3.2. Preliminaries

We begin by defining each artwork

as a multimodal unit of analysis composed of four distinct but interrelated components: the digital image

; the metadata vector

(artist, title, date); the curatorial or descriptive text

; and the structured cultural-historical ontology

that situates the work within a broader domain-specific taxonomy. These are grouped as

The entire art historical corpus is modeled as a temporally ordered sequence

, where

denotes discrete historical time steps (such as decades or centuries). This temporal structuring enables us to trace stylistic developments, influence propagation, and curatorial shifts across time.

To support downstream reasoning tasks, we embed all artworks into a shared high-dimensional latent space

using a learnable encoding function

:

Here,

is a multimodal encoder parameterized by

, responsible for integrating visual, textual, and contextual signals into a unified vector representation

. This embedding captures the semantic, stylistic, and historical content of each artwork.

To model influence between artworks, we define a composite similarity score that accounts for both visual resemblance and textual semantic alignment. The influence score

between artworks

and

is given by

where

and

are weighting parameters summing to 1. The term

denotes cosine similarity between the visual embeddings:

and

represents semantic similarity based on textual information, computed via a pretrained transformer encoder

:

This formulation allows for the balanced integration of visual style and curatorial discourse when determining relationships between works.

Based on the influence score, we construct a directed acyclic graph (DAG)

, where each node corresponds to an artwork embedding and edges represent probable influences. An edge from

to

is established if the influence score exceeds a threshold

:

This graph forms the basis for analyzing stylistic flow and directional transitions in art history.

To uncover macro-level stylistic structures, we define a clustering function

that assigns each embedding

to a latent style class indexed by

:

Each cluster captures a distinct style or movement derived from patterns in the embedding space. We further define inter-cluster stylistic transition probabilities, quantifying the directional flow of influence from one style cluster to another:

This helps trace stylistic evolution between movements or schools across time.

To model institutional authority and curatorial value, we define a canonical reference set

and introduce a label function

that marks whether an artwork is deemed canonical:

We then learn a discriminative function

that predicts canonicality score directly from the embedding:

This enables the system to align its representation with expert-defined hierarchies and institutional standards.

3.3. Multimodal Classification via Styloformer

While originally developed for static artworks, our use of curatorial metadata and ontological descriptors is intentionally adapted for the analysis of art film scenes. Many art films—especially within experimental, modernist, and auteur traditions—construct scenes that are explicitly styled after historical artworks or evoke visual tropes from fine art. For example, mise-en-scène choices often reflect painterly composition, symbolic color palettes, or visual motifs with cultural–historical meaning. By embedding these curatorial and ontological signals into the model, we allow the system to reason beyond surface-level audiovisual patterns and instead incorporate interpretive priors rooted in visual culture. This cross-domain strategy enables the model to better understand and classify film scenes that operate in the interspace between cinema and visual art.

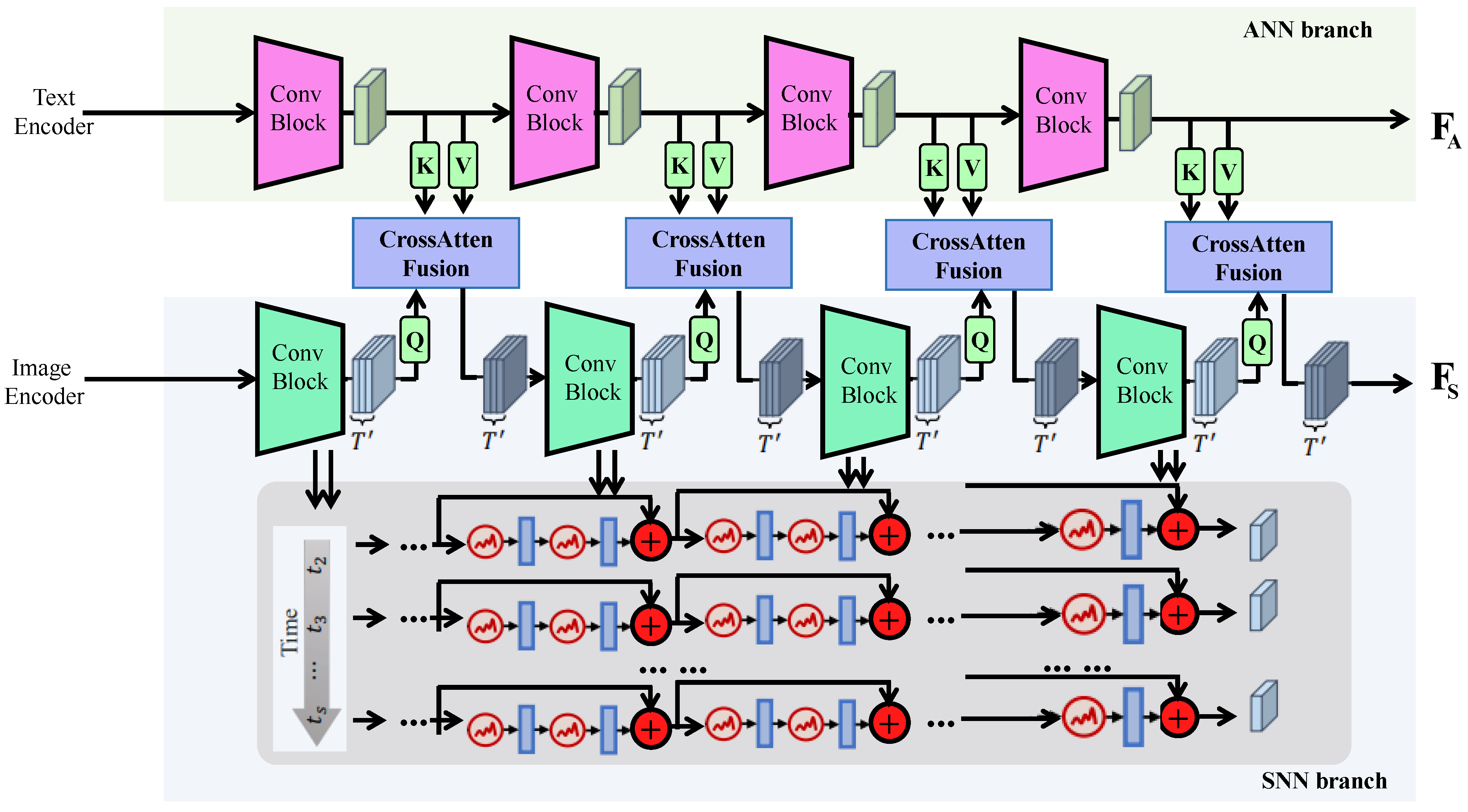

The audio modality is processed using a self-supervised audio transformer backbone pretrained on large-scale video-sound corpora. Raw audio tracks are first resampled to 16 kHz mono format and then segmented into 1-s windows with 50% overlap. Each segment is transformed into a 128-bin log-Mel spectrogram using a Hamming window of 25 ms and a hop length of 10 ms. This spectrogram is normalized per clip and then encoded via a convolutional frontend followed by transformer blocks, yielding a sequence of temporal audio embeddings aligned to the video frame rate. These embeddings capture both ambient texture and symbolic sound cues—elements critical in art film sound design. The resulting audio token sequence is passed to the cross-modal fusion module for attention-based integration with visual and textual features.

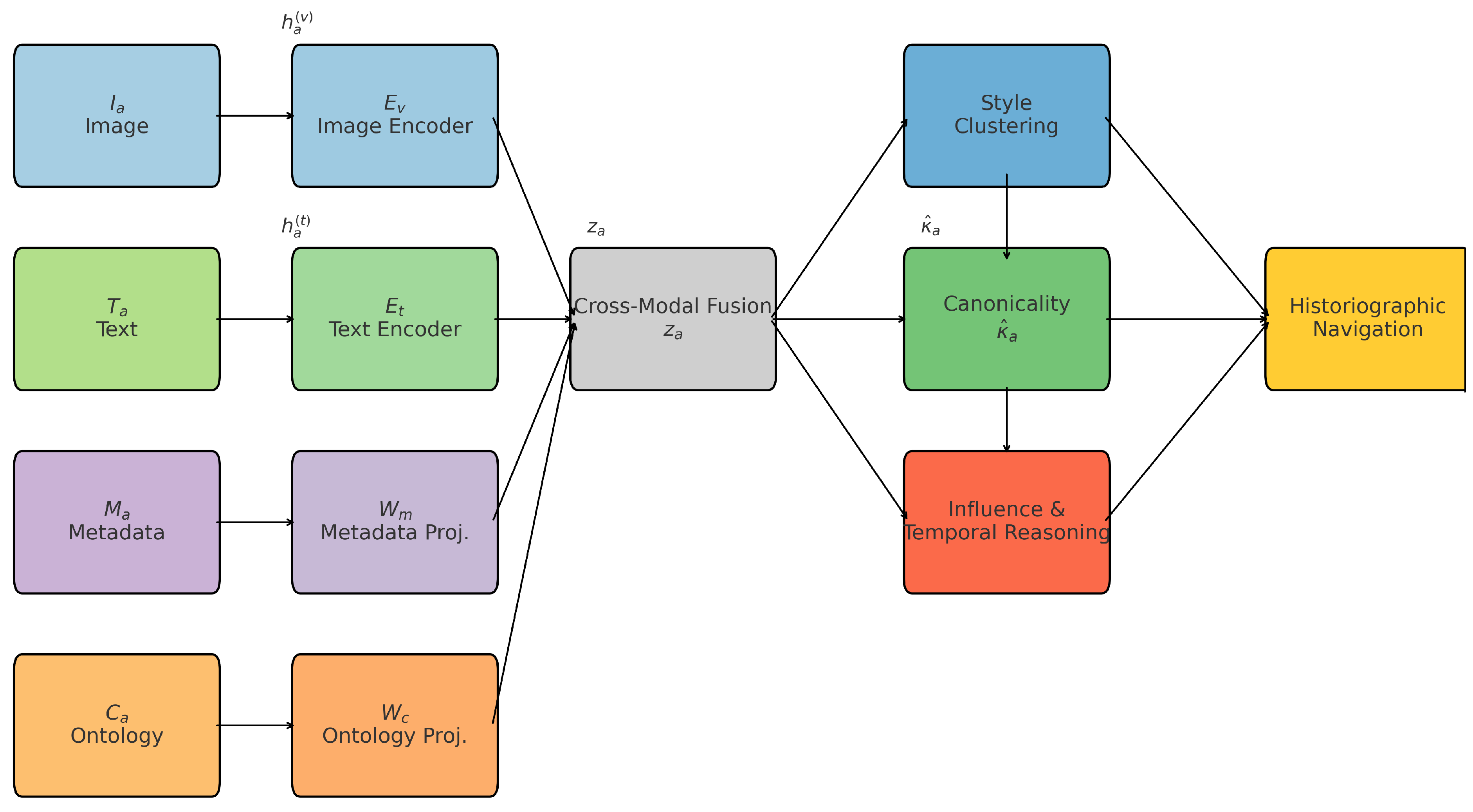

To analyze visual culture with historical sensitivity and computational tractability, we propose Styloformer, a unified multimodal transformer-based architecture designed to encode, relate, and infer across diverse data modalities inherent in artworks. Styloformer extends the conventional encoder–decoder framework to jointly model iconographic semantics, stylistic features, and historiographic influence flows. Let each artwork

be defined by the tuple

, as introduced in

Section 3.2. The Styloformer architecture encodes each component into a unified latent embedding

using a multimodal transformer stack (as shown in

Figure 1).

To address the common issue of temporal misalignment between visual and auditory streams—particularly relevant in art films where asynchronous montage is frequent—we apply a frame-level alignment strategy in preprocessing. Video frames and audio spectrograms are segmented into uniform time windows (e.g., one-second intervals), ensuring temporal correspondence at the token level. Each modality’s tokens are assigned timestamp-based positional encodings, allowing the fusion transformer to reason across aligned and misaligned content. Importantly, our cross-modal attention mechanism performs soft alignment. It is not restricted to strict one-to-one token matching but allows each modality to attend to a temporally adjacent range of tokens from the other. This enables the model to recover semantic alignment in cases of desynchronized editing, such as when a visual scene precedes or follows its associated audio cue. The attention weights learn to prioritize temporally and semantically relevant signals, thus providing resilience against symbolic or nonlinear synchronization patterns.

The audio stream is first processed by a convolutional frontend composed of four 1D convolutional layers with kernel sizes of [5, 3, 3, 3] and channel widths [64, 128, 128, 256], each followed by batch normalization and GELU activation. This captures both short- and mid-range temporal patterns in the waveform or spectrogram representation. The resulting feature map is flattened and passed through a transformer encoder consisting of 4 layers, each with 8 attention heads, a hidden size of 512, and a feedforward dimension of 1024. Positional encodings are added to preserve temporal order. The final output is a sequence-level embedding that is fused with visual and metadata features through cross-modal attention.

In order to produce a unified and semantically rich embedding space for art historical analysis, the model first encodes each modality using specialized backbones tailored to their respective data structures. The visual modality,

, which represents the raw image of the artwork, is fed into a hierarchical vision transformer

that tokenizes the image into

N non-overlapping patches. Each patch is processed into a

d-dimensional token embedding, forming the sequence

. This process retains both local visual details and global compositional structure, which are essential for understanding artistic style, composition, and visual symbolism:

In parallel, the textual description

, which includes curatorial commentary, catalogue entries, and interpretive annotations, is processed by a pretrained language model

such as BERT or RoBERTa. This encoder transforms the input token sequence into a contextualized embedding matrix

, where

L denotes the number of tokens. These text embeddings capture institutional knowledge, iconographic references, and historical narratives that may not be visually explicit but are crucial for scholarly interpretation:

In addition to these high-dimensional modalities, structured metadata

(title, date, material, artist) and symbolic ontology vectors

(school, style, religious affiliation) are projected via linear transformations into the same latent space. This ensures that tabular and graph-encoded data can participate equally in the fusion process. Let

be learned projection matrices and

be corresponding bias terms. Then the embeddings for metadata and ontology are

These four modalities—image patch sequence, tokenized text, structured metadata, and symbolic context—are then concatenated and aligned using a transformer-based fusion module

. This block performs multi-head self-attention across all modality types, learning to weigh their respective importance based on content. For example, when curatorial text is sparse, image attention dominates; when iconography is abstract, ontology may guide representation. The fused multimodal representation

is computed as

Unlike naive concatenation or early fusion strategies, the cross-modal transformer allows deep, contextual interactions between modalities. It captures joint distributions over visual and textual semantics, enabling the model to infer, for instance, stylistic affiliations from image–text alignments or historical shifts from textual descriptions linked with visual elements. Positional encodings and modality-specific tokens are prepended to each input stream to preserve modality identity, while allowing for flexible reweighting. This design allows the fused representation to serve not only as a classification feature but also as a semantic anchor for downstream modules, including style clustering, influence prediction, and canonicality estimation, ensuring that stylistic inference is grounded in both form and context.

We define canonicality as the extent to which a film scene aligns with curatorial standards of artistic, historical, or cultural significance. To construct supervisory signals, we curated a list of canonical films using metadata from institutions such as the Criterion Collection, the MoMA Film Archive, and major international retrospectives. Scenes sourced from these works were labeled as canonical with soft weighting to account for intra-film variability. Non-canonical scenes were sampled from a broader set of films lacking curatorial endorsement. Canonicality is modeled as a scalar variable learned via a regression head, regularized by entropy loss to avoid overconfident predictions. This approach allows the model to reason over a continuum of canonical relevance rather than a binary classification.

Influence is operationalized as a directed stylistic relationship from one scene to another, under the constraint of temporal precedence (i.e., the influenced scene occurs after the source). Ground-truth influence pairs were derived from film scholarship, directorial interviews, and expert metadata indicating acknowledged stylistic or narrative borrowings. Additionally, we included soft influence candidates based on shared ontological tags and stylistic cluster similarity. Each influence link is scored via a predictor that learns based on the fusion embeddings of both scenes, their ontology, and temporal distance. Chronological constraints are enforced to eliminate implausible causal directions. This formulation supports both binary evaluation and ranked influence retrieval for interpretive analysis.

To capture both the evolving stylistic configurations in art history and the institutional importance assigned to specific works, Styloformer integrates two complementary predictive heads. The first branch models the assignment of artworks to stylistic groups. These groups are treated as latent clusters in the embedding space

, where each cluster represents a learned prototype

for

. Given an artwork embedding

, the style classifier

computes a soft probability distribution over these

K clusters using a similarity-based attention mechanism. The output is a vector

representing the likelihood that artwork

a belongs to each stylistic mode:

This formulation enables a soft assignment model where artworks may express partial affinities with multiple stylistic traditions—an essential property in art history, where hybridization and influence are common.

To guide the learning of these representations, we define a clustering alignment loss that encourages each embedding to be geometrically proximate to the corresponding prototype

, weighted by the soft assignment. This is operationalized using a softmax-based formulation of contrastive clustering loss:

The loss function aligns embeddings with the closest stylistic centroid while still permitting soft boundary transitions between clusters. This is crucial in modeling periods such as late Gothic to early Renaissance, where boundaries are historically fluid.

In parallel, the canonical head

captures curatorial or institutional recognition by predicting whether a given artwork is part of a canonical reference set

curated by museums or experts. The head is implemented as a single-layer neural network with sigmoid activation, transforming the embedding

into a scalar value

representing the predicted canonicality:

This scalar encodes the canonicality score—how likely a work is to be institutionally privileged—thus introducing an expert-informed prior into the modeling process. Such priors help the model to differentiate between widely recognized stylistic exemplars and marginal or outlier works.

To supervise this module, we employ a standard binary cross-entropy loss over the reference labels

, where

if

and 0 otherwise:

This loss ensures that canonical artworks are assigned high scores, while non-canonical ones are suppressed. Notably, this component aligns machine-inferred features with human valuation structures, allowing the system to learn what makes an artwork “important” beyond stylistic similarity alone. The co-existence of stylistic soft clustering and binary curatorial scoring allows the model to operate at both emergent and institutional levels of art-historical interpretation, capturing both how artworks are grouped and which of them have historically mattered most.

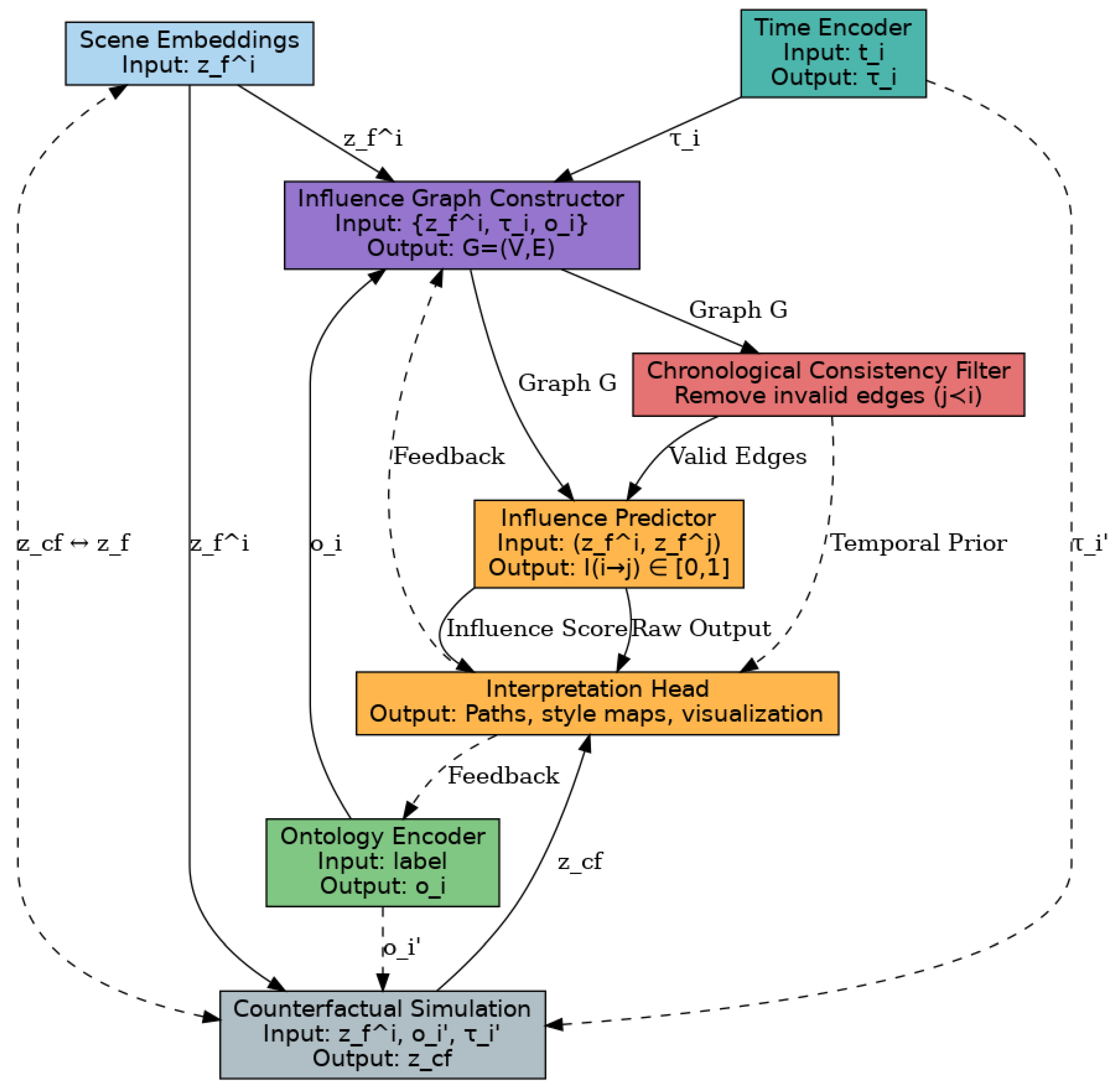

In addition to modeling static stylistic identity and curatorial relevance, the ability to capture directional influence among artworks is critical for reconstructing historical trajectories and aesthetic lineages (as shown in

Figure 2). To this end, Styloformer includes an influence modeling module designed to infer probabilistic influence scores between pairs of artworks based on their learned embeddings. We formulate this using a bilinear scoring function that evaluates the compatibility between two artworks

and

via a learned matrix

and bias term

. The score is passed through a sigmoid function to yield a confidence

, representing the likelihood that

influences

:

This formulation allows asymmetric influence detection, where

and

can differ, reflecting the temporal and stylistic asymmetries often found in real-world artistic relationships.

The model is trained on a set of labeled influence pairs,

, drawn from annotated corpora or heuristically derived from temporal proximity and metadata. We apply a binary cross-entropy loss over the predictions, where

if

is known to influence

, and 0 otherwise:

This loss function penalizes both false positives and false negatives, ensuring that the learned embedding space maintains separability for directional influence paths. By jointly optimizing with stylistic and canonical components, the model learns representations that are influence-aware but still stylistically and institutionally grounded.

Given the inherently subjective and historically layered nature of artistic influence in film, we designed a semi-supervised validation protocol to ensure the reliability of the influence prediction module. First, we constructed a manually annotated influence dataset using metadata from curated film archives such as the Criterion Collection and the European Film Gateway. These annotations were supported by citations in academic literature and film criticism, identifying explicit or stylistically traceable influence links between pairs of films. For example, director interviews and scholarly analyses were used to label known influence relations among auteurs across movements such as Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. Second, we incorporated weak supervision from ontology-based similarity and temporal precedence. When two artworks shared ontological descriptors (e.g., “existential minimalism”, “avant-garde narrative form”) and were chronologically ordered, we included them as soft positive pairs. These weak labels were used during training, while only the expert-annotated influence pairs were reserved for quantitative evaluation. We evaluated the module using standard binary classification metrics, including precision, recall, and AUC, on the expert-labeled subset. In addition, we conducted case studies where the model was asked to rank potential influences for a target film, and the top-ranked results were qualitatively assessed by two domain experts. This multi-tiered approach allowed us to validate the influence estimation component in a way that balances historical rigor with computational tractability.

To further enhance temporal consistency, we introduce a coherence regularization term that operates over chronologically adjacent pairs of artworks in the corpus

. This temporal smoothness loss ensures that embeddings of works produced in close succession do not exhibit abrupt transitions unless stylistically warranted. For each temporally ordered pair

, we apply the following

penalty:

This term encourages continuity in the latent space and acts as a temporal prior, preventing overfitting to isolated visual or textual anomalies. It also improves the model’s ability to recover smooth stylistic transitions and detect ruptures aligned with known art-historical shifts.

The total training objective integrates the three specialized losses—stylistic alignment, influence prediction, and canonicality classification—together with the temporal regularization term. We use a linear combination with coefficients

that are tuned on a held-out validation set:

All parameters are trained jointly in an end-to-end fashion using the AdamW optimizer with cosine learning rate scheduling. During training, mini-batches are sampled with locality constraints—preserving temporal and regional adjacency—to reflect realistic curation and historiographic progression.

3.4. Historiographic Navigation

This is an auxiliary module designed for interpretive reasoning. To harness the representational expressiveness of Styloformer for tasks grounded in art historical research, we propose a strategic inference framework termed Historiographic Navigation. This strategy integrates symbolic priors, structured timelines, curatorial influence, and historiographic networks into a machine reasoning protocol capable of generating interpretive, style-aware, and temporally coherent hypotheses across diverse visual corpora (as shown in

Figure 3).

To support semantically grounded and historically coherent reasoning, our architecture incorporates two structural priors into the representation process: ontological anchoring and temporal encoding. These priors embed domain-specific knowledge and chronological context directly into the latent space, enabling the model to align its internal representations with art historical concepts and diachronic transitions. Ontological anchoring starts by mapping each artwork

to a subset of conceptual descriptors

drawn from a curated domain ontology

. This ontology is a graph-based taxonomy of iconographic categories, stylistic schools, geographic affiliations, and patronage networks. The mapping function

retrieves this symbolic subset for a given artwork:

Each concept

is then embedded into a fixed vector space using a learned embedding matrix. These concept vectors are aggregated—either by averaging or via attention over

—to form a symbolic prior vector

, which is projected into the shared latent space using a linear map

:

This vector is injected into the transformer stack by modifying the attention mechanism, where it serves as a bias to query-key operations, thus emphasizing dimensions semantically aligned with domain-relevant ontological features. This conditioning enhances interpretability and robustness, particularly in low-data or cross-domain scenarios.

In parallel, we introduce temporal encodings to preserve historical ordering and enable the model to generalize across stylistic phases. Each artwork is associated with a timestamp

representing the date or period of creation. Rather than treating this as a raw scalar, we normalize it using corpus-wide statistics:

This standardization maps all temporal positions into a zero-centered, unit-variance range, making them suitable for projection. We then encode

using sinusoidal position embeddings, following the positional encoding schema of transformer models:

The use of multiple frequencies

allows the model to learn temporal hierarchies, capturing both short-term transitions and long-term stylistic epochs. These temporal vectors are added element-wise to the input representations of each modality—visual, textual, metadata, and symbolic—ensuring that temporal awareness is shared across the entire fusion process. The dual encoding of ontological semantics and normalized time thus enables the model to reason over structured conceptual spaces while maintaining diachronic alignment, supporting tasks such as influence prediction, canonicality estimation, and historiographic simulation.

To capture the flow of stylistic development and inter-artwork relationships over time and space, we design a multi-faceted influence and diffusion modeling module that integrates trajectory continuity, temporal causality, and geographic locality. First, to ensure stylistic coherence across narrative or diachronic sequences, we define a stylistic trajectory regularizer over temporally ordered embeddings. Let

be the sequence of latent representations of artworks sorted by creation time. We introduce a regularization loss that encourages embeddings to evolve smoothly over time by penalizing abrupt transitions in latent space and rewarding alignment in directional drift. The loss takes the form

where the

term ensures continuity and the inner-product term favors consistent semantic orientation, with

controlling the relative contribution. This formulation reflects the historical intuition that stylistic change, while inevitable, often unfolds through gradual mutation rather than radical rupture.

Next, to enforce chronological plausibility in influence estimation, we define a constraint loss based on timestamp order. If the model predicts a high influence score

where the source artwork

was created after the target

(

), this implies an implausible retrocausal relationship that must be penalized. We define the chronological loss as

where

is the indicator function and the logarithmic formulation ensures that larger violations are penalized more steeply while still providing gradient flow for small infractions.

Beyond individual pairwise influence, we incorporate geographic priors to regulate how influence propagates across spatial regions. Each artwork

is assigned a region centroid

or

based on origin metadata. To capture the decay of stylistic transmission with spatial distance, we use a radial basis function kernel to define a semantic diffusion weight between regions:

This diffusion kernel reflects the assumption that influence is more likely to occur between geographically proximate regions due to material circulation, artist mobility, or political contact. We then reweight the raw influence score between artworks using the diffusion kernel to obtain a locality-aware influence estimate:

This mechanism biases the model toward plausible influence pathways that follow known historical patterns of artistic transmission, such as the eastward spread of Islamic ornamentation or the transalpine flow of Renaissance perspective techniques.

This counterfactual simulation also enables interpretive flexibility by revealing how institutional framing may influence canonicality judgments. It allows the model to hypothetically reposition non-canonical works within alternative stylistic or historical contexts, supporting critical reflection on curatorial biases.

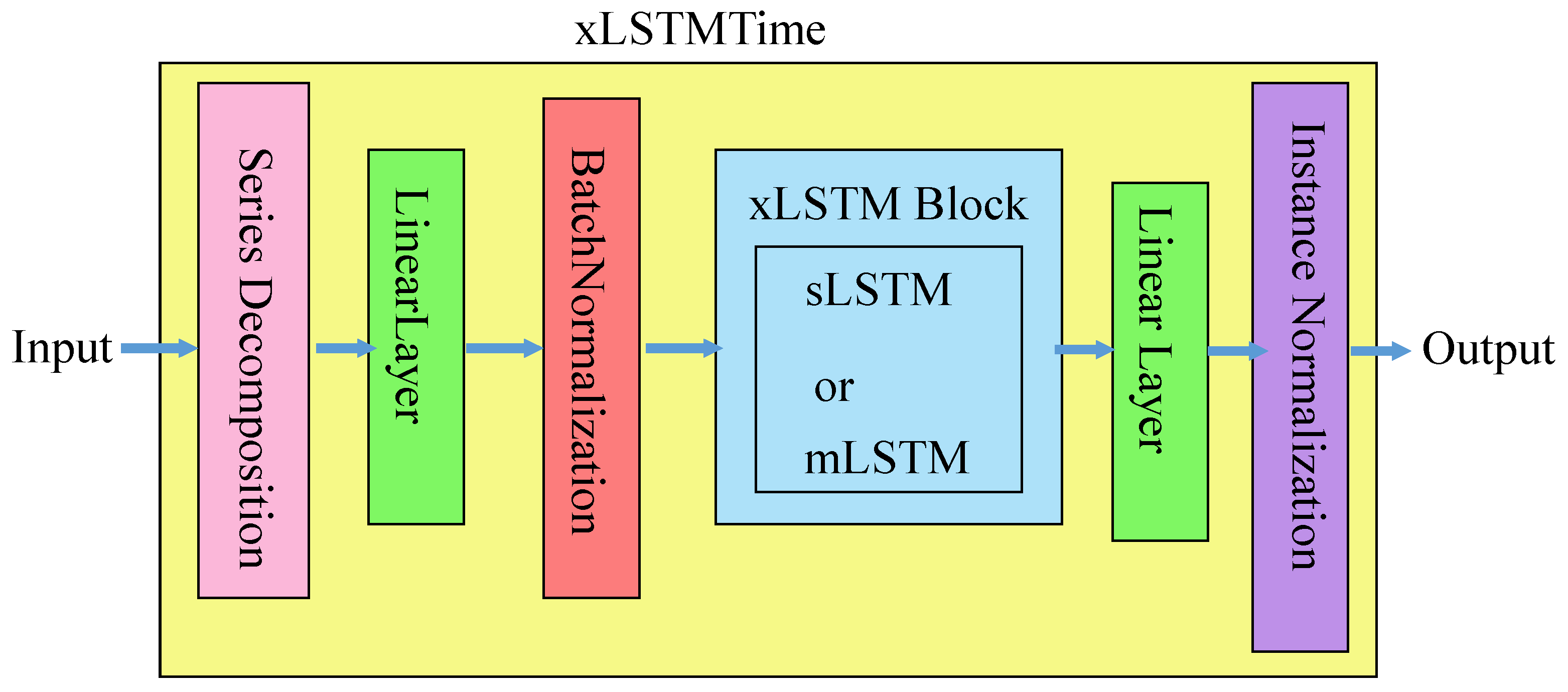

To simulate interpretive flexibility in historical reasoning, we introduce an adaptive control mechanism over attention, influence flow, and hypothetical transformations. The model dynamically modulates its inference behavior by conditioning on canonicality scores, recursively generated influence chains, and algebraic manipulation of stylistic embeddings (as shown in

Figure 4). First, attention mechanisms are adjusted using canonicality score. In traditional transformer attention, the query matrix

Q governs which keys receive emphasis. To bias this process toward historically validated artworks, we shift each query vector with a scalar multiple of the predicted canonicality score

:

where

is a learned scaling factor and

is a broadcast vector. This modulation increases the likelihood that high-canonicality items shape representational updates, while still preserving differentiability for end-to-end training.

To prevent overfitting to institutionally dominant exemplars and improve generalization to underrepresented styles or regions, we regularize the canonicality predictions via entropy minimization. The goal is to avoid excessive model confidence in curatorial binaries while still maintaining discriminative gradients. Let

denote the set of artworks considered authoritative. We define the entropy penalty as follows:

This term encourages a balanced distribution over

, thus reducing confirmation bias in downstream reasoning steps.

For long-range historiographic interpretation, we simulate plausible influence trajectories using recursive chain construction. Beginning from a seed artwork

a, we iteratively select the most probable influence successors based on the learned prediction score

, forming a

k-step influence path:

This allows the model to simulate how styles may propagate across periods, schools, or geographies, and enables interpretability via influence chaining.

To simulate counterfactual scenarios—such as how an artwork would be classified if created in a different style—we enable latent vector perturbation. Suppose artwork

is embedded in a stylistic cluster

j, and we seek its projection into another style

k. We define a vector transformation based on cluster centroids

and

:

The scalar

controls the strength of counterfactual interpolation. This synthetic embedding

can be reclassified, recontextualized, or decoded to generate interpretive rationales, supporting exploratory scholarship and digital curation. These modeling components—attention modulation, path-based traversal, and latent algebra—are optimized jointly through a composite loss:

This strategy enables trajectory-constrained, ontology-aware, and counterfactually flexible inference across complex art historical corpora.