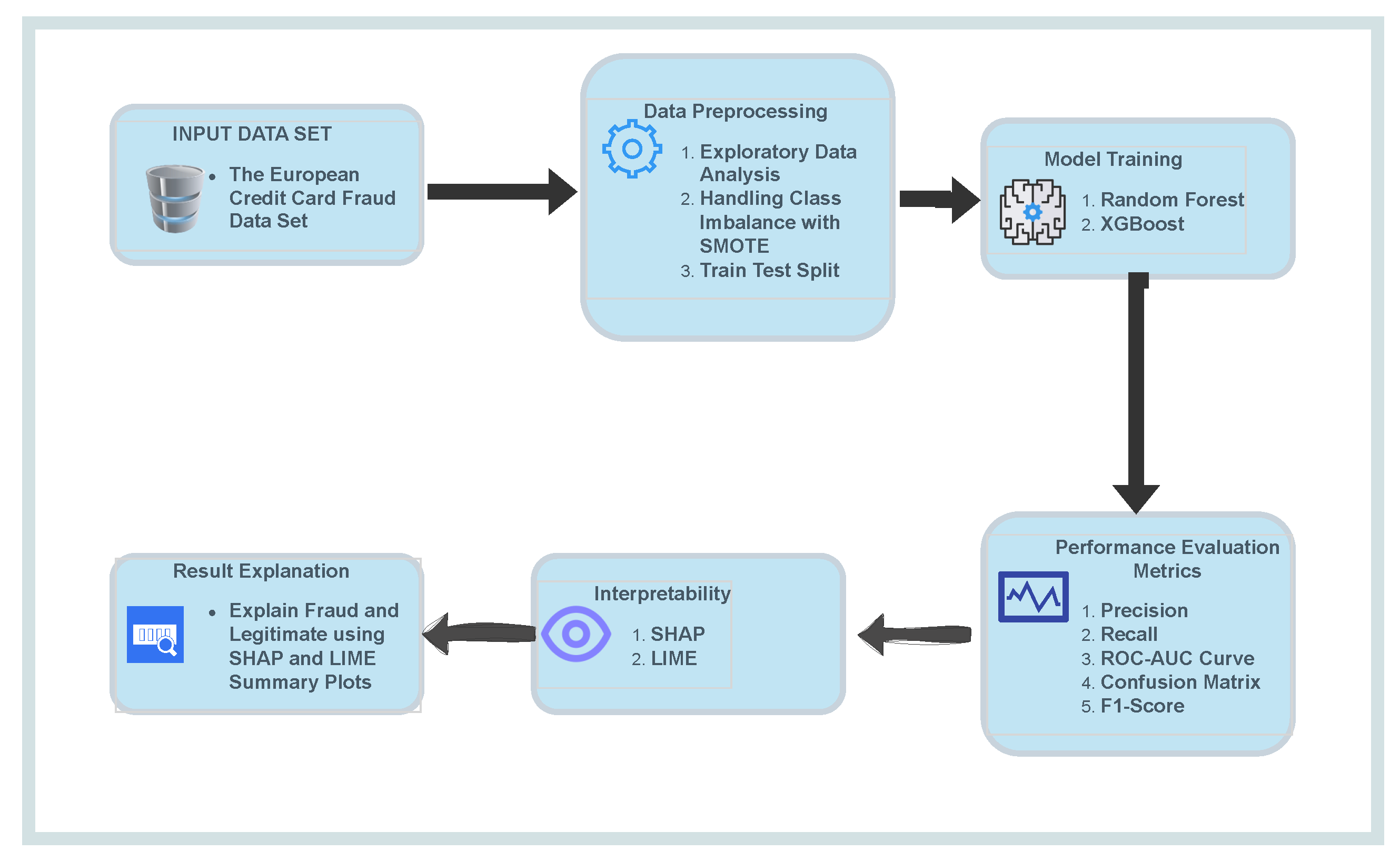

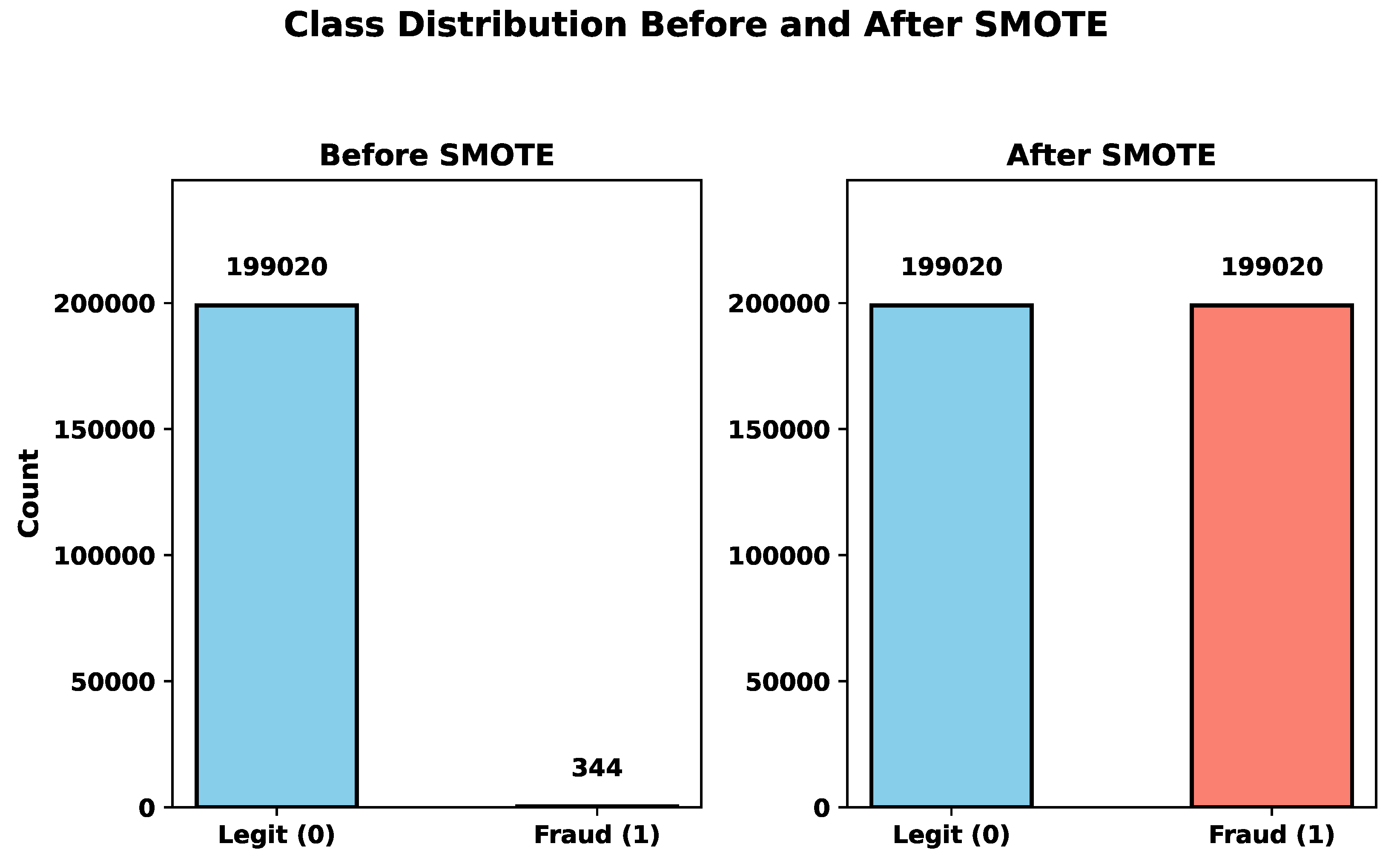

Machine learning models have shown strong potential in handling imbalanced fraud detection datasets, where class distributions are highly skewed. Imbalanced datasets pose a significant challenge in credit card fraud detection, as the small proportion of fraudulent transactions often leads to biased models with poor generalization. Researchers in [

8] conducted a comprehensive survey of ML methods and highlighted both the limitations caused by data imbalance and the importance of incorporating explainable systems to improve reliability. They further suggested that hybrid approaches could enhance performance. However, despite these advances, a key challenge remains in understanding model decisions, particularly in regulatory-compliant industries such as banking, where explainability is essential for accountability and trust. The study [

9] compared various ML algorithms and data balancing techniques, including SMOTE, ADASYN, and NCR, for handling highly imbalanced fraud detection datasets. Their results showed that XGBoost with Random Oversampling achieved the highest F1-score (92.43%), followed closely by Random Forest. While these findings confirm the strong predictive power of ensemble models, they also underscore the need for explainability, as high performance alone does not satisfy regulatory and operational requirements in fraud detection. Unsupervised methods have also been explored to overcome challenges such as data imbalance, privacy concerns, and limited availability of labeled fraud data. For example, Kennedy et al. [

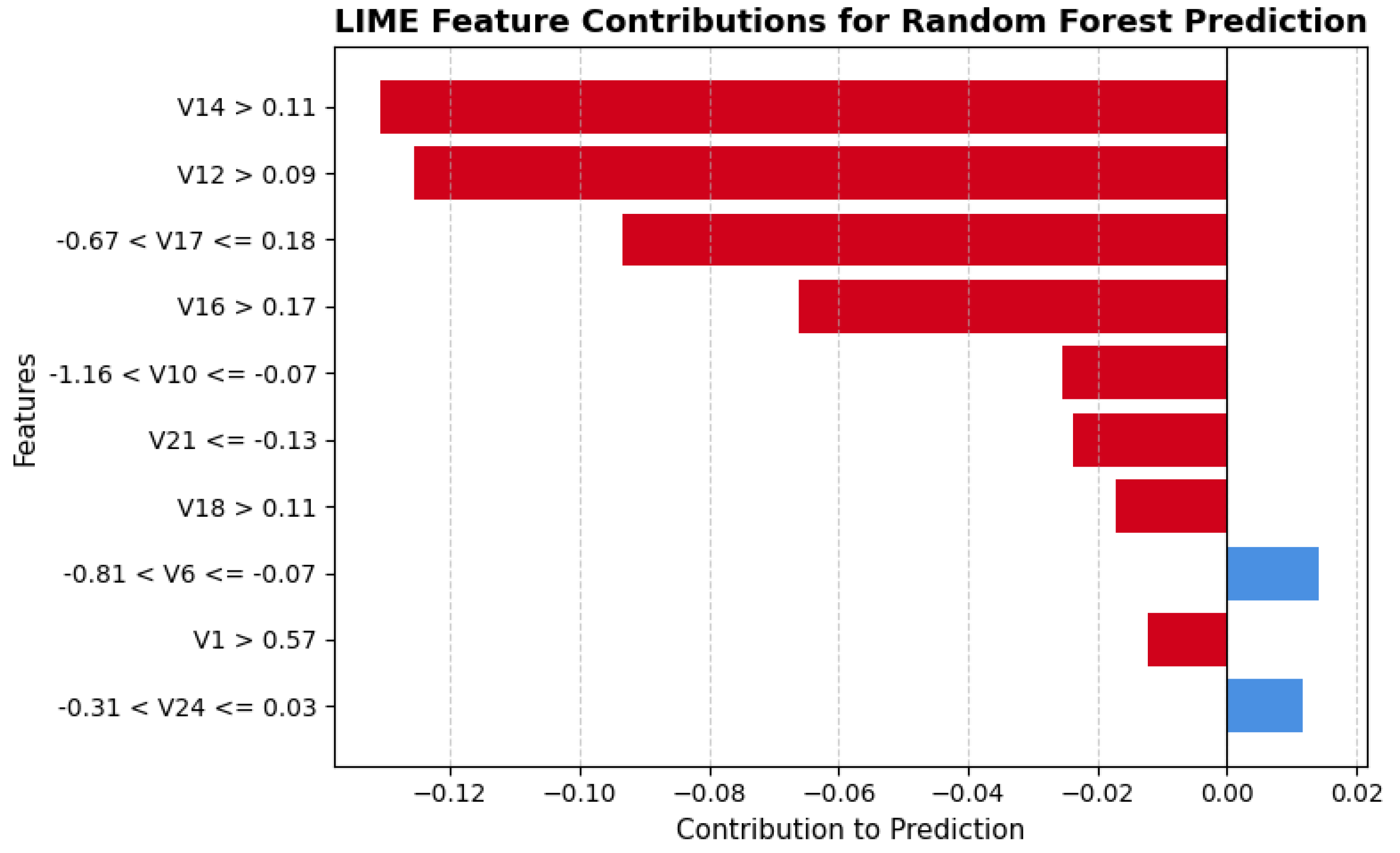

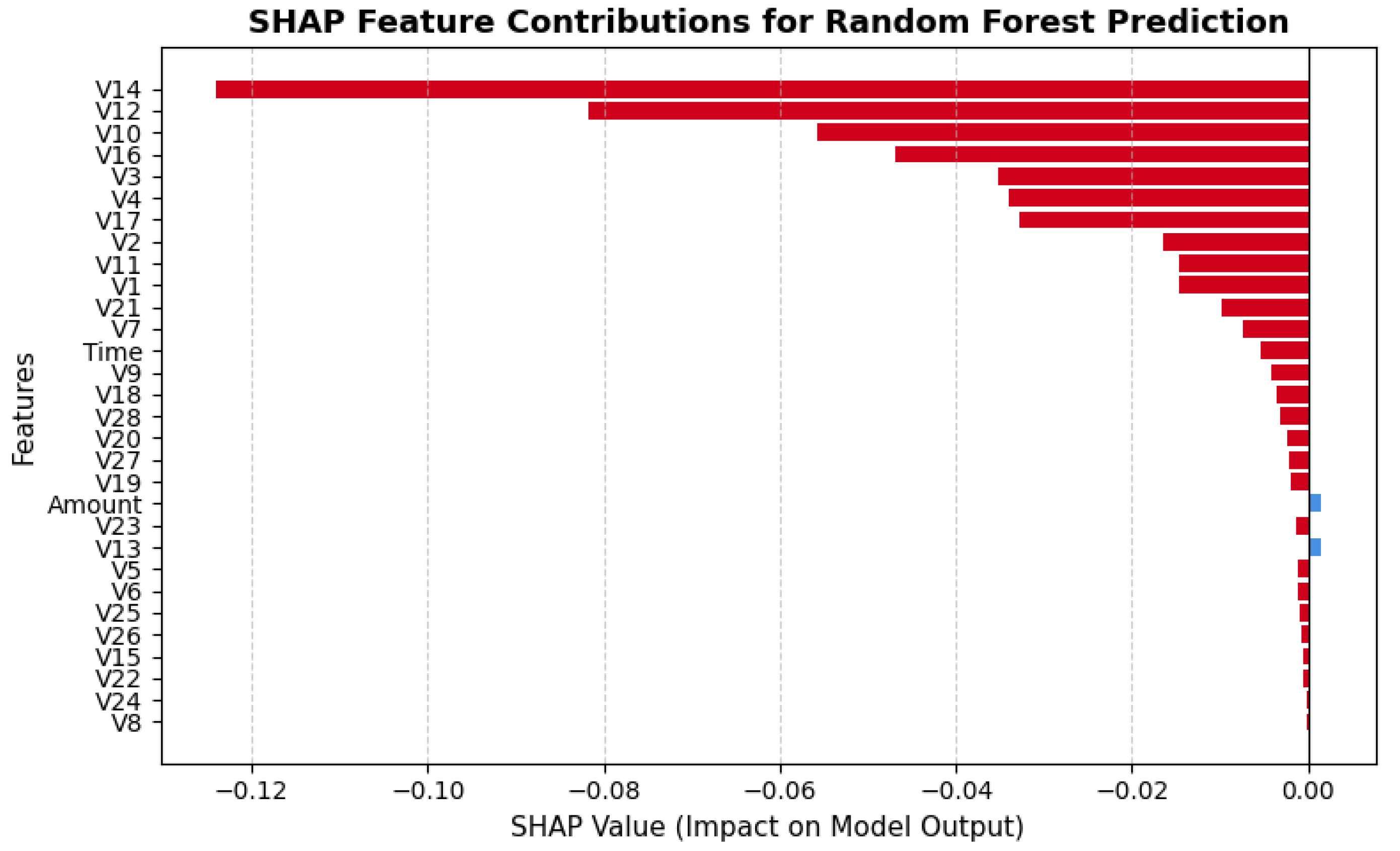

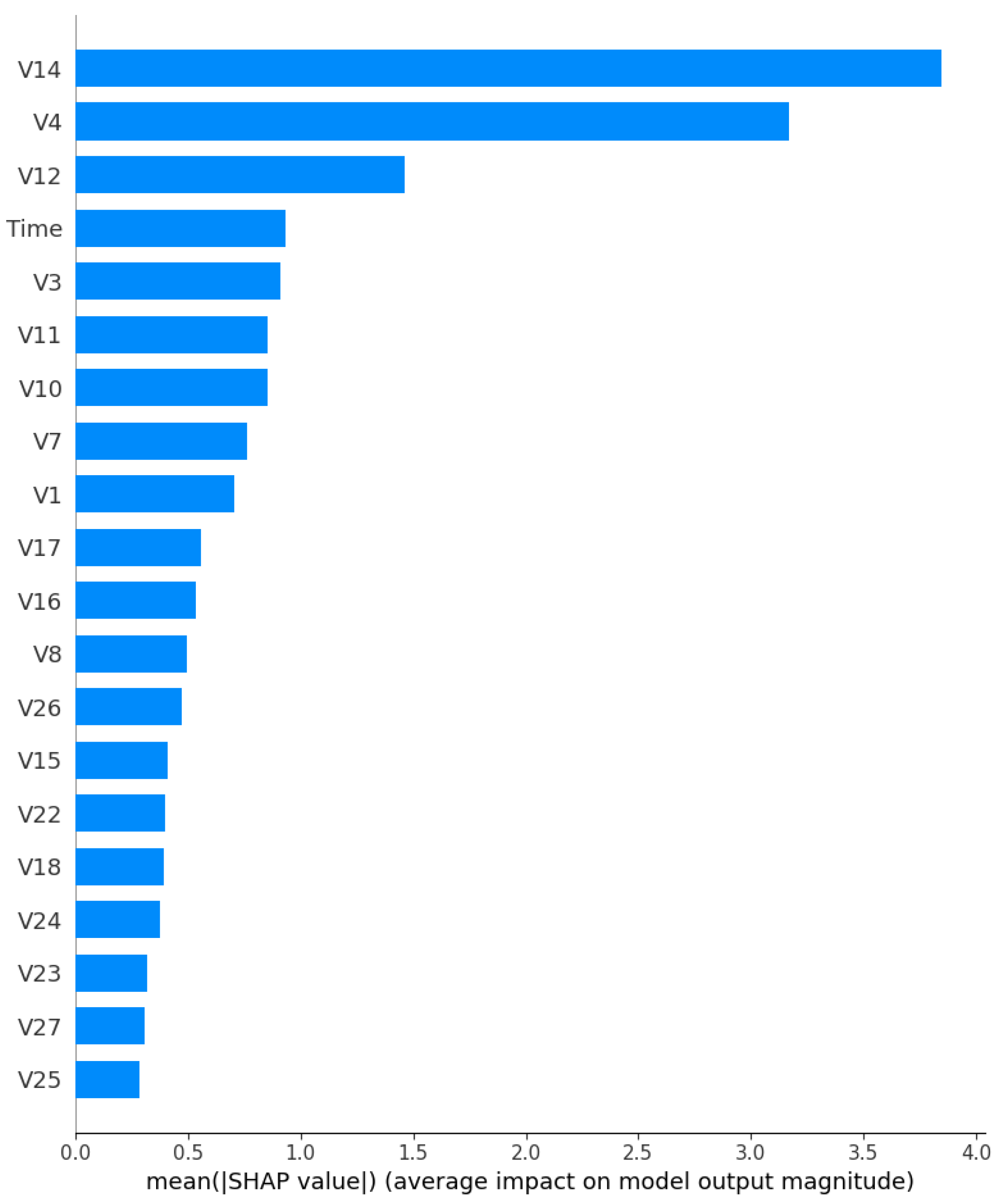

10] proposed a framework that combines SHAP-based feature selection with an autoencoder for label generation. Their approach demonstrated that unsupervised learning can be effective for numerical transaction data. However, the framework relied only on SHAP for global feature ranking, which limited interpretability at the individual decision level. This highlights the need for approaches that incorporate both global and local explainability, a gap this study addresses by systematically applying SHAP and LIME to ensemble models. Unsupervised anomaly detection has also been combined with explainability techniques. Hancock et al. [

11] integrated SHAP with Isolation Forest to identify the most informative features without relying on labeled data. Their results showed that models trained on the top 15 SHAP-ranked features achieved performance comparable to, and in some cases better than, those trained on the full feature set, as measured by AUPRC and AUC. While effective for feature selection, this approach primarily emphasized global importance and did not provide deeper insights into instance-level interpretability, which is essential for decision justification in financial applications.

2.2.1. Deep Learning and Hybrid Approaches

Deep learning models such as ResNeXt and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) for fraud detection were explored by [

12] and compared their results with traditional machine learning models. Despite their success in performance metrics, these deep learning models lacked interpretability, which makes it difficult to understand the model. Similarly, in [

13], they integrate Graph Neural Networks (GNN) and Autoencoders for fraud detection, and their results declared high performances, but the inherent complexity of these models raised concerns about their transparency and real-world deployment in banking systems. Another significant contribution to credit card fraud detection is presented by authors who developed a hybrid deep learning framework integrating Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

14]. In this approach, the GAN component generates realistic synthetic fraudulent transactions to mitigate class imbalance, while the discriminator, implemented using architectures such as Simple RNN, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), learns to differentiate between real and generated transactions. The model achieved outstanding performance, with the GAN-GRU configuration attaining a sensitivity of 0.992 and a specificity of 1.000 on the European credit card dataset. While this method effectively enhances detection accuracy and data diversity, it primarily focuses on deep neural modeling without offering interpretability. In contrast, the present work leverages ensemble learning models (Random Forest and XGBoost) alongside explainable AI (SHAP and LIME) to ensure both predictive strength and model transparency, facilitating better understanding and trust in financial decision-making systems. Yang et al. [

15] proposed an advanced framework that integrates a Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture with a Deep Neural Network-based Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (DNN-SMOTE) to address the severe class imbalance in credit card fraud detection. Their approach combines multiple specialized expert networks trained to detect specific fraud patterns, while the DNN-SMOTE component generates synthetic samples to improve data balance and overall classification performance. Although their model achieved outstanding accuracy (99.93%) and robustness, it primarily focuses on deep neural network optimization without providing interpretability into decision-making processes. In contrast, the present study employs ensemble learning methods, Random Forest and XGBoost, augmented with explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHAP and LIME. This combination not only enhances detection performance on imbalanced datasets but also provides transparent, interpretable explanations for each model prediction, making the framework more suitable for real-world financial applications where interpretability and regulatory compliance are critical.

2.2.2. Ensemble Learning Techniques for Fraud Detection

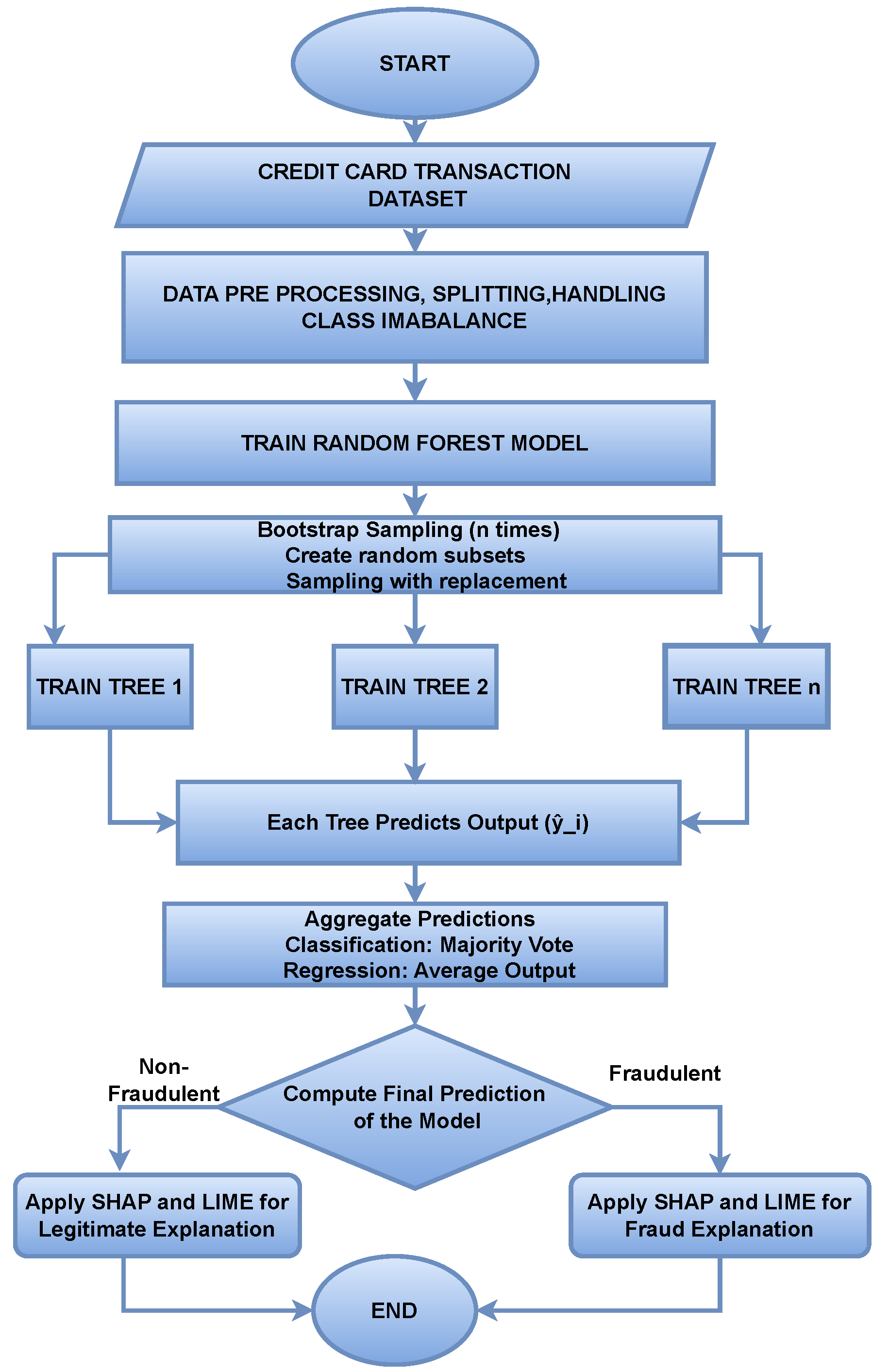

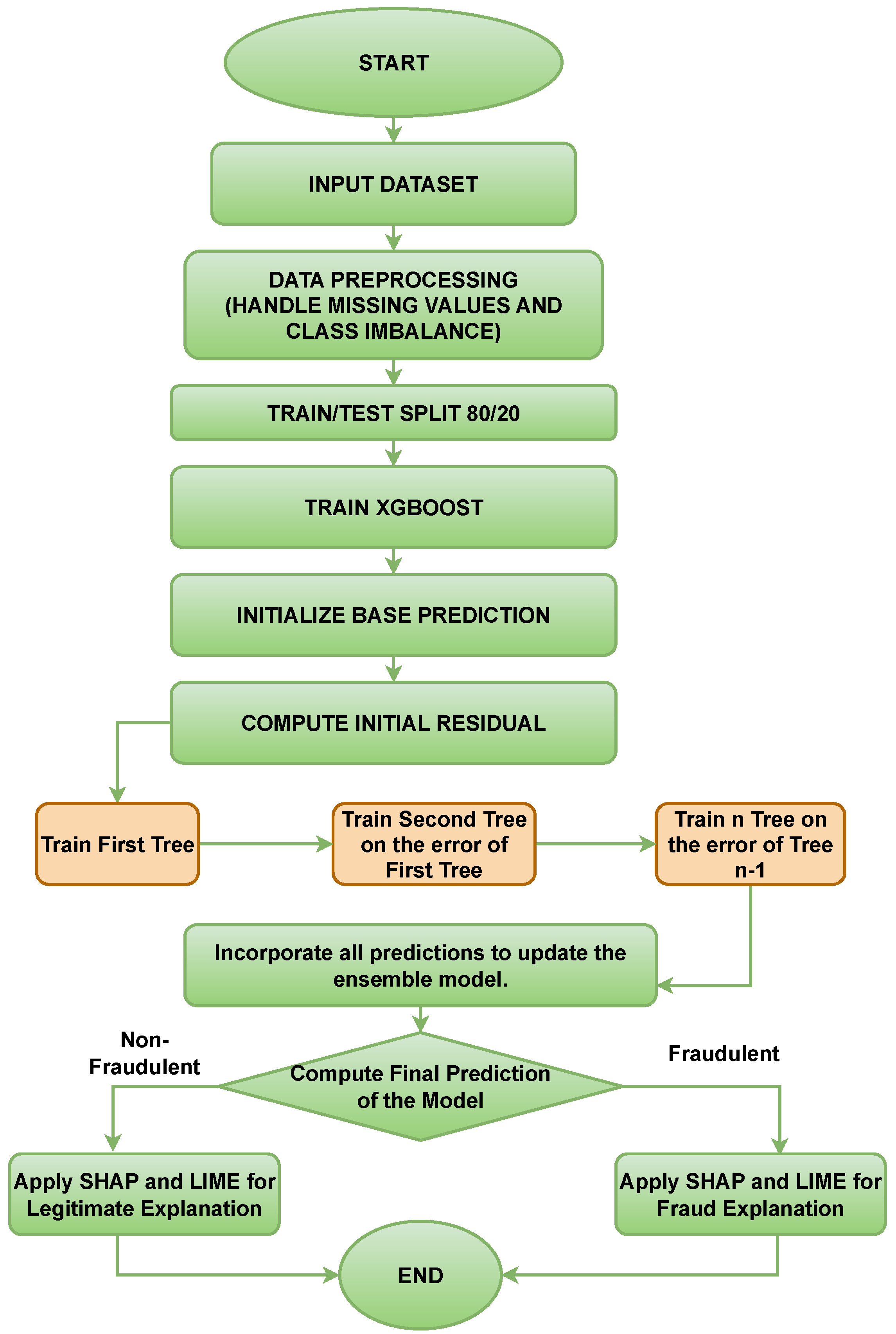

Ensemble learning techniques are well-suited for numerical features because they provide high accuracy and improve classification. These methods have been widely used in fraud detection systems. In [

16], the authors explored RF and XGBoost against deep learning models. Their study revealed that while deep networks can capture complex fraud patterns, RF and XGBoost remain preferable for real-time fraud detection due to their computational efficiency and interpretability. The study [

17] compared RF and XGBoost under varying class imbalance conditions and concluded that hyperparameter-tuned XGBoost consistently outperformed Random Forest in F1-score and precision. Despite these advantages, their study did not investigate the interpretability of these ensemble models, which leaves a critical gap in understanding how these models make decisions. The study [

18] demonstrated that ensemble techniques perform better than other ML models as they are simple, require less data, and work well with explainability tools. Jiang et al. [

19] proposed an Unsupervised Attentional Anomaly Detection Network (UAAD-FDNet) for credit card fraud detection, where fraudulent transactions were treated as anomalies instead of being handled through traditional supervised classification. Their model integrates an autoencoder with feature attention and a generative adversarial network (GAN) to enhance representation learning and mitigate the effects of class imbalance. While this unsupervised approach effectively detects anomalies without relying on labeled data, it lacks interpretability and fails to explain the reasoning behind its predictions. In contrast, the present study employs supervised ensemble learning models, Random Forest and XGBoost, combined with explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHAP and LIME, thereby achieving both strong predictive performance and transparent model interpretability in financial fraud detection. Mosa et al. [

20] proposed the CCFD framework, which integrates meta-heuristic optimization (MHO) techniques with traditional machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest and SVM to enhance feature selection and classification efficiency in credit card fraud detection. Their study focused on mitigating the data imbalance problem and optimizing computational performance through intelligent feature subset selection. In contrast, the current research emphasizes interpretability and ensemble learning by combining Random Forest and XGBoost models with explainable AI (XAI) techniques, including SHAP and LIME, to achieve both high predictive accuracy and model transparency, providing more interpretable and trustworthy fraud detection outcomes.

2.2.3. Explainable AI in Fraud Detection

Regulatory bodies such as finance and banking are often required to demonstrate the results to their stakeholders and end-users, explaining why a certain transaction was labeled as fraudulent by the model. Machine learning models perform very well in detecting complex patterns of fraud, but they often lack explainability and interpretability, which are crucial for real-life systems. Systematic reviews have also emphasized the strengths and limitations of existing fraud detection approaches. Ali et al. [

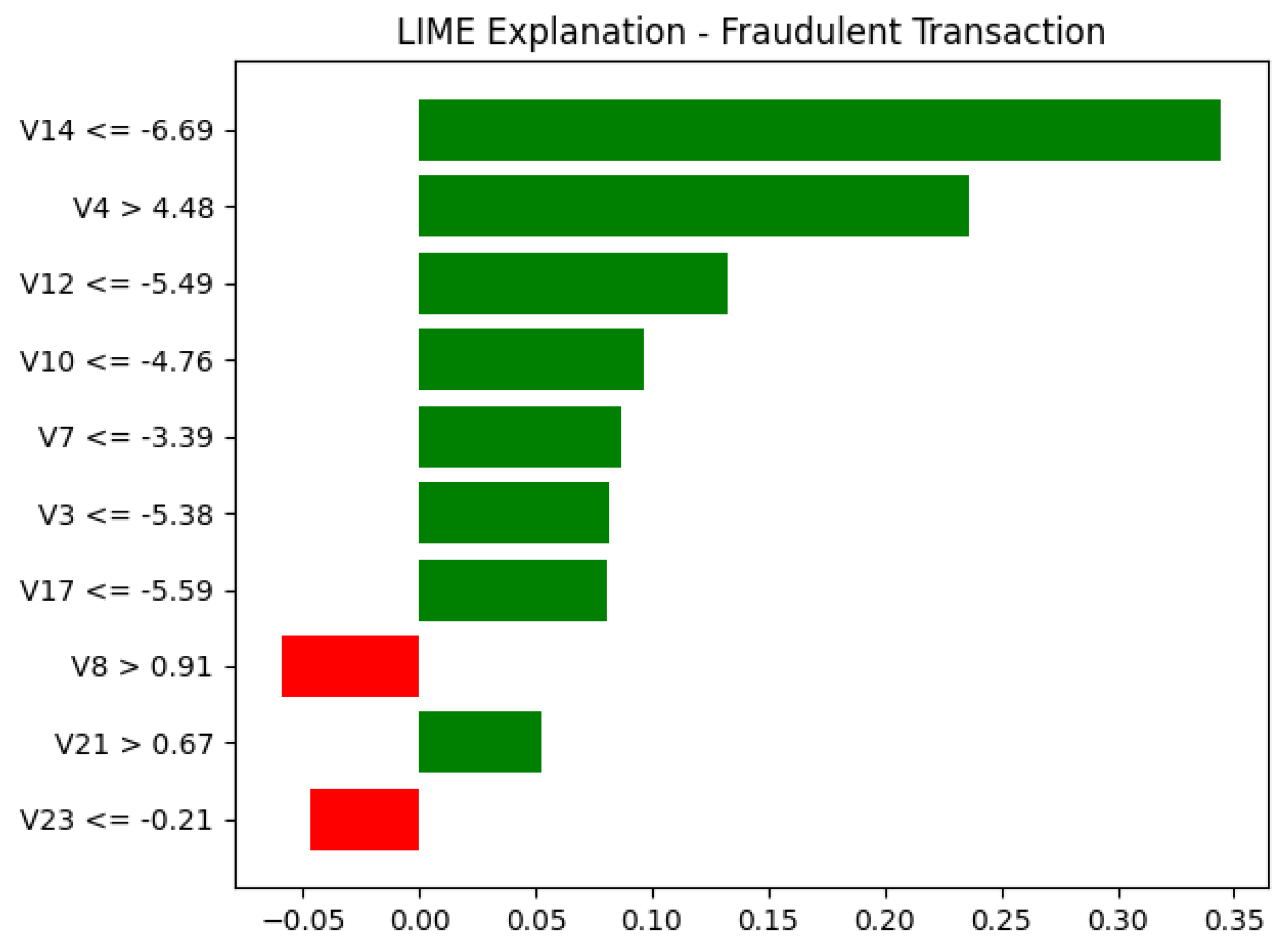

4] found that credit card fraud is the most extensively studied area, with ensemble methods such as Random Forest frequently applied due to their robustness in handling imbalanced data. However, the review also underscored the persistent lack of interpretability in these models, calling for the integration of XAI techniques to enhance transparency. This aligns directly with the focus of the present study, which applies SHAP and LIME to bridge this gap in ensemble-based fraud detection. Recent work has begun to incorporate explainability into fraud detection frameworks. For instance, Nobel et al. [

21] applied SHAP and LIME across multiple machine learning models and demonstrated that these tools enhance transparency, improve feature attribution, and provide actionable insights for financial analysts. However, the study excluded Random Forest, a widely used ensemble method in fraud detection, and did not systematically compare interpretability between models. This gap motivates our focus on evaluating both Random Forest and XGBoost with SHAP and LIME to provide a more comprehensive analysis of explainability in fraud detection. Aljunaid et al. [

22] applied XGBoost with SHAP and LIME to improve interpretability in financial fraud detection, demonstrating that these tools can help explain model predictions and support decision-making. However, their analysis was limited to a single ensemble method (XGBoost) and did not compare interpretability across different models. Building on this, our study evaluates both Random Forest and XGBoost to provide a broader perspective on how ensemble methods balance predictive performance with explainability. Another study [

23] explored the use of SHAP for anomaly detection in financial systems, showing that SHAP can enhance model interpretability by identifying influential features. While this work demonstrated the value of explainability in unsupervised settings, it focused only on SHAP and did not incorporate complementary tools such as LIME, which provide local, instance-level explanations. Our study extends this direction by systematically applying both SHAP and LIME to ensemble models, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of interpretability in fraud detection. The study [

24] demonstrated the use of SHAP and LIME for enhancing interpretability in machine learning models, applying them in the context of urban remote sensing for land class mapping. Their findings showed that while XGBoost achieved higher accuracy, Random Forest provided clearer explanations, making it more suitable for applications where regulatory compliance and transparency are critical. Although conducted in a different domain, this work underscores the broader importance of balancing accuracy with interpretability, a trade-off that this study investigates specifically in the context of financial fraud detection.

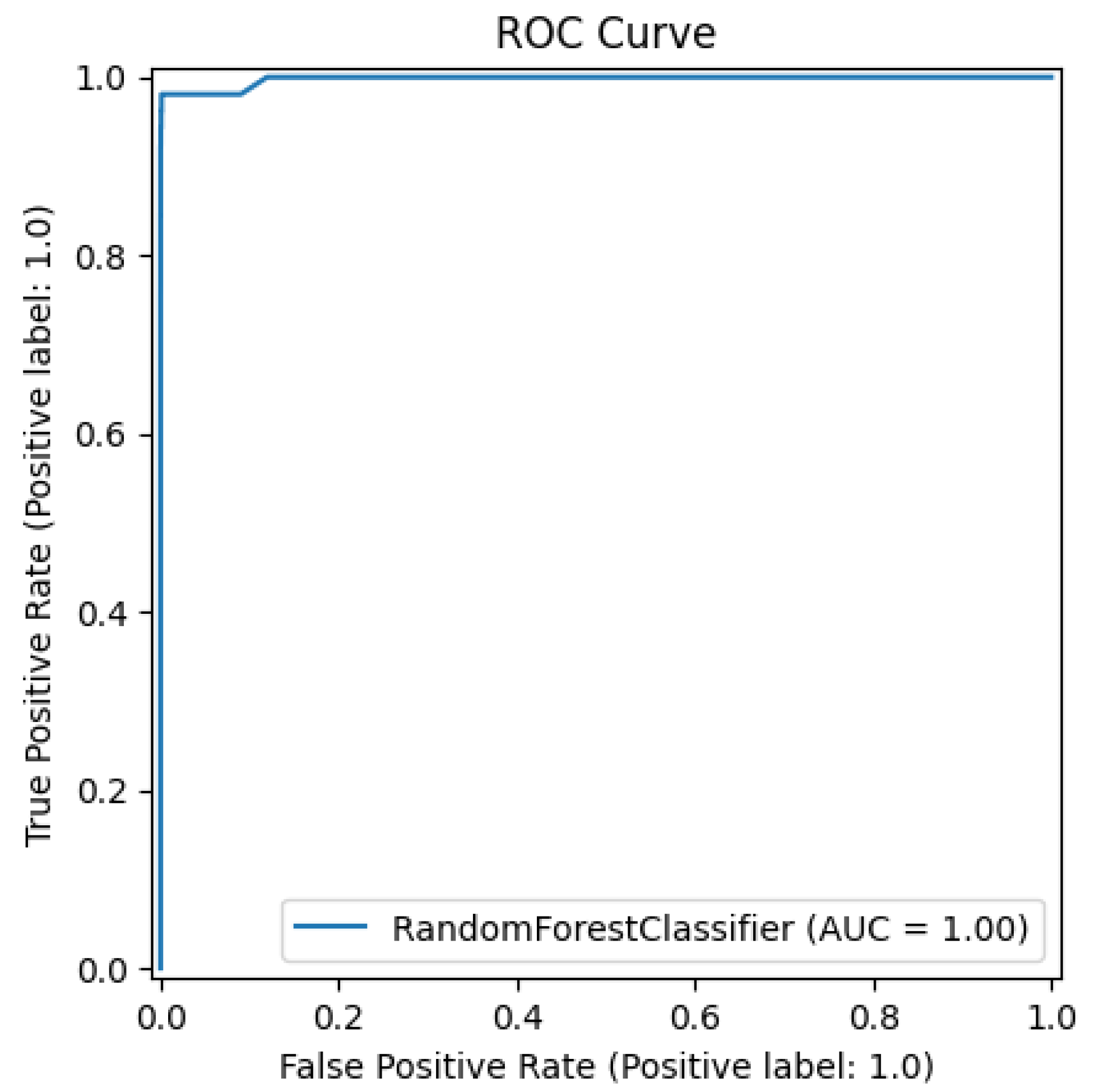

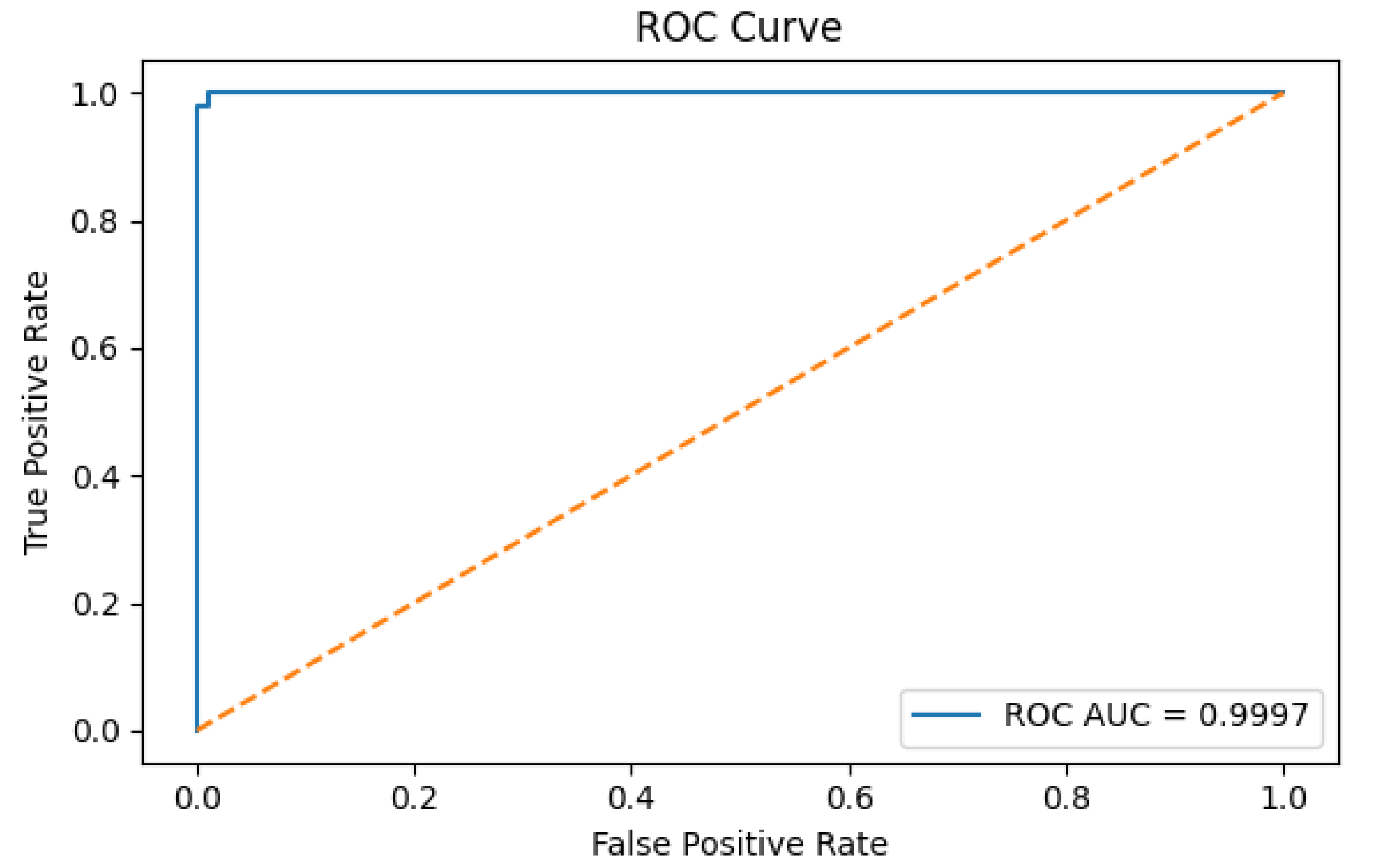

Similarly, Caelen, O. [

25] reviewed machine learning approaches to fraud detection, categorizing them into supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid models. The study found that supervised methods such as Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM, and Logistic Regression perform well when sufficient labeled data are available but struggle with severe class imbalance. To mitigate this, the authors emphasized relying on precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC rather than overall accuracy. In contrast, unsupervised models like K-Means and DBSCAN are better suited for unlabeled datasets but are limited to detecting unusual patterns. These findings reinforce the importance of choosing models and evaluation metrics carefully, particularly in imbalanced fraud detection settings, a consideration central to this study.

A separate investigation [

26] compares the performance of several classifiers, including Random Forest, Decision Tree, Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors, and SVM, using a real-world dataset characterized by a significant class imbalance. Random Forest exhibits effective results, achieving precision and recall rates of 0.98 and 0.93, respectively. The study noted potential drawbacks such as limited model interpretability and challenges in adapting to new types of fraud.

XGBoost has been shown to outperform traditional models such as logistic regression in fraud detection. For example, Dichev et al. [

27] demonstrated that XGBoost reduces both false positives and false negatives, thereby improving accuracy, operational efficiency, and regulatory compliance. However, the study also emphasized the dependence on feature engineering and noted that interpretability remains a challenge.

Building on this, Tursunalieva et al. [

28] highlighted the role of XAI tools in enhancing transparency, trust, and accountability in fraud detection systems. At the same time, the authors cautioned that balancing predictive accuracy with interpretability and ethical considerations remains difficult, calling for standardized, user-centric XAI frameworks. These insights underscore the need for comparative studies, such as the present work, that evaluate both performance and interpretability in ensemble models.

Machine learning techniques, particularly ensemble models such as Random Forest and XGBoost, have demonstrated strong potential in fraud detection due to their ability to analyze large-scale numerical data and uncover hidden patterns. While these models achieve high accuracy, their lack of interpretability remains a major limitation. For example, Btoush et al. [

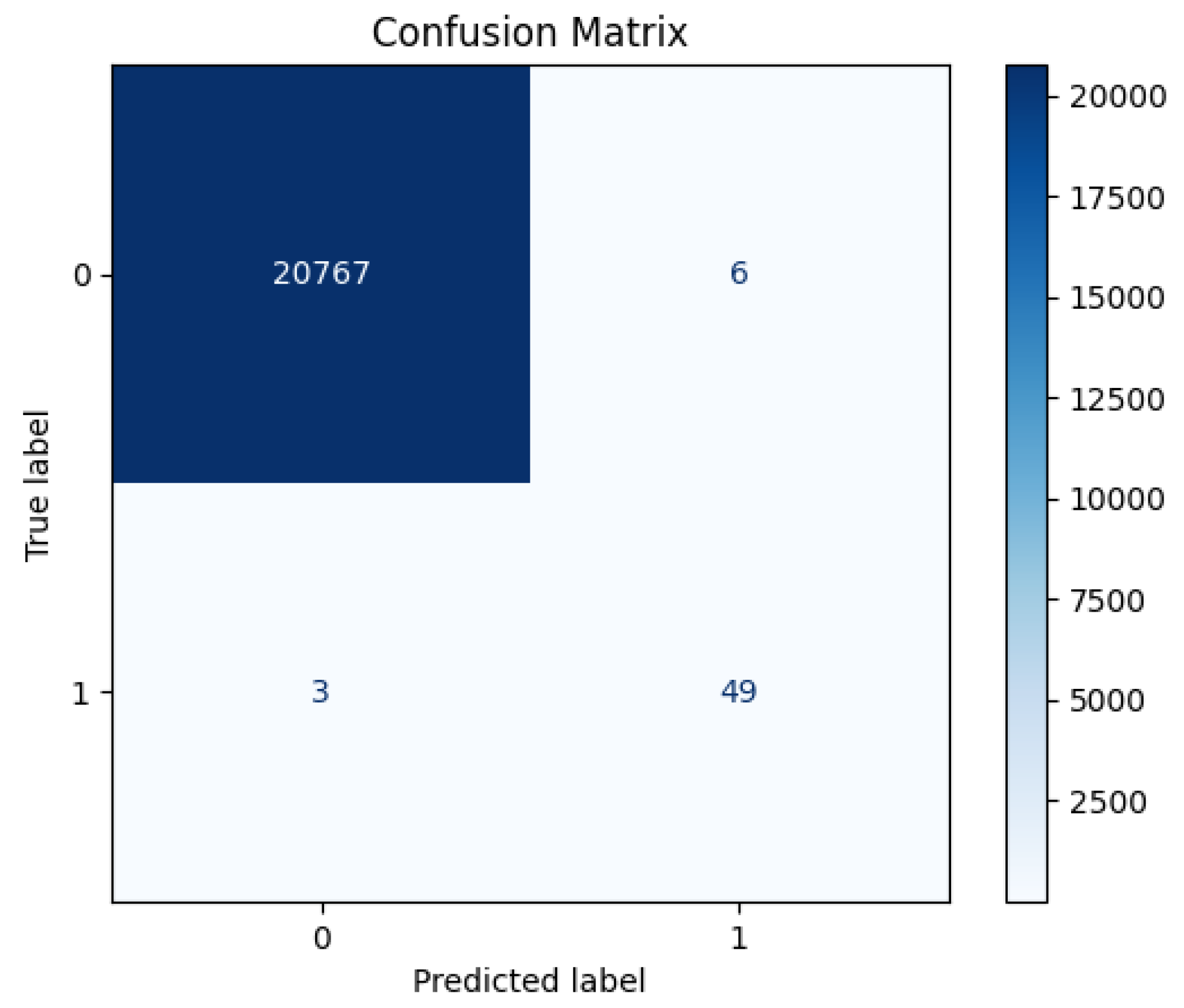

29] applied Random Forest and XGBoost to credit card fraud detection, reporting F1-scores of 85.71% (RF: precision 97.40%, recall 76.53%) and 85.3% (XGBoost: precision 95.00%, recall 77.55%). Although a hybrid model outperformed both, the study did not incorporate interpretability techniques such as SHAP or LIME. Similarly, Khalid et al. [

30] proposed an ensemble framework combining SVM, KNN, Random Forest, Bagging, and Boosting to address challenges of data imbalance, computational efficiency, and real-time detection, yet interpretability was not considered.

In summary, prior studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Random Forest and XGBoost for fraud detection but have largely overlooked interpretability, with SHAP and LIME rarely applied systematically. This study addresses that gap by comparing both models on a real-world dataset and integrating SHAP and LIME to evaluate interpretability alongside predictive performance. In doing so, it contributes practical guidance for building transparent and reliable fraud detection systems.