Abstract

This work examines the robotic technique of ungrasping, in which an object held by a gripper is intentionally released into the environment. The proposed method achieves controlled object release through non-static contact interactions that permit rolling and sliding. This form of dexterous manipulation is especially important for thin or slender objects, as demonstrated through physical experiments. This study first addresses how three-dimensional stability can be established using a minimal number of contacts. It then introduces a planning framework for three-dimensional ungrasping that extends our prior planar formulation. Experimental results obtained with a two-fingered gripper—the most common gripper type—validate the feasibility, effectiveness, and practicality of the presented approach.

1. Introduction

The task of robotic ungrasping—the inverse of grasping—concerns releasing an object from the gripper’s hold. In other words, a robot passes an object to its environment through ungrasping. This technique is exemplified in placement, insertion, and assembly tasks. As a fundamental manipulation capability, grasping has long been recognized as a challenging problem; likewise, ungrasping can be equally difficult and equally essential.

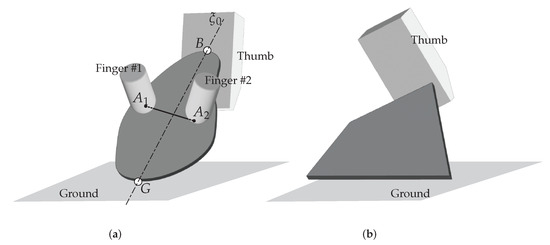

In some ungrasping scenarios—such as simply throwing or dropping an object—the robot can release its grip without requiring intricate manipulation. In contrast, dexterous contact interactions involving rolling or sliding enable robots to handle more complex cases, termed dexterous ungrasping [1,2]. For example, as shown in Figure 1, a pinch grasp may need to be reconfigured to expose the portion of the object initially obscured by the robot’s fingers, thereby allowing contact with an external target surface. This challenge is particularly significant for thin or slender objects, which resemble many human-made artifacts, as illustrated in Figure 1. Although such tasks appear effortless for humans—owing to our multi-fingered hands and refined dexterity—they remain substantially challenging for robots. Consequently, robots rarely replace humans in dexterous manipulation tasks; for instance, even AlphaGo required human assistance to place the Go stones.

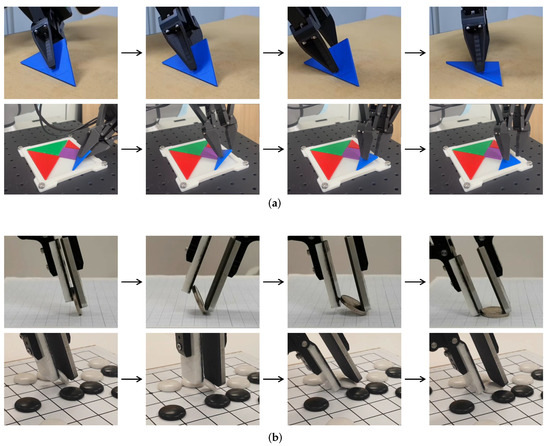

This study (note that this article is a revised and expanded version of [3], which was presented at the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, USA, May 2025) presents a manipulation technique for three-dimensional ungrasping through spatial dexterous manipulation (Figure 1a). A key challenge in such tasks lies in maintaining three-dimensional stability—that is, ensuring that the object remains securely held throughout the dexterous interactions. To address this challenge, a stability framework is introduced that integrates both active and reactive mechanisms with considerations for robustness. In addition, corresponding planning and control strategies are developed for three-dimensional ungrasping. The broader practical significance of this approach lies in its applicability to a wider range of ungrasping scenarios, than prior works on planar ungrasping [1,2], while maintaining implementation simplicity using a standard two-fingered, motion-controlled arm–gripper system.

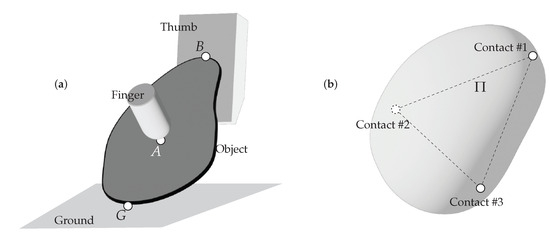

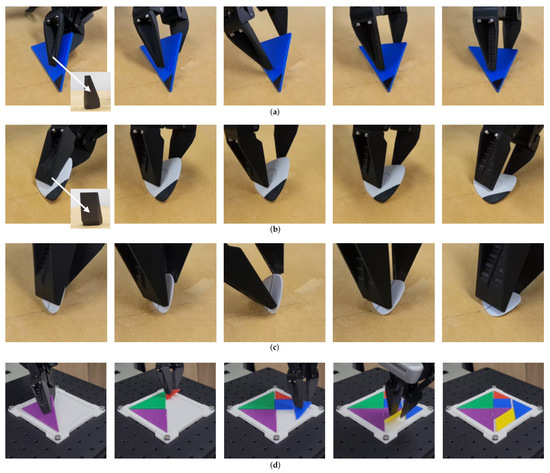

Figure 1.

(a) Three-dimensional dexterous ungrasping: placing a puzzle piece (top) and its application to puzzle tiling (bottom). (b) Planar dexterous ungrasping from our previous work [1,2], where the robot exploits geometric symmetry, in contrast to (a). Reprinted with permission from [3].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature, and Section 3 introduces the preliminaries and problem formulation. Section 4 investigates stability in three-dimensional ungrasping, while Section 5 presents the associated planning and control strategies. Experimental results are provided in Section 6. The main advancements beyond the prior conference version [3] include a revised discussion of the reactive mechanism for rotational stability (Section 4.2), its corresponding simulation scheme (Section 4.3), a new discussion on practical robustness (Section 4.4), and an updated treatment of planning (Section 5).

2. Related Work

A substantial body of research has explored fundamental robotic ungrasping or releasing tasks, which involve transferring objects from a robot’s grasp to the environment. Such capabilities are of considerable practical relevance and appear in diverse contexts, encompassing both quasistatic scenarios—such as contact-rich assembly [4,5] and bin packing [6]—and dynamic ones, including object tossing [7]. Within this broader context, dexterous ungrasping—the deliberate release of objects through coordinated dexterous manipulation, which constitutes the focus of this study—has received relatively limited attention in the literature.

Our object-releasing method can be viewed as a form of robotic in-hand manipulation, which concerns adjusting an object’s position or orientation within the robot’s grasp. This topic has been widely investigated as part of the broader pursuit of autonomous robotic manipulation. Representative examples include finger gaiting, sliding, rolling, and regrasping [8,9,10,11,12], typically demonstrated using multi-fingered hands. More recently, however, researchers have explored in-hand manipulation with simpler grippers that leverage interactions with the environment. For instance, a body of studies [13,14] have proposed methods that exploit external forces and environmental constraints, and this trend has been further advanced through the integration of learning-based approaches [15,16]. The embodiment adopted in this work follows the same principle.

The manipulation strategy introduced in this work targets low-profile (i.e., thin) objects, which have been widely studied owing to their practical significance in real-world applications. Prior research has explored various approaches to handling such objects. For instance, the study in [17] demonstrated an open-loop picking method using an underactuated hand, successfully manipulating diverse thin items. In [18], object acquisition is achieved by exploiting the compliant deformation of the soft fingertips of a multi-fingered gripper. Meanwhile, ref. [19] proposed a specialized gripper design and manipulation scheme optimized for scooping thin objects lying on flat surfaces.

3. Preliminaries and Problem Description

This section first summarizes our recent work on planar dexterous ungrasping and then formulates the central research question of the present study, namely, its extension to three-dimensional ungrasping, building upon that preliminary investigation.

3.1. Preliminaries

Our recent studies [1,2] address the problem of planar dexterous ungrasping, namely, the capability to release a grasped object from a gripper and securely place it onto a target surface through rolling and sliding manipulation (Figure 1b). This process is formulated as a planar motion planning and control problem, with the task space represented by . As illustrated in Figure 2 (details provided below), the setup consists of a linear object model manipulated by a two-fingered gripper within a plane, i.e., the -plane, which is oriented normal to the flat ground serving as the target surface.

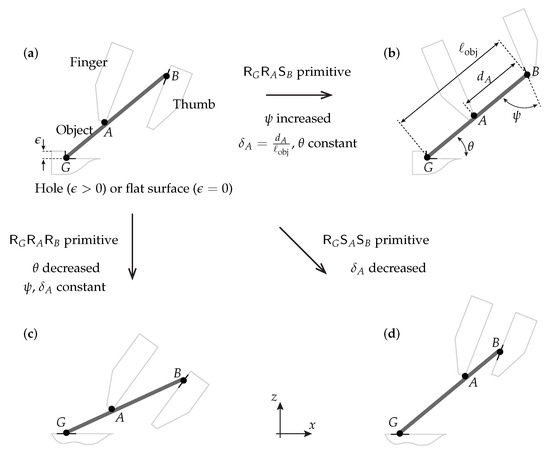

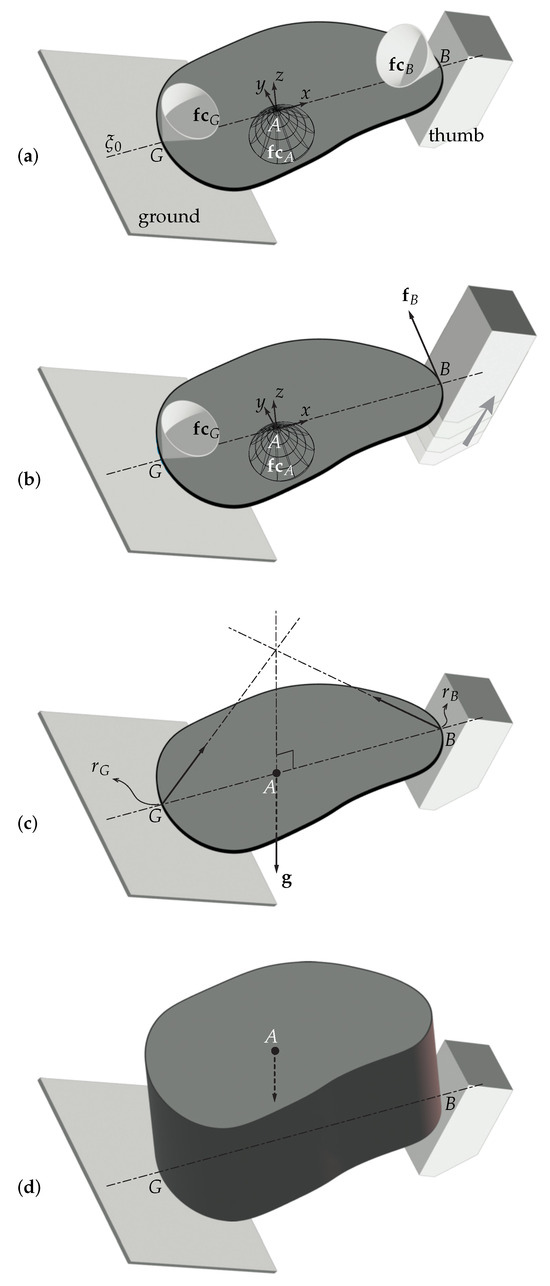

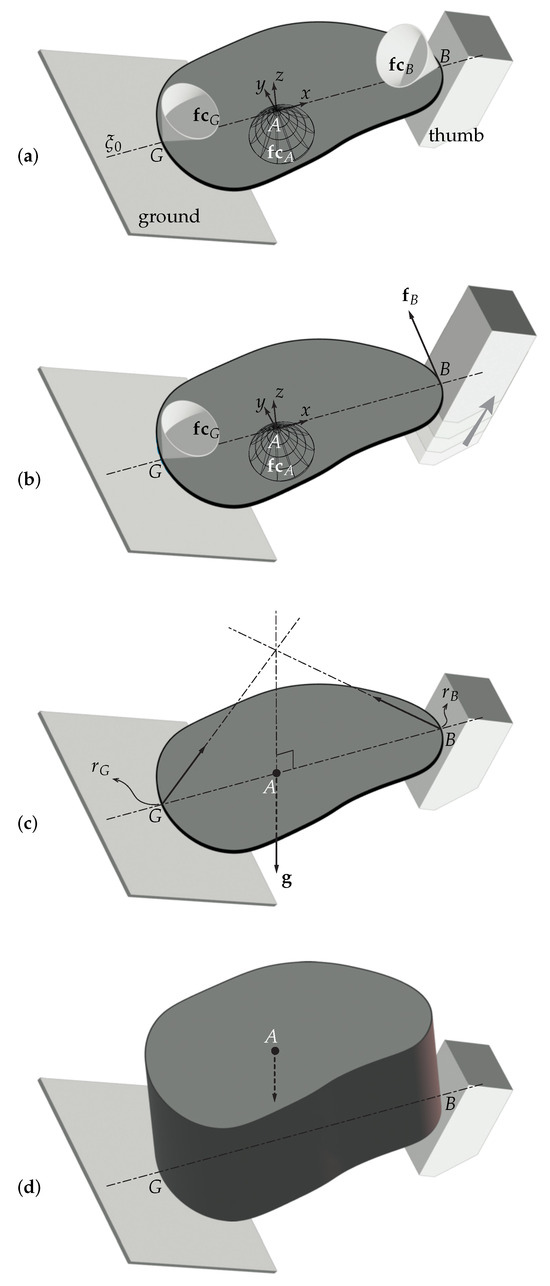

Figure 2.

Motion primitives for planar dexterous ungrasping: (a,b) , (a–c) , and (a–d) . The relative configurations among the contacting bodies evolve through sliding or rolling at contacts G, A, and B.

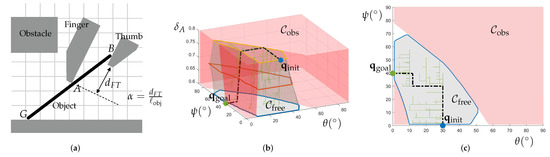

Algorithm 1 [1] presents our motion planning algorithm for planar dexterous ungrasping. Building on a variant of the rapidly-exploring random tree (RRT) algorithm, specifically, RRT* [20] which converges to an optimal solution, Algorithm 1 produces an optimal (based on a suitable criterion) path from an initial configuration , where the object is in a pinch grasp, to a final configuration , where the object is positioned on a target surface. A returned motion path is represented as a sequence of motion primitives—elementary units of movement parameterized by contact type and location, thereby standardizing the contact interactions among the bodies involved: the object, the robot’s digits, and the target surface. As shown in Figure 2, which illustrates instances of these motion primitives, these bodies interact through three rigid, unilateral, frictional point contacts G (on the target surface), A (on the finger), and B (on the thumb). Each motion primitive is thus defined based on the specification of the contact mode at G, A, and B, which can be sliding or rolling/fixed. For example, in the primitive (Figure 2a,b), G and A are rolling (denoted by ) and B is sliding (denoted by ): the contact locations of G and A remain fixed, whereas the contact point B moves along the thumb. Algorithm 1 expands the search tree by iteratively adding a new node when it is reachable using these motion primitives, and force-closure—i.e., the composite wrench cone spans the entire wrench space [21]—is attainable along the way to securely keep hold of the object. Because force-closure is required, the friction coefficients at G, A, and B—denoted , , and , respectively—are critical parameters in the algorithm. An example of a computed motion plan is shown in Figure 3. Note, the primitives shown in Figure 2a,b, a–c and a–d, respectively were designed for traversing along the -, -, and -directions, respectively, within the three-dimensional configuration space depicted in Figure 3b.

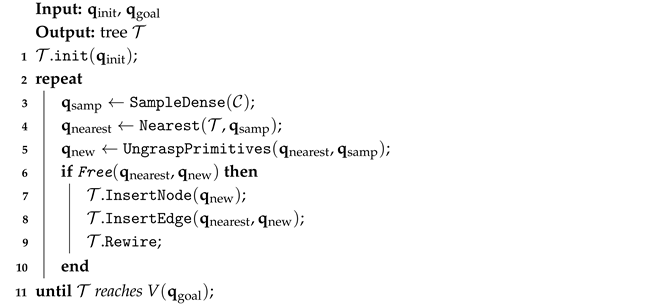

| Algorithm 1: Dexterous Ungrasping Planner [1]. |

|

Figure 3.

Example of motion planning. (a) Planning scene showing the collision hulls of the bodies that may intersect. (b) Planned path within the free space —the gray volume excluding the obstacle space shown in red—of the three-dimensional configuration space, -space (refer to Figure 2 for the notation). The path connects , where in the initial pinch grasp, to , where the objects rests on the ground with . The edges of the search tree are marked in green. (c) Projection of the planned path onto the -plane.

An ungrasp planned by Algorithm 1 can be executed through open-loop motion control without the need for feedback. Despite the underactuation resulting from the unilateral contact interactions at G, A, and B, our previous work in [2] demonstrates that the coordination of the object-robot system can be carried out robustly, accommodating errors, uncertainties, and even the loss of contact. This robustness is achieved by leveraging the fact that the object is enclosed within an energy-bounded cage [22], formed of the surroundings, which include the robot and the target surface. Essentially, this means that unless a sufficient amount of energy is imparted, the object being ungrasped (for example, the Go stone in Figure 1b) will not escape from the gripper. The nondimensional parameter (Figure 3a)—defined as the finger-thumb length difference divided by the object’s length and thus quantifying digit asymmetry—plays a critical role in ungrasping (full details in [1]). With fingers of equal length, i.e., , Algorithm 1 might not be able to discover a secure, force-closure path. Feasible values for can be determined by running multiple planning queries.

3.2. Problem Description

The research question in this work is to generalize planar dexterous ungrasping, introduced in Section 3.1, to its three-dimensional counterpart. While planar ungrasping has been demonstrated with three-dimensional objects such as Go stones (Figure 1), stability outside the plane of manipulation—the -plane in Figure 2—cannot be guaranteed. As a result, the planar technique may not suffice in more general scenarios, particularly when symmetry about the plane of manipulation cannot be exploited. This motivates our investigation of full three-dimensional stability in dexterous ungrasping, along with the development of a corresponding planning and control solution.

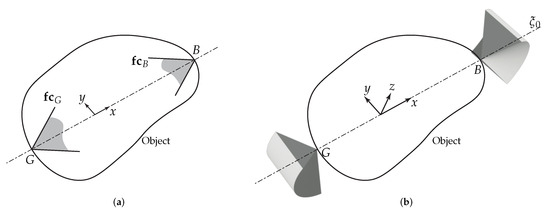

The typical contact configurations of three-dimensional ungrasping scenarios, illustrated in Figure 1a, are abstracted in the schematic of Figure 4a, extending the planar model of Figure 2. In this abstraction, the object is a rigid body with negligible thickness—that is, a low-profile geometry—manipulated by a finger–thumb gripper model in which the fingertip can move freely relative to the thumb’s face. The gripper is assumed to be equipped on a holonomic arm, granting full flexibility in configuring its pose. Contact interactions occur at three rigid, frictional, unilateral contact points—G, A, and B. Generalizing from the planar case, both the object’s configuration space and the associated contact wrenches are now six-dimensional. These assumptions are conservative; in particular, higher-profile objects exhibit more favorable force properties (to be discussed in Section 4.1), and additional forces can be transmitted through nonpoint contacts.

Figure 4.

(a) Grasp with three collinear contacts on a low-profile object with a smooth boundary, considered in three-dimensional ungrasping tasks. Contact A lies on the object’s face, while contacts G and B are located on its boundary. (b) Grasp with three point contacts on a spatial body, with contact #2 situated on the opposite side of the body. The plane defined by the three contact points is denoted by . Reprinted with permission from [3].

4. Stability in Three-Dimensional Ungrasping with Degenerate Contact Wrenches

This section examines how an object can be stably ungrasped in three dimensions using less capable contacts—specifically, three collinear contacts that are prone to sliding. A simulation framework for verifying stability is also presented, along with a discussion of the practical robustness of the resulting stability. The term stability is used here to denote more than mere static equilibrium—specifically, a condition approaching force-closure, which is known to imply the possibility of dynamic stability [23].

4.1. Off-Plane Stability: y-Forces and z-Moments

Under what conditions does a three-point-contact grasp attain stability on a general three-dimensional body (Figure 4b)? A well-established necessary condition for equilibrium of three zero-pitch wrenches—that is, the forces applied at the three contact points—is that their lines of action lie within a common plane and intersect at a single point. In other words, the three forces must form a flat pencil. On this basis, force-closure can be ensured provided the following assumption holds [24]:

Assumption 1.

The three contact points on the spatial body are not collinear. Each associated friction cone intersects the plane defined by the three contacts, denoted as Π in Figure 4b, such that the intersection yields a proper planar cone. Moreover, the cross section of the body with respect to plane Π achieves planar force-closure with the cross sections of the friction cones in Π.

However, the classical result does not directly extend to the present case of three-dimensional ungrasping illustrated in Figure 4a, despite also involving three point contacts on a spatial body. Two fundamental distinctions arise. First, in Figure 4a the three contacts G, A, and B must lie on a common line in order to maintain force equilibrium for an object of idealized zero thickness. This requirement stands in contradiction to the non-collinearity condition specified in Assumption 1. Second, the friction cones at the contacts may degenerate into directed lines under sliding, shown to be necessary in dexterous ungrasping (for example, recall the sliding at B in Figure 2a,b). This contrasts with the assumption of static, non-sliding contacts in the classical formulation.

What, then, are the force and moment characteristics of contacts G, A, and B when they are collinear and potentially sliding? In other words, which six-dimensional wrenches can the contact configuration in three-dimensional ungrasping generate? To address this question, the following assumption is introduced, inspired by Assumption 1 but adapted to the three-dimensional ungrasping scenario:

Assumption 2.

At each contact G, A, and B (Figure 5a), the friction cone intersects the -plane—the plane containing the line and normal to the object’s surface—such that the intersection forms a proper planar cone.

Figure 5.

(a) Alternative perspective of Figure 4a (finger omitted for clarity). The contact surfaces at G and B are flat and sufficiently large. The friction cones are denoted by , with expanding below the object. The -frame is defined with origin at A, the -plane coincident with the object’s plane, and the x-axis collinear with —the axis connecting G and B. (b) Sliding at B (thumb moving upward) in primitive. B can exert only a single wrench along the boundary of its friction cone, restricted to the -plane. (c) The object is supported by normal forces at G and B against gravity acting normal to the object’s plane at A. and denote the radius of curvature of the object’s boundary at G and B. (d) A tall object might be destabilized by the contact force at A on its top face. Reprinted in part with permission from [3].

Under Assumption 2, our first step is to examine how wrenches can be applied off the -plane, specifically the y-forces and x- and z-moments. This analysis allows the three-dimensional stability problem to be reduced, in part, to planar stability within the -plane, as discussed in our prior work [1,2]. Consider the following formulation, which asks whether the off--plane components—y-forces and x- and z-moments—of an external wrench, , can be balanced by the off--plane components—that is, the y-components—of the contact wrenches at G, A, and B:

Here (see Figure 5a), , , and are the unit vectors of the -frame; denotes a contact wrench at contact X, belonging to the corresponding friction cone ; and is the position vector to X. Equations (1) and (2) comprise three linear equations in three scalar unknowns: the y-components of the contact wrenches, , , and , which can assume arbitrary values under Assumption 2 because the intersections of the friction cones with the -plane are proper. In Equation (2), however, the moment vectors on the left-hand side are all aligned along the z-axis, with zero x-components. Consequently, any external y-forces and z-moments can be compensated, but x-torques cannot be generated directly by the contact wrenches, all of which intersect the x-axis.

Before addressing the issue of generating x-torques in the following subsection, it is noted that even when one contact slides within the -plane—for example, Figure 5b illustrates the motion primitive in which contact B slides on the -plane—it remains possible to generate arbitrary y-forces and z-moments without altering the relative motion of the contacts. This is evident from Equations (1) and (2), which still provide two equations in two unknowns, even though the contact wrench at the sliding contact B lies entirely within the -plane and has a zero y-component. However, the equations also indicate that the ability to generate arbitrary z-moments is compromised if two contacts are sliding, and y-forces cannot be produced if all three contacts are sliding.

4.2. Off-Plane Stability: x-Moments

As established in Section 4.1, x-torques cannot be generated directly by the contact wrenches shown in Figure 5a,b. Nevertheless, this limitation can be compensated. In particular, the contact force at A can induce reactive restoring moments in response to rotational perturbations about the x-axis, provided that the curvature of the object boundary at contacts G and B is finite—that is, excluding the degenerate case of infinite curvature corresponding to zero radius of curvature or cusps at G and B. This mechanism is analogous to the self-stabilizing behavior of roly-poly toys. Whereas a roly-poly maintains balance through gravity acting on a single contact, the present configuration achieves a similar stabilizing effect through two support contacts (G and B) and an actively applied contact force at A.

To clarify the mechanism by which restoring x-moments are generated, let us first consider a more conservative scenario in which the contact force at A is replaced by gravity. Specifically, assume that the object’s mass center coincides with A, as illustrated in Figure 5c. The situation is conservative because gravity acts as a single force of fixed direction and magnitude, unlike the contact at A, which permits a range of forces within a friction cone. Under this setup, it can be shown that the object is locally dynamically stable, provided that: (1) the gravitational force is perpendicular to the object’s plane; (2) gravity and the normal forces at contacts G and B are in equilibrium; and (3) the object is constrained to rotate instantaneously about the axis connecting G and B—that is, the object rolls on G and B. A full proof is available in [25]. In summary, the object’s gravitational potential energy is locally minimized at the equilibrium configuration, except in the degenerate case where cusps occur at G and B (i.e., when the radii of curvature of the object boundary at these points, and in Figure 5c, vanish). This energy landscape ensures local dynamical stability. Equivalently, the gravitational moments about always act to counter rotational perturbations around that axis.

The gravity-induced balancing mechanism discussed above extends to the case of a physical contact at A (Figure 5a,b), since the contact wrench cone at A, determined by friction, subsumes the single force of gravity. Because this stabilizing effect arises from the moments of the force at A about , it is unaffected by potential sliding of the contacts on the -plane. The effectiveness of this mechanism, however, depends on the object’s thickness. While it holds for low-profile objects of idealized zero thickness, as illustrated in Figure 5a–c, it may break down for objects with nonzero thickness, particularly tall objects (Figure 5d) with small radii of curvature and . In such cases, the force applied at A from a higher location may fail to produce stabilizing, restorative moments.

4.3. Simulation Scheme

A computational approach for verifying x-rotational stability is practically useful in cases such as Figure 5d, which features objects with nonzero thickness. In such scenarios, the radii of curvature and must be sufficiently large for the forces at A to generate restoring x-moments. However, performing a geometric analysis for every possible configuration is often impractical and excessively complicated. Accordingly, a computational scheme is proposed to verify stability.

Consider a discretized model of objects with nonzero thickness, represented as a rigid polygon approximating the bottom face, with contact point A located off the face. Figure 6a illustrates this model as a rigid polygonal prism. Initially, contacts G and B are positioned at vertices of the bottom face. Suppose the prism begins rotating about the axis connecting G and B; rotation continues until the adjacent vertex or —say in Figure 6b—contacts the surface. The extent of this rotation is uniquely determined by rigid body kinematics. This new contact event shifts the rotation axis to pass through the adjacent vertex, and the process repeats. Throughout this sequence of rotations, the relative configuration between A and the current axis of rotation is tracked to assess whether the contact forces at A can generate restoring moments about the axis. The contact forces at A are represented as linear combinations of unit wrenches spanning a discretized friction cone. By refining the polygonal approximation, the simulation achieves higher accuracy. The current simulation software, implemented in MATLAB R2024b, realizes the scheme through rigid-body rotation and transformation.

Figure 6.

Discretized setup illustrating a polygonal prism. (a) Initial rotation about the axis . (b) After vertex contacts the surface, the rotation axis shifts to .

4.4. Practical Robustness

Recall that the stability principles presented in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 are based on Assumption 2, as illustrated in Figure 5a. Any misalignment of A that violates the assumption can compromise stability, highlighting the importance of ensuring robustness.

One practical solution to robustness is to employ more sophisticated contact geometries beyond point contact discussed so far. For example, an edge contact at A on planar objects provides robustness, as the contact edge can shift, whether intentionally or accidentally, as long as it correctly intersects the nominal (or the x-axis) within its interior. Achieving an edge contact at A can be accomplished using a fingertip with nonzero width or a gripper with more than two fingers, as illustrated in Figure 7a. In addition, considering target objects with polygonal boundaries (as opposed to the smooth-shaped objects discussed thus far) allows for the formation of edge contacts at G and/or B (Figure 7b). It is worth noting the practical significance of this polygonal model, which can be applied to a wide range of human-made artificial objects. Edge contact at G and/or B provides robustness by permitting a finite interval on the edge through which is allowed to pass.

Figure 7.

(a) Edge contact at A along , realized using a three-fingered gripper configuration. (b) Edge contacts formed at the thumb and on the ground with a polygonal object.

Using edge contacts at G, A, or B provides an additional advantage: the resulting contact wrenches can directly generate couples along the x-direction. This capability eliminates the need for the reactive stabilization mechanism described in Section 4.2 to maintain x-rotational stability.

4.5. Full Three-Dimensional Stability

By exploiting off--plane stability through both direct contact wrenches and the reactive mechanism for x-torques, achieving three-dimensional stability in ungrasping—despite challenges arising from collinear and potentially sliding contacts—essentially reduces to ensuring planar stability within the -plane. This observation suggests that planning and control for three-dimensional ungrasping can build upon the planar ungrasping framework introduced in Section 3.1, which ensures the stability within the -plane by means of force-closure. This approach is further explored in the following section.

5. Planning and Control for Three-Dimensional Dexterous Ungrasping

As discussed in Section 4, the challenge of ensuring three-dimensional stability under less capable contacts—that is, collinear contacts that may undergo sliding—can be reduced to the problem of planar stability in the -plane. This observation provides a foundation for extending and adapting our prior work on planar ungrasping to the planning and control of three-dimensional ungrasping.

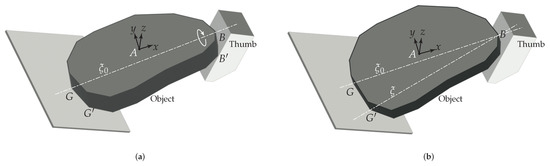

5.1. Setting the -Plane

The first step in extending the planar framework to three-dimensional dexterous ungrasping is to establish the plane of manipulation, namely the -plane. This requires identifying the positions of G and B, which define the x-axis (or ) in Figure 5a. As discussed in Section 4, it is essential that G and B be arranged so as to satisfy Assumption 2 throughout the ungrasping process, even though their associated friction cones may undergo substantial reorientation during the execution of the motion primitives in Figure 2.

Our approach is to position G and B so that they form a planar antipodal grasp [26], thereby ensuring that the two contacts alone provide planar force-closure on the object’s plane. In geometric terms, G and B are positioned such that each lies within the field of view defined by the other’s friction cone (Figure 8a). When this condition holds (see Figure 8b), the -plane—defined as perpendicular to the object’s plane and passing through —is guaranteed to lie within the volume generated by rotating the friction cone of G (and likewise that of B) about the tangent axis to the object boundary at the contact. This construction ensures that Assumption 2 is satisfied regardless of how the friction cones are oriented. The inclusion of the -plane within both volumes of revolution follows directly from the fact that lies inside both friction cones on the object’s plane, which is again geometrically inherent in the antipodal grasp condition.

Figure 8.

(a) The object achieves force-closure through two contacts at G and B. (b) At each contact, the conical shape illustrates, in part, the volume of revolution obtained by rotating the planar friction cone (defined on the -plane) about the axis tangent to the object boundary at that contact.

The computation of planar antipodal grasps is a well-studied problem, with efficient solutions—such as linear programming—available for objects with polygonal boundaries (or polygonal approximations of smoothly contoured objects) [26].

5.2. Planning and Control for Three-Dimensional Ungrasping

By fixing the manipulation plane as the -plane, the problem reduces to a planar ungrasping scenario. Conceptually, this can be understood by ‘slicing’ Figure 5a along the -plane, which produces a configuration similar to Figure 2. Importantly, in Figure 5a, the -plane does not generally bisect the friction cones at G and B unless those points are strictly antipodal (i.e., diametrically opposite)—though antipodal grasps do not necessarily require this condition. As a result, the planar friction cone, obtained by intersecting the 3D cone with the -plane, may have a narrower aperture than the original cone at each contact. This reduction can be interpreted as a decrease in the effective friction coefficients at G and B, denoted and in the planar setting. With these adjusted values, planning proceeds on the -plane using Algorithm 1. As discussed in Section 4.1, employing the two primitives (Figure 2a,b) and (Figure 2a–c) suffices to guarantee full three-dimensional stability, since at most one contact slides. By contrast, (Figure 2a–d) involves two sliding contacts and thus offers only partial stability, losing the ability to generate z-moments in that mode.

Before executing a planned motion, it is assumed the object is already held in a pinch grasp where (Figure 2) with the digits aligned along the -plane. Achieving this alignment may require reorienting the object within the grasp—a problem that has been studied for essentially planar objects pinched at their faces [27,28]. Such preparatory actions ensure proper alignment before ungrasping begins. During execution, however, unlike in the purely planar case, the rolling axes at G (for the object) and at B (for the thumb) are generally non-parallel, which necessitates full three-dimensional motion control.

6. Experiments

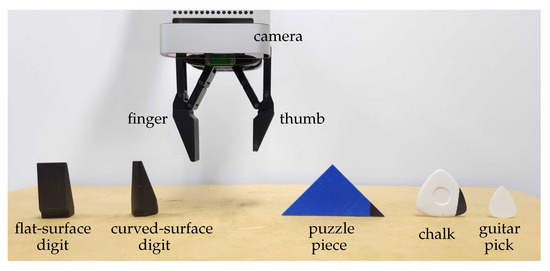

This section presents the implementation of the three-dimensional dexterous ungrasping framework and reports the results of a series of experiments.

6.1. Implementation

Figure 9 shows our overall hardware setup, which consists of an off-the-shelf arm (UR5e; Universal Robots, Odense, Denmark), a gripper (RH-P12-RN Gripper; Robotis, Seongnam, Republic of Korea), and a camera (Azure Kinect; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The intentional digit asymmetry measured by (Figure 3)—critical for our dexterous ungrasping technique—required tailoring the two-fingered gripper, specifically shortening the thumb relative to the finger as shown in Figure 9, corresponding to different values. The camera is used to process experimental results.

Figure 9.

Overall hardware setup with test objects. The two-fingered gripper features an asymmetric arrangement, with the finger longer than the thumb.

Software has been developed as a package for the Robot Operating System (ROS) to manage the robot system and execute planned motions. The underlying drivers for the arm (urx Python library) and the gripper (Dynamixel SDK, Robotis, Seongnam, Republic of Korea) have been customized to enable smoother motion control. The motion primitives shown in Figure 2 are realized through holistic control of the arm–gripper system. For example, in the primitive, the reorientation of the gripper (by the arm) is coordinated with the opening of its fingers while maintaining one fingertip fixed at contact point A. This process is nontrivial because both digits move simultaneously along curvilinear paths relative to the base while the gripper opens and closes. By resolving this, smooth motion is achieved as required. An OpenCV-based tool is also incorporated to measure positioning errors of test objects.

6.2. Experiments: Robust Precision Placement

The performance of object placement through three-dimensional dexterous ungrasping was evaluated, focusing on the secure and precise positioning of items onto a flat tabletop from an initial pinch grasp. Tests were performed with a triangular puzzle piece (durable), fabric chalk (brittle), and a guitar pick (slippery and moderately flexible), as shown in Figure 9. While these objects share similar overall shapes, this does not restrict the applicability of the method. Regardless of the geometric complexity of polygonal object models, the manipulation plane (the -plane) is consistently configured to intersect just two edges, permitting antipodal grasps (Section 5.1). The experimental scenarios are described below.

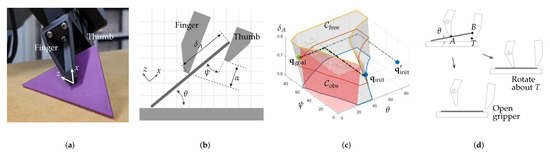

6.2.1. Base Scenario: Precision Placement

The digits with curved contact surfaces (Figure 9) were first employed so that A and B serve as point contacts, as described in Section 4.1. For each test object, the -plane was defined such that G and B form a planar antipodal grasp in accordance with Section 5.1 (Figure 10a). All test objects were able to maintain x-rotational stability either through an edge contact (as in the puzzle piece shown in Figure 10a) or through a small curvature at G (the fabric chalk and guitar pick). A planar ungrasp was then arranged in the -plane (Figure 10b), and the planner was executed. An example path is shown in Figure 10c, based on the parameters (digit asymmetry) and , (friction coefficients at each contact). The planned ungrasp was carried out from , the initial configuration where the test object was pinched between the digits of the gripper. The object was subsequently placed on a flat tabletop at configuration , following the planned sequence of primitives: (along the -axis) followed by (along the -axis), as illustrated in Figure 10c.

Figure 10.

(a) Determination of the manipulation plane—the -plane. (b) Reduction to planar ungrasping. (c) Planned ungrasp path. (d) Two termination maneuvers: gripper rotation about T (the thumb tip) or aperture increase when is sufficiently small. Reprinted with permission from [3].

A placement attempt was considered successful if no loss of grip occurred prior to executing a termination maneuver (Figure 10d). This maneuver was carried out at a small value—the angle between the object and the target surface—to complete the ungrasping process while preventing collision between the thumb and the surface. The experiments (Figure 11a) achieved an overall success rate of 109 out of 120 trials, with mean positioning errors below 2.6 mm. No breakage of the brittle chalk was observed when the termination was performed using the “open gripper” maneuver (Figure 10d). The failed attempts were primarily due to premature grip loss, which stemmed from the gripper’s inability to maintain the intended contact modes. This, in turn, was mainly caused by inaccuracies in modeling the object geometry, particularly for objects with curved boundaries such as the fabric chalk and guitar pick. Full results are summarized in Table 1 (see the entries labeled under Section 6.2.1), which report the values of digit asymmetry (Figure 10b), initial configurations (Figure 10c), and the resulting outcomes. Note that same-length digits with were unable to reproduce the successful outcomes, as also reported in our prior study [1].

Figure 11.

Progression of precision placement with the test objects: (a) base scenario (curved fingertip used as shown in the first panel), (b) robustness through edge contact (flat fingertip used as shown in the first panel), (c) robustness through caging, and (d) puzzle tiling. In these cases, the axis of the object’s rolling on the tabletop and the axis of the thumb’s rolling about the object’s edge are non-parallel, necessitating three-dimensional motion control. Reprinted with permission from [3].

Table 1.

Results of precision placement experiments. Reprinted in part with permission from [3].

6.2.2. Robustness of Edge Contact

Building on the base scenario described above, the effectiveness of edge contact, as introduced in Section 4.4, was evaluated. An edge contact at A was employed using a digit with a flat rectangular surface (Figure 9), and placement was executed with the same test objects and experimental conditions as in the base scenario. See Figure 11b. Overall, edge contact demonstrated higher effectiveness than point contact. Detailed results are provided in Table 1, the entries labeled under Section 6.2.2.

6.2.3. Robustness by Caging

Our previous work [2] demonstrated that planar ungrasping can be executed robustly in the presence of errors and uncertainties. Here, it is examined whether such robustness extends to three-dimensional ungrasping. First, the placement of a 1.5 mm-thick guitar pick was successfully achieved using the motion setup originally designed for a thinner 0.96 mm pick (Table 1, Section 6.2.3). This result confirms the subset property of cages: once an object is caged, larger objects can also be effectively caged. Second, deliberate deviations (i.e., errors and uncertainties) were introduced into the motion paths planned by our approach (see the gray dashed line from in Figure 10c). Along such a path, the initial was set larger, placing the object outside at the start. In this configuration, force-closure does not hold initially—contacts may be lost or displaced, and interactions may not occur as intended. Nevertheless, as discussed in Section 3.1, the object can still be effectively caged—specifically through energy-bounded caging, which requires positive work input to remove the object, resulting in successful ungrasping. This robustness was confirmed experimentally, with a success rate of 34 out of 40 trials using an edge contact (Figure 11c). In contrast, point contact exhibited far lower reproducibility, achieving only 4 out of 40 successful trials. In these failed cases, the object escaped from the gripper via nonplanar motion outside the -plane.

6.2.4. Simple Puzzle Tiling

Building on the single-object placement tasks, tangram puzzle tiling was performed (Figure 11d). This task involved packing seven polygonal pieces—comprising right triangles, a square, and a parallelogram—of varying sizes and shapes into a tight square frame. Each puzzling attempt consisted of a sequence of seven placement trials. A puzzling attempt was deemed successful when all seven pieces fit flat within the square frame. The experiments yielded a success rate of 9 out of 10 puzzling trials. Equivalently, at least out of single-piece placement attempts were sufficiently precise and accurate to allow the subsequent placements to proceed smoothly.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

This paper presented a framework for achieving robust three-dimensional stability in dexterous ungrasping, along with a corresponding planning strategy for spatial dexterous manipulation. The proposed method is applicable to a wide range of low-profile objects—a particularly challenging class due to their limited graspable features and tendency to slip or tilt during release—and can be implemented using a standard motion-controlled arm and an ordinary two-fingered gripper, making it both practical and versatile for real-world applications. While the fingertip lengths may further need to be customized, this requirement can be readily addressed through, for example, 3D printing, as in our experiments. Experimental evaluations—covering single- and multi-object placement tasks—demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed technique and reaffirm the benefits of digit asymmetry and caging observed in our earlier study.

Although the approach requires careful motion planning and control that account for the geometry of both the object and the manipulator, it provides a robust solution to precision placement tasks involving low-profile objects. The results also suggest that enhanced situational awareness—through sensor fusion or active perception—could further improve performance and robustness, representing a promising direction for future research. Another potential avenue is integrating the proposed ungrasping technique with picking strategies to enable autonomous dexterous pick-and-place operations.

Funding

This work was supported by the BK21FOUR program, Creative HR Education and Research Programs for ICT Convergence in the 4th Industrial Revolution and by the Two-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kim, C.H.; Mak, K.H.; Seo, J. Planning for Dexterous Ungrasping: Secure Ungrasping Through Dexterous Manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 2234–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.H.; Kim, C.H.; Seo, J. Robust Ungrasping of High Aspect Ratio Objects Through Dexterous Manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Kim, J.; Oh, S.; Lim, W.; Lee, J.; Yi, S.J.; Seo, J. Dexterous Ungrasping Manipulation in Three Dimensions. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 May 2025; pp. 14030–14036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, H.; Ge, D.; Li, X.; Ding, H. A Novel Robotic Multiple Peg-in-Hole Assembly Pipeline: Modeling, Strategy, and Control. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechat. 2024, 29, 2602–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Qian, C.; Zhou, F.; Li, T.; Huang, Z. Learning Robust Skills for Tightly Coordinated Arms in Contact-Rich Tasks. IEEE Robot. Automat. Lett. 2024, 9, 2973–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shome, R.; Tang, W.N.; Song, C.; Mitash, C.; Kourtev, H.; Yu, J. Towards Robust Product Packing with a Minimalistic End-Effector. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 9007–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Song, S.; Lee, J.; Rodriguez, A.; Funkhouser, T. TossingBot: Learning to Throw Arbitrary Objects With Residual Physics. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2020, 36, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournassoud, P.; Lozano-Pérez, T.; Mazer, E. Regrasping. In Proceedings of the 1987 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Raleigh, NC, USA, 31 March 31–3 April 1987; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1987; Volume 4, pp. 1924–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Trinkle, J.C.; Paul, R.P. Planning for dexterous manipulation with sliding contacts. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1990, 9, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Trinkle, J.C. Dextrous manipulation by rolling and finger gaiting. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Leuven, Belgium, 16–20 May 1998; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 730–735. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, D. In-hand dexterous manipulation of piecewise-smooth 3-d objects. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1999, 18, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchi, A.; Marigo, A. Dexterous grippers: Putting nonholonomy to work for fine manipulation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2002, 21, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafle, N.C.; Rodriguez, A.; Paolini, R.; Tang, B.; Srinivasa, S.S.; Erdmann, M.; Mason, M.T.; Lundberg, I.; Staab, H.; Fuhlbrigge, T. Extrinsic dexterity: In-hand manipulation with external forces. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1578–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan-Dafle, N.; Rodriguez, A. Prehensile pushing: In-hand manipulation with push-primitives. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 6215–6222. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Lou, X.; Liu, Y.; Choi, C. Attribute-Based Robotic Grasping With Data-Efficient Adaptation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 1566–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Chang, F.; Huan, H.; Cheng, K. Multi-Stage Reinforcement Learning for Non-Prehensile Manipulation. IEEE Robot. Automat. Lett. 2024, 9, 6712–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhner, L.U.; Ma, R.R.; Dollar, A.M. Open-loop precision grasping with underactuated hands inspired by a human manipulation strategy. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2013, 10, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, T.; Kanada, K.; Arai, F.; Matsuura, H.; Fukuda, T. Strategy of picking up thin plate by robot hand using deformation of soft fingertip. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Barcelona, Spain, 18–22 April 2005; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 2326–2331. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, V.; Gosselin, C. Picking, grasping, or scooping small objects lying on flat surfaces: A design approach. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2018, 37, 1484–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2011, 30, 846–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Park, F.C. Modern Robotics: Mechanics, Planning, and Control; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler, J.; Pokorny, F.T.; McCarthy, Z.; van der Stappen, A.F.; Goldberg, K. Energy-Bounded Caging: Formal Definition and 2-D Energy Lower Bound Algorithm Based on Weighted Alpha Shapes. IEEE Robot. Automat. Lett. 2016, 1, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.D. Constructing stable grasps. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1989, 8, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Liu, H.; Cai, H.G. On computing three-finger force-closure grasps of 2-D and 3-D objects. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 2003, 19, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lim, W.; Kim, J.; Kang, T.; Yi, S.J.; Seo, J. Dynamic Self-Righting of Planar-Based Objects on Dual Supports and its Implications for Robotic Object Placement. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 10194–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Li, Z.; Sastry, S. A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Woodruff, J.Z.; Umbanhowar, P.B.; Lynch, K.M. Dynamic In-Hand Sliding Manipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafle, N.; Holladay, R.; Rodriguez, A. Planar in-hand manipulation via motion cones. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2020, 39, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).