Abstract

Mine water inrush remains one of the major hazards threatening the safety of coal mining operations. To assess the feasibility of integrating transient electromagnetic (TEM) and direct-current (DC) methods for advanced detection in underground settings, a three-dimensional geoelectric forward model for both techniques was developed in COMSOL Multiphysics based on the fundamental principles of electromagnetic prospecting. The model was used to examine the electromagnetic responses of water-rich anomalies surrounding mine roadways under different source configurations and spatial positions. Comparative analyses show that both DC and TEM methods effectively detect water-bearing targets within 40 m of the roadway, whereas TEM exhibits superior sensitivity at greater distances. TEM achieves its highest sensitivity when the anomaly is located within an azimuthal range of 30–45°. The characteristic response patterns derived from the simulations were applied to interpret field data acquired at the Tashan Coal Mine. The interpretation successfully delineated the presence and orientation of the water-bearing body ahead of the excavation face, and subsequent underground drilling verified the accuracy of the predictions. These findings demonstrate that COMSOL-based electromagnetic forward modeling provides a reliable framework for interpreting advanced geophysical detection data and is feasible for practical applications in mine water-inrush hazard assessment.

1. Introduction

As the depth of intelligent coal mining in China continues to increase, mine water inrush accidents have become one of the primary hazards threatening miners’ lives and safe production [1,2,3]. Consequently, determining the location of water-rich zones ahead of the mining face has become a crucial task in ensuring coal mine safety [4]. Due to the high salinity and low resistivity of mine water, the spatial distribution of water-bearing anomalies can be detected non-invasively using geophysical techniques. Methods such as seismic exploration, transient electromagnetic (TEM) surveys, direct-current (DC) resistivity, ground-penetrating radar (GPR), induced polarization, and infrared thermography utilize these contrasts in physical properties to image subsurface structures [5,6,7,8,9]. Among these, the DC and TEM methods are particularly suitable for underground conditions because they can evaluate subsurface resistivity distributions and identify conductive anomalies while being adaptable to the constrained geometry of mine tunnels [10,11,12]. As a result, both have become effective tools for detecting water-bearing zones ahead of working faces [13], and are widely applied in aquifer evaluation [14,15,16,17], goaf exploration [18,19], saltwater intrusion [20], and mineral exploration [21]. The joint forward modeling of these two methods can leverage their complementary strengths, enhance the reliability of interpretation results, and assist in obtaining more accurate resistivity inversion outcomes [22].

The transient electromagnetic method and the direct-current method are complementary in interpreting the detection results of water-containing anomalies around the tunnel. The DC method, while less sensitive to the geological information in front of the face, responds equally to conductive and resistive structures and can effectively distinguish anomalies located before and behind the survey line. Conversely, the TEM method is more sensitive to forward anomalies, but its magnetic diffusion field is significantly affected by the presence of conductive water-bearing bodies [23]. The combination of these two approaches improves the interpretive accuracy of anomaly detection. However, unlike surface half-space conditions, underground geoelectrical detection is influenced by the full-space geometry of tunnels and surrounding strata. Therefore, investigating the electromagnetic response of low-resistivity anomalies within a mine full-space configuration is of great importance for understanding current diffusion mechanisms and for improving the interpretation of underground geoelectric data.

Based on geological and detection data from the 30,517 working face of the Tashan Mine, this study employs COMSOL Multiphysics 6.1 to establish a three-dimensional full-space geoelectric forward-modeling framework that couples DC and TEM simulations. The model is used to analyze the electromagnetic response characteristics of water-bearing anomalies under various geometric conditions, and the numerical results are validated using actual tunnel detection data and borehole verification. The findings confirm that numerical forward modeling can be a powerful method for accurately delineating water-rich zones ahead of the working face.

The innovation of this study lies in the establishment of direct-current (DC) and transient electromagnetic (TEM) geoelectric forward models in mine tunnels for advanced detection of water-rich areas in the tunnels. Unlike previous studies that usually focus on DC or TEM separately, the core of this work is to exploit the complementary sensitivities of these two techniques to improve the accuracy of interpretation of subsurface anomalies. Using COMSOL Multiphysics, we simulated the electromagnetic response of water-rich anomalies in a real mine environment. This approach not only addresses the challenge of low resistivity anomalies in confined environments, but also provides a reliable method to accurately delineate the water-bearing zone in front of the mining face. In addition, the numerical simulation results were verified using actual field data from the Tashan Mine to ensure that the research results are both realistic and applicable to actual mining scenarios.

Compared with earlier research, the present study makes several key advancements. Xie et al. mainly dedicated to optimizing DC power supply configuration and solving lateral interference in tunnel environment, but there is a lack of actual data verification [24]. Li et al. utilize borehole-ground DC methods for aquifer delineation [25]. Guo et al. studied the effects of electrical properties, distance, and size on transient electromagnetic response, but did not consider the effect of angle [26]. Sun et al. combined drilling with TEM to overcome the size limitation of transient electromagnetic detection of drilling, but did not discuss the relationship between the detection effect and the angle of the anomaly [4]. Above study integrates the DC and TEM methods for a comprehensive analysis of water-rich zones. Our approach also differs by offering a more complete understanding of how the full-space geometry of a mine tunnel influences the propagation of both electric and magnetic fields, which has significant implications for pre-mining water detection. Furthermore, unlike earlier studies that rely on either surface or borehole-based methods, our work validates the combined modeling results with field measurements, providing a more holistic and accurate method for geophysical exploration in mining environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Principles and Error Verification of Direct-Current Forward Modeling

2.1.1. Direct-Current Method Detection Principle

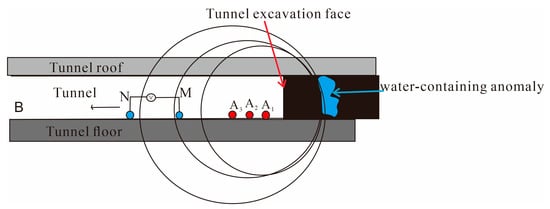

Currently, the direct-current (DC) three-pole method is widely utilized for subsurface detection [24]. Typically, this configuration comprises three current electrodes (A1, A2, A3) and a pair of potential electrodes (M, N) arranged within the tunnel, while the return electrode (B) is positioned at effective infinity to simulate semi-infinite boundary conditions. When a current is applied to the A pole, an equipotential surface with the A pole in the center and equal potential values will be formed to reflect the electrical structure of the underground space. At the same time, the measuring electrode will gradually move equidistantly backward along the direction of the tunnel (as shown in Figure 1). By collecting data recorded at different locations, the apparent resistivity ρs at each measurement location can be calculated according to Equation (1) [27]:

where , (Ω·m) is the apparent resistivity; (V) is the potential difference between different equipotential surfaces; I (A) is the injected current.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of mine direct-current method.

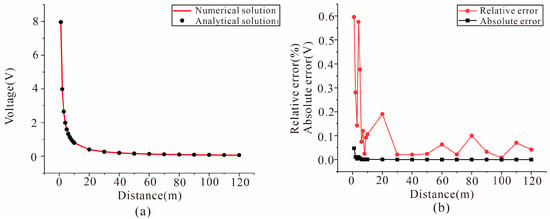

2.1.2. Error Assessment in Direct-Current Forward Modeling

In this study, COMSOL is used to construct a three-dimensional point-source error-testing model. The computational domain is defined as a sphere with a radius of 100 m and a uniform conductivity of 0.01 S/m. An infinite-element layer with a thickness of 10 m is applied to approximate the infinite boundary condition, and a current of 1 A is injected. To balance computational accuracy and efficiency, the mesh size is set within the range of 0.45–10.5 m. By comparing the numerical results with the analytical solution, the maximum relative error is 0.5957%, and the maximum absolute error is 0.0474 V, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Comparison of numerical solution and analytical solution; (b) absolute error and relative error.

In Figure 2b, the absolute error and relative error are calculated as follows:

where U (V) is absolute error, (%) is relative error, (V) is analytical solution, (V) is numerical solution.

2.2. Transient Electromagnetic Forward Modeling and Error Analysis

2.2.1. Principle of Transient Electromagnetic Detection

Mine transient electromagnetic (TEM) apparent resistivity is widely used to characterize and detect the electrical structure of anomalous bodies and serves as a primary tool for analyzing transient responses [26,28]. Currently, two main calculation approaches are employed: late-time apparent resistivity and full-time apparent resistivity. In this study, the late-time apparent resistivity method is adopted. For a full-space medium, the expressions for the vertical component Bz of the magnetic induction and the corresponding induced electromotive force ε are given by [29]:

where t is the observation time (s); μ is the magnetic permeability, typically taken as the vacuum permeability (H/m); I is the transmitted current (A); r is the radius of the transmitting loop (m); ρ is the uniform full-space resistivity (Ω·m); and S is the effective area of the receiving coil (m2), the dimensionless parameter x is defined as: , the error function is expressed as: .

and are the kernel functions of Bz and ε, respectively. In the late stage, x approaches 0, and a Taylor series expansion yields:

From this, the late-time full-space apparent resistivity derived from Bz and from can be obtained:

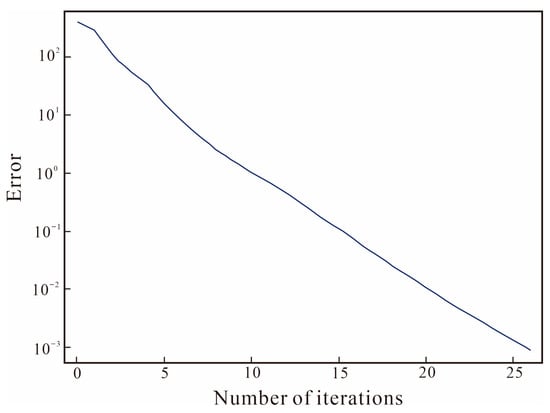

2.2.2. Error Analysis of Transient Electromagnetic Forward Modeling

COMSOL is used to establish a three-dimensional uniform full-space stratigraphic model. The model is defined as a cylinder with a radius of 100 m and a length of 150 m, containing a 30 m-long tunnel and a 40 m × 40 m × 30 m water-bearing anomalous body. The conductivity of the air is set to 0.01 S/m, while the conductivity of the water-bearing anomaly is set to 0.07 S/m. A coil of dimensions 1.5 m × 1.5 m is positioned in front of the tunnel, with 10 turns and a current of 3 A applied. The simulation uses a transient calculation method, with the finite difference time domain (FDTD) method employed for the solution. As the number of iterations increases to 25, the error is gradually reduced to 10−3 (shown in Figure 3). The calculated results meet the accuracy requirements for the simulation.

Figure 3.

Error accuracy change curve as the number of iterations increases.

3. Results

3.1. Direct-Current Method Detection Forward Simulation

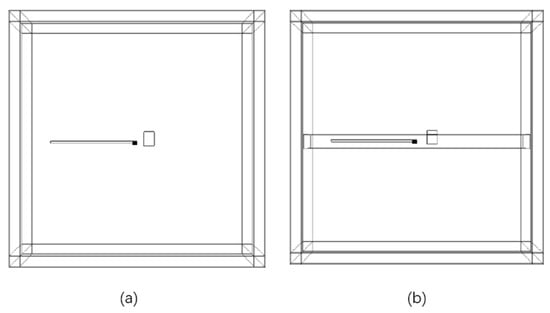

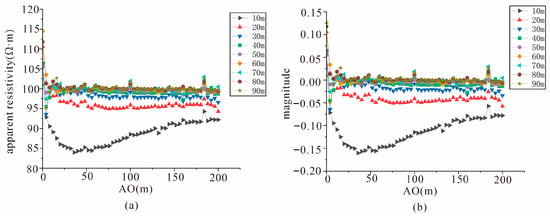

Because the direct-current method generates a series of equipotential surfaces that expand outward with distance, changes in the orientation of a water-bearing anomaly located at the same radial distance do not affect the measured response. Therefore, this study focuses solely on the response characteristics of low-resistivity anomalies at different distances from the water-bearing body under both uniform and layered conditions. The specific model is shown in Figure 4. The parameters of the uniform full-space model are set as follows: the uniform full-space stratum is set to a cube with a side length of 500 m, the conductivity is set to 0.01 S/m. the tunnel is set to a cuboid with a length of 250 m and a cross-sectional size of 6 m × 6 m, and the measurement line length is set to 200 m. The size of the water accumulation model in the goaf is set to a 30 m × 40 m × 40 m cuboid, the conductivity is set to 1 S/m, and the current size is set to 1A. The measuring electrode layout spacing is 4 m. A COMSOL parametric sweep is used to simulate the variation in distance between the point current source and the anomalous body, ranging from 10 m to 90 m at 10 m intervals. The resulting apparent resistivity curves and amplitude variations corresponding to these distance changes are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the direct current method model: (a) uniform full-space model; (b) layered formation model.

Figure 5.

DC method uniform full-space apparent resistivity and amplitude change curve: (a) apparent resistivity change curve; (b) amplitude change curve.

It As shown in Figure 5, variations in the distance between the water-bearing anomaly and the source in a uniform full-space model produce clear responses in both the apparent resistivity and amplitude curves. Overall, the apparent resistivity curve changes relatively smoothly with increasing AO. However, when the source–anomaly distance is small (10 m), a pronounced low-resistivity anomaly is observed. At this distance, the minimum apparent resistivity reaches 83.96 Ω·m, which is significantly lower than the background resistivity of approximately 100 Ω·m, with a corresponding amplitude variation of 0.16. This amplitude change reflects the strong disturbance in the electric field distribution induced by the conductive water-bearing anomaly. As the distance between the current source and the anomaly increases, both the anomalous response and amplitude effects gradually diminish. When the distance exceeds 40 m, the apparent resistivity and amplitude curves stabilize and approach the background values. These observations indicate that the source–anomaly distance is a key factor controlling the strength of the anomalous response.

By combining the apparent-resistivity variation (Figure 5a) together with the corresponding amplitude responses (Figure 5b), we observe that both parameters display highly consistent spatial patterns. This similarity arises because each is controlled by the same geometric attenuation associated with current diffusion in a uniform full-space. When the water-bearing anomaly is located near the current electrode, it generates a pronounced low-resistivity response accompanied by distinct extrema in the amplitude curve. These coincident features reflect the localized enhancement of the electric field produced by the conductive anomaly, thereby improving the detectability of small-scale conductive bodies at short source–receiver offsets.

As the anomaly is displaced progressively farther from the source, the amplitudes of both response curves decrease systematically. This behavior reflects the inherent spatial decay of the electric field, which decreases as a power-law function with increasing distance. Under large-offset conditions, the anomaly related perturbations become increasingly masked by the background field, thereby reducing the sensitivity to deeper or more distant targets. The similar variation trends observed in Figure 5a,b are therefore a direct consequence of their shared dependence on geometric spreading and field attenuation in a homogeneous medium.

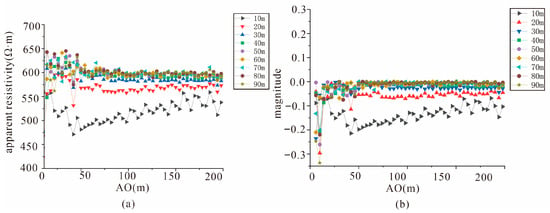

Under layered geological conditions, the original model parameters are retained, but an additional coal seam measuring 400 × 640 × 40 m is introduced adjacent to the roadway and the water-bearing anomaly. The coal seam resistivity is assigned a value of 600 Ω·m, and the updated model configuration is illustrated in Figure 4b. The measurement setup is identical to that used in the homogeneous case. Following forward modeling, the apparent-resistivity variation curve and the corresponding amplitude-change curve are obtained, as presented in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Apparent resistivity and amplitude change curves of layered formations: (a) apparent resistivity change curve; (b) amplitude change curve.

As shown in Figure 6a, the apparent resistivity curves fall within the range of 450–700 Ω·m. A pronounced low-resistivity response is observed near the current electrode, and the curves gradually converge toward the coal-seam resistivity of approximately 600 Ω·m as the AO distance increases. At short offsets, the apparent resistivity curves corresponding to different anomaly distances exhibit substantial dispersion, whereas at larger offsets they progressively converge toward the background resistivity. The most prominent low-resistivity anomalies occur when the anomaly lies 10–30 m from the source. In this interval, the apparent resistivity varies between 471 Ω·m and 568 Ω·m, with an absolute change of 0.05–0.21 and a maximum relative variation of 16.7%. At greater distances (40–90 m), the low-resistivity response weakens markedly, and the extrema of the curves decrease and shift slightly outward. This attenuation indicates the progressive reduction in coupling strength between the water-bearing anomaly and the surrounding current field.

Figure 6b indicates that the absolute amplitude change reaches its maximum when the water-bearing anomaly is located closer to the current-injection electrode. As the AO distance increases, the amplitude-change curve decays monotonically toward zero, reflecting the progressive weakening of the low-resistivity response with increasing separation from the anomaly. At larger offsets, both the apparent-resistivity and amplitude-change curves become increasingly stable, suggesting that although a long-range low-resistivity signal may still provide early warning, it becomes difficult to accurately determine the anomaly’s specific location. These results further indicate that an apparent-resistivity change exceeding an absolute value of 0.05 can be regarded as diagnostically meaningful. Based on this threshold, the effective detection range of the direct-current method for advanced prospecting is approximately 10–30 m, whereas offsets of 40–90 m can still offer early-warning capability but require supplementary confirmation.

3.2. Forward Simulation of Transient Electromagnetic Detection

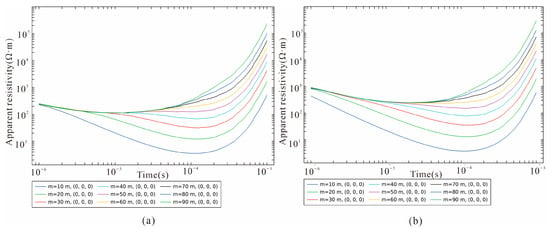

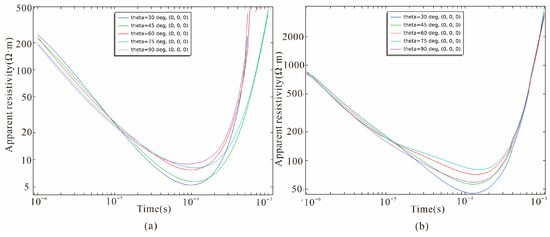

To facilitate comparison with the results obtained from the direct-current simulations, we also examined the identification characteristics of low-resistivity anomalies at varying distances in both a homogeneous half-space and within layered strata. Building on this analysis, we further incorporated the effects of anomaly orientation so that the two methods can better determine the location of the water-bearing anomaly body underground. The water-accumulation model in the goaf and its associated conductivity parameters are kept unchanged. To reduce computational cost, the cubic domain used in the direct-current forward model is simplified to a cylindrical formation with a radius of 100 m and a height of 150 m. The transmitter coil is assigned a radius of 1.5 m and consists of 10 turns. The water-bearing anomalies are oriented vertically relative to the horizontal plane. Measurement points are spaced at 10 m intervals along the roadway advance direction, covering offsets from 10 to 90 m ahead of the tunnel face. A parameterized scanning function in COMSOL is used to achieve dynamic monitoring of the anomaly response. The resulting apparent-resistivity change curve for the homogeneous formation is presented in Figure 7a. For the layered-strata model, the conductivity parameters of the added coal seam remain unchanged. The corresponding apparent-resistivity change curve is shown in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

Apparent resistivity change curve caused by distance change: (a) uniform whole space, (b) layered formation.

Figure 7a shows that in a homogeneous medium, the apparent resistivity exhibits a characteristic pattern: it first decreases and then increases with measurement distance. This behavior reflects the combined effects of current convergence and enhanced magnetic-dipole coupling associated with the near-field induction response of the low-resistivity water-bearing anomaly. When the receiving coil is either too close or too far from the anomaly, the contribution of the secondary field diminishes, causing the apparent-resistivity curve to rise again. However, the apparent-resistivity variation for the layered model (Figure 7b) is slightly higher at equivalent offsets than that observed in the homogeneous case. Moreover, the entire response curve shifts toward greater distances. This rightward shift indicates that the coal seam functions as a shielding or shunting layer: its higher resistivity restricts the penetration of primary current into the water-bearing anomaly, thereby reducing the strength of the secondary induced current. As a result, the electromagnetic coupling between the receiving coil and the anomaly weakens noticeably.

To more accurately determine the location of the water-bearing anomaly, we further investigated the variation in apparent resistivity produced by changes in anomaly azimuth while keeping all other parameters constant. In this analysis, the receiving coil distance was fixed, and the azimuthal orientation of the anomaly was varied through parameterized scanning at angles of 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°. Simulations were conducted for both homogeneous and layered formations. The resulting apparent-resistivity responses for these azimuthal configurations are presented in Figure 8:

Figure 8.

Apparent resistivity change curve caused by angle: (a) no stratum, (b) layered stratum.

Figure 8 shows that the apparent resistivity varies systematically over time, exhibiting an initial decrease followed by a gradual increase. This behavior reflects the rapid early-time induction of the strongly conductive water-bearing anomaly and the subsequent dominance of the background field at later times. In the homogeneous model (Figure 8a), increasing the azimuth angle from 30° to approximately 60–75° causes the entire curve to shift toward lower apparent-resistivity values, and the minimum resistivity moves slightly later in time. When the angle increases further to 90°, this trend weakens and begins to rebound. During the late-time window, the curves corresponding to azimuths of 45° and 75° converge along the outermost envelope, indicating the strongest anomaly identification at these orientations. In the layered model (Figure 8b), the early-time curves exhibit noticeable clustering, whereas the azimuthal differences become more pronounced near the extrema. The strongest anomaly identification near the minimum resistivity occurs at an azimuth of 30°, followed by 45° and 90°. The responses at 60° and 75° show weaker contrast. At later times, the curves begin to converge, indicating reduced sensitivity to azimuthal variations and diminished effectiveness in distinguishing the low-resistivity anomaly. Overall, assessment based on the extrema indicates that the most effective anomaly recognition occurs at azimuths of 30° and 45°, with moderate effectiveness at 60°, and comparatively weaker responses at 75° and 90°.

4. Practical Application

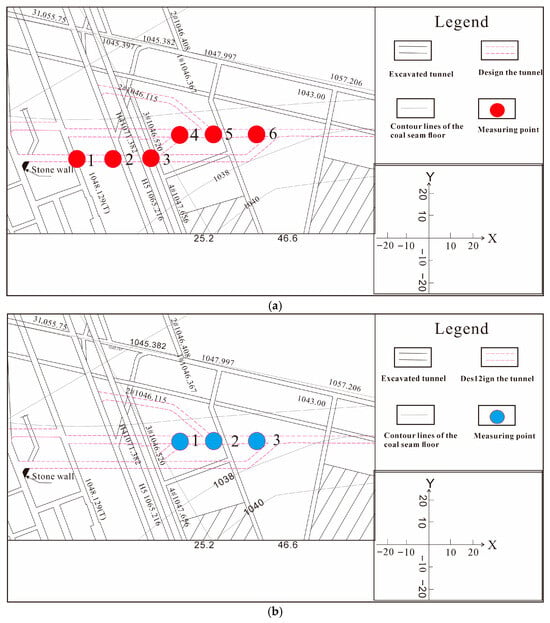

To validate the conclusions derived from geoelectric forward modeling for practical detection applications, underground field experiments were conducted at the Tashan Coal Mine. During the excavation of the 30,517 working face, water seepage was observed. To ensure the safe excavation of the tunnel, both the transient electromagnetic method and the direct current method were employed for advanced detection on site. In the field test, six measurement points were arranged for the transient electromagnetic method, and three measurement points were established for the direct current method. The layout of these measurement points is shown in Figure 9: (a) for the transient electromagnetic method and (b) for the direct current method.

Figure 9.

On-site experimental measurement line layout: (a) Transient electromagnetic side line layout, (b) DC method side line layout.

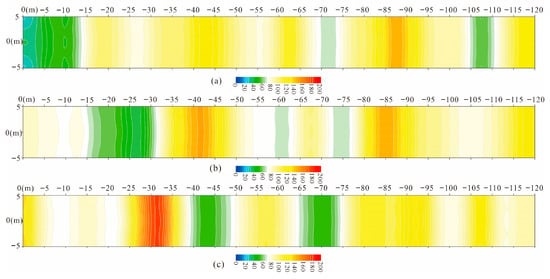

The field detection results obtained from the three DC-measurement lines—positioned along the left side, right side, and floor—are presented in Figure 10. On the left side, two distinct low-resistivity anomalies are identified between 40–48 m and 60–75 m. Additional low-resistivity zones are observed on both the right side and the floor, occurring between 0–13 m and 15–30 m. These anomalous regions are broadly consistent with the simulation results derived from the DC method. Subsequent verification through on-site drilling confirmed the presence of water at a depth of 22 m on the right side, with an inflow rate of approximately 5.5 m3/h, in agreement with the corresponding detection results. No cavity was encountered in the left-side borehole at 54 m; instead, wind and minor water seepage along fractures were observed. The discrepancy between the left-side drilling observations and the predicted anomaly location suggests that, at this distance, the DC method’s ability to resolve the position of the water-bearing anomaly diminishes—consistent with the forward-modeling findings.

Figure 10.

Direct-current method on-site detection results chart: (a) roadway floor, (b) left side of the roadway, (c) right side of the roadway.

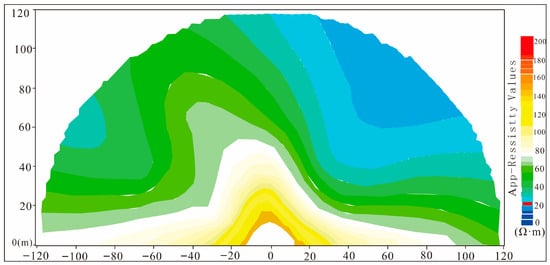

The results of advance detection using the transient electromagnetic method at the same location are presented in Figure 11. The figure shows that the detection coil exhibits a pronounced low-resistivity anomaly response at varying inclination angles. The anomaly is observed within a distance range of 60–120 m and azimuth angles between 20° and 75°. This distance and angle range aligns with the low-resistivity response characteristics of the water-bearing anomaly as predicted by the forward simulation using the transient electromagnetic method. Furthermore, the low-resistivity anomaly is most prominent within the azimuthal range of 30° to 60°, which is consistent with the simulation results. Subsequent verification by drilling at the anomaly location revealed water inflow ranging from 4 to 18 m3 per hour. Analysis of on-site conditions and geological data indicates that this anomaly is associated with the development of stratigraphic fractures and the presence of water-bearing zones.

Figure 11.

Transient electromagnetic field detection results diagram.

5. Discussion

This study systematically analyzed the response characteristics of water-bearing anomalies under different geological conditions through forward modeling of direct-current methods and transient electromagnetic methods. The results revealed a variety of influencing factors and their detection significance.

The simulation results of the direct-current method indicate that when the water-bearing anomaly is located near the power supply, significant low-resistivity anomalies appear in both the apparent resistivity and amplitude curves, with changes reaching 15% and 20% of the background resistivity. This demonstrates the method’s high sensitivity to near-field water anomalies. As the distance increases, the anomaly effect rapidly attenuates, and beyond 40 m, it begins to overlap with the background resistivity. This behavior is consistent with the attenuation law of the current field as observed in previous studies [30]. These results suggest that, in practical applications, the direct-current method is effective for identifying shallow water-bearing anomalies, but its ability to image deeper anomalies is limited. The transient electromagnetic method simulations further corroborate this conclusion. In a homogeneous medium, the apparent resistivity curve exhibits a typical pattern of first decreasing and then increasing with increasing measurement distance. The low-resistivity effect is prominent at short distances but attenuates quickly at longer distances. This behavior is attributed to the attenuation of the secondary induction field. While the transient electromagnetic method has high resolution for near-field water anomalies, its long-distance detection capabilities are constrained. Nevertheless, it remains effective at identifying extreme values of apparent resistivity, even at greater distances.

Under layered formation conditions, the high-resistance characteristics of the formation have an obvious shielding effect on the response of low-resistance anomalies [31,32]. The geoelectric forward modeling results of the direct-current method show that water-containing anomalies can still show identifiable low-resistance anomalies (absolute value of amplitude > 0.05) in the range of 10–40 m. However, at distances of 40–90 m, the anomaly signature is reduced to an early-warning indication, making precise localization difficult. Results from the transient electromagnetic method lead to a similar conclusion. The encapsulation of the water-bearing anomaly by the coal seam restricts the penetration of the primary field, thereby weakening the secondary induced current and shifting the apparent-resistivity extrema toward later times. This behavior indicates that the coal seam acts as a conductive barrier, diminishing electromagnetic coupling with the anomaly and consequently reducing detection resolution.

The azimuthal simulation results of the transient electromagnetic forward model show that when the anomaly deviates directly in front of the excitation source, the curve as a whole shifts to the low-resistance side, and the extrema migrate to later time windows. This behavior reflects a gradual reduction in detection sensitivity with increasing azimuth. In the absence of stratification, variations in azimuth still produce distinct anomalous responses. However, when strata are present, the late-time curves increasingly converge, leading to a diminished ability to discriminate azimuthal differences. These findings indicate that the transient electromagnetic method remains capable of locating water-bearing anomalies in practical applications. Although the sensitivity to azimuthal changes decreases at later times, anomaly orientation can still be inferred based on the migration of and variation in extrema in the apparent-resistivity response.

In summary, the direct-current (DC) method provides a strong low-resistivity anomaly response at short distances and is well-suited for identifying and issuing early warnings for small-scale water bodies in front of tunnels. The DC method, when used in conjunction with transient electromagnetic (TEM) measurements, is effective for anomaly detection in the 10–40 m range. Beyond this distance, greater reliance is placed on the TEM method to determine the distance to the anomaly. The TEM method not only compensates for the DC method’s limitations in terms of detection range, but also assists in determining the anomaly’s orientation. The combined use of both methods offers a robust approach to accurately pinpointing the location of water-bearing anomalies.

6. Conclusions

(1) In the geoelectric model error verification, the transient electromagnetic geoelectric forward modeling process shows that the error is reduced to 10−3 as the number of iterations increases. For the direct-current method, the error remains below 6% within 1 m, and subsequent errors decrease to less than 1%. These results demonstrate that the COMSOL software meets the accuracy requirements for electromagnetic geoelectric forward modeling and is suitable for tunnel geoelectric numerical simulations.

(2) Using COMSOL software, forward simulations were conducted for mine advance detection employing both the DC method and the TEM method. By establishing various geoelectric models for complementary verification, it was found that the optimal detection range for the DC method is 40 m, while the optimal azimuthal angle for the TEM method is between 30° and 45°. These findings provide a solid basis for effectively determining the location and distance of water-bearing anomalies during the data interpretation phase.

(3) Field tests of both the DC and TEM methods for advanced detection in coal mines were conducted, and the results were compared with simulation outcomes. The measured low-resistance anomaly areas closely matched the simulation results. Subsequent verification through drilling confirmed the presence of water-bearing anomalies, further validating the practicality and applicability of these methods.

In conclusion, the joint application of the DC and TEM methods significantly enhances the accuracy of water-bearing anomaly detection in tunnel environments. By combining the high sensitivity of the DC method for shallow anomalies with the extended range and orientation identification capability of the TEM method, this integrated approach offers a more comprehensive solution for locating and characterizing water-bearing zones. This joint method not only improves the precision of anomaly detection but also provides valuable early-warning capabilities, which are crucial for ensuring safe tunnel excavation and optimizing mine planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and S.P.; methodology, Y.H. and K.L.; software, K.L.; validation, Z.T. and L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. and K.L.; writing—review and editing, visualization, X.W. and K.L.; supervision, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National key research and development plan topics: Research and development of precise detection equipment and disaster risk monitoring technology for open-pit to underground mining disaster-causing bodies. Grant number is No. 2024YFC3013902.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to each author for their efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that none of the work contained in this manuscript is published in any language or currently under consideration at any other journal, and there are no conflicts of interest to declare. All authors have contributed to, read, and approved this submitted manuscript in its current form.

References

- Geng, H.; Peng, S.; He, T.; Xu, N.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Cui, X.; Du, W.; Li, Y.; Li, K. MSTC: A unified encoding method for geophysical big data retrieval. Earth Sci. Inf. 2025, 18, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, W.; Zeng, Y. Quantitative evaluation and prediction of water inrush vulnerability from aquifers overlying coal seams in Donghuantuo Coal Mine, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhao, C. Evolution of water hazard control technology in China’s coal mines. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ding, H.; Sun, Y.; Yi, X. Borehole transient electromagnetic response calculation and experimental study in coal mine tunnels. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 045112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Li, F.; Peng, S.; Sun, X.; Zheng, J.; Jia, J. Joint inversion of TEM and DC in roadway advanced detection based on particle swarm optimization. J. Appl. Geophys. 2015, 123, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xue, G.; Zhang, X. The feasibility of monitoring lagging water inrush by using parameter of polarizability. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 3186–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Yang, H.; Ran, H. Research status and development trend of mine electrical prospecting. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Liang, Y. Laterally constrained inversion of time-domain transient electromagnetic data and using it for detecting water-rich zones in coal mines. Mine Water Environ. 2025, 44, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhu, G.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, L. Research on the monitoring of overlying aquifer water richness in coal mining by the time-lapse electrical method. Energies 2024, 17, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.-H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Li, F. Electrical Prospecting Methods for Advance Detection: Progress, problems, and prospects in Chinese coal mines. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2019, 7, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qi, T.; Lei, B.; Li, Z.; Qian, W. An iterative inversion method using transient electromagnetic data to predict water-filled caves during the excavation of a tunnel. Geophysics 2019, 84, E89–E103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Shi, X.; Li, D. Study on Anomaly Characteristics of In-Advance DC Detection of Water-Accumulating Gob in Abandoned Mines. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Malekian, R.; Chang, J.; Su, B. Modeling of Whole-Space Transient Electromagnetic Responses Based on FDTD and its Application in the Mining Industry. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 2974–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.K.; Biswas, A. 2D Geo-electrical imaging for shallow depth investigation in Doon Valley Sub-Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. Fine and Quantitative Evaluations of the Water Volumes in an Aquifer Above the Coal Seam Roof, Based on TEM. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H. Fast Fisher Discrimination of Water-Rich Burnt Rock Based on DC Electrical Sounding Data. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Prevention and Control of Water Inrushes from Subseam Karstic Ordovician Limestone During Coal Mining Above Ultra-thin Aquitards. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Detection of Abandoned Coal Mine Goaf in China’s Ordos Basin Using the Transient Electromagnetic Method. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Hui, J. Coal mine goaf interpretation: Survey, passive electromagnetic methods and case study. Minerals 2023, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, İ.; Gündoğdu, N.Y.; Candansayar, M.E.; Soupios, P.; Vafidis, A.; Arslan, H. Determination and Evaluation of Saltwater Intrusion on Bafra Plain: Joint Interpretation of Geophysical, Hydrogeological and Hydrochemical Data. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2020, 177, 5621–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Electromagnetic methods for mineral exploration in China—A review. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 118, 103357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanuade, O.A.; Amosun, J.O.; Fagbemigun, T.S.; Oyebamiji, A.R.; Oyeyemi, K.D. Direct current electrical resistivity forward modeling using comsol multiphysics. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 7, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Xue, G.; Malekian, R.; Su, B. Diffusion Law of Whole-Space Transient Electromagnetic Field Generated by the Underground Magnetic Source and Its Application. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63415–63425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, R.; Cheng, J. A finite element numerical simulation analysis of mine direct current method’s advanced detection under varied field sources. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1273698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Hu, F. Experimental study on comprehensive geophysical advanced prediction of water-bearing structure of shaft. Acta Geod. Geophys. 2021, 56, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tan, T.; Ma, L.; Chang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, K. Response and application of full-space numerical simulation based on finite element method for transient electromagnetic advanced detection of mine water. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y. Simulation study on advanced detection using dual-borehole DC resistivity systems at different angles. Coal Geol. Explor. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tan, T.; Ma, L.; Chang, S.; Zhao, K. Numerical simulation and application of transient electromagnetic detection method in mine water-bearing collapse column based on time-domain finite element method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Deng, J.; Zhang, H.; Yue, J. Research on full-space apparent resistivity interpretation technique in mine transient electromagnetic method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2010, 53, 651–656. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, X.; Yue, J.; Hu, S.; Sun, C.; Lu, K.; Zhang, H.; Xi, D. Study on the influencing factors of direct current dipole array for tunnel advance detection and its application. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 58790–58799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Su, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Ran, H. Numerical simulation on transient electromagnetic response of separation layer water in coal seam roof. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Jiang, Z.; Xing, T.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Niu, Y. Transient electromagnetic perspective technology in the ultra-long coal mining face. J. Appl. Geophys. 2024, 223, 105353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).