Abstract

Frozen storage modulates the progression of key oxidative and nitrogenous reactions within fish muscle. We therefore identify the drivers of quality degradation in filleted whiting (Merlangius merlangus) and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda) during 10-month frozen storage at −12, −18, and −24 °C, and to integrate state-of-the-art machine learning architectures to predict deterioration kinetics and shelf-life trajectories. To this end, following blast freezing at −30 °C for 6 h, samples were periodically (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 months) assessed for biochemical indices—total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N), trimethylamine nitrogen (TMA-N), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and free fatty acids (FFA)—in which proximate composition and pH were determined solely on the same day (Day 0). Whiting displayed progressive increases in all indices, yet values at −24 °C remained within regulatory acceptability, supporting a safe storage period of up to nine months. By contrast, Atlantic bonito retained TVB-N and TMA-N values below regulatory thresholds across storage, but TBA exceeded acceptability limits from the second month onward, and FFA rose after month four. Complementing these findings, machine learning (ML) approaches, including Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machine, Decision Tree, Multilayer Perceptron, and Extreme Gradient Boosting, were implemented to classify species and predict spoilage kinetics, with Extreme Gradient Boosting achieving the highest accuracy (98.9%, κ = 0.978) and Random Forest providing superior regression performance (R2 = 0.986, RMSE = 0.392). ML models consistently identified TVB-N as the dominant predictor for whiting and TBA for Atlantic bonito, correctly capturing the critical time points of 9 months and 2 months, respectively, and highlighting −24 °C as the most reliable condition for preserving quality. These results underscore the potential of ML as a transformative tool for accurate shelf-life prediction and smarter cold-chain management in frozen fish products.

1. Introduction

Safeguarding fish quality throughout frozen storage is hindered by the inherent fragility of aquatic muscle, as post-harvest lipid oxidation, protein denaturation, and enzymatic activity progressively compromise structural integrity, curtail shelf life, and diminish sensory attributes [1]. A growing body of review literature emphasizes that quality outcomes during storage are multifactorial, shaped by intrinsic factors such as species, post-mortem physiology [2], and muscle composition, as well as extrinsic parameters including freezing rate, packaging conditions, and salting or glazing practices [3,4,5].

Foundational investigations established that freezing prolongs shelf life mainly by slowing, rather than fully stopping, enzymatic and oxidative spoilage—an observation first emphasized by Varlık [6] and later expanded by Sikorski and Pan [7]. The importance of raw-material freshness and rigor mortis timing for long-term stability was highlighted by Licciardello [8], while studies by Göğüş and Kolsarıcı [9], Uzunkuşak [10], and Gülyavuz and Ünlüsayın [11] demonstrated that slow freezing forms large extracellular ice crystals that damage cell membranes, a concept later confirmed by French et al. [12] for salmonid species. Subsequent research showed that lipid-rich fish require lower storage temperatures to suppress oxidation, as outlined by Ludorff and Meyer [13] and Khayat and Schwall [14], while Shamberger et al. [15] and Hultin [16] characterized the oxidative cascade leading to aldehyde and malonaldehyde formation [17]. Residual lipoxygenase and microsomal enzymes retain partial activity even at subzero temperatures, sustaining lipid and pigment oxidation [18,19,20]. In parallel, protein denaturation, reduced water-holding capacity, and textural weakening have been attributed to freeze-concentration effects [11], salt-induced precipitation [21], and oxidative interactions between lipids and muscle proteins [22,23]. These mechanisms appear particularly pronounced in lean fish, where structural proteins undergo irreversible damage during prolonged frozen storage [24,25]. Empirical evidence across species demonstrates that deterioration persists even under subzero conditions, with moderate freezing permitting continued volatile-nitrogen formation, whereas deep-freezing decisively suppresses lipid oxidation in PUFA-rich tissues, underscoring the dominant role of temperature in governing oxidative pathways [26,27,28]. Although −18 °C remains the industry standard, accumulated evidence shows that time–temperature history, rather than the nominal storage temperature alone, ultimately governs sensory and biochemical stability [29]. Differences in species composition and processing state also modulate deterioration patterns. Matrix characteristics influence hydrolytic and oxidative reactions, with some species exhibiting rising FFA levels despite stable total lipid content during long-term storage [30]. Processing intensity further amplifies degradation, as comminuted muscle accelerates oxidation and volatile-base formation due to increased surface exposure and disrupted cellular structure [31]. Even under vacuum, oxidative pathways persist over extended storage, indicating that packaging can slow—but not eliminate—quality loss [32]. Comparative analyses have also underscored pronounced species- and tissue-level variability in oxidative and proteolytic stability. Early work by Fazal and Srikar [33] and Varlık and Yolcular [34] highlighted the heightened vulnerability of lipid-rich pelagic fish, while Vareltzis et al. [35] and French et al. [12] linked oxidation rates directly to muscle type and fatty-acid composition, with red-muscle and PUFA-rich species displaying markedly lower stability than lean, white-muscle matrices. Phospholipid hydrolysis has been identified as a major pathway of quality loss in several species, including catfish [36]. Cross-study syntheses further demonstrate tight coupling between protein denaturation [37] and lipid degradation [38,39,40], with most taxa showing progressive increases in TBA and TVB-N indices during frozen storage [19,20,41]. Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda), a histidine-rich Scombridae species, presents heightened susceptibility to oxidation and histamine-related quality risks in frozen seafood [42]. By contrast, the leaner whiting (Merlangius merlangus) displays the deterioration pattern characteristic of Gadidae, shaped by robust enzymatic activity and heightened microbial vulnerability, making their comparative evaluation especially instructive [43]. Structural investigations have mapped irreversible myofibrillar alterations—such as reduced solubility, diminished water-holding capacity, and textural hardening—as key contributors to quality decline [43,44,45]. Species- and protocol-specific comparisons, spanning studies by Baygar et al. [46], Aubourg et al. [47], and Puchata et al. [48], reinforce that fat content, pre-freezing handling, and freezing profile (rate and endpoint temperature) jointly modulate oxidative kinetics. Evidence from North Atlantic species further indicates that both oxidative and proteolytic reactions persist even under well-controlled subzero storage, with susceptibility strongly linked to lipid content and muscle type [49]. Pelagic species tend to be especially prone to hydrolysis and oxidation [50], and comminution accelerates deterioration by increasing tissue exposure and disrupting cellular integrity [51]. Reviews consistently confirm that whole fish retain quality longer than processed forms due to intact anatomical barriers [4,52,53]. Complementary studies affirm the multifactorial character of frozen-storage instability, marked by simultaneous rises in enzymatic activity, lipid oxidation, and volatile nitrogen formation across diverse taxa [54,55,56]. Lipid oxidation constitutes the primary axis of quality loss in fatty species [57], and oxidative stress–driven protein denaturation is particularly pronounced in tropical fishes [58]. This convergence of processes defines the biochemical triad of frozen-storage deterioration articulated by Wang et al. [59].

As biochemical understanding deepened, research pivoted toward predictive frameworks capable of converting degradation kinetics into quantitative forecasts, marking a transition from descriptive frozen storage science to real-time, sensor-driven quality assessment. Shelf-life models linking degradation kinetics to constant and fluctuating regimes offer tools to predict quality loss in dynamic cold chains [60]. At this juncture, ML has emerged as a powerful complement to kinetic models, capturing nonlinear and multivariate interactions by constructing flexible, data-driven mappings between variables rather than relying on predefined functional forms, as in conventional Arrhenius-type or regression-based models. Through iterative optimization, they learn latent structures within complex datasets, enabling the identification of subtle dependencies and interaction effects that traditional kinetic frameworks are inherently unable to represent, and this conceptual advancement has been substantiated by empirical studies. Early implementations, such as the radial basis function neural networks developed by Kong et al. [61] and later expanded to incorporate lipid and protein degradation dynamics in frozen carp [62], demonstrated the feasibility of ML-based quality prediction. Comparable results have been reported for shrimp using both RBFNN and Arrhenius-based formulations [63,64]. Non-destructive sensing modalities—e-nose, e-tongue, colorimetry, UV-induced fluorescence, and hyperspectral imaging—have further broadened predictive capacity, enabling freshness estimation, thawing classification, and quality mapping across species such as horse mackerel, tilapia, and mackerel [65,66,67]. Additional advances include MRI-based visualization of structural damage [68], NIR-based histamine detection [69], and chemometric verification of whitefish authenticity [70]. More complex AI architectures, including neural networks [71], backpropagation frameworks [72], and random forests [73], have been used to forecast storage time, classify shelf-life stages, and model deterioration across diverse taxa. Emerging deep-learning methods—transformer models [74], multimodal spectral fusion [75], and bioimpedance-based classification [76]—further highlight the expanding analytical capability of AI in frozen-seafood quality evaluation. Ultrasound-assisted ML protocols have been validated for tuna freshness [77], while LSTM architectures have shown superiority in discriminating frozen–thawed fillets filets [78]. In parallel, digital traceability frameworks are redefining cold chain governance [79], and recent developments extend beyond biochemical indices, incorporating blockchain-enabled traceability, SVM-based monitoring of cold chains [80,81], fuzzy-logic integration with oxidative markers [82,83], microstructural predictors of freezing damage [84], and explainable AI combined with NIR spectroscopy for transparent shelf-life estimation [85].

A decisive shift is underway from classical, linear kinetic interpretations to predictive, data-driven paradigms that unify biochemical indices with advanced sensing and AI-enabled traceability. In line with this paradigm shift, the present study addresses whether routinely measured biochemical indicators can be reinterpreted as multivariate predictors of quality deterioration through supervised ML architectures. This framework relinquishes predefined functional assumptions, enabling nonlinear dependencies and cross-interactions among variables to emerge intrinsically from empirical data. In this approach, conventional biochemical assays—specifically TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, and FFA—were quantified and employed as independent variables to train, validate, and interpret predictive models, thereby establishing a transparent link between empirical measurements and computational inference. Positioning routine indices as dynamic predictors yields an adaptive computational framework for forecasting quality trajectories, advancing frozen-storage science toward a predictive, data-intelligent paradigm that complements traditional kinetic models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Dataset for Computational Analyses

The experimental design was conceived to systematically assess quality deterioration in filletedfileted whiting and Atlantic bonito subjected to long-term frozen storage under different thermal regimes. Fresh specimens of both species were, portioned, and subjected to blast freezing at −30 °C for 6 h to ensure rapid stabilization of tissues prior to storage. Subsequently, samples were distributed into storage groups maintained at −12, −18, and −24 °C, and monitored over a 10-month period. A comprehensive longitudinal dataset was generated encompassing physicochemical (proximate composition and pH) as well as biochemical quality markers—total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N), trimethylamine nitrogen (TMA-N), thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and free fatty acids (FFA). This dataset served as the empirical foundation for both statistical interrogation and computational modeling of quality degradation kinetics and shelf-life prediction. All determinations were conducted in six independent replicates (n = 6).

2.2. Raw Material and Sample Preparation

Fresh whiting (Merlangius merlangus Linnaeus, 1758) and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda Bloch, 1793) were obtained approximately 12 h post-harvest from the central fish market in Ankara, Türkiye. A total of 360 whiting and 36 bonito were utilized, exhibiting mean body weights of 94.49 ± 10.70 g and 962.49 ± 70.69 g, respectively. To ensure comparable total biomass across species (approximately 34 kg per group), the number of fish per sample was proportionally adjusted to individual body weight. They were transported in polystyrene boxes layered with crushed ice and transported to the laboratory within one hour. Upon arrival, they were eviscerated and manually filleted during the rigor mortis phase to minimize post-mortem degradation. Fillets were gently rinsed with chilled tap water, individually placed on polystyrene trays (18 × 26 cm), and sealed with a 10 μm stretch film. Packaged samples were subsequently subjected to blast freezing and stored for 10 months (300 days) under the designated freezing regimes. Analytical sampling was performed at baseline (month 0) and at 2-month intervals (months 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10). At each time point, one package from each treatment group was withdrawn and thawed overnight at +4 °C prior to analysis. The individual packages contained approximately 1.89 kg and 1.93 kg for whiting and Atlantic bonito, respectively, thereby ensuring standardized batch weights for comparative evaluation.

2.3. Physicochemical Analyses

Fillet samples were analyzed for proximate composition, including moisture, crude ash, crude protein, and crude fat, according to AOAC (1995) standart procedures [86]. Moisture content was determined by oven-drying at 105 °C for 24 h, whereas crude ash was quantified by combustion in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 4 h. Crude protein content (N × 6.25) was measured using the Kjeldahl distillation method (Kjeltec System, Tecator, Höganäs, Sweden), and crude fat was extracted with petroleum ether using the Soxhlet method (Soxtec System HT, Tecator, Höganäs, Sweden). The pH of muscle tissue was assessed following Varlık et al. [87], using 10 g of minced and homogenized fillet, with measurements performed on a Consort NV P901 pH meter (Turnhout, Belgium).

2.4. Biochemical Analyses

2.4.1. Determination of Total Volatile Basic-Nitrogen (TVB-N)

TVB-N was quantified following the procedure of Pearson and Cox [88] using a Kjeldahl distillation system. For each analysis, 10 g of homogenized sample was transferred into a Kjeldahl flask, supplemented with 2 g of magnesium oxide and 350 mL of distilled water. To minimize foaming, liquid paraffin and boiling stones were added prior to mounting the flask on the distillation unit. Volatile bases were distilled for 25 min, beginning at the onset of boiling, and collected in an erlenmeyer flask containing 25 mL of 2% boric acid solution with methyl red as the indicator. A reagent blank was prepared under identical conditions using only boric acid. The distillates were titrated with standardized 0.1 N sulfuric acid (H2SO4), and TVB-N values were calculated and expressed as mg per 100 g of sample.

2.4.2. Determination of Trimethylamine-Nitrogen (TMA-N)

For the determination of TMA-N, 100 g of homogenized sample was extracted with 200 mL of 7.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 2000–3000 rpm until the supernatant became clear. Aliquots of extract (1–4 mL, adjusted to 4 mL with distilled water) were transferred into Pyrex tubes. Standard curves were prepared with trimethylammonium hydrochloride solutions (0.01 mg/mL) at 1–3 mL dilutions, alongside a distilled water blank. Each tube received 1 mL of 20% formaldehyde, 10 mL of toluene, and 3 mL of saturated potassium carbonate, followed by vigorous shaking and layering with 0.1 g anhydrous sodium sulfate. The toluene layer was collected, mixed with 5 mL of 0.02% picric acid, and gently rotated. Absorbance was recorded at 410 nm against the blank using a Shimadzu UV–1201 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan) and TMA-N values were calculated and expressed as mg per 100 g sample [86].

2.4.3. Determination of Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA)

TBA values were determined following the method of Tarladgis et al. [89] with a Kjeldahl distillation apparatus. Briefly, 10 g of sample was homogenized with 50 mL of distilled water for 2 min using an IKA T 25 Ultraturrax homogenizer (Staufen, Germany). The homogenate was transferred to a Kjeldahl flask containing an additional 47.5 mL of distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 1.5 by adding 2.5 mL of 4 N hydrochloric acid (HCl). To suppress foaming, boiling stones and a small volume of liquid paraffin were introduced before mounting the flask on the distillation unit. Volatile compounds were distilled for 10 min, yielding approximately 50 mL of distillate, which was collected in a 50 mL erlenmeyer flask. Aliquots (5 mL) of the distillate were combined with 5 mL of 0.02 M TBA reagent in test tubes, while blanks were prepared simultaneously with distilled water and reagent. The tubes were sealed, vortexed, and incubated in a boiling water bath for 35 min, then rapidly cooled under running tap water. Absorbance was recorded at 532 nm against the reagent blank using a Shimadzu UV–1201 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan). Final TBA values were determined by multiplying the sample absorbance (A) by 7.8, a conversion factor derived from the molar extinction coefficient of the MDA–TBA complex and the standard sample preparation volume. The calculation was performed according to the following relationship: TBA (mg MA/kg sample) = A × 7.8, and the results were expressed as milligrams of malondialdehyde (MDA) per kilogram of sample.

2.4.4. Determination of Free Fatty Acids (FFA)

FFA were analyzed according to AOAC [86] after lipid extraction by the cold method of Bligh and Dyer [90]. Minced tissue (25 g) was homogenized with anhydrous sodium sulfate and 45 mL of chloroform–methanol (2:1, v/v) using an Ultraturrax, filtered, and re-extracted twice. The combined filtrates were separated, and the chloroform–lipid layer was collected, evaporated under Heidolph Laborota 4011-digital rotary evaporator (Schwabach, Germany), and weighed. Approximately 5 g of the extracted lipid was dissolved in 50 mL of pre-warmed neutralized ethanol and titrated with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in the presence of phenolphthalein. FFA content expressed as % oleic acid, was determined by multiplying the difference between the titration and blank volumes (V2 − V1) by the normality of the NaOH solution (N) and the milliequivalent weight of oleic acid (28.2), and dividing the product by the weight of the oil sample (Y).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from six replicates per treatment (n = 6). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 26.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among storage temperatures and durations were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where significant differences were identified (p < 0.05), pairwise comparisons among means were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test to delineate homogeneous subsets. In addition, descriptive statistics including minimum, maximum, mean, median, variance, skewness, and kurtosis were calculated to characterize the distributional properties of the biochemical parameters.

These measures were computed following standard definitions provided in statistical literature [91,92,93].

2.6. Machine Learning (ML) Modeling

2.6.1. Dataset Preparation

The ML modeling dataset included biochemical indicators (TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA and FFA), storage temperature, and storage duration as predictive variables, with fish species (Merlangius merlangus and Sarda sarda) used as the target classes.

The modeling framework consisted of two complementary ML tasks: a classification task and a regression task. In the classification task, the aforementioned biochemical indicators, storage temperature, and duration were used as input features to classify samples according to fish species (Merlangius merlangus and Sarda sarda). This task was not intended for species authentication or food fraud detection but rather to assess whether spoilage-related biochemical patterns can distinguish between species with different degradation kinetics. The regression task, in turn, used the same biochemical indicators to predict storage duration, thereby quantifying the progression of biochemical spoilage under varying freezing conditions.

Each instance denotes an independent biochemical observation (TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, FFA) obtained from a biological or analytical replicate under a specific temperature × storage-duration condition for a given species. Six replicates were analyzed per condition, and each replicate yielded a distinct biochemical profile characterized by unique predictor values; therefore, replicate measurements were treated as independent observations in the modeling process. This approach follows established practices in experimental modeling, where independently measured replicates may be regarded as discrete data instances when they capture biological or analytical variability rather than technical noise [94,95].

Before oversampling, the dataset included 450 samples of Sarda sarda (bonito) and 370 samples of Merlangius merlangus (whiting). To mitigate the moderate class imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied within each training fold of the 10-fold cross-validation to prevent data leakage between training and validation sets. This procedure increased the number of minority-class (whiting) samples, yielding a total of 900 instances used for model development [96]. All input features were standardized using z-score normalization prior to model training to ensure comparability across variables [97].

All analyses were conducted in Python 3.10 using scikit-learn 1.3.1 and XGBoost 1.7.6, with the random seed fixed at 42 to ensure reproducibility.

2.6.2. Implemented Algorithms

Eight supervised learning algorithms encompassing both classification and regression paradigms were implemented to analyze fish quality and shelf-life. For classification, Naïve Bayes (NB), a probabilistic classifier, was applied due to its simplicity and persistence [98]. Support Vector Machine (SVM) was employed for its proficiency in nonlinear classification in high-dimensional spaces [99]. Decision Tree (DT) was selected for its rule-based interpretability and its common application in food authenticity and quality evaluation [100]. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), a feed-forward artificial NN, was utilized to approximate intricate nonlinear relationships [101]. Lastly, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), an ensemble boosting method, was included for its superior performance and computational efficiency in tabular data [102].

To predict storage duration and model the influence of frozen storage conditions on shelf-life, three regression approaches were further employed. Simple Regression Tree (SRT) was used for its ease of interpretation and ability to derive intuitive decision rules for predicting storage time from biochemical markers. Polynomial Regression (PR) was implemented to capture curvilinear relationships between biochemical indicators and storage duration, reflecting nonlinear deterioration trends [103]. Finally, Random Forest Regression (RFR), an ensemble of decision trees, was applied for its robustness against overfitting and strong capability to model complex nonlinear interactions [104]. In aggregate, these algorithms enabled both classification of fish species and prediction of shelf-life trajectories under different frozen storage conditions.

2.6.3. Hyperparameter Optimization

Hyperparameter tuning for each algorithm was conducted using a grid search approach combined with 10-fold cross-validation on the training data. Candidate hyperparameter ranges were defined based on prior studies in predictive modeling, and the optimal values were selected according to the highest mean F1-score for classification tasks and the lowest RMSE for regression tasks. The final model hyperparameters presented below correspond to the best-performing configurations obtained through this tuning process.

To increase predictive performance, particular hyperparameters were adjusted for each algorithm. In NB, the default probability and minimum SD were established at 0.0001, whereas the threshold SD was maintained at 0.0 to stabilize features with low variance.

The SVM was set up with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel, employing a sigma (γ) value of 2.7, which optimizes margin maximization and misclassification reduction in nonlinear feature spaces [99].

The MLP was trained using a single hidden layer comprising 10 neurons. The iteration limit was set at 100, facilitating convergence and reducing the risk of overfitting. This architecture was selected as a foundational shallow NN, proficient in capturing nonlinear relationships without incurring substantial computational expenses [101].

The DT classifier utilized the Gini index as the quality metric, with reduced error pruning activated to prevent overfitting. The minimum record count per node was established at 2, and average split points were employed to enhance generalization.

The XGBoost algorithm was trained with a binary logistic objective. The feature space comprised TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, FFA, temperature, and storage duration. Boosting was executed for 100 iterations, utilizing a base score of 0.5 and six computational threads, thereby improving computational efficiency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Model-specific hyperparameters.

2.6.4. Model Training and Validation

Model training used divided 10-fold cross-validation (CV) to reduce overfitting and provide robust generalization [105]. The dataset was randomly divided into 10 equal folds, maintaining the class distribution within each fold. In each iteration, nine folds were utilized for training while the remaining fold was allocated for testing; this procedure was repeated ten times, ensuring that each fold functioned as the validation set once. The model’s overall performance was quantified as the arithmetic mean of the results obtained from all folds, yielding a more dependable estimate than a singular train-test split.

The CV error can be formally expressed as:

where is the number of folds (here, ), and errori represents the prediction error on the -th fold.

Hyperparameters for each algorithm were optimized within CV folds. All machine learning workflows were implemented in Python using Scikit-learn [102,106].

The predictive performance of the machine learning models was evaluated using a thorough array of classification metrics, including accuracy (ACC), precision (P), recall (R), F1-score (F1), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), which are established benchmarks in the assessment of supervised learning [107]. The Kappa coefficient (κ) is a statistical measure of concordance between two evaluators. The Kappa test is regarded as a more robust measure than the concordance observed between the two evaluators, as it accounts for the possibility that the agreement may occur by chance.

ACC was calculated as the ratio of correctly classified instances.

P, or positive predictive value (PPV), quantifies the proportion of accurately identified positive cases:

R, also known as sensitivity, denotes the proportion of true positives accurately recognized.

The F1-score denotes the harmonic mean of P and R, equilibrating both metrics.

The AUC-ROC was utilized as a threshold-independent metric. The AUC is formally defined as the integral of the ROC curve, which graphs the true positive rate (TPR) against the false positive rate (FPR):

where

AUC values approaching 1.0 indicate excellent model discrimination, whereas values close to 0.5 suggest random performance [108].

The MAE quantifies the average magnitude of prediction errors irrespective of their direction:

The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) is commonly employed to assess the accuracy of predictions in regression and time series models:

RMSE exhibits heightened sensitivity to larger errors as a result of the squaring process:

The performance indicators as a whole offered an extensive assessment of predictive accuracy, robustness, and generalization capacity of ML models concerning biochemical markers (TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, and FFA) related to fish quality and shelf-life during frozen storage conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Biochemical Quality Indicators During Storage

The evaluation of key biochemical parameters provided insight into the relative stability of whiting and Atlantic bonito during prolonged frozen storage, highlighting both the effects of temperature and the intrinsic differences between lean and fatty fish species. To verify both freshness and compositional representativeness, proximate composition was assessed at the beginning of storage (Table 2) and found that both species were nutritionally representative and suitable for evaluating frozen storage stability.

Table 2.

Proximate composition (%, dry matter basis) and pH values of fish species. (Mean value ± SD, n = 6).

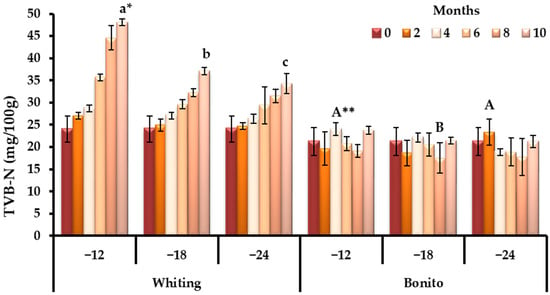

TVB-N levels rose steadily throughout storage for whiting, a trend typical of Gadidae species due to their pronounced enzymatic activity and susceptibility to microbial degradation. Atlantic bonito, by contrast, showed a more irregular pattern (Figure 1), with comparatively lower values across time (observed values varied between 17.49 and 24.03 mg/100 g, corresponding to the 8th at −18 °C and the 4th month at −12 °C, respectively) (p < 0.05). Preservation of TVB-N at −24 °C emphasized the protective effect of deep-freezing conditions (p < 0.05). By the end of storage, whiting exceeded the recommended threshold (30 to 35 mg/100 g TVB-N; according to Duarte et al. [52]), whereas bonito remained below it, reflecting intrinsic species differences in post-mortem biochemistry (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Species-specific dynamics of TVB-N during prolonged frozen storage across varying temperature regimes (−12, −18 and, −24 °C). * Bars with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means according to Duncan’s multiple range test for whiting (p < 0.05). ** Bars with different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among means according to Duncan’s multiple range test for bonito (p < 0.05).

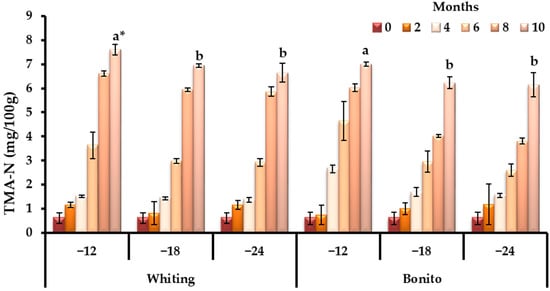

TMA-N results paralleled these observations, and whiting displayed consistently higher values than bonito across all experimental temperatures (p < 0.05), suggesting that trimethylamine oxide reduction is more active in Gadidae; however, at the end of the storage period, the mean values exhibited comparable values among species (p > 0.05). Both species stayed within the acceptability limit, and only in the tenth month values were nearby to thresholds (10–15 mg/100 g reported by Duarte et al. [52]) as supporting the role of TMA-N as a comparatively late spoilage marker relative to TVB-N (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Species-specific dynamics of TMA-N during prolonged frozen storage across varying temperature regimes (−12, −18, and −24 °C). * Bars with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

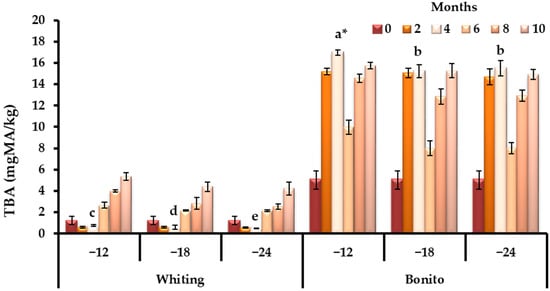

Indicators of lipid deterioration highlighted a contrasting trend, and bonito, with its higher lipid content, showed earlier and more intense oxidative changes, exceeding the TBA acceptability level (7–8 mg MA/kg reported by Schormuller [109]) by the second month of storage (p < 0.05). Whiting fillets remained stable for a longer duration, with values approaching the limit only at the tenth month (Figure 3). This distinction illustrates the greater vulnerability of fatty pelagic fish to oxidative rancidity relative to lean demersal species.

Figure 3.

Species-specific dynamics of TBA during prolonged frozen storage across varying temperature regimes (−12, −18, and −24 °C). * Bars with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

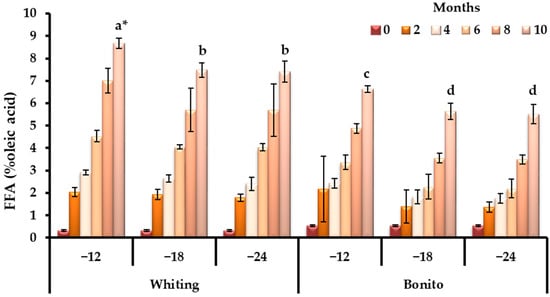

Figure 4 demonstrates that FFA accumulation reinforced the patterns of lipid breakdown and a rapid increase became evident from the fourth month onward in both species (p < 0.05), with temperature exerting a clear impact on the rate of hydrolysis. The concurrent elevation of FFA and TBA suggests that hydrolytic and oxidative mechanisms advanced in parallel, though with species-specific timing and magnitude.

Figure 4.

Species-specific dynamics of FFA during prolonged frozen storage across varying temperature regimes (−12, −18, and −24 °C). * Bars with different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

These findings underline how spoilage pathways diverge between lean and fatty fish, with whiting more prone to nitrogenous degradation and bonito to lipid oxidation. The assessment of storage stability is therefore best achieved by considering multiple biochemical indices in relation to both species characteristics and storage conditions.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistical parameters for the biochemical indicators. TVB-N values varied from 2.4 to 49 mg/100 g, with an average of 26.65 mg/100 g and a moderate standard deviation of 8.62. The positive skewness (0.736) and mild positive kurtosis (0.427) suggest that the distribution of TVB-N is moderately biased towards higher values with a somewhat peaked shape.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, SD, variance, skewness, kurtosis, overall sum, and median) of biochemical quality indicators.

The TMA-N values ranged from 0.36 to 8.00 mg/100 g, with an average of 3.45 mg/100 g. The distribution demonstrated positive skewness (0.448), indicating a propensity for elevated values, whereas the negative kurtosis (−1.258) signifies a comparatively flat distribution relative to normality.

The TBA values exhibited the broadest range (0.05–17.84 mg MA/kg) and the greatest variability (variance = 39.38), with a mean of 7.90 mg/kg. Despite the low skewness (0.195), the significantly negative kurtosis (−1.680) suggests a flat distribution, indicative of heterogeneity in lipid oxidation among samples.

FFA values varied between 0.62% and 9.69% oleic acid, with a mean of 3.89%. The positive skewness (0.690) indicates that higher values were more prevalent in subsequent storage periods, whereas the negative kurtosis (−0.665) signifies a relatively flat distribution.

The descriptive statistics collectively indicate that TVB-N and TBA demonstrated the highest variability and discriminatory capacity, while TMA-N and FFA exhibited more restricted distributions. These differences underscore the unique biochemical degradation patterns of proteins and lipids during frozen storage.

3.3. Machine Learning (ML) Classification Performance

The predictive outcomes of the five applied algorithms are summarized in Table 4. Classification accuracies ranged from 94.7% to 98.9%, reflecting overall reliable performance across models. XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy (98.9%) and Cohen’s κ (0.978). DT (98.4%, κ = 0.969) and NB (98.1%, κ = 0.962) followed closely, both demonstrating low error rates (14 and 17 misclassifications, respectively). The SVM model also performed consistently (96.9%, κ = 0.938), whereas the MLP showed the lowest performance (94.7%, κ = 0.893), misclassifying 48 samples. These results as a whole highlight the superior discriminative power of ensemble and tree-based approaches, particularly XGBoost, in modeling fish spoilage dynamics.

Table 4.

Classification performance of ML algorithms for predicting frozen fish quality based on biochemical parameters.

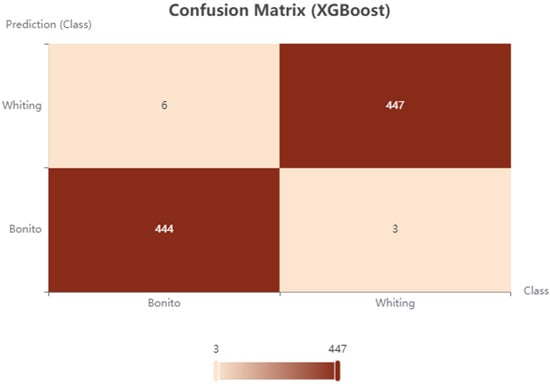

To further illustrate misclassification patterns, the confusion matrix of the best-performing model, XGBoost, was visualized as a heat map (Figure 5). The plot confirmed the quantitative findings by displaying an almost perfect concentration of correctly classified samples along the diagonal, while misclassifications were sparse and randomly distributed. Notably, Merlangius merlangus and Sarda sarda were predicted with remarkable precision, reinforcing the robustness of the ensemble approach. This visualization substantiates that misclassification errors were minimal and species-specific, thereby highlighting the superior discriminative capability of XGBoost.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix of the XGBoost model for classification of whiting and Atlantic bonito.

Alongside overall accuracy, class-specific performance metrics offered a more nuanced assessment of the classifiers (Table 5). R and P metrics consistently remained elevated across all algorithms, with the majority surpassing 0.95. XGBoost consistently attained optimal balance, with R and P exceeding 0.98 for both species, yielding the highest F-measure of 0.989. The DT and NB models exhibited robust predictive performance, achieving F-measures of 0.984 and 0.981, respectively. The SVM model exhibited consistent performance, achieving R and P values exceeding 0.94, along with an average F-measure of 0.969. On the other hand, the MLP classifier demonstrated relatively diminished sensitivity for Merlangius merlangus (R = 0.907), resulting in an overall F-measure of 0.949, despite satisfactory precision levels.

Table 5.

Class-specific R, P, and F-measure values for the five classification algorithms applied to frozen fish quality prediction.

These findings demonstrate the advantages of ensemble and tree-based methodologies, especially XGBoost, in modeling deterioration patterns from biochemical indicators, whereas NN architectures like MLP may necessitate more intricate configurations to attain similar reliability.

3.4. Machine Learning (ML) Regression Performance

The regression outcomes, summarized in Table 6, revealed clear differences in model performance for predicting storage duration from biochemical quality indicators. Among the tested approaches, the RFR exhibited the best predictive accuracy, achieving an R2 of 0.986 with the lowest error values (RMSE = 0.392; MAE = 0.202; MAPE = 0.048). The ensemble nature of this method allowed it to capture complex nonlinear interactions between biochemical markers more effectively than the other models.

Table 6.

ML regression model performances for predicting storage month based on biochemical quality indicators.

The SRT also performed well, with an R2 of 0.960, though its higher RMSE (0.662) relative to RF indicates reduced robustness when applied to heterogeneous biochemical profiles (Table 6). PR, by contrast, yielded the weakest results (R2 = 0.907), displaying the highest errors (RMSE = 1.008; MAE = 0.791; MAPE = 0.172). This suggests that polynomial fitting, while useful for certain curvilinear relationships, was inadequate for modeling the multi-dimensional variability inherent in frozen fish storage data.

Taken together, these findings confirm that ensemble-based regression methods substantially outperform single-tree or polynomial models, offering a more reliable framework for modeling spoilage trajectories. The consistent superiority of RF in both classification and regression analyses supports the validity of the classification accuracy (>98%) and indicates that this performance arises from genuine predictive patterns rather than overfitting. Moreover, the small standard deviations (<1.5%) observed across 10-fold cross-validation folds further confirm the stability and generalization ability of the models.

3.5. Model Performance Visualization and Interpretability

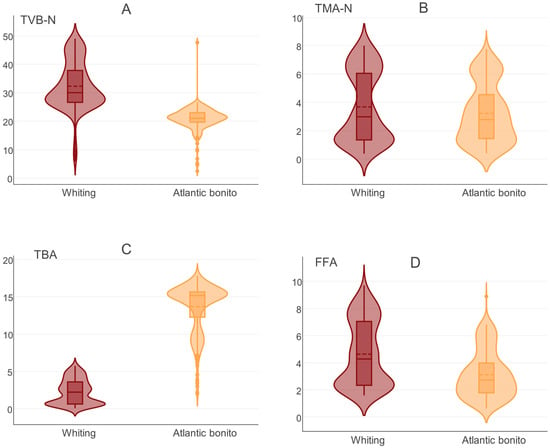

Along with numerical accuracy metrics, visual representations offer an intuitive comprehension of model performance and biological significance. Graphical tools like ROC curves and violin plots facilitate a thorough assessment by emphasizing class-specific discrimination capability, variability under different storage conditions, and species-dependent patterns. Moreover, feature importance analyses enhance interpretability by elucidating the biochemical parameters that most significantly impacted classification. These visualization and interpretability methods not only confirm the robustness of the developed models but also improve their applicability in food quality monitoring by connecting statistical results with practical biological insights. Figure 6 demonstrates that the violin plots of TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, and FFA values exhibit distinct species-specific variations. Sarda sarda demonstrated consistently elevated TBA values, signifying enhanced lipid oxidation, while Merlangius merlangus exhibited increased TVB-N and FFA levels, indicating protein degradation and spoilage trends. TMA-N values, although generally lower, still indicated inter-species variation. These graphical representations enhance statistical findings, validating that the predictive models accurately reflected biologically significant variation.

Figure 6.

Species-specific distribution of quality indices ((A): TVB-N, (B): TMA-N, (C): TBA, and (D): FFA) prolonged storage for whiting and Atlantic bonito.

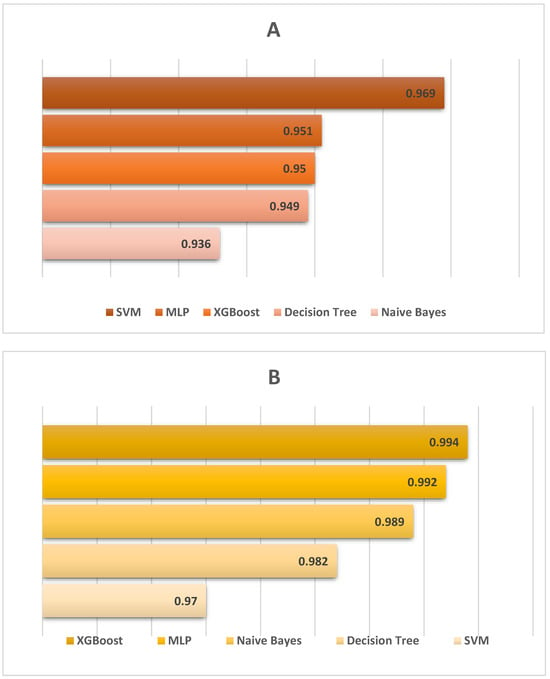

The ROC curve analysis demonstrated the discriminative efficacy of the evaluated parameters. Specifically, only chemical indicators with an AUC greater than 0.90 were retained, highlighting their efficacy as classification features. TBA (AUC = 0.994) in Sarda sarda and TVB-N (AUC = 0.949) in Merlangius merlangus exhibited exceptional predictive capability, indicating elevated sensitivity and specificity (Figure 7). Lipid oxidation and protein degradation markers are highly indicative for differentiating species and assessing storage-related quality alterations.

Figure 7.

AUC values of ML models. (A): Merlangius merlangus (TVB-N), (B): Sarda sarda (TBA).

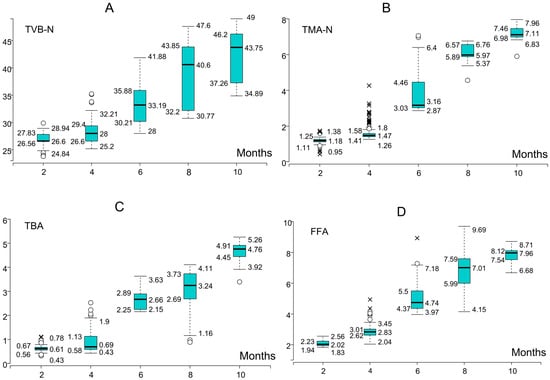

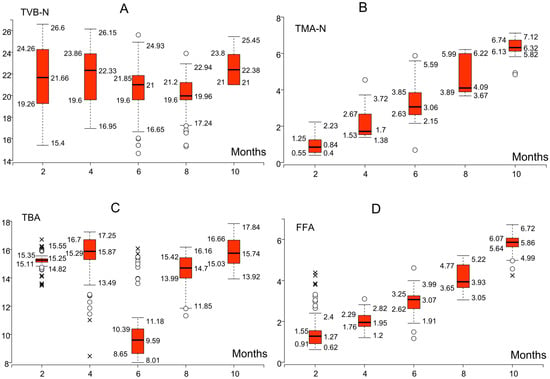

Taken in concert, these conditional box plots validate the efficacy of the proposed models while elucidating the biochemical parameters that most significantly impact prediction accuracy. Figure 8A–D depicts the temporal dynamics of biochemical quality indices in whiting subjected to frozen storage, with individual panels corresponding to specific parameters: (A) TVB-N, (B) TMA-N, (C) TBA, and (D) FFA. Progressive increases are observed across storage months, with TVB-N and FFA showing steeper trends, while TBA remains consistently higher and TMA-N accumulates steadily. These patterns highlight the discriminative potential of TVB-N and TBA for classification and enhance the interpretability of the ML models by linking spoilage dynamics to predictive accuracy.

Figure 8.

Conditional box plots showing the monthly variation in biochemical quality indicators ((A): TVB-N, (B): TMA-N, (C): TBA, and (D): FFA) for whiting during frozen storage. Circles represent mild outliers (values outside 1.5 × IQR), while crosses indicate extreme outliers (values outside 3 × IQR).

The conditional box plots in Figure 8 portray the temporal trajectories of biochemical quality indices in whiting during frozen storage. TVB-N exhibited a steady increase, surpassing the established spoilage threshold of 30–35 mg/100 g by the tenth month, thereby corroborating its reliability as a principal marker of deterioration. TMA-N concentrations remained within the acceptable interval (10–15 mg/100 g) throughout storage, though nearing the upper boundary by the tenth month, consistent with late-stage microbial catabolism. TBA values displayed a progressive elevation, approaching the critical threshold for oxidative rancidity (7–8 mg MDA/kg) at the tenth month, indicative of intensified lipid peroxidation, whereas FFA levels rose sharply from the fourth month onward, signifying an earlier onset of hydrolytic rancidity relative to the other indices.

The findings demonstrate that whiting maintained biochemical quality within acceptable thresholds until the ninth month of frozen storage, after which spoilage indices surpassed critical limits. Hence, the safe consumption period for whiting under these storage conditions can be estimated at approximately nine months. Following this evaluation, conditional box plots for Atlantic bonito were examined to characterize temporal patterns in biochemical quality dynamics, as presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Conditional box plots showing the monthly variation in biochemical quality indicators ((A): TVB-N, (B): TMA-N, (C): TBA, and (D): FFA) for Atlantic bonito during frozen storage. Circles represent mild outliers (values outside 1.5 × IQR), while crosses indicate extreme outliers (values outside 3 × IQR).

The conditional box plots in Figure 9 delineate the month-to-month evolution of biochemical quality indices in Atlantic bonito during frozen storage. Whereas TVB-N values remained well below the accepted spoilage threshold (30–35 mg/100 g), indicating that protein degradation was not a decisive factor in quality loss, TMA-N concentrations likewise persisted within the permissible interval (10–15 mg/100 g), reaching only 6–7 mg/100 g by the tenth month and thereby reflecting delayed yet limited activity. By contrast, TBA values exceeded the oxidative rancidity threshold (7–8 mg MDA/kg) from the outset of storage, which underscores lipid peroxidation as the dominant spoilage mechanism in this species. Furthermore, FFA levels rose progressively from the second month onward, surpassing 6 mg/100 g by the tenth month and thus corroborating the early manifestation of hydrolytic rancidity. Hence, the biochemical profile of Atlantic bonito demonstrates an accelerated onset of oxidative and hydrolytic spoilage relative to whiting, signifying a shorter safe consumption period despite persistently low TVB-N and TMA-N values.

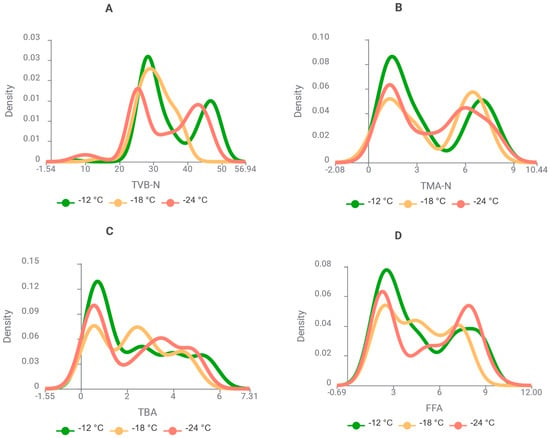

Proceeding from these observations, Figure 10 illustrates the effect of storage temperature (−12, −18, and −24 °C) on the biochemical quality indicators of whiting, providing further insight into temperature-dependent preservation capacity in this species.

Figure 10.

Kernel density plots showing the effect of storage temperature (−12, −18, and −24 °C) on biochemical quality indicators ((A): TVB-N, (B): TMA-N, (C): TBA, and (D): FFA) of whiting (Merlangius merlangus) during frozen storage.

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of storage temperature on the biochemical quality indicators of whiting during frozen storage. At −12 °C, all parameters (TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, and FFA) exhibited broader distributions and higher density peaks, indicating accelerated spoilage dynamics at the highest storage temperature. Intermediate values were observed at −18 °C, whereas −24 °C consistently yielded narrower distributions and lower density peaks, reflecting delayed protein degradation (TVB-N, TMA-N) and reduced lipid oxidation and hydrolytic rancidity (TBA, FFA). These findings substantiate that −24 °C afforded the greatest preservation of whiting quality across the storage period. Relative to this, Figure 11 delineates the influence of storage temperature (−12, −18, and −24 °C) on the biochemical quality indices of Atlantic bonito, thereby permitting direct comparison with whiting while simultaneously elucidating the longitudinal progression of spoilage dynamics.

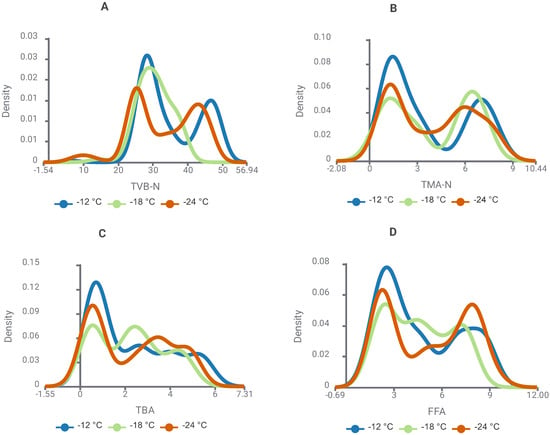

Figure 11.

Kernel density plots showing the effect of storage temperature (−12, −18, and −24 °C) on biochemical quality indicators ((A): TVB-N, (B): TMA-N, (C): TBA, and (D): FFA) of Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda) during frozen storage.

The density plots in Figure 11 display the influence of storage temperature on the biochemical quality indices of Atlantic bonito during frozen storage. In contrast to whiting, both TVB-N and TMA-N values in bonito remained comparatively stable and below regulatory thresholds across all temperatures, signifying minimal protein catabolism and restrained microbial activity. Counter to this, TBA values were escalated from the onset of storage, with more pronounced density peaks at −12 °C and −18 °C, thereby exhibiting the species’ heightened predisposition to lipid peroxidation. FFA distributions likewise expanded over time, attaining their highest levels at −12 °C, which indicates an acceleration of hydrolytic rancidity under comparatively milder freezing regimes. Even under −24 °C storage, where oxidative and hydrolytic deterioration were constrained, TBA concentrations surpassed the rancidity threshold, evidencing lipid peroxidation as the leading pathway of spoilage in Atlantic bonito.

The comparative appraisal of whiting and Atlantic bonito reveals distinct species-specific spoilage trajectories and storage demands. In whiting, quality deterioration was primarily governed by protein catabolism and microbial proliferation, with TVB-N and TMA-N surpassing critical thresholds only under higher storage temperatures and at advanced stages; thus, preservation at −18 °C was sufficient to maintain acceptability, while −24 °C conferred superior biochemical stability. On the contrary, Atlantic bonito displayed pronounced susceptibility to lipid peroxidation and hydrolytic rancidity from the outset, as TBA values exceeded rancidity thresholds irrespective of storage duration, thereby designating −24 °C as the sole condition capable of retarding oxidative decline. These outcomes underscore that while whiting tolerates preservation under moderately low temperatures, Atlantic bonito necessitates deep-freezing at −24 °C to secure product integrity and prolong marketability, demonstrating the critical need for species-tailored preservation strategies.

4. Discussion

The present results corroborate the long-established principle that freezing delays, yet cannot abolish, biochemical deterioration—a concept articulated by Varlık [6] and Sikorski and Pan [7] and substantiated by more recent syntheses [17]. However, the prevailing spoilage mechanisms diverged markedly between whiting and bonito, underscoring the decisive influence of muscle biochemistry. Gadidae, with intrinsically high proteolytic enzyme activity, exhibited progressive elevations in TVB-N and TMA-N, whereas pelagic species enriched in PUFA proved acutely susceptible to oxidative rancidity [12,35,54]. The influence of temperature on spoilage dynamics became most apparent under deep-freezing, where −24 °C markedly delayed the accrual of biochemical indices compared with −18 °C and −12 °C. This outcome is consistent with classical observations that lipid-rich species require lower thresholds to suppress oxidative reactions [13,14]. Even so, deterioration persisted under these conditions, pointing to the sustained contribution of endogenous enzymes and self-propagating oxidative cascades at subzero temperatures [16,29]. Insights from recent predictive modeling further reinforce this perspective, indicating that quality decline is more faithfully explained by the integrated time–temperature trajectory than by nominal setpoints [5,60].

When nitrogenous markers are considered, interspecific contrasts become more pronounced. In whiting, TVB-N surpassed the 30–35 mg/100 g threshold by the end of storage, while bonito remained below this limit, reflecting the relatively restrained enzymatic activity and microbial susceptibility of pelagic musculature. TMA-N increased more gradually, approaching the 10–15 mg/100 g benchmark only in the tenth month, thereby corroborating its classification as a comparatively late spoilage indicator [52,55]. This delayed pattern is attributable to the fact that TMA-N formation depends on the reduction of trimethylamine oxide, a pathway inherently slower than the deamination reactions driving TVB-N accumulation.

The course observed in bonito, with TBA values exceeding the 7–8 mg MDA/kg threshold as early as the second month [109], reveals the oxidative vulnerability of PUFA-rich pelagic muscle [33,34]. Whiting, in distinction, displayed markedly greater resilience, with comparable values reached only toward the tenth month, a pattern attributable to the protective effect of its leaner biochemical composition. These divergent responses underscore the conjoint influence of lipid architecture and thermal regime in shaping oxidative stability. The interplay was recorded explicitly by Aydın and Gökoglu [110] in anchovy, where freezing temperature and duration acted synergistically to dictate the pace of rancidity, with higher temperatures and prolonged storage accelerating lipid peroxidation. The present findings parallel this dynamic, reinforcing the interpretation that oxidative stability cannot be reduced to fat content alone but emerges from the interaction of tissue composition, storage temperature, and duration.

The simultaneous increase in FFA and TBA across both species further indicates that hydrolytic and oxidative pathways progress in concert, with lipolysis supplying substrates that intensify peroxidative cascades—a relationship emphasized by Konig and Mol [38] and Polvi et al. [40] and corroborated in more recent structural investigations [22,23]. Considered in this context, these observations support the framework of a spoilage triad—lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and enzymatic activity—advancing in parallel during frozen storage, as articulated by Wang et al. [59] and Widjaja et al. [58] and further substantiated by recent mechanistic studies [37,54]. Crucially, the dominant pathway is species-dependent: nitrogenous degradation governs lean demersals, whereas oxidative rancidity prevails in fatty pelagics, with storage temperature exerting a modulatory influence on both processes.

From an ML standpoint, the models yielded biologically interpretable outcomes for spoilage classification and shelf-life estimation. For whiting, TVB-N surpassed the spoilage threshold only in the later storage period, rendering it the principal indicator of long-term stability. By comparison, Atlantic bonito exhibited persistently high TBA values from the outset, positioning TBA as the most discriminative index for early oxidative spoilage. These interspecific patterns were reflected in the feature-importance profiles of the models, where TVB-N and TBA consistently occupied the highest ranks. Integrating ML outputs with conditional box plots reinforced the concordance between predictive scores and biochemical trends, thereby clarifying species-specific pathways of deterioration and enhancing model interpretability.

To clarify the analytical role of machine learning within this work, it is important to distinguish the present framework from both simplistic species classification and traditional reaction-kinetic modeling. The ML models were designed to resolve spoilage states and storage-dependent quality boundaries, using established biochemical thresholds as the basis for prediction. This allowed the models to define, for example, the markedly longer stability of whiting at −24 °C compared with the rapid oxidative failure of Atlantic bonito at the same temperature—outcomes directly linked to the species-specific biochemical signatures embedded in the dataset. Unlike classical Arrhenius-type, zero- or first-order formulations, which assume a single response variable and impose fixed linear or log-linear relationships between temperature and reaction rates, supervised ML accommodates the nonlinear, multivariate, and species-dependent interactions that characterize frozen-storage deterioration. By learning deterioration trajectories directly from empirical time–temperature–indicator combinations, the models capture non-additive relationships—such as the coupled rise in TBA and FFA in pelagic muscle or the divergent temperature sensitivities of nitrogenous indices in lean demersals—that cannot be expressed readily within a single kinetic equation.

The structure of the dataset further reinforces the suitability of ML, comprising repeated measurements of four biochemical indicators across three temperatures and two physiologically distinct species. This multivariate, heterogeneous design is precisely the analytical domain in which supervised ML excels: it maps biochemical profiles onto spoilage states and shelf-life horizons without imposing restrictive parametric forms. Moreover, feature-importance rankings, conditional response patterns, and species-specific trajectories all exhibit strong concordance with the biochemical mechanisms presented earlier in the results, demonstrating that the models recover physiologically coherent pathways rather than arbitrary statistical artifacts. The ML framework therefore complements—rather than replaces—classical kinetic reasoning, offering a higher-resolution, data-intelligent interpretation of frozen-storage behavior by integrating multiple spoilage pathways into a unified predictive construct. In this respect, ML provides analytical capabilities that conventional kinetic models, by design, are unable to achieve.

Within this framework, ensemble approaches—particularly RF and XGBoost—delivered high predictive accuracy for the spoilage dynamics of whiting (Merlangius merlangus) and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda). Classical biochemical indices (TVB-N, TMA-N, TBA, FFA) proved the most reliable predictors, attesting to their enduring value for frozen seafood quality assessment. The results establish that strong predictive performance can be achieved without recourse to highly complex or non-destructive sensing systems, while still generating interpretable outputs relevant to industrial practice. Comparable outcomes across other fish and shellfish species (Table 7) suggest that such predictive frameworks retain validity across taxa and storage regimes. Crucially, empirical thresholds integrated with ML outputs indicated that whiting preserved acceptable quality for up to nine months at −24 °C, whereas Atlantic bonito surpassed rancidity limits within two months. Ensemble models accurately resolved these spoilage horizons, demonstrating their capacity not only to classify deterioration but also to define species- and temperature-dependent shelf-life boundaries essential for cold-chain management.

Table 7.

Applications of ML in forecasting quality dynamics of frozen seafood, integrating biochemical and sensory indices.

Recent applications of ML to frozen seafood have reinforced the predictive utility of classical biochemical and sensory indices (Table 7). In golden pompano, Lan et al. [72] traced spoilage most closely to TVB-N and water retention, while Tan et al. [71] attained MAPE near 5% in squid when modeling texture and sulfhydryl groups. Chu et al. [111] established the relevance of TVB-N, K-value, and whiteness in croaker, keeping prediction errors below 8%. In salmon, Jia et al. [112] ranked TBA and TVB-N among the most informative variables across RBFNN and SVR frameworks. Chen et al. [73] applied RF to shrimp, achieving strong predictive accuracy with TBA and sensory metrics, and Xu et al. [63] corroborated the consistency of TVB-N, pH, and hypoxanthine in shrimp, with errors within ±2%. Considered together, these contributions converge on a clear principle: nitrogenous and oxidative indices—most notably TVB-N and TBA—serve as cross-species anchors for ML-based spoilage prediction, a principle affirmed by the present results for whiting and bonito.

Beyond model performance, recent investigations have affirmed the centrality of biochemical quality indices as predictive variables in seafood spoilage assessment (Table 8). Currò et al. [69] achieved R2 values approaching 0.97 for histamine modeling in tuna, while Wang et al. [66] predicted TVB-N in freeze–thawed tilapia with accuracies exceeding 97% through convolutional neural networks (CNN). Xu et al. [63] and Kong et al. [61,62] established the reliability of TVB-N, K-value, and lipid–protein indices in shrimp and carp, with errors consistently below 5–10%. Chen et al. [73] validated RF for shrimp using TBA and sensory metrics, and Hu et al. [74] applied transformer architectures for hairtail grading, attaining F1 scores above 92%. Considered in synthesis, these studies converge on a consistent principle: nitrogenous and oxidative markers constitute universal predictors of seafood spoilage. Our results consolidate this principle, identifying TVB-N, TBA, and FFA as the pivotal biochemical signals dictating spoilage trajectories in whiting and bonito.

Table 8.

Selected literature exemplifying the use of ML frameworks in conjunction with biochemical quality indices.

This study extends conventional frozen-storage research by demonstrating how ML models can capture nonlinear, multivariate relationships among biochemical indicators, temperature, and time. Unlike traditional kinetic equations that assume fixed reaction rates, the proposed framework learns degradation trajectories directly from experimental data, revealing species-specific spoilage dynamics. This integrative, data-driven approach offers a complementary perspective to classical kinetic modeling for predicting frozen-fish quality.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes that ensemble ML frameworks, particularly RF and XGBoost, achieve high predictive accuracy for the spoilage dynamics of whiting (Merlangius merlangus) and Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda) during frozen storage. The comparative approach further delineated species-specific pathways: nitrogenous degradation predominated in lean demersals, whereas oxidative rancidity prevailed in pelagic, PUFA-rich muscle. Freezing mitigated—but did not entirely stop—spoilage, with both temperature and duration proving determinative; in this scenario, species-specific fragility and the overriding influence of the time–temperature interplay became evident.

In synthesis, the work contributes both theoretical and applied advances: (i) validating ensemble learning as a robust predictive framework across species, (ii) consolidating the concept of a spoilage triad—lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and enzymatic activity—progressing in parallel during frozen storage, and (iii) providing actionable insights for industry in defining safe storage horizons and optimizing cold-chain protocols. Future research should integrate ensemble learning with non-destructive sensing technologies to enable real-time, AI-driven monitoring of seafood quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, İ.M.T.; methodology, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; software, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; formal analysis, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; data curation, İ.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; writing—review and editing, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; visualization, İ.M.T. and D.G.K.; supervision, İ.M.T.; project administration, İ.M.T.; funding acquisition, İ.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed and/or generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TVB-N | Total Volatile Basic Nitrogen |

| TMA-N | Trimethylamine Nitrogen |

| TBA | Thiobarbituric Acid |

| FFA | Free Fatty Acids |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| TCA | Trichloracetic Acid |

| H2SO4 | Sulfuric Acid |

| MA | Malondialdehyde |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| N × 6.25 | Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor (for crude protein) |

| HCl | Hydrochloric Acid |

| UV/VIS | Ultraviolet–Visible (spectrophotometer) |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids |

| RF | Random Forest |

| NIR | Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| WHC | Water Holding Capacity |

| TVC | Total Viable Counts |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| K-value | ATP Degradation Index |

| BP NN | Backpropagation Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory network |

| RBFNN | Radial Basis Function Neural Network |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| MPLS | Modified Partial Least Squares |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| SRT | Simple Regression Tree |

| PR | Polynomial Regression |

| RFR | Random Forest Regression |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function (kernel) |

| ETSFormer | Transformer Architecture Based on Exponential Smoothing |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| F1 | F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| κ (Kappa) | Cohen’s Kappa Coefficient |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| P (PPV) | Precision/Positive Predictive Value |

| R (Recall) | Recall/Sensitivity/True Positive Rate |

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

References

- Ramadhan, A.H.; Yu, D.; Hlaing, K.S.S.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W. Effects of packaging and storage time on lipid and protein oxidation and modifications in texture characteristics of refrigerated grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) fish muscles. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, vvaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Tian, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Ishimura, G.; Sasaki, K.; Niu, Y.; Yuan, C. Effects of thawing methods on the biochemical properties and microstructure of pre-rigor frozen scallop striated adductor muscle. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaklı, Ş. Su Ürünleri Işleme Teknolojisi; Ege Üniversitesi Yayınları, Su Ürünleri Fakültesi: Bornova, Türkiye, 2008; Yayın No: 77; p. 513. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa, N.; Okazaki, E. Recent research on factors influencing the quality of frozen seafood. Fish. Sci. 2020, 86, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Walayat, N.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J. The role of trifunctional cryoprotectants in the frozen storage of aquatic foods: Recent developments and future recommendations. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varlık, C. Balık ve kanatlı etlerinin soğutulması, dondurulması ve depolanması. In Proceedings of the Soğuk Tekniği Uygulamaları Semineri, April 1987; Tübitak Marmara Araştırma Enstitüsü: Gebze, Türkiye, 1987; pp. 1–11. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, Z.E.; Pan, B.S. Preservation of seafood quality. In Seafoods: Chemistry, Processing, Technology and Quality; Shahidi, F., Botta, J.R., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994; pp. 335–360. [Google Scholar]

- Liciardello, J.J. The Seafood Industry; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1990; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Göğüş, A.K.; Kolsarıcı, N. Su Ürünleri Teknolojisi; Ankara Üniversitesi Ziraat, Fakültesi Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 1992; p. 358. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Uzunkuşak, A. Gıda maddelerinin dondurulması prensipleri ve donmuş gıda endüstrisinin tekamülü. Et Endüstrisi Derg. 1971, 5, 29–36. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Gülyavuz, H.; Ünlüsayın, M. Su Ürünleri Işleme Teknolojisi; Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi, Eğirdir Su Ürünleri Fakültesi: Isparta, Türkiye, 1999. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- French, J.S.; Kramer, D.E.; Kennish, J.M. Protein hydrolysis in coho and sockeye salmon during partially frozen storage. J. Food Sci. 1988, 53, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludorff, W.; Meyer, V. Fische und Fischerzeugnisse; AVI Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Khayat, A.; Schwall, D. Lipid oxidation in seafood. Food Technol. 1983, 37, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Shamberger, R.J.; Shamberger, B.A.; Willis, C.E. Antioxidants and cancer. IV. Initiating activity of malonaldehyde as a carcinogen. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1974, 53, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hultin, H.O. Oxidation of lipids in seafoods. In Seafoods: Chemistry, Processing Technology and Quality; Shahidi, F., Botta, J.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yan, J.; Xie, J. Effect of vacuum and modified atmosphere packaging on moisture state, quality, and microbial communities of grouper (Epinephelus coioides) fillets during cold storage. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, Z.E. Seafood: Resources, Nutritional Composition, and Preservation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, J.; Srikar, L.N. Protein and lipid changes in pink perch (Nemipterus japonicus) mince during frozen storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1994, 31, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Simeonidou, S.; Govaris, A.; Vareltzis, K. Effect of frozen storage on the quality of whole fish and fillets of horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) and Mediterranean hake (Merluccius mediterraneus). Z. Lebensm. Unters. ForschA 1997, 204, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymenidinis, A.; Kotter, H.C.L.; Terplan, G. Kühlen und Gefrieren von Fleisch. Fleischwirtschaft 1978, 5, 702–711. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Yagiz, Y.; Balaban, M.O.; Marshall, M.R.; Otwell, W.S. Comparison of sensory and instrumental methods for the analysis of texture of cooked individually quick frozen and fresh-frozen catfish fillets. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Y. Spoilage-related microbiota in fish and crustaceans during storage: Research progress and future trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 252–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, Z.E.; Kolakowska, A. Freezing of marine food. In Seafood: Resources, Nutritional Composition and Preservation; Sikorski, Z.E., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1990; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, Z.E.; Kolakowska, A. Changes in proteins in frozen stored fish. In Seafood Proteins; Sikorski, Z.E., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994; pp. 234–254. [Google Scholar]

- Connel, J.J. Changes in the eating quality of frozen stored cod and associated chemical and physical changes. In Freezing and Irradiation of Fish; Fishing News (Books); FAO: Rome, Italy, 1969; pp. 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, P.J.; Ackman, R.G.; Linke, B.A.; Nash, D.M. Differential lipid oxidation in various parts of frozen mackerel. J. Food Technol. 1977, 12, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstorebrov, I.; Eikevik, T.M.; Bantle, M. Effect of low and ultra-low temperature applications during freezing and frozen storage on quality parameters for fish. Int. J. Refrig. 2016, 63, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsailawi, H.; Mudhafar, M.; Abdulrasool, M. Effect of frozen storage on the quality of frozen foods—A review. J. Chem. 2020, 14, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundakçı, A. Haskefal ve sazan balıklarının dondurularak saklanması sırasında lipidlerdeki değişmeler. Doctoral Dissertation, Ege Üniversitesi, İzmir, Türkiye, 1979. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Ciarlo, A.; Boeri, R.; Giannini, D. Storage life of frozen blocks of Patagonian hake (Merluccius hubbsi) filleted and minced. J. Food Sci. 1985, 50, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, J.J.; Elinor, M.R. Frozen storage characteristics of cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus). J. Food Qual. 1988, 11, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, A.; Srikar, L.N. Changes in flesh lipids of seer fish during frozen storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1987, 24, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Varlık, C.; Yolcular, H. Dondurulmuş lüfer ve hamsinin depolanması. Gıda Sanayi 1987, 2, 39–42. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Vareltzis, K.; Zetou, F.; Tsiaras, I. Textural deterioration of chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus collias) and smooth hound (Mustellus mustellus L.) in frozen storage in relation to chemical parameters. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol. 1988, 21, 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Srikar, L.N.; Seshadari, H.; Fazal, A. Changes in lipids and proteins of marine catfish (Tachysurus dussumieri) during frozen storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1989, 24, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wu, T.; Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Li, H. Effects of ultrasound treatment on muscle structure, volatile compounds, and small molecule metabolites of salted Culter alburnus fish. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 97, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konig, A.J.; Mol, T.H. Quantitative quality tests for frozen fish: Soluble protein and free fatty acid content as quality criteria for hake (Merluccius capensis) stored at –18 °C. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1991, 54, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boran, M. Farklı işlem uygulanarak dondurulan hamsilerde muhafaza süresince oluşan kalite değişiklikleri üzerine bir araştırma. Master’s Thesis, Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi, Trabzon, Türkiye, 1991. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Polvi, S.M.; Ackman, R.G.; Lall, S.P.; Saunders, R.L. Stability of lipids and omega–3 fatty acids during frozen storage of Atlantic salmon. J. Food Process. Preserv. 1991, 15, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaklı, Ş.; Tokur, B.; Çelik, U.; Taşkaya, L. No-frost koşullarda depolanan sardalya balıklarının (Sardina pilchardus) fiziksel, kimyasal ve duyusal değerlendirilmesi. In Proceedings of the Akdeniz Balıkçılık Kongresi Bildirileri, İzmir, Türkiye, 9–11 April 1997; pp. 733–740. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic, S.; Jankovic, S.; Baltic, T.; Nikolic, D.; Djinovic-Stojanovic, J.; Lukic, M.; Parunovic, N. Histamine in canned and smoked fishery products sold in Serbia. Meat Technol. 2019, 60, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careche, M.; Li-Chan, E.C.Y. Structural changes in cod myosin after modification with formaldehyde or frozen storage. J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Aubourg, S.P.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Gallardo, J.M.; Sotelo, C.G. Consequences of frozen storage for nutritional value of hake. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 1999, 5, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, M.; Tatar, O. Fileto ve bütün olarak dondurulmuş gökkuşağı alabalığının (Oncorhynchus mykiss W.) muhafazası süresince yağ asitleri bileşimlerindeki değişmelerin araştırılması. Ege J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001, 18, 1–8. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Baygar, T.; Özden, Ö.; Üçok, D. Dondurma ve çözündürme işleminin balık kalitesi üzerine etkisi. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2004, 28, 173. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Aubourg, S.P.; Piñeiro, C.; González, M.J. Quality loss related to rancidity development during frozen storage of horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchała, R.; Białowąs, H.; Pilarczyk, M. Influence of cold and frozen storage on carp (Cyprinus carpio) flesh quality. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 55, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Geirsdottir, M.; Hlynsdottir, H.; Thorkelsson, G.; Sigurgisladottir, S. Solubility and viscosity of herring (Clupea harengus) proteins as affected by freezing and frozen storage. J. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 72, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, C.P.; Kjærsgaard, I.V.H.; Jessen, F.; Jacobsen, C. Protein and lipid oxidation during frozen storage of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8118–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, F.A.F.; Sant’Ana, H.M.P.; Campos, F.M.; Costa, N.M.B.; Silva, M.T.C.; Salaro, A.L.; Franceschini, C.C. Fatty acid composition of three freshwater fishes under different storage and cooking processes. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.M.; Silva, F.; Pinto, F.R.; Barroso, S.; Gil, M.M. Quality assessment of chilled and frozen fish—Mini review. Foods 2020, 9, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, N.; Tang, W.; Wang, X.; Yi, M.; Guo, L.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Ahmad, I.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N. Quality evaluation of frozen and chilled fish: A review. eFood 2023, 4, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zeng, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, M.; Zheng, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, H. Changes in quality characteristics based on protein oxidation and microbial action of ultra-high pressure-treated grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) fillets during magnetic field storage. Food Chem. 2024, 434, 137464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokur, B.; Kandemir, S. Dondurulmuş balıklarda farklı çözündürme şekillerinin protein kalitesine olan etkileri. J. Fish. Sci. 2008, 2, 100–106. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]