1. Introduction

The equatorial electrojet (EEJ) is an electric current system positioned above the dip equator [

1]. The EEJ is typically located in the E layer of the ionosphere (approximately 110 km altitude) and is observed on the dayside of the Earth. The EEJ is generally oriented parallel to the Earth’s surface, with current flowing from west to east [

2]. This phenomenon results from the uneven distribution of electron density in the ionosphere, which is affected by solar radiation and the interaction between the geomagnetic field and ionospheric currents. At Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite altitudes, the eastward-directed EEJ induces southward magnetic-field perturbations. These perturbations oppose the background geomagnetic field at this altitude, thereby weakening it [

3]. Compared with high-altitude satellites, LEO satellites lie in closer proximity to the ionosphere, enabling the EEJ signal to be detected more readily. Moreover, the equator is crossed more frequently by the satellites, at intervals of approximately 90 min.

Previous studies of the EEJ have primarily focused on its global spatial scale, distribution, and seasonal variations [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Notable longitudinal variations in EEJ intensity were demonstrated by Lühr et al. (2004) through magnetic measurements obtained from the CHAMP satellite, with maxima near −45°, −90°, and 100°, and a minimum observed near 50° [

2]. Magnetic surveys conducted by CHAMP and magnetic data from six paired equatorial stations were utilized by Manoj et al. (2006). Correlation coefficients (c.c.) between ground-based and satellite data were computed to elucidate the spatial structure of the EEJ. A high correlation between ground-based and satellite data was observed when the CHAMP satellite passed directly over the observation stations; however, this correlation declined rapidly as the longitudinal distance between the satellite and these stations increased. A significant reduction in correlation was observed when the longitudinal separation reached 15°, indicating that the spatial correlation length of the EEJ is shorter than this longitudinal range [

13]. Swarm data analyzed by Zhou et al. (2016) revealed that the EEJ exhibits pronounced longitudinal variability, rather than a uniform distribution along the equator. This feature is distinctly present during daytime hours (06:00–18:00 LT) and nearly disappears at night. One of the most salient features is the pattern, particularly prominent in August, thereby demonstrating strong seasonal dependence. Current-density peaks were observed at −180°, −90°, 0°, and 90°, consistent with earlier observations obtained from the CHAMP satellite [

9].

The spatial variations in the EEJ have been linked to controlling sources, such as tidal wind fields. England et al. (2006), based on CHAMP satellite observations, demonstrated that during equinox seasons, the EEJ exhibits a WN4 longitudinal pattern, which was attributed to the modulation of ionospheric electric fields by the DE3 tidal component [

14]. It was shown by Lühr and Manoj (2013) that various non-migrating tidal components, including DE3, DW5, SW3, SW4, and SW6, contribute significantly to the longitudinal structure of the EEJ. The observed longitudinal variation in the EEJ was considered to result from upward-propagating tides from the lower atmosphere that couple with the ionospheric wind field. It was further proposed that these tidal components modify the neutral wind, thereby impacting the ionospheric dynamo process and ultimately accounting for the observed spatial variability in EEJ intensity [

15]. Longitudinal wave patterns of the EEJ during both magnetically quiet and disturbed periods were investigated by Xiong et al. (2016). It was revealed that even under disturbed conditions (

), the WN4 pattern of the EEJ remains distinctly identifiable—particularly around the September equinox—although its amplitude is reduced compared to quiet periods [

16].

One limitation in studying the spatial scale and variations in the EEJ is the reliance on data analyzed from a single satellite, such as CHAMP. The spatial longitudinal gradient of magnetic measurements obtained from two Swarm satellites, namely Swarm-A and Swarm-C, was calculated by Zhou et al. (2016). Swarm-A and Swarm-C fly side-by-side, maintaining a fixed longitude of 1.4°. Analysis of gradient data derived from Swarm during 2014–2015 by Zhou et al. revealed clear local time and seasonal dependencies in the longitudinal gradient distribution of the EEJ. Differences in the locations of longitudinal tidal patterns between the gradient of the EEJ and the EEJ itself were further demonstrated. These results suggest that the gradient of the EEJ may capture local structures at very small spatial scales, approximately 150 km [

9,

17].

In this study, the gradient data from Swarm-A and Swarm-C are derived to investigate the local structures of the EEJ over a time period spanning 2014 to 2020, corresponding to half a solar cycle. The relationship between small-scale characteristics and previously reported large-scale averaged results is examined. The data and methodology are introduced in

Section 2. Statistical results are presented in

Section 3.

Section 4 and

Section 5 contain discussions and conclusions, respectively.

2. Data and Methods

Magnetic data obtained from the Swarm satellites are utilized in this study. The Swarm satellites were launched on 22 November 2013, with an orbital inclination of 87.5°. The Swarm mission comprises three satellites: Swarm-A and Swarm-C, which fly side-by-side at relatively lower altitudes (approximately 475 km), and Swarm-B, which orbits at a higher altitude (approximately 523 km) [

18]. The final orbital distribution was determined in April 2014. For this study, the horizontal components of geomagnetic data from Swarm-A and Swarm-C, covering the period from 16 April 2014 to 31 December 2020, were selected. During this period, Swarm-A remained approximately 1.4° west of Swarm-C at the same altitude.

Geomagnetic data from the Vector Fluxgate Magnetometer (VFM) onboard Swarm-A and Swarm-C, sampled at 1 Hz across the three components

X,

Y, and

Z, were used to derive the longitudinal gradient measurements necessary for EEJ estimation [

17]. The satellite orbit data selected for analysis are limited to a local time range from 09:00 to 15:00. In total, 10,495 pairs of equator-crossing satellite tracks were considered.

The magnetic horizontal component (

) is calculated using

, where

and

denote the northern and eastern components, respectively, in the NEC coordinate frame. To extract the magnetic fields associated with the EEJ, a series of data processing steps are employed to eliminate signals from other sources. The first step involves the removal of the main field and its secular variations by utilizing the CHAOS-7 core field model, which includes spherical harmonic degrees up to

n = 20 [

19,

20].

Secondly, magnetic disturbances resulting from large-scale ionospheric and magnetospheric current systems are removed by using empirical along-track data processing methods. At LEO altitudes, the space current sources comprise ionospheric solar-quiet (

) currents, magnetopause currents, ring currents, and cross-tail currents. It is recognized that modeling these current systems individually over a brief period poses challenges. Therefore, it is assumed that both the positions and intensities of these currents remain constant as the satellite crosses the mid-low latitudes. To represent the magnetic contributions from these currents, a straightforward fourth-order polynomial model is applied to the magnetic data for each individual track in relation to latitude. This mathematical model is well-suited to describe the smooth, large-scale magnetic field variations produced by current systems with very large spatial extents [

2,

21,

22]. The dip latitude range was expanded to ±45°. Consequently, the residuals of the

component, denoted as

, are expected to primarily represent signals arising from the EEJ, lithospheric fields, and other minor magnetic disturbances.

3. Characteristics in Spatial Gradients of EEJ

Considering that the fixed longitudinal separation of 1.4° exists between Swarm-A and Swarm-C,

is calculated to represent the small-scale spatial variations in the EEJ, where

and

denotes

at the center of the EEJ for Swarm-A and Swarm-C, respectively.

is further used to represent the longitudinal gradient of the EEJ.

where

represents the distance between the EEJ’s central positions of Swarm-A and Swarm-C. The unit of

is nT/100 km.

According to our definition, since Swarm-A is always located to the west of Swarm-C, a negative gradient indicates an eastward decrease in the EEJ’s magnitude, while a positive gradient indicates the opposite. These spatial gradient patterns thus reflect the varying characteristics of the EEJ.

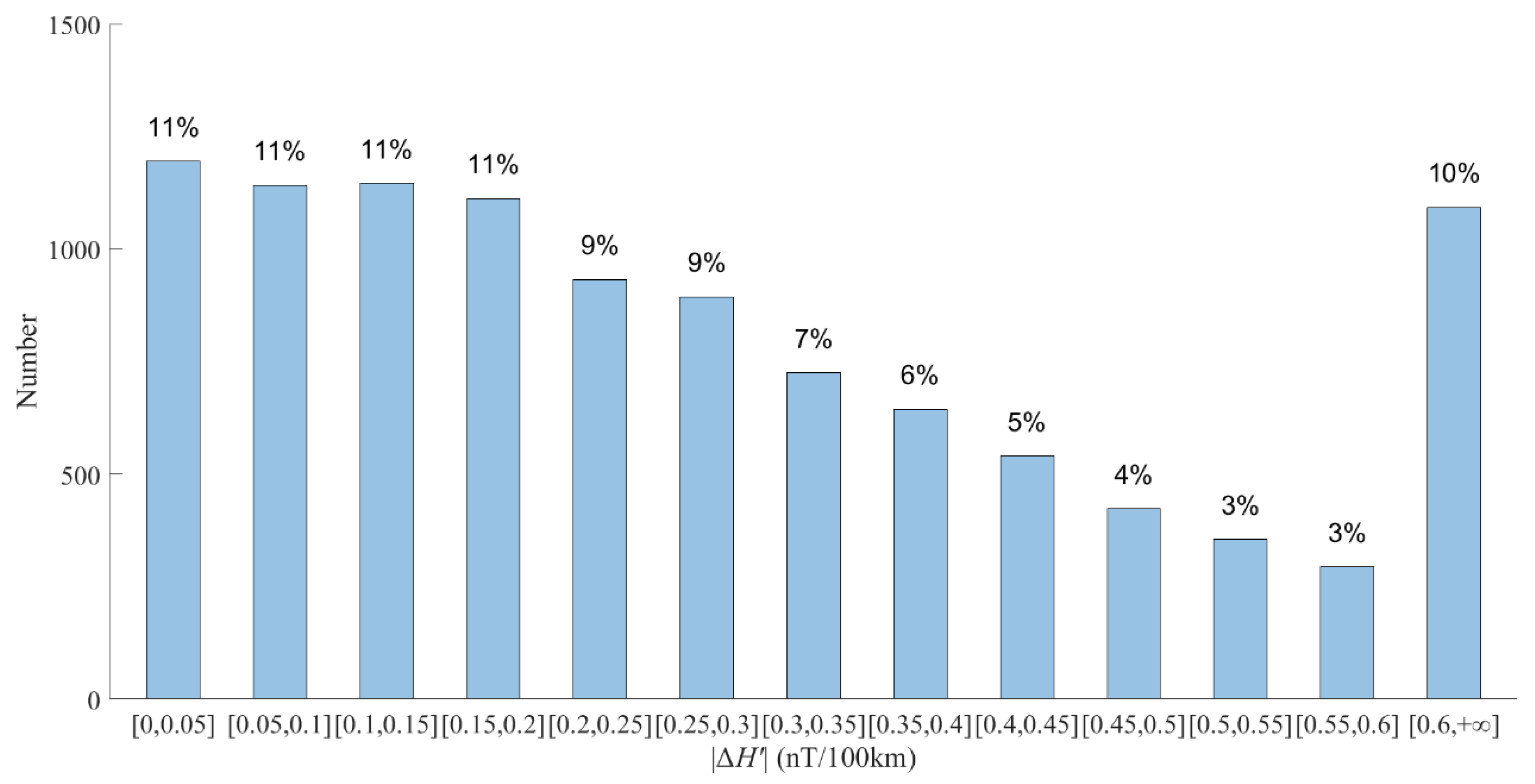

Figure 1 presents the distribution of

values across different bins. Twelve bins were established for values below 0.6 nT/100 km, with a bin width of 0.05 nT/100 km. It is shown that 91% of

values fall below 0.6 nT/100 km, while 9% exceed this threshold.

Specifically, the first four bins representing the smallest values account for approximately 44% of the total cases. This suggests that a large number of samples exhibit longitudinal gradients below 0.2 nT/100 km. This value corresponds to a magnetic difference of 10 nT over a longitudinal distance of 50° near the equator. It should be noted that the average magnitude of EEJ signals derived in this study is below 10 nT. As increases, the number of cases decreases progressively. Approximately 10% of cases have values exceeding 0.6 nT/100 km. This characteristic will be further discussed in the following sections.

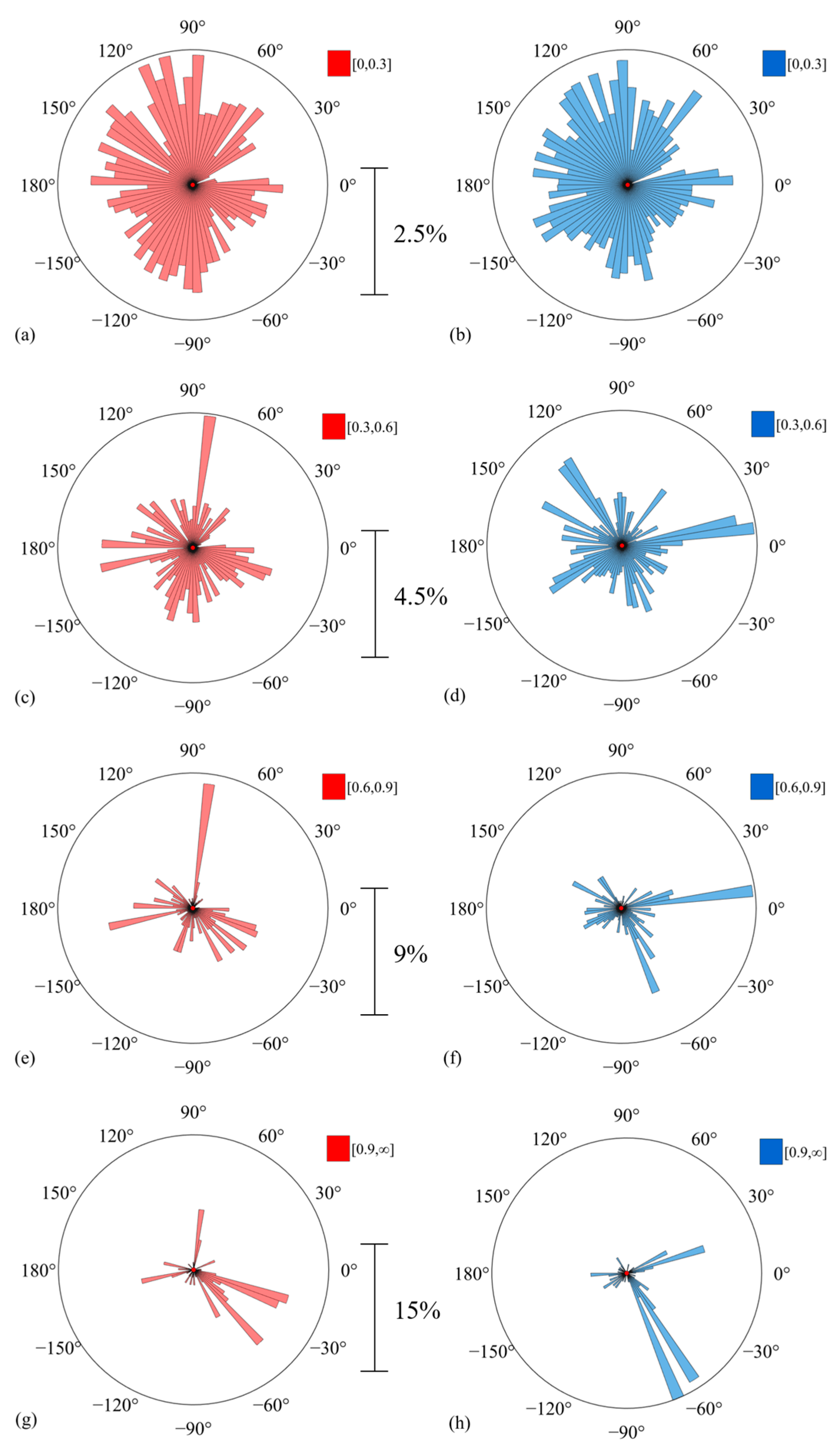

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of

with respect to longitude for various value ranges. Red dots represent cases with

, and blue dots refer to those with

. In

Figure 2a,b, where the gradients are low, no evident longitudinal dependence is observed in the case distribution. Relatively fewer cases are observed from −60° to 60°. For values exceeding 0.6 nT/100 km, notable patterns of longitudinal preference are observed. For cases with positive

, a significant percentage is observed around 120°, −30°, and −170°, respectively. The patterns for these situations are consistent. Meanwhile, for negative

, more cases tend to appear around −60°, 10°, and 140°, respectively. Each longitudinal preference is confined to a narrow range. These patterns suggest that the variations in EEJ are consistently stronger at these longitudes.

Figure 2 demonstrates the statistical results of longitudinal distributions in spatial gradients of EEJ. In the situation of

exceeding 0.6 nT/100 km, clear patterns of longitudinal dependence are observed, indicating that the spatial variations in EEJ in this area are significantly higher than in other regions.

In

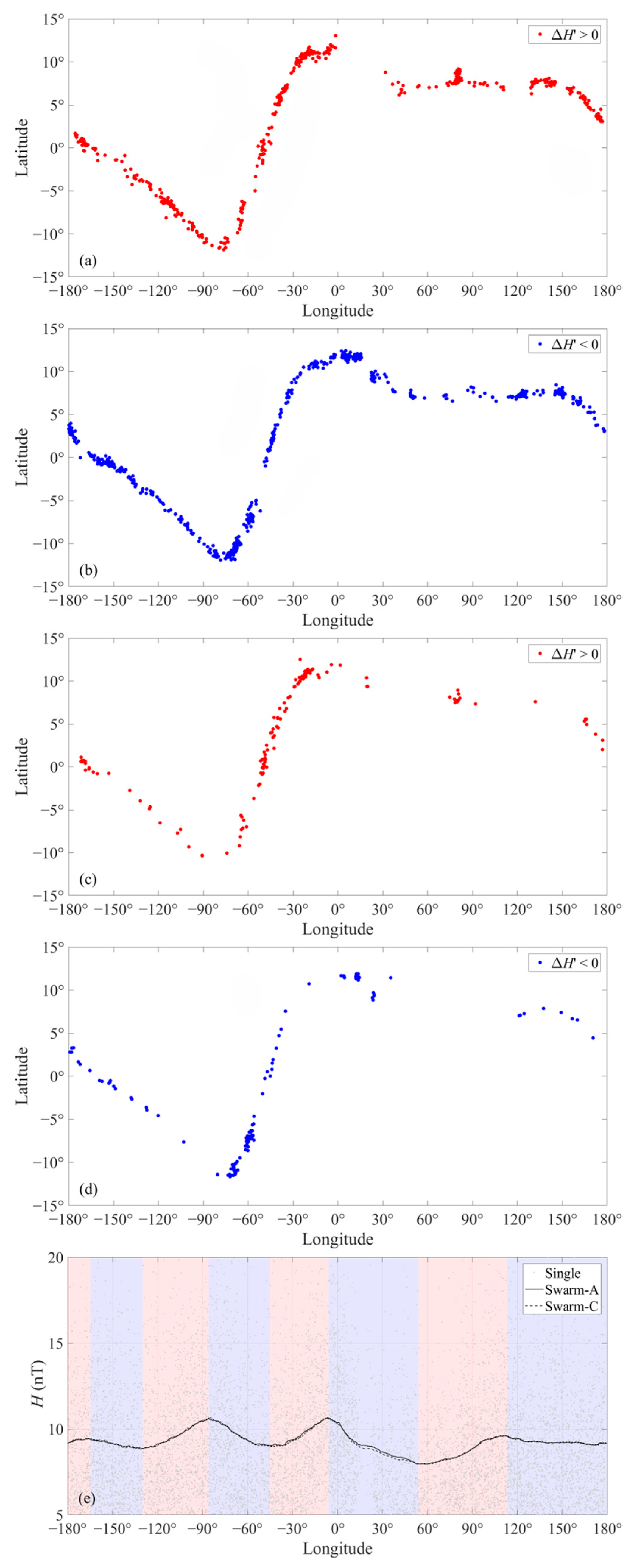

Figure 3a–d, the global distributions of

for higher gradient values are specifically presented. Positive and negative values are marked by red and blue dots, respectively.

Figure 3a–d illustrate the global distribution of

. Specifically,

Figure 3a,b show that the values of

are greater than 0.6 nT/100 km and less than 0.9 nT/100 km. In the figure,

(shaded in red) indicates that the

immediately east of the point is stronger than at the point itself, whereas

(shaded in blue) indicates that the

immediately east of the point is weaker.

Figure 3c,d denote

values greater than 0.9 nT/100 km.

Figure 3e denotes

at different longitudes worldwide. The solid line is derived from Swarm-A data, and the dashed line is derived from Swarm-C data.

In

Figure 3a,b, the points are consistently located along the dip equator. Among the

cases, several pronounced clusters appear at approximately −170°, −30°, and 80°, indicating a sudden intensification of the EEJ in those sectors. Conversely, the sectors near −80°, 0°, and 110° are dominated by blue points (

), reflecting an abrupt weakening of the EEJ there.

In

Figure 3c,d, as

increases, the number of events progressively declines. The most prominent signals are the blue points in the interval [−80°, −50°] and the red points in [−50°, −10°], indicating that the EEJ in this sector first weakened and then strengthened. A concentration of red points near 80° further demonstrates a marked intensification of the EEJ in that region. Notably, around −160°, a small cluster of red points appears within the prevailing blue population, revealing a transient episode in which the EEJ abruptly intensified and then quickly subsided.

For comparison,

Figure 3e shows that the magnetic field produced by the EEJ generally falls within the range of 7–11 nT. The red and blue background colors indicate increases and decreases in

H. Several regions of EEJ enhancement are identified: [−130°, −90°], [−45°, −10°], and [60°, 110°], with the fastest increase occurring in [−30°, −10°]. Conversely, pronounced weakening occurs in [−80°, −45°], and [−10°, 60°], with the steepest decrease observed in [−80°, −55°]. These results are fully consistent with those presented in

Figure 3c,d.

As shown in

Figure 3e, after applying the moving-average filter the profile agrees well with previous studies. However, regarding small-scale variations, the EEJ changes are pronounced, ranging from about 5 nT at the minimum to nearly 20 nT at the maximum.

Figure 1 shows that approximately 44% of the cases have

less than 0.2 nT/100 km. This magnetic-gradient result is consistent with the small-scale results in

Figure 3 and is much more pronounced than the results for the averaged large-scale magnetic gradient.

Figure 3e illustrates the global variation in the EEJ by recording the values of

H at different longitudes. It confirms that

Figure 3a,d faithfully represent the true distribution of

. A distinctive phenomenon is observed near the South Atlantic.

Figure 3d shows that the large

values are centered near −60°, while

Figure 3c places them near −30°; both zones are characterized by steep magnetic gradients. This feature is equally evident in

Figure 3e: the field weakens rapidly between −80° and −50°, and strengthens sharply from −50° to −10°. Additionally, it is evident that only the South Atlantic region exhibits a strong

signal. Although the absolute minimum

value there is not the smallest globally, the markedly steeper gradient highlights the unique character of the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA).

4. Discussion

During magnetic storms, energy from the magnetosphere can be transmitted to the equatorial region, potentially affecting the EEJ. Therefore, we selected a magnetic storm event to investigate its impact on the EEJ.

Figure 4 presents geomagnetic indices alongside statistical results of the EEJ during a storm event on 22 June 2015.

Figure 4a shows the time series of the Sym-H index. This index is obtained from the OMNI dataset (available at

https://spdf.gsfc.nasa.gov/pub/data/ (accessed on 1 April 2025)).

Figure 4b displays the c.c. of

between Swarm-A and Swarm-B at mid-to-low latitudes.

Figure 4c,d, respectively, show the time series of the longitudinal gradient

and

from Swarm-A.

Figure 4a presents a geomagnetic storm event: Sym-H commenced a steep drop on 22 June, attained its minimum below –200 nT on 23 June, and subsequently began a gradual recovery. In

Figure 4b, the variation in c.c. appears to be influenced by the storm event. The blue dots denote cases where the c.c. exceeds 0.95, whereas the red dots indicate c.c. values below 0.95; a dashed line separates the two groups. Compared with the periods before and after the storm, the c.c. exhibits a pronounced increase and greater stability during the magnetic-storm interval. In

Figure 4c,d, it is worth noting that during the storm,

H and Δ

H′ exhibit dramatic changes that differ from those observed in the pre- and post-storm intervals. These observations suggest that magnetospheric geomagnetic activity may influence the low-latitude ionosphere, yet no clear pattern emerges; more detailed investigations are therefore required.

One additional point to note is that the series of equatorial plasma bubble (EPB) overflow events observed during 22–23 June 2015 over the Europe–Africa and American longitudinal sectors may be related to the pronounced variations in

H and Δ

H′ shown in

Figure 4. The possible mechanism is as follows: large-scale EPBs represent vast plasma density depletion regions in the ionosphere. Such large-scale and long-duration ionospheric disturbances can significantly alter local and even regional ionospheric conductivity and electric field distributions, thereby directly affecting the paths and intensities of ionospheric current systems such as the EEJ. These changes in current systems would directly manifest as disturbances in the

H [

23].

Moreover, another point is also worth noting. The zonal extent of the EEJ has been reported by Manoj et al. (2006) to be less than 15°. In this study, the longitudinal distribution of the EEJ was observed to be non-uniform, exhibiting a more complex structure, particularly at locations with high spatial gradients. Larger gradient values, indicated by

, were found over the western hemisphere, including the SAA region, illustrating that the local structure of the EEJ occurs at very small spatial scales (~150 km) [

13]. A similar method was applied by Zhou et al. (2016), who focused on tidal signatures in the spatial gradients of the EEJ. They suggested multiple tidal components related to variations in the gradient [

9]. The longitudinal distribution of the EEJ current intensity was described by Lühr et al. (2004) (see their Figure 8) [

2]. Our results of gradient distribution exhibit an overall pattern consistent with that shown by Lühr et al. Specifically, a minimum of the EEJ occurs around −45°, and a maximum occurs around −170° in both the gradient and magnitude distributions in our study (

Figure 3). These patterns may be linked to different tidal components associated with the EEJ’s spatial variation. It is emphasized that the distributions of gradient and magnitude, as, respectively, shown in

Figure 3 and derived from two different methods, demonstrate consistent variations. In

Figure 3d, intense

signals are concentrated over the South Atlantic region, indicating the influence of this area on the distribution of the EEJ. The mechanism underlying this influence will be further investigated in future work.