Featured Application

The optimized pasta formulation developed through response surface methodology provides a functional alternative to conventional pasta, enriched with natural antioxidants, β-glucans, and vitamin C. The application of microencapsulated polyphenols allows the incorporation of thermolabile bioactive compounds while preserving their stability during pasta processing and drying. Oat fiber and sauerkraut juice contribute to the nutritional enhancement and sensory differentiation of cereal-based products. The study demonstrates the potential of response surface methodology as a tool for designing innovative, health-promoting pasta formulations that meet consumer expectations for natural and functional foods.

Abstract

The study aimed to optimize the formulation of a functional pasta enriched with microencapsulated polyphenols, oat fiber, and sauerkraut juice using response surface methodology. The effects of these ingredients on key quality attributes, including viscosity, color, hardness, bioactive compound content, antioxidant activity, and consumer acceptance, were evaluated. The optimized formulation contained 11.59% microcapsules, 6.12% oat fiber, and 11.93% sauerkraut juice. The optimized pasta exhibited high levels of polyphenols (127.81 ± 10.20 mg GA/100 g), flavonoids (28.10 ± 1.74 mg QE/100 g), β-glucan (1.52 ± 0.21%), and vitamin C (4.72 ± 0.31 mg/100 g), accompanied by increased total antioxidant activity (34.12 ± 2.45%). The incorporation of microcapsules and fiber affected the rheological and textural properties, resulting in higher viscosity and firmness, while sauerkraut juice enhanced vitamin C retention and contributed natural acidity and color. The experimental data closely matched the predicted values (R2 > 0.85), confirming the adequacy of the developed models. Despite minor differences in texture and color compared to conventional pasta, the product maintained favorable sensory acceptance (5.82 ± 0.33). The results demonstrate that the integration of encapsulated polyphenols, dietary fiber, and fermented vegetable ingredients enables the development of pasta with enhanced nutritional and functional value without compromising consumer appeal.

1. Introduction

Pasta is one of the most widely consumed cereal-based foods worldwide, with Europe representing a significant share of global consumption. According to recent statistics, the per capita consumption of pasta in certain European countries exceeds 10 kg per year, reflecting its role as a staple in daily diets [1]. Globally, pasta production has steadily increased over the past decades due to its convenience, long shelf-life, and adaptability in various culinary applications. Beyond its traditional form, pasta serves as an ideal matrix for nutritional enhancement, offering opportunities to fortify the product with bioactive compounds, dietary fiber, and micronutrients [2,3]. Moreover, the use of diverse cereal raw materials—including flours derived from gluten-free sources such as rice or potato, as well as ancient wheat varieties such as spelt—has gained interest in both industrial and research contexts. While spelt (Triticum spelta) is not an alternative to wheat in the gluten-free sense, it differs from common wheat (Triticum aestivum) in its composition, fiber content, and micronutrient profile, which can influence the technological quality and nutritional value of pasta. These modifications to the protein, starch, and fiber composition in both gluten-free flours and ancient wheat varieties offer opportunities to enhance the nutritional profile and functional properties of cereal-based products, supporting the growing interest in developing pasta with improved attributes [4,5]. Given the growing use of such raw materials to enhance the nutritional value of food, their application in the present study was well justified, as it aligned with the rationale of developing a functional, enriched product. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge potential health-related concerns associated with pasta consumption. Although pasta is often viewed as a refined carbohydrate, its structure gives it a relatively low glycemic index, which may mitigate rapid post-prandial glucose spikes [6,7,8]. However, excessive intake, particularly without proper portion control or in the context of a high-glycemic diet, may theoretically contribute to energy overconsumption and long-term risk of obesity [9].

Polyphenols are a large class of plant-derived bioactive compounds with demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective effects. In particular, blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) is a rich source of anthocyanins, flavonols, and phenolic acids, which contribute to its high antioxidant capacity and potential to reduce oxidative stress in the human body [10]. Despite their beneficial properties, polyphenols are inherently sensitive to environmental conditions such as heat, light, oxygen, and pH variations, which often occur during food processing, including pasta extrusion and cooking. These factors can significantly reduce their bioavailability and functional efficacy in the final product. To overcome these limitations, microencapsulation has emerged as a powerful strategy for stabilizing bioactive compounds. By entrapping polyphenols within protective matrices such as maltodextrin, microencapsulation minimizes degradation, prevents premature release, and allows for controlled delivery within food systems. This approach also helps to mask undesirable flavors or colors that could negatively impact sensory acceptance while preserving the bioactive properties of the encapsulated compounds [11,12].

Recent advances in the characterization of Ribes nigrum L. (blackcurrant) have revealed a remarkably diverse and abundant polyphenolic profile, which explains its growing use as a functional ingredient in food systems. Blackcurrant is particularly rich in anthocyanins, mainly delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside, delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, which collectively account for over 80% of its total phenolic content [13,14]. In addition, flavonols (quercetin and myricetin derivatives), phenolic acids (chlorogenic and caffeic acids), and proanthocyanidins contribute to its strong antioxidant potential [15]. Recent metabolomic studies have emphasized not only the quantitative dominance of anthocyanins but also the stability-improving effects of minor compounds such as catechins and hydroxycinnamic acid esters, which can interact synergistically with encapsulation matrices. Furthermore, blackcurrant polyphenols have been associated with multiple bioactive effects, including modulation of oxidative stress, anti-inflammatory action, and improvement of gut microbiota balance. These findings highlight blackcurrant as a valuable natural source of polyphenols for microencapsulation, offering both technological advantages and nutritional enhancement when incorporated into cereal-based foods such as pasta [16].

The stability of polyphenols derived from black currant—particularly anthocyanins—has been extensively reported to depend on storage conditions and exposure to thermal processing. Long-term dry storage typically results in a gradual degradation of anthocyanins following temperature-dependent kinetics, with significantly faster losses observed at ambient or elevated temperatures compared to refrigerated conditions. Several studies have shown that anthocyanins stored for extended periods (up to 12 months) undergo substantial declines in concentration and antioxidant capacity, especially when exposed to oxygen, light, or temperatures above 20–25 °C [17,18,19]. In contrast, low-temperature storage (e.g., −20 °C) markedly slows the rate of degradation, indicating that frozen or cold-chain conditions are effective at preserving black currant polyphenols in powder form [17,19].

Thermal exposure during food preparation—such as boiling, steaming, pressure cooking, baking, or frying—further accelerates the breakdown of black currant anthocyanins. Reported retention levels vary widely depending on temperature, duration, and matrix composition, but cooking commonly results in notable losses, ranging from moderate reductions to decreases exceeding 80–90% under intense heat treatment. The degradation mechanisms primarily involve hydrolysis and oxidation of the anthocyanin structure, along with additional effects from pH changes, metal ions, and enzymatic activity [20].

To mitigate these losses, several authors have demonstrated that microencapsulation can markedly improve the stability of black currant polyphenols. Encapsulation using polysaccharides or proteins, spray-drying techniques, or co-encapsulation with co-pigments has been shown to protect anthocyanins during storage and enhance their resistance to thermal degradation [17,20]. Such protective systems help maintain color intensity and antioxidant activity, making microencapsulation a promising strategy for incorporating black currant polyphenols into thermally processed foods such as pasta.

Dietary fiber is another critical component in the development of functional pasta products. In addition to their fiber fractions, oat-derived ingredients contain a range of bioactive compounds that further enhance their functional value. Oat fiber is naturally rich in avenanthramides, a unique group of phenolic alkaloids with well-documented antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and vasoprotective properties. Moreover, oats provide phenolic acids (ferulic, caffeic, and p-coumaric acids), tocopherols, and phytosterols, which support lipid-lowering activity and offer additional antioxidant protection [21,22,23,24]. Oat fiber, especially fractions with a high content of β-glucans (up to 30%), is recognized for its health-promoting effects, including modulation of postprandial glycemic response, reduction in serum cholesterol levels, and positive influence on gut microbiota [21,25]. The incorporation of β-glucan-rich oat fiber into pasta formulations not only enhances nutritional value but can also affect technological and textural characteristics, such as water absorption, cooking loss, and firmness, which are important for consumer acceptability [26,27]. Similarly, the inclusion of vegetable-derived ingredients, such as sauerkraut juice, introduces natural sources of vitamin C and other bioactive compounds, while potentially modifying the acidity, dough rheology, and textural properties of the final product [28,29]. Sauerkraut provides some of the B-group vitamins, organic acids (primarily lactic acid), lactic acid bacteria metabolites, minerals (K, Ca, Mg), glucosinolates, and a range of phenolic compounds derived from both cabbage tissue and microbial fermentation (kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin, ferulic acid, and other phenolic acids). These constituents may contribute to antioxidant capacity, support gut health through fermentation-derived metabolites, and moderately enhance the micronutrient profile of the pasta [30,31,32,33]. Although the enrichment levels achieved in this study do not result in high absolute concentrations of these nutrients, they nevertheless introduce bioactive components that are absent in conventional pasta. Despite these beneficial properties, it should also be noted that the use of sauerkraut juice may introduce several technological challenges. Sauerkraut juice, due to its naturally low pH and characteristic fermented flavor profile, can influence the sensory perception of the final product, potentially increasing acidity or imparting sour notes undesirable in traditional pasta. The reduced pH may additionally affect dough rheology and cooking behavior. Furthermore, the inclusion of aqueous acidic ingredients raises concerns related to stability of sensitive compounds, such as phenolics, which may undergo partial degradation when exposed to low pH environment. The use of stabilization techniques such as encapsulation helps mitigate some of these effects by improving the stability of polyphenols, however interactions between encapsulated particles and the dough matrix may still affect textural properties or color [34,35]. These ingredients provide an additional approach to enhance the functional and nutritional quality of pasta beyond conventional cereal-based formulations.

The present study aimed to investigate the impact of replacing conventional pasta ingredients—spelt flour, tapioca flour, and water—with functional ingredients, specifically microencapsulated blackcurrant polyphenols, oat fiber rich in β-glucans, and sauerkraut juice. The levels of enrichment were varied from 0 to 18% for microcapsules, 0 to 10% for oat fiber, and 0 to 30% for sauerkraut juice, enabling a systematic evaluation of the combined effects of these components on pasta physicochemical properties. The main objective of the study was to develop a pasta product enriched with bioactive compounds, characterized by enhanced biological activity, while maintaining physical properties and an aromatic profile comparable to the control sample, as well as ensuring consumer acceptability. Accordingly, the parameters targeted for maximization included total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), total antioxidant activity (TAA), β-glucan content, vitamin C content, and overall consumer acceptance. In contrast, the color difference coefficient (ΔE*) was designated as the parameter to be minimized. Additionally, desirable target values for viscosity, hardness, and volatile organic compound (VOC) distances were established based on the characteristics of the control sample. It was presumed that the application of a modified formulation enriched with selected functional ingredients would enable the development of a functional pasta dough with improved bioactive properties while preserving favorable physicochemical and sensory characteristics. By analyzing parameters such as texture, and compositional changes, the study provides insights into the potential of functional ingredients to enhance both the nutritional profile and sensory characteristics of pasta, offering a basis for the development of healthier and more functional cereal-based foods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The ingredients used for pasta production included spelt (Melvit, Olszewo Borki, Poland), rice (Melvit, Olszewo Borki, Poland), tapioca (Brat Sp. z o.o., Rabka-Zdrój, Poland), and potato flours (Kupiec, Krzymów, Poland), water, salt (Cenos Sp. z o.o., Września, Poland) and canola oil (Bielmar, Bielsko-Biała, Poland). Spelt flour used in the study was Melvit ‘Mąka orkiszowa’ (1 kg package). According to the manufacturer’s specification, it is a white spelt flour obtained from cleaned spelt grains, without bran fraction (not wholemeal). The nutritional composition per 100 g is as follows: 326 kcal, 14 g protein, 59 g carbohydrates, 6 g dietary fiber, and 2 g fat. Although ash content is not declared on the label, the product corresponds to a refined (low-ash) spelt flour grade commonly available on the Polish market. Further ingredients such as oat fiber (Microstructure, Warsaw, Poland), polyphenol microcapsules and sauerkraut juice were also used. Sauerkraut was prepared using fresh white cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. alba). Fresh white cabbage was shredded to a particle size of approximately 2–3 mm and mixed with 2.0% (w/w) sodium chloride. The material was then inoculated with a defined lactic acid bacteria (LAB) starter culture containing Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (Serowar s.c., Szczecin, Poland) at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/g, following standard industrial sauerkraut fermentation practices. The cabbage was tightly packed into sterile glass fermentation vessels, ensuring anaerobic conditions, and incubated at 22–24 °C for 7 days. During fermentation, the LAB starter culture rapidly acidified the medium, leading to the typical development of lactic fermentation metabolites. At the end of fermentation, the sauerkraut was pressed, and the resulting juice was collected, filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane, and stored at 4 °C until further analysis. The final pH of the sauerkraut juice was 3.45 ± 0.05. All ingredients used in the study were of natural origin and safe for consumption. All chemicals were supplied by Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Microencapsulated Polyphenols

To prepare the blackcurrant extract, blackcurrant powder and a 30% aqueous ethanol solution were used in a 1:5 ratio, which were extracted using ultrasound for 1.5 h. Pilot studies determined that this extraction system allowed us to obtain a base extract with 10 °Brix, which was further used as the core material in the microencapsulation process. The matrix material used was a 10% aqueous maltodextrin solution.

Microcapsules were prepared using a 1:4 core-to-shell ratio [36]. The matrix and core solutions were homogenized for 4 min at 10,000 rpm using IKA Magic LAB homogenizer (IKA-Werke GmbH & Co., KG, Staufen, Germany). The mixture was frozen and subjected to freeze-drying at a shelf temperature of 2.5 °C and a pressure of 0.1 mbar for 48 h, followed by an additional 12 h at 5 °C and 0.1 mbar (Christ Alpha 2-4 LSC, Osterode am Harz, Germany). The resulting microcapsules were ground with a pestle and mortar, then sieved using a vibratory sieve shaker and a steel laboratory sieve (No. 26.113, Zakład Naukowo-Techniczny “EKO-LAB”, Brzesko, Poland). Microcapsules with a size ≤ 300 µm were collected. The obtained powder was stored at −60 °C (Thermo Scientific freezer, Forma 88,000 series, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) until further use.

2.3. Experimental Design

The aim of the study was to analyze the impact of variable components on the physicochemical properties of pasta. Ingredients such as spelt flour, tapioca flour and water were replaced, respectively, by microcapsules containing blackcurrant polyphenols (at a level ranging from 0 to 18% of the total weight of ingredients in the recipe), oat fiber with 30% oat β-glucans (0–10%) and sauerkraut juice (0–30%). Both the selection of raw materials and their share in the product were determined on the basis of an analysis of literature data and pilot studies. The studies by Ćetković et al. [37] and Šeregelj et al. [38], which determined that a 10% share of microencapsulates with carrot waste extract improved the properties of pasta, provided the initial target for determining the level of microencapsulated polyphenols. This amount was deliberately increased to assess the impact of a higher content of this ingredient. The level of oat fiber content was determined based on research by Bustos et al. [39], which found that replacing 20% of the flour with Kañawa (Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen) powder resulted in a product with the desired physicochemical and sensory characteristics, and the study by Makhlouf et al. [40] who achieved similar effect by adding up to 15% fiber to pasta. A study by Rekha et al. [41] on the use of vegetable puree showed that it is possible to use up to 420 g of carrot puree per 1 kg of product, while a study by Panghal et al. [42] showed that pasta containing 30% Syzygium cumini puree had both increased nutritional value and high sensory acceptability. On this basis, the proportion of sauerkraut juice was set at a maximum of 30% substitution.

The proportions of individual ingredients in the formulations were established using Design Expert software (version 11, Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), as shown in Table 1. The central point formulation (denoted as C in Table 1) represents the midpoint of all tested factor levels and was included in five replicates to assess experimental variability and model adequacy.

Table 1.

The experiment layout—ingredients in the recipe [g].

The physicochemical parameters evaluated included: rheological properties such as viscosity, color profile, texture profile, antioxidant properties and bioactive compound content such as polyphenols, flavonoids, vitamin C, β-glucan content and total antioxidant capacity, in addition to volatile compound profile and consumer acceptability. To describe the relationships between the variables (incorporated components) and the responses (being the analyzed physicochemical parameters), a quadratic model was applied. Subsequently, the formulation was optimized, and in the final stage, the calculated model values were verified experimentally.

2.4. Preparation of Pasta

Pasta formulations were prepared according to the compositions presented in Table 1. The dry ingredients (spelt flour, rice flour, tapioca flour, potato flour, salt, oat fiber, and microencapsulated blackcurrant polyphenols) were thoroughly mixed. Canola oil and sauerkraut juice (where applicable) were then added, followed by the gradual addition of water to obtain a dough of suitable consistency. The dough was mixed and subsequently sheeted and cut using a pasta machine to form strips. To ensure consistent post-processing conditions, all pasta samples were dried and stored under strictly controlled environmental parameters. After production, the pasta was dried in a forced-air drying chamber at 40 ± 1 °C with a relative humidity of 60 ± 2% for 12 h (Binder FED 115; Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany), following standard low-temperature drying practices for functional pasta formulations. Prior to drying, the pasta strips had the following physical dimensions: 6.0 ± 0.1 mm in width, 2.5 ± 0.1 mm in thickness, and approximately 200.0 ± 0.1 mm in length. After the drying process (12 h at 40 ± 1 °C and 60 ± 2% RH), the samples showed a typical reduction in moisture content, resulting in a slight shrinkage of the product. The final dimensions of the dried pasta were approximately 5.6–5.8 mm in width, 2.2–2.3 mm in thickness, and 191–195 mm in length. These changes are consistent with the expected dimensional contraction occurring during low-temperature dehydration of cereal-based pasta. The dried samples were then equilibrated at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C) for 1 h and immediately packed in opaque, food-grade polyethylene bags to protect them from light exposure and oxidative degradation of polyphenolic compounds. All samples were stored in a temperature-controlled chamber at 20 ± 1 °C, 45 ± 5% relative humidity, and dark conditions until analysis. The time elapsed between the completion of pasta production (end of drying) and the beginning of physicochemical analyses was 24 h, ensuring adequate moisture equilibration while minimizing biochemical changes during storage. The samples are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Product samples prepared for color analysis.

2.5. Analysis of Rheological Properties

The rheological properties of pasta dough were evaluated using a MARS III rheometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a P20 Ti L measuring geometry and a temperature controller (MTMC, MARS III) using the method by Fradinho et al. with modifications [43], which include extension of the frequency range. Measurements were performed at a sample gap of 2.0 mm, using a sample volume of 0.8 mL. Oscillatory frequency sweep tests were conducted under controlled stress (CS) mode with a stress amplitude of 10 Pa over a frequency range of 0.1–20 Hz at 20 °C. The measurements were carried out in triplicate for each sample. Storage modulus (G′), loss modulus (G″), and complex viscosity (η*) were determined as a function of frequency to characterize the viscoelastic behavior of the pasta dough.

2.6. Analysis of Color Parameters

The color of pasta samples was determined in the CIE Lab* system using a CR-400 spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a standard observer angle of 2°, an 8 mm measuring head, and a D65 daylight illuminant. Calibration was performed against a standard white Minolta tile (L* = 98.45, a* = −0.10, b* = −0.12). For each sample, 10 measurements were taken, and the color difference (ΔE*) between the control and experimental samples was calculated according to the following equation:

where subscript 0 denotes the control sample and subscript 1 denotes the analyzed sample [44].

2.7. Analysis of Texture Parameters

The textural properties of pasta were evaluated using a TA.XTplus Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, Surrey, UK) equipped with a 5 kg load cell and a three-point bending rig (HDP/3PB) mounted on a HeavyDuty Platform (HDP/90). The distance between the two lower supports was set at 40 mm and maintained constant for all measurements. Raw pasta samples were placed centrally on the supports immediately prior to testing. The upper blade was positioned equidistantly above the sample. Measurements were performed in compression mode with return to start, using a pre-test speed of 1.0 mm/s, a test speed of 3.0 mm/s, and a post-test speed of 10.0 mm/s. The test was run over a displacement of 5 mm, with an automatic trigger force of 50 g and automatic tare. Data were acquired at a rate of 500 points per second. The maximum force at break, as well as the force–displacement curve, were recorded to assess the hardness, resistance to bending, and elasticity of the pasta samples. All measurements were carried out five times for each sample employing the methodology by Zhang et al. with modifications [45].

2.8. Analysis of Total Polyphenolic Content

The total polyphenol content (TPC) of pasta samples was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. Briefly, 0.1 mL of sample extract was mixed with 6 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent in a 10 mL volumetric flask. After 3 min, 1.5 mL of saturated sodium carbonate solution was added, and the mixture was made up to volume with distilled water. The samples were incubated in a water bath at 40 °C for 30 min until the characteristic blue coloration developed. Absorbance was measured at 735 nm using a Tecan Spark™ 10 M spectrophotometer (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). The results were calculated from a gallic acid calibration curve and expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 100 g of sample. All determinations were carried out in triplicate [46].

2.9. Analysis of Total Antioxidant Activity

The total antioxidant activity (TAA) of pasta samples was determined according to the method of Wojtasik-Kalinowska et al. [47]. A volume of 0.5 mL of sample extract was mixed with 3.5 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) solution and incubated in the dark for 20 min. Absorbance was then measured at 517 nm using a Tecan Spark™ 10 M spectrophotometer (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). The analysis was carried out in triplicate, and TAA (%) was calculated as follows:

where Ablank denotes the absorbance of the blank and Asample denotes the absorbance of the tested sample.

2.10. Analysis of Flavonoid Content

The total flavonoid content (TFC) of pasta samples was determined according to the method of Onopiuk et al. [48] with modifications. Briefly, 2 mL of sample extract was mixed with 2 mL of 2% AlCl3 solution and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 430 nm using a Tecan Spark™ 10 M spectrophotometer (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). Measurements were performed in triplicate, and TFC was calculated from a quercetin calibration curve and expressed as quercetin equivalents (QE) per 100 g of sample.

2.11. Analysis of Vitamin C Content

The vitamin C content of pasta samples was determined by titration with 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (2,6-DCIP) [49]. The 2,6-DCIP solution was standardized by titration with ascorbic acid solution. For sample analysis, hydrochloric acid extracts were prepared, and due to the dark coloration of the material, 2 mL of chloroform was added to 2 mL of extract. The samples were titrated with standardized 2,6-DCIP solution until a persistent pink coloration appeared. All determinations were performed in triplicate, and vitamin C content was calculated based on the stoichiometric relationship that 1 mL of 2,6-DCIP corresponds to 18.05 μg of ascorbic acid. Results were expressed as mg of vitamin C per 100 g of sample.

2.12. Analysis of β-Glucan Content

The β-glucan content of pasta samples was determined using the AOAC International enzymatic procedure with the Mixed-Linkage β-Glucan Assay Kit (Megazyme International, Bray, Co., Wicklow, Ireland) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sample absorbance was measured at 510 nm using a Tecan Spark™ 10 M spectrophotometer (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland), with the blank as reference. All determinations were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed according to the kit protocol [50].

2.13. Analysis of Volatile Profile

The volatile organic compound (VOCs) profile of pasta samples was analyzed using an electronic nose (Heracles II, AlphaMOS, Toulouse, France) following the procedure described by Wojtasik-Kalinowska et al. with modifications [51]. Briefly, 2 g of each sample were placed in 20 mL headspace vials, sealed with Teflon-faced silicone caps, and analyzed. Compound identification was performed using the AroChemBase database (AlphaMOS, Toulouse, France). Distances between the analyzed and control samples were calculated to assess differences in volatile profiles.

2.14. Consumer Acceptance

Consumer acceptance analysis of pasta samples was performed by 100 untrained panelists aged 19–55 years, recruited from students and faculty of Warsaw University of Life Sciences. Panelists were divided into five groups of 20 individuals. Four groups evaluated samples from the experimental design, while the fifth group assessed sample from the verification stage. Evaluation sessions were conducted in isolated rooms at 23 °C under white lighting. Samples were served in plastic containers coded with three-digit numbers. To minimize order effects, the presentation order of samples was randomized for each panelist using a balanced serving sequence. Participants were provided with still mineral water and instructed to cleanse their palate between evaluating successive samples. Panelists rated appearance, aroma, taste, texture, and overall acceptance using an unstructured 100 mm hedonic scale with marked borders. All evaluation sessions were supervised by trained personnel. Deviations such as incomplete forms or failure to follow instructions were recorded, and any incorrectly completed evaluation card would be excluded from the final dataset at the results analysis stage, if necessary. Consumer acceptance data were further used in statistical analyses, including response surface methodology (RSM). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Warsaw University of Life Sciences–SGGW (protocol code 28/RKE/2024/U).

2.15. Statistical Analysis

The experiment was planned and analyzed using Design Expert software employing the randomized Box–Behnken design type (ver. 11, Stat-Ease, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The effects of independent variables on response parameters were modeled using a quadratic equation, and model accuracy was evaluated through lack-of-fit tests and determination coefficients. RSM was applied to optimize the formulations in order to obtain a final product with increased bioactive compounds content and biological activity, also the physical properties and an aromatic profile similar to that of control sample, as well as displaying consumer acceptability. For this reason, the parameters targeted for maximization included TPC, TFC, TAA, β-glucan content, vitamin C content, and consumer acceptance. The color difference coefficient (ΔE*) was targeted for minimization. Additionally, desired values for specific physicochemical properties were set based on the control sample: viscosity 11,000 Pas, hardness 156.11 g, and VOCs distances 0.00.

Optimization and model verification were conducted by comparing predicted values with experimentally obtained data. The effects of individual variables on product physicochemical properties were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and factor interactions were evaluated using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Statistical differences between predicted and experimental values were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The normality of residuals for RSM models was assessed in Design-Expert using the normal probability plot, which showed no substantial deviations from linearity. Therefore, the assumption of normality required for ANOVA and MANOVA was considered satisfied. In addition, for the model verification step, the distribution of differences between predicted and experimental values was examined and confirmed to be approximately normal.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model’s Adequacy

The adequacy of the developed response surface models was verified using the coefficient of determination (R2) and the lack of fit test (Table 2). High R2 values, exceeding 0.85 for most responses, confirmed a good fit between the experimental and predicted data. The models describing ΔE*, hardness, TAA, vitamin C content, β-glucan content, and consumer acceptance were particularly reliable (R2 ≥ 0.93). Slightly lower, but still acceptable, determination coefficients were obtained for TPC (R2 = 0.794) and VOCs distance (R2 = 0.492). The lack of fit values above 0.05 for almost all responses indicate that the models were adequate and appropriately represented the experimental data. The only exception was VOCs distance (p = 0.026), suggesting that this model may not fully explain the variability of this parameter. Altogether, the statistical results confirm the validity of the models and their suitability for describing the influence of recipe components on the selected quality attributes of the product.

Table 2.

The regression coefficients of the predicted quadratic models for the |η*|, ΔE*, hardness, TPC, TAA, TFC, vit. C, β-glucan content, VOCs distances and consumer acceptance.

3.2. Rheological Properties

According to the obtained regression model (Figure 2), the complex viscosity (|η*|) was significantly affected by the presence of microcapsules (p ≤ 0.001) and oat fiber (p ≤ 0.05). The addition of microcapsules strongly reduced the viscosity of the pasta dough, whereas the oat fiber contributed to an increase. Sauerkraut juice had no significant influence on viscosity (p > 0.05). Quadratic and interaction effects were not statistically significant, suggesting that the observed changes were mainly due to the linear effects of the ingredients. The determination coefficient (R2 = 0.858) and lack of fit value (p = 0.367) confirm the good adequacy of the model.

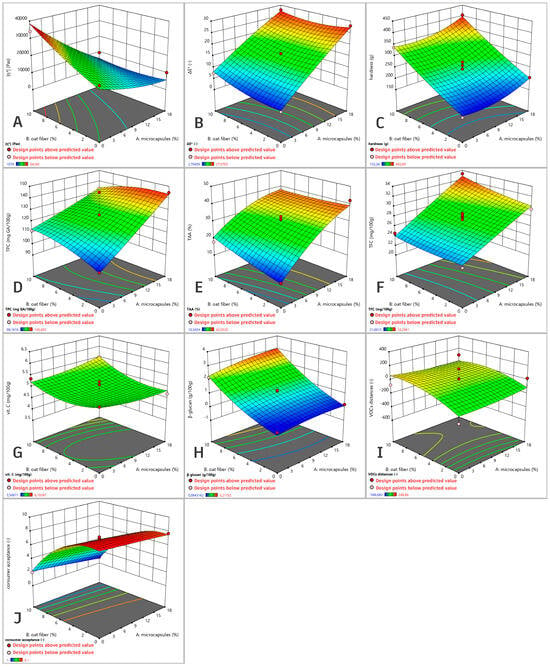

Figure 2.

The 3D surface plots obtained using the model (actual factor: sauerkraut juice 15%). Responses: (A) viscosity, (B) ∆E*, (C) hardness, (D) total polyphenolic content, (E) total antioxidant activity, (F) total flavonoid content, (G) vitamin C content, (H) β-glucan content, (I) VOCs distances, (J) consumer acceptance.

The pronounced decrease in viscosity observed with increasing microcapsules content reflects the measurable weakening of the pasta dough structure, which is consistent with the mechanical explanations presented previously. Microcapsules, due to their spherical morphology and the presence of wall materials such as carbohydrates, can interfere with protein–starch interactions and reduce the cohesiveness and elasticity of the pasta dough [52,53]. Similar effects were reported by Sivam et al. [54], who observed that fiber and polyphenol components reduced gluten hydration and network strength.

The effect of oat fiber, rich in β-glucans, on viscosity increase observed in these results reflects its functional effect in the tested concentration range. This observation aligns with the findings of Lante et al. [55] and Londono et al. [56], who demonstrated that β-glucans enhance water-binding and gel-forming capacity, leading to a denser and more viscous dough system. The hydrophilic nature of β-glucan allows it to compete with proteins for water, resulting in a more compact and resistant structure. The consistency between the model-based results and previous reports supports the validity of the experimental design while providing quantitative evidence specific to this pasta dough system. Altogether, these results indicate a divergent role of functional components in shaping rheological behavior. The results indicate that microcapsules weaken the rheological structure of the pasta dough, while oat fiber contributes to its reinforcement, which may subsequently affect the texture, cooking properties, and microstructure of the final dried product.

3.3. Color

The color difference (ΔE*) was significantly affected by all analyzed factors, with the most pronounced effect observed for microcapsules (p ≤ 0.001). Their addition markedly increased the ΔE* value, indicating a greater deviation in color compared to the control sample. Oat fiber also had a significant but weaker positive influence, both in linear (p ≤ 0.01) and quadratic terms (p ≤ 0.05), while sauerkraut juice slightly reduced ΔE* (p ≤ 0.05). Among interaction terms, only the microcapsules × oat fiber effect was significant (p ≤ 0.05), showing a minor antagonistic relationship between these components. The model exhibited excellent adequacy (R2 = 0.996; lack of fit p = 0.113), confirming its reliability.

The increase in color difference caused by microcapsules can be attributed to the presence of polyphenolic compounds characterized by an intense, dark hue, which substantially modifies the visual properties of the product. A similar phenomenon was reported by Lachowicz et al. [57] and Pasrija et al. [58], where microencapsulated polyphenol or green tea extracts led to visible color changes in bakery products. The encapsulation material itself may also influence light scattering and reflection, enhancing the perceived color intensity.

In contrast, the addition of oat fiber contributed only slightly to the color variation, likely due to its natural beige tint, which does not strongly contrast with the wheat matrix. The minor color-stabilizing effect of sauerkraut juice could be related to the dilution of pigment intensity or potential interactions between anthocyanins and lactic acid fermentation metabolites, as described by Guldiken et al. [59].

Overall, the results confirm that microcapsules are the primary factor responsible for color alteration, while oat fiber and sauerkraut juice exert secondary effects. This outcome is consistent with previous research indicating that the incorporation of functional or encapsulated ingredients often causes visible changes in product color compared to the control formulation.

3.4. Hardness

The hardness of the pasta samples was significantly affected by the addition of microcapsules (p ≤ 0.05) and oat fiber (p ≤ 0.001), while sauerkraut juice showed no significant effect (p > 0.05). Among the quadratic terms, none were statistically significant, and no interaction effects were observed (p > 0.05). The influence of both microcapsules and oat fiber indicates that their incorporation led to an increase in product firmness. The model demonstrated high adequacy (R2 = 0.962; lack of fit p = 0.898), confirming its reliability for describing textural changes.

The results obtained during the product hardness analysis are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation of pasta textural parameters.

The increase in hardness observed after the addition of oat fiber can be attributed to its strong water-binding capacity and its ability to form a more compact and rigid dough structure. Fibers, particularly those rich in β-glucans, limit the mobility of water within the protein–starch network, resulting in a denser and less extensible matrix after drying. This observation is consistent with the findings of Kuèerová et al. [60] and Qasem et al. [61], who reported that the inclusion of dietary fiber in cereal-based doughs increases firmness due to changes in hydration behavior and the restriction of gluten network development.

Similarly, the addition of polyphenol microcapsules also increased pasta hardness. This effect is likely related to the limited integration of encapsulated particles within the gluten–starch matrix. Microcapsules may act as inert fillers, interrupting the continuity of the protein structure and reducing its elasticity, which leads to a firmer texture after drying and cooking. Comparable effects were noted by Elsebaie et al. [62] and Ghasemi et al. [63], where microencapsulated bioactive compounds increased product hardness by modifying the internal matrix organization.

In contrast, the lack of a significant effect from sauerkraut juice suggests that its organic acids and soluble compounds did not markedly influence the mechanical strength of the pasta. However, the juice may indirectly affect texture through its influence on dough hydration and pH, as noted by Arendt et al. [64] in studies on fermented additives in cereal-based products.

The obtained results indicate that both microcapsules and oat fiber contribute to a firmer pasta texture, which can be associated with reduced dough elasticity and modified hydration properties, ultimately affecting the technological and sensory characteristics of the final dried product.

3.5. Total Phenolic Content

The TPC was significantly affected only by the addition of microcapsules (p ≤ 0.01), while the other ingredients and interaction effects were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The positive effect of microcapsules indicates that their incorporation led to an increase in the TPC value in the final product. The model demonstrated acceptable adequacy (R2 = 0.794; lack of fit p = 0.995), confirming that the relationship between formulation and polyphenol content was properly described.

The increase in TPC resulting from the addition of polyphenol microcapsules was expected, as the encapsulated material itself constitutes a concentrated source of polyphenolic compounds. Similar observations were reported by Safaa et al. [65] and Pasrija [58], who noted that enriching bakery products with microencapsulated phenolic extracts markedly increased their TPC. The encapsulation process protects polyphenols from thermal degradation and oxidation during processing, improving their recovery and stability in the final product.

The absence of significant effects from oat fiber and sauerkraut juice suggests that their contribution to the total phenolic pool was minimal. Although both components can contain bioactive compounds—such as ferulic acid in oat bran or phenolic acids in fermented vegetables—their concentration and bioavailability in the used proportions were insufficient to cause measurable changes in TPC. This aligns with findings from Călinoiu et al. [66] and Melini & Melini [67], where the addition of fermented or fiber-rich ingredients only slightly affected total phenolic levels in composite cereal products.

These findings confirm that microencapsulated polyphenols are the primary determinant of phenolic enrichment in the tested formulations, while the other additives play only a supporting or negligible role in shaping this parameter.

3.6. Total Antioxidant Activity

The TAA was significantly influenced by both microcapsules (p ≤ 0.001) and oat fiber (p ≤ 0.05), while sauerkraut juice and the interaction effects were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The quadratic terms for oat fiber and microcapsules showed a significant negative effect (p ≤ 0.05), suggesting that the antioxidant potential increased up to a certain concentration of microcapsules, after which it slightly declined. The high determination coefficient (R2 = 0.963) and non-significant lack of fit (p = 0.206) confirm the reliability of the model.

The positive influence of microcapsules on TAA reflects the high antioxidant capacity of polyphenolic compounds enclosed within the microcapsule matrix. These compounds, mainly anthocyanins and flavanols, are known for their ability to scavenge free radicals and chelate metal ions. Numerous studies, including those by Kurek et al. [68] and Ciont et al. [69], have demonstrated that microencapsulation effectively protects polyphenols during thermal processing, allowing them to retain higher antioxidant activity in the final product compared to unencapsulated forms. The slight decline in antioxidant potential observed at higher concentrations could be linked to the saturation of the system or possible interactions between polyphenols and other dough components, which reduce their accessibility and reactivity.

The addition of oat fiber also slightly enhanced antioxidant activity, likely due to the presence of natural antioxidants such as avenanthramides and phenolic acids, as reported by Szpicer et al. [44]. These compounds, although present at lower levels, can contribute to the overall antioxidant potential of composite cereal matrices.

In contrast, sauerkraut juice did not significantly affect TAA, which may be attributed to the degradation of its native phenolics during thermal treatment, as observed in studies by Lidiková et al. [70] and Kosewski et al. [71].

In summary, the results clearly indicate that microcapsules are the major determinant of the antioxidant capacity of the product, while oat fiber contributes moderately, and sauerkraut juice exerts no measurable influence under the tested conditions.

3.7. Total Flavonoid Content

According to the regression model, none of the tested formulation components showed a statistically significant linear or interaction effect on the TFC (p > 0.05). The model displayed good fit (R2 = 0.881; lack of fit p = 0.463), confirming that the variability observed in experimental data was adequately described.

Although the inclusion of microcapsules led to a slight, statistically insignificant increase in TFC, this effect was weaker compared to the enhancement observed for total polyphenols or antioxidant activity. This outcome may be related to the partial degradation of flavonoid compounds, as well as to the limited diffusion of encapsulated compounds from the microcapsule matrix into the product. Similar tendencies were noted by Kerbab et al. [72], who observed that while microencapsulation effectively preserves phenolic compounds, the measured flavonoid content in products does not always increase proportionally to the amount of added microcapsules due to encapsulation efficiency and matrix interactions.

The lack of significant effects from oat fiber and sauerkraut juice may be explained by the relatively low native flavonoid content of these materials and possible losses during processing. Studies by Gil et al. [73] and Purkiewicz et al. [74] confirmed that flavonoid retention in bakery products fortified with fiber or vegetable extracts is limited due to oxidative degradation and varied extractability after baking.

The results suggest that while the addition of microcapsules can slightly enhance flavonoid levels, the TFC is less responsive to formulation changes compared to total polyphenols or antioxidant activity, likely due to the lower stability of these compounds under processing conditions.

3.8. Vitamin C Content

The vitamin C content was significantly affected by the addition of microcapsules and sauerkraut juice (p ≤ 0.001), while oat fiber showed no significant linear effects (p > 0.05). The model exhibited excellent adequacy (R2 = 0.937; lack of fit p = 0.835), confirming that the relationship between the tested variables and vitamin C concentration was properly captured.

The positive influence of microcapsules on vitamin C content can be attributed to the protective effect of the encapsulation matrix, which reduces the degradation of thermolabile bioactive compounds. Microencapsulated forms are known to limit oxygen diffusion and thermal oxidation, allowing higher retention of both polyphenols and ascorbic acid [75,76].

The positive influence of sauerkraut juice reflects its direct contribution of ascorbic acid to the formulation. Despite potential losses during processing, the net effect in samples was a significant enrichment in vitamin C. The protective environment of the food matrix and possible interactions with other formulation components may have limited degradation, allowing measurable retention of ascorbic acid from the fermented juice [77,78].

Conversely, oat fiber had no measurable effect on vitamin C levels, as it primarily contributes structural carbohydrates and only trace amounts of antioxidant micronutrients [25].

Altogether, the data indicates that both sauerkraut (as a direct source) and microencapsulation (as a stabilizing strategy) improve the vitamin C content of the product. Despite the modest increase, it is noteworthy that conventional pasta contains no vitamin C, thus even small amount achieved through the combined use of fermented vegetable ingredients and encapsulated bioactives contribute to the nutritional enrichment of the product.

3.9. β-Glucan Content

The β-glucan content was significantly affected by the addition of both microcapsules (p ≤ 0.05) and oat fiber (p ≤ 0.001). The quadratic term for oat fiber was also significant (p ≤ 0.01), indicating that the effect of fiber addition was not strictly linear. The model showed very good fit (R2 = 0.982; lack of fit p = 0.143), confirming its high predictive reliability.

The strong positive influence of oat fiber on β-glucan content was expected, as it is the primary source of this bioactive polysaccharide in the formulation. Similar findings were reported by Astiz et al. [79] and Duta et al. [80], who demonstrated that the incorporation of oat-derived ingredients significantly increases the β-glucan fraction in cereal-based products. The non-linear relationship suggests that β-glucan concentration in the final product depends not only on the amount of added fiber but also on its hydration capacity and distribution within the dough matrix.

The slight positive effect of microcapsules may be related to the composition of the encapsulation material, which include polysaccharide carrier—maltodextrin—that interact with soluble fiber fractions [81]. However, this effect was considerably weaker than that observed for oat fiber.

In contrast, sauerkraut juice did not significantly affect β-glucan content (p > 0.05), which aligns with its composition—fermented vegetable juice contains negligible amounts of non-starch polysaccharides of the β-glucan type [82].

The results clearly confirm that oat fiber is the dominant source of β-glucan in the analyzed formulations, and its inclusion significantly enriches the product in this health-promoting dietary component. The observed quadratic response further emphasizes the importance of optimizing fiber dosage to balance nutritional enhancement and technological performance.

3.10. Volatile Organic Compounds

The results of the regression analysis showed that none of the analyzed factors—microcapsules, oat fiber, or sauerkraut juice—had a statistically significant effect on VOCs distances (p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant quadratic or interaction effects were observed. The relatively low determination coefficient (R2 = 0.492) and a significant lack of fit (p = 0.026) indicate that the model only partially explains the variability of volatile compound profiles, suggesting that aroma formation in pasta may depend on other uncontrolled factors, such as drying temperature or water activity.

Although the statistical results obtained did not reveal clear relationships, some tendencies can still be discussed. The inclusion of microcapsules led to changes in VOCs distances, reflecting their impact on the generation and stabilization of aroma compounds. This could be linked to the antioxidant capacity of encapsulated polyphenols, which inhibit lipid oxidation and, consequently, the generation of aldehydes and ketones responsible for off-flavors [83,84].

Similarly, oat fiber and sauerkraut juice tended to increase the variability of VOCs profiles, although also without statistical significance. Oat fiber, rich in non-starch polysaccharides, can modify the dynamics of the Maillard and lipid oxidation reactions by affecting water distribution and the availability of reducing sugars and amino acids during pasta drying. These processes may lead to changes in the concentrations of furan, aldehyde, and pyrazine derivatives responsible for roasted or toasted notes [60].

Likewise, sauerkraut juice, containing organic acids, fermentation metabolites, and residual volatiles, may introduce precursors that influence the formation of esters and alcohols during thermal treatment [85].

Nonetheless, while no statistically significant effects were confirmed, the observed tendencies suggest that the inclusion of enriching ingredients may modify the volatile composition by limiting the oxidation processes and contributing to a broader and more diverse aroma profile. The relatively low R2 value indicates that further GC–MS studies are necessary to better elucidate the mechanisms governing volatile compound formation in pasta matrices enriched with functional ingredients.

3.11. Consumers’ Acceptability

The regression analysis revealed that microcapsules (p ≤ 0.01) and oat fiber (p ≤ 0.001) significantly influenced consumer acceptance, while sauerkraut juice showed no significant effect (p > 0.05). Both the linear and quadratic terms for oat fiber were significant (p ≤ 0.001), indicating that the addition of fiber consistently reduced product acceptability. The model demonstrated excellent fit (R2 = 0.991; lack of fit p = 0.630), confirming its high predictive accuracy.

The negative influence of both microcapsules and oat fiber suggests that the inclusion of these functional ingredients led to a decrease in consumer acceptance. The decline in sensory scores can be attributed primarily to changes in color, texture, and mouthfeel, as both ingredients modify the product’s structure and visual appearance. The presence of dark-colored microcapsules increased ΔE*, resulting in a darker product, which may be perceived less favorably by consumers expecting the typical golden hue of pasta. Similar observations were reported by Bińkowska et al. [86] and Lachowicz et al. [57], who found that the inclusion of microencapsulated polyphenols reduced sensory desirability despite improving antioxidant potential of the product.

The addition of oat fiber, although beneficial from a nutritional standpoint, contributed to increased hardness and a denser structure. Excessive fiber content can decrease elasticity, as confirmed by Xu et al. [87] and Zbikowska et al. [88], leading to lower palatability scores at higher levels of enrichment.

In contrast, sauerkraut juice did not significantly affect consumer perception. Its addition likely introduced only subtle sensory changes, as the acidity and flavor of fermented juice were partially masked by the drying process. Studies by Raczyk et al. [89] reported that low concentrations of vegetable juices can be incorporated into bakery products without adversely affecting consumer preference.

In summary, while the inclusion of microcapsules and oat fiber enhances the functional value of the product, their excessive levels may compromise sensory appeal. Balancing technological and nutritional improvements with consumer acceptability remains a critical aspect of functional products development.

3.12. Overall Impact of Ingredients

The results obtained from the response surface methodology clearly demonstrate that all functional ingredients used in the formulation—microencapsulated polyphenols, oat fiber, and sauerkraut juice—exerted distinct and complementary effects on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of the product. Among the analyzed factors, polyphenol microcapsules had the most pronounced influence, significantly affecting viscosity, color, hardness, TPC, antioxidant activity, and vitamin C levels. Their incorporation enriched the product with bioactive compounds and enhanced antioxidant potential but also intensified color differences and increased texture firmness, which in turn slightly reduced consumer acceptance.

Oat fiber primarily contributed to changes in dough structure and texture, significantly increasing viscosity, hardness, and β-glucan content. Its presence improved the nutritional value of the product but negatively affected sensory perception when used in higher concentrations. The observed quadratic effects indicate the importance of optimizing fiber additions in balancing technological performance with consumer acceptability.

In contrast, sauerkraut juice had a limited influence on most parameters, showing only minor effects on color and no significant changes in antioxidant or textural properties. However, its inclusion did not adversely affect sensory characteristics, suggesting potential for its use as a mild functional additive or natural fermentation-based ingredient.

The results highlight the need for careful optimization of functional components in pasta formulations. While microcapsules and oat fiber markedly enhance the nutritional and antioxidant profile, their technological and sensory impacts must be managed to maintain desirable product quality. The combined use of these ingredients, supported by fermentation-based components such as sauerkraut juice, may offer a promising strategy for developing functional products with improved health-promoting properties and acceptable sensory attributes.

3.13. Verification of Formulation Optimization

The final stage of the study involved verification of the optimization model by comparing the predicted and experimental values of the responses obtained for the optimized pasta formulation. The optimized proportions of the ingredients were determined as 11.59% microcapsules, 6.12% oat fiber, and 11.93% sauerkraut juice. The predicted and experimental data are presented in Table 4 and show a high level of agreement, confirming the accuracy and adequacy of the developed model.

Table 4.

Optimized substitution levels for microcapsules, oat fiber, sauerkraut juice, and the comparison of predicted and experimental values of responses.

For complex viscosity (|η*|), the experimental value (10,955.41 ± 623.10 Pas) was very close to the predicted one (11,000.17 ± 598.19 Pas), indicating that the model reliably described the rheological behavior of the pasta dough. The obtained viscosity values were considerably higher than those typically observed for conventional pasta, suggesting that the inclusion of fiber and microcapsules increased the water-binding capacity and resistance of the dough to deformation.

The color difference (ΔE*) between the optimized and control samples was consistent with the predicted result (19.05 ± 0.82 vs. 19.18 ± 0.76). Although the color variation was perceptible, it remained within an acceptable range that does not adversely affect the visual quality of the product. The increase in ΔE* is primarily related to the presence of dark-colored polyphenol microcapsules and natural pigments from sauerkraut juice.

The hardness of the optimized pasta was in strong agreement with the predicted value (278.31 ± 18.90 g vs. 272.64 ± 21.12 g), confirming the validity of the model. The higher firmness compared to typical pasta formulations reflects the structural effect of oat fiber, which promotes a denser matrix, and the partial interference of microcapsules in the gluten–starch network formation.

The values of bioactive compounds were also very close to those predicted. The experimental TPC (127.81 ± 10.20 mg GA/100 g), TAA (34.12 ± 2.45%), TFC (28.10 ± 1.74 mg/100 g), and vitamin C (4.72 ± 0.31 mg/100 g) did not differ significantly from the predicted values, confirming the reliability of the optimization process and the model’s predictive capability. The agreement between the predicted and measured vitamin C content demonstrates that the contribution of sauerkraut juice was adequately captured by the model, confirming that its addition resulted in modest yet measurable enrichment of the final product.

Similarly, the β-glucan content (1.52 ± 0.21%) corresponded closely with the predicted value (1.47 ± 0.19%), indicating that the selected level of oat fiber ensured the intended nutritional enrichment.

The VOCs distance (−0.01 ± 0.01) matched the predicted value, confirming negligible differences in volatile compound profiles. This suggests that the addition of functional ingredients did not cause undesirable aroma changes.

The consumer acceptance score obtained experimentally (5.82 ± 0.33) also aligned with the predicted value (5.74 ± 0.35), confirming that the optimized formulation maintained satisfactory sensory properties despite the inclusion of fiber and microcapsules.

Overall, the minor differences between predicted and experimental values validate the accuracy and predictive performance of the optimization model. The use of polyphenol microcapsules, oat fiber, and sauerkraut juice effectively improved the nutritional and antioxidant characteristics of the pasta while maintaining its desirable technological and sensory quality.

4. Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that the use of RSM enabled the optimization of a functional pasta formulation enriched with polyphenol microcapsules, oat fiber, and sauerkraut juice. The optimized composition—containing 11.59% microcapsules, 6.12% oat fiber, and 11.93% sauerkraut juice—resulted in a product with high content of polyphenols, flavonoids, β-glucan, and vitamin C, as well as elevated antioxidant activity and consumer acceptability.

The incorporation of functional ingredients significantly improved the nutritional and bioactive profile of the pasta without compromising its technological properties. The addition of polyphenol microcapsules enhanced the content of health-promoting phenolic compounds and antioxidant potential, while oat fiber enriched the product with β-glucans, contributing to its dietary value. Sauerkraut juice acted as a natural source of vitamin C and fermentation-derived compounds, further increasing the product’s functional potential. Despite noticeable differences in color and texture compared to conventional pasta, these modifications did not negatively affect consumer perception, confirming the suitability of the optimized formulation.

From a technological perspective, the model proved to be highly accurate, as predicted and experimental values for key parameters such as viscosity, hardness, color difference, and antioxidant content were consistent. The resulting pasta showed stable structural characteristics, a balanced aroma profile, and acceptable sensory properties, demonstrating that RSM is an effective tool for designing functional cereal-based products.

In summary, the optimized pasta formulation combines desirable technological performance, nutritional enhancement, and consumer appeal. The incorporation of natural, bioactive-rich ingredients positions this product within the growing market for functional foods, meeting current consumer demands for products that support health and well-being. Such an approach enables the development of innovative pasta with added health benefits, offering an attractive alternative to traditional products and contributing to a more balanced, antioxidant-rich diet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B.; methodology, W.B.; investigation, W.B.; resources, W.B. and A.S. (Adrian Stelmasiak); data curation, W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.B. and A.S. (Arkadiusz Szpicer); writing—review and editing, W.B., A.S. (Arkadiusz Szpicer) and I.W.-K.; visualization, W.B.; supervision, A.S. (Arkadiusz Szpicer) and A.P.; project administration, W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research financed by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within funds of Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences (WULS), for scientific research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Warsaw University of Life Sciences-SGGW (protocol code 28/RKE/2024/U, from 5 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TAA | Total Antioxidant Activity |

| TFC | Total Flavonoid Content |

| TPC | Total Polyphenol Content |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Taşcı, R.; Karabak, S.; Özercan, B.; Bolat, M.; Candemir, S.; Kaplan Evlice, A.; Arslan, S.; Sarı, G. Investigation of Pasta Consumption Habits in Türkiye. Int. J. Innov. Approaches Agric. Res. 2023, 7, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Suardi, A.; Stefanoni, W.; Pari, L. Opuntia Ficus-Indica as an Ingredient in New Functional Pasta: Consumer Preferences in Italy. Foods 2021, 10, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raczyk, M.; Polanowska, K.; Kruszewski, B.; Grygier, A.; Michałowska, D. Effect of Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) Supplementation on Physical and Chemical Properties of Semolina (Triticum durum) Based Fresh Pasta. Molecules 2022, 27, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, O.M.; van Stuijvenberg, L.; Boon, N.; Awolu, O.; Fogliano, V.; Linnemann, A.R. Technological and Nutritional Properties of Amaranth-Fortified Yellow Cassava Pasta. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 5213–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, C.; Laureati, M.; Casiraghi, M.C.; Erba, D.; Vezzani, M.; Lucisano, M.; Alamprese, C. Effects of Red Rice or Buckwheat Addition on Nutritional, Technological, and Sensory Quality of Potato-Based Pasta. Foods 2021, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.M.; Slavin, J. Impact of Pasta Intake on Body Weight and Body Composition: A Technical Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pede, G.; Dodi, R.; Scarpa, C.; Brighenti, F.; Dall’asta, M.; Scazzina, F. Glycemic Index Values of Pasta Products: An Overview. Foods 2021, 10, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavaroli, L.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Braunstein, C.R.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Leiter, L.A.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Effect of Pasta in the Context of Low-Glycaemic Index Dietary Patterns on Body Weight and Markers of Adiposity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials in Adults. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Masulli, M.; Rivellese, A.A.; Bonora, E.; Babini, A.C.; Sartore, G.; Corsi, L.; Buzzetti, R.; Citro, G.; Baldassarre, M.P.A.; et al. Pasta Consumption and Connected Dietary Habits: Associations with Glucose Control, Adiposity Measures, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in People with Type 2 Diabetes—TOSCA.IT Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierońska, E.; Skoczylas, J.; Dziadek, K.; Pomietło, U.; Piątkowska, E.; Kopeć, A. Basic Chemical Composition, Selected Polyphenolic Profile and Antioxidant Activity in Various Types of Currant (Ribes spp.) Fruits. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bińkowska, W.; Szpicer, A.; Stelmasiak, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A. Microencapsulation of Polyphenols and Their Application in Food Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushalya, K.G.D.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Health Benefits of Microencapsulated Dietary Polyphenols: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 2079–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimestad, R.; Solheim, H. Anthocyanins from Black Currants (Ribes nigrum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3228–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Laaksonen, O.; Haikonen, H.; Vanag, A.; Ejaz, H.; Linderborg, K.; Karhu, S.; Yang, B. Compositional Diversity among Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) Cultivars Originating from European Countries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5621–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, A.; Waliat, S.; Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, A.; Din, A.; Ateeq, H.; Asghar, A.; Abbas, Y.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Biological Activities, Therapeutic Potential, and Pharmacological Aspects of Blackcurrants (Ribes nigrum L.): A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5799–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejnik, A.; Kowalska, K.; Olkowicz, M.; Juzwa, W.; Dembczyński, R.; Schmidt, M. A Gastrointestinally Digested Ribes nigrum L. Fruit Extract Inhibits Inflammatory Response in a Co-Culture Model of Intestinal Caco-2 Cells and RAW264.7 Macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 7710–7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakowska-barczak, A.M.; Kolodziejczyk, P.P. Black Currant Polyphenols: Their Storage Stability and Microencapsulation. Ind. Crops Products 2011, 34, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Dussling, S.; Nowak, A.; Zimmermann, L.; Bach, P.; Ludwig, M.; Kumar, K.; Will, F.; Schweiggert, R.; Steingass, C.B.; et al. Investigations into the Stability of Anthocyanins in Model Solutions and Blackcurrant Juices Produced with Various Dejuicing Technologies. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Xie, K.; Liao, X.; Tan, J. Factors Affecting the Stability of Anthocyanins and Strategies for Improving Their Stability: A Review. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, J.; Koh, E. Effects of Four Different Cooking Methods on Anthocyanins, Total Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity of Black Rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 3296–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, R.; Kamil, A.; Chu, Y.F. Global Review of Heart Health Claims for Oat Beta-Glucan Products. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Singh, A.; Ashraf, M.T. Avenanthramides of Oats: Medicinal Importance and Future Perspectives. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2018, 12, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, E.C.; Witlaczil, R.; Hofinger-Horvath, A.; Jágr, M.; Čepková, P.H.; D’Amico, S.; Grausgruber, H.; Dvořáček, V.; Schönlechner, R. Phenolic Compounds, Including Avenanthramides, and Antioxidant Properties in Conventionally and Organically Grown Oat Cultivars Affected by Germination. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 23, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, L. The Positive Correlation of Antioxidant Activity and Prebiotic Effect About Oat Phenolic Compounds. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz de Erive, M.; He, F.; Wang, T.; Chen, G. Development of β-Glucan Enriched Wheat Bread Using Soluble Oat Fiber. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 95, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, B.; Dziki, D.; Różyło, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Nowak, R.; Pietrzak, W. Common Wheat Pasta Enriched with Ultrafine Ground Oat Husk: Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzauddula, M.; Hossain, M.B.; Farzana, T.; Orchy, T.N.; Islam, M.N.; Hasan, M.M. Incorporation of Oat Flour into Wheat Flour Noodle and Evaluation of Its Physical, Chemical and Sensory Attributes. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2021, 24, e2020252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Brennan, M.A.; Brennan, C.S.; Serventi, L. Effect of Vegetable Juice, Puree, and Pomace on Chemical and Technological Quality of Fresh Pasta. Foods 2021, 10, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Brennan, M.A.; Serventi, L.; Brennan, C.S. Impact of Functional Vegetable Ingredients on the Technical and Nutritional Quality of Pasta. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6069–6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Van Beeck, W.; Hanlon, M.; Dicaprio, E.; Marco, M.L. Lacto-Fermented Fruits and Vegetables: Bioactive Components and Effects on Human Health. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, N.; Bažon, I.; Išić, N.; Kovacevć, T.K.; Ban, D.; Radeka, S.; Ban, S.G. Bioactive Properties, Volatile Compounds, and Sensory Profile of Sauerkraut Are Dependent on Cultivar Choice and Storage Conditions. Foods 2022, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penas, E.; Frias, J.; Sidro, B.; Vidal-Valverde, C. Chemical Evaluation and Sensory Quality of Sauerkrauts Obtained by Natural and Induced Fermentations at Different NaCl Levels from Brassica Oleracea Var. Capitata Cv. Bronco Grown in Eastern Spain. Effect of Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, E.; Kadac-Czapska, K.; Grembecka, M. Effect of Fermentation on the Nutritional Quality of the Selected Vegetables and Legumes and Their Health Effects. Life 2023, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansone, L.; Kruma, Z.; Straumite, E. Evaluation of Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Sauerkraut Juice Powder and its Application in Food. Foods 2023, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkraus, K.H. Lactic Acid Fermentations. In Applications of Biotechnology in Traditional Fermented Foods; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 43–51. ISBN 0309565758. [Google Scholar]

- Mehran, M.; Masoum, S.; Memarzadeh, M. Improvement of Thermal Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Anthocyanins of Echium Amoenum Petal Using Maltodextrin/Modified Starch Combination as Wall Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćetković, G.; Šeregelj, V.; Brandolini, A.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Vulić, J.; Šovljanski, O.; Četojević-Simin, D.; Škrobot, D.; Mandić, A.; et al. Composition, Texture, Sensorial Quality, and Biological Activity After In Vitro Digestion of Durum Wheat Pasta Enriched with Carrot Waste Extract Encapsulates. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeregelj, V.; Škrobot, D.; Kojić, J.; Pezo, L.; Šovljanski, O.; Šaponjac, V.T.; Vulić, J.; Hidalgo, A.; Brandolini, A.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; et al. Quality and Sensory Profile of Durum Wheat Pasta Enriched with Carrot Waste Encapsulates. Foods 2022, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, M.C.; Ramos, I.; Perez, G.T.; Leon, A.E. Utilization of Kañawa (Chenopodium pallidicaule Aellen) Flour in Pasta Making. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 4385045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, S.; Jones, S.; Ye, S.; Sancho-madriz, M.; Burns-whitmore, B.; Li, Y.O. Effect of Selected Dietary Fibre Sources and Addition Levels on Physical and Cooking Quality Attributes of Fibre-Enhanced Pasta. Food Qual. Saf. 2019, 3, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, M.N.; Chauhan, A.S.; Prabhasankar, P.; Ramteke, R.S.; Venkateswara Rao, G. Influence of Vegetable Purees on Quality Attributes of Pastas Made from Bread Wheat (T. aestivum). CyTA-J. Food 2013, 11, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Kaur, R.; Janghu, S.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, P.; Chhikara, N. Nutritional, Phytochemical, Functional and Sensorial Attributes of Syzygium cumini L. Pulp Incorporated Pasta. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradinho, P.; Raymundo, A.; Sousa, I.; Dominguez, H.; Torres, M.D. Edible Brown Seaweed in Gluten-Free Pasta: Technological and Nutritional Evaluation Patrícia. Foods 2019, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szpicer, A.; Onopiuk, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A. Red Grape Skin Extract and Oat β-Glucan in Shortbread Cookies: Technological and Nutritional Evaluation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1999–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Ho, C.T.; Patiguli, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, B.; Zhang, C.; Aadil, R.M.; Qu, W.; Xiao, R.; et al. Addition of Chlorophyll Microcapsules to Improve the Quality of Fresh Wheat Noodles. LWT 2023, 183, 114940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bińkowska, W.; Szpicer, A.; Stelmasiak, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A. Innovative Application of Microencapsulated Polyphenols in Cereal Products: Optimization of the Formulation of Dairy- and Gluten-Free Pastry. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Onopiuk, A.; Szpicer, A.; Wierzbicka, A.; Półtorak, A. Frozen Storage Quality and Flavor Evaluation of Ready to Eat Steamed Meat Products Treated with Antioxidants. CYTA-J. Food 2021, 19, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onopiuk, A.; Półtorak, A.; Moczkowska, M.; Szpicer, A.; Wierzbicka, A. The Impact of Ozone on Health-Promoting, Microbiological, and Colour Properties of Rubus Ideaus Raspberries. CYTA-J. Food 2017, 15, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S.; Chiș, T.-Ș.; Chiricuţă, M.G.; Vârlan, A.-C.; Pîrvulescu, L.; Velciov, A. Vitamin C Determination in Foods. Titrimetric Methods—A Review. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2024, 30, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpicer, A.; Onopiuk, A.; Półtorak, A.; Wierzbicka, A. The Influence of Oat β-Glucan Content on the Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Low-Fat Beef Burgers. CYTA-J. Food 2020, 18, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Guzek, D.; Górska-Horczyczak, E.; Głabska, D.; Brodowska, M.; Sun, D.W.; Wierzbicka, A. Volatile Compounds and Fatty Acids Profile in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle from Pigs Fed with Feed Containing Bioactive Components. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renoldi, N.; Lucci, P.; Peressini, D. Impact of Oleuropein on Rheology and Breadmaking Performance of Wheat Doughs, and Functional Features of Bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2321–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.L.; Awika, J.M. Effects of Edible Plant Polyphenols on Gluten Protein Functionality and Potential Applications of Polyphenol–Gluten Interactions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2164–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A.S.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Quek, S.; Perera, C.O. Physicochemical Properties of Bread Dough and Finished Bread with Added Pectin Fiber and Phenolic Antioxidants. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, H97–H107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lante, A.; Canazza, E.; Tessari, P. Beta-Glucans of Cereals: Functional and Technological Properties. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono, D.M.; Gilissen, L.J.W.J.; Visser, R.G.F.; Smulders, M.J.M.; Hamer, R.J. Understanding the Role of Oat β-Glucan in Oat-Based Dough Systems. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]