Abstract

Hierarchical Federated Learning (HFL) requires a scalable and transparent incentive mechanism, yet existing on-chain approaches are too costly and centralized solutions lack trust. To address this, we propose CoFT, a hybrid framework that manages rewards off-chain using a hierarchy of state channels and a stablecoin while securing the system’s integrity with a single on-chain cryptographic anchor. This architecture dramatically reduces on-chain complexity from a prohibitive to a sustainable , enabling cryptographic verifiability, automated trustless payouts, and fair burden-sharing. CoFT thus offers a robust and economically viable blueprint for the financial infrastructure of large-scale, trustworthy collaborative AI ecosystems.

1. Introduction

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) with the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is poised to revolutionize healthcare, enabling data-driven analysis to provide personalized and efficient patient care [,]. The IoMT—a vast network of connected medical devices, sensors, and wearables—captures diverse, real-time patient data, creating immense opportunities for remote monitoring, personalized medicine, and clinical research [,,,]. This sector’s rapid expansion is underscored by its global market size, estimated at USD 230.69 billion in 2024 and projected to grow at a CAGR of 18.2% through 2030 [].

However, realizing this potential is hampered by critical security and privacy challenges. IoMT devices handle highly sensitive Protected Health Information (PHI), making data confidentiality paramount. Aggregating this data for AI training creates significant vulnerabilities to breaches and unauthorized access, which not only violates patient privacy but also erodes trust in healthcare systems []. Furthermore, stringent regulations like HIPAA and GDPR impose strict compliance demands on data handling, with substantial penalties for non-compliance []. To navigate this complex landscape, privacy-preserving paradigms are essential. Among these, Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a leading solution, enabling collaborative model training across decentralized data sources without centralizing raw, sensitive information.

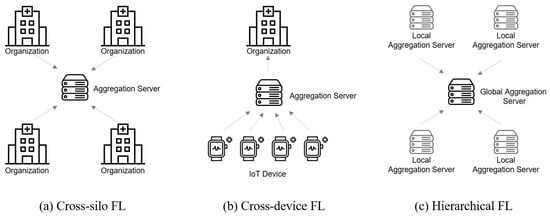

FL is particularly powerful when structured hierarchically. Hierarchical Federated Learning (HFL) [], depicted in Figure 1c, mirrors the natural structure of healthcare ecosystems. For instance, individual hospitals can act as intermediate aggregators for their internal devices, after which these hospitals can collaborate at a higher level. This multi-layered approach is highly effective for large-scale model training while maintaining strict privacy standards.

Figure 1.

An overview of Federated Learning topologies.

Despite its architectural advantages, the long-term success of HFL critically depends on robust incentive mechanisms to encourage sustained, high-quality participation [,]. While extensive research has focused on sophisticated methods for evaluatingcontributions (the how much), a significant gap remains in the design of a practical and scalable system for distributing the rewards (the how to pay). Existing blockchain-based proposals [,] often fall short due to the high volatility of cryptocurrencies, which undermines their viability as stable rewards. Moreover, the hierarchical nature of HFL introduces unique challenges, such as mitigating free-riding attacks, where less active organizations unfairly benefit from the contributions of others. This necessitates a specialized compensation framework that is not only fair in its evaluation but also efficient, transparent, and secure in its execution across a complex, multi-layered structure.

1.1. Our Contributions

To address this gap, we propose CoFT(Collaborative, Fair, and Transparent compensation framework), a novel compensation framework specifically designed for complex, multi-tier HFL ecosystems. Our framework establishes a robust framework for reward distribution that is scalable, efficient, and cryptographically verifiable. The major contributions of our work are as follows:

- Hierarchical Scalability: Our framework is natively designed to support complex, multi-level organizational structures inherent to HFL. The multi-layered channel design—from the top-tier Sub-Channels down to the contributor-level Virtual Channels—directly maps to real-world hierarchies (e.g., consortiums, hospital networks), ensuring the system can scale organizationally without compromising on logical integrity or efficiency.

- High Cost-Efficiency via Off-Chain Operations: We drastically reduce the blockchain transaction costs associated with reward distribution. By leveraging a hierarchy of state channels, all reward updates occur entirely off-chain during the T learning epochs, incurring zero gas costs. This hybrid approach transforms the prohibitively expensive complexity of a naive on-chain model (where every reward is a transaction) into a sustainable, additive complexity of (where costs are linear to the number of participants, not the project duration).

- Cryptographic Verifiability and Transparency: Our framework ensures that the entire compensation process is both transparent and mathematically verifiable. The final state of the system is committed to the blockchain via a single, immutable Merkle root. This allows any participant to independently and trustlessly verify their earned rewards by presenting a compact cryptographic proof to a smart contract, eliminating the need for a trusted third-party auditor.

- Automated and Trustless Payouts: We empower the ultimate contributors by removing counterparty risk. Through the use of dedicated on-chain Payout Contracts, contributors can permissionlessly claim their final, verified rewards directly from a smart contract. The payout is not dependent on the goodwill of the parent institution but is automatically enforced by the blockchain protocol, guaranteeing payment upon submission of a valid proof.

- Fair and Flexible Burden-Sharing: CoFT provides a mechanism for fairly distributing the financial burden of incentives among multiple top-tier institutions. The multi-funder Sub-Channel allows several project sponsors to collaboratively fund the reward pool and reconcile expenses based on pre-agreed-upon terms during the final settlement, making large-scale collaborative projects more economically viable.

1.2. Related Work

Incentive mechanisms are crucial for fostering participation in collaborative systems. Existing approaches can be broadly categorized into monetary, reputation-based, and blockchain-based frameworks.

1.2.1. Monetary and Reputation-Based Incentives

Monetary incentives aim to directly compensate contributors with financial payments. Research in this area often employs sophisticated theoretical frameworks to design optimal reward schemes.

- Auction-based approaches use competitive bidding to determine compensation, as seen in the work of Zhang et al. [,], who developed reverse auction mechanisms for FL.

- Contract theory-based approaches design optimal agreements to align incentives under asymmetric information []. This has been applied to HFL by He et al. [] and to address the straggler problem by Yang et al. [].

- Game theory-based approaches analyze strategic interactions among rational participants. Examples include coalition formation games for HFL [] and repeated game models to incentivize long-term cooperation [].

Reputation-based incentives, in contrast, use non-monetary scores to encourage long-term, high-quality participation. These systems assign reputation based on past performance, leading to future benefits like greater trust and more opportunities []. Some works propose hybrid models that combine reputation with game theory to defend against malicious clients or promote energy efficiency [,].

1.2.2. Blockchain-Based Incentives and Limitations

While the above methods provide robust techniques for valuing contributions, they often overlook the practical challenges of reward distribution. Blockchain technology has been proposed as a solution to create a transparent and automated reward system. Works by Wang et al. [] and Wu et al. [] leverage blockchain to securely record contributions and use smart contracts to automate payouts.

However, a critical review of the literature reveals persistent limitations. Many blockchain proposals do not adequately address the free-rider problem in complex HFL environments, nor do they offer an efficient settlement mechanism specifically designed for hierarchical structures without incurring significant on-chain overhead. Building upon the public goods perspective of Tang et al. [], who highlighted the importance of budget balance to mitigate free-riding, our work addresses these gaps. We introduce a practical stablecoin-based framework that utilizes a state channel hierarchy, including a channel factory [] and virtual channels [], to efficiently manage and settle rewards. This approach not only ensures the integrity of contribution records but also establishes a truly scalable and trustworthy incentive system that is currently lacking in the existing literature.

2. Technical Overview

This section provides an overview of the foundational Layer 2 and blockchain technologies that underpin our proposed framework. A clear understanding of these concepts is essential to appreciate the design and security of the hierarchical compensation mechanism presented subsequently.

2.1. State Channels

State channels [] are a Layer 2 scaling technique that allows participants to execute a large number of transactions off-chain, while retaining the security and finality guarantees of the main blockchain. A channel is governed by an on-chain smart contract that acts as an escrow and adjudicator.

- Establishment: A set of participants lock funds into the on-chain contract. This creates the channel’s initial state, , which is a cryptographically signed agreement on the initial fund distribution . The total locked funds, , remain constant throughout the channel’s life.

- State Transition: Once established, all interactions occur off-chain. Participants update the channel’s state by creating and co-signing state-update messages. A transition from state to is represented by a function , where is the transaction agreed upon by all parties. These off-chain updates are instant and incur no gas fees.

- Settlement: When participants wish to close the channel, they submit the final, mutually agreed-upon state, , to the on-chain contract. The contract verifies the signatures on this state and distributes the locked funds according to the final balances. This design is highly efficient, as only two on-chain transactions are required: one to open and one to close the channel.

2.2. Channel Factory

The channel factory [] is a design that optimizes the creation and management of multiple state channels. Instead of deploying a new smart contract for every channel (which is costly), a single factory contract is deployed to act as a manager and escrow for a multitude of dynamically created off-chain channels.

- On-Chain Collateral Pool: The factory contract, , pools the total liquidity from a group of providers . Each provider deposits funds into the contract, creating a single, large on-chain collateral pool: . This collateral remains locked on-chain, serving as the security deposit for all off-chain activities.

- Off-Chain Sub-Channel Allocation: The factory enables the creation of numerous logical sub-channels off-chain. For example, the pooled funds can be allocated to various receivers . Each provider can commit a portion of their deposit, , to a specific receiver . The fund conservation principle requires that the total allocation by a provider does not exceed their deposit: .

- Settlement: When a specific sub-channel is to be settled, its final agreed-upon off-chain state is submitted to the factory contract. The factory verifies the final state and updates the on-chain ledger accordingly, for instance by transferring the owed amount to the receiver . This allows for the settlement of many channels with minimal on-chain footprint.

2.3. Virtual Channels

Virtual channels [] are an extension of state channels that allow two participants who do not share a direct channel to transact off-chain through one or more common intermediaries. This creates a direct logical payment path without requiring the intermediary’s active involvement in every transaction.

- Establishment: Consider Alice (A) and Bob (B), who want to transact but only have direct channels with an intermediary, Ingrid (I): channel and channel . To open a virtual channel , Alice and Bob lock a portion of their funds in their respective direct channels as collateral for the virtual channel. This agreement is co-signed by Alice, Bob, and Ingrid.

- State Transition: Once the virtual channel is established, Alice and Bob can exchange an unlimited number of off-chain state updates directly with each other, just as in a regular two-party channel. For a payment of amount from Alice to Bob, they create and co-sign a new state where their balances are updated to . Ingrid is not involved in this update process.

- Settlement: To close the virtual channel, Alice and Bob present the final state of to Ingrid. Ingrid verifies the final state and updates the balances in the two underlying direct channels to reflect the net outcome of the virtual channel. For example, if Alice paid a net amount of to Bob, the final settlement would be:

- -

- In channel : Alice’s balance decreases by , and Ingrid’s increases by .

- -

- In channel : Ingrid’s balance decreases by , and Bob’s increases by .

Ingrid’s net balance change across both channels is zero, confirming her role as a trustless facilitator.

2.4. Stablecoins

A stablecoin is a cryptocurrency engineered to maintain a stable value by pegging it to an external asset, typically a fiat currency like the US dollar. This low volatility makes stablecoins a reliable unit of account, store of value, and medium of exchange within blockchain ecosystems, mitigating the price risks associated with traditional cryptocurrencies.

The state of a fiat-collateralized stablecoin system, , can be formally defined by its Total Supply (TS) and its Collateral Reserve (CR).

- Minting: A user creates new stablecoins by depositing an equivalent amount of fiat currency, v, into the reserve. This operation increases both the supply and the collateral, maintaining the peg: .

- Burning: A user redeems stablecoins for fiat currency by sending them back to be destroyed (burned). This operation decreases both the supply and the collateral: .

The integrity of the system hinges on the stability condition, which mandates that the collateral reserve must always be sufficient to back the entire circulating supply. This ensures that every stablecoin is redeemable for its pegged value.

These operations are overseen by a trusted entity (the administrator) responsible for managing the off-chain reserve and executing the on-chain minting and burning functions, thus providing a crucial bridge between the traditional financial system and the digital asset ecosystem.

3. Proposed Framework

This framework proposes a compensation mechanism suitable for an HFL environment. It is designed to efficiently distribute rewards, determined by the contribution level of each participating tier, by adding a blockchain-based layer on top of a traditional FL architecture. In this paper, hierarchical participants refer to large institutions with multiple sub-organizations or several institutions operating under a single foundation.

3.1. Framework Overview

The entire process is divided into four main stages: System Initialization, Channel Establishment, Channel Update, and Settlement. For clarity, the key notation and symbols used to define the framework are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations.

- System Initialization: At the project’s outset, all participants (Institutions, Sub-institutions, Contributors) are registered and assigned cryptographic keys. Concurrently, top-tier institutions deposit fiat currency, which the Administrator uses to mint an equivalent amount of stablecoins. These stablecoins serve as the collateralized reward pool for the entire project.

- Channel Establishment: A secure, on-chain Channel Factory is established by the top-tier institutions, who lock the minted stablecoins into this smart contract as the total reward fund. Following this, a multi-tier hierarchy of logical, off-chain channels is created. These channels connect the various participant tiers, establishing a pathway for efficient reward distribution without requiring constant on-chain transactions.

- Channel Update: Throughout the federated learning process, contributors train models with their data and submit them up the hierarchy. As contributions are evaluated each round, rewards are calculated. Instead of immediate on-chain payment, the state of the off-chain channels is updated to reflect the rewards accumulated by each participant. These updates are cryptographically signed off-chain, ensuring a secure and verifiable record of contributions over time.

- Settlement: Once the learning project concludes, the final, aggregated state of all off-chain channels is committed to the blockchain. Contributors can then initiate a reward claim by submitting verifiable proof of their final, signed channel state to a smart contract. Upon successful on-chain verification of this proof, the accumulated stablecoin rewards are transferred to the contributor, who can then redeem them for an equivalent value in fiat currency from the original collateral reserve.

3.1.1. Entities

The proposed framework involves several key entities that interact within the hierarchical federated learning and the blockchain-based compensation system. Each entity has distinct roles and responsibilities in the process, from funding and training to settlement and reward distribution.

- Institution (): An Institution is a participant at the top tier of the distributed learning system, acting as the root node for an independent tree structure. They are the primary sponsors of the collaborative project.

- -

- Funding: Initiates the process by depositing fiat currency to the Administrator for the minting of stablecoins.

- -

- Channel Establishment: Acts as the principal funder by depositing the main reward pool into the on-chain Channel Factory contract (implemented as the FundingRegistry). It then establishes off-chain Sub-Channels with its direct sub-institutions to allocate these funds logically.

- -

- Model Aggregation: Collaborates with other top-tier institutions to aggregate models received from lower tiers into a single global model.

- -

- Settlement: In the final stage, it co-signs the final state of the Sub-Channels, authorizing the release of funds from the on-chain contract to cover the total rewards paid to contributors.

- Sub-Institution (): A Sub-Institution is a participant in a tier below an institution, acting as an intermediary node in the hierarchy. This flexible role is crucial for both model aggregation and reward distribution logistics.

- -

- Model and Reward Relay: Receives local models from its child nodes, evaluates their contributions to calculate rewards , aggregates the models, and submits the aggregated result to its parent node.

- -

- Channel Management: Acts as both a parent and a child in the channel hierarchy. As a parent, it establishes State Channels or Virtual Channels to distribute its allocated reward pool to its children. As a child, it participates in channels created by its parent.

- -

- State Integrity: A child node of the root node is responsible for creating an individual Merkle Root from all the off-chain virtual channel states it manages. This is a critical step in creating the verifiable history of the entire system.

- -

- Settlement: During the settlement phase, it aggregates all reward liabilities from its descendants, propagates the total claim upwards, and deploys a dedicated Payout Contract on the blockchain, enabling contributors to claim their rewards directly and trustlessly.

- Contributor (): A Contributor is a participant at the lowest tier (a leaf node) of the system. They provide the foundational data and computational resources for the federated learning task.

- -

- Data Contribution: The primary role is to train a local model using their private data and submit the model parameters to their parent institution.

- -

- Off-Chain Agreement: Actively participates in a Virtual Channel, co-signing every state update to formally agree upon the reward accumulated in each learning round.

- -

- Reward Claim: Upon project completion, the Contributor interacts directly with the Payout Contract on the blockchain. They submit their final, co-signed channel state along with a cryptographic Merkle proof to securely and independently claim their total earned rewards.

- Administrator: The Administrator is the entity responsible for managing the stablecoin’s lifecycle, acting as the bridge between off-chain fiat currency and on-chain digital assets.

- -

- Minting: Issues stablecoins to an institution’s on-chain address after verifying the corresponding off-chain deposit of fiat currency.

- -

- Burning: Removes stablecoins from circulation by exchanging them back to fiat currency upon a contributor’s request.

- -

- Collateral Management: Guarantees the stability of the system’s currency by ensuring that the total supply of stablecoins in circulation is always fully backed by the collateral reserve, maintaining its value. This role can be fulfilled by a centralized entity or a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO).

3.1.2. A Hospital Network

To illustrate the model’s practical application, we consider a collaborative federated learning project among several hospital networks. The goal is to develop a state-of-the-art AI model for early-stage cancer detection from various types of medical imagery, without sharing sensitive patient data.

The key players in this hierarchical scenario are defined as follows:

- Institution (): The main headquarters of large hospital chains (e.g., National Medical Center, Regional Health Alliance). These institutions initiate and co-fund the project.

- Sub-Institution (): A flexible, intermediary role. This could be a specific branch hospital within a chain (e.g., Busan General Hospital as ) or a specialized department within that hospital (e.g., the Radiology Department as ).

- Contributor (): A Contributor, formally denoted as , is a leaf-node participant responsible for local model training. The indices clarify that this is the k-th contributor managed by the sub-institution . They are the ultimate recipients of rewards for their data and computation services. For brevity, in contexts where the parent is already specified (such as in the channel ), we may refer to the contributor simply as .

The collaborative process, mapping directly to our proposed framework, unfolds as follows:

- Funding and On-Chain Setup: The HQs of the hospital chains () form a consortium. They jointly fund the project by depositing stablecoins into the central on-chain Contract , creating the secure collateral pool.

- Off-Chain Channel Hierarchy Establishment:

- The HQs establish multi-funder Sub-Channels with their main branch hospitals , logically allocating the reward funds.

- Each branch hospital then creates multi-party State Channels with its internal departments (Radiology, Oncology, etc.).

- Finally, each department establishes a direct, two-party Virtual Channel with its internal research labs (the contributors).

- Federated Learning and Off-Chain Updates: The Contributors train local models on their anonymized patient image data. As they submit models up the hierarchy, their contributions are evaluated by the parent departments, and the state of their respective s is updated off-chain to reflect the earned rewards. This process repeats, with models being aggregated up to the HQs, which collaborate to create the improved global model for the next round.

- Settlement and Reward Claim: Once the global model reaches the target accuracy, the project concludes. The final state of all off-chain channels is anchored to the blockchain via a single hash .

- A contributor can now claim its total earned rewards. It submits a cryptographic proof of its final state to its parent sub-institution’s on-chain Payout contract.

- The contract automatically verifies the proof against the on-chain anchor, and upon success, transfers the rewards to the contributor’s wallet. The contributor can then redeem these funds for fiat currency through the Administrator.

3.2. Detailed Framework Description

In this section, we formally define the procedures for these channel operations. We assume that the participating organizations in the system form a forest consisting of multiple disjoint trees, each with a top-tier institution as the root node. In a forest with multiple disjoint trees, each tree is identified by its root node. Let be the tree with root node . The hierarchical identifier for a node in can be denoted as , where i ranges over the root nodes, j ranges over the children of the i-th root node ().

3.2.1. User Registration

This stage involves the preparation of all participants and the funding of the system.

- Registration: All Top-tier institutions, Sub-institutions, and Contributors are registered by the Administrator. During this process, each participant is assigned a public-private key pair (, ) for digital signatures.

- Stablecoin Issuance: The stablecoin issuance protocol details the secure conversion of off-chain fiat currency into on-chain stablecoins, which serves as the essential liquidity and collateral foundation for the entire off-chain channel network. This mechanism is necessary to lock required collateral off-chain before commencing channel operations.The procedure is defined as a multi-stage protocol involving the generalized system user U, the central administrator , and the stablecoin smart contract .

- Fiat Currency Deposit and Verification. The user U transfers an amount of fiat currency, , to a designated bank account managed by . This off-chain action serves as the collateral for the stablecoins.Upon receiving , performs two verifications:

- (a)

- Verifies the deposit amount and source.

- (b)

- Confirms that U is a valid, registered participant in the system.

Once verified, the sole authorized minter sends a transaction to on the blockchain. This transaction calls the mint() function, specifying the user’s public key address and the equivalent amount of stablecoins . - Minting and Transfer. executes the mint() function, which is secured to be callable only by . This execution has two main outcomes recorded in an atomic on-chain transaction:

- (a)

- The total supply of stablecoins TS on the blockchain increases by the amount .

- (b)

- The newly minted stablecoins are immediately assigned to U’s wallet, with the ownership recorded on the blockchain ( is the total stablecoins owned by U).

- Confirmation and Collateral Use. The user verifies the successful issuance and transfer by checking the blockchain. The minted stablecoins are then used as the security deposit for establishing off-chain channels. This final step provides an immutable, transparent record of the user’s liquid collateral, essential for trustlessly backing future reward payouts and channel operations.

3.2.2. Channel Establishment

- On-Chain Funding and Registration: The foundation of the system is a smart contract deployed on the blockchain, denoted , which serves two primary functions: a secure, collective escrow for the entire project’s reward pool, and an immutable registry for all participating high-level entities. This on-chain contract acts as the ultimate source of financial truth and the trust anchor for all subsequent off-chain interactions. All top-tier institutions and their direct sub-institutions must interact with this contract to join the project.

- (a)

- Funding and Registration: All participants commit funds and register on-chain through transactions to the contract.

- Top-tier Institutions: Each institution calls a deposit function on the contract to lock its share of the total reward pool, an amount in stablecoins.

- Sub-Institutions: Each sub-institution calls a registration function, depositing a minimal, recoverable stake and registering its public key with the contract. This stake serves as a security deposit for honest participation.

- (b)

- On-Chain State Solidification: Once the transactions are confirmed on the blockchain, the contract locks the funds and immutably records the participants’ information. The collective on-chain state, which we refer to as , is not a single signed object but is represented by the permanent data stored within the contract’s storage. This state includes:

- Participant Balances: A mapping from each participant’s address (, ) to their deposited balance (, ).

- Registered Public Keys: An immutable list or mapping of the public keys for all participating sub-institutions, essential for verifying off-chain signatures.

- Total Collateral: A public variable tracking the total amount of stablecoins locked in the contract, ensuring transparency of the total reward pool.

- Off-Chain Channel Hierarchy Establishment: This phase describes the process of setting up logical off-chain channels necessary for efficient off-chain transactions after the on-chain Channel Factory has been created. These channels do not involve actual on-chain transactions and only use the blockchain for final settlement.

- (a)

- Sub-Channel (): Once the on-chain channel factory is deployed, each top-tier institution establishes a logical sub-channel with each of its direct sub-institutions, . This channel functions as a multi-funder commitment ledger. Its primary purpose is to formally record the portion of collateral, denoted as , that each top-tier institution (for ) allocates to the specific reward pool managed by sub-institution .The total reward pool available to , which we denote as , is therefore the sum of these individual commitments from all M top-tier institutions:To ensure the solvency of the entire system, the fundamental principle of fund conservation must be maintained. The sum of all allocated reward pools across every sub-channel cannot exceed the total collateral, , locked in the on-chain channel factory. This governing relationship is formally expressed as:The establishment of this multi-party channel is a coordinated process:

- Coordinated Proposal: As the direct hierarchical parent, institution acts as the coordinator for creating the channel with . After an off-chain negotiation among all top-tier institutions to determine the allocations , constructs the proposed initial state and distributes it to all M top-tier institutions (including itself) and to the sub-institution .

- Multi-Party Agreement: To activate the channel, all participants must agree on the initial state. Each top-tier institution and the sub-institution independently verify the proposal and sign it with their respective private keys. They then return their signatures to the coordinator, .

- Initial State Finalization: Once has collected valid signatures from all participants, the initial state is finalized. This state serves as a binding off-chain agreement, detailing the public keys of all parties and the precise collateral committed by each top-tier institution to ’s reward pool.

- (b)

- State Channel (): Each parent node in the hierarchy, denoted , establishes a multi-party state channel with its set of K child nodes, . Here, serves as the unique identifier for the parent node. This channel acts as a logical ledger for cascading reward allocations, defining the total reward pool the parent commits to its direct descendants. The fund that allocates to this channel is derived from the balance it holds in its own parent channel (i.e., a or another channel).

- Proposal: The parent node proposes the initial state of the channel to all of its K child nodes. This proposal includes the total reward fund it is committing and requires a minimal deposit from each child.

- Agreement: To establish the channel, every child node must agree to the proposed state. Each child signs the state object with their private key, , and returns their signature to the parent. The channel is only activated once the parent collects valid signatures from all participants.

- Initial State: The collectively signed initial state, , represents a binding multi-party commitment. It specifies the parent’s total locked funds and the public keys and initial minimal deposits of all child participants.

- (c)

- Virtual Channel (): To facilitate direct reward distribution, each sub-institution establishes a two-party virtual channel, , with each contributor under its management. This channel serves as the primary ledger where a contributor’s rewards are incrementally recorded throughout the FL process. For notational clarity, we simplify the identifier for the k-th contributor managed by to just .The channel is established through a simple two-party agreement:

- Proposal: proposes the creation of the virtual channel to contributor . The proposal outlines the initial state, including the initial reward amount, , that is committing to this specific channel.

- Agreement and Activation: The contributor reviews the proposal. If they agree, they sign the initial state object with their private key, , and return their signature . Upon receiving the contributor’s signature, adds its own signature to finalize the agreement. The mutually signed initial state, , is then activated.

- Initial State: The initial state object defines the two parties and their starting balances. ’s balance begins with the committed fund , while the contributor starts with a minimal deposit . The state is only valid when co-signed by both participants.

Crucially, the sum of all initial funds committed by across all its virtual channels cannot exceed the total reward pool, , allocated to it from its parent channel (e.g., ). This ensures hierarchical fund conservation at every level:

- State Management: The state of all established off-chain channels—, , and —is managed through structured, cryptographically signed state objects. Any update to a channel’s state is considered valid only after it has been digitally signed by all participants involved in that specific channel, ensuring unanimous consent. These state objects are exchanged and stored exclusively off-chain for efficiency, but they are designed to be on-chain enforceable. The integrity and historical validity of these off-chain states are guaranteed through a Merkle Tree structure, which allows for efficient verification during the settlement phase, as detailed in the following sections.

3.2.3. Learning and State Update

With the channel infrastructure established, the system enters its primary operational phase: the iterative FL cycle. This section details the core off-chain mechanics designed to efficiently and verifiably link participant contributions to rewards in each training round (). The process ensures that compensation, ultimately drawn from the on-chain collateral , is distributed fairly. It encompasses three key procedures: the evaluation of contributions and calculation of rewards, the subsequent update of off-chain channel states to record accrued value, and the Merkleization process used to create a single, tamper-proof commitment to the system’s state history.

- Hierarchical Aggregation and Contribution Evaluation: The learning and evaluation process follows a bottom-up aggregation flow for model parameters and a top-down distribution flow for the updated global model. This cycle repeats for each training round, .

- (a)

- Local Model Training: At the beginning of a round, the leaf nodes of the hierarchy—the contributors —train models on their local data. Upon completion, they submit their updated local model parameters to their direct parent node .

- (b)

- Iterative Evaluation and Aggregation: Each intermediary parent node in the hierarchy performs a dual function:

- Contribution Evaluation: The parent node assesses the submitted models from its children. It applies a predefined incentive mechanism to calculate the reward, , earned by each child for the current round. While the specific mechanism (e.g., based on performance gain, data size, or Shapley values) is orthogonal to our proposed compensation framework, our system is designed to be agnostic to and compatible with any such scheme.

- Model Aggregation: After evaluation, the parent node aggregates the valid models received from its children (e.g., using Federated Averaging) to produce a single, higher-level model. It then submits this aggregated model up to its own parent. This evaluation and aggregation process is recursively repeated at each tier up to the root nodes.

- (c)

- Global Model Finalization and Distribution: Models that have been aggregated up to the top tier are collected by the institutions . A designated or randomly selected institution aggregates these models to create the new global model, . A convergence test is then performed.

- If the model meets the predefined performance threshold, the training process terminates.

- Otherwise, the new global model is distributed back down the hierarchy to all contributors for the next round of training ().

- Off-Chain Channel State Update: Upon the completion of each learning cycle, a new channel state is generated for the virtual channel . This process is entirely off-chain. The sub-institution proposes the new state, which reflects the contributor’s total reward amount earned up to that point. The new state, , becomes the single valid state of the channel only after it is co-signed by both parties.The state’s balances are always calculated based on the initial commitments. Let be the total reward amount for contributor at the end of epoch t. This value is updated each round by adding the new reward (e.g., , where is the reward for the current round only). The state at epoch t is then defined as:This state update mechanism is the core of the system’s efficiency. Critically, only the leaf-level virtual channels are updated during the iterative learning phase. The higher-level, multi-party channels remain unchanged after their initial setup. This design effectively defers the complex settlement costs to a single, final event, drastically reducing the number of on-chain transactions and associated fees.

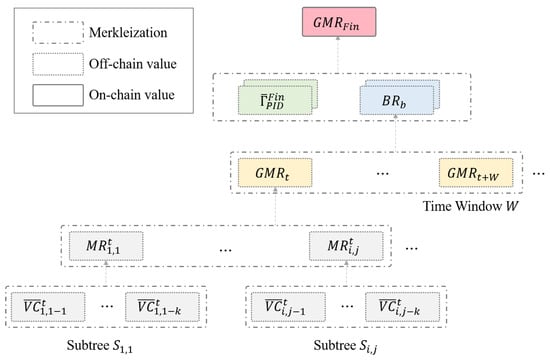

- Merkleization for Verifiable Off-Chain States: To guarantee the integrity of all off-chain state updates, the system constructs a multi-layered Merkle tree. This structure allows for the creation of a single, compact cryptographic proof for the entire history and final state of the system. Figure 2 illustrates this hierarchical construction. With the exception of the final root hash , all intermediate Merkle roots are generated and stored off-chain by the participants.

Figure 2. Hierarchical Merkle Tree Construction for Off-Chain State Aggregation.The aggregation process occurs in a bottom-up fashion across several layers:

Figure 2. Hierarchical Merkle Tree Construction for Off-Chain State Aggregation.The aggregation process occurs in a bottom-up fashion across several layers:- (a)

- Layer 1: Leaf Node Generation: In each round , every sub-institution hashes the latest valid state of each virtual channel it manages. These hashes, , form the leaf nodes of the tree.

- (b)

- Layer 2: Per-Epoch State Aggregation: The leaf nodes are then aggregated upward to create a single hash commitment for each training round.

- First, each computes its own Merkle root, , from the leaf nodes it generated. This root represents the entirety of state updates managed by that sub-institution in round t.

- Next, these individual roots are collected to form a Global Merkle Root for the epoch, . To ensure the uniqueness of each input, the hash of each ’s identifier is concatenated with its Merkle root before being included in the final tree.

- (c)

- Layer 3: Final Commitment and On-Chain Anchor: To minimize on-chain transactions, the per-epoch roots are not immediately published. Instead, they are batched and anchored in a single, final transaction after the entire FL process is complete.

- Block Root Batching: For scalability, the values are periodically grouped into blocks (e.g., spanning W epochs). The Merkle root of each block, , is calculated and stored off-chain. This step batches the historical proofs.

- Final Anchor Construction: Upon termination of the training, the final global Merkle root, , is constructed. This single hash, which is the only data permanently anchored to the on-chain contract , is composed of two distinct sets of data to enable comprehensive proof during settlement:

- All historical Block Roots (), which collectively prove the history of all reward updates in every channel.

- The hashes of all final State Channel states (), which prove the final liability path between intermediary nodes.

A contributor’s final claim requires proof against both components: one to validate the amount of their reward, and another to validate the legitimacy of the settlement path.

3.2.4. Settlement and Reward Claim

The settlement phase is initiated once the FL project reaches its termination condition. This phase finalizes all off-chain commitments and facilitates the on-chain claiming of rewards. The process unfolds in three major phases: off-chain finalization, on-chain settlement execution, and individual reward claims by contributors.

- Phase 1: Off-Chain Finalization (Bottom-Up): This initial phase occurs entirely off-chain to determine the final, cryptographically agreed-upon payment obligations at every level of the hierarchy, starting from the contributors and moving upwards.

- Virtual Channel Closure: The sub-institution and each of its contributors create and co-sign one final state for their channel, . This state records the contributor’s final total reward, , which is equal to the total reward amount from the final training epoch, .

- Liability Propagation via State Channels: The final reward amount, , triggers a cascading liability update that propagates up the hierarchy. A child node uses its channel to claim reimbursement from its parent. This process repeats recursively, shifting the financial liability upwards until each top-level sub-institution aggregates the total reimbursement amount required for its entire subtree, denoted .

- Top-Tier Reconciliation via Sub-Channels: The top-tier institutions now negotiate and co-sign a final state for each Sub-Channel, . This state serves as a verifiable, multi-party agreement that guarantees the reimbursement of to , specifying the final contribution from each institution .

- Phase 2: On-Chain Settlement Execution: The finalized off-chain states are now used to execute the transfer of funds on the blockchain.

- Settlement Transaction: An authorized party (e.g., ) submits the final, co-signed state to .

- Automated Fund Distribution: The contract programmatically performs two actions upon verifying the validity of the submitted state:

- (a)

- Return Unused Collateral: Any remaining funds are returned from the escrow to the original top-tier institutions .

- (b)

- Transfer to Payout Contract: The verified reimbursement amount, , is transferred to the address of the dedicated Payout Contract, , which was deployed by . This formally shifts the liability to the Payout Contract, which now holds the exact funds owed to the contributors of that subtree.

- Phase 3: Contributor Reward Claim: With the Payout Contracts now funded, contributors can directly and without permission claim their rewards.

- Submission of Proofs: To claim their reward , a contributor submits a proof to the corresponding Payout Contract, . This proof contains:

- -

- The finalized virtual channel state, .

- -

- The finalized state of the intermediary state channel, .

- -

- The Merkle proofs, and , that connect these two states to the globally agreed-upon on-chain anchor, .

- On-Chain Verification and Disbursement: The Payout Contract executes the logic detailed in Algorithm 1. It verifies the co-signatures on the submitted states and validates the Merkle proofs against the . This dual proof confirms both the reward amount and the legitimacy of the settlement path. If all checks pass, the contract marks the claim as processed to prevent re-entry and transfers the reward to the contributor’s wallet.

| Algorithm 1 Claim Validation Logic within Payout Contract |

| Require: Final state , final state , proofs , |

| 1: Let be the anchor stored in the main contract |

| 2: |

| 3: |

| 4: if Registry.IsClaimed() then |

| 5: return False {Prevent re-entry} |

| 6: end if |

| 7: |

| 8: {Payout contract owner is } |

| 9: {Assuming state has this structure} |

| 10: |

| 11: |

| 12: if or then |

| 13: return False {Check both signatures} |

| 14: end if |

| 15: |

| 16: if then |

| 17: return False Proof of reward |

| 18: end if |

| 19: |

| 20: |

| 21: if then |

| 22: return False {Proof of path} |

| 23: end if |

| 24: |

| 25: Registry.SetClaimed() |

| 26: Transfer() |

| 27: |

| 28: return True |

4. Discussion

In this section, we provide a detailed analysis of how our proposed framework achieves its key objectives. We connect the theoretical design choices discussed in Section 3 to the empirical performance validation presented in Section 5, analyze the framework’s security properties, and address its practical feasibility and limitations.

4.1. Hierarchical Scalability and Cost Efficiency

A primary challenge in large-scale HFL is modeling complex organizational relationships without incurring prohibitive on-chain costs. Our framework’s multi-layered channel architecture directly mirrors real-world hierarchies.

4.1.1. Scalability

The cost analysis in Section 5.2 (Table 2) empirically validates our complexity model. The total on-chain cost is dominated by a linear, one-time bootstrap cost proportional to the number of participants I, S, and N, rather than the project’s duration T or the total number of logical channels. This confirms that our design, which circumvents the cost of naive on-chain methods, is a scalable solution for large-scale HFL deployment.

Table 2.

On-Chain Gas Cost and Economic Feasibility of the CoFT Protocol.

4.1.2. Cost-Efficiency

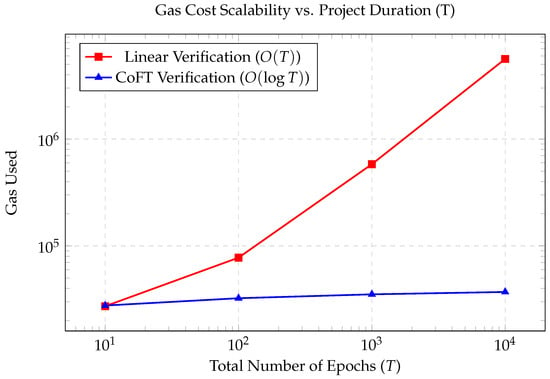

A central design goal was to minimize on-chain costs, which we achieve by deferring all high-frequency T-dependent operations (reward updates) to off-chain state channels. The only T-dependent on-chain cost is the final claimReward function. We hypothesized this cost would be logarithmic (). This claim is definitively proven in our performance analysis in Section 5.3. As shown in Figure 3, while a naive approach sees gas costs explode by over 200 times, the CoFT verification cost remains nearly constant, increasing by only 1.34 times. This logarithmic scalability ensures that the framework remains economically viable even for projects with tens of thousands of epochs, unlike the prohibitively expensive alternative.

Figure 3.

Empirical gas cost of reward verification as T increases.

4.2. Security, Fairness, and Trustlessness

4.2.1. Cryptographic Verifiability and Integrity

The core security guarantee of CoFT is the end-to-end integrity of off-chain reward data. The integrity of an entire project, regardless of its duration T, is compressed into a single 32-byte hash, the . As empirically shown in Table 2, the on-chain cost of anchoring this root is 47,657 gas (), which is constant and independent of T. Any attempt by a Sub-Institution to tamper with a contributor’s reward would result in a different leaf hash, leading to a that does not match the one anchored on-chain. A contributor can then cryptographically prove their final reward by submitting a Merkle proof that links their final state to the immutable on-chain .

4.2.2. Executable Fairness and Trustless Payouts

CoFT is designed to achieve executable fairness by removing the need for contributors to trust their parent sub-institutions for payment. never takes custody of the funds. The contract transfers funds directly to the Payout Contract . A contributor can then permissionlessly execute the claimReward function. Payment is not dependent on approval from but is automatically enforced by the smart contract upon successful proof verification. The claimReward function (Table 3) is shown to be highly efficient (), making the cost of claiming a reward low and predictable and ensuring the mechanism is practically executable.

Table 3.

Verification Cost vs. Project Duration (T).

4.3. Practical Feasibility and Adaptability

4.3.1. Incentive Agnosticism

The CoFT framework is incentive-agnostic. It is designed to handle the payment delivery and verification of a reward, not the calculation of that reward. This is a deliberate design choice for flexibility. For example, a project could implement a simple policy where . Alternatively, a complex policy could use Shapley values to calculate . In both cases, the CoFT framework functions identically: it securely updates the off-chain channel state with the final value and enables its trustless on-chain claim.

4.3.2. Off-Chain Practicality and Robustness

Beyond incentive flexibility, CoFT’s hybrid design must be both computationally practical and robust to parameter changes.

First, the off-chain computation required to generate Merkle proofs could be a potential bottleneck. However, our analysis in Section 5.3 (Table 3) shows this is not the case. On our test machine, generating a proof for a project with 10,000 epochs took only ms, demonstrating that the off-chain overhead is highly practical for real-world application.

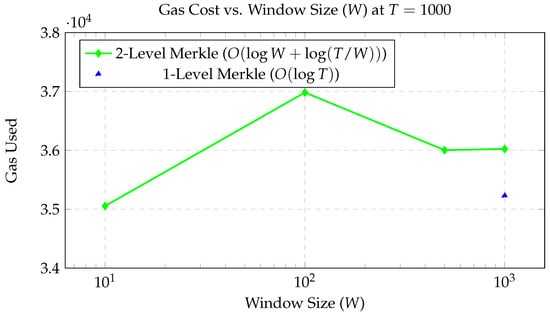

Second, our multi-layered Merkle Tree scheme introduces a parameter, W (Window Size). Our analysis in Section 5.4 (Figure 4) shows that the on-chain verification cost is remarkably insensitive to the choice of W, remaining stable between 35,000 and 37,000 gas. This demonstrates that our framework is robust and does not require complex parameter-tuning to achieve optimal performance.

Figure 4.

Gas cost of 2-Level Merkle verification.

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

To validate the performance of our proposed CoFT framework, we conducted a series of experiments divided into on-chain simulations and off-chain computations.

The on-chain execution costs, measured in gas used, were evaluated on a local, EVM-compatible test network. As the computational complexity within the EVM is deterministic, these gas used measurements are independent of the host machine’s hardware specifications. This ensures that our gas cost analysis is reproducible and reflects the true computational load of the smart contracts. Our on-chain simulation environment was configured as follows:

- Blockchain Simulator: Ganache v2.7.1

- EVM Version: london

- Smart Contract Compiler: Solidity v0.8.20

- Development Environment: Remix IDE v1.1.3

- Wallet Provider: MetaMask v13.8.0

Off-chain computations, such as the generation of Merkle trees and their corresponding proofs, were executed as Node.js scripts. The performance of these tasks is dependent on the host machine’s hardware. The environment used for these measurements was:

- CPU: 13th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-13500 (2.50 GHz)

- RAM: 16 GB

To analyze the economic feasibility of our framework and translate gas used into tangible costs, we assume a stable, average state of the Ethereum mainnet for our USD conversions:

- Gas Price: 20 Gwei

- ETH Price: $3000

5.2. On-Chain Cost

We executed the entire on-chain protocol flow, from initial deployment to final reward claim, to empirically validate our complexity claim and measure the bootstrap costs of the system. Table 2 presents the measured gas used and corresponding USD cost for each core function call.

5.2.1. Economic Feasibility

Our analysis demonstrates the economic trade-offs of the CoFT protocol. The one-time setup cost for the core contracts is significant, approximately 3.1 million gas ($187.06). However, the crucial operational costs for participants are fixed and relatively low. For instance, an institution depositing $1M worth of stablecoin via depositFunds incurs a cost of only 82,301 gas ($4.94). A contributor claiming their final reward incurs a cost of 88,373 gas ($5.30). While these are not sub-cent costs, they are constant and predictable. The $5.30 cost for a contributor to claim their reward remains the same regardless of the project’s duration T or the reward amount.

5.2.2. Complexity

Table 2 is structured to clearly separate costs based on our proposed complexity model. The cost to onboard one institution I is approximately 129,288 gas ($7.76), and the cost to onboard one sub-institution S is approximately 1.41 million gas ($84.77), with the majority being the one-time deployment cost for their PayoutContract. The cost for one contributor N to claim their reward is fixed at 88,373 gas (assuming constant T). This empirically validates that the total on-chain cost scales linearly with the number of participants (I, S, and N).

A core component of this model is its independence from the project duration T. The anchorFinalState function, which anchors the final Merkle root of all T epochs, costs only 47,657 gas ($2.86). This cost is constant () whether or T = 10,000, as it only involves anchoring a single 32-byte hash. This stands in stark contrast to naive on-chain approaches and is the key to our framework’s scalability over time.

5.2.3. EVM Storage Costs

The data also reveals a nuanced understanding of EVM gas costs, particularly the decreasing cost of the mint function (72,001 →54,877 → 37,801 gas). This variance is not random but is a direct and expected result of the EVM’s gas model (EIP-2200).

The EVM differentiates between initializing a storage slot and updating one. Initializing a storage slot from 0 to a non-zero value costs a substantial 22,100 gas. In contrast, updating an already non-zero slot costs only 5000 gas.

Our mint function modifies two storage slots: TS and the recipient’s balances mapping.

- 1st Mint (72k gas): Initializes two slots from 0 to non-zero (TS and the recipient’s balances).

- 2nd Mint (55k gas): Updates one existing non-zero slot (TS) and initializes one new 0 slot (the new recipient’s balances).

- 3rd Mint (38k gas): Updates two existing non-zero slots. It represents the stable-state cost for subsequent mints to the same users.

This analysis confirms that the steady-state mint cost is 37,801 gas ($2.27) and demonstrates the precision of our measurement methodology.

5.3. Verification Cost

A core hypothesis of this paper is that the on-chain verification cost of our framework scales logarithmically with the project duration T (i.e., ), in contrast to naive approaches that scale linearly (). To validate this claim empirically, we measured the gas cost of our Merkle-based claimReward function against a simulated contract , which performs an verification loop.

We executed the off-chain script and on-chain contracts by varying T from 10 to 10,000. The results, including off-chain proof generation time and on-chain gas consumption, are presented in Table 3 and visualized in Figure 3.

As T increases 1000-fold (from 10 to 10,000), the gas cost for the linear approach explodes by over 206 times (from 27,269 to 5,621,681 gas). At our assumed 20 Gwei gas price, a single reward claim in the model at 10,000 would cost $337.30 (5.6 M gas × 0.00006). This cost would be incurred by every single contributor (N), rendering the system prohibitively expensive.

In stark contrast, the gas cost for our CoFT approach remains almost flat, increasing by only 1.34 times (from 27,674 to 37,070 gas) over the same 1000-fold increase in T. This cost translates to approximately $2.22 (37k gas × 0.00006) per claim. This cost is low, predictable, and, crucially, does not scale with the project’s duration T. While not negligible, a fixed $2.22 fee to claim a reward is highly economically viable.

The off-chain computation is also shown to be highly practical. Generating the Merkle proof for a project with 10,000 epochs took only ms on our test machine.

5.4. Anchoring Scheme Parameter Analysis

Our multi-layered Merkle Tree (detailed in Section 3.2.3, Figure 2) introduces a parameter, W (Window Size), which batches T total epochs into blocks. The theoretical verification cost is . This cost is derived from the two proofs required by the claimReward function:

- L1 (Block-Level) Proof: A proof of length that validates the specific epoch’s state (e.g., ) is included in its corresponding Block Root .

- L2 (Global-Level) Proof: A proof of length that validates the Block Root is included in the final, on-chain Global Merkle Root .

To analyze the practical impact of this parameter and find an optimal value, we fixed and measured the total gas cost of this multi-layered verification while varying W. The results are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4.

Table 4.

Verification Cost vs. Window Size (W) at .

As shown in Figure 4, the total gas cost remains remarkably stable between 35,000 and 37,000 gas, regardless of the W value. This is because the total proof length (L1 + L2) remains nearly constant. This proves our scheme is not only efficient but also robust, as it does not require complex parameter tuning. The case where (i.e., , representing a 1-Level tree) costs 36,024 gas, which is almost identical to the simple 1-Level contract’s cost of 35,230, confirming negligible overhead.

5.5. Theoretical Channel Scalability

Beyond the efficiency of state updates, our framework’s primary advantage lies in its scalability with hierarchical complexity (I, S, and N dependence). If each logical channel () required a dedicated on-chain contract deployment, the initial setup cost would render any non-trivial HFL project infeasible.

We model the number of required off-chain channels as a function of the system’s hierarchical parameters in Table 5. The data in Table 5 illustrates the rapid scaling in the number of required logical channels. In the Large Ecosystem scenario, over a quarter of a million logical channels are necessary. The cost of deploying a separate smart contract for each of these channels (each costing over 1 M gas, per Table 2) would be astronomically high.

Table 5.

Required Off-Chain Channels vs. Hierarchical Complexity.

Our framework, by using an deployment model (one Payout Contract per S), circumvents this cost explosion. This highlights the critical importance of our off-chain state channel design for building economically viable HFL compensation systems.

6. Limitations and Future Work

While our empirical results validate the core efficiency claims of CoFT, we acknowledge several limitations and areas for future research.

6.1. Administrator Centralization

The current implementation relies on a centralized Admin to perform critical functions like mint, anchorFinalState, and activateSettlement. This introduces a single point of failure and a trust assumption. We note that the impact of this trust is partially mitigated by the inherent transparency of the blockchain. All critical administrative actions are executed as public on-chain transactions that emit corresponding events. This design ensures that all administrative actions are fully auditable by all participants, allowing for after-the-fact detection of malicious behavior.

However, this audibility provides detectability rather than prevention; it does not resolve the liveness or censorship risk if the Admin refuses to act. Therefore, future work should focus on fully decentralizing this control, for example by transferring ownership to a Decentralized Autonomous Organization governed by the participating institutions or a multi-signature wallet. This approach aligns with ongoing research in on-chain governance and would fully distribute trust among the consortium members.

6.2. Liveness and Dispute Resolution

This paper primarily models the happy path, assuming all participants are honest and responsive. We do not explicitly define a protocol for handling disputes (e.g., disagreement on ) or non-responsive participants (e.g., institutions refuses to sign a state update). A production-ready system would require a robust state-channel dispute mechanism, as formalized in foundational works like the Lightning Network [] and virtual channels. This represents a significant and necessary area for future research, including the implementation of on-chain challenge periods(contestation windows) and timeout functions to allow participants to unilaterally exit the channel with their last co-signed state.

6.3. Privacy Considerations

The current design, while efficient, has privacy limitations. A contributor’s claimReward transaction is public. Although the reward value is part of the hashed leaf and not directly visible, the transaction’s existence on-chain, combined with the Merkle proof, could leak metadata about which contributor participated and when. Future iterations could explore using zero-knowledge proofs to allow a contributor to prove their right to a specific reward amount without revealing the leaf, epoch, or their identity, thereby preserving on-chain privacy.

6.4. Economic and Regulatory Risks

Our framework relies on a fiat-collateralized stablecoin for economic stability. This introduces exogenous risks, such as the volatility or de-pegging of the stablecoin itself, as well as the regulatory risks associated with issuing and transacting digital assets, especially in sensitive domains like healthcare. A comprehensive real-world deployment would need to address these economic and legal challenges, which are outside the scope of this technical paper.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed CoFT, a novel compensation framework designed to overcome the scalability and transparency challenges inherent in Hierarchical Federated Learning. By integrating a stablecoin with a hybrid architecture of on-chain fund management and an off-chain hierarchy of state channels, our framework achieves exceptional cost-efficiency. We demonstrated a reduction in on-chain complexity from a prohibitive to a sustainable , making large-scale projects economically viable. Furthermore, the framework guarantees cryptographic verifiability through a final Merkle anchor, enabling automated, trustless payouts and fair, flexible burden-sharing among participants.

While this work establishes a robust foundation, future research could explore further decentralization of its administrative components and the integration of advanced privacy-preserving techniques. Ultimately, CoFT provides a scalable and secure blueprint for the financial infrastructure required to foster large-scale, collaborative AI, paving the way for more impactful real-world applications.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: S.N., K.-H.R. and S.U.S.; data collection: S.N.; analysis and interpretation of results: S.N., K.-H.R. and S.U.S.; draft manuscript preparation: S.N., K.-H.R. and S.U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported as a ’Technology Commercialization Collaboration Platform Construction’ project of the INNOPOLIS FOUNDATION (Project Number: 1711202494). It was also partially supported by the IITP (Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation)-ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (IITP-2025-RS-2020-II201797).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Gemini, 2.5 Flash for the purposes of enhancing the clarity and stylistic quality of the English text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rani, S.; Kataria, A.; Kumar, S.; Tiwari, P. Federated learning for secure IoMT-applications in smart healthcare systems: A comprehensive review. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 274, 110658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.K.; Boverlinetacharya, P.; Maru, D.; Tanwar, S.; Verma, A.; Singh, A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Sharma, R.; Alkhayyat, A.; Țurcanu, F.-E.; et al. Federated learning for the internet-of-medical-things: A survey. Mathematics 2022, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelekoudas-Oikonomou, F.; Zachos, G.; Papaioannou, M.; de Ree, M.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Mantas, G.; Rodriguez, J. Blockchain-Based Security Mechanisms for IoMT Edge Networks in IoMT-Based Healthcare Monitoring Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniyi, E.A.; Ogundokun, R.O.; Awotunde, J.B. IoMT-based wearable body sensors network healthcare monitoring system. In IoT in Healthcare and Ambient Assisted Living; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Arthi, K.; Chidhambararajan, B. Advanced Enabling Technologies of IoMT in Personalized Healthcare. In Technological Advancement in Internet of Medical Things and Blockchain for Personalized Healthcare; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, I.; Campo-Valera, M.; Rodríguez, J.V.; Woo, W.L. IoMT innovations in diabetes management: Predictive models using wearable data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research, Internet of Medical Things Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Component (Hardware, Software), By Deployment (On-Premise, Cloud), By Application, By End Use, By Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2025–2030. Report ID: GVR-4-68040-109-0. 2024. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/internet-of-medical-things-iomt-market-report (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Wani, R.U.Z.; Thabit, F.; Can, O. Security and privacy challenges, issues, and enhancing techniques for Internet of Medical Things: A systematic review. Secur. Priv. 2024, 7, e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/119933/download (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Rana, O.; Spyridopoulos, T.; Hudson, N.; Baughman, M.; Chard, K.; Foster, I.; Khan, A. Hierarchical and decentralised federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 Cloud Continuum, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 5 December 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Tang, X.; Yang, C.; Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, Q.; Li, Z.; Yu, H. HiFi-Gas: Hierarchical Federated Learning Incentive Mechanism Enhanced Gas Usage Estimation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 22824–22832. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, C.; Wang, X.; Yu, F.R.; Leung, V.C. An incentive mechanism for big data trading in end-edge-cloud hierarchical federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Madrid, Spain, 7–11 December 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Chai, S. BTIMFL: A Blockchain-Based Trust Incentive Mechanism in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; pp. 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmadika, S.; Firdaus, M.; Jang, S.; Rhee, K.H. Blockchain-enabled 5G edge networks and beyond: An intelligent cross-silo federated learning approach. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 5550153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Pan, R. Auction-based ex-post-payment incentive mechanism design for horizontal federated learning with reputation and contribution measurement. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.02410. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Pan, R. Online auction-based incentive mechanism design for horizontal federated learning with budget constraint. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.09047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, M.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Leung, C.; Miao, C. A contract theory based incentive mechanism for federated learning. In Federated and Transfer Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerlands, 2022; pp. 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- He, G.; Li, C.; Song, M.; Shu, Y.; Lu, C.; Luo, Y. A hierarchical federated learning incentive mechanism in UAV-assisted edge computing environment. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 149, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ji, Y.; Kou, Z.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, S. Asynchronous federated learning with incentive mechanism based on contract theory. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference(WCNC), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 21–24 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.; Li, J.; Wei, K.; Qian, Y.; Wang, K.; Shu, F.; Chen, W. Design of two-level incentive mechanisms for hierarchical federated learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zeng, R.; Yang, M.; Li, K.; Huang, M.; Dustdar, S. VARF: An incentive mechanism of cross-silo federated learning in MEC. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 15115–15132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Cheng, R.; Li, C.; Chen, M.; Zhu, J.; Long, Y. Federated learning and reputation-based node selection scheme for internet of vehicles. Electronics 2025, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, C.; Jin, L.; Su, C. A Trust-Aware Incentive Mechanism for Federated Learning with Heterogeneous Clients in Edge Computing. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Du, C. A dynamic incentive and reputation mechanism for energy-efficient federated learning in 6g. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2023, 9, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, C.; Liu, Z.; Nie, J.; Leung, V.C. Infedge: A blockchain-based incentive mechanism in hierarchical federated learning for end-edge-cloud communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 3325–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Seneviratne, O. Blockchain-based Framework for Scalable and Incentivized Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 1761–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Wong, V.W. An incentive mechanism for cross-silo federated learning: A public goods perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 May 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Burchert, C.; Decker, C.; Wattenhofer, R. Scalable funding of bitcoin micropayment channel networks. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziembowski, S.; Eckey, L.; Faust, S.; Hesse, J.; Hostáková, K. Multi-party virtual state channels. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2019: 38th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Darmstadt, Germany, 19–23 May 2019; pp. 625–656. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, J.; Dryja, T. The Bitcoin Lightning Network: Scalable Off-Chain Instant Payments. 2016. Available online: https://lightning.network/lightning-network-paper.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).