi, S.; Hrigua, I.; Nefisi, S.; et al. Variation in chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil under phenological stages and evidence synergism with antimicrobial standards. Int. Crop. Prod. 2018, 124, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, M.; Ezazi, R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil of Zhumeria majdae, Heracleum persicum and Eucalyptus sp. against some important phytopathogenic fungi. J. Mycol. Médicale 2017, 27, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Nikkhah, H.; Shahbazi, A.; Zarin, M.K.Z.; Iz, D.B.; Ebadi, M.-T.; Fakhroleslam, M.; Beykal, B. Cumin and eucalyptus essential oil standardization using fractional distillation: Data-driven optimization and techno-economic analysis. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 143, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedova, G.; Kaneva, M.; Denkova, R.; Teneva, D.; Denkova, Z.; Ignatov, I.; Nedyalkov, P. Dynamics of the fermentation process of a lactic acid beverage based on wort and mint with Lactobacillus casei ssp. rhamnosus Oly. Sci. Work. Univ. Food Technol. 2017, 67, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shopska, V.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Dzhivoderova-Zarcheva, M.; Teneva, D.; Denev, P.; Kostov, G. Comparative Study on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Different Malt Types. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Brewery Convention. Analytica—EBC; Fachverlag Hans Carl: Nürnberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nsogning, S.D.; Fischer, S.; Becker, T. Investigating on the fermentation behavior of six lactic acid bacteria strains in barley malt wort reveals limitation in key amino acids and buffer capacity. Food Microbiol. 2018, 73, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.; Petelkov, I.; Shopska, V.; Denkova, R.; Gochev, V.; Kostov, G. Investigation of mashing regimes for low-alcohol beer production. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pacheco, M.M.; Torres-Moreno, H.; Flores-Lopez, M.L.; Velázquez Guadarrama, N.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Ortega-Ramírez, L.A.; López-Romero, J.C. Mechanisms and Applications of Citral’s Antimicrobial Properties in Food Preservation and Pharmaceuticals Formulations. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagdi, C.; Bouaouda, K.; Rahhal, R.; Hsaine, M.; Badri, W.; Fougrach, H.; El Hajjouji, H. Phenolic compounds, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the methanolic extracts of Euphorbia resinifera and Euphorbia echinus. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, E.D.; Setiawan, N.C.E.; Christi, J.P. Effect of Lactic Acid Fermentation on Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Fig Fruit Juice (Ficus carica). In Proceedings of the 1st Health Science International Conference (HSIC 2017), Malang, Indonesia, 4–5 October 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, P.M.d.L.; Dantas, A.M.; Morais, A.R.d.S.; Gibbert, C.C.H.K.; Lima, M.d.S.; Magnani, M.; Borges, G.d.S.C. Juá fruit (Ziziphus joazeiro) from Caatinga: A source of dietary fiber and bioaccessible flavanols. Food Res. Int. 2020, 129, 108745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M.; Kapusta, K.; Kołodziejczyk, W.; Saloni, J.; Żbikowska, B.; Hill, G.A.; Sroka, Z. Antioxidant Activity of Selected Phenolic Acids–Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay and QSAR Analysis of the Structural Features. Molecules 2020, 25, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal Natural Products—A Biosynthetic Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Bognor Regis, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Khedhri, S.; Polito, F.; Caputo, L.; De Feo, V.; Khamassi, M.; Kochti, O.; Hamrouni, L.; Mabrouk, Y.; Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; et al. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial Properties, and Anti-Enzymatic Effects of Eucalyptus Essential Oils Sourced from Tunisia. Molecules 2023, 28, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Li, T.; Qi, J.; Jiang, T.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Effects of Lactic Acid Fermentation-Based Biotransformation on Phenolic Profiles, Antioxidant Capacity and Flavor Volatiles of Apple Juice. LWT 2020, 122, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaw, E.; Ma, Y.; Tchabo, W.; Apaliya, M.T.; Wu, M.; Sackey, A.S. Effect of lactobacillus strains on phenolic profile, color attributes and antioxidant activities of lactic-acid-fermented mulberry juice. Food Chem. 2018, 250, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongmo, S.N.; Procopio, S.; Sacher, B.; Becker, T. Flavor of Lactic Acid Fermented Malt Based Beverages: Current Status and Perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 54, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oil Concentration | Sample | Extract | pH | Number of Viable LAB Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (v/v) | °P | - | logN | ||||

| 0 h | 48 h | 0 h | 48 h | 0 h | 48 h | ||

| - | Control | 12.77 ± 0.38 a | 12.62 ± 0.29 a | 4.99 ± 0.05 b | 3.77 ± 0.05 c | 7.54 ± 0.22 e | 9.04 ± 0.33 h |

| 0.01 | Rosehip oil | 13.00 ± 0.39 a | 12.77 ± 0.33 a | 4.96 ± 0.03 b | 3.72 ± 0.0 c | 7.18 ± 0.32 f | 8.49 ± 0.43 hi |

| 0.02 | 12.84 ± 0.25 a | 12.67 ± 0.32 a | 4.95 ± 0.04 b | 3.72 ± 0.06 c | 7.26 ± 0.21 g | 7.04 ± 0.36 j | |

| 0.03 | 12.91 ± 0.33 a | 12.72 ± 0.32 a | 4.95 ± 0.03 b | 3.73 ± 0.03 c | 7.35 ± 0.26 fg | 7.18 ± 0.38 j | |

| 0.01 | Lemongrass oil | 12.74 ± 0.33 a | 12.60 ± 0.33 a | 4.84 ± 0.06 b | 3.85 ± 0.04 c | 7.45 ± 0.29 f | 8.40 ± 0.43 hi |

| 0.02 | 12.77 ± 0.38 a | 12.62 ± 0.31 a | 4.97 ± 0.05 b | 3.84 ± 0.05 c | 7.27 ± 0.32 f | 8.48 ± 0.39 hi | |

| 0.03 | 12.86 ± 0.34 a | 12.81 ± 0.34 a | 4.95 ± 0.02 b | 4.45 ± 0.04 d | 7.43 ± 0.22 f | 7.00 ± 0.42 j | |

| 0.01 | Eucalyptus oil | 12.96 ± 0.26 a | 12.77 ± 0.35 a | 4.95 ± 0.06 b | 3.73 ± 0.07 c | 7.79 ± 0.26 ef | 8.18 ± 0.38 i |

| 0.02 | 12.74 ± 0.36 a | 12.60 ± 0.36 a | 4.95 ± 0.06 b | 3.84 ± 0.06 c | 7.57 ± 0.27 f | 8.00 ± 0.46 i | |

| 0.03 | 12.72 ± 0.29 a | 12.60 ± 0.35 a | 4.90 ± 0.09 b | 3.83 ± 0.05 c | 7.49 ± 0.26 f | 8.00 ± 0.39 i | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Botella, F.; Gaytanska, Y.; Goranov, B.; Denkova-Kostova, R.; Shopska, V.; Kostov, G. Production of Lactic Acid Wort-Based Beverages with Rosehip, Lemongrass, and Eucalyptus Oils. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12855. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412855

Botella F, Gaytanska Y, Goranov B, Denkova-Kostova R, Shopska V, Kostov G. Production of Lactic Acid Wort-Based Beverages with Rosehip, Lemongrass, and Eucalyptus Oils. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12855. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412855

Chicago/Turabian StyleBotella, Fanny, Yordanka Gaytanska, Bogdan Goranov, Rositsa Denkova-Kostova, Vesela Shopska, and Georgi Kostov. 2025. "Production of Lactic Acid Wort-Based Beverages with Rosehip, Lemongrass, and Eucalyptus Oils" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12855. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412855

APA StyleBotella, F., Gaytanska, Y., Goranov, B., Denkova-Kostova, R., Shopska, V., & Kostov, G. (2025). Production of Lactic Acid Wort-Based Beverages with Rosehip, Lemongrass, and Eucalyptus Oils. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12855. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412855